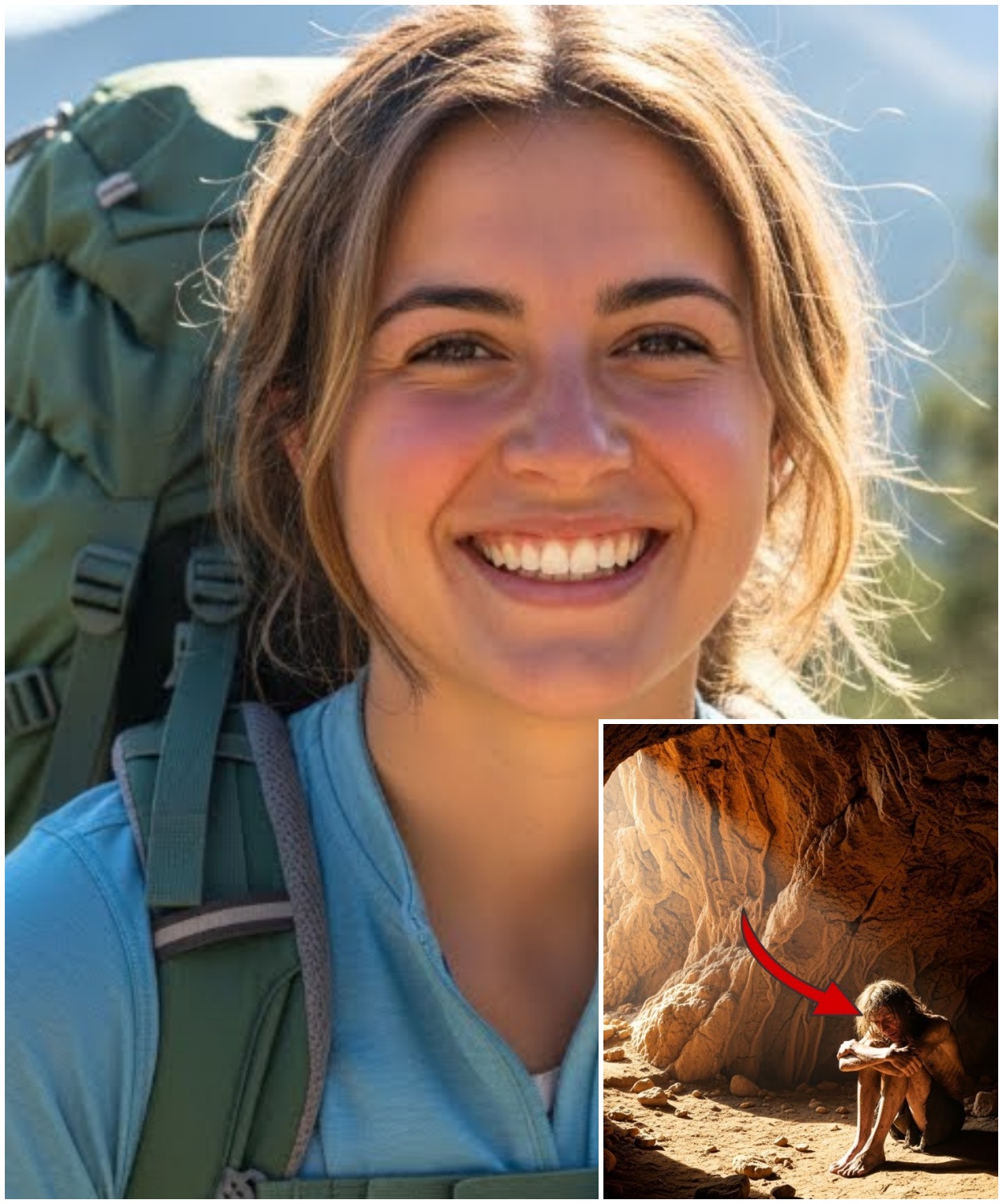

In August of 2017, 26-year-old graphic designer Rebecca Hollis vanished without a trace in the Sawtooth Mountains of central Idaho.

Search teams combed the wilderness for weeks, checking every trail, every overlook, every possible route she might have taken.

They found nothing.

No clothing, no equipment, no signs of struggle.

It was as if the mountains had swallowed her hole and left no evidence behind.

Then almost exactly one year later, when a team of amateur explorers decided to document an unmapped cave system near Redfish Lake, they made a discovery that would shake the entire state.

Deep in a narrow chamber far beyond where sunlight could ever reach, they found a figure huddled against the cold stone wall.

At first, they thought it was an animal or perhaps the remains of someone long dead.

But as their headlamps swept across the scene, they saw movement, a slight rise and fall of the chest, shallow breathing.

The figure was alive.

It was Rebecca.

And from that moment, a story unfolded that redefined what people thought possible about survival, isolation, and the human mind’s capacity to endure unimaginable darkness.

On August 14th, 2017, the weather in the Sawtooth National Forest was nearly perfect.

Clear skies, mild temperatures, and a light breeze that made hiking comfortable even in the afternoon sun.

Rebecca Hollis arrived at the trail head for Iron Creek Trail just after 10:00 in the morning.

Security footage from a nearby Ranger Station captured her silver Honda Civic pulling into the gravel lot at 9:58.

She parked near the wooden trail marker, grabbed a small daypack from the passenger seat, and walked toward the information kiosk.

According to the log kept at the entrance, Rebecca signed in at 10:12.

Her handwriting was neat and deliberate.

She listed her intended route as Iron Creek to Sawtooth Lake, a moderate hike that typically took 4 to 5 hours round trip.

Friends who knew her well said Rebecca was cautious by nature.

She had been hiking in Idaho since moving to Boise 3 years earlier and always followed the basic rules.

She carried water, a map, a charged phone, and a small first aid kit.

She told people where she was going.

She never took unnecessary risks.

That is why her disappearance seems so incomprehensible from the very beginning.

The last confirmed sighting of Rebecca came from a couple who passed her on the trail around 11:30 that morning.

They were descending as she climbed higher.

In their statement to investigators, they described her as calm and focused.

She smiled at them, said good morning, and continued upward without stopping.

The man recalled that she was wearing a blue jacket and carrying a gray backpack.

His wife remembered that Rebecca seemed perfectly comfortable, not lost or distressed in any way.

That brief exchange was the final piece of verified evidence that Rebecca Hollis was on the trail that day.

Everything after that moment became a mystery.

Rebecca was supposed to meet her roommate, Jessica Puit, for dinner that evening at 7:00.

When she did not show up and did not answer her phone, Jessica assumed she had lost track of time or decided to stay out later to catch the sunset.

By 9:00, she started to worry.

By 10:00, she was calling repeatedly when there was still no response.

By 11:00, Jessica contacted the Blaine County Sheriff’s Office.

The dispatcher took down the information and immediately forwarded it to the search and rescue coordinator for the Sawtooth region.

The first responders arrived at the Iron Creek trail head shortly after midnight.

Rebecca’s car was still there, parked exactly where she had left it.

The doors were locked.

Inside, officers found her wallet, her keys, a half empty bottle of iced tea, and a notebook she used for sketching.

Her phone was not in the car.

That gave the search team’s hope.

If she had it with her, there was a chance she could call for help or that they could track the signal.

They tried pinging her phone immediately.

The signal came back weak and inconsistent somewhere in the higher elevations near the lake, but it was impossible to pinpoint.

Within hours, the ping stopped entirely.

Either the battery had died or the phone had been damaged.

At first light on August 15th, the search operation officially began.

Teams of rangers, volunteers, and trained search dogs spread out along the Iron Creek Trail and into the surrounding wilderness.

Helicopters equipped with thermal imaging cameras flew low over the ridges and valleys.

Drones were deployed to scan areas that were difficult to reach on foot.

For the first three days, the weather held.

Searchers covered every section of the trail, every alternate route, every rocky outcrop where someone might have fallen or become stranded.

They checked the lake shore, the stream beds, the dense patches of forest where visibility dropped to nearly zero.

They called her name until their voices went horsearo.

They listened for any sound that might indicate she was nearby, but there was nothing, no response, no sign, not even a footprint that could be definitively linked to her.

On the fourth day, the search expanded.

Crews moved into more remote areas, places where casual hikers rarely ventured.

They repelled down cliff faces, waited through icy creeks, and checked abandoned campsites left by hunters and fishermen.

The dogs picked up faint traces in a few locations, but none of them led anywhere conclusive.

Each trail ended in confusion, the scent dispersing into the wind or mixing with those of other hikers.

By the end of the first week, more than 200 people had participated in the search.

Local news stations ran daily updates.

Rebecca’s photo appeared on missing person bulletins across the state.

Her family flew in from Oregon and joined the volunteers, walking the trails themselves, handing out flyers and pleading with anyone who might have information to come forward.

Her father told a reporter that Rebecca was smart and resourceful.

If she was injured, she would find a way to signal for help.

If she was lost, she would stay put and wait to be found.

He could not understand how she could simply vanish in broad daylight on a trail that dozens of people used every week.

Investigators reviewed every possibility.

They checked her financial records to see if she had planned to leave voluntarily.

Nothing unusual appeared.

They interviewed her friends, co-workers, and recent acquaintances to rule out foul play.

Everyone described Rebecca as stable, happy, and engaged with her life.

There were no signs of depression, no conflicts, no reasons to suspect she had walked away on purpose.

They even brought in a criminal profiler to assess whether she might have been abducted.

The profiler concluded that the location and circumstances made an abduction highly unlikely.

The trail was too public, too unpredictable.

An opportunistic crime in such a setting would leave evidence, and there was none.

After two full weeks, the official search was scaled back.

The sheriff’s department issued a statement explaining that they had exhausted all immediate leads and would transition to a sustained but lower intensity effort.

Family members were devastated.

Jessica Puit later described the announcement as the moment she realized Rebecca might never come home.

Four months afterward, smaller groups continued to search on weekends.

Volunteers who had never met Rebecca organized their own hikes into the wilderness, hoping to find something the professionals had missed.

Online communities dedicated to missing persons cases analyzed maps, shared theories, and proposed new search grids.

But despite all the effort, all the dedication, and all the hope, nothing changed.

Rebecca Hollis remained missing.

Her case was classified as cold by the end of the year.

Detectives kept the file open and periodically reviewed it for new information, but there were no breakthroughs.

In public statements, the lead investigator admitted that Rebecca’s disappearance was one of the most perplexing he had encountered in his career.

There were no mistakes in her planning, no environmental hazards that could explain such a total absence of evidence, and no credible sightings after she left the trail head.

It was as if she had stepped off the edge of the world.

Rebecca’s family refused to give up.

Every few months, they returned to the Sawtooth Mountains and retraced her last known steps.

They placed new flyers at trail heads, spoke to rangers, and kept her name in the local news.

On the first anniversary of her disappearance, they held a small memorial hike along Iron Creek Trail.

About 30 people attended, including some of the original search volunteers.

They walked in silence, each carrying a candle, and gathered at the lake to share memories of Rebecca.

Her mother spoke briefly, saying that they still believed she was out there somewhere and that they would never stop looking.

At that very moment, less than 5 mi away, Rebecca Hollis was still alive.

She was deep underground, buried in a darkness so complete that she had long since stopped trying to measure time.

And she had no idea that anyone was still searching for her.

The discovery happened on August 11th, 2018, almost exactly 1 year after Rebecca disappeared.

Three men from a Boise based exploration group called Mountain Hollow Adventures had spent the previous weeks researching cave systems in the Sawtooth area that were not widely documented.

They were not professional speliologists, but they had experience with underground mapping and a genuine interest in finding passages that had been overlooked by earlier surveys.

The leader of the group, a 34year-old outdoor equipment store manager named Derek Pullman, had found references in old forestry reports to a series of limestone cavities near Redfish Lake that had never been fully explored.

The references were vague, dating back to the early 1980s, and most of them mentioned the caves as unstable or unsuitable for public access.

That made them exactly the kind of place Derrick and his team wanted to document.

On the morning of the 11th, Derek, along with his two companions, Ian Moss and Trevor Lang, drove to a remote access road about 2 mi west of the main tourist areas around Redfish Lake.

They parked their truck in a clearing and hiked for nearly an hour through dense forest and over uneven terrain before reaching the coordinates Dererick had marked on his GPS.

The entrance to the cave system was barely visible, hidden behind a collapsed section of hillside and overgrown with brush.

If they had not been looking specifically for it, they would have walked right past.

The opening was narrow, just wide enough for a person to squeeze through if they turned sideways.

Dererick went in first, followed by Ian and then Trevor.

They carried headlamps, backup flashlights, rope climbing gear, and a handheld camera to document their findings.

The initial passage sloped downward at a steep angle, forcing them to brace themselves against the walls to avoid sliding.

The air inside was cold and damp with a faint mineral smell that is common in limestone formations.

After about 20 ft, the passage widened into a small chamber with a ceiling low enough that they had to crouch.

Dererick noted the time and their position in a small notebook he kept for logging their routes.

They moved carefully, testing the ground ahead of them for loose rock or sudden drops.

Ian, who had some training in geology, pointed out striations in the stone that suggested water had carved these passages over thousands of years.

The walls were slick in places, covered with a thin layer of moisture that reflected their lights in strange shifting patterns.

After another 30 minutes of slow progress, they reached a junction where the main passage split into two narrower tunnels.

Derek chose the left tunnel because it seemed to slope less steeply.

They entered single file, their shoulders brushing against the stone on both sides.

The tunnel twisted and turned, descending gradually deeper into the earth.

At several points, they had to crawl on their hands and knees through sections where the ceiling dropped to less than 3 ft.

Trevor later told investigators that he almost suggested turning back during one of these tight squeezes, but Dererick was determined to see where the passage led.

Finally, after what felt like an eternity, but was probably only another 15 minutes, the tunnel opened into a larger space.

Derek stood up carefully, sweeping his headlamp across the area.

The chamber was roughly circular, about 12 ft in diameter, with a ceiling that rose to maybe seven or 8 ft at its highest point.

The floor was uneven, covered in loose gravel and small rocks.

The air was noticeably colder here, and there was absolute silence except for the sound of their breathing.

It was Ian who first noticed something unusual in the far corner of the chamber.

He called out to Derek and pointed his light toward a shape that did not look like natural rock.

At first, Dererick thought it might be a pile of old camping gear or debris that had washed in during a flood.

But as they moved closer, the shape became clearer.

was a person.

The figure was sitting upright with its back pressed against the stone wall, knees drawn up to the chest, arms wrapped tightly around the legs.

The head was bowed forward, chin resting on the knees.

Long hair hung down in tangled, matted clumps, so dirty that its original color was impossible to determine.

The clothing was torn and filthy, barely recognizable as fabric.

The skin on the visible arms and feet was gray and rough, covered in grime and what looked like old bruises or soores.

For a long moment, none of the three men moved.

They stood frozen, their lights fixed on the figure, each of them trying to process what they were seeing.

Dererick later said that his first thought was that they had stumbled onto a body, someone who had died in the cave years ago and had somehow mummified in the cold, dry air.

But then Trevor noticed something that made his stomach turn.

The chest was moving.

It was barely perceptible, just a slight rise and fall, slow and shallow, but it was there.

The person was breathing.

Dererick immediately pulled out his radio to call for help, but there was no signal this deep underground.

Ian moved a step closer, his voice shaking as he called out softly.

He said, “Hello.

” Asked if the person could hear him.

Tried to get some kind of response.

There was nothing at first.

No movement, no sound, no acknowledgement.

Then very slowly, the head lifted.

The face that turned toward them was almost unrecognizable as human.

The eyes were sunken deep into the skull, surrounded by dark hollows.

The cheeks were gaunt, the lips cracked and colorless.

The expression was blank, empty, as if the person was looking through them rather than at them.

Ian asked again if she could hear him, and this time there was a faint flicker in the eyes, a tiny shift that suggested some level of awareness.

Dererick told Trevor to stay with her while he and Ian made their way back to the surface as quickly as possible to get help.

Trevor knelt down a few feet away from the figure, keeping his light low so as not to shine it directly in her face.

He spoke in a calm, steady voice, telling her that they were going to get her out, that help was coming, that she was going to be okay.

He had no idea if she understood him.

Her eyes drifted toward him once, then away, focusing on nothing.

He could see now that her hands were shaking slightly and her breathing, though steady, was painfully slow.

Dererick and Ian scrambled back through the tunnels, moving faster than was safe, scraping their arms and knees on the rough stone in their hurry to reach the surface.

When they finally emerged into daylight, Dererick pulled out his phone and dialed 911.

The call was logged at 1:37 in the afternoon.

The dispatcher asked for his location and Dererick gave the coordinates as best he could, explaining that they had found someone alive in a cave and that she appeared to be in critical condition.

The dispatcher immediately contacted the Blaine County Sheriff’s Office and the local search and rescue team.

Within 20 minutes, the first responders were on route.

By the time the rescue team arrived at the site, nearly an hour had passed.

Derek and Ian led them to the cave entrance and briefed them on the route inside.

The rescue coordinator, a veteran named Phil Granger, made the decision to send in a small team first to assess the situation before attempting any kind of extraction.

Two paramedics and one technical rescue specialist entered the cave, moving as quickly as the tight passages would allow.

When they reached the chamber where Trevor was waiting, they found him still talking softly to the woman, even though she had not responded once.

The lead paramedic, a woman named Andrea Cole, knelt down beside the figure and began a preliminary assessment.

She checked for a pulse which was weak but present.

She noted the extreme malnutrition, the dehydration, the hypothermia, and the overall state of physical collapse.

Andrea later told investigators that in 15 years of emergency medicine, she had never seen anyone in such a condition who was still alive.

The woman did not resist when Andrea gently touched her arm, but she also did not respond.

Her eyes remained open, staring at nothing.

Andrea spoke to her slowly, explaining that they were there to help and that they were going to move her to a hospital.

There was no indication that the words registered.

The technical rescue specialist began setting up a system to safely transport the woman out of the cave.

They could not use a standard stretcher because of the narrow passages.

So, they fashioned a rescue sled from lightweight materials they had brought with them.

They wrapped the woman in thermal blankets to stabilize her body temperature and carefully lifted her onto the sled.

She weighed almost nothing.

Andrea estimated later that she could not have been more than 90 lb.

The extraction took more than 2 hours.

The team moved inch by inch through the tunnels, pausing frequently to adjust their grip and navigate the tightest sections.

At one point, they had to partially disassemble the sled to get it through a particularly narrow bend, then reassemble it on the other side.

The woman remained silent and motionless throughout the entire process, her eyes half closed, her breathing barely audible.

When they finally emerged from the cave, an ambulance was waiting in the clearing where Dererick had parked his truck.

The paramedics transferred the woman onto a proper stretcher and loaded her into the back of the vehicle.

Andrea rode with her, monitoring her vitals and administering in four to begin rehydration.

The woman’s condition was so fragile that Andrea was not sure she would survive the trip to the hospital.

As the ambulance sped toward Ketchum, the nearest facility equipped to handle critical cases, Derek gave his statement to the sheriff’s deputy who had arrived on scene.

He described finding the woman in the chamber, the state she was in, and the fact that there had been no supplies, no food, no water, nothing that could explain how she had survived.

The deputy asked if there had been any signs of another person in the cave.

Derek said no, it was just her alone in the dark.

At St.

Luke’swood River Medical Center, the emergency team was already prepared.

They had been briefed on the incoming patient and knew to expect someone in severe distress.

When the ambulance arrived, the woman was rushed into a trauma bay where doctors immediately began a full assessment.

They took blood samples, started multiple four lines, and began scanning for internal injuries.

What they found shocked even the most experienced physicians on staff.

The woman was severely malnourished, dehydrated to the point of organ stress, and suffering from hypothermia.

despite it being summer.

She had multiple old fractures that had healed improperly, deep lacerations that had scarred over and signs of prolonged muscle atrophy, but she was alive.

And after running her fingerprints through the state database as part of standard protocol for unidentified patients, they discovered who she was.

Rebecca Hollis, the woman who had vanished one year ago in the Sawtooth Mountains.

The identification of Rebecca Hollis sent shock waves through the hospital staff and law enforcement within minutes.

Nurses who had been working her case stopped mid task when the alert came through the system.

The attending physician, Dr.

Raymond Keller, immediately contacted the Blaine County Sheriff’s Office to inform them that the woman brought in from the cave was not just any missing hiker, but the subject of one of the most extensive and publicized searches in recent Idaho history.

Within the hour, detectives were at the hospital requesting access to her medical records and asking for updates on her condition.

Rebecca’s family was notified shortly after 6:00 that evening.

Jessica Puit received the call first from a victim advocate with the sheriff’s department.

She was told that Rebecca had been found alive, but was in critical condition and currently receiving emergency care.

Jessica broke down on the phone, unable to process what she was hearing.

She immediately called Rebecca’s parents in Oregon and they began the drive to Idaho that same night, arriving at the hospital just after midnight.

When they were finally allowed to see her, Rebecca’s mother later said she almost did not recognize her own daughter.

The woman lying in the hospital bed was skeletal, her face hollowed out, her skin pale and stretched tight over bones that seemed too prominent.

Her hair had been partially cleaned by the nurses, but it was still matted and uneven.

Her eyes were open, but they did not track movement or focus on anything.

She stared at the ceiling with the same blank expression the rescuers had seen in the cave.

Her mother sat beside the bed and held her hand, speaking softly to her, telling her that she was safe now that they were there, that everything was going to be okay.

Rebecca did not respond.

There was no flicker of recognition, no squeeze of the hand, nothing to indicate she understood or even heard the words.

Dr.

Dr.

Keller briefed the family privately in a consultation room down the hall.

He explained that Rebecca was suffering from extreme physical trauma related to prolonged starvation, dehydration, and exposure.

Her body had been operating in survival mode for an extended period, burning through muscle tissue, and depleting essential nutrients.

Her kidneys were functioning, but at reduced capacity.

Her heart rate was irregular.

She had lost nearly 40 lbs from her already lean frame.

He also explained that her mental state was a serious concern.

She was unresponsive to verbal communication, showed no emotional reaction to stimuli, and appeared to be in a dissociative state that could be the result of severe psychological trauma.

Dr.

Keller said they were running additional tests to rule out brain damage caused by malnutrition or oxygen deprivation, but initial scans had not shown any structural abnormalities.

The issue, he believed, was not physical, but psychological.

Something had happened to Rebecca in that cave.

Something that had caused her mind to retreat so far inward that she was no longer fully present in the world around her.

Over the next several days, Rebecca remained in intensive care.

Doctors work to stabilize her vital signs, slowly reintroducing nutrition through four and monitored feeding to avoid refeeding syndrome, a dangerous condition that can occur when someone who has been starved begins eating again too quickly.

Her body responded, but slowly.

She began to gain small amounts of weight.

Her color improved slightly, but her mental state did not change.

She lay in bed, eyes open, occasionally turning her head toward a sound or a light, but never speaking, never showing recognition, never truly engaging.

Investigators, meanwhile, began the process of trying to understand what had happened.

Detective Lawrence Quinn was assigned as the lead on the case.

He had been part of the original search effort a year earlier and remembered the frustration of finding absolutely nothing.

Now with Rebecca alive but unable to communicate, he faced a different kind of challenge.

He needed to reconstruct an entire year of her life with almost no information to work from.

The first step was to return to the cave where she had been found.

Quinn organized a team that included forensic specialists, a geologist, and several experienced cavers who could help document the site.

They entered the cave system on August 14th, 2 days after Rebecca’s rescue.

The team moved carefully through the passages, photographing everything, taking samples of soil and rock and mapping the layout in detail.

When they reached the chamber where Rebecca had been discovered, they set up portable lights and began a meticulous examination of the space.

What they found painted a grim picture.

The chamber itself was small and isolated with only one entry point, the narrow tunnel they had used to reach it.

There were no other passages leading out, no shafts that opened to the surface.

No source of natural light.

It was a dead end, a stone pocket buried deep in the mountain.

On the floor near where Rebecca had been sitting, they found a small collection of items.

There was a torn piece of fabric that appeared to have come from a jacket, possibly the blue one witnesses had seen her wearing on the day she disappeared.

There were also several small piles of what looked like chewed plant roots, dry and brittle, scattered near the wall.

A forensic botonist later identified them as wild tubers that grow in the forests above ground, the kind that animals sometimes dig up and store.

How they had ended up in the cave was unclear.

Against one wall, investigators found a crude arrangement of stones that seemed to have been placed deliberately to form a shallow basin.

The stones were damp and there were mineral deposits around the edges that suggested water had collected there over time.

A geologist on the team explained that groundwater often seeps through limestone and drips from the ceiling in these types of caves.

If Rebecca had figured out how to collect that water, it might explain how she had stayed hydrated enough to survive.

But it raised more questions than it answered.

How had she known to do that? How had she found the materials in complete darkness? And most disturbingly, how had she ended up in this specific chamber in the first place? The cave entrance was more than 2 mi from the Iron Creek Trail where Rebecca had last been seen.

The terrain between the trail and the cave was rugged, heavily forested, and difficult to navigate even in daylight.

There were no established paths, no markers, nothing that would have led a lost hiker in that direction.

Detective Quinn reviewed topographical maps and consulted with search and rescue experts who had worked the original case.

None of them could explain how Rebecca would have ended up so far off course.

The possibility that she had fallen into the cave by accident was considered, but the entrance was too small and too well hidden.

She would have had to know it was there.

That led investigators to a darker theory.

someone else had been involved.

Quinn began looking into reports of other incidents in the area around the time of Rebecca’s disappearance.

He pulled records of suspicious activity, trespassing complaints, and encounters with transients or squatters in the national forest.

One name appeared multiple times in ranger reports from 2016 and early 2017.

A man named Gerald Frost had been cited twice for camping in restricted areas and once for harassing hikers near Pettit Lake.

Rangers described him as a drifter in his late 40s, unckempt with a tendency to make other visitors uncomfortable.

He had been warned several times to leave the area, but kept returning.

In one report from May 2017, a ranger noted that Frost had mentioned knowing the mountains better than anyone and claimed he could disappear into places where no one would ever find him.

The last official record of Frost in the Sawtooth area was dated June 2017, 2 months before Rebecca vanished.

After that, there were no more citations, no more sightings, nothing.

Quinn flagged Frost as a person of interest and issued a request to locate him for questioning.

Local agencies were contacted, and his name was entered into state and national databases.

But as with so many elements of this case, the search led nowhere.

Gerald Frost had seemingly vanished just as completely as Rebecca had.

If you’re finding the story as unsettling as we are, consider subscribing to stay updated on cases like this.

These are real events that show just how mysterious and dangerous the wilderness can truly be.

Hit that subscribe button and turn on notifications so you don’t miss what happens next.

Back at the hospital, doctors made the decision to bring in a specialist in trauma and dissociative disorders.

Dr.

Naomi Fletcher arrived from Boise on August 18th and began working with Rebecca using techniques designed for patients who had experienced extreme psychological stress.

She sat with Rebecca for hours each day, speaking in a calm and steady voice, asking simple questions, trying to establish any threat of connection.

For the first week, there was no response.

Rebecca remained locked inside herself, her eyes open, but unseeing, her body present, but her mind somewhere far away.

Then, on the morning of August 26th, something changed.

A nurse had come in to adjust Rebecca’s four and accidentally knocked a metal tray off the bedside table.

The clatter was sharp and sudden.

Rebecca flinched.

It was a small movement, just a twitch of her shoulders and a quick turn of her head toward the sound, but it was the first voluntary reaction she had shown since being found.

Dr.

Fletcher was called immediately.

She came into the room and sat down beside the bed, speaking Rebecca’s name softly.

For the first time, Rebecca’s eyes moved toward the sound of the voice.

They did not focus completely, but there was a flicker of awareness that had not been there before.

Over the next several days, Rebecca began to emerge slowly and in fragments.

She started responding to simple commands.

When asked to squeeze a hand, she did weekly.

When asked to blink, she complied.

Her eyes began to track movement across the room.

She still did not speak, but Dr.

Fletcher noted that her level of consciousness was improving.

By early September, Rebecca was able to sit up with assistance.

She began drinking water on her own and eating small amounts of soft food.

Her physical recovery was progressing faster than her mental one, but both were moving in the right direction.

And then on September 9th, nearly a month after she had been found, Rebecca spoke.

It was just one word whispered so quietly that the nurse almost missed it.

The nurse had been adjusting her pillow when Rebecca’s lips moved.

The nurse leaned in closer and asked her to repeat it.

Rebecca’s voice was hoaro and cracked from disuse, but the word was clear.

Dark.

Dr.

Fletcher was brought in immediately, and she sat with Rebecca, encouraging her to speak again.

Over the course of that afternoon, Rebecca managed a few more words.

Pull along.

Scare.

Each word came with great effort, as if she was pulling them up from some deep place inside herself.

But they were words, and they were the first real clues to what she had endured.

In the days that followed, Rebecca’s speech slowly returned.

She began forming short sentences, though her thoughts were often fragmented and difficult to follow.

She talked about the darkness, about the cold stone, about being so thirsty she thought she would die.

She mentioned water dripping from the ceiling, and how she learned to catch it with her hands.

She described the silence so complete that she could hear her own heartbeat echoing in her ears.

But when Dr.

Fletcher asked how she had gotten into the cave.

Rebecca’s expression changed.

Her eyes went distant, her breathing quickened, and she withdrew into herself again, refusing to speak for the rest of the day.

It was clear that there were parts of her experience she either could not or would not talk about.

Detective Quinn was granted permission to speak with Rebecca once her doctors determined she was stable enough.

He kept the session brief and gentle, asking only basic questions.

Rebecca confirmed her name and said she remembered going hiking in August of the previous year.

She remembered being on the trail remembered feeling happy because the weather was nice.

But when Quinn asked what happened next, Rebecca’s hands began to shake.

She said she did not remember.

Quinn asked if anyone had been with her on the trail.

Rebecca shook her head.

He asked if she remembered how she got into the cave.

Rebecca looked at him with an expression that Quinn later described as pure terror, and she whispered, “He took me.

” Those three words changed everything.

The moment Rebecca spoke those three words, the investigation shifted from a mysterious survival story to a criminal case.

Detective Quinn immediately requested a follow-up session, but Dr.

Fletcher intervened, insisting that Rebecca was not yet strong enough for intensive questioning.

Her mental state was fragile, and pushing her too hard could cause her to retreat again into the dissociative silence she had only just begun to emerge from.

Quinn agreed to wait, but he also knew that every day that passed made it harder to find whoever was responsible.

He left the hospital that afternoon and returned to his office to begin building a case based on the limited information they had.

The statement Rebecca had made, brief as it was, was enough to open a formal investigation into suspected kidnapping and unlawful imprisonment.

Quinn pulled together a task force that included two other detectives, a forensic psychologist, and a liaison from the FBI’s violent crimes unit.

They began by revisiting everything they knew about the day Rebecca disappeared.

They reintered the couple who had seen her on the trail, asking if they had noticed anyone else in the area that morning.

The couple remembered seeing a few other hikers farther down the trail, but no one who stood out as suspicious.

They were shown a photograph of Gerald Frost, the transient who had been flagged earlier.

Neither of them recognized him.

Quinn expanded the search to include anyone who had been cited, questioned, or reported in the Sawtooth area during the summer of 2017.

He cross-referenced names with criminal databases looking for individuals with histories of violence, abduction, or erratic behavior.

Frost remained the strongest lead, but there were others.

A man named Donald Wyatt had been arrested in 2015 for assault in Haley and had a known history of living off the grid in the mountains.

Another individual, Carl Venner, had been reported by campers for watching them from a distance and following them on trails near Stanley Lake.

Both men were located and questioned.

Wyatt had an alibi for the time of Rebecca’s disappearance, confirmed by his parole officer.

Venner had moved to Nevada in early 2017 and had not returned to Idaho since.

Neither of them matched the profile Quinn was building.

Meanwhile, forensic teams continued processing evidence from the cave.

Soil samples, fabric fragments, and the plant material found near Rebecca were sent to the state lab for analysis.

The results came back in midepptember.

The fabric was confirmed to be from the jacket Rebecca had been wearing the day she vanished.

The plant material was identified as bitterroot and wild onion, both of which grow in the forests around the Sawtooth Mountains.

More significantly, the lab found trace DNA on one of the fabric samples that did not belong to Rebecca.

It was male DNA, degraded and partial, but enough to enter into the national database.

The search came back with no matches.

Whoever the DNA belonged to, he was not in the system.

That meant he had no prior criminal record, at least not one that required a DNA sample.

It was a frustrating dead end, but it also confirmed what Rebecca had said.

Someone else had been involved.

Quinn returned to the hospital in late September with Dr.

Fletcher’s approval to conduct a more detailed interview.

Rebecca was sitting up in bed when he arrived, her color better than it had been weeks earlier, though she still looked painfully thin.

Her hair had been cut short by the hospital staff to remove the damaged and matted sections, and she wore a simple hospital gown.

Her eyes, once vacant, now held a weary awareness.

Quinn sat down in a chair beside her bed and spoke in a calm, unhurried voice.

He explained that he was trying to understand what had happened to her so that he could find the person responsible.

He told her she did not have to answer anything that made her uncomfortable, but that anything she could remember would help.

Rebecca nodded slowly.

Quinn started with simple questions.

Did she remember leaving the trail head on August 14th? Yes.

Did she remember hiking alone? Yes.

Did she remember seeing other people on the trail? She hesitated, then said she thought so, but could not remember faces.

Quinn asked her to describe the last thing she remembered before waking up in the cave.

Rebecca closed her eyes and took a slow breath.

She said she had been walking uphill, enjoying the quiet, when she decided to step off the trail briefly to take a photograph of the valley below.

She moved toward a rocky ledge, careful to watch her footing.

She remembered crouching down to get a better angle with her phone, and then she said she heard something behind her, the sound like footsteps on gravel.

She turned around and that was when everything went black.

She did not remember being hit or falling.

She just remembered the sensation of the world disappearing.

When she woke up, she was in complete darkness.

She could not see anything.

She tried to move and realized her hands were tied behind her back with something rough, maybe rope or cord.

Her head was pounding and she felt sick.

She called out, but her voice just echoed back at her.

No one answered.

She did not know how long she lay there.

It could have been hours or days.

Time had no meaning in the dark.

Eventually, she heard movement again.

Footsteps, slow and deliberate, coming closer.

She tried to speak to ask who was there to beg for help.

A voice answered low and quiet telling her not to scream.

She asked where she was and the voice said she was safe.

She asked to be let go and the voice said she would be eventually but not yet.

Rebecca’s hands trembled as she recounted this.

Quinn asked if she ever saw the person’s face.

She shook her head.

He only came when it was dark or maybe it was always dark.

She could not tell.

She never saw him clearly, only sensed his presence.

Quinn asked what happened next.

Rebecca said the man brought her water.

He held a container to her lips and let her drink.

It tasted strange, metallic, but she was so thirsty she did not care.

He also brought her food, small pieces of something she could not identify.

It was bitter and tough, but she ate it because she was starving.

He untied her hands at some point.

She did not remember when, but warned her not to try to leave.

He said the cave was dangerous, that there were drops and tunnels that went nowhere, and if she wandered off, she would fall and die.

She believed him because she could feel the emptiness around her, the way sound traveled and disappeared into nothing.

Rebecca said she tried to keep track of time by counting, but she kept losing count.

She tried to stay awake to listen for any clue about where she was or who he was, but exhaustion overwhelmed her.

She would fall asleep and wake up disoriented, unsure if minutes or days had passed.

The man came and went without pattern.

Sometimes he stayed and talked to her, his voice always calm, almost kind.

He told her that the world above was chaotic and dangerous, that people were cruel and selfish.

He said she was better off here where it was quiet, where no one could hurt her.

Rebecca said she argued with him at first, told him he was wrong, that people were looking for her, that she wanted to go home.

He did not get angry.

He just said she would understand eventually.

As time went on, Rebecca said she stopped arguing.

She stopped asking to leave.

She stopped thinking about the world above.

All that mattered was the next drink of water, the next scrap of food, the next moment of sleep.

She forgot what daylight looked like.

She forgot the faces of her family and friends.

She forgot her own name for a while.

She became nothing but a body in the dark, breathing and waiting.

Quinn asked if the man ever heard her physically.

Rebecca paused for a long time before answering.

She said he never hit her or touched her inappropriately, but he controlled everything.

When she ate, when she drank, whether she lived or died.

That control, she said, was its own kind of violence.

Dr.

Fletcher, who was present during the interview, gently suggested they take a break.

Rebecca was visibly exhausted, her breathing shallow, her eyes wet with tears she had not let fall.

Quinn thanked her and said they could continue another time.

As he stood to leave, Rebecca spoke again, her voice barely above a whisper.

She said the man told her once that he had saved her, that he had pulled her back from the edge of the world and given her a gift, the gift of silence, the gift of disappearing.

Quinn asked if the man ever mentioned his name.

Rebecca shook her head, but she said he smelled like smoke and earth and his hands were rough like someone who worked outside.

It was not much, but it was something.

After leaving the hospital, Quinn returned to the evidence board in his office and added Rebecca’s descriptions to the timeline.

He focused his attention back on Gerald Frost.

According to Ranger reports, Frost had been known to camp illegally in the area, which meant he spent significant time outdoors.

He would have had rough hands.

He would have smelled like smoke from campfires.

And most importantly, he had demonstrated knowledge of the mountains that most people did not have.

Quinn put out an urgent request to locate Frost, emphasizing that he was now a primary suspect in a kidnapping case.

Alerts were sent to law enforcement agencies across Idaho, Oregon, Washington, and Montana.

Frost’s photograph, taken from an old citation report, was distributed to media outlets with a request for the public’s help.

Tips began coming in within days.

A gas station attendant in Shalice reported seeing a man matching Frost’s description in late August, just after Rebecca had been found.

A campground host near Stanley said someone fitting his profile had stayed there briefly in early September, but had left without paying.

Each lead was followed up, but none of them led to Frost himself.

It was as if he knew he was being hunted and had gone even deeper into hiding.

Investigators also revisited the cave, this time with cadaavver dogs and ground penetrating equipment, searching for any sign that Frost or anyone else had used the area as a long-term base.

They found nothing conclusive, but a secondary passage previously overlooked was discovered branching off from the main chamber.

It led to another small cavity that contained a few items.

An old tarp, a rusted canteen, and a pair of worn boots.

The boots were sent for analysis, and the tread pattern was compared to Prince found near the cave entrance.

They matched.

Quinn felt the case tightening.

Everything pointed to someone who knew the land, who had the ability to move unseen, and who had kept Rebecca alive in conditions that should have killed her.

The question was no longer whether someone had taken her.

The question was whether they would find him before he disappeared completely.

Investigators working the case knew they were running out of time.

Frost, if it was him, had already proven he could vanish into the wilderness, and if he did, they might never get answers.

Rebecca, meanwhile, continued her recovery.

She was moved out of intensive care and into a psychiatric unit where she could receive more specialized support.

Her family visited daily, and slowly, painfully, she began to reconnect with the life she had lost.

But the shadow of the cave remained.

She still woke up in the night thinking she was back in the darkness.

She still flinched at loud sounds and struggled to be in enclosed spaces.

The doctor said it would take years, maybe a lifetime, to fully process what she had endured.

And through it all, one question haunted everyone involved.

Why had he let her live? The question of why Rebecca had been kept alive instead of killed, nod at Detective Quinn every day.

In most abduction cases he had worked, the captor either released the victim quickly or the outcome was fatal.

But Rebecca had been held for nearly a year in conditions that were barely survivable.

Cared for just enough to keep her breathing, but not enough to let her thrive.

It suggested a purpose, a reason that went beyond impulse or opportunity.

Quinn believed that understanding that purpose was the key to finding the man responsible.

He returned to the cave one more time in early October.

This time alone, wanting to see the space without the noise of a full investigative team.

He descended through the narrow passages with only a headlamp and a notebook, retracing the route the rescuers had taken.

When he reached the chamber where Rebecca had been found, he sat down on the cold stone floor and tried to imagine what it had been like for her.

The silence was absolute.

No wind, no birds, no distant hum of civilization.

Just the faint drip of water somewhere in the dark and the sound of his own breathing.

He understood then in a way he had not before how a person could lose themselves in a place like this.

How time could dissolve, how the mind could fracture under the weight of so much nothing.

He also understood how someone could use that emptiness as a weapon.

Quinn stood up and examined the chamber again, this time looking for anything the forensic team might have missed.

He noticed scratch marks on the wall near where Rebecca had been sitting, faint lines carved into the limestone.

They were deliberate, grouped in sets of five, the way prisoners in old stories marked the days.

He counted them.

There were over 200 marks.

That meant Rebecca had tried at least for a while to keep track of time.

But the marks stopped abruptly about halfway down the wall, as if she had given up or forgotten why she was counting.

Quinn took photographs and added them to the case file.

Back at his office, he compiled everything they knew about Gerald Frost.

Frost was 48 years old, originally from Boise with a history of odd jobs and transient living.

He had worked as a landscaper, a construction laborer, and briefly as a park maintenance worker before being let go for unspecified behavioral issues.

He had no violent criminal record, but he had been flagged multiple times for trespassing and disturbing the peace.

People who had encountered him described him as quiet, intense, and unsettling.

One former co-orker said Frost talked constantly about self-sufficiency and living off the land.

He believed modern society was a trap and that most people were too weak to survive without it.

He had once told the co-worker that he could live underground for months if he had to, that he had done it before and would do it again.

Quinn cross referenced that statement with reports of missing persons in Idaho over the past decade.

He found three cases that shared similarities with Rebecca’s disappearance.

In 2011, a 23-year-old woman named Amy Callahan vanished while hiking near Craters of the Moon National Monument.

She was never found.

In 2014, a 30-year-old man named Justin Alder disappeared during a solo camping trip in the Bitterroot Range, also never found.

And in 2016, a 27-year-old woman named Vanessa Bright went missing after leaving her car at a trail head near Sun Valley.

Her case remained open and unsolved.

Quinn requested the files on all three cases and began looking for connections.

Amy Callahan’s disappearance had occurred in an area where Frost was known to have camped.

Justin’s last known location was near a Forest Service road that Frost had been cited on just months earlier.

Vanessa Bright had vanished less than 20 m from where Rebecca was found.

It was circumstantial, but the pattern was there.

Quinn briefed his superiors and formally requested that the FBI’s behavioral analysis unit review the cases.

If Frost was responsible for multiple abductions, he was not just a drifter.

He was a serial offender.

And Rebecca might be the only victim who had survived.

The FBI assigned an agent named Laura Inisfield to assist with the investigation.

She arrived in Ketchum in mid-occtober and immediately began working with Quinn to develop a profile.

Based on Rebecca’s account and the evidence from the cave, Enesfield concluded that the offender was highly organized, patient, and motivated by a need for control rather than sexual gratification.

She believed he selected victims who were alone and vulnerable, people he could remove from society without immediate detection.

The fact that he kept Rebecca alive suggested he saw her as a project, someone he was testing or teaching.

Enesfield theorized that he might have released previous victims after shorter periods or that Rebecca had been an experiment in endurance.

Either way, she said he would not stop unless he was caught or killed.

The media coverage of Rebecca’s case intensified in late October when a local news station aired an interview with her family.

Her mother spoke tearfully about the year they had spent not knowing if Rebecca was alive or dead and about the relief and heartbreak of having her back, but seeing how much she had suffered.

The story was picked up by national outlets and within days, Rebecca’s face was on television screens across the country.

The increased attention brought in a flood of new tips.

People reported seeing men who looked like Gerald Frost in campgrounds, truck stops, and rural areas throughout the Northwest.

Each tip was investigated, but none led to a confirmed sighting.

Then on November 3rd, a hiker in the Salmon Chalice National Forest found something that changed the trajectory of the investigation.

He was walking along an old logging road when he noticed a smell coming from a dense thicket of trees.

Curious and concerned, he pushed through the brush and found a makeshift campsite.

There was a torn tent, scattered supplies, and a sleeping bag laid out on the ground.

Next to the sleeping bag was a body.

The hiker immediately called 911, and Forest Service rangers arrived within the hour.

The body was male, estimated to be in his late 40s or early 50s, and had been dead for at least several weeks.

There were no obvious signs of trauma, no wounds or injuries that would indicate foul play.

The man appeared to have died of natural causes, possibly exposure or a medical event.

His identification was found in a waterproof pouch near the tent.

It was Gerald Frost.

Detective Quinn was notified immediately and drove to the site that same afternoon.

He stood over the body, looking down at the man he had been hunting for months, and felt a complicated mix of relief and frustration.

Relief that Frost could not hurt anyone else.

Frustration that he would never face trial, never be forced to answer for what he had done.

The medical examiner conducted an autopsy and determined that Frost had died of a heart attack, likely brought on by physical stress and poor health.

Toxicology results showed no drugs or alcohol in his system.

He had simply collapsed and died alone in the woods, the same woods he had used to hide from the world.

Among his belongings, investigators found items that directly linked him to Rebecca.

There was a small notebook containing entries written in Frost’s handwriting.

The entries described his philosophy of isolation, his belief that people needed to be stripped of their distractions and comforts to understand their true nature.

He wrote about a woman he called the student, describing how he had taken her from the trail and brought her to a place where she could learn what it meant to exist without dependency.

He wrote that she had resisted at first but eventually surrendered, proving his theory that anyone could adapt to the void if they had no other choice.

He also wrote about his failing health, noting that his chest hurt frequently and that he was growing weaker.

In one of the final entries dated late August, he wrote that he had decided to leave the student in the chamber because he knew he would not be able to care for her much longer.

He wrote that she had already learned enough and that whether she survived or not was no longer his concern.

It was a cold, detached admission that made Quinn’s stomach turn.

The notebook was entered into evidence and its contents were shared with Rebecca’s legal team and therapist.

Dr.

Fletcher made the decision not to show it to Rebecca directly, at least not yet, but she did tell her that the man who had taken her was dead and that she was safe.

Rebecca’s reaction was muted.

She nodded, asked no questions, and turned her face toward the window.

Later, she told Dr.

Fletcher that she did not feel relief or closure.

She said she just felt empty, like a part of her was still in the cave and always would be.

With Frost’s death, the criminal case effectively closed.

There would be no trial, no conviction, no public reckoning.

The district attorney issued a statement confirming that Gerald Frost was identified as the primary suspect in the abduction and unlawful imprisonment of Rebecca Hollis and that his death had concluded the active investigation.

The cases of Amy Callahan, Justin, and Vanessa Bright were reopened, and investigators began searching areas where Frost was known to have camped, looking for any sign of additional victims.

As of the end of 2018, no remains had been found, but the searches continued.

Rebecca remained in treatment throughout the fall and into the winter.

Her physical recovery progressed steadily.

She regained most of the weight she had lost.

Her strength returned, and the medical complications from malnutrition gradually resolved.

Her psychological recovery was slower and more complicated.

She suffered from severe PTSD with symptoms that included flashbacks, nightmares, hypervigilance, and an acute fear of darkness, and confined spaces.

She worked with Dr.

Fletcher several times a week using a combination of cognitive behavioral therapy and exposure techniques to help her process the trauma.

If this story has affected you the way it has affected so many others, please take a moment to like this video and share it.

Stories like Rebecca’s need to be told, not just to inform, but to remind us of the resilience of the human spirit and the importance of never giving up.

Your support helps us continue bringing these accounts to light.

In early 2019, Rebecca moved back to Oregon to live with her parents.

She was not ready to return to her old life in Boise, and her doctors agreed that being close to family was the best environment for her continued healing.

She enrolled in outpatient therapy and slowly began rebuilding her routine.

She started drawing again, something she had loved before the abduction, and found that it helped her express things she could not put into words.

Her family described small victories.

The first time she laughed at something on television, the first time she went for a walk outside without panicking, the first time she slept through the night without waking up screaming.

These moments were fragile and hard one, but they were real.

Rebecca also began speaking cautiously about her experience, not to the media, but in private sessions with other survivors of trauma.

Dr.

Fletcher connected her with a support group for individuals who had survived abduction or prolonged captivity.

And Rebecca found some comfort in knowing she was not alone.

In one group session, she said that the hardest part was not the hunger or the cold or even the fear.

It was the loss of time.

She said she would never get that year back, and she would never fully understand what it had taken from her.

Detective Quinn retired from the Blaine County Sheriff’s Office in the summer of 2019.

In his final interview with a local newspaper, he was asked about the cases that had stayed with him the most.

He mentioned Rebecca without hesitation.

He said her survival was a testament to the strength of the human will, but also a reminder of how much darkness exists in the world, even in places that seem safe and beautiful.

He said he thought about her often and hoped she found peace.

The Saut Mountains remain a popular destination for hikers and outdoor enthusiasts.

The cave where Rebecca was held has been sealed off by the Forest Service, marked as unsafe and offlimits to the public.

But those who know the story still talk about it in quiet voices around campfires and in the lodges that dot the region.

They talk about the woman who disappeared and the year she spent in the dark.

They talk about the man who put her there and the twisted logic that drove him.

And they talk about the thin line between survival and surrender and how close Rebecca came to crossing it.

Rebecca Hollis is alive today, but she carries the cave with her wherever she goes.

In interviews conducted years later, she described it as a weight she had learned to live with.

Not something that could be removed, but something that could be managed.

She said there are still nights when she wakes up and for a brief terrible moment she thinks she is back in the darkness sitting against the stone waiting for a sound that never comes.

But then she opens her eyes and sees light and she remembers that she made it out.

She survived.

The case of Rebecca Hollis remains one of the most disturbing abduction cases in Idaho history.

It is studied by law enforcement agencies as an example of how predators can operate in remote areas with near total impunity and how victims can endure unimaginable conditions and still come back.

It is also a reminder that some questions never get answered.

Why did Gerald Frost choose Rebecca? Why did he keep her alive for so long? What did he hope to prove? Those answers died with him in the woods and Rebecca was left to make sense of the pieces he left behind.

But she is making sense of them slowly, painfully, one day at a time.

And in that persistence, in that refusal to let the darkness define her, there is something that resembles hope.

The mountains are still there.

The trails are still walked.

And somewhere in Oregon, a woman who once disappeared is learning step by step how to be found

News

Ilhan Omar ‘PLANS TO FLEE’…. as FBI Questions $30 MILLION NET WORTH

So, while Bavino is cracking down in Minnesota, House Republicans turning the heat up on Ilhan Omar. They want to…

FBI & ICE Raid Walz & Mayor’s Properties In Minnesota LINKED To Somali Fentanyl Network

IC and the FBI move on Minnesota, touching the offices of Governor Tim Walls and the state’s biggest mayors as…

FBI RAIDS Massive LA Taxi Empire – You Won’t Believe What They Found Inside!

On a Tuesday morning, the dispatch radios in hundreds of Los Angeles taxi cabs suddenly stopped playing route assignments. Instead,…

Brandon Frugal Finally Revealed What Forced Production to Halt in Season 7 of Skinwalker Ranch….

The Secret of Skinwalker Ranch became History Channel’s biggest hit. Six successful seasons documenting the unknown with real science and…

1 MINUTE AGO: What FBI Found In Hulk Hogan’s Mansion Will Leave You Shocked….

The FBI didn’t plan to walk into a media firestorm, but the moment agents stepped into Hulk Hogan’s Clearwater mansion,…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage… It started like any other evening…

End of content

No more pages to load