On the night of January 14th, 1851, the temperature in Yazu County, Mississippi, dropped to 19° Fahrenheit.

It was the coldest night the region had experienced in over a decade.

The Yazu River, normally a slowmoving artery of brown water cutting through the cotton fields of the Delta, had begun to freeze along its edges.

Ice formed in thin sheets that cracked and groaned in the darkness.

On this night, a 13-year-old enslaved boy named Samuel stood at the edge of a ravine, staring down at a scene that would change his life forever.

Below him, half submerged in the freezing water, was a destroyed carriage.

The horses had already drowned, and trapped beneath the wreckage, bleeding from a gash on his forehead and screaming for help, was the man Samuel hated more than anyone else on Earth.

His name was Silas Crawford.

He was 47 years old.

He was one of the most successful slave traders in the Mississippi Delta.

And 3 years earlier, he had ripped Samuel’s mother from his arms and sold her to a buyer in Louisiana.

Samuel had dreamed of this moment.

He had imagined it a thousand times.

He had pictured himself standing over Crawford’s dying body, watching the life drain from his eyes, feeling the satisfaction of justice finally being served.

But now that the moment had arrived, Samuel felt something he did not expect.

He felt nothing.

Welcome to the channel, Stories of Slavery.

Today’s story takes us to 1859 and follows a black boy who did something no one could understand at first.

He saved the very man who sold his mother.

What happened next didn’t just surprise people.

It shocked everyone and revealed a truth that many tried to keep buried.

This is a difficult and intense story.

And in that emptiness, he heard his mother’s voice, the last words she ever spoke to him as Crawford’s men dragged her toward the iron wagon.

She had looked back at her son, tears streaming down her face.

And she had said seven words that Samuel would never forget.

Don’t let the hatred destroy you, son.

Samuel stood at the edge of that ravine for exactly 12 seconds.

He counted them and then he made a decision that defied every instinct in his body.

He climbed down into the freezing water and saved the life of the man who had destroyed his family.

This is the true story of what happened next.

To understand why Samuel made the choice he made, you need to understand where he came from.

And to understand that, you need to understand what life was like for enslaved people in Mississippi in the years leading up to the Civil War.

By 1851, Mississippi had become the fifth largest cotton producing state in America.

The entire economy of the region was built on the backs of enslaved black people who worked the fields from sunrise to sunset, 6 days a week, 52 weeks a year.

The port of Nachez, located on the Mississippi River near the Louisiana border, had become one of the largest slave trading centers in the entire South.

It was estimated that between 1830 and 1860, more than 1 million enslaved people were sold through markets in Nachez, New Orleans, and the surrounding areas.

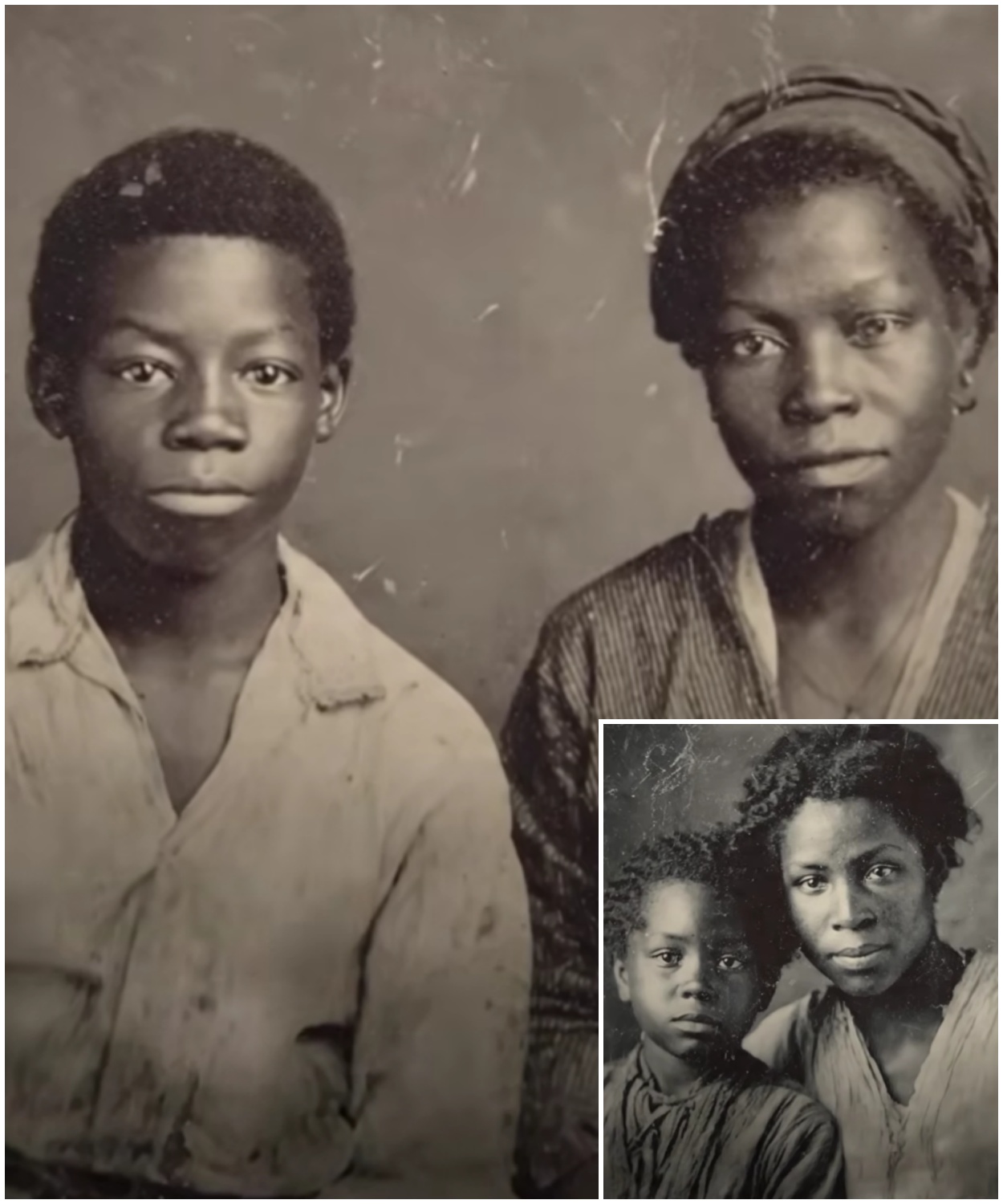

Samuel was born on the Blackwood plantation in Adams County, just 12 mi north of Nachez, in the spring of 1838.

His mother, Ruth, was 22 years old when she gave birth to him.

His father was a fieldand named Joseph, who had been sold to a plantation in Alabama when Samuel was just 2 years old.

Samuel had no memory of his father.

The only parent he ever knew was his mother.

Ruth worked in the kitchen of the main house.

She was known throughout Adams County as the finest cook in the region.

Plantation owners from as far away as Vixsburg would visit the Blackwood estate just to taste her food.

She could take the simplest ingredients and transform them into something extraordinary.

Cornmeal and pork fat became fluffy biscuits that melted on the tongue.

Tough cuts of meat became tender stews that warmed the soul.

Her pecan pie was so famous that Mrs.

Blackwood once entered it in a county fair under her own name and won first prize.

But Ruth’s skill in the kitchen was not the only thing that made her valuable to the Blackwood family.

She was also beautiful.

She had smooth dark skin, high cheekbones, and eyes that seemed to hold a quiet fire behind them.

And in the world of the antibbellum south, a beautiful enslaved woman was both an asset and a target.

The Blackwood family consisted of four people.

There was William Blackwood, the patriarch, a 63-year-old man who had inherited the plantation from his father and had spent his entire life growing cotton and accumulating wealth.

And who had inherited the plantation from his father and had spent his entire life growing cotton and accumulating wealth.

There was Margaret Blackwood, his wife, a stern woman from a prominent Virginia family who ran the household with an iron fist.

There was Elizabeth, their daughter, a quiet girl of 19 who spent most of her time reading novels and playing the piano.

And there was Thomas.

Thomas Blackwood was 24 years old in 1848, the year everything changed.

He was the only son, the heir to the entire Blackwood fortune, and he had grown up believing that the world existed to serve his desires.

He had been educated at the University of Virginia, where he had developed a taste for whiskey, gambling, and women.

He returned to Mississippi after his graduation with debts his father quietly paid and habits his father quietly ignored.

Thomas noticed Ruth the way a predator notices prey.

It started with small things.

He would find reasons to visit the kitchen when she was working alone.

He would stand too close to her when she served meals.

He would make comments about her appearance that made the other house servants uncomfortable.

Ruth knew what was happening.

She had seen it happen to other women on other plantations.

She knew that enslaved women had no legal right to refuse the advances of white men.

She knew that resistance often led to punishment, sale, or worse.

But Ruth was not like other women.

She had a spirit that could not be broken, and she had a son to protect.

On the night of September 7th, 1848, Thomas Blackwood came to the kitchen after midnight.

He had been drinking.

His breath smelled like bourbon, and his eyes had that glazed, hungry look that Ruth had learned to fear.

The other servants had gone to their quarters.

Samuel was asleep in the small room behind the pantry where he and his mother lived.

Thomas locked the kitchen door behind him.

What happened next was something Ruth never spoke about in detail.

But when Samuel woke to the sound of crashing pots and his mother’s screams, he ran into the kitchen to find Thomas Blackwood on the floor clutching his face, blood pouring between his fingers.

Ruth stood over him holding a cast iron skillet, her chest heaving, her eyes wild.

She had fought back.

In the world of the antibbellum south, this was an unforgivable crime.

An enslaved woman had struck a white man.

It did not matter that he had attacked her first.

It did not matter that she was defending herself.

The only thing that mattered was that the social order had been violated and order had to be restored.

Thomas Blackwood’s face was scarred for life.

The blow from the skillet had shattered his cheekbone and left a permanent indentation on the left side of his face.

He would never look the same again, and he would never forgive Ruth for what she had done.

William Blackwood faced a difficult decision.

If word got out that an enslaved woman had attacked his son and gone unpunished, it would undermine his authority and reputation throughout the county.

Other enslaved people might get ideas.

Other plantation owners might question his ability to control his property.

But Ruth was also extremely valuable.

Her skills in the kitchen were irreplaceable.

And if he simply had her whipped or killed, he would lose that value forever.

The solution came in the form of Silas Crawford.

Crawford was a professional slave trader who operated throughout the Mississippi Delta.

He was known for his efficiency, his discretion, and his willingness to handle difficult situations.

When a plantation owner needed to get rid of a troublesome enslaved person quickly and quietly, Crawford was the man they called.

He arrived at the Blackwood plantation on September 15th, 1848, 8 days after the incident in the kitchen.

He was a tall man with a weathered face and cold gray eyes that seemed to look right through people.

He wore a black coat and carried a leather satchel filled with documents and money.

He spoke in a low, measured voice that never rose above a conversational tone, even when he was conducting the most brutal transactions.

Samuel watched from behind the stable as Crawford examined his mother like she was livestock.

He watched as Crawford checked her teeth, squeezed her arms, and made notes in a small leather book.

He watched as Crawford counted out a stack of bills and handed them to William Blackwood.

And he watched as Crawford’s men put iron shackles on his mother’s wrists and ankles and led her toward a wagon with bars on the windows.

Ruth looked back at her son one last time.

Her eyes were filled with tears, but her voice was steady.

Don’t let the hatred destroy you, son.

Be bigger than them.

Promise me.

Samuel tried to run to her, but one of the overseers grabbed him and held him back.

He screamed until his throat was raw.

He fought until his body had no strength left, but it made no difference.

The wagon pulled away, and Ruth disappeared down the road toward Nachez.

Samuel never saw his mother again.

In the weeks and months that followed, Samuel changed.

The bright, curious boy who had once asked endless questions about the world became quiet and withdrawn.

He stopped speaking unless spoken to.

He stopped smiling altogether.

The other enslaved people on the plantation noticed the change.

They had seen it before in children who had been separated from their parents.

They called it the darkness.

because that was what it looked like.

A shadow that fell over a person’s soul and never lifted.

But there was something else happening inside Samuel that no one could see.

Behind his silent exterior, his mind was working constantly.

He was learning.

He was planning and he was waiting.

Samuel had one advantage that most enslaved children did not have.

because his mother had worked in the main house.

He had been exposed to things that Fieldhands never saw.

He had watched the Blackwood children receive their lessons from a private tutor.

He had observed how they learned to read and write, and in the quiet moments when no one was watching, he had taught himself to recognize letters and sound out words.

After Ruth was taken, Samuel became obsessed with improving his literacy.

He stole moments whenever he could.

He found a torn Bible that had been discarded behind the main house and hid it beneath a loose floorboard in the stable.

At night, when the other enslaved people were sleeping, he would light a small candle and practice reading by its flickering light.

He started with simple words.

God, man, love, hate, freedom.

Within a year, Samuel could read almost anything.

He could write well enough to copy letters and simple sentences.

He understood numbers and could perform basic calculations in his head.

None of the white people on the plantation knew any of this.

To them, he was just another enslaved boy.

Property to be used and discarded as needed.

But Samuel knew something they did not.

Knowledge was power.

and one day he would use that power to find his mother and to make Silas Crawford pay for what he had done.

The opportunity came on January 14th, 1851.

By this time, Samuel was 13 years old.

He had grown tall for his age, with strong shoulders from years of physical labor and those same quiet, watchful eyes that his mother had possessed.

He had been assigned to work in the stables, caring for the horses and maintaining the equipment.

It was relatively light work compared to the brutal conditions in the cotton fields.

But Samuel knew that his position was precarious.

Thomas Blackwood had never forgotten what Ruth had done to him, and he transferred his hatred to her son.

He looked for any excuse to have Samuel punished, and the overseers were always happy to oblige.

Samuel survived by being invisible.

He did his work perfectly.

He never spoke unless spoken to.

He never looked white people in the eye.

He became so unremarkable that most of the time the Blackwood family forgot he existed.

But Samuel had not been idle during those three years.

He had made connections.

He had learned things.

and he had become involved in something that would have gotten him killed if anyone had discovered it.

The Underground Railroad was a secret network of abolitionists, free black people, and sympathetic whites who helped enslaved people escape to freedom in the north.

It was not an actual railroad, of course.

It was a system of safe houses, hidden roots, and coded messages that allowed fugitives to travel from the deep south all the way to Canada, where slavery was illegal and American slave catchers had no authority.

In Mississippi, the Underground Railroad operated under constant threat of discovery.

The penalties for helping enslaved people escape were severe.

White abolitionists could face imprisonment or mob violence.

Free black people could be sold into slavery themselves, and enslaved people who were caught attempting to escape were subjected to punishments too brutal to describe.

Samuel had made contact with the Underground Railroad through a free black man named Isaiah, who worked as a blacksmith in Nachez.

Isaiah had been born into slavery in Virginia, but had purchased his own freedom 20 years earlier.

He had moved to Mississippi because the large population of enslaved people offered more opportunities to help others escape.

He operated in secret, using his blacksmith shop as a cover for his real work.

Isaiah had recognized something special in Samuel the first time they met.

The boy was intelligent, careful, and utterly determined.

Most importantly, he could read and write, skills that were invaluable for someone working in the Underground Railroad.

Isaiah began using Samuel as a messenger, sending him to deliver coded notes to contacts throughout Adams County.

On the night of January 14th, Samuel was returning from one such mission.

He had delivered a message to a contact near the Yazu River confirming that a family of four would be ready for transport the following week.

The night was brutally cold and Samuel was hurrying back to the Blackwood plantation before his absence was noticed.

That was when he heard the screams.

At first, Samuel thought it might be an animal.

Wolves were common in the forests along the Yazoo, and their howls could sound almost human on cold nights.

But as he drew closer to the sound, he realized it was definitely a man.

A man in terrible pain.

a man begging for help.

Samuel followed the sound to the edge of a ravine that dropped down to the river.

In the moonlight, he could see the wreckage of a carriage at the bottom.

The vehicle had apparently tried to cross a wooden bridge that had collapsed under its weight.

The horses were either dead or had been swept away by the current.

And trapped beneath the overturned carriage, half submerged in the freezing water, was a man.

Samuel climbed down the embankment carefully, using exposed roots and rocks as handholds.

As he got closer, he could see that the man was badly injured.

His leg was twisted at an unnatural angle, clearly broken.

There was a deep gash on his forehead that was bleeding heavily, and the cold water was slowly sapping whatever warmth remained in his body.

The man turned his head at the sound of Samuel’s approach.

His face was pale and contorted with pain.

But even in the darkness, even after 3 years, Samuel recognized him immediately.

It was Silus Crawford.

The slave trader’s eyes widened when he saw Samuel.

At first, there was hope in them, then confusion.

Then, as recognition dawned, something else.

Fear.

Please, Crawford gasped.

Please help me.

I’ll die out here.

Please.

Samuel stood absolutely still.

His heart was pounding so hard he could feel it in his throat.

His hands were trembling, but not from the cold.

Three years of grief and rage and hatred surged through him like a flood breaking through a dam.

This was the man who had taken his mother.

This was the man who had shackled her like an animal and sold her to strangers.

This was the man who had destroyed Samuel’s family and left him alone in a world of darkness.

And now that man was helpless, dying, completely at Samuel’s mercy.

Crawford seemed to read the thoughts on Samuel’s face, his eyes filled with tears that might have been genuine or might have been calculated.

With men like Crawford, it was impossible to know.

“I know who you are,” Crawford whispered.

You’re Ruth’s boy from the Blackwood place.

I remember.

Samuel said nothing.

He just stared.

I deserve this, Crawford continued.

His voice was weakening.

The cold was doing its work.

I deserve to die out here.

I know what I am.

I know what I’ve done, but please, please don’t let me die like this.

Samuel thought about his mother.

He thought about the last time he saw her, her wrists in shackles, her eyes filled with tears.

He thought about the three years of loneliness that followed, the endless nights of crying himself to sleep, the hollow ache in his chest that never went away.

He thought about how easy it would be to turn around and walk away.

No one would ever know.

Crawford would freeze to death within hours.

The wolves would scatter his bones.

Justice would be served.

But then he heard his mother’s voice as clearly as if she were standing beside him.

Don’t let the hatred destroy you, son.

Be bigger than them.

Samuel closed his eyes.

He took a deep breath and then he waded into the freezing water.

It took almost an hour to free Crawford from the wreckage.

The man’s leg was pinned beneath a section of the carriage frame, and Samuel had to use a broken piece of wood as a lever to lift it high enough to pull him out.

By the time he finally dragged Crawford onto the riverbank, Samuel’s entire body was numb from the cold, but he was not finished.

He could not leave Crawford here.

The man would freeze to death before mourning.

Samuel had to find shelter.

He remembered a hunting cabin about a/4 mile to the east.

It had been abandoned for years, but the roof was still intact, and there was a stone fireplace inside.

If he could get Crawford there, he might be able to keep him alive until morning.

Samuel was not sure why he was doing this.

Every logical part of his mind screamed that he should leave Crawford to die.

This man was his enemy.

This man had committed unspeakable crimes.

This man deserved whatever fate befell him.

But something deeper than logic was driving Samuel now.

Something that his mother had planted in him years ago.

Something that Crawford and the Blackwoods and the entire system of slavery had tried to destroy, but had never quite succeeded in killing his humanity.

Samuel grabbed Crawford under the arms and began to drag him through the forest.

The slave trader moaned in pain with every movement, but Samuel did not stop.

He could not stop.

If he stopped, they would both die.

The quarter mile to the cabin felt like a hundred.

Samuel’s arms burned.

His legs trembled.

His lungs achd from the freezing air, but he kept moving one step at a time, dragging the man who had destroyed his life toward safety.

When they finally reached the cabin, Samuel kicked open the door and pulled Crawford inside.

The interior was dark and dusty, filled with the debris of years of neglect, but the fireplace was clear, and there was dry wood stacked in the corner.

Samuel worked quickly.

He gathered the wood and arranged it in the fireplace.

He found flint and steel in an old tin box on the mantle.

Within minutes, he had a fire burning, its warmth slowly pushing back the deadly cold.

Crawford lay on the floor near the fire, drifting in and out of consciousness.

His leg was badly broken, possibly in multiple places.

The gash on his head had stopped bleeding, but it would need to be cleaned and bandaged to prevent infection.

He was still dangerously cold, and his breathing was shallow and labored.

Samuel found a pile of old blankets in the corner and covered Crawford with them.

He heated water in a dented pot he found near the fireplace and used it to clean the wound on Crawford’s head.

He tore strips from his own shirt and used them as bandages.

He did everything he could to keep the man alive.

And the entire time, a single question burned in his mind.

Why? Why was he doing this? Why was he saving the life of a man who had caused him so much pain? What possible reason could justify this act of mercy towards someone who deserved none? Samuel did not have an answer.

Not yet.

But as the night wore on and the fire crackled in the hearth and Crawford’s breathing slowly steadied, Samuel began to realize something.

He was not doing this for Crawford.

He was doing this for himself.

If he had left Crawford to die, he would have become something he did not want to be.

He would have let the hatred and the anger and the desire for revenge transform him into a monster.

He would have become like them.

And Samuel refused to become like them.

He would not let the system that had taken his mother also take his soul.

As dawn broke over the frozen forest, Crawford finally regained consciousness.

His eyes fluttered open, and for a long moment he simply stared at the ceiling of the cabin, trying to remember where he was and how he had gotten there.

Then his gaze fell on Samuel, sitting by the fire with his back against the wall, and everything came flooding back.

Crawford opened his mouth to speak, but no words came out.

What do you say to the person who saved your life when you were the one who destroyed theirs? Samuel spoke first.

You’re going to live, he said flatly.

Your leg is broken bad.

You won’t be able to walk for a long time, but you’ll live.

Crawford swallowed hard.

Why? He croked.

Why did you save me? Samuel was silent for a long moment.

Then he leaned forward, his eyes locking onto Crawford’s with an intensity that made the older man flinch.

Because you’re going to tell me where my mother is.

Crawford’s face went pale, paler than it already was from the cold and the blood loss.

I don’t I don’t know what you’re talking about.

Yes, you do, Samuel said quietly.

You sold her.

You took her from the Blackwood plantation in September of 1848, and you sold her.

I want to know where.

Crawford closed his eyes.

For a moment, Samuel thought he might pretend to lose consciousness again.

But then he sighed, a long shuddering sound that seemed to carry the weight of years.

“New Orleans,” he said.

“I sold her to a buyer in New Orleans.

At least that’s what I told the Blackwoods.

” Samuel felt his heart stop.

What do you mean that’s what you told them? Crawford opened his eyes and for the first time Samuel saw something in them that he had never expected to see.

Guilt.

I lied.

Crawford whispered.

I don’t know why.

I’ve sold hundreds of people, maybe thousands, and I never thought twice about any of them.

But your mother, there was something about her.

The way she looked at me, like she could see right through me, like she knew exactly what I was.

He paused, gathering his strength.

I was supposed to take her to the New Orleans market.

That’s where the Blackwoods thought she was going.

But at the last minute, I changed my mind.

I sold her to a man named Henri Dubois.

He has a plantation called Bell Reeve about 60 mi north of Baton Rouge.

He’s uh he’s different from most of them.

He doesn’t use the whip.

He feeds his people well.

He even lets some of them learn to read.

Samuel leaned forward.

You’re telling me my mother might still be alive.

Crawford nodded slowly.

If she’s anywhere, she’s there.

Bel Reeve.

Henri Dubois.

I don’t know why I did it.

I’ve never done anything like it before or since, but I did.

Samuel sat back against the wall, his mind racing.

His mother might be alive after 3 years of believing he would never see her again.

There was a chance, a real chance.

But he was not naive.

He knew that Crawford might be lying.

He knew that this could be a trick, a desperate attempt to gain his sympathy.

He knew that trusting this man could lead to disaster.

And yet something in Crawford’s voice told Samuel that he was telling the truth.

The guilt in his eyes was too real to be faked.

The shame in his voice was too deep to be manufactured.

For the first time in 3 years, Samuel felt something he had almost forgotten how to feel.

Hope.

But hope alone would not be enough.

Samuel needed more than information.

He needed leverage.

He needed power.

And as he sat in that abandoned cabin, watching the man who had taken his mother slowly regain his strength, Samuel began to formulate a plan.

A plan that would require patience, courage, and a willingness to do things that he had never imagined himself capable of doing.

a plan that would either reunite him with his mother or destroy him completely.

Samuel made his choice and nothing would ever be the same again.

The first three days in that abandoned cabin were the strangest of Samuel’s life.

He was trapped in a wooden box with the man who had destroyed his family.

Forced to care for him, forced to keep him alive, forced to sit across from him and listen to him breathe.

Crawford drifted in and out of consciousness during those early days.

His leg was badly broken, and without proper medical care, there was a real risk of infection.

Samuel did what he could.

With the limited resources available, he kept the wound clean.

He changed the bandages regularly.

He made sure Crawford stayed warm and hydrated, but Samuel was also planning.

He knew that he could not stay in this cabin forever.

Sooner or later, someone would notice his absence from the Blackwood plantation.

The overseers would come looking for him, and if they found him here with Crawford, questions would be asked.

Questions that could get Samuel killed.

He also knew that Crawford’s disappearance would eventually attract attention.

A man like that had business associates, clients, employees.

When he failed to return from his journey, people would start searching for him.

They would find the wreckage of his carriage.

They would follow the trail to this cabin.

Samuel had a narrow window of opportunity.

He needed to use it wisely.

On the fourth day, Crawford was finally strong enough to have a real conversation.

His fever had broken during the night, and although he was still weak, his mind was clear.

He watched Samuel move around the cabin with a mixture of weariness and something that might have been respect.

“You could have let me die,” Crawford said.

“It was not a question.

” Samuel paused in his work.

He was preparing a simple meal from supplies he had scavenged from the surrounding forest.

“Roots, berries, a rabbit he had managed to trap.

” Yes, Samuel said simply.

I could have.

Why didn’t you? Samuel did not answer immediately.

He finished preparing the food and brought a portion to Crawford, helping the injured man sit up against the wall so he could eat.

My mother told me something the day you took her.

Samuel finally said, “She told me not to let the hatred destroy me.

She told me to be bigger than the people who hurt me.

” Crawford looked down at the food in his hands.

His expression was unreadable.

“Your mother was a remarkable woman,” he said quietly.

“She still is,” Samuel replied.

“If what you told me is true,” Crawford met Samuel’s eyes.

“It’s true.

I swear it on my life.

Your life doesn’t mean much to me,” Samuel said flatly.

“But I believe you anyway.

I saw it in your face when you told me.

You were telling the truth.

” Crawford nodded slowly.

So, what happens now? You saved my life.

You know where your mother is.

What’s your plan? Samuel sat down across from Crawford, his back against the opposite wall.

The fire crackled between them, casting dancing shadows on the rough wooden walls.

“My plan,” Samuel said, is to make you help me get her back.

Crawford’s eyebrows rose.

help you? How exactly do you expect me to do that? You’re a slave trader, Samuel said.

You know how the system works.

You know the roots, the markets, the laws.

You know which officials can be bribed and which ones can’t.

You have connections that I could never have.

And you think I’m going to use all of that to help you free your mother?” Crawford let out a short, bitter laugh.

Boy, do you have any idea what you’re asking? Do you have any idea what would happen to me if I got caught helping an enslaved person escape? Yes, Samuel said calmly.

I know exactly what would happen.

You would be arrested.

You would be tried.

You would probably be hanged.

He leaned forward.

His eyes hard.

But that’s not the worst thing that could happen to you, Mister Crawford.

The worst thing is what happens if you don’t help me.

Crawford’s face tightened.

Is that a threat? Samuel reached into his coat and pulled out a folded piece of paper.

He had been working on it for the past 3 days, writing by fire light while Crawford slept.

This, Samuel said, is a letter.

It contains a detailed account of every crime you’ve committed in the past 10 years.

The slaves you’ve smuggled illegally.

The documents you’ve forged, the bribes you’ve paid to customs officials and sheriffs, the buyers you’ve cheated, the sellers you’ve defrauded.

Crawford’s face went pale.

How do you know about any of that? I listen, Samuel said simply, “I watch.

I remember.

You’d be amazed what people say in front of enslaved people.

They think we’re furniture.

They think we don’t understand, but we understand everything.

He held up the letter.

If I send this letter to the right people, your life is over, not just your career.

Your life.

There are men you’ve cheated who would pay good money to see you dead.

There are officials you’ve bribed who would do anything to keep their names out of the newspapers.

If this letter gets out, you won’t last a month.

Crawford stared at the letter like it was a coiled snake.

“You’re blackmailing me,” he said slowly.

“Yes,” Samuel replied.

“I am.

” A long silence stretched between them.

The fire popped and hissed outside.

The wind howled through the frozen trees.

Finally, Crawford let out a long breath.

Something in his expression changed.

The fear was still there, but it was mixed with something else now.

Something that almost looked like admiration.

You’re not what I expected, Crawford said.

When I saw you standing at the edge of that ravine, I thought you were just a scared little boy.

But you’re not, are you? You’re something else entirely.

I’m my mother’s son, Samuel said.

That’s all.

Crawford nodded slowly.

All right, you win.

I’ll help you.

But I need you to understand something.

What you’re asking me to do is incredibly dangerous.

Not just for me, for both of us.

If we get caught, they won’t just kill us.

They’ll make an example of us.

They’ll make sure that everyone knows what happens to people who defy the system.

I understand, Samuel said.

Do you do you really understand what you’re risking? You’re 13 years old.

You could have a long life ahead of you.

Even as a slave, you could survive.

You could find moments of happiness.

You could I could spend the rest of my life knowing that my mother is out there somewhere.

Samuel interrupted.

I could spend every day wondering if she’s alive or dead.

I could grow old without ever seeing her face again.

He shook his head.

That’s not a life.

That’s a slow death.

I’d rather take my chances.

Crawford studied the boy’s face for a long moment.

Then he nodded.

All right, he said.

Then let’s talk about how we’re going to do this.

The plan they developed over the next several days was audacious, dangerous, and completely insane.

It would require perfect timing, absolute secrecy, and a level of trust between two people who had every reason to hate each other.

But it was also brilliant.

The first step was getting Crawford back on his feet.

His leg was healing, but slowly.

Samuel fashioned a crude splint from tree branches and strips of cloth, immobilizing the limb so that the bones could knit properly.

He found a sturdy branch that Crawford could use as a crutch.

Within a week, the slave trader was able to move around the cabin on his own, though he still couldn’t put any weight on his injured leg.

The second step was establishing a cover story.

Crawford was well known throughout the region.

His disappearance had surely been noticed by now.

They needed an explanation for where he had been and what had happened to him.

Crawford came up with the story himself.

He would claim that his carriage had been attacked by bandits on the road to Nachez.

They had beaten him, robbed him, and left him for dead.

He had wandered through the forest for days before finally being discovered by a traveling minister who had nursed him back to health.

It was a plausible story.

Bandit attacks were common on the roads of Mississippi, especially during the winter months when desperate men were willing to take desperate risks.

And Crawford’s injuries were consistent with such an attack.

The broken leg, the gash on his head, the general state of exhaustion, it all fit.

The third step was the most dangerous.

Samuel had to return to the Blackwood plantation without being caught.

He had been gone for almost 2 weeks now.

There was no way to explain an absence that long.

If he simply walked back onto the plantation, he would be whipped at best, sold at worst.

He needed another approach.

Crawford suggested a solution that made Samuel’s stomach turn, but he had to admit it was clever.

“I’ll buy you,” Crawford said.

Samuel stared at him.

“What? I’ll go to the Blackwoods and tell them I want to buy you.

I’ll make up some story about needing a young boy to help with my business.

They’ll be happy to be rid of you.

Thomas Blackwood has always hated you.

He’ll probably give you away for free just to see the back of you.

” And then what? I become your property.

Crawford shrugged.

On paper, yes.

But papers can be lost.

Records can be destroyed.

Once you’re legally mine, I can take you anywhere without raising suspicion.

I can take you to Louisiana.

I can take you to Bel Reeve.

Samuel thought about it.

The idea of being sold again, of becoming the legal property of the man who had taken his mother, was almost unbearable.

But he also saw the logic in the plan.

As Crawford’s property, he would have freedom of movement that he could never have as a runaway.

He could travel openly, sleep in proper beds, eat proper food.

He could search for his mother without constantly looking over his shoulder.

All right, Samuel said finally, “Do it.

” It took another week for Crawford to recover enough to travel.

Samuel used that time to prepare.

He memorized the route to Bel Reeve.

He learned everything Crawford could tell him about Henri Dubois and his plantation.

He practiced the story they had concocted until he could recite it in his sleep.

On February 3rd, 1851, Crawford limped out of the abandoned cabin and made his way to the nearest town.

Samuel stayed behind, hiding in the forest, waiting for word that the plan had worked.

3 days later, Crawford returned with documents in his hand and a grim smile on his face.

“It’s done,” he said.

“You belong to me now.

” Thomas Blackwood was so eager to get rid of you that he practically gave you away.

He thinks you’re going to spend the rest of your life hauling cargo on the docks of New Orleans.

Samuel took the documents and looked at them.

There was his name written in neat script.

Samuel, no last name.

Enslaved people did not have last names.

Just Samuel.

Age 13.

Value $75.

$75.

That was what his life was worth in the eyes of the law.

Samuel folded the documents and tucked them into his coat.

When do we leave? He asked.

Tomorrow morning, Crawford replied.

We have a long journey ahead of us.

The journey from Yazu County to Baton Rouge was approximately 250 mi.

Under normal circumstances, it would take about a week by carriage, but circumstances were far from normal.

Crawford’s leg was still healing.

The winter weather was unpredictable, and they had to avoid drawing attention to themselves.

They traveled slowly, stopping frequently to rest.

Crawford posed as a businessman transporting his newly purchased slave to a client in Louisiana.

Samuel played his role perfectly, keeping his eyes down, speaking only when spoken to, displaying the subservient demeanor that was expected of enslaved people in the presence of whites.

But inside, Samuel was anything but subservient.

Inside, he was burning with anticipation.

Every mile brought him closer to his mother.

Every day increased the possibility that he would see her again.

They crossed into Louisiana on February 12th.

The landscape changed as they moved south.

The frozen forests of Mississippi gave way to swamps and bayus thick with cypress trees draped in Spanish moss.

The air grew warmer and more humid.

The smell of decay and growth mingled together in a scent that was unlike anything Samuel had ever experienced.

Crawford knew the roads well.

He had traveled them many times in his years as a slave trader.

He knew which ins were safe and which ones asked too many questions.

He knew which ferry crossings were monitored and which ones were not.

He guided them through the Louisiana wilderness with the expertise of a man who had made a career of moving human cargo from one place to another.

As they traveled, Crawford talked.

Perhaps it was the guilt that loosened his tongue.

Or perhaps it was simply the strange intimacy of their situation.

Whatever the reason, he began to share things with Samuel that he had never shared with anyone else.

He told Samuel about his childhood in Virginia, growing up on a small farm that could not compete with the large plantations around it.

He told him about his father, a bitter man who blamed everyone but himself for his failures.

He told him about the day he left home at 16, determined to make something of himself in a world that seemed designed to keep men like him down.

He told Samuel about his first job as an assistant to a slave trader in Richmond, how he had been horrified at first by the brutality of the business, how he had gradually become numb to it, how he had eventually embraced it as the only path to the wealth and status he craved.

He told Samuel about the hundreds, maybe thousands of people he had bought and sold over the years, men, women, children, families torn apart, lives destroyed.

He told him about the nightmares that sometimes woke him in the middle of the night.

The faces that haunted him, the screams that echoed in his memory.

“I know what I am,” Crawford said one night as they sat around a small fire in the Louisiana swamp.

“I know what I’ve done.

There’s no redemption for a man like me.

No forgiveness.

I’ve sold my soul a hundred times over, and there’s no buying it back.

” Samuel listened without comment.

He did not feel sympathy for Crawford.

He could not feel sympathy for a man who had caused so much suffering.

But he was beginning to understand something about the nature of evil.

Crawford was not a monster.

He was a man, a weak, broken, desperate man who had made terrible choices and was now living with the consequences.

He was proof that ordinary people were capable of extraordinary cruelty when the circumstances were right.

It was a lesson Samuel would never forget.

They reached the outskirts of Bell Reeve on February 18th, 1851.

The plantation was located on a bend in the Mississippi River about 60 mi north of Baton Rouge.

It was smaller than the Blackwood Plantation, but more prosperous.

The fields were wellmaintained.

The buildings were in good repair, and the enslaved people who worked the land appeared healthier and better fed than any Samuel had seen in Mississippi.

Crawford stopped the carriage at the edge of the property and turned to Samuel.

“This is as far as I go,” he said.

Henri Dubois knows me.

“If he sees me here, he’ll ask questions I can’t answer.

” Samuel nodded.

What do I do now? You wait until nightfall.

Then you make your way to the slave quarters and find your mother.

Once you found her, come back here.

I’ll be waiting.

Samuel looked at Crawford with suspicion.

How do I know you won’t just leave? Crawford sighed.

You don’t.

But think about it.

If I leave now, you still have that letter.

You can still destroy me.

My only chance of getting out of this alive is to help you succeed.

So, no, I won’t leave.

I’ll be right here when you get back.

Samuel considered this.

It made sense.

Crawford was many things, but he was not stupid.

He knew that his survival depended on Samuel’s goodwill.

All right, Samuel said, I’ll be back before dawn.

He slipped out of the carriage and disappeared into the gathering darkness.

The Bel Reeve slave quarters were located about a/4 mile from the main house, hidden behind a grove of oak trees.

There were 12 small cabins arranged in two neat rows, each one housing multiple families.

Unlike the cramped, dilapidated shacks of the Blackwood plantation, these cabins were solidly built with proper roofs and real floors and windows that could be opened to let in fresh air.

Samuel crept through the shadows, moving from tree to tree, staying out of sight.

He had no idea which cabin his mother might be in.

He had no way of knowing if she was even still here.

3 years was a long time.

Anything could have happened.

He waited until the plantation had gone quiet, until the last lights in the main house had been extinguished, and the only sounds were the chirping of crickets and the distant croaking of frogs.

Then he approached the nearest cabin and peered through the window.

Inside he could see a family sleeping on straw pallets.

A man, a woman, three children.

None of them was his mother.

He moved to the next cabin and the next and the next.

On the seventh cabin, Samuel found what he was looking for.

She was sitting by the fire alone, mending a torn piece of clothing by the flickering light.

Her hair had more gray in it than Samuel remembered, and there were new lines on her face that had not been there before.

But it was her.

It was definitely her.

His mother, Ruth, alive.

Samuel’s heart hammered in his chest.

His eyes filled with tears that he quickly blinked away.

He had imagined this moment so many times, but now that it was here, he did not know what to do.

Part of him wanted to burst through the door and throw his arms around her.

Part of him was terrified that if he moved, the vision would disappear and he would wake up back in Mississippi, alone and motherless.

He took a deep breath and knocked softly on the door.

Ruth looked up, startled.

She set aside her mending and rose to her feet, moving toward the door with the caution of someone who had learned to be wary of unexpected visitors in the night.

“Who’s there?” she called.

softly.

Samuel’s voice caught in his throat.

For a moment, he could not speak.

Then, with an effort that felt like lifting a mountain, he forced the words out.

“It’s me, mama.

It’s Samuel.

” “Silence!” A long, terrible silence that seemed to stretch on forever.

Then the door flew open and Ruth was standing there, her eyes wide, her hand pressed to her mouth, tears streaming down her face.

Samuel,” she whispered.

“My Samuel,” he nodded, unable to speak, unable to do anything but stand there and look at the woman he had thought he would never see again.

Ruth let out a sound that was half sobb, half laugh.

She grabbed Samuel and pulled him into her arms, holding him so tightly that he could barely breathe.

He could feel her body shaking with emotion.

could feel her tears soaking into his shoulder, could smell the familiar scent of her skin that he had never forgotten despite the years apart.

“My baby,” she kept saying over and over.

“My baby, my baby, my baby.

” They stood there for a long time, holding each other, crying together, making up for 3 years of separation in a single embrace.

When they finally pulled apart, Ruth cupped Samuel’s face in her hands and studied him with wonder.

“Look at you,” she said.

“You’ve grown so tall.

You’re almost a man now.

I came to find you, mama,” Samuel said.

“I came to take you home.

” Ruth’s expression flickered.

A shadow of fear crossed her face.

“Take me home? Samuel, what are you talking about? How did you even get here? How did you find me? Samuel told her everything.

He told her about the night he saved Crawford’s life, about the deal they had made, about the journey from Mississippi to Louisiana.

He told her about the letter he was holding over Crawford’s head, about the plan to escape together, about the route north that the Underground Railroad had prepared for them.

Ruth listened in silence, her eyes growing wider with each revelation.

When Samuel finished, she shook her head slowly.

“You did all this,” she said.

“You did all this for me.

I would have done anything for you, mama.

Anything.

” Ruth pulled him close again, holding him tightly.

“My brave boy,” she murmured.

“My brave, foolish, wonderful boy.

” They talked through the night, speaking softly so as not to wake the other people in the cabin.

Ruth told Samuel about her life at Bel Reeve, about the relatively humane conditions under Hri Dubois, about the small garden she had been allowed to cultivate and the friendship she had formed with the other enslaved people on the plantation.

But she also told him about the constant fear that never went away.

The knowledge that everything could change in an instant.

the understanding that no matter how kind Dubois might be, she was still property, still subject to his whims, still liable to be sold or punished or killed at any moment.

I’ve dreamed of freedom every single day since they took me from you, Ruth said.

But I never thought it could actually happen.

I never thought I would see you again.

It’s happening, mama.

Samuel said, “We’re leaving tonight.

Crawford is waiting for us at the edge of the property.

We’ll travel by night and hide by day.

We’ll follow the river north until we reach the contact points Isaiah told me about.

It will take weeks, maybe months, but we’ll make it.

I know we will.

Ruth looked at her son with a mixture of pride and fear.

You really believe that? You really believe we can escape? I believe we have to try, Samuel said.

I believe that if we don’t try, we’re already dead.

We’re just waiting for our bodies to catch up with our spirits.

Ruth was silent for a long moment.

Then she nodded slowly.

“You’re right,” she said.

“You’re absolutely right.

Let’s go.

” They gathered what few possessions Ruth had.

A change of clothes, a small knife, a piece of cornbread wrapped in cloth.

It was not much, but it was all she had.

As they slipped out of the cabin and made their way toward the edge of the property, Samuel felt a strange mixture of emotions.

Fear certainly, excitement, definitely, but also something else.

Something that took him a while to identify.

It was joy.

Pure unadulterated joy.

For the first time in 3 years, Samuel felt alive.

They found Crawford exactly where he had promised to be, waiting in the carriage at the edge of the property.

When he saw Ruth approaching with Samuel, something shifted in his expression.

Shame, perhaps regret.

It was hard to tell in the darkness.

Ruth stopped short when she recognized him.

“You,” she said.

Her voice was flat, cold, utterly devoid of emotion.

“Mrs.

Ruth Crawford said he could not meet her eyes.

I I don’t expect you to forgive me.

I don’t expect anything from you, but I want you to know that I’m going to do everything in my power to get you and your son to safety.

Ruth stared at him for a long moment.

Then she turned to Samuel.

You trust this man? No, Samuel said honestly.

But I trust that he knows what will happen to him if he betrays us.

and I trust that he wants to live.

” Ruth nodded slowly, “Then let’s go before I change my mind about not killing him myself.

” They climbed into the carriage and set off into the night.

The journey north was the most dangerous thing any of them had ever attempted.

They traveled by night and hid by day, moving through swamps and forests and back roads that only Crawford knew.

They avoided towns and villages whenever possible.

When they had to stop for supplies, Crawford would go alone, leaving Samuel and Ruth hidden in the wilderness.

There were close calls.

Once they nearly ran into a patrol of slave catchers near the Louisiana Mississippi border.

Another time, a suspicious inkeeper demanded to see Crawford’s papers, forcing them to flee in the middle of the night.

A third time, their carriage broke a wheel crossing a flooded creek, and they had to abandon it and continue on foot.

But they pressed on.

Mile by mile, day by day, they made their way north through Mississippi and Tennessee and Kentucky, through fields and forests and mountains, through rain and snow and bitter cold.

And as they traveled, something unexpected began to happen.

Crawford changed.

It was subtle at first, small things.

The way he shared his food without being asked, the way he kept watch at night so Samuel and Ruth could sleep.

The way he put himself between them and danger without hesitation.

But it went deeper than that.

Something inside Crawford was shifting.

The wall of cynicism and self-interest that he had built around himself over decades was beginning to crack.

Perhaps it was the daily presence of the people he had wronged.

Perhaps it was the knowledge that for the first time in his life he was doing something genuinely good.

Perhaps it was simply the power of witnessing a mother and son reunited after years of separation.

Whatever the reason, Silus Crawford was becoming a different man.

Not a good man, not yet.

Maybe not ever, but different.

They reached the Ohio River on March 15th, 1851.

The river marked the border between the slave states of the south and the free states of the north.

Once they crossed it, Ruth would legally be a free woman.

The slave catchers could still pursue them.

But they would have no legal authority to drag her back.

Crawford arranged passage on a ferry operated by a secret sympathizer of the Underground Railroad.

At midnight, under a moonless sky, they crossed the dark waters.

When they reached the opposite shore, Ruth stepped onto free soil for the first time in her life.

She stood there for a long moment, feeling the ground beneath her feet, breathing the air of freedom.

Then she fell to her knees and wept.

Samuel knelt beside her, holding her, crying with her.

They had made it.

After everything they had been through, after all the fear and danger and uncertainty, they had made it.

Crawford stood apart, watching them.

His face was unreadable in the darkness.

When Ruth finally rose to her feet, she walked over to Crawford and stood before him.

For a long moment, she simply looked at him.

Then she did something that shocked everyone, including herself.

She extended her hand.

I will never forgive you for what you did to me,” she said quietly.

“I will never forget the pain you caused, but I recognize that you have tried to make amends, and I thank you for helping to bring my son back to me.

” Crawford looked at her hand.

Then slowly, he reached out and took it.

“I don’t deserve your thanks,” he said.

I don’t deserve anything from you, but I give you my word that I will spend the rest of my life trying to undo the harm I’ve caused.

” Ruth nodded once.

Then she released his hand and turned away.

The journey was not over.

They still had to reach Canada where they would be truly safe from the slave catchers.

But the hardest part was behind them.

They were free.

They traveled for another 6 weeks, moving through Ohio and Pennsylvania and New York.

They were helped along the way by a network of abolitionists and free black communities who provided shelter, food, and guidance.

Finally, on April 28th, 1851, they crossed the border into Canada.

Ruth and Samuel settled in a small community near Toronto called Dawn Settlement.

It had been established specifically for fugitive slaves, and it offered something that neither of them had ever experienced before, a chance to build a life of their own.

Samuel enrolled in the settlement school, one of the few places in North America where black children could receive a proper education.

He discovered that he had a gift for learning.

And within two years, he was helping to teach younger students.

He studied history, mathematics, literature, science.

He devoured books with a hunger that could never be satisfied.

Ruth opened a small bakery using the culinary skills that had once made her the most valuable cook in Adams County, Mississippi.

Her peon pies became famous throughout the region, and her shop became a gathering place for the community.

They were not rich.

They were not powerful, but they were free, and that was everything.

Crawford did not come with them to Canada.

At the Ohio border, he had announced his intention to return to the south.

“There’s more I can do down there,” he said.

“More people I can help, more damage I can undo.

” Samuel was skeptical.

“You’re going to become an abolitionist, you of all people.

” Crawford smiled grimly.

I’m going to become whatever I need to become.

I have money.

I have connections.

I have knowledge of how the system works.

I can use all of that to undermine it from within.

They’ll kill you if they find out, Ruth said.

Probably, Crawford agreed.

But I’ve lived a long life, longer than I deserved.

If I can use whatever time I have left to do some good, then maybe I can die knowing that I wasn’t completely worthless.

He turned to Samuel and held out his hand.

“You saved my life,” he said.

“And in doing so, you showed me that it was possible to be better than I was.

I will never be able to repay that debt, but I will try.

Every day for the rest of my life, I will try.

” Samuel looked at the hand that had once signed his mother’s bill of sale.

Then he took it and shook it firmly.

“I believe you,” he said.

Don’t make me regret it.

Crawford nodded.

Then he climbed into his carriage and disappeared down the road.

They never saw him again.

Years later, Samuel would learn that Crawford had been true to his word.

He had returned to Mississippi and used his position as a slave trader to sabotage the very system he had once profited from.

He falsified records, allowing enslaved people to disappear from official registers.

He provided information to the Underground Railroad about patrol routes and safe passages.

He even purchased several enslaved people with his own money and quietly transported them to freedom.

He was caught in 1854.

A former business associate discovered what he was doing and reported him to the authorities.

Crawford was arrested, tried, and sentenced to hang for his crimes against the institution of slavery.

On the day of his execution, he reportedly said only one thing.

I was a monster, but a 13-year-old boy showed me how to be human.

That boy was more of a man than I ever was.

When Samuel heard the news of Crawford’s death, he did not know how to feel.

He did not mourn the man.

He could not mourn someone who had caused so much suffering.

But he also could not help feeling that Crawford’s death represented something significant.

It represented the possibility of change.

The possibility that even the worst among us can choose a different path.

The possibility that redemption, while never guaranteed and never complete, is always available to those who truly seek it.

Samuel became a teacher.

He spent the next 40 years educating black children in Canada.

and after the Civil War in the United States.

He traveled throughout the South establishing schools in communities that had never had access to education.

He trained other teachers, wrote textbooks, and advocated for equal educational opportunities for all children, regardless of race.

He never forgot where he came from.

He never forgot the horrors of slavery.

But he also never forgot the lesson he learned on that cold January night in 1851 when he stood at the edge of a ravine and chose mercy over revenge.

The greatest victory over your enemies, he would tell his students, is not to destroy them.

It is to become so strong, so wise, so free that their power over you simply dissolves.

Ruth lived to see the end of slavery.

She was there when the Emancipation Proclamation was signed in 1863.

She was there when the 13th Amendment was ratified in 1865.

She was there when her son returned to Mississippi for the first time since his escape, walking through the ruins of the Blackwood plantation as a free man.

She died peacefully in her sleep in 1871 at the age of 74.

Her last words were to Samuel, who sat at her bedside holding her hand.

You were bigger than all of them,” she whispered.

“Just like I always knew you would be.

” Samuel lived until 1903.

He was buried in a small cemetery in Mississippi, not far from the place where he was born.

His headstone bore a simple inscription that he had chosen himself.

I was my mother’s son.

That was enough.

This is the story of a boy who saved the man who destroyed his family.

It is a story about hatred and love, revenge and forgiveness, cruelty and compassion.

It is a story about the worst and the best of human nature, often existing in the same heart.

But most of all, it is a story about choice.

Samuel could have let Crawford die that night.

He would have been justified.

He would have been within his rights.

No one would have blamed him.

But he chose differently.

He chose to save a life instead of taking one.

He chose to build instead of destroy.

He chose to be bigger than the hatred that the world had poured into him.

And that choice made all the difference.

It gave him back his mother.

It gave him his freedom.

It gave him a life of purpose and meaning.

It even in a strange way gave Crawford a chance at redemption.

One choice, one moment of mercy, one decision to be better than the circumstances that created him.

That is the power we all have every single one of us, every single day.

The power to choose who we want to be.

Samuel chose well and his choice echoes through history, reminding us that even in the darkest times, even in the face of the greatest evil, the light of human being.

News

Ilhan Omar ‘PLANS TO FLEE’…. as FBI Questions $30 MILLION NET WORTH

So, while Bavino is cracking down in Minnesota, House Republicans turning the heat up on Ilhan Omar. They want to…

FBI & ICE Raid Walz & Mayor’s Properties In Minnesota LINKED To Somali Fentanyl Network

IC and the FBI move on Minnesota, touching the offices of Governor Tim Walls and the state’s biggest mayors as…

FBI RAIDS Massive LA Taxi Empire – You Won’t Believe What They Found Inside!

On a Tuesday morning, the dispatch radios in hundreds of Los Angeles taxi cabs suddenly stopped playing route assignments. Instead,…

Brandon Frugal Finally Revealed What Forced Production to Halt in Season 7 of Skinwalker Ranch….

The Secret of Skinwalker Ranch became History Channel’s biggest hit. Six successful seasons documenting the unknown with real science and…

1 MINUTE AGO: What FBI Found In Hulk Hogan’s Mansion Will Leave You Shocked….

The FBI didn’t plan to walk into a media firestorm, but the moment agents stepped into Hulk Hogan’s Clearwater mansion,…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage… It started like any other evening…

End of content

No more pages to load