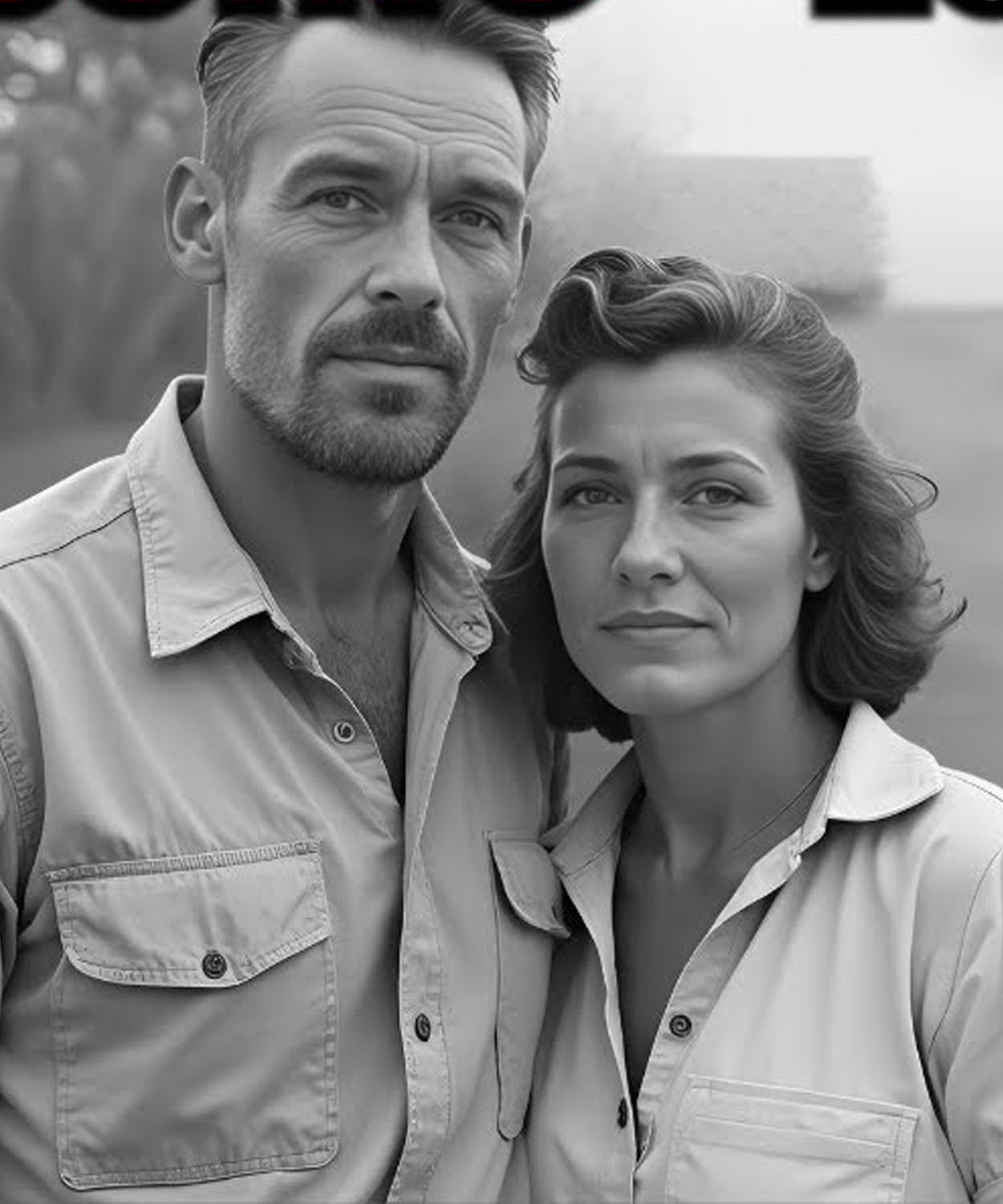

78 years ago, a middle-aged couple living quietly in the small town of Gonzalez, Louisiana, vanished from their home on a summer night.

No trace, no note, leaving behind a house locked tight, and their car still sitting in the garage.

Authorities at the time suspected foul play, but with no bodies, no evidence of a crime, and the investigation quickly hitting a dead end, the case was filed away as an unresolved missing person’s matter.

Yet for decades afterward, local folks never stopped talking about that house where many believed the truth had never been fully buried.

Then one day, nearly 60 years later, when a cold case unit investigator was reviewing the old files, she spotted a tiny detail in the crime scene photos that everyone before her had overlooked.

A detail that could upend the entire case and reveal a truth no one could have imagined.

July 1947.

The town of Gonzalez, Louisiana, lay quiet among sugarcane fields and flooded swamp land, the air thick with heat and the smell of wet earth.

The main road cut through town and out to a sparsely settled neighborhood where the Barton Hamilton family lived in a two-story white painted wooden house with a faded gray tin roof.

Barton, 41, worked as an accountant at a small lumber mill near the river.

His wife Christine, 38, took in sewing for the shop at St.

Theresa’s Catholic Church.

and their 22-year-old son Charles, considered the best educated kid in the area, was studying engineering in Baton Rouge.

The Hamiltons kept to themselves, but were seen as a model family.

Everyone off to their own business in the morning, gathering in the little kitchen at night to listen to the radio and talk about crops, lumber prices, or Charles’s classes.

They rarely went out, yet were always polite and often helped by neighbors when needed.

In early July, the town was gearing up for the fourth.

Flags hung along the streets.

The church got a fresh coat of paint on its fence, and the Hamiltons had even tied a few red, white, and blue ribbons across their front porch.

That night, the air was stifling, heat rising off the ground and mixing with kitchen smoke.

Neighbors noticed the Hamilton’s lights stayed on later than usual.

Some later recalled hearing a door open and slam shut, something heavy drop onto the floor, then nothing but silence.

A light rain started, enough to drown out any other sound.

When dawn came, the street was still quiet.

No sign of life from the White House.

Curtains were drawn tight, no smoke rose from the chimney, and Barton’s black Ford sat untouched in the garage.

The milkman passed by and thought it odd that yesterday’s bottles were still on the step.

By midm morning, one of Christine’s friends stopped by to return some fabric.

Knocked repeatedly.

Got no answer.

Walked around back.

Kitchen door locked too.

Unne spread fast in a small town.

A whole couple missing from first light.

Was almost unheard of.

Neighbors checked for Charles.

No sign of him in the yard either.

People started asking if anyone had seen the Hamiltons leave or heard them mention going anywhere.

Everyone shook their heads.

By noon, under a brutal sun, a few relatives showed up, tried the front door, the back door, everything locked from the inside.

They shouted, “No reply.

” Whispers raced down the little street, mixing with the drone of cicas and the smell of wet earth from the night rain.

Finally, when every attempt to reach them failed, a neighbor walked straight to the police station downtown to report that Barton and Christine Hamilton and apparently their son had vanished.

No one knew where and their house had gone eerily silent.

The report was logged and Sheriff Walter Duvil took the case.

That afternoon, he left headquarters with a deputy in the old Plymouth and drove the dirt road south to the Hamilton place.

On the way, he remarked how the air still hung heavy after last night’s rain.

Gray clouds covering the sky.

When the car stopped in front of the White House, several neighbors were already waiting at the gate, faces tight with worry, eyes tracking every move the lawman made.

Duvil walked through the gate and scanned the yard.

Grass still wet.

A few shallow shoe prints in the soft dirt.

Yesterday’s milk bottles on the step.

Front door shut.

Curtains closed.

No sound from inside.

He knocked three times.

Nothing.

The deputy circled to the back.

Kitchen door locked from the inside.

No primarks.

Duvil crouched by the front lock undisturbed.

Paint around the edges unscratched.

In the garage, Barton’s black Ford sat exactly where it belonged.

A thin layer of dust on the hood, tires settled in the same tracks.

No sign any other vehicle had been there.

Duvil jotted preliminary notes, called out one more time.

Only hollow echoes answered.

As he turned away, the front door suddenly cracked open and Charles Hamilton stepped out.

Shirt wrinkled, hair messy, looking exhausted.

He said he’d been home all morning and assumed his parents had left early the previous day for a cabin on Lake Morapas with two friends.

Duvall asked for the friend’s names.

Charles was vague, said they were work contacts of his fathers, couldn’t recall addresses.

Duvall wrote it down then asked to step inside.

Charles reluctantly agreed and moved aside.

Living room tidy, two cold coffee cups on the dining table, newspaper open, tablecloth undisturbed.

Duvil walked the hallway, checked every room, windows locked from inside, beds made flat, no signs of struggle or anything moved.

In the master bedroom, closet closed, no missing suitcases, Christine’s jewelry box untouched.

He had the deputy photograph everything and mark object positions.

The place was too neat.

It unsettled him.

Back in the living room, he pressed Charles for more details about the trip, departure time, transportation, who picked them up.

Charles answered slowly, voice, even no visible emotion, or panic.

Duvil watched him closely, then closed his notebook.

He found no evidence of crime, yet he couldn’t shake the wrongness of the house frozen in a half-finished moment.

No trace of people about to leave town.

On the porch, he checked the locks again, scanned the yard and fence.

Nothing but heavy silence and late afternoon light on the wet steps.

He had neighbors witness and sign the report confirming doors locked from inside.

House orderly, no forced entry, vehicle in place.

The first report was finished on the spot with the temporary conclusion.

Missing cause unknown.

As he packed up, Duvil looked back at the house one last time.

No sound except wind in the trees and the faint creek of the metal gate, as if the place itself was hiding something he couldn’t yet name.

Back at headquarters, Sheriff Walter Duval spent the afternoon verifying everything Charles had said.

According to the son, Barton and Christine left early to spend a few days at a cabin on Lake Marupas, picked up by friends in their own car.

Duval pulled records of rentals around the lake.

nothing under Hamilton or anything matching the description.

Cabins back then were watched by locals.

No one remembered seeing a couple that fit.

He phoned the Livingston Parish Sheriff’s Office.

No traffic incidents involving Barton’s car or anyone matching their description.

No recent accidents on the roads either.

He checked with Barton’s lumber mill.

Barton hadn’t shown up since yesterday morning and never missed work without calling out of character.

The foreman said no one at the mill knew any friends by the names Charles had vaguely mentioned.

Duval noted companions unverified, no planned or confirmed trip.

He called the church sewing shop where Christine worked part-time.

She had orders due by the weekend and had never mentioned leaving town.

A coworker said Christine was supposed to drop off finished pieces the previous morning to get paid.

No sign she was packing or going anywhere.

Duval sent men door to door again.

Neighbors confirmed the Hamilton’s lights were on late, but no one actually saw them leave.

One man three houses down thought he heard a car pass around midnight, but wasn’t sure whose.

Back at his desk, Duval compared everything to the scene report.

Nothing supported the idea.

Barton and Christine had left Gonzalez.

The Ford’s tires showed no fresh tracks, engine stone cold, hadn’t moved in at least 24 hours.

Barton’s personal journal recovered from the house.

Last entry 2 days earlier.

Call accounting office.

No mention of any trip.

Post office confirmed.

No unusual mail in or out.

Piece by piece, the picture contradicted the son’s story.

Charles insisted his parents left willingly.

No one else could confirm it.

Duval stared out the window at the darkening sky and rewrote the initial report.

Crossing out missing cause unknown and adding preliminary verification complete.

No evidence subjects left locality.

Recommend expanded search phase.

He closed the file, told the deputy to ready a search team, and sent formal notice up to the Ascension Parish Sheriff’s Office.

missing person’s case.

Gonzalez, Louisiana search to commence.

The next morning, after clearance from the parish, Sheriff Walter Duval launched a full-scale search around Lake Moripa, the supposed final destination.

Notices went to every local department, calling in auxiliary police, water rescue teams, and civilian volunteers.

Local hunters showed up with flat bottom boats, spotlights, and tracking dogs.

A quick briefing was held in the station yard.

Duval laid a big map across a patrol car hood and divided the lake into sectors with red pencil.

West side sheriff’s deputies south and northeast hunters and volunteers open water.

Two rescue boats.

Objective any sign of a cabin vehicle or belongings tied to the Hamiltons.

At sunrise, the teams moved out.

The road to Lake Morapas twisted through swamp, thick trees on both sides, insects buzzing, air heavy with mud.

Duval rode in the lead boat, a small wooden skiff with an outboard along with two deputies and a local hunter.

The water was dark, the surface mirror flat under a gray sky, tall reads blocking the view.

The hunter occasionally pointed west to old logging trails now overgrown, wide enough years ago for a car, but swallowed by grass.

On shore, dog teams worked the few dry ridges, but most of the area was flooded and treacherous.

By noon, the north and west sectors were cleared.

Nothing.

Duval called a break and set up a checkpoint at the treeine to collect reports.

Road patrols checked highways for any strange vehicles from the night in question.

Also nothing.

Rescue boats kept probing the water with poles and drag nets.

Duval noted terrain conditions, deep mud bottom, sudden drop offs, dark pockets deeper than 10 ft, slow current but dangerous undertoes, he wrote.

Dense swamp, limited access, need more small boats and local guides.

By afternoon, the southern team returned with a few random finds.

White painted scrapwood, a rusted tin can, old rope.

none relevant.

No cabins existed in the area, no tire tracks, no roads to the shore.

Hunters confirmed the place had been empty of structures for years.

As the sun dropped behind distant trees, Duval called it for the day, had teams mark searched areas with bamboo stakes and red cloth, then stood alone on the bank, staring across the flat water, turning copper in the sunset.

No cabin, no vehicle signs, no witnesses.

Every lid deadended exactly where he’d hope for answers.

In his daily log, he wrote, “No secondary scene located.

Area vast, swamp, deep, visibility poor.

Recommend expanding search radius 10 mi around lake.

” As the teams pulled out, outboard motors and barking dogs faded into the dusk, leaving only wind and dark water reflecting a thin moon.

like the lake itself was refusing to answer the question.

The whole town still couldn’t.

The next morning, the search resumed with an expanded scope toward the southwest of Lake Morapas, where the water was deeper and thick with reeds.

A team of local hunters along with two police officers was dispatched in wooden boats to sweep the low shoreline, the area where currents typically washed up debris and floating objects.

The sky was hazy with mist, the sunlight dull as it reflected off the mudsented surface of the lake.

Duval stood on the command boat, observing and noting the coordinates marked with bamboo stakes.

Around midm morning, one of the search boats radioed that they had spotted a strange object caught in the reeds at the western edge of the shore.

Duval immediately directed his boat to the location.

When they arrived, they discovered a small dark object, half buried in the wet grass, covered with a thin layer of mud.

A woman’s medium-sized leather handbag, its brass clasp already rusted.

Duval ordered no one to touch it until the scene was photographed.

Then it could be collected.

An officer wearing rubber gloves carefully lifted the bag from the grass and placed it on a metal tray.

The bag was closed, its surface caked with mud, undamaged with the strap intact.

Duval closely examined the direction of the current and noted that the mud was heavier on the front side, indicating the object had drifted from the shore rather than from the middle of the lake, he wrote, likely thrown from the western shore.

Less than 24 hours ago, the bag was opened for a preliminary inspection on site under a tarp.

Inside were a small wallet, a few paper bills, business cards printed with the name Barton Hamilton, accountant, address Gonzalez, along with a set of metal keys attached to a wooden tag engraved with the letter H.

There was also a handkerchief embroidered with the initials ch and a lipstick tube with a broken cap.

Everything was neatly placed in the tray and photographed item by item according to procedure.

Duval leaned in for a closer look.

The bottom inside the bag was dry, only the edges damp, and the mud smell was fresh.

He concluded the bag could not have been floating long, and was likely thrown in recently.

When he asked the search team, no one recalled seeing the object the previous day, even though the western shore had already been given a preliminary sweep.

That detail caught Duvall’s particular attention.

He ordered a seizure report drawn up, assigned the temporary evidence code E4703, signed it on the spot, sealed the bag in a designated cloth evidence bag, and a fixed and Ascension Parish sheriff’s seal.

An officer filmed the entire process.

Duval stood at the edge of the reads, watching the slowmoving murky water, sensing something was off.

The location where the bag was found did not match the wind direction or current from the previous night, meaning the object had not drifted from far away, but was most likely placed there intentionally.

He had the shoreline checked and found faint adult footprints leading down from the dirt road, but the mud had dried and was not clear enough to identify the shoe type.

Duval ordered the area cordoned off within a 50 m radius to search for additional related items, but they found only a few rotten leaves and drifting trash.

Once finished, he had the evidence transported back to headquarters and handed over to the technical division.

That afternoon, in the parish’s temporary laboratory, the handbag was reopened under bright white light.

The preliminary report confirmed no traces of blood or biological tissue.

The mud on the exterior matched soil samples taken from the western shore.

No standing water inside the bag, indicating the object had not been fully submerged, but was thrown or placed near the water’s edge.

The business cards and keys matched information in the Hamilton file.

Duval recorded the findings in the day’s consolidated report.

Personal handbag belonging to Christine Hamilton discovered on the western shore of Lake Morapas.

No damage, no signs of theft, likely discarded from the shore.

No cabin or vehicle located within the search area.

After signing the report, he circled in read the final note.

First authenticated evidence, possible criminal connection.

In a brief meeting with the search team leaders, Duval announced a temporary halt to water surface, dragging to focus on the western shoreline and shifted the case status from missing persons cause unknown to missing persons suspected criminal activity.

He looked down at the worn map where a red circle marked the handbag’s discovery point, isolated amid the vast expanse of reads.

For the first time since taking the case, Duval felt the line between a simple disappearance and a criminal investigation beginning to blur.

In the report sent to the parish office, he ended with based on evidence item E4703, the Hamilton case is reclassified for special investigation.

Search of the Lake Morpa’s area will continue with expanded scope the following day.

As soon as the first piece of evidence reached headquarters, Sheriff Walter Duval spent the entire evening reviewing the full file and the statements Charles Hamilton had provided.

He spread out the map of the Lake Mora’s area, marked the handbags location, and compared it to the routes out of Gonzalez that Charles had described in the initial interview.

The statement claimed Barton and his wife left home in a friend’s car heading north along the Levy Road, then taking a small highway toward the Lake region.

However, highway patrol reports confirmed no witnesses had seen an unfamiliar vehicle in that area that night.

Gas stations and roadside stores were questioned.

No one had seen a couple matching their description.

Duval also sent inquiries to neighboring parishes, Livingston and Tangipoa, asking for information about any couple traveling with a younger person in recent days, but all responses were negative.

He reread the onseen report inside the Hamilton house.

No suitcases, no luggage, no signs of preparation for a trip.

Based on that, Duval concluded the vacation cabin story was becoming increasingly implausible.

Meanwhile, Christine’s handbag had been found at Lake Moras with no signs of robbery or theft, making voluntary departure highly unlikely.

He summoned Charles to the station for another session, this time formally as the primary informant in the missing person’s case.

The interview took place in a small office with only Duval and a notetaking assistant present.

Duval reasked about the departure time, who they left with, the vehicle, and why the parents chose to leave on a holiday.

Charles repeated most of what he had already said.

They went with his father’s friends, an acquaintance couple from Baton Rouge, early the previous morning.

He stayed behind to watch the house.

Duval pressed for more details about the cabin, on which shore it was, any name or distinguishing features, but Charles said he had never been there, and only heard his parents mention it.

When informed that no cabin was registered under the Hamilton name or any known associates, Charles paused, then said his father might have rented it through someone else.

Duval looked him straight in the eye and asked about the last time he saw his parents.

When exactly did they leave the house? Charles said when he woke up they were already gone and had only left a note on the kitchen table.

But when Duval asked where the note was, he replied, “I probably threw it away after reading it.

” That answer was recorded verbatim in the transcript and underlined in red ink.

After the interview ended, Duval sat rereading every line.

Every detail Charles provided was unverifiable.

No witnesses confirmed seeing them on the road, no cabin existed, and no vehicle was observed leaving the Hamilton house in that time frame.

Neighbor reports stated the house lights remained on until late, then went dark, but no one heard an engine start.

A woman living across the street clearly recalled stepping onto her porch around midnight because her dog was barking.

She saw the front door closed and no headlights shining from the garage.

All those statements when cross referenced with the still parked Ford and the handbag found near the lake convinced Duval that Barton and Christine Hamilton never left Gonzalez in the manner their son described.

He compiled all the data into a summary table with three columns.

Statement verification results discrepancies.

The first column listed Charles’s account of the trip and the mysterious friends.

The second recorded responses from lodges, local authorities, and witnesses around the lake.

The third simply read, “No match.

Does not exist.

No witnesses.

” When the table was complete, the final note contained only one line, “No evidence of departure from the area.

” Duval understood this could no longer be treated as an ordinary missing person’s case.

He closed the file, pulled a formal form from the drawer, and filled in the new case title, Hamilton missing person’s suspicious case.

With black ink, he underlined the word suspicious to emphasize the special status.

In his duty log for that day, he added a few lines.

Victim’s son’s statements lack supporting evidence.

No couple confirmed encountering the Hamiltons in the Lake Morupp area.

Neighbors confirmed no vehicle left the house.

Based on evidence and scene cross checks, case reclassified as suspected criminal.

Duval carefully set the file aside, looked up at the wall map where Lake Morapas was circled in red.

Every road from Gonzalez to the lake had been checked, and there was no trace except for that one small handbag.

In his mind, a hypothesis was forming, not yet solid enough to voice, but strong enough to convince him that something terribly wrong had happened inside that white painted house on the hot night the whole town still believed had been peaceful.

After completing the case reclassification paperwork and submitting the report to the parish office, Sheriff Walter Duval decided to take the next step, obtain an official search warrant for the Hamilton family home.

The collected facts showed clear contradictions between statements and evidence and verifying the scene had become necessary to either rule out or confirm criminal suspicions.

The warrant was approved by the district court the following morning, authorizing a full search of the residents and surrounding property.

Duval arrived with two officers and a forensic technician just after sunrise.

The neighborhood was still quiet.

The White House looked exactly as it had on their first visit.

He ordered temporary barricades set up, restricted access, and invited a neighboring resident to witness the unlocking.

After confirming all windows were locked from the inside, Duval had the front door opened with Charles Hamilton’s key.

The moment they stepped inside, the air felt heavy with dampness and smoke.

Dim light filtered through thick curtains.

He instructed no one to touch anything until the entire interior was photographed.

The assistant set up the Roliflex camera and began documenting every corner.

In the living room, they found the small coffee table tipped over, one leg broken, a fresh crack visible.

Beneath it, the rug bore a palm-sized brownish stain, evenly spread and darker than the fabric.

Duval crouched to examine it, shown a flashlight close, and noted unidentified stain, possibly dried liquid.

He had the technician cut out the stained section of rug and seal it in an evidence bag.

On the dining table, the two coffee cups remained exactly as he had first seen them, now covered with a thin layer of dust, confirming no one had touched them in days.

In the corner, the brick fireplace still held light colored ash.

The surface was fine and had not yet turned completely gray.

Duval asked the technician who confirmed the ash looked recent and unusual mixed with tiny metal fragments and bits of ceramic.

He used tweezers to collect several pieces into a vial labeled A471.

An additional ash sample was taken for comparison.

Shining the light deeper into the hearth, Duval detected a strange burnt smell, not entirely that of burning wood.

He recorded the detail in his notebook.

Continuing through the dining room and hallway, they found no missing items or signs of forced entry.

In the master bedroom, the bed was neatly made, but small porcelain shards lay on the floor, possibly from a broken cup.

He collected them, labeled B472.

Charles’s room was tidy.

Nothing unusual except a cardboard box containing technical books and a few drawings.

The entire downstairs was photographed from four angles.

Every piece of potential evidence was marked with a ruler and identifier on the floor.

When the team moved to the back porch, Duval noticed a small scratch on the door frame, knee high, with slight paint flaking, but not enough to determine the cause.

He scraped off a bit of paint and wood with a thin blade, and sealed it separately.

The entire morning passed in near silence, broken only by camera shutters and the rustle of the technician’s notes.

By midday, the interior search was complete, and the samples were sealed in four separate bags.

The stained rug, ash, and metal fragments from the fireplace, porcelain shards from the bedroom, and the door frame wood sample.

All were signed by Duval and counter signed by the witness.

He stood in the living room one last time, surveying the house.

Everything appeared carefully arranged.

No chaos, no obvious signs of violence.

Yet the perfect stillness gave him the feeling that real evidence had been hidden beneath this tidy surface.

Before leaving, Duval had the technician reseal the doors and a fixed police tape.

A temporary scene report was written on site describing overturned coffee table, brownish stain on rug suspected to be liquid, fresh ash in fireplace containing metal fragments, no signs of break-in, furnishings intact.

As he left the house carrying the evidence bags, they felt heavier than their actual weight.

He knew the small fragments collected that morning might be the first, albeit faint, clues to what had happened inside that quiet home on the night two people suddenly vanished.

The samples collected during the Hamilton house search were carefully sealed by Sheriff Walter Duval and sent the next morning to the state forensic laboratory in Baton Rouge.

The unit equipped to handle complex or unclear cases with the most advanced analytical equipment available at the time.

The receiving officer opened and invented each bag.

The stained rug, ash mixed with metal fragments, porcelain shards, and doorframe sample.

Each item was refographed and assigned its own code.

Duval personally signed the transfer, emphasizing the brownish stain on the rug and the fireplace ash as the two most significant points.

He left the lab with instructions to contact him the moment preliminary results were ready.

During the waiting days, he continued reviewing statements and search maps, but no new leads emerged.

By the end of the week, the lab telegraphed that analysis was complete and requested his presence for the detailed briefing.

When Duval returned to Baton Rouge, the chief technician, a man about his age, led him to a small conference room where the processed samples and typed report lay on the table.

According to the report, the brownish stain on the rug did not react to reagents for human or animal blood, yielding only a neutral result.

possibly some other dried organic substance such as coffee, wine, or mineral-rich water.

There was no confirmation of blood.

The fireplace ash showed unusual composition, higher than normal calcium levels, traces of lime compounds, a small amount of iron oxide, and metal impurities.

The technician explained, “This could occur if wall plaster or ceramic items had been burned in the fireplace, but the exact source could not be determined.

The recovered metal fragments were brass alloy, too small to identify the original object.

The bedroom porcelain shards were simply from a broken cup, unrelated to any organic material.

The door frame wood showed no traces of violence or foreign paint, only natural scratching.

The report concluded there was no definitive evidence of criminal activity or signs of a crime inside the Hamilton residence.

The findings were stamped and signed by the three responsible technicians.

Duval read every line repeatedly, then asked to re-examine the ash under a microscope.

He noticed tiny white particles mixed with the black ash, but the technician confirmed they were plaster fragments that could have fallen during normal fireplace use.

Duval made a private note.

Ash with high calcium, abnormal source undetermined.

Despite his lingering suspicion, he had to accept that the analysis provided no basis to open a criminal investigation.

No blood, no signs of violence, no direct evidence.

Under state regulations, the case could only be upgraded with concrete proof of injury or death.

Duval signed for the return of all evidence, repackaged it in sealed containers, and transported it back to the Ascension Parish evidence vault.

On the drive back to Gonzalez, he sat in silence.

Afternoon light filtering through the windshield onto the thick file resting on his lap.

He understood the investigation had to pause at the verification stage, and any further effort would require new information.

At headquarters, he opened the evidence cabinet, placed the box in the lock section, and labeled it Hamilton lab results.

Inconclusive.

In that day’s duty log, he wrote, “Boten Rouge forensic report shows no blood traces.

Ash contains calcium and lime.

No criminal evidence.

File paused at monitoring level.

insufficient legal basis for criminal investigation.

Then he closed the log, leaned back in his chair, and felt the familiar weight of a case with no clear direction, where the collected fragments still refused to form a complete picture.

In the quiet room, lit only by the ticking clock and the fading lateday sun on the wooden desk, Duval knew that for now the Hamilton case would remain classified as an undetermined disappearance, and all his questions would have to wait for answers that might never come.

The report from Boten Rouge yielded no results that could advance the case, but Sheriff Walter Duval still couldn’t shake the feeling that something was off in Charles Hamilton’s statement.

2 days after receiving the lab findings, he sent a summon for Charles to come back to the station for a second interview, aiming to test the consistency between his story, and the circumstantial evidence already collected.

The interrogation took place in the small room at headquarters, with only Duval, a note-taking deputy, and Charles present.

The atmosphere was quiet, broken only by the steady tick- tock of the wall clock.

Duval began with the familiar questions.

What time his parents left the house, who drove them, what they took with them.

Charles repeated that his parents had left early in the morning, picked up by a friend of his father’s to go to a cabin on Lake Morpas, taking two small suitcases, and a grocery bag.

Duval jotted notes and pressed for details about the suitcases, color, size, who carried them.

Charles hesitated, then said, “One was brown, the other maybe blue.

” Duval compared this to the search inventory, which clearly stated no suitcases were missing, the closets were intact, clothes neatly folded.

He pointed this out and asked if perhaps his parents had left the suitcases in their friend’s car.

Charles just nodded and added nothing more.

Duval moved on to Christine’s purse, found at Lake Mora.

When he mentioned the business cards and keyring inside, Charles looked surprised and said, “Maybe mom took a different purse, not that one.

” Duval paused, made a quick note, then asked how many similar purses his mother owned.

The answer was vague.

I don’t remember, probably two or three.

She changed them a lot.

Duval kept probing about the last time Charles saw his parents.

He said they were already gone when he woke up, leaving only a short note on the kitchen table.

Duval asked if he still had the note.

Charles said he threw it away after reading it because it just said they were going away for a few days.

Duval wrote down the exact wording and underlined it in red ink just as he had before.

He asked another question in the house.

Who usually locked the door when leaving? Charles answered, “Usually my dad.

” But when Duval asked why the door had been locked from the inside when he arrived, Charles didn’t answer right away and finally said, “Maybe his parents locked it by mistake and left through the back.

” Even though Charles himself had already confirmed the back door was locked, too.

Duval wrote down the detail, slowly read it back to Charles and asked him to confirm.

Charles stared at the table and nodded reluctantly.

Throughout the interview, Charles’s voice stayed steady, not trembling, but it lacked naturalenness.

His answers were evasive and occasionally contradicted themselves.

When Duval pressed for more about the friend who had driven his parents, Charles repeated, “They were friends from Baton Rouge.

I don’t really remember.

My parents said they knew them from work.

” Duval asked for a description of the person or the car.

Charles said, “I think it was a gray car, a sedan.

” Then a few minutes later corrected himself, “Maybe blue.

” Duval looked up and stared at him without speaking, then signaled the deputy to write it down.

He understood that these inconsistent details were by themselves already undermining the entire story.

After more than an hour, Duval moved to the summary, reading back each point, and asking Charles to sign the statement.

Charles signed without further comment.

Duval watched his expression as he left the room, eyes down, gate calm but slightly tense.

When the door closed, Duval sat still, staring at the thick notes.

Everything was at the level of suspicion.

Nothing direct.

Christine’s purse, the ashes in the fireplace, the brown stain on the rug, all vague, nothing conclusive.

He knew he couldn’t hold Charles just on a bad feeling.

There was no legal basis to link him to anything.

Before closing the report, Duval added a short line in his duty log.

Second statement, inconsistent, lacking specifics, but no direct evidence.

Subject released.

Continue monitoring.

He closed the notebook, looked out the small window behind his desk, where the late afternoon light cast a dim stripe.

The Hamilton case, though it had moved a few steps forward, still felt like a road disappearing into fog.

Every trace dissolved the moment it seemed within reach.

In the weeks following the second interview, Sheriff Walter Duval continued directing searches around Gonzalez, but nothing changed.

No new witnesses, no tire tracks, no bodies or additional belongings turned up.

The evidence file sent from Baton Rouge was reviewed multiple times.

Every analysis reached the same conclusion.

No definitive criminal element.

Highway patrol units stopped sweeping the roads and the Lake Morasa search team disbanded after finding nothing beyond a few pieces of driftwood and trash.

Local papers had run short articles about the mysterious disappearance of a Gonzalez couple, but no one had more information.

Duval, still suspicious, understood the case had reached the limit of what the law allowed him to pursue.

One long afternoon, he sat in his office reviewing the entire file.

Scene reports, photographs, search maps, Charles’s statements, lab reports, everything stacked into a thick folder that was nevertheless empty of real answers.

No evidence of a crime, no grounds for an arrest warrant or further investigation.

Under pressure from superiors, he was forced to draft the report, closing the initial investigation phase.

In the summary sent to the Ascension Parish Office, the typed conclusion read, “No bodies recovered, no new physical evidence, no proof of criminal activity.

Conclusion, disappearance undetermined.

” The file was assigned case number 471 17 and moved to temporary storage in Baton Rouge.

Duval signed last, stamped it with the red Paris sheriff seal, feeling both unfinished and powerless.

The Hamilton case, once the focus of attention in the early days, was quickly replaced by routine matters, thefts, fires, land disputes.

The Hamilton’s neighbors stopped talking about it.

The white painted house gradually became abandoned, grass overgrowing the walkway.

Charles Hamilton stayed there a few more weeks, then sold the house to a distant relative, and left Louisiana.

Immigration records showed he moved to Texas without leaving a forwarding address.

Duval made a short note in his pocket notebook.

Victim’s son left the state.

Case no progress.

That fall, he sent a letter to state police requesting the Hamilton file remain on a watch list in case new information surfaced.

A reply came weeks later will be retained and reopened upon new data.

From then on, file 4717 sat untouched in storage in Baton Rouge, its cover bearing only three lines.

Hamilton, Barton, and Christine, missing persons, 1947.

No one mentioned it again.

No supplemental reports, no updates.

Duval still thought about the case on late night shifts, staring at the reflection of street lights on rows of old files in the cabinet.

He always felt he had missed something in that White House.

One small detail that could have changed everything, but time and procedure had stripped him of the authority to dig deeper.

When 1947 ended, the final report on the Hamiltons was filed under unresolved missing persons alongside dozens of others who had left town and never returned.

The folder grew thinner over time, paper yellowing, ink fading, and the name Hamilton gradually slipped from the memory of anyone who had once known them, leaving only a few dry lines in the register.

No bodies recovered, no additional evidence.

Case closed.

The Hamilton file lay undisturbed in the Baton Rouge archives for many years after the initial investigation was closed.

Occasionally during routine audits, a clerk would open the metal cabinet, check the index, add a new sticker, and slide it back into place.

No one requested updates.

No new information arrived.

The 1950s and 1960s passed.

Gonzalez changed with paved roads, and the old lumber mill where Barton had worked changed owners.

The Hamilton disappearance survived only as a vague old story among the elderly.

Sheriff Walter Duval served nearly two more decades, retiring in 1968.

He always called it the only unfinished case of my career.

He died in 1972, taking his private notes with him, unread.

The Hamilton’s White House passed through multiple owners, was renovated and reconfigured, but no one knew that behind its walls and under its floors had once been the scene of an unsolved disappearance.

As for Charles Hamilton, tax records showed he settled in Texas, later moved to Oklahoma, worked odd jobs in mechanics, never married, had no criminal record, and died of lung disease in 1982, buried on the outskirts of Tulsa.

With the death of the last family member, the case effectively vanished from community memory.

Related documents faded, printed ink turned silver, scene photos lost color, some pages stained brown by humidity.

When archavists conducted inventory in the early 1990s, they noted original evidence deteriorating.

Digitize when feasible.

That work, however, waited many more years.

In 2005, the state of Louisiana officially established the cold case unit under the Criminal Investigation Bureau, tasked with reviewing all unsolved disappearances and homicides from the previous century.

The project was federally funded to pilot DNA technology and digitize records.

At the new headquarters in Baton Rouge, thousands of old case files were transferred from parish offices and lined the shelves.

During sorting, Inspector Megan Crowell, 39, was assigned the pre1,950 missing person’s group.

She was experienced in reconstructing cases from faint evidence and incomplete files, having worked on several data recovery projects.

Among the yellowed folders, she noticed a thin one typed on the cover.

Hamilton Barton and Christine, Missing Persons, 1947.

The jacket bore a faded red stamp.

Disappearance undetermined.

In the lower right corner was the barely visible seal of the Ascension Paris Sheriff’s Office.

Inside, besides the summary report, there were only a few blurry photos and carbon copies of the 1947 Baton Rouge lab results.

The black and white pictures of the White House, the overturned coffee table, the fireplace, and the rug with dark streaks made Megan linger longer than usual.

She read every line of the old reports, noting the description’s unidentified brown stain and ash containing calcium and lime.

At the end was Walter Duval’s signature and a private note in blue ink.

Something’s not right, but can’t prove it.

The file was categorized as suspicious, insufficient criminal data.

Under cold case guidelines, files showing irregularities or retaining testable evidence were prioritized for re-evaluation.

Megan added Hamilton to the first 30 cases for review, marking the physical evidence present column in red.

She requested the old evidence locker transfer the entire sealed box coated 47 beggan for re-examination.

On the box lid, unidentified was stamped in black ink beside a frayed evidence tape.

When she lifted the lid for a preliminary check, the smell of damp paper and age wafted out.

Inside were cloth bags containing rug cutings, ash, metal fragments, all still bearing Duval’s labels and signature.

Among more complex and famous cases, Hamilton was a small overlooked file, but its very silence made Megan choose it.

She wrote in her work log, beginning re-evaluation of 1947 Hamilton disappearance, suspicious file.

When she turned off the office lights that evening, only the old yellow folder remained on her desk, now clipped to a fresh print out clearly titled Cold Case Unit preliminary review.

In her first days at the cold case unit, Inspector Meghan Krell spent most of her time in archives rereading the Hamilton file.

It was thin but full of details that troubled her.

It opened with the 1947 scene report describing overturned coffee table, brown stain on rug, fresh ash in fireplace.

The accompanying photos showed numbered evidence markers in ink.

Yet when Megan compared them, she noticed discrepancies.

The angle of the coffee table did not match the stain’s position on the scene diagram.

According to the report, the brown stain was in the middle of the room, nearly 2 m from the fireplace, but in the photos, it appeared right against the wall beneath the window.

She enlarged the images, compared shadows to determine light direction, and concluded the photos were taken from a completely different angle than described, possibly due to poor coordination between the notetaker and photographer or deliberate repositioning.

Additionally, a handwritten note in blue ink on the lab report copy read item destroyed W.

Duval next to the entry for rug section and ash.

Under 1947 procedure, evidence could only be destroyed with commanding officer approval, yet no supporting document existed.

Megan paused a long time over that line, then lightly underlined it in pencil.

She continued to the old report’s conclusion, “No criminal element detected.

Case closed, disappearance undetermined.

” In the attached copy of Sheriff Duval’s final duty log was a handwritten line, “Something’s not right, but can’t prove it.

” For Megan, the existence of two conflicting details, evidence marked destroyed without documentation, and the lead investigators expressed suspicion was enough to question the integrity of the entire case.

She created a two column comparison chart, 1947 description, and actual scene photos.

While comparing, she discovered the ash location in the fireplace also failed to match the notes.

The photos showed light colored fine ash with tiny white flexcks and metal fragments, unlike ordinary wood ash.

The 1947 lab report noted calcium and lime content, but offered no explanation.

Megan wrote, “Composition unexplained, possible error or deliberate omission.

” She reprinted the photos, circled questionable areas in red, paying special attention to the hearth tiles.

In one image, a small semic-ircular crack was visible.

As if the area had once been pried open and resealed to confirm, she pulled the original property plat.

The house still stood, renovated multiple times, but structurally intact.

Megan contacted the current owners, an elderly couple who had bought it in the 1980s.

During the conversation, the husband recalled that around 1998, while repairing the chimney, he had found a thick layer of strange white ash under the hearth tiles that he had to scrape out before retiling.

He thought it was old lime or brick dust and had no idea of the house’s history.

That detail made Megan write boldly in her notebook.

White ash layer confirmed witness statement.

Back at headquarters, she reported her preliminary findings to her supervisor and requested the Hamilton case be moved to the priority excavation list to verify any remaining physical evidence.

In her formal proposal to the cold case chief, she outlined three points.

First, clear contradictions between 1947 descriptions and seen photos regarding evidence location and characteristics.

Second, the unexplained item destroyed.

Duvo note lacking legal basis.

Third, the current owner’s information about an unusual white ash layer potentially linked to the original sample.

The proposal ended with request warrant for excavation and examination of the Hamilton fireplace area.

After review, the chief agreed the case met criteria for reinvestigation due to recoverable physical evidence.

Preliminary excavation approval was granted and forwarded to legal for court permission in Ascension Parish.

As Megan signed the bottom of the document, she felt the familiar chill that came whenever an old case was about to open.

The mixture of excitement and unease, as if beneath nearly 60 years of ash and dust, something was still waiting to be seen for the first time.

Once the excavation warrant was approved, the cold case unit forensic team together with Ascension Parish deputies went to the former Hamilton house.

That morning, the Baton Rouge sky was overcast.

Wind off the Mississippi carried dampness that made the air thick and heavy.

The technical team consisted of six people.

Inspector Megan Crowwell, a geologist, a fire materials forensic specialist, and two assistants.

The area was fully cordoned off.

The owners temporarily moved out for the duration.

The living room with the fireplace was cleared of furniture and draped with plastic sheeting to contain dust.

The lead forensic officer read the work plan aloud.

Objective: Examine hearth and fireplace cavity.

Collect ash, tile, soil, and combustion residue samples.

Identify any organic or bone traces.

Each member signed the area unsealing law.

Megan stood back watching as technicians began removing the facing tiles.

The old red bricks cracked and crumbled, mortar dust falling to the floor.

When the mortar was pried away, a layer of fine pale gray ash appeared, thicker than normal for a standard fireplace.

The technician scooped portions into stainless trays with a metal spoon, measured depth, and log.

First ash layer, 3.

5 cm thick, light color, high looseness.

The ash was then sifted under bright light.

Megan leaned in and saw a tiny shiny flexcks inside, not sand or gravel.

Under magnification, they were flat and round, smooth surfaced, mixed with thin half burned fibers that looked like cloth.

Everything was bagged separately and labeled H471A.

When the second layer was removed at about 10 cm deeper, one technician heard a small clink against the tool.

They stopped and carefully extracted with tweezers a cloudy white fragment the size of half a coin.

Porous, lightweight, edges rough.

The technician examined it, measured with calipers, and said quietly, “Porous structure like bone.

” Megan immediately ordered photos, recorded the exact coordinates, and placed the fragment in an evidence box.

She added to her log, “Suspected bone fragment, fireplace cavity, 12 cm depth, northeast corner.

” Continuing through two more layers, the team recovered three additional similar fragments, a rust stain eaten into a brick and clumps of charred fiber.

Each sample was collected, weighed, and documented separately.

A chemist dripped phosphate reagent.

The solution changed color faintly, indicating calcium phosphate, characteristic of human bone material.

No one spoke, only the scratch of pens and the sound of hand tools on brick.

When the final hearth layer was lifted, total depth reached 20 cm.

The bottom surface showed unnatural cracks, as if it had once been opened and resealed with old cement.

The geologist confirmed the cracks were not natural.

Through her safety goggles, Megan saw two thin black metal wires mixed into the cement block, possibly binding wire or bent pins.

She ordered the entire 20 kg cement block removed intact for separate examination.

Every movement was filmed and timestamped.

After nearly eight continuous hours, excavation was complete.

In total, they recovered eight primary samples, ash, bricks, subfloor soil, lime powder, four small bone fragments, two pieces of rusted metal, and charred cloth fibers.

All were sealed in specialized containers labeled cold case unit 4721, signed by the officer in charge.

Before leaving, Megan did a final scene check.

the empty brick hearth frame, late sunlight filtering through dust and casting silver streaks.

She ordered overall photos and marked the exact excavation coordinates on the house diagram.

As the team packed tools, the forensic lead the day’s log aloud.

Every entry was verified.

Start 810, finish 1635.

All evidence sealed, nothing missing.

The climate controlled transport van waited outside.

Duval was long gone.

Everyone originally involved had passed away.

Yet now, after nearly 60 years, the first tangible traces had appeared in the very room, where in 1947 they had written, “Nothing unusual.

” When the van doors closed, Megan signed the final entry of the day, Hamilton House fireplace, excavation completed.

Evidence transferred to New Orleans DNA Lab for analysis.

Seal number CC4721.

On the drive back, the van moved slowly through the quiet neighborhood, wind rustling the trees, red dust clinging to the side mirrors.

Inside the sealed cargo area, the fragile white fragments lay protected by three layers of tape.

The brittle remnants of a past that for the first time finally had a chance to speak for itself.

The samples recovered during the fireplace excavation were transferred to the DNA identification laboratory of the Louisiana State Forensic Science Center in New Orleans.

The following morning, a handover document was signed between the cold case unit representative and the lab director, marking the first step in the in-depth analysis phase.

At the laboratory, technicians began sorting each sample four small bone fragments, two pieces of rusted metal, ash samples, and charred fabric fibers.

Under the scanning electron microscope, the structure of the opaque white fragments became clearer.

They were neither ceramic nor limestone, as some had predicted.

The surface was porous, showed me narrow cavities, natural fracture lines, and tested positive with organic phosphate reagents.

The lead technician confirmed they were human bone.

To determine sex, they used chromosomal quantification.

Results indicated the samples belong to a female.

DNA extraction was performed using partial burnt tissue extraction techniques.

After 3 days, the lab obtained a DNA sequence long enough for comparison.

While awaiting results, Megan Crowell contacted civil registry offices to locate living relatives of the Hamilton family.

After weeks of searching, she found a distant relative of Barton named Mitchell Hamilton living in Florida, a grandson through a cousin branch.

He agreed to provide a blood sample for comparison.

The sample was sent via special courier to New Orleans accompanied by valid identity verification.

When the data was entered into the system, the comparison showed the bone fragment DNA matched 99.

84% with the female Hamilton genetic line.

The result was double-cheed and confirmed by two independent laboratories.

The report concluded sample H471A originates from a female individual of Hamilton lineage.

Probability of random match less than 1 in 10 million.

Immediately upon receiving the information, Megan went to the lab to sign the confirmation document.

She looked at the data string on the screen, then shifted her gaze to the small bone fragment now sealed in a plastic case.

The first direct physical evidence in a disappearance case spanning nearly six decades.

In her report to the cold case unit chief, she wrote, “DNA identification confirms the sample is female human bone matching, the Hamilton lineage.

Victim identified Christine Hamilton.

Attached was the formal request to reopen the case under new file number CC4721.

That same afternoon, an emergency meeting was held at cold case headquarters in Baton Rouge.

Representatives from technical, forensic, and the state prosecutor’s office attended.

Megan presented the excavation process, test results, and genetic evidence.

After hearing the report, the prosecutor concluded that the Hamilton case was no longer an unresolved missing person’s matter, but had shifted to suspected homicide with physical evidence.

The decision to reopen the file was approved on the spot, along with directives to expand the investigation to related factors, including the possibility of additional victims, motive, and evidence concealment.

Access to all 1947 Ascension Parish archived records was authorized.

Original documents from crime scene reports to Walter Duval’s personal log were digitally scanned for comparison.

That night, Megan sat alone in her office, staring at the stack of old files next to the freshly printed DNA report.

Between two layers of paper, separated by more than half a century, the story seemed to close where it began.

the white painted house, the fireplace, and the ashes.

Now, the cold numbers of the lab had turned suspicion into legal fact.

Christine Hamilton did not vanish.

She died in that house, and the light colored ash once dismissed as lime and calcium was the last remnant of a human body.

Megan wrote in her duty log on October 14th, 2005.

Female victim identified.

Hamilton file reopened.

Statewide investigation expanded as she closed the folder.

Night had fallen outside and light rain began to fall on the rooftops of Baton Rouge, washing away the dust of time from a case thought forever buried.

After the DNA results confirmed the victim was Christine Hamilton, and the case was officially reopened.

Detective Megan Croll focused on reviewing all remaining old physical evidence stored in the state archive.

She noticed that the 1947 file mentioned numerous numbered exhibits, but most were no longer in the original sealed containers, including metal fragments vaguely described as unidentified alloy.

To locate them, Megan went to archive 3C, the physical evidence storage area for unresolved cases.

Rows of dusty steel cabinets stretched out, each compartment labeled by year and parish.

After hours searching the catalog, she discovered an old envelope in slot 241, sealed with H47, exhibit 3 written in the corner.

The ceiling wax had faded, but the faint signature W.

Deval was still legible.

There was no description of this exhibit in the original inventory, which immediately caught her attention.

She contacted the archive supervisor to open the envelope under the supervision of two witnesses and video recording.

When the thick paper was peeled back, inside was a rusted brass 12- gauge shotgun shell.

The primer blackened, the base faintly stamped Remington.

The item was placed in a stainless tray, photographed, and resealed.

On the rim of the shell was an uneven black streak as if it had been exposed to high heat.

Megan cross-referenced the 1947 report.

No entry mentioned recovering a shell casing.

The existence of the exhibit 3 envelope proved evidence had been separated from the official file.

She noted in her interim report discovery of previously unrecorded evidence Remington 12 gauge shell code H47.

The sample was immediately sent to the Baton Rouge Ballistics Examination Lab.

Technicians gently cleaned it and examined it under an optical microscope.

The preliminary report confirmed the shell had been fired with clear firing pin impressions suitable for comparison.

At the same time, Megan searched the 1945 state personal firearm registry and discovered Barton Hamilton had registered a Remington sportsman 12 gauge shotgun serial type matching the recovered shell.

The gun was never reported missing or confiscated after the war.

Comparing the firing pin mark on the shell with manufacturer test samples, the lab determined high compatibility, likely the same weapon.

Additionally, the shell had adhering dark brown organic fiber traces.

Chemical analysis detected protein and hemoglobin insufficient for DNA profiling, but confirming human biological origin.

The report sent to cold case unit read, “Exhibit H47X3 fired Remington 12 gauge shell bearing human biological traces compatible with firearm registered to Barton Hamilton in 1945.

Attached were magnified photos of the scorched metal area where temperatures exceeded 600° C, indicating the round was fired in an enclosed space or near combustible material.

Upon receiving the results, Megan immediately saw the events connect.

Barton owned a matching gun.

The fired shell originated inside the house.

Christine was burned in the fireplace.

This suggested a scenario where Barton may have been shot, then Christine killed and cremated, or vice versa.

She presented the preliminary report to Cold Case Command, detailing the discovery process, comparison with 1947 records, and raising questions about why this evidence was separated from the original file.

The meeting’s interim conclusion, new evidence confirms violent firearm activity at the scene.

Female victim identified via DNA.

Male victim likely died from gunshot.

recommendation to expand search for ballistics related evidence and a second body.

Megan wrote the final line in the minutes based on physical evidence and analysis.

Preliminary conclusion Barton Hamilton shot Christine Hamilton’s body burned for disposal as she signed the red stamp cold case unit.

active investigation was affixed to the top of the page, marking the moment a nearly 60-year-old missing person’s case officially became a reopened homicide investigation.

After the ballistics results were confirmed and the new evidence entered into the file, Detective Megan Krel focused on reining witnesses mentioned in the old reports for additional supporting information.

The 1947 file briefly mentioned a name scribbled in an appendix, Sarah L.

described as the Hamilton family’s maid in the period before the disappearance.

No formal statement from her existed, only a marginal note, left Gonzalez.

August 1947, Megan began searching old census records, church registries, and residence permits, eventually locating a woman named Sarah Leblanc, born 1920, now living in a Baton Rouge nursing home.

She was 95, frail, but mentally sharp.

With permission from the facility and her legal guardian, Megan visited her for an interview.

That afternoon, sunlight streamed through the room’s window, illuminating old black and white photos from 1940s Gonzalez hanging by her bed.

When Megan mentioned Barton and Christine Hamilton, the old woman’s eyes lit up.

Her thin hand trembled as it rested on the blanket, and she spoke slowly but clearly.

She said she had worked part-time as a maid for the Hamiltons for over a year, coming twice a week to clean.

She described Barton as calm and Christine as gentle, always asking about her son.

When asked about the night of the disappearance, Sarah paused for a long time, then nodded and said she remembered that night clearly because it was unlike any other.

According to her, Barton came home early that afternoon, and Charles seemed tense.

When she left, the sky was threatening rain and the air smelled of smoke.

She insisted that about an hour later, while walking past the neighborhood on her way home, she heard a loud muffled bang coming from the direction of the Hamilton house, like a gunshot, but stifled.

She turned to look.

The house lights were still on, but minutes later, they went out.

The next morning, curious and worried, she returned for her usual cleaning shift, but the door was locked and no one answered.

Around noon, she saw Charles in the backyard dragging something heavy and long, wrapped in cloth or a blanket toward the rear of the property.

When she called out, he turned pale and shouted that his parents had gone away and she wasn’t needed that day.

His voice shook, his movements frantic.

Sarah said she felt scared and left quickly, but that image haunted her for life.

A few days later, when she heard police were investigating, she went to Sheriff Walter Duval and told him everything she had heard and seen.

Duval took her into his office, wrote a few lines, then told her no need to tell anyone else.

It could cause trouble for the family.

He said the matter was being looked into, and advised her to stay quiet.

She understood and never spoke of it again.

When Megan asked why she was willing to talk now, Sarah gave a weak smile and said, “It’s time people knew the truth.

” She agreed to sign an official statement, which was recorded and documented on site at the nursing home.

It confirmed three key details.

Hearing a gunshotike explosion from the Hamilton house the night of the disappearance, seeing Charles dragging a suspicious wrapped object the next morning, and reporting it to Sheriff Duval, who asked her to remain silent.

Megan verified timing and distance.

Sarah’s house at the time was only three blocks away, easily within earshot.

She added the full statement, recording, and witness photos to the new file under code CC4721.

The official report stated, “Witness Sarah LeBlanc, former Hamilton maid, confirms hearing a gunshot the night of the disappearance and observing son Charles transporting a suspicious object the following morning.

statement never recorded in 1947, officially documented in 2005.

At the end of the session, Megan thanked her, shook her hand, and left in silence.

Outside, Sunset painted the old rooftops orange.

She paused to jot a final note in her notebook, closing the day.

First living witness statement, confirms gunshot and suspicious transport of heavy object.

High credibility.

additional basis for homicide and body concealment hypothesis.

Immediately after documenting Sarah Leblanc’s statement, Detective Meghan Crowell decided to expand the search area around the former Hamilton house, focusing on the rear yard where the witness saw Charles dragging the suspicious object.

Based on the 1947 property diagram, that area had been a small garden, later paved with concrete and used for a shed.

With support from the Cold Case Forensic Team and Ascension Parish Crime Scene Unit, Megan obtained a supplemental search warrant and initiated a full survey using metal detectors and ground penetrating radar.

Early that morning, the backyard was cordoned off with yellow police tape.

The magnetic scanner moved slowly, emitting steady beeps in the quiet air.

Just 2 hours later, the device registered strong signals at three adjacent points near the eastern fence.

Technicians carefully excavated with small trowels and uncovered a 20 cm rusted metal piece with broken teeth, a sawblade fragment still bearing faint dark stains.

Nearby was a deformed round metal tube once cleaned of mud.

It was clearly a broken 12- gauge shotgun barrel section.

Matching the Remington type Barton had registered.

A few hand widths away, they recovered a steel kitchen knife with a charred wooden handle, bent, and chipped blade.

All items were photographed, coordinates logged, and placed in evidence bags.

At the temporary analysis table, technicians noted the saw blade and knife showed high temperature burn marks and were coated in black carbon, indicating direct fire exposure.

The broken barrel was deformed at the edges and internally corroded, consistent with heat and moisture damage.

Carbon residue scraped from the saw blade tested positive for human protein and hemoglobin traces.

Mud on the knife contained charcoal and calcium phosphate compounds identical to the fireplace ash samples.

Megan received the preliminary report that same afternoon.

Evidence broken saw blade, kitchen knife, shotgun barrel section, bare human biological traces, and charcoal.

DNA from residue matches victim Christine Hamilton.

Confirmation from the New Orleans lab arrived one week later, verifying the tools had direct contact with human tissue and organic burning.

The saw blade was broken at a high stress point, indicating forceful cutting of hard material, while the deformed knife was likely thrown into the fire with organic remains for disposal.

The barrel fragment matched the previously recovered Remington shell, confirming the same weapon type.

Megan compiled a summary report stating, “Ite recovered behind the Hamilton house bear biological traces of victim Christine.

Fracture and deformation patterns indicate use in dismemberment and body disposal.

Preliminary conclusion, perpetrator used on-site tools to destroy the body within the property.

When presented to cold case command, the state prosecutor ordered a comprehensive evidence integration team and full cross referencing of all items from 1947 to 2005.

The crime scene map was updated.

Excavation sites marked with red dots.

Fireplace, wall base, rear garden, all within a 20 square meter radius.

Megan stood before the map, watching the small dots connect a case dismissed nearly 60 years earlier.

She wrote in her investigation log, “Murder and disposal tools found on site.

All traces indicate premeditation, not impulse.

Need to continue identifying who used these items at the time of the incident.

” As night fell, the technical team packed up flood lights illuminated the dug up ground where soil mixed with charcoal and metal faintly reflected the beams.

Megan lingered for a long moment before leaving.

The faded image of the old maid’s testimony echoing in her mind.

Gunshot, heavy object, and a silent fire burning through the night in a house no one realized was erasing a human life.

The new discoveries in the Hamilton backyard drove Detective Megan Kryle to re-examine all original 1947 administrative records, especially documents bearing Sheriff Walter Duval’s signature.

While comparing them, she noticed that many reports, evidence transfer forms, and technical notes carried the signature W.

Duval, but the handwriting was not entirely consistent.

Some were firm and right slanting, others shaky and disjointed as if written by a different person.

Most strikingly, a marginal note reading item destroyed.

W.

Duval on the 1947 forensic report was written in a marketkedly different hand left slanting heavy downstrokes and lacking Duvall’s habitual flourish on the tail of the D seen in other official records.

Megan requested a forensic document examination.

The report concluded high probability that two different individuals signed as W.

Duval on 1947 documents.

This discovery led her to suspect someone had tampered with the original file after the case was closed.

Searching old Ascension Parish personnel records.

She learned Walter Duval had a son, Raymond Duval, born 1925, who worked as a local court clerk from the 1960s to 1980s and was now 80, living in Lafayette.

Further checks revealed Raymond had been assigned custody of the parish judicial archive from 1970 1975, the exact period when many old unresolved case files, including Hamilton, were transferred and reorganized.

Megan immediately noted the significant coincidence.

The sheriff’s son had full access to files his father had created.

To verify, she traveled to Lafayette and visited the old court archive where Raymond had worked.

The current manager said, “Mr.

Duval had retired over 20 years ago and lived alone in a suburban house, but still occasionally visited and was allowed access to non-classified materials.

Archive logs showed Raymond signed out files coded 47317 Hamilton twice in 1971 and 1973 right around the time Sheriff Walter Duval died and the Hamilton file was transferred to Baton Rouge.

This raised suspicion that Raymond may have removed or altered contents before official transfer.

Megan reported the findings to her superiors and received authorization to open a separate investigation into possible tampering, concealment, or destruction of evidence.

She contacted state law enforcement for a search warrant for Raymond Duval’s residence targeting documents, evidence, or personal notes related to the Hamilton case.

Before filing, she met with the Louisiana State Prosecutor’s Office, presenting the full chain of discoveries, signature discrepancies, Raymond’s position and access, and timing alignment with the separation of exhibit 3.

The prosecutor agreed there was sufficient probable cause to suspect unlawful interference with public records.

The search warrant was approved on December 2nd, 2005, authorizing the cold case unit and Lafayette Parish Police to inspect Raymond Duval’s home, outuildings, garage, and basement.

Megan joined the execution team, bringing all original files for on-site comparison.

When the convoy arrived in Lafayette, night had fallen.

The quiet neighborhood was still Raymond’s gray wooden house nestled among old oaks.

Before entering, Megan paused, looking at the rusted D initial on the porch name plate, then signaled the forensic team to prepare.

The warrant was read aloud, the door opened, and the search officially began, its objective, to determine whether the sheriff’s son had indeed been involved in concealing or destroying evidence in the Hamilton case.

The search of Raymond Duval’s house began at 8:00 the next morning under the supervision of the Lafayette Parish prosecutor.

The two-story wooden house sat at the end of a narrow road surrounded by ancient oak trees with a locked old shed behind it.

The forensic team divided into three groups.

One checked the ground floor, one handled the upper floor, and Megan along with the document technician took the basement area.

The interior was covered in dust.

The walls were hung with old black and white photographs and numerous paper items were stacked in wooden crates.

After nearly an hour of searching, the upstairs team discovered a metal filing cabinet labeled 1940 1950 containing many administrative envelopes.

Most were old court files, but in the bottom drawer was a small wooden box with the recessed carving, each 47.

When it was brought downstairs, the box was heavier than expected, its surface worn, the lock rusted.

The prosecutor ordered it opened on site in the presence of three law enforcement officers.

Inside, a gray cloth covered a stack of black and white photographs, a few loose sheets of paper, and a small leather-bound notebook.

Megan put on gloves, and carefully opened it.

The first photograph showed the fireplace, the exact one in the Hamilton house, taken from a different angle than the photo preserved in the 1947 case file.

In the picture, the brick floor was still intact, covered in ash, and in the lower right corner was the blurred silhouette of a person wearing a rolledup sleeve shirt, face unrecognizable.

At the bottom edge of the photo was handwriting before ceiling, debuted.

Beneath the photo were three yellowed loose sheets written in careful handwriting with the same ink as the documents in the old file.

One of them read, “They must not know.

stay silent to protect the boy.

In the lower right corner was the signature W.

Duval.

The phrase the boy made Megan freeze.

In the context of 1947, the boy could refer to Charles Hamilton, who was only 23 at the time, or possibly to Raymond Duval’s own son.

She turned to the second note, the handwriting more scrolled.

It has all gone too far.

I’m doing this to save him from prison.

Below that was a short list of three items.

One, rug destroy.

Two, ashes.

Keep small portion.

Three, photos.

Only one copy.

In the lower right corner of the last sheet was a faint stamp from the Ascension Parish Sheriff’s Office.

Everything was photographed and sealed on the spot.

In the leatherbound notebook, the early pages contained Walter Duval’s personal notes, mostly duty logs, but toward the end was a long passage written in blue ink, dated to coincide with the closing of the Hamilton investigation.

They wouldn’t understand.

He was scared.

I could see it clearly.

All the evidence would be against him, but he only panicked.

I can’t let him lose his whole life in prison for what happened in a moment of rage.

The wording was vague, but sufficient to reveal intent to interfere.

When the document technician compared these notes with samples kept at the Baton Rouge archives, the handwriting analysis concluded the writing matched exactly the authenticated samples of Walter Duval.

There was no doubt about authenticity.

This evidence showed that the sheriff had personally recorded the destruction of evidence and deliberately altered records to prevent criminal prosecution.

Inside the lid of the wooden box, a small piece of paper glued with dried adhesive bore the faint words, “Store separately, RD,” indicating that Raymond Duval had kept the box.

After his father’s death, Megan signaled the team to photograph it, seal everything in the box, and prepare an on-site inventory with time, signatures, and sequential numbering of each item.

When they reread the note that said, “Stay silent to protect the boy.

” No one in the group spoke, they only looked at each other in silence.

If the boy really was Charles Hamilton, then the 1947 case was not just a crime that had been covered up, but a deliberate cover up by the head of the investigating agency himself.

Megan clearly felt this was the missing piece of the entire story.

The reason the Hamilton file had been hastily closed, evidence had disappeared, and the truth buried for nearly six decades.

A preliminary report of the house search was prepared the same day.

Seized wooden box engraved H47.

Inside crime scene photos and handwritten notes by Walter Duval, content admitting destruction of evidence and motive for concealment.

Handwriting analysis confirms match with Duval samples.

Evidence proves intentional interference and destruction of evidence.

As they left the old house, the sunset stretched across the quiet road.

Megan held the file tightly in her hands, knowing that the trembling lines written by an aging sheriff had opened a new chapter in a case long thought closed.

A chapter not only about crime, but about people who chose silence to protect what they believed was right, even at the cost of burying the truth for more than half a century.