By the time word reached the last cabin at the edge of the cane fields, the damage was already done.

People said the master had stood under the big live oak with a Bible in one hand and a man’s life in the other, weighing which would make the better payment on his debts.

They said his wife had stood beside him with her hair coming loose and her shame pinned in place like a brooch.

They said the enslaved man she’d been caught with didn’t beg, even when every white eye in the county burned holes through his skin.

But the story did not start under the oak.

It began on one of those evenings when the air over coastal Georgia felt like damp wool draped over the world, and the lamps in the big house burned longer than they needed to, because nobody inside wanted to admit how dark it had gotten.

Ashefield Crossing sat on a rise above the marsh, three stories of peeling white wide porches, and old money that had learned to hide its cracks.

The fields around it rolled out in dull green waves toward the river.

The slave cabins crouched in their shadow like someone had dropped a handful of rough wooden teeth at the edge of the property and forgotten them.

Nathaniel Crowell, master of Ashefield Crossing, had written into town that afternoon in a foul mood, muttering about cotton prices, freight costs, and how the banker at Marshand and Sons had started speaking to him in the tone men used when they smelled blood.

His wife, Marion, stayed behind with what she called a headache, and what the house girls silently called loneliness.

Her marriage had grown colder than the marble family plot at the far end of the property.

Three echoing floors, 12 rooms, and not a single space where she did not feel watched, judged, or ignored.

When Nathaniel’s boots were gone from the halls, the whole house exhaled.

Doors stayed open a crack instead of shut tight.

Voices softened, but rose a little.

The enslaved women in the kitchen moved with less stiffness, like their backs forgot for a moment how heavy a white man’s presence could be.

Marian crossed her bedroom and tugged at the tall window.

The wood groaned, then stuck, refusing to budge more than an inch.

The air in the room sat hot and stale on her skin.

She hesitated only a second before going to the bell by the door.

Her fingers hovered over the cord, then dropped.

Instead, she stepped into the hall and caught sight of a house girl passing with a stack of folded linens.

“Essie,” Marian said.

The girl stopped so quickly, one of the towels slipped.

“Yes, Mom.

Find Jonas Reed,” she said, steadying her voice.

“Tell him the window in my room is stuck.

I want it fixed before the night closes in.

Essie’s eyes flicked toward the empty stretch of hall as if to make sure Nathaniel truly was gone.

Then she nodded and darted away without a word.

Jonas was in the carriage shed, sleeves rolled, arms deep in a wheel he had half taken apart to keep it from collapsing on the next trip to town.

He was not the biggest man in the quarters or the loudest.

He survived by paying attention.

He noticed which boards sagged before they broke, which hinges squeaked before they snapped, which mules favored a leg days before they dropped.

He listened when men muttered about new overseers, when the driver came back from town with rumors about the bank and the sheriff and which plantations might not see another Christmas under the same name.

He had learned early that when you could fix things, doors, carts, pumps, fences, you became harder to sell.

A man who could keep a place from falling apart was worth more on paper than a man who could only swing a hoe.

Essie relayed the order.

Miss Marion wants you in her room.

Says the windows stuck.

She didn’t say the rest, but it was there in the tightness of her mouth.

Be careful.

Jonas wiped his hands, rinsed them at the pump, and started up toward the house, cap in one hand, eyes lowered just enough to look safe, not enough to look weak.

He climbed the back staircase that servants used, counting each step out of habit.

Halfway up, one of the boards creaked longer than the others.

He made a note to fix it later.

Things that groaned at the wrong time had a way of bringing trouble.

At her door, he paused.

“You sent for me, ma’am?” he asked from the threshold, body angled so he was visible but not inside until she said so.

“You never crossed that line on your own.

” “Come in, Jonas,” Marian said.

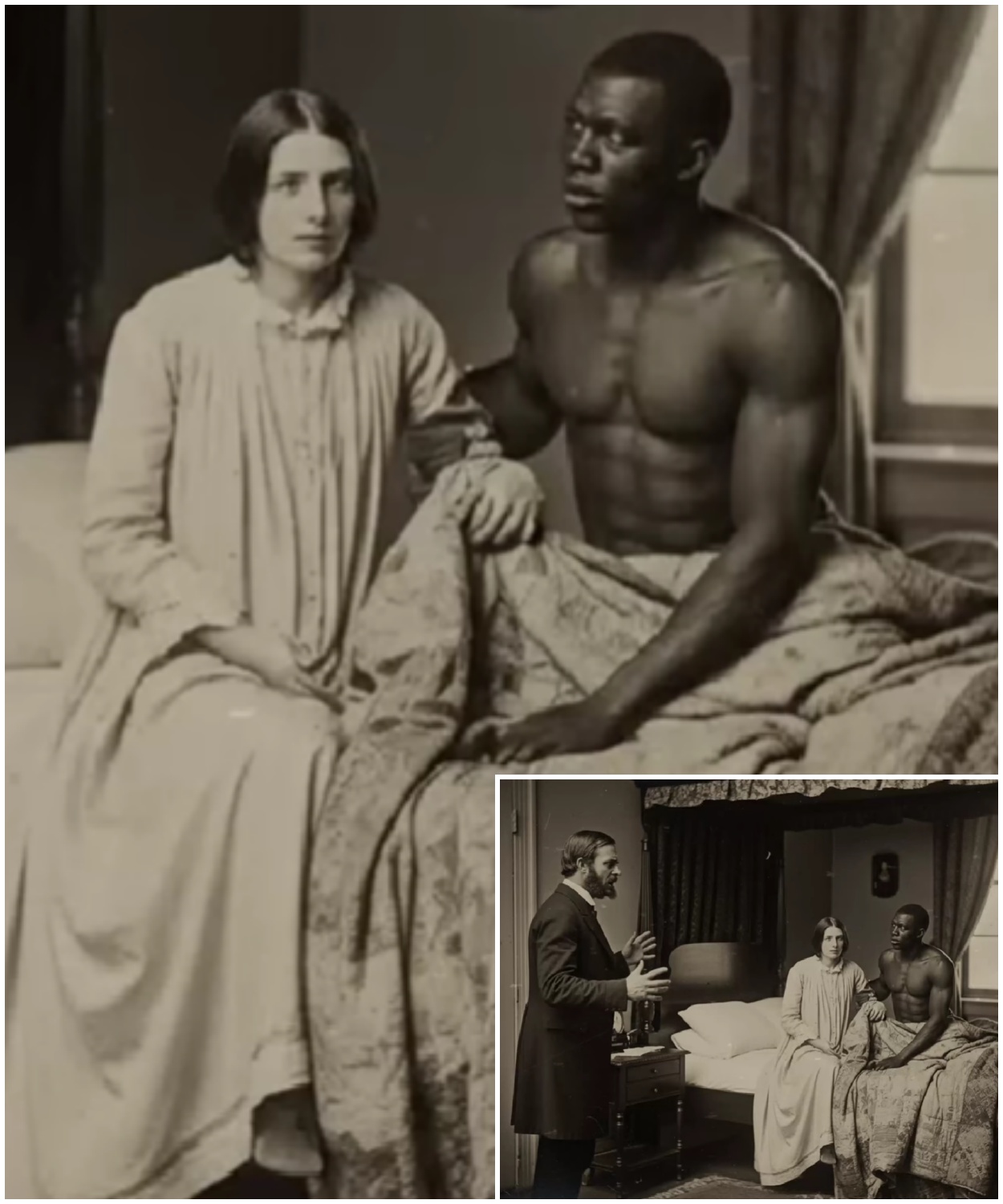

She sat on the edge of the four poster bed in a thin cotton night dress that clung to her.

In the heat, a shawl wrapped around her shoulders as if she could hide inside its fringe.

The lamp on the side table cast soft gold over her face, picking out the tired lines near her mouth and the faint shadows under her eyes.

light caught on the gold band at her finger and on the fine bones of her wrist.

She pointed toward the tall window that looked out over the darkening trees.

“It won’t open right,” she said.

“I don’t like feeling shut in.

” “Yes, ma’am.

” He crossed the floor in three measured steps, close enough to see the problem, far enough that no one could say he’d come too near the bed.

The frame had swollen where rain had seeped in over the years.

The sash sat crooked.

It needed patience, not strength.

He ran his fingertips along the wood, feeling for the places that stuck.

He worked the latch loose, pried gently, then pulled the small knife he kept folded in his pocket.

A few thin curls of wood dropped to the floor as he shaved the swollen edge.

When he eased the window up again, the sash slid smoother.

A thin breath of night air slipped into the room, cooler, carrying the scent of wet earth and distant salt marsh.

There, ma’am, he said should move easier now.

“Thank you,” she replied.

The gratitude came out softer than she had intended, too full of relief for something that small.

It wasn’t just about the wood.

It was about a pair of hands in the room that weren’t holding a ledger, a bottle, or judgment over her head.

You’re very good with your hands.

The words were simple, polite, the kind of thing you might say to any craftsman, but they dropped into the space between them with a different weight.

Jonas went very still.

Every story told in the quarters about white women and black men started with something that sounded harmless, a compliment, a favor, a touch that could be spun later into whatever shape suited the master’s anger best.

He forced himself to nod like it was nothing.

Just trying to be useful, Mom.

My husband says that about you, she murmured, gaze drifting not to him, but to the open window.

Useful.

He says it about the mules, the fields, the ledgers, me.

Jonas didn’t answer.

There was no safe reply to that.

She seemed to hear the danger in her own confession and pulled the shaw tighter.

“You can go,” she said quickly.

“Thank you.

” He left, but the image stayed with him as he moved back down the stairs.

The mistress of Ashefield Crossing, sitting on a bed too wide for one, wrapped in cloth she didn’t need, asking a man she owned to make sure she didn’t feel trapped.

After that night, the house began to find more things that needed Jonas.

A banister that suddenly worried her.

A door that didn’t latch smoothly anymore.

A lamp that smoked too much and left soot on the ceiling.

A drawer that stuck just enough to make her tug twice.

Each errand drew him back into the big house when Nathaniel was away arguing about cotton and credit in town.

Each visit stretched a little longer as she asked him to explain what he was doing, to wait a moment so she could check if it held, to stand just a little closer so she could pretend for a few stolen minutes.

That someone in that grand empty house came when she called simply because she had asked.

He answered carefully, “Always, ma’am.

” always three steps back when the work was done.

He watched her out of the corner of his eye the same way he watched cracked beams and frayed ropes, assessing what might break and how far it would fall.

In the quarters, people noticed Ashefield’s lady calling for Jonas again.

Old Aunt Bess muttered over the stew potart one evening.

Windows and lamps and this and that.

Windows ain’t the only thing she wants open.

“Hush now, Laya.

” Jonas’s older sister warned, glancing at the door.

“You say that too loud.

It’ll be his neck and her tears and the master’s belt in between.

” Bess snorted, but she lowered her voice.

Necks snapped quicker than windows.

“He better remember that.

” Jonas remembered.

He remembered the boy from the next plantation over, accused of looking too long at the wrong face.

He remembered the woman taken from the quarters and brought back with bruises she had to pretend not to feel.

He remembered his mother’s whisper in Virginia before they sold him down river.

Some storms you hide from, some you survive by becoming the wall.

The night everything slipped began with a different kind of storm.

All afternoon thunderheads piled up over the marsh, fat and dark as bruises.

The air grew so thick even the cicas seemed to drag their song.

Wind clawed at the live oaks, making the long gray moss thrash like something trying to shake free.

By the time the first lightning split the sky, the dogs were already whining and scratching at the kitchen door.

Aunt Bess crossed herself twice and threw salt into the fire just in case.

Children were called inside.

Lanterns were lit early.

Nathaniel had ridden into town that morning, promising to be back after sundown, if the fooled banker don’t talk me to death first.

He sent no word about when he might return.

Everyone assumed that meant late or not at all.

Marian paced her bedroom, bare feet, soundless on the rug.

Every flash of lightning carved her reflection into the window glass like a ghost trapped on the inside looking out.

Thunder rolled over the roof like furniture dragged by giants.

She had always hated storms.

As a girl, they’d sent her running to her mother’s bed.

As a wife, they left her staring at the empty half of the mattress and the widening fault lines in the house.

Another crack of thunder rattled the pains.

Without thinking, she stepped into the hall, fear pushing past dignity.

“Jonas,” she called.

Her voice was sharper than she meant, carrying down the corridor and bleeding into the rumble of the storm.

On the far side of the upstairs floor, Jonah stood in the linen closet, wedged under the eaves, checking a slow leak that darkened the ceiling.

He heard his name, heard the edge in it, and came quickly.

You did not move slowly when the mistress called, especially not at night, especially not when thunder made everyone jumpier than usual.

He paused at the threshold of her room as always.

You need something, Mom? Marian stood near the foot of the bed.

One hand rested flat on the carved post, the other pressed against her ribs like she was holding herself in place.

The storm, she said, and the word sounded foolish the moment it left her mouth.

The window rattles.

I don’t like being in here alone when it’s like this.

He glanced at the window.

It was holding.

The wood he’d shaved weeks before had done its work.

The glass trembled with each thunderclap, but stayed intact.

The danger in the room wasn’t in the frame.

It was in the space between the woman and the man she had called for.

“I can sit by the door,” he said carefully.

“Keep an ear on it.

If anything comes loose, I’ll fix it.

It was the safest place he could choose, close enough to obey, far enough that nobody could honestly say he crossed the line on his own.

” She nodded, jaw tight.

He dragged a chair from the corner and set it by the door.

He sat with his hands on his knees, eyes on the floorboards, listening to rain fogged the roof, and distant thunder roll over the marsh.

Another flash turned the room white.

The thunder that followed shook the bed posts.

Marian flinched.

After a moment, she spoke again, voice thinned by the noise.

Were you afraid of storms as a child? She asked.

Yes, mom, he said.

Back before they sold me south.

My mama used to count between the lightning and the thunder.

Said it was just the sky arguing over who forgot to turn the rain off.

The longer the count, the farther the fuss.

What do you do with the fear now? She asked.

He weighed answers.

There was the safe one he could give.

Then there was the true one.

“Bury it,” he said finally.

“Ain’t much room left for fear with everything else I got to carry.

” She let out a short, brittle sound that might once have been a laugh.

“We have that in common, then,” she said.

“No room left for fear when you’re busy carrying what other people put on your back.

” Lightning flashed again, closer.

The thunder came almost at the same moment.

A bone deep crack that made the house shudder.

This time, when she jumped, her hand shot out on instinct, reaching toward the nearest solid thing.

Her fingers closed around his wrist.

It lasted less than a second, her skin on his, clutching hard.

But it was long enough to match every nightmare story he’d ever heard, whispered over low fires about white women’s hands and black men’s doom.

Jonas went rigid.

So did she.

Realizing what she’d done, Marion snatched her hand back as if his skin had burned her.

“Forgive me,” she whispered.

“I didn’t mean.

” “It’s all right,” he cut in quickly.

“It’s just a storm.

” That’s not what I’m afraid of, she said so quietly he almost missed it.

He should have asked to leave.

He should have begged her to send one of the house girls instead to let him wait in the hall.

Every instinct honed by survival screamed that sitting in this room with her and this kind of silence would end badly.

But another fear gnored just as sharp beneath the first.

The fear of saying no to someone who could have him whipped, chained, or sold with a word.

White people called some things requests when everyone knew they were orders dressed nice.

So he stayed.

The lamp burned lower.

Rain hammered the roof.

Their words thinned and then stopped.

The storm’s noise pressed against the walls until exhaustion became heavier than fear.

I can’t sleep, Marian murmured after a long stretch of silence.

Not sitting rigid in that chair like a prisoner waiting for sentence.

Lie down on top of the covers just until the worst passes.

He hesitated.

Ma’am, that ain’t on the far edge, she said quickly.

You’ll be closer to the window.

If the glass cracks, you’ll reach it faster than from the door.

It was a flimsy excuse, and they both knew it.

But flimsy excuses were sometimes the only bridges people were willing to admit they’d crossed.

He rose slowly, every nerve buzzing.

He lay down stiff as a plank on the far edge of the mattress on top of the coverlet, boots still on, hands folded on his chest like a man laid out for viewing.

The distance between their bodies could have held a third person.

It wasn’t enough to feel safe.

At some point, another crack of thunder made her flinch, and her fingers fumbled blindly across the sheet until they found his forearm.

They settled there, light but real.

At some point after that, his muscles loosened just enough for his eyes to close.

The thunder rolled them both toward sleep deeper than they meant to allow.

Outside, the storm raged.

Inside, the house finally fell silent.

Neither of them heard the front door open downstairs.

Nathaniel Crowell stepped into his own hallway, soaked through and furious.

The trip to town had not gone as planned.

The banker, Hail Martian, had looked at him over wire rimmed spectacles, and spoken of exposure and restructuring, with the smooth indifference of a man who knew exactly how far he could press before something cracked.

“We’ll need more than promises next month, Mr.

Crowl Marshon had said property names numbers I can show my own father when he asks why we keep extending credit to a man whose fields don’t yield what they used to.

Nathaniel had swallowed his pride and handed over a list of assets he was willing to liquidate.

Hogs, horses, two older men from the quarters he swore he could spare.

Marshon had tapped his finger near the bottom of the page where Jonas’s name sat, then moved on without comment.

Now thunder still grumbled far off, but the worst of the storm had passed.

The lamps in the parlor flickered low.

The house seemed to be holding its breath.

He took the stairs two at a time, boots beating an angry rhythm.

He didn’t bother to soften his step.

This was his house.

Let them hear him coming.

At his bedroom door, he paused only long enough to rehearse the words he’d planned to spit at Marion about expenses and respect, and how he’d had to listen to his debts recited out loud, like somebody reading a list of sins in a church where he wasn’t allowed to stand.

He pushed the door open.

The lamp beside the bed, still burned, turned too low.

The bed itself, the bed he’d paid for with Marian’s dowy and his own pride, was not empty.

His wife lay on her side, hair unpinned, cheeks flushed with sleep, wrapped in his sheets.

On the far edge of the mattress, fully clothed, boots and all, lay a black man, Jonas, arm above the blanket, Marion’s pale hand resting on it like it belonged there.

For one stretched out second, Nathaniel did not breathe.

Then the sound tore itself out of him in a roar that rattled the glass in the window and brought everyone else in the house running.

Marianne.

His shout hit the room like another bolt of lightning.

Marian jerked awake, clutching the sheet to her chest, confusion flipping into horror in an instant.

Jonas rolled off the bed faster than he knew he could move, landing hard on his knees with his hands flat on the floorboards.

For a heartbeat, everything froze.

The husband saw his wife’s bare shoulders and an enslaved man’s dark arm where his own should have been.

The wife saw the man she’d married standing in the doorway with his face twisted into something worse than rage.

a raw wounded satisfaction like a man who’d finally found proof of a betrayal he’d suspected for years.

Jonas saw at the end of his life wearing a sweat- soaked shirt and a furious white face.

“What in God’s name is this?” Nathaniel roared, stepping into the room.

“Nathaniel,” Marion began, voice shaking.

“Please, it’s not.

Don’t you please me?” he snapped, pointing a trembling finger at Jonas.

“You away from that bed.

” Jonas was already off it, kneeling so hard his knees bruised on impact.

“Sir,” he said, throat dry.

“I never forced.

” “You don’t speak,” Nathaniel hissed.

“Not in my room, not standing where I sleep.

” He turned on Marion, eyes bright with a hurt.

He would never let himself name.

“You going to tell me?” “This isn’t what it looks like,” he demanded.

“Because it looks like my wife has been keeping my side of the bed warm with a man I own.

” The word own hit the air like a nail slammed into hardwood.

Marian’s throat closed.

There was no neat story for this, no explanation that could untangle the knot of fear and need and power that had led her to reach for another hand in the dark.

It didn’t start like that, she whispered.

I was afraid.

You were gone.

The storm.

I was gone.

Making sure you still have a roof to be afraid under.

He snapped.

Gone.

while Marshon counted my debts out loud like he was reading a ledger in a public square.

“And while I’m doing that, you’re in here writing your own account with my property.

” He spun back to Jonas.

The blow came without warning.

A backhand across Jonas’s face so hard it snapped his head to the side.

Pain exploded across his jaw.

The copper taste of blood bloomed at his tongue.

You think because I’m not here, you can climb into whatever you like? Nathaniel snarled.

Is that it? You think my house is yours to pick through once my back is turned? Jonas’s ears rang.

Behind the pain, past the fear, something else glimmered in Nathaniel’s eyes.

Something Jonas recognized because he’d seen it in men staring down crop light and banknotes.

fear not of him, of the gossip, of what men like Hail Marshand would say if they ever found out the master of Ashefield Crossing couldn’t keep his own bed in order.

“Sir,” Jonas said, struggling to keep his voice level.

“I did what I’ve always done.

She called.

I came.

She said, stay.

I stayed.

Ain’t had a day on this place yet where my no counted for much.

The words landed harder than any fist.

Nathaniel’s hand twitched toward his belt.

It would be so easy.

Three steps, the leather, the buckle, a beating that would blot out this sight in sweat and blood or rope.

There were plenty of trees on this land that had never held fruit.

But another instinct shouldered its way through the fury, a colder one.

He pictured Marshon’s thin mouth tightening when he mentioned distressed properties.

He heard the neighbors low, eager draw.

Heard you’ve been slipping at Ashefield Crawl.

Let me know if you get tired of carrying all that land alone.

He saw for a flash his own reflection if this got out.

A man who’d lost control of his wife and his property.

Killing Jonas on the spot would feel righteous for a wild minute.

It would also raise questions.

Questions were poison when your name was written in red ink in the bank’s ledger.

Nathaniel dropped his hand.

“Get up,” he said tightly.

“Cover yourself, Marion.

I won’t have the house girl seeing you naked on top of your shame.

” She fumbled for a dressing gown, fingers clumsy.

Jonas rose slowly, head bowed, hands loose at his sides, in the posture of a man who knew any sudden move might end with a bullet in his back.

Nathaniel studied them both, chest heaving.

“You haven’t just offended me,” he said, voice sharpening.

“You’ve offended order.

You’ve given every mouth on this place something rotten to chew on, white and black.

He looked almost thoughtful now, a man who’d just seen a different way to use a bad hand.

If this stays a secret, I look like a fool who can’t keep his own house in line, he continued.

I won’t have that.

If this is going to be a story, it will be my story.

Marian felt the air go cold.

“What are you going to do?” she asked.

“What I should have done the day I started taking on more debt than I liked,” he said.

“Turn a weakness into a show of strength.

” He stared at Jonas with a strange, calculating calm.

“We’re going to have ourselves a trial.

” The word dropped into the room like a stone into a well.

Jonas’s stomach flipped.

There were courtrooms in town where white men argued over fences and contracts.

When it came to slaves, trials usually meant short speeches and long ropes.

Tomorrow, Nathaniel said, under the big oak, I’ll call in our neighbors.

The men whose respect matters.

Every black soul on this place will stand and watch.

They’ll hear how my wife let a slave into my bed.

They’ll hear what happens when lines get crossed at Ashefield Crossing.

The judgment will be public.

So will the punishment.

Nathaniel, please, Marion said, stepping toward him.

Don’t do this.

Handle it between us.

Don’t drag the whole county into our bedroom.

You dragged the whole county into it when you took a man from the quarters into my sheets.

He shot back.

You didn’t just break your vows.

You made a mockery of me in the one place I can’t afford it.

He jerked his chin toward Jonas.

You’ll spend the night locked in the smokehouse, he said.

I want you alive and standing when I ask my questions tomorrow.

I want every word you say to remind them what happens when a man forgets his place.

Jonas knew better than to argue.

Two field hands appeared in the doorway, faces tight, summoned by the shouting.

They took him by the arms, not cruy, but firmly, like men who had seen this scene play out before, and knew there was no stopping it.

As they led him away, Marion blurted.

“I’m sorry.

” Nathaniel turned on her like she’d slapped him.

“Save your apologies for your maker,” he said.

“You’ll be seeing more of him than of polite company once this is done.

” The door closed behind Jonas, muting the sounds of the house.

The storm outside moved off toward the horizon.

Inside a different kind of storm dug in.

The smokehouse was dark and smelled of salt, old meat, and wood smoke soaked deep into the walls.

They shoved Jonas inside and dropped the bar across the door with a heavy thud.

He stood for a while, shoulders pressed to the rough planks, heart pounding.

He had always known a night like this could come.

Every boy in the quarters grew up on stories about white women who reached out in the dark and white men who answered at dawn with blood.

Most of those tales ended with a hurried burial and a silence everyone pretended not to hear.

This talk of a trial felt worse.

A beating was pain.

A hanging was final.

A trial was spectacle.

pain dressed up as righteousness performed in front of every set of eyes that mattered.

Those that owned him and those who knew all too well what it meant to have no choice.

Jonas sank down with his back against the wall and his hands resting on his knees.

In the darkness, he could see his mother’s face the day they led him away in chains years ago on a different plantation under a different tree.

“Remember this,” she had whispered.

“They can sell your body, not your understanding.

They can name you what they like on paper.

That ain’t your true name.

” In the big house, Marian sat on the same bed where everything had cracked open.

The sheets were neat and cold now.

Her hands shook in her lap.

She thought of the choices she’d had that Jonas never did.

The way she could have walked into a room and walked back out again without anyone raising a whip.

the way she had used her power not to free anyone, but to drag him into the center of her hunger.

She had told herself she would pay for the comfort she stole.

She had never imagined Nathaniel would hand the bill to someone else.

Dawn came gray and creeping, dragging murmurss behind it.

By midm morning, word had run through the quarters like fire in dry grass.

The master caught Miss Marion in bed with Jonas.

The master is setting a trial under the big oak.

Everybody is to be there.

Some cursed under their breath as they worked.

Some said nothing at all.

Silence was its own language, thick with things nobody dared speak where white ears might catch them.

In the yard, Nathaniel Crowell set his scene.

He dragged a wooden crate under the thickest branch of the great live oak that some folks had started calling gallows tree even before any rope ever went over it.

He placed a small table beside it with a heavy Bible and a silver topped cane laid across the leather cover like a claim.

Then he sent riders down the road to neighboring plantations.

Come witness how a man keeps order in his house.

They came.

Of course, men like that did not turn down a chance to watch someone else’s shame from a safe distance.

On the surface, they would pretend to be scandalized.

Underneath they fed on stories like this the way the bankers fed on overdue notes.

By the time the sun sat high enough to press the heat down onto everyone’s shoulders, a ring of white planters stood near the front, boots planted wide, hats tipped back, faces carefully arranged into sober lines that never quite hid their curiosity.

Behind them, forced to stand where they could see and be seen, the enslaved people of Ashefield Crossing formed a wider, darker circle.

Field hands with shoulders carved by years of work.

House servants with careful eyes, children tucked against their mother’s skirts.

Laya stood near the front of the black circle, arms crossed, jaw clenched.

Her little boy clung to her skirt, thumb jammed in his mouth.

Too young to understand everything, old enough to understand that something terrible was happening to the uncle who could make anything.

Broken work again.

Aunt Bess planted herself like an oak in human form, hands on hips, lips pressed so tight the lines around them looked like they’d been carved with a knife.

When Nathaniel finally stepped up onto the crate, the yard stilled.

“You all know me,” he began, voice pitched to Carrie.

“You know, I am not a man who airs his private troubles in the yard.

” Nobody laughed, but a couple of the white men smirked, “But what happened in my house last night was more than a private trouble,” he continued.

“It was an offense against the order God himself set down.

If I hide it, I invite worse.

He let his gaze sweep slowly across the black faces first, then rest on the white ones, as if to remind each group who he believed he stood above.

“I came home early from town,” he said, and found my wife in my bed with one of my slaves.

A murmur rippled through the white men.

One gave a low whistle that he smothered quickly.

Another shook his head in exaggerated disbelief, as if the idea offended him on a moral level, and secretly fascinated him on another.

Among the enslaved, the reaction was smaller, but deeper, a sucked in breath, a muscle jumping in a cheek.

No one was surprised it had happened.

They were shocked he was saying it loud.

Marion,” Nathaniel called toward the house.

“Come forward.

” She stepped down from the porch, pale as if she’d left some of herself in the cool shadow behind her.

Her hair was pinned tight now.

Her chin lifted just enough to suggest she was holding herself up, not being held.

She walked to the space beside the crate, hands twisting in her skirt.

Tell them,” Nathaniel said loud enough for everyone.

“Tell them exactly what you did.

” This was the moment everyone expected the script to follow a familiar line.

The white men were waiting for the claim of assault, of seduction, of a black beast who had slipped into a white lady’s bed in the dead of night.

A story that would let them pity Marion, condemn Jonas, and walk away smug about a world that always put blame where they thought it belonged.

Marion looked at Jonas.

He stood several paces away, wrists shackled, back straight.

He did not look at her.

He looked past her at something no one else could see.

His eyes didn’t plead for rescue.

They waited for the blow.

I Marian’s voice caught.

If she lied now, he would die for it.

If she told the truth, they both would in different ways.

“I called him to the house,” she said at last, each word like a stone she had to lift.

“I asked him to sit with me during the storm.

I invited him to stay.

I invited him into the bed.

” Nathaniel’s head jerked slightly, not because the confession shocked him, but because he hadn’t expected her to make it so plainly in front of other men.

A rustle went through the white ring, some faces tightening in performative outrage, others lighting briefly with crude interest before smoothing again.

You hear her,” Nathaniel said, seizing the moment.

“By her own words, my wife chose to share my bed with a man from my quarters.

” He turned to Jonas.

Now you, he said, “Did you force her? Did you trick her? Or did you see an empty space on the mattress and decide you’d earned it?” Jonas’s throat felt like dry cotton.

He swallowed once.

I did what I’ve been trained to do, he said slowly.

She called.

I came.

She said, “Stay, I stayed.

” A slave saying no to a white order don’t mean much in this county.

A sharp laugh broke from one of the planters.

“Listen at him,” the man drawled.

“Talking like some kind of philosopher.

” Heat climbed Nathaniel’s neck.

He had not brought his neighbors here to have them admire Jonas’s mind.

“Did you touch her without permission?” he demanded, voice cracking like a whip.

“No, sir,” Jonas said.

“I touched her when she reached for me.

I laid where she told me lay.

Every choice I ever had on this land got a rope tied to it on the other end.

” Laya shut her eyes briefly.

She could hear their mother in those words speaking through him.

Aunt Bess’s jaw worked like she was grinding the truth into dust so it wouldn’t choke her.

Nathaniel turned his back on Jonas and face the white men again.

You see my trouble, he said.

If I do nothing, every man and woman on this place will think my rules bend.

that a slave can touch what belongs to me and walk free if he talks pretty enough about storms and loneliness.

He gestured toward Marion without actually looking at her.

My wife has shamed herself and me, he went on, but the law and custom give me options.

I could have this man whipped to death.

I could hang him from this very branch.

I could send her away to an asylum and tell the world she lost her senses.

A low murmur of appreciation moved through his audience.

Brutal options spoken plainly reminded them they lived in a world where such choices belong to them.

But a man in my position has to consider more than righteous anger, Nathaniel added, shifting his tone.

I have obligations at the bank, to my creditors, to the men who trust me as a business partner.

There it was again, the calculation.

This man, he said, stabbing the air in Jonas’s direction without turning his head.

Is strong, young, trained.

He’s kept this house standing when the beams sagged and the wheels cracked.

A body like that is worth money.

and I find I am not in a position to throw money away.

The white men nodded.

This part they understood intimately.

Sin was one thing, value was another.

So here is my judgment, Nathaniel declared.

Marian Crowell will remain in this house as my wife under my eye.

She will not attend dances or socials.

She will not go visiting.

Her world from this day will be these walls and the knowledge that every person who looks at her knows what she did.

That will be her sentence.

He turned fully to Jonas.

You, he said, will be sold, not whipped to death, not strung up.

I will let your back earn me something instead of wasting it against the post.

Tomorrow at first light you will go to market.

Whoever buys you can decide how much more you pay.

Marian flinched as if he’d hit her.

Nathaniel, please, she said under her breath.

So low most of the white men pretended not to hear.

If anyone is to be cast out, it should be me.

I chose.

I He knew what he was.

Nathaniel snapped, cutting across her.

and so do they.

He nodded toward the circle of enslaved people.

Let it be a lesson, he said, raising his voice.

You touch what’s mine.

I’ll turn your life into coin before the week is out.

He slammed the Bible shut with a sharp report.

This trial is ended.

The white men relaxed.

They clapped each other on the shoulder and pronounced themselves satisfied.

They had come for outrage, confession, and a show of control.

Nathaniel had given them all three and thrown in an object lesson about protecting value for the bankers.

Besides, they would ride home and at supper tell the story of how Cra handled his business, how he’d kept his temper, kept his property earning, kept his wife penned.

A man you could still do dealings with.

The enslaved people drifted away slowly, like the air itself had turned to syrup around their legs.

Laya slid through the crowd to Jonas’s side as the overseer’s men moved to take him back to the smokehouse.

She pressed something small and soft into his shackled hand.

“Mama’s cloth,” she whispered.

“So you remember you was ours before you was his.

He closed his fingers around the worn scrap of faded blue.

The touch of it nearly undid him more than any blow would have.

He swallowed hard.

I’ll remember, he said.

Marian stepped forward, reckless, close enough now to see the bruise blooming across his jaw, the dried blood at the corner of his mouth.

“I’m so sorry,” she whispered, words shaking.

I thought I could steal a little comfort and pay for it myself.

I didn’t understand he’d make you the price.

Jonas met her eyes for the first time that day.

You understand now? He said quietly.

That’s something most never bother.

She wanted to promise she would fix it, that she’d find a way to buy him back, to send letters, to follow him.

But she knew the limits of her world, her father’s name, her husband’s debts, the narrow paths white women could walk without being locked up or cast out.

Wherever they send you, she whispered instead, throat tight.

“You were not just what he called you today.

” “And you ain’t just what he called you, neither,” Jonas replied.

Remember that when you hear your name come out twisted.

They pulled him away before she could answer.

Before dawn, the sound of wagon wheels jolted the quarters awake.

Laya had not slept.

She sat on the edge of her pallet, her son’s back warm against her arm, the scrap of blue cloth’s twin clutched tight in her fist.

A knock came hard and official against the cabin door.

Bring out the boy,” a white voice called.

“Master wants him ready.

” They didn’t say Jonas’s name.

They didn’t have to.

Every man in that room knew exactly which boy they meant when they spoke like that.

Jonas stepped out into the cool, gray morning, wrist chained, chin lifted.

The air smelled of damp dirt and yesterday’s smoke.

Somewhere a rooster crowed like the day was just another day.

Nathaniel waited by the wagon, hat pulled low against a sky that looked almost clean again, as if the storm had scrubbed the guilt off it.

“Get up,” he said, not looking Jonas in the eye.

Jonas climbed into the wagon bed.

The boards were rough under his bare feet.

The chains at his wrists clinkedked softly against the wood.

Laya rushed forward before the driver could snap the res.

Here, she said, pushing a small bundle into his bound hands.

The rest of it.

Inside was a slightly larger strip of the same blue cloth torn that morning from the hem of her one good dress.

The dress their mother had once mended by firelight in Virginia.

“So you remember,” she said, voice breaking.

“You was ours before you was his, and you still ours wherever you go.

” Jonas’s fingers closed so tightly around the cloth his knuckles went pale.

For a moment his shoulders sagged.

Then he straightened again the way a man does when he knows too many eyes are watching for weakness.

“Look after yourself,” he said, “and the boy.

” “If they let me,” she answered.

The word if did more work in that sentence than any of the others.

Nathaniel cleared his throat sharply.

“We done,” he said.

“Lila, back to your work.

I don’t pay you to cry in the yard.

” The lie sat between them.

He didn’t pay any of them for anything, but no one corrected him.

The wagon lurched forward.

Jonas watched the great oak slide past, the same tree he’d stood under, while his fate was spoken over his head.

Its branches stretched wide and indifferent.

The leaves whispered in the soft breeze that had refused to show itself during the storm.

The tree would outlive them all.

A few house servants watched from the kitchen door.

Aunt Bess stood in the shadow just inside, arms folded so tightly across her chest, her fingers dug into her own flesh.

upstairs behind a curtain she hadn’t dared pull all the way aside.

Marion watched the wagon roll across the yard and down the lane until the dust swallowed it.

She pressed her fingertips against the glass as if she could hold him back with skin and regret.

Nobody called her name.

No one invited her down to say goodbye.

In Nathaniel’s eyes, she had forfeited the right to grieve for the man whose sale was buying her another few months of respectability.

The wagon rattled toward town.

Mashan and Sons kept their yard busy.

Cattle loaded in pens, horses stamped, and men moved through lines of human beings.

With the same appraising eyes, they turned on livestock.

Jonas was unloaded with three others and lined up along a rail.

A cler with inkstained fingers walked down the row with a ledger reading details from the papers Nathaniel handed over.

Male mid20s fieldtrained, he muttered.

No major injuries, tools, carpentry.

Good with wood, Nathaniel said.

Keeps the place from falling down.

knows how to mend near anything.

Handy, the clark said, making a notation.

Handy fetches better.

Nathaniel’s jaw tightened.

That was all this day was about now.

Turning flesh into numbers that made Maron relax.

On the block, the auctioneers’s voice rose and fell like a preacher.

But the gospel he preached was profit.

One by one, men and women were hauled up, spun around, made to open their mouths and flex their arms.

Bids flew.

The gavvel cracked.

Lives shifted direction for the price of a mule.

When Jonas’s turn came, he climbed the three steps to the platform on his own.

If he was going to be sold, he would not be dragged.

Next lot, the auctioneer called, placing a hand flat on Jonas’s shoulder like he was displaying good cloth.

Prime man, strong, good field hand, trained in housework and repairs, keeps a big place in working order, who’ll start me at 300.

275, came the first voice.

300, 3 and a/4, 340.

Nathaniel watched the bids rise, each shout a step away from the cliff Marshon had hinted at.

At 360, the bidding slowed, sweat beaded at his temple.

He needed the number higher.

A tall man with a cane, dressed finer than most in the yard, raised two fingers lazily.

“370,” he said.

The auctioneer’s smile broadened.

370 I have.

Do I hear 380? Silence except for the shuffle of feet and the restless stamp of a bay mayor nearby.

371s.

The auctioneer called twice.

Sold.

The gavl cracked.

In the crowd, Hail Maron himself raised his chin toward Nathaniel in a small satisfied nod.

Later, in the cramped office that smelled of ink and stale cigar smoke, Nathaniel signed the bill of sale with a hand that only shook a little.

“You got a good price out of a bad situation,” Marshon said mildly, glancing over the paper.

“Not every man has the stomach to turn domestic embarrassments into opportunity.

Some just hang the problem and call it a day.

” Hanging doesn’t impress your father, Nathaniel said through his teeth.

Numbers do.

Marshon chuckled.

Spoken like a man who understands how the world works.

Nathaniel didn’t reply.

The weight of the coin purse at his hip felt heavier than it should have.

For the rest of his life, every time he stepped into his own bed, he would feel the ghost of that night in the mattress, the sight of his wife’s hand on another man’s arm, and remember that he had turned it into silver.

Jonas handed over to his new owner, a man named Cder with Sugarfields in Louisiana, did not look back, as he was led away from the yard.

There was nothing left behind him now, but stories he would never be allowed to correct.

On the riverboat, carrying him farther south, he lay on the rough planks of the hold, with other men bound for cane fields that broke backs faster than cotton ever had.

Through a crack in the boards above, he could see a strip of sky the color of old putter.

The blue cloth Laya had given him was wrapped around his wrist under his sleeve, frayed edge knotted twice.

Men called him by the new name Culus Clark had written down, and he answered because he had to.

But in the dark, when the boat creaked, and the river slapped the hull, he pressed his thumb against that threadbear scrap and whispered his own name like a promise.

Back at Ashefield Crossing, life rearranged itself around the absence without admitting it.

The white neighbors told the story one way at their tables.

Nathaniel Crowell had caught his wife in bed with a slave, kept his head, sold the man, and put his house in order.

They tutted over Marian’s fall, praised Nathaniel’s restraint, wondered whether she shouldn’t be sent to some quiet place for her nerves, and assured each other that such temptations could be avoided in their own homes with stricter oversight.

In the quarters, the story sharpened in the retelling.

They talked in low voices on hot nights about the way the master had stood under the oak with a Bible, turning a woman’s loneliness and a man’s lack of choices into a sermon about order.

They talked about how Marian had refused to save herself by calling Jonas a monster.

How for once a white woman had not thrown all the blame downhill just because the slope was there.

It did not make her innocent, but it lived alongside her guilt.

Marian moved through the rooms of the house like someone walking underwater.

Her world shrank to the spaces Nathaniel allowed her.

She still supervised meals and linens, still signed lists for the cook, and scolded housemmaids for scuffed floors.

But there was a new weight in the way other white women looked at her when they did come calling.

Some pied, some judged, none forgot.

The enslaved people watched her, too, with eyes that held both anger and something more complicated.

She had brought ruin down on Jonas with a trembling hand in the dark.

She had also stood in front of God, landowners, and her own husband and said, “He did not force me.

” In a land where lies from mouths like hers had killed more black men than fever and work combined, the refusal to tell that lie mattered.

Quietly, in the thin spaces where Nathaniel’s attention did not reach, Marian began to push against the edges of her cage.

She made sure Laya’s boy was kept as a runner around the yard instead of being sent out to the most brutal roars.

When Nathaniel spoke of selling off a whole family to cover another note, she argued not with tears, but with numbers.

“Splitting them will cost more than it earns,” she’d say, pointing at the account books.

“The father’s the best at the new plow.

The mother keeps the cook from wasting flour.

You’ll lose efficiency and reputation.

Buyers talk.

Nathaniel listened when she sounded like the banker men he respected.

He prided himself on being rational.

If she wrapped mercy in profit, sometimes he let it stand.

She learned more about those ledgers than any wife was expected to know.

Not because she cared about profits for their own sake, but because she had seen how easily a person could be turned into a line of ink and wanted, in some small way to slow the process.

At night, when the house was finally quiet, she sometimes pulled a scrap of paper from her sewing box, wrote Jonas Reed in tiny letters right in the middle, stared at the name until her eyes blurred, then held it to the candle flame, and watched it curl into ash.

It was a poor ritual, but it was all she had.

A way to keep him from disappearing entirely into the blank space where lost slaves went when their names left one ledger for another.

In Louisiana, the work on cold place was as cruel as the stories had promised.

Sugar was a different kind of monster than cotton.

The cane cut hands to ribbons.

The boiling houses stole breath and skin.

Men aged 10 years in two, but people clung to life anyway.

Calder noticed quickly that Jonas’s hands knew more than how to swing a cane knife.

Within weeks, Jonas was patching gears, shoring up a sagging roof beam, fixing a pump so the water ran more steady.

You called to said one evening, squinting at him.

You’re Crow’s handy buck, aren’t you? Heard you kept a whole rotten mansion from falling in on itself.

Jonas kept his gaze lowered.

I fix what’s broke, master.

Well, now you’ll fix what’s mine, Cal said.

You keep this place running.

I might let you keep breathing longer than the others.

It was not kindness.

It was investment.

He was a moving gear in another man’s machine.

But even a gear could learn the rhythm of the engine.

At night, in the cramped cabins by the cane, Jonas listened to new stories, tales of men who’d slipped away and headed for swamps of whispered words like abolition and war, spoken in the dark, as if they were spells that might call down a different future.

He did not let himself believe in miracles, but he kept his ears open.

One humid night, an older man with scars braided over his shoulders like dried rivers leaned close.

“You from Georgia?” the man asked.

“Yes, Ashefield Crossing,” Jonas said before he could stop himself.

The man’s eyes sharpened.

“I heard of that place,” he murmured.

Some trader passed through months back talking about how the master there turned his wife’s shame into hard cash.

Sold a boy instead of stringing him up.

Said it like it was clever.

He didn’t know the name.

Just said the boy stood straight till the end.

Jonas stared at the packed dirt floor.

That story ain’t his to tell, he said quietly.

ain’t yours, neither.

It’s ours.

” The man nodded slowly, like he understood something important that Jonas hadn’t said aloud.

“Then you better live long enough to carry it,” he said.

“Years slid past in hard seasons, measured out in blisters and harvests.

News came in pieces, the way it always did to the cabins.

A fight at a fort somewhere, a line of blue coats on the move, a rumor that some men in the north were declaring all slaves free on paper, even in places where white men still held the whips.

On a sticky afternoon, while Jonas was perched on a ladder, repairing a cracked beam in one of the boiling houses, Cder stormed in, face flushed.

“Get down!” he barked.

Jonas climbed down carefully.

“You can patch beams and fix wheels,” Cer said, jabbing a finger at his chest.

“But you can’t mend a country.

Yankees are coming.

Some of the boys are slipping off to follow them.

I won’t have you stirring trouble.

I ain’t stirred nothing,” Jonas said.

He had learned to keep his expression smooth, his voice flat.

“Don’t care,” Cer snapped.

You’re more trouble than you’re worth if you start thinking.

I’m selling you east.

Some lumber outfit needs strong arms.

Let them worry about you.

I’ve got canain to protect.

So it was that Jonas found himself once again on a wagon.

Once again in a yard where men talked prices over someone else’s body.

On the road east, this time with other men whose wrists were not chained quite so tight, they passed a crooked sign half rotted through by rain that pointed north.

Savannah, it said, Ashefield.

He looked at the fork for a long moment as they jolted past, the blue cloth under his sleeve warming against his skin.

Back in Georgia, war carved its own scars into the land.

Soldiers came and went, some in gray, some in blue, some just in ragged uniforms, more dust than cloth.

Fences went down, barns burned, boys left, and didn’t come back.

Nathaniel Crowell did not die gloriously in battle.

He collapsed one evening on the steps of the courthouse in town, still arguing with Hail Maron about what could be saved and what could not.

His heart simply decided it had carried enough.

Marshand and Sons took Ashefield Crossing like they took any other property.

With papers and quiet efficiency, they brought in a new man to manage the land, a northerner named Abram Klene, with a stiff suit and a softer voice, who spoke about contracts and freed labor and reconstruction, as if words alone could change the bones of the place.

The people in the quarters were told they were free, then asked to sign papers that made sure they stayed right where they had always been.

Only now with different words on top of the ledger.

Marion, widowed, and suddenly less important in the eyes of men who now measured worth in different columns, found herself given choices that all felt like variations on the same trap.

She could go back to her father’s house and live under his size.

She could marry some cousin of Marons’s and become a decorative asset in a different home.

Or she could stay on at Ashefield Crossing as something between a guest and a servant, Klein’s housekeeper, helping him understand the rhythms of a land that did not want him.

She chose the option that kept her nearest.

the people whose lives had already been shaped by her worst decisions.

Under Klein’s looser oversight, she started writing more than menus.

In a small leather-bound book she kept hidden behind a loose brick in the fireplace, she wrote down everything she remembered of that day under the oak.

the exact words, the faces, the way Jonas had stood, the way Laya had held her son.

She did not write to cleanse herself.

There was no cleaning this.

She wrote so that when men like Maron opened their ledgers, if anyone ever laid her book beside them, the pages would not match.

Somewhere in the world, the truth would live in ink that was not the banks.

Years later, after the war had chewed up so many things that were supposed to be unshakable, a tall young man walked up the overgrown drive to what was left of Ashefield Crossing.

The house had half collapsed.

Vines punched their way through cracked shutters.

The porch sagged.

The great oak still stood, though one massive limb was dead and gray.

The young man wore a faded shirt with the sleeve rolled carefully above his right wrist.

Tied there was a scrap of blue cloth so old it was more memory than fabric.

He stopped under the oak and looked up into its branches with an expression that held no fear, only hard, steady recognition.

“I thought you’d be bigger,” he said to the tree.

He had his mother Laya’s eyes.

His name was Josiah Reed, and he had grown up on stories told in whispers about a man named Jonas who had once stood under a Georgia oak and refused to lie even when the truth was sharpened against his neck.

about a white woman who had spoken one truth when everyone expected a prettier lie, and how it had saved no one, but still meant something.

Josiah had never seen his uncle.

Jonas had lived long enough after the war to buy a small patch of land with a few other men, what had once been a corner of someone else’s plantation, and to plant crops under his own name.

He had split logs with his own axe on his own schedule and died one winter with his boots under his own bed.

Before he went, he pressed the blue cloth into Josiah’s palm.

“Go see it for yourself someday,” he’d said, voice thin with age.

“The tree, the yard.

Don’t let their version be the only one.

Don’t go looking for revenge.

Go looking for remembering.

That’s the part they can’t sell.

Now Josiah stood where the crate had once sat.

He could almost hear the echo if he tried.

The rumble of Nathaniel’s voice, the restless shifting of feet, the crack of a Bible slamming shut.

He was not alone.

From the side of the ruined house, an older woman stepped into view, skirts brushing against weeds.

Her hair was white, braided, and coiled at the back of her neck.

Deep lines bracketed her mouth.

She leaned on a cane, but walked with more stubbornness than frailty.

“You Cra,” she called, suspicion sharpening the word.

Josiah shook his head.

“No, ma’am,” he said.

“Name’s Reed.

” Something flickered in her face.

“Layla Reed’s boy.

” “Yes, ma’am.

She stared at the strip of blue at his wrist.

“Should have known,” she murmured.

“Your mama cried like her heart was being pulled out her chest the day they sold your uncle.

Never seen someone hold on to a color like that.

” “You’re”? He hesitated.

“You Marian Crowell?” I was, she said, “A long time ago.

Folks just call me Marion now or that old fool still haunting Ashefield.

” He studied her weary expression.

She studied the set of his jaw.

You came for the tree, she said.

I came for the story, he answered.

His side.

Yours.

The part the men with ledgers didn’t write down.

She tilted her head, considering him.

Then she turned toward the broken front steps.

“Come in then,” she said.

“House ain’t much, but the ghosts will be glad of new years.

Inside the ruined parlor, dust moes spun in shafts of light.

The grand mirror over the fireplace was cracked down the middle.

On the mantle sat a small leatherbound book.

Marian picked it up with careful fingers and held it out.

I wrote it down, she said.

For years I thought it was vanity, thinking anyone would care.

Then I heard that Jonas lived long enough to send word back.

Long enough to tell his sister to send you here.

Seems the story wanted both sides.

Josiah took the book.

His fingers brushed the edge of the stiffened pages.

He could feel Jonas’s cloth warming his wrist.

Outside the oak’s branches shifted in a tired breeze.

I heard their version, he said.

In town, men still talk about Crowl like he was clever.

Turned shame into silver, they say.

Laugh like it’s a good trick.

He looked up, eyes hard.

I’m tired of their tricks.

Marion sank into a warped chair, the ghost of old grace in the way she folded her hands.

Then let’s give the story back to the people it belonged to.

She said, “You tell me what your uncle told you.

I’ll tell you what I saw between us.

Maybe we can make something that doesn’t serve them anymore.

So they sat in the broken house on a failing plantation that had once thought itself eternal and stitched together the tale of a storm, a bed, a trial under a tree, a sail, and a life that went on anyway.

Years later, when folks in Georgia spoke of Ashefield Crossing, the story had changed.

The white men’s version about a master who’d cleverly turned his wife’s sin into cash still floated around some circles the way old lies do.

But another story had taken root, told in kitchens, churchyards, and under other oaks up and down the county.

They did not say Jonas Reed was sold because he forgot his place.

They said he was sold because Nathaniel Cra was drowning in debt and decided another man’s body made a convenient raft.

They did not say Marian had been dragged into sin by a black predator and saved by her husband’s justice.

They said two lonely people reached for each other in a world built to punish that reaching and the man with the most power made sure he did not pay the highest price himself.

The official records never changed.

They still showed in neat lines of ink that in the year before the war a certain Nathaniel Crowell reduced his note at Marshandon Sons.

They still listed the sale of one male slave, approximately 25, sound and able to a Mr.

Cder of Louisiana.

They did not mention the storm that rattled the window panes, or the way a woman’s hand trembled on a man’s arm in the dark, or the way a whole plantation held its breath while a Bible and a silver cane turned suffering into a performance under a tree.

But in the stubborn corners of memory, the ledgers could not touch.

The story belonged to someone else.

It lived in the warning mothers gave their daughters about loneliness and the bargains it might make with power.

It lived in the way men like Josiah tied scraps of blue cloth around their wrists, silent memorials that defied paper.

It lived in the fact that in the end the plantation fell, the banker’s name faded, the master’s grave cracked, and yet the tale of the man who would not lie at his own trial.

And the woman who spoke one dangerous truth kept traveling past from mouth to ear, from generation to generation, not as a neat moral lesson, not as a joke over brandy, as a reminder that even in the heart of a system built to turn people into numbers, there were moments when someone refused to let those numbers be the last Word.

News

Ilhan Omar ‘PLANS TO FLEE’…. as FBI Questions $30 MILLION NET WORTH

So, while Bavino is cracking down in Minnesota, House Republicans turning the heat up on Ilhan Omar. They want to…

FBI & ICE Raid Walz & Mayor’s Properties In Minnesota LINKED To Somali Fentanyl Network

IC and the FBI move on Minnesota, touching the offices of Governor Tim Walls and the state’s biggest mayors as…

FBI RAIDS Massive LA Taxi Empire – You Won’t Believe What They Found Inside!

On a Tuesday morning, the dispatch radios in hundreds of Los Angeles taxi cabs suddenly stopped playing route assignments. Instead,…

Brandon Frugal Finally Revealed What Forced Production to Halt in Season 7 of Skinwalker Ranch….

The Secret of Skinwalker Ranch became History Channel’s biggest hit. Six successful seasons documenting the unknown with real science and…

1 MINUTE AGO: What FBI Found In Hulk Hogan’s Mansion Will Leave You Shocked….

The FBI didn’t plan to walk into a media firestorm, but the moment agents stepped into Hulk Hogan’s Clearwater mansion,…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage… It started like any other evening…

End of content

No more pages to load