On August 14, 2010, 24year-old aspiring architect Millie Lindsay disappeared without a trace in the midst of the hot rocks of the Tanto National Forest.

A large-scale search left no clues except for one lost item at the bottom of a dried up stream, her bandana.

7 years have passed.

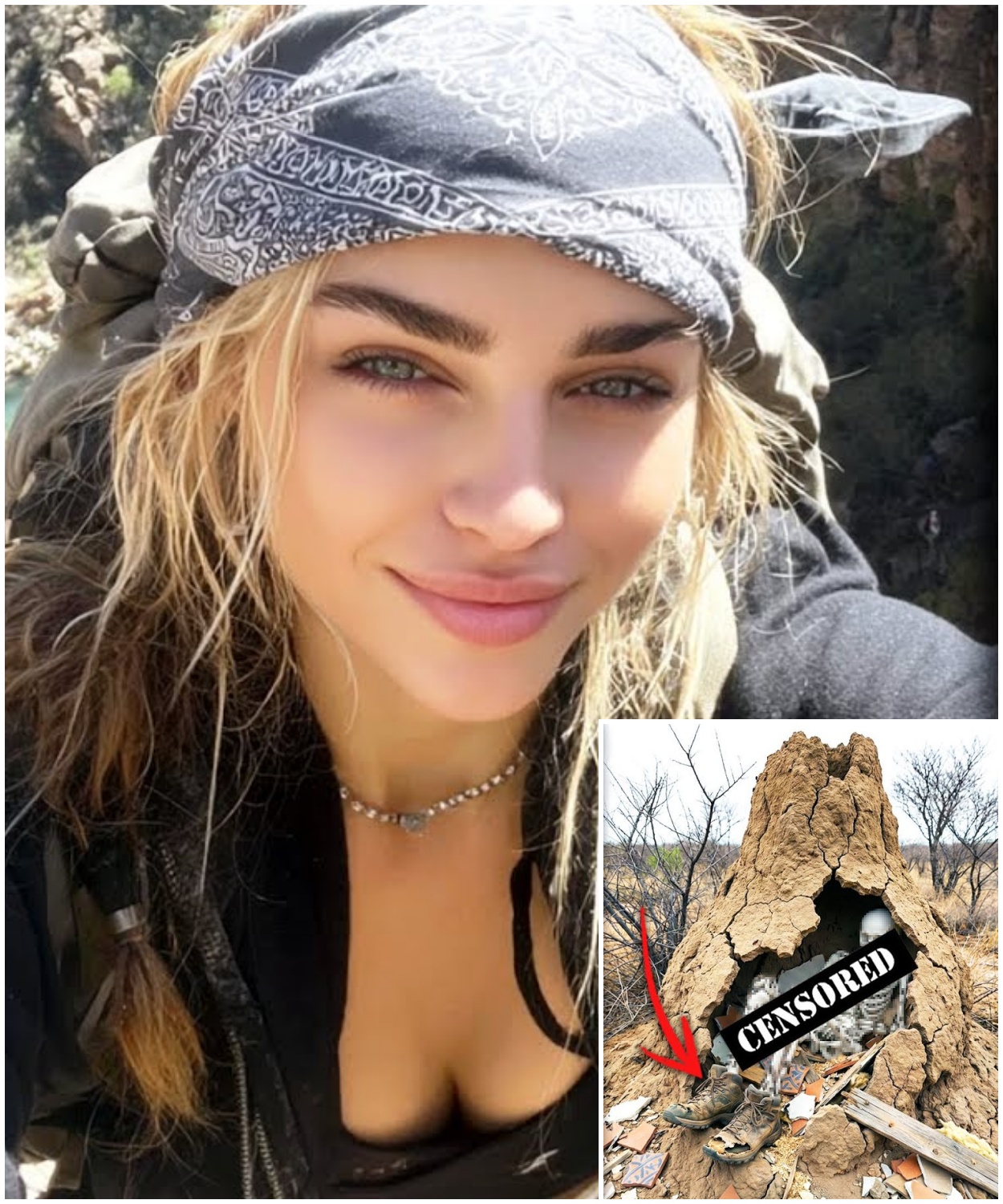

In September of 2017, firefighters clearing the forest came across a strange concrete hard hill 5 ft high.

When the workers struck it with a tool, the crust cracked and everyone froze in horror.

A hiking boot stuck out from inside the fissure right out of the clay monolith and a human bone peaked out.

What had been thought to be a huge termite pit turned out to be a natural sarcophagus.

Inside, bricked up by insects and time, was Milliey’s skeleton, waiting for years for someone to break open this perfect silent grave.

On August 14, 2010, the sun rose over the Sonora Desert at 5:00 40 minutes in the morning.

instantly heating the air to dangerous levels.

For most residents of Mesa, this was a signal to stay indoors.

But for 24year-old Millie Lindsay, the day was supposed to be an escape from the office routine.

She worked as an aspiring architect at the well-known Phoenix firm Skyline Group.

And according to her colleagues, the past weeks had been exhausting with endless drawings and deadlines.

The Superstition Mountains towering on the horizon seemed like the perfect place to restore quiet to her thoughts.

Surveillance cameras on the outskirts of the city captured her dark green Jeep Liberty at exactly 6:30 in the morning.

The video, which was later added to the case, shows only the profile of the girl behind the wheel.

She looked focused, looking straight at the road, and the driver’s window was slightly a jar.

Millie did not stop at gas stations or roadside shops.

She was prepared in advance.

According to a later inspection of her apartment, she had packed everything she needed since Friday evening, planning to get to the start of the route as quickly as possible before the heat reached its peak.

At 7:00 45 in the morning, a dark green SUV crossed the gravel parking lot at the First Water trail head.

It’s a popular entry point to the Tanto National Forest.

But on this August day, it was almost empty.

The ranger on duty, who was just finishing his morning rounds, would later testify, which became the last confirmed fact in the chronology of Milliey’s life.

He recalled seeing a young woman near the open trunk of a Jeep.

She was sitting on the bumper and changing her shoes, taking off her light city sandals, and putting on high hiking boots.

The ranger noted in the report that she did not look confused or anxious.

These were the usual everyday actions of a tourist who knows where she is going.

This was the last visual contact.

After she tightened her shoelaces and started walking toward the trail, Millie Lindsay ceased to exist for the outside world.

The alarm was raised only on Monday morning.

When Millie didn’t show up for the morning meeting at Skyline Group and didn’t answer any of the dozen calls, her supervisor contacted her family.

After a brief check of the apartment, where it looked like the owner had left for a minute, the missing person report was filed with the police.

A full-scale search operation was launched on Tuesday at dawn when the chances of finding the man alive in the Arizona summer were rapidly approaching zero.

The temperature in the shade was over 40° C, and the rocks on the open rocky plateaus were so hot that it was impossible to touch them.

The Arizona Department of Public Safety flew two helicopters equipped with thermal imagers, although the pilots reported that the sunheated rocks were creating too much thermal interference.

Volunteer groups on the ground divided the area around the parking lot into squares.

The first breakthrough came from the dog handlers.

The dogs picked up a clear, confident trail from the door of the Jeep Liberty driver.

They led the group along the main route for about a mile and a half, moving deeper into the canyon.

Suddenly, the animals behavior changed.

They took a sharp left off the trail in a direction that was not marked on any tourist map.

The trail led to a narrow, dry, rocky channel which was clamped by tall boulders.

It was there between two gray stones that one of the searchers noticed a bright spot.

It was a light bandana with a characteristic geometric pattern.

It was lying there as if it had fallen out of his pocket or been torn off by the wind.

The photo of the discovery was immediately passed to Milliey’s colleagues and they confirmed that it was hers.

She often wore this bandana in the office, tying her hair up while working on layouts.

This discovery gave the search team a powerful boost of hope.

The head of the operation was sure that the girl was somewhere nearby.

Perhaps she had twisted her ankle in the riverbed or was looking for shade under overhanging rocks.

The search radius around the place of discovery was narrowed and literally every bush and crevice was combed.

But the bandanna turned out to be the only trace.

Then the area of hard shale began.

a flat stone surface that does not retain sole prints.

The dog circled in place, whining, but could not move on.

The hot wind that had been blowing in the canyon for the past 2 days had scattered any scent marks.

The trail simply broke off as if Millie had vanished into the hot air right after she lost her bandana.

The search continued for another 5 days.

The groups checked deep vertical shafts, old addits that the Superstition Mountains are famous for, and hard-to-reach cornises.

They found nothing.

Neither her backpack, which should have been a bright color, nor a water bottle, nor any signs of a struggle or fall.

The area looked sterile.

The final report of the detective in charge of the case recorded the official version, a tragic accident.

The investigation suggested that Millie had strayed from the trail, probably due to disorientation caused by heat stroke.

In a state of confusion, she could have entered a hard-to-reach area, fallen into one of the deep crevices, or hid in the shadows where she could not be seen from the air.

According to this version, the bandanna was lost at the moment when the girl was losing control of the situation.

3 months after the disappearance, when all resources were exhausted and no new evidence was received, Millie Lindsay’s case was officially frozen.

Her name remained in the database of missing persons, and her dark green jeep was taken by relatives.

The Tanto forest returned to its usual silence, having taken a person and given no answer in return except for a piece of cloth at the bottom of a dry stream bed.

7 years of silence have changed the landscape of the Tanto National Forest beyond recognition.

Seasons of monsoon rains eroded old trails and dry months turned the soil into stone dust, burying any trace of the past.

In September of 2017, this part of the Sonora Desert remained as hostile and close to humans as it had been on the day Millie disappeared.

This time, however, it was not tourists with light backpacks who entered the depths of the forest, but heavy machinery.

The Arizona Fire Protection District’s fire safety group, Arizona Fire and Rescue, had been awarded a government contract to conduct a sanitization effort in a remote sector located about 4 miles from the nearest official hiking trail.

This was an area that was labeled on forestry maps as a high-risk sector for fire.

Dense dry brush, windb blown mosquite trees, and tall dried grass created ideal conditions for a wildfire that could destroy thousands of acres of the reserve.

The team’s task was to create wide fire breaks, strips of clean, plowed land that would stop the fire in the event of a disaster.

The work progressed slowly.

Heavy equipment operators had to maneuver between rocky outcrops and deep ravines that cut through the terrain.

According to the foreman’s report, that morning, the crew was working in the channel of an unnamed seasonal stream that had long since dried up.

The bulldozers cut away the top soil along with thorny shrubs, leaving behind a flat, dead strip.

The noise of the engines drowned out all sounds of the desert, and clouds of red dust hung in the air, clogging filters and settling on the worker’s clothes.

Around 11:00 in the morning, the operator of one of the bulldozers felt a sharp jolt.

The metal blade of his machine hit an obstacle hidden in the dense bushes on the slope of a ravine.

According to the driver’s words recorded later in the report, he first thought he had hit a hidden rock outcropping or boulder that had rolled down the mountain during the previous rainstorms.

He backed up and tried to pry the obstacle with the edge of the bucket to pull it out of the ground, but the object did not budge.

It seemed to be embedded in the landscape.

Stopping the engine, the operator got out of the cab to examine the obstacle.

In front of him stood a massive, irregularly shaped hump about 5 ft high.

It was reddish in color like the surrounding clay, but had an unnaturally smooth molten texture.

It was not a stone.

It was something organic, but as hard as concrete.

Experienced Forest Service workers who responded to the operator’s call immediately recognized the nature of the formation.

It was a giant termite.

Desert termites in Arizona are known for their ability to build extremely strong structures.

Using a mixture of clay, chewed wood, and their own saliva, they create a material that when dried in the sun, becomes a monolith that can withstand the weight of a person or even the impact of a light tool.

This particular hill, however, looked anomalous even for these places.

It was too wide at the base and located at a point where such massive colonies do not usually occur.

The insects had been layering the material for years, turning the pile of unknown base into a solid sarcophagus.

Since the object was located right on the line of a planned fire break, the instructions required its removal.

It was not possible to move it entirely.

It was too heavy and deeply rooted in the ravine slope.

The foreman decided to break it into pieces.

An excavator equipped with a hydraulic hammer, a tool designed to break up concrete and asphalt was brought in.

The first blows of the hammer only left scratches on the surface of the hardened clay, raising clouds of dust.

The structure was so dense that it looked artificial.

However, under hydraulic pressure, the monolith began to give way.

With a dull crack that overwhelmed the hum of the machinery, a large piece of the sidewall broke away from the main massive.

Fragments of hardened earth fell at the feet of the workers, revealing the inner cavity of the thermos.

What they saw made the foreman immediately shout into the radio to stop the work completely.

Sticking out of the fracture, embedded in a dense mass of clay and organic residue, was an object that had nothing to do with geology or the insect world.

It was a hiking boot.

It retained its shape, although the leather and fabric were covered with a layer of fossilized dirt.

The shoe did not lie separately.

It was part of a hole that was hidden inside the monolith.

Peeking out of the lacing, which was partially decayed, but still held its shape, was a human shin bone, white and dry, contrasting with the dark red of the termite nest.

The workers stepped back.

The silence that fell after the engines were turned off was heavy and depressing.

It became obvious that this was not just a natural formation.

Termites do not build nests in an empty place.

They need a base, a source of cellulose which they gradually envelop with their movements.

In this case, the human body became the foundation around which thousands of insects built their fortress for years.

The foreman immediately contacted the county sheriff’s dispatcher.

He informed him that during excavation work, human remains had been discovered buried in the soil in a sector where no tourist had set foot in the last 10 years.

The sun, which had burned away the traces of the missing girl 7 years ago, now illuminated the place where nature in a strange and eerie way had preserved her remains, turning them into part of the desert landscape.

The termite, which the workers had mistaken for an obstacle, turned out to be the perfect grave sealed, solid and silent until the blow of a metal hammer revealed its secret.

When detectives from the Maricopa County Sheriff’s Office arrived, the sun was already at its zenith, flooding the canyon with a pitiles white light.

The area around the split termite pile was instantly surrounded by yellow tape, pushing the fire brigade’s heavy equipment to a safe distance.

In the silence that followed the bulldozer’s shutdown, the gruesome discovery looked even more unnatural.

In the wild desert, dominated only by cacti and rocks, a human shoe peaked out of a red earth monolith, retaining its shape but discolored by the passage of time.

For the forensic scientists and anthropologists working at the site, the recovery of the remains was an unprecedented challenge.

Normally, exumation requires the careful removal of layers of soil with brushes and spatulas.

But here, traditional methods were powerless.

What looked like ordinary clay, turned into a material close to concrete in density over 7 years.

Desert termites, methodically building their colony, bonded each grain of sand with a special secret, creating a shell that could not be penetrated by a regular shovel.

The body was not just lying in the ground.

It was embedded in a sarcophagus that the insects had been building around it for years, centimeter by centimeter.

The forensic team leader decided not to try to free the bones in situ as the risk of damaging the fragile remains with tools was too high.

Instead, they adopted a tactic used by paleontologists, cutting the entire object in blocks along with the surrounding rock.

Using specialized diamondcoated saws, the experts spent hours sawing through the fossilized clay, dividing it into segments that could be transported.

Each block was numbered, packed in protective containers, and loaded into special vehicles with the utmost care.

What had once been a human being now resembled an archaeological find recovered from the bowels of an alien planet in the forensic laboratory in Phoenix.

The second even more painstaking stage of work began in sterile conditions under the bright light of operating lamps.

The specialists began to remove the hard plaque millimeter by millimeter.

It resembled the work of a sculptor freeing a mold from stone.

Only here the price of a mistake was evidence in a murder case.

The termite cement, as experts noted in their reports, played a dual role in the fate of the missing woman.

On the one hand, it created a perfect capsule that completely isolated the body from the outside world.

Thanks to this hard crust, coyotes, vultures, and small rodents, which usually stretch bones across the desert in a matter of weeks, could not get to the remains.

The skeleton remained anatomically intact, preserved in the position in which the body was in the pit 7 years ago.

The biological activity of the insect colony, on the other hand, had devastating consequences for the other evidence.

Termites feed on cellulose, the main component of plant fibers.

During the cleaning of the bones, experts found that the victim’s clothes had almost completely disappeared.

The cotton t-shirt, denim, underwear, everything that had a natural basis was recycled by the insects into building material for their nest.

The only elements left were those that nature could not digest.

Synthetic laces, rubber soles of boots, metal rivets, and fragments of polyester that were part of the trekking equipment.

The lack of clothing made the initial identification difficult, but the shoes that impressed the workers in the forest were the first confirmation.

She was a hiker equipped for a serious hike.

Dentists put the final point in the question of identity.

A comparison of the dental formula of the skull, freed from clay captivity with X-rays provided by Lindsay’s family back in 2010, gave a 100% match.

The characteristic root canal treatment on the lower jaw and the specific location of the wisdom teeth left no doubt.

The official conclusion of the medical examiner was cut and dry.

The remains belonged to Millie Lindsay, who had been missing for 7 years.

However, the most important discovery made in the laboratory was not the body itself, but the environment in which it was kept.

When experts began to analyze the composition of the termite, they noticed anomalies that could not be explained by natural processes.

Usually, desert termites build their nests around dead tree roots or old stumps, using them as a food source and a frame.

But here, in the very center of the monolith under a layer of clay, there were no roots or stumps.

Instead, sifting through the material surrounding the skeleton, forensic scientists began to find strange fragments.

Pieces of compressed white powder glued to the remains of cardboard, small fragments of processed wood with smooth saw edges, sawdust mixed with earth, fragments of metal mesh.

Laboratory analysis showed that the white powder was gypsum and the cardboard remains were industrial paper.

These were fragments of drywall.

The picture that the investigators had developed radically changed the course of the investigation.

The hill in the desert was not a random natural phenomenon.

The basis for the insect colony was a pile of construction waste.

Someone had brought the remnants of a renovation into the forest.

Scrapboards, broken sheets of drywall, sawdust, and other debris and dumped them in a remote ravine.

The termites came to smell the huge amount of wood and cellulose contained in the cardboard of the gypsum boards.

They began to build their colony, absorbing the garbage and building a clay dome over it.

Millie Lindsay did not die of thirst while hiding in the shade.

Her body was inside this pile of garbage.

The position of her skeleton indicated that she had been dumped there carelessly, perhaps from above along with another portion of waste or covered with construction debris after she was in the pit.

It was literally buried under the rubble of someone else’s renovation before nature began its conservation work.

The termites, not distinguishing between the wood and the victim’s cotton clothes, simply incorporated her into their ecosystem, turning the illegal dump into an eternal monument to the crime.

What looked like a part of the wilderness turned out to be a man-made hiding place.

The presence of building materials in such a remote area where there are no roads or housing indicated that someone had purposefully used the ravine to dispose of waste.

And along with the board and plaster, this unknown person was disposing of a human being.

The discovery moved the case from the category of accidents to the category of criminal investigations, where the main physical evidence was the garbage in which Millie Lindsay found her last resting place.

Detective Kurt John, who took over the investigation after the remains were identified, immediately focused his attention not on the biological materials, but on what surrounded them.

What the fire brigade initially mistook for a natural termite pile and the forensic scientists for a sarcophagus became an archive of physical evidence for the detective.

When the experts finally separated the bones from the hardened mass in the laboratory, the stainless steel tables were filled with piles of garbage that had been hidden under a layer of clay for years.

To an outside observer, this would look like ordinary construction waste.

But for the investigation, each piece was critical.

The sorting process lasted several days.

Laboratory technicians sifted through every pound of soil, washing away clay and termite excrement to find the solid fractions.

The result of this analysis completely destroyed the theory that Millie Lindsay was a victim of the desert.

Among the dust and drywall remnants, detectives found fragments that could not have been in the Tanto National Forest by accident.

The first important find was scrap wood.

Despite the fact that termites had been feeding on this material for 7 years, some pieces retained their structure due to their high density and specific oils.

A botanical examination by university experts yielded an unexpected result.

It was mahogany, a mahogany tree.

This species does not grow in Arizona, is not used for cheap frame houses, and is not found in typical middle-class housing.

It was a premium wood imported for the manufacturer of expensive furniture, cabinetry, or high-end interior work.

The presence of this class of scraps in the middle of a pile of garbage indicated that the waste came from a place where money was not saved, but decided to save money on legal disposal.

The second piece of evidence that caught Kurt John’s attention was fragments of ceramic tiles that were found scattered throughout the termite pile.

After the technicians cleaned them of dirt and put them together like a mosaic, the investigators had a clear picture.

It was no ordinary modern tile from a construction hypermarket.

The material had a characteristic rich color of burnt terracotta, a deep warm shade typical of Spanish or Mexican colonial style, but the main detail was the pattern.

Fragments of hand painted blue glaze were preserved on the terracotta background.

The lines were imperfect, indicating handiccraft production rather than a factory stamp.

The style of the pattern was reminiscent of vintage designs from the midentth century.

John noted in the report that such tiles are the signature of a particular house or designer.

It was too specific to be mass-produced.

This meant that the debris was brought from a specific site where an old but expensive flooring was being dismantled.

These findings dramatically changed the qualification of the case.

Now, it became obvious that Millie Lindsay did not get lost, fall off a cliff, or die of dehydration while looking for a way out of the canyon.

Her body ended up in the pit at the same time as the construction debris.

The way the bones were arranged, mixed with fragments of drywall and wood scraps, indicated that they had been dumped together.

The girl’s body was, for someone, the same kind of garbage as the remnants of a renovation that had to be hidden away from view.

The killer used a remote ravine as an illegal dump, hoping that the desert in time would destroy all traces.

He hadn’t taken into account one thing.

The building materials would attract termites, which instead of destroying the evidence, would preserve it in a solid sarcophagus.

While the detectives were analyzing the composition of the debris, a forensic anthropologist completed a detailed study of Milliey’s skull.

His conclusions finally crossed out the accidental death theory.

A clear fracture line was found on the right parietal bone closer to the temporal region.

In his report, the expert described the nature of the injury in detail.

It was a depressed fracture with divergent edges that showed no signs of healing.

This meant that the injury was a lifelong one inflicted just before or at the time of death.

The nature of the bone damage indicated a blow from a blunt, hard object with significant kinetic energy.

It could not have been the result of a fall on stones.

When people fall from a height, they usually suffer complex injuries, often affecting the limbs and the base of the skull.

Here, there was one localized powerful blow.

The anthropologist also ruled out the possibility that the skull had cracked under the weight of soil or debris.

The termite cement distributed the load evenly, protecting the bones from pressure.

The crack had microscopic radial branches which occur only when a living bone containing organic compounds and moisture is struck dynamically.

Dry bone breaks differently.

The conclusion was unequivocal.

Millie Lindsay’s death was the result of violence.

She was hit on the head with a heavy object which led to instant loss of consciousness or death.

After that, the body was taken to the woods and dumped into a ravine, sprinkled with construction debris to disguise the crime.

The sheriff’s office officially reclassified the case from a missing person to a murder.

Investigators realized that the key to unraveling the killer’s identity lay not in Milliey’s motives or her personal life, but in the pile of garbage that became her grave.

Unique vintage tiles and expensive mahogany were no longer just waste.

They were the only thread that could lead the police to the house where this chain of events began 7 years ago.

Detective John realized that they needed to find the place where the old terracotta floor was torn up and the mahogany scraps thrown away.

In August 2010, in a forensic science laboratory in Phoenix, fragments of pottery taken from a monolithic sarcophagus were laid out on a white table under bright lights.

They were dirty, partially damaged pieces of terracotta, but after chemical cleaning, a clear pattern emerged.

The blue glaze applied by hand formed specific geometric ornaments that did not look like typical products from construction hypermarkets.

For Detective Curt John, these fragments became the silent witness that could lead the investigation out of the desert and into civilization.

It took three days for the experts in architectural design and ceramic history to identify the material.

The answer came from a former Scottsdale based distributor of luxury finishing materials.

He recognized the tile instantly.

It was a limited edition collection called Casa Grande Ceramic, which was made in small batches to order for southwestern design projects.

The key detail was that the production of this series was finally stopped in 2008 due to the bankruptcy of the manufacturing.

This meant that the search circle narrowed from millions of homes to a few hundred properties.

The tiles could not have been bought in a store in 2010.

They had already been installed in someone’s house and they were dismantled that summer.

It was construction debris that resulted from the reconstruction or demolition of an old interior.

Detective John focused on geography.

The place where Milliey’s body was found was in the eastern part of the Tanto forest.

The closest communities from which a garbage truck could have been discreetly removed were Apache Junction, the eastern part of Mesa, and the prestigious Gold Canyon neighborhood.

Investigators sent formal requests to the city and county planning departments of these counties.

They had to check thousands of records of construction and reconstruction permits issued between May and August of 2010.

The work with the archives was exhausting.

The police were looking for specific keywords in the descriptions of the work.

Floor dismantling, patio replacement, kitchen remodeling.

Most of the permits were for minor roof repairs or swimming pool installations which did not match the nature of the garbage found.

However, at the end of the second week of searching, the analyst identified one record that fit perfectly into the time frame.

A permit for a large-scale reconstruction of a residential building was issued in June of 2010.

The facility was located in an elite gated community in Gold Canyon, an area where homes cost millions and the privacy of residents is protected by barriers and cameras.

The description of the work read, “Complete removal of firstf flooror flooring, reconstruction of outdoor patio, replacement of kitchen finishes.

When Detective John and his partner arrived at the address, they saw a luxurious desert-style estate surrounded by tall saguaros and perfectly manicured landscaping.

It was a world as far away as possible from the muddy pit in the woods where Millie had been found.

The owners of the house, an elderly wealthy couple, greeted the police with surprise, but agreed to answer questions.

During the conversation, the detective showed them a photo of a cleaned fragment of tile with a blue pattern.

The owner’s reaction was instantaneous.

The woman confirmed that this was the exact same tile that covered their kitchen floor and backyard when they bought the house.

She recalled that this style seemed outdated and too dark.

So, in the summer of 2010, they decided to overhaul the house, replacing the terracotta with light Italian marble.

The testimony of the owners was decisive.

They described the repair process in detail.

According to them, dismantling the old tiles was the dirtiest part of the job.

Workers knocked it off with jackhammers for several days, piling up mountains of debris on the driveway.

The owners emphasized that it was important to them that the construction waste was removed quickly without spoiling the appearance of the upscale neighborhood.

They paid the contractor substantial sums of money for ecological disposal and for taking the waste to a certified landfill.

When Detective John asked who had done the work, the owner pulled up old financial reports he kept in his home office.

In the folder with the invoices for 2010 was a contract for construction services.

In the contractor column was the name of the company, Desert Valley Renovations.

It was a small firm that specialized in renovating private homes in the East Valley.

The owner and main contractor whose signature was on the obligation to remove and dispose of the construction debris was a man named Clayton Riggs, known in business circles simply as Clay.

The owners remembered him as a man of strong build who personally led the crew and often drove his work truck himself to save money on hired drivers.

For the investigation, it was the moment of truth.

The tile fragments found in the bones of the dead girl were given a precise address of origin.

The garbage that became Milliey’s grave was not nameless.

It belonged to a specific house and was taken out by a specific person.

Clayton Riggs had taken money to legally dispose of tons of heavy construction debris, but landfill records that detectives checked in parallel showed that no truck from his company had entered official landfills during that period.

Now the police had a name.

Clayton Riggs had become the main suspect in the murder case, although he probably thought he had safely buried his secret 7 years ago along with other people’s renovations in the middle of the desert.

When Clayton Rigg’s name first appeared on the board in Detective Kurt John’s office, it was just one of many in a chain of construction contractors.

However, as investigators delved into the financial history of his company, Desert Valley Renovations, it became clear that in August of 2010, the business was teetering on the brink of total collapse.

Arizona was still recovering from the effects of the Great Economic Recession, and the construction market, which had been booming for years, suddenly collapsed.

Renovation orders became rare.

Competition increased to critical levels, and project margins plummeted.

For small players like Rigs, every dollar was crucial, and it was this desire to save money at all costs that laid the foundation for the tragedy.

Detectives requested the company’s full financial statements for the third quarter of 2010.

The documents received from the bank painted a picture of despair, overdue payments for leasing equipment, debts to material suppliers, and constant cash gaps.

But the most telling document was the waste disposal expense log.

According to the contract with the owners of the Gold Canyon estate, rigs received a separate rather substantial amount for the removal of construction waste.

The estimate was clear.

Dismantling, removal, and ecological disposal of solid waste.

The scope of work involved several tons of heavy cargo, broken tiles, concrete, plaster, and wood.

The nearest official place to accept such cargo was the Salt River Landfill.

This certified landfill, which serves the eastern part of the valley, has a strict accounting system.

Each truck entering the site is weighed and the driver receives a receipt indicating the exact weight, time, and cost of services.

The fee per ton of construction waste in 2010 was high, especially for commercial haulers.

For Rigs, who was trying to close the budget gap, the landfill check could have eaten up all the profits from the demolition work.

Investigators filed a formal request with the Salt River Landfill Administration to provide statements of all Desert Valley renewables as transactions for August 2010.

The response was short and comprehensive.

No vehicles registered to Rigs’s company had crossed the landfill checkpoint during the period in question.

Moreover, the database did not record a single payment on his behalf at any other licensed landfill within a 50-mi radius.

This meant only one thing.

The tons of garbage that disappeared from the Gold Canyon yard never made it to their destination.

They had disappeared into thin air, or as the police suspected, they had been dumped where there was no charge.

To confirm this hypothesis, Detective John began a series of interviews with former Rigs employees.

It was not easy to find them.

The company’s staff turnover was high, and many worked unofficially for cash.

However, through tax records, they managed to track down a man named Carlos, who worked as a laborer on Rig’s crew in the summer of 2010.

His testimony became a key element in building the suspect’s profile.

Carlos, who had long since left the construction site at the time of the interrogation, recalled his former boss with undisguised hostility.

According to him, Klay was a man who hated unnecessary costs and considered environmental fees a government conspiracy against small businesses.

During the interrogation, the former employee said that the practice, which they called wildcatting among themselves, was the norm for rigs, not the exception.

Instead of paying hundreds of dollars for landfill tickets, Clay would often order them to load the trash into the back of a truck and wait until the end of the day.

As the sun began to set and traffic on the roads decreased, he would get behind the wheel himself and drive off toward the desert.

Carlos noted that rigs knew the network of dirt roads and old logging roads that led deep into the Tanto National Forest.

These were places where rangers rarely visited and casual tourists did not enter due to the difficult terrain.

Investigators paid special attention to transportation.

The witness described in detail the company’s workhorse, an old powerful white Ford F4 150 dump truck with high extended sides.

This vehicle was the perfect tool for such operations.

It had high crosscountry ability, could take on a lot of weight, and most importantly, was equipped with a hydraulic body tipping mechanism.

This made it possible to get rid of the evidence in a matter of minutes.

It was enough to find a deep ravine, back up, press a lever, and the pile of garbage instantly disappeared down below, away from the road.

Carlos recalled that in August of 2010, this Ford was constantly shuttling between the Gold Canyon facility and the eastern outskirts of the valley.

He also noted one detail that seemed insignificant to him at the time, but now has taken on a sinister meaning.

Rigs always traveled alone to unload.

He never took his assistance with him, explaining that he didn’t want to screw the guys over or simply save them time.

In fact, the detectives assumed he simply did not want any witnesses to his illegal activities, which under federal law could lead to huge fines and confiscation of equipment.

Detectives also checked the truck’s technical history.

Although Rigs had sold the truck back in 2012, there were service records in the database of local car repair shops.

The mechanic who repaired the suspension of this Ford in the fall of 2010 recalled that the car was in terrible condition.

The undercarriage was clogged with red clay mud, typical of the off-road conditions of the Tanto forest, and the bottom had numerous scratches from contact with stones and brush.

This confirmed the words of witnesses.

The heavy vehicle regularly drove off the asphalt onto rough terrain where, according to the logic of urban construction, it had no business being.

The economic benefits of such trips were obvious.

In one trip, Rig saved about $150 in disposal fees, plus fuel costs, because the forest was much closer than the official landfill on the other side of town.

For the entire Gold Canyon facility, this amount could reach several thousand enough to cover a month’s loan payment or pay a late paycheck.

For a person on the verge of bankruptcy, this was a sufficient motive to break the law.

Having collected all these facts, Detective John got a clear picture of the events.

Clayton Riggs was a systemic violator who turned protected lands into his personal free dump.

He acted brazenly, confidently, and as he thought, unnoticed.

His old Ford became a ghost on the forest roads, appearing where no one expected it and leaving behind piles of construction debris.

Now, the police had not just suspicions, but a documented pattern of the suspect’s actions that led him to the same time and place where Millie Lindsay was last seen.

All that remained was to prove that one August morning he had taken not only an old tile into the woods, but something much more terrible.

When physical evidence, fragments of terracotta tiles and mahogany scraps, pointed to Clayton Riggs, the investigation had a suspect, but no direct evidence of his presence at the murder scene.

Rigs sold the Ford F450 dump truck, which was mentioned in the testimony of former employees 5 years ago.

The new owner had repainted the truck, changed the body, and put hundreds of thousands of miles on it, making it virtually impossible to find microscopic traces of blood or DNA in the cab.

It seemed that the only thread that could link the contractor to a specific geographic location in the desert had been severed by time.

But in today’s world, even shadows leave a digital footprint if you know where to look.

Detective Kurt John noticed a detail in the financial documents of Desert Valley renovations.

In the column of regular monthly expenses for the years 2009 and 2010, there were payments to a large insurance company specializing in commercial vehicles.

In those years, at the peak of the economic crisis, insurers offered businesses reduced rates in exchange for installing telemetry equipment.

These were passive GPS trackers that recorded roads, speed, sudden braking, and downtime.

Officially, this was done to monitor driving safety, but in fact, the system created a complete digital log of the car’s life.

Investigators immediately sent a court order to the insurance company’s headquarters.

The hope was illusory.

Usually, such data is stored on servers for a limited time and then overwritten with new logs.

However, the insurers’s lawyers announced the news that became a turning point in the case.

Because Clayton Riggs had had several insurance claims and disputes over payments in the past, his full travel history was transferred to long-term storage servers as potential evidence for arbitration.

The file, which contained the movement history of a white Ford for August 14, 2010, had been in digital storage for 7 years, waiting to be opened.

When the sheriff’s department analysts loaded the data set into a mapping program, a root line appeared on the screen that looked like a sentence.

The system recorded that Rigs’s truck had started the engine outside his home at 6:00 15 minutes that morning.

It drove to a facility in Gold Canyon where it spent about an hour, the time it takes to load heavy construction debris.

And then instead of turning west toward the official landfill, the car headed northeast toward the Superstition Mountain Range.

The dots on the map showed how the truck left the paved highway for an old maintenance road that was used only for power line maintenance.

It was the same wild route that witnesses had described.

The road was broken, so the speed dropped to 5 to 7 mph.

But the worst part was where the road intersected with the tourist area.

The technical dirt road that Riggs was driving on ran perpendicular to the Firstwater hiking trail, the exact route that Millie Lindsay had taken.

According to the billing data and time calculations, their paths crossed at the same point in space and time to within a few minutes.

The truck, loaded with the wreckage of someone else’s repair, and the girl, looking for silence, ended up in the same deserted sector of the desert where there was no other witness for miles around.

The most critical piece of evidence was the timing of the stop.

The GPS log showed that the truck stopped at the edge of a deep ravine at 8:00 20 minutes in the morning.

The engine idled for another 3 minutes and then shut off.

The system recorded that the car remained stationary at this point for exactly 40 minutes.

For Detective John, these 40 minutes were the key to understanding what happened.

The illegal dumping procedure described by Riggs’s former employees usually took no more than 5 to 10 minutes.

The driver would simply drive up the slope, turn on the hydraulics, wait for the body to rise, and drive away without leaving the cab for long.

40 minutes of downtime in the hot desert without air conditioning was an anomaly.

It was time that could not be explained by the simple disposal of drywall.

It was time needed for something else, for interaction, for conflict, for hiding the consequences.

Based on this data, the investigation team was able to reconstruct a possible scenario of the tragedy.

The detective’s theory was as follows.

Millie Lindsay walking along the path heard the noise of a heavy engine in an area where cars should not drive.

She could follow the sound and see a man dumping tons of garbage in a protected canyon.

For Millie, who was an architect and appreciated nature, this could have been a moment of outrage.

Investigators suggested that she did not just walk by.

She could have stopped, made a comment, or worse for Rigs, pulled out her camera or phone to capture the offender’s license plate.

Clayton Riggs was in a state of extreme psychological stress at the time.

His business was falling apart.

His debts were mounting.

And a fine for polluting a national park, which in Arizona reaches tens of thousands of dollars and threatens to confiscate his equipment, would have been the final nail in the coffin.

He could not afford witnesses.

A brief fatal confrontation took place in that dead end under the scorching sun.

Detectives believed that the 40 minutes recorded by the tracker was the time it took Rigs to realize what he had done after the impact.

to go down to the ravine to the body and cover it with the rest of the construction debris using the shovel that was always in the back of the truck.

He didn’t just dump the load.

He carefully shaped the very pile that would later become the basis for the termite pile.

The GPS data became the very digital ghost that came back from the past to destroy the suspect’s defense.

They placed him at the crime scene, gave him a time frame for the murder, and explained why the body was found among the trash.

Rigs thought he was saving on gasoline and landfill fees, but in fact, he was leaving behind an electronic trail that led police right to his door 7 years later.

Now, the investigators had more than just a pile of bones and trash.

They had a precise timeline of the last moments of Millie Lindsay’s life.

The operation to detain Clayton Riggs was planned for the morning hours of October 4, 2017.

A special forces team along with detectives from the sheriff’s office surrounded his home in Apache Junction.

It was a typical one-story structure with peeling stucco and a yard filled with old car parts.

The home of a man whose business had long since gone under, but whose habit of hoarding remained.

When the officers knocked on the door, Rigs answered it in his underwear, a cup of coffee in hand.

According to the officers, he did not resist, but his eyes showed a complete lack of understanding of why the police had come for him after all these years.

He was sure that his secret was safely hidden in the desert.

While the suspect was being taken to the police station for questioning, the forensic officers began a detailed search of the property.

The warrant allowed them to turn everything upside down, and they took full advantage of this right.

The garage was of most interest to the investigators, a huge, dusty room that Rigs had used as a warehouse for the remnants of his past life.

Here, among the cans of dried paint, rusty tools, and stacks of old tax returns, the detectives searched for anything that might link him to Millie Lindsay.

Luck smiled on them during the third hour of searching.

On the top shelf of a metal rack, under a layer of dust, there was a cardboard box with a careless inscription in black marker.

Miscellaneous.

Inside were old chargers, tangled cables, and small electronics that had fallen out of use.

Among this technical garbage, the detective found a compact digital camera made by Canon.

It was old, worn.

The battery had long been discharged and swollen with time, but the body was intact.

On the bottom of the camera was a factory sticker with a serial number.

When the detective dictated the numbers over the phone to his colleague, who was holding a copy of a receipt from an electronic store dated August 2010, the other end of the line fell silent.

The numbers matched down to the last digit.

It was Millie Lindsay’s camera, the same one she had bought a week before her fatal hike to capture the landscapes of the Superstition Mountains.

The discovery became the smoking gun that the investigation needed so badly.

As profilers later suggested, Rigs did not take the camera as a trophy.

In a state of panic, he probably thought that the girl might have managed to take a picture of him or his truck as he was dumping the garbage.

He took the camera to destroy the evidence, but when he got home, he just threw it in a box of junk, planning to deal with it later.

And as is often the case, he forgot about it, burying it under a layer of household items in the same way he had buried the owner under a layer of construction waste.

The interrogation of Clayton Riggs lasted more than 6 hours.

At first, he remained confident, denying any involvement in the girl’s disappearance and claiming that he had never seen her.

He admitted that he may have been illegally removing garbage, trying to reduce it to an administrative offense from the past.

But the defense strategy fell apart when Detective Kurt John began to lay the evidence on the table.

First, photos of terracotta tiles from his facility.

Then, printouts of the GPS logs that placed his truck at the crime scene at the time of the murder.

And finally, the cannon camera itself in a transparent evidence bag.

When Rig saw the camera, he turned pale.

According to a lawyer who was present during the interrogation, the suspect realized that his own negligence and greed had backed him into a corner.

After a long pause, he asked for water and began to speak.

His confession was dry, devoid of remorse, more like an attempt to justify his actions by the circumstances.

He said that he was on the verge of a nervous breakdown that morning.

Debts were strangling him.

The heat was unbearable.

And the risk of getting a huge fine for illegal dumping in a national park seemed like the end of the world.

As he was dumping a pile of garbage in a ravine, a girl suddenly appeared.

Rigs claimed that Millie started yelling at him, threatening to call the rangers.

She allegedly raised her camera to take a picture.

In a state of passion, he rushed to her to grab the camera.

According to Rigs, he did not plan the murder.

He claimed that he just pushed her hard.

Millie lost her balance, staggered, and hit her temple on the sharp metal side of the truck.

She fell to the ground and stopped moving.

Rigs checked for a pulse, but found none.

Realizing that something irreparable had happened, he panicked.

Instead of calling for help, he decided to cover his tracks.

He pushed the body into the ravine where he had dumped a pile of drywall and boards a minute earlier.

Then he took a shovel and started throwing the rest of the garbage that was still in the back of the truck and sprinkled earth and stones on top to create the appearance of a natural scree.

He took the camera, got into the truck, and drove away, leaving Millie under a thick layer of construction waste.

He was sure that coyotes would stretch the body and the rains would wash away the traces.

But rigs didn’t take into account the laws of nature, which he was trying to deceive.

Drywall contains cellulose, and mahogany wood contains nutrients.

This huge pile of organic matter became a beacon for a colony of underground termites.

Instead of destroying the body, the insects began to build their home around it.

Using the garbage as a resource, they built a heavyduty mound over Milliey’s body and the crime evidence which protected them from the sun, water, and predators.

The nature that Rigs had polluted paradoxically preserved the truth of his crime in the form of a 5-ft monument.

The trial was swift.

The evidence base gathered from the archive in the termite bin and the garage find left the defense no chance.

The jury found Clayton Riggs guilty of seconddegree murder and concealing the body.

The judge, reading out the verdict, called his actions an act of cowardice and cruelty, sentencing the former contractor to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

The case of Millie Lindsay is a reminder that nothing disappears in the desert without a trace.

Even after 7 years, the land can return what has been stolen from it, turning an ordinary pile of garbage into an indictment written by nature itself.

News

Ilhan Omar ‘PLANS TO FLEE’…. as FBI Questions $30 MILLION NET WORTH

So, while Bavino is cracking down in Minnesota, House Republicans turning the heat up on Ilhan Omar. They want to…

FBI & ICE Raid Walz & Mayor’s Properties In Minnesota LINKED To Somali Fentanyl Network

IC and the FBI move on Minnesota, touching the offices of Governor Tim Walls and the state’s biggest mayors as…

FBI RAIDS Massive LA Taxi Empire – You Won’t Believe What They Found Inside!

On a Tuesday morning, the dispatch radios in hundreds of Los Angeles taxi cabs suddenly stopped playing route assignments. Instead,…

Brandon Frugal Finally Revealed What Forced Production to Halt in Season 7 of Skinwalker Ranch….

The Secret of Skinwalker Ranch became History Channel’s biggest hit. Six successful seasons documenting the unknown with real science and…

1 MINUTE AGO: What FBI Found In Hulk Hogan’s Mansion Will Leave You Shocked….

The FBI didn’t plan to walk into a media firestorm, but the moment agents stepped into Hulk Hogan’s Clearwater mansion,…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage… It started like any other evening…

End of content

No more pages to load