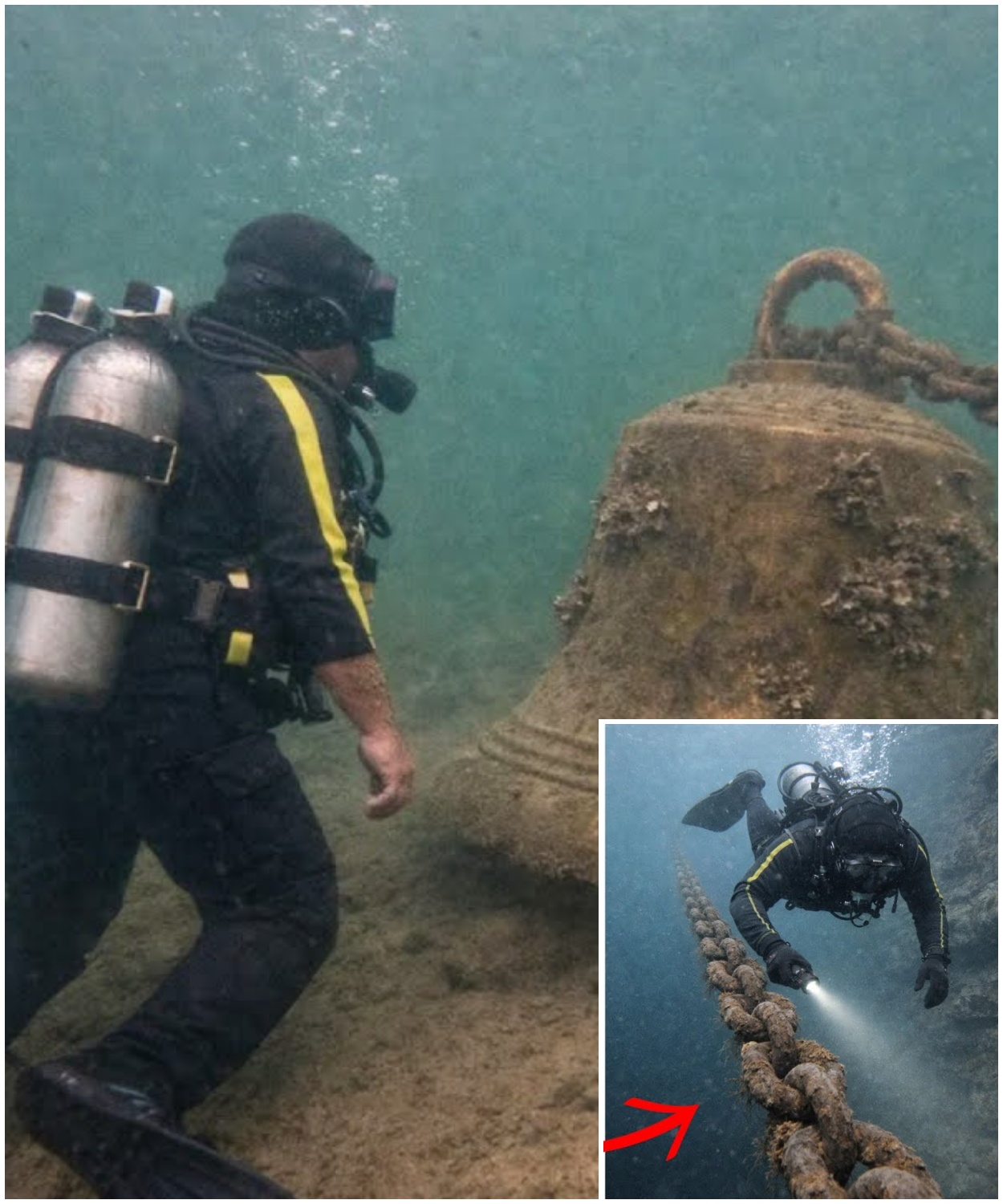

A salvaged diver mapping a remote lake discovered a massive church bell resting on the bottom.

But when he followed the heavy chain welded to it down into the dark abyss, the terrifying sight waiting at the end of the line made him surface in a panic and call the authorities immediately.

The sonar pulse was the only heartbeat in the silence of the Austrian Alps.

A rhythmic digital ping that sliced through the freezing black water of Lake Vinster Sea.

Gerrard Harris sat hunched over the monitor of his small survey boat, the Nautilus, rubbing grit from eyes that hadn’t seen a full night’s sleep in weeks.

Outside the wheelhouse, the wind was picking up, carrying the biting scent of pine and impending snow from the Docstein Mountains.

The lake was a mirror of obsidian, reflecting the jagged peaks that walled it in like the rim of a chalice.

To the locals, this water was cursed, a dark eye that swallowed light and never gave it back.

To Gerard, it was just a job.

a topographical survey for the regional water authority.

A mundane task of mapping silt depths and submerged timber to pay off the debts that were slowly drowning his salvage business.

He was 42, though the salt and sun of a life spent at sea made him look 50.

His equipment stacked neatly on the aft deck was a testament to his current financial state.

Reliable, but aging.

He didn’t have the closed circuit rebreathers or mixed gas computers of the high-end exploration teams.

He dove old school with a twin set of yellow steel tanks and a dry suit that had seen better days.

“Come on,” he muttered to the screen, watching the scrolling topographical lines of the lake bed.

“Give me a flat bottom so I can go home.

” The lake floor at this sector was supposed to be a smooth basin of glacial silt, sitting at a depth of roughly 60 ft before the drop off into the abyss.

But the sonar line, which had been drawing a monotonous flat horizon for the last hour, suddenly spiked.

It wasn’t a jagged rock formation, and it wasn’t the soft, fuzzy return of a waterlogged tree trunk.

It was a hard return, solid, dense, and geometric.

Gerrard leaned in, his breath fogging the cold glass of the monitor.

The anomaly was massive.

It stood about 6 ft off the bottom and was roughly 5 ft wide at the base.

The sonar shadow it cast was long and sharp.

Nature didn’t make perfect cones in the middle of a silt plane.

He cut the engine.

The silence that rushed in was heavy, amplified by the sheer verticality of the mountains around him.

Drifting in the sudden quiet, Gerard marked the GPS coordinates.

It was late afternoon.

The sun was already dipping behind the peaks, casting the lake into a prematurely early twilight.

Smart diving protocol dictated he should mark the spot and return tomorrow with fresh light and a safety diver.

But the bank notices in his glove compartment back at the marina weren’t patient.

If this was a piece of lost logging machinery, or perhaps the wreckage of a small aircraft rumored to have gone down in the ‘9s, the salvage bonus could cover his slip fees for 6 months.

He looked at the twin yellow tanks strapped to the bench.

They were filled with standard air, plenty for a 60- ft bounce dive.

Just a look, he whispered to the empty cabin.

Touch and go.

He stepped out onto the deck.

The cold air bit through his fleece, a warning.

He began the ritual of gearing up, a process that was muscle memory.

After 20 years, he pulled on the thick thermal undergarments, then the black vulcanized rubber of his dry suit.

He checked the seals at his wrists and neck, ensuring they were watertight.

Next came the heavy harness with the twin steel tanks.

He hefted the weight onto his shoulders, the familiar burden settling him, grounding him.

He ran his checks, regulators breathing dry, metallic air, inflator hose connected, dive computer set, knife strapped to his thigh.

Gerard sat on the gunnel, his fins dangling over the black water.

He looked at the sonar screen one last time through the cabin window.

The spike was still there, waiting.

With a deep breath, he purged his regulator and rolled backward into the water.

The shock of the cold was instant, even through the dry suit.

It was a crushing, pressing cold that tried to find any weakness in his insulation.

Gerrard vented the air from his buoyancy wing and began to descend.

The visibility in Lake Finster Sea was deceptive.

The first 10 ft were clear, filled with the dancing particulates of algae, but as he dropped past 30 ft, the light vanished.

The water turned a bruised purple, then a heavy, suffocating green.

It was like descending into liquid emerald.

He switched on his primary canister light.

The beam cut a tight white tunnel through the gloom.

Particles of silt hung suspended in the water, frozen in time.

The only sound was the rhythmic hiss whoosh of his breathing and the bubbles rattling past his ears.

40 ft 50 ft.

He checked his depth gauge.

He was nearing the bottom.

He flared his fins, slowing his descent to avoid kicking up the silt and blinding himself.

The lake bed materialized below him, a moonscape of gray mud rippled by unseen currents.

He scanned the darkness, swinging the light beam back and forth.

Where was it? Then a glint of metal caught the light.

It loomed out of the darkness like a fallen titan.

Gerrard drifted closer, his heart rate spiking not from exertion, but from the sheer unexpected majesty of the object.

It was a bell, a massive bronze church bell.

It was resting on its side, half buried in the silt.

It was far larger than anything he had expected, easily 5 ft tall and weighing tons.

Even coated in a layer of zebra muscles and slime, the bronze had a dull, powerful luster.

Gerrard hovered over it, his light tracing the curve of the metal.

He wiped a gloved hand across the surface, clearing away a patch of algae.

Underneath he saw intricate relief work, angels, vines, and heavy Gothic script that he couldn’t read in the dim light.

what was a cathedral bell doing in the middle of a remote alpine lake.

He swam to the crown of the bell, the loops at the top where it would normally be hung in a tower.

He expected to see a frayed rope or perhaps nothing at all, assuming it had fallen off a transport barge decades ago.

Instead, he found steel.

A heavy industrial chain was attached to the crown.

It wasn’t tied.

It was shackled and welded.

A crude, brutal modification that looked like a scar on the artwork.

The chain was thick, the links the size of his fist, corroded, but intact.

Gerard followed the line of the chain with his light.

It didn’t lie slack on the bottom.

It was pulled taut, stretching away from the bell, hovering a few inches above the silt, leading straight toward the deeper center of the lake.

It looked like a leash.

Curiosity wore with caution.

His computer showed he had plenty of bottom time.

He checked his air pressure.

Good.

He adjusted his buoyancy, lifted himself a few feet off the mud, and began to fine along the length of the chain.

The swim was hypnotic.

The chain was a rusted iron snake leading him further into the dark.

After 50 yards, the lake floor began to change.

The gentle slope disappeared.

The silt dropped away sharply.

He had reached the precipice.

The chain continued over the edge, plunging down into a vertical wall of darkness.

Gerrard shown his light down.

The beam didn’t hit the bottom.

It just illuminated the chain, fading into the blackness, descending into the freezing abyss that the locals claimed was bottomless.

He hovered at the lip of the drop off at 70 ft.

The chain went deeper.

Whatever was at the other end of this tether was heavy enough to keep tons of bronze anchored in place.

A chill that had nothing to do with the water temperature crawled up his spine.

He looked at his pressure gauge again.

He had the gas to go a little deeper, but diving solo over a deep drop off was asking for trouble.

Just to the next shelf, he bargained with himself, just to see where it goes.

He dumped air from his wing and sank over the edge.

The temperature dropped instantly as he passed through a thermocline.

The water clarity improved, stripped of the algae that lived in the shallows, but the darkness was absolute.

He was descending into a void.

At 90 ft, the nitrogen began to whisper to him.

The martini effect, nitrogen narcosis, softened the edges of his vision.

He felt a slight euphoria, a detachment from the danger.

He focused on the chain.

It was his world.

At 100 ft, his light caught a shape below.

The chain ended.

It terminated at a massive concrete block.

A crude, hastily poured anchor sitting on a limestone shelf that jutted out from the cliff face.

But it wasn’t the block that made Gerard’s breath catch in his throat.

It was what lay beyond it.

He swept his light across the shelf.

At first, his narcosis adultled brain couldn’t process the visual data.

He saw round shapes, hundreds of them, piled in chaotic mounds stacked on top of each other, spilling over the edge of the shelf into the deeper dark.

They looked like skulls.

giant smooth skulls.

Panic, primal, and electric surged through him.

He backpedled, his fins churning the water.

He squeezed his eyes shut for a second, forcing his brain to process the image correctly.

Not skulls, not bodies.

He opened his eyes and steadied the beam.

They were bells.

There were hundreds of them.

Church bells of every size, from small handbells to massive bordens like the one in the shallows.

They were piled in a grotesque, silent heap, a mass grave of bronze.

Some were cracked, others pristine.

They lay silent and cold, a graveyard of sound drowned in the deep.

The sheer scale of it was terrifying.

It wasn’t just a shipwreck.

It was a deliberate disposal, a hidden atrocity of culture.

The way they were discarded, heaped like trash, felt violent.

Gerard checked his depth.

110 ft.

He was deep, cold, and alone in a graveyard.

The chain he had followed wasn’t an anchor.

It was a trail marker, or perhaps a mistake.

A bell that had fallen off the pile and dragged itself toward the shallows.

A strange sound vibrated through the water.

A low thrming.

Not a fish, not the bells.

It was a boat engine overhead, but his boat was anchored 100 yards away.

He looked up.

A dark shadow blocked the faint ambient light from the surface.

Paranoia fueled by the nitrogen gripped him.

He didn’t want to be found here.

He didn’t want anyone to know what he had seen.

Not yet.

He initiated his ascent, keeping his light off, rising slowly through the blackwater column, leaving the silent, terrified congregation of bells behind in the dark.

The warmth of the gastur post was a physical shock after the freezing embrace of the lake.

The air inside the tavern was thick with the smell of roasting pork, yeast, and wood smoke.

Gerrard sat in a corner booth nursing a coffee that was half schnops, his hands still trembling slightly.

He hadn’t called the authorities.

Not yet.

He needed to understand what he had found before he surrendered the discovery to the bureaucracy that would inevitably shut him out.

Across the table sat Elena Weiss.

She was a woman of sharp angles and intense intelligence, the curator of the local historical society.

Gerard had worked with her once before on a minor survey of a flooded village.

She was the only person he trusted to value truth over profit.

He slid his tablet across the scratched wooden table.

The footage from his GoPro played on the screen, grainy, green, and shaking, but undeniable.

Elena watched in silence.

When the camera swept over the shelf, the glocken freed Hoff, she gasped, a sound that was half sobb, half reverence.

She reached out and touched the screen as if she could feel the cold bronze.

“My God,” she whispered.

It’s true.

The lost shipment.

What shipment, Elena? Gerard asked, leaning in.

Who threw a thousand bells into the lake? And why is there a chain leading to the shallows? She looked up, her eyes wide behind her glasses.

The Nazis.

Gerard.

In 1941, Gurin issued the decree for the metal spendy, the metal donation.

They stripped the churches of Europe.

Bells were confiscated from Austria, Poland, Czechoslovakia, even Russia.

They were meant to be melted down for what? Casings.

Yubot propellers.

The instruments of God were turned into instruments of death.

She gestured to the screen.

These bells, they were categorized.

Type A, B, C, D.

Type D were the most historically valuable, meant to be preserved for the ultimate victory.

But by 1944, everything was going into the furnace.

The Reich was starving for copper, so they hid them here.

There were rumors, Elena said, tapping the table.

Near the end of the war, a train carrying hundreds of bells vanished.

The resistance claimed they intercepted it.

The Nazis claimed partisans stole it, but no one ever found the metal.

We assumed it was melted down in secret.

She looked at Gerard.

You found the sanctuary.

It doesn’t look like a sanctuary, Gerard muttered.

It looks like a dump site.

And that chain, it was welded.

Someone wanted to find that pile again.

or a deep voice interrupted from the next booth.

Someone wanted to make sure they stayed down.

Gerard and Elena turned.

A man stood up, tall, wearing an expensive woolen coat that looked out of place in the rustic tavern.

He had the weathered face of an outdoorsman, but the manicured hands of a businessman.

“Clouse,” Elena said, her voice dropping to a chill.

Klouse Gruber.

Gerard knew the reputation, a property developer with a sideline in historical acquisition.

He was a treasure hunter who operated in the gray areas of Austrian law, looking for the fabled Nazi gold of Lake Topletits.

“Mr.Harris,” Klouse said, smiling without warmth.

“I heard you were mapping the sector near the cliff.

Nasty currents there.

a man could get into trouble.

“Just mapping silt, Clouse,” Gerard said, closing the cover of his tablet.

“Silt doesn’t make a man shake like that,” Klouse said, nodding at Jerard’s trembling hands.

“You found something.

The lake has secrets, Jared.

Some are worth a fortune.

Copper prices are high.

Historical artifacts on the black market even higher.

It’s municipal property, Gerard said, standing up.

He was shorter than Klouse, but broader in the chest.

It’s lost property, Klouse countered.

Maritime law is tricky in international waters, though we are inland.

But accidents, accidents are simple.

He leaned in closer.

Don’t go back down there, Englishman.

The lake takes what it wants.

Klouse turned and walked out of the tavern, leaving a wake of expensive cologne and menace.

He knows, Elena whispered.

He has spies at the marina.

If he finds those bells, he’ll dynamite the shelf to get them loose.

He’ll destroy history to sell it by the kilogram.

Gerard looked at his hands.

He needed the money.

A finder’s fee for this would be substantial, but looking at the footage at the silent, dignified pile of stolen heritage, he felt a weight that wasn’t financial.

He can’t find them without the coordinates, Gerard said, but he can follow me.

We need proof, Elena said.

We need to know who put them there.

If the Nazis hid them, they are spoils of war.

If the resistance hid them, they are a monument.

We need to find a marker, a manifest, the barge itself.

There was a concrete anchor, Gerard remembered.

It was huge.

I saw marks on it, but I was narked.

I couldn’t read it.

You have to go back, Elena said, gripping his arm.

Before Klouse brings his dredge, you have to find the provenence.

Only then can we get the state to protect the site.

Gerard looked out the window.

Snow was beginning to fall.

Heavy flakes swirling in the street light.

The lake would be churning tomorrow.

I need a surface team.

He said, “I can’t do this alone.

” “I can drive a boat,” Elena said.

“My father was a fisherman.

” Gerrard nodded.

“Meet me at the dock at dawn.

Bring warm clothes.

We’re going to wake the dead.

The dawn was gray and hostile.

The lake was a churning soup of white caps.

Gerard’s survey boat pitched violently as they motored toward the GPS coordinates.

“The weather report said this was coming in tonight.

” Elena shouted over the wind, gripping the wheel.

“Mountains make their own weather!” Gerard yelled back.

He was struggling into his gear on the rolling deck.

The conditions were borderline undiveable, but he had seen Klaus’s sleek black cruiser leaving the harbor ahead of them.

Klouse was watching from a distance, waiting for Gerard to mark the spot.

“I’m going to drop a decoy boy here,” Gerard said, tossing a marker into the water 300 yd off target.

“Let him investigate that.

I’m going down on the reel side.

He checked his twin tanks.

He had overfilled them slightly, giving him extra margin.

He clipped a heavyduty reel to his harness and a lifting bag.

If I find proof, a plaque, a name plate.

I’m sending it up on the lift bag.

He told Elena, “If I’m not up in 40 minutes, you call the Coast Guard.

Do not wait.

” “Gerard,” she said, looking at the black water.

Be careful.

The spirits, they are restless.

Physics is the only spirit down there, Gerard said, though he didn’t quite believe it.

He pulled his mask down and rolled off the boat.

The turbulence on the surface vanished instantly, replaced by the silent rocking surge of the underwater currents.

The visibility was worse today, barely 5 feet.

The storm was stirring up the silt.

He descended the anchor line of his boat, fighting the current that tried to drag him sideways.

He hit the bottom at 60 ft and found the first bell.

It was his lighthouse in the gloom.

He located the chain.

It was vibrating, humming with the energy of the moving water.

He clipped his safety reel to it and began the swim to the drop off.

The journey to the precipice was harder this time.

The cold was more intense.

Biting through his gloves, he reached the edge and dropped over.

Descending into the canyon felt like falling into the mouth of a beast.

He controlled his breathing, forcing himself to stay calm.

In 2, three, out two, three.

He reached the shelf at 100 ft.

The pile of bells loomed out of the darkness, more menacing in the low visibility.

They looked like a landslide of metal waiting to crush him.

Gerrard swam to the concrete anchor block.

He scrubbed the surface with a wire brush he had brought.

Clouds of silt exploded, blinding him for a moment.

He waited for the current to clear it.

He shown his light on the concrete.

There was riding, scratched into the wet cement by a finger or a stick.

80 years ago.

1412 1944.

We’re Schwagen nicked.

We are not silent.

Group Edelvvice.

It wasn’t a Nazi hiding spot.

It was a resistance tomb.

They had hijacked the barge, motored it out here in the dead of winter and sunk it to save the bells from the furnaces.

The chain.

The chain was a hope.

A hope that one day someone would pull them back up.

Gerard pulled out his camera to document the inscription.

This was the proof.

This changed everything.

Suddenly, a violent shutter ran through the water.

A massive boom echoed off the cliff walls.

Gerard was thrown sideways, slamming into the pile of bells.

His regulator was knocked from his mouth.

He scrambled to recover it, purging the water and gasping for air.

Dynamite.

Klouse wasn’t waiting.

He was dropping charges, either to scare Jared or to loosen the silt.

Another explosion closer this time.

The shock wave felt like a punch to the chest.

The pile of bells groaned.

A massive Bordon perched precariously on top of the stack shifted.

Gerard tried to kick away, but he was tethered.

His pressure gauge hose had snagged on the clapper of a smaller bell as he was thrown.

He was trapped.

The silt out was total now.

He couldn’t see his hand in front of his face.

He was blind, pinned against a wall of unstable bronze at 100 ft with explosives detonating above.

Panic clawed at his throat.

He hyperventilated, his breath coming in short, jagged gasps.

This was how divers died.

Panic, over breathing, carbon dioxide buildup.

Stop, he told himself.

Stop.

Breathe.

He closed his eyes.

Seeing nothing was better than seeing the swirling chaos.

He focused on the tactile.

He felt the hose.

It was wedged, tight.

If he pulled too hard, he would blow the hose and lose all his air.

He reached for his knife.

It was a heavy titanium cutter.

He felt for the snag.

He couldn’t cut the hose.

He had to cut the iron loop of the clapper mechanism or chip the rust away.

Impossible.

He had to take the rig off.

It was a maneuver he had practiced in pools, but never in the freezing dark with a current trying to kill him.

He unclipped his waist strap.

He undid the chest buckle.

He slipped his left arm out of the harness, then his rod, keeping the regulator in his mouth.

He was now free of the heavy tanks, holding them in front of him like a shield.

He manipulated the tank block, twisting it, working the hose free from the bronze snare.

Clang.

The hose popped free.

The tanks banged against the bell.

A mournful deep note that vibrated through his chest.

He slipped his arms back into the harness, buckled the waist strap, and checked his gauge.

700 PSI.

He was low, critical.

He needed to leave now.

He found his safety reel line, his thread of Ariadne leading out of the maze.

He began to kick hard.

He followed the chain back up the cliff face, his lungs burning.

As he reached the 60-foot shelf, the explosion stopped.

Maybe Klouse had realized he was too close, or maybe the storm had chased him off.

Gerrard didn’t stop to decompress properly.

He would have to ride the edge of the bends.

He ascended to 20 ft and held there, watching his computer count down the mandatory safety stop minutes.

They were the longest minutes of his life.

He hung in the gray water, shivering uncontrollably, listening to the silence return.

When he broke the surface, the snow was a white curtain.

“The nautilus was rocking violently.

Elena was at the gunnel, her face pale with terror.

They threw charges,” she screamed, grabbing his tank manifold to haul him in.

“I tried to ram them, but they were too fast.

” Gerard flopped onto the deck, too exhausted to stand.

He ripped his mask off, gasping the freezing air.

“Did you find it?” Elena asked, dropping to her knees beside him.

“Was it all for nothing?” Gerard reached into his dry suit pocket and pulled out the camera.

He managed a weak, shivering smile.

“We are not silent,” he whispered.

“That’s what they wrote.

3 months later, the media circus had been intense.

The Lake Finster horde was on the front page of every paper from Vienna to London.

Klaus Gruber was currently entangled in a dozen lawsuits in a criminal investigation for the illegal use of explosives in a protected waterway.

But today, the cameras were distant, kept back by a police cordon.

Gerard stood on the deck of a massive salvage barge.

He was wearing a suit which felt tight and unnatural compared to his dry suit.

Elena stood beside him, clutching a folder of archived documents.

The crane winch winded, a high-pitched sound that cut through the crisp spring air.

A thick steel cable descended into the water down to the coordinates Gerard had defended with his life.

“Ready?” the salvage master asked.

Gerard nodded.

“Bring her up.

” The cable went taut.

The barge dipped slightly under the weight.

Slowly, agonizingly, the water began to churn.

First came the bubbles.

Then the dark shape rising from the green deep.

The water broke with a cascade of foam.

The bell breached the surface.

It was the bronze sentinel, the first one Gerard had found.

It streamed water, the algae and muscles clinging to it like a shroud.

But as the sunlight hit it for the first time in 80 years, the bronze flared with a dull gold fire.

The crane swung it onto the deck.

It settled on heavy timber blocks with a heavy thud that shook the deck plates.

Silence fell over the crowd on the shore and the crew on the barge.

Gerrard walked forward.

He had a specialized hammer in his hand.

The restoration team had given him the honor.

He looked at the inscription on the side of the bell, now visible in the daylight.

solely deo Gloria, glory to God alone, and beneath it the crude welding marks of the chain that had tethered it to the earth.

He looked at Elena.

She was crying openly and without shame.

Gerard swung the hammer.

Dong.

The sound was colossal.

It wasn’t just a noise.

It was a physical force.

a deep resonant baritone that rolled out over the water, bouncing off the cliff faces, echoing up toward the snowcapped peaks.

It was a sound of morning, heavy with the memory of the war.

But as the echo faded, turning into a high, shimmering hum in the air, it changed.

It became a sound of return.

The bell was ringing.

The silence of the cemetery was broken.

Gerrard rested his hand on the cold metal, feeling the vibration dying away under his palm.

He looked out at the lake.

The water was calm today, blue and inviting.

The dark eye was open.

He took a deep breath of the mountain air.

It didn’t taste like debts or fear anymore.

It tasted like history.

“Welcome home,” he whispered.

News

Ilhan Omar ‘PLANS TO FLEE’…. as FBI Questions $30 MILLION NET WORTH

So, while Bavino is cracking down in Minnesota, House Republicans turning the heat up on Ilhan Omar. They want to…

FBI & ICE Raid Walz & Mayor’s Properties In Minnesota LINKED To Somali Fentanyl Network

IC and the FBI move on Minnesota, touching the offices of Governor Tim Walls and the state’s biggest mayors as…

FBI RAIDS Massive LA Taxi Empire – You Won’t Believe What They Found Inside!

On a Tuesday morning, the dispatch radios in hundreds of Los Angeles taxi cabs suddenly stopped playing route assignments. Instead,…

Brandon Frugal Finally Revealed What Forced Production to Halt in Season 7 of Skinwalker Ranch….

The Secret of Skinwalker Ranch became History Channel’s biggest hit. Six successful seasons documenting the unknown with real science and…

1 MINUTE AGO: What FBI Found In Hulk Hogan’s Mansion Will Leave You Shocked….

The FBI didn’t plan to walk into a media firestorm, but the moment agents stepped into Hulk Hogan’s Clearwater mansion,…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage… It started like any other evening…

End of content

No more pages to load