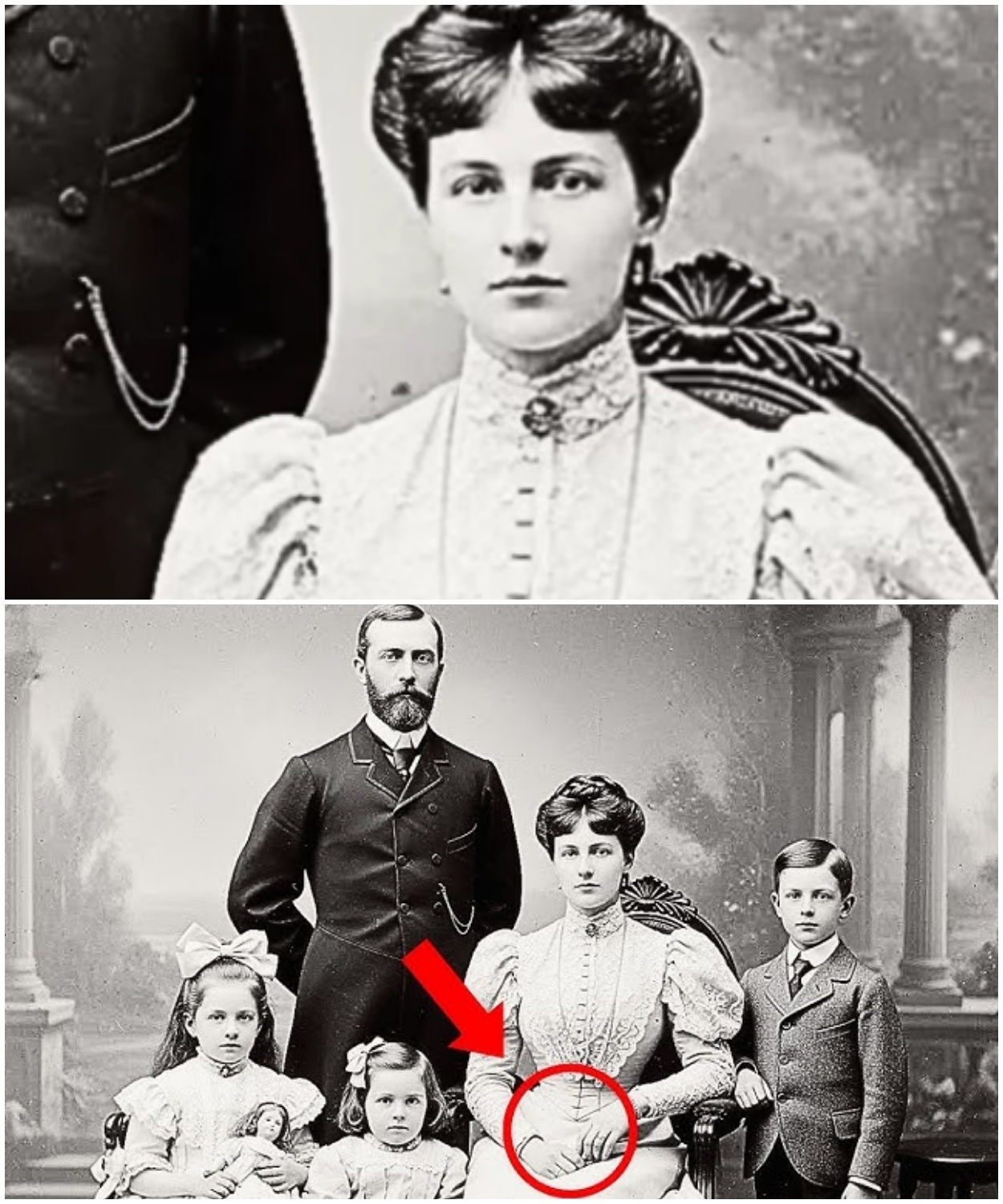

This 1890 family portrait is discovered, and historians are startled when they enlarge the image of the mother’s hand.

The afternoon light filtered through the dusty windows of Riverside Antiques, casting long shadows across rows of forgotten furniture.

Thomas Reed wiped his hands on his apron, surveying the estate sale items that had arrived that morning from a demolished rowhouse in South Philadelphia.

Most of it was unremarkable.

Chipped dishes, worn quilts, boxes of yellowed newspapers.

But then he saw it.

Leaning against a cracked mirror was a large wooden frame.

Its glass clouded with age, Thomas lifted it carefully.

Behind the grimy glass was a formal family portrait from the Victorian era.

The sepia tones had faded, but the image remained clear.

A stern father standing behind a seated mother, three children arranged around them, all dressed in their finest clothes.

Thomas carried the frame to his workbench near the window, where natural light revealed more detail.

The father wore a dark suit with a high collar.

The children stared at the camera with uncomfortable stillness, but it was the mother who drew his attention.

She sat perfectly upright, her dress elaborately detailed with lace.

Her face was beautiful but exhausted with deep set eyes that seemed to look past the camera.

Her right hand gripped the arm of the chair.

Thomas had dealt with hundreds of old photographs.

This one seemed ordinary at first, probably worth $50 to a collector, but something nagged at him.

An instinct developed over 20 years in the business.

He retrieved his jeweler’s loop and examined the photograph closely, starting with the studios embossed mark.

Whitmore and son’s photography, Philadelphia, 1890.

Then he moved to the mother’s hands.

Even through the faded sepia tone, he could see something wasn’t right.

The skin texture appeared rough, uneven.

There were marks, not soft wrinkles, but something harsher.

Thomas straightened up, pulse quickening.

He needed better magnification.

He carefully removed the backing of the frame and carried the original photograph to his photography station where he used a highresolution scanner.

The scanner hummed.

Thomas transferred the file to his computer and zoomed in on the mother’s right hand until it filled his entire screen.

His breath caught.

The hand was covered in scars, deep, obvious damage, burns that had healed badly, leaving the skin textured and discolored.

The fingers were slightly curved, as if they could no longer fully extend.

Along the back of the hand were puncture scars, small round marks in an almost geometric pattern.

Thomas sat back staring.

In all his years, he had never seen anything like this.

The formal portrait seemed designed to present this family at their best.

Yet the mother’s hand told a story of pain that contradicted everything.

Thomas spent the next morning at the Philadelphia City Archives, where centuries of records were preserved in temperature controlled rooms.

He had called ahead, and they had pulled boxes of business directories and city records from 1890.

The reading room was quiet.

Thomas sat at a long wooden table, carefully turning brittle pages of an 1890 business directory.

His finger traced down listings under photography studios until he found it.

Whitmore and Sons 1247 Chestnut Street fine portrait photography estster 1878.

He made note of the address then moved to city tax records.

Whitmore and Sons had been successful paying substantial taxes through the 1890s before closing in 1903 but the business records themselves were listed as destroyed by fire 1904.

Thomas felt his first lead evaporating.

Without customer records, how could he identify the family? He sat back, frustrated, when the archivist approached.

Finding what you need?” she asked.

Her name tag read Patricia Morrison.

Not exactly, Thomas admitted.

He showed her the highresolution printout.

I’m trying to identify this family.

The portrait was taken at Whitmore and Sons in 1890, but their records were destroyed.

Patricia studied the image, her eyes narrowing.

She lingered on the mother’s hand.

“May I?” she asked, reaching for her magnifying glass.

She examined the photograph for several long moments.

When she looked up, her expression had changed.

That hand, she said quietly.

Those burns and puncture marks.

I’ve seen similar injuries documented in industrial accident reports from that era.

Industrial accidents.

Thomas leaned forward.

The 1890s were brutal for factory workers, especially in textile mills and garment factories.

Patricia explained, “Women worked 12, 14-hour days operating dangerous machinery.

Burns from steam presses, puncture wounds from sewing machine needles.

These were common injuries.

” But she paused.

Women with injuries.

This severe rarely sat for formal portraits like this.

Studio photography was expensive.

This looks like an upper middle class family.

So, what am I looking at? Patricia was quiet, thinking.

There’s someone you should talk to.

Dr.

Helen Vasquez at Temple University.

She specializes in labor history, specifically women’s work in Philadelphia’s industrial era.

If anyone can help you understand what those injuries mean, it’s her.

Thomas wrote down the name.

Is there anything else that might help? Without a name, it would take months to search census records, Patricia said.

But that dress the mother is wearing.

The quality of the fabric, the lace work.

If she was a factory worker, wearing a dress like that would have been significant.

Maybe the only fine dress she ever owned.

Thomas looked at the photograph with fresh eyes.

He had been so focused on the scarred hand that he hadn’t considered the dress as evidence.

Dr.

Vasquez might recognize something, Patricia added.

She’s collected hundreds of photographs of factory workers from that era.

Thomas spent another hour copying records, but left with more questions than answers.

As he walked to his car, he wondered about the woman with the scarred hands.

Had she been proud when she sat for that portrait or ashamed? Dr.

Helen Vasquez’s office at Temple University was crammed with books, file boxes, and framed photographs of historical factory scenes.

Thomas knocked and a voice called out, “Come in.

” Dr.

Vasquez was in her late 50s with gray streaked hair pulled back in a ponytail.

She looked up from her desk, curious.

Thomas introduced himself and laid the highresolution print on her desk.

Dr.

Vasquez put on reading glasses and leaned close.

The silence stretched for nearly a minute.

When she finally looked up, her face had gone pale.

“Where did you find this?” she asked, voiced he tight.

“An estate sale in South Philadelphia.

” “Why? Do you recognize something?” Dr.

Vasquez stood and moved to a filing cabinet.

She pulled out a thick folder and spread out several old photographs showing women working in factories, at sewing machines, operating steam presses, hunched over cutting tables.

Their faces were exhausted, clothing simple and worn.

“Look at their hands,” she said, pointing to image after image.

Thomas leaned closer.

“In every photograph where hands were visible, he could see scars, burns, and deformities similar to those in his portrait.

But these women were clearly poor, dressed in workclo, these are garment workers from the 1890s.

” Dr.

Vasquez explained, “Philadelphia had dozens of garment factories south of Market Street.

Conditions were appalling.

Women worked from dawn until evening, 6 days a week, for wages that barely covered rent and food.

Steam presses caused severe burns, and industrial sewing machines had needles that broke frequently, sending metal shards through fabric into workers hands.

” She tapped Thomas’s portrait.

“But your photograph is different.

This woman has the injuries of a factory worker, but she’s dressed like someone from a completely different social class.

This dress alone would have cost months of a worker’s salary and the formal portrait setting.

That was something wealthy families did.

“So, how do I explain it?” Thomas asked.

Dr.

Vasquez sat back thinking.

Maybe she was a factory worker who married into a better situation.

Or maybe, she paused.

Maybe something else was happening.

What do you mean? In the 1890s, there was a growing labor movement in Philadelphia.

Workers were beginning to organize, demanding better conditions.

It was dangerous.

Factory owners fought back hard.

Workers who organized faced losing their jobs, blacklisting, even violence, but some persisted.

Dr.

Vasquez pulled out another file containing newspaper clippings.

In 1889 and 1890, there were several major strikes at garment factories.

Most failed.

The owners had police, courts, and newspapers on their side, but there were a few leaders who emerged, mostly women.

She spread out the clippings.

Thomas saw headlines.

Factory girls demand fair treatment.

Strike collapses after two weeks.

Most strikes were crushed, Dr.

Vasquez continued.

The women went back under the same terrible conditions, and leaders were usually fired and blacklisted.

Thomas looked at the portrait again.

You think she was involved in organizing? I think it’s possible.

Those injuries are consistent with years of garment factory work, and that photograph was taken at a pivotal moment.

If you can identify this woman, you might have found someone whose story has been completely forgotten.

The Pennsylvania Historical Society occupied a grand building on Locust Street.

Thomas had arranged access to their industrial records collection, specifically documents related to garment manufacturing in the 1880s and 1890s.

An assistant archivist named Robert brought out three boxes and set them on Thomas’s table.

These are from the Hartley Garment Company, one of the largest manufacturers during that period.

What exactly are you looking for? Thomas showed him the photograph.

I’m trying to identify this woman.

I believe she may have worked in a garment factory around 1890.

Robert studied the image, eyes widening at the scarred hand.

That’s severe.

Employment records list names, but they’re not organized helpfully.

You might be searching for days.

I have time, Thomas said.

He opened the first box and found ledgers filled with handwritten entries.

Names, dates, wages, hours worked.

The entries were tur hired March 1887, steam press operator, $4.

50 per week.

The wages were shockingly low.

Thomas calculated that 450 a week would be less than minimum wage today, and these women worked 12-hour days, 6 days a week.

After 2 hours, his eyes were tired from deciphering cramped handwriting.

He had found several entries mentioning injuries.

Sarah B.

Seamstress, injured, March 1889, hand burned by press, unable to work 3 weeks, wages docked.

These brief notations revealed casual cruelty.

Women hurt on dangerous machines, forced to work through pain or lose wages they couldn’t afford to lose.

Thomas was starting on the second box when Robert returned carrying a thin folder.

I remembered something.

In 1890, there was a strike at the Hartley factory.

It only lasted about 10 days, but the company kept a file on it.

There might be names.

Thomas opened the folder.

Inside were several documents, a memo from management, a list of workers suspected of organizing, and a newspaper clipping from the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin dated May 15th, 1890.

The headline read, “Lady garment workers demand better treatment, walk-off jobs.

” Thomas read carefully.

The article described how approximately 40 women from Hartley Garment Company had stopped work and gathered outside, demanding shorter hours, better safety conditions, and fair treatment of injured workers.

The strike had been quickly broken, but one paragraph made his pulse quicken.

The workers were led by Mrs.

Elizabeth Brennan, aged 29, a steam press operator who has worked at Hartley for nearly 8 years.

Mrs.

Brennan addressed the gathered workers and presented demands to factory management, who refused to negotiate.

She was terminated immediately and removed from the premises by police.

Thomas stared at the name, Elizabeth Brennan.

The age matched approximately with the woman in the photograph, and the timing was right.

He looked through other documents in the folder.

The management memo listed names of workers suspected of organizing.

At the top, Elizabeth Brennan, ring leader, immediate termination recommended.

Next to Elizabeth’s name, someone had written indifferent inc.

Blacklisted.

Do not rehire under any circumstances.

Thomas sat back, mind racing.

He had found her name.

Thomas spent the next week piecing together Elizabeth’s life from fragmented records.

The 1900 census showed her still married to James Brennan, living in a modest rowhouse in South Philadelphia with three children, Margaret, age nine, William, age seven, and Dorothy, age 4.

But something bothered Thomas about the timeline.

According to strike documents, Elizabeth had been fired and blacklisted in May 1890.

The census was taken in June 1890.

The photograph was dated simply 1890.

He returned to the Pennsylvania Historical Society and requested boxes containing management personnel records.

He found James’ employment record.

James Brennan, hired as floor foreman in January 1888.

Oversight of cutting room and finishing department.

Salary $18 per week.

$18 weekly was significantly more than women workers earned, but still modest.

[music] Thomas flipped through pages looking for notations during the strike period.

There, a brief entry dated May 20th, 1890.

James Brennan Foreman resigned position.

Departure effective immediately.

No reason given.

James had resigned just days after Elizabeth was fired.

That couldn’t be coincidence.

Had James quit in solidarity with Elizabeth, or had he been forced out because of his connection to her? Thomas found a partial answer in a memo dated May 18th, 1890.

Any employee found to be associating with or providing support to the strike organizers will be terminated immediately.

This includes all levels of staff.

Thomas could imagine the scene now.

Elizabeth leading the strike, being fired and forcibly removed by police, and James facing an impossible choice.

Disavow his wife or lose his position.

He had chosen Elizabeth, but how had they survived? With both suddenly unemployed and blacklisted, they would have struggled.

Yet somehow, they had scraped together enough money for that formal portrait.

And by 1900, James was listed as employed again, working as a warehouse supervisor.

Thomas needed to find living descendants who might have family stories.

He moved to modern genealogy records, searching for surviving family members.

After hours searching through obituaries and birth records, he found a lead.

William, the son in the portrait, had lived until 1972 and had three children.

One of them, a woman named Patricia Hughes, was still alive and living in a suburb west of Philadelphia.

Thomas found her phone number.

He sat for a long moment, staring at the number, gathering his thoughts.

Then he picked up his phone and dialed.

The phone rang three times before a woman’s voice answered.

Hello.

Hello.

Is this Patricia Hughes? Yes.

Who’s calling? My name is Thomas Reed.

I’m an antiques dealer in Philadelphia, and I’ve been researching a photograph I recently acquired.

I believe it shows your great-g grandandmother, Elizabeth, and her family from around 1890.

I was hoping I could talk to you about her.

There was a long pause.

Then, Elizabeth Brennan, how on earth did you find a photograph of her? It was in an estate sale.

I’ve discovered some interesting things about her involvement in the labor movement.

I’d love to share what I found and learn if you have family stories.

Another pause.

I’m 74 years old, Mr.

Reed, and you’re the first person outside my family who’s ever asked about Elizabeth.

Can you come to my house? I have things to show you.

Patricia Hughes lived in a neat ranch house in Binmore, surrounded by dormant November gardens.

Thomas parked and walked to the front door, carrying the framed portrait carefully wrapped.

Patricia opened the door before he could knock.

a tall woman with white hair and sharp blue eyes that reminded him of Elizabeth’s gaze.

“Come in,” she said, ushering him into a warm living room filled with bookshelves and family photographs.

“Let me see what you found.

” “Oh.

” Thomas carefully unwrapped the portrait and set it on Patricia’s coffee table.

She sat down slowly, her hand moving to her mouth.

“Oh my god,” she whispered.

“I’ve heard about this photograph my entire life, but I never thought I’d actually see it.

” “You knew about it?” Thomas asked.

My grandfather, William, the boy in the photograph, he used to tell stories about it.

The family lost it sometime in the 1930s during the depression when they had to sell their house.

Grandfather always regretted that.

He said it was important, that it meant something.

Patricia looked up, tears in her eyes.

What made you research this? Thomas explained about noticing the scarred hand, finding the strike documents, piecing together Elizabeth’s story.

As he talked, Patricia nodded, and when he finished, she stood and went to a cabinet.

Elizabeth was extraordinary, Patricia said, pulling out a worn leather box.

My grandfather told us she was the bravest person he ever knew.

She risked everything to try to make things better for the women she worked with.

She brought the box to the coffee table and opened it.

Inside were documents, letters, and photographs.

Patricia carefully lifted out a small notebook bound in faded cloth.

This was Elizabeth’s.

Grandfather kept it his entire life.

She used it during the strike to keep track of names, to organize meetings, to write down the demands.

Thomas opened the notebook with careful hands.

The pages were filled with Elizabeth’s handwriting, lists of names, notes about working conditions, drafts of letters.

One page listed grievances, burns from defective steam presses, no compensation for injuries, docked wages for time needed to heal, children working 12-hour days.

Another page showed demands 10-hour workday, safe equipment maintained by company, fair compensation for injuries, no wage penalties for injury recovery, no employment of children under age 14.

These demands were decades ahead of their time, Thomas said quietly.

Most of these protections didn’t become law until the 1930s.

Elizabeth knew what was right, Patricia said.

But the factory owners had all the power.

The strike was broken in less than 2 weeks.

Most women went back because they couldn’t afford not to.

But Elizabeth was made an example.

They wanted to show what happened to organizers.

And James quit to support her.

Patricia smiled sadly.

That’s the part that always moved me most.

[music] James had a good position, steady income.

He could have kept his job if he disavowed Elizabeth.

But he loved her.

He walked out the same day she was fired.

How did they survive? It was hard.

Very hard.

They borrowed money from friends, took odd jobs, struggled for months.

Patricia pulled out another photograph from the leather box.

It showed Elizabeth older now, perhaps in her 40s, standing in front of a small storefront.

A sign above the door read Brennan Tailoring and Alterations.

She became a seamstress again, but working for herself, Patricia explained.

She opened a small shop, did alterations and custom work.

It wasn’t much, but it gave her independence, and she never stopped advocating for workers.

In the 1900s and 1910s, when the labor movement started gaining momentum, Elizabeth was there attending meetings, supporting strikes, telling her story to young workers.

Thomas looked at the original portrait again, seeing it with new understanding.

The portrait, it was taken in 1890, right after the strike.

Why did they spend money they didn’t have on a formal photograph? Patricia’s eyes were bright.

That’s the most important part.

Grandfather told me that Elizabeth insisted on it.

She said she wanted a record of who they were at that moment.

A woman with scarred hands from factory work, a man who had chosen love and principle over security, and their children who would grow up knowing their parents had stood for something.

She wanted proof that they existed, that they mattered, that they had fought.

She reached out and gently touched the glass over Elizabeth’s scarred hand.

Elizabeth knew that history forgets ordinary people, especially women, especially workers.

She knew the factory owners would try to erase what had happened to pretend the strike never occurred.

So, she made sure there was evidence.

She wore her finest dress, held her head high, and let her scarred hands show because she wanted people to see what factory work cost and what fighting back cost.

She wanted future generations to know.

Thomas felt emotion tightening his throat.

“She succeeded.

The photograph survived and now her story can be told.

” “Will you tell it?” Patricia asked quietly.

“Will you make sure people know about Elizabeth?” “Yes,” Thomas promised.

“I will.

” Over the following days, Thomas and Patricia worked together to build a complete picture of Elizabeth’s life.

Patricia shared family documents and stories passed down through generations.

Thomas contributed research, finding newspaper articles and historical context.

They discovered that Elizabeth had been born in 1861 to Irish immigrant parents in Philadelphia’s crowded Suffach neighborhood.

Her father had been a dock worker who died in an accident when Elizabeth was 12.

Elizabeth had started working in garment factories at 13, helping her family survive.

By 20, Elizabeth had become skilled at operating steam presses, one of the more dangerous but better paying factory jobs.

She had sustained her first serious burn at 17 when a defective valve caused scalding steam to escape.

The factory refused to pay for medical treatment, and Elizabeth wrapped the burn in rags and continued working because missing shifts meant losing pay she couldn’t afford to lose.

The burns on her hand in the photograph, Patricia explained, [music] showing Thomas a letter Elizabeth had written in 1895.

Those were from multiple accidents over years.

Each time the factory blamed her for carelessness, docked her wages, and forced her back to work before she’d healed.

Thomas winced and the factory took no responsibility.

Factory owners in the 1880s and 1890s had no legal obligation to provide safe working conditions.

Patricia said women like Elizabeth were considered disposable.

They found records showing that Elizabeth had tried before the 1890 strike to organize smaller actions, petitions, delegations to management, informal work slowdowns.

Each time the efforts had been crushed, and women who participated had been punished with wage cuts or termination.

But Elizabeth had persisted, gradually building networks of trust among workers.

The 1890 strike had been her most ambitious effort.

She had coordinated secretly with women across multiple departments of the Hartley factory, setting a date when they would all walk off their jobs simultaneously.

The plan had been to overwhelm management’s ability to immediately replace them and force negotiations.

It almost worked, Patricia said, showing Thomas a letter Elizabeth had written to her sister in 1891.

For the first two days, the factory was completely shut down.

Management panicked.

>> [music] >> They called in police, threatened workers, tried to force everyone back, but the women held firm because Elizabeth had convinced them they deserved better.

Thomas read the letter written in Elizabeth’s clear handwriting.

We stood in the street outside that factory, Sarah, and we sang.

We sang hymns and folk songs, and we told each other stories about our injuries, our exhaustion, our children who never saw us because we worked dawn to dusk.

For two days, we weren’t just workers to be used and discarded.

We were human beings demanding dignity.

Even though we lost, even though I lost my position and may never work in a factory again, those two days matter.

They matter because we tried.

What broke the strike? Thomas asked.

Patricia’s expression darkened.

Desperation and fear.

The factory brought in replacement workers from other cities, offered them slightly higher wages.

Some of the strikers had children who were literally hungry.

They couldn’t afford to stay out another day.

Management also spread rumors that if the strike continued, the factory would permanently close and move to another city.

One by one, women started going back.

By day 10, the strike had collapsed, and Elizabeth was singled out.

She was made an example, Patricia confirmed.

The factory wanted other workers to see what happened to organizers.

She was publicly fired, physically removed by police, and blacklisted across Philadelphia’s entire garment industry.

No factory would hire her.

James was forced to resign because of management threatened him.

Thomas looked again at the portrait, at Elizabeth’s exhausted, but defiant expression.

Yet she insisted on that photograph.

She turned her firing into a statement.

Exactly.

Elizabeth understood symbolic power.

She knew that the factory owners wanted her to disappear, to be forgotten, to serve as a warning that silenced other workers.

So she did the opposite.

She put on her best dress, gathered her family, went to an expensive photography studio, and insisted that her scarred hands be visible in the portrait.

She was saying, “I exist.

What happened to me matters.

You can fire me, but you can’t erase me.

” Patricia pulled out one more document from the leather box.

A newspaper clipping from 1916, yellow and fragile.

The headline read, “Veteran labor advocate Elizabeth Brennan speaks at workers rally.

” The article described a large gathering of garment workers in Philadelphia, part of a nationwide push for better labor laws.

Elizabeth, now in her mid-50s, had been invited to speak about her experiences in the 1890 strike.

The 1916 newspaper article quoted Elizabeth’s speech.

26 years ago, I stood outside a factory with 40 brave women and demanded what should have been our basic rights.

Safe working conditions, fair wages, dignity as human beings.

We were defeated.

We were fired, blacklisted, threatened.

But we planted a seed that day.

And now looking at all of you gathered here, I see that seed has grown into something unstoppable.

Thomas read the article several times, moved by Elizabeth’s words.

She lived to see the movement succeed.

She did.

Patricia said, “By 1916, labor unions were gaining real power.

Laws were being passed to protect workers.

The Triangle Shirt Waist Factory fire in 1911 had shocked the nation and forced people to confront the brutal conditions in garment factories.

Elizabeth had been vindicated, and she knew it.

” Patricia showed him another document, Elizabeth’s death certificate from 1932.

She had lived to 71, dying peacefully at home, surrounded by her children and grandchildren.

James had died two years earlier.

Grandfather said that Elizabeth’s last years were happy.

Patricia told him she had her tailoring shop, which she ran until she was too old to work.

She had a close relationship with her children and grandchildren.

She attended labor rallies and union meetings until her health failed.

She saw the passage of major labor protection laws in the 1920s and early 1930s.

She knew that what she and those 40 women had done in 1890 had mattered, even though they had lost that particular battle.

Thomas carefully gathered all the documents and photographs Patricia had shared, making detailed notes.

What happened to the children? Did any of them follow Elizabeth’s example? Margaret became a teacher and was active in the teachers union, Patricia said.

William, my grandfather, became a labor lawyer, representing workers in disputes with employers.

Dorothy became a social worker, helping poor families navigate the city’s welfare system.

All three of them absorbed Elizabeth’s values and spent their lives fighting for fairness and justice.

She would have been proud.

Thomas said she was.

grandfather said she told him once that the portrait, the one you found, was her most prized possession because it showed the moment when she and James had chosen to stand for something larger than themselves, knowing it would cost them everything.

She said that photograph was proof that ordinary people could be heroic.

Thomas looked at the portrait one more time, seeing layers of meaning he hadn’t understood when he first found it.

[music] The scarred hands weren’t just evidence of suffering.

They were proof of resilience and courage.

The expensive dress and formal setting weren’t pretention.

They were an assertion of worth and dignity.

The exhausted but defiant expression on Elizabeth’s face wasn’t defeat.

It was determination.

“What will you do with the photograph?” Patricia asked.

“I’d like to donate it to a museum,” Thomas said.

“Along with all the research and documents you’ve shared.

” Elizabeth’s story should be preserved and told.

“People should know what she did, what she sacrificed, and what she achieved.

” Patricia nodded, tears in her eyes.

That’s exactly what she would have wanted.

She spent her life trying to make sure that ordinary workers, especially women, wouldn’t be forgotten by history.

Now you’re helping to fulfill that wish.

Will you help me? Thomas asked.

Will you work with me to make sure this story is told properly? Yes, Patricia said without hesitation.

Elizabeth was my great-grandmother, but she belongs to everyone who’s ever fought for justice.

Her story should be shared.

Six months later, Thomas stood in the Philadelphia Workers History Museum, watching as visitors examined the exhibition he and Patricia had created.

The centerpiece was Elizabeth’s portrait, now professionally restored and dramatically lit, hung at eye level so visitors could see every detail, including her scarred hands.

Around the portrait were displays containing Elizabeth’s notebook, the strike documents, newspaper clippings, letters, and photographs of garment workers from the 1890s.

Interactive screens allowed visitors to explore census records, factory conditions, and the broader history of labor organizing in Philadelphia.

Patricia stood beside Thomas, watching a young woman read Elizabeth’s letter about the strike.

The woman’s eyes were wet with tears.

“She’s really connecting with it,” Patricia whispered.

“A lot of people are,” Thomas said.

He had been surprised by the response to the exhibition.

Thousands of visitors had come in the first month.

Teachers were bringing school groups.

Labor unions were holding events at the museum.

Local news had covered the story and it had spread on social media.

The photograph of Elizabeth’s scarred hands had become an powerful symbol.

A middle-aged man approached them.

“Are you the people who created this exhibition?” he asked.

“We are,” Thomas said.

“Thank you,” the man said, his voice thick with emotion.

“My grandmother worked in garment factories in the 1920s.

She never talked about it much, but I remember her hands looked a lot like this woman’s.

Seeing this exhibition, learning this history, it helps me understand what my grandmother endured.

It makes me proud of her.

After he walked away, Patricia turned to Thomas.

This is what Elizabeth wanted.

She wanted people to remember, to understand, to honor the workers whose labor built this country, but whose stories were forgotten.

Thomas nodded.

Over the months of research and preparation, he had come to feel a deep connection to Elizabeth, even though she had died decades before he was born.

her courage, her determination, her refusal to be erased.

These qualities had inspired him and changed how he saw his own work.

A young girl, perhaps 10 years old, was staring intently at the portrait.

She turned to her mother and asked, “Why did she let her hurt hands show in the picture? Wasn’t she embarrassed?” Her mother read the explanatory text beside the portrait, then knelt down to her daughter’s level.

She showed her hands because she was proud of what she’d done.

She wanted people to know that she’d worked hard, that she’d stood up for what was right and that her life mattered.

She wasn’t ashamed.

She was brave.

The girl looked back at the portrait, studying Elizabeth’s face.

“She looks strong,” she said.

“She was strong,” her mother agreed.

“Thomas felt a lump in his throat.

That little girl would remember this moment, would remember Elizabeth’s story.

Maybe it would inspire her someday to stand up for what she believed in, to fight for justice, to refuse, to be silenced.

” Patricia squeezed his hand.

“Elizabeth’s not forgotten anymore,” she said quietly.

“Thanks to you, her story will be told for generations.

” “Thanks to both of us,” Thomas corrected.

“And thanks to Elizabeth herself, who had the courage and foresight to make sure there was evidence, who insisted on that portrait, even when she had almost nothing, who refused to disappear.

” They stood together in the museum, watching visitors engage with Elizabeth’s story.

The photograph that Thomas had found in a pile of estate sale items had become something far more important.

A window into a forgotten chapter of American history, a testament to courage and sacrifice, and a reminder that ordinary people fighting for justice can change the world even when they don’t live to see the full fruits of their efforts.

Elizabeth’s scarred hands, once a source of shame imposed by cruel factory conditions, had become a symbol of dignity, resistance, and hope.

And her story, nearly lost to time, would now inspire generations to

News

At 91, Shirley MacLaine Finally Tells the Truth About Rob Reiner

At 91, Shirley MacLaine Finally Tells the Truth About Rob Reiner You expect the black sunglasses, the prepared statements issued…

Tracy Reiner REVEALS what Rob Reiner told her before he passed

You have to understand that when the cameras turn off and the red carpets are rolled away, Hollywood is a…

A Case Too Disturbing for Netflix — 200 KKK Riders Never Returned Home

The Federal Investigators report sat in a locked file cabinet in Washington for 43 years before anyone read it again….

The Black Man Who Hunted the Ku Klux Klan

The rope burns told the story before anyone found the body. Isaac Woodard stood in the pre-dawn fog of a…

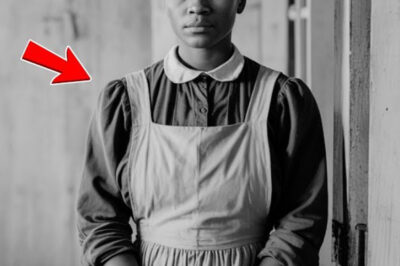

Clara of Natchez: Slave Who Poisoned the Entire Plantation Household at Supper

The crystal goblets caught candle light like captured fireflies, wine swirling crimson as 12 members of the Witmore family raised…

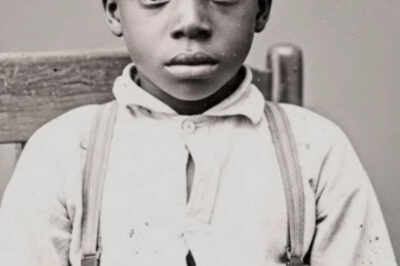

(1859, Samuel Carter) The Black Boy So Intelligent That Science Could Not Explain

In the suffocating autumn of 1859, in the isolated village of Meow Creek, Louisiana, a 7-year-old black boy named Samuel…

End of content

No more pages to load