In March of 2017, 37-year-old experienced climber Derek Pullman set out alone to conquer the frozen north face of Mount Silverton in the Colorado Rockies.

He told his girlfriend he would be back in 4 days.

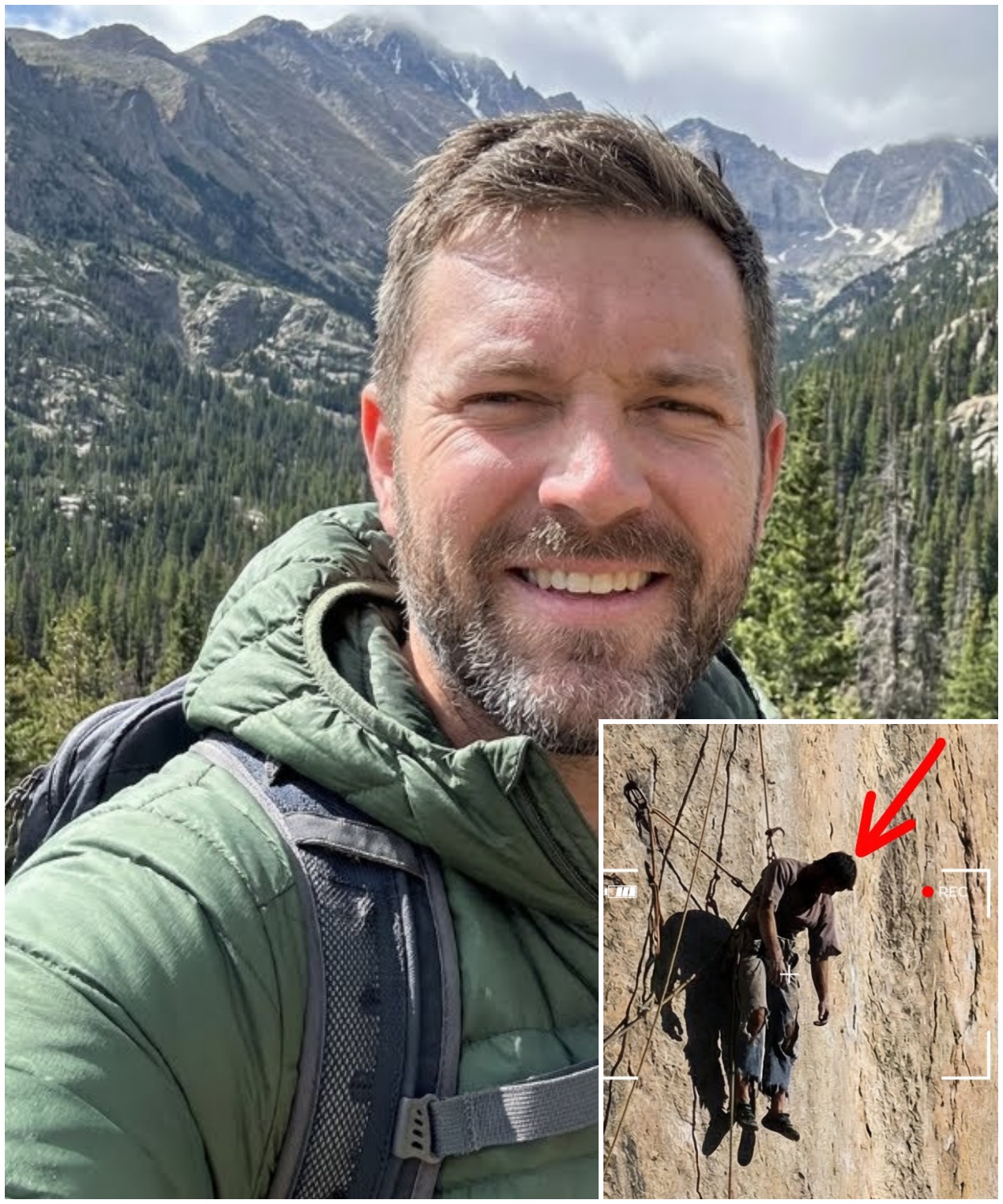

3 months later, a search drone captured an image that would haunt everyone who saw it.

A figure in torn, faded clothing, still clinging to a narrow ledge 800 ft above the valley floor, suspended between earth and sky as if frozen in his final moment of hope.

The mountains had kept him all that time, visible yet unreachable, a silent witness to the thin line between ambition and tragedy.

On March 11th, 2017, Derek Pullman arrived in the small mountain town of Granite Falls, Colorado, a place known to serious climbers as the gateway to some of the most challenging ascents in the southern Rockies.

He was a man who lived for vertical spaces, someone who found clarity in the risk that made others turn away.

At 37, he had logged over a decade of climbs across three continents, from the granite walls of Yoseite to the icecoated peaks of Patagonia.

But Mount Silverton held a special place in his mind.

He had tried its north face twice before, and both times the weather had forced him back.

This time he told friends he was going to finish what he started.

The forecast showed a narrow window of stable weather, cold but clear, and Dererick believed that was all he needed.

He checked into the Alpine Rest Lodge just afternoon.

A small familyrun place at the edge of town where climbers often stayed before heading into the wilderness.

The owner, a woman named Patricia Langford, remembered him well.

She said he seemed focused, maybe even a little distant, like someone who had already left in his mind.

He carried two large duffel bags, one filled with climbing gear and the other with food, fuel, and emergency supplies.

He asked about road conditions to the trail head and whether the ranger station was open.

Patricia told him the roads were clear, but warned him that the temperatures up high were expected to drop below zero at night.

Derek nodded, her and said he had been in colder that evening.

He called his girlfriend, a woman named Jennifer Hail, who lived with him in Boulder.

According to phone records, the call lasted 11 minutes.

Jennifer later told investigators that Dererick sounded calm and confident.

He said he planned to start the climb early the next morning and expected to reach the summit by the third day.

He promised to check in via satellite messenger once he made it to the ridge.

She asked him to be careful and he laughed, saying he always was.

Those were the last words she heard from him.

The next morning, Dererick left the lodge before sunrise.

Patricia saw his truck pull out of the gravel lot just after 5.

The sky was still dark and frost covered the windshield.

He drove north on Highway 62 toward the access road that led to the base of Mount Silverton.

His vehicle, a white Ford Ranger with Boulder County plates, was later found parked at the trail head, locked and undisturbed.

Inside, investigators discovered a handwritten note on the dashboard with his planned route, estimated timeline, and Jennifer’s contact information.

It was the kind of precaution an experienced climber takes, a simple gesture that acknowledged the risks without dwelling on them.

Derek began his approach hike around 6:30 in the morning.

The trail to the base of the North Face was steep and rocky, winding through dense pine forest before opening onto a boulder field that stretched toward the mountains lower cliffs.

According to his itinerary, he planned to reach the base campsite by early afternoon, rest, and begin the technical climbing the following day.

The weather that morning was exactly as predicted, cold, clear with light winds.

For the first day, everything seemed to be going according to plan, but after that silence.

Derek did not send a message on the 12th, nor on the 13th.

By the evening of March 14th, Jennifer began to worry.

She tried calling his cell phone, but there was no signal in the mountains.

She checked the satellite messenger account they shared, but there were no new updates.

On the morning of the 15th, she contacted the Granite Falls Sheriff’s Department and filed a missing person report.

The deputy who took her call, a man named Leonard Cross, noted that Dererick was an experienced climber with proper equipment and that it was not uncommon for people to lose communication in the back country.

Still, he agreed to send a ranger to check the trail head.

By noon, the ranger confirmed that Dererick’s truck was still there, untouched, and that no one had seen him return.

Sheriff Raymond Baxter, a veteran of the department with over 25 years of service, decided to launch a preliminary search.

He knew the north face of Silverton well.

It was a place where even strong climbers could get into trouble.

The rock was unstable in places and the cold could turn deadly fast.

On March 16th, a small team of volunteers and county search and rescue personnel hiked to the base camp area.

They found evidence that someone had been there recently, a flattened section of snow where a tent might have been pitched, a few cramping marks on the ice near the approach gully, and a single empty fuel canister half buried in the snow.

The canister was the same brand Dererick had purchased in town.

It was enough to confirm he had made it that far.

But beyond that point, the trail went cold.

The north face itself was a sheer wall of granite and ice over 1,200 ft tall, split by a series of cracks, ledges, and chimneys that required advanced technical skills to navigate.

The team surveyed the lower sections with binoculars, but saw no signs of movement, no bright colors, no gear.

The rock was dark and shadowed, and the snow blended into the gray stone.

If Dererick was up there, he was invisible from the ground.

Over the next week, the search intensified.

More volunteers arrived, including members of the Rocky Mountain Rescue Group, a nonprofit organization that specialized in high altitude recovery.

They brought ropes, harnesses, helmets, and radios.

Some of them knew Derek personally.

They had climbed with him, shared blays, trusted him with their lives.

Now they were searching for his.

The team split into groups.

One group worked the lower cliffs, checking al coes and checking behind boulders.

Another group attempted to climb partway up the face to get a better vantage point.

The weather, which had been stable, began to shift.

Clouds moved in from the west, bringing wind and scattered snow.

Visibility dropped.

The temperature fell to 15° below zero at night.

On March 22nd, after nearly a week of searching, the operation was suspended due to dangerous conditions.

Sheriff Baxter held a brief press conference in the Granite Falls Community Center.

He stood in front of a large map of the mountain, his face lined with exhaustion.

He said that while the search was being paused, it was not over.

He said they would resume as soon as the weather allowed.

He also said that Derek Pullman was an experienced climber who knew the risks and that everyone involved was doing everything they could.

Jennifer sat in the back of the room, her hands folded in her lap, staring at the map as if she could will it to reveal where he was.

April came and with it a false spring.

The snow in the valleys began to melt, but the high peaks remained locked in winter.

The search teams returned twice more, once in midappril and again at the end of the month.

Each time they found nothing new.

No clothing, no abandoned gear, no tracks.

It was as if Dererick had simply vanished into the stone.

Theories began to circulate.

Some believed he had fallen and that his body was buried under snow or hidden in a creasse.

Others thought he might have made it to the summit and descended a different route, getting lost or injured on the way down.

A few even speculated that he had chosen to disappear, though those who knew him dismissed that idea immediately.

Dererick was not running from anything.

He was moving towards something.

A goal, a feeling, a moment of perfect focus that only the mountains could provide.

As the weeks passed, the story began to fade from the local news.

Other incidents took its place.

The volunteers returned to their lives.

The ranger station filed its reports and moved on, but Jennifer did not move on.

She stayed in Granite Falls, renting a small room above a hardware store on Main Street.

She printed flyers with Dererick’s photo and posted them at gas stations, trail heads, and grocery stores.

She walked the trails herself, even though she was not a climber, scanning the cliffs with a pair of binoculars she bought at a thrift shop.

People in town began to recognize her, the woman in the gray jacket, who never stopped looking up.

In late May, a hiker reported seeing what he thought was a flash of color on the north face somewhere near the upper third of the wall.

The sheriff sent a team to investigate, but the color turned out to be a piece of old rope left by a previous climbing party years earlier.

It was weathered and frayed, and it had nothing to do with Derek.

Still, Jennifer took it as a sign that he was up there, that something of him remained.

By June, the official search was quietly closed.

The case remained open, but no active efforts were being made.

The file was placed in a cabinet at the sheriff’s office next to others like it, people who had gone into the wilderness and never come back.

Sheriff Baxter told Jennifer privately that he believed Dererick had died on the mountain, probably from a fall or exposure, and that his body might never be recovered.

He said it with sympathy, but also with the firmness of someone who had seen it before.

Jennifer listened, nodded, and then asked if she could borrow the department’s high-powered spotting scope.

Baxter hesitated, then agreed.

She set it up on a ridge overlooking the north face and spent hours each day scanning the rock section by section, ledge by ledge.

She kept a notebook with sketches of the wall, marking areas she had already checked.

She did this for weeks alone in silence while the summer sun turned the snow to water and the water ran down the mountain in thin silver threads.

It was during one of these long solitary sessions that she first thought about using a drone.

She had read about search teams using them in other states, small aircraft equipped with cameras that could reach places humans could not.

She mentioned it to Sheriff Baxter, who said the department did not have the budget for that kind of technology.

But he did not say no.

He said if she could find someone with a drone and the skill to fly it in the mountains, he would support it.

Jennifer began asking around.

She posted messages on climbing forums, sent emails to tech companies, and reached out to hobbyist drone pilots in the area.

Most ignored her.

A few responded with sympathy, but no solution.

Then in early June, she received a message from a man named Aaron Vest, a freelance videographer based in Denver who had done aerial filming for outdoor brands and documentary crews.

He had a high-end drone capable of flying in wind and cold.

And he said he was willing to help.

He did not ask for money.

He only asked for the coordinates.

On June 18th, 2017, 3 months after Derek Pullman disappeared, Aaron Vest drove to Granite Falls with his equipment.

Jennifer met him at the trail head just after dawn.

The air was cool and still, and the mountain was wrapped in a thin layer of mist.

Aaron was in his early 30s, quiet and methodical.

He asked Jennifer to describe the route Derrick had planned, and she showed him the map, pointing to the line that traced up the north face.

Aaron studied it, then looked up at the wall.

He said he would start low and work his way up, grid by grid, recording everything.

Derek was there at the drone would find him.

They began just after 7 in the morning.

Aaron assembled the drone on a flat rock near the base of the approach trail, his hands moving with practiced efficiency.

The device was larger than Jennifer had expected with four rotors and a gimbal mounted camera that could rotate in nearly any direction.

He explained that the battery would give him about 25 minutes of flight time in these conditions, maybe less if the wind picked up.

He planned to make several flights, each one covering a different section of the face, and then review the footage carefully on his laptop.

Jennifer stood a few feet away, her arms crossed against the cold, watching as he powered up the controls.

The drone lifted off with a high-pitched were rising vertically until it cleared the tops of the nearest pines.

Aaron guided it forward toward the wall, his eyes fixed on the small screen in his hands.

The camera feed showed the rock in sharp detail, every crack and shadow visible even from a distance.

He began at the lowest accessible point, just above the snow line, and moved the drone slowly from left to right, scanning the face in horizontal strips.

The first flight revealed nothing, just stone, ice, and the occasional stunted tree clinging to a crack.

Aaron landed the drone, swapped the battery, and launched again.

This time, he went higher, focusing on a section of the wall where a prominent ledge system cut diagonally across the rock.

The ledge was wide enough in places for a person to stand, and it matched a feature on Derek’s planned route.

The drone hovered close to the stone, the camera zooming in on the surface.

Jennifer watched the screen over Aaron’s shoulder, her breath shallow.

She saw nothing but rock.

Aaron moved the drone further up past the ledge into a zone where the wall became steeper and the ice thicker.

The light was starting to shift as the sun rose higher, casting long shadows across the face.

He flew three more times that morning, each flight pushing further up the mountain.

By noon, they had covered roughly half of the north face.

Aaron reviewed the footage on his laptop, scrubbing through the video frame by frame, looking for anything that stood out.

Jennifer sat beside him on a boulder, her hands wrapped around a thermos of coffee that had long gone cold.

She did not speak.

She just waited.

Aaron paused the video and zoomed in on a section near the upper third of the wall.

There was a shadow darker than the others, tucked into a corner where two rock features met.

He replayed the footage, adjusted the contrast, and leaned closer.

It could be a recess in the stone, or it could be something else.

He marked the time stamp and said he would get a better angle on the next flight.

After a short break, Aaron sent the drone up again, this time heading directly for the area he had flagged.

The wind had picked up slightly, and the drone wavered as it climbed, but Aaron kept it steady.

He maneuvered it closer to the shadowed area, tilting the camera downward.

The image on the screen was grainy at first, backlit by the sun, but as the drone adjusted its position, the shadows resolved into shapes.

Jennifer saw it before Aaron said anything.

A ledge narrow and uneven, jutting out from the wall about 800 ft above the base.

And on that ledge, a figure.

It was small on the screen but unmistakable.

A person sitting upright with their back against the rock, legs bent, one arm resting across their lap.

The clothing was torn and discolored, faded by months of sun and wind.

The fabric that had once been bright red or orange now looked rust brown, almost the same color as the stone.

The figure was not moving.

Aaron brought the drone closer, as close as he dared without risking a collision.

The camera focused, and the details became clearer.

The person’s face was turned slightly downward, shadowed by the angle of the light.

Their hair was matted and dark.

One leg was extended awkwardly as if it had been injured.

The other was bent at the knee.

The clothing hung loosely on the frame, and there were tears in the fabric along the shoulder and chest.

Around the figure’s waist was a climbing harness, still clipped to a sling that was anchored to a bolt in the rock.

The rope connected to the harness trailed off the ledge and disappeared below, severed or frayed partway down.

Jennifer made a sound, something between a gasp and a sob.

She put her hand over her mouth and turned away from the screen.

Aaron kept the drone steady, recording everything.

He did not say anything.

He did not need to.

They both knew.

He flew the drone in a slow circle around the ledge, capturing the scene from multiple angles.

The footage showed that the ledge was approximately 4 ft wide and 6 ft long.

A thin shelf of rock in the middle of an otherwise featureless wall.

There was no way up from there without technical gear and no way down without the same.

The figure was alone, facing out toward the valley as if watching the world below.

After several minutes, Aaron brought the drone back and landed it gently on the rock.

He turned off the controller and set it down.

Jennifer was sitting on the ground now, her knees pulled up to her chest, staring at nothing.

Aaron walked over to her and crouched down.

He said quietly that he was sorry.

She nodded but did not look at him.

He said he would call the sheriff.

Sheriff Baxter arrived within the hour, accompanied by two deputies and a member of the search and rescue team, a climber named Troy Whitman who had been part of the original search efforts.

Aaron showed them the footage on his laptop, playing it slowly so they could see every detail.

Baxter watched in silence, his jaw tight.

When the video ended, he asked Aaron if he was certain about the location.

Aaron pulled up a GPS overlay and showed him the exact coordinates.

The ledge was located on the northeast section of the face, roughly 2/3 of the way up in an area that had been partially obscured by an overhang during the ground searches.

It was a place that could only be seen from the air or from another point high on the wall.

Baxter turned to Troy and asked if it was possible to reach the ledge.

Troy studied the footage, zooming in on the rock features surrounding it.

He said it was possible, but it would not be easy.

The approach would require a technical climb from below or a rapel from above.

Either way, it would take a team of experienced climbers, and the conditions would need to be right.

Baxter asked how long it would take to organize.

Troy said he could have a team ready in 2 days.

Baxter nodded and told him to make it happen.

He then looked at Jennifer, who was still sitting on the ground, her face pale and stre with tears.

He asked her if she was okay.

She shook her head.

He asked if there was someone he could call.

She said no.

He told her that they would bring Derek down that it might take time, but they would do it.

She thanked him in a voice so quiet it was almost lost in the wind.

The recovery operation began on June 21st, 2017.

A team of six climbers, all volunteers from the Rocky Mountain Rescue Group, assembled at the base of Mount Silverton just after sunrise.

They carried ropes, anchors, pulleys, a rescue litter, and enough gear to set up a complex rigging system on the wall.

The plan was to climb to a point above the ledge, establish a secure anchor, and lower one or two climbers down to the site.

From there, they would assess the condition of the body and determine the safest way to bring it down.

The lead climber was a man named Vincent Taber, a 42-year-old with over 20 years of mountain rescue experience.

He had worked recoveries in worse conditions, but he knew this one would be difficult.

The ledge was exposed.

The rock was loose in places.

And the emotional weight of the operation was heavy.

Everyone on the team had hoped they would find Derek alive.

Now they were bringing him home in the only way they could.

The climb took most of the morning.

The team moved carefully, placing protection as they went, communicating through helmet radios.

The rock was cold and damp, and the air smelled like iron and dust.

By midday, Vincent and another climber, a woman named Rachel Cove, had reached a position about 50 ft above the ledge.

They set up a multi-point anchor using bolts and cams, tested it thoroughly, and then prepared the ropes.

Rachel would be the one to descend.

She was smaller, lighter, and had more experience with technical body recoveries.

Vincent would manage the ropes from above, while the rest of the team waited below, ready to assist once the body was lowered.

Rachel clipped into the rapel line, checked her harness and helmet, and gave Vincent a thumbs up.

She leaned back over the edge, and began to descend, her boots scraping against the stone.

The descent was slow and controlled.

As she neared the ledge, she could see the figure more clearly.

It was a man sitting upright, his back against the wall, his head tilted slightly to one side.

His eyes were closed, and his skin was darkened by the sun and wind.

His clothing was in tatters.

The jacket shredded along one arm, the pants torn at the knees.

The climbing harness was still buckled around his waist, and the rope that had once connected him to his anchor was severed cleanly about 10 ft below the ledge, the end frayed and discolored.

Rachel touched down on the ledge and steadied herself.

She clipped into the anchor that Dererick had set months earlier, testing it to make sure it was still solid.

Held, she knelt beside the body and placed a gloved hand on his shoulder.

She spoke into her radio confirming that she had reached the site and that the individual was deceased.

She said there were no signs of recent trauma, no blood, no obvious injuries.

It appeared that he had died from exposure or exhaustion, possibly both.

She noted that his position suggested he had been conscious when he stopped, that he had chosen to sit to rest, and that at some point he simply had not gotten up again.

Rachel began the process of preparing the body for transport.

She worked carefully, treating Derek with the same respect she would want for herself.

She unfassened his harness from the old anchor and secured him to the rescue litter, a lightweight stretcher designed for vertical evacuation.

She wrapped him in a thermal blanket, not for warmth, but for dignity.

As she worked, she noticed small details.

His hands were scraped and calloused.

The fingers curled slightly as if he had been holding on to something.

His boots were still laced, though one sole had separated partially from the leather.

There was a small camera clipped to his chest harness.

The lens cracked, but the body intact.

Rachel carefully removed it and placed it in a pouch on her harness.

She knew it might contain images, moments from his final days that could help piece together what had happened.

When the body was secured, Rachel radioed Vincent and told him she was ready.

The team above began the slow process of hauling the litter up the wall.

The operation took over 3 hours.

The litter had to be maneuvered around overhangs, across rough sections of rock, and through narrow gaps where the wall closed in.

Rachel climbed alongside it, guiding it with a tag line, making sure it did not snag or swing.

The other team members below watched through binoculars, their faces grim.

Jennifer was not there.

Sheriff Baxter had suggested she stay in town, and for once, she had agreed.

She said she did not need to see him like that.

She only needed to know he was coming home.

By late afternoon, the litter reached the top of the technical section.

The team lowered it carefully down the lower slopes, passing it from one person to the next until it finally reached the base.

They set it down gently on a flat area near the approach trail.

Vincent knelt beside it and unclipped his harness.

He was exhausted, his face stre with dirt and sweat.

He looked at the others and nodded.

They had done what they came to do.

Sheriff Baxter met the team at the trail head.

A medical examiner from the county was already waiting with a transport vehicle.

The body was transferred from the litter to a black bag, zipped closed, and loaded into the back.

Baxter shook hands with each member of the recovery team, thanking them quietly.

Vincent told him it was the least they could do.

He said Derek was one of their own and that no one should be left on the mountain.

Baxter asked about the camera.

Rachel handed it over and Baxter placed it carefully in an evidence bag.

He said he would have it examined and that if there was anything on it, Jennifer would be the first to know.

The drive back to Granite Falls was quiet.

The sun was setting behind the peaks, casting long shadows across the valley.

In town, word had already spread.

People stood outside the hardware store, the coffee shop, the lodge, watching as the vehicle passed.

Some bowed their heads, others just stood in silence.

Jennifer was waiting at the sheriff’s office.

When Baxter arrived, he led her into a small private room and closed the door.

He told her that Dererick had been found on a ledge high on the north face, that he appeared to have died from exposure, and that there were no signs he had suffered.

He said the recovery had been successful and that Derek was being taken to the medical examiner’s office in the county seat.

Jennifer asked if she could see him.

Baxter said she could, but not yet.

He said the examiner would need time to complete the necessary work and that it might be better to wait.

She nodded, her eyes red but dry.

She had no more tears left.

Baxter handed her a plastic bag containing Dererick’s personal effects.

A few small items recovered from the ledge.

Inside was a carabiner, a small notebook with water damaged pages, and the camera.

Jennifer held the camera in her hands, turning it over slowly.

She asked if there was anything on it.

Baxter said he did not know yet, but that he would find out.

She thanked him and left the office, walking slowly down Main Street as the street lights began to flicker on.

She returned to her rented room, sat on the edge of the bed, and stared at the camera for a long time.

Whatever it held, she was not sure she was ready to see it, but she knew eventually she would have to look.

The medical examiner’s office was located in a low brick building on the outskirts of Ridgeway, the county seat, about 40 mi south of Granite Falls.

Dr.

Howard Pine, a forensic pathologist with nearly 30 years of experience, had seen many cases involving deaths in the wilderness, but each one carried its own gravity.

On the morning of June 22nd, he began his examination of Derek Pullman’s remains.

The body had been transported in a refrigerated vehicle overnight and was now laid out on a stainless steel table under bright overhead lights.

Dr.

Pine worked methodically documenting everything.

The clothing was photographed and then carefully removed.

Each piece placed in a separate labeled bag.

The red jacket, once a vibrant signal color meant to stand out against stone and snow, was faded to a dull rust tone, its fabric stiff with dried sweat and dirt.

The sleeves were shredded in places, likely from abrasion against the rock.

The pants were similarly damaged with holes at the knees and along the thighs.

The climbing harness still buckled around the waist, showed signs of prolonged wear, but remained structurally intact.

Dr.

Pine noted that the harness had been properly fitted, and that the buckles had not failed.

The rope attached to it had been severed cleanly, suggesting a sudden break under tension rather than gradual wear.

Beneath the clothing, the body showed signs consistent with prolonged exposure to the elements.

The skin was darkened and leathery in places, particularly on the face and hands, a condition known as mummification that occurs in cold, dry environments.

There were no signs of major trauma, no broken bones, no deep lacerations.

The hands were araided with scars on the palms and fingers that indicated recent friction, likely from handling ropes and rock.

The legs showed signs of muscle atrophy, suggesting that Dererick had been immobilized or minimally active for an extended period before death.

Dr.

Pine measured the body’s core temperature, though after 3 months it provided little useful information.

He took samples of tissue, hair, and nails for toxicology and further analysis.

He examined the eyes, which were sunken and clouded, and the mouth, which was slightly open.

There were no signs of bleeding or injury to the head.

The teeth were intact.

The overall impression was of a man who had died slowly, not violently.

His body shutting down from cold, dehydration, and exhaustion.

In his preliminary report, Dr.

Pine concluded that the cause of death was hypothermia compounded by dehydration and possibly acute mountain sickness.

He estimated that Dererick had survived on the ledge for at least several days, possibly longer, before succumbing.

The position of the body, seated upright with the back against the wall, suggested that Dererick had been conscious and aware during his final hours.

He had not collapsed or fallen.

He had sat down, perhaps to rest, perhaps knowing that he would not get up again.

The report noted that there were no signs of foul play, no evidence of another person’s involvement.

This was a case of a climber who had become stranded, unable to continue or retreat, and who had waited on that ledge until his body gave out.

Sheriff Baxter received a copy of the report later that afternoon.

He read it twice, then placed it in the case file.

He had seen enough of these over the years to know that the mountains did not need malice to kill.

They only needed time and cold.

But the question that remained was how Dererick had ended up on that ledge in the first place and why he had not been able to get down.

The camera recovered from the scene offered a possible answer.

Baxter sent it to a digital forensic specialist in Denver, a man named Ian Merik, who worked with law enforcement on evidence recovery from damaged electronics.

Ian had extracted data from phones pulled from rivers, hard drives burned in fires, and memory cards crushed under debris.

A cracked climbing camera was well within his capabilities.

It took him 2 days to access the files.

The camera’s internal memory was partially corrupted, but enough data remained to reconstruct a sequence of images and short video clips.

Ian transferred the recovered files to a secure drive and sent them back to Baxter with a note explaining that some files were incomplete and that timestamps might be inaccurate due to damage.

Baxter reviewed the files alone in his office, the door closed, the blinds drawn.

What he saw was a visual record of Derek Pullman’s final climb, a journey that had begun with confidence and ended in isolation.

The first images were taken at the base of the mountain.

Wide shots of the north face against a clear blue sky.

The rock looked immense and forbidding, a vertical landscape of cracks and ledges that seemed to stretch endlessly upward.

In one photo, Derek’s shadow was visible on the snow, a long dark shape cast by the early morning sun.

The next series of images showed the beginning of the climb.

Derek had set the camera to take time shots every few minutes, a common practice among solo climbers who wanted to document their progress.

The images showed his hands gripping holds, his boots wedged into cracks, his face partially visible beneath a helmet and sunglasses.

He looked focused, his expression calm.

The rock around him was steep but featured with plenty of holes and natural protection points.

As the sequence continued, the images showed Derek moving higher.

The perspective shifted, the ground below falling away, the trees shrinking to dark green patches.

He reached the first major ledge system and paused there, setting up an anchor and taking a longer break.

One photo showed his gloved hand holding an energy bar, the rapper half open.

Another showed the view to the west, a sweeping panorama of ridges and valleys bathed in golden light.

He was making good progress.

The timestamps indicated he was ahead of schedule.

Then the sequence jumped forward.

The next images were taken higher on the face in a section where the rock became steeper and the ice more prevalent.

The light had changed, the sun lower in the sky, shadows creeping across the wall.

Dererick’s movements appeared more cautious.

In one video clip, he was heard breathing heavily, his voice muttering something about the rock being looser than expected.

The camera shook as he placed a piece of gear, testing it with a hard pull before committing his weight.

He continued upward, but the intervals between images grew longer, suggesting he was moving more slowly.

Then came the image that changed everything.

It was a still frame taken from a slightly downward angle, showing Derrick’s feet on a narrow ledge, his body pressed against the wall.

The rope trailed down from his harness, disappearing out of frame.

In the background, partially visible, was a section of rock that appeared fractured, a thin crack running diagonally across the surface.

The timestamp read March 13th, late afternoon.

The next video clip provided context.

The camera was attached to Derrick’s chest harness, pointing outward.

His breathing was audible, quick, and shallow.

He was speaking, his voice tight with stress.

Okay.

Okay.

The anchor pulled.

The whole thing just came out.

I’m on the ledge now.

I’m safe for the moment, but the rope is cut.

I can see it down there just hanging.

Must have caught an edge when the anchor failed.

There was a pause, the sound of wind buffeting the microphone.

I’ve got maybe 60 ft of rope left on this end.

Not enough to repel.

Not enough to reach the next anchor point below.

I’m going to have to think about this.

The clip ended.

The following images showed Dererick’s attempts to assess his situation.

He photographed the ledge he was standing on, a narrow platform of rock about 4 ft wide with a vertical wall behind and a sheer drop in front.

He photographed the severed rope, the frayed end fluttering in the wind.

He photographed the rock above, searching for a route that might allow him to continue upward without the full protection of his rope system.

But the wall above was blank, a smooth expanse of granite with few holes and no obvious cracks.

In another video clip, Dererick’s voice was calmer, more measured.

It’s getting dark.

I’m going to wait here tonight.

See if I can figure something out in the morning.

I got my bivvie sack some food, water.

I can make it through the night.

The weather’s holding.

I just need to stay calm and think this through.

He sounded like a man trying to convince himself.

The next series of images were taken the following morning, March 14th.

The light was pale and cold, the sky overcast.

Derek had set up a small bivwack on the ledge, his sleeping bag draped over his legs, his back against the wall.

He photographed his hands, which were red and swollen, the fingers stiff from the cold.

He photographed his water bottle, now half empty.

He photographed the drop below, a dizzying expanse of air and stone.

In a video clip from that morning, his voice had changed.

The confidence was gone, replaced by a quiet, almost resigned tone.

I tried climbing up, but it’s no good.

The rocks too hard without more gear.

I tried going down, but I can’t reach the next anchor with what I have left.

I’m stuck here.

I sent a distress signal on the messenger, but I don’t know if it went through.

The battery’s low.

I’m going to conserve it.

Try again later.

He paused, the wind howling in the background.

If anyone finds this, tell Jennifer I’m sorry.

I thought I could handle this.

I really did.

The images from the following days were sporadic.

Derek seemed to be rationing the camera’s battery, taking fewer photos, shorter videos.

On March 15th, he recorded a message in which he described his attempts to signal for help.

He had used a small mirror to reflect sunlight toward the valley, hoping someone might see it.

He had shouted until his voice gave out, though he knew the chances of anyone hearing him were slim.

He had tried to rig a makeshift anchor using the remaining rope and a few pieces of gear, but without enough length, it was useless.

By March 16th, the tone of his recordings had shifted again.

He was no longer talking about escape.

He was talking about endurance.

It’s cold, really cold at night.

I’m trying to stay warm, but it’s hard.

I’ve got maybe two days of food left, maybe three if I stretch it.

Water’s the bigger problem.

I’ve been melting snow, but there’s not much up here, and it takes forever.

I’m trying to stay hydrated, but I can feel myself getting weaker.

He coughed.

A harsh rattling sound.

I keep thinking someone’s going to come.

I keep looking down at the base, expecting to see people, but there’s nothing.

Just trees and rocks.

Maybe they’re searching somewhere else.

Maybe they think I made it to the top and went down the other side.

I don’t know.

The video ended abruptly, the screen going black.

The next image was dated March 18th.

It showed Dererick’s face gaunt and sunburned, his eyes hollow.

He was not looking at the camera.

He was looking out at the valley at the world beyond the ledge.

There was no video accompanying this image, just the silent, frozen moment.

The final video clip was dated March 20th.

Derek’s voice was barely a whisper, horse, and weak.

I don’t think I’m getting out of this.

I don’t think anyone’s coming.

I tried.

I really tried, but I’m so tired.

It’s hard to think, hard to move.

I just want to sleep.

There was a long silence, just the sound of the wind and his shallow breathing.

Jennifer, if you see this, I love you.

I’m sorry I didn’t come home.

I’m sorry.

The screen went black.

There were no more files.

Sheriff Baxter sat in the dark office for a long time after the last video ended.

He replayed some of the clips, listening to Dererick’s voice change from confident to concerned to desperate to resigned.

It was a chronicle of a man’s slow realization that he was not going to survive, that the mountain had him and was not going to let go.

Baxter had seen death in many forms, but there was something uniquely cruel about this.

Dererick had not died quickly.

He had died alone, fully aware, waiting for a rescue that never came.

The sheriff made copies of the files and placed the originals in the evidence locker.

He wrote a detailed report summarizing the contents and his interpretation of events.

Derek Pullman had been climbing solo on the north face of Mount Silverton when a critical anchor failed, severing his rope and stranding him on a narrow ledge approximately 800 ft above the base.

He had survived on the ledge for at least 8 days, possibly longer, before succumbing to hypothermia and dehydration.

He had attempted to signal for help and had recorded messages documenting his situation.

There was no evidence of errors in judgment or reckless behavior.

It was in the truest sense an accident, a confluence of bad luck, equipment failure, and the unforgiving nature of the environment.

Baxter knew he would have to show the videos to Jennifer, but he wanted to prepare her first.

He called her that evening and asked if she could come to the office the next day.

She agreed without asking why.

When she arrived the following morning, Baxter led her into the same private room where they had spoken before.

He explained that the camera had been recovered and that it contained images and videos from Dererick’s final days.

He said the content was difficult, that it showed Dererick in distress, and that she did not have to watch it if she did not want to.

Jennifer looked at him for a long moment, then said she needed to see it.

She needed to know what happened.

Baxter set up the laptop and played the files in chronological order.

Jennifer watched in silence, her hands folded in her lap, her face expressionless.

When Dererick’s voice came through the speakers, her breath caught, but she did not look away.

She watched every clip, every image, until the screen went black for the final time.

When it was over, she sat very still.

Baxter asked if she was all right.

She nodded slowly.

She said she was glad Dererick had not been alone in his final moments, that he had been able to speak, to say what he needed to say.

She said it gave her something.

Not closure exactly, but understanding.

She thanked Baxter and left the office, carrying the weight of what she had seen.

Outside, the sun was shining, and the streets of Granite Falls were busy with the ordinary rhythms of a summer day.

But for Jennifer, the world had shifted.

She had heard her partner’s last words, seen his last moments of clarity, and now she had to find a way to carry that forward.

The funeral was held on a warm afternoon in early July in a small chapel on the outskirts of Boulder where Dererick had lived for most of his adult life.

The building was made of pale wood and glass with large windows that looked out onto the foothills of the Rockies.

It was the kind of place Derrick would have appreciated, simple and open with the mountains visible in the distance.

More than a hundred people attended.

Friends from the climbing community, co-workers from the outdoor gear company where he had worked part-time, former college classmates, and family members who had traveled from across the country.

Jennifer sat in the front row, flanked by Derek’s parents, Gordon and Diane Pullman, both in their late 60s, their faces drawn with grief.

Gordon was a retired engineer, a quiet man who had never understood his son’s need to climb, but had never stood in his way.

Diane had always worried, had always asked Dererick to be careful, and now her worst fears had been realized.

She held a folded handkerchief in her lap, her hands trembling slightly.

The service was led by a friend of Derek’s, a climber named Lucas Grant, who had known him for over a decade.

Lucas spoke about Dererick’s passion for the mountains, his meticulous preparation, his respect for the risks he took.

He described Dererick as someone who did not climb to conquer or to prove anything but to find a kind of peace that existed nowhere else.

He said that Dererick had died doing what he loved.

And while that phrase often felt like a hollow comfort, in this case it was true.

Dererick had chosen his path and he had walked it fully even to the end.

Several others spoke as well.

A woman named Brin who had climbed with Derek in the Tetons recalled his patience and humor, the way he could lighten the mood even in stressful situations.

A man named Jerome who had worked with Derek talked about his dedication to craftsmanship, the care he took in repairing climbing gear for others, often without charging them.

Each memory painted a picture of a man who was thoughtful, generous, and deeply committed to the things he valued.

Jennifer did not speak.

She had been asked if she wanted to say something, but she had declined.

She felt that anything she said would fail to capture what Dererick had meant to her and she did not trust herself to hold together in front of so many people.

Instead, she had prepared a slideshow of photographs, images of Derek in the mountains on rock faces at campsites laughing with friends staring out at sunrises.

The photos played on a screen at the front of the chapel accompanied by quiet instrumental music.

There were no images from the camera recovered on the ledge.

Those belonged to Jennifer alone.

After the service, people gathered outside in the shade of cottonwood trees.

There was food, coffee, and the low murmur of conversation.

Jennifer stood apart from the crowd near the edge of the property where the grass gave way to scrub and stone.

She watched the mountains in the distance, the same peaks Derrick had looked at every day, the same horizons he had chased.

Sheriff Baxter had made the drive from Granite Falls to attend the funeral.

He approached Jennifer quietly, offering his condolences again.

She thanked him and asked if there had been any further findings from the investigation.

Baxter said that the case was officially closed, that the medical examiner’s report and the camera footage had provided a complete account of what had happened.

There would be no further inquiries.

Jennifer nodded.

She asked if the camera files could be returned to her, and Baxter said they already had been copied onto a secure drive that was waiting for her at the sheriff’s office.

She said she would pick it up when she was ready.

Before he left, Baxter told her something he had been thinking about since watching the videos.

He said that Dererick had done everything right, that the anchor failure was not something he could have predicted or prevented, and that even the most experienced climbers could find themselves in situations beyond their control.

He said it was important for her to know that Dererick had not made a fatal mistake.

He had simply been unlucky.

Jennifer listened, her eyes on the distant ridge line.

She said she understood, but that understanding did not make it easier.

Baxter nodded and walked back to his car, leaving her alone with her thoughts.

In the weeks that followed, Jennifer tried to return to a normal life.

She went back to her job as a graphic designer, working from the small apartment she had shared with Derek.

But the space felt different now, emptier, filled with reminders of a future that would not happen.

His climbing gear still hung in the closet.

His books were stacked on the shelves.

His coffee mugs sat unwashed in the sink, exactly where he had left it the morning he drove to Granite Falls.

She could not bring herself to move any of it.

She spent her evenings going through the files from the camera, watching the videos again and again, studying Derrick’s face, listening to his voice.

She was searching for something, though she was not sure what.

Maybe a sign that he had known how much she loved him.

Maybe a sense of peace in his final words.

Maybe just a way to keep him present, to delay the moment when he would become only a memory.

One night in late July, she came across a video she had not noticed before.

A short clip buried in the recovered files.

timestamped March 19th.

It was only 15 seconds long, and the image was shaky, as if Dererick had been holding the camera in his hand rather than mounting it on his chest harness.

The frame showed the sky, pale and stre with clouds, and then tilted down to show the ledge, the rock, and Dererick’s leg stretched out in front of him.

His voice came through faint and rough.

I saw a bird today, an eagle, I think.

It flew right past me, close enough that I could hear its wings.

It didn’t even look at me.

Just kept going like I wasn’t here.

Made me think that maybe this is what it’s like to disappear.

You’re still there, but the world just moves around you like you’re already gone.

The video ended.

Jennifer played it again, then a third time.

She realized that Dererick had been thinking about his own erasure, about the idea that he might vanish from the world without a trace.

And in a way, he nearly had.

If not for the drone, if not for Aaron’s willingness to help, Dererick might still be on that ledge, unseen and unreovered, slowly becoming part of the mountain.

The thought made her feel cold, even in the summer heat.

She closed the laptop and sat in the dark, listening to the sounds of the city outside her window.

She thought about the last time she had seen Derek standing in the doorway with his duffel bags, smiling as he said goodbye.

She had kissed him and told him to be safe, and he had promised he would.

It was a promise he had meant to keep.

But the mountains did not care about promises.

In August, Jennifer made a decision.

She could not stay in Boulder, surrounded by Dererick’s things, walking past the climbing gym where they had met, seeing the trails they had hiked together.

She needed distance, a place where she could begin to build a life that was hers alone.

She gave notice at her job, packed what she could fit into her car, and donated most of Derek’s belongings to a nonprofit that provided gear to young climbers who could not afford it.

She kept a few things, his favorite jacket, a journal he had written in during a trip to Peru, and the camera.

Everything else she let go.

Before she left, she drove back to Granite Falls one last time.

She wanted to see the mountain again, to stand at the base of the North Face and look up at the place where Dererick had spent his final days.

She arrived on a clear morning in late August, the air cool and crisp, the aspens just beginning to turn gold.

She parked at the trail head and hiked to the spot where Aaron had launched the drone.

The view was the same, the massive wall of stone rising into the sky, indifferent and eternal.

She stood there for a long time, shielding her eyes against the sun, searching for the ledge.

She could not see it from the ground.

It was too high, too obscured by the angles of the rock, but she knew it was there.

a narrow shelf of stone where Dererick had waited, where he had spoken his last words, where he had watched the world go on without him.

She thought about the eagle he had seen, the way it had flown past without acknowledging him.

She wondered if that was what Dererick had wanted in the end, not to be saved, but simply to be seen, to be known, to have his presence registered by something other than the stone and sky.

She whispered his name into the wind, a small sound against the vastness of the mountain.

Then she turned and walked back down the trail.

If you’ve been with us this far, please take a moment to like this video and subscribe to the channel.

Your support helps us bring these stories to light and ensures that the voices of those we’ve lost are not forgotten.

By the time Jennifer reached her car, the sun was high and the parking lot was filling with other hikers.

People beginning their own journeys into the wilderness.

She watched them for a moment, young and laughing, oblivious to the risks, trusting in their strength and their luck.

She did not resent them.

She only hoped they would be more fortunate than Dererick had been.

She drove south away from the mountains toward a new city and a new life.

She did not know what that life would look like, but she knew it would be different.

She would carry Derek with her, not as a weight, but as a part of her story, a chapter that had ended, but would never be erased.

In the months that followed, the story of Derek Pullman’s death spread quietly through the climbing community.

It was shared on forums, discussed in gear shops, mentioned in safety briefings.

The footage from his camera was never made public out of respect for his family, but the details of what had happened were known.

Climbers talked about anchor failure, about the importance of redundancy, about the fine line between confidence and overreach.

Some saw Dererick’s death as a cautionary tale.

Others saw it as a reminder of the inherent unpredictability of the mountains, the way even the most prepared and skilled could find themselves at the mercy of forces beyond their control.

The north face of Mount Silverton remained a draw for experienced climbers, but those who attempted it now did so with Derek’s story in mind.

A small memorial plaque was placed at the trail head by members of the Rocky Mountain Rescue Group.

A simple bronze plate mounted on a stone Kairen.

It bore Derek’s name, the dates of his birth and death, and a single line.

He climbed with courage and respect.

People passing by often stopped to read it, some touching the metal with their fingertips, a silent acknowledgement of a life lived and lost in pursuit of something greater.

Sheriff Baxter retired in the spring of 2018 after more than two decades of service.

At his retirement party held in the community center in Granite Falls, several people mentioned the Pullman case.

They said it had been one of the most difficult recoveries in the county’s history.

Not because of the technical challenges, though those were significant, but because of the emotional weight it carried.

Baxter thanked them, but said little else.

He had learned long ago that some cases stayed with you, not because of what you did, but because of what you could not do.

He had not been able to save Derek Pullman, but he had been able to bring him home.

And in the end, that had mattered.

Aaron Vest, the drone pilot who had found Dererick’s body, continued his work filming in the mountains.

He never spoke publicly about the Pullman case, but he thought about it often.

He had seen many things through the lens of his camera, wildlife, storms, the raw beauty of the high country, but the image of that figure on the ledge, still and alone, remained the most haunting.

It reminded him that technology could reveal what the eye could not see, but it could not change what had already happened.

It could only bear witness.

Vincent Taber and Rachel Cove, the climbers who had led the recovery effort, both continued their work with the Rocky Mountain Rescue Group.

They participated in dozens of operations in the years that followed, some successful, some not.

They rarely spoke about the Pullman recovery, but when they did, they emphasized the importance of preparation, communication, and the willingness to accept that sometimes, despite everyone’s best efforts, the outcome is already written.

The mountain, they said, does not negotiate.

Jennifer eventually settled in a small town in northern New Mexico, a place far from the peaks of Colorado, surrounded by desert and wide skies.

She found work as a freelance designer, took up pottery, and slowly built a community of friends who knew her story, but did not define her by it.

She did not climb again.

She had no desire to return to the vertical world that had taken Derek from her.

But she did hike long walks through the high desert where the land was open and the horizons were endless.

On those walks, she sometimes thought about the ledge, about the eight days Dererick had spent there, alone with his thoughts and his dwindling hope.

She wondered what he had thought about in those final hours, whether he had been afraid, whether he had found any peace.

She would never know for certain, but the videos had given her something close to an answer.

He had been scared, yes, but he had also been himself, cleareyed, and honest, facing the end with the same quiet determination he had brought to everything else in his life.

Years later, in the summer of 2021, Jennifer received an unexpected email.

It was from a young climber named Nathan, who said he had been researching the north face of Mount Silverton, and had come across the story of Derek Pullman.

He had read the memorial plaque, searched online for more information, and eventually found Jennifer’s name in an old news article.

He wrote to say that Dererick’s story had changed the way he approached climbing, that it had taught him to respect the mountains, not as obstacles to be conquered, but as environments that demanded humility and care.

He thanked her for sharing Dererick’s memory, even indirectly, and said that he hoped she had found peace.

Jennifer read the email several times.

She was surprised by how much it affected her.

She had not thought about Dererick’s story as something that could teach or inspire.

She had only thought of it as a loss, a private grief that she carried alone.

But Nathan’s words reminded her that Dererick’s life and his death had meaning beyond her own experience.

He had lived fully, loved deeply, and pursued something that mattered to him, even at great cost.

That was worth remembering.

She replied to Nathan, thanking him for reaching out.

She told him to climb safely, to trust his instincts, and to never take the mountains for granted.

She did not mention the videos or the camera.

Those remained hers, a final gift from Derek that she was not ready to share.

In the years since Dererick’s death, the technology that had found him continued to evolve.

Drones became more common in search and rescue operations.

Their cameras sharper, their range greater, their ability to navigate difficult terrain more refined.

They saved lives, located missing hikers, and provided critical information in conditions too dangerous for human searchers.

In a way, Derek’s case had been part of that evolution, a demonstration of what was possible when traditional methods fell short.

But technology, for all its power, could not erase the fundamental truth that the wilderness was vast, indifferent, and unforgiving.

People would continue to go into the mountains driven by curiosity, ambition, or the need to test themselves against something greater.

And some of them would not come back.

That was the bargain, unspoken, but understood that every climber made when they stepped onto the rock.

Derek Pullman had understood that bargain.

He had accepted the risks, prepared as best he could, and ventured into a place where the margin for error was razor thin.

He had been unlucky, but he had not been reckless.

He had been human, and in the end, that was enough.

The north face of Mount Silverton still stands, unchanged by the events of 2017.

The ledge where Dererick spent his final days is still there.

A narrow shelf of rock high on the wall, visible only from the air or from another climber’s vantage point far above or below.

The stone does not remember.

The wind does not carry his voice.

The mountain simply exists as it has for millennia, waiting for the next person to test themselves against its heights.

And somewhere in a small town in New Mexico, Jennifer continues her life, carrying Dererick’s memory like a smooth stone in her pocket.

something she can touch when she needs to.

Something that reminds her of who he was and what he meant.

She does not climb, but she still looks up at the mountains when she sees them, and she thinks of the man who loved them enough to give everything.

That is the story of Derek Pullman, a climber who vanished in the Colorado mountains and was found 3 months later, still hanging on a cliff edge.

His final moments preserved in digital fragments, his life reduced to coordinates and timestamps, and the quiet testimony of those who brought him home.

It is a story without villains, without mysteries, only the simple hard truth that sometimes the mountains win, and all we can do is remember those who tried.

The official investigation into Derek Pullman’s death concluded in September of 2017, but the questions it raised continued to resonate within the climbing community and among safety experts for years afterward.

The case became a subject of study, not because Dererick had done anything wrong, but because his experience illustrated how quickly a situation could deteriorate, even for someone with extensive training and proper equipment.

In October of 2017, the American Alpine Club published a detailed incident report in their annual publication, Accidents in North American Climbing.

The report was written by a committee of experienced mountaineers who had reviewed all available evidence, including the medical examiner’s findings, the camera footage, and interviews with those who had known Derek and his climbing history.

The report was thorough and respectful, focusing not on blame, but on lessons that could prevent future tragedies.

The committee noted several key factors that had contributed to Dererick’s predicament.

First was the anchor failure, a catastrophic event that could happen to anyone regardless of skill level.

The bolt that Derek had relied on had been placed years earlier by another climber.

And while it had appeared solid, internal corrosion and repeated freest cycles had weakened the metal to the point of failure.

The report emphasized that even gear that looks reliable can fail, and that climbers should always build redundant anchor systems whenever possible, especially when climbing alone.

Second was the decision to climb solo.

The report did not condemn solo climbing, which many experienced alenists practice, but it acknowledged the inherent risks.

Without a partner, Dererick had no one to assist him when the anchor failed, no one to help problem solve his predicament, and no immediate way to call for help once his satellite messenger battery died.

The report recommended that solo climbers carry backup communication devices, extra rope, and emergency bivvwac gear sufficient for an extended unplanned stay.

Third was the location of the lech.

Derek had ended up in a position where he could neither ascend nor descend safely with the gear he had remaining.

The report described this as a terrain trap, a situation where a climber becomes physically stuck due to the specific configuration of the rock.

The committee suggested that climbers study their routes carefully in advance, identifying potential problem areas and planning alternative escape routes in case of emergency.

The report concluded with a statement that Derek Pullman had been a skilled and conscientious climber whose death was the result of circumstances largely beyond his control.

It urged readers to honor his memory by learning from his experience and by approaching the mountains with both ambition and humility.

The publication was widely read and Dererick’s case was cited in climbing courses, safety seminars, and guide training programs.

His name became known not as a cautionary example of recklessness, but as a reminder that even the best could find themselves in impossible situations.

In the winter of 2017, a group of climbers who had known Derek organized a fundraiser in his memory.

The goal was to establish a grant program that would provide financial assistance to young climbers who wanted to pursue advanced training in mountain rescue and safety.

The fund was named the Derek Pullman Memorial Climbing Fund, and within 6 months, it had raised over $40,000 through donations from individuals, climbing gyms, and outdoor gear companies.

The first grants were awarded in the spring of 2018 to three recipients.

a college student studying wilderness medicine, a guide in training working towards certification in technical rescue, and a young woman who wanted to attend an avalanche safety course, but could not afford the tuition.

Each recipient was given a small card with Derek’s photo and a quote he had once written in a blog post about climbing.

The mountain doesn’t care who you are.

It only cares that you’re paying attention.

The fund continued to grow over the years, supporting dozens of climbers and contributing to a culture of safety and preparedness that Dererick himself had valued.

For those who had known him, it was a way to turn grief into something constructive to ensure that his death had meaning beyond the loss.

Among the recipients of the fund in 2019 was a young man named Colin Shaw, a 22-year-old from Vermont who had been climbing since his teens.

Colin had read about Derek’s case in the Alpine Club report and had been deeply affected by it.

He applied for the grant to attend a wilderness first responder course, writing in his application that he wanted to be prepared to help others in situations where seconds could make the difference between life and death.

He was awarded the grant and completed the course with high marks.

Two years later, Colin was climbing in the White Mountains of New Hampshire when he came across a hiker who had fallen and broken his leg on a remote trail.

Using the skills he had learned, Colin stabilized the injury, kept the hiker warm, and coordinated a rescue with local authorities.

The hiker survived and made a full recovery.

When Colin was later interviewed about the incident, he mentioned the grant that had made his training possible, and he spoke about Derek Pullman, a man he had never met, but whose story had shaped his approach to the mountains.

In Granite Falls, life moved on, but the memory of Dererick’s case remained present.

The town had always been a place where climbers and hikers passed through, drawn by the peaks and the wilderness, and the locals had long ago accepted that tragedy was part of that landscape.

But Dererick’s death had been different somehow, more visible, more documented, and the image of his body on the ledge captured by the drone had entered the collective consciousness of the community.

People still talked about it in the coffee shop, at the ranger station, and around campfires.

Some saw it as a ghost story, a warning to those who ventured too far.

Others saw it as a testament to the power of persistence, the fact that Derek had survived for days in a place where most would have given up.

In the summer of 2018, a filmmaker from California named Monica Ruiz arrived in Granite Falls with a small crew.

She was working on a documentary about the intersection of technology and wilderness rescue, and she had heard about the Pullman case.

She reached out to Sheriff Baxter, who was now retired, and asked if he would be willing to participate in an interview.

Baxter was initially reluctant, but after some consideration, he agreed.

The interview took place on the porch of his home, a modest cabin on the outskirts of town with a view of the mountains.

Monica asked him about the search, the recovery, and the impact the case had had on him personally.

Baxter spoke slowly, choosing his words carefully.

He said that the hardest part had not been the technical challenge of retrieving Dererick’s body, but the knowledge that they had been searching in the wrong places for months while he was up there alone waiting.

He said it haunted him to think that if the drone had been deployed earlier, they might have found him in time.

Monica asked if he thought Dererick could have been saved.

Baxter paused for a long time before answering.

He said that based on the camera footage and the medical evidence, Dererick had probably been alive for at least a week after becoming stranded.

If they had found him within the first few days, there might have been a chance, but the weather had been bad.

The search area had been vast, and they had no reason to believe he was on that particular section of the face.

He said it was easy to look back and see what should have been done, but in the moment, they had made the best decisions they could with the information they had.

He said that was all anyone could ever do.

The documentary titled The Ledge was released in early 2019 and screened at several film festivals.

It featured interviews with Baxter, Aaron Vest, Vincent Taber, and Rachel Cove, as well as archival footage of the search and recovery operation.

Jennifer was approached about participating, but declined.

She did not want to relive those months in front of a camera, and she did not want Derek’s story to be reduced to a narrative arc in someone else’s film.

The filmmakers respected her decision and did not press further.

The documentary received positive reviews for its thoughtful approach and its exploration of how technology was changing the nature of wilderness rescue.

Critics praised it for avoiding sensationalism and for treating Derek’s death with dignity, but it also sparked debate within the climbing community.

Some felt that the film placed too much emphasis on the role of the drone and not enough on the human decisions that had led to the tragedy.

Others argued that it was important to highlight the tools that could save lives and that Dererick’s case was proof of their value.

The debate was never fully resolved, but it kept the conversation going, and that in itself had value.

In the years following the documentaries release, several search and rescue organizations across the country began incorporating drones into their standard operating procedures.

Training programs were developed, protocols were established, and the technology became more accessible.

Drones were used to locate lost hikers, survey avalanche debris, and assess dangerous terrain before sending in ground teams.

Lives were saved, and in each case, there was a quiet acknowledgement that the lessons learned from Derek Pullman’s death had contributed to those successes.

In 2020, the CO 19 pandemic brought the world to a halt, and the mountains, like everything else, became a different kind of space.

With gyms and public spaces closed, more people turned to the outdoors for recreation and solace, the trails around Granite Falls saw an influx of visitors, many of them inexperienced, drawn by the promise of open air and solitude.

The Ranger Station was overwhelmed with calls about lost hikers, twisted ankles, and people who had ventured beyond their abilities.

Sheriff Baxter’s successor, a woman named Laura Finch, found herself responding to more incidents in a single summer than the department had seen in years.

The increased traffic brought new risks, but it also brought new awareness.

People who had never thought about mountain safety before were suddenly confronted with its importance.

Climbing organizations saw a surge in enrollment for their courses, and the Derek Pullman Memorial Climbing Fund received a wave of donations from people who wanted to support education and preparedness.

Jennifer, still living in New Mexico, watched the changes from a distance.

She saw the news reports about overcrowded trails and unprepared hikers, and she thought about how Dererick would have responded.

“He would have been patient,” she thought, willing to teach, to share what he knew.

“He had always believed that the mountains belong to everyone, but that everyone had a responsibility to approach them with respect.

” In the fall of 2020, Jennifer received a letter from Gordon and Diane Pullman, Dererick’s parents.

They wrote to tell her that they were donating a portion of Dererick’s life insurance payout to the memorial fund and they wanted her input on how it should be used.

Jennifer was surprised by the gesture.

She had not been in regular contact with Dererick’s parents since the funeral, not out of animosity, but simply because the grief had made it difficult to stay connected.

she wrote back, thanking them and suggesting that the money be used to fund a scholarship for young climbers from underrepresented communities, people who might not otherwise have access to the training and equipment they needed.

Gordon and Diane agreed, and the scholarship was established in early 2021.

By the end of the first year, it had supported five recipients, each of whom wrote thank you letters describing how the opportunity had changed their lives.

Jennifer kept those letters in a folder on her desk, reading them occasionally when she needed a reminder that something good had come from the loss.

In the spring of 2021, the north face of Mount Silverton was climbed by a team of three experienced alenists who were attempting to establish a new route on the wall.

They were aware of Dererick’s story and had studied the incident report carefully.

As they ascended, they passed near the ledge where Dererick had died.

One of the climbers, a woman named Iris, paused there and took a photo.

The ledge was empty now, just bare rock and a few old bolt holes.

She posted the photo on social media with a caption that read, “Stop to pay respects.

The mountain remembers even if it doesn’t speak.

” The post was shared widely and dozens of people commented.

Many of them sharing their own stories of close calls, of moments when luck or skill or the help of others had made the difference.

The climbing community for all its competitiveness and individualism was also a community of shared experience of people who understood that they were all vulnerable in the same way.

If this story has moved you or made you think differently about the risks we take and the bonds we share, please consider sharing it with others who might benefit from hearing it.

Stories like Derek’s remind us that life is fragile and that the connections we make matter more than we often realize.

That summer, Jennifer decided to visit Colorado again.

It had been 4 years since Dererick’s death, and she felt ready to return, not to relive the past, but to see the place with new eyes.

She flew into Denver, rented a car, and drove west into the mountains.

She did not go to Granite Falls.

Instead, she went to Boulder to the apartment she had once shared with Derek.

It had long since been rented to someone else, but she stood outside for a while, looking up at the windows, remembering the mornings they had spent there, drinking coffee, and planning trips.

She visited the climbing gym where they had met, a large warehouse style building filled with artificial walls and the sound of carabiners clinking against harnesses.

The place had expanded since she had last been there with new routes and new faces, but the energy was the same.

She watched the climbers for a while, young and old, experienced and beginner.

All of them focused on the wall in front of them, trusting in their strength and their gear.

She thought about Derek about the first time she had seen him there moving up a difficult route with a kind of effortless grace that had made her stop and watch.

She had introduced herself after he came down and they had talked for an hour about climbing, about photography, about the places they wanted to go.

That conversation had been the beginning of everything.

Before leaving Boulder, Jennifer drove to the cemetery where Dererick was buried.

She had not been there since the funeral, and she was not sure what to expect.

The grave was in a quiet section near the back, shaded by a large cottonwood tree.

The headstone was simple gray granite with his name, dates, and a small engraved image of a mountain.

Someone had left flowers recently, and there were a few small stones arranged on top of the marker, a [clears throat] tradition she had seen before, but did not fully understand.

She knelt down and placed her hand on the stone, feeling the cool surface under her palm.

She did not say anything out loud.

She did not need to.

She had said everything she needed to say in the years since his death.

In the quiet moments alone, in the letters she had written but never sent, in the dreams where he appeared and they talked as if nothing had happened.

She stayed there for a while listening to the wind in the leaves.

And then she stood and walked back to her car.

She drove south back toward New Mexico, back toward the life she had built in his absence.

The road was long and the sky was wide.

News

Ilhan Omar ‘PLANS TO FLEE’…. as FBI Questions $30 MILLION NET WORTH

So, while Bavino is cracking down in Minnesota, House Republicans turning the heat up on Ilhan Omar. They want to…

FBI & ICE Raid Walz & Mayor’s Properties In Minnesota LINKED To Somali Fentanyl Network