An Entire Native Wedding Party Bus Vanished in 1974 — 28 Years Later Hikers Found This In a Revine…

For nearly three decades, an entire wedding party from a native community was simply gone.

No funerals, no graves, just silence.

In the summer of 1974, they boarded a yellow bus decorated with ribbons and cedar sprigs headed toward the town of Aoyo Falls for a long- aaited wedding.

47 souls, children, mothers, elders, vanished on a mountain road.

Officials told the families it was just a landslide, just bad luck.

No wreckage, no investigation, only rumors and fear.

Then in 2002, two hikers exploring Raven Ridge stumbled upon something unimaginable in a sealed ravine.

A rusted bus wedged between boulders like a coffin.

Inside, the truth had been waiting.

scratched into the glass beside the driver’s seat.

A single chilling message.

What investigators uncovered next revealed this was never an accident.

It was a cover up.

A conspiracy so deep it silenced an entire generation until the mountain itself gave up its secret.

It was the summer of 1974 in northern New Mexico when a yellow charter bus rolled out of Red Mesa Reservation carrying 47 passengers.

They were dressed in their finest clothes carrying drums, bead work, and food packed for a celebration.

The bus was bound for the small town of Aoyo Falls, where a long- aaited wedding was to be held between two families who had been separated by years of government relocation policies.

For the native community, this wasn’t just a marriage.

It was a reunion, a chance to sing their songs openly, to remind themselves that joy still belonged to them despite everything history had taken.

On board were children giggling at the back.

elders humming old chants, mothers holding infants in their laps.

The bride’s family had decorated the seats with ribbons and cedar sprigs.

The groom’s cousins carried gifts, baskets, blankets, jars of honey.

The bus driver, a quiet man named Raymond Cutter, was not from the reservation, but had driven for the school district for years.

People trusted him.

At 3:45 p.m.on June 12th, the bus pulled away from the dusty school lot and disappeared into the winding mountain road that led north.

It was supposed to be a trip of less than 2 hours, but they never arrived.

By nightfall, families gathered at a Royal Falls Community Center, waiting for the sound of that bus.

Lanterns burned down to stubs.

The band stopped tuning their instruments.

Midnight came and still nothing.

At dawn, a local priest walked into the hall with county deputies behind him.

His words were short, rehearsed.

There has been a landslide in the canyon.

We believe no one survived.

He offered prayers, but not details.

No bodies were recovered.

No wreckage was shown.

Within a week, the county closed the narrow mountain pass entirely, citing safety hazards.

And just like that, the story of 47 missing men, women, and children was reduced to a footnote.

The families didn’t believe it.

How could they? They searched for weeks, hiking trails, combing the forests.

But each time they reported something, officials shut them down.

Helicopters never came.

Newspaper coverage was barely a column buried between farm reports and ads.

The wedding that was supposed to unite two families instead became a curse whispered for generations.

Parents told their children not to ask questions.

Grandmothers lit candles for the dead even though no graves existed.

And then came the silence.

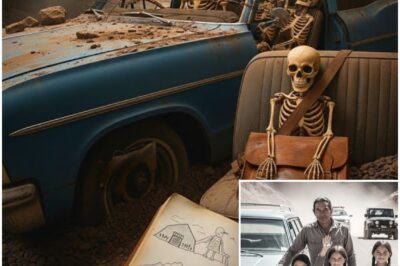

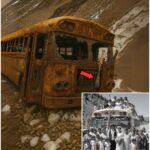

For 28 years, the mountain kept its secret until the spring of 2002 when two hikers mapping old trails near Raven Ridge stumbled upon something metallic in the undergrowth of a ravine that had been sealed by rockfall decades earlier.

At first, they thought it was scrap iron, but when sunlight hit the surface, the outline became undeniable.

The frame of a full-sized bus, crumpled but intact, wedged deep between boulders like a coffin.

Authorities swarmed the site.

Forensic teams repelled down ropes, carefully peeling back rusted doors.

Inside, they found a scene frozen in time.

Skeletons still in wedding clothes.

A rosary clenched in one bony hand.

A child’s doll pressed against a rib cage.

a crushed cake tin.

Frosting long since turned to dust, windows fogged with decades of dirt, but one pane carried words scratched into glass.

They made us turn.

The discovery hit national headlines.

But for the people of Red Mesa, it wasn’t news.

It was confirmation of what they had always suspected.

Their families had not been taken by nature, but by something far more deliberate.

What really happened that night in June 1974? Who gave the order to silence an entire wedding party? And why had the truth been buried beneath stone and silence for nearly three decades? The answers would unravel a conspiracy stretching from the church to the state, from corporate boardrooms to the shadowy roads of the reservation itself.

This was no accident.

It was eraser.

And the deeper investigators dug, the darker the secret became.

For nearly three decades after that bus disappeared, the people of Red Mesa lived with a wound that never closed.

The summer of 1974 became a silence that stretched across generations.

There were no funerals, no graves to visit, no markers to carve names into.

Families had only memories.

Faces pressed to glass.

Laughter on the morning of departure.

Promises whispered about a wedding feast that would never be.

Every year when June came, mothers sat by the window, hoping that somehow a mistake had been made, that the bus would crest the hill and bring their children home.

The official story was simple, almost cruel in its brevity.

a landslide, an act of God.

Nothing could be done.

Authorities told the families that the canyon was unstable, too dangerous to search.

They fenced off the pass, bulldozed over the trail, and within months, the road was gone from new maps.

By the following year, government planners declared the area a restricted geological zone.

In reality, it was an erasure.

The mountain had swallowed not just the bus but the very record of its existence.

But the people remembered.

Mabel Redbird, who lost her sister Clara that night, kept a shoe box filled with letters, photographs, and petitions.

She had been only 20 at the time, just old enough to be left behind with the younger children when the rest of her family boarded the bus.

She remembered the last wave, the red ribbons in her sister’s hair.

Decades later, she could still feel that image carved into her mind.

She wrote letters to newspapers, governors, even to the White House.

Most were never answered.

The ones that did respond told her the same thing.

The case was closed.

The dead should be left in peace.

But how could they be left in peace when they had never been found? Throughout the 1980s, the families tried to organize searches of their own.

Men hiked through canyons with lanterns.

Women carried food to sustain them for days.

They found traces now and then, a scrap of fabric, a rusted piece of metal, but each time they reported it, county deputies arrived first and blocked the site.

They were told they were trespassing, that they risked jail time if they didn’t leave.

Slowly, the elders began to whisper that something larger was at play, something that reached beyond bad weather or tragic chance.

By the early 1990s, the story of the vanished wedding bus was little more than a ghost tale to outsiders.

Local schools didn’t mention it.

Churches never spoke of it.

When outsiders asked about the reservation, they were told only of poverty and unemployment.

Never of the 47 souls stolen in one night.

But inside Red Mesa homes, photographs stayed pinned to walls.

Names were spoken over evening fires and songs of mourning replaced the wedding songs that had been silenced.

Children grew up hearing fragments, warnings from grandparents, whispered fears that the mountain takes what it wants.

Some believed it was superstition.

Others believed it was punishment for speaking their own language, for resisting.

The truth was heavier, but no one dared to say it aloud.

Not yet.

What haunted the families most was not knowing.

Without answers, the imagination filled in the silence with horrors.

Were their children trapped? Were they alive somewhere? Were they killed? Every theory lived in the dark, unanswered and unresolved.

And so the silence became generational.

Parents died without closure.

Siblings grew old with only fading memories of laughter.

And the wedding that was supposed to bind two families became a curse spoken in half sentences, a pain carried like a hidden scar.

Then in the spring of 2002, when the bus was finally found at the bottom of Raven Ridge Ravine, all of that silence cracked open.

The discovery made headlines, but for the families, it was salt in an open wound.

They had begged for a search in 1974.

They had begged again in 1984, in 1990, and 1995.

Each time they were told there was nothing to find.

Now, suddenly, a rusted coffin full of bones had been unearthed.

And the officials acted as if it were a shocking surprise.

But the families weren’t surprised.

They were furious.

Because the truth was clear.

If the bus could be found now, it could have been found then.

And the fact that it wasn’t meant only one thing, no one had ever truly looked.

The silence had not been an accident.

It had been deliberate.

The spring of 2002 was wet and restless in northern New Mexico.

Rains had swollen the rivers and hikers began venturing into canyons that had been closed off for decades.

Two of them, an amateur geologist named Kevin Morales and his friend, a history teacher named Sarah Lane, set out to map forgotten trails near Raven Ridge.

They weren’t looking for mysteries.

They were simply chasing wild flowers in the promise of old rock formations.

But fate led them into a ravine that hadn’t been touched by human hands in years.

The path was treacherous, blocked by fallen boulders and twisted pines.

At one point, Sarah slipped, catching herself against a stone.

And when she looked up, sunlight reflected off something unnatural.

At first, it seemed like scrap metal buried in moss.

But as they cleared branches away, the shape began to emerge.

Long, rectangular, unmistakable.

A bus half swallowed by the earth, its windows shattered, its frame rusted but intact.

They froze.

Everyone in the region had heard whispers of the wedding bus, but most dismissed it as folklore.

Yet, here it was, lying like a tomb at the bottom of the ravine.

Kevin dialed 911 with shaking hands.

Within hours, the canyon filled with law enforcement, flood lights, and television crews.

Helicopters circled overhead, turning the forgotten gulch into the center of national attention.

When the doors of the bus were pried open, a rush of stale air poured out.

A smell of rust, mold, and something heavier, something that made even hardened deputies cover their mouths.

Inside, rows of skeletons sat where passengers once had, their bones fused with decaying seats.

Some still wore fragments of wedding clothes, lace veils clinging to skulls, buttons sewn to scraps of fabric.

One small skeleton leaned sideways, clutching a porcelain doll whose cracked face stared outward.

In another seat, a woman’s armbbone was wrapped around the tiny frame of an infant.

Jewelry glinted faintly.

Turquoise rings, beaded earrings, mute echoes of a celebration that had never happened.

And then came the most chilling discovery.

On the window beside the driver’s seat, etched into glass by desperate fingers, were the words, “They made us turn.

” The phrase sent shivers through everyone who saw it.

Deputies exchanged uneasy looks.

Forensic experts photographed it over and over.

Who was they? Why had the bus turned? And if this had been an accident, why would someone leave behind such a message? Over the following days, investigators retrieved dozens of haunting relics.

A crushed wedding cake tin, the frosting long turned to dust, handpainted drums split by moisture, a rosary still looped around a skeletal hand.

And beneath one seat, a rusted revolver, empty, its cylinder spun.

Autopsies confirmed what families had always feared.

Not everyone died on impact.

Several skeletons showed fractures consistent with restraints, wrists broken in ways that suggested force.

A few skulls bore marks that could not be explained by falling rock.

Someone had lived long enough to carve those words into the glass.

News outlets pounced on the story, running headlines like lost wedding bus discovered after 28 years and skeletons of celebration found in mountain tomb.

But behind the sensational coverage was an undercurrent of dread.

Officials could no longer claim this was just a natural landslide.

Something else had happened on that road in June 1974.

Something human, something deliberate.

For the families of Red Mesa, the discovery was not closure.

It was an indictment.

They remembered the night when deputies told them to stop searching.

When the canyon was fenced off, when maps were altered, now the proof was rusting in front of them.

Their loved ones had been silenced, not by accident, but by choice.

And as investigators began piecing together what little evidence remained.

Rumors spread like wildfire.

Some said the bus had been forced off the road by armed men.

Others whispered that local authorities had been bribed to keep it quiet.

And still others believed it was a government experiment gone wrong.

A test of relocation policies taken to their darkest extreme.

But no matter the theory, one thing became clear.

The truth had been buried deliberately for nearly three decades, and whoever had buried it might still be alive.

The question was, how much longer could they keep the rest of the story hidden? The discovery of the bus should have brought answers.

Instead, it only deepened the shadows.

Within days of the wreckage being found, national media swarmed Raven Ridge.

Cameras broadcasting the rusted coffin of steel across every living room in America.

Anchors spoke with solemn tones, describing a tragic accident that had finally come to light after 28 years.

But on the reservation, no one was buying that narrative.

Not anymore.

Families who had begged for searches in 1974 crowded outside the county courthouse.

They held up photographs of the dead, smiling bridesmaids, laughing children, stern but proud grandfathers.

They shouted the same question into the microphones.

Why did it take 28 years? Why did no one look? Officials dodged, repeating the same line.

The canyon was unsafe.

The bus was buried by landslides, but reporters who had seen the wreck themselves knew better.

The bus was intact.

The ravine was shallow enough to hike.

It had been hidden, not lost.

The first cracks in the official story appeared when forensic teams quietly admitted details that didn’t match an accident.

Several bodies had injuries inconsistent with the crash.

fractures that suggested restraints, blunt force trauma that looked like beatings.

The revolver found under a seat was old but functional, its fingerprints long gone.

Most disturbing of all was the message carved into the glass.

They made us turn.

It became a phrase repeated on every headline, every late night talk show, every whispered conversation on the reservation.

Who were they? The FBI announced an inquiry, though few trusted it.

For decades, federal agents had ignored native pleas for help.

Why would this time be any different? But the media pressure was relentless, and soon a task force was established, combing through old county files, interviewing survivors families, reconstructing the night of June 12th, 1974.

The timeline was haunting in its simplicity.

The bus left Red Mesa School at 3:45 p.

m.

It should have arrived in Aoyo Falls by 6:00, but no one ever saw it cross the county line.

Witnesses reported hearing gunshots in the mountains around dusk, though deputies dismissed them as hunters.

A gas station attendant swore he saw a yellow bus stopped at the edge of the pass surrounded by two police cruisers, but his statement vanished from the original reports.

Now, 30 years later, his memory had not.

As these testimonies resurfaced, a darker picture began to form.

The wedding bus had not been lost by chance.

It had been stopped and forced.

Meanwhile, tensions boiled in Red Mesa.

For the younger generation, who had grown up with only whispers of the vanished bus, the discovery became a rallying cry.

They marched outside federal buildings, demanding justice, carrying banners that read, “We remember our dead.

Elders wept in silence, holding each other as helicopters hovered overhead, reminding them of the very night they were silenced.

Then came the leaks.

An investigative journalist named David Hail obtained sealed documents from a county clerk who had kept copies out of fear.

They revealed that in 1974, just weeks before the disappearance, a mining company had secured drilling rights in the same mountain pass.

The wedding bus had taken that very road on the night it vanished, and the families who had been fighting relocation orders were the most vocal opponents of the project.

It wasn’t just a wedding bus.

It was 47 voices of resistance.

The implication was chilling.

If the bus was forced off the road, if the people were silenced, then it wasn’t random tragedy.

It was a message, a warning to others who dared to stand against the powers that carved up their land.

And so the question grew louder, impossible to ignore.

Who ordered the bus to vanish? The answer would not come easily because those who had orchestrated the silence in 1974 still walked the corridors of power and they had no intention of letting the truth surface now.

By midsummer of 2002, the wreck of the wedding bus was no longer just a discovery.

It was a storm.

Every major network had stationed reporters outside Red Mesa.

Families were interviewed on live television, their grief raw, their anger sharper than ever.

But as the spotlight grew, so did the resistance from those in power.

Local officials tried to paint the wreck as the tragic result of a driver’s error.

The road was dangerous, the sheriff announced in one press conference, his voice flat.

The driver must have swerved to avoid a rockfall.

But reporters pushed back.

Then why was the bus found far off the marked route? Why was the driver’s window carved with they made us turn? The sheriff had no answer.

Cameras caught his hands shaking as he shuffled his papers.

Behind the scenes, pressure was mounting.

An FBI task force began revisiting old testimonies and found files that had been deliberately removed from county archives.

Records of complaints filed by Red Mesa families in 1974 were missing.

The bus driver’s employment file gone.

Even the original police radio logs for the night of June 12th had been erased.

The pattern was undeniable.

Someone had gone to great lengths to bury the truth.

That was when the whistleblowers appeared.

First was Harold Clemens, a retired highway patrol officer.

wrinkled, sick with emphyma, Harold confessed to a journalist that he had been stationed near the canyon the night the bus vanished.

His orders, he said, were not to help, but to block the road.

We were told it was federal business, he rasped.

We saw the bus pulled over by two cruisers.

Next thing we knew, it was gone.

When I asked questions, they told me to shut up or else.

His testimony shook the case wide open.

Days later, another figure stepped forward.

An ex secretary from the county commissioner’s office.

She produced copies of memos she had smuggled out in the mid 1970s, terrified but unable to forget.

One memo referred to the Red Mesa relocation problem and necessary enforcement measures.

Another detailed a meeting between mining executives and county officials just one week before the bus disappeared.

Suddenly, the story shifted from mystery to conspiracy.

The implication was horrifying.

The bus had been stopped intentionally, its passengers silenced because they stood in the way of corporate and government interests.

On the reservation, grief turned into fury.

Younger activists spray painted justice for the 47 across highways.

Vigils turned into marches.

Families demanded exumations, independent autopsies, and criminal charges.

For the first time, the government seemed cornered.

But as pressure built, strange things began happening.

Witnesses recanted statements under sudden illness.

Harold Clemens died within weeks of his confession.

His oxygen tank mysteriously malfunctioning.

The ex- secretary’s home was broken into, her files stolen, though nothing else was touched.

The message was clear.

Someone was still watching.

Someone wanted the truth buried, just as it had been in 1974.

Still, the cracks in the wall of silence were spreading.

Every new document, every whispered testimony, every protest made it harder to hold the lie together.

The families were no longer powerless.

They had the nation’s eyes on them.

And with that spotlight came a question that could no longer be ignored.

If this was murder and not accident, who had blood on their hands? The answer, the family suspected, was closer than anyone dared imagine.

By autumn of 2002, the discovery of the wedding bus had grown into a national scandal.

News anchors no longer called it an accident.

They called it what had increasingly appeared to be a cover up.

Congressional representatives began demanding hearings.

Senators gave statements about historic injustices.

But on the ground in Red Mesa, no one was interested in polite words.

They wanted the truth, names, charges, accountability.

The FBI task force ordered a second forensic examination of the remains.

Independent specialists were brought in from universities, anthropologists, trauma experts, even military pathologists.

What they uncovered only darkened the mystery.

Several skeletons, including those of women and children, showed signs of paramortem injuries.

Wounds inflicted not by the crash, but afterward.

Bone fractures in wrists and ankles suggested binding.

Some skulls had depressions consistent with blunt weapons, not falling debris.

Uh, even more disturbing was the revelation that a few victims had not died instantly.

Forensic soil analysis revealed faint traces of ash inside the bus, remnants of small fires, as though someone had tried to burn cloth for warmth.

Carbon dating suggested that at least some passengers may have survived for days inside the ravine before succumbing to exposure or something far worse.

That possibility ignited public outrage.

Headlines screamed, “Wedding party may have lived days after crash.

” Talk shows debated whether rescue had been deliberately withheld.

Families collapsed at press conferences, sobbing as they imagined their loved ones, freezing, praying, waiting for help that never came.

And then another bombshell dropped.

A forgotten storage room in the county archives was uncovered by a junior clerk.

Inside, stacked beneath moldy boxes, were realto-real police dispatch tapes from the summer of 1974.

The original logs may have been erased, but the audio recordings had survived.

When technicians restored them, the voices were unmistakable.

On June 12th, 8:07 p.

m.

, a deputy radioed in, “We’ve got the bus stopped on Raven Pass, awaiting instructions.

” A pause.

static.

Then another voice, calm and authoritative.

Proceed with diversion.

Do not let them reach a royal falls.

Repeat, do not let them through.

The room where those tapes were first played went silent.

Even seasoned FBI agents exchanged grim looks.

The orders hadn’t come from a drunk deputy or a lone rogue cop.

The voice was too high ranking.

Someone with authority had given the command.

But who? Experts began analyzing the voice, comparing it to archived recordings of local and federal officials from the era.

Whispers circulated that it matched a county commissioner who later became a state senator, still alive, still powerful.

Others speculated it was a Bureau of Indian Affairs officer who had overseen relocation policies.

Whoever it was, they had vanished into the folds of respectability while 47 souls were left to rot at the bottom of a ravine.

The release of the tapes triggered nationwide fury.

Protests spread from New Mexico to Washington DC where demonstrators camped on the National Mall holding candles, chanting the names of the dead.

The words etched into the bus window.

They made us turn, became a rallying cry, painted on banners, tattooed on arms, whispered like a prayer.

But with every surge of truth came resistance.

Federal officials downplayed the recordings, suggesting they might be misinterpreted.

The mining company, now a multinational giant, released statements calling the allegations unfounded conspiracy theories.

And in Red Mesa, activists began noticing unmarked SUVs idling near their homes, cameras pointed, strangers knocking at doors with polite smiles, and too many questions.

It was clear the same forces that buried the bus in 1974 were not done.

They had survived the decades, just like the secret itself, and they would fight to keep the final truth hidden.

Still, the families pressed forward.

For the first time in nearly three decades, they felt the scales tipping in their favor.

The ghosts of that wedding night were no longer silent.

They were speaking through the evidence, through the relics, through the recordings, and their voices demanded justice.

By early 2003, the storm that began in Red Mesa had reached the highest halls of power.

Pressure from journalists, native activists, and human rights organizations forced Congress to open hearings on what was now called the wedding bus case.

For the first time in 29 years, officials were summoned to Washington to answer questions they had spent half a lifetime avoiding.

The hearings were broadcast live.

Millions tuned in as families of the victims, many wearing traditional dress, sat shouldertoshoulder in the gallery.

Their faces were lined with grief but hardened with resolve.

When the chairwoman struck her gavvel, the room fell silent.

The first witnesses were forensic experts who testified about the disturbing injuries on the victim’s remains.

They described fractures consistent with restraints, blows inconsistent with an accident, and evidence of survival long after the supposed crash.

Each word painted a picture not of a tragic mistake, but of cruelty.

Mothers in the gallery wept quietly, their tears echoing louder than the testimony itself.

Then came the bombshell, the dispatch tapes.

Technicians replayed the chilling voice for all to hear.

Proceed with diversion.

Do not let them through.

The gallery gasped.

Some families clutched each other, whispering prayers.

Senators leaned forward, visibly shaken.

But the real turning point came when journalists uncovered a chain of connections between the county government of 1974 and a powerful mining conglomerate that operated in the mountains.

Old contracts revealed that the company had pushed aggressively for drilling rights in the very canyon where the bus was found.

letters showed county commissioners promising swift resolution to Red Mesa interference.

The relocation of families was not an accident of policy.

It was a calculated strategy and the wedding party had been the most vocal opposition.

The hearings grew tense as surviving officials were questioned.

Some feigned ignorance, claiming records had been lost.

Others grew defensive, repeating the same line.

I don’t recall.

But one man, now elderly and frail, slipped.

A retired sheriff admitted under questioning that deputies had been ordered to stop the bus that night, though he insisted he did not know why.

His voice cracked as he said, “We thought it was routine.

We didn’t know it meant that.

” The gallery erupted.

Families shouted from the back, demanding his arrest.

Security rushed to quiet the chaos, but the message was clear.

The truth was clawing its way to the surface.

Meanwhile, outside the hearing chambers, the story took on a life of its own.

Protests flooded city streets.

College students marched with signs reading, “Justice for the 47.

” Celebrities wore pins carved with feathers dedicating award speeches to the victims.

Documentaries aired nightly, replaying the haunting image of the rusted bus pulled from the ravine, its windows shattered but its secrets intact.

And yet, for every surge of truth, there was resistance.

Senators from mining states attempted to derail the hearings, calling them witch hunts.

Corporate lobbyists flooded the capital, whispering into ears, promising donations in exchange for silence.

Some news outlets owned by conglomerates with ties to the mining company suddenly shifted their tone, calling the case unproven conspiracy.

The families knew what this meant.

The fight was far from over.

The machine that had silenced their loved ones in 1974 was still alive, powerful, and determined.

But this time, they were not alone.

As hearings adjourned late into the night, the chairwoman issued a statement that echoed through the nation.

The evidence presented today suggests not just negligence, but intent.

This committee will not rest until accountability is achieved.

For the first time, the families felt a flicker of hope.

Justice, though distant, was finally within sight.

But hope can be dangerous.

Because in the shadows beyond the cameras, the same forces that orchestrated the disappearance decades ago were watching closely, ready to strike again to ensure their secrets stayed buried.

The hearings had cracked the wall of silence.

But what came next proved that the shadow behind the wedding bus was not a relic of the past.

It was alive, ruthless, and willing to kill again.

Just weeks after the dispatch tapes were played before Congress, tragedy struck.

Harold Clemens, the retired highway patrol officer, whose testimony had first confirmed the bus was stopped intentionally, was found dead in his small Albuquerque apartment.

Official reports listed it as a heart attack, but neighbors told reporters they’d seen a black SUV idling near his building the night before, and the lock on his door looked freshly tampered.

His daughter broke down on live television.

My father lived with guilt for decades, and when he finally spoke the truth, they silenced him.

He was not the only one.

The ex secretary who had leaked corporate memos about Red Mesa relocation vanished without a trace.

Her home stood eerily untouched.

Dinner half prepared on the table as though she had simply been lifted from her life.

Police issued statements about a possible runaway, but no one believed them.

Activists called it what it was, a disappearance to erase a witness.

Inside the hearings, tension escalated.

Senators received anonymous threats.

Packages containing bullets, notes scrolled with stop digging.

One young staffer was hit by a mysterious car while jogging near Capitol Hill.

He survived, but his leg was shattered.

Whispers spread through the corridors.

The same machine that crushed a wedding party in 1974 was flexing its muscle again, reminding everyone that secrets had a price.

Meanwhile, back in Red Mesa, families noticed strangers lurking at vigils.

Men with military haircuts, silent, snapping photographs.

Elders warned younger activists to walk in groups, never alone.

Some were followed home at night.

The air was heavy with the same fear that had haunted them for nearly three decades.

And then came the sabotage.

The FBI’s forensic labs, which had been carefully re-examining bones and soil samples, suffered a sudden fire.

Entire shelves of evidence charred.

Officially, it was ruled an electrical fault, but insiders whispered it was arson.

Reporters demanded answers.

How can the nation’s most secure labs burn down without sprinklers engaging? But officials dodged, evaded, deflected.

Once again, truth had gone up in smoke.

Yet the conspiracy’s grip was slipping.

For every silenced witness, another found courage.

For every destroyed file, a copy surfaced.

One investigative journalist unearthed a forgotten land deed showing that just months after the wedding party vanished, mining rights were sold to the very conglomerate accused of pushing for relocation.

Another reporter traced campaign donations that tied sitting senators back to those same companies.

The web was vast, sticky, undeniable.

The families of Red Mesa refused to back down.

They held nightly vigils at the sight of the ravine, candles glowing like stars across the canyon walls.

Children sang the names of the lost, voices rising against the silence that had been forced on their people.

The words carved into the bus.

They made us turn, were repeated like scripture.

Still, as hope grew, so did danger.

One activist leader’s car was run off a desert road.

He barely survived, crawling from the wreckage with broken ribs.

Anonymous calls warned mothers to stop marching or their children would end up like the bus.

It was as if history itself was replaying.

The same ruthless playbook from 1974 now turned against those demanding justice.

The conspiracy had teeth and it was biting back.

But something was different this time.

Unlike the wedding party, these voices were not isolated, not powerless.

The nation was watching.

Cameras rolled.

Millions tweeted, protested, demanded.

The shadows could still kill, but they could no longer kill in silence.

And in that widening crack between fear and defiance, the truth was preparing to break free.

By the spring of 2003, the case had become a national obsession.

What began as a haunting discovery in a frozen ravine was now a battle between truth and a shadowy machine that had ruled through fear for decades.

The families of the victims were no longer alone.

They had lawyers, journalists, and millions of voices behind them.

And yet, the closer they came to the heart of the conspiracy, the more dangerous the path became.

The breakthrough arrived from an unlikely place.

Deep in the archives of a regional newspaper, a young reporter uncovered a dusty cardboard box labeled unpaid obits, 1974.

Inside were handwritten drafts of obituary notices never published.

Among them was one that froze the blood of everyone who read it.

It named several members of the vanished wedding party as deceased the very day after they disappeared.

Cause of death: vehicle accident on Raven Pass.

But how could obituaries be written before the bus was ever discovered? The implication was chilling.

Officials knew the fate of the passengers long before they claimed the bus had vanished.

The obits were proof that the story had been scripted.

The tragedy predetermined, the cover up orchestrated from the very beginning.

Around the same time, another discovery sent shock waves.

A retired nurse, frail and in her late8s, came forward.

She confessed that in June of 1974, she’d been ordered to a makeshift triage station inside an abandoned ranger cabin near Raven Pass.

There, she treated several native women and children brought in with hypothermia and broken bones.

They kept crying for their families, she whispered, her eyes filling with tears during a taped deposition.

I was told not to ask questions.

2 days later, the cabin was empty.

I never saw them again.

Her testimony confirmed the darkest suspicions that some passengers had survived the crash and were deliberately detained, then disappeared.

When asked who gave the orders, her voice trembled.

Men in uniforms, but not our local police.

They had federal badges.

The revelation tore the hearings wide open.

If survivors had been taken alive, where had they gone? Why had no records ever surfaced? And who authorized their removal? Investigators pieced together a damning picture.

Mining company records showed a surge of security expenses logged in June 1974.

Government contracts linked those expenses to private contractors hired for relocation enforcement.

The very same contractors who decades later had morphed into one of the nation’s most powerful defense firms.

And then came the voice.

After months of analysis, experts confirmed what many had feared.

The order captured on the dispatch tapes matched the voice of Senator Wallace Grant, a towering political figure whose career had spanned four decades.

In 1974, he had been a county commissioner with direct ties to the mining conglomerate.

Now he sat in one of the most powerful seats in Washington, untouchable, revered, a kingmaker.

When reporters finally confronted him outside his gated estate, he smiled coldly, brushed past microphones, and muttered only four words.

You people know nothing.

But the nation did know, and what they knew was enough to shake the foundation of trust in both government and corporate power.

Still, despite all the evidence, the families feared justice might once again slip away.

Trials were stalled by procedural delays.

Evidence kept vanishing.

Witnesses were harassed, threatened, or found dead.

It seemed the conspiracy would strangle the truth before it could fully breathe until one final shock.

A construction crew clearing old tunnels near Raven Pass uncovered a hidden chamber carved into the mountainside.

Inside were rusted handcuffs, children’s shoes, and scraps of fabric embroidered with wedding patterns.

Experts confirmed they belonged to members of the missing party.

The cavern had been a holding place, a prison where survivors were kept before they disappeared forever.

The discovery ignited the nation.

Candlelight vigils turned into massive marches.

Senators who had once resisted the hearings now broke ranks calling for full prosecution.

And in Red Mesa, the family stood at the edge of the canyon where their loved ones had vanished, holding photographs high above their heads.

The shadows were cornered.

The final reckoning was near.

But as the truth closed in, so did the danger.

for those who sought to expose it were now closer than ever to the men who had silenced 47 souls beneath the desert stars.

The storm reached its peak in late 2003.

By now, the wedding bus case was no longer just a local tragedy.

It had become a symbol of systemic betrayal, a wound that exposed how greed and power could swallow the innocent whole.

The nation demanded justice, and for the first time in nearly three decades, it seemed the guilty might finally face the light.

Federal prosecutors, armed with the cavern evidence, the obituaries, and the nurse’s testimony, moved to indict Senator Wallace Grant and several retired officials for conspiracy, obstruction, and crimes against humanity.

Cameras captured the moment agents arrived at Grant’s estate.

The once untouchable figure, a kingmaker in Washington, was led away in handcuffs.

The image ricocheted around the world, proof that even giants could fall.

But the celebration was short-lived.

Weeks before the trial, Wallace Grant was found dead in his holding cell.

The official report claimed suicide.

His guards swore he had been despondent, but few believed it.

The timing was too neat, the silence too convenient.

With him gone, many feared the truth had died as well.

Sealed forever by those still lurking in the shadows.

Yet the families refused to let it end that way.

They pressed on, filing civil suits, forcing disclosures, dragging every document into the open.

Bit by bit, the machinery of secrecy unraveled.

Memos confirmed the relocation orders.

Bank transfers traced the bribes.

Maps outlined planned drilling sites directly where Red Mesa families had lived.

It was all there, hiding in plain sight.

In 2004, the government finally issued a formal apology, acknowledging the complicity of officials and corporate partners in the tragedy.

Compensation funds were established, though no amount of money could erase 30 years of silence.

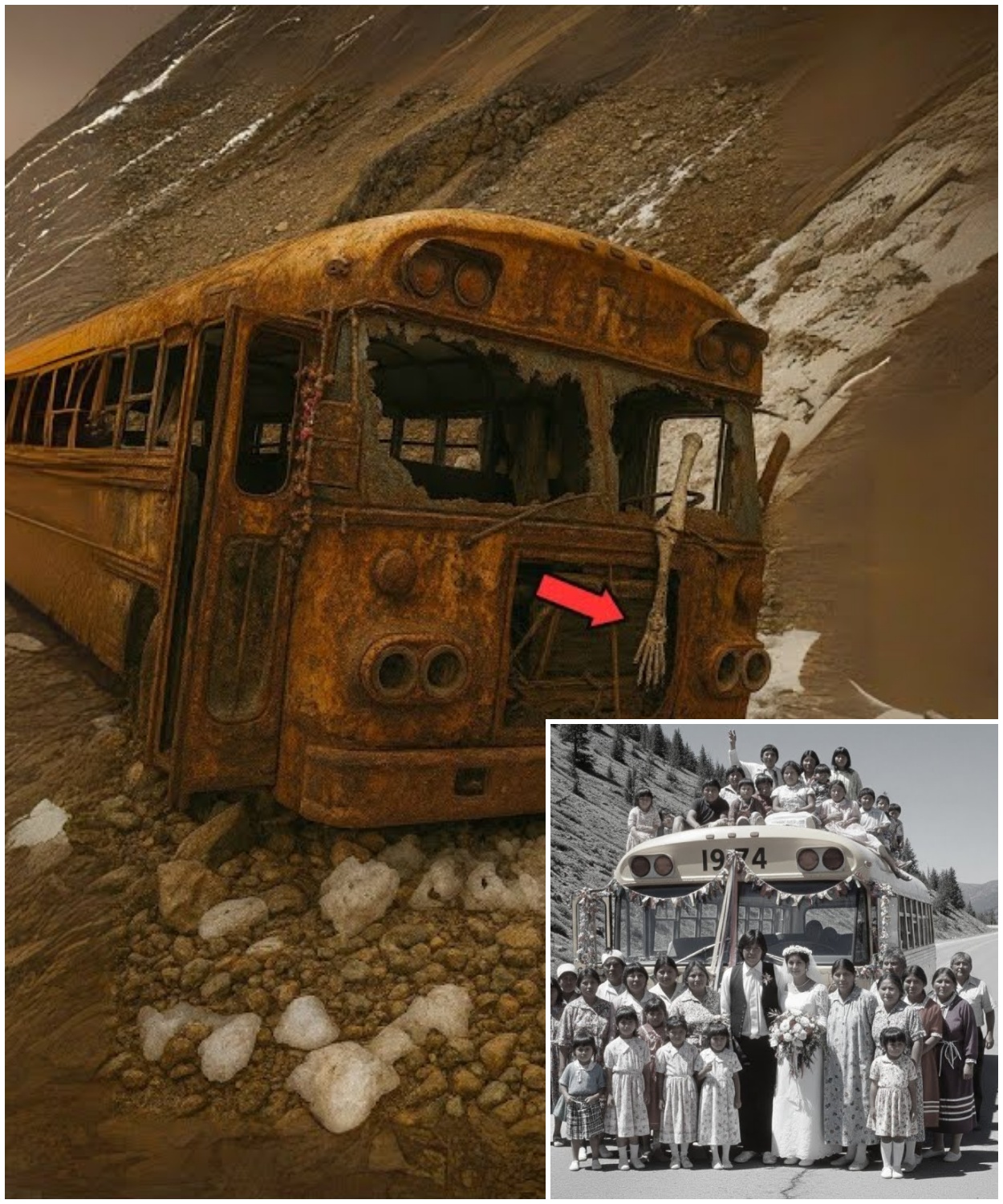

The bus itself, once pulled from the ravine, was preserved and placed in a memorial museum built on Red Mesa land.

Its shattered windows, its rusting frame, and the faint carved words, “They made us turn,” stood as a monument to truth.

But justice remained incomplete.

Many of those who signed the orders were dead.

Others escaped punishment through influence and wealth.

Families gathered at the canyon and asked the same question.

If the guilty never stand trial, is this truly justice or just another burial? The final blow came from the mountain itself.

Months after the trial collapsed, hikers discovered a second hidden cavern sealed by rock slides.

Inside were shallow graves, remains of women and children, still wearing fragments of wedding clothes, beads, and feathers.

Forensic teams confirmed the impossible.

They were survivors of the crash, detained and executed years later.

The revelation sent a chill through the nation.

It was no longer just conspiracy.

It was massacre.

And while the perpetrators were gone or untouchable, the evidence ensured the world would never again forget what had been done.

On the 30th anniversary of the tragedy, the descendants of the wedding party gathered on Red Mesa.

They lit torches, chanting the names of each victim.

Drums echoed across the desert, rising toward the stars.

An elder stepped forward, voice steady.

They tried to bury our families in silence, but tonight their voices rise higher than the mountains.

The crowd lifted their torches, flames dancing in the night.

The canyon glowed with light, as if the ancestors themselves had returned.

The story of the wedding bus had ended, but its echo had only just begun.

It was no longer a mystery buried in a ravine.

It was a warning carved into history.

Truth can be delayed, silenced, even murdered, but it cannot be erased.

News

Native Dad and Girl Vanished — 14 Years Later An Abandoned Well Reveals the Shocking Truth….

Native Dad and Girl Vanished — 14 Years Later An Abandoned Well Reveals the Shocking Truth…. The high desert of…

Native Family Vanished in 1963 — 39 Years Later A Construction Crew Dug Up A Rusted Oil Drum…

In the summer of 1963, a native family of five climbed into their Chevy sedan on a warm evening in…

5 Native Brothers Vanished in 1962 — 48 Years Later, Their Wagon Was Found in a Frozen River…

5 Native Brothers Vanished in 1962 — 48 Years Later, Their Wagon Was Found in a Frozen River… The winter…

Three Native Elders Vanished During a Winter Hunt in 1956 — 65 Years Later, a Drone Found This…

Three Native Elders Vanished During a Winter Hunt in 1956 — 65 Years Later, a Drone Found This… In the…

A Native Family Vanished in 1972 — 22 Years Later This Was Found Hanging In An Abandoned Mansion…

In the summer of 1972, a native mother and her two young children vanished from their small farmhouse in northern…

Native Father and His Triplet Girls Vanished — 30 Years Later This Was Found in an Abandoned Mine…

They were last seen alive on a dirt road that cut through the red canyons of northern New Mexico. Their…

End of content

No more pages to load