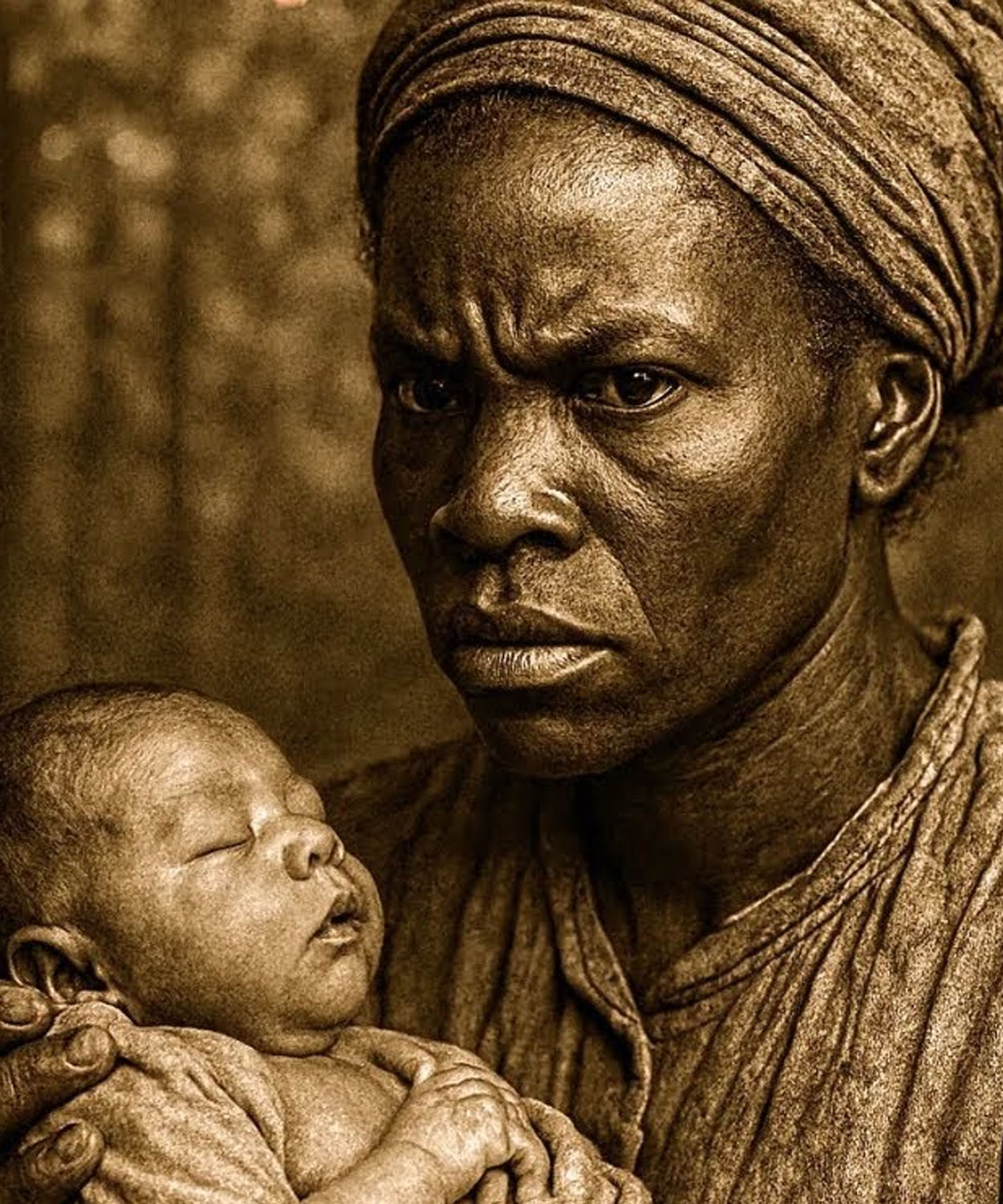

In the summer of 1,842, on the outskirts of Pine Hollow Plantation, a single cry pierced the night, short, sharp, then abruptly smothered.

The cabin where the sound came from still smelled of birth, boiled rags, sweat, iron, and blood.

But by the time Dawn crawled over the treeine, the child who had filled that cabin with his first breath was gone.

No one spoke of him.

No one admitted what they had seen, but every slave on the plantation knew the truth.

The master’s wife had ordered the infant taken, and the overseer had carried out the deed with the same cold obedience he had for every cruelty the Latimore family demanded.

The mother, Eta, young yet already worn by years of field labor and grief, remained lying on the pallet long after the others had been dragged off to work.

She stared at the empty space where her child should have been swaddled.

She had named him in her heart, never allowed, never on paper, because she knew names made things vulnerable.

Names gave the world something to take, but they took him anyway.

Rumors crawled through the quarters like insects.

The mistress had heard the baby’s skin was too light and feared scandal.

The master had refused to acknowledge him.

The overseer had carried the child toward the river.

Some said he returned empty-handed.

Others said they heard a splash.

No one knew which version was the truth.

Only one person intended to find out.

Only one intended to make them pay.

Eta had always been quiet.

She was a woman who kept her head down, who worked without complaint, who spoke only when necessary.

But grief made her into something else, something the plantation had never seen before.

In the days after the birth, she moved like a ghost, drifting through her tasks with an eerie calmness.

No tears, no outbursts, no pleading.

She simply watched, listened, counted.

There were 13 white people who lived on Pine Hollow Plantation.

Eda memorized them all, and every night beneath her pallet, where the dirt was softest, she carved another tally into the earth.

She would not rest until all the tallies matched the number in her mind.

The night they took her child, Pine Hollow lost the fragile balance that held it together.

What grew in its place was a storm, slow at first, then roaring with a fury that would destroy everything built on stolen breath.

This is the story of how one mother’s grief became fire.

How her silence became strategy.

And how Pine Hollow Plantation, one of the largest, richest, and most feared properties in eastern Mississippi, fell because a woman, who had nothing left to lose, chose to lose them all instead.

The pain of childbirth had barely faded from Eta’s body when she woke to the sensation of a hand covering her mouth.

Her eyes snapped open, still heavy with exhaustion.

In the moonlight filtering through the cracks of the cabin, she saw the silhouette of overseer Brandt, tall and broad-shouldered, smelling of tobacco and sweat.

“Stay quiet,” he murmured, though his tone promised pain if she didn’t.

Eda thrashed weakly, the kind of struggle that came not from strength, but from desperation.

Her body, raw and trembling, could not fight.

Her legs were numb.

Her arms felt like wet rope.

Hours earlier, she had pushed life into the world.

Now she could hardly lift her head.

Brandt’s other hand reached down.

Not toward her, toward the tiny bundle beside her.

No, no, please, please.

Her voice was nothing but breath.

He lifted the infant with rough hands, the baby letting out a thin, confused cry.

It was a sound that sliced straight through Eda’s ribs.

She reached for him, her fingers brushing the edge of the blanket.

But Brandt was already stepping back.

“The mistress says this one ain’t staying,” he said as though he were talking about a broken tool.

Eta clawed at the floor, dragging herself after him, but her legs refused to obey.

Pain radiated from her hips upward into her spine, the strain of childbirth still tearing through her muscles.

Brandt opened the cabin door with his shoulder, and a blast of cool night air washed over her.

Please, he ain’t done nothing.

Even she knew begging wouldn’t matter.

Brandt stepped outside.

The door closed.

The latch clicked.

The sound of her baby’s cries faded into the night until she could no longer tell if they were real or just her mind repeating them.

Hours passed or minutes.

Time lost meaning.

Eda dragged herself forward inch by inch until she reached the door.

She pressed her ear against it, listening for movement, voices, footsteps, anything.

But there was nothing except cicas and her own ragged breathing.

When morning came, the door opened not to Brandt, but to Emma, an older slave woman who had midwifed half the plantation for 30 years.

Her gaze moved from Eda’s pale face to the empty space beside her pallet, and her mouth tightened.

Child.

I am so sorry, Emma whispered.

Where he gone? Eda’s voice cracked like dry wood.

Emma shook her head.

Ain’t for us to ask.

But Eta saw The thing Emma tried to hide, a flicker of fear, and beneath it, pity.

Word traveled fast through the quarters.

By noon, everyone knew the baby was gone.

By nightfall, whispers spread of the mistress’s rage at the child’s complexion, of a quiet argument between her and the master, of Brandt leaving for the river and returning with wet boots.

Eta listened to every whisper.

She spoke to no one.

On the third night, she stood for the first time.

Her legs trembled beneath her, but they held.

She walked to the back wall of the cabin, knelt, and with a piece of broken pottery, carved a single straight line into the dirt.

One, one life taken, one life owed.

It would not be the last number she carved.

And Pine Hollow had no idea what it had created.

The news spread through the slave quarters, not by speech, but by the tremble in hands, by the tightness around eyes, by the way silence suddenly became heavier than chains.

Everyone had heard Rachel’s whale earlier that night, the long shattering cry of a mother whose child had been torn from her arms before she even had time to name him.

No one needed to ask what had happened.

They all knew.

Mistress Caldwell had been desperate for a baby, aching, bitter, hollow.

She had lost three before they drew breath, and another before she finished knitting its swaddling.

When Rachel went into labor, sharpeyed women whispered, “She’ll take that child if she can.

” But hope made fools of them all, because hope was the only thing that kept them breathing.

Now the truth lay cold in Rachel’s empty cabin.

Rachel sat on the floor where the midwife had left her.

The blood had dried on her legs.

The afterbirth soaked the dirt.

She hadn’t moved since her child was snatched from her arms.

Her breath came in short, ragged pulls, almost soundless now, her throat too raw from screaming.

The door creaked open.

It was old Mara, the oldest woman on the plantation.

Bentbacked but sharpeyed.

She had helped raise three generations of enslaved children and buried half of them.

She moved slowly toward Rachel and knelt.

Baby, look at me.

” She whispered.

Rachel didn’t.

Couldn’t.

Her eyes were fixed on the corner where her newborn had lain for less than half a minute.

Still warm, still slick with life before rough white hands took him.

Mara placed a steadying hand on her shoulder.

He’s still breath [clears throat] child.

That mean he’s still yours.

Rachel’s lips trembled.

No, he’s gone.

I ain’t even I ain’t even hold him proper.

Mara’s touch tightened.

That woman don’t get to own what God gave you.

He yours in ways she won’t never understand.

Rachel’s breath hitched.

Something flickered behind her eyes.

Not hope, no, something sharper.

Something forged in loss.

Outside, voices murmured as more slaves gathered quietly.

None entered the cabin.

Not yet, but their presence thickened the air like storm clouds.

They too knew that what had been done tonight had crossed an invisible line.

Then came footsteps, two sets approaching from beyond the cabins.

Everyone froze.

Rachel lifted her head slowly like a ghost rising.

From the doorway stepped Elijah the blacksmith, thick shouldered, soot stained, jaw clenched hard enough to crack bone.

Behind him stood Naomi, who worked in the weaving shed.

Both looked at Rachel with a mixture of pain and fear.

Elijah spoke first.

We heard about mistress.

They say she asleep in the big house.

Rocking your boy in her arms.

The words struck Rachel like a physical blow.

Her fingers curled in the dirt.

Rocking her son like hers as though nothing wrong had been done.

Naomi stepped forward.

Rachel, we ain’t let this pass.

You tell us what you need.

Anything.

But Rachel didn’t answer.

Her gaze unfocused again, drifting to the wall.

No.

Past the wall somewhere distant, dark, unreachable.

Elijah exhaled shakily.

Rachel, say something.

Say you want him back.

At first, she said nothing.

Her breathing slowed.

Her posture straightened.

Her shoulders, trembling minutes before, settled into something terrifyingly still.

Then she whispered, “I want her to feel it.

” The room chilled.

Even Mara pulled back, her breath catching.

Rachel’s voice came again, steadier.

I want her to know what it mean to lose what you love.

Her hands weak as paper moments before, now pressed into the floor with purpose.

She stood slowly, painfully, but she stood.

Rachel, Mara whispered, “Child, don’t go speak in vengeance that path.

” Rachel turned toward her and the look in her eyes silenced the old woman instantly.

This ain’t vengeance.

Her voice was low, calm, final.

This just has been waiting too long.

Elijah swallowed.

What you planning? Rachel looked at him with eyes that no longer held fear.

The mistress took from me.

She paused.

So, I’m taking back everything she ever touched.

Naomi covered her mouth.

Elijah took a step back.

Mara shut her eyes in dread.

Rachel continued, her voice soft but unwavering.

She took my baby in the darkness.

A beat tonight.

Darkness going to take something of hers.

Outside the cabin, the wind shifted.

The torches flickered.

A dog barked and then whed as if sensing a coming storm.

Deep within her chest pain still raw, grief still bleeding.

Rachel felt something ignite.

It wasn’t madness.

It wasn’t hysteria.

It was clarity.

Every heartbeat of her life had been survival.

But now, now she had a purpose.

A woman who has lost everything is not to be feared.

A woman who still has one thing left to reclaim, is unstoppable.

Rachel stepped out of the cabin barefoot, weak, but filled with a steady fire.

The others parted for her without a word.

They didn’t ask questions.

They didn’t need to.

Everyone on the plantation knew the night Rachel lost her child was the night the Caldwell plantation began to die.

The dawn after Ruth’s first escape attempt broke heavy and blue, the kind of morning that seemed to carry sorrow in its mist.

The slave cabins were quiet, too quiet.

The children did not chase each other between the posts.

No hoes struck soil.

No pots clanged.

Even the birds that nested in the cypresses did not sing.

It was as though the whole plantation had held its breath with her because everyone knew a mother who has lost her baby is either a ghost or a storm.

Ruth had chosen to be the storm.

She walked down the dirt path toward the river.

Every step slow, careful, deliberate.

She wore no shoes.

The earth was damp and cold beneath her feet, and her dress was torn at the hem where it had snagged on the thorns the night she had tried to chase after the man who took her newborn.

The memory made her jaw lock so hard it achd.

The others watched her from their cabins, some afraid, some hopeful, all silent.

Even the overseers glanced toward her and muttered curses under their breath.

There was something about her walk, something about her stillness, something about her eyes.

It was as though the river itself had called her.

Ruth stepped into the tall grass, letting the blades brush her legs.

The river was only a few yards ahead, broad and dark, moving with a sluggish weight.

It had always been a place of secrets, where slaves whispered the truth they could not speak in the fields, where blood from lashings washed away, where hope and heartbreak met in swirling eddies of brown water.

She knelt at the riverbank and closed her eyes.

“Child,” she whispered.

“My baby, my baby, where have they taken you?” Her voice cracked, but no tears fell.

She had cried until her eyes were raw.

Now her grief had calcified into something sharper.

She cupped her hands into the cold water, letting it run over her palms.

In the ripples, she imagined she heard her daughter’s weak newborn cry.

The memory stabbed her chest like a blade.

She plunged her hands deeper than froze.

There was a reflection beside her.

An old woman stood behind her, leaning on a carved walking stick.

She wore a faded dress the color of storm clouds, and her hair was wrapped in a scarf patterned with symbols no one in the quarters could read.

But everyone, everyone knew her name.

Goody Mabel, midwife, healer, root worker, the one the white folks pretended not to fear, the one the slaves knew better than to cross.

Ruth stood up quickly, her breath catching in her throat.

“Mama Mabel, I didn’t hear you.

You weren’t meant to,” the old woman said with a voice soft as dry leaves.

“Your mind too loud with pain.

” She stepped closer and traced a finger along Ruth’s cheek.

And pain make the spirits listen.

Ruth swallowed.

“Can they help me? Can they tell me where they took her?” Goodie.

Mabel tilted her head.

They can.

But spirits never speak without asking for a price.

Ruth’s stomach twisted.

What kind of price? part of you,” Mabel said.

“A piece of your fear, a piece of your heart, and a piece of something they took from you long ago.

” Ruth felt her breath hitch.

“I I don’t have nothing left.

” “Oh, child,” Mabel said.

“You got plenty left.

Anger, fire, will, a mother’s promise,” she tapped Ruth’s chest.

“And what hide in here? More dangerous than any weapon.

” Ruth looked back at the river.

“Tell me what to do.

” Mabel nodded slowly as though she had been waiting for those exact words.

You going to walk with me, she said and listened careful.

Cuz what they did to you, it ain’t the first time.

And if you let them keep this baby, it won’t be the last.

Ruth’s hands curled into fists.

I will do anything to get her back.

Mabel’s eyes gleamed.

Then you going to learn how to fight the way they don’t see coming.

Not with fists, not with blades, but with something they too proud.

Too foolish, too blind to understand.

Ana stated.

What is that? Ruth asked.

Mabel’s voice dropped to a whisper.

Patience.

Ruth stiffened.

Patience felt like surrender.

It felt like slow death.

It felt like choking on silence while her child screamed somewhere far away.

I can’t wait, she whispered.

She needs me now.

Mabel’s eyes narrowed, sharp as a knife’s edge.

And you think I don’t know what a mother feels? You think I ain’t lost my own? Patience ain’t about sitting still.

Patience is about moving smart.

She pointed toward the big house.

They watching you now from every window, every shadow.

You run again today.

They break you in a way you don’t come back from.

Ruth’s breath trembled.

She hated that Mabel was right.

You going to get that child back, Mabel said, taking the river water and dripping it onto Ruth’s forehead like baptism.

But first, you going to find out who took her, who ordered it, and where they hit her.

Her voice grew low, and when that truth come out, this whole place going to burn by its own wicked hands.

Ruth didn’t flinch.

She had already started to imagine the flames.

Come sundown, Mabel said.

I’ll show you how to begin.

Ruth rose to her feet.

I’ll be there.

As she walked away from the river, the mist lifted, the sun broke through, and for the first time since her child was stolen, Ruth felt her heartbeat steady into something powerful, something dangerous, not grief, not despair, purpose.

Behind her, Goody Mabel dipped her fingers back into the river and whispered, “She ready now.

” And the water answered with a ripple, shaped like a promise.

The night crept over Harlo Plantation like a living thing, thick, humid, and full of watching eyes.

By the time the moon rose, the whispers had already spread from the cabins to the cane rose to the smokehouse.

Meera was planning something, and this time it wasn’t grief speaking.

It was precision, purpose.

She sat alone behind her cabin, fingers running across the ground as if memorizing the dirt.

The earth here held every memory she could not speak aloud her newborn’s warmth, her own scream, the midwife’s trembling prayer, the cold silence that followed.

Three nights had passed since the baby had been taken.

Three nights of Meera neither sleeping nor crying, only thinking, only sharpening, only remembering.

The plantation believed grief made a woman weak.

But Meera’s grief was fuel.

She felt a presence before she saw it.

Footsteps soft, cautious.

Jonas emerged from the darkness, cap in his hands, worry etched like scars in his brow.

You’ve been quiet, he whispered.

Too quiet, folks.

Say you planning.

Meera looked up slowly.

Her eyes the same eyes Master Harlo had avoided since the night he stole her child glittered like flint.

Tell me, Jonas said softly.

What you going to do? Meera stood, brushing dirt from her palms.

In the moonlight, her shadow stretched long and thin like a blade.

They think I break, she murmured.

Jonas’s breath caught.

Meera, don’t do nothing that get you killed.

She stepped closer, her voice a ghost of steel.

I died already.

Jonas swallowed hard.

Meera continued.

They took my child, my blood, my breath.

Only thing left of me is what I choose to do now.

He looked at her, really looked, then nodded.

Not in approval, but in understanding.

They had all lost something to Harlo.

But Meera’s loss cracked the earth.

From the treeine, another figure approached old Ruth, the healer woman, who had tended Meera after childbirth.

Her cane tapped the earth like a slow heartbeat.

I know that look, Ruth rasped.

Seen it once before.

In a woman who burned a barn full, oh men who hurt her.

Meera, if you step on this road, ain’t no turning back.

Meera held Ruth’s gaze.

There is no road to go back to.

Ruth let out a long quivering sigh.

Then she handed Meera a pouch.

Henbane, she whispered.

Powdered fine, bitter as sin.

Won’t kill a man quick, but it’ll make his body betray him.

Make him see shadows where there ain’t none.

Make his tongue swell, his guts twist.

Jonah stared at Ruth in shock.

You given her poison? I given her choice, Ruth answered.

Meera accepted the pouch and tucked it into the fold of her skirt.

Just then, a shrill creek echoed across the yard.

The main house door swinging open, lantern light spilled onto the steps, and a figure descended.

Mistress Evelyn Harlo, pale, thin as a chicken bone, her voice slicing the air.

Meera, Jonas, and Ruth moved aside.

Mistress Evelyn marched forward, fury bubbling beneath her painted face.

“You have work at dawn,” she hissed.

“Don’t think your little tragedy excuses you from duties.

” Meera’s jaw clenched.

Jonas stepped forward instinctively.

Mistress, she ain’t ready.

Silence.

Evelyn snapped.

She belongs to this household.

She will obey.

Meera said nothing.

Nothing at all.

Her silence seemed to unnerve Evelyn more than any cry would have.

You will be in the laundry by daybreak.

The mistress continued.

And you will keep your eyes down.

I won’t tolerate that defiant stare.

Evelyn’s voice trembled just barely.

She knew Meera’s eyes.

She feared them.

When Evelyn turned to leave, Meera finally spoke soft, low, controlled, “Yes, mistress.

” But the yes held a promise Evelyn did not hear.

As the mistress disappeared into the lantern glow, Jonas whispered, “Mera, you ain’t going to do nothing foolish in that laundry room, are you?” Meera did not answer.

Instead, she walked past him, past Ruth, past the cabins, toward the dark edge of the plantation.

The cotton fields rustled around her as if bowing out of her way.

She reached the abandoned smokehouse, its wooden door hanging crooked, its interior black as a swallowed scream.

She stepped inside and knelt.

Beneath a loose board, she pulled out something she had hidden long before childbirth, long before sorrow, long before loss.

a rusted knife, small but sharp, she brushed her thumb along its edge, feeling it kiss her skin behind her, Ruth’s voice floated in like a warning carried by wind.

Mirror, this road you walk in, even God might not follow.

Meera closed her fingers around the knife.

Then I’ll walk it alone.

Outside, a cold breeze swept across the plantation, strange for a southern night in midsummer.

Dogs began barking in the distance, restless, uneasy.

And as Meera returned to her cabin, a shift settled over the land, not loud, not violent, but unmistakable, a storm was coming.

Not of thunder, not of rain.

A storm born of a mother’s grief and of a vengeance no chain could hold.

Meera lay on her cot, knife hidden, henbane tucked near her heart, staring into the beams of her roof.

The baby she’d never see again seemed to breathe beside her.

“I will find you,” she whispered into the dark.

And for every tear, I cried.

“They will bleed.

” The night held its breath.

The plantation, unaware, unprepared, unprotected, slept under a moon that watched like a silent witness.

Meera was ready.

Tomorrow, the first of them would fall.

Morning on the Harrove plantation usually began with the same cruel rhythm.

whips cracking, overseers shouting, babies crying as their mothers were dragged to the fields.

But on this morning, something was different.

There was a quiet humming under the air.

Something uneasy, like the stillness before a storm breaks.

No one noticed Ruth slip out of the weaving shed.

That was her gift.

After years of being treated as nothing more than a shadow, she had learned to move like one.

Her hands trembled from lack of sleep, but the fire in her chest had not dimmed.

For 3 days, she had not shed a tear for her stolen infant.

She had been beyond tears since the night her child was taken.

Her mourning had sharpened into something else, something cold and exact.

Her revenge had already begun.

The Harrove family didn’t yet know it, but they had been breathing in her fury, stepping through it, eating from it.

Ruth had woven it into the very rhythm of the house.

That morning, the first scream ripped across the yard from the smokehouse.

Sarah Hargrove, the mistress’s eldest daughter, stumbled out, holding her arm.

The flesh along her forearm was blistered and bubbling as though acid had been spilled across her skin.

She shrieked for water, falling into the dirt.

No one understood how the soap she used every morning had been replaced with a mixture strong enough to burn through skin.

Ruth did.

She had ground the lie herself, mixed it with the bitter resin she extracted from a vine that only the oldest Gulla women knew how to find.

She had placed the mixture where Sarah would reach for it automatically.

She had counted the steps.

She had memorized the patterns of the girl’s morning habits.

Revenge was a map, and Ruth walked it carefully, but that was only the first scream.

The second came from the fields.

Two overseers dropped where they stood, writhing, gasping, clutching at their throats.

Their cantens spilled beside them.

The water inside tinted a faint amber.

Ruth had added the tincture the night before, slipping through the shadows with nothing but mud on her feet and grief in her jaw.

The plantation workers paused their picking, frozen between horror and an emotion they hadn’t felt in years.

Hope.

Ruth didn’t look at them.

She couldn’t not yet.

She wasn’t finished.

While chaos spread across the fields, the master himself, Charles Hargrove, stormed down the veranda steps, red-faced, furious, bellowing orders.

He blamed the slaves instantly, promising lashings, punishments, executions.

He had no idea he was already living inside the revenge that would ruin him.

Ruth slipped behind the barn where the old root cellar hid its secrets.

She had been preparing this part for days, crawling through the dark, damp space, placing the last of what she needed in careful rows.

Her hands worked swiftly now.

She knew the exact places where the old beams were weakest, where a single pull could bring down half the structure.

She worked with the precision of a midwife.

After all, this was a kind of birth, a new fate entering the world.

By the time she stepped out again, brushing dust from her dress, the entire plantation was in turmoil.

Slaves had gathered in small clusters, glancing toward the manor, waiting.

Over the years, they had seen suffering, but never disorder like this.

Never the mistress wailing, never the overseers collapsing, never the master running in circles, powerless.

Yet Ruth’s face was calm, eerily calm.

Her child had been stolen in the night.

She had nothing left to lose.

She walked openly toward the front porch where Charles Hargrove stood.

For the first time in years, he noticed her.

Not as a servant, not as property, but as something else, something dangerous.

“What have you done?” he hissed, spittleflying.

Ruth lifted her chin.

She did not speak.

She could not speak, not without choking on her rage.

But she did not need words to answer him.

Behind them, the barn cracked.

The sound rolled across the field like thunder.

Workers turned.

Overseers froze.

Even the horses reared in their stalls.

Harrove spun, confusion etching across his features.

Then the second crack came louder, deeper.

The ground trembled.

Birds burst from the rafters.

And the old barn collapsed into itself with a groaning roar, sending up a cloud of dust that swallowed the yard hole.

Screams erupted.

Live animals trapped inside.

tools shattering, beams splintering, Harrove cursed, running toward the wreckage, shouting orders that no one obeyed.

Ruth watched him run.

She stood at the top of the porch steps, silent and still, her eyes fixed on the man who had stolen her baby from her arms.

She finally whispered, “Not for him, but for herself.

” One, one structure down, one life ruined, one step closer to the child they thought she would forget.

The fields had fallen silent, and the next screams would not be from a barn.

They would be from the master himself.

The plantation woke to the uneasy quiet that comes after a storm, except no storm had passed.

The air felt wrong, too still, as if the land itself were holding its breath.

Overseer Brandt was the first to notice the trail of muddy prints leading from the slave quarters toward the edge of the marsh.

At first glance, they seemed normal, but he felt the hairs on his arms rise.

The steps were too small, too light, too recent, and they led away from the nursery shed.

Elias torren stormed from his house, half-dressed, hair wild, rage pouring from him as though he were a vesper demon.

“Where is the child?” he roared.

His voice shattered the morning calm, sending birds fleeing from the pines.

No one answered.

Not the slaves huddled near the fields.

Not the trembling house servants.

Not the overseers glaring at their boots.

All of them knew the truth.

Even if none dared speak it, Marama had returned in the night and she had taken her baby back.

Brandt cleared his throat, trying to reclaim his authority.

Sir, we should form a search party.

She can’t have gone far.

Elias spun on him, face red with fury.

She was locked in the smokehouse.

How far could she go? Brandt swallowed.

He hadn’t checked the smokehouse himself yet.

When he reached it, Dread pulled in his stomach.

The door hung crooked, the lock hanging by a single twisted screw.

Inside, the chains lay on the floor.

Cut clean almost surgically, far too precise for a slave with no tools.

Cut.

Cut with what? He whispered.

But his question had no answer.

At the edge of the marsh, Elias Torin found something worse.

A scrap of white cloth caught on a brier.

It was the corner of the infant’s swaddling wrap.

It was clean, untouched.

Elias crushed it in his fist.

Marama, he shouted into the trees.

“You wicked creature.

You think you can outrun me? I will tear the marsh apart.

” His voice echoed.

But the swamp answered with silence.

Behind him, the slaves exchanged glances, fear.

Yes, but something else, too.

A spark, a flicker of awe.

A woman had done what none of them had ever imagined possible.

She had outwitted the master and vanished into the night with her child.

And the strange marks in the mud, the long drag lines, the scattered shells, the shallow heel imprints told them the truth.

She had not walked alone.

Back at the big house, Mistress Lucinda trembled as she stood near the window.

She had barely slept, haunted by the memory of Marama’s stare.

That silent burning stare, that vow.

She won’t come back for revenge.

Will she? Lucinda whispered.

Elias didn’t answer because deep down.

He knew Marama knew her fire, her unbreakable spirit.

and he knew the moment they took her newborn, something irreversible had awakened in her.

Something fierce, something ancient.

He spun toward the yard.

“Brandt, assemble every man on this land.

We search until she is found.

” Brandt hesitated.

“Sir, the marsh is dangerous.

People disappear in there.

” Elias’s lips twisted into a snarl.

“Then let her disappear.

Bring me the child.

Bring me the woman dead or alive.

The men dispersed, but no one reached the marsh edge before the first omen appeared.

The dogs refused to go further, whining, tails tucked, backing away as though some spirit stood just beyond the treeine.

The men cursed, pulled, threatened, but the hounds refused.

Then came the second omen.

A long line of reeds tied together with swamp vine lay across the path.

An unmistakable warning in Chasaw tradition.

A boundary, a mark that said, “Cross this and you do not return.

” One of the overseers spat, “Supstitious nonsense.

” He kicked the reed line aside.

Not a minute later, he screamed as something sharp sliced across his ankle.

He dropped to the ground, clutching his leg as blood soaked his boot.

Vines freshly cut lay curled like traps around his foot.

Elias’s face drained of color.

“She’s setting snares,” he murmured.

“She planned this, and she had.

The marsh was her sanctuary.

Her grandmother had taught her its paths, its hiding places, its offerings and warnings.

But more than that, it was where Mararyama had left behind pieces of herself as a girl.

where she and her mother once prayed to spirits older than the landowners, where she learned what it meant to survive.

Now she returned not as a girl, but as a mother with nothing left to lose.

That night, as darkness descended, the men still had found no trace of her.

The marsh swallowed their torches.

Something unseen moved between the trees.

Something quick, something silent.

A whisper drifted across the water, soft yet clear enough that every man felt it crawl along his spine.

“You took my child.

Now I take everything.

” Elias lifted his torch, breath shallow.

Beyond the cattails, two eyes glimmered, reflective, unblinking.

Animal or human, he could not tell.

Then they vanished.

But the message was clear.

Marama was not running.

She was waiting.

Night draped itself over the plantation like a heavy shroud, thick with the smell of ash, damp earth, and the memory of screams.

The flames that had devoured the birthing house were gone now, nothing but skeletal beams jutting from moonlit rubble.

But the silence that followed was louder than any fire, a silence made from fear.

Every slave cabin had its door cracked open.

Every eye watching the dark treeine where they had last seen Marama vanish with her baby wrapped against her chest.

Not one overseer dared step beyond the yard.

Not one dog barked.

The night itself felt as if it were obeying her.

Word had spread like wildfire.

She took her newborn back.

Three overseers fell before they could raise a pistol.

The mistress fainted at the sight of her own burning ledger books.

and the master had not yet been found.

This last detail kept every remaining white face pale and sleepless.

But what no one knew, what only a few trembling slaves whispered, was that the night’s vengeance was not finished.

Far beyond the plantation road, where the swamp water shone like black glass, Maryama knelt beside a cypress stump, her baby, Omari, slept against her breast.

His tiny breath steadied her own heartbeat.

The swamp had become her sanctuary.

It greeted her like kin crickets rasping, frogs croaking, the distant hoot of an owl.

Shadows curled around her in welcome.

She had walked these marsh paths secretly for months while pregnant, memorizing roots, storing herbs, burying tools.

She had prepared long before the plantation’s cruelty took her child.

And now, with Amari safe, she had one final task.

Her fingers traced the rough surface of the stump where she had carved symbols days earlier.

Warnings, prayers, curses, not curses of magic, but of memory.

The names of every child stolen, every mother broken.

Her story would not be carved in sorrow.

Her story would carve back.

Marama stood.

The swamp wind carried a faint sound footsteps.

She knew who they belonged to even before the lantern glow flickered through the trees.

Marama? A trembling voice called, “It’s me, Ruth.

Ruth, the only white girl on the plantation who had shown her mercy.

The one who used to sneak extra food to pregnant women, who had whispered warnings when overseers searched cabins, who had wept when Marama’s newborn vanished.

But mercy from a white girl did not erase the world she belonged to.

” Marama stepped into view.

Ruth gasped, seeing the soot streaking her face, the feral calm in her eyes.

I I had to find you, Ruth whispered.

They blame you for everything.

They’re planning planning to hunt you at dawn.

I know, Marama said quietly.

You can’t go back, Ruth choked.

They’ll kill you.

They’ll take the baby again.

Please, please let me help you escape to town.

There are abolitionists.

No, Marama said, her voice still.

I am not running.

Ruth froze.

Then what? What are you going to do? Marama adjusted the cloth around her baby.

The moonlight caught her eyes dark, unyielding, ancient.

I am going to finish what I began.

Ruth’s face drained of color.

Marama, don’t.

If you go back, there will be blood more than tonight.

Yes, Marama said.

There will, but but they are too many.

No, Marama whispered.

They are too guilty.

A long silence stretched between them, filled with the buzzing of insects and the low sigh of the swamp.

Ruth’s voice finally cracked.

Let me save you.

Marama stepped forward, placed a hand on Ruth’s trembling shoulder, and spoke with a gentleness that cut deeper than any blade.

You cannot save me from a fire I was born inside.

And you cannot save a world that refuses to see me as human.

Ruth covered her mouth, tears spilling.

Then tell me what to do.

Marama picked up the small bundle at her feet.

Her satchel of herbs, glass shards, rope, and the sharpened ho blade she had hidden months before.

Turn back, she said.

And when they ask where I went, tell them the truth.

What truth? That I am coming, Marama said.

And I do not come alone.

As she walked deeper into the swamp, torches flickered in the distance.

The search party was forming early.

Ruth watched her go, heart hammering, torn between terror and awe.

Marama’s whisper drifted back through the trees like smoke.

Tonight the mothers will be heard, important to the turned of Ren, and the swamp swallowed her figure whole, silent, ready, waiting.

The hunt would begin at dawn, but Marama would strike before dawn ever arrived.

Dawn bled slowly over the horizon, washing the ruined plantation in a pale, guilty light.

Smoke threaded through the air like dark ribbons, drifting from the collapsed barn and the scorched fields where the caner overseers had made their last sounds in this world.

But the house large, white, and rotting with secrets still stood, and inside it the final reckoning waited.

Mara walked barefoot through the ashwn yard, her steps slow, deliberate, almost ritualistic.

Her night dress was torn, the hem blackened with soot.

Her braids were undone, falling wild around her shoulders.

But her eyes, her eyes burned with the fury of every mother who ever held an empty cradle.

Around her, other enslaved women quietly stepped from the shadows, their faces lit by the new sun.

They didn’t walk behind her.

They walked with her.

None carried weapons.

They didn’t need any.

Not anymore.

The door to the big house stood a jar hanging crooked from where Mara had smashed it open hours before.

She had come once already in the night when everything began, but she had not gone inside.

Not yet.

The overseers were the first deserving.

But this place, this house, this rotcovered monument to someone else’s power.

This was where the heart of the pain lived, and it was time to stop that heart.

Inside, the halls were silent.

The master and mistress had not slept through the night’s screams.

No one in a 10-mi radius could have.

But they had not shown their faces, not when the horses shrieked, not when the fire bloomed, not when their overseers begged.

Cowards slept lightly.

Mara’s hands brushed the wall as she entered the dining room.

Her fingertips traced the polished wood, the paints imported from France, the polished silver.

All bought with blood, all polished by the exhausted hands of the enslaved.

All worthless now.

The floorboard creaked.

Mara didn’t turn.

She didn’t have to.

I know you’re there, she said softly.

Mistress Caner stepped into view.

Her silk night gown clutched around her throat.

Her hair was loosened from its plat, tangled from a night of terror.

Her eyes were red, swollen, whether from crying or fear, Mara didn’t care to guess.

It was a mistake.

The mistress whispered.

“Whatever happened to your child?” Mara turned her head slowly like a predator considering whether the prey was worth the chase.

“My child,” she repeated, voice flat, deadly calm.

“You took him,” Mistress Caner shivered.

“We we needed to wean him.

” House babies.

house babies.

Mara took one step forward and the mistress stepped backward without thinking.

You drugged me.

You stole him from my arms in the dark.

You told me I’d forget eventually.

Her voice didn’t rise.

It didn’t need to.

The mistress’s back struck the wall.

Her fingers clawed at the wood as if it could save her.

She dared a trembling whisper.

“Your kind have so many.

” Mara moved.

She didn’t strike.

She didn’t choke.

She didn’t drag the woman by her hair.

She simply took the mistress’s face in both hands and held it there firm and chillingly gentle.

“Look at me,” Mara said.

“I I am.

” The mistress stammered.

“No,” Mara whispered.

“Look at what you have done.

” The mistress’s breath caught.

Mara’s expression did not change, but something in the air thickened, darkened like the moment before lightning cracks a tree in half.

The walls seemed to close in.

The silence tightened.

She was right.

Both women turned.

In the doorway stood the master, half-dressed, shaking, his face pale as milk.

In one hand, he held a pistol.

But his wrist trembled so violently the barrel tapped his own knee.

She said, “She said you’d come for us.

” Mara faced him fully now.

“For my baby,” she said.

“Not for you,” the master swallowed.

“I didn’t take him.

” “She did.

” Mistress Kennier gasped in disbelief.

How dare you? You told me,” he shouted, voice cracking.

“You said she wouldn’t remember once we sold him.

” The mistress’s face twisted with horrified betrayal, but Mara wasn’t listening to either of them.

Her heartbeat slowed, softened, steadied.

“Where is he?” she said.

Neither spoke.

So Mara spoke for them.

“You sold him south, didn’t you?” The mistress flinched.

A single tear traced Mara’s cheek.

Silent, hot, unstoppable.

Then she wiped it away with a steady hand.

Nothing in her face changed, but everything inside her did.

She turned toward the doorway and walked away without another word.

The master made a strangled noise.

Where? Where are you going? Mara didn’t pause.

After my son.

You You’re not taking this plantation from us.

He stuttered.

Mara did turn this time one last time and looked at him with something colder than hatred.

No, she said, “You already lost it.

” End quote.

Behind her, the women stepped into the hall.

Their footsteps a quiet thunder.

Mara reached the front door and looked over the yard.

The barns were ash heaps.

The overseers were gone.

The fields were empty.

The plantation was dead.

“Burn it,” she said.

And the women around her moved before the master or mistress could run.

Before they could beg, before they could summon a single excuse to save themselves, flames were already spidering across the porch, crawling up the walls, licking the shutters.

The house that held half a century of suffering began to burn from the inside out.

The master dropped his pistol.

The mistress screamed.

Neither mattered anymore.

Mara didn’t watch the house fall.

She walked toward the open road with the morning sun breaking over her shoulders.

the other women beside her, the fire crackling behind them like an exhaled curse.

News

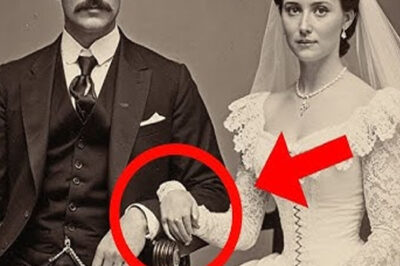

This 1899 Wedding Portrait Looked Innocent — Until Historians Zoomed In on the Bride’s Hand

For more than a century, the wedding portrait sat undisturbed, reproduced in books, cataloged in ledgers, passed over by scholars…

How One Girl’s “Stupid” String Trick Exposed a Secret German Submarine Base Hidden for Years

How One Girl’s “Stupid” String Trick Exposed a Secret German Submarine Base Hidden for Years September 11th, 1943. The coastal…

It was just a wedding photo — until you zoomed in on the bride’s hand and discovered a dark secret

It was just a wedding photo until you zoomed in on the bride’s hand and discovered a dark secret. The…

They Banned His “Rusted Shovel Tripwire” — Until It Destroyed a Scout Car

At 6:47 a.m. on March 12th, 1944, Corporal James Jimmy Dalton crouched in a muddy ditch outside Casino, Italy, watching…

“They’re Bigger Than We Expected” — German POW Women React to Their American Guards

“They’re Bigger Than We Expected” — German POW Women React to Their American Guards Louisiana, September 1944. The train carrying…

German POW Mother Watched American Soldiers Take Her 3 Children Away — What Happened 2 Days Later

German POW Mother Watched American Soldiers Take Her 3 Children Away — What Happened 2 Days Later Arizona, August 1945….

End of content

No more pages to load