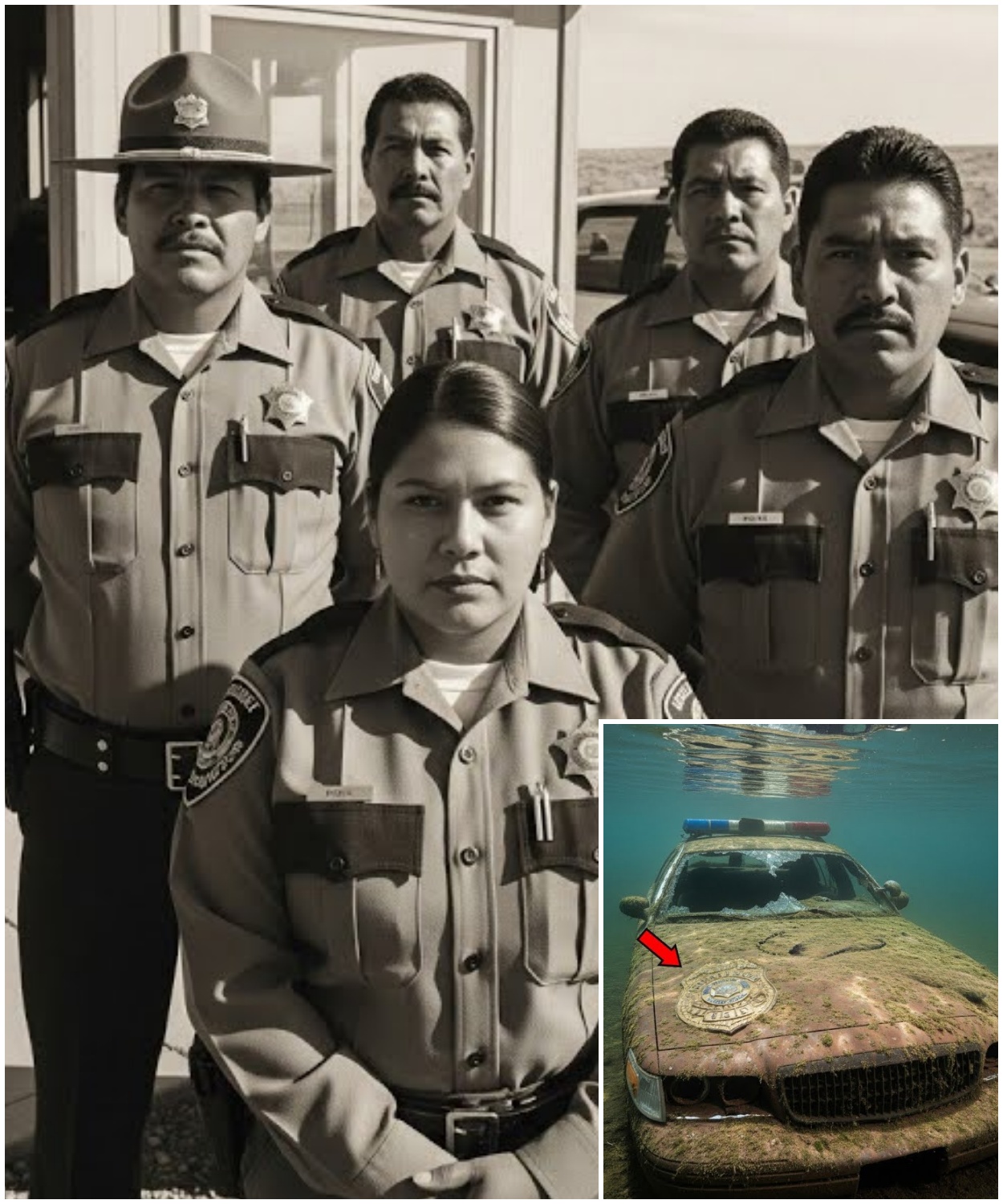

In the fall of 1993, five native deputies from the Willow Creek Tribal Police vanished without a trace.

They were on patrol just outside the reservation boundary in North Dakota, responding to what dispatch logged as a routine traffic obstruction call.

But after 9:47 p.m.that night, there was no further radio contact.

The cruiser’s GPS failed.

Backup was never called and the officers, four men and one woman, simply disappeared.

No bodies, no vehicle, no witnesses, nothing.

Local authorities offered quiet condolences, but didn’t investigate aggressively.

They suggested the deputies had likely driven off the edge of reservation land and become lost in a patch of rugged wilderness.

The phrase gone rogue was quietly floated through the official channels, but inside the tight-knit community, the word used was always the same, vanished.

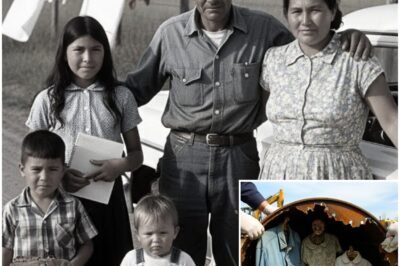

Among the five was Deputy Rachel Red Feather, a 28-year-old mother of two and the only woman on the tribal force at the time.

Her older brother, Carl Red Feather, was also on patrol that night, one of the missing five.

Their mother, Mara, would spend the next two decades lighting a candle in the window every evening, convinced that one day the cruiser would be found.

Everyone else was sure it was long at the bottom of one of the many glacial lakes that cut through the tribal land like scars, silent, deep, and forgotten.

The Red Feather siblings weren’t the only ones mourned quietly by the tribe.

Deputy Eli Goodbear, a decorated Marine Corps veteran, had returned to the reservation just two years earlier to serve as a peacekeeper.

He was respected and feared, a man known more for discipline than warmth.

Youngest of the five was Nolan Hawk, barely 23 and just a month into field duty.

His father was the tribe’s fire chief.

Rounding out the squad was Wallace Reigns, a quiet, stoic man with 20 years on the force and rumors of a resignation letter never filed.

What united them that night and what erased them is still not fully known.

In the days following their disappearance, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, BIA, filed a joint missing person’s case, but passed it quickly to state law enforcement.

The handoff was a formality.

No serious investigation took place.

A shallow search of the nearby tree line was conducted by volunteers.

The official report from the county sheriff’s office listed the incident as vehicle lost, presumed accident, officers unaccounted for.

Search efforts ceased entirely after only 11 days.

11 days or a whole patrol unit.

The tribe didn’t forget, but the world did.

22 years later, in the summer of 2015, a construction crew arrived at the west end of Dunlow Lake.

A new hydroelectric project was scheduled to cut a channel across the lake bed.

A temporary dam had been placed upstream, and the water levels had dropped drastically for the first time in half a century.

On the 12th day of excavation, the operators spotted something wedged into the mud and cattails near the old tree line.

It was the roof of a patrol cruiser.

Tribal insignia still faintly visible beneath the corrosion.

Within hours, recovery divers confirmed what the surface crew suspected.

This was the missing unit from 1993.

Inside the cruiser, partially preserved by the silt and cold, were two sets of human remains in the front seats.

There were no weapons recovered.

A pair of bloodied handcuffs was found on the rear floorboard.

The back right window had been smashed from the inside.

But that wasn’t the part that broke the silence.

Folded between the dashboard and the air vent, tucked tightly into the frame as if it had been jammed there in panic, was a sealed evidence bag.

Inside it was an audio cassette labeled in fading red ink.

Midnight Hawk, the name of the youngest deputy.

The FBI was brought in.

News vans followed.

For the first time in two decades, the reservation saw federal investigators on its soil, arriving not to offer protection, but to clean up their mess.

Mara Red Feather stood at the lakes’s edge as the cruiser was lifted out of the mud.

She didn’t say a word.

She just looked up at the sky and said softly, “Now let them speak.

” The tape would soon surface.

The story would start to unravel, but what it led to was something no one on the reservation or beyond was ready to believe.

The audio cassette labeled Midnight Hawk was rushed to a forensic lab in Bismar.

Given its fragile condition and water exposure, it was immediately placed in a vacuum chamber and carefully restored over the next 3 days.

Experts expected garbled static or faint background noise.

at best perhaps a bit of dispatch chatter.

What they recovered was far more disturbing.

The tape began with the sound of heavy breathing.

A man’s voice presumed to be Deputy Nolan Hawk could be heard whispering, disoriented, clearly injured.

If you’re hearing this, this is Nolan.

I don’t know where the others are.

We were pulled off course.

Something’s not right.

We weren’t supposed to go there.

The rest of the tape lasted 7 minutes and 49 seconds.

There were no direct names given.

But in a trembling voice, Hawk described how the patrol had been redirected by a radio call that didn’t come from dispatch.

He said the voice gave coordinates near Dunlow Lake, coordinates they weren’t supposed to patrol.

Then the signal cut off.

That’s when, according to him, someone else started transmitting.

No name, no badge number, just an unmarked voice directing them deeper into the woods.

Then silence.

The next minute of the tape was chaos.

Screeching tires, arguing voices, radio static, and finally a single scream.

At the very end, barely audible, a phrase repeated three times.

It wasn’t supposed to be us.

No one could fully explain the tape.

The FBI would later state it was inconclusive in content and origin.

But members of the Willow Creek community who listened said the voice was unmistakably Nolan Hawks.

Meanwhile, public pressure exploded.

For the first time since 1993, national news outlets ran the story of the five missing native deputies.

Headlines focused on the cruiser’s discovery, but underneath that was something far more painful.

Decades of federal neglect, jurisdictional confusion, and buried truths.

Carl Red Feather’s name became central to the narrative.

As both a missing deputy and brother to Rachel, his story carried weight.

Archived records unearthed from tribal council meetings in 1993 revealed that Carl had spoken publicly just weeks before the disappearance about suspicious offbook patrols being run near private oil drilling properties bordering tribal land.

He had raised alarms about radio interference and even filed an incident report that mysteriously disappeared from both tribal and county systems.

Some believed the squad had been lured.

Others suggested they stumbled onto something no one was supposed to see.

But then came a stranger twist.

A local man named Samuel Coats, a retired ranger who lived just outside the reservation, came forward after hearing about the cruiser’s recovery.

In 1993, Coats had been contracted by a private energy company, Resolute Extractives, to assist with land assessments.

He claimed that during a two-week assignment in late October, the same month the deputies vanished, he saw lights near the southern ridge of Dunlow Lake.

Flood lights, he said, like they were running operations, trucks, men in uniforms without insignia.

Coats reported that when he returned the next day, the area had been completely cleared.

No tracks, no equipment, not even tire marks.

He remembered it clearly because the ground was still wet from rain.

It looked like someone had scrubbed the place clean.

Nobody took his claim seriously in 1993.

He wasn’t native, had no ties to the tribe, and was dismissed by the sheriff’s department as hallucinating.

But in 2015, with a cruiser pulled from that very lake and a voice from the dead whispering through a damaged tape, Coat’s testimony couldn’t be ignored.

It triggered the release of dormant foyer requests filed years earlier by native advocacy groups.

Among the redacted documents was a brief memo referencing a joint training operation in late 1993 involving Resolute Extractives and the County Sheriff’s Department directly adjacent to the reservation boundary.

The memo was dated 3 days before the deputies vanished.

Back on the reservation, Mara Red Feather began organizing community prayer vigils near the lake.

She wasn’t interested in lawsuits or federal apologies.

I want truth.

No more graves underwater, she told reporters.

At one such vigil, a woman named Mavis Littlecloud, who had worked as a part-time dispatcher for the tribal police in the early ’90s, came forward quietly to Mara.

She hadn’t spoken publicly in over 20 years.

What she told her would shift the story again.

According to Mavis, the night the five deputies vanished, she received a second radio call after the patrol had already gone missing.

A low voice came over the emergency band.

It said only one thing.

Cruiser 4 is gone.

You didn’t hear this and then silence.

That message was never recorded in the logs because Mavis never wrote it down.

I was scared, she said, trembling.

They told us not to question the handover.

Said it was a state matter.

But that wasn’t the state.

That wasn’t anyone I knew.

Now over two decades later, the voice still echoed in her memory.

The mystery surrounding the missing deputies had turned from a local tragedy into something much darker.

something involving oil contracts, erased patrol logs, unofficial radio bands, and a community that had been told for years that its protectors simply disappeared.

But the deeper the tribe looked, the more it became clear the vanishing of those five officers wasn’t just about what they found.

It was about who they were.

By early fall of 2015, tribal elders, local journalists, and national media had converged on Willow Creek like a slowmoving storm.

The FBI released a tightly worded statement claiming it would fully investigate the circumstances surrounding the cruiser’s recovery.

But inside the reservation, no one believed that.

The phrase investigation had long since become a euphemism for delay.

And yet the case refused to die.

The recovered remains from the cruiser were positively identified through dental records as deputies Wallace Reigns and Rachel Red Feather.

That confirmation brought a brief wave of closure until the autopsy reports arrived.

Both skeletons bore signs of fractures inconsistent with crash trauma.

Rachel’s wrists showed micro fractures typical of prolonged restraint.

Wallace’s left femur had been shattered with no healing evident, suggesting it happened moments or hours before death.

But the most shocking discovery was the presence of duct tape fragments still embedded in the jaw hinge of Rachel’s skull.

The reports painted a brutal picture.

This had not been a patrol lost to accident or weather.

This had been an execution.

Three deputies still remained unaccounted for.

Carl Red Feather, Eli Goodbear, and Nolan Hawk.

The search for their bodies expanded across the wooded ridge bordering the lake.

Tribal volunteers, now joined by private forensic experts, began combing the overgrown trails once used by energy contractors in the early ’90s.

What they found was a buried crime scene.

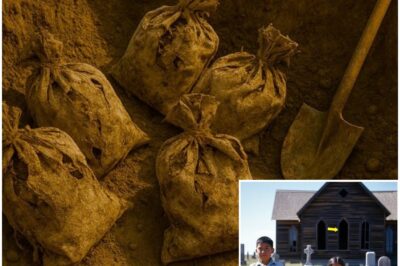

In a grove half a mile south of Dunlow Lake, a rusted, unregistered utility trailer was discovered.

Overgrown with moss and roots, it was only visible after several trees were cleared.

Inside, beneath rotted wood panels and coiled fencing, investigators found bone fragments, half-melted ID badges, and most chilling of all, a sheriff’s department duffel bag containing six sealed evidence envelopes.

Each one was marked with a date and a name.

Three of them matched the missing deputies.

These envelopes should have been in county records, but a cross reference showed nothing.

They’d never been entered into the system.

One envelope contained Rachel Red Feathers field notes from a prior investigation.

Specifically, a private security contractor named J.R.Klene, who had allegedly threatened her during a trespassing citation the year before she vanished.

In her own handwriting, she’d written Klene is not law enforcement.

Claims County gave him authorization.

Something’s wrong.

He’s always around the ridge line, never answers direct questions.

The page was torn near the bottom.

A smear of dried blood obscured the rest.

Investigators now had physical evidence connecting outside contractors, rogue law enforcement, and the final location of at least two of the victims.

But that wasn’t the only thread unraveling.

2 weeks after the trailer was uncovered, a woman named Denise Hawk approached tribal authorities.

She was Nolan Hawk’s older sister.

She had been living in Arizona since 1995 and had gone quiet after the case was dropped.

Now, she returned with something no one expected.

A letter.

Nolan had written it just 2 weeks before he vanished.

It was never mailed.

She found it folded in the back of an old field notebook while cleaning out their childhood home.

The letter wasn’t addressed to her, but to Carl Red Feather.

It read, “Carl, this isn’t the kind of thing you report.

Not yet.

But I saw the meeting.

I saw the file.

They’re not just leasing the land.

They’re burying waste near the reservoir.

You said don’t go looking.

” But I did.

They followed me back to the cruiser that night.

We’re not safe.

Promise me something.

If something happens, don’t let it go quiet.

That line became the rallying cry for a new wave of pressure.

Native advocacy groups began circulating petitions to unseal old land lease documents between Resolute Extractives in the county.

Journalists dug into corporate tax filings, discovering that Resolute had shifted ownership three times between 1991 and 1994.

One of the names listed as a silent stakeholder in the original incorporation documents, Sheriff Conrad Avery, the same sheriff who led the 1993 search.

The same sheriff who signed the final missing person’s closure reports.

The same man who shortly after the cruiser was pulled from Dunlow Lake in 2015 resigned without explanation and disappeared from public view.

Avery had not been seen since the week the autopsy results were released.

Suddenly, the case wasn’t just a tragedy.

It was corruption rooted, orchestrated, and buried across agencies.

In a quiet corner of the tribal records office, an archivist named Leonard Stone began cross-checking old arrest logs from 1992 to 1993.

Something wasn’t sitting right.

In the 6 months before the deputies vanished, there had been a 41% drop in tribal patrol reports.

Despite community complaints rising, nearly all field notes had been summarized without detail.

More importantly, nearly every report involving land boundary violations was listed under resolved, no citation.

Stone found something else.

A single log entry from Carl Red Feather’s patrol record dated one week before the vanishing.

10:12 p.m.

Saw three trucks along Ridgeline southbound.

No plates, armed men.

Attempted radio but received static.

We’ll try again tomorrow.

It was the last log entry Carl ever submitted.

Stone compared that entry to the next day’s digital upload.

It wasn’t there.

The file had been deleted.

Back on the ground, the search expanded.

And finally, 2 mi south of the trailer site, a tribal volunteer found something glinting in the dirt.

A badge cracked down the middle, still bearing the name Good Bear.

Buried beneath it, wrapped in tarp, were two long bones.

The forensic team arrived within hours.

Deputy Eli Goodbear had been found, but his skull was never recovered.

Only the badge, the bones, and the unmistakable message that someone had gone to great lengths to make sure these men and this story stayed buried.

The discovery of Eli Goodbear’s partial remains enough to formally reopen the case under federal jurisdiction.

The FBI reclassified it from a historical disappearance to a multi victim homicide involving potential government misconduct.

It was the first official acknowledgment in over two decades that something criminal had happened to the five deputies.

But on the reservation, that acknowledgment felt hollow.

The community had known all along.

What the feds called misconduct, tribal elders called a cover up.

The difference wasn’t just in language.

It was in lived experience.

While the FBI began their forensic sweep of the recovered trailer, badge site, and lakeside perimeter, a second front of the investigation was being quietly conducted by a group of native legal advocates and journalists.

They weren’t waiting for justice.

They were collecting their own evidence.

Leading them was a journalist named Talia Greywolf, whose uncle had served with the Willow Creek Police in the 80s and retired just 2 years before the disappearances.

Talia had started documenting the case back in 2009, long before the cruiser was pulled from Dunlow Lake.

Her notes, interviews, and filed FOA requests were meticulous.

And one particular interview stood out.

In 2011, she’d spoken to a man named Dale Kemp, a former employee of Resolute Extractives.

He’d worked as a security guard for just 6 months in 1993 and was fired shortly after October.

During their interview, he told her he’d been stationed at a makeshift checkpoint along the Southern Ridge near where the utility trailer would later be found.

He recalled something that never left him.

They had orders, radio silence, unmarked gear, and those deputies, they weren’t supposed to show up.

According to Kemp, the guards received a late night alert on the night of the disappearance.

5 minutes later, a truck tore up to the gate and men in body armor got out.

None of them local law.

They weren’t wearing sheriff patches and they weren’t tribal, but they had guns, radios, and they acted like they owned the place.

Kemp had tried to report it internally.

His termination letter came 2 days later.

Talia had recorded the interview and logged it away, thinking it was just another dead-end whistleblower.

Now, with three deputies confirmed dead, one still missing, and the cruiser unearthed, Kemp’s words took on new weight.

She dug through her files and reanalyzed the location he described.

The latitude matched precisely with the trailer discovery site.

The story had entered new territory.

Meanwhile, forensic teams uncovered fresh evidence from the recovered patrol cruiser.

Wedged beneath the rear seat carpeting preserved by water sealant and sheer luck was a piece of torn uniform fabric.

It bore the initials CR.

DNA testing confirmed it belonged to Carl Red Feather.

Blood analysis revealed traces of two other individuals, both matching the other deputies, but no traces of Nolan Hawk.

For the first time, the investigators began considering a terrifying possibility.

Was one of the deputies still alive when the cruiser went into the lake? Back in Willow Creek, Mara Red Feather received a visit from Agent Dana Herberts, the FBI lead on the case.

The agent explained that based on the position of the bones, the seat belt lock, and the blood spatter patterns, it appeared that one person had escaped the vehicle just before it sank.

Possibly through the broken rear window.

Possibly through the lake.

Mara’s hands trembled as she listened.

“Could it have been Carl?” she asked.

The agent didn’t answer, but in the very next press briefing, the FBI confirmed that at least one of the five deputies was never inside the cruiser when it went under.

The tribe responded not with celebration, but with heartbreak because if one had escaped, then someone had survived and was either silenced or still out there.

And then another break.

A man checked into a psychiatric facility in Montana under the name John Doe.

He had been living off-rid for years.

No ID, no records.

He rarely spoke, but in a moment of clarity, he told a nurse.

I watched them die.

I heard Carl say, “Drive.

” I remembered the sound when the water hit the glass.

The nurse wrote it off as delusional until she saw the local news about the cruiser.

She contacted authorities.

A DNA match later confirmed the impossible.

The man was Deputy Nolan Hawk.

Presumed dead for 22 years.

Nolan had somehow survived.

And now he was alive, but barely.

He hadn’t spoken since that single moment.

The FBI secured the facility and began medical and psychological evaluations.

They hoped for answers.

But inside that silence lay something deeper.

When Talia Greywolf requested to see him, she was denied.

But she managed to get a message delivered to him through a tribal liaison.

It read, “Your sister found your letter.

The land still remembers.

” The next morning, Nolan scribbled one word on a napkin during breakfast.

Ridge.

It was the only clue anyone had received directly from him.

Agents and tribal searchers focused their efforts on the high ground around the southern ridge, now believed to be the staging area for whatever had happened that night.

Ground penetrating radar was brought in along with cadaver dogs.

The search was slow, difficult.

Much of the terrain had changed over two decades.

But near the edge of a collapsed service road, they found another sealed compartment beneath a concrete slab.

Inside were documents, paper records stuffed into plastic drums, damaged but legible, blueprints, patrol schedules, handwritten notes, photos.

Many bore official seals.

Most were marked confidential willow expansion.

And at the bottom, a torn photo.

A group of men in tactical gear standing in front of a black SUV.

One man in the center wore a sheriff’s badge.

Sheriff Conrad Avery.

He wasn’t alone in the photo.

Behind him, just barely visible, was Carl Red Feather, handcuffed, still alive.

The photo changed everything.

For the first time since 1993, there was visual proof that Carl Red Feather had survived the initial disappearance, alive and in custody, shackled behind Sheriff Conrad Avery.

His expression was grim, his clothes disheveled, but his face showed no panic, only clarity.

He seemed to know exactly who was taking the photo, and perhaps more disturbingly, why.

The image, partially faded and creased at the edges, had likely been taken within 24 hours of the vanishing.

It was timestamped, but only with a handwritten scroll.

10:27 93, the exact day after the patrol went missing.

The other men in the photo were more difficult to identify, their faces obscured by sunglasses, ball caps, and poor resolution.

But their posture and gear suggested military training or at the very least private tactical experience.

It wasn’t standard law enforcement.

One figure, however, stood out.

On the left edge of the group stood a tall man in a gray jacket with a faded logo, Rex S12.

It matched the known emblem for Resolute Extractives internal security team.

With that, the entire narrative of the case shifted from missing officers to covert detention, corporate collusion, and extrajudicial actions on sovereign tribal land.

The FBI couldn’t ignore the implications any longer.

A quiet federal inquiry was launched into Resolute Extractives, but it moved slowly.

The company had since merged twice, rebranded once, and shifted its base of operations outside the US.

The paper trail was intentionally labyrinthan.

Still, leaks began emerging.

Internal emails, budget statements, surveillance logs, and in one heavily redacted document, a payment order appeared under a Shell consulting group registered to C.

Avery and Associates.

The date, November 1993.

Amount, $75,000.

Memo.

Site cleanup.

The exposure of the photo and leaked documents forced federal hands.

Congressional representatives called for an independent investigation into the Willow 5 case.

Civil rights attorneys called it one of the most deliberate abuses of jurisdictional gray zones in modern law enforcement history.

But inside Willow Creek, the mood was far from vindicated.

They weren’t interested in courtroom drama or televised hearings.

They wanted the truth.

And they wanted Carl Holm.

While federal officials wrestled with bureaucracy, Talia Greywolf and her team focused on the clue Nolan Hawk had given them.

Ridge.

Not the ridge near the trailer.

Another ridge.

one rarely spoken of except in older tribal stories and off-hand warnings from local hunters.

Known as Stone Shadow Ridge, it was once a ceremonial site, long closed to outsiders after the Federal Land Partitioning Acts of the 1950s.

Few living members of the tribe had ever walked it since.

Talia, with guidance from tribal elders and Mara Red Feather, secured a ceremonial blessing to survey the area.

The hike was grueling.

Dense growth, uneven terrain, and no clear trails.

But about 2 hours in, they came upon something that made every member of the search party stop in their tracks.

A rusted metal hatch half buried under pine needles and roots, unmarked, hidden in plain sight.

It took nearly 2 hours to pry it open.

Beneath it, a concrete shaft descending 15 ft into darkness.

An old ladder led down.

The air was stale, long untouched.

What they found below was a bunker, small, crude, but definitely man-made.

It was empty now, but not clean.

Scratched into one of the walls with what looked like a rusted nail were a series of tally marks, hundreds of them.

Next to them, carved slowly, were words, “I told the truth, they buried it.

” Beneath that, another line, “The land remembers.

So will they.

” DNA testing later confirmed trace amounts of Carl Red Feather’s blood and skin cells in the bunker.

Carl had been held there, likely tortured, possibly for months, possibly longer.

Why? That answer came days later when an anonymous package arrived at Talia Greywolf’s motel.

Inside was a cassette, the second one recovered in the case.

The label read Hawk, second transmission, 1994.

This tape wasn’t found in a cruiser or at the lake or near the ridge.

It had been mailed from an outofstate address with no return information.

It was sent directly to Talia.

What it contained stunned everyone who heard it.

Unlike the first panicked recording, this tape was calm, methodical, structured like a report.

Nolan Hawk’s voice came through clearly.

This is Deputy Nolan Hawk.

If you’re hearing this, I’ve failed, but I need the record to survive.

He went on to name the others.

Rachel, Wallace, Eli, Carl by full name.

Then he described what happened.

He confirmed that they were intercepted by non-uniformed men after being lured to the ridge by a false call.

The men took their radios, handcuffed them, and placed hoods over their heads.

One by one, they were separated.

The last thing he saw was Carl fighting off one of the men, screaming about land rights, while Avery shouted to get it done before daylight.

Then came the final moment on the tape.

If I don’t make it back, tell Mara I tried.

They said we saw something we weren’t supposed to, but we saw everything.

We heard them talk about dumping near the lake, about bribes, about clearing land before permits.

They said tribal cops don’t count.

Said no one would believe us.

They were wrong.

Click.

The tape ended.

The tape’s authenticity was verified by multiple experts.

It had been recorded on the exact same brand of cassette and same type of recorder as the first tape found in the cruiser.

Nolan’s voice matched perfectly.

But the real question was who sent it and why now? Had Nolan sent it before vanishing again, or was someone else watching, someone who had held the tape for over 20 years, waiting for the right moment to expose the truth? Investigators began working on tracking the package’s origin, but that would take time.

Meanwhile, a new location was circled on the map, just south of Stone Shadow Ridge, a site referred to in one of the leaked internal documents as zone K.

No context, no further description, just a time-stamped notation from October 1993.

Zone K, final staging complete.

Red team secured.

Excess moved to K South.

The next phase of the search would take them there.

And what they would find in zone K would shatter every remaining illusion about what really happened on the night five native deputies vanished.

Zone K was not marked on any current maps.

It didn’t exist in public records, county plat surveys, or tribal land grants.

The only reference was in that cryptic internal resolute extractives memo buried among lease agreements and staging orders.

It was just two words, zone K.

And yet, every lead, every clue, and every body had pointed steadily toward its existence.

Talia Greywolf and the triballed investigation team, now working alongside a small but trusted unit of independent forensic analysts, began triangulating its possible location.

Based on the dates, topography, and the last known movements of the deputies, they narrowed it down to a two-mile quadrant beyond Stone Shadow Ridge.

This section of land had been quietly sold by the state to a private energy holding company in 1992, only a year before the deputies vanished.

The buyer, a Shell corporation with known ties to Resolute Extractives.

That property had never been developed.

No buildings, no permits, no road access, just dense woodland and flat rock.

After securing access through tribal channels, the search team moved in on foot with drone support and GPR, ground penetrating radar.

It took 2 days of slow, methodical scanning before one of the drones picked up a heat signature anomaly, a cold spot deep underground with a perfectly rectangular outline, unnatural, man-made.

They marked the coordinates and began excavation.

Less than 4 ft below the surface, the team uncovered a reinforced steel door.

No markings, no signage, just a corroded locking mechanism and a keypad rusted shut from decades of exposure.

Bolts were cut manually.

The door groaned open, loud, angry, and reluctant to reveal what had been hidden.

The air inside was dry, metallic, and smelled faintly of oil.

The walls were cement.

No decoration, no wiring except a string of long dead bulbs nailed crudely along the ceiling.

This wasn’t a facility.

It was a holding site.

At the end of a narrow hallway sat a single metal door.

On it, scratched with something sharp and determined, were two words, Carl Red Feather.

Inside the room, they found what was left of a makeshift cell, chain loops embedded in the walls, a wooden chair with leather restraints, an overturned cot, and beneath it, a rusted tin box filled with torn paper, water damaged notes, and what appeared to be the remains of a deputy’s badge.

The number was illeible, but the handwriting on the paper was unmistakable.

It was Carl’s.

Some pages were gibberish, stream of consciousness thoughts etched in panic.

Others were lucid, heartbreaking, and horrifying.

One read, “They took us for seeing, for hearing, not for doing.

” I didn’t even write it down, but they knew the ridge was never ours.

It was leased, sold beneath our feet.

Another, they said, “No one comes back from zone K, but I’m still here for now.

” And finally, they think if they bury you deep enough, you disappear.

But the land always remembers and the water never forgets.

Among the notes was something else.

A handdrawn map.

Crude but detailed.

It showed not just zone K, but additional labeled sectors.

K south, bridge point, and something marked only as the pit.

Talia took photos of every page.

The full implications were staggering.

This wasn’t a one-time abduction.

It was a system, a multi-sight operation designed to suppress, silence, and dispose of witnesses.

All tied to illegal drilling, waste dumping, and land seizure beneath sovereign territory.

Back in DC, word of the discovery reached federal ears.

A classified task force was formed and for the first time tribal officials were invited to observe, but many refused.

They had no faith in federal oversight anymore.

Instead, the Red Feather family held a private ceremony at the entrance to the Zone K bunker.

Mara, now physically frail but emotionally fierce, stood beside Talia, holding Carl’s recovered pages to her chest.

We don’t need them to tell us what happened, she said.

We just need them to stop pretending it didn’t.

3 days later, in a federal facility in Montana, Nolan Hawk spoke for the first time in over two decades.

Only two words, the pit.

Authorities scrambled to make sense of it, cross referencing with Talia’s map and Carl’s notes.

The area labeled the pit was less than half a mile southeast of zone K, but inaccessible by foot due to a collapsed ravine.

Satellite imagery showed an unnatural depression in the earth nearly 70 ft across.

The FBI dispatched a forensic ground team.

It took them nearly a week to reach the site.

What they found would become the centerpiece of the entire case.

A mass grave, dozens of skeletons, some recent, others decades old.

Not just the missing deputies, not just Carl.

There were women, children, elders.

None of them were ever reported missing through official channels.

Some had tribal ID cards buried with them.

Others were unidentified.

The excavation took weeks, and by the end of it, 37 human remains had been recovered.

It was no longer just about the Willow 5.

This was evidence of a pattern.

Generations of disappearances masked by land disputes, jurisdictional passoffs, and corporate secrecy.

And all of it had been kept beneath the soil.

That night, Talia sat with Nolan Hawk in the facility’s visitation room.

He didn’t speak, but she laid the photograph of the ridge on the table, the one with Carl in cuffs.

He looked at it for a long time.

Then he nodded just once.

It was the confirmation they needed.

The tribe began preparing a formal memorial for all recovered souls.

Not just the five deputies, but every unnamed voice silenced in the woods, drowned in the lakes, buried beneath corporate concrete.

But the reckoning wasn’t over.

Because Sheriff Conrad Avery still hadn’t been found, and he wasn’t the only one who disappeared.

Sheriff Conrad Avery had been the unspoken ghost at the edge of every headline, every vigil, every uncovered piece of evidence.

By 2015, he was a retired man in his 70s, last publicly seen stepping down from office just 4 days after the cruiser was pulled from Dunlow Lake.

No press conference, no statement, just a quiet resignation and a forwarding address in Idaho that turned out to be a vacant trailer.

Federal authorities had labeled him non-compliant, meaning he hadn’t responded to requests for interview.

But among the people of Willow Creek, the belief was more direct.

Avery had run and not alone.

Talia Greywolf, now functioning as both journalist and de facto case archavist, began tracking Avery’s known associates from the early 1990s.

She cross-referenced land records, law enforcement rosters, campaign donors, and personnel contracts from the Resolute Extractive Security Registry.

What emerged was a web, a circle of eight men, all white, all county affiliated, all of whom held direct roles in either security, law enforcement, or land commission decisions in the three years before the deputies vanished.

Five of those men were already dead.

Heart attacks, hunting accidents, a boating collision.

Two others had left the country.

One was living in Costa Rica under a business visa.

The other had reportedly changed his name.

That left only one name active and traceable within the US.

Gregory Yates, former county records officer, the man who had signed off on the missing patrol logs.

Talia located him in rural Missouri, living under his real name, but off-rid.

No social media, no digital footprint.

When she arrived at his property with a small film crew and a tribal liaison, Yates refused to open the door.

But just before she turned to leave, he cracked it open an inch.

“You’re looking for Avery,” he said without prompting.

“Talia didn’t respond.

” Yates continued.

“He’s in Canada.

Used an old hunting cabin we all chipped in on back in the 80s.

He doesn’t go into town.

Doesn’t trust anyone.

But if you want to find him, look for the Burns.

” “Burns?” Talia asked.

He closed the door.

It took four more days before a satellite imaging scan secured through a contact in investigative media revealed a small clearing deep in the northern woods of Alberta just past the provincial line.

Barely visible, a single structure and three patches of scorched earth surrounding it.

On the fifth day, Canadian authorities acting on a diplomatic request raided the property.

They found Conrad Avery alive, thin, sickly, and in possession of a half-burned cache of documents.

He surrendered without resistance.

What they recovered from the property filled six boxes, and a small fireproof safe.

Inside the safe, field reports from 1993, tribal patrol schedules, land contract ledgers, and three cassette tapes.

Each one labeled only with a number.

Uo 1’s 203.

The first two were blank, but the third 03 was not.

It was a recorded confession.

Avery’s voice, slower now, raspier, began.

They were never supposed to be there.

That’s what they told me.

That night, the whole unit just wasn’t supposed to be on that ridge.

We had a deal.

The company got its land.

We kept the peace.

No interference.

He went on to explain that in October of 1993, Resolute had been disposing of unregulated chemical waste into the natural aquifers beneath the reservation’s eastern border.

The waste was shipped under falsified manifests labeled as equipment cleaning fluid, but the composition, later tested, was toxic and federally banned.

Avery had accepted payments to reroute tribal patrols away from the ridge for 2 months.

But on the night of October 26th, the call logs show that Carl Red Feather manually redirected his unit to investigate what he believed were illegal trucks operating after curfew.

Avery panicked.

He made a single call and within 90 minutes, the entire unit had vanished.

In the confession, Avery claimed he never intended for them to be killed, only held, threatened, scared off.

But something went wrong.

He blamed the private contractors for escalating it.

They made it permanent, and once it’s permanent, you can’t take it back.

He ended the recording with a flat, broken statement.

They were the best of us, and we gave them to the wolves.

The tape was turned over to tribal authorities in the Department of Justice, but the community didn’t want apologies.

Not anymore.

They wanted closure.

Conrad Avery was extradited to the US and charged with obstruction of justice, conspiracy, unlawful detention, and accessory to multiple homicides.

His trial was set for the following spring.

But just 6 days before jury selection began, Avery was found dead in his holding cell.

Heart failure, no foul play, no confession in court, no final statement.

The only words left behind were on the tape.

And in the fireproof safe beneath the cassette recorder was one last item, a letter addressed to the families of Willow Creek.

It read, “I kept the files.

I didn’t want them erased.

Maybe that makes me a coward.

Maybe it makes me guilty.

But I wanted you to know not everyone wanted this.

Some of us tried to speak.

But the system didn’t just silence you.

It silenced us, too.

The letter was unsigned.

But inside it, folded carefully, was a photo from 1984.

A team of 10 tribal officers, young, hopeful, standing in front of the Willow Creek Police Station.

Among them, Carl Red Feather, Rachel, Eli, Wallace, and Nolan, all smiling.

The tape was archived.

The evidence was sealed.

But the memory was beginning to rise because now, for the first time, the world was listening.

After Avery’s sudden death in custody, the Department of Justice moved swiftly to avoid further public embarrassment.

Internal memos were circulated to manage narrative exposure, and select federal officials began negotiating with Willow Creek’s tribal council to offer reparations, settlements, and development grants in exchange for cooperation and silence.

But this time, the tribe refused.

No amount of money could cover what they now knew.

The final missing piece, the last of the Willow 5, was still unaccounted for.

Carl Red Feather.

His blood, his notes, his name etched on concrete and scratched into rusted walls.

But no body, no grave, no closure until the audio engineer reviewing the third tape from Avery’s safe noticed something strange.

After Avery’s recorded confession ended and the tape fell into silence, there was a second layer of audio, barely audible beneath the hiss.

It hadn’t been erased properly.

A forensic sound team extracted the subtrack.

It was older, fainter, but it was Carl’s voice.

Not a scream, not a panic, not a call for help, a statement.

This is Officer Carl Red Feather.

If this is found, know this.

We didn’t stumble onto anything.

We were watching.

We knew.

We had evidence.

And the only mistake we made was trusting the badge.

He went on to describe how he had been compiling a dossier over 3 months before the disappearance.

Land parcel maps, dump site photos, water contamination logs.

He had taken it all quietly, carefully, intending to present it to the tribal council and then to the press.

But someone had tipped off the wrong people.

The cassette ended with one final sentence.

Tell my mother I didn’t run.

Tell her I walked into the fire because someone had to.

That clip aired on national news.

And suddenly, Carl Red Feather wasn’t just a missing deputy.

He became a symbol.

Within weeks, journalists began uncovering similar stories from other reservations, unexplained patrol disappearances, boundary violations, ghost calls over unsecured radio lines, quietly closed investigations involving native officers.

One case from 1981 in Montana, another in Arizona from 1987.

Both involved deputies who lost contact while investigating land disputes and were never seen again.

Carl’s name gave them a voice, but the final answer still hadn’t arrived.

That’s when Nolan Hawk, whose speech had been reduced to fragments and silences, broke through again.

On an unannounced visit, Talia Greywolf handed him a folded copy of the old team photo, the one with all five deputies in uniform.

years before their final shift.

He stared at it for a long time.

Then in a low whisper, “They didn’t kill Carl,” Talia sat up.

He continued, still haltingly but clear.

“They moved him,” said too visible, too risky.

Took him past the ridge, past the water, not dead.

Talia asked, “Where is he?” Nolan didn’t know, but he said one word again, the same as before, the pit.

They had already excavated the known grave site.

But the map Carl had drawn showed a second hollow just southeast near a dried up aqueduct.

It had been dismissed as erosion at the time, but new scans revealed a concrete slab buried beneath layers of limestone and roots.

When they broke it open, they didn’t find a body.

They found a sealed archival crate.

Inside it, a film reel, three hard copy dossas, and a stack of unprocessed photographs.

Some were grainy, others clear.

They showed trucks, barrels, drilling units, and marked boundaries crossing illegally into sovereign land.

They also showed Carl, alive, standing beside what looked like another man, older, native, unknown.

In the real once restored, Carl is heard speaking off camera.

This isn’t just about water or waste.

This is about who owns the future.

They’re bleeding us dry because they know we can’t stop them.

Then the camera pans to show rows of barrels marked with chemical codes later identified as banned industrial solvents.

The footage confirmed everything and more.

Because included in the dossier was a signed confession, not by Avery, but by a federal contractor admitting to operating classified containment support near Willow Creek between 1991 and 1993.

The contractor’s name was redacted, but the signature was partially legible.

initials JR KJR Klene, the same private security figure Rachel had written about in her field notes before she disappeared.

He had been real.

He had been there and he had documented it all, perhaps thinking he was protecting his own liability, but in doing so, he had left the paper trail that would unravel it all.

Klene was believed dead, a boating accident in 1999.

No body recovered, but now that didn’t seem like a coincidence.

The Department of Justice was forced to respond.

A special task force was formed to investigate federal contractors operating on or near native land between 1980 and 2000.

Congressional hearings were scheduled.

Whistleblowers began coming forward anonymously, sharing details about Operation Ridge, an unconfirmed internal program designed to monitor and pacify tribal resistance to federal resource contracts.

Willow Creek had been one of its test beds.

The missing deputies hadn’t just stumbled into a crime.

They had uncovered a national program.

Carl Red Feather had likely been held as a deterrent, a prisoner to ensure silence.

And perhaps, just perhaps, he had lived long enough to leak the files, hide the footage, and deliver his final message through a secondhand ghost, Nolan Hawk.

The tribe declared April 12th Red Feather Day, not as a memorial, but as a vow.

A vow to remember, a vow to protect, and a vow to never let silence bury truth again.

But even with justice approaching, one question remained.

Where was Carl? For all the revelations, records, graves, and confessions that surfaced in the two years following the discovery of the cruiser.

The question that haunted every conversation was the same.

What happened to Carl Red Feather? He had survived the ambush.

He had been detained, possibly tortured.

He had left behind tapes, maps, and messages.

He had known what was coming, but he was still missing.

By the winter of 2017, much of the Willow Creek case had become public knowledge.

The federal investigation into Operation Ridge was underway.

Several retired contractors had testified under immunity.

Yet none of them could or would confirm Carl’s fate until a name surfaced from an unexpected source.

While digging through old lease contracts and personnel transfer records tied to Resolute Extractives, Talia Greywolf found an irregular billing entry, a monthly stipend paid for offsite housing security.

It had been listed under a contractor alias, but the address pointed to a remote rehabilitation ranch in Yukon Territory, Canada.

The property had changed names three times since 1993.

One of its former names, St.

Elias Transitional Health Unit.

She cross referenced the location with the timeline.

It matched a quiet period between 1994 and 1997, right after the ridge vanishing.

a time when multiple classified payments had been routed to foreign contractors.

She presented the findings to the tribal council.

The elders made a decision.

They would go themselves.

A team of six traveled north, including Talia, Mara Red Feather, a medical examiner, and three tribal officers.

They didn’t involve media, no FBI, no press, just the people who had suffered the silence the longest.

When they arrived at the rural property, now a private care facility, they were met with resistance.

The administrator denied that any American nationals had been housed there during the 1990s.

Claimed no record survived a fire that occurred in 2003.

But the truth was in the land again.

One of the older staff, a maintenance worker, approached Mara in private.

He said, “There was a man here.

Quiet.

didn’t speak.

We called him Charles, but he had eyes like someone who remembered everything.

He left before the fire.

Walked into the woods one day.

Never came back.

When asked how long he had stayed at the facility, the worker answered about 8 years since around 94, I think.

They showed him a photo.

Carl Red Feather.

The man didn’t even blink.

That’s him.

I used to bring him books.

Carl had survived.

He had been held for nearly a year, maybe more, then moved, not killed, tucked away in a place far from media, justice, or memory.

No name, no visitors, no questions asked.

And then one day, he disappeared again, but this time on his own terms.

The team returned to Willow Creek with no body, no grave, no final confirmation.

But for Mara, it was enough.

Her son had not broken.

He had not been discarded.

He had outlived the silence.

Then came the final unexpected twist.

6 months later, during a cultural preservation survey of the old Stone Shadow Ridge Trail, a hiker found a tree marked with carved symbols.

Not initials, not a name, but tribal pictographs.

one translated to truth, the other witness, and below them a date.

October 26th, 2018, exactly 25 years after the vanishing.

Fresh, precise, recently carved.

Only one person would know that date, and only one man had the training to survive that long, off-rid, unknown to the world.

Carl Red Feather was no longer missing.

He had become a guardian.

Some say he returned to the land that tried to forget him, not to be found, but to keep watch.

Because some ghosts don’t haunt out of pain, they haunt out of duty.

And in the eyes of Willow Creek, Carl wasn’t dead.

He was still on patrol.

The events of the Willow Creek investigation reshaped more than just a small reservation in North Dakota.

They rattled the very foundation of how native voices were treated, how crimes were documented, and how justice was selectively applied across sovereign land.

By 2020, thanks to the relentless efforts of the Red Feather family, Talia Greywolf, and dozens of tribal leaders and grassroots advocates, the US Senate held a formal hearing titled Forgotten Protectors: Systemic Failures in Native Law Enforcement Disappearances.

It opened with a moment of silence for five names.

Rachel Red Feather, Wallace Reigns, Eli Goodbear, Nolan Hawk, Carl Red Feather.

Only four bodies had been recovered.

One had survived and vanished again, but all five had exposed a system so carefully buried that its very existence had been denied for over two decades.

The hearing led to the declassification of over 2,000 pages of federal documents, including internal directives that had once authorized surveillance and covert suppression tactics under the pretense of resource protection initiatives.

Buried deep within was the operational schema for Operation Ridge, confirming what the people of Willow Creek had always known.

This wasn’t a tragedy.

It was a design.

a system that used jurisdictional loopholes, corporate funding, and bureaucratic indifference to exploit native land while silencing those who protected it.

The government issued a formal apology in 2021.

It made national headlines.

But for Willow Creek, apologies had no weight.

So instead, they built something.

Where the patrol station once stood, the tribe raised a memorial complex.

Not just for the five deputies, but for all indigenous law enforcement officers lost, erased, or ignored in the line of duty.

At the center stood a Blackstone monument with a simple inscription, “We were never lost.

We were taken.

We were never silent.

You just weren’t listening.

” Each year on October 26th, people gather at the lakes’s edge where the cruiser was pulled, where the water once held the truth.

Elders speak, families light candles, drums echo into the trees, and always someone leaves a single badge in the soil beneath the monument.

A silent nod to those still missing, to those never acknowledged, to those who returned but never came home.

Talia Greywolf published her book later that year, The Ridgeline: How Five Native Deputies Broke a Silence That Tried to Bury Them.

It became a national bestseller and is now taught in multiple criminal justice programs across the country.

But for her, the book wasn’t the end.

It was just a marker.

Because the real ending, it never came.

Not fully.

There were still unanswered questions.

Still unidentified bodies from the pit.

Still whispers that Carl Red Feather had been seen just once crossing a frozen road two towns over, wrapped in a coat older than most of the officers stationed there.

They didn’t stop him.

They didn’t question him.

They just watched him disappear into the snow.

Some believe he’s dead.

Others believe he became something else.

A symbol, a shadow, a reminder that silence has weight.

And justice, real justice, doesn’t arrive on time.

It walks slow, deliberate, unseen, just like he did.

News

El Mencho’s Terror Network EXPLODES In Atlanta Raid | 500+ Pounds of Drugs SEIZED

El Mencho’s Terror Network EXPLODES In Atlanta Raid | 500+ Pounds of Drugs SEIZED In a stunning turn of events,…

Federal Court Just EXPOSED Melania’s $100 Million Crypto Scheme – Lawsuit Moves Forward…

The Melania Trump grift machine, $175 million and counting. Okay, I need you to stay with me here because what…

Trusted School Hid a Nightmare — ICE & FBI Uncover Underground Trafficking Hub

Unmasking the Dark Truth: How Human Trafficking Networks Can Hide in Plain Sight in Schools In the heart of American…

Native Family Vanished in 1963 — 39 Years Later A Construction Crew Dug Up A Rusted Oil Drum…

In the summer of 1963, a native family of five climbed into their Chevy sedan on a warm evening in…

5 Native Kids Vanished in 1963 — 46 Years Later A Chilling Discovery Beneath a Churchyard….

For nearly half a century, five native children were simply gone. No graves, no answers, just silence. In the autumn…

Two Native Brothers Vanished While Climbing Mount Hooker — 13 Years Later, This Was Found….

Two Native Brothers Vanished While Climbing Mount Hooker — 13 Years Later, This Was Found…. They vanished without a sound….

End of content

No more pages to load