A city crew lifted a sunken housebo from the canal after 90 years, expecting a routine cleanup.

But when they cut through the vessel’s strange armored hull, the secret stacked inside made them freeze and call 911 immediately.

The water of the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal was not so much a liquid as it was a living, breathing archive of the city’s industrial sins.

A thick, opaque soup that smelled of diesel, decaying oak, and the sulfurous memory of a century’s worth of runoff.

For Jason Breeden, a 45-year-old salvage foreman who had spent half his life pulling forgotten things out of Midwestern waterways, the canal was a workspace that demanded respect, patience, and a strong stomach.

But today, the canal was demanding something else entirely.

Speed.

We are two weeks behind, Breeden.

Two weeks.

The voice belonged to Marcus Sterling, the city’s liaison for the waterway clearing project.

He stood on the metal grading of the support pontoon, his pristine high visibility vest clashing with the grime streaked reality of the dredging operation.

The Army Corps of Engineers wants this sector cleared before the freeze.

If you can’t verify that the channels clear by Friday, we pull the contract.

Simple as that.

Jason rubbed the bridge of his nose, smearing a streak of grease across his forehead.

He looked out at the gray churn and water where his dive team was currently prepping.

The company, Breed and Marine Salvage, was hanging by a thread.

They needed the completion bonus from this job to overhaul the engines on their main tug.

If Sterland pulled the contract, the company would likely go under, dragging Jason’s livelihood and the pensions of his six crew members down with it.

The sonar picked up a hard anomaly in sector 4.

Marcus, Jason said, his voice grally from shouting over generator engines.

It’s big, geometric.

We can’t just dredge over it.

If it’s a fuel tank or a submerged vehicle, the clamshell bucket will rip it open and you’ll have an EPA nightmare that makes a twoe delay look like a vacation.

Sterling checked his watch.

A nervous tick that ground on Jason’s nerves.

You have 4 hours to identify it and rig it for removal.

If it’s just a rock, I’m docking your pay for the wasted time.

Jason didn’t answer.

He turned his back on the bureaucrat and walked to the edge of the dive platform where Ben, his lead diver and second in command, was checking the seal on his dry suit.

Ben was 20 years Jason’s junior, built like a linebacker, but possessing the delicate touch required for underwater work where visibility was measured in inches.

You hear that? Jason asked, checking the airlines connected to Ben’s Kirby Morgan dive helmet.

Loud and clear, boss, Ben said, his voice muffled until he clicked his comm’s unit.

4 hours to move a mountain.

Standard Tuesday.

Sonar says it’s flat topped about 40 ft long.

Jason briefed him, pointing to the grainy black and white printout taped to the console.

sits deep in the silt.

Be careful of rebar or snag hazards.

This section of the canal was a dumping ground for the old steel mills.

Ben nodded, secured his helmet, and gave the thumbs up.

With a splash that barely registered over the drone of the diesel pumps, he disappeared into the murky darkness.

Jason moved to the comm station, putting on the headset.

He watched the bubbles rise, counting the seconds.

The canal was deep here, a dredged trench meant to keep Chicago’s waste flowing away from Lake Michigan.

Down there, it was a world of total sensory deprivation.

Bottom.

Ben’s voice crackled in Jason’s ear.

Visibility is zero.

I’m in the soup.

Switching to tactile.

This was the reality of inland salvage.

There were no bright coral reefs or shafts of sunlight.

There was only black water and the feeling of your gloved hands moving through silt that felt like wet velvet.

Jason watched the depth gauge 30 ft down.

I’ve got a contact, Ben said, his breathing rhythmic and calm.

It’s weird, Jace.

Weird how is it a container? No, it’s a hull.

I’m feeling a gunnel.

It’s a boat.

There was a pause filled only by the hiss of the regulator, but the texture is wrong.

It’s not wood.

It’s not steel.

Jason leaned into the microphone.

Fiberglass? No, way too cold and too rough.

It feels like stone.

Smooth stone.

Concrete? Jason asked, confused.

Yeah, that’s it.

It feels like a sidewalk, but shaped like a hull.

I’m walking the length of it.

It’s massive, Jason.

Flat bottom, boxy superructure.

It’s practically buried in the mud.

If this is a boat, it’s built like a bunker.

Pharaoh cement.

Jason’s mine raced through naval history.

During steel shortages in the World Wars, people sometimes built boats out of reinforced concrete.

But they were rare, usually clumsy things.

Why would one be scuttled here in the middle of a shipping lane? Can we lift it? Jason asked.

It’s intact, Ben reported.

I’m not feeling any major breaches in the hall.

But Jace, if this is concrete and it’s full of mud, it’s going to be heavy.

Heavier than the crane barge is rated for if we don’t rig it perfect.

Rig it, Jason ordered, making a decision that would change the trajectory of their lives.

I’m calling in the Goliath.

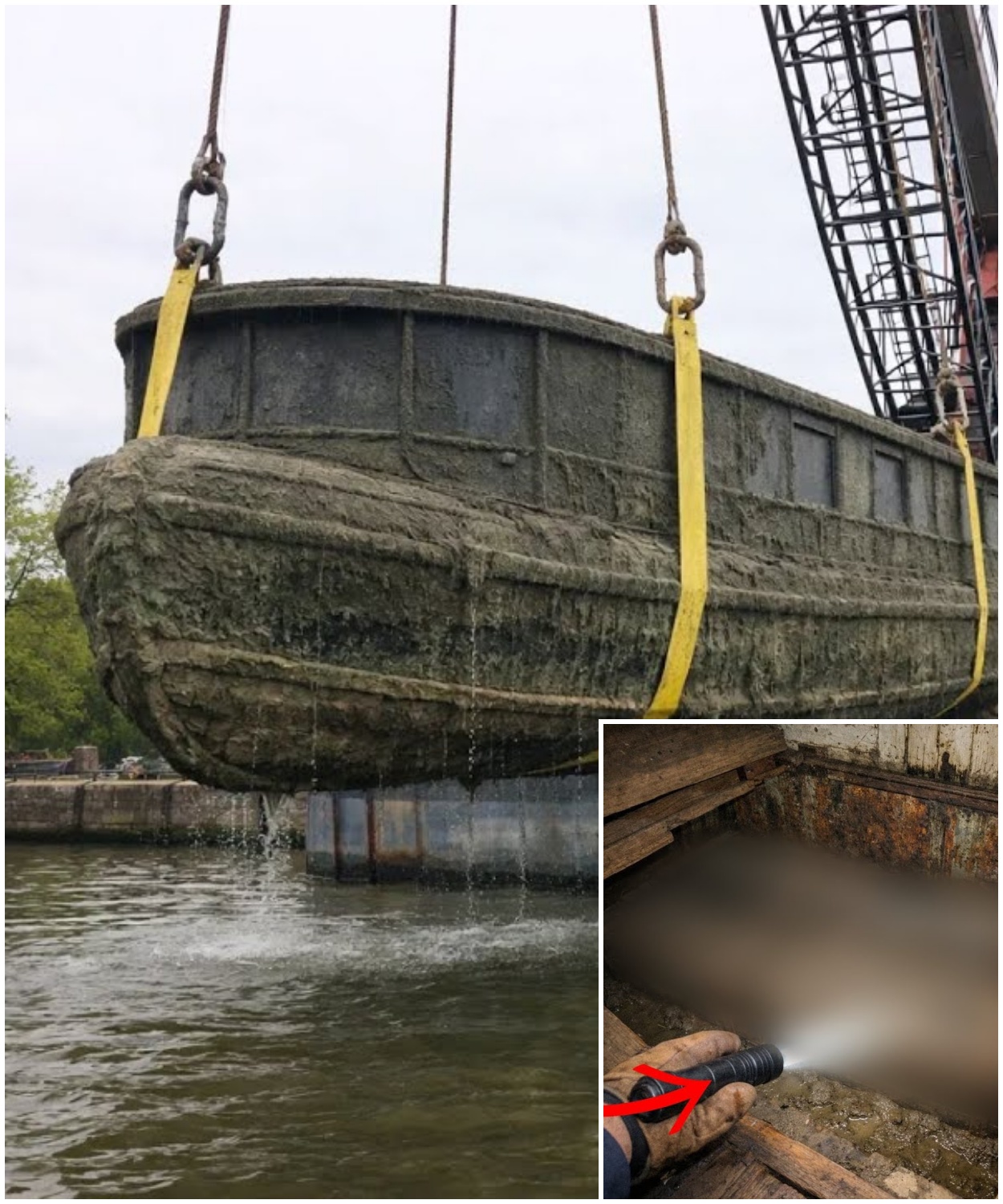

The arrival of the Goliath shifted the atmosphere of the work site from a routine maintenance job to a major engineering event.

The Goliath was a heavy lift crane barge, a floating platform capable of hoisting 200 tons.

It was overkill for a recreational boat, but Jason’s gut told him that whatever was sleeping in the mud below was no leisure craft.

It took 3 hours to tunnel the lifting straps under the hull using high pressure water jets.

The sun had vanished behind a wall of gray clouds, turning the canal into a dark ribbon of slate.

Sterling paced the deck, making frantic phone calls, but Jason ignored him.

He was focused on the load cells, the digital gauges that would tell him how much tension was on the cables.

“Straps are set,” Ben said, shivering slightly as he stood on the deck, having surfaced, and stripped off his gear.

“She’s cradled tight.

” “All right,” Jason signaled the crane operator.

Take up the slack.

Slow.

Dead slow.

The massive diesel engines of the crane roared to life, spewing black smoke into the overcast sky.

The thick steel cables groaned, shedding water as they tightened.

The barge dipped slightly in the water, compensating for the load.

10 tons.

Jason read off the gauge.

20 30.

The water around the lifting site began to churn.

Bubbles of trapped gas from the riverbed erupted on the surface, releasing a stench of rotten eggs and old decay.

50 tons, Jason said, his brow furrowing.

This doesn’t make sense.

A 40ft housebo, even a concrete one, shouldn’t weigh this much unless it’s filled with lead.

Maybe it’s full of silt, Ben suggested, watching the tension in the cables.

The windows are intact, Jason muttered.

If it’s sealed, there shouldn’t be that much mud inside.

70 tons.

Enter in the red zone.

The crane operator called out over the radio, “Boss, do we push it?” Jason looked at the water.

The object was fighting them.

It wanted to stay buried.

He thought of the contract.

the bankruptcy.

The crew, push it, bring her up.

The engine screamed.

The cables vibrated with a terrifying hum, a frequency that could be felt in the teeth.

Then, with a sucking sound that resembled a giant intake of breath, the surface of the canal broke.

A collective silence fell over the crew.

Rising from the depths was a monstrosity.

It was a housebo, yes, but it looked more like a floating mausoleum.

The hull was gray, streaked with 90 years of black algae and river slime.

It was boxy, utilitarian, and utterly devoid of the grace usually associated with boats.

As it hovered over the water, water cascading from its flat bottom, the sheer mass of it cast a shadow over the work deck.

Set it down,” Jason barked.

“Get it on the deck before a cable snaps.

” The crane operator lowered the vessel onto the reinforced steel deck of the Goliath.

The barge groaned under the weight, settling deep into the water.

As the cables went slack, Jason and Ben approached the vessel, scrapers and flashlights in hand.

Up close, the concrete hull was a marvel of engineering.

It was pharaoh cement, steel mesh plastered over with high-grade cement, smoothed to a finish that had withtood nearly a century of immersion.

But it was the windows that caught Jason’s attention.

He climbed the ladder to the main deck, his boots slipping on the slime.

He approached what should have been the salon window.

He raised his scraper and cleared away a thick mat of zebra muscles.

Ben, Jason called out, his voice low.

Look at this.

Ben climbed up beside him.

Beneath the algae wasn’t glass.

It was steel.

A solid plate of half-in steel had been welded over the window frame, completely sealing the interior.

“Who armors a housebo?” Ben asked, tapping the metal.

It rang with a dull, heavy thud.

Someone who didn’t want anyone getting in, Jason said.

He moved to the main cabin door.

It was heavy oak reinforced with iron straps that had rusted to a deep orange but held firm.

There was no handle, only a complex wheellike locking mechanism that looked more like a bank vault than a nautical hatch.

It’s sealed tight, Jason said.

And look at the draft marks on the hull.

Even sitting on our deck, she looks heavy.

This thing is dense.

How do we get in? Ben asked.

Jason looked at the lock.

It was fused by rust and time.

We don’t pick it.

We cut it.

Get the angle grinder.

The sound of the grinder biting into the iron hinges was a shriek that echoed off the canyon walls of the canal.

Sparks cascaded like fireworks, illuminating the darkening afternoon.

It took Ben 20 minutes of sweating.

Kursen worked to slice through the three heavy throw bolts that secured the door.

When the last bolt gave way with a metallic ping, the door didn’t swing open.

It popped.

A hiss of air escaped the seal.

Pressure equalizing after nine decades.

The smell that hit them wasn’t the rot of the river.

It was a stale, dry scent.

It smelled of cedar, old paper, and something sharp and metallic like gun oil.

“It’s dry inside,” Jason realized, holstering his flashlight.

The seal held.

“We’re walking into a time capsule.

” “After you, boss,” Ben said, stepping back.

“Jason pushed the heavy door open.

It groaned on its remaining hinges, revealing a black void.

He clicked his flashlight on and stepped across the threshold.

The beam cut through the stagnant air, revealing a scene that defied logic.

They were standing in a salon, but not one meant for a vacation.

The furniture was rotted.

The velvet upholstery turned to dust that danced in the light, but the structures remained.

A heavy poker table sat in the center of the room.

A calendar on the wall, curled and yellowed, displayed the date.

October 1929.

1929, Ben whispered.

Stock market crash.

Jason moved deeper into the room.

The floorboards creaked under his boots.

The air felt heavy, oppressive.

There was a sense of unfinished business here.

A glass sitting on the poker table had tipped over, but it hadn’t broken.

An ashtray was filled with the remnants of cigars that had turned to ash long ago.

But it was the architecture that bothered Jason.

The room felt small, too small.

Based on the exterior dimensions of the boat, the cabin should have been wider and taller.

The walls, Jason said, shining his light on the paneling.

They’re built out maybe 2 feet on each side.

Insulation, Ben suggested.

Or armor, Jason corrected.

Sand filled walls.

Poor man’s bulletproofing.

This wasn’t a houseboat, Ben.

It was a floating fortress.

He walked to the center of the room, his eyes scanning the floor.

The Persian rug, now a moldy rag, was slightly a skew.

Jason kicked it aside.

Beneath it, the oak floorboards were beautiful, even in their decay.

But there was a seam, a straight line cut across the grain of the wood, running the length of the room.

“It’s a hatch,” Jason said.

“A cargo hatch disguised as a floor.

” “But houseboats don’t have cargo holds,” Ben argued.

“They have bes.

” “This one does.

” Jason knelt.

He found a flush- mounted ring pull recessed into the wood.

He tugged it.

It didn’t budge.

Give me the crowbar.

Ben handed him the steel bar.

Jason jammed the wedge into the seam.

He leaned his weight into it.

The wood groaned, protesting the intrusion with a loud crack.

The false floorboard lifted.

Jason shined his light into the opening.

It wasn’t a BGE filled with oily water.

It was a dry steel-lined compartment stretching the length of the vessel, and it was full.

Stacked floor to ceiling were wooden crates, dozens of them.

They were stamped with faded black ink.

Jason squinted to read the text on the nearest one.

Midwest Agricultural Supply.

Tractor parts fragile.

Tractor parts? Ben asked.

peering over Jason’s shoulder.

That explains a weight.

Cast iron engine blocks.

Maybe, Jason said.

But his gut was twisting.

The crate wasn’t nailed shut.

It was clamped.

He reached down, the drop only about 3 ft, and used the crowbar to pop the latches on the top crate.

The lid came off easily.

Jason expected to see rusty gears or pistons.

Instead, he saw straw packing.

He brushed the straw side.

Beneath it was oil cloth wrapped tightly around something heavy.

Jason pulled the oil cloth back.

The flashlight beam glinted off blue steel.

It wasn’t a tractor part.

It was a barrel with cooling fins, a vertical foregrip, a receiver that was unmistakably iconic.

Holy.

Ben breathed.

It was a Thompson submachine gun, an M1928, the Chicago typewriter.

It was in mint condition, preserved in the airtight hold in the heavy coating of Cosmoline grease.

Beside it lay the signature drum magazine.

Jason didn’t touch it.

He grabbed the lid of the crate and checked the manifest tacked to the inside.

Cutie, 10 units, destination, Cicero.

He looked at the rest of the hold.

There were at least 50 crates.

“There are hundreds of them,” Jason whispered, the realization chilling him more than the river water.

“Ben, this isn’t salvage.

This is an armory.

We’re rich,” Ben stammered, his eyes wide.

“Jace, collectors would pay.

” “Stop!” Jason snapped.

“We aren’t rich.

We’re in trouble.

This is illegal ordinance.

unregistered machine guns.

If we try to sell these, we go to federal prison for the rest of our lives.

This is a crime scene.

He stood up, his heart hammering against his ribs.

Get out now.

We’re calling 911.

The arrival of the Chicago Police Department turned the salvage barge into a circus.

Within an hour, three patrol boats were circling the Goliath, and a SWAT team had set up a perimeter on the shore.

Sterlin, the city rep, was apoplelectic, screaming about his timeline, but he was silenced when the bomb squad arrived.

Detective Miller, a wearyl looking man with a salt and pepper mustache, stood with Jason on the deck of the barge.

You’re telling me you found a gangster’s stash? See for yourself, Jason said, pointing to the open hatch.

The bomb squad, clad in heavy protective suits, was carefully moving crates.

They had confirmed the count.

400 Thompson submachine guns, 50,000 rounds of 45 ACP ammunition, and of what appeared to be sawed off shotguns.

It was enough firepower to equip a small army.

“This is incredible,” Miller said, shaking his head.

“This must have been Oansions or maybe the Jennas stockpiling for a war that never kicked off.

” “That’s great for the history books,” Jason said.

“But when can you get it off my barge? I have a contract to finish.

” “Hold on,” a voice called out from the hold.

It was the lead bomb technician, a woman named Vance.

Her voice was tight, edged with panic.

Clear the deck, I repeat.

Clear the deck immediately.

What is it? Miller barked into his radio.

More guns.

No, Vance replied, stepping up the ladder with slow, deliberate movements.

She was holding a small wooden box far smaller than the gun crates.

We found these in the back, stamped mining supplies.

She set the box down gently on the steel deck and backed away.

I carefully pried one open, Vance said, removing her helmet, her face pale.

It’s dynamite, 1920s vintage, high-grade gelatin dynamite.

So, it’s old, Sterling shouted from the safety of the support boat.

It’s probably a dud.

Vance turned on him, her eyes blazing.

That’s not how dynamite works, you idiot.

Over time, the nitroglycerin separates from the stabilizer.

It sweats.

It forms crystals on the outside of the sticks and pools at the bottom of the box.

She pointed a trembling finger at the innocent looking box.

That pool of liquid is pure, unstable nitroglycerin.

It’s more sensitive than a snowflake.

A vibration, a drop in temperature, a sharp noise, anything could set it off.

Jason looked at the box, then at the massive concrete boat beneath his feet.

How much is down there? We counted 10 cases, Vance said.

If one goes, they all go.

And with the confinement of that concrete hull, it won’t just be an explosion.

It will be a shaped charge.

It’ll cut this barge in half, destroy the canal walls, and likely shatter windows for 3 miles.

The silence that followed was absolute.

The birds seemed to stop singing.

The hum of the city faded.

“We need to tow it out to the lake,” Sterling suggested, his voice trembling.

No!” Vance shouted.

“You can’t move it.

The vibration of the tug engines alone could detonate it.

It sits right here until we neutralize it.

” But Jason looked at the sky.

The gray clouds had turned a bruised purple.

The wind was picking up, whipping the white caps on the canal.

There’s a storm front coming in.

It’s supposed to hit in an hour.

Gusts up to 50 m an hour.

If this barge starts rocking in the wind, Ben said, realizing the horror of the geometry, and those crates slide.

Boom, Vance finished.

While the bomb squad frantically radioed for a chemical neutralization team.

A police launch brought another visitor to the barge.

He didn’t look like a cop.

He wore a tweed jacket and carried a leather satchel.

Dr.

Aerys Thorne.

Detective Miller introduced him.

Historian from the museum.

We needed to know what we were dealing with.

Thorne looked at the houseboat with a mixture of awe and terror.

The Iron Maiden, he whispered.

I thought it was a myth.

It’s a bomb.

Jason corrected him.

A floating bomb.

Thorne ignored him, touching the concrete hull.

It belonged to the North Side gang.

After the St.

Valentine’s Day Massacre in 29, the survivors were paranoid.

They feared Capone was coming for them next, they built a mobile fortress, a place to sleep where bullets couldn’t reach them.

Stocked with enough weapons to retake the city.

“Why did they sink it?” Jason asked.

The police raids of Leighton 29, Thorne explained, pulling a photocopy of an old newspaper from his bag.

The feds were closing in.

The captain of the vessel, a man named Shotgun Smitty, knew that if they were caught with this arsenal, they’d face the electric chair, so he pulled the sea He scuttled the boat in a deep dredge hole, planning to come back for it when the heat died down.

He never came back, Ben said.

No.

Smitty was found dead in a ditch two weeks later.

The secret of the Iron Maiden died with him.

Until today.

The wind gusted, slamming a wave against the side of the Goliath.

The barge lurched.

The metal deck groaned.

Vance.

The bomb tech grabbed the railing.

We’re out of time.

The storm is here.

We can’t wait for the chemical team.

If this barge rocks too hard, that nitro will detonate.

“What do we do?” Miller asked.

“I have to go down there,” Vance said, her face setting into a mask of grim determination.

“I have to stabilize the crates with foam and then chemically neutralize the liquid nitro by hand, but I can’t do it if the boat is moving.

” She looked at Jason.

your crane.

Can you stabilize the barge? Jason looked up at the boom of the crane.

The spuds anchors are down, but in this mud they’ll drag if the wind hits 50 knots.

The only way to hold her steady is to use the crane to apply tension.

Pin the housebo against the deck of the barge so it doesn’t shift.

You have to stay in the cab, Vance told him.

Everyone else evacuates.

If it blows.

I know, Jason said.

I’m dead.

So are you.

Jason looked at Ben.

Get on the police boat.

Go.

Jace, go.

Jason barked.

I need the weight off the deck anyway.

As the crew scrambled onto the police launches and sped away to a safe distance, Jason climbed the ladder to the crane operator’s cab.

He sat in the seat, the leather cold against his back.

He fired up the diesel engine.

The vibration made him wse, thinking of the sweating death in the hold just 50 ft away.

Through the rain sllicked glass, he saw Vance give him a thumbs up.

She disappeared into the dark mouth of the houseboat.

The wind hit.

The Goliath shuddered.

A gust hammered the side of the crane, screaming through the lattis boom.

Jason gripped the control levers.

He had to play the wind.

If he pulled too hard, he might crush the concrete boat.

If he pulled too little, the barge would rock.

He watched the bubble level on his dashboard.

He had to keep it perfectly centered.

For 45 minutes, Jason Breeden fought the storm, his hands cramped around the controls.

Every time the wind howled, he countered it with the throttle and the winch, a dance of tons of steel against the fury of nature.

He was sweating, his shirt clinging to his back despite the chill in the cab.

He imagined Vance down there in the dark with a syringe of neutralizer hovering over a pool of liquid explosive, feeling the boat shift every time Jason corrected the list.

The radio crackled.

One crate done,” Vance’s voice whispered.

“Move into the second.

” Jason didn’t reply.

He couldn’t break his concentration.

A massive gust, a micro burst slammed into the barge.

The bubble level surged to the left.

“Easy,” Vance yelled over the radio.

Jason slammed the throttle forward, swinging the boom to counter the wait.

The cables screamed in protest.

The barge groaned, listed, and then miraculously leveled out.

“Held!” Jason grunted, his teeth clenched so hard his jaw achd.

“Just one more minute,” Vance said.

The minutes stretched like hours.

The rain turned to hail, drumming against the roof of the cab.

Jason’s eyes burned.

He thought of the calendar in the boat.

October 1929, the end of an era, the beginning of the depression, and now January 2026, the end of his company, or the beginning of something else.

Clear.

Vance’s voice broke the trance.

All nitroglycerin neutralized.

Packs are stable.

You can relax the tension, Jason.

Jason slumped back in the seat, letting out a breath he felt he’d been holding for 90 years.

He throttled down the engine.

The silence that filled the cab was the sweetest sound he had ever heard.

Two months later, the Chicago History Museum held its gala for the opening of the Underworld River exhibit.

Jason stood in the back wearing a suit that felt tight in the shoulders.

Beside him, Ben was grinning, holding a glass of champagne.

In the center of the hall, behind high security glass, was one of the Thompson submachine guns.

It had been cleaned, the cosmoline removed, and the blue steel shown under the museum lights.

It was beautiful and terrifying.

Next to it sat the agricultural supply crate and a photograph of the iron maiden being lifted from the water, a gray ghost rising from the dead.

You know, Sterling said, appearing beside Jason, he was smiling, taking credit, as he had for the news cameras for weeks.

The city is very pleased with how you handled the anomaly.

The bridge contract is yours next year, Breeden.

No bid process.

Thanks, Marcus, Jason said, his voice flat.

He didn’t care about Sterling.

He looked at the plaque beneath the gun recovered by Breeden Marine Salvage.

The find had been valued at over $4 million in historical artifacts.

While the government seized the weapons, the salvage fee awarded to Jason’s company was substantial.

enough to fix the tugs, give the crew a massive bonus, and secure their future for a decade.

But that wasn’t what Jason was looking at.

He was looking at a smaller display case in the corner.

Inside was the calendar frozen on October 1929, and the poker hand that had been left on the table, a royal flush.

The captain had been holding a winning hand when the order came to sink the boat.

He had folded a winning hand to save his life and lost it anyway.

Jason turned to Ben.

“Ready to go?” “Parties just starting, boss.

” Ben said.

“I’ve got an early start,” Jason said.

“Rever doesn’t clear itself.

” He walked out of the museum into the cool Chicago night.

He drove his truck down to the canal service road.

He parked and walked to the edge of the water.

The canal was quiet.

The spot where the Iron Maiden had rested for 90 years was just dark water now, rippling in the moonlight.

The weight was gone.

The ghost was exercised.

Jason picked up a stone and tossed it into the black water.

It made a small splash, swallowed instantly by the depths.

The river kept its secrets, hiding the weight of the city’s past in its mud.

But every now and then, if you were patient and careful, and maybe a little lucky, it would let one go.

Jason Breeden zipped up his jacket against the wind, turned his back on the canal, and drove home.

News

Brandon Frugal Finally Revealed What Forced Production to Halt in Season 7 of Skinwalker Ranch….

The Secret of Skinwalker Ranch became History Channel’s biggest hit. Six successful seasons documenting the unknown with real science and…

1 MINUTE AGO: What FBI Found In Hulk Hogan’s Mansion Will Leave You Shocked….

The FBI didn’t plan to walk into a media firestorm, but the moment agents stepped into Hulk Hogan’s Clearwater mansion,…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage… It started like any other evening…

Ant Anstead’s Final Days on Wheeler Dealers Were DARKER Than You Think

In early 2017, the automotive TV world was rocked by news that Ed China, the meticulous, soft-spoken mechanic who had…

What They Found in Paul Walker’s Garage After His Death SHOCKED Everyone…

What They Found in Paul Walker’s Garage After His Death SHOCKED Everyone… He was the face of speed on the…

What Salvage Divers Found Inside Sunken Nazi Germany Submarine Will Leave You Speechless

In 1991, a group of civilian divers stumbled upon something that didn’t make sense. A submarine resting where no submarine…

End of content

No more pages to load