A salvage diver scanning a remote lake finally discovered a legendary fire truck missing for 60 years.

But when he dragged the massive rig to shore and pried open the welded doors, what he found inside wasn’t human remains, but a shocking secret that silenced the entire town.

The drought that year didn’t just steal the water.

It exposed the bones of Blackwood Lake inch by painful inch, revealing secrets that the dark, tannin stained depths had swallowed nearly two generations ago.

For the residents of the decaying lumber town clinging to the precipitous cliffs of the northern shore, the receding water line was an economic disaster.

But for Rod Austin, it was a silent invitation.

a beckonin from the past that he had spent his entire adult life waiting for.

Rod stood on the aft deck of his salvage boat, the iron mule, a converted trawler that smelled perpetually of diesel, wet neoprene, and stale coffee.

He watched the digital readout of his sidescan sonar water falling down the screen in shades of amber and black.

He was 45 years old.

His face weathered by wind and salt.

His hands scarred from years of wrestling rusted metal out of unforgiven silt.

He wasn’t a treasure hunter and he wasn’t a hero.

He was a janitor of the deep, contracted to clear submerged logging hazards, massive old growth timber that had sunk during the log drives of the last century before the water levels dropped enough to turn them into hull ripping nuisances for the few recreational boers left.

But today, Rod wasn’t looking for timber.

He was run a grid pattern near the drop, a notorious section of the lake where the granite cliffs plunged vertically into the abyss.

It was here 60 years ago during the great storm of 1964 that the pride of the town had vanished.

“Come on,” Rod whispered, his eyes stinging from staring at the monitor for 6 hours straight.

“Talk to me.

” The sonar hummed, sending acoustic pings slicing through the cold water.

Most returns were soft mud, rotting wood, drifting vegetation.

But then, as the boat chugged slowly parallel to the cliff face, the screen glitching with a hard, violent return, a geometric anomaly.

Rod killed the throttle immediately, letting the iron mule drift in its own wake.

He reversed the scroll on the screen, freezing the image.

There, amidst the chaotic scatter of fallen rocks and century old logs, was a distinct rectangular shape.

It wasn’t a rock.

Nature didn’t make right angles like that.

It was sitting upright, partially buried in the silt shelf at a depth of 120 ft.

His heart hammered against his ribs, a sensation he hadn’t felt since his first deep wreck dive.

He measured the dimensions on the screen using the digital calipers.

28 ft long, 8 ft wide.

Engine 9.

He breathed the name tasting like ash in his mouth.

For the town of Blackwood, engine 9 was a tragedy.

For Rod, it was a curse.

His grandfather, Elias Austin, had been the fire chief in 1964 when the brand new state-of-the-art fire engine disappeared during a landslide while responding to a phantom call in the storm.

The town had needed someone to blame.

They couldn’t blame the rain, so they blamed the man who sent the crew out.

Elias had died a broken man labeled incompetent, whispered about in diners and grocery stores as a man who buried five good men in a watery grave.

The bodies were never recovered.

The truck was never found until now.

Rod didn’t call the sheriff immediately.

In a town like Blackwood, information was a currency.

And right now he was the only one holding the wallet.

He needed confirmation.

He needed to put eyes on it.

The preparation for a solo dive to 120 ft in cold fresh water was a ritual of survival.

Rod moved with practice efficiency, checking the seals on his dry suit, analyzing the gas mix in his twin tanks.

At this depth, nitrogen narcosis, the martini effect, could cloud a divers’s judgment, making them feel invincible just moments before they drowned.

He was diving on air, but he had a pony bottle of rich nitrox for the decompression stops.

He stepped off the back of the boat.

The cold water of the lake hidden his exposed cheeks like a physical slab.

He purged his buoyancy compensator and began his descent.

The world above, the sunlight, the sound of the wind in the pines, the smell of drought dust vanished.

He was entering the sepiaone twilight of the thermocline.

As he passed 50 ft, the temperature dropped from 60° to a bone chill in 38.

The light filtered out, turning everything into shades of bruised purple and black.

Rod switched on his primary canister light.

A lightsaber of H hallogen cutting through the particulate matter.

90 ft.

The bottom loomed a moonscape of gray silt and jagged rocks.

He checked his dive computer.

He had limited bottom time before he went into decompression penalties.

He finned hard, following the anchor line he dropped near the target coordinates.

And then out of the gloom, a face appeared.

It wasn’t a human face, but the grill of a beast.

The massive chrome radiator of a 1960s pumper truck loomed out of the darkness, standing like a sentinel in the mud.

Rod stopped, hovering neutrally, buoyant 10 ft away, his breath catching in his regulator.

It was eerie how intact it looked.

The red paint, preserved by the cold, low oxygen water, was covered in a thin layer of brown algae, but the gold leaf lettering on the door was still faintly visible under the slime.

Blackwood fired depth.

Rod swam closer, his movement slow and respectful.

This was a graveside.

Five men were supposed to be inside that cab.

He expected to see the shattered remains of the windshield, the crushed roof from the landslide that allegedly swept it off the road.

But as his light played over the cab, a frown creased his brow behind the mask.

The roof wasn’t crushed.

There were dents certainly, and the mirrors were sheared off, likely from the tumble down the cliff, but the structural integrity of the cab was remarkably sound.

He drifted to the driver’s side window.

It was intact, but he couldn’t see inside.

He wiped his gloved hand across the glass, clearing away decades of silt.

He expected to see a skeleton slumped over the wheel, or at least the floating debris of a firefighter’s turnout gear.

Instead, his light reflected back at him.

The glass was black, not from the darkness of the interior, but from something on the glass itself.

It looked like paint or perhaps a heavy accumulation of tar.

He tried the door handle.

It was seized, frozen by rust and time.

But as he looked closer at the seam where the door met the frame, he saw something that made his blood run cold, even in the freezing water.

a bead of weld.

Rough, hasty, but unmistakable.

Someone had welded the door shut.

His computer beeped, warning him of his approaching no decompression limit.

Rod backed away, his mind racing faster than his ascent rate allowed.

Landslides didn’t weld doors shut.

Storms didn’t paint windows black.

He ascended slowly, completing his safety stops in a state of suspended agitation.

When he finally broke the surface and spit his regulator out, the silence of the lake felt different.

It wasn’t peaceful anymore.

It was complicit.

By the time Rod motored back to the municipal dock, the sun was setting, casting long, bloody shadows across the water.

He tied up the iron mule and walked straight to the sheriff’s office, bypassing the curious glances of the fishermen who spent their days drinking beer on the pier.

Sheriff Tom Harrow was a man who looked like he had been carved out of the same granite as the cliffs, hard, gray, and immovable.

He and Rod had played high school football together, but the badge had put a wall between them that neither tried very hard to climb.

“You look like you’ve seen a ghost, Rod,” Harrow said, not looking up from his paperwork.

“The office smelled of floor wax and stale cigarette smoke.

” “I found it, Tom,” Rod said, standing in the doorway, water still dripping from his hair onto the lenolium.

I found engine 9.

Harrow’s pen stopped moving.

The silence in the room stretched thin.

He looked up, his eyes narrowing.

You’re sure? Positive.

It’s at the base of the drop, upright, intact.

Harrow sighed, a long, weary exhalation that seemed to deflate his massive shoulders.

Hell, the drought.

I figured this might happen eventually.

He rubbed his face with a calloused hand.

“We’ll have to notify the families, the Millers, the Kowalsskis.

It’s going to open a lot of old wounds, Rod.

It’s already open for me,” Rod said sharply.

“My grandfather’s name is on that truck.

” “I know,” Harrow said softly.

“I know.

There’s something else,” Rod said, stepping closer to the desk.

The doors, they’re welded shut, Tom, and the windows are blacked out.

Whatever happened down there, it wasn’t just a landslide.

Harrow stared at him, his expression hardening.

60 years underwater does strange things to metal, Rod.

Rust fuses things.

Silt coats glass.

I know what rust looks like, Rod countered.

And I know what a welding bead looks like.

Someone sealed that truck before it went in the water.

Before Harrow could respond, the heavy oak door of the office swung open.

Mayor Vance walked in.

Vance was a man who wore suits that were too expensive for Blackwood, a politician who treated the dying town like a stepping stone to the governor’s mansion.

His father had been on the town council in the 60s, a legacy Vance protected with a smile that never quite reached his eyes.

“I heard the iron mule came in hot,” Vance said, his voice smooth.

“Rumors are flying that you found something, Austin.

” “He found the fire truck,” Harrow said, his voice neutral.

Vance’s smile faltered for a fraction of a second, replaced by a look of sharp calculation.

Is that so? Well, that is momentous news.

Tragic, but momentous.

He walked over to the window, looking out at the darkening street.

We should be careful, gentlemen.

That site is a grave, a sacred resting place for our local heroes.

We can’t just go poking around and disturbing their peace.

It’s a vehicle recovery, Mayor, Rod said.

Not an archaeological dig.

Those families deserve to bury their dead.

And they will, Vance said, turning back.

But we need to do this right.

Permits, state historical society involvement, environmental impact studies.

The lake is fragile with the drought.

Rod felt the anger flare in his chest.

You mean you want to bury it in paperwork until the water rises again? I mean, Vance said, his voice dropping an octave.

That some things are better left alone, Mr.

Austin, for the good of the town.

Your grandfather’s legacy has suffered enough.

Do you really want to drag the truck up and remind everyone of his failure? It wasn’t his failure, Rod said, his voice low and dangerous.

And I’m going to prove it.

The next three days were a masterclass in bureaucratic obstruction.

Every permit Rod applied for was flagged for additional review.

The mayor’s office cited concerns about hazardous materials, fuel, and oil leaking from the wreck.

It was a stalling tactic and it was working.

Rod couldn’t dive, but he could dig.

He spent his days in the basement of the Blackwood Public Library, a subterranean archive of damp paper and microfich.

Sarah, the head librarian, was a woman of sharp intellect and infinite patience who had always harbored a crush on the solitude loving diver.

She found him surrounded by stacks of yellowed newspapers from November 1964.

“You’re looking for the purchase orders,” Sarah said, placing a steaming mug of coffee on the table next to him.

It wasn’t a question.

“I’m looking for anything that makes sense,” Rod muttered, rubbing his eyes.

The official story is that the truck was responding to a fire at the old logging camp, but there was no fire.

The log books from the ranger station showed no smoke reported.

Sarah pulled a chair out and sat opposite him.

I did some digging of my own after you told me about the find.

Look at this.

She slid a photocopy of an old ledger across the table.

What is it? Town council meeting minutes from October 1964, one month before the accident.

They voted to purchase engine 9.

It was the most expensive piece of equipment in the county.

Custombuilt V12 engine imported brass pumps.

It cost three times the annual budget of the town.

How did they afford it? Rod asked.

They didn’t, Sarah said, tapping the paper.

They took out a massive loan.

And here’s the kicker.

They insured it for double its value just 2 weeks before the storm.

Rod looked at the numbers.

It was a staggering amount of money for the time.

So if the truck disappears, the loan gets paid off and the town pockets a fortune in insurance money.

Sarah finished.

The town was bankrupt in ‘ 64, Rod.

The mill was closing.

They were desperate.

Desperate enough to kill five firemen, Rod asked, the horror of the implication settling in.

Or, Sarah whispered, “Desperate enough to make five firemen disappear.

” She pulled out another piece of paper.

“I found a redacted witness statement, an old woman who lived near the quarry.

She claimed she heard a heavy truck idling in near the old crusher the night of the storm.

That’s 5 mi from where the landslide happened.

She said she heard grinding sounds, like metal on metal.

Grinding, Rod repeated.

He thought of the welded doors.

They were modifying it.

Rod, Sarah said, reaching out to touch his hand.

If you bring that truck up, you’re not just clearing your grandfather’s name.

You’re indicting the founding fathers of this town.

Vance’s father was the council president.

“That explains why the mayor wants it left at the bottom,” Rod said, standing up.

“He knows.

” Rod returned to the marina that night, determined to dive the next morning, permit or no permit.

But as he walked down the dock, the smell of gasoline stopped him in his tracks.

He broke into a run.

The iron mule was listing slightly to the port side.

He jumped aboard, his boots slipping on the fuel sllicked deck.

The engine hatch was open.

He shown his flashlight into the bay.

It was a massacre of machinery.

The fuel lines to his main diesels had been slashed.

His compressor, the lifeline for his diving operations, had been smashed with a sledgehammer.

The casing cracked and the pistons destroyed.

“You got to be kidding me.

” Rod growled, his hands shaking with rage.

“Rough night!” Rod spun around, shining his light onto the dock.

“Ah, figure stood there, silhouetted against the street lights.

It wasn’t the mayor.

It was Miller.

” Miller was a giant of a man, usually seen wearing a high visibility yellow vest and a hard hat.

He ran the only heavy construction crew left in the county.

He had a reputation for being expensive, grumpy, and utterly honest.

“Did you see who did this?” Rod demanded, stepping off the boat.

“Saw a couple of kids running off an hour ago,” Miller rumbled, spitting a stream of tobacco juice into the water.

“But kids don’t carry sledgehammers.

This looks professional.

It’s Vance, Rod said.

He’s trying to stop me from raising the truck.

Miller looked at the ruined boat, then at Rod.

I heard about the weld marks, Rod.

Sheriff Harrow talks when he drinks, and he drinks at my brother’s bar.

It’s a crime scene, Miller.

Or a cover up.

Miller nodded slowly.

My uncle was on that truck.

Pete Miller, driver.

Rod paused.

He hadn’t known.

“I’m sorry.

Don’t be sorry,” Miller said, hitching up his belt.

“Be useful.

You can’t lift that thing with this tub anyway.

You need a crane.

You need a barge.

And you need someone who doesn’t give a damn about the mayor’s permits.

” “You have a barge?” “I have a barge,” Miller said.

“And I have a 50tonon crane.

I’ll meet you here at dawn.

We’re going fishing.

The next morning broke gray and cold.

A biting wind whipping the surface of Blackwood Lake into white caps.

The operation was technically illegal.

A vigilante recovery mission, but Sheriff Harrow was standing on the dock when Miller’s barge, the Goliath, chugged into position.

He wasn’t there to stop them.

He just watched, his arms crossed, his patrol car blocking the entrance to the marina to keep the mayor’s lackeyis away.

He had chosen his side.

The dive was going to be dangerous.

The storm had stirred up the bottom, reducing visibility to zero.

Rod would have to work by touch.

“We need to sling the axles!” Miller yelled over the roar of the crane’s diesel engine.

He was wearing his signature yellow vest.

Rain dripping from the brim of his hard hat.

The chassis is the only thing strong enough to take the weight.

If you hook the body, it’ll tear apart like wet cardboard.

Rod nodded, adjusting his mask.

I’ll dig tunnels under the wheels for the straps.

Give me slack on the cables until I signal.

Rod splashed into the water.

The descent was faster this time, driven by adrenaline.

He reached the bottom and swam to the truck.

It was a sleeping giant in the gloom.

The work was grueling.

Rod had to use a hand dredge to suck away the heavy clay and silt from around the massive tires.

The water was pitch black, thick with suspended mud.

He was blind, working entirely by feel.

He successfully slung the rear axle.

He moved to the front.

He was lying on his stomach in the mud, half under the front bumper of the massive truck, feeding the heavy nylon lifting strap through the suspension arms.

Suddenly, the truck groaned.

It was a sound conducted through the water, a deep metallic moan.

The dredging had destabilized the silt shelf the truck was resting on.

Topside, the load is shifting.

Rod screamed into his comm’s unit.

Get clear, Rod.

Get clear.

Miller’s voice crackled in his earpiece.

Before Rod could scramble backward, the front of the truck lurched downward.

The bumper slammed into the mud, missing Rod’s helmet by inches, but the sudden displacement of water and mud pinned his right leg.

A heavy timber dislodged from the cliff above by the vibration came tumbling down in slow motion and wedged itself against his tank valve.

Rod was trapped.

I’m pinned.

Rod gasped, fighting the rising panic.

Timber on my back.

Truck settled on the slope.

Breathe, Rod.

Miller’s voice was calm, anchoring him.

Don’t fight the suit.

How’s your air? 1,200 PSI.

I can’t move my leg.

We can’t pull the truck up with you under it.

Miller said, “If we lift now, it might slide and crush you completely.

” Rod closed his eyes.

He thought of his grandfather sitting on the porch, staring at the lake, dying of a broken heart.

He thought of the welded doors, the lie.

Miller, Rod said, his voice steadying.

Tension a rear line just a little.

Lift the back end.

It might pivot the weight off the front.

That’s risky, Rod.

If the chassis snaps, do it.

He felt the vibration of the cable tightening.

The truck groaned again.

Rod braced himself for the crushing weight.

Slowly, agonizingly, the pressure on the mud shifted.

The rear of the truck lifted inches.

The front bumper dug in, but the angle changed.

The timber on his back shifted.

Rod surged forward, kicking frantically with his free leg.

He tore himself loose from the muck, leaving a fin behind in the clay.

I’m clear, he yelled.

I’m clear.

Take it up.

Take the damn thing up.

Rod didn’t stop for decompression.

He shot to the surface, risking the bends fueled by pure survival instinct.

He broke the surface near the barge, gasping for air.

Miller hauled him onto the steel deck like a landed fish.

“You okay?” Miller asked, his face pale beneath the grime.

“Just lift it,” Rod coughed, staring at the water.

The crane engine roared, a mechanical beast screaming against the weight of history.

The thick steel cables hummed with tension.

The barge dipped low in the water.

She’s heavy, Miller shouted, working the levers.

Heavier than she should be if she’s full of water.

Slowly, the water began to churn.

Bubbles erupted from the depths.

Air pockets trapped for 60 years finally breaking free.

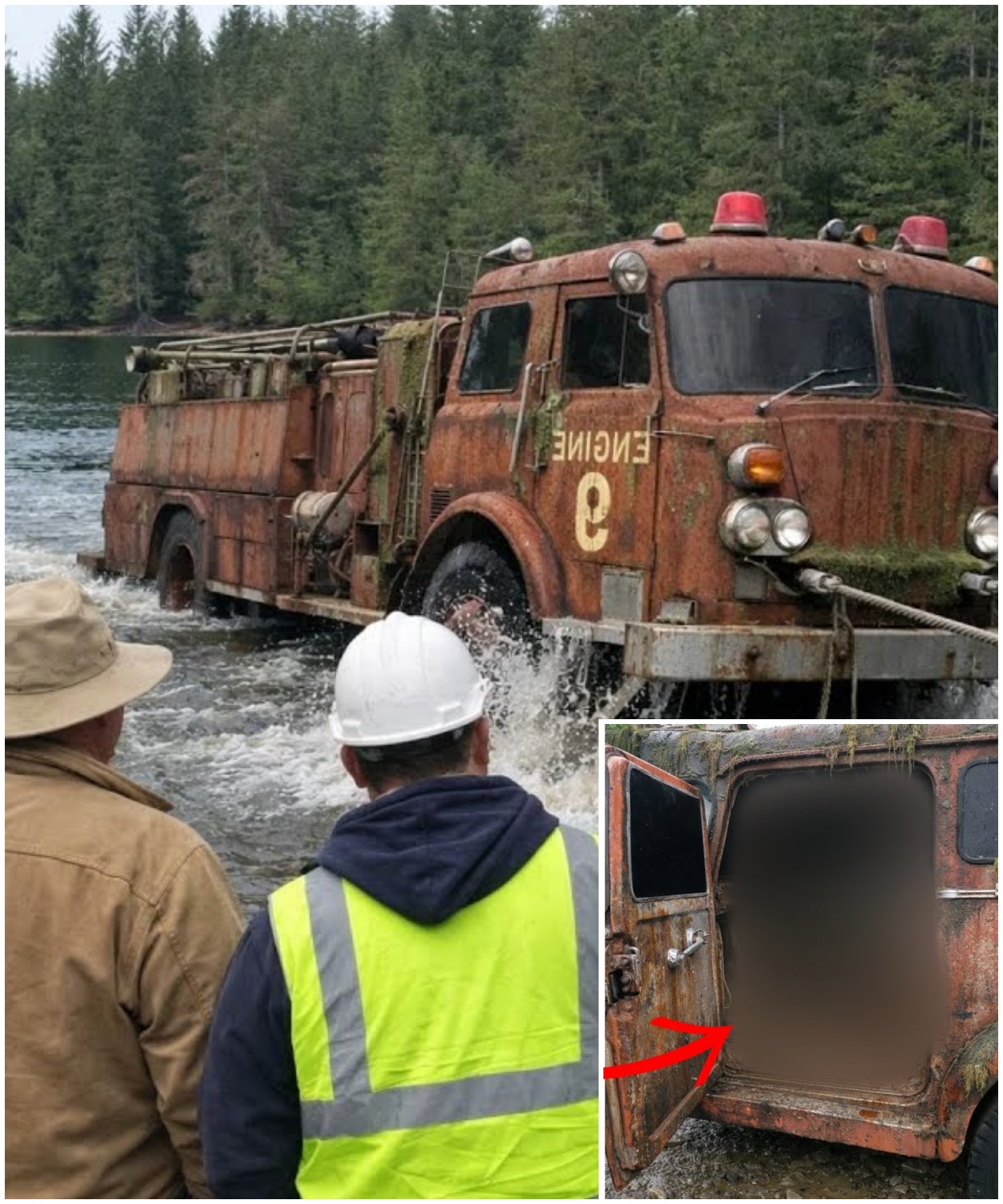

Then the nose appeared.

It was a shocking violent red against the gray water.

The radiator grill draped in weeds broke the surface, followed by the curved hood and the roof lights.

The crowd that had gathered on the shoreline.

Hundreds of people now, despite the mayor’s attempts to block the roads, went deadly silent.

The crane swung the massive dripping carcass toward the shore.

It hung in the air, water cascading from the wheel wells, a tragic pendulum.

Miller set it down gently on the gravel beach.

The suspension creaked, settling onto dry land for the first time in six decades.

Rod stripped off his gear and stumbled onto the beach.

He was shivering, not just from the cold.

Sheriff Harrow was there, Sarah was there, and Mayor Vance was there.

looking like a man watching his own execution.

“Stand back,” Harrow ordered the crowd, his hand resting on his service weapon.

“This is a crime scene.

” Rod walked up to the driver’s side door.

The weld marks he had seen underwater were obvious now.

Crude scars of molten metal sealing the fate of whatever was inside.

The windows were opaque with the black tar painted on the interior.

“Get the spreaders,” Rod said to Miller.

Miller ran to his truck and came back with a portable hydraulic rescue tool, the jaws of life.

He wedged the tips of the spreaders into the gap of the door frame.

“Ready?” Miller asked, looking at Rod.

“Open it.

” Miller triggered the hydraulics.

The machine whed.

The metal of the door groaned, resisting, then shrieked as the welds snapped one by one with the sound of gunshots.

The door popped open, swinging heavily on its rusted hinges.

A stench hit them.

Not the smell of decay, but the smell of stagnant water and old rubber.

Rod clicked on his flashlight and aimed it into the cab.

The crowd leaned in, holding its collective breath, expecting the gruesome sight of skeletons huddled together in their final moments.

Rod froze.

Harrow stepped up beside him, and the color drained from the sheriff’s face.

“My god!” Harrow whispered.

“What?” Someone in the crowd yelled.

“What is it?” Rod turned to look at the mayor, whose face was a mask of defeat.

Then he turned back to the truck.

“It’s empty,” Rod said, his voice carrying over the wind.

“The cab was gutted.

” It wasn’t just that there were no bodies.

There were no seats, no dashboard, no steering column.

Rod climbed onto the running board and shown the light through the firewall.

“The engine!” Rod shouted, looking at the crowd.

“It’s gone!” He jumped down and ran to the side of the truck, ripping open the equipment compartments.

They were empty.

No hoses, no axes, no breathing apparatus.

He scrambled underneath the chassis.

The transmission is gone.

The drive shaft is gone.

He stood up, covered in 60-year-old mud, and pointed a shaking finger at the truck.

It’s a shell, a hollow shell.

The realization rippled through the crowd.

This wasn’t a tragedy.

It was a prop.

Sarah stepped forward, holding the ledger she had copied.

“They stripped it,” she said, her voice trembling with rage.

“They bought the truck, insured it, and then stripped every piece of valuable machinery out of it.

The V12 engine, the brass pumps, the equipment.

They sold it all on the black market and then they welded the doors shut and painted the windows so no one would see it was empty when they pushed it into the lake.

Rod finished.

The crowd turned toward Mayor Vance.

The mayor held up his hands, backing away.

Now hold on.

That was 60 years ago.

I was a child.

You can’t blame me for the actions of the council back then.

You knew, Rod said, stepping closer.

That’s why you stalled the permits.

That’s why you tried to stop the dive.

You knew the town’s fortune and your family’s fortune was built on an insurance scam.

And the men, Miller asked, his voice a low growl, stepping toward Vance with the hydraulic spreaders still in his hand.

Where are the men? My uncle.

Where are they? Vance stammered, sweating despite the cold.

They They were paid off.

My father’s journals.

They were given a share of the sale.

They took new names, moved to the coast.

They didn’t die.

No one died.

It was a victimless crime to save the town.

Victimless.

Rod roared.

You destroyed my grandfather.

He spent his life thinking he sent those men to their deaths.

He died of shame.

You let this town mourn for 60 years over an empty box.

Sheriff Harrow stepped between Miller and the mayor.

He placed a hand on Vance’s chest.

Mayor Vance, I’m going to need you to come to the station.

We have a lot of old files to review.

You can’t arrest me for my father’s crimes, Vance shrieked.

No, Harrow said, pulling out his cuffs.

But I can arrest you for obstruction of justice, tampering with evidence, and vandalism of Rod’s boat.

I found the bolt cutters in your trunk, Vance.

You’re sloppy.

As the sheriff marched the mayor away, the tension on the beach broke.

The crowd looked at the rusted hollow truck, not with reverence, but with a strange mixture of anger and relief.

The ghosts were gone.

They had never been there.

Weeks later, the snow had begun to fall, covering the scars of the drought.

The town square of Blackwood Lake had a new monument.

The rusted shell of Engine 9 sat on a concrete plinth in the center of the park.

It hadn’t been restored.

It had been cleaned, stabilized, and sealed with a clear coat, freezing the rust and the damage in time.

Rod stood before it, his hand resting on the cold metal of the fender.

The plaque in front of the truck didn’t list the names of the fallen because there were none.

Instead, it read, “Engine 9, recovered November 2024, a testament to the truth.

” To the memory of Chief Elias Austin, a man of honor.

Miller walked up beside him holding two steaming coffees.

He was wearing a clean yellow vest.

Found out where my uncle went, Miller said, handing a cup to Rod.

California, opened a surf shop, died in 98.

Never told a soul.

At least he lived, Rod said.

That’s something.

Yeah, Miller grunted.

Better alive crook than a dead hero, I guess.

But I still like your grandfather better.

Rod smiled, taking a sip of the coffee.

He looked at the truck.

It was ugly, broken, and hollow.

But it was the most beautiful thing he had ever seen.

It was the end of the lie.

You going to keep diving? Miller asked.

Lake still low.

Nah, Rod said, turning away from the monument to look at the frozen lake in the distance.

I think I’m done with the past.

I hear the fishing’s good on the coast.

Take me with you, Miller said.

I’m sick of this snow.

The two men walked away, leaving the hollow engine to stand guard over the town.

A silent reminder that the truth, no matter how deep you bury it, always rises to the surface.

News

Brandon Frugal Finally Revealed What Forced Production to Halt in Season 7 of Skinwalker Ranch….

The Secret of Skinwalker Ranch became History Channel’s biggest hit. Six successful seasons documenting the unknown with real science and…

1 MINUTE AGO: What FBI Found In Hulk Hogan’s Mansion Will Leave You Shocked….

The FBI didn’t plan to walk into a media firestorm, but the moment agents stepped into Hulk Hogan’s Clearwater mansion,…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage… It started like any other evening…

Ant Anstead’s Final Days on Wheeler Dealers Were DARKER Than You Think

In early 2017, the automotive TV world was rocked by news that Ed China, the meticulous, soft-spoken mechanic who had…

What They Found in Paul Walker’s Garage After His Death SHOCKED Everyone…

What They Found in Paul Walker’s Garage After His Death SHOCKED Everyone… He was the face of speed on the…

What Salvage Divers Found Inside Sunken Nazi Germany Submarine Will Leave You Speechless

In 1991, a group of civilian divers stumbled upon something that didn’t make sense. A submarine resting where no submarine…

End of content

No more pages to load