In the summer of 1972, a native mother and her two young children vanished from their small farmhouse in northern Oklahoma.

And for 22 years, their names were spoken only in whispers.

She was 34, a widow raising her family alone, known for her sharp voice and sharper courage.

Her son was just 5 years old, a boy who carried a toy truck everywhere he went, and her daughter, only two, toddled through the yard, clutching a ribbon in her hair.

They weren’t wealthy.

Their farmhouse sat on a modest stretch of tribal allotted land.

But that land was worth more than anyone admitted.

Developers had been circling it for years.

Men in pressed suits and polished boots who wanted it cleared for a highway expansion.

The mother refused.

She had filed petitions argued with deputies, even threatened to bring the case to newspapers.

This land is ours.

She told neighbors, “If we give it up, they’ll take everything.

” That summer, the pressure grew unbearable.

tires slashed, strange trucks idling on the dirt road at night, men knocking at her door with offers of cash she refused.

Then one night, her family disappeared.

The house was left as if time had stopped.

A pot of beans cooling on the stove, laundry folded neatly on the table, her son’s toy truck lying in the yard.

But the family was gone.

The sheriff’s office filed it as a probable runaway.

The newspaper ran a short paragraph and then the case was closed.

For 22 years, nothing moved.

The farmhouse rotted, the land changed hands, and the family’s name faded from official records.

But in 1994, when an abandoned mansion on the edge of town was slated for demolition, a crew broke open a sealed upstairs room.

And what they saw inside would haunt everyone who entered.

It was the truth left hanging in plain sight for more than two decades.

Before the summer of 1972, the Red Fern Place had been ordinary in every way except for the weight it carried.

The farmhouse was small, two bedrooms, paint peeling on the siding.

The roof patched with tin where storms had torn shingles free.

Chickens wandered the yard and laundry hung on a sagging clothesline.

But beneath its weathered boards lay something men with power wanted.

Land.

20 acres of fertile ground allotted to the family under a treaty signed long before highways and developers began carving through the county.

For years, surveyors had eyed that land.

Men from the county office would appear in pressed shirts and ties carrying clipboards and rolled up maps.

They called it eminent domain.

Said a new road was planned.

A highway to connect Tulsa with the smaller towns west.

But everyone knew what it really meant.

The county and the developers wanted the land for themselves.

Most native families had been bullied or tricked into signing papers they didn’t understand, selling their allotments for pennies.

This mother refused.

Her name was Clara Redern.

34, sharpeyed and soft-spoken until pushed.

Neighbors remembered her standing on the porch, child on her hip, telling men in suits to get off her property.

“This land belongs to my children,” she said.

“You’ll take it from us only when I’m dead.

” Clara had reasons to fight.

She was a widow.

Her husband had died in a work accident on a steel project in Tulsa.

A death that left her raising two children alone.

The boy Samuel was five, wiry, restless, with a cow lick in his hair and a toy truck he carried everywhere.

The little girl, Rosie, had just turned two, toddling with ribbons in her hair and a laugh that carried across the fields.

Clara knew that if she lost the land, she lost everything.

Her home, her children’s future, the only tie they had to their people’s history.

But her defiance came at a cost.

By early 1972, threats had become routine.

Neighbors saw unfamiliar trucks idling by the road at night, engines low, headlights off.

Strangers knocked at the door offering envelopes of cash in exchange for her signature.

One evening, Clara came into town with her tires slashed, her children frightened in the back seat.

She reported it to the sheriff, but he waved her off.

“Probably kids playing a prank,” he said.

Word spread in the community that Clara was being taught a lesson.

A cousin warned her to stop fighting, to sign the papers before things got worse.

Clara shook her head.

If I give them this, they’ll never stop.

It won’t just be my land next.

It’ll be all of ours.

Still, the tension grew.

That spring, Samuel stopped walking alone to the neighbors to fetch milk because Clara didn’t trust the truck she’d seen.

She began keeping Rosie close at all times, refusing to let the toddler out of her sight.

And yet, despite the fear, she kept filing petitions.

She even wrote to a local paper, though the letter never appeared in print.

By June, whispers swirled that men had been inside the old Davenport mansion, a sprawling estate on the edge of a town that had stood empty for years.

The place was decaying, its windows boarded, its roof sagging.

Some said developers had been using it to store equipment.

Others said county deputies met there for poker games.

Children told stories of it being haunted.

Clara didn’t believe in ghosts, but she did believe in men who wanted her silence.

On the night of June 18th, 1972, neighbors recalled seeing Clara on her porch, Rosie on her hip, Samuel playing in the yard.

By morning, the house was silent.

The beds were still made.

A pot of beans cooled on the stove.

The laundry was folded neatly on the table.

Samuel’s toy truck lay abandoned in the dirt outside.

Clara and her children were gone.

The sheriff arrived late that afternoon, walked through the house once and shook his head.

Probable runaway, he wrote on the report.

No canvas, no interviews, no search party.

The case was closed before it had even begun.

For the community, it was unthinkable.

Clara had no money, no car, no reason to run.

She would never leave her land, not willingly.

But their voices didn’t matter.

The red ferns were declared vanished, and the file was shoved into a drawer.

It would stay there, gathering dust for 22 years until the truth was found, not in the farmhouse where they had lived, but in the rotting upstairs room of an abandoned mansion, sealed away in darkness, waiting for the day someone broke the lock.

In the weeks that followed Clara Red Fern’s disappearance, Red Willow grew quiet in a way that felt unnatural.

Her absence weighed heavy on the people who knew her best.

And yet, outside the reservation, the silence was almost total.

The sheriff’s office never issued a public alert.

No flyers were printed.

No search dogs were called.

No neighboring counties were notified.

On paper, the Red Ferns were gone by choice.

a runaway case filed neatly away, the report no longer than two pages.

But within the native community, no one believed that Clara was not the kind of woman to run.

She had fought too hard for her land, raised her children with too much care, and clung to her roots too tightly to ever vanish willingly.

Neighbors recalled the half-cooked beans still sitting on the stove, the folded laundry.

Samuel’s toy truck left in the yard.

“You don’t cook dinner and fold laundry if you’re planning to leave in the night,” one elder said.

“You don’t leave your baby’s shoes by the bed.

” Whispers began to spread.

Some said they had seen Clara arguing with two men in suits just days before.

Others swore that a Black County truck had been parked outside her lane the very night she disappeared.

Its lights off, engine idling.

A few brave enough to speak claimed they had seen figures carrying something heavy into the old Davenport mansion after dark, but their voices were quickly drowned out by fear.

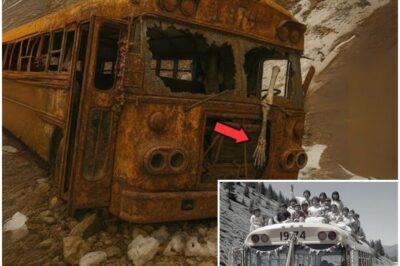

The Davenport mansion had stood for nearly half a century on the edge of town.

Built in the 1920s by a wealthy oilman, it had been abandoned for years.

Its windows boarded and its roof sagging under storms.

Locals said it was haunted, that strange noises carried from its halls, that animals wouldn’t go near it, that children who dared each other to sneak inside always returned pale and shaken.

But those stories masked a more practical truth.

The house was secluded, forgotten, and shielded from prying eyes, the perfect place for secrets.

For years, rumors clung to the mansion like ivy.

Workers whispered it had been used by county officials for off the books meetings.

Others claimed developers had stored stolen equipment in its locked rooms.

A few even suggested deputies used it to send messages to people who refused to cooperate.

Nothing was ever proven, but everyone knew better than to ask too many questions.

Clara’s family begged the sheriff to investigate the mansion.

“At least search it,” her cousin Ruth pleaded.

“At least look for her.

” But the sheriff brushed her off.

He claimed there was no probable cause to search private property, no evidence that Clara or the children had ever been inside.

Instead, he warned Ruth to drop the matter before she made trouble for herself.

Over time, the whispers died down.

People still talked about Clara in hushed tones at church or when passing the farmhouse where the laundry line sagged in the wind, but few dared to push further.

The price of speaking out was too high.

Everyone had seen what happened to families who stood in the way of the county’s plans.

By 1973, the Red Fern land had been auctioned off.

Without Clara to fight, her allotment was declared abandoned.

The highway project moved forward.

Where her farmhouse once stood, surveyors drove stakes into the ground.

Bulldozers flattened the earth.

To the state, Clara’s refusal had ended exactly as they wanted.

Her family gone, her land reclaimed.

But the memory of that night lingered like a shadow.

Children walking past the Davenport mansion swore they could hear faint creeks from the upper floor, as if ropes shifted when the wind blew.

Some claimed to see a child’s silhouette in the upstairs window, though the glass was long shattered.

For decades, no one entered.

No one dared.

And so for 22 years, the truth remained sealed inside.

until 1994 when a demolition crew arrived to tear down the decaying mansion and by accident unlocked the door to a room that had not been opened since the night Clara and her children disappeared.

Inside, they found what no one in Red Willow ever forgot again.

By the summer of 1994, the Davenport mansion was little more than a ruin.

The roof sagged in the middle.

Windows were broken out by storms and vandals, and vines had swallowed whole corners of the once proud estate.

The county had finally condemned it, calling it a safety hazard, and a demolition crew was sent in to tear it down.

For most in Red Willow, it was just another old ghost finally being buried.

But for the men who swung the hammers that day, it would become the most haunting discovery of their lives.

The crew started in the lower rooms, pulling down plaster and hauling out old beams.

The house groaned with every strike, as if protesting the end of its long silence.

Then one worker prying at a boarded hallway upstairs noticed something strange.

Behind the rotting boards was a door.

Not the kind you’d find in a hallway, but a narrow locked one sealed with rusted nails.

It wasn’t on any blueprint, not even listed in the old county property records, a hidden room.

Curiosity got the better of them.

They pried the boards away, tore through the nails, and forced the door open.

What hit them first was the air, thick, stale, choking with a smell that was hard to place, but unforgettable once breathed.

It was the smell of time.

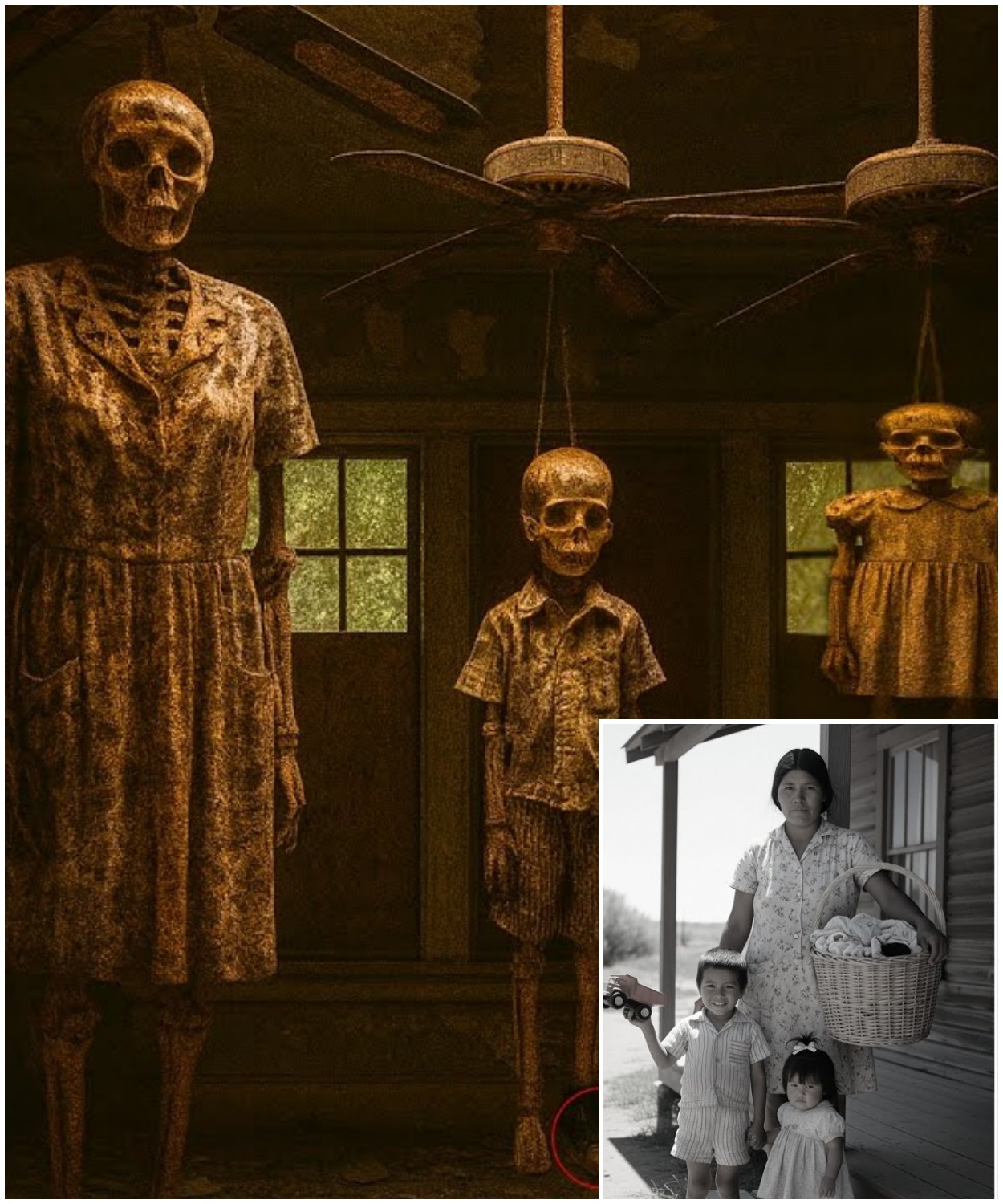

The room was dark, windows nailed shut, dust hanging in beams of light from the cracks in the boards, and then they looked up.

Hanging from the ceiling from three separate fans were the remains of a mother and her two children.

22 years had passed, but the scene was unmistakable.

The ropes, frayed but still knotted, had held all this time.

The skeleton swayed gently in the draft of the open door, as though caught mid-motion, frozen in time.

Even after decades, the details told their own story.

The mother’s bones still bore the faded scraps of a floral dress, torn, but recognizable, the hem brushing against the dust below.

Beside her, the boy’s small frame dangled, his short-sleeved shirt and shorts eaten through by moths and rot, but one tiny shoe still clung to his foot.

The toddler girl’s skeleton was the smallest of all.

Her tiny frock, now nothing but tatters, still tied with a ribbon where her hair once had been.

It was not just death they saw, but a family left exactly as they were on the night of their murder.

The crew stumbled back in shock.

One man wretching against the wall, another dropping his crowbar with a clang that echoed through the empty halls.

No one spoke at first.

They didn’t have to.

They all knew what they were looking at.

This wasn’t a ghost story.

This wasn’t a haunting.

It was murder staged and sealed, hidden behind boards for over two decades.

When the sheriff’s office arrived, younger deputies went pale at the site.

Older ones exchanged uneasy glances, their faces tight with something more than shock, as if the discovery confirmed a truth they had always known, but never spoken.

Forensics moved in carefully, photographing everything, measuring the ropes, bagging what little fabric remained.

Every item was documented.

The floral dress, the boy’s toy shoe, the toddler’s ribbon.

Proof that Clara Redern and her children had never run away, had never left their home willingly.

They had been executed and displayed as a warning, and then locked away like a secret no one was supposed to find.

The news spread through Red Willow like fire.

For years, families had whispered that the Davenport mansion was cursed.

Now they knew why the curse wasn’t supernatural.

It was man-made and it had been hanging there all along.

The discovery at the Davenport mansion ripped through Red Willow like a lightning strike.

For 22 years, people had lived with rumors, with whispers that Clara Redern and her children hadn’t run away, but had been silenced.

Now the truth swung above their heads, literally from those rotted ceiling fans.

What the demolition crew had stumbled into was not just a crime scene.

It was a message left hanging in time.

The forensics team worked in silence, their cameras clicking in steady bursts.

They measured every rope, marked every knot, and carefully lowered the remains one by one.

Each body told its own story.

Clara’s wrists bore the faint impressions of bindings long since faded into the bone, suggesting she had been restrained before death.

The boy’s small arms showed fractures as though he had struggled, fought against the men who tied him up.

The toddler, Rosie, was so tiny that the rope had slipped cruy around her neck.

Her fragile bones still tangled in the knot that had held her up for decades.

Their clothing, though rotted, was unmistakable.

Investigators pulled the scraps into evidence bags.

A floral dress, once bright, now dulled and torn.

A boy’s cotton shirt with faint stripes still visible.

A toddler’s faded frock tied with a tiny ribbon.

Each piece was cataloged.

Each piece matched exactly what neighbors remembered seeing the night the family vanished.

And then there were the objects.

Near Clara’s bones, a rusted key ring.

Near Samuel’s remains, a small toy truck, its wheels corroded, but intact.

Near Rosie, a baby’s leather shoe, still laced.

These weren’t just personal items.

They were anchors in time.

proof that the family had been taken directly from their home to this place and left like trophies in the dark.

Outside the mansion, word had spread fast.

A crowd gathered.

First a handful of locals, then dozens.

Some came out of curiosity, others in mourning.

Elders stood with arms crossed, eyes wet with tears, while children whispered nervously about the house they had always been told was haunted.

To them, the stories had always been superstition.

Now they understood.

The house wasn’t haunted by ghosts.

It was haunted by a crime.

Reporters descended within days.

Local television showed the boarded windows, the yellow tape strung across the lawn, the line of deputies guarding the door.

Headlines screamed about the Red Fern family mystery solved and grizzly discovery in abandoned mansion.

But for those who knew Clara, the headlines barely scratched the surface.

This wasn’t just about a mother and two children found after two decades.

It was about why they had been there in the first place and why no one had searched sooner.

Old wounds reopened.

Community members recalled how Clara had begged for protection, how she had reported threats that were never logged.

They remembered the strange black truck parked near her lane, the men in suits who came with contracts she refused to sign, and they remembered the sheriff’s words, probable runaway.

Now, it was undeniable that her disappearance had been a murder.

The question was who had orchestrated it and why so many had worked to keep it buried.

The Davenport mansion itself became a symbol of that silence.

For decades it had loomed over Red Willow as a decaying relic, a place avoided, feared, written off as superstition.

All the while it had been hiding proof of corruption in plain sight.

Some began to ask aloud what others had whispered for years.

Had the sheriff known? Had developers and county officials used the house to hide what they had done? How many people had looked the other way while a mother and her children swung in the dark? The sheriff’s office, now under new leadership, announced a full investigation.

Boxes of old files were hauled out, dusty and incomplete.

Deputies combed through property records, searching for who owned the Davenport mansion in 1972 and who had access to it.

They began questioning retired officers, many of whom claimed ignorance, but some of whose nervous glances suggested otherwise.

For Clara’s surviving relatives, the discovery was both relief and torment.

Relief that their whispers had been vindicated.

torment that the truth had been ignored for so long.

Clara’s cousin Ruth, who had begged authorities to search the mansion decades earlier, stood outside the caution tape, shaking her head.

They were here the whole time, she said.

We told them.

We told them.

As night fell over Red Willow that first day, the crowd outside the mansion lingered, candles flickering in the wind.

Some prayed aloud, others sang in quiet voices.

And though the house still stood, its secret was gone.

What had once been a tomb of silence was now a spotlight, forcing everyone, the county, the state, and the country, to reckon with what had been done.

The Red Ferns hadn’t vanished.

They had been murdered.

And for the first time, the proof was undeniable.

The days following the discovery inside the Davenport mansion were unlike anything Red Willow had ever seen.

What had once been a sleepy town, where stories lived only in whispers, suddenly became the center of a media storm.

Satellite trucks crowded the courthouse square.

Reporters from Tulsa, then Oklahoma City, then even national outlets swarmed the scene, all repeating the same chilling line.

After 22 years, the Red Fern family has been found, murdered, their bodies hanging inside an abandoned mansion.

Every broadcast replayed the same footage.

Deputies carrying out evidence bags, forensics teams stepping through the cracked doorway.

The yellow tape stretched across the lawn.

Anchors spoke solemnly of grizzly secrets and cold cases reopened.

But in Red Willow, the mood was anything but clinical.

It was fury long buried, boiling to the surface.

At community gatherings, elders stood and demanded answers.

Why had the sheriff in 1972 dismissed the disappearance as a runaway? Why had no one searched the Davenport mansion even when Clara’s cousin Ruth had begged them to? Why had her petitions and letters vanished from county records erased as though she had never spoken? Each question cut deeper because everyone already suspected the answer.

Clara had not just been ignored.

She had been silenced and the system had chosen not to hear.

Investigators from the state arrived quickly, seizing boxes of old county files.

The files were thin, almost laughably so.

A single report stamped probable runaway.

No interviews, no canvasing, no follow-up.

But digging deeper, the state uncovered something more disturbing.

Clara’s petitions about her land, documents she had filed with the county in the months before she vanished, were missing.

Entire folders had been stripped bare.

The paper trail had been scrubbed clean.

Still, fragments of the truth survived in memories.

Retired workers came forward, some reluctantly, some trembling as though speaking out might still bring danger.

They recalled Clara refusing to sign over her land to developers tied to a highway expansion project.

They remembered men in Black County trucks showing up late at night standing on Clara’s porch.

One man, a former surveyor, admitted he had overheard deputies joking about the woman who wouldn’t quit.

When pressed, he confessed what everyone feared.

They said she’d end up like all the others if she didn’t sign.

the others.

That word hung heavy in the air.

Had there been more? Were other native families who resisted also disappeared? Their cases buried under the same runaway label? Attention soon shifted to the mansion itself.

Property records revealed that in 1972, the Davenport estate had quietly transferred to a holding company linked to a local contractor.

the very same contractor lobbying for the highway project.

Witnesses now recalled seeing county deputies frequenting the mansion during that time.

A hidden room sealed and locked would not have gone unnoticed by men using the house regularly.

To many, the implication was clear.

The mansion wasn’t just a hiding place.

It was a stage, a warning carefully constructed to terrify anyone who thought about resisting.

As investigators pieced this together, the community grew angrier.

Vigils turned into protests.

Families marched to the county offices holding signs with Clara’s name, her children’s names, and the words, “They were not runaways.

” Local officials tried to deflect, blaming the failures on the era or on limited resources, but no one bought it.

People remembered too clearly how quickly deputies had mobilized when cattle went missing or when white families reported burglaries.

They had chosen not to act for Clara.

Meanwhile, Ruth, Clara’s cousin, who had fought for answers all those years, became the voice of the family.

In interviews, she held up Samuel’s rusted toy truck pulled from the crime scene.

They told us she ran away, but my cousin didn’t run.

They hung her like she was nothing.

They hung her babies beside her.

And for 22 years, you let them rot in that house.

Her words cut through every broadcast, searing the image of what had been found into the public conscience.

The case now had the state’s full attention.

A task force was assembled, digging into the land transfers, the missing petitions, the ties between county deputies and contractors.

For the first time, it seemed possible that the truth might be dragged into the light.

But as the walls began to close in, those who had built their lives on the silence of 1972 started to resist.

Retired officials suddenly couldn’t remember.

Developers claimed lost records.

One key witness, a former deputy, was found dead in his home just days before he was scheduled to testify.

His death ruled natural causes.

It became clear that the same forces that had killed Clara and her children were still powerful, still protecting themselves decades later.

The Red Ferns had been murdered not just out of hate or cruelty, but out of convenience, because their land stood in the way, because their voices refused to be silenced, because their very existence was a threat to those in power.

And now with their remains hanging as undeniable evidence, the system faced a reckoning it could no longer hide from.

The case against those responsible for the Red Fern murders was never going to be simple.

Two decades had passed since Clara and her children vanished.

And in that time, evidence had been buried, records shredded, and witnesses intimidated into silence.

Still, the discovery in the Davenport mansion was too shocking, too undeniable to ignore.

State prosecutors announced their intent to pursue charges, calling the case a test of whether justice can survive time.

Almost immediately, the walls of resistance went up.

Lawyers for the construction company that had once owned the Davenport property insisted their client had no knowledge of the hidden room.

Retired deputies claimed faulty memory, saying they barely recalled the case, though their names were on the original 1972 report.

Others flatly denied ever setting foot inside the mansion, despite witnesses recalling poker games and late night meetings held there.

But cracks began to show.

A janitor from the county courthouse, long since retired, came forward to say he had personally seen men carrying boxes of Clara’s petitions into the basement one night.

Boxes that never appeared in official records again.

A former secretary admitted she had typed up land transfer documents under orders from a county commissioner, even though Clara herself never signed them.

And a surviving construction worker told reporters, his hands shaking, that he had seen deputies load something heavy into the mansion late at night in June of 1972, muttering, “This will shut her up.

” For the first time, the chain of complicity was visible.

Land developers stood to gain from Clara’s silence.

County officials cleared the paperwork, and deputies enforced the terror.

The Red Fern murders weren’t the work of a lone criminal.

They were the product of a system that decided one native woman and her children were expendable.

The trial that followed was messy, bitter, and slow.

Defense lawyers attacked the evidence, pointing out the degradation of time, ropes that had frayed, clothing too decayed to yield fibers, remains too old for conclusive forensic testing.

They painted the witnesses as unreliable, scenile, or motivated by bitterness.

When Ruth testified holding Samuel’s rusted toy truck in her hands, the defense sneered that grief had clouded her memory.

But Ruth’s voice shook the courtroom.

“You want to talk about memory?” she said.

“That house remembered.

Those walls remembered.

For 22 years, they hung in there.

Don’t you dare tell me I imagined it.

Despite the power of her testimony, the case stumbled.

One after another, key witnesses fell away.

Some recanted under pressure, others vanished from town, and one, a former deputy, died under mysterious circumstances before he could take the stand.

Each loss eroded the foundation of the prosecution.

Journalists whispered about intimidation, about powerful men still pulling strings behind the curtain, just as they had in 1972.

Meanwhile, outside the courthouse, protests grew.

Signs reading, “Justice for the Red Ferns” filled the steps.

Families of other missing native people joined, holding photos of their own lost loved ones.

Clara’s story had struck a chord because it wasn’t just her story.

It was every family who had been ignored, dismissed, erased by official silence.

The Red Ferns had become a symbol.

Inside, prosecutors pressed on, presenting property records that showed Clara’s land transferred within months of her disappearance, signed off by county officials, and funneled through shell companies linked to the highway project.

They showed aerial photographs proving the Davenport mansion had been used during that same period despite officials swearing it had been vacant.

Piece by piece, the picture emerged.

Clara had been murdered because she refused to give up her land and her children killed with her to erase the line of resistance.

But the final blow came when one of the men long suspected of involvement, a former deputy named Cole Harrington, took the stand.

Wrinkled, gay-haired, and bitter, Harrington spoke with an arrogance that shocked the courtroom.

He admitted to being at the Davenport mansion the summer Clara disappeared.

He admitted to guarding the property when it was under county use.

And then under pressure, he said the words that sealed the truth in everyone’s mind.

That woman thought she could stand in the way of progress.

We showed her what happens when you stand in the way.

The courtroom erupted.

Gasps, shouts, even sobs echoed through the chamber.

Ruth broke down in tears.

Journalists scribbled furiously, capturing the line that would dominate headlines.

But Harrington never faced true punishment.

By the time appeals wound their way through the courts, he was dead, never sentenced, never imprisoned.

Others implicated walked free, their influence shielding them even as the truth spilled into the open.

The system had done in 1994 what it had done in 1972, protected its own.

Still, something had changed.

For the first time, the cover up was undeniable.

For the first time, the murder of Clara and her children was not just whispered in kitchens or church basement, but shouted on the front page of national newspapers.

And though justice in the courtroom slipped away, justice in memory, in truth, was finally clawed back.

The Red Ferns had not been forgotten.

They had not been erased.

Their story had survived 22 years in silence, and now it had risen, impossible to bury again.

When the trial ended with little more than words and unfulfilled promises, many in Red Willow felt the sting of betrayal all over again.

The legal system had once more shown whose side it was on, protecting developers, county officials, and deputies, while native voices were left pleading outside the courthouse doors.

Clara Redern and her children had been murdered, their bodies left hanging in a locked room for 22 years, and still the men responsible walked away untouched.

But what the courthouse denied, the community refused to forget.

Almost immediately after the trial, Clara’s name began appearing on banners at protests across Oklahoma.

At vigils for missing native women, people carried signs that read, “Remember the red ferns.

” At rallies against land seizures, chants of Clara stood, so we stand, filled the air.

Her story became more than a tragedy.

It became a rallying cry, a reminder of what had been taken and why the fight could not stop.

In Red Willow itself, the push for memory was personal.

Community leaders organized a march to the Davenport mansion.

The house was set to be demolished.

The county eager to erase the stain of its secrets.

But before the machines tore it down, dozens gathered at its crumbling steps.

Elders prayed aloud, their voices carrying through the overgrown fields.

Children lit candles and placed them in the doorway.

Some wept openly as Ruth, now gay-haired but unbowed, stood at the front and spoke.

“They thought they could bury them here,” she said, her voice breaking but strong.

“They thought if they nailed the door shut, time would forget.

But time remembered this land remembered and so will we.

When the mansion finally came down, the rubble was not cleared to make way for development.

Under pressure from the community, the site was declared sacred ground.

A small memorial was erected.

A stone engraved with three names, Clara, Samuel, Rosie, and the words, “They were not runaways.

” Families came from miles away to leave flowers, children’s toys, and ribbons at the base.

Each offering was a vow that the silence that had hidden them would never return.

Meanwhile, Clara’s story spread far beyond Red Willow.

Native activists invoked her name in testimony before Congress when speaking of the crisis of missing and murdered indigenous women.

Documentaries replayed the chilling footage of the Davenport mansion, using it to show how systemic neglect had cost lives for generations.

College classrooms dissected the case, not as an anomaly, but as a symptom of a broader injustice, how native voices had been ignored, erased, and suppressed in the name of progress.

For Ruth and the family, there was no comfort in the legacy.

Justice isn’t headlines, she told a reporter.

Justice would have been Clara here raising her children.

Justice would have been Samuel growing up, Rosie living to see her own babies.

All we have is truth.

And truth is not enough.

Still, truth mattered.

Where there had once been silence, there was now a story spoken aloud, passed on like a warning and a promise.

The Red Ferns had not been erased.

No matter how hard the county had tried, their faces appeared on murals, their names on petitions, their story in the mouths of those who refused to be quiet.

In the end, the mansion was gone.

The men who killed them buried or beyond the reach of the law.

But the Red Ferns endured in memory.

Their tragedy turned into a weapon against forgetting.

And every time someone whispered Clara’s name, every time a ribbon was tied to the memorial stone, it was proof that the crime meant to erase them had done the opposite.

It had made them unforgettable.

In the years after the Davenport mansion was reduced to rubble, the story of Clara Redern and her children spread far beyond Red Willow.

What began as a local tragedy became a symbol woven into the larger fabric of native history.

A history filled with disappearances, unanswered questions, and names struck from the record books as if they had never existed.

The Red Fern story refused to fade because it embodied a truth too many had lived.

Justice was not denied by chance.

It was denied by design.

Universities began to invite Ruth to speak, her voice carrying the weight of a family suffering turned into testimony.

She brought with her a small wooden box lined with felt.

Inside lay the few relics salvaged from the crime scene, Samuel’s rusted toy truck, Rosy’s tiny shoe, and the tarnished keyring that had hung near Clara’s bones.

She would set them on a table in front of students or politicians and let the silence stretch before speaking.

“These were my family,” she said.

“Not exhibits, not evidence.

Family, and for 22 years, they were left in the dark because it was easier to forget them than to fight for them.

” For younger generations of natives, Clara’s defiance became a kind of inheritance.

Artists painted murals of her holding her children’s hands, standing defiantly in front of bulldozers and black trucks.

Musicians wrote songs about her.

Her voice imagined as a mother’s lullabi cut short by violence.

Activists marched with her name painted across their banners, placing her alongside other missing and murdered indigenous women whose cases had been neglected or covered up.

The ripple effects reached even further.

In Oklahoma City, lawmakers were pressed to open reviews of dozens of old runaway cases involving native families.

Files once dismissed were dusted off, revealing similar patterns, missing petitions, lost land, silenced voices.

While few led to prosecutions, the sheer volume of neglect painted a damning picture of systemic erasure.

Every file became another reminder that the Red Ferns were not alone and that their story was not an isolated horror, but part of a larger injustice stretching back generations.

Back in Red Willow, the memorial at the old Davenport site became a pilgrimage point.

Families drove hours to leave offerings.

Children’s toys, flowers, feathers, and ribbons tied carefully around the stone.

Each item was both a remembrance and a demand.

A demand that no other family should wait decades to learn the truth.

That no other mother’s voice should be silenced for daring to hold on to land.

That no more children should be lost to probable runaway stamps in dusty files.

Ruth, though aging, never stopped visiting.

Once a month she came, sitting in a folding chair beside the memorial stone.

Some days she spoke to the visitors, telling them about Clara’s stubbornness, Samuel’s wild laughter, Rosy’s little ribbon.

Other days she sat in silence, staring at the stone as if willing the past to loosen its grip.

“They wanted us to forget,” she would say softly to those who lingered.

“But look, we didn’t, and we won’t.

” The county, eager to move on, tried to downplay the story in the years that followed.

Officials framed it as a tragedy of the past, something no longer relevant to modern times.

But in truth, the shadow of the Red Ferns never left.

Politicians who once scoffed at native complaints now found themselves haunted by Clara’s name.

Developers who bought land hesitated when confronted with protesters holding signs that read, “Remember the Red Ferns.

” Even the sheriff’s department, now under new leadership, quietly hung a photograph of Clara’s memorial in their lobby, though they never publicly admitted their offic’s role in her fate.

The power of the story lay in its persistence.

Clara had been killed to erase her resistance.

Her children murdered to end her line.

But instead of silence, her name was spoken louder than ever.

Instead of eraser, she became unforgettable.

Every new generation learned the story in classrooms, in protests, and whispered bedtime retellings meant to remind children of both the dangers they faced and the strength they carried.

By the early 2000s, when documentaries aired on national television, the haunting images of the Davenport mansion’s sealed room brought gasps to viewers far removed from Red Willow.

They saw the ropes, the decayed clothing, the children’s toys.

And then they heard Ruth’s words.

They were not runaways.

They were murdered because they stood in the way.

Don’t let the silence swallow them again.

The Red Fern story had begun as a warning meant to terrify one community into silence.

Instead, it had become a torch carried from town to town, rally to rally, generation to generation.

Clara’s defiance had outlived the men who tried to break it.

Samuel’s toy truck became an icon in photographs.

Rosy’s ribbon tied to fences and lamp posts across the state.

The memory of what was found in that mansion, the image of a mother and her children hanging in darkness, never faded.

It lingered, a wound and a weapon, reminding everyone that the cost of silence was measured not in years, but in lives.

Time has a way of burying stories.

Names fade from headlines.

Files gather dust in basement.

And tragedies are reduced to whispers carried only by those who remember.

But the Red Fern family refused to be buried.

Their story broke through the silence of 22 years, tore open the locked door of a forgotten mansion, and exposed the truth that had been nailed shut with them.

Clara Redern had stood alone against men with money, deputies with badges, and a county determined to take what was not theirs.

She had only her voice, her petitions, and her courage.

For that, she was murdered.

Her children, Samuel and Rosie, too young to understand the battle their mother was fighting, were murdered alongside her.

Not because of who they were, but because erasing them meant erasing her line, her defiance, her claim to the land.

In the eyes of those who killed them, it was supposed to be the end of the story, a mother silenced, a family erased, a door nailed shut.

But what they could never have imagined was that time itself would preserve their truth.

That a demolition crew swinging hammers at an old mansion would stumble upon the horror they had hidden.

That the very ropes meant to silence Clara forever would become the evidence that shouted her name louder than she ever could in life.

Justice in the courtroom sense never came.

The men who orchestrated the crime lived out their years, many never facing a day in prison.

The system that failed Clara in 1972 failed her again in 1994.

But justice took another form.

Justice lived in memory.

In voices that refused to go quiet, in the protests that carried her name, and in the children who grew up knowing that silence was no longer an option.

The memorial stone where the Davenport mansion once stood is not large, just a slab of granite with three names etched into its face.

Clara, Samuel, Rosie.

Beneath them are four words.

They were not runaways.

Simple, final, true.

Visitors come from far away, leaving toys, flowers, and ribbons, standing in silence before a place where the past clawed its way back into the present.

At night, when the wind moves through the empty field where the mansion once stood, some say you can still hear a faint creek like ropes shifting in the rafters.

But those who gather there do not fear it.

They say it is not haunting.

It is remembering, a reminder of what was done and a vow that it will not be forgotten.

The Red Fern story is not just about what happened in 1972.

It is about the truth that injustice leaves behind.

It is about a system that turned its back, about a community that refused to stop whispering, and about how even the darkest secrets cannot stay hidden forever.

Clara fought so her children could keep their land.

She lost that battle in life.

But she won something larger in death.

Her story outlived the silence.

Samuel’s toy truck, Rosy’s ribbon, Clara’s name.

These are no longer relics of loss.

They are symbols of defiance woven into a larger story that will not end.

They tried to erase her.

Instead, they made her unforgettable.

The truth of what happened to the Red Fern family was hidden in plain sight for 22 years.

Their story is a powerful testament to the resilience of a community and the enduring impact of a single act of defiance.

How do you think we can ensure that stories like this are never forgotten and that justice, even if delayed, is not denied? Share your perspective in the comments.

News

Native Dad and Girl Vanished — 14 Years Later An Abandoned Well Reveals the Shocking Truth….

Native Dad and Girl Vanished — 14 Years Later An Abandoned Well Reveals the Shocking Truth…. The high desert of…

Native Family Vanished in 1963 — 39 Years Later A Construction Crew Dug Up A Rusted Oil Drum…

In the summer of 1963, a native family of five climbed into their Chevy sedan on a warm evening in…

An Entire Native Wedding Party Bus Vanished in 1974 — 28 Years Later Hikers Found This In a Revine…

An Entire Native Wedding Party Bus Vanished in 1974 — 28 Years Later Hikers Found This In a Revine… For…

5 Native Brothers Vanished in 1962 — 48 Years Later, Their Wagon Was Found in a Frozen River…

5 Native Brothers Vanished in 1962 — 48 Years Later, Their Wagon Was Found in a Frozen River… The winter…

Three Native Elders Vanished During a Winter Hunt in 1956 — 65 Years Later, a Drone Found This…

Three Native Elders Vanished During a Winter Hunt in 1956 — 65 Years Later, a Drone Found This… In the…

Native Father and His Triplet Girls Vanished — 30 Years Later This Was Found in an Abandoned Mine…

They were last seen alive on a dirt road that cut through the red canyons of northern New Mexico. Their…

End of content

No more pages to load