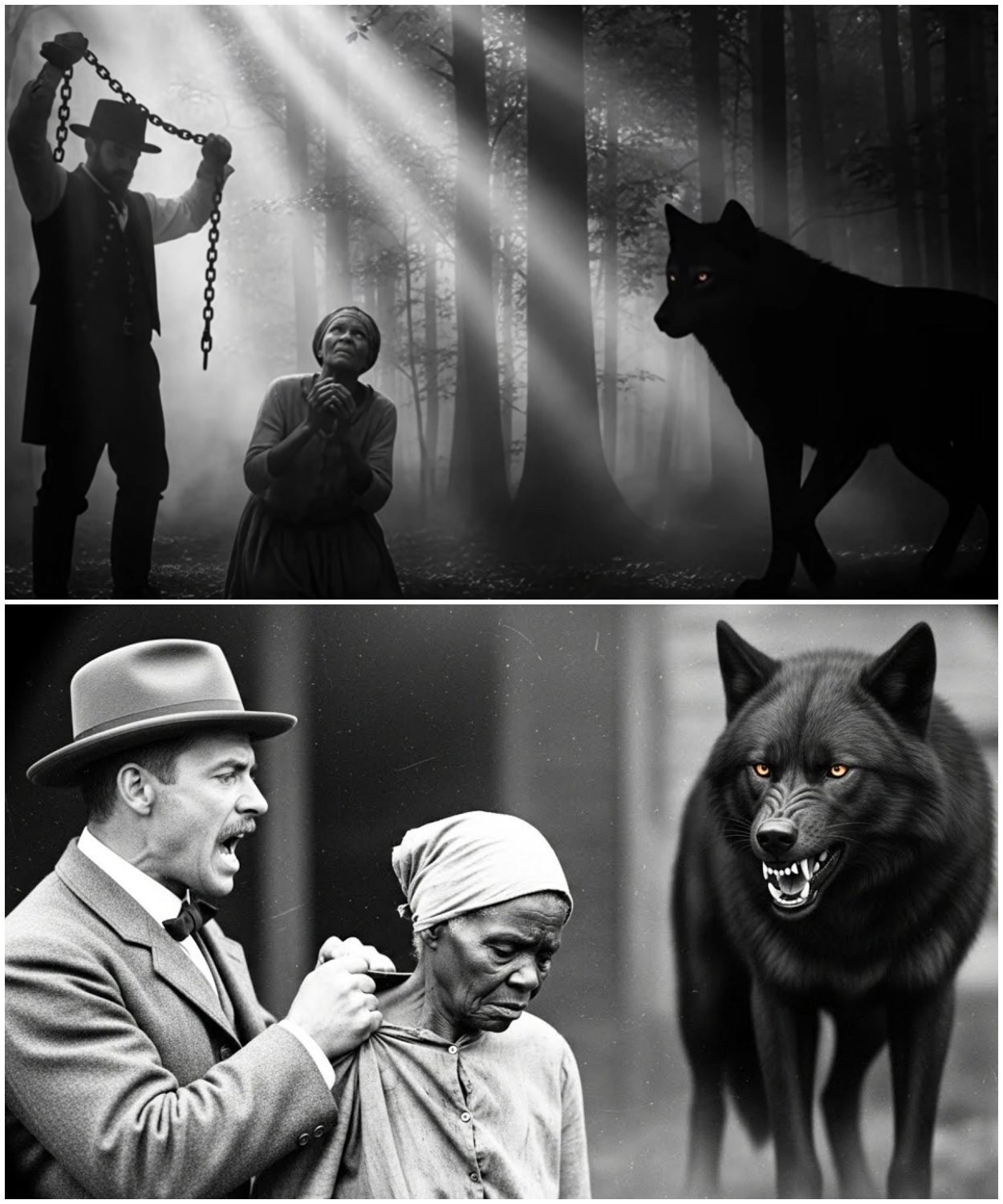

Foreman humiliated an elderly enslaved woman – until an ALPHA WOLF appeared, and no one believed it

Alabama, 1887.

An elderly enslaved woman knelt in the mud while a wealthy plantation owner kicked dirt into her face.

She did not flinch.

She did not cry out.

Her silence made him angrier.

He raised his boot again.

Then the howl came.

Deep, guttural, close.

The kind of sound that makes grown men freeze.

Something massive moved in the darkness beyond the torch light.

Eyes like molten gold watched from the treeine.

The old woman whispered two words that made the plantation owner’s blood run cold.

My son.

But her son had been dead for 15 years.

Everyone knew that.

What they didn’t know was where his spirit had gone or what it had become or why it had returned tonight.

Her name was Alma.

She was 63 years old.

Her back was crooked from decades of cottonpicking.

Her hands were twisted like tree roots.

She could barely walk without pain shooting through her knees.

The Thornhill plantation sat 12 mi outside Montgomery.

200 acres of cotton fields.

A main house with white columns.

Slave quarters that leaked when it rained.

17 enslaved people still worked the land even though the war had ended 22 years ago.

They stayed because they had nowhere else to go.

Because James Thornnehill owned everything for miles.

Because leaving meant starving because men who tried to leave were found hanging from trees.

James Thornnehill inherited the plantation from his father.

He was 35 years old, clean shaven, always wore a black suit.

He believed slavery was the natural order of things.

He believed God had made some people to serve and others to rule.

When the Emancipation Proclamation came, his father had laughed.

When reconstruction ended, his father had celebrated.

Now James ran things the same way his grandfather had, with violence, with fear, with total control.

Alma had been born on this land.

She had picked cotton since she was 5 years old.

She had watched her mother die in childbirth.

She had buried three children before they turned 10.

Only one had survived to adulthood.

His name was Thomas.

He had been tall, strong, quick with numbers.

He could read, though that was forbidden.

Alma had taught him in secret using a Bible she had stolen from the main house.

Thomas had disappeared 15 years ago.

He was 19 years old when it happened.

One day he was working in the fields.

The next day he was gone.

James Thornhill’s father said Thomas had run away.

But Elma knew better.

She had found blood on the barn floor.

She had seen the fear in the other worker’s eyes.

Nobody talked about what really happened.

Talking meant dying.

Something else had appeared after Thomas vanished.

A wolf, massive, black fur, golden eyes.

It was seen near the plantation at night.

It never attacked the enslaved people.

But three overseers had died over the years, mauled, torn apart, found in pieces.

James Thornnehill doubled the night patrols.

He set traps.

He hired hunters.

The wolf was never caught.

It was never even seen clearly, just shadows, just howls, just the aftermath.

Elma believed her son’s spirit lived in that wolf.

The others thought she was crazy from grief.

But she felt it.

Every time the wolf appeared, she felt Thomas near her, watching, waiting, protecting.

Tonight would prove her right.

The day started like any other.

Alma woke before dawn in the slave quarters.

A wooden shack she shared with three other women.

The roof had holes.

Rain came through.

The floor was dirt.

There were no beds, just piles of straw and torn blankets.

She could see her breath in the cold air.

Her body screamed when she stood up.

Every joint hurt, every muscle achd.

She was too old for this work, but stopping meant punishment or worse.

She walked to the well outside.

The sun was just starting to rise.

Orange light spread across the cotton fields.

The plantation was quiet except for roosters crowing.

She drew water from the well.

Her hands shook.

The bucket was heavy.

She spilled half of it carrying it back.

James Thornnehill was already awake.

She could see lamplight in the main house windows.

He woke early every day to inspect the plantation to make sure his property was in order.

that included the enslaved people.

Elma went to the main house kitchen.

She was supposed to help cook breakfast.

Her job was to peel potatoes and wash dishes.

Simple tasks for someone her age.

But even simple tasks hurt now.

The cook was a woman named Ruth, 40 years old.

Ruth had been on the plantation her whole life, too.

She moved quickly around the kitchen, cutting, stirring, checking the fire.

You look tired, Ruth said.

I am always tired, Elma replied.

Master Thornhill was asking about you yesterday, saying you move too slow, saying you are useless.

Alma said nothing.

She picked up a potato and started peeling.

Her hands cramped.

The knife slipped.

She cut her thumb.

Blood dripped onto the potato.

Careful, Ruth said.

Do not bleed on his food.

Elma wrapped her thumb in a rag.

She continued peeling.

The pain in her hands got worse.

She dropped the knife twice.

James Thornnehill came into the kitchen.

He was dressed in his black suit.

His boots were polished.

His hair was sllicked back with oil.

He looked at Elma with disgust.

“Why is she still working in here?” he asked Ruth.

“She helps me, Master Thornnehill.

She does what she can.

She does nothing.

Look at her.

She can barely hold a knife.

Alma kept her eyes down.

She had learned long ago not to look plantation owners in the eye.

It was seen as disrespect.

Disrespect meant beatings.

“I can work, master,” Elma said quietly.

“You are a waste of space, a waste of food.

You should have died years ago.

” The words hit Alma like fists, but she showed no emotion.

showing emotion gave men like James Thornnehill satisfaction.

“Get out of my kitchen,” he said.

“Go feed the pigs.

” “At least you are good for that.

” Elma sat down the potato.

She wiped her hands on her dress.

She walked out of the kitchen.

Her legs barely held her weight.

She moved slowly across the yard toward the pig pens.

The sun was higher now.

Other enslaved people were starting their work.

Men headed to the fields with tools.

Women carried laundry to the wash house.

Children fetched water.

Everyone moved with their heads down.

Nobody spoke unless spoken to.

The pig pen was behind the barn.

Six pigs lived there in filth.

The smell was overwhelming.

Elma picked up a bucket of slop.

Kitchen scraps mixed with water.

She poured it into the feeding trough.

The pigs rushed over, squealing and pushing each other.

Elma stood there watching them.

These animals lived better than she did.

They were fed.

They were kept for a purpose.

When they died, it was quick.

A knife to the throat, then meat for the table.

She thought about Thomas.

About the last time she saw him.

He had been carrying water to the fields.

He had smiled at her.

That smile was the last good thing she remembered.

A voice broke her thoughts.

still alive old woman.

She turned.

It was Silas, one of the overseers, a white man in his 40s.

Scars on his face, a whip on his belt.

He enjoyed hurting people.

Everyone knew it.

Yes, sir.

Alma said, “Surprised you made it through the winter.

Thought you would freeze to death in that shack.

” I am still here for now.

He stepped closer.

You know what I think? I think Master Thornhill should sell you, get some money for you before you drop dead.

Maybe a work farm would take you, work you until you are bones.

Alma said nothing.

Or maybe we should just put you down like an old dog.

Would be a mercy really.

He laughed.

Then he walked away.

His boots made sucking sounds in the mud.

Alma stood there shaking, not from fear, from rage.

A rage she had carried for 63 years.

A rage she had to swallow every single day just to survive.

She walked back toward the slave quarters.

Her morning work was done.

Now she would rest until afternoon when there would be more tasks.

Mending clothes, washing floors, whatever Master Thornhill decided.

But as she passed the barn, she heard voices, angry voices.

She stopped.

You are telling me we lost three chickens last night? It was James Thornnehill.

Yes, sir.

Another overseer.

A younger man named Porter.

Something got into the coupe, killed them, but did not eat them.

What killed them? Do not know, sir.

Could be a fox.

Could be that wolf.

Silence.

The wolf, James Thornnehill said slowly.

That damn wolf.

We set traps around the property, but it never steps in them.

It is like it knows.

Animals do not know about traps.

You are setting them wrong.

We followed the tracks last time.

They led to the woods.

Then they just vanished.

James Thornhill was quiet for a moment.

Double the patrols tonight.

I want men with rifles.

If that wolf comes back, I want it dead.

You hear me? Yes, sir.

And check the slave quarters.

Make sure none of them are feeding it.

Make sure none of them are protecting it.

You think they would? I think they are animals, too.

And animals stick together.

Elma moved away from the barn before they saw her.

Her heart was pounding.

The wolf had been here last night.

Close.

Closer than it had been in months.

She thought about Thomas again, about the blood in the barn, about the stories the old people used to tell.

Stories about spirits, about transformation, about justice that came from the earth itself when human justice failed.

Maybe she was crazy.

Maybe grief had broken her mind.

But she believed.

She believed because belief was all she had left.

The day dragged on.

Alma mended a torn dress.

She scrubbed the main house floors.

Her knees screamed with every movement.

By evening, she could barely stand.

Dinner was the same as always.

Cornmeal mush.

A piece of salt pork the size of her thumb.

Water.

She ate in the slave quarters with the others.

Nobody talked much.

Everyone was too tired.

Ruth sat next to her.

You should be careful.

Ruth whispered.

Why? Master Thornhill is in a mood.

I heard him talking to his wife.

He said he wants to clear out the old and useless.

Make room for new workers.

He cannot buy new workers.

Slavery is over.

He does not buy them.

He tricks them.

Promises them wages, then never pays.

And if they try to leave, he has them arrested for theft.

Says they stole from him.

The sheriff is his cousin.

It always works.

Elma finished her food.

It does not matter.

I will die here anyway, just like everyone else.

Do not say that.

It is true.

Ruth said nothing else.

She knew it was true, too.

Night fell.

Alma lay down on her straw pile.

The other women were already asleep.

She could hear them breathing.

She could hear rats moving in the walls.

She closed her eyes, but sleep did not come.

She thought about Thomas, about the wolf, about James Thornnehill’s words earlier.

You should have died years ago.

Maybe he was right.

Maybe she should have.

What was the point of this life? What was the point of suffering with no end? Then she heard it, a howl, long, low, mournful.

The wolf.

She sat up.

The other women stirred but did not wake.

Elma stood.

Her body protested but she ignored it.

She walked to the door.

She opened it slowly.

The night was cold.

Stars filled the sky.

The moon was almost full.

She could see the fields, the barn, the main house in the distance.

Another howl.

Closer this time.

Alma stepped outside.

She walked toward the sound.

Her feet were bare.

The ground was cold and muddy.

She did not care.

She passed the pig pen.

The pigs were agitated.

They squealled and ran in circles.

Something had spooked them.

She reached the edge of the cotton fields.

The stalks were dead now, harvested months ago.

The field was just empty dirt and dried plants.

Movement in the darkness.

Something massive low to the ground.

The wolf stepped into the moonlight.

It was bigger than any wolf should be, taller than her waist.

Its fur was black as ink.

Its eyes glowed gold.

Steam rose from its mouth in the cold air.

Elma stood still.

She was not afraid.

She had never been afraid of this wolf.

Thomas, she whispered.

The wolf stared at her.

Its eyes were intelligent, aware.

They were not the eyes of an animal.

Tears ran down Alma’s face.

Is it really you? The wolf took a step closer.

Then another.

It was 10 ft away now.

She could smell it.

Wild, earthy, like the forest.

They killed you, she said.

They killed you and they lied about it and I could not do anything.

I could not save you.

The wolf lowered its head.

A sound came from its throat.

Not a growl.

something softer, almost like a whimper.

Elma took a step forward.

Her hand reached out, shaking, trembling.

The wolf did not move.

Her fingers touched its fur.

It was warm, real, solid.

My son, she cried.

My boy.

A gunshot exploded in the night.

The bullet hit the ground near the wolf.

Dirt sprayed up.

The wolf turned and bolted.

It vanished into the darkness in seconds.

Alma spun around.

James Thornnehill was running toward her with a rifle.

Porter was behind him with a torch.

“Did I hit it?” Thornhill yelled.

“No, sir,” Porter said.

“It is gone.

” Thornhill reached Elma.

He grabbed her by the arm.

His grip was like iron.

What the hell are you doing out here? Nothing, master.

I heard a noise.

You were talking to that animal.

I saw you.

You were talking to it.

No, master.

You were.

He shook her.

Her teeth rattled.

You are feeding it.

You are protecting it.

I am not.

Liar.

He threw her to the ground.

She hit hard.

Her shoulder made a cracking sound.

Pain shot through her body.

Please, she gasped.

That wolf has killed my livestock.

It has killed my men, and you are helping it.

I am not.

I swear.

He kicked her in the ribs.

She coughed.

Blood came up.

Master Thornhill, Porter said.

Maybe we should shut up.

Thornhill pointed the rifle at Alma’s head.

Maybe I should just end this now.

Put you down like the useless animal you are.

Alma looked up at him.

She saw no humanity in his eyes.

Just hate.

Just cruelty.

Do it, she said quietly.

That surprised him.

What? Do it.

Shoot me.

I am ready.

He stared at her.

Then he lowered the rifle.

No, that would be too easy.

You are going to suffer first.

He turned to Porter.

Lock her in the cellar.

No food, no water.

3 days.

Let us see if she is still loyal to that wolf when she is starving.

Porter hesitated.

Sir, she is old.

She might not survive.

Then she dies.

I do not care.

They dragged Alma across the plantation.

Her body screamed in agony.

They opened the cellar door.

It was a hole in the ground beneath the barn, completely dark, completely empty.

It smelled like mold and death.

They threw her down the stairs.

She tumbled, hit the floor, lay there gasping.

The door slammed shut above her.

A lock clicked.

Darkness.

Complete.

Total.

absolute darkness.

Alma lay there for a long time.

She might have passed out.

She was not sure.

When she opened her eyes again, she could not tell if they were open or closed.

It was that dark.

Her ribs hurt.

Her shoulder hurt.

Everything hurt.

She thought she might die here and maybe that would be okay.

But then she heard it again.

faint, distant, but there a howl.

The wolf was still out there.

Thomas was still out there.

And as long as he was out there, she would hold on.

She had to because she realized something in that darkness, something important.

Thomas had not just come back to protect her.

He had come back for revenge.

And that revenge was just beginning.

The cellar was a tomb.

Alma could not see her own hands in front of her face.

The darkness pressed against her like a physical weight.

She tried to stand, but her body would not obey.

Her shoulder was badly injured.

Every breath sent sharp pains through her ribs.

She lay on the cold, dirt floor.

Time became meaningless.

She did not know if minutes or hours were passing.

There was no light, no sound except her own breathing and the occasional scurrying of rats.

Thirst came first.

Her throat became dry, then scratchy, then painful.

She tried to swallow, but there was no moisture in her mouth.

Her tongue felt thick and swollen.

Hunger came next.

Her stomach cramped.

It had been empty when they threw her down here.

Now it twisted and growled.

She tried to ignore it, but the pain grew worse.

The cold was constant.

It seeped into her bones.

She shivered uncontrollably.

Her thin dress provided no warmth.

She curled into a ball trying to preserve body heat.

It did not help much.

Hours passed, or maybe days.

She could not tell.

She drifted in and out of consciousness.

Her mind played tricks on her.

She saw Thomas as a child.

She heard his voice.

She felt his hand in hers.

Then she would wake and remember he was dead, gone, murdered on this plantation 15 years ago.

But the wolf, the wolf was real.

She had touched it.

She had felt its warmth.

That was not a dream.

She thought about what James Thornnehill had said.

You are going to suffer first.

She had suffered her entire life.

What was three more days? What was dying slowly in a dark hole compared to 63 years of slavery? Maybe this was mercy.

Maybe death would finally free her.

But then she thought about Thomas, about the wolf, about the way it had looked at her with those golden eyes.

He had not moved on.

He had not found peace.

He was still here, still tied to this place, still protecting her.

If she died, what would happen to him? Would he finally be free? Or would he be trapped here forever? She had to survive.

Not for herself, for him.

Elma dragged herself across the floor.

Her hands searched the darkness.

She found a wall, stone, damp.

She felt along it, looking for anything.

a crack where water might seep through.

A hole where air came in.

Nothing.

She kept searching.

Her fingers touched something soft.

She pulled back.

A rat.

It squeaked and ran away.

She continued along the wall.

Then her hand touched something different.

Wood.

A shelf maybe.

She felt upward.

There were objects on it.

She grabbed one.

A jar empty.

Another jar, also empty.

Then she found something else.

A small tin cup.

She shook it.

Liquid sloshed inside.

Water.

Old water.

Probably stagnant.

Probably full of things that could make her sick.

She did not care.

She brought it to her lips.

She drank.

It tasted like rust and dirt.

She drank it all.

It was not much.

Maybe 4 oz, but it was something.

She set the cup down.

She felt a little stronger.

Not much, but a little.

She lay back down on the floor.

She closed her eyes.

Sleep came in fragments.

She dreamed of the plantation burning.

She dreamed of James Thornnehill screaming.

She dreamed of the wolf standing over his body.

A sound woke her.

Footsteps above.

Voices muffled through the floor.

She has been down there two days now.

It was Ruth’s voice.

Master’s orders.

That was Porter.

She is going to die.

Maybe that is the point.

It is murder.

Watch your mouth.

You want to end up down there with her? Silence.

Then the footsteps moved away.

2 days.

She had been down here 2 days.

One more to go.

If James Thornnehill kept his word, if he did not just leave her here to rot.

The pain in her body had evolved.

It was no longer sharp.

It was dull, constant, numbing.

She was shutting down.

Her body was giving up.

But her mind held on.

She thought about Thomas.

She replayed every memory she had of him.

his first steps, his first words, the way he laughed, the way he used to sneak books into the slave quarters and read by candle light.

He had been smart, too smart.

That was dangerous for an enslaved person.

Smart slaves asked questions.

They saw the contradictions.

They wanted freedom.

James Thornhill’s father had noticed.

He had called Thomas uppety.

He had said Thomas needed to be broken, needed to learn his place.

Elma had begged Thomas to be careful, to keep his head down, to pretend he was simple, but Thomas had refused.

He said he would rather die free than live as a slave.

He got his wish.

He died, but he never got freedom.

Or maybe he did.

Maybe the wolf was his freedom.

A form without chains, a power that could not be controlled.

Another sound, different this time.

Not footsteps, a scratching like claws on wood.

Alma sat up.

Pain screamed through her body, but she ignored it.

The scratching continued.

It was coming from above, from the cellar door.

Then a howl.

Close right above her.

The wolf.

Thomas, she whispered.

The scratching became more frantic.

The wolf was trying to get in, trying to reach her.

But the door was thick.

The lock was solid.

Even a creature as powerful as the wolf could not break through.

Then voices shouting.

It is here.

The wolf is here.

Get your rifles.

Where did it go? It was just at the barn.

Gunshots.

Three.

Four.

Five.

The sounds echoed across the plantation.

Then silence.

Elma waited.

Her heart pounded.

Had they killed it? Had they killed Thomas? Minutes passed.

Long, agonizing minutes.

Then she heard something else.

A scream.

Human male cut short.

More shouting.

More gunshots.

Chaos above.

Something heavy hit the ground.

Then another scream.

Wet.

Gurgling.

The wolf was not dead.

The wolf was attacking.

Alma pressed her ear to the floor.

She could hear running, yelling, panic.

Then James Thornhill’s voice.

Loud, clear.

Get inside the house now.

Everyone inside.

Doors slamming, more gunshots, then quiet.

Alma waited.

She did not know what was happening.

She only knew the wolf was up there and it was killing.

Hours passed, or maybe just 1 hour.

Time was impossible to track.

Finally, the cellar door opened.

Light poured in.

Elma covered her eyes.

It hurt.

She had been in darkness so long that even lamplight was blinding.

Get up.

James Thornnehill stood at the top of the stairs.

His face was pale.

His hands shook.

Alma tried to stand.

Her legs would not work.

She collapsed.

I said, “Get up.

I cannot master.

” He came down the stairs.

He grabbed her by the hair.

He dragged her up the steps.

She screamed.

Her body scraped against the wood.

He pulled her outside.

Night had fallen again.

Torches lit the plantation.

She could see enslaved people huddled near the slave quarters.

She could see overseers with rifles standing guard.

And she could see bodies.

Two of them torn apart.

Blood everywhere.

Your wolf did this, Thornhill said.

He threw her to the ground.

Two of my men dead because of that animal.

Elma looked at the bodies.

One was Silas, the overseer who had mocked her.

His throat was ripped out.

His eyes stared at nothing.

The other was a man she did not recognize.

Probably a hired gun.

His stomach was torn open.

His insides were outside.

“I did not do this,” Alma said weakly.

“You called it here.

You are connected to it somehow.

He pulled out a pistol.

He aimed it at her head.

I should kill you right now.

Then do it, she said.

Her voice was barely a whisper.

I am ready to die.

His finger tightened on the trigger.

Then he stopped.

No, I have a better idea.

He turned to Porter.

Tie her to the whipping post.

We are going to use her as bait.

Sir, that wolf wants her.

It came here for her.

So, we are going to give it what it wants, and when it comes, we will be ready.

Porter hesitated.

Master Thornhill, she can barely stand.

This seems Do it or you will be tied up next to her.

Porter moved forward.

He lifted Alma.

She weighed almost nothing now.

3 days without food or water had withered her.

He carried her to the center of the plantation yard.

The whipping post stood there, a thick wooden pole driven deep into the ground.

Dark stains covered it.

Blood from countless beatings over the years.

Porter tied her wrists to the post.

The rope bit into her skin.

He tied them high so her feet barely touched the ground.

All her weight hung from her damaged shoulder.

The pain was unbearable.

I am sorry, Porter whispered.

Elma said nothing.

She had no strength left to speak.

James Thornnehill positioned his men around the yard.

Six of them, all with rifles, all pointed toward the darkness beyond the torch light.

When that wolf comes, you shoot it.

Thornhill said.

You shoot it until it stops moving.

You understand? The men nodded.

They looked scared.

They had seen what the wolf could do.

Thornhill stood near the main house porch.

He held a rifle himself.

His eyes scanned the darkness.

Hours passed.

Alma hung from the post.

Her consciousness faded in and out.

The pain became background noise.

Everything became distant, unreal.

She thought about her mother, about her children who had died young, about Thomas.

She thought about the plantation, about the cotton fields, about the generations of people who had suffered here, worked here, died here.

This land was soaked in blood, in pain, in injustice.

Maybe that was why Thomas had come back.

Not just for her, for all of them, for everyone who had been broken on this land.

The moon rose higher, full, bright.

It cast silver light across the plantation.

Then she heard it, a howl, long, low, coming from the woods.

The men tensed, rifles came up, eyes searched the darkness.

“Stay ready,” Thornhill said.

Another howl closer.

Alma lifted her head.

She looked toward the sound.

“Thomas,” she breathed.

Movement in the shadows, something massive circling, staying just beyond the light.

“I see it.

one of the men said, his voice cracked with fear.

Hold your fire until it comes into the light, Thornhill ordered.

The wolf moved closer.

Alma could see its shape now, enormous, powerful.

It moved like liquid shadow.

It stopped at the edge of the torch light.

Its golden eyes fixed on Alma.

Then they shifted to James Thornnehill.

The look in those eyes was pure hate.

Now,” Thornhill screamed.

Six rifles fired.

The sound was deafening.

Smoke filled the air.

The wolf moved faster than anything that size should move.

It dodged left.

Three bullets missed.

Two hit its flank.

One grazed its head, but it did not stop.

It charged.

The men tried to reload.

They were too slow.

The wolf hit the first man like a freight train.

He flew backward.

His rifle clattered across the ground.

The wolf was on him instantly.

Teeth flashed, blood sprayed.

The other men fired wildly, panicked.

Their shots went everywhere.

The wolf moved between them.

A blur of black fur and rage.

Another man went down, then another.

Screams filled the night.

James Thornnehill ran for the main house.

He reached the porch.

The wolf cut him off.

They faced each other.

Man and beast.

The wolf’s lips pulled back.

Its teeth were stained red.

Thornhill raised his rifle.

His hands shook so badly he could barely aim.

The wolf lunged.

Thornhill fired.

The bullet hit the wolf in the chest.

The wolf stumbled, fell, lay still.

Thornhill laughed.

A high, hysterical laugh.

Got you.

I got you.

He walked toward the wolf, his rifle pointed at its head.

He would finish it.

make sure it was dead.

The wolf’s eyes opened.

It sprang up.

Thornhill had no time to react.

The wolf’s jaws closed around his throat.

It shook him like a ragd doll.

Bones snapped.

Blood poured.

Thornhill made a wet gurgling sound.

His rifle fell.

His body went limp.

The wolf dropped him.

He hit the ground and did not move.

Alma watched it all.

She felt no horror, no fear, just relief.

Justice had finally come.

The wolf turned toward her.

It limped.

The bullet wounds were serious.

It was bleeding, weakening.

It walked to the whipping post.

It stood in front of her.

Those golden eyes met hers.

“You came back,” she whispered.

“You came back for me.

” The wolf made a sound, something between a whimper and a growl.

I am sorry, she said.

Tears ran down her face.

I am sorry I could not save you.

I am sorry they killed you.

The wolf pressed its head against her legs.

She felt its warmth, its breath.

You can rest now, she said.

It is over.

He is dead.

You can rest.

The wolf looked up at her one last time.

Then it walked away slowly, painfully back toward the woods.

Elma watched it go.

Goodbye, my son.

Goodbye.

The wolf disappeared into the darkness.

She never saw it again.

The plantation was silent now.

Bodies lay everywhere.

Blood soaked into the dirt.

The torches flickered and died one by one.

Alma hung from the post.

Her vision blurred.

Her body was shutting down.

She had nothing left.

But she smiled because James Thornnehill was dead.

Because the plantation would fall because after 63 years, something had finally changed.

Footsteps approached.

Ruth came running.

Other enslaved people followed.

They had watched everything from the slave quarters.

“Cut her down,” Ruth said.

quickly.

Hands reached up.

The ropes were cut.

Alma fell.

Ruth caught her.

Lowered her gently to the ground.

“You are going to be okay,” Ruth said.

But they both knew it was a lie.

Alma was dying.

Her body had been pushed too far.

3 days without food or water, beaten, hung from a post.

She had minutes left, maybe less.

“The wolf,” Elma whispered.

“Did you see it?” Yes, we all saw it.

That was Thomas.

That was my son.

Ruth nodded.

She did not argue.

I know.

We all know.

Alma’s breathing became shallow.

What happens now? We are free.

Master Thornhill is dead.

His men are dead.

We can leave.

Where will you go? North? Anywhere? It does not matter.

We will be free.

Alma smiled.

Good.

That is good.

Her eyes closed.

Her breathing stopped.

Her body relaxed.

She was finally free, too.

Ruth held Elma’s body for a long time.

The other enslaved people gathered around.

17 souls who had lived in chains, who had watched their families torn apart, who had survived through cruelty and terror.

Now they stood in silence.

The only sounds were the wind and the crackling of dying torches.

“What do we do?” someone asked.

Ruth looked up.

Her face was wet with tears, but her eyes were hard, determined.

We bury our dead.

Then we burned this place to the ground.

They worked through the night.

They dug a grave for Alma behind the slave quarters, deep, respectful.

They wrapped her body in the best blanket they could find.

They laid her to rest as the sun began to rise.

Ruth said words over the grave.

She was not a preacher, but she knew the Bible.

The Lord is my shepherd.

I shall not want.

He makes me lie down in green pastures.

He leads me beside still waters.

He restores my soul.

The others repeated the words.

Some cried.

Some stood silent.

All of them knew what Alma had endured, what she had lost, what she had survived.

When they finished, they turned to face the plantation.

The main house with its white columns, the barn, the cotton fields, the whipping post still standing in the yard.

Burn it, Ruth said.

They scattered across the property.

They grabbed torches.

They lit fires in every building.

The slave quarters they left alone.

Those they would need for one more night.

But everything else burned.

The main house went up fast.

The wood was old and dry.

Flames climbed the walls.

Windows exploded.

The roof collapsed inward with a roar.

The barn burned next.

Then the storage sheds, the cotton gin, the overseer houses.

Fire consumed everything.

Smoke rose into the morning sky like a black pillar.

The enslaved people stood and watched.

Some smiled, some laughed, some just stared in disbelief.

James Thornhill’s body still lay in the yard.

No one touched it.

Let him burn with his plantation.

Let him turn to ash with everything he had built on suffering.

By noon the fires had died down.

Only charred ruins remained.

The Thornhill plantation was gone.

Erased.

Nothing left but memories and ghosts.

We should go, someone said, before more white men come.

Ruth nodded.

Gather what you can carry.

food, water, blankets.

We leave within the hour.

They moved quickly.

They had waited their whole lives for this moment.

They would not waste it.

But before they left, Ruth did one more thing.

She went to Alma’s grave.

She knelt beside it.

She placed her hand on the fresh dirt.

“Thank you,” she whispered.

“For holding on, for surviving, for giving us this chance.

” The wind picked up.

It moved through the dead cotton fields.

It carried the smell of smoke and ash.

And for just a moment, Ruth thought she heard something.

A howl, distant, fading, like a final goodbye.

She stood.

She wiped her eyes.

She walked back to the others.

They left the plantation together, all 17 of them.

They walked down the dirt road that led away from the property.

the road they had never been allowed to take.

The road to freedom.

Some headed north, others went east.

They split into smaller groups.

It was safer that way, harder to track, harder to catch.

Ruth led a group of seven.

They walked for 3 days.

They slept in the woods.

They avoided towns.

They drank from streams.

They ate what little food they had brought.

On the fourth day, they reached a settlement.

A community of formerly enslaved people who had built their own town.

Small, poor, but free.

They were welcomed, given shelter, given food, given hope.

Ruth found work as a cook.

Others found work in fields they now owned themselves.

Children went to school for the first time.

People learned to read, to write, to dream.

Years passed.

The story of the Thornhill plantation spread.

People heard about the wolf, about the old woman who had been tied to the whipping post, about the fire that consumed everything.

Some said it was justice, others said it was murder.

Some said it was both.

Ruth grew old in that settlement.

She married.

She had children.

She lived to see them grow up free.

Something her mother never saw.

something Alma never saw.

But she never forgot.

She told the story to her children and they told it to their children.

The story of Alma, the story of Thomas, the story of the wolf.

And sometimes on quiet nights when the moon was full, people in that settlement would hear howling in the distance, deep, mournful, protective.

They said it was Thomas still watching, still guarding, making sure no one ever forgot what happened, making sure no one ever forgot the price of freedom.

20 years after the fire, a journalist came to the settlement.

He was writing a book about slavery, about reconstruction, about the violence that continued even after emancipation.

He interviewed Ruth.

She was 60 years old now.

gray hair, deep lines in her face, but her mind was sharp.

Her memory was clear.

“Tell me about the Thornhill Plantation,” he said.

Ruth sat in her small house.

A fire burned in the hearth.

She looked into the flames as she spoke.

“It was hell,” she said simply.

“A place where people were worked to death, where children were sold away from their mothers, where asking for kindness meant a beating.

and the fire, the deaths.

James Thornnehill was a monster.

He kept us in chains long after the law said we should be free.

He beat us, starved us, killed us.

What happened to him was what he deserved.

Some people say a wolf killed him.

That it killed several men that night.

Ruth smiled.

Some people say a lot of things, but you were there.

You saw it.

What really happened? Ruth was quiet for a long time.

Then she spoke.

There was an old woman named Alma.

She had a son named Thomas.

Thomas was smart, too smart.

The Thorn Hills did not like that, so they killed him.

Made it look like he ran away.

But Alma knew.

Mothers always know.

And And Thomas came back not as a man, as something else, something wild, something free.

He came back to protect his mother to punish the people who killed him.

You are saying the wolf was Thomas.

That is what you believe.

I am saying that justice comes in many forms.

Sometimes it comes from courts and laws.

Sometimes it comes from the earth itself, from the spirits of those who were wronged.

The journalist wrote everything down, but he did not include this part in his book.

He thought people would think he was crazy, that Ruth was crazy.

But he kept the notes.

And years later, after he died, his grandson found them.

The grandson was a writer, too.

He decided to investigate.

He went to Montgomery.

He searched through old records.

He found mentions of the Thornhill Plantation.

He found newspaper articles about the fire, about the mysterious deaths.

He found something else, too.

Reports from hunters, from travelers, from people who lived near where the plantation had been.

Reports of a wolf, a massive black wolf with golden eyes.

Seen over decades.

Seen protecting formerly enslaved people from violence.

Seen attacking men who wore white hoods.

Seen near lynching trees where it would howl all night until someone came to cut down the bodies.

The wolf had been seen for over 50 years after Thomas died, long past the natural lifespan of any wolf.

The grandson wrote his own book.

He called it the spirit wolf of Alabama.

It told the story of Alma and Thomas, of the plantation, of the fire, of the justice that came not from men, but from something beyond understanding.

Some people called it fiction.

Others called it folklore.

But formerly enslaved people and their descendants knew better.

They knew it was truth because they had their own stories.

Stories passed down through generations.

Stories of protection, of vengeance, of spirits that refused to rest until the wrongs were made right.

The ruins of the Thornhill plantation still exist, mostly buried now, overgrown with trees and brush.

But if you know where to look, you can find them.

The foundation of the main house, bits of the slave quarters, the whipping post, fallen and rotting, but still there.

And Alma’s grave still marked.

People visit it sometimes.

They leave flowers.

They leave stones.

They leave notes thanking her for her sacrifice, for her strength, for holding on when holding on seemed impossible.

Local historians say the land is cursed.

That nothing grows there properly.

That animals avoid it.

That people who try to build on it always fail.

Accidents happen.

Structures collapse.

Workers quit.

Some say it is the soil poisoned by ash and blood.

Others say it is something else, something that refuses to let the land be used for profit ever again.

And sometimes, even now, people hear howling, rangers working in the area, hikers passing through, hunters who wander too close.

They hear it and they feel something, a presence, a warning, a promise.

The wolf is still there.

Thomas is still there watching, waiting, making sure that what happened on that plantation is never forgotten.

Making sure that justice once claimed is never taken back.

The moral of the story is not simple.

It cannot be.

History is not simple.

Suffering is not simple.

Justice is not simple.

But if there is a lesson, it is this.

Oppression creates spirits that cannot be killed.

Cruelty creates forces that cannot be controlled.

Violence creates justice that comes in forms the violent never expect.

James Thornnehill believed he was untouchable.

He believed his wealth and his skin color and his position gave him the right to treat people as property, to beat them, to starve them, to kill them.

He was wrong.

And his wrongness killed him.

Elma believed her suffering was meaningless, that her son died for nothing, that nothing would ever change.

She was wrong, too.

Her suffering had meaning because she survived it, because she bore witness to it.

Because her survival became the foundation for others to build freedom upon.

And Thomas, Thomas believed that death was the end, that once he was killed, his story was over.

He was the most wrong of all because death was not the end.

It was a transformation, a change, a becoming.

He became something that could not be chained, could not be bought, could not be controlled.

He became the justice his people could not get from laws or courts or governments.

He became what was needed and he remained until his purpose was fulfilled.

Ruth died in 1912.

She was 83 years old.

She died surrounded by children and grandchildren and great grandchildren, free people, educated people, people who owned land and businesses and futures.

At her funeral, her oldest grandson spoke.

He told the story of the Thornhill plantation.

He told the story of Alma and Thomas and the wolf.

He told it so the youngest generation would know, would remember, would understand the cost of the freedom they enjoyed.

When he finished, everyone was silent.

Then from somewhere in the distance, a howl rose into the air.

Long, mournful, final.

People looked at each other.

Some smiled.

Some nodded.

They knew what it meant.

Thomas had heard.

Thomas knew.

And Thomas approved.

The howl faded.

The funeral continued.

People sang hymns.

They prayed.

They celebrated a life well-lived.

And somewhere in the woods of Alabama, a massive black wolf with golden eyes lay down beneath an old oak tree.

Its body was scarred, tired, ancient beyond measure.

It had done what it came to do.

It had protected its mother.

It had punished her killers.

It had watched over the people who escaped.

It had become a legend that would outlive them all.

Now it could rest.

Finally, truly completely, the wolf closed its eyes, its breathing slowed, its body relaxed, and as the sun set over the Alabama landscape, the wolf’s spirit finally let go.

It rose up like smoke, like mist.

It drifted on the wind.

It went to wherever spirits go when their work is done.

Thomas was free.

Alma was free.

All the souls who had suffered on that plantation were free.

The land remembered, the stories remembered, the descendants remembered, and that memory became a weapon, a shield, a warning to anyone who thought that cruelty could last forever, that injustice could go unpunished, that the oppressed would remain silent.

Because they would not.

They could not.

They were witnessed by the earth, by the trees, by the spirits of those who came before.

And those spirits were watching, always watching, ready to rise again if needed, ready to howl in the darkness, ready to show their teeth, ready to remind the world that some debts must be paid, some wrongs must be writed, some justice cannot be denied.

No matter how long it takes, no matter what form it takes, no matter who tries to stop it, justice comes in the end always.

And when it does, it has teeth.

News

Ilhan Omar ‘PLANS TO FLEE’…. as FBI Questions $30 MILLION NET WORTH

So, while Bavino is cracking down in Minnesota, House Republicans turning the heat up on Ilhan Omar. They want to…

FBI & ICE Raid Walz & Mayor’s Properties In Minnesota LINKED To Somali Fentanyl Network

IC and the FBI move on Minnesota, touching the offices of Governor Tim Walls and the state’s biggest mayors as…

FBI RAIDS Massive LA Taxi Empire – You Won’t Believe What They Found Inside!

On a Tuesday morning, the dispatch radios in hundreds of Los Angeles taxi cabs suddenly stopped playing route assignments. Instead,…

Brandon Frugal Finally Revealed What Forced Production to Halt in Season 7 of Skinwalker Ranch….

The Secret of Skinwalker Ranch became History Channel’s biggest hit. Six successful seasons documenting the unknown with real science and…

1 MINUTE AGO: What FBI Found In Hulk Hogan’s Mansion Will Leave You Shocked….

The FBI didn’t plan to walk into a media firestorm, but the moment agents stepped into Hulk Hogan’s Clearwater mansion,…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage… It started like any other evening…

End of content

No more pages to load