My husband vanished without a trace 15 years ago.

It was as if he disappeared into thin air.

The official investigation found nothing.

Even a reward led to no answers.

And now, years later, I know the truth.

And it is more horrifying than all the years of not knowing.

It was an ordinary day when a successful farmer and co-owner of an agricultural supply store needed to pick up parts for a combined harvester.

He flew to collect them in his own plane, following a familiar route that took less than an hour.

He was expected home by lunchtime, but he never returned.

A twoe search produced no results.

There were no wreckage fragments and no signs of a crash.

Investigators established that he had arrived to pick up the parks in poor physical condition, showing clear signs of illness.

The last time his plane was seen was almost immediately after takeoff, flying over a local school.

After that, it was as if it had dissolved into the air with absolutely nothing found.

On November 4th, 1983, the day began for Arthur Vance in a way that felt routine and unremarkable, shaped entirely by the demands of his work.

At 56 years old, Vance was a well-established farmer in Louisiana, a co-owner of an agricultural supply store, and a man known for managing his operations personally rather than from a distance.

He oversaw the harvest himself, monitored equipment usage, and involved himself in logistical decisions that others might have delegated.

That autumn placed particular pressure on his business.

The harvest season was reaching its critical phase.

Machinery was operating at full capacity, and even short delays threatened measurable financial losses.

Replacement parts for one of the combines had become essential, and waiting days for delivery was not an option he considered acceptable.

Because of this, Vance chose the most direct solution available to him.

He piloted his own aircraft, a blue and white Cessna 177 Cardinal from a private strip near his property in Kilbornne, Louisiana toward Vixsburg, Mississippi.

The trip was practical rather than spontaneous.

The parts had been ordered in advance, the route was familiar, and the flight was short enough to be completed within the same morning.

There was nothing unusual in his decision to fly himself.

Vance was an experienced private pilot who had completed this route multiple times in the past and regarded it as routine.

The flight to Vixsburg proceeded without incident.

Vance landed at the local airport in the morning, completed the necessary paperwork, collected the ordered parts, and prepared for the return trip.

Airport staff and employees at the parts supplier interacted with him briefly during this process.

Nothing in his behavior suggested urgency or distress.

Yet several people later recalled that he appeared unwell.

His complexion was noticeably pale, his movement subdued, and his speech minimal.

He did not complain of illness, nor did he request assistance, and at the time there was no reason to treat these observations as significant.

No formal notes were taken, and no reports were filed.

Only later would these details gain importance.

Between 10:30 and 11:00 a.m. , Arthur Vance departed from Vixsburg and set a course back toward Kilbornne.

Weather conditions were stable enough to permit flight, and no warnings or advisories were issued that would have altered his plan.

As the aircraft crossed over the city, it was observed by a teacher and a group of school children who were moving quickly toward their school building to escape the onset of rain.

They noticed the low-flying Cessna passing overhead, an ordinary sight in a region accustomed to small private aircraft.

That brief visual contact became the final confirmed sighting of Vance’s plane in the air.

Based on distance and speed, the return flight should not have taken more than 40 minutes.

People at the private airirstrip in Kilbornne expected Vance to arrive before midday.

When the plane did not appear within the expected window, the delay was initially dismissed as insignificant.

It was assumed he might have stopped elsewhere or encountered a minor issue requiring extra time.

As the hours passed and communication attempts failed, concern began to grow.

By early afternoon, it was clear that something was wrong.

Search efforts were initiated and continued intensively for the next two weeks.

Emergency response units, volunteer search teams, and aviation resources were deployed to examine the expected flight path and surrounding areas.

Forests were scanned from the air, wetlands, and bios were inspected, and open fields were checked for signs of wreckage or emergency landings.

Reports from residents were evaluated, and any mention of unusual sounds or sightings was followed up.

Investigators also considered the possibility that weather conditions or mechanical trouble might have forced the aircraft off course.

Despite the scale of the operation, the search produced nothing.

No debris was located, no impact site was identified, and no traces of fuel or oil were found on land or water.

There were no emergency transmissions, no signals, and no evidence that the aircraft had attempted a landing elsewhere.

The absence of physical clues complicated every line of inquiry.

The plane appeared to have vanished without leaving behind the indicators typically associated with aviation accidents.

As days passed, investigators began to outline possible explanations.

Mechanical failure, navigational error, and disorientation were evaluated.

Another possibility involved a forced landing in a remote, inaccessible area.

More speculative theories also surfaced, including the idea that the disappearance had been staged or that the aircraft had been taken.

None of these scenarios could be supported by evidence.

The aircraft was properly registered.

The route was known, and Vance had no documented disputes or personal circumstances that suggested a voluntary disappearance.

He left behind his business, his family, and ongoing responsibilities, and there were no financial withdrawals, packed belongings, or preparations indicating an intention to vanish.

Eventually, the case was reclassified as a disappearance.

Active search operations were suspended, and the investigation shifted into an archival phase.

Files were stored, reports cataloged, and Arthur Vance’s name was added to the list of individuals missing under unexplained circumstances.

For his family and those close to him, the lack of resolution proved especially difficult.

There was no confirmation of death, no location to mourn, and no explanation to accept.

The plane was not found.

The body was not recovered.

The reason for his disappearance remained unknown.

The family of Arthur Vance took independent steps in an effort to locate the missing aircraft.

They publicly announced a monetary reward for any information leading to the discovery of the plane or its wreckage.

Notices were circulated locally and the offer was communicated to pilots, hunters, and residents familiar with the surrounding terrain.

Despite this additional incentive, no credible leads emerged.

No one reported seeing the aircraft, hearing an impact, or finding debris, and the reward produced no results.

For years, the case existed only as an unresolved file, a story without an ending.

It remained frozen in time, defined by unanswered questions and the absence of evidence.

Then, 15 years later, conditions changed, and what had once been hidden, began to surface, setting the stage for a development no one had anticipated.

In the summer of 1998, southern Louisiana experienced an extended and abnormal drought that dramatically altered the landscape.

Water levels in rivers, bayou, and wetlands fell to depths that had not been recorded in decades.

Areas that were typically submerged year round began to dry out, exposing mud flats, tree roots, and the bottoms of isolated inlets.

In several locations, the retreating water revealed terrain that had not been visible since the early 1980s when seasonal flooding had permanently reshaped the region.

One of those locations was a remote marshy section of Bayumakin.

The area was difficult to access even in dry conditions surrounded by dense vegetation and soft ground that limited regular human activity.

In 1983, during the year Arthur Vance disappeared, this entire section had been submerged under floodwaters, forming a continuous expanse of water bordered by thick stands of cypress trees.

Over time, layers of sediment and organic debris accumulated beneath the surface, concealing whatever lay below.

It was there that a local hunter noticed an object that did not belong to the natural environment.

Protruding from the mud was a piece of metal with sharp angular lines that contrasted with the surrounding vegetation.

At first glance, it appeared unnatural, and upon closer inspection, its shape suggested the tail section of an aircraft.

The hunter examined the exposed structure more carefully and realized it was not debris or abandoned equipment.

It was part of an airplane.

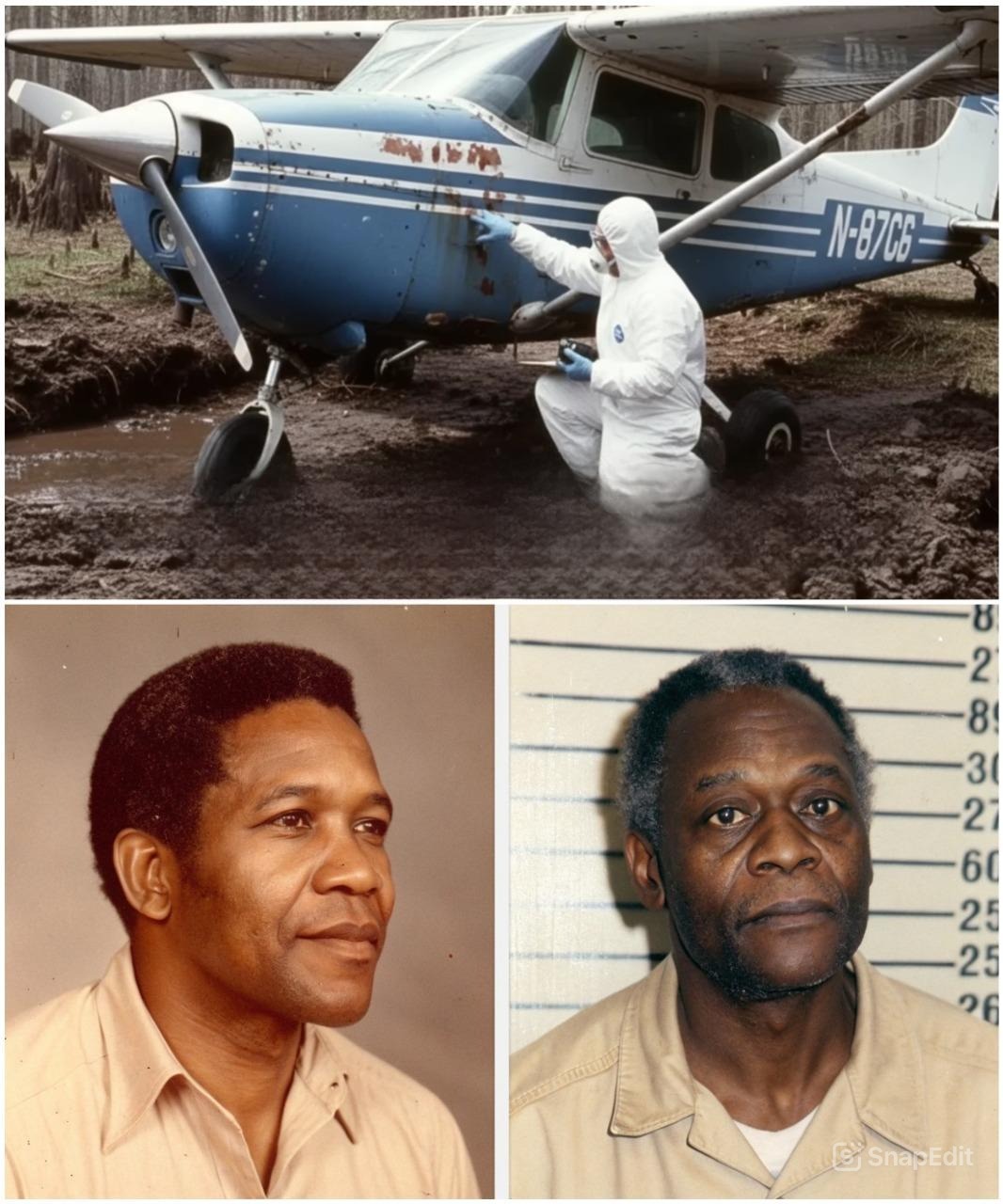

Authorities were notified and the location was secured.

Emergency services and representatives from aviation agencies arrived at the site to assess the situation.

As crews worked to clear mud and vegetation from the exposed section, the scale of the find became clear.

The aircraft’s fuselage was embedded deep in the ground at an angle of approximately 45°.

Most of the plane remained buried beneath thick compacted sludge with only the tail and part of the rear fuselage visible above the surface.

Once identifying marks became accessible, investigators confirmed the aircraft was a Cessna 177 Cardinal.

The registration number allowed officials to trace ownership within hours.

The plane belonged to Arthur Vance, the Louisiana farmer and private pilot who had vanished 15 years earlier during a routine return flight from Mississippi.

The discovery immediately transformed what had been considered a cold disappearance into an active case with physical evidence.

The location of the crash site added another layer of significance.

The plane was found only 8 miles from Vance’s home and his private landing strip in Kilbornne.

This proximity was striking given the extensive searches conducted in 1983.

At the time of his disappearance, however, the region where the plane came down was completely flooded.

The water level had been high enough to mask any impact site and the surrounding cypress growth would have obscured visibility from the air.

When the aircraft struck the surface, it sank into soft sediment rather than breaking apart, allowing it to disappear beneath the water line almost immediately.

Over the following years, the bayou continued to deposit layers of silt, plant matter, and river debris over the wreckage.

This natural process effectively sealed the plane in place.

The same conditions that made discovery impossible for more than a decade also created an environment in which oxygen was largely absent.

As a result, portions of the fuselage and internal components were preserved in a state that would not normally be expected after such a long period.

News of the discovery reached the Vance family quickly.

For 15 years, the disappearance had existed without confirmation of fate or location.

The plane’s emergence provided the first tangible evidence of what had happened, but it did not bring immediate clarity.

The aircraft showed no signs of an in-flight explosion or fire.

There was no debris field scattered across the surrounding area.

Instead, the wreck appeared contained as though the aircraft had descended in a controlled manner before impact.

Investigators conducted a preliminary examination at the site before arranging for the plane to be extracted.

Early observations raised important questions.

The position of the fuselage and the lack of structural fragmentation did not align with a high-speed or uncontrolled crash caused by mechanical failure.

There were no indications that the pilot had attempted an emergency landing or taken evasive action in the moments before impact.

These details suggested that Arthur Vance may not have been actively controlling the aircraft when it went down.

The circumstances pointed toward a sudden incapacitation rather than a gradual mechanical problem.

This possibility stood in contrast to the assumptions made in 1983 when the absence of evidence forced investigators to rely on speculation.

The discovery of the plane eliminated many unknowns while introducing new ones that demanded closer examination.

With these preliminary findings, authorities formally reopened the case.

The aircraft was carefully removed from the bayou and transported for a detailed forensic inspection.

Records from the original disappearance were retrieved and the investigation was transferred to a unit specializing in unresolved cases.

What had begun as an accidental discovery caused by extreme weather conditions was now recognized as the key to understanding a disappearance that had defied explanation for more than a decade.

After the aircraft was recovered from the muddy waters of Bayou Makin, the case entered a phase that had never occurred in 1983, a full systematic forensic investigation.

Unlike the original disappearance, which had been driven by urgency and speculation, this stage was defined by controlled procedures, documented evidence, and methodical analysis.

Investigators now had physical access to the aircraft and could finally examine what had been missing for 15 years.

Inside the cockpit, the remains of Arthur Vance were found in the pilot seat.

Their position was immediately significant.

Vance had not left the aircraft, nor had he attempted to exit it after impact.

There were no signs that he had tried to force a landing or abandon the plane in an emergency.

This finding eliminated several early theories that had circulated in 1983, including the possibility that he survived a crash and died later in the surrounding terrain.

The evidence showed that he had gone down with the aircraft.

In the cargo compartment, investigators found the same combine parts Vance had flown to Vixsburg to retrieve.

They were secured and undamaged, consistent with normal transport rather than emergency jettisoning.

Their presence confirmed that the flight had followed its intended purpose and route.

There were no deviations, no unscheduled stops, and no indication that Vance had altered his plans before disappearing.

The mission of the flight had been completed exactly as expected.

The case was formally assigned to Detective Leon Gilbert of the Louisiana State Police Cold Case Unit.

His mandate went beyond determining the mechanical cause of the crash.

From the outset, he was tasked with examining whether Vance’s disappearance could have resulted from criminal action rather than accident.

That distinction shaped every decision that followed.

Gilbert began by cataloging what the wreckage did not show.

There were no burn marks, no explosion damage, and no structural failures consistent with an in-flight engine malfunction.

The airframe showed no evidence of breakup at altitude, and the engine components did not display signs of catastrophic failure.

Attention then shifted to the aircraft’s interior systems.

During the inspection of the cabin, forensic specialists conducted a detailed review of the ventilation and heating assembly.

This process involved removing panels and examining areas that would not have been visible during routine maintenance.

It was in the aluminum heating duct positioned beneath the pilot’s seat that investigators noticed an anomaly.

Lodged deep inside the duct was a dense gray mass that did not belong to the aircraft standard construction.

The material was carefully extracted and preserved.

Its location suggested intentional placement rather than accidental intrusion.

The duct was narrow, enclosed, and inaccessible without deliberate effort.

The object was sent to a laboratory for analysis where specialists identified it as a fragment of technical cloth commonly used as shop rags in agricultural and mechanical settings.

More importantly, the fabric was saturated with an exceptionally high concentration of methyl parathione.

Methyl parathione was a highly toxic pesticide widely used in farming operations during the early 1980s.

Laboratory testing showed that the substance could only have entered the body through inhalation.

When exposed to heat, it released fumes capable of causing rapid poisoning.

The concentration detected in the cloth far exceeded what would be expected from environmental exposure or incidental contact.

This was not residue from routine farm use.

It was a deliberate application.

Medical consultants reviewed the findings and compared them with historical observations from the day of Vance’s disappearance.

Witnesses at the Vixsburg airport later recalled that Vance appeared unusually pale and visibly unwell before his return flight.

Those symptoms matched the early stages of methyl parathione poisoning.

The analysis supported a timeline showing that the poisoning had already begun before Vance landed in Vixsburg.

The preservation of the evidence was itself a critical factor.

When the aircraft struck the flooded bayou in 1983, it sank rapidly into mud and water, creating an environment largely devoid of oxygen.

This halted normal decomposition processes.

Organic materials that would typically degrade over time remained intact.

The cloth stayed lodged within the metal duct, shielded from external disturbance, allowing chemical traces to survive for 15 years.

For investigators, this rare set of conditions transformed what could have been an unsolvable case into one grounded intangible proof.

By this point, the theory of accidental crash had been effectively ruled out.

The aircraft had not fallen due to mechanical failure or navigational error.

Arthur Vance had lost control of the plane while airborne because he had become incapacitated.

The remaining question was no longer what had happened, but how it had been made to happen.

At this stage, Detective Leon Gilbert focused on establishing who had placed the poison cloth inside the heating system and when that act had taken place.

The method required access to the aircraft on the ground and knowledge of its systems.

It also required a motive strong enough to justify a complex and delayed form of killing.

To answer that, the investigation turned away from the wreckage and toward Vance’s personal and professional circle, examining events that had unfolded shortly before his disappearance.

By the time investigators reconstructed the financial situation of 1983, the case moved into a decisive phase.

The disappearance of Arthur Vance was no longer examined solely through technical findings from the aircraft.

The focus shifted toward motive and internal conflicts that had existed shortly before his final flight.

Financial records showed that one month before his disappearance, Vance discovered the loss of a large quantity of grain from his storage facilities.

The discrepancy was significant enough that it could not be explained by accounting error or routine spoilage.

In response, Vance initiated an internal audit of his operations, a step that directly threatened anyone involved in unauthorized sales or misappropriation.

Detective Leon Gilbert concentrated on tracing where the missing grain had gone.

Archival documents from a grain terminal in Arkansas provided the first concrete lead.

Records showed that one week after Arthur Vance disappeared, a company operating under the name CNR Holdings sold approximately 200 tons of grain.

Shipping documentation and inventory identifiers linked the grain to Vance’s storage facilities.

This transaction had never been flagged during the original investigation because the company name did not appear directly connected to Vance.

Further examination revealed that the beneficiary of CNR Holdings was Clarence Reed, who in 1983 served as the manager of Vance’s farm.

In that role, Reed had direct access to storage records, transport schedules, and sales documentation.

The timing of the transaction placed the sale immediately after Vance’s disappearance at a moment when no one was actively supervising the operation.

For investigators, this established the first clear financial motive tied to a specific individual.

Gilbert extended the financial review beyond the single transaction.

Records showed that after Vance disappeared, Reed resigned from his position as farm manager and began focusing on his own business ventures.

Over the following years, his financial situation improved rapidly.

He purchased agricultural machinery, expanded land holdings, and made several large acquisitions that did not align with his documented income prior to 1983.

Analysis of bank records and asset purchases indicated that the rise in Reed’s wealth began shortly after Vance’s disappearance, reinforcing the conclusion that he benefited materially from the events that followed.

With motive established, investigators turned to the question of access.

A former airport fuel attendant was located and interviewed.

He recalled the day Arthur Vance departed on his final flight.

According to the attendant, Clarence Reed arrived at the airport with Vance under the pretense of assisting with the loading of heavy combine parts.

While Vance went inside the office to file his flight plan, Reed remained alone near the aircraft for approximately 5 to 7 minutes.

This detail was critical.

It established a specific window during which Reed had unsupervised access to the plane.

Once the financial motive and opportunity aligned, the investigation shifted toward locating physical evidence connected to the method of poisoning.

In 1999, Detective Leon Gilbert and his team conducted an inspection of Arthur Vance’s farm, which remained operational and was still owned by his family.

With the family’s consent, investigators examined storage buildings that had been in use during the early 1980s.

These facilities contained fertilizers, pesticides, tools, and agricultural materials that had accumulated over decades.

Investigators considered the possibility that if the toxic substance introduced into the aircraft had originated from Vance’s own farming operations, its source might still be present among these long-standing supplies.

During the search, investigators located an original pesticide container manufactured in 1983.

The label identified the substance as methyl parathione, a highly toxic pesticide commonly used in agriculture at the time.

The container immediately drew attention because of its condition.

The lid was damaged and wrapped with electrical tape, indicating prolonged use and an attempt to prevent leakage.

This method of sealing suggested intentional preservation rather than disposal.

The canister was seized and sent for comprehensive laboratory analysis.

Chemical testing focused on comparing the substance inside the container with residue recovered from the cloth found in the aircraft’s heating duct.

Spectral analysis demonstrated that the chemical profiles of the two substances did not differ.

The composition and trace impurities indicated a shared origin.

This established that the pesticide used to poison the aircraft cabin came from the same source as the substance that had been stored on the farm since the early 1980s.

Forensic specialists also examined the electrical tape wrapped around the damaged lid.

On the adhesive side of the tape, they recovered a partial fingerprint.

The sticky surface had preserved the print despite the passage of time.

Although incomplete, the fingerprint retained sufficient ridge detail to be suitable for comparison and was documented and preserved as potential physical evidence connected to the source of the poison.

With the financial findings, witness testimony, and chemical evidence in place, the investigation moved into its procedural stage.

Clarence Reed was taken into custody for questioning at the age of 62.

To many, he appeared to be a successful businessman who had rebuilt his life after the early 1980s.

For investigators, this step marked the point at which accumulated financial records, documented opportunity, and emerging physical evidence justified direct procedural action.

Questioning began shortly after Reed was taken into custody.

He denied any involvement in Arthur Vance’s death and did not provide an explanation for the presence of the pesticide canister among materials stored on the farm.

When asked about his time at the airport on the day of the flight, he gave limited responses and avoided addressing specific actions.

Regarding the pesticide itself, Reed stated that such substances were common in agricultural operations and could have belonged to anyone with access to farm supplies.

As the interviews continued, Reed became increasingly uncooperative.

Acting on the advice of his attorneys, he chose to limit his statements and later remain silent during further questioning.

As part of standard procedure, investigators obtained his fingerprints for comparison.

The recovered print from the adhesive side of the electrical tape was then formally analyzed against the control samples.

The comparison confirmed that the partial fingerprint preserved on the tape belonged to Clarence Reed, establishing a direct physical link between him and the container that held the poison.

Investigators did not rely on Reed’s statements to advance the case.

The evidentiary structure was already in place.

The grain transaction documented motive.

Financial records demonstrated benefit.

The witness testimony established opportunity by placing Reed alone with the aircraft.

The canister confirmed access to the toxic substance.

Spectral analysis linked that substance to the poison introduced into the aircraft.

The fingerprint comparison provided physical confirmation tying Reed to the source of the poison.

Each element reinforced the others, forming a cohesive and internally consistent body of evidence.

Another critical step involved informing Arthur Vance’s family of the findings.

15 years after his disappearance, relatives were briefed on the results of the investigation and the confirmed cause of death.

The information was painful, but it brought an end to years of uncertainty.

What had long remained an unresolved disappearance was now understood as a deliberate act carried out by someone within Vance’s professional circle.

By the end of this phase, investigators possessed everything required to proceed further.

The source of the poison had been identified, the motive established, access confirmed, and physical evidence secured.

The investigation was now ready to move beyond discovery and evidentiary development toward a complete reconstruction of how the crime had been carried out.

When all key elements had been assembled, the investigation moved into its final analytical stage, a full reconstruction of how the crime unfolded.

This phase was not about introducing new facts, but about testing whether every known detail could be placed into a single continuous sequence that explained Arthur Vance’s disappearance without contradiction.

The reconstruction had to account for motive, timing, method, and outcome in a way that made sense from beginning to end.

In the final weeks of October 1983, Arthur Vance continued managing his farm as he always had, personally overseeing operations and reviewing inventory.

During this period, he discovered that a substantial quantity of grain was missing from storage.

The discrepancy was large enough to indicate deliberate removal rather than loss through spoilage or error.

Vance initiated an internal review of the situation, intending to identify how the grain had been taken and by whom.

This decision set events in motion that would not become visible until years later.

Clarence Reed, who managed the farm’s day-to-day operations, understood the implications of that review.

He had access to storage records, shipment schedules, and sales channels, and he knew that continued scrutiny would inevitably expose the diversion of grain.

Allowing the audit to proceed meant losing control over assets and facing consequences that could end his position and his financial prospects.

The situation demanded a solution that would stop the review permanently while avoiding direct confrontation.

The opportunity presented itself through Arthur Vance’s routine use of his private aircraft.

Vance flew alone, followed predictable routes, and maintained a consistent schedule.

The aircraft offered isolation and the appearance of normaly.

Any fatal outcome could be interpreted as an accident rather than an act of violence.

The plan relied on patience, familiarity, and concealment rather than force.

On the morning of the flight, Reed accompanied Vance to the airport under the pretense of helping load heavy equipment.

While Vance stepped away to complete flight paperwork, Reed remained near the aircraft.

During those minutes, he accessed the cabin and reached the heating system beneath the pilot seat.

A piece of technical cloth saturated with methyl parathione was placed deep inside the aluminum air duct.

The location ensured that it would not be visible and would remain undetected during routine inspection.

Methyl parathione was chosen deliberately.

At normal temperatures, it released toxic fumes slowly, producing mild exposure over time.

When heated, the concentration increased sharply.

The substance acted through inhalation, meaning no direct contact was required.

Once the cloth was in place, there was no further action needed.

The aircraft itself would complete the process.

As Arthur Vance took off and headed toward Vixsburg, the poisoning began gradually.

During the outbound flight, low concentrations of toxic vapor entered the cabin.

The exposure weakened him, producing fatigue and visible discomfort, but not enough to prevent him from landing or carrying out his planned tasks.

He collected the equipment and prepared for the return flight, unaware that the mechanism had already been activated.

Shortly after departure on the return leg, cabin temperatures dropped as the aircraft gained altitude and entered cooler, rainfilled air.

Vance turned on the heating system.

Warm air flowed through the duct where the poison cloth had been placed, rapidly increasing the concentration of toxic fumes in the cockpit.

Within minutes, the exposure intensified beyond what the body could tolerate.

Vance lost consciousness before he could recognize what was happening or attempt corrective action.

With no active control, the aircraft continued forward under its existing settings.

It did not transmit distress signals or make evasive maneuvers.

The descent was gradual, not chaotic.

The plane drifted off course and eventually descended toward a flooded marshland area.

The impact did not shatter the aircraft.

Instead, it entered soft terrain and sank into mud and water, remaining largely intact.

The surrounding environment concealed the crash site completely.

Flood waters and dense vegetation covered the fuselage and sediment quickly accumulated around it.

From above, there was no visible sign of wreckage.

Over time, layers of silt and organic matter sealed the aircraft beneath the surface, isolating it from oxygen and preserving its interior.

The poison cloth remained lodged in the heating duct undisturbed.

The aircraft’s condition, the lack of violent impact, and the absence of mechanical failure, all aligned with the sequence of events that had unfolded in the air.

What appeared to be a disappearance without explanation was in reality the final stage of a controlled and deliberate plan.

Arthur Vance never had the opportunity to react or escape.

The method required no confrontation, no witnesses, and no further involvement after the aircraft left the ground.

Once the process began, it unfolded on its own, hidden within the normal operation of the plane.

The disappearance achieved its purpose.

The internal review stopped.

Control over the farm’s assets shifted.

The aircraft vanished without trace, and for years, no one knew what had happened in those final minutes.

The environment erased visible evidence and preserved the truth.

At the same time, this sequence explained every element of what followed.

The symptoms observed during the flight, the lack of emergency response, the aircraft’s trajectory, and its long absence from view.

Nothing in the chain required coincidence or chance.

Each step flowed logically into the next, forming a single continuous event.

What unfolded that day was not an accident shaped by circumstance.

It was a calculated act executed quietly and designed to disappear along with its victim, leaving behind only unanswered questions until time itself exposed what had been hidden.

The collected materials formed the basis of the formal indictment.

The charges were centered on firstdegree murder, an offense for which no statute of limitations applied.

From the outset, the case was treated not as a reopening of an old mystery, but as a delayed reckoning based on evidence that had finally been assembled into a coherent hole.

In court, the prosecution presented a consolidated body of evidence.

This included the results of chemical analysis establishing a shared origin between the pesticide recovered from the aircraft and the canister, forensic identification of a fingerprint preserved on the adhesive tape sealing the damaged lid and financial records documenting the theft of grain, the forged debt claim, and the rapid growth of Clarence Reed’s assets following Arthur Vance’s disappearance.

Together, these elements demonstrated motive, method, and direct physical linkage to the source of the poison.

The defense focused on the absence of eyewitnesses and the length of time that had passed since the events in question.

They argued that the case relied on circumstantial evidence and that memories and materials could not be considered reliable after so many years.

They suggested that agricultural chemicals were common and that financial success alone did not prove criminal intent.

The defense attempted to frame the evidence as a collection of unrelated facts rather than a unified narrative.

The court rejected that characterization.

The prosecution emphasized that the strength of the case lay not in any single piece of evidence, but in the way each element reinforced the others.

Financial motive explained why the crime occurred.

Access to the aircraft explained how it could be carried out.

Chemical analysis established the method.

Forensic findings tied the method to the defendant.

Taken together, these components formed a closed and logically consistent system that left little room for alternative explanations.

Clarence Reed maintained his position throughout the trial.

He did not admit guilt and avoided substantive comment on the charges.

His silence was not treated as a mitigating factor.

The court noted that the case did not depend on a confession and that the absence of cooperation did not weaken the evidentiary foundation presented by the prosecution.

After reviewing the evidence, the jury found Clarence Reed guilty of first-degree murder.

The verdict reflected the conclusion that Arthur Vance’s death had been the result of a deliberate and premeditated act rather than an accident or unforeseeable event.

Reed was sentenced to life imprisonment.

Although the economic offenses related to grain theft and financial fraud were not charged separately due to the expiration of applicable limitation periods, the court formally recognized them as proof of motive and benefit derived from the crime.

The civil consequences were addressed separately.

The court considered the wrongful death claim brought by Arthur Vance’s family and determined that Reed’s actions had caused direct financial harm.

A judgment was entered requiring him to pay compensation in the amount of $950,000.

This ruling acknowledged not only the loss of life, but also the economic damage sustained by the family over the years following Vance’s disappearance.

The judgment required Clarence Reed to satisfy the awarded sum through the liquidation of available assets, including business holdings and agricultural equipment acquired after 1983.

Courtappointed administrators oversaw the valuation and sale of property to ensure compliance with the ruling.

Payments were directed to Arthur Vance’s family.

While the compensation could not undo the damage caused, it formally acknowledged the material harm sustained by the family and marked the final legal consequence stemming from the crime.

For Arthur Vance’s relatives, the verdict marked the end of a prolonged period of uncertainty.

More than 15 years after he vanished, the legal process provided a definitive explanation for what had happened.

In 2000, Vance was laid to rest with honors, closing a chapter that had remained unresolved for much of the family’s lives.

The case became an example of how even carefully concealed crimes can eventually be uncovered.

What had once appeared to be an inexplicable disappearance over the Bayou Makin was transformed into a documented account of planning, execution, and consequence.

Time had delayed justice, but it had not erased the evidence.

News

Ilhan Omar ‘PLANS TO FLEE’…. as FBI Questions $30 MILLION NET WORTH

So, while Bavino is cracking down in Minnesota, House Republicans turning the heat up on Ilhan Omar. They want to…

FBI & ICE Raid Walz & Mayor’s Properties In Minnesota LINKED To Somali Fentanyl Network

IC and the FBI move on Minnesota, touching the offices of Governor Tim Walls and the state’s biggest mayors as…

FBI RAIDS Massive LA Taxi Empire – You Won’t Believe What They Found Inside!

On a Tuesday morning, the dispatch radios in hundreds of Los Angeles taxi cabs suddenly stopped playing route assignments. Instead,…

Brandon Frugal Finally Revealed What Forced Production to Halt in Season 7 of Skinwalker Ranch….

The Secret of Skinwalker Ranch became History Channel’s biggest hit. Six successful seasons documenting the unknown with real science and…

1 MINUTE AGO: What FBI Found In Hulk Hogan’s Mansion Will Leave You Shocked….

The FBI didn’t plan to walk into a media firestorm, but the moment agents stepped into Hulk Hogan’s Clearwater mansion,…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage… It started like any other evening…

End of content

No more pages to load