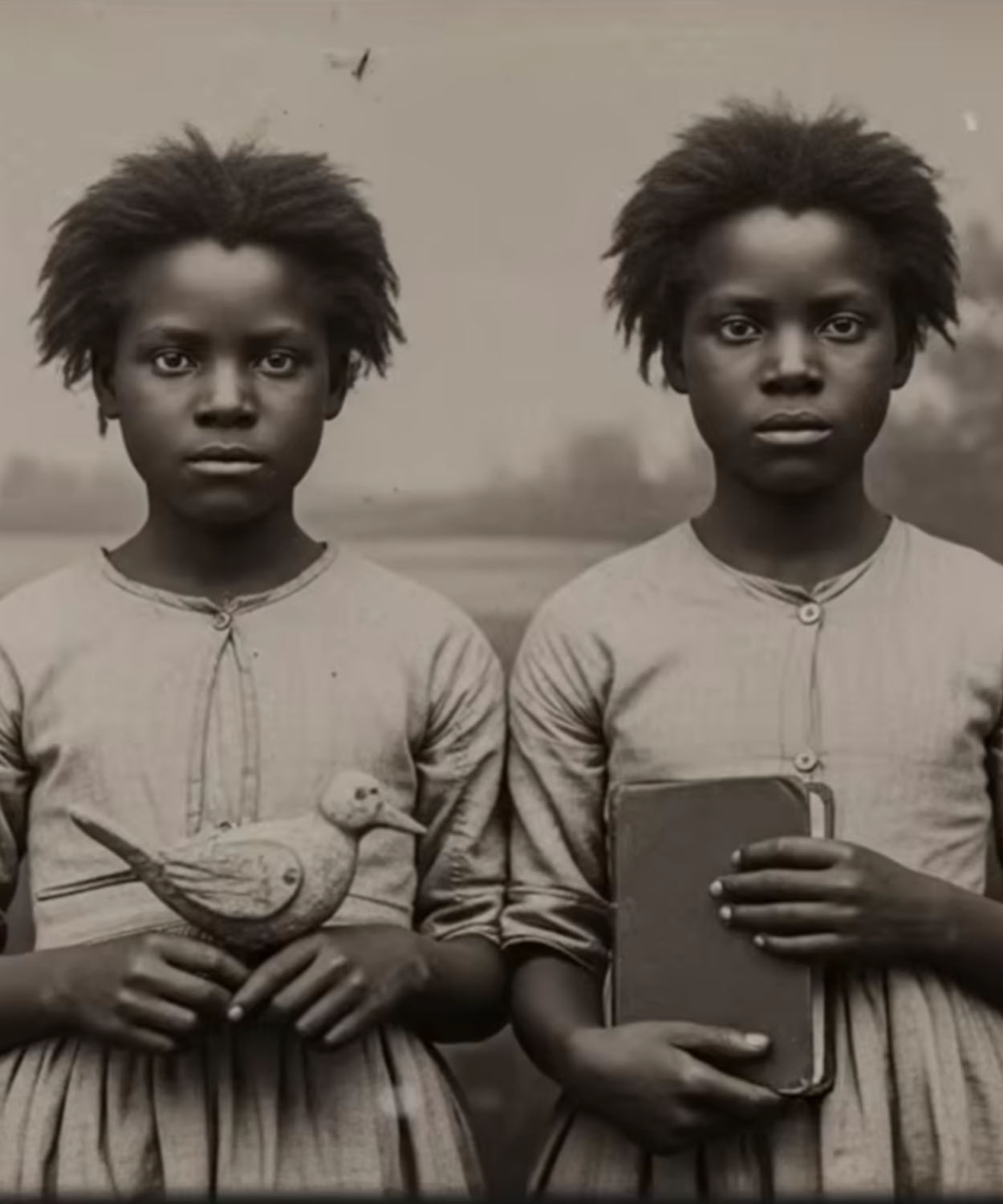

13 Year Old Enslaved Twins Did The Impossible in Georgia That No One Believed

13-year-old girls don’t plan revolutions.

They don’t memorize guard rotations, study architectural weaknesses, or coordinate escape routes for dozens of people.

They don’t outsmart men three times their age who’ve spent lifetimes breaking human spirits.

But in the winter of 1,856 in Chattam County, Georgia, two identical faces studied the Blackwood plantation with eyes that saw not walls, but possibilities, not chains, but patterns, not masters, but men with exploitable habits.

The impossible began on a January morning when those same two faces watched something that would define everything to come.

A woman named Ruth, barely 20 years old, collapsed in the rice fields, exhausted, sick, pregnant.

The overseer, a man named Silas Mohouse, didn’t care about reasons.

He cared about production quotas.

What happened next took three minutes.

Three minutes that planted seeds in two young minds.

seeds that would grow into something Chattam County had never seen before and would struggle to believe even after it succeeded.

Ruth never got up.

The overseer made sure of that.

And Emma and Grace Whitmore, identical twins who’d survived things no 13-year-old should survive, made a decision that morning in the rice fields.

They decided that impossible was just another word for hasn’t happened yet.

Before I continue with what Emma and Grace did that January, I need you to understand something.

This story sits in archives most people will never read.

It’s documented in courthouse records, plantation ledgers, and newspaper accounts from 1,856 and 1,857.

But it’s the kind of history that makes people uncomfortable, so it stays buried.

Now, let me tell you about the Blackwood plantation and the two girls who saw what everyone else missed.

Blackwood sprawled across 1,200 acres of prime coastal Georgia land 8 miles south of Savannah.

The plantation specialized in rice cultivation, which meant something specific and terrible.

Rice plantations were death sentences.

The work happened in standing water, breeding grounds for mosquitoes carrying malaria and yellow fever.

The heat was suffocating.

The labor was backbreaking.

Life expectancy for those forced to work rice fields averaged 7 years after arrival.

Josiah Blackwood owned this empire of misery.

He was 46 years old in January 1856, a third generation plantation owner who’d inherited the property from his father in 1843.

Josiah had expanded operations significantly, increasing production by 40% through methods that didn’t bear close examination.

He was known throughout Chattam County as a shrewd businessman, a committed Methodist, and a man who kept immaculate records of every transaction, every birth, every death, every dollar earned.

His wife, Caroline Blackwood, managed the domestic operations with cold efficiency.

She was 38, educated at a finishing school in Charleston, and she ran the main house like a military commander.

Nothing happened without her knowledge.

Nothing was wasted.

Nothing was forgiven.

The Blackwoods had purchased Emma and Grace in December 1855 from an estate liquidation in Charleston, South Carolina.

The bill of sale listed them as twin females, approximately 13 years, both healthy, trained in domestic service and fieldwork, sold as a pair.

No surnames recorded, no parents mentioned, no history provided beyond what fit on a single line of documentation.

They arrived at Blackwood on December 17th, 1,855 riding in a wagon with 11 other newly purchased people.

The twins showed no emotion as they surveyed their new prison.

Their identical faces revealed nothing, but their identical eyes took in everything.

The head overseer who processed the new arrivals was named Thomas Harlon Ridge.

Ridge was 51 years old, built like a bull with hands scarred from three decades of plantation work.

He’d been at Blackwood for 18 years, earning his position through demonstrated ability to maximize production while minimizing losses.

He understood the economics of human suffering with the precision of an accountant.

Ridge assigned Emma and Grace to work under Caroline Blackwood’s supervision in the main house, kitchen duties, laundry, cleaning, serving.

The twins small size and identical appearance made them useful for household work.

Caroline found them efficient and unsettling in equal measure.

They don’t speak to each other, Caroline mentioned to Josiah one evening in late December.

But they move like they share one mind.

One starts a task, the other finishes it without any communication I can detect.

It’s unnatural.

Josiah dismissed her concerns.

Silent efficiency was preferable to rebellion.

The twins worked without complaint, followed every instruction precisely, and never made mistakes.

Within two weeks, they’d become nearly invisible, just another piece of the household machinery that Caroline operated with such cold competence.

But Emma and Grace were anything but invisible to themselves.

They were watching, learning, cataloging.

They noted which overseers rode which routes at which times.

They observed the hierarchy among those enslaved at Blackwood, identifying who held influence, who harbored resentment, who could keep secrets.

They studied the physical layout of the plantation with the focus of military engineers, learning every building, every path, every vulnerable point in the security systems that kept 347 people imprisoned.

They paid special attention to the guards.

Blackwood employed six armed patrollers who monitored the property at night, rotating on predictable schedules.

Emma and Grace memorized those rotations within 3 weeks.

They identified the gaps, the moments when certain areas went unwatched, the windows of opportunity that lasted only minutes.

What no one at Blackwood understood was that the twins had done this before.

Not at this scale, not with this level of complexity, but they’d survived situations that required observation, pattern recognition, and strategic thinking.

Their history before Charleston was undocumented, but it had clearly educated them in ways that shouldn’t have been possible for girls their age.

The incident with Ruth happened on January 14th, 1,856.

The twins were carrying water to the rice fields, a duty that gave them access to areas beyond the main house.

They witnessed the entire event from 30 yards away.

Ruth had been working since dawn, 6 months pregnant, struggling with fever.

When she collapsed, Silas Mohouse was on her within seconds.

He was 34 years old, the overseer specifically responsible for the ricefield operations.

He was known for violence that went beyond maintaining discipline, violence that seemed to feed something broken in his psychology.

Morehouse kicked Ruth twice, hard enough that everyone within 50 yards heard the impact.

When she didn’t rise, he used his leather strap.

Five blows across her back and shoulders while she lay in the mud and water.

Then he walked away, leaving her there unconscious, face down in 4 in of standing water.

Other workers pulled Ruth from the water before she drowned.

But the damage was done.

She lost the baby that night.

She developed an infection that would kill her within 2 weeks.

Emma and Grace watched all of this without expression.

They stood 30 yards away holding water buckets, their identical faces showing nothing, while their identical minds processed what they’d witnessed and reached the same conclusion simultaneously.

This had to stop, not just for Ruth, for everyone.

And if stopping it required doing the impossible, then they would do the impossible.

That night, lying in their shared sleeping space in the servants’s quarters attached to the main house, Emma whispered to her sister for the first time since arriving at Blackwood.

We can’t kill our way out of this one.

Grace understood immediately.

At their previous location, whatever it had been, violence against individual oppressors had been viable.

But Blackwood was too large, too well-guarded, too systematized.

Killing one overseer would just result in a replacement.

Killing multiple overseers would trigger investigations they couldn’t survive.

They needed something different, something bigger, something that had never been successfully accomplished in coastal Georgia.

We need to get everyone out, Grace whispered back.

Emma nodded in the darkness.

All of them.

At once, what they were contemplating was insane.

Mass escapes didn’t succeed.

The infrastructure designed to prevent exactly this kind of action was too comprehensive.

Armed patrols, tracking dogs, organized slave catcher networks, legal systems that turned every white citizen into a potential enforcer.

The entire apparatus of southern society existed to make what the twins were planning impossible.

But Emma and Grace had learned something that Josiah Blackwood and Thomas Ridge and Silas Mohouse had never considered.

Impossible just meant no one had figured out how yet.

And the twins were very, very good at figuring things out.

Over the next 3 weeks, Emma and Grace studied Blackwood with obsessive focus.

They mapped every building, every fence line, every road and path within 5 mi of the plantation.

They identified the locations of neighboring plantations and their patrol patterns.

They noted the schedules of supply wagons, the timing of visits from merchants and traders, the rhythms of life that governed the broader geography of Chattam County.

They also began building relationships carefully and selectively.

The twins had learned that silence made them trustworthy.

People spoke freely around servants who never talked back, never asked questions, never showed reactions.

Emma and Grace used this.

They listened to conversations between overseers, absorbing information about patrol coordination, communication systems, and response protocols for emergencies.

They learned that Blackwood coordinated with three neighboring plantations on security matters.

They discovered that escaped individuals were typically tracked using dogs kept in kennels 2 mi north of the main house.

They found out that the county slave patrol operated from a central office in Savannah with riders covering designated territories on rotating schedules.

All of this information went into their mental catalog, sorted and analyzed and cross- refferenced until patterns emerged.

But the twins also needed to understand the people they were planning to save.

347 souls lived at Blackwood, and not all of them would be capable of what Emma and Grace were contemplating.

Some were too young, some too old, some too broken by years of systematic dehumanization.

The twins began identifying key individuals, people who still had fight in them, people who could keep secrets and follow instructions, people who could be trusted with the kind of desperate plan that would either succeed spectacularly or fail catastrophically with no middle ground.

They found their first ally in a man named Isaiah.

He was 42 years old, a skilled blacksmith who worked in Blackwood’s Forge.

Isaiah had been at the plantation for 26 years, brought there as a teenager.

He’d survived by being invaluable, his metalworking skills too valuable to risk losing to excessive punishment.

But he’d also survived by remembering every injustice, every cruelty, every person who’d been broken or killed by the Blackwood system.

Emma approached Isaiah on February 3rd, 1,856.

She waited until he was working alone in the forge during the evening hours, then slipped in carrying a basket of bread from the kitchen, a delivery that wouldn’t seem unusual.

Isaiah, she said quietly.

Can you make keys? Isaiah looked at the 13-year-old girl with surprise.

The twins never spoke unless directly addressed.

Hearing one of them initiate conversation was startling enough that he paused his work.

Keys to what? he asked carefully.

“Every lock in this place,” Emma said.

“If I brought you impressions in clay, could you make keys that work?” Isaiah studied her face, seeing something in her eyes that made him reconsider his initial dismissal of the question.

“That would be difficult, risky.

Why would anyone want such things?” “Because locks only keep people in if they can’t be opened,” Emma said.

“And I think it’s time to open every lock in Chattam County.

” The blacksmith set down his hammer slowly.

He looked at this small girl with her identical sister standing silent guard at the forge entrance, and he understood that he was being offered something he’d stopped believing existed decades ago.

Hope.

Tell me your plan, Isaiah said.

Emma did.

Not the full plan.

Not yet, but enough to let Isaiah understand the scope and the ambition.

enough to let him see that these two children had thought further and deeper than anyone would expect.

Enough to make him believe that maybe, just maybe, the impossible was about to become possible.

By the end of February 1,856, Emma and Grace had recruited seven key people.

Isaiah the blacksmith, a woman named Sarah, who worked in the laundry and knew every piece of gossip on the plantation.

a field supervisor named Jacob, who still had the respect of the workers despite being forced to enforce discipline.

Two brothers, Daniel and Marcus, who worked the stables and understood horses better than most men understood people.

a woman named Abigail, who cooked in the kitchen and had access to supplies, and an old man named Thomas, who’d been a sailor before being enslaved and knew the waterways of coastal Georgia like he knew his own hands.

These seven became the core of what Emma was calling the network.

Each of them would recruit others, carefully selected, trustworthy individuals who could be brought into the plan incrementally.

No one would know the full scope except Emma and Grace.

Information would be compartmentalized, distributed on a need to- know basis, protecting the operation if anyone was caught and interrogated.

The twins were building something unprecedented, not a rebellion which would be crushed, not a simple escape which would be tracked down.

They were building an organization, a shadow structure that existed invisibly within Blackwood’s normal operations.

preparing for a single coordinated action that would evacuate 347 people in one night.

But they needed time, they needed resources, and they needed to avoid detection while assembling both.

March brought new challenges.

Josiah Blackwood hired an additional overseer, a man named William Krenshaw from Alabama with a reputation for breaking resistance.

Krenshaw was 38, experienced and suspicious by nature.

He began conducting random inspections, changing patrol patterns, disrupting the predictable routines that Emma and Grace had been relying on.

The twins adapted.

They slowed their recruitment, focusing instead on deepening the commitment of those already involved.

They shifted from gathering information to gathering resources, using their access to the main house to slowly accumulate supplies, small amounts of food that wouldn’t be missed, scraps of cloth that could be sewn into bags, pieces of rope and metal that Isaiah could work into useful tools.

Everything was hidden in locations the twins had identified throughout the plantation.

A hollow space beneath the kitchen floor, a gap in the wall of the servants quarters, the crawl space under the main house where repairs had left structural voids, an abandoned well on the eastern property boundary.

They were building an invisible arsenal, preparing for an operation that would require feeding hundreds of people during a journey that would last days or weeks.

April brought tragedy that hardened everyone’s resolve.

Ruth finally died from the infection that had been killing her since January.

She was buried in the small plot behind the plantation chapel, one more nameless marker in soil soaked with suffering.

Silas Mohouse didn’t attend the burial.

He was in the fields maintaining production quotas.

Emma and Grace stood at that burial, surrounded by people who’d known Ruth, who’d loved her, who’d watched her die slowly and painfully.

And the twins made a silent promise to Ruth’s memory.

This would work.

It had to work because if it didn’t, Ruth’s death would be just one more in an endless series, and nothing would change, and the Blackwoods and the Morehouses would continue grinding people into dust forever.

By May 1856, the network had grown to 43 people.

43 individuals who knew they were part of something, though most didn’t yet know exactly what.

They knew to gather certain supplies.

They knew to memorize certain routes.

They knew to watch certain signals.

They knew to trust the twin girls who moved through Blackwood like ghosts, seeing everything, saying nothing, planning everything.

Emma and Grace had also solved their biggest problem.

Where to go? Thomas the sailor had provided the answer.

80 miles north of Savannah, the Savannah River formed the boundary between Georgia and South Carolina.

But that border was porous, complicated by river islands and swampland that made navigation difficult.

Thomas knew of a network, barely organized, but real, of people who helped runaways cross into South Carolina and continue north.

The Underground Railroad wasn’t a single entity.

It was a loose collection of individuals who, for various reasons, believed that slavery was evil, and were willing to risk everything to help people escape it.

Thomas had heard stories accumulated over decades of safe houses and secret routes.

He couldn’t guarantee they still existed, but he could provide names and locations.

It was enough.

Emma and Grace had their destination.

Now they just needed their method.

The plan that emerged over June and July was breathtakingly complex.

It would require precise timing, coordinated action across multiple locations, and backup plans for every conceivable failure point.

Phase one, neutralize the guards and dogs without killing anyone.

Emma insisted on this point.

Deaths would trigger a massive manhunt, but incapacitated guards would slow response time enough to create the window they needed.

Phase two, open every lock simultaneously.

Isaiah had been working on keys for 4 months using clay impressions that Emma and Grace provided.

He’d created master keys for the quarters where people slept, the storage buildings where supplies were kept, and the stables where horses and wagons waited.

Phase three.

move 347 people 8 miles to the Savannah River using routes that avoided main roads and patrol areas.

This would happen at night with the group divided into smaller units that would travel separately and converge at the river.

Phase four, cross the river using boats that the network would acquire in advance and hide at specific locations.

Thomas would coordinate this part, drawing on his navigation knowledge and the information he’d gathered about helpful contacts on the South Carolina side.

Phase five, disperse.

Once across the river, the group would split up, following different routes north, making tracking impossible.

Some would head for the underground railroad stations Thomas knew about.

Others would try to blend into free black communities in Charleston or further north.

The key was not staying together, not creating a single target.

It was insane.

It required everything to go right and nothing to go wrong.

It depended on weather, timing, human reliability, and pure luck.

The chances of success were microscopically small.

Emma and Grace didn’t care about the odds.

They cared about Ruth.

They cared about the dozens of others who died at Blackwood.

They cared about the 347 people who were still alive and suffering and deserving of a chance, however small, at freedom.

By August 1856, everything was ready.

The supplies were hidden.

The keys were made.

The roots were memorized.

The boats were acquired and concealed.

The network knew their roles.

68 people now formed the core group, each of them responsible for guiding specific others during the escape.

Emma and Grace set the date, September 23rd, 1,856.

A night when the moon would be dark, providing maximum concealment.

A night when Josiah Blackwood would be in Savannah attending a business meeting, reducing the number of people at the main house.

A night when patrol schedules created a three-hour window of reduced coverage on the eastern property boundary.

Everything was ready.

The impossible was about to become real.

Two 13year-old girls who’d survived hell and learned to think like generals were about to attempt something that would be remembered as the largest successful mass escape in Georgia history.

if it worked.

The final three weeks before September 23rd moved with agonizing slowness for Emma and Grace.

Every morning they woke wondering if this would be the day someone talked.

Someone broke under pressure.

Someone revealed the plan that 347 lives depended on.

Every evening they counted down the hours remaining, recalculating risks, reviewing contingencies, preparing for catastrophic failures they hoped would never materialize.

But the twins also had to maintain perfect normaly.

They served meals in the main house with the same silent efficiency they’d shown since December.

They carried out their duties without deviation.

They gave Caroline Blackwood no reason for suspicion.

Gave Thomas Ridge no cause for increased scrutiny.

Gave William Krenshaw nothing to investigate.

The performance required extraordinary discipline.

Emma and Grace were 13 years old, carrying the weight of an operation that would have challenged experienced military commanders, and they couldn’t show strain, couldn’t reveal stress, couldn’t let anyone see the constant calculations running behind their identical faces.

On September 10th, they had their first serious crisis.

William Krenshaw discovered that supplies were missing from one of the storage buildings.

Not large amounts, but enough to notice.

flour, salt, pork, dried beans, the kind of provisions someone might take if they were planning to travel.

Crenaw launched an investigation immediately.

He questioned workers, conducted searches of the quarters, examined storage areas for signs of theft.

He was methodical and thorough, exactly the qualities that made him dangerous.

Emma and Grace watched the investigation unfold with carefully concealed alarm.

Most of their hidden supplies were in locations Cshaw hadn’t discovered yet.

But if he expanded the search systematically, he would eventually find something.

And finding something would trigger the kind of scrutiny that would expose the entire operation.

They needed to redirect his attention, give him an explanation that satisfied his suspicions without revealing the truth.

On September 12th, Emma made a decision that demonstrated the kind of cold calculation that separated the twins from everyone else involved in the network.

She deliberately arranged for Crenaw to discover a small cache of stolen food in the quarters of a man named Peter, a field worker who wasn’t part of the network and had no knowledge of the escape plan.

The discovery was convincing because Emma made it look like Peter had been careless.

She placed the stolen goods in a location that would be found during a routine search, then made sure that search happened by mentioning to Cshaw that she’d seen Peter acting suspiciously near the storage building.

Peter was whipped for the theft.

20 lashes administered by Silas Mohouse while William Krenshaw watched.

Emma and Grace witnessed the punishment from their position serving water to the overseers.

They showed no emotion while watching an innocent man suffer for something he didn’t do.

That night, Grace confronted her sister in their sleeping quarters.

Peter didn’t deserve that.

No, Emma agreed quietly.

He didn’t.

But 347 people deserve freedom.

And if protecting this operation required sacrificing Peter’s back, then that’s the price we pay.

Grace stared at her identical twin, seeing something in Emma’s eyes that troubled her deeply.

A willingness to make calculations that weighed suffering against outcomes that valued the collective over the individual that accepted cruelty as necessary if it served a larger purpose.

“We’re becoming like them,” Grace whispered.

“No,” Emma said firmly.

“We’re becoming what we need to be to beat them.

There’s a difference.

” Grace wasn’t entirely convinced, but she also understood the logic.

They’d come too far, risk too much, built something too important to let moral squeamishness destroy it 11 days before execution.

Peter would heal.

His suffering was temporary.

But if the escape failed because Krenshaw discovered their preparations, hundreds of people would continue suffering forever.

The investigation concluded with Peter’s punishment.

Krenshaw believed he’d found his thief and closed the case.

The missing supplies were attributed to Peter’s greed, and security returned to normal levels.

The crisis had been managed, though at a cost that Grace would remember long after the scars on Peter’s back had faded.

September 15th brought the second crisis, potentially more dangerous than the first.

Josiah Blackwood announced that his business trip to Savannah was being postponed until October.

He would be at the plantation on September 23rd, meaning the main house would be fully staffed and alert during the escape window.

This changed everything.

The twins had planned for reduced presence at the main house, fewer people to notice when 347 others disappeared into the night.

With Josiah present, along with Caroline and the full household staff, detection would come faster and response would be more organized.

Emma and Grace held an emergency meeting with the core network members on September 16th.

They gathered in the forge after midnight, 68 people crowding into a space designed for one, speaking in whispers while Isaiah stood watch at the door.

“We postpone,” Jacob said immediately.

“Wait until Blackwood leaves.

We can’t risk.

” “No,” Emma interrupted.

“We can’t postpone.

The boats are in position.

The supply caches are ready.

Thomas’s contacts expect us on the 23rd.

Change the date now and we have to reconfigure everything, which creates new opportunities for discovery.

But with Blackwood at the main house, Sarah began.

We adjust, Grace said, speaking for the first time in the meeting.

We don’t change the fundamentals, we add a new component.

The twins explained their adaptation quickly.

Instead of relying on Blackwood’s absence to reduce detection speed, they would actively delay it.

On the night of September 23rd, after everyone else had departed, Emma and Grace would remain behind temporarily.

They would create a diversion in the main house that would occupy Josiah, Caroline, and the household staff for critical hours while 347 people moved through the darkness toward the Savannah River.

“What kind of diversion?” Isaiah asked carefully.

“The kind that holds their attention completely,” Emma said.

“Don’t worry about the details.

Just know that when you’re leading people east toward the river, the Blackwoods will be too occupied to notice you’re gone until it’s too late to matter.

The network members looked at these two 13-year-old girls who spoke with the authority of generals and made decisions with the coldness of executioners, and they realized something profound.

Whatever had formed Emma and Grace before they arrived at Blackwood, it had created something unprecedented.

two children who thought like strategists, planned like engineers, and acted with a moral flexibility that allowed them to do whatever was necessary to achieve their objectives.

“Trust us,” Grace said quietly.

“We’ve brought you this far.

Trust us to finish it.

” The meeting concluded with the plan intact.

September 23rd remained the target date.

The network would execute as designed and the twins would handle the Blackwood problem personally.

Over the next seven days, Emma and Grace finalized their preparations with obsessive attention to detail.

They reviewed every element of the plan with the core network members, ensuring everyone understood their roles.

They verified that all supplies were positioned correctly.

They confirmed with Thomas that the boats were ready and his contacts on the South Carolina side were prepared.

They also prepared their diversion, though they shared the specifics with no one except each other.

What they were planning for the main house was dangerous, possibly fatal, and absolutely necessary.

The Blackwoods needed to be completely occupied for at least 4 hours.

4 hours for 347 people to travel 8 mi through darkness and reach the river.

4 hours before anyone discovered the quarters were empty and the entire enslaved population of Blackwood Plantation had vanished.

September 22nd, the day before execution, brought unbearable tension to everyone involved in the network.

68 core members moved through their normal routines while battling anticipation and fear.

They served meals, worked fields, performed duties, all while knowing that in 24 hours everything would change forever.

Emma and Grace maintained their characteristic calm, but those who knew them best could detect subtle signs of strain.

They moved slightly faster than usual, their eyes tracked details with even greater intensity.

They touched each other frequently, a rare display of the connection that usually remained invisible, as if drawing strength from physical contact with their identical twin.

That evening, after the household staff had finished their duties and retired to their quarters, Emma and Grace lay in their shared sleeping space and had their final private conversation before the operation began.

If this works, Grace said quietly, we’ll have done something no one thought possible.

It will work, Emma said with certainty that didn’t entirely match the odds.

And if it doesn’t, then we’ll have tried.

That’s more than most people can say.

Grace was silent for a moment, then asked the question that had been troubling her since the incident with Peter.

Do you think we’re good people? After everything we’ve done, everything we’re planning to do, Emma considered this carefully.

I think good and evil are words people use when they don’t want to think about complexity.

We do what’s necessary.

We protect people who can’t protect themselves.

We fight systems that grind human beings into dust.

Does that make us good? I don’t know.

Does it matter? It matters to me, Grace said.

Then believe this,” Emma replied, turning to face her sister in the darkness.

Tomorrow night, 347 people will have a chance at freedom they wouldn’t have otherwise.

Some will make it, some won’t.

But all of them will know that two girls who barely reached their 14th year cared enough to try the impossible.

History can judge whether we were good or evil.

The people we save won’t care about the distinction.

Grace nodded slowly, accepting this logic, even if it didn’t entirely satisfy her moral questions.

They had come too far to turn back now.

Tomorrow would bring either triumph or catastrophe, and philosophical debates about goodness wouldn’t change the outcome either way.

September 23rd, 1,856 dawned with cloudless skies and unseasonable heat.

Emma and Grace performed their morning duties with mechanical precision, serving breakfast to the Blackwood family, cleaning rooms, carrying out the routines they’d executed hundreds of times over the previous nine months.

Josiah Blackwood was in particularly good spirits that morning.

Cotton prices were rising, rice production was exceeding projections, and his plantation’s profitability was at an all-time high.

He discussed expansion plans with Caroline over breakfast, while the twins served coffee and eggs, invisible as always, two more pieces of human property that existed to facilitate the comfort of their owners.

Neither Josiah nor Caroline noticed the way Emma’s hands trembled slightly when pouring coffee.

Neither saw the look that passed between the twins when Caroline mentioned that tonight would be a quiet evening at home, just family, no guests or social obligations.

Perfect, Emma thought.

Absolutely perfect.

The day progressed with agonizing slowness.

Every hour felt like three.

Every interaction with overseers or household staff carried the weight of potential discovery.

Emma and Grace moved through their duties while tracking the son’s position, counting down to sunset, reviewing mental checklists of tasks and contingencies.

At 4:00 in the afternoon, Caroline Blackwood gave the twins an assignment that initially seemed like a complication, but turned into an unexpected advantage.

She wanted the main house’s dining room prepared for a special dinner that evening.

fine china, silver cutlery, candles, the full formal service.

Josiah’s brother was arriving unexpectedly from Charleston, and Caroline wanted to demonstrate appropriate hospitality.

This meant Emma and Grace would be working in the main house during the critical evening hours.

It meant they would have legitimate reasons to move through the building, accessing areas they needed to access, positioning materials they needed to position.

The diversion they’d planned just became easier to execute.

At 6:30, as sunset painted Chattam County in shades of orange and red, the final preparations began throughout Blackwood Plantation.

To any observer, it looked like a normal evening, workers returning from fields, meals being prepared, the daily rhythms of plantation life continuing as they had for decades.

But beneath that surface normality, 68 core network members were executing their assigned tasks with precise coordination.

Isaiah was distributing the keys he’d spent months creating.

Sarah was ensuring everyone knew their designated travel groups and routes.

Jacob was organizing the field workers, making sure the elderly and children were paired with strong adults who could assist them.

Daniel and Marcus were preparing the horses and wagons they would use for the first phase of movement, vehicles that would carry those unable to walk 8 miles through darkness.

Thomas was conducting his final check of the supply caches along the escape route, verifying that food and water waited at predetermined intervals.

Abigail was distributing the last provisions from the kitchen, amounts small enough not to be noticed missing, but sufficient to sustain people during the journey.

Everything was moving according to plan.

347 people who’d been told only that tonight is the night, follow your group leaders, trust the plan, were preparing for something they didn’t fully understand but desperately hoped would work.

At 7:15, Josiah’s brother arrived from Charleston.

His name was Marcus Blackwood, 42 years old, owner of a cotton plantation outside the city.

He brought news of commodity prices, political developments, and social gossip.

The dinner conversation would likely last hours, keeping Josiah and Caroline occupied at the table.

Emma and Grace served the meal with flawless precision.

Soup, fish, roasted pork, vegetables, multiple courses requiring constant attention and service.

They moved between dining room and kitchen, silent and efficient, while the Blackwood brothers discussed business, and Caroline managed the conversation with practiced social grace.

At 8:40, full darkness had settled over the plantation.

The moon, as predicted, was barely a sliver, providing minimal light, perfect conditions for what was about to happen.

At 8:45, Isaiah unlocked the first door.

The quarters where 60 people slept now standing empty because everyone was already gathered outside waiting.

The lock opened silently, the key working perfectly, exactly as Isaiah had designed.

At 8:50, Jacob began moving the first group toward the eastern property boundary.

30 people moving in silence through the darkness, using routes that Emma and Grace had identified months earlier.

They traveled with practiced quiet years of survival instinct, telling them exactly how to move without attracting attention.

At 9:00, the second group departed, then the third, then the fourth.

Like water flowing through channels, 347 people began flowing out of Blackwood Plantation in coordinated streams, each group following designated routes toward convergence points near the Savannah River.

Daniel and Marcus moved the wagons at 9:15, carrying the elderly, the very young, and those too sick or injured to walk.

The wagons wheels had been wrapped in cloth to muffle sound.

The horses had been trained for weeks to respond to minimal guidance.

Everything that could be planned had been planned.

Now it came down to execution and luck.

At 9:30, Emma and Grace were still serving dessert in the Blackwood dining room.

The brothers were deep in conversation about tariff policy, a topic that apparently required extensive discussion.

Caroline was listening with the patient attention of someone who’d mastered the art of appearing interested.

At 9:45, the last group departed Blackwood.

Every quarter stood empty.

Every work building sat abandoned.

347 people had evacuated in exactly 1 hour, moving through darkness toward the most uncertain future imaginable, but a future they would control themselves rather than having it dictated by masters who valued them as property.

At 10:00, Emma and Grace began their diversion.

It started subtly, so subtly that no one noticed immediately.

A candle knocked over in the kitchen, landing near some drying towels.

The twins had positioned those towels carefully earlier in the evening, soaked them in cooking oil, arranged them where a fallen candle would ignite them within seconds.

The fire started small, just smoke at first, barely noticeable, but smoke in a wooden building carries, and within 3 minutes, someone in the main house noticed the smell.

By the time Caroline Blackwood called for investigation, the kitchen was fully involved.

Flames were climbing walls, consuming the dry wood with terrifying speed, generating heat that could be felt from 30 ft away.

Chaos erupted immediately.

Josiah and Marcus ran from the dining room.

Caroline began shouting orders.

The household staff scrambled to respond, grabbing buckets, organizing a water brigade, trying to contain fire that was already beyond containment.

Emma and Grace, covered in soot and appearing panicked, ran toward the house, screaming that the fire had started from the kitchen stove.

That they’d tried to put it out, but it had spread too fast.

That they were sorry, so sorry.

They’d failed in their duties.

No one questioned them.

No one suspected.

Two 13-year-old girls crying and terrified, covered in smoke and ash, obviously traumatized by the disaster they’d accidentally caused.

They were victims of the fire, not perpetrators.

The kitchen burned completely.

The flames spread to an adjacent storage building before the water brigade managed to contain them.

It took until midnight to fully extinguish the blaze and ensure it wouldn’t reignite.

During those critical hours between 1000 p.

m.

and midnight, while Josiah and Caroline and Marcus and the entire household staff fought to save the main house from burning, 347 people traveled 8 m through darkness and reached the Savannah River.

Thomas was waiting at the river with the boats, exactly as planned.

12 small boats acquired over months through careful transactions and hidden in inlet vegetation.

Not enough to carry everyone simultaneously, but enough to ferry people across in organized groups.

The crossing began at 11:30.

Thomas coordinated with the precision born of decades on water, organizing groups by size and weight, ensuring boats weren’t overloaded, maintaining spacing to avoid collisions in the darkness.

The Savannah River at this point was nearly a/4 mile wide, moving with steady current.

Crossing required skill and courage, especially in darkness, with no lights to guide navigation.

But Thomas knew these waters.

He’d studied them for months in preparation for this exact moment.

By 1:00 a.

m.

, the first groups were reaching the South Carolina shore.

Contacts that Thomas had identified were waiting, people whose opposition to slavery ran deep enough to risk everything, helping strangers escape.

These conductors would guide the escapees to safe houses, provide food and direction, help them continue north toward uncertain but chosen futures.

By 2:00 a.

m.

, more than half of the 347 had crossed.

The operation was working.

The impossible was happening.

Everything that Emma and Grace had planned over 9 months of careful preparation was executing with remarkable precision.

Back at Blackwood, the fire was finally under control.

The kitchen was a total loss.

The adjacent storage building had suffered major damage, but the main house had been saved, and no lives had been lost in the blaze.

Josiah Blackwood stood in the smoke-filled yard, surveying the destruction, calculating the financial impact of losing buildings and supplies.

He was angry, but also pragmatic.

Buildings could be rebuilt.

Supplies could be replaced.

The important thing was that the main house stood intact.

It wasn’t until 3:00 a.

m.

when someone finally thought to check the quarters that discovery came.

The messenger who ran to inform Josiah could barely get the words out, “Sir, they’re gone.

All of them.

Every quarter is empty.

Every building.

There’s no one here.

347 people gone.

” The words didn’t make sense initially.

Josiah’s exhausted mind struggled to process what he was hearing.

Gone.

All of them.

How? Then understanding hit with the force of physical impact.

The fire wasn’t an accident.

It was a diversion.

While he’d been fighting to save his property, his human property had been disappearing into the night.

“Get Ridge!” Josiah shouted.

“Get every overseer.

Get the patrol.

Get the dogs.

Get everyone now.

” By 3:30, organized pursuit began, but it was already too late.

347 people had a 5 and 1/2hour head start.

They’d crossed into South Carolina.

They’d dispersed into multiple groups following different routes.

Tracking them all was logistically impossible.

The dogs found trails leading to the river, but the water crossing had destroyed the scent.

Patrols rode through the night searching, but they had no specific direction to focus on.

The escapees had vanished as completely as if they’d never existed.

And Emma and Grace, they stayed at Blackwood.

They played their roles perfectly.

Two frightened girls who’d accidentally started a fire and were devastated by the consequences.

They cried when questioned.

They trembled when Josiah shouted.

They convinced everyone who saw them that they were victims of circumstances beyond their control.

No one suspected.

How could they? 13-year-old girls couldn’t plan and execute the largest mass escape in Georgia history.

The idea was absurd on its surface, but they had.

And by the time the sun rose on September 24th, 1,856, 347 people were free, and two identical faces were watching from the main house windows as patrols returned empty-handed, knowing they’d accomplished something that would echo through history.

the impossible had happened.

And it had happened because two 13-year-old girls refused to accept that impossible meant anything other than no one’s done it yet.

The morning of September 24th brought chaos that bordered on panic throughout Chattam County.

Word of the Blackwood escape spread with terrifying speed, carried by riders who galloped between plantations, by merchants traveling roads towards Savannah, by the informal networks of communication that connected the entire infrastructure of slavery.

347 people gone vanished in a single night.

The news created fear that went far beyond economic loss.

This wasn’t a handful of individuals running for freedom.

This was a mass evacuation coordinated and executed with precision that suggested planning, organization, and leadership.

If it could happen at Blackwood, it could happen anywhere.

The foundation of the entire system suddenly felt less stable.

Josiah Blackwood stood in his smoke damage study at dawn, surrounded by overseers and the county sheriff, a man named Robert Talbbert.

Talbert was 56 years old, a career law enforcement officer who’d spent three decades maintaining order in Chattam County.

He’d dealt with runaways before many times, but never anything approaching this scale.

How is this possible? Talbert asked, his voice containing genuine bewilderment.

347 people don’t just disappear.

Someone had to organize this.

Someone had to plan it.

Find them,” Josiah said, his voice cold with controlled rage.

“I don’t care what it costs.

Mobilize every resource.

Contact authorities in South Carolina.

Alert the slave catchers.

Put rewards on every single one of them.

Find them.

” The investigation that followed was the most intensive ever conducted in coastal Georgia.

Talbert brought in experienced trackers from three counties.

He coordinated with South Carolina law enforcement.

He interviewed everyone who remained at Blackwood trying to identify who might have had knowledge of the escape plan.

Emma and Grace were questioned on September 25th.

Talbert spoke to them in the main house parlor with Caroline Blackwood present.

The twins sat with perfect posture, their identical faces showing appropriate fear and confusion.

“Did you see anything unusual in the days before the escape?” Talbert asked.

Anyone gathering supplies? People meeting in unusual places? Conversations that seemed suspicious? “No, sir,” Emma said quietly.

“Everyone just did their regular work.

We were mostly in the main house, so we didn’t see much of what happened in the quarters.

” “The fire,” Talbbert continued.

“Tell me exactly how it started,” Grace explained, her voice trembling with what appeared to be genuine distress.

“We were cleaning the kitchen after dinner service.

There were so many candles because of the special meal for Mr.

Marcus, one of them.

I think Emma bumped the table when she was carrying dishes.

The candle fell near some towels.

The fire spread so fast.

We tried to stop it, but she broke down crying.

Emma reached over and held her sister’s hand.

Both girls presenting a picture of traumatized children overwhelmed by catastrophe they’d accidentally caused.

Talbert looked at these two small girls and saw exactly what they wanted him to see.

Victims.

Frightened servants who’d made a tragic mistake.

The idea that they could have deliberately created the fire as a diversion for a mass escape never entered his consideration.

Children didn’t do such things, especially not children who appeared this fragile and traumatized.

The investigation continued for weeks, expanding to cover neighboring counties and extending into South Carolina.

Trackers followed cold trails that led nowhere.

Patrols searched forests and swamps without finding any trace of the missing 347.

Rewards were posted, but no one came forward with useful information.

By midocctober, the uncomfortable truth was becoming clear.

The escaped individuals had successfully scattered.

They’d reached destinations where tracking was impossible.

They’d vanished into the vast geography of the American South, blending into free black communities, connecting with underground railroad networks or simply disappearing into places where no one would think to look.

The economic impact on Josiah Blackwood was catastrophic.

347 people represented an investment of approximately $200,000 in 1856 currency.

Losing that entire workforce in a single night was financial devastation that threatened bankruptcy.

Insurance didn’t cover mass escapes.

No compensation existed for this kind of loss.

Blackwood was forced to sell significant portions of his land to cover debts.

The plantation that had been one of the most profitable in Chattam County became a shadow of its former operation.

By December 1856, Josiah employed only 43 people purchased at steep prices in a market that had seen dramatic inflation following the September escape.

But the financial impact was secondary to the psychological impact.

The escape demonstrated something that plantation owners throughout the South found deeply threatening.

The enslaved population could organize.

They could plan.

They could execute complex operations with precision that rivaled military campaigns.

The assumption of helplessness that underlay the entire system had been shattered.

Throughout November and December of 1,856, plantation security across Georgia underwent dramatic changes.

Guards were increased.

Patrols were reorganized.

New restrictions were implemented on movement and gathering.

The response to the Blackwood escape was systemwide fear that manifested as increased oppression.

Emma and Grace watched these developments with mixed feelings.

Their operation had freed 347 people, an unqualified success by any measure.

But it had also triggered responses that made life harder for thousands of others still trapped in the system.

The twins understood cause and effect, and they accepted responsibility for both intended and unintended consequences.

What they didn’t know yet was whether their network members had successfully reached safety.

The plan had called for no communication for at least 6 months, protecting everyone involved by creating no traceable connections.

The twins had to wait, wondering if Isaiah made it north, if Sarah found freedom, if Jacob and Daniel and Marcus and Abigail and Thomas had survived the journey they’d all risked everything to attempt.

The waiting was harder than the planning had been.

In January 1857, 4 months after the escape, Emma and Grace received their first indirect confirmation that at least some of their people had made it.

A traveling merchant visited Blackwood, a man who regularly brought supplies from Savannah.

He was speaking with Caroline Blackwood about recent news when he mentioned an interesting rumor he’d heard in Charleston.

They’re saying a whole community of former slaves has established itself somewhere in Pennsylvania.

The merchant said maybe 300 people, all claiming to have come from Georgia plantations.

Authorities up there won’t return them.

Of course, Pennsylvania doesn’t recognize our property rights.

Just thought you might find it interesting given what happened here.

Emma, serving tea during this conversation, showed no reaction, but her heart was racing.

300 people from Georgia, Pennsylvania.

It could be coincidence, or it could be confirmation that the network had reached destinations where they could build new lives.

That night, Grace whispered to her sister in their sleeping quarters, “Do you think it was them?” “Some of them,” Emma said.

“Not all.

300, not 347.

” “Some didn’t make it.

Some went different directions, but yes, I think a significant number reached Pennsylvania.

” “We did it,” Grace said, her voice containing wonder and relief.

“We actually did it.

We did it,” Emma confirmed.

And now we need to decide what we do next.

This question had been occupying both twins thoughts for months.

They’d accomplished their objective at Blackwood.

They’d proven that mass escape was possible.

But they remained enslaved themselves, still property of Josiah Blackwood, still trapped in a system they demonstrated could be beaten, but not yet destroyed.

They could run.

With their demonstrated skills and the resources they’d built during nine months of preparation, escape would be relatively easy.

But running meant abandoning everyone else, still suffering under the Blackwood system and at plantations throughout Chattam County.

Or they could stay, use their unique position as trusted servants, whose involvement in the September escape had never been suspected, build another network, plan another impossible operation.

The decision wasn’t difficult.

Emma and Grace hadn’t survived their unknown previous experiences just to save themselves.

They developed capacities for strategic thinking and operational execution that were wasted on personal escape.

They were weapons that could be aimed at a system that deserved to be destroyed piece by piece.

They would stay, they would plan, and they would do it again.

February 1,857 brought new arrivals to Blackwood.

Josiah had purchased 23 people from various sources trying to rebuild his workforce.

These new arrivals provided Emma and Grace with fresh recruitment opportunities.

Not everyone would be suitable, but the twins had learned to identify the signs of intelligence, resilience, and willingness to take extraordinary risks.

They began rebuilding their network with even greater care than before.

The first escape had succeeded partially through luck.

A second operation would face heightened security and increased suspicion.

Everything would need to be more sophisticated, more carefully hidden, more perfectly executed.

By March, the twins had recruited five core members from the new arrivals.

Not enough for a mass escape, but enough to begin planning something different.

If they couldn’t evacuate everyone simultaneously again without triggering the kind of security response that would make success impossible, perhaps they could execute a series of smaller operations, 10 people at a time, moving through carefully established routes, spacing the escapes to avoid pattern recognition.

But in April 1857, everything changed.

Sheriff Talbbert received a letter from authorities in Pennsylvania.

The letter contained testimony from several individuals who’d escaped from Blackwood on September 23rd, 1,856.

They were providing information in exchange for asurances they wouldn’t be returned to Georgia.

The testimony detailed the escapees organization.

It named core network members.

It described the planning process, the supply caches, the route coordination, and it mentioned briefly but definitively that two young twin girls who worked in the main house had been present at planning meetings and had appeared to have detailed knowledge of the operation.

Talbert read this testimony with growing certainty.

He’d questioned those twins.

He dismissed them as traumatized children.

But the letter from Pennsylvania suggested he’d made a catastrophic error in judgment.

On April 15th, 1,857, Talbert returned to Blackwood Plantation.

He requested another interview with Emma and Grace, this time without Caroline present.

He wanted to observe them without the protective presence of their owner.

The twins understood immediately that something had changed.

Talbert’s demeanor was different.

He watched them with an intensity that suggested suspicion rather than routine questioning.

His questions were more pointed, designed to test consistency with previous statements.

Tell me again about the planning meetings, Talbbert said carefully.

The ones that supposedly happened before the escape.

Did you ever see groups gathering in unusual locations? No, sir, Emma said, maintaining perfect composure.

We were usually in the main house during evening hours.

But you delivered food to the forge sometimes, didn’t you? Talbert pressed.

I have documentation that kitchen servants brought meals to Isaiah when he was working late.

Yes, sir.

Grace confirmed.

Sometimes we brought bread or water to workers in various buildings.

Did you ever see anything unusual during those visits? Anything that seemed out of place? The twins understood the trap.

Talbbert had information that contradicted their previous claims of ignorance.

He was testing whether they would maintain their story or adapt it.

Either response carried risks.

Emma made a decision that demonstrated the strategic thinking that had characterized every action since arriving at Blackwood.

She would give Talbbert partial truth, enough to satisfy his suspicions without revealing the full scope of their involvement.

There were some nights, Emma said slowly as if reluctant to share information when we saw people gathering at the forge.

We didn’t understand what they were doing.

We were scared to ask because it seemed like something we weren’t supposed to see.

Why didn’t you report this? Talbert asked.

Because we were afraid, Grace said, her voice trembling in a performance of fear that was partially genuine.

We’re just children.

We didn’t know if what we were seeing was wrong, and we were scared of being punished for speaking about things that weren’t our business.

Talbert studied the twins carefully.

Their explanation was plausible.

Frightened children who’d witnessed something suspicious, but hadn’t understood its significance and had been too scared to report it.

It fit the profile he’d constructed of them as victims rather than perpetrators.

But Talbbert was also a experienced investigator.

Something about the twins perfect composure, the way they never contradicted each other.

The precision of their responses troubled him.

These weren’t normal 13-year-old girls.

They were too controlled, too calculated, too intelligent.

I think, Talbert said carefully, that you know more than you’re telling me.

I think you were involved in the escape.

Perhaps not as leaders, but as accompllices who provided information or assistance.

No, sir, Emma said firmly.

We’re just servants.

We do what we’re told.

We don’t plan things or organize things.

We’re children.

The word children was emphasized deliberately.

Emma was reminding Talbot of the fundamental absurdity of his suspicions.

How could children enslave children with no power or authority orchestrate an operation that had defeated every security measure in Chattam County? Talbert wanted to believe they were involved.

His instincts told him these twins were more than they appeared, but instincts weren’t evidence, and without evidence, he couldn’t act on suspicions that seemed increasingly ridiculous when stated plainly.

He left Blackwood on April 15th without making any arrests or formal accusations, but he also left with certainty that Emma and Grace knew more than they admitted.

He would watch them and he would wait for them to make a mistake.

The twins understood their situation had changed fundamentally.

They were now under suspicion.

Any unusual activity would be scrutinized.

Any connection to future escape attempts would immediately point back to them.

Their value as invisible operators had been compromised.

That night, Emma and Grace had the most serious conversation of their lives.

“We can’t stay,” Grace said.

“Talbert suspects us.

If anything else happens, we’ll be blamed.

They’ll investigate us properly this time.

” “I know,” Emma agreed.

“But we also can’t leave the people we just recruited.

We promised them we’d help them escape.

Then we help them escape by getting them connected to the roots we established.

Grace suggested we provide information, resources, contacts, but we don’t stay here where we’re under surveillance.

Emma considered this carefully.

It violated her preference for maintaining direct control over operations.

But it also acknowledged reality.

Sometimes the best contribution was providing tools and information rather than trying to manage everything personally.

We need to create something sustainable, Emma said slowly.

Not just escape routes that work once, but systems that can continue without us.

Networks that other people can operate.

Information that gets passed from person to person, even after we’re gone.

This idea evolved over the following weeks into something more ambitious than either twin had initially conceived.

Instead of planning another mass escape, they would create infrastructure, document the routes they’d established, record the names and locations of helpful contacts, compile information about security patterns, patrol schedules, and safe passages, create a manual essentially for conducting successful escapes.

But documenting this information created massive risk.

If the documentation was discovered, it would provide evidence of everything.

Talbbert suspected it would expose the entire network, past and present.

It would result in prosecutions, executions, and systemwide crackdowns.

The twins needed to hide their documentation in ways that made discovery nearly impossible while still making the information accessible to people who needed it.

They found their solution through Abigail, the cook, who’d been part of the original network and had successfully escaped to Pennsylvania.

Before leaving, Abigail had taught several younger women her cooking techniques, passing down recipes and methods.

Emma and Grace realized they could do the same thing, not with cooking, but with escape planning.

They would teach their knowledge to trusted individuals, person by person, ensuring the information existed in multiple minds rather than single documents.

They would create human libraries, people who memorized roots and contacts and methods.

The knowledge would become oral tradition, passed from person to person, impossible to destroy by burning papers or seizing documents.

May and June of 1,857 were spent in careful education.

The twins identified 12 individuals among the new arrivals and remaining workers at Blackwood who showed the intelligence and commitment necessary to preserve and transmit complex information.

They taught these 12 everything they knew about planning escapes, coordinating movement, identifying security vulnerabilities, and connecting with helpful contacts.

Each of the 12 was instructed to teach at least two others, creating exponential spread of knowledge throughout networks that extended beyond Blackwood to plantations across Chattam County and eventually throughout Georgia.

Emma and Grace were building something unprecedented.

Not just escape routes, but an educational system that transformed enslaved people into strategic thinkers capable of planning and executing their own liberation.

By July 1857, the twins understood their work at Blackwood was complete.

They’d freed people directly.

They’d educated dozens more in methods that would enable hundreds of additional escapes.

They’d created knowledge systems that would persist long after they were gone.

It was time to leave.

Not just Blackwood, but Georgia entirely.

The twins had learned through their network that Pennsylvania offered opportunities for free black individuals, including children.

Philadelphia, in particular, had communities that would accept them, schools that would educate them, possibilities that couldn’t exist in the South.

They planned their departure for August 23rd.

Exactly one year after the mass escape, the symmetry appealed to both twins sense of narrative structure.

They would leave the same way they’d helped others leave, traveling at night along routes they’d established, connecting with contacts they’d cultivated, moving toward freedom they’d earned through extraordinary effort and risk.

On August 22nd, the day before their planned departure, Emma and Grace performed their duties at the main house with the same silent efficiency they’d maintained for 20 months.

They served meals, cleaned rooms, fulfilled every expectation.

They gave Josiah and Caroline no reason for suspicion, no indication that by the next evening they would be gone.

That night, lying in their sleeping quarters for the last time, the twins reviewed their achievements with quiet satisfaction.

347 freed directly, Emma whispered.

At least 60 more educated in escape methods.

Knowledge spread to hundreds.

Infrastructure created that will last for years.

Not bad, Grace said softly.

For two 13year-old girls that no one took seriously.

14 now,” Emma corrected.

“We turned 14 in January, though I suppose no one thought to celebrate.

We’ll celebrate in Philadelphia,” Grace said.

“When we’re free, when we’ve built new lives, when we can finally stop pretending to be helpless children.

Do you think we’ll ever stop planning?” Emma asked.

“Even when we’re free, even when we’re safe, will we be able to just exist? Or have we become what we needed to be?” so completely that we can’t go back to being normal.

Grace considered this question seriously.

I think we were never normal.

Whatever happened to us before Charleston, before Blackwood, it formed us into something different.

We can’t go back because there’s nothing to go back to.

We can only go forward.

Then forward it is.

Emma said, “Tomorrow night, Pennsylvania, freedom, and whatever comes after, August 23rd, 1,857, began like any other day at Blackwood Plantation, which was precisely how Emma and Grace intended it.

They rose before dawn, prepared breakfast for the main house, served Josiah and Caroline with the silent efficiency that had made them nearly invisible over 20 months of careful performance.

But this morning carried weight that only the twins felt.

Every task was being completed for the last time.

Every interaction was a final performance.

By sunset, they would be gone, and Blackwood would become just another chapter in their carefully hidden history.

The day moved with agonizing slowness.

Emma and Grace executed their duties with mechanical precision while tracking the sun’s progress across the sky, counting down hours until darkness would provide the cover they needed.

At 4 in the afternoon, Sheriff Talbert arrived at Blackwood unannounced.

The twins were in the kitchen when they saw him ride up the main drive, and identical expressions of concern crossed their faces.

Talbert’s visits were never casual.

He came when he had information or suspicions worth pursuing.

Caroline received him in the parlor, and Emma served tea while Grace stood by with additional refreshments.

The twins maintained perfect servant posture, eyes downcast, bodies positioned to be available but not intrusive.

“I’ve received additional correspondence from Pennsylvania,” Talbbert said, accepting his tea without looking at Emma.

More testimony from individuals who escaped last September.

They’re providing increasingly detailed accounts of the planning and execution.

Have you learned anything useful? Caroline asked.

Several things, Talbert confirmed, including descriptions of the people who led the planning meetings.

Two individuals are mentioned repeatedly.

A blacksmith named Isaiah and he paused, letting the silence build deliberately.

two young girls who apparently had detailed knowledge of security patterns, patrol schedules, and main house operations.

The words hung in the air like smoke from the fire that had destroyed Blackwood’s kitchen 11 months earlier.

Emma’s hand trembled slightly as she set down the tea service, a reaction that could be interpreted as fear or nervousness, but was actually controlled performance of exactly those emotions.

You’re not suggesting, Caroline said slowly, that Emma and Grace were involved.

They’re children.

They barely speak unless spoken to.

The idea is absurd.

Is it? Talbert asked, turning to look directly at the twins for the first time.

I’ve been investigating this case for nearly a year.

I’ve interviewed dozens of people.

I’ve tracked leads across three states.

And do you know what I’ve learned? The most dangerous assumptions are the ones about who’s capable of what.

He stood and walked toward Emma and Grace, studying their identical faces with an intensity that made the moment feel like an interrogation despite the parlor’s civilized setting.

“Tell me something,” Talbbert said quietly.

“If you were planning a mass escape, if you needed to gather intelligence about security and schedules and vulnerabilities, who would you use as your agents? strong men who’d be noticed moving around, or small girls who everyone ignores because they’re just servants.

Emma met his gaze directly, abandoning the downcast eyes that signaled submission.

When she spoke, her voice carried a steadiness that contradicted her 14 years.

Sheriff Talbbert, you’re suggesting that two enslaved children outsmarted every overseer, every guard, every security measure in Chattam County.

You’re proposing that we planned and executed an operation that freed 347 people under your watch.

Does that seem likely to you? The directness of her response surprised Talbert.

This wasn’t how enslaved girls spoke to white authorities.

The very fact that she would challenge his premise, even politely, suggested a confidence that supported rather than contradicted his suspicions.

I think, Talbert said carefully, that unlikely things happen more often than we acknowledge.

I think people underestimate children, especially girls, especially enslaved children.

And I think that underestimation creates opportunities for those smart enough to exploit it.

Then we’re much cleverer than anyone’s given us credit for,” Grace said, speaking for the first time, her voice matching her sister’s steady tone.

Though if we were really that clever, why would we still be here? Wouldn’t we have escaped with everyone else? This question was the twins strongest defense, and they both knew it.

Their continued presence at Blackwood after the mass escape was the single fact that most contradicted Talbert’s theory.

If they’d been central to planning the operation, logic suggested they would have fled with their network.

Unless, Talbert thought, they stayed specifically because leaving would confirm suspicions.

Unless they understood that remaining behind, playing the role of innocent servants traumatized by events beyond their control, provided the perfect cover for guilt.

He wanted to arrest them.

His instincts screamed that these two girls were exactly what the testimony from Pennsylvania suggested.

Brilliant strategic minds who’d orchestrated the largest successful escape in Georgia history.

But instinct wasn’t evidence.

And arresting them without evidence would make him look foolish while potentially allowing the real organizers to escape scrutiny.

I’ll be watching you, Talbert said finally.

both of you.

If anything unusual happens, if anyone else disappears, if there’s any indication of planning or coordination, I’ll know where to look first.

We’re just servants, sir,” Emma said, returning to the submissive tone and downcast eyes.

“We do what we’re told, and nothing more.

” Talbert left Blackwood that afternoon, convinced the twins were guilty, but unable to prove it.

He’d played his hand too early, revealing his suspicions before gathering sufficient evidence.

It was a tactical error that he’d regret for years.

Emma and Grace understood the encounter had changed everything.

Talbert was watching them now.

Leaving as planned would seem like confirmation of guilt, but staying meant living under constant surveillance, unable to move freely, unable to help the people they’d recently recruited.

They made their decision in the kitchen after Talbbert departed.

They would leave tonight as planned, but they would ensure their departure looked nothing like an escape.

They would create a scenario that deflected suspicion while giving them the freedom they’d earned.

At 7 that evening, Emma approached Caroline Blackwood with a request that seemed to come from genuine distress.

“Ma’am,” she said quietly, “myister and I, we’re frightened.

Sheriff Talbbert thinks we were involved in the escape.

We weren’t, but he doesn’t believe us.

We’re scared he’s going to arrest us just to close his investigation.

Caroline studied Emma’s face, seeing what appeared to be genuine fear.

The twins had been model servants for 20 months.

They’d never caused problems, never shown defiance, never given any indication they were anything other than obedient children.

Sheriff Talbert can’t arrest you without evidence, Caroline assured her.

You have nothing to worry about.

But what if he makes up evidence? Grace asked, joining her sister.

What if he needs someone to blame and we’re convenient? We’re just property.

No one would question if he took us.

This concern was actually valid.

Enslaved people had no legal protections against false accusations.

If Talbbert decided to arrest them for the escape, regardless of actual evidence, they would have no recourse.

“Please,” Emma said, and her voice carried what sounded like desperate pleading.

“Could we be sold to someone far from here? Somewhere Sheriff Talbbert’s investigation doesn’t reach.

We’ll work hard.

We promise.

We just don’t want to be arrested for something we didn’t do.

” Caroline Blackwood was not a sentimental woman, but she also recognized practical reality.

The twins were valuable property, and their value would be compromised if they were arrested in connection with the escape investigation.

Selling them to a buyer in another state would remove them from Talbot’s reach while recovering their purchase price.

I’ll speak with Mr.

Blackwood, Caroline said.

We may be able to arrange something over the next 3 days.

The Blackwoods arranged to sell Emma and Grace to a cotton merchant from Alabama who was traveling through Savannah.

The merchant, a man named Edward Thornnehill, purchased the twins for $1,200, slightly below market value, but acceptable given the circumstances.

The sale was documented, legally transferred, and completed on August 26th, 1,857.

Emma and Grace were placed in Thornhill’s wagon for transport to Alabama, and they departed Blackwood Plantation with Sheriff Talbbert watching from a distance, frustrated, but unable to prevent a legitimate property transfer.

What Talbbert didn’t know was that Edward Thornnehill was not actually a cotton merchant from Alabama.

He was a Quaker abolitionist from Philadelphia who occasionally traveled south under false identity, purchasing enslaved people and transporting them to freedom.

His network had been contacted by the twins months earlier through channels established during the mass escape planning.

The sale was elaborate theater designed to remove Emma and Grace from Georgia legally with documentation that would prevent pursuit or recovery attempts.

By the time Talbbert realized what had happened, if he ever did, the twins would be in Pennsylvania with papers declaring them free.

The journey north took 3 weeks.

Thornnehill transported Emma and Grace along with seven others he’d purchased from various locations, maintaining his merchant cover until they crossed into Pennsylvania on September 16th, 1,857.

Philadelphia in 1857 was a city of contradictions.

It offered opportunities for free black residents that didn’t exist in the South, but it also maintained deep racial prejudices and segregation.

Emma and Grace entered this complex environment with the same strategic thinking they’d applied to everything else.

They needed education, employment, and community.

Thornnehill’s network helped with initial placement, connecting them with a Quaker family who provided housing in exchange for domestic work while the twins attended school.