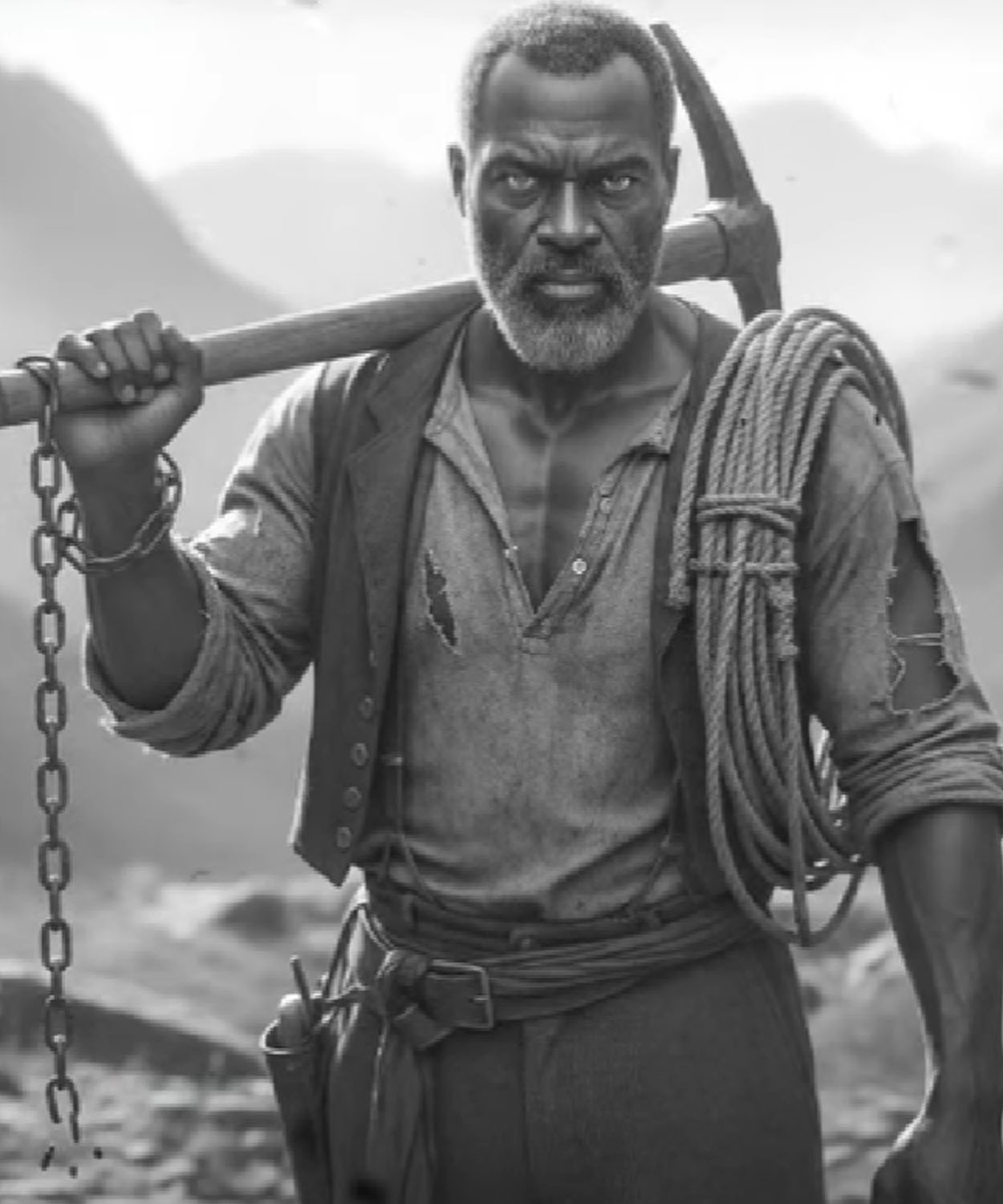

(1853) The Black Mountain Man Slave They Called “Beast” — Until His Invention Changed Everything

They called him beast, not because he had ever attacked anyone, but because they could not understand how a human body could survive what his did.

He was taller than most men, broader through the shoulders, with hands so large they made iron tools look small.

His back was a map of scars, old and new, crossing each other like roads that led nowhere.

And yet what unsettled the most was not his strength, but his silence.

Beast had no recorded name.

The ledger at the plantation listed him as property transferred to mountain labor, the place where men were sent when their presence made overseers uneasy.

Up there, beyond the neat rows of crops and the orderly cruelty of the fields, the rules were looser and harsher at the same time.

The mountains did not care about orders or whips.

They tested lungs, bones, and will.

Most men sent there lasted months, some weeks.

A few days in winter, beast endured.

He had been brought to the mountains in chains after an incident no one ever described clearly.

Some said an overseer had struck him once too often and felt something in the man’s gaze that made his hand shake.

Others whispered that beast had lifted a wagon alone, not to help, but simply because he had calculated that it would save time.

Efficiency unsettled them.

Thought unsettled them.

Strength guided by intelligence frightened them most of all.

So they sent him away.

They built him a crude shelter of logs and stone far from the main camp, close enough that he could be watched, far enough that no one had to feel his presence too closely.

He was given the hardest tasks, hauling broken timbers down near vertical slopes, clearing rockfalls after storms, dragging dead mules out of ravines.

When winter came, they left him with a thin blanket and told him the cold would tame him.

It did not.

The mountain stripped him down to essentials.

Hunger became a constant companion, dull and sharp at the same time.

Cold gnored at his bones at night, teaching him how to read the wind, how to build fires that burned low and long, how to place stones so they held warmth instead of stealing it.

When tools broke, no replacements came quickly.

Beast learned to improvise, to repair, to reshape what little he had.

He learned how wood bent before it snapped, how iron failed, how stone shifted under pressure.

The whites mistook his silence for emptiness.

In truth, his mind was always working.

He watched how rain carved paths down the mountain, how water found the weakest point and widened it slowly, patiently until rock gave way.

He watched landslides bury roads that men had sworn were permanent.

He watched tunnels collapse in mines where white engineers argued loudly and listened poorly.

Every failure etched itself into his memory.

At night, when the camp slept, beast would sit near the fire and sketch shapes in the dirt with a stick, levers, slopes, ways to move weight without breaking bodies.

He erased them before dawn, not out of fear of discovery, but because he knew they were unfinished.

The mountain demanded precision.

The overseers came rarely, and when they did, they treated him like an unpredictable animal.

They spoke loudly, slowly, hands never far from weapons.

Beast answered only when necessary.

Not because he could not speak, but because he understood something they did not.

Words were wasted on those who never listened.

One spring, after weeks of heavy rain, the main supply route collapsed.

A massive rock slide buried wagons, animals, and men beneath tons of stone and mud.

The plantation owners panicked.

Without that route, goods could not move.

Mines would close.

Money would stop flowing.

White engineers were brought in.

Men with clean boots and rolled up maps.

They argued, measured, cursed the mountain and failed.

Beast was ordered to clear Bodhi s and debris.

As he worked, dragging shattered timbers and broken flesh from the slope, he saw the problem immediately.

The mountain was not angry.

It was unbalanced.

The road had been cut wrong.

The weight distributed foolishly.

Men had forced their way through instead of working with the land.

Beast felt something shift inside him.

Not rage, but clarity.

That night he returned to his shelter and began again sketching in the dirt.

This time the shapes stayed longer.

He stacked stones to test pressure.

He tied ropes in new ways.

He used his own weight to test angles.

The mountain answered him slowly, honestly.

Over the following days, something strange happened.

Without being told, Beast began to place debris differently.

He wedged fallen logs, not as waste, but as supports.

He redirected runoff with shallow channels.

He moved less, but accomplished more.

Overseers noticed only that progress was faster and it unsettled them.

One engineer scoffed when Beast gestured toward a section of the slope, indicating it would fail again if left untouched.

The man laughed and told him to keep hauling.

3 days later, that exact section collapsed, narrowly missing the engineer himself.

For the first time, someone looked at Beast not with contempt, but with uncertainty.

Still, no one asked him how he knew.

They could not reconcile the idea of a slave understanding what their educated men did not.

To do so would require admitting something dangerous, that the man they had named Beast was thinking, observing, solving, so they kept him isolated, and Beast in turn kept learning.

Each night he refined his ideas.

Not an invention yet, not fully formed, but something emerging from necessity.

a way to move earth without breaking backs.

A way to stabilize slopes using the mountains own strength.

He did not think of freedom in those days.

Freedom was too abstract, too far away.

What he thought about was balance, pressure.

How systems failed when they relied on force alone.

Winter returned harsher than before.

Snow trapped the camp for weeks.

Food ran low.

Men froze.

Beast survived by applying what he had learned, building structures that trapped heat, rationing energy, moving only when necessary.

When the overseers finally reached his shelter, expecting to find a corpse, they found him alive, calm, waiting.

Fear changed shape.

Then they still called him beast.

But now the word carried something else.

Respect, twisted, and unspoken.

He was no longer just something to be controlled.

He was a problem they did not understand how to solve.

And in the quiet moments, when the mountain wind howled and the world seemed reduced to stone and sky, beast allowed himself one thought he rarely entertained.

If he could change how men fought the mountain, perhaps one day he could change how men thought about him.

The mountain had not broken him.

It had taught him, and what it taught him would soon change everything.

The name beast no longer sounded like an insult when the whites spoke it.

It sounded like a warning.

No one could quite remember who had said it first.

Names like his often appeared without ceremony, passed from mouth to mouth, shaped by fear more than truth.

But once it took hold, it followed him everywhere, echoing between trees and ridge lines.

Beast, not a man, not someone to reason with, something to be managed, contained, kept apart.

They said he did not feel pain the way other men did.

That rumor began after a winter punishment meant to break him.

An overseer, frustrated by beast’s refusal to move faster on a frozen slope, ordered him stripped to the waist and tied to a post overnight.

The temperature fell hard after sunset.

Other slaves watched from a distance, already mourning him in their hearts.

Men had died that way before.

Strong men, loud men, men who had begged.

Beast did neither.

When morning came, frost coated his skin like pale ash.

His lips were cracked, his hands stiff, but he was alive.

More than that, he was standing.

When they cut him loose, he did not collapse.

He simply bent, picked up his tools, and walked back toward the slope.

Something shifted that day.

The overseers did not celebrate his survival.

They grew uneasy.

Pain was supposed to teach obedience.

Fear was supposed to produce submission.

But beast absorbed suffering the way the mountain absorbed storms without complaint, without visible change, storing something beneath the surface.

They began watching him more closely.

Beast noticed everything.

He noticed how men avoided standing directly behind him.

how whips were held tighter, used less often.

How commands became shorter, more careful, as if language itself might provoke him.

He did not exploit this.

He did not threaten.

He simply continued working, observing, learning.

He understood fear better than they did.

Fear, he had learned, did not always come from violence.

Sometimes it came from endurance.

From a man who did not react the way he was supposed to, from silence where screaming should be, the mountain labor intensified.

Landslides were more frequent now, and with them came injuries and deaths.

White supervisors blamed weather, bad luck, God, anything but their own decisions.

Beast saw patterns instead.

He saw that men cut where they should have curved, dug where they should have supported, rushed where patience was required.

One afternoon, a young white overseer tried to assert authority by pushing Beast toward a collapsing trench.

Beast stopped walking.

He did not raise his hands.

He did not clench his fists.

He simply stopped.

The overseer shoved him again, shouting.

Beast turned slowly, looked at the trench, then at the man, then back at the trench.

He shook his head once.

“No,” he said quietly.

The words stunned them more than if he had shouted.

The overseer’s face flushed with rage.

He raised his whip, and then the trench collapsed exactly where Beast had been standing moments before, burying tools and earth in a violent rush.

Silence followed.

Dust hung in the air.

No one spoke.

The overseer lowered his arm.

He did not apologize.

He did not thank Beast, but he stepped back.

From that day on, orders around Beast became suggestions wrapped in authority.

The whites began telling stories about him when they thought he could not hear.

They said he had killed a man once and been spared only because it took six men to restrain him.

They said bullets bounced off his back.

They said he ate raw meat and slept in the snow.

None of it was true.

But fear does not need truth.

It only needs repetition.

Beast understood this too.

He did nothing to correct them.

Other slaves began to treat him differently as well.

Some avoided him, frightened by the rumors.

Others sought him out quietly, watching how he worked, how he conserved strength, how he survived winters that killed stronger men.

He did not teach openly.

Teaching drew attention.

But when he adjusted a tool or repositioned a load, others noticed.

Knowledge spread without words.

The mountain was reshaping him.

Not into a weapon, but into a problem no one knew how to solve.

One evening, after a long day hauling stone, a white engineer approached him alone.

This man was older, quieter than the rest.

He had seen enough failures to know arrogance was useless.

“How do you know where it’ll fall?” the man asked, gesturing toward a slope Beast had avoided.

Beast considered him for a moment.

Then he picked up a stone, placed it on the ground, and pushed it gently.

It rolled, stopped, then shifted again when the earth beneath it gave way.

Pressure, be said, always tells.

The engineer stared at him, unsettled not by the answer, but by how simple it was.

After that, the engineer began watching Beast instead of arguing with other whites.

He never admitted it openly, but he started copying what Beast did, where he placed supports, how he angled paths.

When he stopped work altogether, things improved.

Slowly, other whites noticed.

Whispers began.

The beast knew something, something useful that frightened them more than his strength ever had.

A strong slave could be broken, killed, or sold.

A thinking slave, one whose ideas saved money and lives, was dangerous in a different way.

You could not whip knowledge out of a man once it had proven itself.

They tightened their control in subtle ways.

More guards, fewer supplies, less rest.

They worked Beast harder than anyone else, trying to drain him to keep him too exhausted to think.

They underestimated him again.

Beast had learned long ago how to ration himself.

He used his strength only when necessary.

He let others believe he was tiring when he was not.

At night, while muscles screamed and bones achd, his mind stayed awake.

He began to see the mountain not as an enemy, but as a system.

Forces acting on forces, weight balanced against support, movement guided instead of resisted.

What men called accidents were simply consequences of ignorance.

In the dirt outside his shelter, the sketches grew more complex.

Not just levers and slopes now, but systems.

Ways for fewer men to move more earth.

Ways to let gravity work instead of fighting it.

The beginnings of something dangerous.

The whites still called him beast.

But now when they said it, there was hesitation.

They feared him not because he lashed out, but because he endured, observed, adapted, because pain did not make him smaller.

Because the mountain which crushed men without mercy had not crushed him, it had educated him, and somewhere between fear and necessity, the whites began to rely on the very man they had tried to erase.

They did not yet understand what that reliance would cost them.

But beast did.

The mountains themselves had become a liability no one could ignore.

What had once been dismissed as bad terrain was now openly called a crisis.

Supply routes failed one after another.

Bridges washed out.

Roads carved too sharply into slopes collapsed without warning.

Mines flooded or caved in.

Burying tools ore and men.

Each failure cost money, and money was the only language the plantation owners truly respected.

They sent for more engineers.

Men arrived with papers, measurements, and confidence sharpened by distance from the actual mountain.

They talked loudly, argued constantly, and blamed everyone but themselves.

They sketched straight lines where the land curved and demanded obedience from stone that had never obeyed anyone.

Beast watched.

He watched how they argued over theories while ignoring the ground beneath their feet.

He watched how they overbuilt where lightness was needed and under supported where pressure gathered.

He watched how they shouted orders while the mountain quietly prepared its reply.

He said nothing.

That silence was mistaken for ignorance.

One major project consumed them that summer.

A new supply corridor cut across a narrow ridge meant to save time and money.

The whites insisted it would hold.

Beast knew it would not.

The ridge was hollowed by water beneath the surface.

Its strength and illusion.

He felt it under his boots.

He heard it when the wind passed through unseen gaps.

He tried once.

He placed stones where supports should be, subtly redirecting runoff, slowing erosion.

An overseer noticed and kicked his work apart, shouting that Beast was not paid to think.

So Beast stopped interfering.

He returned to hauling, clearing, obeying.

He let them build exactly as they wished.

The collapse came 3 weeks later.

It happened in the early morning when the ridge was heavy with fog and moisture.

The ground shuddered once, like a deep breath being taken, and then the earth gave way.

Wagons vanished.

Men screamed.

The corridor folded inward, swallowing months of labor in seconds.

When it was over, the mountain stood unchanged.

Only human effort had disappeared.

Panic followed.

The loss was too large to ignore, too public to hide.

Plantation owners arrived in person.

Boots sinking into mud.

Tempers flaring.

G.

Someone had to be blamed.

Engineers blamed labor.

Overseers blamed weather.

Weather has always said nothing.

And then someone said Beast’s name, not as an accusation, but as a question.

They brought him to the edge of the collapse.

Chains still hung from his wrists, though looser now, more symbolic than necessary.

A white man with inkstained fingers asked him if he could see why it failed.

Beast studied the broken ridge quietly.

He crouched, pressed his palm to the soil, crumbled it between his fingers.

“Yes,” he said.

The word landed harder than the collapse itself.

How?” the man asked, unable to hide his urgency.

Beast looked at the slope, then at the twisted remains of wooden supports.

He gestured, not at one mistake, but at many, at angles cut wrong, at weight placed without balance, at drainage ignored.

His hands moved slowly, deliberately, mapping forces in the air.

The men listened in silence.

It was the first time any of them had listened to him.

They did not thank him.

They did not apologize.

But they did something more important.

They asked him what to do next.

That question marked a turning point.

Beast was assigned unofficially at first to walk projects before they began.

He was told to point, to nod, to shake his head.

When he shook it, men hesitated.

When he nodded, they proceeded.

His role was never written down.

It existed in the uneasy space between denial and necessity.

And slowly things began to change.

Roots held.

Supports lasted.

Landslides decreased.

Work that once killed men now merely exhausted them.

Money flowed again.

The whites did not call it his solution.

They called it luck or coincidence or improved management.

But they watched him constantly now.

Beast felt the shift.

He was still enslaved, still owned, still bound by chains.

But the nature of those chains had changed.

They were no longer just iron.

They were dependence, expectation, need.

He understood the danger immediately.

Dependence made him valuable.

Valuable things were protected, but also controlled more tightly.

Knowledge once revealed could be taken, copied, used without him.

So he began to hold something back.

He showed enough to keep projects standing, enough to keep them needing him, but not enough for them to understand why it worked.

He gave results without explanations, outcomes without theory.

At night his sketches became more elaborate, but also more secretive.

He erased them carefully.

He tested ideas alone, using his own body as measure, the mountain as judge.

The invention was forming, not as a single object yet, but as a system, a way to move weight using balance instead of brute force.

A way to let slopes support themselves.

a way to make fewer men do the work of many without breaking.

He had no name for it.

He only knew it worked.

The whites noticed something else, too.

Beast was no longer being sent only to clean up disasters.

He was being brought in before they happened.

That frightened them more than the disasters ever had.

A slave who predicted failure threatened the very idea of white superiority.

If they admitted he understood the land better than they did, what else might he understand? They responded the only way they knew how.

By tightening control while pretending to loosen it, Beast was given better rations, slightly better shelter, fewer public punishments.

In return, he was worked harder than ever.

Called at all hours, dragged from rest to inspect slopes by torch light.

His body bore the cost of their newfound reliance.

He endured it without complaint, but inside something hardened.

He saw now that solving their problems would never earn him freedom.

Only more problems, more responsibility, more exhaustion.

The mountain had taught him balance, but the whites refused to learn it.

So beast began planning not just solutions, but leverage.

If his knowledge was valuable, then control of that knowledge was power.

If the invention worked only when guided by his hands, his Jew DG meant his timing, then removing him would collapse the system.

He began shaping it that way intentionally, subtle changes, techniques that required intuition, adjustments that could not be written down, a system that looked simple from a distance but failed without understanding.

The whites praised the results while remaining blind to the design.

By the end of the third year, the mountain roots were more stable than they had ever been.

Profits recovered.

Confidence returned, and beast stood at the center of it all.

Still enslaved, still silent, still called beast, but now holding something far more dangerous than strength.

He held the solution to a problem they could not afford to lose.

And for the first time, he understood that the mountain had not just taught him how to survive.

It had taught him how power really worked.

What beast carried inside his mind could no longer be contained by sketches in dirt or quiet adjustments made in the shadows.

The idea had matured, hardened, taken shape the way stone does under pressure.

It was no longer just observation or instinct.

It was design.

The whites felt it before they understood it.

They felt it in the way projects that once took months now took weeks.

in how fewer men were needed to move heavier loads, in how accidents dropped, costs shrank, and the mountain, once an enemy, seemed to cooperate.

Something fundamental had shifted, and it unnerved them precisely because they could not name it.

Beast was summoned more often now, not with whips or shouting, but with messengers sent in haste, their voices edged with urgency.

“They need you,” they would say, as if the word need itself tasted strange in their mouths.

He was taken to a new site high along a narrow pass where wagons had never successfully crossed.

The owners wanted a permanent solution, something reliable, something that would endure weather and time.

Engineers stood around arguing, their boots clean, their hands unused to labor.

When Beast arrived, conversation stopped.

They watched him the way men watch a tool they do not fully understand.

Useful, necessary, and faintly threatening.

Beast walked the path slowly.

He did not rush.

He felt the slope beneath his feet, listened to the wind, watched how loose gravel shifted under weight.

He knelt, ran his fingers through soil, crushed it, smelled it.

To the whites, it looked primitive.

To him, it was measurement.

The problem was not strength.

It never had been.

The problem was that they were trying to force the mountain to behave like flat land.

Beast stood and gestured, not at where they wanted to build, but at where they should not.

He indicated a curve instead of a straight cut, a gradual descent instead of a steep one.

He pointed to where weight needed to be redirected, not resisted.

An engineer scoffed.

That’ll take twice the time.

Beast met his eyes calmly, or half the bodies.

Silence followed.

They gave him permission, not because they trusted him, but because they were afraid of failing again.

This time, Beast did not merely guide.

He built, he gathered scrap iron, broken chains, discarded timbers, and pieces of machinery that had failed in other projects.

He repurposed everything.

Nothing was wasted.

He arranged materials into a system that confused onlookers.

Ropes looped through pulleys at strange angles.

Wooden frames braced not vertically but diagonally.

Supports that seemed too light to hold anything.

Men whispered that it would collapse the moment weight touched it.

Beast worked without pause.

His massive frame moving with deliberate precision.

Every knot was intentional.

Every joint measured.

He tested components with his own weight.

Adjusted.

Tested again.

The mountain responded.

When they finally moved the first loaded wagon across the pass, it did not creek or strain the way previous attempts had.

The weight distributed itself smoothly, the system absorbed stress instead of fighting it.

The wagon crossed, then another, and not her.

What Beast had built was not just a structure.

It was a method, a way of using balance, leverage, and gravity together so that effort multiplied instead of diminished.

Men who once strained under loads now guided them.

Strength became secondary to placement.

Timing mattered more than force.

The whites were stunned.

They tried to understand it by naming parts, measuring angles, drawing diagrams.

They failed.

The system worked as a whole, not as isolated pieces.

Remove one element or change its placement and the balance failed.

Beast knew this.

He had designed it that way.

They began calling it an innovation, an advancement, something that would change mountain labor.

They said these things loudly, proudly, as if claiming the words might grant them ownership of the idea itself, but they never asked Beast what he called it.

He had no name for it.

Names implied possession.

This was not something that could be owned easily.

Soon the invention, if it could be called that, spread to other sites.

beast was taken from mountain to mountain, pass to pass.

Everywhere he went, the same thing happened.

Fewer deaths, faster progress, greater profit, and everywhere the same pattern followed.

The whites grew more dependent.

Chains were loosened further, not out of kindness, but necessity.

Guards kept their distance.

Overseers softened their voices.

Orders became requests.

Requests became expectations.

Beasts saw the contradiction clearly.

They still believed themselves superior, yet they could not function without him.

They still owned his body, yet his mind had become indispensable.

That imbalance unsettled them deeply.

They responded by tightening control in subtler ways.

He was watched constantly now.

Men followed him at a distance.

Engineers took notes obsessively.

They tried to replicate what he did when he was not present, always failing by small but critical margins.

Beast noticed the attempts and adjusted accordingly.

He introduced elements that relied on judgment rather than measurement, decisions that required feeling tension through rope, sensing vibration through wood, reading the mountains response in real time, things that could not be written down or taught without experience.

The invention began to take on a reputation of its own.

They said it only worked when Beast was there.

They said the mountain listened to him.

They said he had some unnatural understanding, something beyond reason.

Fear crept back in, reshaped.

The whites had wanted a solution.

They had not expected to create a dependency they could not control.

Beast felt the cost in his body.

He was worked harder than ever, summoned at all hours, expected to solve every problem instantly.

Sleep came in fragments.

Pain became constant.

His hands thickened with scars, his joints achd, his breath grew heavier in the thin mountain air.

Still he endured, but endurance alone was no longer enough.

At night, lying on the hard ground of his shelter, he thought not about freedom in the abstract, but about leverage, about systems, about what happened when a critical component was removed.

He understood now that his invention had changed the balance of power, but not yet enough.

As long as he remained physically present, they could keep extracting from him.

They would work him until the mountain finally claimed him, then try to strip his knowledge from what remained.

He could not allow that, so he began preparing for absence.

He subtly altered how the system functioned, making it increasingly reliant on decisions only he could make.

small adjustments, tiny calibrations, nothing obvious.

The whites noticed only that efficiency continued to improve when Beast was there.

When he was not, things began to slip.

A support placed just slightly wrong.

A pulley tensioned imperfectly.

Nothing catastrophic at first, just delays, minor failures, enough to remind them who truly held the knowledge.

They responded with frustration, then fear.

By the end of the fourth year, Beast was no longer just a slave laborer or even a problem solver.

He was a single point of failure in an entire regional system.

The invention born from chains had reshaped the mountains.

And the man they called beast understood something the whites still did not.

Once a system depends on you, disappearing becomes an act of power.

The mountain had taught him patience.

Now it was teaching him timing.

It was never spoken directly to him, never acknowledged out loud in any official way, but it lived in the pauses before orders were given, in the way overseers hesitated before raising their voices, in how engineers waited for his arrival before committing to decisions they once would have made loudly and wrong.

The mountain system he had built had become the backbone of the region’s labor, and without him, it faltered.

That truth terrified the whites more than anything else ever had.

They had always believed power came from ownership, from chains, from paper, from laws written by men who never lifted stone or felt earth shift beneath their feet.

But Beast had introduced another kind of power, one they could not easily seize or destroy.

He had made himself indispensable without ever demanding recognition.

Indispensable slaves were dangerous, so they tried to manage the danger the only way they knew how, by squeezing harder while pretending to reward.

Beasts rations improved again.

His shelter was reinforced against the cold.

He was no longer publicly whipped.

Instead, his punishment came in the form of endless work.

He was summoned to multiple sites in a single day, expected to solve problems instantly, dragged from one crisis to the next without rest.

When he slowed, they reminded him how much depended on him.

When he faltered, they spoke of replacing him, though they all knew they could not.

Beast understood the tactic clearly.

They were trying to extract everything from him before his body failed.

The mountain labor had changed shape around him.

Where once men strained under brute force, now they followed systems, his systems, guiding weight instead of carrying it, directing pressure instead of absorbing it.

Fewer men died.

More work was done.

Profits grew.

And yet the cruelty beneath it all remained.

Beasts saw it in how other slaves were still driven past exhaustion.

In how children were sent into narrow spaces too small for grown men, in how success only made the masters bolder, greedier, more demanding.

His invention had improved efficiency, but it had not improved mercy.

That realization sharpened something inside him.

He began watching the whites the way he watched the mountain, looking for stress points, weaknesses, patterns.

He noticed how engineers relied entirely on him now, how they deferred decisions, how they grew anxious when he was not immediately available.

He saw how overseers feared angering him, not because they respected him, but because delays cost money.

Fear had changed sides, but it was still fear.

One evening, after a long day stabilizing a failing ridge, Beast was ordered to move immediately to another site miles away.

His legs trembled from fatigue.

His hands shook as he tied knots.

He said nothing, but his body slowed despite his will.

An overseer snapped, raising his voice sharply.

Instinctively, men around them stiffened, waiting for the familiar crack of violence.

It did not come.

The overseer caught himself, lowered his voice, and repeated the order more carefully.

The silence afterward was thick.

Beast realized then that his presence had altered the behavior of those who believe themselves untouchable.

They still owned him, but they feared breaking what they depended on.

That fear was leverage.

At night, Beast no longer sketched just solutions.

He sketched absence.

He imagined what would happen if he were gone.

Not immediately.

He knew the system would limp along for a while, but slowly, inevitably, it would fail.

Small errors would compound.

Slopes woo.

LD weaken.

Supports would be misplaced.

Accidents would return.

He designed for that.

He made the system increasingly reliant on intuition, on subtle judgment calls only experience could provide.

He taught no one fully.

When asked questions, he answered in fragments.

never lies, but never the whole truth.

He let others believe they understood when they did not.

The whites, desperate to maintain control, began pressing him for explanations.

Engineers demanded drawings.

Overseers demanded instructions.

Owners wanted guarantees.

Beast gave them none.

He demonstrated instead.

demonstration required his presence, his hands, his timing, his judgment, and every successful demonstration reinforced the same truth.

Without him, the system was incomplete.

That frightened them deeply.

They discussed selling him, moving him, even killing him in moments of rage.

But every conversation ended the same way.

They could not afford to lose him.

The mountain roots, the mines, the supply lines, all depended on what he carried in his mind.

So they kept him and worked him harder.

Beast’s body began to show the cost.

Old scars reopened.

His joints burned constantly.

His breath came harder in cold air.

Sleep was shallow and brief.

The mountain once his teacher now tested the limits of what he could endure.

But beast was no longer merely enduring.

He was planning.

He began preparing others quietly, not teaching the invention directly, but teaching observation.

He showed younger men how to listen to the ground, how to feel tension in rope, how to notice shifts before collapse.

He never framed it as rebellion or resistance, just survival.

Skills useful anywhere.

Some learned, some did not.

That was not his concern.

He also began leaving deliberate gaps, a support here that required adjustment at the right moment.

A system there that depended on timing no clock could measure.

Nothing obvious, nothing traceable, just enough that without him things would slowly unravel.

The whites noticed delays creeping back in, minor failures.

Among engineers who had once boasted mastery, they responded with anger, then panic.

Meetings were held, voices raised, blame shifted, beast watched from the edges, silent.

One night a white owner confronted him directly.

He demanded explanations, demanded full disclosure, demanded obedience.

He reminded Beast of chains, of ownership, of consequences.

Beast listened calmly.

When the man finished, Beast spoke softly.

“You break this,” he said, gesturing toward the mountain.

“It breaks you back.

” The owner struck him.

The blow hurt, but not the way the man intended.

It revealed desperation, loss of control, fear.

The next day, Beast was still taken to work, still relied upon, still necessary.

The strike changed nothing except Beast certainty.

By the end of the fifth year, the system Beast had created dominated the mountains.

Roots that once killed men now carried goods steadily.

Mines that once collapsed now held, profits soared, and at the center of it all stood a man still enslaved, still called beast, still bound by law, but holding the power of absence.

He knew now that staying would kill him eventually.

Slowly, efficiently, the way systems consumed resources until nothing remained.

So he prepared not to overthrow them, but to vanish, and when he did, he would take the mountains obedience with him.

It obeyed him.

That obedience had not come through force or domination, but through years of listening, of learning, where stone wanted to settle, where earth resisted, where pressure built quietly before release.

Beast had learned to read the mountain the way other men read ledgers or maps.

And now the whites depended on that knowledge so completely that they could not imagine their world without it.

That dependence sharpened into something ugly.

They began guarding him not like property but like a resource that might escape.

Men were assigned to follow him at a distance.

His move ants were noted.

His knights interrupted by sudden summons.

His shelter searched under the pretense of inspection.

Engineers watched his hands obsessively, trying to memorize motions without understanding purpose.

Beast noticed everything.

The mountain had taught him awareness long before the whites thought to fear it.

He could feel eyes on him, the way he felt pressure shifts in stone.

He adjusted accordingly, slowing gestures, masking intent, letting fatigue show where strength still lived.

They believed they were tightening control.

In truth, they were revealing fear.

The system Beast had created was now everywhere.

Supply lines stretched further.

Mines cut deeper.

Roads climbed slopes once thought impossible.

The entire region pulsed with movement shaped by his unseen hand.

And yet something began to go wrong.

Not catastrophically.

Not yet, but subtly.

A support failed earlier than expected.

A slope settled unevenly.

A route that had held for months required constant correction.

Engineers blamed one another.

Overseers blamed labor.

Labor blamed weather.

Beast said nothing.

He had designed it this way.

The invention, if it could be called that, had always been more than wood and rope and iron.

It was judgment layered a top structure.

It required timing, intuition, the ability to feel when the mountain was about to answer back.

Without him, those senses were absent.

The whites responded by demanding more of him.

He was dragged from one failing sight to another with increasing urgency.

Sleep vanished almost entirely.

Meals were eaten standing, if at all.

His body, already worn thin, began to rebel.

Pain radiated through his joints.

His hands shook when cold air cut too deeply.

Still he endured, but endurance was no longer the goal.

At night, when he lay staring at the dark ceiling of his shelter, Beast thought about collapse, not of roads or tunnels, but of systems.

He understood now that the whites had built their success on a single assumption, that he would always be there.

That assumption was their weakness.

He began accelerating the timeline, where once he had corrected small errors quietly.

Now he let them linger just long enough to cause inconvenience.

Where he might have anticipated a failure days in advance, now he arrived only hours before disaster, enough to save the structure, but not enough to prevent panic.

The whites grew frantic.

Meetings multiplied.

Voices rose.

Blame circled endlessly.

They pressed beast harder.

demanded more certainty, more guarantees.

He gave none.

Guarantees like freedom were illusions built on trust that did not exist.

One winter morning, a major route partially collapsed during transport.

No one died, but the loss was enormous.

Wagons lay twisted.

Goods spilled into ravines.

The failure could not be hidden.

The owners arrived in force.

They demanded answers.

They demanded to know why Beast had not foreseen it.

They demanded accountability.

Beast stood before them, shoulders bowed slightly from fatigue, chains loose, but still present.

The mountain shifted, he said simply.

They raged.

They accused him of withholding knowledge, of sabotage, of betrayal.

Betrayal, the word struck something deep.

Betrayal implied loyalty.

Loyalty implied choice.

Beast said nothing more.

That night, guards were placed closer to his shelter.

His tools were inventoried, his movements restricted.

The whites believed they were regaining control.

They were wrong.

Restrictions revealed desperation.

Desperation shortened sight.

Beast began preparing for departure in earnest.

He did not gather supplies openly.

He did not plan a dramatic escape.

That would draw pursuit, and pursuit in the mountains meant blood.

Instead, he prepared the system for life without him by making it fail.

Not suddenly, gradually.

He taught nothing new.

He corrected nothing unnecessary.

He let engineers make decisions without guidance.

He observed silently as errors compounded.

He watched frustration te earned to fear.

The whites had always believed the mountain was conquered.

Now it reminded them otherwise.

Accidents increased, delays multiplied, profits dipped, confidence cracked.

They responded with threats.

One evening, an overseer struck beast again, harder this time, fueled by panic rather than authority.

The blow split skin.

Pain flared.

The overseer expected submission.

Instead, beast met his eyes.

There was no anger there, no defiance, only certainty.

The overseer stepped back.

That moment mattered.

Fear had crossed a line it could not return from.

Beast understood now that his disappearance would not just harm their operations.

It would expose their arrogance.

It would force them to confront the truth they had avoided for years.

That the system worked not because of ownership, but because of understanding, and understanding could not be chained.

He began marking paths, not with signs, but with memory.

He recalled hidden roots he had walked alone, places where the mountain swallowed sound, narrow passes where pursuit would fail, sheltered valleys where fires burned unseen.

He had no intention of running blindly.

This would be deliberate.

Meanwhile, the whites argued over what to do with him.

Some wanted him moved south, others wanted him confined permanently.

A few quietly wanted him eliminated.

Every option carried risk.

They delayed.

Delay was fatal.

By the end of the sixth year, the mountain system was visibly unraveling.

Not collapsing entirely, but enough to bleed money and morale.

Engineers left.

Overseers quit.

Owners blamed one another.

And through it all, Beast continued to work.

Silent, exhausted, necessary.

The final decision was made without his knowledge.

They planned to remove him from the mountains, to send him somewhere flat, controlled, easier to watch.

where his invention would be less essential and his mind less dangerous.

They believed this would solve everything.

They underestimated the mountain one last time.

Beast learned of the plan from a frightened young laborer who overheard gods talking.

He listened without reaction.

He asked no questions.

That night, lying awake beneath a sky barely visible through trees, Beast felt something settle inside him.

Timing.

The mountain had taught him patience.

Now it demanded action.

He would not be moved.

He would not be broken.

He would not be used until nothing remained.

The system would fail and he would be gone before they understood why.

The sixth year ended with the mountain restless, shifting, groaning, waiting.

So was beast, and both were done obeying.

The mountain belonged to him, not in the way men claim ownership with deeds and fences, but in the older way, through shared memory, through survival earned inch by inch.

Every ridge had a lesson.

Every ravine held a warning.

Every stand of trees had once sheltered him from wind, rain, or men who hunted without understanding what they chased.

When the decision to move him was finalized, the mountain already knew.

beast sensed it in the air days before the guards spoke the order aloud.

The birds shifted patterns.

Stones loosened underfoot where they had been firm.

Weather rolled in too early, too sharp.

The mountain was preparing the way a body tightens before impact.

So was he.

The guards arrived at dawn with unfamiliar faces and too much confidence.

They carried fresh chains and papers stamped with authority.

One of them read the order slowly, as if savoring the sound of it.

Beast was to be transferred within the week.

No more mountain work, no more autonomy, no more wandering paths unsupervised.

Beast nodded once.

Compliance was expected.

Resistance anticipated.

Neither came.

That confused them.

Confusion always preceded mistakes.

In the days that followed, he worked as usual, too usual.

He fixed small problems quickly, smooth tensions, spoke more than he had in years.

He offered explanations when asked.

He corrected errors before they grew.

The W heights relaxed.

They believed he’d accepted his fate.

They did not understand that he was saying goodbye.

Beast walked the roots one final time, committing changes to memory.

A fallen tree here, a new rock slide there.

Water levels altered by late snowmelt.

He tested footings silently, noting where pursuit would stumble, where sound would carry too far, where shadows swallowed movement.

He left nothing marked.

Marks could be read by anyone.

Memory belonged only to him.

On the fourth night before his scheduled removal, a storm came down hard and sudden.

Wind tore through the canopy.

Rain fell sideways.

The guards cursed and huddled closer to their fires, pulling cloaks tight.

Beast volunteered to check a compromised support near a high pass.

No one questioned it.

They never did when weather turned dangerous.

Fear made them trust him more, not less.

Two guards followed at a distance, grumbling as they climbed.

By the time they reached the narrow section where the path thinned to a ledge, the storm had erased all sound but wind.

Beast stopped.

He bent as if inspecting stone.

Then he moved.

Not fast, not sudden.

He stepped sideways into shadow and vanished.

The guards shouted.

One lunged forward and slipped.

The other froze, unsure whether to advance or retreat.

By the time they recovered enough to act, beast was gone, absorbed by the mountain the way smoke disappears into night.

Horns sounded below.

Shouts echoed upward, distorted by rain and rock.

Men scrambled.

Orders contradicted one another.

The mountain turned their noise into chaos.

Beast did not run blindly.

He moved with precision.

He took paths no map recorded, descended through gullies where water erased tracks instantly.

Crossed scree slopes that shifted behind him like living things where pursuit might follow.

He doubled back briefly, then cut across sheer stone where only someone who knew the holds by feel could pass.

The storm became his ally.

Lightning flashed, illuminating chaos far below.

Lanterns scattering, men slipping, horses refusing terrain they sensed was wrong.

By dawn, the search was already failing.

The whites spread out, convinced he would head for known routes.

They guarded roads, bridges, valleys that once mattered.

Beast moved where they never looked.

He reached the old charcoal burner’s hollow by midday, a place abandoned years earlier, hidden by overgrowth and steep drop offs.

There he rested briefly, binding a shallow cut, listening.

No pursuit sounds, only the mountain breathing.

He knew they would not stop searching quickly.

Pride would demand his capture.

Fear would drive excess, so he did not flee far.

Instead, he circled.

Over the next weeks, beast became something else.

Not a worker, not a runaway, a presence.

Supplies vanished from remote camps.

Tools were found relocated, disassembled, rendered useless.

Supports failed not catastrophically, but inconveniently, just enough to halt progress and sow dread.

Men reported sounds at night, footsteps where no one stood, stones moved deliberately, fires extinguished without wind.

The whites began to whisper.

They called him beast again, but the word had changed.

Before it meant brute strength.

Now it meant something worse, something intelligent and unseen.

Search parties returned empty-handed, exhausted, afraid.

Some refused to go back into certain areas.

Horses balked.

Dogs lost scent repeatedly, circling in confusion before whining and retreating.

Beast never confronted them directly.

Direct confrontation invited legends to be disproven.

Fear properly cultivated needed ambiguity.

He watched from above as meetings turned frantic.

Engineers argued that the system was unstable without him.

Owners blamed guards.

Guards blamed terrain.

Terrain blamed beast.

They began to realize the truth too late.

The invention had never been the mechanism.

It had been the man.

And the man was free.

Winter crept in early that year.

Work slowed.

Profit sank.

The mount in roots became unreliable without constant intuitive correction.

Every decision now carried risk.

Some suggested abandoning the region entirely.

Others demanded harsher measures, burning sections of forest, setting traps, offering rewards for information.

None worked.

The mountain absorbed fire.

Traps caught animals.

Rewards produced lies.

Beast remained invisible.

But he was not idle.

He began shaping something new.

Small groups of laborers, runaways, displaced men, those who had vanished quietly, found their way to him, not by summons, but by rumor, a whispered direction, a sign understood only by those who knew what to look for.

Beast did not command them.

He taught them.

He showed them how to read stone, how to move without sound, how to survive where pursuit failed.

He gave no speeches.

He needed none.

The mountain itself became the lesson.

By the end of the seventh year, the whites no longer spoke of capturing beast.

They spoke of containing him.

They fortified towns.

They rerouted trade.

They avoided certain passes altogether.

Maps were redrawn to exclude areas no one dared enter.

The mountain was declared cursed.

That suited beast just fine.

On a cold evening, as snow began to fall, he stood on a high ridge and looked down at the lights below.

Smaller now, fewer, hesitant.

He did not smile.

Victory was not joy.

It was balance restored.

The mountain had been wounded.

He had been used.

Together they had answered.

The seventh year ended not with triumph, but with transformation.

Beast was no longer a man they could move.

He was a force they had to live around.

And the mountain at last was quiet again because it had been heard by the time the war came.

No one remembered when beasts stopped being a rumor and became a rule.

It happened slowly, the way weather changes a landscape.

One winter harsher than the last, one path abandoned, one decision altered out of fear rather than reason.

The White still owned land on paper, still signed contracts and issued orders, but everyone understood there were boundaries Inc.

could not cross.

Beyond certain ridgeel lines, beyond certain valleys, authority thinned and then vanished altogether.

Those places belong to the mountain, and the mountain belonged to beast.

He was older now, not old in years.

Those were impossible to count, but old in the way stone is old, shaped by pressure rather than time.

His body bore the record of survival.

Scars pale as frost, muscles hardened not by labor alone, but by restraint.

He moved more slowly, but nothing in his movement was wasted.

He had learned that power did not need speed once it had inevitability.

The settlements below had changed, too.

Where once men spoke loudly and laughed at danger, now voices dropped when the mountains loomed in view.

Children were warned not with ghosts or devils, but with a name spoken carefully, as if saying it too boldly might summon attention, beast.

No one knew where he slept.

No one knew how many followed him.

Estimates grew with fear.

10 men, 50, 100.

In truth, the number mattered less than the idea.

A handful of disciplined men who knew the land could shape the choices of thousands who did not.

And Beast knew that he had learned leadership the way he learned everything else by watching consequences.

He did not rule with commands.

He did not issue laws.

He shaped conditions.

Paths were made safe or dangerous.

Supplies appeared or vanished.

Those who respected boundaries traveled unmolested.

Those who tested them found routes impossible.

Equipment broken.

Courage drained.

Violence was rare.

Fear did the work better.

When the first rumors of war reached the mountains, beast listened without reaction.

North against south.

Where we stand when they do.

He refused to be drawn into battles not his own.

The mountain was not a banner to be carried into someone else’s war.

It was a refuge, a threshold, a reminder.

As armies marched and supplies strained, the importance of the mountain passes returned with sudden urgency.

Routes long avoided were reconsidered.

Maps were dusted off.

Confidence attempted a comeback.

It failed.

Scouts vanished.

Engineers miscalculated.

Entire units found themselves stalled by weather that seemed to come out of nowhere.

by landslides that waited just long enough to be unavoidable.

Some blamed bad luck.

Others whispered the old name again.

Beast watched from distance as desperation crept closer.

He allowed certain groups passage.

Runaways fleeing chaos, families seeking safety, men who asked permission rather than assuming it.

Others he turned away without confrontation, letting terrain deliver the answer.

The mountain became neutral ground.

That neutrality was power.

After the war ended and slavery collapsed under the weight of its own contradictions, officials finally dared to speak openly of Beast.

Papers recorded him as a criminal, a rebel, a destabilizing element.

Rewards were offered long after anyone expected to collect them.

No one did because Beast no longer existed in the way rewards required.

He had never sought recognition.

Freedom to him was not a document or a declaration.

It was the ability to choose where his presence mattered, and his presence now mattered everywhere the mountain shadow fell.

Years passed.

New men arrived, surveyors, investors, those who believe the old fears belong to another era.

They spoke of progress, of rails and roads, and extraction.

They brought machines and optimism.

The mountain answered patiently.

Tracks warped, foundations cracked, weather misbehaved, costs ballooned, accidents mounted.

One by one, projects were abandoned, each blamed on something different, none acknowledging the pattern.

Beast did not sabotage.

He corrected He corrected arrogance.

He corrected ignorance.

He corrected the assumption that land was passive and men were masters.

As his hair grayed, he began to teach less and observe more.

Others had learned enough to continue without him.

The knowledge had spread quietly, embedded in habits rather than rules.

That was the true invention, not the system that moved stone, but the system that moved thinking.

On a morning thick with mist, beast climbed to the highest ridge he still visited.

From there he could see the old roots faintly, scars softened by time.

He could hear distant activity.

Towns alive, cautious, but functioning.

The mountain was stable.

It no longer needed him the way it once had.

He sat on the rock and rested his hands on his knees.

The wind moved through trees with familiar rhythm.

Birds crossed patterns he recognized instantly.

He thought of nothing.

When he stood again, his joints protested briefly, then settled.

He left no mark as he descended, choosing a path no one else used anymore.

By the time people noticed his absence, months had passed.

Searches were symbolic, whispers confused.

Some said he had gone north, others said west.

A few insisted he had died quietly, alone, as mountains do not die loudly.

No body was found, no proof offered, only absence, and absence in that place meant intention.

Years later, a young engineer studying failed projects would remark that no one had ever successfully rebuilt the mountain roots to match their early promise.

Something always stopped them.

Not sabotage, not resistance, just a sense that pushing further was unwise.

Old men would nod and say nothing because some lessons were not meant to be explained.

They were meant to be respected.

The name beast faded from records then from speech.

But the boundary remained.

The habits remained.

The quiet acknowledgement that some forces did not announce themselves, did not demand recognition, did not vanish simply because power changed hands.

Beast had not freed the mountain.

He had reminded it of itself.

News

Ilhan Omar ‘PLANS TO FLEE’…. as FBI Questions $30 MILLION NET WORTH

So, while Bavino is cracking down in Minnesota, House Republicans turning the heat up on Ilhan Omar. They want to…

FBI & ICE Raid Walz & Mayor’s Properties In Minnesota LINKED To Somali Fentanyl Network

IC and the FBI move on Minnesota, touching the offices of Governor Tim Walls and the state’s biggest mayors as…

FBI RAIDS Massive LA Taxi Empire – You Won’t Believe What They Found Inside!

On a Tuesday morning, the dispatch radios in hundreds of Los Angeles taxi cabs suddenly stopped playing route assignments. Instead,…

Brandon Frugal Finally Revealed What Forced Production to Halt in Season 7 of Skinwalker Ranch….

The Secret of Skinwalker Ranch became History Channel’s biggest hit. Six successful seasons documenting the unknown with real science and…

1 MINUTE AGO: What FBI Found In Hulk Hogan’s Mansion Will Leave You Shocked….

The FBI didn’t plan to walk into a media firestorm, but the moment agents stepped into Hulk Hogan’s Clearwater mansion,…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage… It started like any other evening…

End of content

No more pages to load