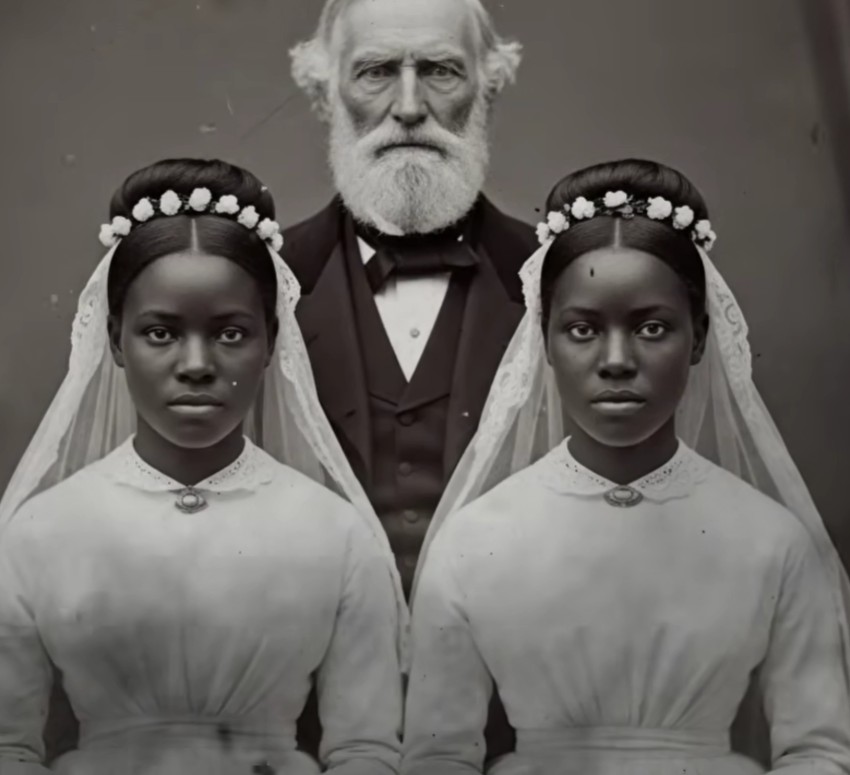

Today we’re going back to Mississippi 1857 to a wedding that was planned like a display of power.

A master arranging his own marriage to enslaved twins.

But just 10 hours later, something happened that no one could explain.

An inexplicable turn that spread fear, rumors, and silence across the plantation.

This is a difficult and intense story.

So, take a moment, breathe, and listen carefully.

On the night of June 14th, 1857 in Nachez, Mississippi, one of the wealthiest plantation owners in the entire South planned his own wedding ceremony.

He was 52 years old.

His brides were 19.

They were twins and he owned them.

What happened 10 hours after that ceremony would become one of the most whispered about events in the history of Adams County, but you will not find it in any official record.

You will not read about it in any textbook.

Because what those two young women did that night was so extraordinary, so meticulously planned, and so perfectly executed that the people who survived it decided the world could never know the truth.

This is the story they tried to bury.

This is the story of Ruth and Miriam.

The twins who waited 12 years for one single night.

To understand what happened in that mansion, you first need to understand where it happened.

Nachez, Mississippi in the 1850s was not just any southern town.

It was the epicenter of American wealth built on human suffering.

Before the Civil War, more millionaires lived in Natches than in New York City.

The reason was simple.

Cotton and the people forced to pick it.

The mansions that lined the bluffs overlooking the Mississippi River were monuments to an economy that ran on human trafficking, forced labor, and systematic brutality.

Historians estimate that by 1860, the enslaved population of Adams County outnumbered white residents by more than 3 to one.

This was not the gentile south of moonlight and magnolia that later generations would romanticize.

This was a place where human beings were bought and sold on the steps of banks, where families were torn apart as casually as one might sell a horse, where children learned from birth that their bodies belong to someone else.

Among the grand estates that dotted the landscape, Blackwood Plantation stood out for its size and its silence.

The property covered over 3,000 acres of prime cotton land stretching from the river bottoms to the pine forests that bordered the Homocito wilderness.

The main house was a Greek revival structure with 12 white columns and a reputation that made even hardened slave traders uncomfortable.

Its owner was Colonel Silas Blackwood.

He had inherited the plantation from his father in 1839 and had spent nearly two decades expanding it into one of the most profitable operations in the region.

By 1857, Blackwood Plantation held over 200 enslaved people and produced more than 800 bales of cotton per year.

On paper, Silas Blackwood was worth nearly $2 million.

In today’s terms, that would make him a billionaire.

But his wealth told only part of his story.

Silas Blackwood was not merely cruel.

Cruelty implies passion.

Some twisted emotional investment in the suffering of others.

Silas was something worse.

He was methodical.

He ran his plantation the way a machine runs a factory.

Punishment was calculated for maximum efficiency.

fear was distributed strategically to prevent any possibility of resistance.

He had studied the methods of other planters and refined them into a system that extracted the maximum amount of labor from human beings while keeping them just healthy enough to work.

He separated families not out of spite, but because he believed isolated individuals were easier to control than people with strong bonds.

He limited food rations not out of greed but because he had calculated the exact minimum calories required to maintain productivity.

He was in the language of his time a modern and scientific planter.

In the language of ours he was a monster who had found a way to bureaucratize evil.

In the spring of 1845 Silas Blackwood traveled to New Orleans for the annual slave auction at the St.

Louis Hotel.

This was the largest and most prestigious slave market in the south where wealthy planters gathered to purchase human beings as if they were selecting fine art.

The auction room featured a rotunda with a domed ceiling and marble floors.

Champagne was served.

Enslaved people were displayed on a raised platform, forced to walk, turn, and show their teeth while white men evaluated their worth.

On that particular March morning, Silas noticed something unusual.

Was a pair of young girls standing hand in hand.

They were clearly twins, perhaps 7 years old, with identical faces and eyes that held an expression no child should ever wear.

The expression of someone who has already seen the end of the world.

The auctioneer made a show of the twins.

Matched pairs were rare and commanded premium prices.

He announced that they had been captured from the Gold Coast of Africa from a region that is now Ghana.

He noted that they were healthy, dosile, and young enough to be trained for any kind of work.

The bidding started at $500 for the pair.

It quickly escalated.

Silas Blackwood won with a bid of $1,500, three times the average price for a single enslaved child.

When asked why he had paid so much, Silas reportedly smiled and said that twins were a sign of good fortune in his family.

His grandmother had been a twin.

He considered it an omen.

What he did not know, what he could not possibly have known was that he had just purchased his own death.

The girl’s names were not Ruth and Miriam.

Those were the names given to them later by the plantation’s house slaves who insisted that every person should have a name from the Bible.

Their original names, the ones whispered by their mother as she held them on the ship, were Adwa and Aqua, named for the days on which they were born according to Akan tradition.

Their grandmother had been an Okamo, a traditional healer and spiritual leader among the Ashanti people.

Before they were taken, before the raiders burned their village and marched the survivors to the coast, their grandmother had spent years teaching them everything she knew.

Which plants healed fever? Which roots eased pain? Which leaves could make a person sleep, and which flowers, prepared correctly, could stop a human heart.

This knowledge had been passed from mother to daughter for generations beyond counting.

It was knowledge that slavers and plantation owners never suspected existed.

Why would they? They believed the people they purchased were ignorant, primitive, barely human.

They never considered that among their captives were doctors and engineers, priests and poets, scientists who understood the natural world in ways European medicine would not discover for another century.

The journey from New Orleans to Nachez took 3 days by steamboat up the Mississippi River.

Ruth and Miriam, as they would come to be called, stood at the railing whenever they were allowed on deck, memorizing every bend in the river, every landmark, every possible route to freedom.

They did not speak to each other in front of the white crew members.

They had already learned that their ability to communicate in Twi, their native language, was their greatest secret weapon.

To the crew, they appeared to be terrified children clinging to each other for comfort.

In reality, they were conducting reconnaissance.

They were analyzing their situation.

They were already planning.

Blackwood Plantation was even worse than the New Orleans slave market had prepared them for.

At least in the city, there were crowds and noise and the occasional glimpse of free black people walking the streets.

Here there was only the endless cotton fields stretching to the horizon, the silent rows of slave cabins, and the big white house on the hill that seemed to watch everything like an allseeing eye.

Ruth and Miriam were assigned to the house staff, which meant they would work as domestic servants rather than field hands.

This was considered a privilege.

The work was less physically demanding, the food was better, and the accommodations were less crowded, but there was a cost.

House slaves lived under the constant gaze of the master and mistress.

There was no moment of privacy, no space for humanity, no relief from the performance of submission that was required every waking hour.

The girls learned quickly.

They learned to keep their eyes down and their voices soft.

They learned which floorboards creaked and which ones were silent.

They learned the rhythms of the house when the family rose and when they slept, who drank too much and who noticed everything.

They learned to read the moods of their capttors the way a sailor reads the weather, anticipating storms before they arrived.

And most importantly, they learned to hide.

Not physically, though they knew every concealed space in that mansion.

They learned to hide their intelligence, their anger, their memories, their very selves behind masks of compliance so complete that the people around them forgot they were people at all.

Silas Blackwood would later write in his journal that the twins were his most satisfactory purchase.

Requiring almost no discipline and performing their duties with mechanical precision, he mistook their survival strategy for acceptance.

He confused their patience with submission.

It was an error that would cost him everything.

The years passed.

Ruth was assigned to the kitchen where she learned to prepare elaborate meals for the Blackwood family and their many guests.

Miriam worked as a chambermaid, cleaning rooms and changing linens and becoming invisible in the way that servants were expected to be invisible.

Every night after the house was dark and their duties were done, they would meet in the small cabin they shared with three other enslaved women and they would whisper in twi, sharing everything they had observed, adding to the mental map they were building of the plantation and the region around it.

They learned that the Mississippi River was the main highway to the north and that some boats carried runaways hidden among the cargo.

They learned about the Homoito National Forest to the east where the swamps were so dense that dogs lost scents and search parties got lost.

They learned that Cairo, Illinois, where the Ohio River met the Mississippi, was considered the gateway to freedom because Illinois was a free state.

They filed away every piece of information like weapons in an armory waiting for the day they would need them.

Ruth became an expert in the plantation’s garden, learning to identify every plant that grew in the carefully maintained beds behind the kitchen.

Mrs.

Blackwood, Silus’s wife, fancied herself an amateur herbalist and kept an extensive collection of medicinal plants for treating minor ailments among the house staff.

What she did not know was that Ruth was quietly expanding her education beyond medicine.

The same garden that held chamomile and mint and lavender also boarded the woods where water hemlock grew wild along the creek banks.

Water hemlock known to scientists as chikuta maculata is considered the most toxic plant native to North America.

A single root can kill a full-grown man within hours.

The poison attacks the nervous system causing violent convulsions before shutting down the heart and lungs.

Ruth learned to identify it by its distinctive purple stre stem and its clusters of small white flowers.

She learned when it was most potent in early summer and how to extract its toxin by crushing the roots and filtering the liquid.

She told no one except Miriam, and she never harvested it.

Not yet.

The time was not right.

In 1853, everything changed.

Mrs.

Blackwood died of yellow fever during an epidemic that swept through the Mississippi Valley.

Silas mourned her publicly for exactly 6 weeks, the socially acceptable minimum, and then began a new phase of his life that would eventually lead to his destruction.

Without his wife’s presence to provide even the thin veneer of respectability, Silas’s appetites became more visible.

He began visiting the slave quarters at night.

He began demanding that certain enslaved women be assigned to the house permanently.

He began hosting parties for his friends that the house servants whispered about in tones of horror.

Ruth and Miriam watched all of this with careful attention, filing it away with everything else they knew.

They understood that eventually his attention would turn to them.

They had known it since the day he purchased them.

Since they saw the way he looked at them when he thought no one was watching.

They had been preparing for that day for 8 years.

They just didn’t know when it would come.

It came in the spring of 1857.

Ruth and Miriam were now 19 years old.

They had survived 12 years in captivity.

They had mastered every skill expected of house slaves and many that no one expected.

They could read and write, taught secretly by an elderly enslaved man named Solomon, who had been educated before his capture.

They could calculate numbers in their heads faster than the plantation’s white overseer could with pen and paper.

They knew the names and habits of every white family within 20 m, information gathered from conversations over her during dinner parties, and they knew every inch of the land between Blackwood Plantation and the river, from years of accompanying Mrs.

Blackwood on her botanical expeditions.

They were, in every way that mattered, ready.

They just needed the right moment.

That moment arrived on a June morning when Silas Blackwood summoned them to his study.

He was sitting behind his mahogany desk, dressed in his finest clothes, holding a glass of bourbon, even though it was barely 10 in the morning.

He looked at them with an expression they had never seen before, a kind of hungry satisfaction, like a man about to sit down to a feast.

He told them that he had decided to take a new wife, two wives, actually.

He had decided that southern tradition was too restrictive, too bound by outdated conventions.

He was a powerful man.

He could do as he pleased, and it pleased him to marry the twins.

He would hold a ceremony on Saturday.

It would not be legal, of course, since enslaved people could not legally marry anyone, least of all their masters, but it would be public.

He would invite all the most important families in the county.

He would dress them in white gowns.

He would put rings on their fingers and then they would belong to him in every way that a human being could belong to another.

He smiled when he said this.

He expected gratitude.

Ruth and Miriam stood perfectly still, their faces showing nothing.

They had learned long ago to never let their captives see what they were thinking.

Ruth spoke first.

She said that they were honored by his attention and they would strive to be worthy of his kindness.

Miriam added that they would need time to prepare themselves and requested permission to have new dresses made for the occasion.

Silas laughed with pleasure at their apparent acceptance.

He told them they could have whatever they needed.

He wanted this to be a celebration worthy of his status.

He dismissed them with a wave of his hand.

As they left his study, walking with slow, measured steps through the hallway and down the back stairs to the kitchen, neither of them spoke.

They didn’t need to.

After 12 years, they could communicate without words, and both of them were thinking the same thing.

Saturday, 4 days.

It was finally time.

That night, they held a council of war in their cabin.

They spoke in twi using words that had not been heard by white ears in all their years of captivity.

They laid out everything they knew and everything they needed to do.

The ceremony would be held in the evening, which meant darkness would come during the celebration.

The most prominent families in the county would be present, which meant all attention would be on the main house.

The household staff would be exhausted from preparation, which meant fewer people watching the slave quarters.

The summer heat would mean windows left open and guards drowsy at their posts.

Every factor favored them.

It was as if fate itself had aligned to give them this one chance.

But they couldn’t do it alone.

For their plan to work, they needed help from someone who knew the land even better than they did.

someone with access to transportation, someone with nothing left to lose.

His name was Ezekiel.

He was 43 years old and had been the head coachman at Blackwood Plantation for 15 years.

He was trusted to drive Silas to town, to transport goods to market, to carry messages to other plantations.

This trust had given him freedom of movement that few enslaved people ever experienced.

It had also given him knowledge of every road, every backpath, every hidden route between Nachez and the river.

What Silas did not know was that Ezekiel had spent years using this knowledge to help others escape.

He had guided at least a dozen runaways to safe houses along the Underground Railroad, risking his life each time because he believed that every person who reached freedom was a victory against the system that had stolen his own family.

His wife had been sold to a plantation in Louisiana 8 years ago.

His three children had been sold separately to three different owners across the South.

He did not know if any of them were still alive.

He had nothing left except his skills and his burning hatred for everything Silas Blackwood represented.

Ruth approached him on the second night while he was caring for the horses in the stable.

She spoke quickly and directly, wasting no time on pleasantries.

She told him what Silas planned to do on Saturday.

She told him what she and Miriam planned to do in response.

She told him they needed a driver who could get them to the river in the dark without being caught.

She asked him if he was willing to risk death for a chance at vengeance and freedom.

Ezekiel did not hesitate.

He had been waiting for someone brave enough to fight back for years.

He asked only one question.

Would Silas suffer? Ruth looked him directly in the eyes, something enslaved people were forbidden to do with anyone.

And she told him that Silas Blackwood would know exactly what was happening to him.

He would feel everything, and the last thing he would see would be the faces of the women he thought he owned.

Ezekiel nodded slowly.

He told her he would have the fastest carriage ready and waiting behind the old tobacco barn at midnight on Saturday.

He told her he knew a route through the homito swamps that no search party could follow.

He told her that whatever happened, he would not let them be taken back.

That was his promise.

His only condition was that he would come with them.

There was nothing left for him at Blackwood Plantation except memories of loss.

He wanted to see the north before he died.

Ruth agreed.

They shook hands in the darkness of the stable.

Two people making a pact that would either lead to freedom or death.

There was no middle ground.

The next three days were the longest of their lives.

Ruth and Miriam went through the motions of their regular duties while secretly making preparations.

Ruth harvested the water hemlock from the creek bank, cutting the roots in the gray light before dawn when no one was watching.

She processed it carefully using techniques her grandmother had taught her years ago in a world that now seemed like a dream.

The liquid she produced was clear and almost odless, with only a faint, bitter taste that could be masked by strong wine.

She stored it in a small glass vial that had once held Mrs.

Blackwood’s perfume hidden in the false bottom of her sewing basket.

Miriam worked on the dresses that Silas had ordered, white cotton gowns that he wanted them to wear for the ceremony.

She followed his instructions exactly, except for one small modification.

She added hidden pockets to the inside seams, invisible to casual inspection, large enough to hold the vial and a few other essential items.

Everything had to look normal.

Everything had to seem like acceptance until the moment it wasn’t.

On Friday night, the household was consumed with preparations for the next day’s ceremony.

Extra servants had been borrowed from neighboring plantations.

The kitchen was producing enough food for a 100 guests.

The grand ballroom was being decorated with flowers and candles.

Silas walked through the house, inspecting every detail, more animated than anyone had seen him in years.

He was in the prime of his life.

He announced to anyone who would listen.

He was about to begin a new chapter.

He was going to show all of Nachez that Silus Blackwood answered to no one and followed no rules except his own.

He looked at Ruth and Miriam as he said this, and they saw in his eyes exactly what he was.

Not just cruel but proud of his cruelty.

Not just powerful but intoxicated by his power.

He believed himself untouchable.

He believed that his money and his status put him above consequences.

He had forgotten if he ever knew that the people he considered his property were human beings with memories and minds and the capacity for planning that matched or exceeded his own.

That night, as he slept peacefully in his massive bed, Ruth and Miriam lay awake in their cabin, going over every detail of the next day one final time.

They knew they would either be free or dead by Sunday morning.

They had made their peace with both possibilities.

Saturday, June 14th, 1857, dawned hot and humid, the kind of Mississippi summer day when the air itself seemed to sweat.

The household rose early to complete the final preparations.

Carriages began arriving by late afternoon, carrying the wealthy planter families of Adams County in their finest clothes.

The men wore tailcoats, and the women wore hooped dresses that required two servants to help them through doorways.

They gathered in the ballroom and on the front ver drinking champagne and whiskey, gossiping about politics and cotton prices and the increasingly worrying news from up north about abolitionists and Republicans.

None of them thought there was anything unusual about what they were about to witness.

The relationship between masters and enslaved women was an open secret throughout the South.

The only novel thing about Silas’s ceremony was his decision to make it public.

Some found it distasteful, others found it bold.

All of them were curious enough to attend.

At 7 in the evening, as the sun began to set over the Mississippi River in a blaze of orange and red, Ruth and Miriam made their entrance.

They walked down the Grand Staircase arm in arm, dressed in their white gowns, their hair arranged with white flowers.

Every eye in the room turned to watch them.

They moved with perfect grace, their faces serene, showing not a trace of the rage that burned beneath the surface.

Silus stood at the bottom of the stairs, beaming with proprietary pride.

He took their hands as they reached him and led them to the center of the ballroom where a justice of the peace waited with a Bible in his hands.

The ceremony was brief and meaningless.

Enslaved people could not legally marry and certainly could not marry their masters.

But Silas wanted the performance.

He wanted witnesses to his power.

He wanted everyone in the county to know that these two women were his to do with as he pleased.

The justice read some words.

Silas placed cheap rings on their fingers and then it was done.

The guests applauded politely.

The celebration began.

What happened next in the hours between the ceremony and midnight would later become the subject of endless speculation.

Some witnesses said the twins seemed almost happy, smiling and gracious as they moved through the party.

Others noted that they were never far from Silas, attending to him with what appeared to be genuine devotion.

Ruth personally served him every glass of wine he drank.

Miriam made sure his plate was always full.

They laughed at his jokes.

They endured his hands on their shoulders, their waists, their faces.

They played their parts perfectly.

And no one, not a single one of the hundred people in that house, suspected that they were watching the first act of a tragedy that would end in death.

By 11:00, most of the guests had departed.

The remaining few were too drunk to notice much of anything.

Silas himself had consumed nearly two bottles of wine over the course of the evening, in addition to his usual bourbon.

He was swaying slightly as he made his way up the grand staircase, one hand on the railing, the other around Miriam’s waist.

Ruth followed a few steps behind, carrying a final glass of wine that she had prepared herself.

They entered the master bedroom together, and the door closed behind them.

What happened in that room over the next hour was known only to three people, and two of them would never speak of it.

But the physical evidence discovered the next morning, told its own story.

End of part one.

The master bedroom of Blackwood Plantation was the largest room in the house, occupying the entire southwest corner of the second floor.

Two tall windows overlooked the front lawn and the long drive lined with oak trees.

A third window faced west toward the river, invisible in the darkness, but present in the humid breeze that moved the curtains.

The room was furnished with pieces imported from France and England, a four poster bed with silk hangings, a massive wardrobe of carved mahogany, chairs upholstered in velvet that had cost more than most families earned in a year.

On this night, candles burned in silver holders on every surface, casting flickering shadows across the walls.

Silas Blackwood stood in the center of this room, swaying slightly from the wine, looking at the two young women he believed belonged to him in every possible way.

He had waited 12 years for this night.

He had planned every detail.

He had invited the most powerful people in the county to witness his claim.

And now, finally, he would take what he considered rightfully his.

He had no idea that he had less than an hour to live.

Ruth moved first.

She approached Silas with the glass of wine she had carried from downstairs, the same wine she had been serving him all evening, but this glass was different.

This glass contained three drops of water hemlock extract mixed with honey to mask any bitterness.

She had calculated the dose carefully using knowledge passed down through generations of Ashanti healers.

Too little and he might survive.

Too much and he would die before she wanted him to.

The amount she used would take effect within 30 minutes, beginning with numbness in the extremities and progressing to paralysis of the voluntary muscles while leaving the mind fully aware.

He would be conscious for everything that followed.

he would understand exactly what was happening and he would be unable to move or cry out as his body slowly shut down.

Ruth handed him the glass with a smile.

She told him it was a special vintage she had saved for this occasion.

Silas took it without hesitation.

Why would he suspect anything? These were his slaves.

They had been obedient for 12 years.

They had shown no sign of resistance.

He drained the glass in three long swallows and set it on the dresser.

He would never pick up another object again.

Miriam locked the bedroom door from the inside and pocketed the key.

This was a precaution they had discussed extensively.

The lock would buy them time if anyone came to check on the master.

It would also ensure that Silas could not escape once he realized what was happening.

She moved to the windows and closed the heavy curtains, blocking any view from outside.

The room was now sealed.

Whatever happened next would stay between these walls until they chose to leave.

Silas watched these preparations with confusion that slowly transformed into the first stirrings of fear.

He asked what they were doing.

His voice was already slightly slurred, though he probably attributed that to the wine.

Ruth told him they were making sure they would not be disturbed.

She told him they wanted this night to be private, just the three of them, no interruptions.

Silas smiled at this, his fear momentarily replaced by anticipation.

He still did not understand.

He still believed he was in control.

That delusion would shatter within minutes.

The first symptom appeared approximately 20 minutes after he drank the poisoned wine.

Silas was sitting on the edge of the bed removing his boots when he noticed that his fingers were not working properly.

They felt thick and clumsy as if he were wearing gloves.

He mentioned this casually, assuming he had simply drunk too much.

Ruth and Miriam exchanged a glance that he did not see.

They knew the poison was beginning its work.

Within another 10 minutes, the numbness had spread to his hands and feet.

He tried to stand and found that his legs would not support him.

He fell back onto the bed, his heart beginning to race as he finally realized that something was seriously wrong.

He demanded to know what was happening.

He ordered them to fetch the doctor.

His voice was weaker now, the muscles of his throat beginning to fail.

Ruth sat down in a chair facing the bed and spoke to him in a tone he had never heard from her before.

It was the voice of a free woman addressing an equal or perhaps something less than an equal.

She told him exactly what was happening to his body.

She used the scientific terms she had learned from Mrs.

Blackwood’s medical books.

She explained that the poison would paralyze his muscles one by one while leaving his nerves fully functional, meaning he would feel everything but be unable to move or speak.

She told him this would take approximately 2 hours and she told him that she and Miriam intended to spend those two hours making sure he understood why this was happening.

What followed was not torture in the physical sense.

Ruth and Miriam never touched Silas Blackwood except to arrange his paralyzed body so he could see them clearly.

What they did was worse than physical pain for a man like Silas.

They talked for nearly 2 hours while his body slowly shut down.

They told him the truth about who they were and what they had been doing for 12 years.

They spoke in English so he would understand every word, but occasionally they switched to Twi, their native language, just to remind him that they had an entire world he had never known about and could never access.

They told him about their grandmother, the healer who had given them the knowledge that was now killing him.

They told him about the nights they had spent planning, the information they had gathered, the escape route they had mapped.

They told him about Ezekiel and the carriage waiting behind the tobacco barn.

They told him that by the time anyone found his body, they would be miles away, traveling through swamps that no search party could navigate.

And they told him something that seemed to cause him more anguish than the poison itself.

They told him that they had never been broken, not for a single day.

Every act of obedience had been performance.

Every smile had been a lie.

Every moment he thought he possessed them.

They had been possessing him, gathering information, waiting for the perfect moment to strike.

His entire understanding of his own life was wrong.

He was not a master.

He was a fool who had been outsmarted by people he considered less than human.

The paralysis reached Silas’s face around 1:00 in the morning.

He could no longer speak or change his expression, but his eyes were still alive, still aware, still watching as Ruth and Miriam made their final preparations.

They changed out of their white wedding dresses and into simple dark clothing suitable for travel.

They packed a small bag with food stolen from the kitchen, a knife, a compass that Miriam had taken from Silas’s study months ago, and the forged travel papers that Ezekiel had obtained from a contact in Natchez.

These papers identified them as free women of color traveling to visit family in Illinois.

The papers were not perfect, but they would be enough to get them past casual inspection if they were stopped on the road.

Ruth took one final item from her hidden pocket, a small pot of red dye made from beets that she had prepared earlier in the week.

She crossed to the white wall beside the bed, and began to write.

The letters were large and careful, designed to be visible from across the room.

She wrote in twi in the alphabet that missionaries had developed to transcribe the language.

The words translated roughly to an old Ashanti proverb, “Those who do us evil, we collect the debt.

” She wanted whoever found the body to know that this was not random violence.

This was justice.

This was a debt that had been owed for 12 years and was now paid in full.

At approximately 1:30 in the morning, Ruth checked Silas’s pulse and found it growing weak and irregular.

the poison had reached his heart.

He had perhaps 30 minutes left.

She leaned close to his face and spoke her final words to him.

She told him that she hoped there was an afterlife because she wanted him to spend eternity knowing that he had been defeated by the people he tried to destroy.

She told him that she and Miriam would live free for the rest of their lives and every day of that freedom would be built on his grave.

She told him that his name would be forgotten while their story would be passed down through generations of their descendants.

And then she thanked him.

She thanked him for being so arrogant that he never saw them as threats.

She thanked him for giving them access to his house, his garden, his secrets.

She thanked him for inviting the entire county to witness his humiliation because now there would be no way to cover up what had happened.

Everyone would know that Silas Blackwood died at the hands of his slaves.

That would be his legacy.

Not his wealth, not his power, just the memory of how completely he had been destroyed by the people he underestimated.

Ruth and Miriam left the bedroom at approximately 1:45 in the morning.

They locked the door behind them and took the key, which they later threw into the river.

They moved through the silent house like ghosts.

Avoiding the servants who slept in the back quarters, stepping over the floorboards they knew would creek, they exited through the kitchen door, which Ruth had left unlocked earlier in the evening, and made their way across the moonlit grounds toward the old tobacco barn at the edge of the property.

The barn had not been used in years since Silas had converted entirely to cotton production, and its dark interior made a perfect hiding place for the carriage Ezekiel had prepared.

He was waiting for them in the shadows, holding the reinss of two of the fastest horses in the Blackwood stables.

He asked no questions when he saw them approaching.

He simply helped them into the carriage and climbed up to the driver’s seat.

Within minutes, they were moving, following back roads that Ezekiel knew from years of secret journeys, heading east toward the Homachito wilderness and the river beyond.

The route Ezekiel had planned covered nearly 40 m through some of the most difficult terrain in Mississippi.

The first section followed a series of logging roads that were barely visible in the darkness, winding through pine forests where the trees blocked out the stars.

The horses were trained for speed, but Ezekiel held them to a steady trot, knowing that a broken wheel or a lame horse would doom them all.

They traveled for nearly 3 hours without stopping, putting as much distance as possible between themselves and Blackwood Plantation.

By the time the first gray light of dawn appeared in the east, they had reached the edge of the Homachito swamps, a vast wetland that stretched for miles along the river bottoms.

This was the most dangerous part of the journey.

The swamps were home to alligators and water moccasins, and the paths through them were known to only a handful of people.

But the swamps were also the safest route to the river because no search party would dare follow them into that maze of water and mud and hanging moss.

Ezekiel guided the carriage as far as the solid ground would allow, then stopped and helped Ruth and Miriam down.

From here they would continue on foot.

He led them along paths that seemed invisible to untrained eyes, stepping on roots and rocks that kept them above the water.

warning them in whispers when they approached deeper sections.

The swamp was alive with sound, frogs and insects, and the occasional splash of something large moving through the water.

But they saw no other humans.

This was not land that anyone wanted to claim.

It was a no man’s territory between the plantation country and the river, and it would shelter them until they reached safety.

They walked for nearly 4 hours, stopping only to drink from cantens Ezekiel had packed and to eat a few bites of cornbread.

By midm morning they could hear the sound of the river ahead.

A low, constant rush that grew louder with every step.

And then suddenly the trees opened up and they were standing on the bank of the Mississippi, the great brown river that divided the country that carried cotton to the world and had carried so many enslaved people to their bondage.

Ezekiel had arranged for a contact to meet them at a specific point on the riverbank, a spot marked by a distinctive dead tree that had been struck by lightning years ago.

The contact was a white man named Thomas, a Quaker from Ohio who made his living as a river trader, but spent much of his time helping escape slaves reach free territory.

The Underground Railroad was not a formal organization, but a loose network of individuals who were willing to risk their lives and freedom to help others.

Thomas was one of the most active conductors on the lower Mississippi, and he had helped Ezekiel guide runaways to safety many times before.

His boat was a small steam ship designed for cargo with hidden compartments below the waterline where passengers could hide during inspections.

He was waiting at the dead tree when they arrived, pacing nervously and checking his pocket watch.

The longer they stayed on the bank, the more dangerous their situation became.

He hurried them aboard without wasting time on introductions and cast off immediately, steering the boat into the current and heading north toward Cairo.

The journey up river took 3 days.

Ruth, Miriam, and Ezekiel spent most of that time hidden in the cargo hold, emerging only at night when Thomas judged it safe.

They passed dozens of other boats, some heading south with manufactured goods from the northern factories, others heading north with cotton and sugar from the southern plantations.

Each passing vessel was a potential threat.

any of them might carry slave catchers or sheriffs with warrants for their arrest.

But Thomas knew the river as well as Ezekiel knew the land, and he timed their movements to minimize encounters.

They stopped twice at safe houses along the bank, taking on supplies and receiving news from the north.

The news was promising.

Illinois had strengthened its laws, protecting escaped slaves, and the Republican party was gaining power with its anti-slavery platform.

The world was changing.

The system that had held Ruth and Miriam in bondage for 12 years was beginning to crack.

They might actually make it to freedom.

Behind them, chaos had erupted at Blackwood Plantation.

The body of Silus Blackwood was discovered at approximately 10:00 in the morning on Sunday, June 15th, when a servant came to bring his breakfast and found the bedroom door locked.

After repeated knocking, received no response.

The overseer was summoned and he broke down the door with a sledgehammer.

The scene that greeted them became the subject of horrified gossip throughout the county for years afterward.

Silas lay on his bed in his wedding clothes, his face frozen in an expression of terror, his body already beginning to stiffen.

The red writing on the wall was clearly visible, though no one present could read it.

The two enslaved women who had been part of the ceremony the night before were nowhere to be found.

Neither was the head coachman Ezekiel, nor the finest carriage, nor two of the best horses.

It did not take long to piece together what had happened.

The local sheriff was summoned, and by noon, the largest manhunt in the history of Adams County was underway.

Pies were formed from the neighboring plantations.

Professional slave catchers were hired from as far away as New Orleans.

A reward of $5,000 was posted for the capture of the twins and 2,000 for Ezekiel.

Enormous sums that attracted bounty hunters from across the south.

Telegraph messages were sent to every major city along the Mississippi, warning authorities to watch for two young black women traveling together.

Dogs were brought to Blackwood Plantation to pick up the scent, and they tracked the trail as far as the edge of the Homachito swamps before losing it in the water.

Search parties tried to follow, but several men were bitten by snakes.

One nearly drowned in quicksand, and after two days of finding nothing, the swamp search was abandoned.

The fugitives had vanished as completely as if the earth had swallowed them.

The investigation into Silas Blackwood’s death was complicated by the lack of obvious wounds on his body.

He had not been shot or stabbed or strangled.

There was no sign of violence in the bedroom.

The county coroner, a man with limited medical training, was baffled by the case.

He noted the expression of terror on the face and the rigidity of the limbs, but could not identify a cause of death.

Some witnesses suggested poison, pointing to the empty wine glass found on the dresser, but without the ability to conduct chemical analysis, this remained speculation.

The coroner eventually ruled the death as resulting from unknown causes.

A verdict that satisfied no one but allowed the case to be officially closed.

The general public, however, had no doubt about what had happened.

The twins had killed their master on his wedding night.

The details might be unclear, but the basic truth was obvious.

And this truth terrified every slaveholder in the region.

The fear that spread through Nachez in the weeks after the Blackwood killing was unlike anything the county had experienced.

For generations, white southerners had reassured themselves that their enslaved populations were content, or at least docile, kept in check by the threat of violence and the absence of alternatives.

The story of Ruth and Miriam shattered that illusion.

Here were two women who had been purchased as children, who had spent 12 years in the heart of a plantation household, who had appeared to be perfectly trained and submissive, and who had nonetheless been planning their master’s death all along.

If they could do it, anyone could.

Every slave in every house was suddenly suspect.

Every act of obedience might be concealing murderous intent.

The Natchez authorities responded with increased patrols, stricter enforcement of curfews, and harsher punishments for even minor infractions.

But nothing could restore the sense of security that had been lost.

The system of slavery depended on the psychological subjugation of the enslaved, on convincing both masters and slaves that resistance was impossible.

Ruth and Miriam had proven that it was not.

Meanwhile, Thomas’ steamship continued its journey north.

They passed Memphis without incident.

The city’s waterfront crowded with boats and too busy for anyone to pay attention to a small cargo vessel.

They passed the Missouri border, leaving slave territory behind, but not yet reaching safety.

Since Missouri was a slave state, where they could still be legally captured, they passed St.

Lewis, where the great rivers converged and the traffic was thickest, hiding among hundreds of other boats making the same journey.

And finally, on the morning of June 18th, 4 days after they had left Blackwood Plantation, they reached Cairo, Illinois.

Thomas guided the boat to a small dock on the Illinois side of the river, away from the main warves, where federal marshals sometimes waited to intercept runaways.

He shook hands with Ezekiel and bowed to Ruth and Miriam.

He told them that from here they were on their own.

Illinois was free soil.

The law was on their side, though enforcement was uncertain, and slave catchers sometimes operated illegally.

He recommended they continue north as quickly as possible to Chicago or beyond to Canada if they could make it.

He wished them luck and watched as they walked up the bank toward the town.

Three people who had escaped from one of the crulest systems in human history through a combination of intelligence, patience, and extraordinary courage.

The next phase of their journey took them through the network of the Underground Railroad from safe house to safe house across Illinois and into Indiana, then Michigan, and finally across the border into Canada.

It took nearly 3 weeks, traveling by night, hiding by day, never staying in one place more than a few hours.

They were pursued for part of this journey by bounty hunters who had tracked them north.

But the Underground Railroad was experienced at evading such pursuers, and the network’s conductors managed to stay one step ahead.

They crossed into Canada near Detroit, taking a ferry across the narrow straight that separated the United States from British territory.

Canada had abolished slavery throughout the British Empire in 1833, and American laws had no force there.

The moment Ruth and Miriam stepped onto Canadian soil, they were legally and completely free for the first time in their lives.

They were 19 years old.

They had been in bondage since the age of seven, and they had won.

Ezekiel remained in Canada with them for several months, helping them establish themselves in the black community that had grown up around the border towns.

Many former slaves had settled in this region, building farms and businesses and churches, creating a society where they could live without fear of being kidnapped and returned to bondage.

Ruth and Miriam used the skills they had developed at Blackwood Plantation to find work.

Ruth became a cook at a hotel in Chattam, Ontario, a town known for its large population of American refugees.

Miriam worked as a seamstress, her careful stitching in demand among the local families.

They earned their own money for the first time in their lives.

They walked down streets without permission.

They spoke their minds without fear of punishment.

They were in every way that mattered human beings rather than property.

and they never forgot what they had done to earn this freedom.

They never regretted it for a moment.

The letter arrived in Nachez in the autumn of 1859, more than 2 years after the death of Silus Blackwood.

It was addressed to the sheriff of Adams County and postmarked from Toronto, Canada.

Inside was a single sheet of paper with two sets of fingerprints in ink and a brief message written in elegant handwriting.

The message said simply, “We survived.

We prospered.

We remember.

” There was no signature, but no signature was necessary.

Everyone in Natchez knew who had sent it.

The letter was kept in the county archives for decades, occasionally shown to curious visitors as evidence of the strange events of 1857.

It eventually disappeared during the Civil War when many county records were destroyed by fire, but copies had been made and the story had spread and by the time the letter was lost, the legend of the Blackwood twins had taken on a life of its own.

What happened to Ruth and Miriam after they reached Canada is not completely documented.

Records from the period are incomplete, and black refugees had good reasons to avoid leaving traces that could be used to track them.

What is known comes from fragmentaryary sources, church records, census data, occasional mentions in letters and diaries.

Ruth appears to have married a man named James Monroe Wilson in 1862, a freeborn black man from Philadelphia who had moved to Canada to escape the racial violence of the northern cities.

They had three children together.

Miriam married a year later to a man whose name has not survived in any record.

She also had children.

Both women lived into old age, Ruth dying in 1894 and Miriam in 1897.

They never returned to the United States, though they followed the news from their former country closely.

They watched the Civil War from across the border, knowing that their own small act of rebellion had been part of the larger current that eventually destroyed the slave system.

They watched reconstruction raise hopes for true equality.

And they watched those hopes betrayed by the rise of Jim Crow.

They died knowing that the struggle they had joined was not yet won.

But they also died knowing that they had won their own personal battle.

They had refused to be defeated.

Ezekiel’s fate is less certain.

Some accounts say he remained in Canada until his death in the 1870s.

Others claim he returned to the United States after the Emancipation Proclamation, searching for the wife and children who had been sold away from him decades earlier.

There is a record of a man matching his description in the Freed Men’s Bureau files from Louisiana, inquiring about a woman named Sarah, who had been sold to a plantation near New Orleans in 1849.

Whether he found her is unknown.

The records do not say, but the very existence of these inquiries suggests that he never stopped looking.

That he spent the rest of his life trying to reassemble the family that slavery had torn apart.

This was the reality for millions of formerly enslaved people after the war.

Freedom meant not just escape from bondage, but the beginning of a new struggle.

to find lost loved ones, to build new lives from nothing, to claim a place in a society that had never wanted to acknowledge their humanity.

The story of Ruth and Miriam spread through the black communities of the South in the years after the Civil War.

Former slaves told it to their children and grandchildren.

It became part of the oral tradition that preserved the memory of resistance during a time when official histories ignored or minimized black agency.

The story changed as it was retold, as all stories change.

Some versions added details that may or may not have been true.

Some versions exaggerated the violence or the supernatural elements, but the core of the story remained the same.

Two young women refused to accept their fate.

They used their intelligence and their patience and their ancestral knowledge to defeat a man who believed himself their absolute master.

They escaped to freedom and lived to tell the tale.

This was not a story of victimhood.

This was a story of victory.

And it mattered to the people who heard it because it proved that victory was possible.

Today, Blackwood Plantation no longer exists.

The main house burned during the Civil War, set on fire by Union troops who swept through the region in 1863.

The land was eventually sold and subdivided and cotton gave way to other crops and eventually to suburban development.

There is no historical marker at the site.

There is no monument to Ruth and Miriam or to the hundreds of enslaved people who lived and died on that property.

The county archives contain only fragmentaryary records of the Blackwood family, and most of those focus on property transactions and tax assessments rather than the human lives that produced the wealth.

This is how history works.

The powerful leave records.

The powerless are forgotten.

But sometimes, through extraordinary acts of courage, the powerless force their way into the historical record.

They refuse to disappear quietly.

They insist on being remembered.

This is what Ruth and Miriam accomplished.

They were two young women born into a system designed to erase them, to treat them as property, to deny them every aspect of human dignity.

They could have accepted this fate.

Many people did.

The psychological weight of slavery was designed to crush all hope of resistance.

But Ruth and Miriam remembered who they were.

They remembered the knowledge their grandmother had given them.

They remembered their true names, Adoa and Akua, even as they answered to the names their capttors assigned.

They remembered that they were human beings with minds and wills and the right to determine their own futures.

And they spent 12 years waiting for the moment when that memory could be translated into action.

When the moment came, they were ready.

They did not hesitate.

They did not show mercy to a man who had shown no mercy to them.

They claimed their freedom with their own hands and they kept it for the rest of their lives.

The lesson of their story is not complicated.

It does not require philosophical analysis or historical interpretation.

The lesson is simply this.

Resistance is always possible.

Even in the darkest circumstances, even when the entire system is designed to prevent it, people find ways to fight back.

Sometimes they fail.

Many acts of resistance during slavery ended in brutal punishment or death.

But some succeed, and even the failures matter because they prove that the human spirit cannot be entirely extinguished.

The slaveholders of the American South spent two centuries trying to create a system of perfect control where the enslaved population would accept their bondage as natural and inevitable.

They failed.

They failed because human beings are not property.

They failed because you cannot own someone’s mind no matter how completely you control their body.

They failed because in every generation, in every community, there were people like Ruth and Miriam who refused to surrender.

The system of slavery was eventually destroyed, not just by armies and laws, but by the accumulated weight of countless acts of resistance, large and small, remembered and forgotten, that proved the system could not last forever.

We tell this story today not as entertainment, but as evidence.

Evidence that the people who suffered under slavery were not passive victims waiting to be rescued.

Evidence that they fought back with every tool available to them, including tools their oppressors never suspected they possessed.

Evidence that the history of black Americans is not just a history of suffering, but a history of survival and resistance and ultimate triumph.

Ruth and Miriam did not wait for Abraham Lincoln to free them.

They did not wait for the Union Army to liberate the South.

They freed themselves.

They wrote their own emancipation proclamation in red letters on a white wall in a Mississippi mansion.

And then they walked out of bondage into a new life.

That is who they were.

That is what they did.

And that is why their story deserves to be remembered.

Now you know the story that the history books never told.

The story of the twins who waited 12 years.

The story of the wedding that ended in death.

The story of the three fugitives who vanished into the swamps and emerged on the other side as free people.

This is American history.

Not the comfortable version.

Not the version that pretends slavery was a long time ago and has no connection to the present.

The real version.

The version where enslaved people were not objects but subjects.

Not victims, but actors, not problems to be solved, but people who solved their own problems with courage and intelligence and an unbreakable will to be free.

Ruth and Miriam understood something that their master never grasped.

They understood that freedom is not given.

It is taken.

And once taken, it can never be taken away.

News

Samuel, The Poisoner of Charleston: Slave Who Killed 12 Masters During the 4th of July Celebration

In the early hours of July 4th, 1833, while Charleston celebrated white men’s freedom, 12 plantation masters fell silently inside…

Why Mel Brooks Refused to Go to Rob Reiner’s Funeral?

When Romy Reiner called Mel Brooks to invite him to the final memorial service for her parents, he refused immediately….

Rob Reiner’s Funeral, Sally Struthers STUNS The Entire World With Powerful Tribute!

Amid the heavy grief soaked atmosphere of Rob Reiner’s funeral, when everything seemed carefully arranged to pass in orderly sorrow,…

7 Guests That Were Not Invited To Rob Reiner’s Funeral

One week after the horrific tragedy in which Rob Reiner and his wife passed away, Romy and Jake held a…

Gene Simmons tells Americans to ‘shut up and stop worrying’ about politics of their neighbors

Gene Simmons Tells Americans to ‘Shut Up and Stop Worrying’ About the Politics of Their Neighbors: A Bold Call for…

HOLLYWOOD HOLDS ITS BREATH: THE NIGHT ROB REINER’S LEGACY SPOKE LOUDER THAN ANY APPLAUSE

For once, Hollywood did something almost unthinkable: it went quiet. No red carpets. No flashbulbs. No rehearsed laughter echoing through…

End of content

No more pages to load