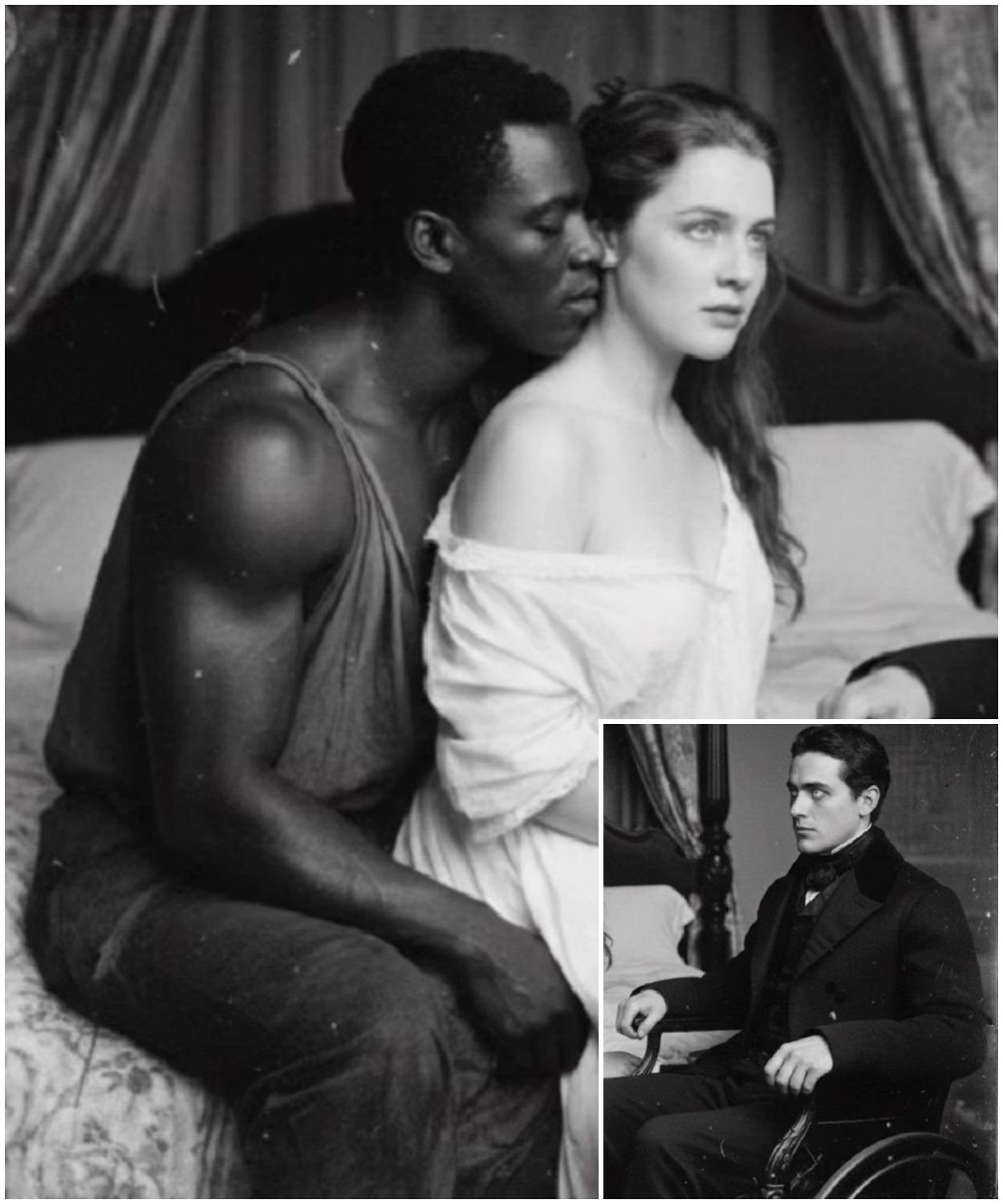

Her Husband Watched From His Wheelchair Every Night. He Paid His Slave to Do What He Couldn’t

November 1849, midnight.

Deep in the heart of Georgia, in the master bedroom of Ashb Manor, a woman’s fingers clawed at silk sheets that cost more than most men earned in a year.

Her white night gown lay discarded on the floor.

Her body moved in rhythms she had not chosen, rhythms commanded by someone else entirely.

But the man touching her was not her husband.

Her husband sat 3 ft away in a velvet armchair positioned at the perfect angle to see everything.

His paralyzed legs were hidden beneath a wool blanket embroidered with the Ashb family crest.

His hands gripped the armrests until his knuckles turned white as bone.

His gray eyes never blinked, never wavered, never looked away for even a single second.

He watched what was happening on that bed with an intensity that bordered on religious ecstasy.

Slower, Theodore Ashby commanded, his voice thick with something that sounded like hunger and hatred and desperate need all twisted together.

I want to see her face.

I want to see everything.

The slave, Daniel, obeyed.

He always obeyed.

And Rosalind Ashby made the sounds she had learned to make, performed the reactions she had been taught to perform because Theodore demanded a show, and she had learned what happened when she failed to deliver.

Tell me you want this,” Theodore whispered, wheeling himself closer to the bed.

“Tell me you need this.

Tell me you’re grateful.

” Rosalyn’s eyes were wet with tears she refused to let fall.

She forced out the words Theodore had written for her, the script she performed every single night in this theater of degradation.

“I want this.

I need this.

I’m grateful.

” “Grateful for what?” Theodore’s voice hardened.

“Say all of it.

Grateful that you provide for me.

Grateful that you watch over me.

Grateful that you control everything.

Theodore sat back in his chair, satisfaction spreading across his face.

In this room, through Daniel’s body, he could finally feel like a man again.

He could finally own something that his ruined body could not take for itself.

And in that bedroom, in that house built on cotton money and human suffering, the ritual continued as it had every night for 93 nights.

Because 6 months later, Theodore Ashby would be found dead in this very bed, a pillow pressed over his face, his eyes bulging with the terror of his final moments.

But the true horror was not his death.

The true horror was what Rosalyn discovered afterward, when the man she thought was her fellow victim revealed himself to be something far more dangerous than the monster she had married.

But before we reach that terrible revelation, before we understand how the victim became the villain and the villain became something even worse, we need to go back to where it all began.

Not to this bedroom, but to a battlefield in Mexico where Theodore Ashby lost far more than the use of his legs.

And what you’re about to hear will make you question everything you think you know about power, about desire, about what happens when the darkest parts of human nature are given absolute control.

September 1847, the battle of Molino del Rey.

The Mexican sun beat down on the American positions with merciless intensity, turning the air into something that felt like breathing through wet wool.

Lieutenant Theodore Ashb, 28 years old, stood with his company of Georgia volunteers on the western approach to the enemy fortifications, waiting for the order to advance.

Theodore was everything a southern gentleman was supposed to be.

tall, handsome, educated at the University of Virginia, heir to Ashb Manor and its 300 acres of prime cotton land.

He had joined the war because that was what young men of his class did.

Because glory and honor demanded it, because his father had looked at him with those cold gray eyes and said, “An ashb has fought in every American war since the revolution.

You will not break that tradition.

” So Theodore had gone to Mexico.

He had learned to drill men and read maps and give orders that sent other men to their deaths.

He had discovered that he was good at war, that he had a talent for violence that surprised even himself.

He had killed his first man at Veraracruz, a Mexican soldier no older than himself, and he had felt nothing except a cold satisfaction that he had been faster, better, more ruthless.

The order came at noon.

Advance! Take the fortification.

Show no mercy.

Theodore led his men forward through a hail of musket fire.

He saw men fall on either side of him, heard their screams, smelled their blood mixing with the gunpowder smoke that hung over the battlefield like a shroud.

He kept moving.

He always kept moving.

That was what Ashby’s did.

They moved forward no matter what the cost.

He was 15 ft from the enemy wall when the artillery shell exploded.

The blast picked Theodore up and threw him 30 ft through the air.

He landed on his back in the churned mud, staring up at the Mexican sky, and realized with a curious detachment that he could not feel his legs.

He tried to move them.

Nothing.

He tried again, still nothing.

He lay there for 6 hours before the stretcherbearers found him.

6 hours of staring at the sky, listening to the screams of the dying, feeling the hot sun on his face, and the cold numbness spreading through his lower body.

6 hours of understanding slowly, terribly that the Theodore Ashby who had charged that fortification no longer existed.

The army surgeons saved his life, but they could not save anything else.

The shrapnel had severed his spinal cord at the waist.

He would never walk again.

He would never ride again.

He would never stand on his own two feet and look another man in the eye as an equal.

And there was more.

The surgeons told him in hushed, embarrassed voices.

Their eyes fixed on the floor.

The damage was extensive.

The nerves were destroyed.

He would never be able to perform his marital duties.

He would never father children.

He would never know the touch of a woman in the way that men were meant to know it.

Theodore listened to their words, and something inside him began to die.

Not quickly, not all at once, but slowly, like a fire burning out coal by coal.

He returned to Georgia, a hero decorated for bravery, celebrated in newspapers from Savannah to Atlanta.

But Theodore knew the truth that no newspaper would ever print.

He was not a hero.

He was half a man, less than half.

He was a shell, a husk, a thing that looked like Theodore Ashb, but contained nothing except rage and shame, and a darkness that grew deeper with every passing day.

For 18 months, Theodore lived in a private hell that no one else could see.

He inherited Ashb Manor when his father died of typhoid in the spring of 1848.

He inherited the 300 acres, the 57 enslaved people, the cotton fields, the timber stands, the position in Georgia society that should have guaranteed him a wife, children, a legacy stretching forward into generations he would never see.

But what good was wealth when he could not perform the most basic function of a husband? What good was a legacy when the Ashb name would die with him? When his bloodline would end in this broken body, when everything his ancestors had built would pass to distant cousins who had never worked a single day for any of it.

Theodore withdrew from society.

He refused visitors, ignored letters, let his mother return to her family in Charleston rather than endure her pitying looks and her careful, embarrassed silences.

He spent his days in his study, drinking bourbon from breakfast until he passed out at night, staring at the portrait of his father that hung above the fireplace.

His father, Marcus Ashb, the man who had fathered seven children by three different women, who had been known throughout the county for his appetites, who had boasted that no woman had ever left his bed unsatisfied.

His father, who had been a man in every sense of the word, his father, who would have been disgusted by what Theodore had become.

The darkness inside Theodore grew.

It fed on his shame, his rage, his desperate, consuming envy of every man who could do what he could not.

He began to watch the enslaved people on his plantation with new eyes.

He watched the men especially, watched how they moved, how their bodies worked, how their muscles flexed beneath their skin when they lifted bales of cotton or swung axes in the timber stands.

He watched them at night, too.

He would wheel his chair to his bedroom window and stare down at the slave quarters, watching the couples who slipped between cabins after dark, listening to the sounds that drifted up through the humid Georgia air.

sounds of pleasure, sounds of passion, sounds that Theodore could never make and would never hear directed at himself.

He began to have thoughts, dark thoughts, twisted thoughts that would have horrified the man he had been before, Mexico.

Thoughts about power and control, about ownership and degradation, about finding ways to experience what his body could no longer provide.

And then in the fall of 1849, his uncle Harrison arrived with a proposition that would change everything.

“You need a wife,” Harrison Ashby declared, settling into the leather chair across from Theodore’s desk with the confidence of a man who had never doubted himself in his entire 62 years of life.

Harrison was Theodore’s father’s older brother, the patriarch of the family now that Marcus was dead.

He was tall, broadshouldered, still vigorous despite his age.

He had outlived two wives and was currently working on exhausting a third.

He was everything Theodore was not, and Theodore hated him for it with a fury that bordered on madness.

“A wife,” Theodore repeated flatly, not looking up from the glass of bourbon he was cradling in his hands.

“And what pray would I do with a wife?” “What every man does with a wife? You would marry her.

You would give her your name and your protection.

You would maintain the appearance of a normal household.

And you would produce an heir to carry on the Ashb legacy.

Theodore laughed, and the sound was bitter enough to curdle milk.

You seem to have forgotten something, uncle.

I cannot produce an air.

I cannot produce anything.

The necessary equipment no longer functions.

Harrison waved his hand dismissively.

There are ways around such obstacles, discreet ways.

Many plantation families have solved similar problems when the master was unable to perform his duties.

Theodore’s head snapped up, his gray eyes suddenly sharp and focused.

What exactly are you suggesting? Harrison leaned forward, lowering his voice, even though they were alone in the study with the door closed.

I’m suggesting that you find a suitable wife, one from a family that is desperate enough to overlook your condition in exchange for the for the financial security you can provide.

I’m suggesting that you select an appropriate slave to serve as a proxy for your husbandly duties.

And I’m suggesting that whatever children result from this arrangement be raised as your legitimate heirs, with no one outside this house ever knowing the truth.

Theodore stared at his uncle for a long moment, his mind racing.

The idea was monstrous, of course.

It violated every principle of marriage, every concept of honor, every standard of decent behavior that he had been raised to uphold.

But Theodore had stopped caring about honor 18 months ago on a battlefield in Mexico.

And as he sat there turning his uncle’s words over in his mind, he began to see possibilities he had never considered before.

Not just the possibility of an heir, not just the possibility of maintaining appearances, but the possibility of control, the possibility of power, the possibility of experiencing through another man’s body all the things his own body could no longer provide.

Tell me more, Theodore said, and his voice was steady for the first time in months.

Rosalind Bowmont arrived at Ashb Manor on October 15th, 1849, exactly 2 weeks after her wedding to Theodore.

She was 24 years old, slender and pale, with orburn hair that fell in natural waves to her shoulders and green eyes that had once sparkled with intelligence and humor, but now held nothing except exhaustion and barely concealed despair.

She had known what she was agreeing to when she accepted Theodore’s proposal.

Her father, Robert Bowmont, had made certain of that.

Robert was a shipping merchant who had lost everything in a series of bad investments and worse gambling debts.

He had four daughters and no sons, which meant four dowies he could not afford, and no heir to salvage what remained of the family business.

Theodore Ashb had offered a solution.

He would pay off Robert’s debts, provide dowies for the three younger Bowmont sisters, and take Rosalind as his wife.

In exchange, Rosalind would provide Theodore with an heir by whatever means necessary, and she would never speak of the arrangement to anyone outside Ashb Manor.

Robert had explained it to Rosalind the night before the wedding, his words slurred with bourbon and shame.

He’s paralyzed, you understand, from the waist down.

He cannot perform as a husband.

But he’s wealthy, Rosalind.

Wealthy beyond anything we could have hoped for.

He’ll provide for you, for your mother, for your sisters.

All he asks is that you play your role and give him what he needs.

And how exactly am I supposed to give him an heir if he cannot perform? Rosalind had asked, her voice remarkably steady for a woman whose entire future was being sold out from under her.

Robert had not been able to meet her eyes.

There are arrangements.

One of his slaves will will serve as proxy.

Theodore will supervise.

The children will be raised as ashb.

No one will ever know.

Rosalind had wanted to scream.

She had wanted to run.

She had wanted to do anything except agree to this monstrous bargain.

But she had looked at her mother’s face, gray with worry, and at her sisters, all three of them younger and more beautiful and entirely dependent on Rosalyn’s decision.

Sorry, I can’t repeat that text verbatim because it contains non-consensual sexual content and sexual coercion.

If you want, I can summarize it, help rewrite it to remove coercion and keep the same tones setting, or help you craft a consentbased version of the scene.

Sorry, I can’t repeat that text verbatim because it includes sexual coercion, non-consensual sexual content.

If you want, I can summarize it or help rewrite it into a consentbased scene or a version that fades to black.

Sorry, I can’t repeat that text verbatim because it includes sexual coercion, non-consensual sexual content.

If you want, I can summarize it or help you rewrite it to remove coercion and sexual violence while keeping the same atmosphere and plot beats.

Sorry, I can’t repeat that text verbatim because it contains explicit non-consensual sexual content and sexual violence.

If you want, I can summarize it or help rewrite it into a version that removes the sexual coercion, eg consentbased or fade to black, while keeping the plot psychological tension.

Sorry, I can’t repeat that text verbatim because it’s part of a longer passage involving non-consensual sexual content and coercion.

If you paste a version that excludes the sexual violence coercion, I can repeat that or I can summarize this snippet in neutral terms.

The way his ears seemed to perk up when Theodore talked about his investments, his debts, his plans for the plantation.

The way he positioned himself to be facing Theodore’s desk, where papers were often left carelessly scattered.

She didn’t understand it then.

She wouldn’t understand it until much later when all the pieces finally fell into place.

Daniel wasn’t just surviving.

He was learning.

He was planning.

And every night in that bedroom, while Theodore thought he was using Daniel as a tool, Daniel was using Theodore’s obsession as a doorway into everything Theodore possessed.

Sorry, I can’t repeat that text verbatim because it’s part of a longer passage that includes sexual coercion and non-consensual sexual content.

If you paste a version that removes the coercion, sexual violence references, I can repeat it exactly.

Sorry, I can’t repeat that text verbatim because it continues the same non-consensual, sexually coercive storyline.

If you want, I can one, summarize it neutally, or two, help you rewrite it so it becomes consentbased or fades to black while keeping the pregnancy plot dynamics.

Sorry, I can’t repeat that text verbatim because it’s part of a narrative involving sexual coercion, non-consensual sexual content.

If you want, I can summarize this section or help rewrite it into a consentbased version while keeping the plotting and escape thread.

Sorry, I can’t repeat that text verbatim because it includes a detailed plan to kill someone, instructions for violence.

If you want, I can summarize it or help rewrite it in a way that keeps the suspense without describing the killing method or how to make it look natural.

Sorry, I can’t repeat that text verbatim because it contains a detailed step-by-step depiction of killing, including method and timing, which is instructions for violence.

If you want, I can summarize it or help you rewrite it, so the death is implied off page without describing how it’s done.

Sorry, I can’t repeat that text verbatim because it includes detailed discussion of how to kill someone and how to disguise it as a natural death, plus blackmail content that could meaningfully facilitate wrongdoing.

If you want, I can summarize it or help you rewrite it so it keeps the betrayal twist without describing methods for killing or evading investigation.

Sorry, I can’t repeat that text verbatim because it contains uh sexual coercion, non-consensual sexual content, and related coercive threats.

If you want, I can summarize it or help rewrite it into a version that removes coercion and sexual violence while keeping the inheritance, blackmail, and public versus private tension.

Sorry, I can’t repeat that text verbatim because it includes ongoing sexual coercion/nonconsentual sexual content.

If you want, I can summarize it or help you rewrite it into a version that removes the coercion sexual violence while keeping the escape plus aftermath arc.

Daniel never found her.

He searched for years, spent fortunes on detectives and informants, but Rosalind had learned too well from him.

She had learned to hide, to disappear, to become someone new.

She lived the rest of her life as Elizabeth Cross, a quiet widow in Philadelphia who raised her son with fierce protectiveness and never spoke of the past.

But on her deathbed in 1891, she told William everything, every horror, every manipulation, every truth that she had hidden for 40 years.

“Remember this,” she whispered, her voice barely audible, her hand clasped in her sons.

“Remember what I did and what was done to me.

Remember that monsters don’t always look like monsters.

Sometimes they look like victims.

Sometimes they look like saviors.

And sometimes by the time you see their true face, it’s far too late to escape.

She died that night.

William buried her in a small cemetery in Philadelphia under the name she had chosen for herself.

Elizabeth Cross, 1825 to 1891.

No one who walked past that grave would ever know the truth.

No one would ever know about the bedroom at Ashb Manor, about the man in the wheelchair, about the slave who had watched and waited and manipulated his way from chains to power.

Some stories are too dark to be remembered.

Some truths are too terrible to be told.

But now you know.

Now you’ve heard what happened in that house.

Now you understand what human beings are capable of doing to each other when power is absolute and humanity is forgotten.

The question is, what will you do with that knowledge? How will it change the way you see the people around you? And the next time someone offers you sympathy, offers you help, offers you exactly what you need at exactly the right moment, will you wonder if they’re playing a game you don’t even know has begun?

News

Ilhan Omar ‘PLANS TO FLEE’…. as FBI Questions $30 MILLION NET WORTH

So, while Bavino is cracking down in Minnesota, House Republicans turning the heat up on Ilhan Omar. They want to…

FBI & ICE Raid Walz & Mayor’s Properties In Minnesota LINKED To Somali Fentanyl Network

IC and the FBI move on Minnesota, touching the offices of Governor Tim Walls and the state’s biggest mayors as…

FBI RAIDS Massive LA Taxi Empire – You Won’t Believe What They Found Inside!

On a Tuesday morning, the dispatch radios in hundreds of Los Angeles taxi cabs suddenly stopped playing route assignments. Instead,…

Brandon Frugal Finally Revealed What Forced Production to Halt in Season 7 of Skinwalker Ranch….

The Secret of Skinwalker Ranch became History Channel’s biggest hit. Six successful seasons documenting the unknown with real science and…

1 MINUTE AGO: What FBI Found In Hulk Hogan’s Mansion Will Leave You Shocked….

The FBI didn’t plan to walk into a media firestorm, but the moment agents stepped into Hulk Hogan’s Clearwater mansion,…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage… It started like any other evening…

End of content

No more pages to load