How One Girl’s “Stupid” String Trick Exposed a Secret German Submarine Base Hidden for Years

September 11th, 1943.

The coastal village of Bergen, Norway, sat beneath a gray autumn sky.

Its wooden houses clinging to the rocky shoreline like barnacles on a ship’s hull.

14-year-old Astred Nielson stood at her bedroom window, watching German supply trucks rumble past her family’s bakery.

For the third time that morning, their wheels splashing through puddles left by the previous night’s rain.

The soldiers believed they had hidden their greatest secret in plain sight.

that the curious eyes of a Norwegian girl posed no threat to their elaborate deception.

They could not have been more wrong.

What Astrid would discover through nothing more than baker’s twine and a child’s curiosity would unravel one of the most sophisticated concealment operations on the Norwegian coast, exposing a facility that the German military had invested millions of Reichkes marks and thousands of work hours to keep invisible.

Astrid had lived in Bergen her entire life, watching the seasons change over the harbor, memorizing the rhythms of the fishing boats and merchant vessels that defined the city’s heartbeat.

But since April 1940, when German forces occupied Norway, those rhythms had changed.

Her father, Henrik Nielson, still ran the family bakery on Strandgarten Street, but now he baked bread primarily for German personnel stationed throughout the city.

The family had learned to survive through silence and observation, skills that Astrid had developed into something resembling an art form.

The girl possessed what her grandmother called noticing eyes.

While other children played in the streets, Astrid cataloged patterns.

She knew that Lieutenant Verer’s staff car always arrived at exactly 7:15 each morning.

She recognized the difference between transport trucks carrying food supplies versus those weighted down with something far heavier.

She had memorized which German soldiers would accept a friendly greeting, and which ones kept their hands perpetually near their sidearms.

But lately, Astrid had noticed something that made no sense.

Every Tuesday and Friday, between the hours of 10:00 in the evening and 2:00 in the morning, a convoy of 6 to eight trucks would drive north out of the city, their headlights dimmed to narrow slits.

She knew they drove north because her bedroom faced that direction and she could track their faint lights as they wound along the coastal road toward Herdler Island.

What puzzled her was simple arithmetic.

The trucks that departed Bergen were heavily loaded, their suspensions compressed, their engines straining, but when they returned 4 hours later, they appeared just as heavy.

Astrid mentioned this observation to her father one morning while shaping dough for the day’s loaves.

Henrik listened carefully, his flowercovered hands never pausing in their work, then spoke quietly.

“Perhaps they are transferring cargo from one facility to another,” he suggested, though his eyes held the same confusion his daughter felt.

“But why would loaded trucks return still loaded?” Astrid pressed.

“If they were delivering supplies somewhere, they should come back empty, or at least lighter.

” Her father had no answer, but he did have a warning.

Whatever the Germans are doing, it is not our concern.

These are dangerous times for the curious Astrid, especially for young girls who ask too many questions.

She nodded obediently, but the puzzle had already taken root in her mind.

For 2 weeks Astrid observed the Tuesday and Friday convoys, and her confusion only deepened.

The trucks traveled the same route, maintained the same schedule, and demonstrated the same inexplicable weight pattern.

Finally, her methodical nature demanded a solution.

If she could not solve the mystery through observation alone, she would need to gather physical evidence.

The idea came to her while helping her mother repair a ripped flower sack.

They used heavy baker’s twine to reso the burlap.

And as Astrid watched her mother’s needle pull the string through the fabric, inspiration struck with the clarity of a bell.

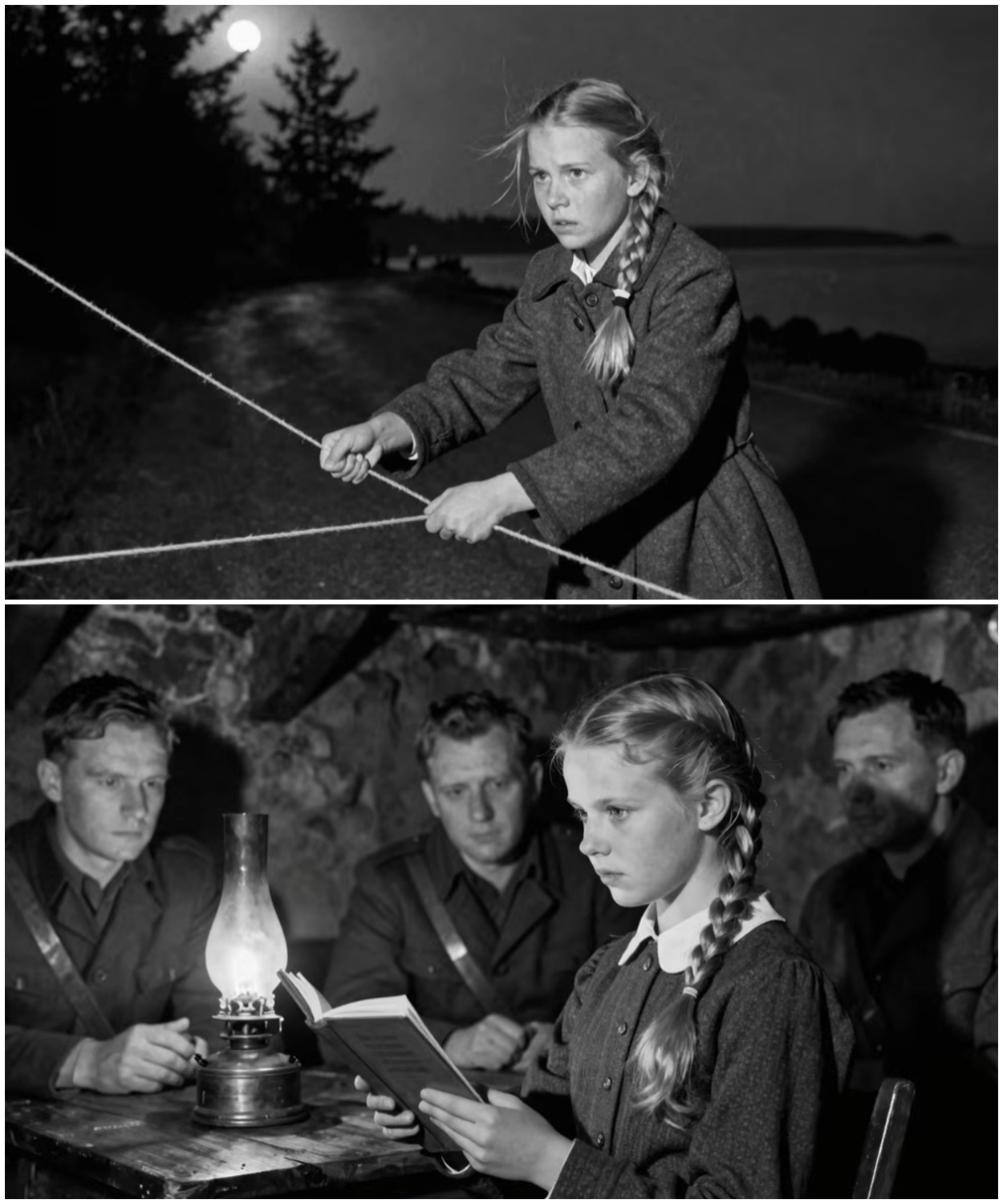

On the following Tuesday evening, October 5th, Astrid waited until her parents were asleep, then slipped out of her bedroom window, a spool of thin but strong baker’s twine tucked into her coat pocket.

The autumn night was cold and moonless, perfect for her purposes.

She made her way to a narrow section of the coastal road about half a kilometer north of her house, where the route curved around a rocky outcrop before continuing toward Herdler Island.

Working quickly in the darkness, Astrid tied one end of the twine to a sturdy pine tree on the eastern side of the road, then stretched it across to a birch on the western side, securing it about 1 m above the ground.

She cut the string and hurried home, her heart pounding, not from exertion, but from the audacious simplicity of her plan.

The next morning, Astrid retraced her route.

The twine on the eastern side remained knotted to the pine tree exactly as she had left it, but the western end, which she had tied to the birch tree, had vanished.

The string had been cut or broken approximately 2 m from the birch.

She examined the severed end carefully.

It showed a clean break, as if something had caught it, and snapped it with considerable force.

More importantly, the direction of the break suggested that whatever cut the string had been traveling from Bergen toward Herdler, not returning.

This made no sense at all.

Astrid had watched the convoy depart Bergen the previous night.

She had seen the trucks head north.

If those same trucks had cut her string while traveling north toward Herdler, then returned south back to Bergen, the string should have been cut in both directions, but it had only been severed on the northbound side, unless the trucks never came back.

The realization hit her with such force that she actually gasped aloud.

The trucks she saw returning to Bergen on Wednesday mornings were not the same trucks that departed on Tuesday nights.

They could not be.

Different trucks were leaving Bergen heading north and different trucks were returning to Bergen from the north.

But they all looked identical because they were all German military vehicles of the same model and color.

But why why would the Germans need to maintain this elaborate shuttle? what could possibly require loaded trucks to travel north while other loaded trucks traveled south all through the dark hours of the night.

Astrid’s next experiment was Boulder.

The following Friday, October 8th, she placed strings at three different locations along the northern road, each one carefully positioned, and each one marked with a small knot pattern that would tell her exactly which string had been cut and from which direction.

She also added something new.

At each location, she rubbed charcoal dust along a section of the string.

If a vehicle’s axle or undercarriage cut the string, some charcoal might transfer to the metal.

Saturday morning’s inspection provided even more confusing data.

All three strings heading north had been cut, but the strings spanning the southbound lane had also been cut, and the brake patterns showed impacts from both directions at different heights.

Some brakes were roughly 1 m high, as expected from a truck’s front axle, but others were higher, approximately 1.

5 m, and showed a different pattern entirely.

Astrid brought the severed string pieces home and examined them under her father’s magnifying glass, the one he used to read small print on supply invoices.

On two of the strings, she found traces of what appeared to be rust and a peculiar greenish residue.

She had seen that exact color before on the bronze fittings of fishing boats in the harbor.

The pieces began assembling in her mind like a puzzle.

Trucks traveling north, trucks traveling south, different heights, bronze residue, and always during the darkest hours when observation was most difficult.

She needed to see the convoy up close, but that presented obvious dangers.

German soldiers did not treat Norwegian civilians kindly when they encountered them near military operations, and a teenage girl wandering alone at night would attract exactly the wrong kind of attention.

Astrid needed an excuse, a reason to be on that road that would seem innocent and unquestionable.

The solution came from an unexpected source.

Her mother’s sister, Aunt Ingred, lived in a small farmhouse approximately 3 km north of Bergen, directly along the route the convoys traveled.

Ingred had recently broken her ankle in a fall, and Astrid’s mother visited her twice weekly, bringing bread and helping with household tasks.

“Mother,” Astred said on Sunday evening, “I would like to visit Aunt Ingred this Tuesday.

I could bring her the honey cakes she loves, and perhaps read to her.

You have so much work at the bakery and I know you are tired.

Her mother looked surprised but pleased.

That is very thoughtful, Astred, but Tuesday evening.

Would it not be better to visit in daylight? I have school until late.

Astrid improvised quickly.

And Aunt Ingred always says she feels most lonely at night.

I could walk there after dinner and return Wednesday morning before school.

You know she has that spare bedroom.

After some discussion, her parents agreed.

Tuesday evening, October 12th, Astrid set out for her aunt’s farm, a small rucks sack on her back containing honey cakes, a book, and her spy glass, a small brass telescope her grandfather had given her years before.

Aunt Ingrid welcomed her warmly, asking no questions about the unusual timing of the visit.

They shared tea and cakes, discussing village gossip and Ingred’s slow recovery.

Around 9:30, Astrid excused herself, claiming tiredness, and retired to the spare bedroom.

She did not sleep.

Instead, she waited by the darkened window, her spy glass ready, her notebook open.

At 10:45, she heard them coming.

The deep rumble of heavy engines, the particular squeal of military truck brakes that needed greasing.

Astrid raised her spy glass and watched.

The convoy consisted of seven trucks, exactly as she had previously counted.

They moved slowly along the road, their dimmed headlights creating just enough illumination to navigate.

The trucks were covered with canvas tarps, their cargo areas concealed.

But as they passed directly in front of her aunt’s farmhouse, Astrid noticed something she had never been able to see from her bedroom window in Bergen.

The truck sat low on their suspensions, very low.

Whatever they carried was extraordinarily heavy.

She estimated each truck’s cargo at several tons based on how the vehicles handled the slight curves in the road.

Steel perhaps or concrete building materials of some kind.

She made careful notes of everything, the time, the number of vehicles, their approximate speed, the depth of their tire tracks in the soft shoulder of the road.

Then she waited.

If her theory was correct, more trucks would come from the opposite direction within the next few hours.

At 1:15 in the morning, she heard engines again.

Astrid pressed her face to the window, her spy glass raised, but what she saw made her breath catch in her throat.

These were not trucks, or rather, they were trucks, but they had been modified so extensively that they barely resembled standard military vehicles.

The cargo beds had been completely enclosed with metal housings, and the suspensions had been reinforced with additional springs and supports.

Most strikingly, each truck towed a large enclosed trailer, also sitting very low on heavyduty wheels.

Seven of these unusual vehicles passed the farmhouse, heading south toward Bergen, moving even more slowly than the northbound convoy had.

They traveled in precise formation, maintaining exact distances from one another, and they made almost no sound beyond the rumble of engines.

Someone had gone to considerable effort to muffle the mechanical noise.

Astrid wrote frantically, sketching the vehicle’s configurations, noting every detail she could observe.

When the last modified truck disappeared around the southern bend, she remained at the window, her mind racing through possibilities.

The Germans were transporting something very heavy from Bergen northward to some location near Hurdler Island.

They were then loading something equally heavy onto specialized vehicles and bringing it back south to Bergen.

This happened twice weekly every Tuesday and Friday with the precision of a railroad schedule, and someone had invested significant resources into keeping this operation as quiet and invisible as possible.

But what could require such elaborate secrecy? What cargo was so valuable and so sensitive that it justified this complicated shuttle system? The answer came to her 3 days later during an ordinary conversation with an extraordinary witness.

Astrid’s father employed a delivery boy named Lars, a 16-year-old Norwegian youth who helped distribute bread to German facilities throughout Bergen.

Lars was simple-minded, as the villagers politely described him, but he possessed an encyclopedic memory for roots, addresses, and physical locations.

He could remember every building he had ever entered and every face he had ever seen, though he struggled with abstract concepts and complex instructions.

On Friday morning, while Lars helped load bread racks into the delivery cart, Astrid asked him casually, “Lars, do you ever deliver to the facilities north of the city toward Herdler?” Lars nodded enthusiastically.

“Oh yes, twice each week I bring bread to the big doors that go into the mountain.

The soldiers there are very serious.

They check my cart three times before they let me enter.

Astrid felt her pulse quicken.

Doors that go into the mountain? What do you mean? The mountain has doors, Lars explained with the patience of someone describing something obvious.

Very large doors made of steel.

They open and inside is a tunnel that goes deep into the rock.

I deliver bread to the kitchen area which is just inside the entrance.

I am not allowed to go farther.

There are many soldiers with weapons who watch everything.

How many soldiers? Astrid asked, trying to keep her voice casual.

Lars thought carefully, his face scrunching with concentration.

I have counted 43 different soldiers at the entrance facility, but I hear many more voices from deeper in the tunnel, perhaps hundreds.

And I hear machines, very loud machines that echo in the rock.

Henrik Nielson, who had been listening to this conversation while kneading dough, gave his daughter a sharp warning look, but Astrid could not stop now.

She was too close.

“Lars,” she said gently.

“What kind of machines?” “What do they sound like?” “Like the pumps at the harbor,” Lars replied immediately.

“The big pumps they use to move water out of ships that have leaks.

That whooshing, gurgling sound and also like metal being dragged on stone.

Scraping hand voices shouting numbers in German.

Dry meter, funf meter.

Like that.

3 m, 5 m, depths.

Astrid realized they were measuring depths.

The final piece clicked into place with the weight of absolute certainty.

The Germans had built a submarine base inside the mountain on Herdler Island.

The trucks traveling north carried construction materials, supplies, and possibly munitions.

The specialized vehicles traveling south transported something that had been inside the mountain facility, something that needed to be moved back to Bergen for processing or shipping.

But submarines did not travel on trucks, no matter how heavily reinforced.

So what were they moving? That night, Astrid could not sleep.

She lay in her bed, listening to the October wind rattle her window, and thought about submarines.

She knew they needed supplies, fuel, food, fresh water, spare parts, munitions.

She knew they needed repairs and maintenance, and she knew that German submarines operating in the North Atlantic were engaging Allied convoys, trying to cut Britain’s supply lines.

If the Germans had indeed built a hidden submarine base in the mountains near Hurdler, it would be a strategic facility of enormous importance.

Submarines could enter the base through underwater tunnels, be serviced and resupplied in complete concealment from Allied aircraft, then returned to the North Atlantic without ever surfacing in observable waters.

But this created a logical problem.

Submarines needed certain supplies that could not be manufactured locally.

specialized lubricants, precision instruments, radio equipment, and most crucially, munitions.

These materials would need to come from Germany itself, transported by ship or rail to Bergen, then moved to the hidden facility, except that regular supply convoys to Hurdler Island would attract attention.

Allied intelligence networks in Norway were extensive, and the British knew that any significant German naval facility would become a priority target.

So the Germans had devised this elaborate deception.

They disguised the supply route as something ordinary, splitting the cargo across two different convoys traveling in opposite directions.

Using the cover of darkness and modified vehicles to minimize observation, Astrid realized she needed proof, something more substantial than string experiments and secondhand observations from a simple-minded delivery boy.

She needed evidence that would convince the Norwegian resistance movement.

The underground network she knew existed, even though no one spoke of it directly.

Her opportunity came 2 weeks later when the October weather turned unusually cold and the harbor waters began to freeze at night.

Astrid’s mother asked her to deliver bread to Aunt Ingrid again, concerned that the elderly woman might be struggling with frozen water pipes.

Astrid agreed immediately, but this time she had a specific plan.

She would not simply observe the convoys from her aunt’s window.

She would follow them.

On Tuesday evening, October 26th, Astrid arrived at her aunt’s farm an hour before sunset.

She shared dinner with Ingrid, helped her with evening chores, and then retired to the spare bedroom.

But instead of changing into night clothes, she dressed in her warmest dark clothing, packed a small bag with her notebook, spy glass, and a thermos of hot tea, and waited.

At 10:30, she slipped out of the farmhouse, and made her way to a position she had selected during her previous visit, a rocky outcrop about 200 m from the road, elevated enough to provide a clear view while offering concealment among the boulders and low pine trees.

The northbound convoy arrived at 10:50, exactly on schedule.

Astrid watched through her spy glass as the seven trucks rumbled past, their heavy loads evident in every labored gear change.

When the last vehicle disappeared around the northern curve, she began following on foot.

The terrain was rough, but Astrid had grown up hiking these coastal hills.

She knew how to move quietly through the woods, how to avoid loose rocks and crackling underbrush.

She maintained a parallel course to the road, staying far enough away to remain hidden, but close enough to track the convoy’s progress by sound and occasional visual confirmation.

After approximately 45 minutes of hiking, Astrid reached a ridge that overlooked Herdler Island.

The island connected to the mainland by a narrow causeway, and as she watched, the convoy approached a checkpoint at the causeway’s entrance.

German soldiers inspected each truck briefly, then waved them through.

The trucks proceeded across the causeway and disappeared behind a rocky hill on the island’s southern side.

Astrid needed to get closer, but the terrain here was more exposed, offering less cover.

She would have to take a risk.

Moving carefully in the darkness, she made her way down the ridge toward the causeway, using every available shadow and depression in the landscape.

The process took nearly 30 minutes, but eventually she reached a position on the mainland side where she could observe the island through her spy glass.

What she saw confirmed everything she had theorized and introduced several details she had not anticipated.

The rocky hill that had concealed the trucks was not entirely natural.

Someone had constructed enormous camouflage doors into the hillside covered with painted canvas and actual vegetation to blend seamlessly with the surrounding landscape.

As she watched, these doors slowly opened, revealing a cavernous entrance lit with electric lights.

The trucks drove directly into the mountain, one after another, and the doors began closing behind them.

But before they shut completely, Astrid glimpsed something that made her heart race.

Beyond the entrance tunnel, the space opened into a vast underground chamber, and on the dark water filling that chamber, she could see the distinctive silhouette of a submarine’s conning tower.

She had been correct.

The Germans had indeed excavated a hidden submarine base inside Hurdler Island, accessible only through concealed entrances that would be virtually impossible to spot from the air.

The trucks she had been tracking were delivering supplies directly into this facility, while the modified vehicles traveling south were probably transporting waste materials or items that needed repair or processing in Bergen’s more sophisticated industrial facilities.

Astrid remained in her hiding place for nearly 2 hours, documenting everything she observed.

She noted the precise location of the entrance, the approximate dimensions of the doors, the number of guards at the checkpoint, and the timing of various activities.

At one point, she heard the deep rumble of diesel engines from inside the mountain, different in character from the truck engines, submarine engines, she was certain, though the sound was muffled by the surrounding rock.

Around 2:30 in the morning, the camouflage doors opened again, and the southbound convoy emerged.

These were indeed the modified trucks she had observed previously, each one pulling an enclosed trailer.

They moved with exaggerated care, as if their cargo required extremely gentle handling.

Astrid watched them cross the causeway and head south toward Bergen.

Then she began her own journey back to her aunt’s farmhouse.

She arrived exhausted but exhilarated, slipping back into the spare bedroom just as the first gray light of dawn touched the eastern sky.

Her notebook bulged with observations, measurements, and sketches.

She had discovered a secret German facility of significant strategic importance, and she had done it with nothing more than baker’s twine, careful observation, and relentless curiosity.

But now she faced a more dangerous challenge.

what to do with this information.

Astrid knew that Norwegian resistance networks existed, but she had no idea how to contact them.

Her father had always maintained strict political neutrality, refusing to engage with either the resistance or the German authorities beyond what was necessary for business.

Her mother avoided all political discussion entirely.

At 14, Astrid had no connections, no contacts, and no clear way to pass her intelligence to anyone who might use it effectively.

She decided to approach the problem with the same methodical thinking she had applied to uncovering the facility.

If resistance networks existed in Bergen, they would need to recruit new members periodically.

They would need to identify trustworthy Norwegians willing to risk their lives opposing the occupation, and they would look for people who demonstrated useful skills, loyalty to Norway, and the discretion to maintain confidentiality.

Astrid began a subtle campaign to establish herself as exactly such a person.

She volunteered to help distribute underground newspapers that occasionally appeared in the bakery, passed along with bread deliveries.

She made a point of speaking Norwegian loudly and proudly in public spaces, refusing to use German, even when it would have been more convenient.

She helped hide Jewish families passing through Bergen on their way to Sweden, storing them briefly in the bakery’s cellar, though she never told her parents what she was doing.

Months passed.

Winter settled over Norway with characteristic darkness and cold.

The Tuesday and Friday convoys continued their regular schedule, now navigating roads slick with ice and snow.

Astrid continued her observations, adding details to her ever growing documentation of the Hurdler facility.

In February 1944, her patience was rewarded.

A man named Gunnar Sunsty entered the bakery one evening just before closing.

He was tall, gaunt, and spoke with the accent of Eastern Norway.

He ordered bread, paid with Norwegian croner, and then, as he turned to leave, said quietly, “The Nielson girl who likes to count trucks.

I believe we have mutual interests.

” Astrid felt her heart race, fear and excitement flooding through her simultaneously.

“I do not know what you mean,” she replied carefully.

“Then perhaps you could show me what you do not know,” Gunner suggested.

“Over tea, away from listening walls.

” They met the following evening in a safe house on Bergen’s outskirts, a fisherman’s cottage that smelled of salt and old wood.

Gunner was joined by two other resistance members, a woman named Seagrid, and an older man who gave no name.

Astrid brought her notebooks.

For 3 hours, she detailed everything she had discovered about the Hurdler submarine base.

the location of the entrance, the convoy schedules, the approximate number of personnel, the sounds of submarine engines, the nature of the supply operations.

She showed them her sketches, her measurements, her carefully documented observations spanning 6 months.

When she finished, Secret looked at Gunner with something approaching awe.

This is gold, she said simply.

London will want this immediately.

The unnamed older man studied Astrid with penetrating eyes.

“You are 14 years old,” he observed.

“Do you understand what you are doing? The risks involved?” “Yes,” Astrid replied without hesitation.

“I understand that Norway is occupied.

I understand that German submarines are sinking Allied ships.

I understand that this facility helps them do that, and I understand that information can be a weapon just as powerful as guns or bombs.

” Gunner smiled for the first time.

You understand correctly.

We will transmit your intelligence to London through our radio networks.

The British will decide what to do with it, but you must continue to appear completely ordinary.

No unusual activities, no changes in routine.

Can you do that? Astrid nodded.

I can be invisible.

I have been invisible my entire life.

The information Astrid provided reached London in March 1944, transmitted through the Norwegian Resistance’s clandestine radio network.

British intelligence, already aware of German submarine operations in Norwegian waters, had suspected the existence of hidden bases, but lacked precise locations.

Astrid’s detailed documentation provided exactly what they needed.

On the night of April 12th, 1944, British Royal Air Force Lancaster bombers conducted a precision raid on Hurdler Island.

The bomber crews had been briefed using intelligence derived partly from aerial reconnaissance, partly from Norwegian resistance reports, and significantly from the observations of a 14-year-old girl who had noticed trucks traveling at night.

The raid severely damaged the camouflaged entrance to the submarine base, collapsed portions of the underground facility, and temporarily disabled the site’s ability to service submarines.

Three German submarines were trapped inside, unable to exit through the damaged tunnel system.

German engineers spent months repairing the facility, but by then, Allied dominance in the North Atlantic had shifted dramatically.

Astred learned of the raid 3 days after it occurred when Gunner visited the bakery and purchased an entire tray of rolls.

“I heard the mountain had problems,” he said conversationally.

“Structural problems, the kind that happen when foundations prove weaker than expected.

” “She understood perfectly, and allowed herself a small smile.

” Her stupid string trick, as she had initially thought of it, combined with persistent observation and careful documentation, had contributed to damaging a strategic German facility.

But Astrid’s work did not end there.

She continued monitoring German activities throughout Bergen and the surrounding region for the remainder of the war, passing intelligence to the resistance network that had adopted her as their youngest operational analyst.

She documented troop movements, supply deliveries, construction projects, and communication patterns.

Her ability to notice anomalies, to identify patterns that others missed, made her an invaluable asset.

When Germany surrendered in May 1945, Astrid was still 14 days short of her 16th birthday.

She had spent nearly 2 years as an active intelligence gatherer for the Norwegian resistance, and her observations had contributed to multiple successful operations beyond the Hurdler raid.

After the war, Norwegian and British intelligence officers debriefed her extensively, amazed by the precision and thoroughess of her documentation.

A British naval intelligence officer named Commander Phillips told her, “We have trained agents who could not match what you accomplished with string and a spy glass.

You have a rare gift for intelligence work, Miss Nielson.

Astrid never pursued intelligence work professionally.

She finished her education, married a fisherman named Eric Hogan, and raised three children in Bergen.

She ran a small bookshop near the harbor for 40 years, a quiet life that suited her perfectly.

But she never stopped noticing patterns, never stopped observing the world with those careful analytical eyes her grandmother had recognized.

In 1987, a Norwegian military historian researching the Herdler submarine base discovered Astrid’s original notebooks in resistance archives.

The historian, Dr.

Helga Vernes, interviewed Astrid extensively, and her story was finally published in a book titled The String That Cut Steel: Intelligence Operations in Occupied Norway.

The book revealed what historians had not previously known.

The April 1944 raid on Herdler had been far more successful than initially assessed.

German records captured after the war showed that the facility’s damage had forced the relocation of significant submarine maintenance operations to other bases, disrupting the entire Norwegian submarine support network for months.

The raid had also damaged stockpiles of specialized munitions and impacted two submarines so severely they never returned to operational status.

Astred Hogan Nay Nielson passed away in 2003 at the age of 74.

Her obituary in Bergen’s newspaper mentioned her bookshop and her family, but made no reference to her wartime activities.

Most of her neighbors never knew that the quiet, elderly woman who sold them books and remembered their children’s names had once been one of Norway’s most effective young intelligence operatives.

But among Norwegian resistance historians and British naval intelligence researchers, her name carried quiet respect.

The girl who had noticed that trucks seemed too heavy in both directions, who had proven her theory with Baker’s twine stretched across a dark road, who had discovered a hidden submarine base through nothing more than methodical observation and relentless curiosity, had demonstrated something profound.

That intelligence work requires not supernatural abilities or elaborate technology, but simply the willingness to notice what others overlook, to question what others accept, and to pursue answers with careful, persistent attention.

The Herdler submarine base, heavily damaged by the April raid and subsequent operations, was partially demolished after the war.

Today, the site operates as a museum, preserving the history of German occupation and Norwegian resistance.

Visitors can tour portions of the underground facility, walking through the same tunnels where submarines once sheltered.

In the museum’s entrance hall hangs a small display dedicated to Astred Nielsen.

It shows one of her original notebooks open to a page of careful sketches and measurements.

Next to it, mounted on black velvet, is a piece of baker’s twine, approximately 1 m long, with a small brass plaque that reads, “The string that revealed a secret, placed by Astred Nielsen, October 1943.

” Visitors often pause at this display, puzzled by the significance of an ordinary piece of string.

But those who read the accompanying text learn that sometimes the simplest tools wielded with intelligence and courage can achieve what sophisticated equipment and extensive resources cannot.

They learned that a curious girl with string and a spy glass helped expose a facility that Germany’s military planners believed was perfectly hidden.

And they learned that observation, analysis, and persistence remain powerful weapons against any form of deception.

And that concludes our story.

If you made it this far, please share your thoughts in the comments.

What part of this historical account surprised you most? Don’t forget to subscribe for more untold stories from World War II, and check out the video on screen for another incredible tale from history.

Until next time.

News

Ilhan Omar ‘PLANS TO FLEE’…. as FBI Questions $30 MILLION NET WORTH

So, while Bavino is cracking down in Minnesota, House Republicans turning the heat up on Ilhan Omar. They want to…

FBI & ICE Raid Walz & Mayor’s Properties In Minnesota LINKED To Somali Fentanyl Network

IC and the FBI move on Minnesota, touching the offices of Governor Tim Walls and the state’s biggest mayors as…

FBI RAIDS Massive LA Taxi Empire – You Won’t Believe What They Found Inside!

On a Tuesday morning, the dispatch radios in hundreds of Los Angeles taxi cabs suddenly stopped playing route assignments. Instead,…

Brandon Frugal Finally Revealed What Forced Production to Halt in Season 7 of Skinwalker Ranch….

The Secret of Skinwalker Ranch became History Channel’s biggest hit. Six successful seasons documenting the unknown with real science and…

1 MINUTE AGO: What FBI Found In Hulk Hogan’s Mansion Will Leave You Shocked….

The FBI didn’t plan to walk into a media firestorm, but the moment agents stepped into Hulk Hogan’s Clearwater mansion,…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage… It started like any other evening…

End of content

No more pages to load