The Federal Investigators report sat in a locked file cabinet in Washington for 43 years before anyone read it again.

Page one bore a single handwritten note.

Too disturbing for publication.

Recommend permanent seal.

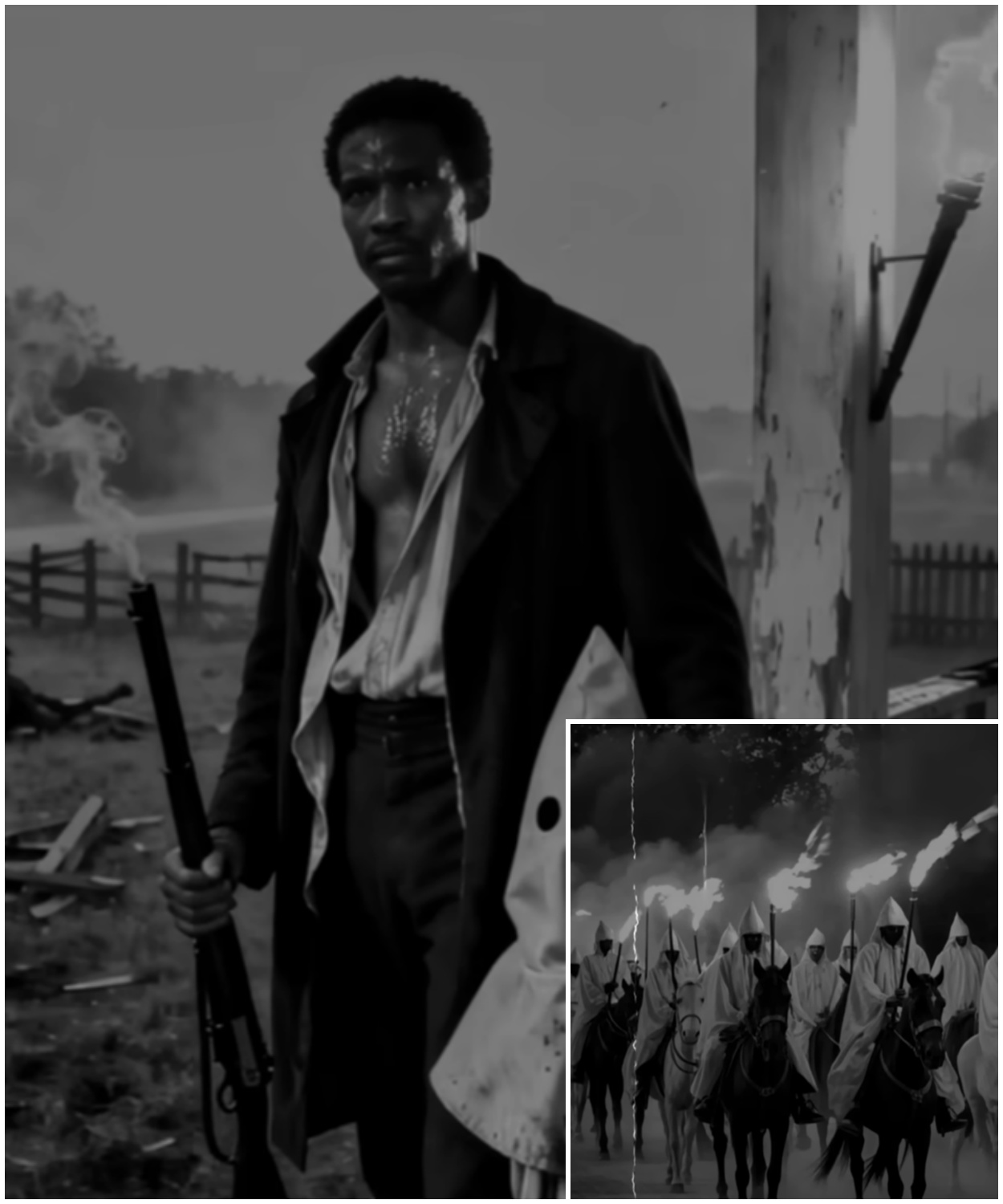

The document described what happened to 200 clan riders who rode into Covington County, Mississippi on the night of August 14th, 1873, and never came home.

Their horses returned riderless at dawn, some still saddled, others bearing saddle marks where leather had burned through.

The official explanation cited a violent storm, though weather records show clear skies that night.

What the sealed report actually documented was something else entirely.

A trap so methodical, so coldly executed that the agent who investigated it three months later wrote in his private diary, “I have seen battlefields.

I have walked through Andersonville after liberation, but nothing prepared me for the mathematics of vengeance laid out across those burned fields.

” This is the story of how one man turned a plantation into a killing ground and why the truth stayed buried until the people who remembered it were all dead.

Covington County, Mississippi in the summer of 1873 was cotton country.

Though the war had left the soil tired and the economy broken, the population was roughly split.

2,200 white residents, 1,800 black freed men, and a handful of Chinese laborers working the remaining plantations under contracts that resembled slavery in every way but name.

The county seat, Meridian’s Cross, sat 7 miles from the Alabama border, connected to the wider world by a single railroad line and roads that became impassible mud from November through March.

The clan chapter there called itself the Pale Riders and they had established what they termed order through systematic violence that local law enforcement not only tolerated but joined.

Sheriff Thomas Weimoth was a member.

So was Judge Horus Pelum who presided over the circuit court.

Reverend Calvin Straoud gave Sunday sermons praising white Christian civilization while wearing the same hands that had held torches Thursday nights.

They operated openly because they faced no opposition.

The federal troops who’d occupied the county immediately after the war had been withdrawn in 1871, part of the broader abandonment of reconstruction that left freed men communities defenseless.

The Pale Writers boasted that no black person had ever successfully defied their rules and lived.

The rules were simple and enforced with meticulous cruelty.

No meetings of more than five freedman without white supervision.

No learning to read or write.

No testimony against white citizens in court.

No ownership of firearms.

No walking on the same side of the street as white women.

No looking white men directly in the eye.

Violation meant punishment calibrated to send messages.

First offense, public whipping.

Second offense, burning of property.

Third offense, disappearance.

The system worked because it was predictable.

Freedmen who followed the rules could work, earn meager wages, and survive.

Those who challenged the order were eliminated with mechanical efficiency and everyone understood the cost of resistance was death.

But systems built on terror contain a fundamental weakness.

They require constant demonstration to maintain fear and eventually someone appears who refuses to demonstrate anything but calculation.

June 9th, 1873.

A woman named Clara Washington, 26 years old, formerly enslaved on the Bowmont plantation, opened a school in the abandoned smokehouse 3 miles outside Meridian’s Cross.

She had learned to read from a Quaker missionary in Tennessee and returned to Mississippi with six primers, a slate board, and a conviction that education was the only path forward.

19 children attended the first day, 23 the second.

By the end of the week, Clara was teaching reading to 37 children and 14 adults after dark.

The Pale Riders learned of the school within 5 days.

They came for Clara on June 17th at 2:00 in the morning.

Eight riders, white hoods, torches that turned the night orange.

They dragged her from the smokehouse while her students scattered into the pine woods.

What happened next was documented in enough testimony that the outlines are clear, even if the specific details remained contested for years.

Clara Washington was taken to a clearing half a mile into the forest.

The writers formed a circle.

They demanded she renounce teaching, burn her books, and publicly testify that educating black children was against God’s law.

She refused.

They beat her with fists and boots.

She refused again.

They hung her from a live oak branch for 30 seconds, then lowered her and repeated the demand.

She spat blood and said nothing.

At some point, witnesses disagreed on exactly when.

One of the riders removed a hunting knife from his belt.

Clara wore her hair in two long braids that reached her waist.

thick black hair she’d grown since emancipation, since the moment she’d been allowed to wear her hair however she chose, rather than cropped short under plantation rules.

The writer cut off both braids while she was still alive, sawing through the thick rope of hair while others held her still.

Then they killed her.

Manner of death, strangulation.

Time elapsed from capture to death.

approximately 40 minutes based on the statements of two children who watched from hiding and later testified to federal investigators.

The writers left Clara’s body hanging from the oak.

They took the braids back to Meridian’s Cross and nailed them to the door of the Freriedman’s Bureau office.

The small, underfunded federal agency that was supposed to protect black citizens, but had been reduced to a single administrator working out of a converted storoom.

Attached was a note written in careful script.

The wages of defiance, no more schools, no more reading, no more patience.

The braids stayed on that door for 3 days before anyone dared remove them.

Clara’s funeral was held at the African Methodist Episcopal Church on June 20th.

60 people attended, though state law limited black gatherings to 15 without white supervision.

No one stopped them because the pale writers wanted them gathered, wanted them afraid, wanted them to internalize the lesson.

This is what happens when you break our rules.

During the service, the church’s elder, a man named Solomon Reed, who’d been born into slavery 64 years earlier, stood and spoke words that would later be remembered as either prophecy or invitation.

There’s a man, Solomon said, his voice steady despite his age.

Union veteran, they call him Captain Jonas.

fought in Tennessee and Georgia, led impossible missions, and brought his men home.

Word is he’s in Jackson now, helping organize.

I heard he doesn’t ask for money, doesn’t promise victory, just promises he’ll come if you call him, and he makes them pay.

The congregation sat in silence.

Asking for help from a Union soldier meant admitting they couldn’t protect themselves.

It meant inviting more violence into their community.

It meant breaking the fundamental rule of survival in Mississippi.

Keep your head down.

Don’t make trouble.

Endure until things might change naturally someday through some undefined process that never seemed to actually arrive.

But Clara’s braids were still nailed to a door three blocks away.

Solomon Reed wrote a letter that night and sent it by railroad to Jackson the next morning.

Captain Jonas arrived in Meridian’s Cross on July 3rd, 1873 on the afternoon train from Jackson.

He was alone, carried a single leather bag, and wore civilian clothes, dark wool trousers, a white shirt, a black vest, and a widebrimmed hat that shadowed his face.

No uniform, no weapons visible, no entourage.

He was 34 years old, stood 5′ 11 in tall, and had a scar that ran from his left temple to his jawline.

The kind of scar that comes from a saber that should have killed you, but didn’t.

His real name wasn’t Jonas.

That was a name he’d taken after the war, after the thing he’d become during the war made his birth name feel like it belonged to someone who’ died.

Military records list him as Captain Elijah Thorne, 10th Regiment, United States Colored Troops, cited for valor at Fort Wagner, promoted to captain after leading a night raid that destroyed a Confederate supply depot and killed 23 soldiers without losing a single man.

The raid had been considered suicidal before he executed it.

Afterward, it became a template for asymmetric warfare that Union commanders studied.

But Jonas didn’t talk about his war record.

He talked about patience.

He met with Solomon Reed and six other community leaders in the church basement that evening.

No introductions were made beyond first names.

No one asked where Jonas came from or where he’d go next.

That was how he operated.

Solomon explained the situation, the Pale Riders, their rules, Clara’s murder, the certainty that the school’s closure was just the beginning of a broader campaign to reassert total control before any federal authority could return.

Jonas listened without interrupting.

When Solomon finished, Jonas asked a single question.

How many writers? chapters about 200 strong.

Solomon said they pull from three counties.

Not all of them ride every time, but when they want to make a statement, they can gather 200 men in a few hours.

Jonas nodded slowly.

And the plantation everyone says is haunted.

Where is it? The question surprised them.

Solomon exchanged glances with the others.

Thornwood Plantation, 6 miles north.

Been abandoned since ‘ 64.

Owners fled during Sherman’s march and never came back.

Freedman won’t go near it.

They say it’s cursed.

Why cursed? Bad things happened there during slavery.

Underground punishment cells, breeding programs, overseers who specialized in torture.

70 people died on that property that we know about.

probably more.

After the owners left, a few squatters tried to settle it.

Most left within weeks, said they heard screaming at night.

One family stayed, found dead six months later.

No marks on them, just dead in their beds.

After that, everyone avoided it.

The buildings still standing.

Main house, barn, six outuildings, all empty.

Jonas was quiet for a long moment.

Then he said something that became legend.

Let them come.

Solomon didn’t understand.

Come where? To the plantation.

Spread word that a black militia is gathering there.

Training, organizing, armed.

Make it sound like a threat they can’t ignore.

Make it sound like we’re preparing to burn Meridian’s cross and kill every white family in the county.

Make it sound like the thing they’ve feared since emancipation.

That we’d stop being afraid and start being angry.

That’ll bring them all down on us.

That’ll get people killed.

Yes, Jonas said it will.

Jonas spent the first week alone at Thornwood Plantation, and what he did there during those seven days became the foundation of everything that followed.

He walked every acre of the property which covered 340 acres of mixed forest and fields.

He studied sight lines, elevation changes, drainage patterns.

He identified every structure and its condition.

He cataloged resources, abandoned farming equipment, rotting lumber, intact doors and window frames, and old still barrels of aged tarpentine.

Most importantly, he mapped the plantation’s single access road and confirmed what local knowledge already suggested.

Only one way in, through a narrow lane bordered by drainage ditches and dense undergrowth.

Anyone approaching would be funneled into a predictable path and anyone trying to leave in a hurry would face the same choke point.

He measured distances and did arithmetic.

200 riders meant 200 horses.

Assuming they’d attack as a mass rather than splitting up, they’d need to spread across the property to surround buildings, cut off escape routes, and establish dominance.

That meant dispersing across roughly 30 acres of central grounds.

Math problem.

How do you trap 200 armed men in 30 acres when you’re alone? Answer: You don’t trap them.

You create conditions where they trap themselves.

July 10th.

Jonas posted a notice at three black churches requesting able-bodied men willing to work for wages.

No explanation of the work, no promises of safety, just $2 a day, paid at the end of each day.

No questions asked.

17 men showed up at Thornwood the next morning.

Jonas sent them to digging, not graves.

That would come later and naturally.

He had them dig trenches in specific patterns across the plantation grounds.

Shallow troughs about 6 in deep and 2 feet wide radiating from the main house in irregular lines that looked random but followed careful geometry.

The men didn’t understand the pattern and Jonas didn’t explain.

When they finished one section, he had them fill the trenches with hay, then cover the hay with dirt so the trenches disappeared.

While they dug, Jonas worked on the main house.

He reinforced certain floors and deliberately weakened others, sawing through support beams just enough that weight would collapse them.

He removed stairs from the interior, creating drops where people expected passage.

He blocked some windows and cleared others, creating obvious escape routes that led nowhere useful.

He also built gunpits, small depressions surrounding the plantation, camouflaged with brush, positioned at intervals that allowed overlapping fields of fire.

He didn’t arm them yet.

That would come later, but he built 23 firing positions arranged so that anyone in the plantation center would be within range of at least three shooters.

The work was methodical, repetitive, and done without conversation.

Jonas paid the workers at sunset each day and told them to tell no one what they’d built.

Some listened, others didn’t.

Within a week, rumors circulated through the black community that something was being prepared at Thornwood.

something involving trenches and collapsed floors and hidden positions that made no sense until you realized they weren’t defensive.

They were offensive.

A trap for anyone who thought they were the hunters, death ground.

That’s what soldiers called terrain where you couldn’t retreat, where the only option was forward or dying.

Jonas was building death ground for the Pale Riders, and he was using their confidence against them.

They’d come expecting frightened freedmen.

They’d find geometry.

July 16th, Solomon Reed began the next phase, though he didn’t think of it as theater.

He called a meeting of every black community leader in three counties, 57 people total, held at a farm 8 miles from Meridian’s Cross.

The gathering violated every rule the clan enforced.

It was large, organized, and held without white supervision.

It was designed to be noticed.

At the meeting, Solomon announced that a defensive militia was forming.

Captain Jonas, Union veteran, was training men in combat tactics.

They were gathering weapons.

They were preparing for armed resistance.

and anyone who wanted to join should come to Thornwood Plantation for instruction.

Everything Solomon said was technically true, though the details he omitted changed the meaning completely.

Three people at that meeting worked as informants for the Pale Riders, feeding information in exchange for reduced harassment.

All three reported the militia story immediately.

By July 18th, the clan leadership knew that somewhere between 50 and 100 black men were supposedly gathering at a cursed plantation, armed and organized, led by a Union officer.

The story grew with each retelling.

Some accounts claimed 200 militia men.

Others mentioned artillery and rifles shipped from the north.

A few reports included plans to attack Meridian’s cross and execute every white official in the county.

The clan couldn’t ignore it.

To do so would be to admit fear of black resistance would suggest that federal intervention might be coming.

Would imply that the rules they’d enforced through terror could be challenged.

The entire system depended on overwhelming any threat immediately and publicly.

73 clan members attended an emergency meeting at Reverend Straoud’s church on July 19th.

They debated how to respond.

Some argued for a smaller raid, 20 to 30 men to scout the plantation and assess the threat.

Sheriff Weimoth advocated for requesting federal troops to handle what he called an armed insurrection, which would have been the prudent move, but would have also meant admitting the clan couldn’t control the county without help.

Judge Pelum suggested an alternative.

Gather the entire chapter, plus allied riders from neighboring counties, ride an overwhelming force, and crush this militia before it could organize further.

We show them, Pelum said, that they can gather a hundred men and we’ll bring twice that number.

We show them that Union veterans and training and weapons don’t matter when we outnumber them two to one.

We make this spectacle big enough that it ends any thoughts of resistance for the next 20 years.

They voted.

Overwhelming force won.

Not just the Covington County chapter, but riders from Green, Kemper, and Wayne counties.

A coordinated display of power that would break the freed men’s morale completely.

They set the date for August 14th, selected for its symbolic weight.

Exactly one year since a federal judge in Jackson had ruled against the clan in a voting rights case that they’d ignored, but still resented.

200 riders, all armed, converging on Thornwood Plantation to annihilate what they believed was a gathering threat, but was actually one man, 17 laborers, and mathematics applied to terrain.

Not everyone in the white community supported what was coming, though opposition took forms that were more cowardice than courage.

Thomas Markham, a merchant who sold dry goods and owed his business to both white and black customers, heard the clan’s plans through gossip and tried to warn Solomon Reed.

He approached Solomon after church on July 27th, pulled him aside, and spoke in urgent whispers.

They’re coming for your militia, 200 men.

They’re planning something massive.

Solomon looked at Markham with an expression.

The merchant couldn’t read.

When? Mid August.

I don’t know the exact date, but soon.

You need to cancel whatever you’re planning.

Scatter.

Go north.

This can’t be won.

Solomon said nothing for several seconds, studying Markham’s face.

Then why are you telling me this? Because mass killing is different than keeping order.

Because Clara Washington didn’t deserve what happened to her.

Because I’ve done nothing to stop this for years, and I need to at least try once.

Then why don’t you go to the sheriff? Tell him to stop it.

Markham had no answer.

He stood there, his warnings delivered, his conscience partially satisfied, and walked away, still complicit in everything he’d enabled through years of silence.

Solomon watched him go and felt something close to pity.

Markham wanted credit for opposition without the cost of actual resistance.

What would you do in Markham’s position, knowing what was coming, having the influence to possibly stop it, but also having a family, a business, and a community that would destroy you for betraying white solidarity? The question isn’t hypothetical.

Hundreds of people like Markham existed across the South during reconstruction.

They knew they did nothing.

Then they spent the rest of their lives justifying their silence.

Solomon reported the conversation to Jonas that evening.

Jonas showed no reaction, just nodded and said, “Good means they’re committed.

” But there were other people who knew and did something far worse than nothing.

Reverend Straoud not only participated in planning the raid, he gave a sermon on August 10th that blessed it in advance.

He stood in his pulpit before a congregation that included clan members and their families.

And he preached from the book of Joshua about divinely sanctioned warfare against enemies of God’s chosen people.

When evil gathers, Straoud said, his voice carrying to the back pews.

When darkness organizes itself against the light, the righteous must answer with overwhelming force.

Joshua didn’t negotiate with the Canaanites.

He didn’t compromise.

He destroyed them utterly as the Lord commanded.

And we are called to the same righteousness.

Women nodded.

Children sat quietly, absorbing the lesson that violence in defense of white supremacy was sacred.

After the service, Strad blessed the horses that would carry riders to Thornwood.

He prayed over weapons.

He told young men that they were soldiers in a holy cause, and whatever they did on August 14th would be justified by the righteousness of their community’s survival.

The church was complicit.

The sheriff was complicit.

The judge was complicit.

The merchants who sold supplies and asked no questions were complicit.

The wives who packed food for their husband’s night rides were complicit.

The entire architecture of white Mississippi society was built to enable and justify exactly this kind of violence.

Jonas understood this.

He wasn’t fighting just 200 men.

He was fighting the system that produced them, equipped them, blessed them, and would cover for them afterward.

The only way to break such a system was to make the cost so high that protection became impossible.

August 1st through 13th, final preparations.

Jonas worked 16-hour days, sleeping only when exhaustion forced him.

The 17 laborers he’d hired were joined by 11 more volunteers.

Men who understood something terrible was coming and wanted to be part of whatever response Jonas was building.

Even if they didn’t fully understand what that response would be, Jonas gave them specific tasks and nothing more.

Six men spent 5 days hauling barrels of tarpentine from an abandoned still 3 m away.

They positioned the barrels at intervals along the hay-filled trenches Jonas had dug weeks earlier.

Other men collected fallen branches and arranged them in patterns around the plantation buildings.

Dry tinder that looked natural but was actually fuel.

Jonas himself worked on the gunpits, bringing in rifles salvaged from the war.

23 pits, each with two rifles positioned to fire from concealment.

Not new weapons, old Springfields and Nfields, battleworn, but functional.

He’d acquired them through contacts Solomon had helped establish, purchasing the rifles from freed men who’d kept them hidden since mustering out of Union service.

Each gun was loaded, capped, and ready.

He also built false positions, empty trenches that looked like they should hold shooters, but didn’t.

Decoy campfires laid with wood but never lit.

Bootprints leading to abandoned structures.

Everything designed to make attacking forces waste time and ammunition on empty threats while real threats remained hidden.

The main house received special attention.

Jonas removed all furniture and created a maze of reinforced corners where someone could take cover and fire through windows with overlapping fields.

He blocked the main staircase and created rope descents from second floor windows.

Anyone who entered the building expecting to find cowering militia members would instead find architectural violence.

Floors that gave way under weight, doorways that led to 12oot drops, windows positioned so anyone silhouetted in them would be visible to shooters outside.

On August the 12th, Jonas called all 28 workers together and explained what would happen.

Not what they hoped would happen.

What would happen? They’re coming in two days.

200 armed men who think they’re going to slaughter a defenseless militia and burn this place to the ground.

Instead, they’re riding into a trap designed to kill as many of them as possible with minimal risk to us.

He showed them the map he’d drawn, explained the fire trenches, the gunpits, the false positions, the exit strategy that would let workers evacuate before the riders arrived.

Then he said something that separated him from every other Union veteran who’d tried to protect freedman communities in Mississippi.

I’m not here to defend you.

I’m here to make them afraid.

When this is over, the Pale Riders won’t exist.

But that means every man who rides onto this property is going to die or wish he had.

That means we’re not capturing prisoners or showing mercy or accepting surrender.

That means you need to decide right now if you can live with what we’re about to do.

16 men stayed.

12 left.

The 16 who remained spent the final day checking positions, memorizing evacuation routes, and waiting for mathematics to play out in flesh and fire.

August 13th, 1873.

Sunset over Thornwood Plantation painted the sky rust and gold, colors that would look different in retrospect.

Jonas walked the property alone one final time, not checking preparations, but saying goodbye to whoever he’d been before the war and whoever he’d become during it.

Tomorrow would finalize the transformation.

In Meridian’s Cross, the Pale Riders gathered.

They came from four counties, converging at Reverend Straoud’s church throughout the afternoon and evening.

By 8:00, 194 men had assembled, slightly fewer than the full 200 anticipated, but more than enough.

They wore their robes and hoods, not to conceal identity.

Everyone in the county knew who they were, but to perform righteousness through uniformity.

White fabric transformed them from individual men with names and families into an instrument of collective will.

Sheriff Weimoth addressed them in the churchyard, standing on a wagon bed so everyone could see him.

His speech was preserved in testimony later given to federal investigators by one of the few riders who survived.

We ride at midnight.

We reach Thornwood by 1:00.

We surround the property on all sides so nothing escapes.

Then we burn every structure with anyone inside.

We hang the leaders.

We make this so complete, so terrible that no black person in Mississippi ever thinks about organized resistance again.

You are soldiers in a just cause.

You are protecting your families, your homes, your way of life.

God is with us tonight.

The writers checked weapons.

They formed into groups of 20 for easier coordination.

They mounted horses.

At 11:45, they departed Meridian’s Cross in a column that stretched nearly a quarter mile.

Torches lit, rifles loaded.

Some men sang hymns.

Others rode in silence, contemplating the violence they’d commit and justifying it with every step.

At Thornwood Plantation, Jonas waited with his 16 volunteers positioned in gunpits around the perimeter.

They had no torches, no lights.

They’d eaten cold food at sunset and hadn’t spoken for hours.

Jonas had given final instructions at dusk.

No one fires until the riders are fully committed inside the kill zone.

No one retreats until the signal.

No one hesitates when the moment comes.

Midnight passed.

The air was thick and still humidity that made every sound carry.

1:00.

Hoof beats in the distance.

The Pale Riders arrived at Thornwood Plantation at 12 minutes past 1:00 in the morning, August 14th.

They came expecting glory.

They found geometry.

The riders approached carefully, which was their first mistake.

Careful meant slow.

Slow meant time to spread out.

Spreading out meant dispersing into the exact pattern Jonas had designed the terrain to encourage.

Sheriff Weimoth ordered his men to surround the property, cutting off all escape routes before they charged the main house.

Standard tactics, reasonable caution.

But surrounding a 340 acre plantation with 194 riders meant spreading thin.

Each man responsible for covering roughly 40 yards of perimeter, too far apart to support each other, near enough to feel like they were still a coordinated force.

They positioned themselves along the treeine, watching the dark buildings, seeing nothing that contradicted their expectations.

An abandoned plantation, a few dim lights in windows, oil lamps burning low, no movement, no guards, no evidence of the massive militia they’d been warned about.

Weimoth sent scouts forward.

Five men dismounted and crept toward the main house.

Rifles raised, moving from cover to cover.

They reached the front porch without incident.

Checked windows, saw nothing.

One called back, “It’s empty.

Nothing here.

” The confusion rippled through the ranks.

Had the militia fled? Had the intelligence been wrong? Were they preparing an ambush from the woods beyond the plantation? We decided to take the main house to establish a command position, then sweep the outbuildings.

He ordered 40 men to dismount and enter the house while the rest maintained the perimeter.

The 40 men crossed the open ground between treeine and house.

Their torches lit them from below, making their shadows dance huge and distorted on the walls.

They reached the porch.

They entered through the main door and three ground floor windows.

They spread through the first floor, calling clear as they searched each room.

That’s when Jonas, positioned in a gunpit a 100 yards northwest of the house, fired the first shot.

Not at the riders.

At a barrel of tarpentine he’d positioned near the hay-filled trenches.

The bullet punched through the wood, and for a heartbeat, nothing happened.

Then flame found fuel.

The trenches ignited in sequence, fire racing along underground channels filled with hay and tarpentine, spreading faster than horses could run, creating lines of flame that divided the plantation into sections.

Riders who’d been spread along the perimeter suddenly found themselves separated from each other by walls of fire 8 ft high.

The flames illuminated everything, turning night into flickering orange day, destroying the cover of darkness the clan had relied on.

Inside the main house, the 40 men heard gunfire and shouting.

They rushed toward windows to see what was happening.

Jonas had positioned the gunpits specifically for this moment.

16 shooters opened fire simultaneously, targeting anyone silhouetted in windows or visible in doorways.

Muzzle flashes lit the darkness between flame lines.

Men dropped, hit by bullets before they understood they were under attack.

The riders outside the house panicked.

Some tried to reach their comrades inside.

Others fired blindly toward where they thought they’d seen muzzle flashes.

A few turned their horses to flee and discovered the access road was now blocked by fire.

The flames having raced down the trenches Jonas had built along the only exit.

They were trapped.

All 194 of them, separated into groups by fire barriers, unable to coordinate, unable to see who was shooting at them, unable to retreat.

Jonas had spent three weeks building this moment.

It took 6 minutes to spring the trap.

It would take 3 hours to resolve.

The men inside the main house tried to evacuate, which was their second mistake.

They rushed for doors and windows, clustering at exit points, creating targets.

Jonas’s shooters focused fire on these positions, not firing rapidly, but taking aimed shots at anyone who tried to leave.

Three men made it out the front door before bullets forced the others back inside.

Five tried to jump from second floor windows and fell through weakened floorboards into the cellar instead, breaking legs and ankles in 12t drops.

The house became a cage.

The 40 men inside were now pinned, taking fire from multiple directions whenever they exposed themselves.

Some tried to return fire, shooting from windows at gunpits they couldn’t see clearly.

Wasted ammunition.

Jonas’s positions were too well concealed, protected by earthworks and brush, firing from darkness into light.

Outside, the remaining 154 riders were divided into five groups by the fire barriers.

Each group tried to organize a response, but organization required communication, and communication required crossing flame lines or shouting over gunfire.

Some riders dismounted and tried to fight.

Others stayed mounted, horses panicking from fire and noise.

A few tried to jump their horses over the trenches, but the flames were too high and too wide.

Two horses attempted the jump.

both stumbled, throwing their riders into the fire.

Jonas had positioned his shooters to create crossfire zones.

Any rider trying to move between cover would be visible to at least two gunpits.

Any group trying to mass for a coordinated charge would bunch together, creating better targets.

The plantation’s layout funneled all movement into predictable paths, and every path was covered by rifles loaded and ready.

from federal investigators report October 1873.

The tactical sophistication displayed suggests formal military training and extensive planning.

The attacking force was numerically superior but strategically outmaneuvered from the moment they entered the property.

Subsequent examination of the terrain revealed a kill zone designed with geometric precision.

The shooting continued for 42 minutes.

Not constant fire.

Ammunition was limited, and Jonas had ordered his shooters to fire only when they had clear targets.

But 42 minutes of sporadic gunfire in darkness lit by burning trenches.

42 minutes of horses screaming and men shouting and bullets hitting flesh and wood and bone.

The clan riders had expected to be the aggressors.

Instead, they were targets.

Some riders broke.

Individual men or small groups decided survival meant fleeing regardless of the fire barrier.

They rode their horses directly into the flames, hoping speed would carry them through.

Some made it, emerging on the other side with burns, but alive.

Others didn’t.

Horses refused at the last second, throwing riders into fire.

or horses jumped and came down wrong, shattering legs, trapping riders beneath thrashing weight.

By 2:00 in the morning, the pale riders had lost tactical cohesion completely.

They were no longer an organized force, but clusters of frightened men trying to stay alive.

That’s when Jonas moved to the next phase.

Jonas left his gunpit and moved through the darkness beyond the fire zones, circling to the rear of the plantation where riders were trying to regroup.

He wasn’t alone.

Four of his volunteers accompanied him.

Men who’d lost family to the clan.

Men who’d watched friends disappear.

Men who’d swallowed rage for years and now had permission to spit it back.

They moved quietly through the woods, avoiding firelight, approaching the riders from directions they weren’t watching.

Jonas had explained this part carefully.

Target the leaders first, the ones giving orders, the ones keeping their men from complete collapse.

Remove command and the rest falls apart faster.

Sheriff Weimoth was trying to organize a withdrawal from the northeast corner of the plantation, gathering riders and forming them into a column that could charge through the flames together.

He’d gotten maybe 30 men assembled when Jonas emerged from the treeine behind them.

No warning, no challenge, just rifle fire that dropped Weimoth from his horse and scattered the men who’d been forming on him.

The riders fired back, but Jonas and his volunteers were already gone, melted back into darkness.

That was the horror of it.

The clan couldn’t see their enemies, couldn’t predict where the next attack would come from, couldn’t establish a defensive position because the entire plantation was hostile terrain.

15 minutes later on the southwest corner, Jonas found Judge Pelum directing six riders to make a coordinated charge at one of the gunpits, trying to silence it through direct assault.

Jonas waited until they were committed mid charge before firing from their flank.

Two riders went down, the others broke off the assault and scattered.

This wasn’t warfare.

It was hunting.

By 2:30 in the morning, the fire trenches were burning lower, fuel consumed, but the damage was done.

The plantation grounds were divided, visibility was chaos, and the clan’s numerical advantage had been neutralized by terrain and tactics.

Jonas continued moving through the darkness, appearing where riders least expected, firing, disappearing, reappearing elsewhere.

Always alone or with just two or three volunteers, always from unexpected angles.

The 40 men trapped inside the main house attempted a mass breakout at 2:45.

They charged out the front door together, betting that overwhelming one exit would let most of them escape.

Jonas had anticipated this.

He’d positioned three shooters specifically to cover the front entrance with overlapping fire.

The first five men through the door were shot.

The next wave stumbled over bodies.

The charge collapsed back inside the house.

Then Jonas did something that marked him as different from any other Union veteran operating in the South.

He set fire to the main house.

He’d positioned barrels of tarpentine at the building’s base during his preparation.

Now he shot those barrels from cover and flame climbed the wooden walls within seconds.

The men inside had a choice.

Burn or run the gunfire.

Most chose to run.

They came out windows and doors, some on fire, all panicked.

Jonas’s shooters fired into the mass.

Some riders made it to cover.

Others didn’t.

The house became an inferno.

Flames leaping 50 ft into the air, lighting the entire plantation like noon.

This is the part that made the federal report unpublishable.

Not the tactics, not the ambush, not even the kill count, which was horrifying enough.

What made the report too disturbing for public release was what happened after the house burned.

By 3:30 in the morning, the tactical portion of the engagement was over.

The surviving clan riders had either fled through the flames or were pinned in positions with no ability to fight back effectively.

Jonas could have let them leave, could have declared victory and withdrawn.

But he didn’t.

He hunted them.

For the next two hours, Jonas and his volunteers systematically moved through the plantation, finding riders who’d hidden in outbuildings or behind cover, forcing them into the open, shooting them or capturing them.

Not all of them.

Some escaped into the woods beyond the plantation boundaries.

fleeing wounded and terrified.

But Jonas found 37 men who’d thought they’d successfully hidden and were waiting for dawn to run.

He made them watch, made them see what their chapter had become.

Dragged them to the center of the grounds and forced them to sit in the firelight and look at the bodies scattered across the plantation.

Then he told them something that survivors repeated in testimony years later.

You came here to kill people who wanted to read.

You came here believing you were righteous.

You came here thinking black people would always be afraid.

You were wrong about everything.

Now go home and explain that you rode out with 200 men and came back with less than half.

Then he let them go.

37 clan riders, alive but broken, sent walking down the access road at dawn without horses or weapons, carrying the message back to Covington County, that the Pale Riders had been destroyed in a single night.

Dawn broke over Thornwood Plantation at 6:23 in the morning, August 14th, 1873.

The fire trenches had burned out.

The main house was a collapsed skeleton of charred timbers.

Bodies lay across the grounds in patterns that made clear this hadn’t been a battle, but an execution designed to look like one.

106 dead by the investigators later count, though exact numbers remain disputed because some bodies were never found.

Jonas and his volunteers left before full light.

They buried the rifles in locations marked only in memory, scattered the gunpit positions to make them look natural, and walked away separately.

Jonas himself disappeared into the network of freedman communities that stretched across the south, moving from town to town, never staying long enough to be documented, always available if called, but never seeking credit or recognition.

The 16 men who’d fought with him returned to their lives.

They told no one what they’d done.

When asked about the night at Thornwood, they said they’d been elsewhere.

And neighbors who knew the truth, backed up the lie.

Collective silence, the same tool the clan had used, now deployed against them.

Sheriff Weimoth’s body was found 3 days after the incident by federal investigators who arrived from Jackson on August 17th.

Judge Pelum survived, though he’d been shot in the leg and burned badly.

Reverend Strad fled Mississippi entirely and ended up in Arkansas, where he preached under a different name until someone recognized him and ran him out of that state, too.

The surviving clan members who made it home told fractured stories that contradicted each other in details, but agreed on fundamentals.

They’d ridden to Thornwood expecting a militia and found a slaughter house.

When pressed by federal agents on who’d organized the defense, they gave descriptions that didn’t match any known person.

A Union soldier, maybe 30, maybe 40, scar on his face, moved like smoke.

No name, no regiment, nothing that could be traced.

The official explanation that emerged from the chaos satisfied no one, but couldn’t be disproven.

The Meridian’s Cross Dispatch, the county’s only newspaper, published this on August 20th.

Tragic storm claims local riders.

A sudden and violent thunderstorm struck the abandoned Thornwood Plantation on the night of August 14th, catching a group of men sheltering from the weather.

Lightning started fires.

Structural collapses trapped victims.

Estimated losses exceed 100 souls.

County mourns its citizens.

Never mind that weather records showed clear skies.

Never mind that dozens of survivors told different stories.

Never mind the bullet wounds federal investigators documented.

The storm explanation gave the white community a way to avoid admitting what had actually happened.

That the clan had been systematically destroyed by organized black resistance.

The freed men communities didn’t need official explanations.

They knew what had happened, passed the story through networks the white community never accessed.

A Union veteran had come when called.

He’d built a trap.

He’d killed more than a hundred clan members in a single night.

The details grew in retelling, became legend, became myth.

Some versions claimed Jonas had supernatural powers.

Others said he’d had a hundred fighters, not 16.

A few said the plantation itself had fought alongside him, that the curse on Thornwood had awakened and chosen sides.

Federal investigator Martin Kessle arrived from Washington on September 3rd, tasked with documenting what had really occurred and determining whether charges should be filed.

He spent six weeks in Covington County interviewing survivors, examining the plantation ruins, collecting testimony.

His report ran to 347 pages, including sketches of the trap system Jonas had built and calculations of how 16 men with prepared positions could defeat a force of 200.

The report concluded with a recommendation that astonished his superiors.

No charges should be filed.

The men who died at Thornwood had been engaged in what Kessle termed organized terrorism against United States citizens, and their deaths represented justifiable defense of life and property.

He further recommended that the Pale Writers be designated a criminal organization and all surviving members be arrested for conspiracy to commit murder.

Neither recommendation was implemented.

Instead, Kessle’s report was classified, sealed, and buried in files that wouldn’t be opened for 43 years.

The Department of Justice determined that prosecuting the clan would inflame racial tensions, that pursuing Jonas would make him a martyr and that the best resolution was to let the incident fade into contested memory where no one’s version could be definitively proven.

which is how 106 deaths became a storm and justice became classified.

Thornwood Plantation was never rebuilt.

The ruins remained visible for decades, slowly consumed by vegetation and weather until nothing stood but foundation stones and twisted metal from the burned house.

The property reverted to the county for unpaid taxes in 1886 and was eventually parcled into farmland.

Though the central section where the main house had stood was never cultivated.

Farmers avoided it.

Said the soil was cursed, that nothing would grow right, that equipment broke in that section for no reason.

Clara Washington School reopened in September 1873.

Two months after she was murdered, Solomon Reed and three other community leaders pulled resources to hire a new teacher, a woman from Ohio named Margaret Hastings, who’d come south specifically because she’d heard about Clara.

40 students enrolled the first week.

The school operated for 16 years before Mississippi’s segregation laws forced it to close.

But in those 16 years, more than 300 fre learned to read and write.

The Pale Riders never reorganized.

A few clan chapters formed in neighboring counties during the 1880s and 90s, but Covington County remained quiet.

the terror infrastructure that had existed before August 14th, the open meetings, the blessing from church leadership, the collaboration between clan and law enforcement never reconstituted partly because so many leaders had died at Thornwood.

Partly because the survivors were afraid.

Fear.

That was what Jonas had accomplished.

He’d taken the weapon the clan used and turned it back on them.

For years, the Pale Riders had maintained power through the certainty that resistance would be crushed.

Jonas demonstrated the opposite.

That overwhelming force could be defeated by intelligence and preparation.

That terror wasn’t invincible.

That the people deemed powerless could become deadly given time and motivation.

But Jonas himself vanished.

No military records document his life after 1873.

No census lists him.

No grave bears his name, at least not under Jonas or Elijah Thorne.

Some historians believe he continued working with freedman communities throughout the South, appearing when called, never staying.

Others think he died anonymously within a few years, worn down by war and what he’d become during it.

A few suggest he went west, disappearing into territories where questions about the past went unasked.

What is known is that his name became a weapon in itself.

For decades, when clan chapters threatened black communities, someone would mention Jonas.

heard there’s a Union veteran coming.

Captain from the war.

They say he specializes in impossible situations.

Sometimes it was true.

Usually it was just the threat, just the memory of Thornwood, just the reminder that the men who seemed untouchable had once been touched.

Martin Kessle, the federal investigator, kept his personal diary separate from his official report.

In it, he wrote his unfiltered thoughts about what he documented at Thornwood.

The diary was donated to the National Archives in 1942 by his grandson, and one entry stands out.

October 21st, 1873.

I understand now why the clan members I interviewed seem more traumatized than the freed men who fought them.

The clan believed themselves to be apex predators.

Jonas showed them they were prey.

You can recover from physical wounds.

You cannot recover from the revelation that everything you believed about power and hierarchy was a lie.

The men who survived Thornwood will live with that knowledge until they die.

And it will poison every moment.

The file labeled too disturbing for publication was unsealed in 1916 when Congress investigated reconstruction era violence for a proposed civil rights bill that ultimately failed.

A historian named Elellanar Brash read Kessle’s report in 1958 while researching racial terrorism and called it the most thorough documentation of strategic resistance to white supremacist violence in the historical record.

The report was finally made public in 1973, exactly 100 years after the incident as part of broader declassification of reconstruction documents.

By then, everyone involved was long dead.

Survivors of the Pale Riders, freedmen who’d fought at Thornwood, federal investigators who documented it, all gone.

What remained was the story contested and complicated.

A reminder that justice in 1873 Mississippi came not from courts or federal troops, but from a Union veteran who understood that systems built on terror could be unmade by terror strategically applied.

Thornwood Plantation’s ruins are accessible today, though they’re overgrown and unmarked.

Local historians estimate that between 20 and 50 people visit annually, mostly researchers or descendants of Freriedman who lived in Covington County during reconstruction.

The land where the main house stood is still avoided by farmers, though soil tests show nothing unusual.

Some things persist beyond chemistry.

And on certain August nights, people living near the old plantation claim they hear sounds that might be wind through ruins or might be something else.

Hoof beatats, men shouting, the sharp crack of rifles firing in darkness.

Probably just wind.

Subscribe if you want the next deep dive.

News

At 91, Shirley MacLaine Finally Tells the Truth About Rob Reiner

At 91, Shirley MacLaine Finally Tells the Truth About Rob Reiner You expect the black sunglasses, the prepared statements issued…

Tracy Reiner REVEALS what Rob Reiner told her before he passed

You have to understand that when the cameras turn off and the red carpets are rolled away, Hollywood is a…

The Black Man Who Hunted the Ku Klux Klan

The rope burns told the story before anyone found the body. Isaac Woodard stood in the pre-dawn fog of a…

Clara of Natchez: Slave Who Poisoned the Entire Plantation Household at Supper

The crystal goblets caught candle light like captured fireflies, wine swirling crimson as 12 members of the Witmore family raised…

1890 Family Portrait Discovered — And Historians Recoil When They Enlarge the Mother’s Hand

This 1890 family portrait is discovered, and historians are startled when they enlarge the image of the mother’s hand. The…

(1859, Samuel Carter) The Black Boy So Intelligent That Science Could Not Explain

In the suffocating autumn of 1859, in the isolated village of Meow Creek, Louisiana, a 7-year-old black boy named Samuel…

End of content

No more pages to load