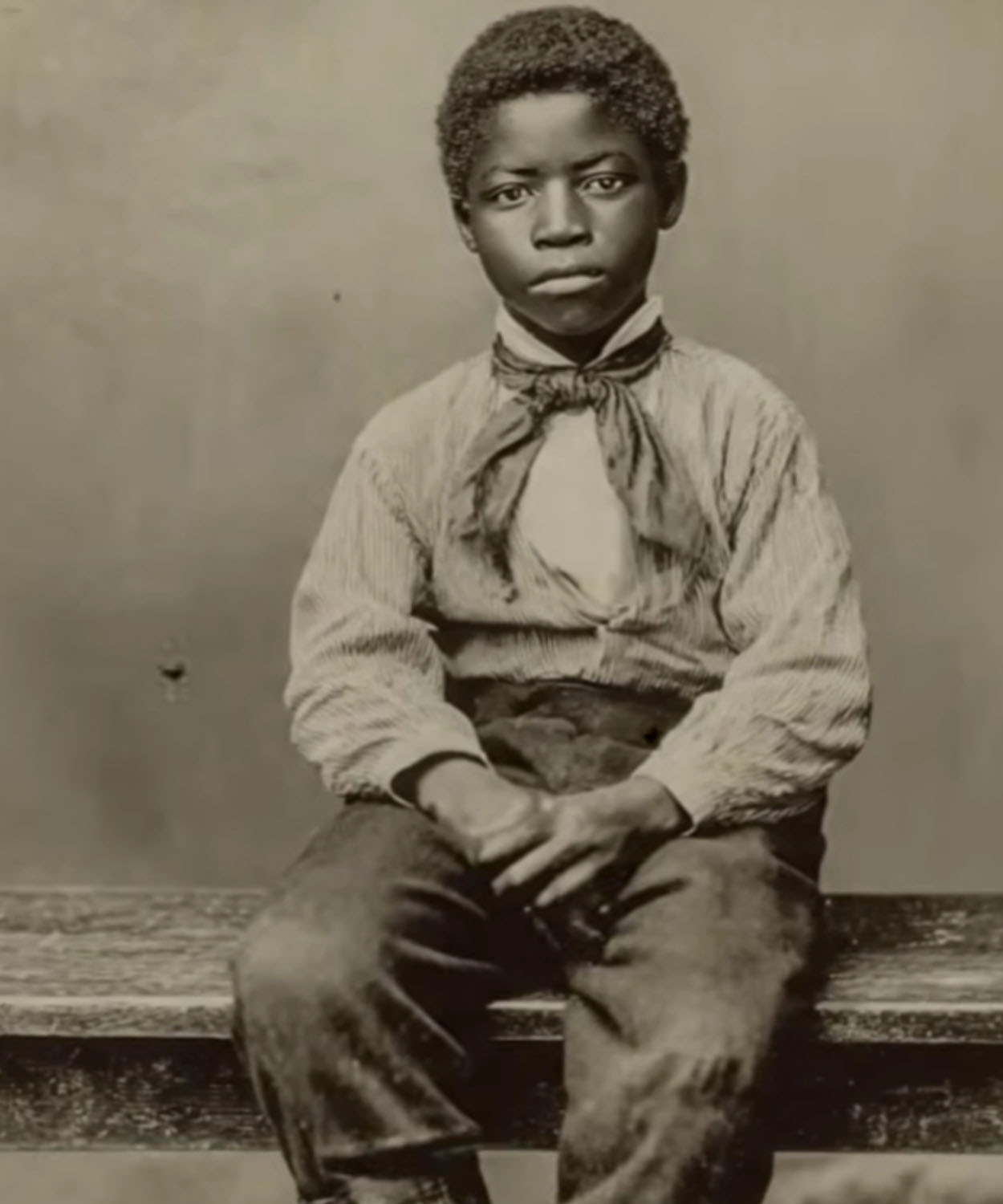

Today’s story takes us to 1851, where we follow Moses Grant, a black boy born into slavery who was said to speak with the dead.

A mystery that science has never been able to explain.

This is a disturbing and intense story rooted in fear, silence, and unanswered questions.

In the summer of 1851, in a remote corner of Edgefield County, South Carolina, something happened that would shake the foundations of an entire community.

Something that doctors could not explain.

Something that preachers refused to accept, something that the wealthy plantation owners of the region tried desperately to bury along with the bodies of those who had witnessed it.

This is the story of Moses Grant, a boy who was born into chains.

A boy who could hear voices that no one else could hear.

A boy who became the most terrifying weapon the dead had ever found.

And before this story ends, powerful men will fall.

Secrets buried for decades will rise to the surface.

And the screams of those who thought they had gotten away with murder will echo through the Carolina night.

But we need to start at the beginning.

We need to understand the world Moses Grant was born into.

Because without understanding that world, you cannot understand why what happened next was so extraordinary.

The year is 1851.

The place is the Witmore plantation about 12 miles outside of the town of Edgefield.

This was cotton country, rich dark soil that seemed to stretch forever under a brutal southern sun.

The kind of land that made men wealthy beyond imagination.

The kind of land that was soaked in blood.

The Whitmore plantation covered nearly 3,000 acres.

It was owned by a man named Cornelius James Witmore, the third generation of Witors to work this land.

His grandfather had cleared the first trees in 1792.

His father had expanded the operation, buying up neighboring farms during the economic panic of 1819, and Cornelius himself had turned the plantation into one of the most profitable operations in the entire Edgefield district.

By 1851, Cornelius Whitmore owned 237 enslaved human beings.

237 men, women, and children who woke before dawn and worked until their bodies gave out.

237 people who had no legal rights, no protection, no hope of freedom.

Among those 237 souls was a woman named Abigail Grant.

Abigail was 28 years old in 1851.

She had been born on this same plantation, just like her mother before her.

She worked in the fields during planting and harvest season and in the main house during the winter months.

She was known among the other enslaved people as a quiet woman, a careful woman, a woman who kept her head down and her thoughts to herself.

But Abigail Grant carried a secret that kept her awake most nights.

A secret that made her hands tremble when the overseers came too close.

A secret that she had protected for 11 years with every ounce of strength she possessed.

Her son Moses was different.

Moses Grant was born on the 14th of March 1840.

It was a difficult birth.

Abigail labored for nearly 18 hours in the cramped cabin she shared with four other women.

The plantation’s doctor was not called.

Enslaved women were expected to deliver their children with only the help of other enslaved women.

Medical attention was reserved for complications that threatened to damage the master’s property.

When Moses finally came into the world just before midnight, he did not cry.

The midwife, an older woman named Kora, who had delivered more than a hundred babies on this plantation, held the infant up, and waited.

Nothing.

She turned him over, patted his back.

Still nothing.

Abigail, exhausted and terrified, reached for her child, and the moment her fingers touched his skin, Moses opened his eyes and looked directly at his mother.

not the unfocused gaze of a newborn, a clear, knowing look that made Kora take a step backward.

He still did not cry.

Kora would later tell the other women in the quarters that she had never seen anything like it.

Most babies came into the world screaming.

This one came into the world watching, like he was already looking at something the rest of them could not see.

For the first two years of his life, Moses seemed like any other child born in the quarters.

He learned to walk.

He learned to speak a few words.

Passed on their horses.

He cried when he was hungry and laughed when Abigail tickled his stomach.

But when Moses turned three, things began to change.

It started small.

Moses would sit in the corner of the cabin and carry on conversations with empty air.

Abigail assumed he had an imaginary friend the way some children do.

She did not think much of it.

Then one evening, Moses pointed to the fireplace and said a name.

Claraara.

He said it clearly like he was greeting someone who had just walked into the room.

Abigail felt her blood turned to ice.

Claraara had been her mother’s name.

Claraara Grant had died of fever 7 years before Moses was born.

Abigail had never spoken that name to her son.

She had never even mentioned that she had a mother.

In the world of the plantation, you learned early not to talk about the people you had lost.

There were too many.

The grief would drown you.

Abigail knelt in front of her son.

She asked him who Claraara was.

Moses smiled and pointed again at the fireplace.

He said that Claraara was the nice lady who sang to him at night.

the one who sat beside him while he slept.

Abigail did not sleep that night or the next.

Over the following months, Moses continued to speak about Claraara.

He described her in detail.

Tall, thin, a scar on her left hand from a burn she got when she was young.

Abigail’s mother had that exact scar.

She had gotten it at age 12 when she accidentally touched a hot kettle in the main house kitchen.

There was no way Moses could have known about that scar.

No way at all.

As Moses grew older, the incidents multiplied.

He spoke about people who had died long before he was born.

He described events he could not possibly have witnessed.

One afternoon when he was 5 years old, Moses told his mother that the old man who lived by the creek wanted to tell his daughter he was sorry.

He was sorry for not fighting harder when they took her away.

Abigail asked, “What old man?” Moses described him.

Short, missing two fingers on his right hand, walked with a limp.

Abigail recognized the description immediately.

The man Moses was describing was Samuel Tucker.

Samuel had been sold to a plantation in Mississippi 12 years earlier.

He had died during the journey somewhere in Alabama.

His daughter Ruth had been sold in the opposite direction to a family in Virginia.

Samuel Tucker had died before Moses was born.

There was no portrait of him.

No written record, no way for a 5-year-old child to know what he looked like or what had happened to his family, unless someone had told him.

Unless Samuel Tucker himself had told him.

Abigail made a decision that night.

She sat Moses down and explained to him as carefully as she could that he must never speak about the people he saw.

Never.

Not to anyone.

Not to the other children.

Not to the women in the quarters.

Not to anyone at all.

Moses asked why.

Abigail struggled to find the words.

How do you explain to a child that the gift he has been given could get him killed? How do you tell him that the white people who owned them feared nothing more than what they could not understand? How do you make him see that a black child who claimed to speak with the dead would be beaten, tortured, possibly murdered, and certainly sold to the most brutal plantation his master could find.

Abigail told Moses that some things were meant to be kept secret.

She told him that the people he saw were his friends, but they had to stay his secret friends.

She told him that if he ever spoke about them to anyone outside their cabin, something very bad would happen.

Moses was a smart child.

He understood that his mother was frightened and he loved his mother more than anything in the world.

So, he promised to keep the secret.

For 6 years, Moses kept that promise.

He still saw the dead.

They came to him almost every night.

They whispered to him during the day while he worked in the fields.

They gathered around him like moths around a flame.

But Moses learned to control his reactions.

He learned not to look directly at them when others were watching.

He learned to answer their whispers in his mind instead of out loud.

By the time Moses was 11 years old, he had become an expert at hiding.

On the surface, he appeared to be a quiet, obedient child.

The overseers barely noticed him.

He did his work.

He kept his head down.

He was invisible.

But beneath that surface, Moses carried the weight of hundreds of souls.

Every enslaved person who had died on the Witmore plantation over the past 60 years had found their way to him.

They told him their stories.

They showed him their deaths.

They shared with him their rage and their sorrow and their desperate need to be remembered.

Moses listened to them all, and he kept their secrets just as he kept his own.

Everything changed on the night of August 17th, 1851.

The head overseer on the Whitmore plantation was a man named Jonas Caldwell.

He was 43 years old, originally from Tennessee, and he had been working for Cornelius Whitmore for 11 years.

In that time, he had earned a reputation as one of the most brutal overseers in Edgefield County.

Jonas Caldwell believed that fear was the only tool that kept enslaved people in line.

He used his whip freely and without provocation.

He had killed at least four enslaved people during his tenure, though officially these deaths were recorded as accidents or illnesses.

He separated families for minor infractions.

He withheld food as punishment.

He was by any measure a monster.

The enslaved people on the Witmore plantation lived in constant terror of Jonas Caldwell.

They whispered his name like a curse.

They prayed that he would fall from his horse.

They dreamed of the day when his cruelty would catch up with him.

On the night of August the 17th, those prayers were answered.

It was just past midnight when the screaming began.

The sound came from the overseer’s cottage, a small wooden house about 200 yd from the main quarters.

The screaming was raw and primal, the kind of sound a man makes when he is facing something beyond his comprehension.

Several enslaved men were the first to arrive at the cottage.

They found the door standing open.

Inside, Jonas Caldwell was lying on the floor in front of the fireplace.

He was dead.

There was no blood, no sign of violence, no obvious cause of death.

Jonas Caldwell simply lay there, his eyes wide open, his face frozen in an expression of absolute terror.

His mouth was still open from the final scream that had torn from his throat.

The other overseers arrived within minutes.

They examined the body.

They searched the cottage.

They found nothing.

No weapon, no sign of struggle, no indication of what had happened.

The plantation doctor was summoned from his bed.

He examined Jonas Caldwell by lamplight and declared himself baffled.

The man’s heart had simply stopped.

There was no medical explanation.

It was as if Jonas Caldwell had been frightened to death.

By morning, the entire plantation was buzzing with speculation.

The white overseers huddled together, speaking in low voices.

The enslaved people whispered among themselves, hardly daring to believe that their tormentor was truly gone.

And then Moses Grant made a mistake.

He was working in the field that morning, picking cotton alongside his mother and about 30 other enslaved people.

The overseer who had replaced Caldwell for the day was a younger man named Peters.

Peters rode up and down the roads, watching for anyone who slowed their pace.

Two enslaved men near Moses were talking quietly about what had happened.

They were speculating about how Caldwell had died.

One thought it was his heart.

The other thought someone had poisoned him.

Moses without thinking spoke up.

He said that nobody had poisoned Jonas Caldwell.

He said that Caldwell had seen something.

Something that came through his wall just after midnight.

Something that walked toward him even though it had no legs below the knee.

Something that reached out with hands that were missing fingers.

Moses said that Jonas Caldwell had recognized the thing that came for him.

He had recognized him because he was the one who had cut off those fingers with an axe eight years ago.

Right before he beat that man to death behind the tobacco barn, Moses said the dead man’s name was Henry.

And Henry had waited 8 years for this night.

8 years of watching, 8 years of building up enough strength to cross over.

Eight years of planning exactly how he would make Jonas Caldwell pay.

Moses said that Henry had wrapped his broken hands around Caldwell’s throat.

Not to choke him, just to show him, just to make him see, just to force Caldwell to look into the eyes of a man he had murdered and forgotten.

Moses said that Caldwell’s heart had given out after about 2 minutes.

He said that by the end Caldwell was crying and begging for mercy.

He said that Henry did not give him any.

When Moses finished speaking, he looked up and found every person in the row staring at him in absolute silence.

He realized too late what he had done.

Word spread through the quarters within hours.

By that evening, everyone on the plantation had heard some version of the story.

the strange boy in the fields.

The one who had described Jonas Caldwell’s death in detail that no living person could have known.

The one who had named a man called Henry who had been beaten to death years ago.

The older enslaved people remembered Henry.

His name was Henry Rollins.

He had been killed in the summer of 1843 when Moses was just 3 years old.

The official story was that Henry had fallen from a hoft and broken his neck.

But everyone knew the truth.

Everyone knew that Jonas Caldwell had murdered him for stealing food from the main house kitchen.

How had an 11-year-old boy known about Henry Rollins? How had he known about the fingers? How had he known what happened behind the tobacco barn? There was only one explanation, and that explanation terrified everyone.

Abigail found her son hiding in their cabin that afternoon.

She was shaking with fear.

She grabbed Moses by the shoulders and demanded to know what he had been thinking.

Why had he spoken? Why had he broken his promise? Moses did not have an answer.

He said that Henry had been standing right next to him in the field.

He said that Henry had been waiting so long for someone to know what had really happened.

He said that he could not help himself.

Abigail knew that it was too late.

The secret was out and it was only a matter of time before it reached the main house.

It took less than 24 hours.

Cornelius Whitmore heard the story from one of his house servants on the morning of August 19th.

At first, he dismissed it as foolish superstition.

The enslaved population was always spinning tales about spirits and curses and things that went bump in the night.

It was part of their culture, part of their way of making sense of the brutal world they lived in.

But something about this particular story nagged at him.

Cornelius called for his personal servant, a man named Thomas, who had been with the family for 30 years.

Thomas was as close to trusted as any enslaved person could be.

Cornelius asked him about the boy in the fields, the one who was saying strange things.

Thomas hesitated.

He knew that any answer he gave could put Moses in danger, but he also knew that refusing to answer would put himself in danger.

After a long pause, he told Cornelius what he had heard.

Cornelius listened without interrupting.

When Thomas finished, Cornelius sat in silence for several minutes.

Then he made a decision that would change everything.

He did not order Moses beaten.

He did not order him sold.

Instead, Cornelius Witmore ordered Moses brought to the main house.

Cornelius Witmore was 57 years old in 1851.

He had spent his entire life in the South Carolina cotton country.

He had inherited his fortune, expanded it, and built one of the most successful plantation operations in the region.

He was a practical man, a businessman.

He did not believe in ghosts or spirits or any of the superstitious nonsense that the enslaved population whispered about.

But Cornelius Whitmore did believe in money, and he had just realized that the boy named Moses might be worth more than all the cotton in his fields.

The spiritualism movement had been sweeping through America for 3 years now.

It had started in New York in 1848 when two young sisters named Kate and Margaret Fox claimed to communicate with spirits through a series of mysterious knocking sounds.

The Fox sisters had become famous.

They had toured the country performing seances for paying audiences.

They had spawned hundreds of imitators.

By 1851, spiritualism had become big business.

Wealthy families across the north and south were paying substantial sums to attend seances and contact their deceased loved ones.

Mediums were in high demand.

The ability to speak with the dead had become one of the most valuable talents a person could possess.

And here on Cornelius Whitmore’s own plantation was a boy who seemed to have that exact talent, a boy who was his property.

Moses was brought to the main house on the afternoon of August 20th.

He had never been inside the big house before.

He had only seen it from a distance, a white columned mansion that seemed to belong to a different world than the cramped wooden cabins where he lived.

Two overseers escorted him through the back entrance, through a long hallway, and into a sitting room where Cornelius Witmore waited.

Moses had seen the master before, always from far away.

Up close, Cornelius Whitmore was smaller than Moses had expected.

He was a thin man with gray hair and cold blue eyes.

He wore a black suit despite the August heat.

He did not stand when Moses entered the room.

For a long moment, Cornelius simply stared at the boy.

Moses kept his eyes on the floor the way he had been taught.

Then Cornelius spoke.

He asked Moses if the stories were true.

Could he really speak with the dead? Moses did not answer immediately.

He thought about his mother.

He thought about the promise he had broken.

He thought about all the years he had spent hiding his gift from the world.

He looked up and met Cornelius Whitmore’s eyes.

Moses said, “Yes.

” Cornelius leaned forward.

He asked Moses to prove it.

Moses was silent for a moment.

Then he began to speak.

He said there was a woman standing behind the master’s chair, an older woman with white hair and a blue dress.

She was the master’s mother.

She had died in this very room in that very chair 11 winters ago.

She wanted the master to know that she forgave him for not being there when she passed.

She wanted him to know that she understood why he had stayed in Charleston that week.

Business was business.

She had always told him that.

Cornelius Whitmore’s face went pale.

His mother had died in December of 1840.

She had been sitting in that very chair when her heart gave out, and Cornelius had indeed been in Charleston on business.

He had not made it home in time to say goodbye.

It was one of his deepest regrets.

There was no way the boy could have known any of that.

The enslaved people were not told about family matters.

They were not informed when white family members died or where they died or what the circumstances were.

Moses continued.

He said that there were others in the room too.

Many others.

The house was full of them.

They had been here for a long time.

Some of them had died in this house.

Some had died on the land.

They were all watching now.

They were curious about what would happen next.

Cornelius asked what would happen next.

Moses said he did not know.

That was up to the master.

Cornelius Witmore stood up from his chair.

He walked to the window and looked out at his cotton fields stretching to the horizon.

He stood there for a long time thinking.

Then he turned back to Moses and told him exactly what would happen next.

Moses would be moved out of the quarters.

He would be given a room in the servants’s wing of the main house.

He would be fed better food.

He would not work in the fields anymore.

In exchange, Moses would do exactly what Cornelius told him to do.

Moses asked what the master wanted him to do.

Cornelius smiled.

It was not a kind smile.

He wanted Moses to speak with the dead.

Within 2 weeks, word had spread throughout Edgefield County that Cornelius Whitmore had acquired something remarkable.

A young enslaved boy who could communicate with spirits, a genuine medium, a direct line to the other side.

Cornelius was careful about how he presented this information.

He did not take out advertisements in newspapers.

He did not hire a promoter.

Instead, he let the story spread through the social networks of the southern aristocracy.

A word dropped at a dinner party here.

A hint given during a business meeting there.

By the first week of September, the requests were flooding in.

Mrs.

Carolyn Ashford of Barnwwell County had lost her husband to fever the previous spring.

She was desperate to know if he had forgiven her for their final argument.

She offered $50 for a private session with the boy.

Judge Harrison Pul of Aken County had a son who had died in a hunting accident three years earlier.

He would pay $100 to speak with him one more time.

The Patterson family of Augusta, Georgia, had lost their entire fortune in a bank collapse.

Their patriarch had died before revealing where he had hidden his emergency funds.

They would pay $500 for any information the boy could provide.

Cornelius Whitmore accepted them all.

The first official seance was held on September 15th, 1851.

The client was Mrs.

Caroline Ashford.

She arrived at the Witmore plantation in a black carriage dressed in morning clothes, clutching a handkerchief in her trembling hands.

Cornelius escorted her to a small parlor on the second floor of the main house.

The room had been prepared according to Cornelius’s specifications.

Heavy curtains blocked out the afternoon sun.

Candles provided the only illumination.

A round table sat in the center of the room with three chairs arranged around it.

Moses was already seated at the table when Mrs.

Ashford entered.

She paused when she saw him.

Whatever she had been expecting, it was not this.

Not a child, not a young black boy in plain clothes, looking at her with eyes that seemed far too old for his face.

Mrs.

Ashford took her seat across from Moses.

Cornelius sat in the third chair, ready to observe and intervene if necessary.

What happened next would be talked about in Edgefield County for years.

Moses closed his eyes.

The candles flickered, though there was no breeze in the room.

The temperature seemed to drop several degrees.

When Moses opened his eyes again, Mrs.

Ashford gasped.

She would later tell friends that the boy’s eyes had changed.

They were the same brown color, but there was something different in them, something that was not the boy anymore.

Moses spoke, but the voice that came from his mouth was not his own.

It was deeper, rougher, the voice of a man who had spent years smoking cigars and drinking whiskey.

The voice said Caroline’s name.

Mrs.

Ashford began to cry.

The voice said that there was nothing to forgive.

The argument did not matter.

It had never mattered.

All that mattered was that they had loved each other for 23 years.

All that mattered was that she had been by his side when he died.

All that mattered was that she would see him again someday.

The voice said that William was at peace.

He wanted Caroline to be at peace, too.

Mrs.

Ashford sobbed uncontrollably.

She asked question after question.

Where had William hidden the deed to the Charleston property? What should she do about their son’s gambling debts? Did William know that she visited his grave every Sunday? The voice answered every question.

It knew details that no stranger could have known.

It referenced private conversations.

It mentioned incidents that had happened years ago.

It spoke with the intimate knowledge of a husband addressing his wife.

After about 30 minutes, Moses shuddered and slumped forward in his chair.

When he looked up, his eyes were his own again.

The voice was gone.

Mrs.

Ashford stared at him for a long moment.

Then she stood, walked around the table and knelt beside the boy’s chair.

She took his small hands in hers.

She thanked him.

She told him that he had given her the greatest gift she had ever received.

She told him that she would never forget what he had done for her.

Then she stood, composed herself, and walked downstairs to pay Cornelius Whitmore his $50.

The seances continued through September and October.

Word spread.

More clients arrived.

The prices went up.

By the end of October, Cornelius was charging $200 per session, and he still had a waiting list that stretched into the following year.

Moses performed these sessions three or four times a week.

Each time he closed his eyes and allowed the dead to speak through him.

Each time he channeled voices that knew things no living person could know.

Each time he left his wealthy white clients weeping with grief and gratitude.

But something else was happening too.

Something that Cornelius Whitmore did not notice because he was too busy counting his money.

Moses was changing.

Each time he opened himself to the spirits, he took a little bit of them into himself.

Each time he channeled a voice from the other side, he absorbed some of their memories, their emotions, their unfinished business.

And not all of the spirits who came to Moses were the loved ones of wealthy white clients.

At night, after the seances were over and the clients had gone home, other spirits came to Moses in his small room in the servants’s wing.

These were not the spirits of plantation owners and merchants.

These were the spirits of the enslaved, the forgotten, the murdered.

They had been waiting decades for someone to hear them.

And now, finally, they had found their voice.

An old man named Solomon came to Moses almost every night.

Solomon had been worked to death on this very plantation in 1819.

He had collapsed in the cotton fields during harvest season, and the overseer had refused to let anyone stop working to help him.

He had lain there in the dirt, dying slowly, while the people he loved were forced to step over his body and keep picking cotton.

A young woman named Pearl appeared to Moses during thunderstorms.

She had drowned herself in the creek behind the tobacco barn in 1836.

She had been 16 years old.

The master’s son had attacked her, and she could not live with what had happened.

She had walked into the water on a Sunday morning while everyone else was in the prayer meeting.

A child named Benjamin sat at the foot of Moses’s bed every night watching him sleep.

Benjamin had been sold away from his mother at age four.

He had died of fever on a plantation in Louisiana, alone and afraid, calling out for a mother he would never see again.

There were dozens of them, hundreds of them, spirits stretching back 60 years.

All the enslaved people who had lived and suffered and died on Witmore land.

All the souls that the white families had used and discarded and forgotten.

They told Moses their stories.

They showed him their deaths.

They shared with him the injustices they had endured.

And they asked him for something in return.

They asked him for justice.

Moses listened.

He absorbed.

He remembered.

And slowly, in the deep quiet of his small room, he began to understand what he had to do.

The dead had been patient.

They had waited years, decades, generations for this moment.

They had watched as their murderers grew old and prosperous.

They had watched as their children and grandchildren were sold and scattered and forgotten.

They had watched as the white families who had destroyed them built mansions and threw parties and pretended that everything was fine.

Now finally they had found their instrument.

Moses was going to give them their revenge.

But first he needed to wait.

He needed to be patient just as they had been patient.

He needed to build trust with Cornelius Witmore.

He needed to meet more of the wealthy white families in the region.

He needed to learn their secrets.

He needed to understand exactly who had done what to whom.

Because when the time came, Moses did not want to make any mistakes.

When the time came, every guilty soul was going to pay.

By November of 1851, Moses Grant had become the most talked about phenomenon in the South Carolina low country.

Stories about the boy who spoke to the dead had spread far beyond Edgefield County.

Wealthy families from Georgia, North Carolina, and even Virginia were writing letters to Cornelius Whitmore, begging for appointments.

Some offered extraordinary sums.

One plantation owner from Savannah offered to trade five prime field hands for a single private session.

Cornelius Whitmore had never been happier.

In just three months, Moses had generated more income than an entire cotton harvest.

And unlike cotton, Moses required no planting, no fertilizer, no army of workers to bring in the crop.

All Cornelius had to do was schedule the appointments and collect the money.

But Cornelius made a critical mistake.

He saw Moses as a tool, a piece of property that happened to have a remarkable ability.

He never stopped to consider that Moses might have his own plans.

He never imagined that the quiet, obedient boy sitting across from wealthy white clients might be gathering information, storing it away, waiting.

Cornelius Whitmore did not understand what he had brought into his house.

The seances continued through November.

Moses met with more than 40 clients during that month alone.

He channeled the spirits of dead husbands and wives, dead children and parents, dead business partners and old friends.

He answered questions about hidden money and secret affairs.

He delivered messages of love and forgiveness.

And every single session taught him something new.

Moses learned that Judge Harrison Poke had beaten an enslaved man to death in 1844 for looking at his daughter.

The judge had buried the body himself in the woods behind his property and never spoke of it again.

Moses learned that the Patterson family of Augugusta had made their original fortune by stealing land from a free black family in 1823.

They had forged documents, bribed officials, and driven the family off their property at gunpoint.

The patriarch had later sold three members of that same family into slavery in Mississippi.

Moses learned that Mrs.

Caroline Ashford’s beloved husband, the one she missed so desperately, had fathered seven children with enslaved women on his plantation.

He had sold every single one of those children before they reached the age of 10.

He had never told his wife.

She had never asked.

The dead told Moses everything.

The spirits of the enslaved people who had witnessed these crimes came to him night after night sharing their testimony.

They had seen what the white families did behind closed doors.

They had watched the murders and the rapes and the thefts.

They had been powerless to stop any of it.

They had died with these secrets locked inside them.

Now finally they could speak.

Moses kept it all inside.

He filed away every piece of information, every name, every date, every location.

He was building something, a record of crimes that stretched back decades, a catalog of horrors that the wealthy white families of the region had committed and forgotten.

He was building a weapon.

December came and with it the social season.

The plantation families held parties and balls and dinners.

They visited each other’s estates.

They showed off their wealth and their status.

And increasingly they talked about the remarkable boy at the Whitmore plantation.

Cornelius basked in the attention.

He had become famous by association.

Other plantation owners treated him with new respect.

They wanted to know his secret.

They wanted to know how he had found such a valuable piece of property.

Cornelius told them it was simply good fortune, divine providence.

He had been blessed with a boy who could speak to the dead, and he was generous enough to share this blessing with his friends and neighbors, for a price, of course.

The most significant event of the social season was the annual Christmas gathering at the Harrington plantation.

The Harringtons were one of the oldest and wealthiest families in Edgefield County.

They had been among the first English settlers in the region, arriving in 1732.

Over the generations, they had accumulated more than 10,000 acres of prime farmland and nearly 500 enslaved people.

The current patriarch was a man named Edmund Harrington.

He was 63 years old and he controlled more wealth than any other individual in the county.

His word was law in Edgefield society.

His approval could make a family’s reputation.

His disapproval could destroy it.

Edmund Harrington had been skeptical of the stories about Moses Grant.

He was a practical man, not given to superstition or religious enthusiasm.

He had dismissed the spiritualism craze as northern foolishness, unsuitable for sensible southern gentlemen.

But his wife Margareta was a different story.

Margaretta Harrington was 58 years old and deeply religious.

She attended church every Sunday without fail.

She read the Bible each morning before breakfast, and she had never recovered from the death of her sister Ruth, who had passed away 15 years earlier under mysterious circumstances.

Ruth had been visiting the Harrington plantation in the summer of 1836 when she suddenly fell ill.

The doctors said it was a fever.

She died within a week.

Margaretta had been devastated.

She and Ruth had been inseparable since childhood.

Losing her was like losing a part of herself.

For 15 years, Margareta had prayed for some sign that Ruth was at peace, some indication that her sister was watching over her from heaven, some comfort in her grief.

When she heard about the boy who could speak to the dead, Margaretta knew she had to meet him.

She begged her husband to invite the Wit Moors to their Christmas gathering.

She begged him to arrange a private session with the boy.

Edmund resisted at first, but he loved his wife and he could deny her nothing.

He sent a letter to Cornelius Witmore.

The invitation arrived at the Witmore plantation on December 15th.

Cornelius was thrilled.

An invitation to the Harrington Christmas gathering was a mark of the highest social distinction.

It meant that he had truly arrived.

It meant that the Witmore family was now considered part of the county’s elite.

The fact that the invitation came with a request for Moses to perform a seance only made it better.

Edmund Harrington was offering $500 for a private session.

$500 more than Cornelius had ever charged before.

Cornelius accepted immediately.

Moses learned about the upcoming seance on December 16th.

Cornelius called him into the study and explained the situation.

In one week, they would travel to the Harrington plantation.

Moses would perform for the most important family in the county.

This was his chance to prove himself.

This was his chance to make Cornelius proud.

Moses nodded and said, “Yes, sir, the way he always did.

” But inside, something was shifting.

Moses had heard the name Harrington before.

He had heard it from the spirits who visited him at night.

The dead had told him things about the Harrington family.

Terrible things.

Moses had been waiting for an opportunity.

Now, finally, it had arrived.

The Witmore family arrived at the Harrington plantation on December 22nd, 1851.

The estate was even larger and more impressive than the Witmore property.

The main house was a massive Greek revival mansion with 12 white columns across the front.

Enslaved servants in matching uniforms waited on the steps to greet arriving guests.

Moses was brought in through the back entrance as was appropriate for an enslaved person.

He was taken to a small room in the servants quarters where he would wait until he was needed.

The Christmas gathering was scheduled to last 3 days.

There would be dinners and dances and hunting parties.

The seance was scheduled for the evening of December 23rd.

After dinner, Margaretta Harrington had requested a private session with only herself, her husband, and Cornelius Witmore present.

Moses spent the day of December 23rd in his small room, waiting.

But he was not alone.

The spirits of the Harrington plantation had found him the moment he arrived.

They had been waiting for someone like him for a very long time.

They told him everything.

They told him about the enslaved woman named Ruth who had worked in the main house kitchen.

Not Margaretta’s sister Ruth, a different Ruth.

A black woman who had been purchased by the Harrington family in 1834.

This Ruth had been beautiful, 20 years old when she arrived at the plantation.

Tall and graceful with high cheekbones and deep brown eyes.

She had attracted the attention of Edmund Harrington from the very first day.

Edmund Harrington had forced himself on Ruth repeatedly over the next two years.

His wife Margaretta knew nothing.

Or perhaps she chose to know nothing.

Either way, Ruth suffered in silence as enslaved women were expected to do.

In the summer of 1836, Ruth discovered she was pregnant.

She tried to hide it.

She wore loose clothing.

She worked harder than ever, hoping that no one would notice.

But eventually, her condition became obvious.

Edmund Harrington was furious.

A pregnant enslaved woman was a complication he did not need.

If the child looked too much like him, questions would be asked.

His reputation would be damaged.

His marriage might be destroyed.

He decided to solve the problem permanently.

On a July night in 1836, Edmund Harrington went to Ruth’s cabin.

He told her to come with him.

He led her to the creek behind the tobacco barn, and there, in the darkness, he held her head underwater until she stopped struggling.

He buried her body in a shallow grave nearby.

He told the other enslaved people that Ruth had run away.

He posted notices in the neighboring counties, offering a reward for her capture.

He played the part of the agrieved property owner.

No one ever found Ruth.

No one ever knew what had happened to her until now.

The spirits told Moses one more thing.

Something that made his blood run cold.

Margaretta Harrington’s sister, the white woman named Ruth, had arrived at the plantation just 3 days after the enslaved Ruth disappeared.

She had been suspicious.

She had asked questions.

She had found the fresh grave by the creek.

She had confronted her brother-in-law.

3 days later, the white Ruth was dead.

The doctors called it a fever.

But the spirits knew better.

They had watched Edmund Harrington slip something into her evening tea.

They had watched her convulse and vomit and die over the course of seven agonizing days.

Edmund Harrington had killed two women named Ruth, one black, one white, both murdered to protect his secrets, both buried and forgotten.

Moses sat in his small room and absorbed this information.

He felt the weight of it settle into his bones.

Two innocent women murdered by the same man.

And that man was sitting in the main house right now, laughing and drinking wine and celebrating Christmas with his wealthy friends.

Moses made a decision.

Tonight during the seance, Edmund Harrington was going to pay for what he had done.

The seance began at 9:00 in the evening.

Moses was brought to a private parlor on the second floor of the main house.

The room had been prepared according to Cornelius’s usual specifications.

Heavy curtains, dim candle light, a round table with chairs.

Margareta Harrington was already seated when Moses entered.

Her face was pale with anticipation.

Her hands trembled slightly.

She had been waiting 15 years for this moment.

Edmund Harrington sat beside his wife.

His expression was skeptical, almost amused.

He clearly did not believe any of this was real.

He was humoring his wife.

Nothing more.

Cornelius Whitmore took the third chair.

He nodded at Moses to begin.

Moses sat down across from the Harringtons.

He looked at Margaretta’s hopeful face.

He looked at Edmund’s smug expression.

He thought about the two women buried in shallow graves.

He thought about the baby who had never been born.

He closed his eyes.

The room grew cold.

The candles flickered.

Margaretta gasped.

When Moses opened his eyes again, they were different, darker, older, filled with something that made Edmund Harrington’s smug expression falter for the first time.

Moses spoke, but the voice was not his own.

It was a woman’s voice.

Soft, southern, cultured.

The voice of Margaretta’s sister.

The voice said Margaretta’s name.

Margaretta burst into tears.

She reached across the table, grasping at nothing, trying to touch the spirit of her beloved sister.

The voice continued.

It said that it had missed Margaretta terribly.

It said that it had been watching over her all these years.

It said that it loved her and always would.

Margaretta sobbed with joy.

This was everything she had hoped for.

This was proof that Ruth was at peace.

This was the comfort she had been seeking for 15 years.

Then the voice changed.

It became harder, angrier.

The soft southern accent sharpened into something fierce.

The voice said that there was something Margareta needed to know, something she had never been told, something that had been hidden from her for 15 years.

The voice said that she had not died of fever.

Margaretta’s sobb stopped abruptly.

She stared at Moses with wide, confused eyes.

The voice continued.

It said that she had been murdered, poisoned by someone in this very room.

Edmund Harrington stood up so fast that his chair crashed backward onto the floor.

He shouted at Cornelius.

He demanded that this spectacle be stopped immediately.

He said the boy was lying.

He said this was all a fraud, a trick, a manipulation.

But Moses kept speaking.

The voice kept coming.

And now it was not just one voice anymore.

Another voice joined in.

A different voice.

Lower, rougher.

The voice of a black woman who had grown up in the cotton fields.

This voice said her name was Ruth, too.

This voice said she had worked in this very house.

She had cooked meals in the kitchen downstairs.

She had served Edmund Harrington his breakfast every morning for 2 years.

This voice said Edmund Harrington had attacked her again and again for months in the pantry, in the cellar, in the dark corners of the house where no one could see.

This voice said she had become pregnant.

And when Edmund found out, he took her to the creek behind the tobacco barn.

He held her underwater.

He felt her struggle and go still.

He buried her body where no one would find it.

Margareta Harrington turned to look at her husband.

Her face was no longer hopeful.

It was horrified, shattered.

The face of a woman whose entire world was crumbling around her.

Edmund Harrington was backing toward the door.

His face had gone white.

Sweat poured down his forehead.

His hands were shaking uncontrollably.

He shouted that the boy was lying.

He shouted that this was witchcraft, devil’s work, something evil that needed to be destroyed.

Moses stood up from his chair.

The two voices continued to speak through him, overlapping, blending together, black and white, enslaved and free.

Two women murdered by the same man.

The voices described exactly how Ruth, the enslaved woman, had died.

They described the feeling of hands pushing her head underwater.

They described the burning in her lungs as she struggled for air.

They described the moment when everything went dark.

The voices described exactly how Ruth, the white woman, had died.

They described the bitter taste of the poison in her tea.

They described the seven days of agony that followed.

They described the moment when she realized her own brother-in-law had murdered her.

Edmund Harrington screamed.

He lunged toward Moses.

His hands reaching for the boy’s throat.

But before he could take two steps, he stopped.

His body went rigid, his eyes bulged, his mouth opened in a silent scream.

He was staring at something behind Moses, something no one else in the room could see.

The spirits had come for Edmund Harrington, not just the two Ruths.

All of them.

every enslaved person who had suffered and died on Harrington land over the past hundred years.

Every soul who had been worked to death, beaten to death, sold away from their families, discarded like broken tools.

They had found their way to this room.

They had gathered around the man who represented everything they had endured, and they wanted him to see them.

Edmund Harrington fell to his knees.

He began to cry.

He began to beg.

He called out to God for mercy.

He called out to his mother for help.

He confessed everything.

Yes, he had killed Ruth.

Yes, he had killed both of them.

Yes, he had attacked enslaved women for years.

Yes, he had sold the children he had fathered into slavery in other states.

Yes, he had done terrible things.

He admitted it all.

Margareta Harrington stood frozen by the table, watching her husband’s complete breakdown.

Cornelius Whitmore had pressed himself against the wall, his face a mask of shock and fear.

Moses simply watched.

The spirits were not satisfied with confession.

They wanted more.

They wanted Edmund Harrington to feel what his victims had felt.

They wanted him to experience the terror and pain and helplessness that he had inflicted on so many others.

They began to show him.

Edmund Harrington screamed again.

This time the scream was different.

It was the scream of a man being torn apart from the inside.

The scream of a man whose mind was being flooded with a hundred years of suffering.

He collapsed onto the floor.

His body convulsed.

Foam appeared at the corners of his mouth.

His eyes rolled back until only the whites were visible.

After about 3 minutes, he stopped moving.

Edmund Harrington was dead.

The parlor was silent except for Margaretta’s ragged breathing.

She stood over her husband’s body, looking down at the man she had loved for 40 years, the man who had murdered her sister, the man who had attacked enslaved women.

the man who had hidden a lifetime of evil behind a facade of wealth and respectability.

She did not cry.

She did not scream.

She simply stood there processing the destruction of everything she had believed.

Cornelius Whitmore was the first to move.

He grabbed Moses by the arm and dragged him toward the door.

His face was pale with terror.

He had just witnessed something that defied all rational explanation.

A man had confessed to murder and then died right in front of him.

Apparently frightened to death by something invisible.

And Cornelius suddenly realized that the boy he had been using to make money might be something far more dangerous than he had ever imagined.

The next few hours were chaos.

The other guests at the Christmas gathering were awakened by the commotion.

Doctors were summoned.

The local sheriff was called.

Edmund Harrington’s body was examined.

and re-examined.

The official cause of death was listed as a sudden failure of the heart.

There was no evidence of foul play, no poison, no wounds.

The man had simply died.

But everyone who had been in that parlor knew the truth.

They had heard the voices.

They had seen Edmund Harrington’s confession.

They had watched something supernatural tear him apart.

And they knew exactly who was responsible.

Cornelius Whitmore left the Harrington plantation that same night, dragging Moses with him.

He did not speak during the entire journey home.

His mind was racing, trying to process what had happened.

On one hand, Edmund Harrington had been a murderer, a rapist, a man who deserved whatever punishment he received.

On the other hand, Moses had just killed one of the most powerful men in South Carolina.

Not with a weapon, not with poison, with something far worse, with the voices of the dead.

If word got out about what had really happened in that parlor, there would be consequences.

The white families of the region would not tolerate an enslaved boy who could expose their secrets and strike them dead.

They would demand that Moses be destroyed.

Cornelius had a choice to make.

He could try to protect his valuable property, or he could join the inevitable mob and save himself.

It did not take him long to decide.

By the morning of December 24th, 1851, messages had been sent to every major plantation in Edgefield County.

A secret meeting was called for that evening.

The topic was simple.

What to do about Moses Grant.

The meeting took place at the home of Judge Harrison Pul.

the same judge who had beaten an enslaved man to death years earlier.

More than 20 of the wealthiest men in the county attended.

They sat in the judge’s parlor drinking brandy and discussing the threat that had appeared in their midst.

The story of what had happened at the Harrington plantation had already spread.

Some details had been exaggerated, others had been suppressed, but the basic facts were clear.

A young enslaved boy had channeled the spirits of the dead.

Those spirits had accused Edmund Harrington of murder, and Edmund Harrington had died as a result.

Every man in that parlor had secrets.

Every man had done things that he would not want exposed.

Every man looked around the room and wondered who would be next.

They agreed unanimously that Moses Grant had to be eliminated.

The question was how.

They could not simply kill him outright.

There would be questions.

Cornelius Whitmore might object.

And there was the disturbing possibility that killing the boy might somehow make things worse.

What if his spirit became one of the vengeful dead? What if he came back even more powerful than before? They decided to approach the problem carefully.

They would take Moses from the Witmore plantation under cover of darkness.

They would transport him far from Edgefield County.

They would sell him to a brutal plantation in the deep south, somewhere he would be worked to death within a few years.

And if that did not work, if the boy proved difficult to transport or tried to use his powers to resist, they would burn him alive.

Fire, they reasoned, would destroy whatever dark magic the boy possessed.

The raid was scheduled for midnight on December 25th, Christmas night.

Moses knew they were coming.

The spirits had told him.

They had been watching the meeting at Judge Poke’s house.

They had heard every word.

They had carried the information back to Moses as he sat in his small room at the Witmore plantation.

For the first time since he had discovered his gift, Moses felt something like fear.

Not for himself.

He had made peace with the idea of death long ago.

Every enslaved person learned to make peace with death.

It was the only freedom they could count on.

No, Moses was afraid that he would fail.

He was afraid that the spirits would lose their voice just when they needed it most.

He was afraid that the wealthy white men would win again, as they always did.

And that all the secrets he had gathered would be buried with him.

He sat in the darkness of his room and waited.

The spirits gathered around him, more of them than he had ever seen before.

They filled the room.

They spilled out into the hallway.

They covered the grounds of the plantation like a silent army.

They had been waiting for this moment for generations.

They would not let it pass.

Christmas Day dawned cold and gray.

A light frost covered the cotton fields.

The enslaved people were given the day off, as was traditional.

They gathered in the quarters cooking special meals and singing songs and trying to forget for one day the brutal reality of their lives.

Moses did not join them.

He stayed in his room preparing.

He thought about his mother.

Abigail had been sent to work on a distant section of the plantation weeks ago, supposedly to help with the winter tasks.

But Moses knew the real reason.

Cornelius had wanted to separate them.

He had wanted to make sure that Abigail could not interfere with Moses’s performances.

Moses had not seen his mother in almost a month.

He wondered if he would ever see her again.

He thought about the years he had spent hiding his gift.

All the voices he had kept silent.

All the stories he had held inside.

He had been so careful, so obedient, so afraid.

He was not afraid anymore.

As darkness fell on Christmas night, Moses walked out of his room and into the cold December air.

He walked across the grounds of the main house.

He walked past the outuildings in the storage sheds.

He walked toward the quarters where the enslaved people lived.

The spirits walked with him.

By the time Moses reached the quarters, word had spread that something was happening.

The enslaved people emerged from their cabins, watching as the strange boy walked among them.

They saw something in his face that they had never seen before.

A calm certainty, a power that could not be denied.

Moses stopped in the center of the quarters.

He turned in a slow circle, looking at the faces around him.

These were his people, his family.

They had suffered alongside him.

They had survived alongside him.

They deserved to know the truth.

He began to speak.

He told them about the spirits.

He told them about the voices he had heard since childhood.

He told them about the dead who had come to him night after night, sharing their stories, begging to be remembered.

He told them about Jonas Caldwell and what had really happened the night he died.

He told them about Edmund Harrington and the two women named Ruth.

He told them about the secrets he had learned during the seances, the murders and rapes and thefts that the wealthy white families had committed.

He told them that the white men were coming tonight.

He told them that they planned to take him away and kill him.

And he told them that he was not going to run.

The enslaved people listened in shocked silence.

Some of them wept.

Some of them shook their heads in disbelief.

Some of them looked around nervously, afraid that the overseers might be listening.

But none of them left.

None of them walked away.

They stood with Moses in the cold December darkness, waiting to see what would happen next.

They did not have to wait long.

Just before midnight, the sound of hooves echoed across the plantation.

Torches appeared in the distance, moving toward the quarters.

The white men had arrived.

There were about 30 of them.

They rode in a tight formation, carrying rifles and ropes and torches.

Judge Harrison Pulk led the group.

Cornelius Whitmore rode beside him, his face tight with fear and shame.

They had expected to find Moses alone in his room.

They had expected to drag him out quietly while the other enslaved people slept.

They had expected no resistance.

Instead, they found the entire population of the quarters standing in the open, surrounding a small boy in the center.

Judge Pulk reigned in his horse.

He surveyed the scene with cold eyes.

He demanded that Moses Grant step forward immediately.

No one moved.

The judge repeated his demand.

He warned that anyone who interfered would be severely punished.

He said that this was not their concern.

He said that Moses had committed crimes against the white families of the region and had to face justice.

Still, no one moved.

The judge’s patience ran out.

He ordered his men to dismount and take the boy by force.

20 armed white men began walking toward the crowd of enslaved people.

They carried their rifles at the ready.

They expected the crowd to part.

They expected fear and submission.

The same fear and submission they had relied on for generations.

Moses stepped forward.

He walked through the crowd until he stood alone facing the approaching white men.

He was 11 years old.

He was small and thin and unarmed.

By every logical measure, he was utterly powerless.

But Moses Grant was not alone.

The air around him began to shimmer.

The temperature dropped so sharply that the white men’s breath turned to fog.

The torches they carried flickered and dimmed, their flames struggling against a cold that had nothing to do with the winter night.

And then the dead appeared.

They materialized out of the darkness one by one at first, then in groups, then in waves.

The spirits of every enslaved person who had died on Witmore land.

The spirits of those who had been murdered worked to death, sold away, broken.

They rose from the earth where their bones had been scattered.

They emerged from the shadows where their memories had been forgotten.

There were hundreds of them, men and women and children, old and young.

Some bore the marks of their deaths, the wounds and scars that had ended their lives.

Others appeared as they had been in moments of peace, strong and whole and unbroken.

They surrounded Moses like an army gathering around its general.

They faced the white men with eyes that burned with a hundred years of rage.

The white men stopped walking.

Judge Harrison Poke’s face went pale.

His hands began to shake.

He was staring at the ghost of the man he had beaten to death in 1844.

The man was looking back at him with an expression of infinite patience.

Cornelius Whitmore fell from his horse.

He scrambled backward in the dirt, screaming as the spirits of everyone who had died on his land moved toward him.

The other white men broke and ran.

They dropped their torches and rifles and fled into the darkness.

Their horses bolted, adding to the chaos.

Within minutes, the carefully organized raid had dissolved into pure terror.

Only Judge Pulk remained frozen in place, unable to look away from the ghost that stood before him.

Moses walked toward the judge.

The spirits parted to let him pass.

He stopped directly in front of Judge Poke’s horse and looked up at the man who had planned to kill him.

Moses spoke with his own voice, clear and calm and certain.

He told the judge that the dead were tired of waiting.

He told him that the secrets buried across this county were going to be revealed.

He told him that every murder, every rape, every cruelty that the white families had committed was going to be brought into the light.

He told the judge that he could run.

He could sell his plantation and flee to another state.

He could try to escape the past he had created.

But the dead would find him.

They would always find him because the dead had nothing but time.

Judge Harrison Poke looked into Moses’s eyes.

He saw something there that broke him.

He saw the faces of everyone he had ever harmed staring back at him with absolute clarity.

He turned his horse and fled into the night.

Moses watched him go.

Then he turned back to face his people.

The spirits were beginning to fade, their energy exhausted by the effort of manifestation.

But before they disappeared entirely, they did something that Moses had not expected.

They bowed to him.

One by one, the hundreds of spirits lowered their heads in a gesture of gratitude and respect.

They had waited so long for this night.

They had suffered so much.

And finally, through this small boy, they had been given their voice.

Then they were gone, and Moses was alone with the living.

The aftermath of that night changed everything.

Word of what had happened spread across South Carolina within days.

The story grew with each telling.

Some versions claimed that Moses had summoned demons from hell.

Others said he had called down the wroth of God himself, but all versions agreed on the essential facts.

The wealthy white men of Edgefield County had come to destroy a boy, and something had stopped them.

Judge Harrison Pulk was found dead in his study 3 days later.

The official cause was heart failure.

His face was frozen in an expression of terror.

Cornelius Whitmore sold the Witmore plantation within a month.

He moved to Texas and never returned to South Carolina.

He never spoke of Moses Grant again.

Several other families in the region quietly sold their properties and relocated.

They offered no explanations.

They simply left as if fleeing from something they could not name.

Moses Grant disappeared from the historical record after that Christmas night.

No documents show what happened to him.

No plantation ledgers list his name.

He simply vanished as so many enslaved people vanished in that era.

But the oral histories tell a different story.

According to the accounts passed down through generations of black families in the South Carolina low country, Moses Grant did not vanish.

He escaped.

He made his way north on the Underground Railroad, guided by the spirits of those who had traveled the route before him.

Some versions say he settled in Philadelphia where he lived as a free man until the Civil War.

Others say he continued north to Canada where slavery could not touch him.

Some versions say he continued to hear the voices of the dead throughout his life.

They say he used his gift to help other escaped slaves find their way to freedom.

They say the spirits guided him through dangerous territory, warned him of slave catchers, led him to safe houses where sympathetic people would hide him.

What is certain is that the events of December 1851 had a lasting impact on Edgefield County.

The wealthy white families never fully recovered their sense of invulnerability.

They had been confronted with something they could not control, could not buy, could not beat into submission.

They had been forced to face the accumulated weight of their crimes and they had learned that the dead do not forget.

The story of Moses Grant survived because the people who witnessed that Christmas night refused to let it die.

They passed it down to their children who passed it to their children who passed it to theirs.

It became a story of hope, a story of resistance, a story that proved that even the most powerless among us can find a way to strike back.

The lesson of Moses Grant is simple but profound.

You cannot bury the truth forever.

You cannot silence every voice.

You cannot escape the consequences of your actions.

No matter how much power you have or how many generations pass, the dead remember, and sooner or later they find a way to speak.

Moses Grant was born into chains in 1840.

He was considered property under the law, worth only what his labor could produce.

He had no rights, no legal standing, no protection of any kind.

But Moses Grant had something that his enslavers could never take from him.

He had a gift.

He had a connection to those who had come before.

He had the voices of the ancestors whispering in his ear, sharing their stories, demanding to be heard.

And when the moment came, Moses Grant used that gift to tear down the walls of silence that had protected evil for generations.

He was 11 years old.

He was enslaved.

He was just a child.

And he changed everything.

News

Ilhan Omar ‘PLANS TO FLEE’…. as FBI Questions $30 MILLION NET WORTH

So, while Bavino is cracking down in Minnesota, House Republicans turning the heat up on Ilhan Omar. They want to…

FBI & ICE Raid Walz & Mayor’s Properties In Minnesota LINKED To Somali Fentanyl Network

IC and the FBI move on Minnesota, touching the offices of Governor Tim Walls and the state’s biggest mayors as…

FBI RAIDS Massive LA Taxi Empire – You Won’t Believe What They Found Inside!

On a Tuesday morning, the dispatch radios in hundreds of Los Angeles taxi cabs suddenly stopped playing route assignments. Instead,…

Brandon Frugal Finally Revealed What Forced Production to Halt in Season 7 of Skinwalker Ranch….

The Secret of Skinwalker Ranch became History Channel’s biggest hit. Six successful seasons documenting the unknown with real science and…

1 MINUTE AGO: What FBI Found In Hulk Hogan’s Mansion Will Leave You Shocked….

The FBI didn’t plan to walk into a media firestorm, but the moment agents stepped into Hulk Hogan’s Clearwater mansion,…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage… It started like any other evening…

End of content

No more pages to load