In May of 2013, 30-year-old hiker Mark Blake set out on a lonely hike in Yoseite National Park, California.

He was to return in 3 days, 4 years later.

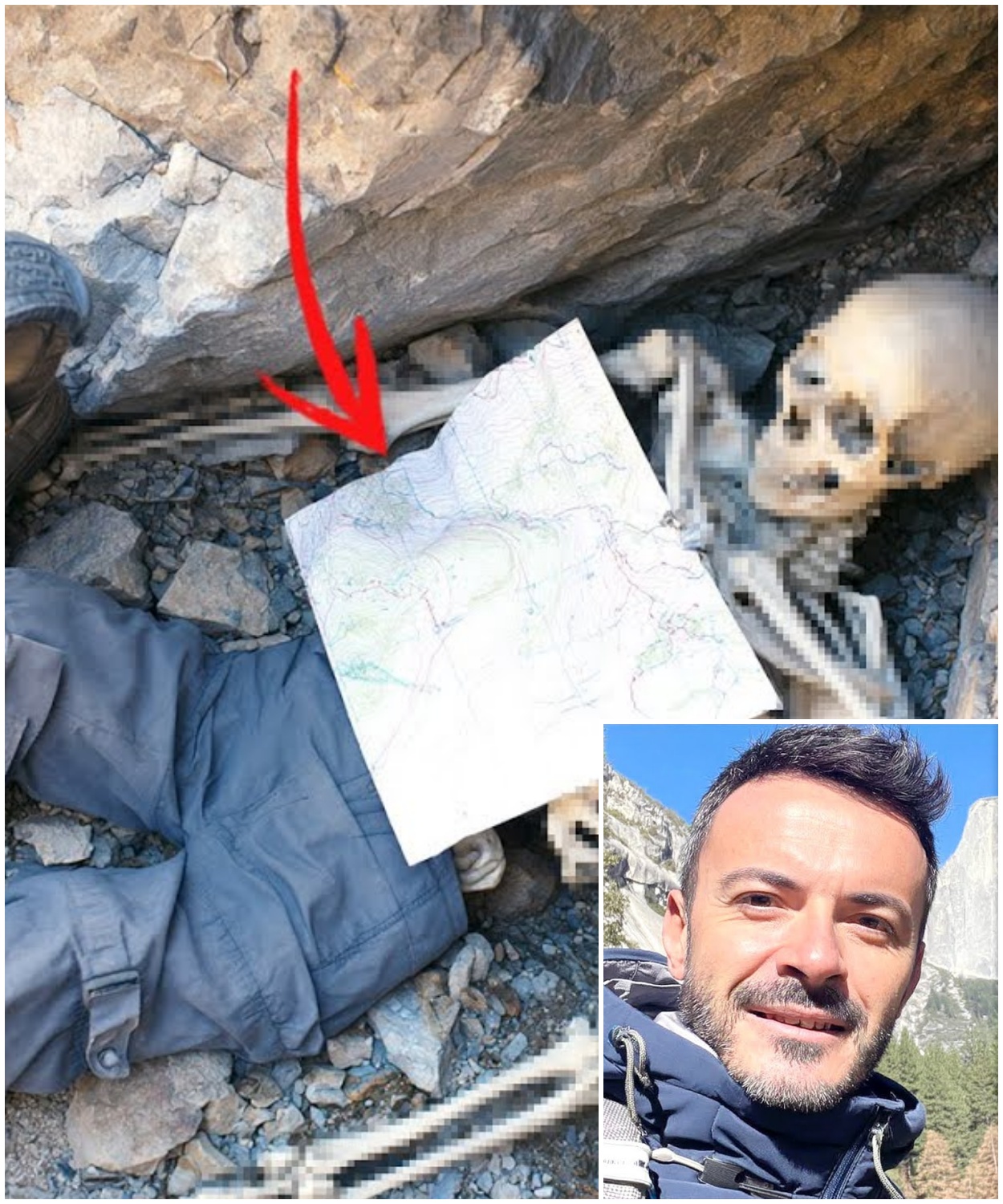

And when a group of climbers stumbled upon the body of a man in Lee Vining Gorge with an old map of Yoseite pinned to his chest with a large pin, it became clear that his death hit a route that led not only through the mountains but also into the depths of another man’s crime.

Mark Blake arrived in Yoseite National Park early in the morning.

He traveled more than 200 m from San Jose, made a brief stop at a gas station near the village of Oakhurst, and passed the checkpoint at the park’s eastern entrance at about 7 in the morning.

His itinerary was registered as a 3-day hike along the eastern spur of the Clark Range, returning through Lee Vining Gorge.

At the visitor center, he left his details and briefly described his travel plan.

According to Ranger Maria Hernandez, the man was confident, well-versed in the area, and had all the necessary equipment.

She recalled that he asked about old routes that were not marked on modern maps and wondered if the approaches to the old tunnels in the Clark Range area were still intact.

Blake worked in the field of cgraphy.

A few weeks before the trip, he bought an old map of Yoseite from a used bookstore published in the late ‘7s.

In the margins of the map, an unknown hand had written, “The true heart of the park, SL, 1978.

” The coordinates next to it did not correspond to any known tourist routes.

Before leaving, he showed the map to his girlfriend, Sophia.

In private correspondence, which was later seized by the police, she wrote, “You just want to check if that inscription is real.

Promise me you won’t go deeper yourself.

” Blake replied, “It’s just a small expedition.

I want to see a place where maybe a hundred years ago someone left a sign.

” According to testimony later received from park staff, the weather that week was calm.

The daytime temperature remained at 70° F while the nighttime temperature dropped to 45.

There was no precipitation and the snow on the peaks melted quickly, making the trails slippery but passable.

At about 9:00 in the morning on May 17th, he last contacted via satellite messenger.

The message addressed to Sophia sounded calm.

The sun is rising.

I’m on the ridge now.

The view is incredible.

I found the path that was on the map.

It’s real and leads deeper into the Lee Vining Gorge.

Everything is fine.

I may be out of coverage today.

I’ll be back tomorrow as promised.

Love you.

The satellite tracking system recorded his coordinates, a point nearly two miles from the nearest official trail.

This area was considered difficult even for experienced hikers.

Steep, rocky slopes, unstable ground, deep fissurers.

After that, no signals were received.

The visitor cent’s log book states that his route was supposed to end on May 19th by 6 in the evening.

When this did not happen, Sophia reported him missing.

At the time, no one knew that the point from which Blake sent his last message would be the key to one of the most mysterious cases in Yoseite in decades.

The search operation began on the morning of May 19th, 2013.

At first, it looked like a routine procedure standard for a park where dozens of tourists disappear every year.

But a few days later, it became clear that this case would be different.

National Park Service rangers, volunteers, and dog handlers were involved in the search.

A base camp was set up in the two Alumni Valley from where groups set off with the coordinates received from Blake’s satellite messenger.

On the fifth day, a helicopter with a thermal imager capable of detecting even faint sources of heat under the tree canopy joined the search.

But the equipment did not help.

The heat spots that initially appeared on the screen turned out to be just animals, coyotes, and deer.

The Clark Range area is known for its difficulty.

Narrow passages between granite walls, deep creasses, chaotic loose slopes where the stone crumbles right underfoot.

Experienced rescuers knew that every meter of this terrain could hide a trap.

The wind here changes suddenly.

Sound waves are distorted and even a person’s voice from a few yards away becomes unintelligible.

In such conditions, it is easy to get lost and almost impossible to survive.

On the eighth day, one of the search teams, rangers from the East Meadow unit, reported a find.

They came across a small area at an altitude of over 9,000 ft where a tent was standing.

The site overlooked Lee Vining Gorge, but was protected from the wind by a rockout cropping.

Everything looked surprisingly orderly.

The tent was stretched out flat, the zipper was zipped up, and there was a sleeping bag, and a backpack inside.

Food, a first aid kit, a compass, a supply of water.

Everything was there, untouched.

There were no signs of haste, struggle, or panic.

Photos of the camp taken by the rangers were later attached to the case.

They showed boots lying near the entrance placed side by side with their toes facing forward as is usually done before going to bed or taking a short rest.

On a stone near the tent was an aluminum mug with coffee residue.

It was standing in the open air as if the owner had left for just a minute.

Under the same stone, the rescuers found a Garmin enriched satellite messenger.

The device was turned on and the battery was almost full.

The message log contained the same calm message he had sent to Sophia on the morning of May 17th.

After that, nothing happened.

No SOS button was pressed.

No attempts to reconnect were recorded.

For investigators, this was the first and foremost paradox.

If he was in trouble, why didn’t he use the device? If he was just out for a walk, why did he leave it in plain sight, almost deliberately? The version of an animal attack was ruled out.

There were no traces of blood and his belongings were not scattered.

At the campsite, experts noted another detail.

There were no clear footprints in the soil.

The hard dust, which should have recorded every step, was smooth, as if it had been deliberately smoothed.

The rangers assumed that gusts of wind could have erased the tracks, but according to meteorologists, the weather was almost calm that day.

A few days later, the search teams descended lower in the direction of the gorge.

They worked systematically, square by square.

They checked every ravine, every crack, even the cavities between rock fragments, but they never found a single hint of a person.

By the end of the second week, the volunteers were running out of energy.

People who had started with hope returned silent and empty-handed.

Only senior Ranger Maria Hernandez continued to reread the reports and insisted that Mark could not have simply gotten lost.

In her notes, she wrote, “The camp did not look abandoned, but left behind, as if its owner knew he would not return.

” A month later, the operation was officially completed.

An entry appeared in the database.

Mark Blake, missing.

For the police, it was another ordinary case among hundreds of similar ones.

For his family, it was the end of any certainty.

Sophia continued to write to his email, hoping that he would respond someday.

Her messages remained unread, but she did not delete them.

Each one became a letter to the void.

His father, a former military officer, had personally traveled to Yoseite and tried to walk the same route several times.

He would stand at the campsite, look down into the deep gorge where the river was rushing, and repeat the same thing.

Something is wrong here.

That’s how the first shadow of suspicion appeared.

That Mark did not die by accident and did not get lost.

That he had been taken from there.

But without proof, it was just a feeling.

The forest was silent.

The camp was silent, too.

September of 2017, 4 years after the disappearance, Mark Blake’s case had long since lost its active status.

In the database, it was dryly marked as missing, search unsuccessful.

For the Rangers, it was just another one of hundreds of stories that ended in silence.

But the Yoseite Mountain Range does not give up its secrets easily, only when it chooses to.

On September 15th, a group of three climbers from Sacramento were climbing a challenging route known among experienced climbers as the Silver Ridge.

It was a remote area of the Lee Vining Gorge, where there are no official trails and hardly any tourists set foot.

At an altitude of more than 9,000 ft, they decided to make a halt in a narrow stone crevice leading down between two granite walls.

One of them, an experienced guide named Jonathan Casease, noticed a strange shine down below.

At first, he thought it was a piece of metal or the remains of equipment from one of the previous groups.

But as he crawled deeper, the flashlights rays illuminated a piece of fabric that seemed to be part of a jacket.

Under it was a human body, half covered with small stones.

It was lying face up, wedged between the slabs.

The fabric on the chest was stuck together by time, but a metal object was clearly visible through it, a large climbing pin with what looked like paper pinned to the body.

The case stopped.

He immediately realized that this was a recent burial, but the look of what was hanging from the chest was too unusual.

When the rescuers retrieved the body, all doubts disappeared.

They had found Mark Blake, who had disappeared 4 years earlier.

And it was what he was carrying that turned the story of his disappearance upside down.

Pinned to his chest, pierced through his clothes and skin, was an old topographic map of Yoseite.

Its edges were darkened and frayed, but the markings remained clear.

A route was drawn on it with a black marker.

A line starting at the point where the body was found and stretching far to the southwest towards a mountainous area designated as the wild pool of paradise.

The condition of the body surprised experts.

Despite 4 years, it had not turned into a skeleton.

The cold, dry air of the gorge, the lack of moisture and insects slowed down the decomposition process.

The face was disfigured, but the clothes remained almost intact.

A blue jacket, dark gray pants, and hiking boots.

These were the items later confirmed by Sophia Brener, his girlfriend.

When investigators arrived at the scene, it took them several hours to remove the body from the creasse.

Everything around was carefully photographed and labeled.

There were no signs of a struggle or drag on the stones, no bootprints, no burnt remains of a fire.

The body was lying there as if someone had put it there with care and left it.

The investigation was led by District Detective Liam Walsh.

A former military officer, he had served with the Manmmont County Criminal Division for more than a decade and had experience in cases involving national parks.

He was interested not only in the death, but also in the map.

It looked like a message precise, thoughtful, not accidental.

The map was removed from the body with the utmost care.

The analysis showed that it was indeed old, a late70s edition, but the black line that led further down was drawn recently.

The ink was not faded, and the paper had clear marks from a modern type of marker.

This meant that the map had been touched after Blake’s death.

The route led to an area that did not have an official name on any modern map, only a conventional one, Paradise Pool.

This place had long been considered inaccessible and rangers rarely visited it because of the dense thicket and lack of trails.

It was there that Detective Walsh decided to go with his team.

The journey took 2 days.

Their expedition traveled on foot using GPS navigators and drones.

After many hours of trekking, they came across signs of human activity.

Plastic pipes, torn plastic canisters, and pieces of plastic film.

A few hundred yardds down in a deep hollow lay what had once been a marijuana plantation.

It looked abandoned, but not old.

The irrigation system, made of garden hoses, was still intact, and there were fresh shoe marks on the ground.

Some of the fertilizer containers were open as if people had left the place in a hurry.

Forensic experts found several pieces of evidence among the remains of the camp.

In the ground, there were empty shell casings from a 38 caliber rifle.

In a plastic container, fragments of fertilizer bags, which could be used to trace the supply batch, and most importantly, a torn receipt from a gas station in Fresno.

The receipt was badly damaged, but after reconstruction, the date about 2 years ago, and part of the credit card number were visible.

It was an unexpected discovery.

Among the cashonly drug mafia, the appearance of a bank check could mean a mistake that would cost its owner dearly.

For Detective Walsh, everything made sense.

The plantation recently abandoned, the guns, the gear, and the old map pinned to Mark Blake’s chest.

It seemed as if he had accidentally stumbled upon this place back in 2013 and paid for it with his life.

But the question remained, who left the map, and why did it lead exactly here 4 years after his death? Walsh realized that only one thing could provide an answer, the name on that ill- fated check.

Even such a nearly erased piece of evidence could lead him to the people who had destroyed the witness and were trying to erase their own trail in the mountains.

It was from that moment that the investigation began again, not as a case of disappearance, but as a case of premeditated murder.

Yoseite, which had been silent for years, finally spoke up.

Detective Liam Walsh returned to Yoseite 2 weeks after the body was found.

His goal was not just to examine the crime scene, but to walk the entire route marked on the map pinned to Mark Blake’s chest.

Five people went on the expedition.

Two forensic scientists, a topography specialist, and two rangers who knew the area well.

The route began at the edge of the Lee Vining Gorge and stretched towards the southern plateau, where old maps marked an area under the conventional name Wild Pool of Paradise.

There were no official trails there, only chaotic offshoots made by gold miners and smugglers.

The place was considered unsuitable for any activity, too wild even for hunters.

The climb took almost 2 days.

During the day, the temperature rose to 90° F, and at night, it plummeted below 40.

The team moved slowly, stopping every few hours to check their bearings.

Remnants of old wooden poles and parts of plastic pipes showed that water had once been piped here.

On the third day, they came across traces of human activity.

Pieces of film, the remains of plastic containers, and a burnt metal cauldron.

A few hundred yards down, a hollow opened up, almost completely overgrown with bushes.

There, among the weeds and boulders, was the abandoned camp.

The marijuana plantation looked like it had been abandoned recently.

The irrigation system, made of thin rubber hoses, was still intact.

There were water cans, several bags of fertilizer, and empty plastic pots on the ground.

Empty tin cans were lying around the old tent, and cigarette butts were found in the ashes of the extinguished fire, only half burnt.

This meant that the place was left quickly, but without panic, systematically, as if someone knew it was time to disappear.

The forensic experts began their work systematically.

They examined every meter of the territory, took photos, soil samples, and shoe prints.

On several stones, they found 38 caliber rifle shells, the same ones that would later appear in the reports.

There were no prints on the shells, but the corrosion indicated that they had been fired recently, no more than a year ago.

However, the most valuable item was found where no one expected it.

Under a pile of garbage near a burned-out generator, Detective Walsh noticed a piece of paper crumpled and partially charred.

At first glance, it looked like an ordinary check.

But when it was carefully unfolded, it turned out to be a receipt from a gas station in Fresno.

The paper retained some of the inscriptions, the company logo, the time of the transaction, and the last four digits of the credit card.

The receipt was old.

According to experts, it was at least 2 years old, but it was enough to give the police a clue.

Even a single fragment of the card number could help trace the owner through the bank transaction database.

Walsh felt that he had stumbled upon a real connection between the murdered tourist and those who were hiding behind this plantation.

Further inspection revealed several other small items.

a piece of rope with traces of moisture, half a plastic bottle with a fingerprint, and an energy bar wrapper that had expired a year ago.

This meant that people had been working here at least until 2016.

On the wall of the abandoned tent, where the workers had presumably slept, experts found shoe prints of two different sizes.

One of them was much larger, possibly a man’s, and the other was smaller, looking like a teenager’s or a short person’s footprint.

This indicated that not only adult men could have worked in the camp.

All the evidence collected was packed in special containers and transported to a laboratory in Manmmont County.

Detective Walsh stayed another day.

He walked around the devastated hollow, looking at a place that seemed dead, but had a strange air of presence.

In the evening, he wrote in his report, “The place was not left by chance.

People had time and knew when to leave.

They did not run away.

They were hiding.

” The team set out that evening, following the same route as the line on the map found on Blake’s body.

Although it was physically just mountainous terrain, to Walsh, it already looked like a crime scene, a thin thread connecting death in the gorge to the silence of an abandoned plantation.

When he returned to the department, he wrote a detailed report and submitted all the evidence for examination, especially the check.

It was carefully dried, scanned under infrared light, and part of the text became legible.

The name of the gas station, the city of Fresno, and the date, June 2015.

The detective realized that such a small thing could be decisive.

In cases where there are no obvious traces, it is fragments like this.

A piece of paper, a broken thread, a worn out print that sometimes reveal everything.

This receipt was just such a fragment.

A bridge between Mark Blake and the people who tried to erase their presence from the map of Yoseite.

A new stage was beginning for Walsh.

For the first time in 4 years, he had real tangible proof.

and perhaps the first answer to the question of why a traveler who simply wanted to find the heart of the park stumbled upon something he was not meant to see.

Deciphering part of the credit card number from the receipt took several days.

The bank was reluctant to cooperate, citing confidentiality, but after an official request from the district attorney’s office, they finally got the data.

The card belonged to Jake Torrance, a 34year-old resident of Fresno.

His last name meant nothing to either the police or Detective Walsh.

He lived an ordinary, unremarkable life.

A rented apartment in the suburbs, an old car, and a job as an electrician for a private company that serviced industrial warehouses.

Only a few minor offenses were found in the police database, stealing spare parts when he was young, and administrative arrest for a bar fight.

The last 10 years were clean.

a man who seemed to have left his past behind long ago.

Detective Walsh and his partner visited his home in the southern neighborhood of Fresno.

The small one-story duplex stood among others like it with burntout lawns and old pickup trucks at the gate.

Torrance himself sat on the porch, a thin man with nervous hands, fiddling with a lighter.

His reaction to the police badges was instantaneous.

He tensed but did not try to run away.

The conversation continued calmly until Walsh showed him a photocopy of the receipt found in the wild pool.

Then Torrance’s face changed.

He tried to smile, but it was strained.

“You’ve got to be kidding me,” he muttered.

“I threw those cards away a long time ago.

I have no idea what this place is,” his voice trembled.

Walsh calmly replied that they had found the check next to an illegal plantation in the Yoseite Mountains and asked if he had been there.

After a few minutes of silence, Torrance lowered his head.

His story began to fall apart.

At first, he said he was just passing through the park on his way to visit friends.

Then, when he was reminded of the date of the transaction on the check, June 2015, he admitted that he had indeed been in the mountains.

but just working.

According to him, two years ago, he received a short order to repair a generator and install lighting in a field camp.

He was paid in cash generously without questions or contracts.

The man who ordered the work called himself Greg.

He did not give his last name.

Torrance assumed it was some kind of scientific camp.

He saw several tents, plastic containers, and cables stretching to a water intake, but he didn’t see any weapons, guards, or traces of drugs.

“I swear I didn’t know it was illegal,” he said, ringing his hands.

“They looked like normal workers.

I did my job, spent the night, and left.

Before I left, I stopped at a gas station and got a coffee and a sandwich.

I didn’t even think it could make a difference.

The detectives listened carefully.

They knew that part of the truth was hidden behind the little things.

When Walsh showed him a photo of the card he had found from Mark Blake’s body, Jake looked away.

His hands started to shake again.

Then I heard one of them say something about a tourist who didn’t show up on time, he whispered.

I thought it was just talk.

But maybe it was that man.

Torrance described Greg as a man in his mid-50s with dark hair, a scar over his right eyebrow and a tremor in his left hand.

He said he carried himself confidently but had a cold, blank stare, the type of person who was used to giving orders.

Greg spoke harshly without jokes, smoked constantly, and made sure no one took pictures of the camp.

When Walsh asked if Torrance could recognize the man, he replied, “Yes, if I see him again, no doubt.

” His voice became quieter and he asked for guarantees of protection.

His fear was genuine.

After the interrogation, Torrance was released, leaving him under covert surveillance.

He did not look like a murderer.

There was something else in his eyes.

The panic of a man who realizes that he has become part of someone else’s crime without having done anything consciously.

Walsh wrote in his report, “The witness is unreliable but credible.

His fear is real.

His words are a coincidence that cannot be ignored.

” For the first time in the years of the investigation, the detective had a name, Greg Miller.

A name that could have belonged to the organizer of the plantation or to the man who had attached the map to the traveler’s body.

That evening, Walsh looked through old files from the department’s archives.

Coincidentally, there were several people with that name in the database, but only one had a criminal record for weapons possession and ties to illegal cannabis growers in central California.

But more was needed to be sure.

Jake Torrance left behind not only a story, but a thread.

A thin, fragile, but real thread that leads deeper into a network that began with a map pinned to the chest of a dead hiker.

Walsh realized that he was no longer just investigating a murder.

He was closing in on people who had been hiding among the mountains and forests for years, using nature as a hiding place.

And Greg Miller’s name was the first stone in this hidden chain.

Detective Liam Walsh started with something simple, a police database.

But the name Greg Miller turned up more than a 100 matches across California.

Some of them were ordinary citizens.

Some were ex-offenders and only a handful had ties to illegal marijuana cultivation in areas near Yoseite.

The work was slow.

Each name was checked against old warrants, court cases, and arrest reports.

Finally, after several days of intense scrutiny, the system produced a match.

Gregor Miller, 52 years old, a native of Madera County.

His criminal record includes drug trafficking, assaulting a police officer, and two stints in a penal colony.

His last report, dated three years earlier, stated that he was temporarily inactive.

This wording meant that the person had disappeared from sight, but not necessarily abandoned the case.

Miller’s last known address was in a small town near the southern border of the park.

It was a typical American landscape with dusty roads, packed tourist shops, and motel with faded signs.

When Walsh and his partner arrived, the house was empty.

A shabby trailer stood on a weed-covered lot, and the windows were covered with plywood.

Neighbors reported that Miller had disappeared about a month ago, around the time Mark Blake’s body was found.

One woman, the owner of a nearby campsite, recalled that he had seemed agitated, almost scared lately.

Often at night, he would leave in the direction of the park, returning in the morning.

Sometimes he was seen with a young man named Liam, who worked at a local outdoor equipment store.

The next day, Walsh went there.

The store was typical of small tourist towns.

shelves with compasses, flashlights, canned goods, a poster with a map of the park on the wall.

The salesman, a young man with short blonde hair, was just putting away boxes of new backpacks.

He introduced himself as Liam Cartwright.

He answered the detective’s question about his acquaintance with Miller briefly.

Yes, I do.

He came a few times.

I bought gas cylinders, ropes, and that was it.

His voice sounded even, but his eyes betrayed tension.

Walsh calmly laid out the photos in front of him, an abandoned plantation, a map pinned to Blake’s body.

Then, without saying a word, he pulled out a picture of Mark himself.

Liam’s face changed instantly.

His hands shook.

He looked at the photo for a few seconds, then turned away.

When the detective asked when he last saw Miller, he answered quietly.

about a month ago.

He was strange.

He said there was a trouble that a man had seen something he shouldn’t have seen.

After that, Liam said more.

He helped Miller deliver supplies deep into the park several times.

Fuel, canned food, water cans.

He was paid in cash without explanation.

Greg told him it was for seasonal workers, but forbade him to come near the camp.

The last time he came back, he was pale and silent.

He said only one thing.

It’s over.

If anyone asks, you don’t know me.

2 days after that incident, Miller disappeared.

His trailer was open and a piece of paper with a short note on it was left on the kitchen table.

Don’t tell anyone.

It’s none of your business.

Liam showed the note to Walsh.

The handwriting was firm with sharp slants.

mail.

There was no signature.

All of Greg’s belongings were still there.

Clothes, tools, an old portable radio.

Only his phone and a small suitcase were missing.

The detective recorded all the evidence.

They provided an important detail.

Miller did not run away spontaneously.

He was preparing and probably someone had warned him that Blake’s body had been found.

During the interrogation, Liam looked exhausted.

He was constantly looking around, nervously clutching a water bottle.

His fear did not seem to be pretended.

When Walsh promised him protection, he agreed to cooperate.

He remembered another place where, according to Miller, he could hide out if it gets hot.

It was an old sawmill 10 mi from town, long abandoned after a fire.

It was rumored to be where illegal hunters sometimes spent the night.

In his report, Walsh wrote down, “Miller may be in hiding.

Must be checked immediately.

Danger level is high.

” That evening, he organized an operation.

The team included two federal agents and four local officers.

The location of the sawmill was marked on a map behind an abandoned quarry in the middle of nowhere, where the roads had long been overgrown.

Even the rangers could not get there.

Before leaving, Walsh looked for a long time at a photograph of Mark Blake that had been in his file since day one.

Every detail of that face, an ordinary man who had simply gone into the mountains had a completely different meaning.

Now, what had seemed like an accidental tragedy was turning into part of a larger scheme.

The detective understood Miller might be just the enforcer, but he was the first person to be found alive because then behind him there is someone else.

And if Walsh delayed even a day, that someone would disappear forever.

The operation began at dawn.

The old sawmill that once operated on the outskirts of Yoseite had long since been swallowed up by the trees.

All that remained of the road to it was a narrow track overgrown with moss and weeds.

The wooden structures were dilapidated.

The roof had caved in in several places and the walls were blackened by rain and time.

Nevertheless, a faint light was visible inside, a sign that the place was not completely abandoned.

A group of six officers entered unannounced.

One of them using a thermal imager detected a heat source in the building that had once served as an office.

When the door was kicked in, there was indeed a man inside.

The man did not resist.

He stood up, raised his hands, and said calmly, “You have been traveling a long time.

” That’s how they detained Greg Miller.

He was sleeping on an old sleeping bag with an open can of canned food and a pistol with no bullets next to him.

He looked exhausted, overgrown with deep, dark circles under his eyes.

It seemed that he was not running away.

He was waiting.

During the arrest, he did not resist, did not ask what he was accused of.

He only repeated one thing.

I knew you would come.

On the floor, they found several papers, scraps of newspapers, and an old map of the park with marked areas of the forest.

Everything looked like a person had lived here for a long time, but without a plan.

The first interrogation took place the same day at the local police station.

Miller was nervous, but not aggressive.

When asked about the plantation, he answered immediately.

He did not deny that he ran it.

He said he was a lookout, a mercenary.

He was paid in cash through intermediaries, and his task was to make sure that no one got close to the site.

I didn’t kill that guy, he said, ringing his hands.

I was just guarding him.

But when he saw us, I was ordered to get rid of him.

According to Miller, the real owner was Luke Sims, a man the department already knew from several old drug trafficking cases in central California.

Sims left no trace.

He didn’t sign documents, didn’t keep money in his own accounts, and worked through a chain of proxies.

Plantations and national parks were only part of his business.

Miller received an order from someone at the top, but according to him, he was unable to fulfill it to the end.

“When I saw the guy,” he said, referring to Mark Blake, “I felt sick.

He was young.

He didn’t understand anything.

I thought about my son.

I couldn’t do that.

” He explained that he had ordered his assistant, Jack, to take the body deeper into the woods and hide it.

I thought it would be limited to intimidation, maybe beatings, but no murder.

But the next day, Jack returned silent and said only, “It’s done.

” Miller did not ask.

He felt it was better not to know.

A week later, the plantation received an order to shut down.

Then he realized that the situation was out of control.

When asked about the map, the pinned pins, or any other symbols, Miller just shrugged his shoulders.

I found out about it from you.

I didn’t know he was dead.

I thought he had just been released or moved on.

His words sounded sincere, even though Walsh knew that he was facing an experienced criminal network member who knew how to keep his cool.

But the fear in his voice was real.

Miller was not afraid of prison, but of people who were above him.

During the interrogation, he repeated the name Luke Sims several times.

He said that he controlled not just one plantation, but a whole network that stretched from Northern California to Nevada.

The money from the sale went through fictitious companies, some of it transferred through cryptocurrency.

When Walsh asked how he was contacted, Miller answered through intermediaries.

I never called directly.

All orders were passed on by Jack.

He was on a short leash.

This name came up again in the case.

Jack, an assistant, an enforcer, a shadow.

Miller didn’t know his real name, only that he had a tattoo on his neck of a burning bird and always wore a black baseball cap.

When the conversation turned to Mark Blake, Miller fell silent.

He seemed to have difficulty even saying his name.

He sat looking at the table and only after a few minutes whispered, “I didn’t want him to die.

I just wanted him to disappear.

” They said that if I didn’t, they would do the same to me.

After several hours of interrogation, Walsh stopped the recording.

He realized that this man was not completely lying, but he was not telling the whole truth either.

Greg was a link, not a source.

His story only opened up a new layer.

the name of Luke Sims, which was now becoming the main one in the case.

As Miller was being led out of the room, he stopped in the doorway and said, “If you’re looking for the guy who really did it, don’t look at me.

Look at the guy who’s got everyone on the hook.

” Walsh did not answer.

He had a feeling that this phrase was the key.

Miller, despite his fatigue, did not look defeated.

Rather, he looked doomed, but relieved.

It was as if being caught meant the end of the constant waiting.

After the interrogation, the detective spent a long time reviewing the case file.

He saw a diagram in front of him in the center of Sims below Miller and next to him was the unknown Jack, the one who had carried out the order and disappeared.

It was he who may have pinned the map to the traveler’s chest, but it was impossible to prove it yet.

Now the investigation had to move to another plane.

The hunt had already begun, but the target remained in the shadows.

After Miller’s arrest, the investigation froze.

Detective Walsh had two names.

Luke Sims, an untouchable drug lord from Sacramento, and Jack, an unnamed assistant whose silhouette remained a shadow in all testimony.

Miller’s interrogation report was brief.

Jack Young tattoo of a burning bird on his neck appeared a few months before the incident.

Recommended from above.

Sims was not officially involved in any case.

His business existed through intermediaries, shell companies, frontmen, accounts abroad.

The people who worked with him disappeared or moved.

Every attempt by Walsh to obtain a search warrant was met with a lack of evidence.

But the chance came unexpectedly.

During a raid on a warehouse in Sacramento’s industrial area, police seized several old cell phones that agents believed were used by Sims’s people.

One of the devices was personal, a model without a SIM card, but with an active memory.

The contacts included only a few names, no numbers.

One of them stood out.

J.

When the tech department recovered the deleted data, a number registered to Jacob Ryan, a 26-year-old man from Carson City, Nevada, appeared on the screen.

The former mechanic, now unemployed, had a history of minor offenses: vandalism, illegal possession of weapons.

His name had not appeared in police databases for several years.

Following a tip off from the local police, Ryan was found in a motel on the outskirts of Reno.

A small room with dirty curtains, an open window, and a ticket to Mexico for the next day on the table.

When they knocked on the door, he didn’t try to run away.

He just slowly raised his arms.

There was a printed newspaper on the bed with a story about the discovery of Mark Blake’s body.

During the interrogation, Jacob Ryan was calm.

He answered questions without emotion with short pauses as if he was weighing every word.

“Yes, I worked for Sims,” he said, “but I didn’t want to do it.

” Walsh did not interrupt.

Ryan explained that a few years ago, he found himself in debt.

Through his friends, he was introduced to Sims’s people.

He became a courier, delivering equipment, fuel, and food.

Later, he was involved in mopping up operations when he had to clean up camps or monitor the territory.

On the day Mark Blake arrived at the plantation, Sims gave an order.

Resolve the issue.

This meant eliminating the witness.

Miller, who was supposed to do it, hesitated.

Then Sims sent Ryan in.

“I saw him,” Jack said quietly.

“He didn’t fight.

He just watched me walk up.

I knew what I was doing, but when it was over, I couldn’t leave it alone.

His voice was barely shaking.

According to the protocol, he admitted that he was the one who pinned the map to the dead Blake’s chest.

I found it in his pocket, saw the inscription, and realized it might be the only way to leave a trace.

“I drew a line,” he said.

“One that led to the spot.

I wanted the police to find it.

I wanted someone to finally see what we were doing.

Ryan did not try to justify himself.

He just said he couldn’t go to the police because Sims had everyone under his control.

He had addresses, photos, names.

If I talked, he explained, I would be gone the next day.

Walsh listened without taking notes.

Everything about this case had been confusing from the beginning.

The map, the abandoned plantation, the people who disappeared after every question.

But now everything was falling into place.

Mark Blake had indeed become an accidental witness and his death was the link that finally broke the chain.

A few hours after the interrogation, detectives received an arrest warrant for Luke Sims.

The operation in Sacramento went off without a hitch.

Documents, large amounts of cash, computers with accounting files, and several photographs from the mountainous areas were found in his home.

One of the pictures matched the location where Blake’s body was found.

For Walsh, it was the end of the case, but not a victory.

When he returned to California, the first thing he did was go to see Sophia Brener.

She lived in the same apartment where she used to wait for messages from the mountains.

The detective stood on the doorstep with a thin folder in his hands.

It contained copies of reports, testimonies, and photographs.

He could have said that the killer was caught, that justice had been done.

But the words stuck.

He just held out the folder and spoke softly.

We found him and those who did it.

Sophia was silent.

Then she asked one question.

Did he suffer? Walsh did not answer.

He was not authorized to talk about details.

The report was dry.

Death was instantaneous due to head trauma, but such things do not bring relief.

That evening, he stood by the car for a long time, looking at an old copy of the map of Yoseite, the same one that had been pinned to his body.

There was a bold line of black marker on it, which now led not deep into the forest, but to the names crossed out in the protocol.

The Mark Blake case was officially closed.

But there was a question in Walsh’s mind that he couldn’t put in the report.

How far can a person go when trying to survive? And can one right decision erase previous crimes? There were no answers.

As always in these mountains, the thunder was followed by silence.

as cold as the stone of the gorge where the truth had been lying for four

News

Ilhan Omar ‘PLANS TO FLEE’…. as FBI Questions $30 MILLION NET WORTH

So, while Bavino is cracking down in Minnesota, House Republicans turning the heat up on Ilhan Omar. They want to…

FBI & ICE Raid Walz & Mayor’s Properties In Minnesota LINKED To Somali Fentanyl Network

IC and the FBI move on Minnesota, touching the offices of Governor Tim Walls and the state’s biggest mayors as…

FBI RAIDS Massive LA Taxi Empire – You Won’t Believe What They Found Inside!

On a Tuesday morning, the dispatch radios in hundreds of Los Angeles taxi cabs suddenly stopped playing route assignments. Instead,…

Brandon Frugal Finally Revealed What Forced Production to Halt in Season 7 of Skinwalker Ranch….

The Secret of Skinwalker Ranch became History Channel’s biggest hit. Six successful seasons documenting the unknown with real science and…

1 MINUTE AGO: What FBI Found In Hulk Hogan’s Mansion Will Leave You Shocked….

The FBI didn’t plan to walk into a media firestorm, but the moment agents stepped into Hulk Hogan’s Clearwater mansion,…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage… It started like any other evening…

End of content

No more pages to load