A struggling farmer discovered a secret cellar stacked with dozens of gourmet cheese wheels.

But when he sliced one open, the horrifying truth hidden beneath the wax made him turn pale.

And call the police immediately.

Drop a comment with where you’re watching from today.

And don’t forget to subscribe to see what’s coming up next.

The silence of the Miller homestead wasn’t peaceful.

It was a heavy, suffocating weight that pressed against the rotted siding of the barn, holding secrets that had outlived the men who buried them.

Thomas Reed stood in the center of the structure, his breath pluming in the frigid Wisconsin air, looking at the devastation he had just purchased with the last of his savings.

The barn was a cathedral of decay, smelling of wet hay, ancient manure, and the sharp metallic tang of rust.

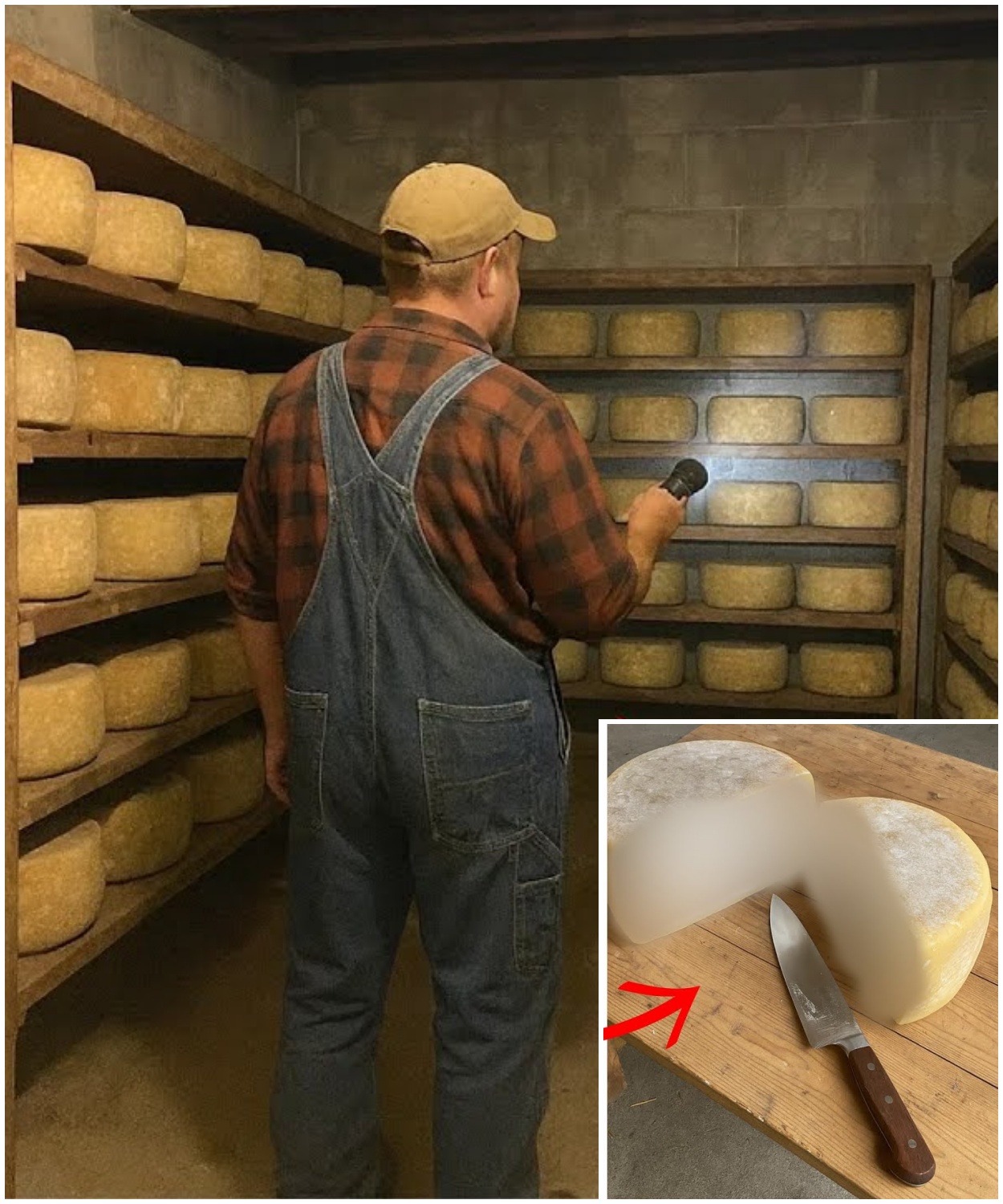

At 38 years old, Thomas was wearing the uniform of a man trying to rebuild a life that had crumbled in the city.

a red and black plaid flannel shirt, heavy denim overalls that were already stained with the grime of renovation, and a tan baseball cap pulled low over eyes that were tired of looking at bank statements.

He clicked his black flashlight on, the beam cutting through the floating dust moes like a solid bar of light.

The bank officer, a man named Mr.

Henderson, who wore suits that cost more than Thomas’s truck, had called this property a fixer upper with potential.

Thomas called it a desperate gamble.

He had leveraged everything, his reputation, his credit score, and the remaining shreds of his dignity to buy this foreclosure in the remote outskirts of Baron County.

The plan was simple on paper, but grueling in reality.

renovate the barn, bring in a herd of dairy cattle, and start producing high yield organic milk before the balloon payment on the loan hit in six months.

If he failed, he wasn’t just bankrupt.

He was erased.

The work for the day was demolition.

The concrete floor of the main aisle was cracked and heaving, likely from decades of frost heave and neglect.

Thomas gripped his pike pole, a heavy steel tool used for leveraging logs and breaking ice, and drove it into a fissure in the concrete.

He expected the dull thud of metal on Earth.

Instead, the impact produced a strange resonant boom, a hollow sound that vibrated up the handle and into his forearms.

He paused, the silence of the barn rushing back in to fill the space.

He tapped the spot again.

Thump, echo.

It wasn’t solid ground.

It sounded like a drum.

Drainage, he muttered to himself, his voice sounding small in the vast vaulted space.

He dropped to his knees, ignoring the cold, dampness soaking into his denim.

He began to clear away the layer of compacted straw and muck that had hardened over the years into a geological stratum of filth.

He used a flat shovel, scraping aggressively.

As the grime cleared, the gray concrete gave way to the distinct outline of a seam.

It wasn’t a crack.

It was a deliberate cut in the floor.

He brushed away the remaining dirt with his gloved hands, revealing a heavy steel trap door, roughly 3 ft by 3 ft, set flush with the floor.

It was an industrial installation, far too heavyduty for a simple root cellar or a drainage access.

The steel was pitted with rust, but thick, and securing it was a massive hasp held shut by a padlock the size of a grapefruit.

The lock was an old master model, the kind with a laminated steel body, but it was fused into a single lump of corrosion.

Thomas sat back on his heels, wiping sweat from his forehead despite the freezing temperature.

The farmhouse had come with no keys for outbuildings, and the deed hadn’t mentioned a basement in the barn.

In Wisconsin, barn sellers were rare due to the high water table.

You built up, not down.

He grabbed the pike pole again and jammed the tip into the Ubar of the padlock, leveraging his entire body weight against it.

He groaned, the veins in his neck bulging, but the steel didn’t budge.

The rust had welded the mechanism shut, but the shackle itself was hardened boron alloy.

It wasn’t going to break for a farmer with a stick.

“Fine,” Thomas said, standing up and dusting off his knees.

“Have it your way.

” He needed hydraulic cutters.

The nearest rental shop was in Rice Lake.

a 40-minute drive on icy back roads.

A rational man might have ignored the door, poured the new concrete over it, and moved on with the schedule.

But Thomas was not feeling rational.

He was feeling the gnawing curiosity of a man who needed a win, no matter how small.

A hidden cellar meant storage space, perhaps old tools he could sell, or maybe just answers to why this farm had sat empty for 10 years.

The drive to Rice Lake was a blur of gray sky and white fields.

Thomas’s mind drifted to the rumors he’d heard in town.

When he bought the place, Elias, the owner of the local hardware store, had given him a strange look.

Miller place, huh? Elias had said, counting out nails with maddening slowness.

Old man Miller wasn’t much for farming in his later years.

Kept to himself.

A lot of trucks coming and going at night, though.

Then he just wasn’t there.

Thomas had dismissed it as small town gossip, the kind that fills the void when nothing interesting happens for a decade.

Now with the image of that reinforced trap door in his mind, Elias’s words felt heavier.

He returned 2 hours later, the bed of his truck weighed down by a bright orange hydraulic cutter case.

The sun was beginning to dip, casting long skeletal shadows through the gaps in the barn’s siding.

Thomas hauled the equipment to the spot, hooked up the pneumatic hose, and positioned the jaws of the cutter around the rusted shackle of the lock.

He primed the trigger.

The machine winded, a high-pitched mechanical scream that startled the pigeons nesting in the rafters.

The jaws clamped down.

For a second, the lock held, defying the thousands of pounds of pressure.

Then, with a sound like a gunshot that echoed violently off the tin roof, the shackle snapped.

The heavy lock fell to the concrete with a dead thud.

Thomas set the tool aside, his heart hammering against his ribs.

He hooked his fingers under the lip of the trap door and pulled.

It was immensely heavy, the hinges screaming in protest as they ground against years of oxidation.

He had to use his legs driving upward until the door finally flipped back, crashing against the floor with the cloud of dust.

He waved his hand in front of his face, coughing.

The air that rose from the hole wasn’t the foul stench of sewage or the earthy smell of potatoes.

It was dry, shockingly dry, and it carried a faint chemical scent, sterile, acidic, like a hospital mixed with a mechanic shop.

He retrieved his flashlight and shined it down.

A set of wooden stairs, sturdy, and well-built, descended into the gloom.

“Hello,” he called out.

It was a reflex, a stupid one.

If anyone was down there, they had been down there for 10 years.

He took the first step.

The wood held.

He took another.

The temperature dropped noticeably as he descended below the frost line when his boots hit the concrete floor of the cellar.

He swept the light around and his breath caught in his throat.

This wasn’t a hole in the ground.

It was a bunker.

The walls were lined with cinder blocks, expertly mortared, but it was the contents that made his mind real.

The room was roughly 20 ft long and lined from floor to ceiling with sturdy wooden racks, and on every single shelf, spaced with military precision, were wheels, dozens of them, hundreds perhaps.

Thomas walked forward, his light dancing over the yellow surfaces.

They looked exactly like large wheels of gourmet cheese, parmesan, or perhaps a heavy Gouda.

They were coated in a thick yellowish wax, uniform in size, each one about 18 in in diameter and 8 in thick.

He stood in the center of the room, spinning slowly.

if this was vintage cheese properly aged and stored in a consistent environment.

The math began to race through his head.

Artisan wheels of this size could sell for two, maybe $3,000 a piece to the right buyer in Chicago or Minneapolis.

He did a quick count of one rack, 20 wheels.

There were 10 racks, 200 wheels, $400,000.

Thomas felt a laugh bubble up in his chest.

A hysterical sound that bounced off the cold walls.

He had bought a money pit and found a literal treasure chest.

It was the kind of luck that didn’t happen to people like Thomas Reed.

It was a divine apology for the divorce, the bankruptcy, the lonely nights, and the drafty farmhouse.

He approached the nearest shelf and reached out to touch one of the wheels.

The wax was smooth, cold, and hard.

He gripped the sides to lift it.

He grunted.

It was heavy, heavier than cheese should be.

He had worked on a dairy farm in his youth.

He knew the density of kurd.

A wheel this size should weigh perhaps 40 lb.

This felt closer to 60 or 70.

Dance, he whispered.

super aged.

He hauled the wheel off the shelf, straining his lower back, and cradled it against his chest.

He needed to get it into the light.

He needed to see the stamp, the date, the maker’s mark.

Climbing the stairs with the heavy wheel was a struggle, but adrenaline fueled him.

He emerged into the twilight of the barn, kicking the trap door shut behind him.

A new instinct of protectiveness taking over.

He carried the wheel out of the barn and across the frozen yard to the farmhouse kitchen.

He set the wheel down on his scarred oak dining table.

Under the harsh light of the overhead fixture, the object looked innocuous, just a big yellow cylinder.

But the discrepancies began to nag at him immediately.

He examined the wax.

Usually a cheese maker would stamp the wax with a date, a batch number, or a logo.

There was nothing here.

The yellow coating was perfectly smooth, almost industrial.

He went to the refrigerator and grabbed a beer, cracking it open and taking a long pull while he stared at the wheel.

He needed a second opinion, but he was wary.

If he told someone, would the bank claim it? Did the sale of the house include cattle left behind? He needed to know what he had before he announced it to the world.

He thought of Dr.Sarah Jenkins.

She was the local large animal vet, a sharp-witted woman who had been the only person in town to welcome him without the side eye.

She knew dairy science better than anyone.

He pulled out his phone, his thumb hovering over her contact.

He typed, “Found something weird in the barn.

Can you talk?” He deleted it.

Too vague.

Found old cheese stock.

Need safety check.

He deleted that, too.

If this was worth half a million dollars, he couldn’t just text about it.

He put the phone down and went to his utensil drawer, pulling out a pairing knife.

He decided to do a scratch test.

He dug the tip of the knife into the wax rim.

A curled shaven of yellow wax peeled away.

Beneath it, the surface was white.

He touched the exposed white substance.

It felt dry.

He rubbed it between his thumb and forefinger.

It didn’t smear like fat.

It crumbled slightly, chalky and fine.

Overaged, he reasoned, dried out.

But the doubt was a cold worm in his gut.

He grabbed his large butcher knife, the one with the heavy black handle.

He positioned the blade over the center of the wheel.

If the cheese was this hard, he’d need a hammer to drive the knife through.

He lined up the blade and struck the back of it with the heel of his hand.

He expected resistance.

He expected the knife to bounce or get stuck in the dense casein structure of aged dairy.

Instead, the knife sank in with a dull shuck sound.

It moved through the material with a terrifying smoothness, like cutting through dense clay or wet sand.

Thomas frowned.

He wiggled the knife and pulled it free.

The blade came out, coated in white powder, not cheese crumbs.

He stared at the knife.

He stared at the slit in the wheel.

With a trembling hand, he inserted the knife again and sliced, carving out a wedge.

The wax cracked, and a chunk of the interior fell onto the table.

It wasn’t cheese.

It wasn’t even food.

It was a solid, compressed brick of white powder.

Thomas froze.

The silence of the farmhouse suddenly felt like a scream.

He looked at the white junk.

He looked at the hundreds of thousands of dollars he thought he had found.

He wet his finger and touched the powder, then touched it to his gums.

It was an old habit from movies, something he did without thinking.

Instant numbness.

A cold chemical freeze spread across his lip and tongue.

Thomas Reed scrambled back from the table, his chair screeching against the lenolum.

He backed up until he hit the counter, his chest heaving.

“No,” he whispered.

“No, no, no.

” This wasn’t cheese.

It was cocaine.

Pure, uncut, compressed cocaine.

And he had a seller full of it.

He did the math again, but this time the numbers weren’t a blessing.

They were a death sentence.

50, maybe 60 kilos in the cellar.

Street value, millions, tens of millions.

He wasn’t standing on a fortune.

He was standing on a graveyard.

He ran to the window and looked out at the barn.

The dark structure loomed against the night sky, no longer a project, but a vault of radioactive material.

And then he saw it.

Headlights far down the gravel road, moving slowly.

A car was approaching.

Not a truck, a car, a sedan.

Thomas felt the blood drain from his face.

He remembered the black sedan he had seen earlier in the week, driving past slowly.

He had assumed they were lost city folk looking for the highway.

But they hadn’t been lost.

They had been checking.

They knew.

Someone knew the farm had been sold.

Someone knew the bank was open again.

Thomas dropped to the floor, crawling below the window line.

He scrambled for his phone, his fingers fumbling with the screen.

He needed to call the sheriff.

He needed to call the DEA.

He needed the National Guard.

But as he tapped the screen, the signal bars at the top were dead.

No service, he cursed.

The valley was a dead zone on good days, and with the heavy cloud cover rolling in, the signal was gone.

The landline, he hadn’t connected it yet.

The technician was scheduled for next Tuesday.

He was alone.

He peakedked over the window sill.

The car had stopped at the end of his driveway about 200 yd out.

It sat there idling, the lights cutting through the darkness.

Then the lights turned off.

They weren’t leaving.

They were waiting.

Thomas looked at the block of cocaine on his table.

He grabbed it, panic, making his movements jerky, and threw it into the trash can, then realized how stupid that was.

He retrieved it and shoved it into the back of the freezer behind a bag of frozen peas.

He needed a weapon.

He didn’t own a gun.

He had sold his shotgun to pay for the moving van.

He had a house full of renovation tools, a hammer, a pry bar, the hydraulic cutter in the barn, the barn.

The trap door was closed but not locked.

He had broken the lock.

If they went into the barn and saw the fresh concrete dust, the broken lock, the disturbed floor, they would come to the house.

they would come for him.

He had to secure the barn.

Thomas grabbed his heavy coat and slipped out the back door.

The cold air hit him like a physical blow.

He moved in a crouch, using the bulk of the tractor shed to shield him from the driveway.

He could hear the wind howling through the spruce trees, masking the sound of his boots on the crunching snow.

He reached the side door of the barn and slipped inside.

The darkness was absolute.

He didn’t dare turn on his flashlight.

He navigated by memory, his hands trailing along the rough wood of the stalls.

He reached the center aisle.

He could see the trap door, a darker square against the floor.

He needed to cover it.

He grabbed a heavy tarp he had used for painting, and dragged it over the hole.

Then he began to pile heavy bags of concrete mix on top of it.

One bag.

Two bags.

50 lbs each.

He was sweating, his breath coming in ragged gasps.

Creek.

The sound came from the main barn doors, the large sliding doors at the front.

Thomas froze.

He was exposed in the middle of the aisle.

The door slid open a few inches.

A beam of light far stronger than his own flashlight sliced into the barn.

that swept across the rafters, the stalls, the pile of renovation debris.

Check the floor, a voice said, low, grally.

He was working in here today.

Saw him hauling equipment.

You think he found it? A second voice asked.

Younger, nervous.

If he found it, he’s a dead man.

If he hasn’t found it, he’s a dead man anyway.

Can’t have witnesses living on top of the stash.

Thomas felt his stomach drop.

There was no negotiation here.

They weren’t here to buy him off.

They were here to clean up loose ends.

He quietly moved backward, stepping into one of the old milking stansions.

He needed to get to the loft, high ground.

The two men entered the barn.

Thomas could see their silhouettes against the starlight from the open door.

They were holding suppressed pistols.

The long cylindrical shapes on the ends of the barrels made them look like toys, but Thomas knew they were anything but.

Smells like he’s been grinding metal, the first man said.

The light swept toward the center of the room.

It hit the pile of concrete bags Thomas had just stacked.

Fresh stack, the man noted.

Right over the drop point.

He knows.

Clear the barn.

Then we hit the house.

Thomas was halfway up the ladder to the hoft when his boot slipped on a rung slick with frost.

He caught himself, but his other boot kicked the side of the ladder.

Clung.

The sound was deafening.

Up top.

Two beams of lot snapped up, blinding him.

A thip, thip sound tore through the air, and splinters of wood exploded from the beam next to Thomas’s head.

He scrambled up, rolling onto the dusty floor of the loft.

He was trapped.

There was no way out of the loft except the ladder or jumping 20 ft to the frozen ground outside the hay door.

He crawled behind a stack of old hay bales left by the previous owner.

He needed a distraction.

He needed a weapon.

His hand brushed against something cold and metal in the straw.

The pitchfork.

It was old, the handle brittle, but the tines were sharp.

It was useless against guns.

He looked around frantically.

The loft was filled with junk.

old pulleys, ropes, a stack of heavy oak boards, and the loading winch.

The barn had an old hay trolley system on a track that ran the length of the roof peak.

A heavy iron claw hung from it, positioned right over the center aisle where the men were standing.

Thomas looked at the rope tied to the cleat on the wall next to him.

It was the release line for the claw.

He could hear the men moving below.

I’m going up.

You watch the drop.

Just toss a flare up there.

Burn them out.

No fire.

Ruins the product in the cellar.

I’m going up.

The ladder creaked.

The man was coming.

Thomas grabbed the rope.

It was stiff with age.

He prayed the trolley track wasn’t rusted solid.

He crawled to the edge of the loft, peering through a gap in the floorboards.

The second man was standing directly below the opening, guarding the floor.

The first man was halfway up the ladder.

Thomas waited.

He needed the man on the ladder to be closer.

He needed him to commit.

The man’s head crested the loft floor.

The flashlight beam swept the space.

“I see him,” the man said, raising his weapon.

Thomas didn’t wait.

He grabbed a heavy oak plank he had been saving for the floor repair and shoved it with all his might.

It slid across the floorboards and slammed into the top of the ladder.

The ladder wasn’t bolted down.

It was just hooked over the edge.

The impact knocked the hooks free.

With a shout, the gunman fell backward.

He flailed, his gun discharging into the roof and crashed to the floor below.

A sickening crunch echoed through the barn.

“Mikey!” the second man screamed, spinning around.

Thomas stood up and grabbed the release rope for the hayclaw.

He wrapped it around his hands and yanked it with every ounce of strength he possessed.

The rusty mechanism groaned, then released.

The heavy iron claw, weighing nearly 100 lb, dropped from the peak of the roof like a meteor.

It didn’t hit the second man directly.

Thomas wasn’t that lucky, but it smashed into the pile of concrete bags right next to him, exploded them into a massive cloud of gray dust.

The man coughed, blindingly firing his weapon into the cloud.

You son of a Thomas didn’t wait to see the result.

He ran to the rear hay door, unlatched it, and kicked it open.

The drop was 15 ft into a snow drift.

He jumped.

The landing knocked the wind out of him, the cold snow packing into his shirt, but he rolled and scrambled to his feet.

He ran toward the woods line, putting the barn between him and the driveway.

He needed to get to the road.

He needed to get to a neighbor.

The nearest house was 2 mi away, the Anderson place.

He ran through the deep snow, his lungs burning.

Behind him, he heard the roar of an engine, the sedan.

They were coming after him.

He dove into the ditch as the headlights swept the field.

They were driving on the field, the heavy car crushing the dead cornstalks.

They were hunting him like a deer.

Thomas scrambled up the embankment and into the dense pine forest that bordered his land.

The car couldn’t follow him there.

He leaned against a tree, gasping, his heart feeling like it was going to explode.

He fumbled for his phone again.

He held it up to the sky.

One bar flickering.

He dialed 911.

Emergency.

What is your location? Miller Farm.

Thomas gasped.

County Road B.

Men with guns.

Cocaine.

Seller.

Sir, repeat that.

Did you say cocaine? Send the police.

Send everyone.

They’re shooting at me.

Sir, stay on the line.

The battery died.

The cold had drained the last of the charge.

Thomas stared at the black screen.

He was on his own.

He couldn’t run two miles in this snow before they circled around and cut him off on the road.

He had to go back.

He knew the terrain.

They didn’t.

He circled back through the woods, moving toward the farmhouse.

He saw the sedan stopped near the woods line.

The driver scanning the trees with the spotlight.

The other man, the one who had fallen, was likely incapacitated or dead.

That meant one active shooter.

Thomas crept toward the tractor shed.

Inside was his old diesel tractor.

It had a block heater that he hadn’t plugged in, so it wouldn’t start quickly, but next to it was his stash of renovation chemicals.

Muriatic acid for cleaning the concrete, ammonia for cleaning the walls.

He grabbed two jugs.

He didn’t know much about chemistry, but he knew you didn’t mix them, and he knew that in a confined space, they created a cloud of mustard gas.

He moved toward the house.

The gunman had left the car and was moving toward the back door of the house, kicking it in.

He was looking for Thomas inside.

Thomas sprinted to the car.

The engine was running.

He reached in and grabbed the keys, ripping them from the ignition.

He threw them as far as he could into the snow-covered field.

The gunman heard the door slam.

He came running out of the house shouting.

Thomas ran for the barn again.

It was the only defensible structure.

He scrambled back up the snowbank and through the side door he had used earlier.

He climbed the wall framing to get back to the loft.

The ladder was down.

He pulled himself up, his muscles screaming.

The gunman entered the barn below.

I know you’re in here.

There’s nowhere to go.

You give me the key to the cellar and I make it quick.

Thomas uncapped the muriatic acid.

He uncapped the ammonia.

Come and get it, Thomas yelled.

The man moved under the loft, raising his gun.

Thomas poured the acid over the edge.

Then he poured the ammonia.

The liquid splashed onto the concrete floor below, mixing in a frothing puddle.

Immediately, a thick white vapor began to rise.

It hissed.

The gunman coughed.

“What the?” Then the gas hit him.

Chlorine gas.

It seared the lungs, dissolved the mucous membranes, and blinded the eyes.

The man screamed, a horrible gurgling sound.

He fired his gun wildly, bullets pinging off the metal roof, but he dropped to his knees, clawing at his throat.

He crawled toward the door, wretching, unable to breathe.

Thomas covered his mouth with his shirt and buried his face in the hay, praying the gas wouldn’t rise fast enough to get him, too.

He lay there for what felt like hours, listening to the wind and the wheezing of the man below until sirens cut through the night.

Not one siren, dozens.

Blue and red lights washed over the interior of the barn, illuminating the floating dust and the deadly gas cloud.

Federal agents, come out with your hands up.

Thomas crawled to the hay door and waved his hand.

I’m up here.

Don’t go in there.

Gas.

There’s gas.

The next few hours were a blur of hazmat suits, tactical teams, and handcuffs.

Thomas was dragged out, decontaminated, and shoved into the back of a SWAT van.

He sat there shivering in a blanket, watching his farm turn into a war zone.

They brought the cheese wheels up.

One by one, they stacked them in the yard like trophies.

A field test confirmed it immediately.

High purity cocaine.

The DEA agent in charge, a tall woman with tired eyes, looked at the hall and shook her head.

“10 years,” she said to her colleague.

“We’ve been looking for the Milwaukee shipment for 10 years.

It was sitting under a dairy barn the whole time.

” She walked over to the van where Thomas was sitting.

The door opened.

“You, Thomas Reed?” she asked.

He nodded, his teeth chattering.

You have a hell of a renovation style, Mr.

Reed.

You realize you just secured the largest seizure in Baron County history.

I just wanted to make cheese, Thomas whispered.

Well, she said, looking at the dead gunman being loaded into a coroner’s van.

You definitely made something.

6 months later, the snow had melted, revealing the rich black earth of the farm.

The barn had a new roof.

The siding was painted a deep classic red.

Thomas stood by the fence watching a herd of 20 Holstein grazing in the pasture.

The settlement from the state, a finders fee encoded in the asset forfeite laws had been substantial.

More than that, the media writes for the story the cocaine crearyy had paid off the mortgage entirely.

Dr.

Sarah Jenkins leaned on the fence next to him.

They look good, Thomas putting on weight.

They’re eating better than I am.

Thomas smiled.

It was a real smile.

The first one that had reached his eyes in years.

“You ever go down there?” she asked, nodding toward the barn.

“Filled it in?” Thomas said, poured 5 yards of concrete into that hole.

Whatever ghosts were left down there are buried for good.

He looked at his hands.

They were calloused, scarred, but steady.

He had come here looking for a fortune in cheese.

He hadn’t found it.

But looking at the cows, the repaired barn, and the green field stretching out under the Wisconsin sun, he realized he had found something else.

He had found a life.

And this time he had fought for it.

Come on, Thomas said, pushing off the fence.

Time to milk the real way.

He walked toward the barn, the shadow of the past finally gone, leaving only the work of the day ahead.

News

Ilhan Omar ‘PLANS TO FLEE’…. as FBI Questions $30 MILLION NET WORTH

So, while Bavino is cracking down in Minnesota, House Republicans turning the heat up on Ilhan Omar. They want to…

FBI & ICE Raid Walz & Mayor’s Properties In Minnesota LINKED To Somali Fentanyl Network

IC and the FBI move on Minnesota, touching the offices of Governor Tim Walls and the state’s biggest mayors as…

FBI RAIDS Massive LA Taxi Empire – You Won’t Believe What They Found Inside!

On a Tuesday morning, the dispatch radios in hundreds of Los Angeles taxi cabs suddenly stopped playing route assignments. Instead,…

Brandon Frugal Finally Revealed What Forced Production to Halt in Season 7 of Skinwalker Ranch….

The Secret of Skinwalker Ranch became History Channel’s biggest hit. Six successful seasons documenting the unknown with real science and…

1 MINUTE AGO: What FBI Found In Hulk Hogan’s Mansion Will Leave You Shocked….

The FBI didn’t plan to walk into a media firestorm, but the moment agents stepped into Hulk Hogan’s Clearwater mansion,…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage… It started like any other evening…

End of content

No more pages to load