Two young Jewish brothers from a quiet community in New Jersey left for school one day and never returned.

Their fate remained unknown as years turned into a decade of agonizing questions.

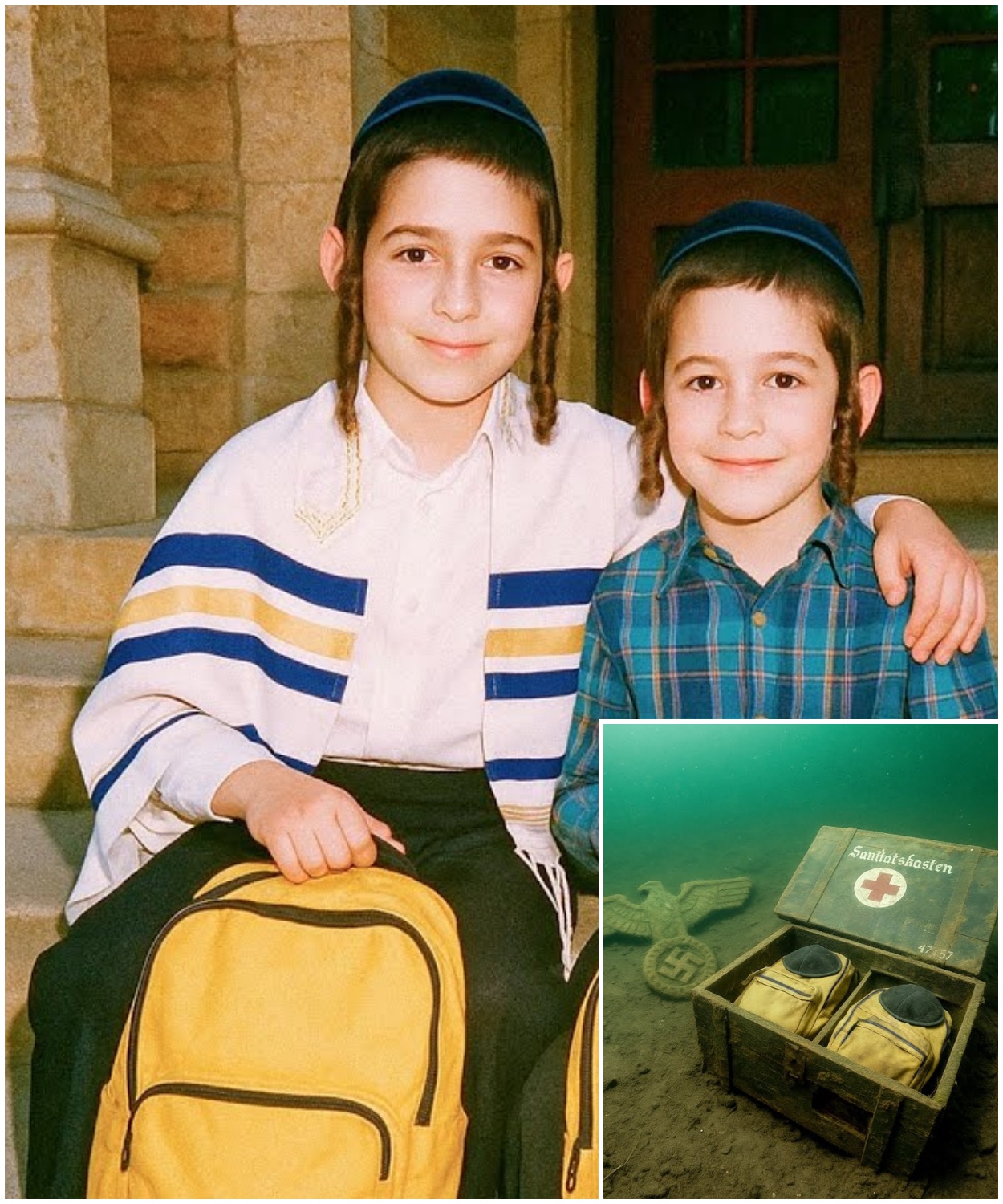

But 11 years later, divers laying new fiber cables at the bottom of a lake discovered something disturbing in the murky depths.

A shocking find that would expose the evil that had been lurking within their peaceful town.

The alarm buzzed sharply at 4:45 a.m.

Rivka Steinman silenced it quickly, and Mosha stirred beside her, reaching for the lamp.

They moved through their morning routine with the practiced deficiency of those who had done this same dance for years, 11 years to be precise.

11 years of early mornings, extra shifts, and the weight of absence that hung in their small T-neck home like a permanent house guest.

Rivka, now 46, tied her graying hair into a bun, the lines on her face etched by sleepless nights.

Mosha, 52, moved more slowly, worn by decades of construction work.

But neither complained.

The extra money from their grueling schedules went toward private investigators toward hope that grew thinner with each passing year.

They gathered their belongings.

Mosha’s hard hat and lunch bag, Rivka’s purse with the photo of two smiling boys.

The photo was from 1995, a year before everything changed.

Elf, then nine, had his arm thrown protectively around 7-year-old Ai’s shoulders.

Both wore their yarmulkas proudly, their pay catching the sunlight.

The October Air and T-neck carried a bite that promised winter’s approach.

They walked in comfortable silence down Palisade Avenue, their breath forming small clouds in the darkness.

The Orthodox Jewish community was already stirring, lights flickering on in houses, the distant sound of morning prayers drifting from an open window.

This Bergen County town had been their sanctuary once, a place where their faith was understood and shared.

Now it felt like a museum of memories.

The bus stop stood under a flickering street light at the corner of Cedar Lane.

They were, as always, 5 minutes early.

Mosha sat down his lunch bag and flexed his fingers against the cold while Rivka pulled her coat tighter.

The familiar rumble of the Route 57A bus announced itself before the headlights swept around the corner.

The door hissed open, revealing Donald Harwick’s familiar face behind the wheel.

The driver, somewhere in his early 50s, had been running this route for as long as they could remember.

His sandy hair was neatly combed, his uniform pressed despite the early hour.

“Morning, folks,” Donald greeted them with his usual warmth.

“Getting cold out there.

” “Good morning, Don,” they replied in unison, a small smile crossing Rivka’s face.

Donald had driven their boys to school on this very bus.

He’d been one of the last to see them that terrible Friday morning in 1996.

They paid their fair, exact change as always, and made their way to their usual seats halfway back.

The bus was empty, save for them, though it would fill up as they moved through town.

Rivka settled by the window, Mosha beside her, their hands finding each other automatically.

The bus lurched into motion, following its predetermined path through Tene’s sleeping streets.

They passed the shuttered shops on Queen Anne Road, the darkened windows of Congregation Bonayesun, the elementary school where their boys should have graduated from years ago.

Rivka’s phone rang just as they passed the Jewish community center.

The sound was jarring in the quiet bus.

She fumbled for it, checking the caller ID with a frown.

“T-neck police,” she murmured to Mosha before answering.

“Hello, Mrs.Steinman.

This is Detective Derek Keller from the Tene Police Department.

Rivka’s grip tightened on the phone.

Beside her, Mosha leaned in, his expression tense.

They’d received calls like this before.

False leads, dead ends, apologies.

Yes, detective.

What is it? Ma’am, I need to inform you that there’s been a development in your son’s case.

The words hung in the air.

Rivka’s free hand found Mosha’s squeezing hard.

“What do you mean a development?” Her voice was barely above a whisper.

A team of worker divers discovered some evidence this morning at the bottom of Lake Tamson.

“We have reason to believe it may be connected to Elf and A’s disappearance.

” Mosha gestured for the phone.

Rivka tilted it between them so they could both hear.

“What kind of evidence?” Mosha asked, his voice rough.

“Sir, I understand you want details, but this is something you need to see for yourselves.

I’m sending officers to your home now.

” “We’re not home,” Mosha interrupted.

“We’re on the bus heading to work, the 57A route.

” A pause.

“I see.

Can you come to the station? We can arrange transport to the site from there.

” “Yes,” Rivka said immediately.

“We’ll come now.

” “Good.

Ask for me when you arrive.

And Mr.and Mrs.

Steinman, I know you’ve been through a lot these past 11 years.

We’re treating this with the utmost seriousness.

The call ended.

Rivka stared at the phone in her hand as if it might ring again with different news.

Around them, the bus continued its route, oblivious to the earthquake that had just shaken their world.

“I need to call work,” Mosha said, already pulling out his own phone.

Rivka nodded, doing the same.

Mosha’s foreman was understanding.

The construction crew knew about the Steinman’s tragedy.

But when Rivka reached her boss at Goldberg’s kosher bakery, Rohan Meera’s voice was sharp with irritation.

Again, Rivka.

This is the third time this month.

Mr.Mayor, the police called.

They found evidence.

Last week, it was a family emergency.

The week before, a medical appointment.

We’re short staffed as it is.

Rivka’s jaw clenched.

This is about my missing sons.

The police need us at Lake Tamson immediately.

And I need my baker here immediately.

You think I believe every excuse? Bring me an official letter from the police tomorrow or don’t bother coming back.

The line went dead.

Rivka stared at her phone, anger and hurt roaring in her chest.

That man, Moshe muttered, having heard enough of the conversation.

He could hire more staff, but he keeps you and Sarah working like slaves.

He pays overtime, Rivka said weakly.

We need the money.

Not at the cost of your dignity.

The police station stop was approaching.

Rivka reached up to press the stop request button, the electronic ding echoing through the empty bus.

Donald glanced at them in the rearview mirror as he pulled to the curb.

“Not heading to work today?” he asked as they gathered their things.

“Police found something at Lake Tamson,” Mosha explained briefly.

“About the boys.

” “Donald’s face shifted.

Concern replacing his usual cheerful demeanor.

” “Lamson? That’s my last stop on this route.

Goes all the way out through Oakdine to the Ramapo area.

45 minutes by bus at least.

We’ll have police transport.

Rivka assured him.

It’ll be faster.

Of course.

I hope.

I hope it’s good news.

Donald’s hands gripped the steering wheel tighter.

Those boys were good kids.

Always had their bus fair ready.

Thank you, Don.

Rivka managed a small smile.

We appreciate that.

They stepped off the bus into the brightening morning.

The police station loomed before them.

Its brick facade somehow both reassuring and ominous.

A patrol car was already waiting in the visitors lot, engine running.

Two officers emerged as they approached.

Mr.and Mrs.Steinman, Detective Keller sent us.

We’ll drive you to the site.

They pulled away from the station and the patrol car ate up the miles between T-neck and Lake Tamson.

Its siren silent but speed urgent.

Mosha held Rivka’s hand the entire way, neither speaking, both lost in memories of two boys who’d vanished on a Friday morning 11 years ago, leaving nothing behind but questions and heartbreak.

The patrol car crested the final hill before Lake Tamson, and Rivka gasped at the scene below.

What should have been a quiet morning at the remote lake had transformed into a hive of activity.

Police cruisers lined the access road, their red and blue lights painting patterns across the water’s surface.

Regional authority vehicles were parked half-hazardly on the grass, and workers in reflective vests moved purposefully around the shoreline.

The October morning had brightened considerably, revealing the full scope of the operation.

“Quite the operation,” the officer driving commented, navigating carefully through the assembled vehicles.

Detective Brennan stood near the water’s edge, his tall frame easy to spot among the crowd.

He was younger than Detective Keller, perhaps early 40s, with the kind of intense focus that suggested he took every case personally.

He looked up as their patrol car approached, raising a hand in acknowledgement.

Mr.and Mrs.Steinman, Detective Brennan, greeted them as they emerged from the vehicle.

His handshake was firm but gentle, as if he understood they might shatter at any moment.

“Thank you for coming so quickly.

I know this must be difficult.

” “Where’s Detective Keller?” Mosha asked, looking around.

“He’s coordinating from the station.

I’m the lead investigator on site.

Please follow me.

” They walked toward the lake, passing forensics technicians in white coveralls who worked with methodical precision.

Yellow evidence markers dotted the ground like artificial flowers.

The morning sun cast long shadows across the scene and the air smelled of lake water and disturbed earth.

Here, Detective Brennan said, stopping at a cordoned area where several evidence bags lay on waterproof sheets.

Rivka’s knees nearly buckled.

Even through the plastic evidence bags, she could see them.

two small yellow backpacks, the same ones she’d bought at Weinstein’s department store for the new school year in 1996.

Beside them, in separate bags, were two Yarmulkas, navy blue with silver trim, and then inongruously, a large metal box marked with German text and a statue of an eagle clutching a swastika in its talons.

“This is Reuben Michaels,” Detective Brennan said, introducing a man in a wet suit who stood nearby.

He made the discovery.

Reuben stepped forward, water still dripping from his diving equipment.

He was perhaps 35 with the solid build of someone who worked underwater for a living.

His expression was somber as he shook their hands.

I’m sorry for your loss, he said quietly.

My team and I were laying fiber optic cables for the new telecommunications grid, part of the county’s infrastructure upgrade.

We were working about 40 ft down when my partner’s equipment snagged on something.

He paused, running a hand through his wet hair.

At first, we thought it was just debris.

The lakes’s full of old junk.

But when we cleared the silt, we saw the medical box.

It’s a sanit casten, a German military medical supply box from World War II.

The eagle statue was wedged beside it.

When we opened the box and saw the backpacks, Reuben’s voice trailed off.

We surfaced immediately and called 911.

Detective Brennan took over.

When I arrived and saw the Yarmmulkas with the backpacks, I made the connection to your son’s case immediately.

11 years is a long time, but some cases you don’t forget.

A forensics technician approached with a box of latex gloves.

We need you to examine the items, Detective Brennan explained.

DNA and fingerprints are unlikely after this long underwater, but you might recognize something personal.

Are you ready? Rivka looked at Mosha.

His jaw was set, his construction worker’s hands clenched at his sides.

She took his hand and nodded.

They pulled on the gloves.

The forensics technician carefully opened the evidence bags, laying out the contents on a clean sheet.

The backpacks had been weighted down with stones, but the yellow fabric was still visible beneath the lake stains.

The zippers were corroded, but intact.

Rivka reached for the first Yarmulka.

She turned it over, and there it was.

Elv Steinman, written in her own careful handwriting with permanent marker on the inside band.

Her vision blurred with tears.

“That’s that’s my writing,” she whispered.

I marked all their clothes for school.

The second yarmula bore A’s name in the same neat script.

The backpacks, when carefully opened, revealed the same markers, names written on the inside fabric where she’d always put them so they wouldn’t get mixed up with other children’s belongings at school.

“These are our son’s things,” Mosha confirmed, his voice thick.

“No question.

” Rivka’s composure finally shattered.

The sobs came from somewhere deep inside.

11 years of compressed grief erupting at once.

Mosha pulled her against his chest, his own tears falling silently into her hair.

Around them, the investigators respectfully stepped back, giving them space to mourn.

After several minutes, Detective Brennan gently approached with tissues and water bottles.

“Take all the time you need,” he said softly.

When Rivka had composed herself enough to continue, Detective Brennan produced several forms.

I need you to sign these confirming the identification, and I need to inform you that based on this evidence, we’re reopening the case with a new classification.

This is no longer just a missing person’s case.

What do you mean? Mosha asked.

The presence of Nazi paraphernalia with your son’s belongings.

The deliberate waiting of the bags.

The remote location.

This suggests a hate crime.

Someone targeted your boys specifically.

The words hung heavy in the morning air.

A hate crime.

They’re beautiful boys targeted for nothing more than their faith.

Do you know anyone who might have harbored such feelings? Detective Brennan asked gently.

anyone who expressed anti-Semitic views or made threats.

Moshe shook his head slowly.

We’re Jewish in America.

There’s always some level of discomfort from some people, but nothing specific.

No threats.

We lived quietly, kept to ourselves mostly.

The boys went to the Jewish day school.

We attended synagogue.

Our neighbors in Tene were always cordial.

The children never mentioned anyone bothering them.

No incidents at school or Detective Brennan.

They all turned at the shout.

Rivka’s heart nearly stopped.

Walking toward them across the grass was Donald Harwick, still in his bus driver’s uniform.

He was slightly out of breath, as if he’d hurried from the parking area.

“Sir, this is a restricted area.

” One of the officers immediately intercepted him.

“This is an active crime scene.

” “It’s all right,” Mosha said quickly.

We know him.

This is Donald, our bus driver.

Donald’s face was creased with concern as he approached.

I’m sorry to intrude.

I saw all the commotion when I reached my turnaround up at the overlook.

This is the last stop on my route.

You see the 57A ends at the Lake Tamson overlook.

Detective Brennan studied Donald carefully.

You’re Donald Harwick.

You drove the Steinman boys bus route? Yes, sir.

I spoke extensively with Detective Keller back in 96.

Donald’s voice was steady but sad.

I was the last person to see those boys before they disappeared.

It’s haunted me all these years.

What brings you here now, Mr.

Harwick? Detective Brennan’s tone was professional but not unkind.

Like I said, this is my roots terminus.

I usually take my break at the overlook, have a smoke, stretch my legs.

I’ve been driving this route for 15 years, stopping here every day.

When I saw all the police vehicles, he gestured helplessly.

I had to know if it was connected to the boys.

Where did you park? The detective asked.

Up at the closed off turnabout near the overlook, same place I always park.

Donald’s eyes moved to Rivka and Mosha.

I’m so sorry.

Those boys were good children, always polite.

In 11 years of wondering, I never imagined they might be here, right where I stop every day.

Detective Brennan made a note.

Mr.

Harwick, since you’re here, would you mind answering a few questions? Of course.

You can take a look at what we found if Mr.

and Mrs.

Steinman don’t object.

Rivka and Mosha nodded their consent.

Donald approached the evidence slowly, his face paling as he took in the scene, his eyes lingered on the Nazi memorabilia.

“My god,” he breathed.

Then, unexpectedly, he leaned closer to the sanit caston and eagle statue.

“These look authentic.

” “What makes you say that?” Detective Brennan asked sharply.

Donald straightened, looking slightly embarrassed.

“I read a lot of history in my spare time.

Jewish history actually and World War II history by extension.

It’s a personal interest.

I’m sure the police had that on records when they checked my house 11 years ago.

These items, the wear patterns, the manufacturer’s marks, they look like genuine period pieces, not reproductions.

You study Jewish history? Rivka asked, surprised despite her grief.

Among other things, history helps us understand the present, don’t you think? Donald’s expression was earnest.

But I’m no expert, just an amateur enthusiast.

Detective Brennan made more notes.

We’ll have our experts authenticate them.

We’re also checking our databases for any neo-Nazi activity in the area, any collectors of this type of memorabilia.

Are you sending divers back down? Donald asked.

Yes, it’s a big lake.

We’re conducting a thorough search for The detective paused, glancing at Rivka and Mosha.

Additional evidence.

They all understood what he meant.

Bodies.

I should go, Donald said quietly.

Let you folks do your work.

Rivka, Mosha, I’m heading back to town now if you need a ride.

I know the police brought you, but if you’d prefer.

That’s kind of you, Detective Brennan interjected.

But we can provide transportation.

Mosha looked at his watch.

It would be good if I can still make it to work, he said suddenly.

But I totally understand if there’s still any procedures we need to finish at the station, detective.

Mosha, Rivka protested, but he shook his head.

I know, but we need the money, especially now.

Detective, you’ll call if there’s any news.

Of course, for now, you may return to your activities.

We will provide an update shortly.

I should go to work too, Rivka said, though her voice lacked conviction.

Mosha studied her face.

You’re pale as a sheet, and your boss was already angry this morning.

Go home and rest.

He demanded a police letter, Rivka remembered.

Proof that this was real.

Detective Brennan’s expression hardened slightly.

I can provide that right now.

He pulled out an official letter head from his folder and began writing.

After a moment, he signed and stamped it with an official seal.

This should satisfy any employer.

We’ll take the bus, Rivka decided.

I’ll ride with you to your stop at least.

They said their goodbyes to Detective Brennan.

Donald led them up the slope to where the 57A bus waited at the overlook turnabout, its diesel engine idling.

As they climbed aboard, Rivka took one last look back at the lake.

Somewhere in those dark waters, her boy’s story had been hidden for 11 years.

The bus pulled away from Lake Tamson, its engine grinding through the gears as Donald navigated the winding road back toward town.

Rivka and Mosha sat in their usual seats, but nothing about this morning was usual.

The weight of what they’d seen pressed down on them like a physical thing.

11 years, Mosha said quietly, staring at his workroughened hands.

11 years of not knowing.

Rivka nodded, unable to speak.

The image of those small yellow backpacks waited with stones kept flashing behind her eyelids.

Someone had wanted their boys to disappear forever beneath the dark waters of Lake Tamson.

“Do you remember that morning?” she asked, though of course he did.

They’d relived it thousands of times.

September 13th, 1996.

Friday morning, they left at 7:15 to catch the bus.

Mosha’s voice was mechanical, reciting facts worn smooth by repetition.

Elav had his Torah portion to practice.

Avi was excited about the art project they were doing for Sukkot.

From the driver’s seat, Donald glanced at them in the rearview mirror.

I’ve gone over that morning so many times.

They were at their usual stop.

I drove them to school.

They stepped out of the bus after all the other students like usual.

You told the police you didn’t see them enter the school building.

Rivka said, not accusingly, just stating fact.

That’s right.

I had 17 other kids on the bus that morning.

The Rosen twins, the Goldberg boys, little Sarah Weiss.

Normally a teacher would be there to greet them outside, but that day no one was.

Donald’s hands tightened on the steering wheel.

The school didn’t call until after 9.

Mosha continued the familiar litany.

By then, 2 hours had passed.

The police thought they’d wandered off, Rivka added.

Two boys deciding to skip school have an adventure.

But where? Every shop owner on Cedar Avenue knew them.

someone would have seen them at the arcade or the comic book store.

The police interviewed everyone, Donald said.

I gave them my complete passenger list, my entire route.

They talked to every family, every kid who rode my bus.

The bus rumbled through Oakdan, past suburban houses where normal families were living normal lives.

Rivka envied them with a fierceness that surprised her.

Rabbi Goldstein, the principles at three different schools, even the crossing guards, Mosha listed.

Nobody saw them.

They fell silent.

The bus reached Mosha’s construction site.

Stop first.

He kissed Rivka’s forehead and squeezed her shoulder.

“Call me if you hear anything,” he said.

“And go home.

Rest.

” “I will,” she lied.

Mosha climbed down from the bus.

his lunch bag and hard hat in hand.

Rifka watched him walk toward the construction site, his shoulders bent but determined.

They needed his paycheck, especially now that the case was reopening.

Private investigators, lawyers, perhaps it all cost money.

The bus continued its route.

Rifka moved to a seat closer to the front, needing the distraction of watching the familiar streets roll by.

When they reached her stop, she stood on unsteady legs.

Thank you, Don, she said, for everything, for caring about them.

They were good boys, Donald replied simply.

I hope this leads to answers.

Rivka walked the three blocks to her house, the October air sharp in her lungs.

The house felt oppressively quiet when she entered.

She set down her purse, placed the police letter on the kitchen counter, and stood in the silence.

She should rest.

she should pray.

Instead, she found herself in the small den powering on their old Dell computer.

As it weased to life, she thought about the Nazi memorabilia found with her son’s belongings.

Who in Tene would own such things? Who would harbor such hate? The Internet Explorer browser loaded slowly.

She typed neo-Nazi groups New Jersey 2007.

Articles populated her screen.

She clicked through them, reading about small but persistent groups scattered throughout the state.

Then, in an article about the postworld war II growth of extremist movements in New Jersey, a familiar face caught her eye.

Maurice, she breathed.

There was her college friend Maurice Goldfarb, now apparently a senior journalist.

The photo showed her giving a lecture at Fairley Dickinson University’s T-neck campus just last year.

The caption identified her as an expert on extremist movements in the tri-state area.

Rivka’s hand shook as she logged into Facebook.

She found Maurice’s profile easily and typed a message.

Maurice, it’s Rivka Steinman, Rosen from college.

I need to talk to you urgently about something.

Please call me.

She included her phone number and hit send.

Maurice’s status showed as offline.

Rivka tried to lie down, but rest wouldn’t come.

The house felt like a tomb.

After 20 minutes of staring at the ceiling, she made a decision.

She grabbed her car keys and the police letter.

If she was going to be miserable, she might as well be miserable and productive.

The 1999 Toyota Camry started on the second try.

Rivka rarely drove.

Gas was expensive and the bus was reliable.

But today, she needed the control, the ability to leave when she wanted.

The familiar route to Goldberg’s kosher bakery took only 10 minutes by car.

She pulled into the small parking lot behind the bakery.

Through the back door, she could see Rohan Mea in his small office and Rafi manning the front counter alone.

The kitchen would be chaos without her.

The bell chimed as she entered.

Rohan’s head snapped up, his face shifting from surprise to suspicion.

“So you were lying,” he accused, emerging from his office.

“Emergency with police,” you said.

“But here you are.

” “I wasn’t lying.

” Rivka held out the police letter.

“Here’s your proof.

” Rohan snatched the letter, scanning it quickly.

His expression didn’t soften.

Behind the counter, Rafi busied himself with arranging pastries.

clearly uncomfortable with the confrontation.

“What did they find?” Rohan asked, no sympathy in his voice.

Rivka hesitated.

“Sharing her pain with this man felt wrong, but she answered anyway.

” “A Nazi medical box, a sanit casten with my son’s backpacks and yarmokas inside, and a Nazi eagle statue with a swastika.

” Rohan cursed under his breath, but his face remained cold.

No condolences, no kindness.

Fine, I’ll accept your excuse for being late.

If you want to work, get changed.

We’re behind on everything.

The dismissal stung.

Rivka walked to the changing room, pulling on her baker’s uniform and apron with mechanical movements.

She tied her hair back tightly, covered it with the required hairet, and entered the kitchen.

Sarah, her coworker, looked up from a batch of chalado with relief and exhaustion written across her face.

Oh, thank God you’re here.

Sarah wiped flower dusted hands on her apron, her face flushed from the heat of the ovens.

I’ve been running between the mixer and the oven since 5 this morning.

We’re so behind on orders.

I’m sorry, Sarah.

Rivka tied her apron strings tighter, already assessing the kitchen’s chaos.

Mixing bowls were stacked half-hazardly, and the scent of baking bread couldn’t quite mask something slightly off.

I’ll explain everything later, but right now what do you need me to do? Chala, first we have orders for 20 loaves for Shabbat and then Hammentashen.

Mrs.

Rosenberg ordered four dozen for her grandson’s birthday party.

Sarah gestured at the cooling racks.

I’ve been doing my best, but Rivka moved to inspect the morning’s work.

The chala loaves looked acceptable from a distance, but as she picked one up, her experienced hands detected the problem immediately.

The texture was wrong, denser than it should be, lacking the light, pillowy quality their customers expected.

She broke off a piece of hamandashen and tasted it.

The flavor was there, but again, the texture was off.

These weren’t the melt-in-your-mouth cookies that had made Goldberg’s kosher bakery famous in the Orthodox community.

Sarah, she said carefully, not wanting to hurt her friend’s feelings.

What flour did you use? Sarah’s shoulders sagged.

I know they’re not right.

We’re almost out of the high gluten flour.

I’ve been mixing it with the allpurpose to stretch what we have.

Why didn’t you tell Rohan we needed supplies? I did.

Sarah’s frustration bubbled over.

I’ve been telling him for 2 weeks.

He keeps saying the order is coming, but it never does.

Finally, yesterday, he told me to just mix the flowers and make do.

Rivka felt her jaw tighten.

He told you to compromise the quality.

Look at him.

Sarah lowered her voice, glancing toward the office.

He’s from India.

No offense to where he comes from, but he doesn’t understand what these products mean to our community.

He hides in that office all day.

Lets Rafie and us be the face of the store.

Tells us to bake it the Jewish way like it’s just following a recipe.

He doesn’t understand that cashroot isn’t just about ingredients.

It’s about integrity.

Rivka set down the substandard hamashin.

I’ll talk to him.

Good luck.

He’s been on the phone all morning.

Sounds upset about something.

Rivka walked through the narrow hallway to Rohan’s office.

Through the thin door, she could hear his voice speaking rapidly.

She knocked.

No answer.

She raised her hand to knock again when his voice rose sharply.

Need to clean up immediately.

The authorities No, there’s no time for another knock.

Firmer this time.

What? The response was sharp.

Annoyed.

Rivka opened the door to find Rohan already standing, shoving papers into a leather bag.

His usually composed demeanor was frayed at the edges, sweat beating on his forehead despite the cool October morning.

Mr.

Mea, we have a problem in the kitchen.

We’re out of proper flour.

The products aren’t meeting our quality standards.

Handle it yourself.

He didn’t even look at her, continuing to pack his bag with trembling hands.

You know what to do.

Our customers will notice.

Mrs.

Rosenberg has been coming here for 30 years.

She’ll know immediately if the Hamandashen aren’t.

I said handle it.

He pushed past her, heading for the back door.

I have urgent matters to attend to.

Rivka followed him into the parking lot, frustration overcoming her usual deference.

If I buy the supplies myself, will you reimburse me? You still haven’t paid me back from last time? Rohan spun around, his face flushed with anger.

You’ll get your money with your next paycheck.

Why must you always The car keys slipped from his agitated hands, clattering on the asphalt.

He bent quickly to retrieve them, and his shirt rode up on his left side.

Rivka’s blood turned to ice.

There, just above his waistline, was the dark edge of a tattoo.

The angular lines were unmistakable, even in that brief glimpse.

A swastika.

“Wait,” she said, her voice barely a whisper.

“What now?” he straightened, keys in hand.

“That tattoo? Is that a swastika?” Rohan’s face went through several expressions: surprise, anger, and finally cold disdain.

He yanked his shirt down.

It’s not a Nazi swastika as you people always assume.

It’s a Hindu swastika, a sacred symbol that existed for thousands of years before the Nazis corrupted it.

I you have a lot to learn about history and religion beyond your narrow worldview, Mrs.

Steinman.

Perhaps you should educate yourself as thoroughly as you obsess over your precious baked goods.

His voice dripped contempt.

The swastika means good fortune in my culture.

But of course, everything must be about your people’s suffering, mustn’t it? Before Rivka could respond, he climbed into his car and peeled out of the parking lot, leaving her standing alone in the cool morning air.

She walked back into the bakery on unsteady legs.

Rafie looked up from the register, his young face curious, but wisely silent.

He’d learned not to get involved in the drama between the boss and the bakers.

Back in the kitchen, Sarah was measuring out the last of their good flour.

“Don’t start another batch,” Rivka said, already untying her apron.

“I’m going to get supplies.

” “I can give you money,” Sarah offered.

“I still have cash from what customers paid me directly yesterday.

You shouldn’t have to keep covering for his mismanagement.

” “It’s fine.

I’ll sort it out with him later.

” Rivka was already heading to the changing room, her mind racing.

The image of that tattoo burned in her memory.

Hindu swastika or Nazi swastika.

Want me to send Rafy with you? Those flower sacks are heavy.

I’ll manage, Rivka called back, pulling on her street clothes.

She needed to think, and she couldn’t do that with Rafy’s chatter.

10 minutes later, she was back in her Camry, heading toward the baking supply store at the edge of town.

Her hands gripped the steering wheel tightly as she tried to process the morning’s revelations.

Nazi artifacts at the lake, Rohan’s tattoo, and his frantic phone call.

Was she being paranoid, seeing connections where none existed, or was something darker stirring in her quiet corner of New Jersey? The drive to Meyer’s baking supply should have been routine.

The baking supply store sat next to Tene Hardware, one of the last stops before the town gave way to the less developed areas leading toward the Ramapo Mountains.

Rivka had made this trip dozens of times over the years, usually grumbling about Rohan’s poor inventory management.

But as she passed the NJ Transit bus depot on Route 4, movement in her peripheral vision made her glance to the right.

A familiar figure was climbing into a gray sedan.

Rohan, his distinctive blue shirt and hurried movements unmistakable even from a distance.

The driver looked like Donald from behind.

The same sandy hair, the same broad shoulders.

But that couldn’t be right.

Donald’s shift ran until evening.

She almost dismissed it.

After all, Teneck wasn’t that large.

People knew each other, ran into each other.

But something about the urgency of their movements, the way Rohan kept glancing around as he got in the car, made her stomach tighten.

The supply store parking lot was nearly empty when she pulled in.

As she turned off the engine, she saw the gray sedan pull into T-neck hardware next door.

Her suspicions were confirmed when both men emerged.

It was definitely Donald, still in his bus driver’s uniform.

Probably nothing, she told herself.

They’re at a hardware store.

Maybe Donald needs help with a home project.

Inside Meyers, she forced herself to focus on her task.

The familiar smell of flour and yeast should have been comforting, but her mind kept wandering to the two men next door.

“15 kilos of your best high gluten,” she told Meyer’s son, Jacob, who manned the register.

“Having supply problems at Goldbergs again?” Jacob asked sympathetically as he rang her up.

You could say that.

She handed over her credit card, wincing at the charge.

Another expense Rohan might or might not reimburse.

Jacob helped her carry the heavy sack to her car.

As she opened the trunk, she saw Donald and Rohan emerging from the hardware store.

Donald carried a large blue shopping bag, the store’s heavyduty kind, while Rohan had a box under each arm.

They were moving quickly, purposefully.

before she could second-guess herself.

Rivka was walking toward them.

Both men froze when they saw her.

Donald recovered first, his usual friendly smile appearing, though it didn’t quite reach his eyes.

Rivka, what brings you out here? I told you we were out of flour, she said to Rohan, trying to keep her voice light.

You said to handle it, so here I am.

Rohan’s face darkened.

This place is too expensive.

You should have gone to the wholesale supplier in Hackinack.

That’s 40 minutes away now, Rohan.

Donald interrupted smoothly.

Rivka’s had a difficult day.

We all have.

He shifted the heavy bag to his other hand, and Rivka caught a glimpse of metal inside.

Pipes or tools? She couldn’t tell.

I didn’t know you knew each other, Rivka said, looking between them.

Small town, Donald replied.

Rohan’s helping me with some electrical work at my place.

Man’s a genius with wiring.

I thought you were working until evening.

Short shift today, only 3 hours.

Union rules about overtime.

Donald’s explanation came readily, but something in his eyes seemed guarded.

Rivka nodded slowly.

Well, I should get back.

Sarah’s alone at the bakery.

Yes, go,” Rohan said curtly.

“And no more detours.

We have orders to fill.

” As she turned to leave, she watched Donald load the supplies into his trunk.

The heavy bag shifted, and his movement caused something to slip out from his collar, a necklace with a pendant.

From her angle, she could see it clearly.

An eagle with spread wings clutching something in its talons.

A medallion of some sort, though she couldn’t make out the symbol.

Her breath caught.

It looked disturbingly similar to the Nazi eagle statue found with her son’s belongings.

Donald noticed her staring and quickly tucked the necklace back inside his shirt.

Their eyes met for a moment and something passed between them.

Not the friendly warmth she was used to, but something harder, more calculating.

“Drive safely, Rivka,” he said, closing his trunk with a solid thunk.

She mumbled a goodbye and walked back to her car on unsteady legs.

As she drove away, she kept glancing in the rearview mirror, but Donald’s car remained in the parking lot.

“You’re being paranoid,” she told herself.

“Lots of people wear eagle jewelry.

It doesn’t mean anything.

” “But the unease in her gut wouldn’t subside.

In all the years she’d known Donald, she’d rarely seen him outside his bus.

He was always professional, contained, seated behind that big steering wheel.

The necklace, Rohan’s tattoo, the Nazi artifacts found with her boy’s belongings.

Was she seeing patterns where none existed? On impulse, she pulled into quick copy, a print shop three blocks from the bakery.

She needed answers, or at least context.

Can I use a computer for a few minutes? She asked the teenage clerk.

$5 for 15 minutes,” he replied, barely looking up from his phone.

She paid and sat at one of the aging PCs.

First, she Googled Hindu swastika versus Nazi swastika.

The images that loaded showed clear differences.

The Hindu version was usually dots between the arms, often decorated with additional symbols, and faced the opposite direction.

She thought back to the glimpse of Rohan’s tattoo.

Had there been dots? She couldn’t remember clearly.

Next, she logged into Facebook.

A red notification showed.

Maurice had replied.

Rivka.

Oh my god.

I can’t believe what you’re going through.

Yes, we need to talk.

I’ve been investigating neo-Nazi groups in North Jersey for an article.

They’re more organized than people think and very secretive.

Can you call me? Rivka typed.

at work now and need to get back to it quickly, but found more concerning things.

My boss has a swastika tattoo, he says.

Hindu bus driver wearing eagle necklace similar to Nazi eagle found with boys things.

How can you tell for sure if someone is part of these groups? It’s not easy or police would have found them all, but they usually have the Nazi swastika hidden on their body somewhere.

They collect memorabilia.

They know each other.

Help each other.

Be careful, Rivka.

These people can be dangerous when cornered.

Rivka’s hands trembled as she typed.

We’ll call tonight.

Thank you.

She logged off and paid.

Walking back to her car, she felt the weight of the flower sack in her trunk like an anchor.

Part of her wanted to drive to the police station immediately.

But what would she say? that her boss had a tattoo and her bus driver wore an eagle necklace.

They’d think she was a grieving mother, seeing Nazis everywhere.

Donald’s car was gone when she passed the hardware store again.

She thought about following, trying to find where he and Rohan had gone, but that was crazy.

What would she do if she found them? Confront two men alone? Sarah needs me, she told herself firmly.

The bakery needs me.

I’m overthinking this.

She drove back to Goldberg’s.

Rivka hefted the flower sack into the bakery’s kitchen, her movements mechanical.

Sarah looked up from kneading challo, relief evident on her flower dusted face.

Thank God we can start making proper bread again.

But Rivka couldn’t focus.

She measured ingredients wrong twice, nearly added salt instead of sugar to the hamandash and dough.

Her hands, usually so steady and sure in this familiar space, trembled as she tried to braid Chala.

The image of Donald’s eagle necklace kept flashing in her mind, the cold calculation in his eyes.

Rohan’s frantic phone call about authorities, the way they’d driven off toward the mountain region.

Rivka.

Sarah touched her shoulder gently.

What’s wrong? I can’t.

Rivka set down the dough, her hands shaking.

I can’t do this.

My mind I keep thinking about this morning about what they found.

And then I saw.

She trailed off, unsure how to explain her suspicions without sounding paranoid.

Sarah’s face softened with understanding.

Oh, honey, after what you’ve been through today, of course you can’t concentrate.

Go home.

Rest.

But the orders, I’ll handle it.

I’ve got good flour now, thanks to you.

Go take care of yourself.

Rivka hugged her friend gratefully, then walked out through the back door to avoid any potential confrontation with Rohan if he’d returned.

In her car, she sat for a moment, trying to calm her racing thoughts.

Finally, she called Moshe.

Rivka, is everything all right? His voice was concerned.

She poured out everything, the tattoo, the necklace, seeing them at the hardware store, her conversation with Maurice.

When she finished, Mosha was quiet for a long moment.

“My foreman let me leave early,” he said finally.

“After I told him about this morning.

” “Listen, why don’t you pick me up? We’ll go back to the lake to the peaceful side, have a little picnic, try to process all this.

Not near the crime scene, but you know that spot we used to take the boys.

The suggestion of returning to Lake Tamson should have been repellent, but somehow it felt right, like they needed to reclaim some small part of it from the horror.

Okay, she agreed.

I’ll be there in 10 minutes.

She found Mosha waiting outside the construction site, his lunch bag in hand.

He climbed in and squeezed her hand.

We’ll get through this,” he said simply.

The drive to Lake Tamson took 45 minutes in midday traffic.

They rode in comfortable silence, both lost in their thoughts.

When they reached the lake’s public parking area, Rivka pulled into a spot overlooking the water.

The October sun had burned through the morning clouds, making the lake surface sparkle almost prettily.

They were just stepping out of the car when Rivka caught sight of a familiar gray sedan passing behind them on the access road.

Through the window, she clearly saw Rohan’s profile and Donald at the wheel.

Moshe, she grabbed his arm, pointing, “That’s them, Donald and Rohan.

” Moshe frowned, watching the car disappear around a bend.

What are they doing here? You said Donald was helping with electrical work at his house.

Donald lives in Bergenfield.

He mentioned it once when the boys were talking about their little league district and Rohan lives in Fair Lawn.

So why come all the way out here? There aren’t many cabins in this area.

Too expensive, too protected.

Maybe that’s the project.

Working on a cabin.

Moshe considered this, then shook his head.

Let’s find out.

If it’s nothing, no harm done.

Donald’s always been good to us, and your boss, well, he’ll be angry, but you have that police letter.

You’re entitled to a day off after what we’ve been through.

” They got back in the car and followed at a distance.

Rivka expected the gray sedan to turn toward one of the few residential areas around the lake, but instead it continued to the less developed eastern shore.

Then to her surprise, Donald’s car turned onto an unmarked dirt road that led into the woods.

“That’s not a residential area,” Mosha said, his voice tight.

“That’s an old service road.

Goes down to the water, but it’s been officially closed for years.

What are two men doing going down there?” He pulled their car to the shoulder of the main road.

“Stay here.

I’ll go look.

” “Absolutely not.

I’m not sitting here alone.

” Rivka, if something’s wrong, then we call the police right now.

She was already pulling out her phone.

This feels wrong, Mosha.

Everything about this feels wrong.

He hesitated, then nodded.

Call them, but I’m going to get closer just to see what they’re doing.

I’ll keep you on the phone.

Before she could protest further, he was out of the car, moving into the treeine.

Rivka’s fingers shook as she dialed Detective Brennan’s direct number.

Detective Brennan, this is Rivka Steinman.

My husband and I are at Lake Tamson on the East Shore.

We saw my boss and Donald, the bus driver, go down a closed service road.

Something’s not right.

What are they doing there? We don’t know.

My husband is Her phone beeped with an incoming call.

Detective, that’s my husband calling.

Can I put you on hold? Yes, keep the line open.

She switched calls.

Mosha.

His voice was low, breathless from moving quickly through the woods.

The trail winds down toward the water.

Their cars parked at the end.

Rivka, they’re unloading something from the trunk.

It’s It’s a barrel.

Industriall looking metal.

A barrel.

They’re both carrying it.

It must be heavy.

They’re struggling.

They’re heading toward the shore where there’s an old boat tied up.

A pause.

Then his breathing quickened.

Rivka.

Oh god.

What? I heard something from inside the barrel like like scratching or knocking.

There’s someone in there.

Rivka’s blood turned to ice.

She switched back to Detective Brennan, her voice high with panic.

Detective, they have a barrel and my husband says there’s someone inside.

They’re putting it in a boat.

We’re dispatching units immediately.

Helicopter, divers, everything.

Tell your husband to stay hidden and do not engage.

We’ll be there as fast as possible.

Could it be Could it be one of my boys? We don’t know, Mrs.

Steinman, but we’re going to find out.

Keep both lines open.

Whatever’s happening, we’re going to stop it.

Rivka clutched the phone, dividing her attention between Mosha’s whispered updates and the detectives asurances.

Help was coming, but would it be in time? In the next 15 minutes, the distant thrum of helicopter rotors grew louder with each passing second.

Rivka stood frozen beside the car, phone pressed to her ear, dividing her attention between Mosha’s whispered updates and the approaching cavalry.

“They hear it!” Mosha’s voice came through tight with tension.

They’re panicking.

Donald’s trying to start the boat engine.

No, wait.

They’re stopping.

They’re tying weights to the barrel.

They’re going to sink it.

Rivka breathed.

The helicopter burst over the treeine, the downdraft whipping her hair across her face.

Below, she could see the boat rocking violently in the rotor wash.

Police sirens wailed behind her and Detective Brennan’s unmarked car skidded to a stop beside hers.

“I need to end the call,” she told Mosha quickly.

“Police are here.

” Detective Brennan emerged, his face grim.

“Mrs.

Steinman.

” “This can’t be good,” she said, her voice shaking.

“Nobody throws something into the lake in a remote section unless they’re trying to hide something terrible.

” The detective’s expression softened slightly.

It could be your son.

Yes, we have to prepare for that possibility.

He handed her binoculars.

Through the magnified lenses, she watched a scene unfold that seemed pulled from an action movie.

The barrel was already partially submerged.

Donald and Rohan frantically trying to push it deeper.

Then, like something from a military operation, officers began repelling from the helicopter directly onto the small boat.

The boat rocked dangerously.

She couldn’t hear anything over the helicopter’s roar, but she could see Donald raising his hands in surrender, while Rohan appeared to be shouting, gesturing wildly.

The officers moved with practiced efficiency, securing both men even as the boat threatened to capsize.

“What strikes me?” she said quietly, “Is how different Donald looks.

All these years he was so kind, so gentle with the children.

” The detective took back the binoculars.

“People can hide their true nature for a very long time,” Mrs.

Steinman.

“More boats were converging on the scene, police boats that had been stationed around the lake.

She watched divers plunge into the water where the barrel had sunk.

Long minutes passed.

Then finally, one diver surfaced, giving a thumbs up.

“They have it,” Detective Brennan said.

“They’re bringing it up.

” A splash in the nearby vegetation made her jump, but it was only Mosha emerging from his hiding spot.

His face was flushed with exertion and rage.

“If there’s a child in that barrel, I swear I’ll He couldn’t finish the sentence, his hands clenching and unclenching at his sides.

Let’s go to the dock,” Detective Brennan said calmly.

“That’s where they’ll bring everyone.

” They followed the detectives car around the lake to the public dock on the western shore.

By the time they arrived, a crowd of emergency vehicles had assembled.

They watched as a police boat approached, Donald and Rohan visible in handcuffs, flanked by officers.

As the boat docked, Rivka stepped forward.

“What were you doing?” she demanded, looking between the two men.

What were you thinking? Donald’s face was a mask of cold indifference, so different from the warm bus driver she’d known for over a decade.

He said nothing, staring straight ahead.

But Rohan spat on the wooden dock, his eyes blazing with hatred.

“This isn’t over,” he snarled at her.

“You think you’ve won? I’ll come after you.

My people will come after you.

” That’s enough, an officer said sharply, yanking Rohan toward a waiting police car.

Then another boat arrived, and Rivka’s world tilted on its axis.

A small figure sat huddled between two divers, a thermal blanket around his shoulders.

Even soaking wet, even 11 years older, she knew him instantly.

“Avie,” she whispered.

The boy, no, young man now, he must be 19, looked up at the sound of his name.

His eyes, those same brown eyes she’d kissed goodn night thousands of times, met hers across the dock.

Avi, she rushed forward and he stumbled into her arms, collapsing against her as if his legs couldn’t hold him anymore.

He didn’t speak, just clung to her, his body shaking with cold and trauma.

“It’s okay,” she murmured, holding him tight.

“You’re safe now.

It’s going to be okay.

It’s only getting better from here.

” He was drowning, one of the divers explained.

Water was already seeping into the barrel.

We found holes in various parts, man-made holes.

Another few minutes, and he didn’t need to finish.

We got most of the water out of his lungs on the boat, but he needs medical attention.

Detective Brennan had been questioning Donald and Rohan.

Now he turned back to them, his face grave.

Where’s the other boy? Where’s Eliov? Donald remained stone-faced, but Rohan laughed, a sound that made Rivka’s blood run cold.

“The lake ate him up years ago,” he said with evident satisfaction.

“Fed him to the fishes where he belonged.

” Mosha lunged forward, but officers restrained him.

Avi made a sound, not quite a word, more like a wounded animals cry, and pressed his face into Rivka’s shoulder.

“Search the lake again,” Detective Brennan ordered his team.

I know we searched this morning, but that was just the immediate area.

If a barrel was sunk years ago, nature would have hidden it.

Check every rock formation, every weed, every sandbar.

I want dive teams covering every inch of this lake.

The officers began processing Donald and Rohan for transport.

As they emptied pockets and removed personal items, Rivka saw them confiscate Donald’s necklace, the eagle pendant she’d glimpsed at the hardware store.

Now she could see it clearly.

An eagle clutching a swastika medallion matching exactly the statue found that morning with the boy’s belongings.

Turned to the side.

An officer ordered Rohan.

When he did, they photographed the tattoo on his waist, not a Hindu swastika as he’d claimed, but clearly the Nazi version, stark and undisguised.

The medical team had arrived with ambulances.

They wrapped Avi in more blankets, checking his vital signs with practice deficiency.

19-year-old male, possible hypothermia, water aspiration, one paramedic called out.

Vitals are stable, but he’s in shock.

We need to transport immediately.

You can ride with him, another told Rivka.

Dad, you’ll need to follow in your car.

As they prepared to load Avi into the ambulance, Rivka took one last look at Donald and Rohan being driven away in separate police cars.

Donald finally met her eyes through the window, and what she saw there made her shudder.

Not remorse, not humanity, just cold hatred.

She climbed into the ambulance, taking Avi’s hand in both of hers.

It was larger than she remembered.

No longer a child’s hand, but she knew every line, every knuckle.

Her baby was alive, damaged, traumatized, but alive.

“I’m here,” she whispered as the ambulance doors closed.

“Mama’s here.

I’m not letting go.

” behind them.

Moshe followed in their old Camry, and the convoy of hope and heartbreak wound its way back toward town, toward hospitals and healing, and the long journey of learning what had been done to their surviving son during 11 stolen years.

The emergency room at Holyame Medical Center was a controlled chaos of beeping monitors and hurried footsteps.

Rivka watched helplessly as medical staff wheeled Avi through the automatic doors marked authorized personnel only.

A nurse gently but firmly directed them to the waiting area.

“The doctor will update you as soon as possible,” she said.

“There’s a family room down the hall if you need privacy.

” “They found themselves in a small windowless room with uncomfortable chairs and a box of tissues on a side table.

The moment the door closed, Rivka’s composure shattered completely.

The tears came in waves for Aby’s survival, for Eliov’s loss, for 11 years of not knowing.

“Maybe he’s still alive,” Mosha said desperately, pulling her close.

“The police didn’t find another barrel this morning.

Maybe Rohan was lying, trying to hurt us.

” Rivka shook her head against his chest.

“You didn’t see his eyes, Moshe.

That triumph, that satisfaction when he said it, he wasn’t lying.

Our Elv is gone.

Those monsters.

Mosha’s voice broke.

What did they do to our boys? Avi looked so empty, broken.

Donald drove them to school every day.

Every single day, we smiled at him, thanked him.

and Rohan.

I made his precious Jewish baked goods while he she couldn’t finish.

They hated us just for existing, Mosha said bitterly.

For being Jewish in their town.

Our boys never hurt anyone.

They were children.

Some people are broken inside, Rivka whispered, filled with such darkness.

An hour later, a doctor appeared, a kind-faced woman in her 50s.

Mr.and Mrs.Steinman, I’m Dr.Chen.

We’ve completed our initial examination of Avy.

They stood quickly, clutching each other’s hands.

Physically, he’s malnourished and showing signs of prolonged vitamin D deficiency from lack of sunlight.

There’s evidence of old fractures that healed improperly, ribs, left wrist, several fingers.

Scarring consistent with repeated physical abuse.

She paused, choosing her words carefully.

There are also indicators of sexual trauma.

We’ve documented everything for the police investigation.

Rivka made a sound like a wounded animal.

Mosha’s face went gray.

The immediate concern is his lungs.

This wasn’t his first near drowning.

There’s scarring in the lung tissue from previous water aspiration.

We’re monitoring his oxygen levels closely.

Dr.Chen’s expression softened.

Psychologically, he’s in severe shock.

He hasn’t spoken at all.

This is common with prolonged trauma and isolation.

He’ll need extensive therapy.

Can we see him? He’s been moved to room 314.

He’s sedated now.

His body needs rest.

You can sit with him, but please let him sleep.

They were about to head to Aby’s room when Detective Brennan arrived with a younger partner.

I’m sorry to do this now, he said, but we need your official statements while everything is fresh.

There’s a conference room we can use.

In the sterile hospital conference room, the partner set up a digital recorder while Detective Brennan opened a thick file.

Tell me everything from this morning, he said gently.

They recounted it all.

The discovery at the lake, Donald’s appearance, the encounter at the hardware store, following them back to Lake Tamson.

When they finished, Rivka asked, “What did they say? Did they confess?” Detective Brennan’s jaw tightened.

Donald hasn’t said a word.

Complete silence.

But Rohan? He shook his head.

No remorse whatsoever.

He seemed proud of what they’d done.

“What happened to our boys?” Mosha asked, though part of him clearly didn’t want to know.

According to Rohan, on September 13th, 1996, Donald picked up your sons as usual, but he’d promised them a treat.

The new playground near the school had just opened.

Told them it was a secret reward for being the best behaved children on the bus.

Rivka closed her eyes, picturing her trusting boys.

They always sat in the back.

So after the other children got off, he told them to hide on the bus floor.

Instead of going to school, he drove to a pre-arranged meeting point where Rohan was waiting.

Transferred them to Rohan’s car, gave them drugged candy.

Rohan had prepared a soundproof bunker at a cabin deep in the woods.

Off-grid, no official records.

They kept the boys there for 11 years.

Mosha’s voice was hollow.

Initially, yes, Donald and Rohan took turns caring for them.

The detectives pause spoke volumes.

Rohan let slip that others were involved, used we several times, but won’t identify them.

We believe there’s a larger network.

My friend Maurice, she’s a journalist.

She’s been investigating this neo-Nazi network, and I believe she can help you, Rivka said, taking a deep breath.

But tell me, why our boys? The neo-Nazi cell.

Most of the followers believe Jewish families are invading towns like Tene.

Your sons were symbols to them, a way to strike at the next generation.

What happened to Eliov? Detective Brennan consulted his notes.

3 years in, he tried to escape.

Donald panicked, restrained him too forcefully while Rohan struck him with a wooden beam.

Between the choking and the head trauma, he didn’t need to finish.

They weighted his body in a barrel and sunk it in Lake Tamson, Avi witnessed it all.

Rivka sobbed.

Mosha’s hands clenched into fists.

After that, Avi was kept in near total isolation.

No light, no education, no human contact except again that terrible pause.

The abuse continued for 11 years.

The Nazi items we found this morning, best guess, they were cleaning house, getting rid of evidence, thought the lake would hide everything forever.

The symbolism, Nazi memorabilia with Jewish children’s belongings, that was intentional.

After signing statements and answering more questions, they finally made their way to room 314.

Through the small window, they could see Avi sleeping, looking impossibly young and fragile despite being 19.

They settled into chairs outside, neither ready to go in yet.

“I want to knit again,” Rivka said suddenly.

“Remember those little shawls I made when they were babies? I want to make one for Avi.

” He is a young man now I know but something that says home.

Moshe nodded understanding.

I need to go to temple speak with Rabbi Goldstein.

We should say kadesh for Elaf properly now and and make a prayer of thanksgiving that Avi came home.

They sat in silence, hands clasped, drawing strength from each other as they’d done for 11 years.

The horror of what had been done to their children was almost unbearable.

But they would bear it because Avi needed them whole.

We survived this, Rifka whispered.

Somehow we’ll survive what comes next.

Together, Mosha agreed.

Through the window, Avi stirred slightly in his sleep.

They watched him breathe, each rise and fall of his chest, a small miracle.

Their family would never be complete again, but what remained would be cherished, protected, and slowly carefully healed.

News

Ilhan Omar ‘PLANS TO FLEE’…. as FBI Questions $30 MILLION NET WORTH

So, while Bavino is cracking down in Minnesota, House Republicans turning the heat up on Ilhan Omar. They want to…

FBI & ICE Raid Walz & Mayor’s Properties In Minnesota LINKED To Somali Fentanyl Network

IC and the FBI move on Minnesota, touching the offices of Governor Tim Walls and the state’s biggest mayors as…

FBI RAIDS Massive LA Taxi Empire – You Won’t Believe What They Found Inside!

On a Tuesday morning, the dispatch radios in hundreds of Los Angeles taxi cabs suddenly stopped playing route assignments. Instead,…

Brandon Frugal Finally Revealed What Forced Production to Halt in Season 7 of Skinwalker Ranch….

The Secret of Skinwalker Ranch became History Channel’s biggest hit. Six successful seasons documenting the unknown with real science and…

1 MINUTE AGO: What FBI Found In Hulk Hogan’s Mansion Will Leave You Shocked….

The FBI didn’t plan to walk into a media firestorm, but the moment agents stepped into Hulk Hogan’s Clearwater mansion,…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage… It started like any other evening…

End of content

No more pages to load