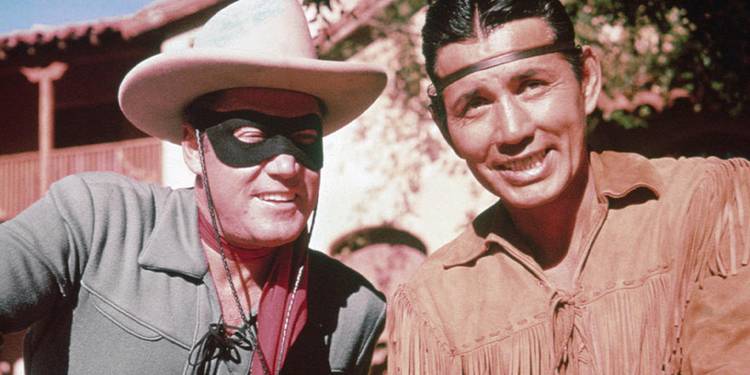

⭐ THE SECRET HISTORY OF JAY SILVERHEELS: The Real Story Behind Hollywood’s Most Famous Sidekick — And the Role That Nearly Broke Him

THE THREE WORDS THAT SHATTERED THE MYTH

In 1957, at the height of his fame, Jay Silverheels — the man millions knew only as Tonto from The Lone Ranger — returned to his home community on the Six Nations of the Grand River Reserve in Ontario.

Reporters, fans, and curious visitors followed him everywhere, eager to talk to the quiet, dignified actor who stood beside one of the most recognizable heroes in American pop culture.

Someone asked him, casually, almost playfully:

“So, how does it feel to be Tonto?”

Jay paused, eyes level, voice steady.

“Tonto is stupid.”

Three words.

Softly spoken.

But heavy enough to rattle the television industry.

Tonto — the loyal, simplistic, broken-English-speaking Native American sidekick who rode behind the masked hero — was the role that made Jay famous.

It was also the role that nearly destroyed him.

Behind the scenes of the wildly successful 1949–1957 TV series, Jay Silverheels battled:

racism

pay discrimination

on-set hostility

cultural humiliation

and an industry that saw Native actors as expendable props

Yet he smiled through it all, carrying a weight Hollywood never acknowledged.

This is the true story the cameras never showed.

A CHILDHOOD BUILT ON STRUGGLE, SILENCE, AND SURVIVAL

Before Hollywood, before Tonto, before the silver screen made him a household name, Jay Silverheels was Harold J. Smith — born in 1912 on the Six Nations Reserve in Ontario.

He was one of at least ten siblings crammed into a small house, raised by a father whose life had been carved by war and silence.

His father, Alexander George Edwin Smith, was a Cayuga war hero decorated in World War I. He returned home:

partially deaf

traumatized

and struggling on a disability pension of $49 a month

His medals could not feed his children.

His pain could not be treated.

His sacrifices went largely unseen.

Harold’s mother, Mabel, kept the family afloat using traditional medicines and community support — not because it was quaint, but because local doctors refused to see them or they simply couldn’t afford care.

Hardship shaped Harold early:

poverty

cultural oppression

government policies designed to erase Indigenous identity

One of his sisters was sent to a residential school.

She returned unable to speak Mohawk fluently.

Harold never forgot that.

He grew up watching a family, a culture, and a community survive in spite of everything thrown at them.

That quiet endurance became the backbone of his life — and later, of the battles he would face in Hollywood.

III. THE ATHLETE WHO OUTRAN POVERTY

Long before Hollywood noticed him, Harold was already famous somewhere else: the lacrosse arena.

By age five, he was sprinting across local fields with a speed that stunned spectators.

By nineteen, he was a professional.

By twenty-five, he was a legend.

He played under the name Harry Smith, racing through Buffalo, Rochester, Atlantic City, Toronto — dragging hope behind him and poverty behind that.

His cousins and brothers played with him.

Their nicknames — Porky, Beef, Chubby — became part of the traveling parade.

Harold’s own nickname arrived one night after he outran a defender so fast it looked like light flashed off his shoes:

“Silver Heels.”

It stuck.

Newspapers printed it.

Fans chanted it

Promoters sold it.

For the first time in his life, Harold had a name that lifted him — instead of holding him down.

But athletic fame didn’t erase the reality of the era.

He grew up in a country that tried to erase Indigenous languages, customs, and even people.

He watched neighbors endure punishments for speaking Mohawk.

He watched families break apart.

He watched poverty swallow opportunities whole.

But he ran anyway — as if outrunning the world that tried to limit him.

THE PUNCH THAT CHANGED EVERYTHING

During the height of his lacrosse career, Harold stepped into a boxing ring at Madison Square Garden for the Golden Gloves tournament.

Fast hands.

Fast feet.

Big future.

Then a single punch broke his jaw in two places.

His boxing career ended that night.

His lacrosse dominance dimmed.

His bills increased.

But the prize money helped.

And the pain taught him something he would need later:

You can take a hit — and keep performing.

It was a lesson that would follow him onto Hollywood sets.

THE CHANCE THAT OPENED THE DOOR TO HOLLYWOOD

In 1937, Harold’s lacrosse team toured Los Angeles. During a training session at Gilmore Stadium, comedian Joe E. Brown noticed the tall, striking athlete.

Hollywood didn’t recruit him for his voice or his acting chops.

They wanted his agility.

His physicality.

His exotic look — a word studios used freely to describe Native actors.

Brown gave him a small stunt role.

Eleven takes.

A diving catch.

$150.

More money in a week than Harold had ever seen.

A Screen Actors Guild card soon followed.

A new stage name: Jay Silverheels.

He didn’t get acting roles.

He got typecast as “Indian Scout #2,” “Warrior #3,” or “Brave Man with Spear.”

Studios made him strip to the waist during auditions.

They judged his body more than his voice.

They treated him like a living prop.

He accepted it.

There were no alternatives.

But he studied lines anyway.

Read Shakespeare.

Took classes.

Outworked half the lot.

He was determined to become more than a silhouette in someone else’s movie.

HOLLYWOOD’S RACIAL HIERARCHY — AND HOW IT SHAPED HIM

The Hollywood Jay entered was a segregated system that rarely allowed Native actors to be:

leads

romantic interests

complex characters

or portrayed with dignity

Roles went instead to:

Italian actors in red clay makeup

white stars speaking in broken English

stereotypes written by screenwriters who had never met a Native person

Jay Silverheels navigated this world quietly, carefully.

He earned respect among crew members for his discipline.

He earned admiration among peers for his steadiness.

He earned a living — barely.

But the system was rigged.

He’d land a speaking role, only to be uncredited.

He’d audition for serious films, only to be asked to “look more savage.”

He’d rehearse complex lines, only to be told to simplify them to fit a stereotype.

Even when he earned $350 a week for Drums Along the Mohawk in 1939—more than he’d ever earned in his life—he wasn’t invited to promotional events.

His face wasn’t considered marketable.

His culture wasn’t seen as dignified.

His talent was overshadowed by the color of his skin.

But in 1949, everything changed.

THE ROLE THAT MADE HIM FAMOUS — AND TRAPPED HIM

When ABC announced casting for The Lone Ranger TV series, most industry insiders believed they’d hire white actors for both roles — painting one to look “Indian enough.”

But Jay Silverheels auditioned anyway.

He beat 35 other actors.

On September 15, 1949, he became the first Native American to portray a Native character on American television.

Millions tuned in.

Children adored him.

Parents trusted him.

Producers celebrated him.

America finally saw a Native presence on screen — steady, loyal, brave.

But beneath that historic moment lay a darker truth.

“ME WAIT HERE”: THE LINES THAT CUT DEEPER THAN ANY PAY CHEQUE

The scripts written for Tonto were insulting:

broken English

simplistic phrases

wooden dialogue

submissive tone

Jay hated them.

He often rewrote or improvised lines on the spot.

Directors hated that.

One of them — the fiery Wilhelm Thiele — allegedly grew so angry on set that crew members had to physically restrain him from lunging at Silverheels.

Clayton Moore, the Lone Ranger himself, defended his co-star:

“Let it play. It sounds more natural.”

But tension simmered beneath the surface.

Jay was not allowed to speak proper English — even though he was articulate, fluent, and intelligent.

Hollywood wanted Tonto to sound primitive.

And the audience believed it.

UNEQUAL PAY, UNEQUAL CREDIT, UNEQUAL RESPECT

Silverheels made about $100,000 per season at his peak — roughly $850,000 today.

A good salary, until you compare it.

Clayton Moore earned nearly double.

Even though Jay:

appeared in the same number of episodes

performed many stunts

carried the emotional weight of representation

and helped shape the show’s cultural impact

But the financial inequality wasn’t the only injustice.

During early seasons, Jay didn’t even get a proper dressing room.

He and Moore changed clothes in a gas station restroom down the road.

It wasn’t until Jay refused to put his costume on in protest that the studio relented and built private dressing areas.

It was his first small victory.

One of very few.

THE PRICE OF FAME — AND THE TOLL ON HIS HEALTH

In 1955, disaster struck.

During a fight scene rehearsal, a stuntman collided hard with Jay.

Moments later, Clayton Moore saw him walking strangely.

He followed him to the trailer.

Jay was clutching his chest.

He had suffered a heart attack.

Even then, he worried less about himself and more about the job — fearful that missing weeks might jeopardize his position.

He ended up missing eight episodes.

Writers temporarily wrote him off the show, sending Tonto to “the capital for tribal business.”

It wasn’t just a line.

It was Hollywood telling audiences:

“Don’t worry. He’ll be back. But only when we say so.”

The show continued without him.

The world moved on without him.

And Jay understood, painfully:

Tonto was key to the show — but Jay was replaceable.

RECOGNITION WITHOUT RESPECT

When The Lone Ranger ended in 1957, Moore had a pathway to conventions, appearances, public tours, and steady work.

Jay did not.

Casting directors only saw Tonto, not the actor.

He spent the next decade playing:

nameless chiefs

background braves

stock characters with few lines

Even in movies where he delivered strong performances, studios refused to give him the roles he deserved.

He had become both famous and invisible.

The stereotype people loved had swallowed the artist who created it.

THE ECCOES OF RESISTANCE — HOW HE FOUGHT BACK

Jay didn’t choose indignation.

He chose action.

In the early 1960s, he co-founded the Indian Actors Workshop, a revolutionary effort to:

train Native actors

open doors to SAG membership

challenge studios

elevate cultural representation

He taught voice, movement, acting technique, self-preservation — everything he had learned the hard way.

Buffy Sainte-Marie supported the program.

Rod Redwing trained stunts.

Young Native performers flocked to it.

One of them later became iconic:

Michael Horse, who played Tonto in the 1981 film.

Decades of Native talent owe their careers to Jay’s fight — many without realizing it.

HIS FINAL YEARS — AND THE MOMENT HOLLYWOOD COULDN’T IGNORE

In the 1970s, silver curls replaced the black braids.

Strokes weakened him.

His speech faltered.

But in July 1979, Hollywood did something it should have done decades earlier:

It gave Jay Silverheels a star on the Walk of Fame.

He arrived in a wheelchair.

Native dancers surrounded him.

Fans cheered.

The industry finally applauded a man it had exploited for years.

Jay could barely speak, but he whispered enough:

“Thank you.”

It wasn’t gratitude.

It was closure.

On March 5, 1980, Jay Silverheels passed away at age 67.

His ashes were returned to the Six Nations Reserve — to the land that shaped him.

THE LEGACY HOLLYWOOD DIDN’T EXPECT

Jay Silverheels was more than Tonto.

He was:

a pioneer

a barrier-breaker

a disciplined athlete

a warrior for representation

a quiet revolutionary

a man who refused to be defined by stereotype

He endured mockery, underpayment, racism, and disrespect — yet built a pathway wide enough for generations of Native actors to walk through.

Every Indigenous performer who speaks their truth onscreen today…

Every casting call demanding authenticity…

Every script consultant ensuring cultural accuracy…

Every role written with dignity…

All of that carries Jay’s fingerprints.

Because he didn’t just ride behind the Lone Ranger.

He carried Hollywood forward — one painful stride at a time.

THE REAL STORY BEHIND THE SMILE

For decades, America saw one version of Jay:

The loyal sidekick.

The smiling warrior.

The man who said “Me go now.”

But that wasn’t the real Jay.

The real Jay was a fighter.

A survivor.

A man who stared down a system built to erase him — and forced it to acknowledge him.

His life was a quiet rebellion disguised as silence.

His legacy is louder than any line Tonto ever spoke.

And his story is not the story of a sidekick.

It is the story of a man who changed Hollywood — even as it tried to keep him small.

News

Archaeologists Just Opened King Henry VIII’s Sealed Tomb — What They Found Is Unbelievable

Archaeologists Just Opened King Henry VIII’s Sealed Tomb — What They Found Is Unbelievable For centuries, people assumed King Henry…

Ilhan Omar in BIG TROUBLE…. Husband’s Winery Mirrors Minnesota Somali FRAUD

Ilhan Omar in BIG TROUBLE…. Husband’s Winery Mirrors Minnesota Somali FRAUD It’s we’re just we’re just uh trying to like…

FBI & ICE Raid Minneapolis Mayor — Cartel Tunnels and $420,000,000 Network

FBI & ICE Raid Minneapolis Mayor — Cartel Tunnels and $420,000,000 Network Minneapolis, please search for it. I spoke in…

FBI & DEA Uncover 1,400-Foot Tunnel in Texas — $2,000,000,000 Cartel Network Exposed

Tangle of tunnels used to traffic not only drugs but also highlevel drug kingpins themselves. 4:20 a.m. A federal raid…

Before He Dies, Eustace Conway Finally Reveals the Truth He Hid for 20 Years

Before He Dies, Eustace Conway Finally Reveals the Truth He Hid for 20 Years Thousands of people have died in…

Ilhan Omar ‘PLANS TO FLEE’…. as FBI Questions $30 MILLION NET WORTH

So, while Bavino is cracking down in Minnesota, House Republicans turning the heat up on Ilhan Omar. They want to…

End of content

No more pages to load