In August of 2018, 32-year-old software developer Jacob Brennan set out on a 3-day solo camping trip in Olympic National Park, Washington.

He planned to hike the Enchanted Valley Trail and spend time disconnecting from his demanding job at a tech startup in Seattle.

Jacob told his younger brother that he would be back by Monday evening.

But when Tuesday came and there was no word from him, his apartment remained empty and his phone went straight to voicemail.

By Wednesday morning, his brother filed a missing person report with the Jefferson County Sheriff’s Department.

What followed was a search operation that turned up nothing, a case that went cold within weeks, and a discovery 2 months later that would disturb everyone involved.

A discovery so strange that even seasoned park rangers would struggle to explain what they found deep in the restricted zones of the Olympic wilderness.

The morning of August 10th, 2018 was cool and overcast on the western edge of Olympic National Park.

According to the weather station at the Graves Creek Ranger Station, the temperature at 6:00 in the morning was around 52° F, typical for late summer in the temperate rainforest zone.

It was at this time, according to the automated gate log, that a silver Honda Accord registered to Jacob Brennan passed through the entrance near the Graves Creek trail head.

The vehicle was recorded by the park’s basic entry system, which tracks license plates for safety and management purposes.

There were no signs of irregular behavior.

The car was parked neatly in the designated area, and according to a volunteer who was cleaning the information kiosk that morning, Jacob appeared calm and prepared.

He was wearing a dark green rain jacket, hiking boots, and carried a medium-sized backpack with a sleeping bag strapped to the bottom.

The volunteer later told investigators that Jacob asked a few questions about trail conditions and whether the river crossings were safe.

She remembered him because he was polite and seemed experienced, not like someone attempting his first backcountry hike.

Jacob did not sign the trail register, which was optional, but recommended.

This became a point of frustration later during the search as it meant there was no official written record of his intended route or estimated return time.

However, his brother provided details during the initial missing person interview.

Jacob had mentioned wanting to reach Enchanted Valley, spend one night there, then loop back through a smaller side trail to avoid retracing his steps.

The route was around 24 mi total, manageable for someone in good physical condition over 3 days.

According to the timeline reconstructed by investigators, Jacob was last seen in person around 8:30 in the morning by a pair of hikers from Portland who were heading back toward the trail head.

They passed him on a narrow section of the trail about 2 mi in.

One of the hikers recalled that Jacob was moving at a steady pace and gave a quick nod as they went by.

There was no conversation, no indication of distress, and no one else nearby.

That sighting was the last confirmed human contact Jacob Brennan had with the outside world.

By the time his brother began trying to reach him on Monday, August 13th, Jacob’s phone had already been off the network for more than 2 days.

The mobile carrier’s records showed that the last ping from his device came at 11:47 on the morning of August 10th near a cell tower that covers the lower portion of the Enchanted Valley Trail.

After that, the phone either lost signal, was turned off, or the battery died.

All three scenarios were common in the back country, so the data alone did not raise alarms.

But when Jacob failed to return home by Tuesday evening, his brother knew something was wrong.

Jacob was methodical, the kind of person who set reminders and stuck to schedules.

He would not simply extend a trip without letting someone know.

On Wednesday, August 15th, the brother drove to Jacob’s apartment in the Fremont neighborhood of Seattle.

The landlord confirmed that Jacob had not been seen since the previous Friday.

His mail was piling up and his car was not in its usual spot.

The brother then contacted the Jefferson County Sheriff’s Department and filed a formal missing person report.

Because Jacob had gone into a national park and there was a clear timeline of when he should have returned, the case was immediately forwarded to the National Park Service.

A search operation was authorized that same afternoon.

The search began early Thursday morning, August 16th, with a coordinated effort involving park rangers, AK-9 unit from the Washington Search and Rescue Council and a helicopter provided by the Coast Guard.

The operation was based out of the Graves Creek Ranger Station, the same location where Jacob’s car had been found, still parked and undisturbed.

Inside the vehicle, rangers discovered a duffel bag containing a change of clothes, a phone charger, and a half empty bag of trail mix.

Nothing appeared to be missing or out of place.

The keys were not in the ignition, which suggested Jacob had taken them with him, a standard precaution.

The initial search focused on the Enchanted Valley Trail and its immediate surroundings.

Teams swept the main path, checked campsites, inspected river crossings, and called out Jacob’s name at regular intervals.

The K9 units were given a scent article, a t-shirt retrieved from Jacob’s apartment, and were deployed along the most traveled sections of the route.

According to the incident report filed later that week, the dogs picked up a scent near the trail head and followed it for about 3 mi before losing it completely near a rocky clearing where the path splits toward the valley floor.

The handlers noted that the scent loss was abrupt, which sometimes happens near water or in areas with heavy foot traffic, but it provided no further leads.

On the second day of the search, a helicopter equipped with thermal imaging flew over the valley and surrounding ridge lines.

The crew reported no heat signatures that matched a human being, no signs of campfires, and no visible disturbances in the vegetation that might indicate someone had gone off trail.

The forest in this region is dense, filled with Douglas fur, western hemlock, and thick undergrowth of ferns and salal.

Visibility from above is limited even with modern equipment.

One ranger later wrote in his field notes that searching the Olympic back country is like searching for a needle in a haystack except the haystack is 100 square miles and constantly wet.

By the end of the first week, more than 60 people had participated in the search.

Volunteers combed secondary trails, checked abandoned campsites, and distributed flyers with Jacob’s photo at every trail head within a 10-mi radius.

His brother appeared on local news, pleading for information.

The segment included a description of Jacob, his last known location, and a tip line.

A few calls came in, mostly from well-meaning hikers who thought they might have seen someone matching his description, but none of the leads went anywhere.

Every sighting either predated his disappearance or could not be confirmed.

On August 23rd, after 9 days of intensive searching, the official operation was scaled back.

This did not mean the case was closed, but it did mean that active field searches would no longer be conducted daily.

The park service issued a statement explaining that all reasonable efforts had been made and that the case would remain open pending new information.

Jacob’s family was devastated.

His brother continued private searches on weekends, hiring a local guide and retracing the same trails over and over, but the wilderness gave nothing back.

No clothing, no gear, no footprints.

It was as if Jacob Brennan had simply stepped off the trail and vanished into the trees.

In the weeks that followed, the case became one of dozens of unsolved disappearances in national parks across the United States.

Investigators reviewed Jacob’s background for any signs of mental health struggles, financial trouble, or personal conflicts that might suggest he had chosen to disappear.

They found nothing.

He had a stable job, good relationships with his family, no debt, and no history of risky behavior.

His social media accounts showed a normal life, posts about work projects, weekend hikes, and casual meals with friends.

There was no indication that he was planning to vanish.

By midepptember, the missing person file had been transferred to a long-term case folder.

It would be reviewed periodically, but without new evidence, there was little more the authorities could do.

Jacob’s face appeared on missing person websites and in databases maintained by organizations that track disappearances in wilderness areas.

His family held out hope, but as the days turned into weeks and the weeks into months, that hope grew quieter.

And then in mid-occtober, something happened that no one had anticipated.

Something that would pull Jacob Brennan’s case out of the cold file and into a category that had no precedent.

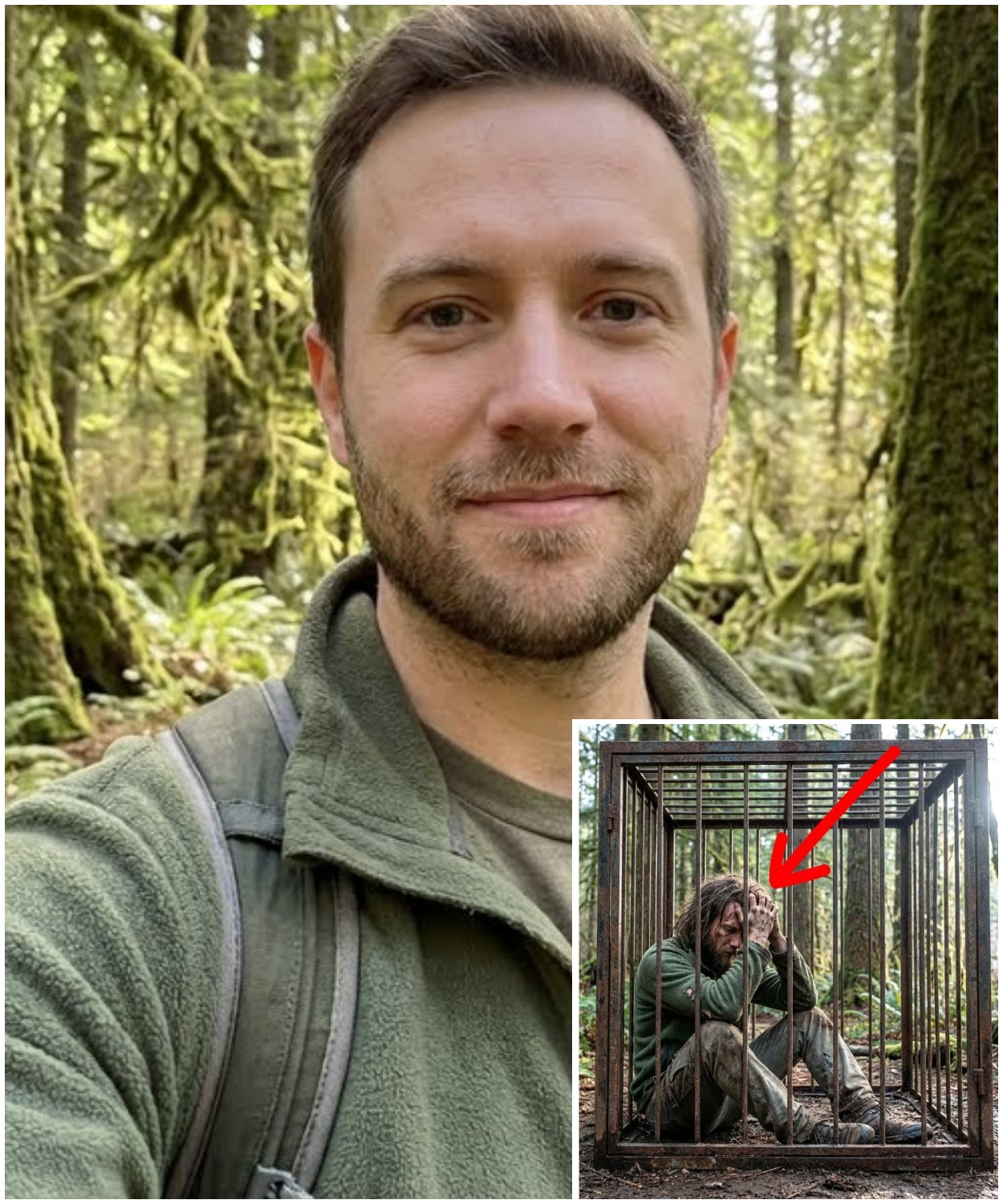

On the morning of October 14th, 2018, two contract wildlife biologists working for the US Forest Service were conducting a routine survey in a remote section of Olympic National Park, several miles northwest of the Enchanted Valley Trail.

The area they were inspecting was not open to the public.

It was a restricted ecological zone used primarily for research and conservation monitoring.

Access required special permits, and even then, visits were infrequent.

The biologists, a man and a woman, both in their late 40s, were tagging elk movement patterns and checking camera traps that had been set up months earlier.

According to their field report, they were moving along a narrow game trail through dense underbrush when they noticed something unusual about 50 yards ahead.

At first, they thought it was a piece of old equipment, maybe a forgotten trap or a section of fencing left behind by a previous research team.

But as they got closer, the shape became clearer.

It was a cage.

The structure was roughly 6 ft long, 4 ft wide, and about 4 ft tall, constructed from welded metal bars that had started to rust in places.

It looked industrial, like something used for animal transport or containment, but it had been modified.

The door was secured with a heavy padlock and the base was anchored to the ground with stakes driven deep into the soil.

Inside the cage, there was a man.

The biologists stopped immediately.

According to their written testimony, they did not approach right away because the situation was so unexpected and so far outside normal protocol that they were unsure whether it was safe.

The man inside the cage was crouched in the far corner, his back pressed against the bars.

He was filthy.

His clothes, a torn t-shirt, and what looked like the remains of hiking pants, were stained with mud, dirt, and something darker that might have been dried blood or waste.

His hair was long, matted, and hung over his face in tangled clumps.

His skin was pale beneath the grime, and his hands were wrapped around his knees, rocking slightly back and forth.

The moment the biologist came into view, the man began to scream.

Not words, just raw, high-pitched sounds that echoed through the trees.

He threw himself against the bars, shaking the entire structure, then retreated just as quickly, crawling backward and pressing himself into the corner again.

His movements were erratic, anim animalistic.

He did not seem to recognize them as people, or if he did, he was too far gone to respond in any coherent way.

The female biologist, whose name was later recorded in the incident report as Dr.

Laura Pittz, immediately radioed the ranger station.

Her voice, according to the audio log, was shaking.

She described what they were seeing, repeated the coordinates twice to make sure they were clear, and requested immediate assistance.

The dispatcher asked her to confirm whether the man appeared injured.

She replied that she did not know, that he would not stop moving long enough for her to tell, and that he seemed terrified or completely detached from reality.

While waiting for help, the two biologists kept their distance, but did not leave.

Dr.

Pitch tried speaking to the man in a calm voice, asking his name, asking if he could hear her, asking if he needed water.

There was no response.

He continued rocking, occasionally letting out guttural noises, and every few minutes he would lunge toward the bars as if trying to break through, only to collapse back into the corner.

His eyes, when visible through the hair, were wide and unfocused.

The other biologist, a man named Roger Spence, took photographs with his phone and a handheld camera used for field documentation.

Those images would later become part of the official evidence file.

They showed a human being reduced to something unrecognizable, caged like an animal in the middle of a forest where no one should have been.

It took nearly 2 hours for the first responders to reach the location.

The terrain was difficult, accessible only on foot, and the coordinates placed the site far from any maintained trail.

A team of four park rangers arrived first, followed 20 minutes later by two deputies from the Jefferson County Sheriff’s Department.

All of them later gave statements describing the same scene.

A man clearly in severe physical and psychological distress, locked inside a crude metal cage in an area where human presence was rare and unauthorized.

The rangers approached slowly.

One of them, a senior officer named Phil Avery, tried to communicate with the man just as Dr.

Pittz [clears throat] had.

He knelt a few feet from the cage, kept his voice low, and asked simple questions.

What is your name? Can you hear me? Do you know where you are? The man did not answer.

He stared at Avery for a moment, his mouth hanging open, then suddenly slammed his head against the side of the cage with enough force to cause a visible cut above his eyebrow.

Avery pulled back immediately and signaled for medical personnel.

It was clear that this was not just a case of someone being held captive.

This was a person in acute crisis, either from trauma, starvation, exposure, or some combination of all three.

The padlock on the cage was heavy duty, the kind used for storage units or industrial gates.

The rangers did not have bolt cutters with them, so they called for additional equipment.

While they waited, one of the deputies walked the perimeter of the site, looking for any clues about who might have built the cage or why.

There were no vehicles nearby, no trails leading directly to the location, and no signs of a camp or shelter.

The cage appeared to have been placed deliberately in a concealed spot, surrounded by thick brush and fallen logs that made it nearly invisible unless you were standing right next to it.

Near the base of the cage, partially buried under wet leaves, the deputy found a plastic water jug.

the kind sold at camping supply stores.

It was empty.

A few feet away, there was a small pile of food wrappers, granola bars, jerky packets, all opened and discarded.

It suggested that someone had been feeding the man, at least intermittently, but there was no indication of who that person was or when they had last been there.

When the bolt cutters finally arrived, Avery made the decision to open the cage.

Two paramedics stood by with a stretcher and a blanket.

The moment the lock was removed and the door swung open, the man inside did not move.

He stayed in the corner, staring at the opening as if he did not understand what it meant.

Avery spoke to him again, gently, explaining that they were there to help, that he was safe now, that no one was going to hurt him.

Slowly, carefully, one of the paramedics stepped inside the cage.

The man flinched, but did not resist.

He allowed himself to be wrapped in the blanket, though his body remained tense and his breathing was rapid and shallow.

When they guided him out of the cage, his legs buckled.

He had to be supported on both sides just to stand.

His feet were bare, covered in cuts and soores, and his toenails were overgrown and caked with dirt.

It was obvious he had been in that cage for a long time.

The paramedics placed him on the stretcher and began a preliminary examination.

His pulse was elevated, his body temperature slightly below normal, and he showed signs of severe dehydration and malnutrition.

There were bruises on his arms and legs, some old and faded, others more recent.

His wrists had deep marks consistent with restraints, though no restraints were found inside the cage.

When they tried to check his eyes with a light, he turned his head violently and made a choking sound, as if the brightness caused him pain.

They decided not to press further and focused on getting him out of the forest as quickly as possible.

While the man was being prepared for transport, Ranger Avery took a closer look at the cage itself.

He noted in his report that the construction was not amateur.

The welds were clean, the bars evenly spaced, and the anchoring system required tools and some level of planning.

Whoever built this knew what they were doing.

It was not something thrown together in a panic.

It was deliberate, functional, built to hold a person for an extended period.

Avery also noted something else.

There were scratch marks on the inside of the bars.

Dozens of them, thin lines where fingernails or something sharp had scraped against the metal over and over.

Some were shallow, others had gone deep enough to remove the rust and exposed bare steel underneath.

It painted a picture of desperation of someone trying to claw their way out day after day with no success.

The man was airlifted out by helicopter later that afternoon.

He was flown directly to Jefferson Healthcare Hospital in Port Towns and where he was admitted to the intensive care unit.

The staff there were briefed on the circumstances of his discovery but were told very little else because at that point no one knew who he was.

He carried no identification, no wallet, no phone.

His clothing had no labels that were still legible.

He could not or would not speak.

For the first 24 hours, he remained unresponsive to questions, staring at the ceiling or curling into a fetal position whenever anyone approached.

It was not until a nurse noticed a small scar on his left forearm, a jagged line that looked like an old injury, that someone thought to check missing person reports.

That scar had been mentioned in the file for Jacob Brennan.

His brother had provided a detailed description during the initial investigation, including the scar from a childhood accident involving a broken window.

When the hospital contacted the sheriff’s department and shared the detail, a detective immediately pulled Jacob’s file and compared the physical description.

Height, build, age, and the scar all matched.

Fingerprints were taken from the man in the hospital bed and sent to the state database.

The results came back within hours.

The man in the cage was Jacob Brennan.

He had been missing for more than 2 months.

And now he had been found locked inside a metal cage in one of the most isolated parts of Olympic National Park, unable to speak, covered in filth, and behaving like someone who had lost all connection to the world he once knew.

The discovery triggered an immediate shift in the investigation.

What had been a missing person case was now something far more disturbing.

Someone had taken Jacob Brennan.

Someone had held him.

and someone had left him there to be found or to die.

The question was no longer where Jacob had gone.

The question was who had done this to him and why.

The Jefferson County Sheriff’s Department opened a criminal investigation the same day Jacob Brennan was identified.

The case was classified as suspected kidnapping and unlawful imprisonment.

And because the crime had occurred on federal land, the Federal Bureau of Investigation was notified and assigned a field agent to coordinate with local authorities.

The lead investigator for the sheriff’s department was Detective Raymond Hall, a 17-year veteran with experience in violent crimes and cold cases.

Hull had worked missing person cases before, but nothing like this.

In his initial briefing to his team, he stated clearly that this was not a typical abduction.

The location, the method, and the condition of the victim all pointed to something more calculated and more disturbing than a crime of opportunity.

Jacob remained in the hospital for 5 days under medical observation and psychological evaluation.

His physical condition, though serious, was stabilized relatively quickly.

He was severely dehydrated and malnourished, having lost nearly 30 lbs since his disappearance.

The medical staff treated him for infected cuts on his feet, a mild case of hypothermia, and a skin infection that had developed from prolonged exposure to unsanitary conditions.

His wrists and ankles showed signs of repeated trauma, indicating that he had been restrained multiple times during his captivity.

But the physical injuries, while significant, were not the most troubling aspect of his condition.

It was his mental state that alarmed the doctors.

Jacob did not speak for the first 3 days.

He responded to his name only occasionally, and even then his reactions were minimal.

A slight turn of the head or a flicker of recognition in his eyes.

When nurses or doctors approached him, he would often recoil, pressing himself against the wall or pulling the blanket over his head.

He refused to make eye contact and became agitated whenever someone tried to touch him, even for routine medical procedures.

A psychiatric consultant brought in to assess him described his behavior as consistent with severe psychological trauma, possibly post-traumatic stress disorder, acute dissociation, or a combination of both.

The consultant noted that Jacob appeared to be stuck in a state of hypervigilance, as if he were still expecting harm.

On the fourth day, Jacob spoke his first words.

A nurse had brought him water and set it on the table beside his bed.

As she turned to leave, he whispered something so quietly that she almost missed it.

She stopped and asked him to repeat it.

He looked at her, his eyes glassy and distant, and said it again.

“You still out there?” The nurse immediately notified the medical team who in turn contacted Detective Hall.

Hull arrived at the hospital within the hour and requested permission to conduct a preliminary interview.

The doctors were hesitant, explaining that Jacob was not yet in a stable enough condition to undergo interrogation, but Hull assured them he would keep it brief and non-invasive.

He simply needed to know if Jacob could provide any information about who had held him and whether that person posed an ongoing threat.

The interview took place in Jacob’s hospital room with a nurse present.

Hull sat in a chair several feet from the bed and spoke in a calm, even tone.

He introduced himself, explained that Jacob was safe and asked if he felt able to answer a few questions.

Jacob did not respond immediately.

He stared at the wall, his hands clutching the edge of the blanket.

Hull waited.

After nearly a minute of silence, Jacob nodded once.

Hull began with simple questions.

Do you remember what happened to you? Jacob nodded again.

Do you remember who did this? Another nod.

Can you tell me his name? Jacob’s breathing quickened.

His hands began to shake.

He opened his mouth as if to speak, then closed it again.

Hull leaned forward slightly, careful not to crowd him.

“Take your time,” he said.

“You are safe here.

No one can hurt you now.

” Jacob’s voice, when it finally came, was broken.

“I do not know his name,” he said.

I never knew his name.

Hull asked him to describe the man.

Jacob closed his eyes.

He said the man was older, maybe in his 50s, with a thick gray beard and a deep voice.

He wore old work clothes, flannel shirts, and canvas pants, and he smelled like sweat and would smoke.

Jacob said the man never told him why he had taken him, never explained anything, and rarely spoke except to give commands.

Eat this.

Drink this.

Do not move.

Hull asked how Jacob had been taken.

Jacob’s response was fragmented, delivered in short bursts as if speaking required immense effort.

He said he had been on the trail several miles into his hike when he stopped to filter water from a creek.

He had set his pack down and knelt by the water’s edge.

That was when he felt something strike the back of his head.

He did not see it coming.

He did not hear anyone approach.

One moment he was alone and the next he was on the ground, his vision blurring, a heavy weight pressing down on his back.

He tried to fight, tried to turn over, but another blow landed and then everything went dark.

When he woke up, he was already in the cage.

His hands were tied behind his back, and there was a cloth stuffed in his mouth.

It was daytime, but he could not tell how much time had passed.

His head throbbed, and his vision was still blurry.

The man was standing outside the cage watching him.

Jacob said he tried to speak, tried to ask what was happening, but the man just stared at him with no expression, then turned and walked away into the trees.

Hull asked what happened after that.

Jacob’s voice dropped to a whisper.

He said the man came back every few days, sometimes more often, sometimes less.

He would bring water and old plastic jugs and food in small amounts, crackers, dried fruit, can beans that Jacob had to eat with his hands because he was never given utensils.

The man never unlocked the cage.

He would slide the items through the gaps in the bars, wait until Jacob had taken them, then leave without a word.

Jacob said he begged at first.

He pleaded to be let go, promised he would not tell anyone, offered money, tried reasoning, tried everything he could think of.

The man never responded.

He would stand there for a moment, expressionless, then walk away as if Jacob had not spoken at all.

After a while, Jacob stopped talking.

He realized it made no difference.

Hull asked if the man had ever harmed him physically beyond the initial attack.

Jacob hesitated then nodded slowly.

He said that on several occasions the man had opened the cage and dragged him out.

Jacob did not know why.

Sometimes the man would tie his hands and feet and leave him on the ground outside the cage for hours as if testing whether he would try to escape.

Other times the man would force him to drink water or eat even when Jacob refused.

Once when Jacob tried to resist, the man had beaten him with a thick branch, striking his legs and back until Jacob collapsed.

After that, Jacob stopped resisting.

He learned to do exactly what the man wanted when he wanted it because fighting only made things worse.

Hull asked if Jacob had any idea where the cage was located or if he had seen anything that might help identify the area.

Jacob shook his head.

He said he had tried to keep track of time by counting the days, but after a few weeks, he lost count.

The forest around him looked the same in every direction.

Tall trees, thick undergrowth, no trails, no sounds of people.

He heard animals, sometimes birds, something large moving through the brush at night, but never another human voice except the man’s.

Hull then asked the question that had been on everyone’s mind since Jacob was found.

Why do you think he kept you there? Jacob stared at the detective for a long moment.

His eyes were hollow, drained of whatever strength he had left.

I do not know, he said.

I do not think he wanted anything from me.

I think he just wanted to keep me.

The interview ended there.

The nurse stepped in and said Jacob needed to rest.

Hull thanked him, assured him that everything possible was being done to find the man responsible and left the room.

Outside in the hallway, Hull stood for a moment, processing what he had just heard.

This was not a ransom situation.

It was not about money or revenge or any clear motive that fit standard criminal behavior.

This was something else entirely.

Someone had taken Jacob Brennan off a hiking trail, held him in a cage for more than 2 months, and kept him alive for no apparent reason other than to control him.

It was predatory, methodical, and deeply disturbing.

Hull returned to the sheriff’s department and immediately organized a briefing for his team and the FBI agent assigned to the case, a woman named Special Agent Lorine Vasquez.

Vasquez had experience with abduction cases and had worked on several high-profile investigations involving isolated rural crimes.

She listened carefully as Hull recounted the interview, then reviewed the photographs taken at the scene where Jacob had been found.

Her assessment was direct.

This was not the first time the suspect had done something like this.

The level of planning, the remote location, the construction of the cage, all of it suggested experience and confidence.

Vasquez believed they were dealing with someone who had either committed similar acts before or had spent a significant amount of time preparing for this one.

She recommended that the team immediately begin searching databases for similar cases.

Any reports of missing persons in the Pacific Northwest that involved unexplained disappearances in wilderness areas, particularly those where victims were never found or were found in unusual circumstances.

Hull agreed and assigned two deputies to start pulling records.

At the same time, a forensic team was dispatched back to the site where the cage had been discovered.

Their mission was to process the scene thoroughly, collect any physical evidence that had been missed during the initial response, and document everything in detail.

The team spent two full days at the location.

They photographed the cage from every angle, took measurements, and collected samples of soil, fabric fibers, and organic material found inside and around the structure.

They also searched the surrounding area in widening circles, looking for footprints, discarded items, or anything that might indicate where the suspect had come from or where he might have gone.

One of the forensic techs discovered a faint trail leading away from the cage, barely visible under the layers of fallen leaves and moss.

It was not an official path, just a narrow line where vegetation had been disturbed over time, suggesting repeated travel by the same person.

The team marked the trail and followed it for nearly half a mile before it disappeared into a dense thicket near a dry creek bed.

They found no camp, no vehicle, no structure of any kind.

Whoever had used that trail knew how to move through the forest without leaving obvious traces.

Back at the lab, the evidence collected from the cage was analyzed.

Fingerprints were lifted from several of the metal bars, but most were too smudged or degraded to be useful.

A few partial prints were clear enough to run through the national database, but they returned no matches.

The suspect, whoever he was, had no criminal record on file.

DNA samples were taken from hair and skin cells found inside the cage.

The majority belonged to Jacob, but there were a few foreign samples that could not be immediately identified.

Those were logged and sent for further testing.

Fiber evidence collected from the interior of the cage included threads consistent with canvas work pants and cotton flannel which matched Jacob’s description of the man’s clothing.

But without a suspect to compare them to, the fibers were only useful for corroboration, not identification.

Detective Hull and Special Agent Vasquez decided to expand the investigation by interviewing anyone who had been in the Olympic National Park area during the time of Jacob’s disappearance.

They requested records from the park service showing all permit holders, volunteers, and employees who had accessed restricted or remote sections of the park between early August and mid-occtober.

The list was longer than expected, including researchers, maintenance crews, wildlife monitors, and a handful of private contractors hired for trail work and infrastructure repair.

Each name was cross-referenced against criminal databases, employment records, and known addresses.

Most were quickly cleared based on alibis or lack of access to the area where the cage had been found.

But a few individuals stood out as requiring further scrutiny.

One was a man named Gerald Kums, a 54year-old former logger who had worked seasonally for the Forest Service in the early 2000s.

Kums had been let go after a dispute with a supervisor and had not held steady employment since.

According to county records, he lived alone in a rural area east of Forks, Washington, in a cabin with no neighbors within 2 mi.

His name appeared on a list of people who had purchased a backcountry camping permit in late July, though the permit had been for a different area of the park.

Still, it placed him in the region during the relevant time period.

Hull and Vasquez decided to pay him a visit.

On the morning of October 21st, the two investigators drove out to Kum’s property.

The road leading to his cabin was unpaved and rough, winding through dense forest with no street signs or markers.

The cabin itself was small and poorly maintained with a sagging roof and walls made of weathered wood.

There was no car in the driveway, but a rusted pickup truck was parked under a tarp near a pile of cut firewood.

Hull knocked on the door.

There was no answer.

He knocked again louder this time and called out, identifying himself as law enforcement.

After a long pause, the door opened a crack.

A man peered out, his face partially obscured by a thick gray beard.

He was wearing a faded flannel shirt and canvas pants.

Hull felt a chill run down his spine.

The man matched Jacob’s description almost exactly.

Hull kept his voice calm and professional.

He explained that they were conducting interviews related to an ongoing investigation and asked if Kums would be willing to answer a few questions.

Kums hesitated, his eyes shifting between Hull and Vasquez.

Then stepped back and opened the door wider.

“Come in,” he said quietly.

The interior of the cabin was cluttered, but not filthy.

There were stacks of old newspapers, hand tools scattered on a workbench, and a wood burning stove in the corner.

The air smelled like smoke and damp wool.

Kums gestured toward a pair of wooden chairs, and sat down on a bench near the stove.

Hull and Vasquez remained standing at first, scanning the room for anything that might be relevant.

Vasquez asked Kums where he had been during the months of August and September.

Kums said he had been home most of the time, doing odd jobs around the property and occasionally going into town for supplies.

He said he had not been deep into the park since late July when he had taken a short camping trip near the Ho River.

Hull asked if he had seen or heard anything unusual during that time.

Kung shook his head.

He said he kept to himself and did not pay much attention to what other people were doing.

Vasquez then asked if he recognized the name Jacob Brennan.

Kums paused then said he had heard about the missing hiker on the news but did not know anything beyond that.

Hull decided to be more direct.

He described the cage, the condition in which Jacob had been found, and the fact that the suspect was believed to be someone familiar with the Olympic wilderness.

He watched Kums closely as he spoke, looking for any sign of recognition or discomfort.

Kums expression did not change.

He listened without interrupting, then said he had no idea who would do something like that.

Hull asked if they could take a look around the property.

Kums agreed without hesitation, which surprised both investigators.

People with something to hide usually objected or demanded a warrant, but Kums simply stood up and said they were welcome to look wherever they wanted.

Vasquez walked outside and began inspecting the truck while Hull stayed inside and examined the cabin more closely.

He checked the workbench, opened a few drawers, and looked through a pile of tools.

Nothing stood out as unusual.

No restraints, no locks, no materials that resembled the construction of the cage.

Outside, Vasquez found the truck bed empty except for a few lengths of old rope and a toolbox containing standard equipment.

She noted that the vehicle had mudc caked on the tires, but that was common for anyone living on a rural dirt road.

She photographed the license plate and took note of the make and model, but there was nothing overtly suspicious.

When they finished, Hull thanked for his cooperation and said they might follow up with additional questions later.

nodded and closed the door behind them as they left.

On the drive back, Vasquez voiced what Hull was already thinking.

Kums looked like the man Jacob described, lived in the right area, and had the skills and knowledge to operate in the back country, but there was no physical evidence linking him to the crime, and his behavior during the interview had been cooperative, almost unnervingly so.

Hull agreed.

He said they needed more before they could move forward.

They decided to run a deeper background check on Kums, request his financial records, and see if there were any purchases that might connect him to the materials used to build the cage.

They also placed him under passive surveillance, meaning his movements would be monitored without direct contact.

Meanwhile, the database search that Vasquez had requested began yielding results.

Over the next several days, investigators compiled a list of unsolved missing person cases in Washington, Oregon, and Northern California that shared certain characteristics with Jacob’s abduction.

There were 11 cases in total, all involving individuals who had disappeared while hiking or camping in remote wilderness areas.

Most had never been found.

Two had been found deceased under circumstances that were never fully explained.

One case in particular caught Hull’s attention.

In the summer of 2015, a 28-year-old man named Andre Pitkin had vanished while hiking alone in the Gford Pincho National Forest about 120 mi south of Olympic National Park.

His car had been found at a trail head, his gear still inside, and no trace of him was ever discovered despite an extensive search.

The case had gone cold within weeks.

Hull contacted the lead investigator on that case, a retired ranger named Tom Fairley, and asked if there had been any unusual details.

Fairley said there had been one thing that always bothered him.

A few weeks after Pikkin disappeared, a hunter had reported seeing what he described as a makeshift cage or animal trap in a remote section of the forest several miles from where Pitkin’s car had been found.

The hunter had not thought much of it at the time and had not reported the location with enough detail for it to be investigated.

By the time anyone followed up, the area had been searched and nothing was found.

Fairley admitted he had always wondered if the two things were connected, but without evidence, it remained nothing more than a hunch.

Hull asked if Fairley had any suspects at the time.

Fairley said there had been one person of interest, a man who lived near the forest and had a history of poaching and trespassing, but he had been cleared after providing an alibi.

Fairley could not remember the man’s name off the top of his head, but said he would dig through his old files and get back to Hull.

2 days later, Fairley called back.

The man’s name was Gerald Hull felt his chest tighten.

He asked fairly to send over everything he had on from the 2015 investigation.

Within hours, Hull was reviewing a thin file that included interview notes, a description of Kum’s property, and a few photographs.

The details matched what Hull and Vasquez had seen during their visit.

Kums had been questioned after a tip from a local resident who said Kums had been seen in the area around the time of Pitkin’s disappearance.

But Kums had claimed he was working a job in another county and a contractor had vouched for him.

The alibi had been shaky, but without physical evidence, the investigation had moved on.

Now 3 years later, Kum’s name had surfaced again in a nearly identical case.

Hull brought the information to Vasquez and they agreed it was time to take a harder look at Gerald Kums.

They requested a warrant to search his property more thoroughly, this time with a full forensic team and cadaavver dogs.

The warrant was approved based on the connection to the previous case and the matching physical description provided by Jacob.

On the morning of October 28th, a convoy of law enforcement vehicles made its way back to Kum’s cabin.

This time, there would be no polite conversation.

This was a full-scale search and everyone involved knew what they were looking for.

Evidence of a predator.

When the team arrived at the cabin, Kums was not there.

His truck was gone and the door was locked.

Hull authorized entry and deputies forced the door open.

Inside the scene was much as it had been during the first visit, but this time the investigators took their time.

They dismantled the workbench, searched under the floorboards, opened every drawer and cabinet, and examined every tool.

In a back room that had been used for storage, they found several lengths of metal rod, a welding torch, and a set of heavyduty work gloves.

The metal rods were similar in diameter and composition to the bars used in the cage where Jacob had been held.

A forensic tech bagged them immediately for comparison.

In a wooden crate near the stove, another investigator found a collection of old maps, many of them marked with handwritten notes.

Some of the maps showed trails in Olympic National Park.

Others depicted areas in Gford Pincho, Mount Baker Snowqualami, and even parts of the Oregon Cascades.

Several locations were circled in red ink.

And next to some of the circles were dates.

One of the dates was August 9th, 2018, the day before Jacob Brennan disappeared.

The location circled on that map was less than a mile from the Enchanted Valley trail head.

The maps were photographed and logged as evidence.

Hull studied them carefully, noting that many of the marked locations corresponded with areas where hikers had gone missing over the past several years.

It was not definitive proof, but it established a pattern.

had been documenting remote locations, possibly scouting them, possibly using them for purposes that were now becoming disturbingly clear.

Outside, the cadaavver dogs were brought in to sweep the property.

They were trained to detect the scent of human remains, even if those remains had been moved or buried months or years earlier.

The dogs worked in a grid pattern, moving slowly across the clearing around the cabin, then into the tree line beyond.

After nearly an hour, one of the dogs alerted near a cluster of large stones at the edge of the property about 70 yard from the cabin.

The handlers signaled to the forensic team, and investigators began carefully removing the stones and digging into the soil beneath.

What they found was not a body, but it was almost as damning.

Buried in a shallow pit were several personal items, a wallet, a cell phone in a cracked case, a wristwatch, and a small zippered pouch.

The wallet contained an ID card with the name Andre Pitkin.

The cell phone, though damaged and non-functional, had a sticker on the back with initials that matched Pitkins.

The pouch held a few credit cards and a folded photo of a young woman.

Hull stood over the excavation site, his jaw tight.

This was no longer just about Jacob Brennan.

This was about multiple victims, possibly more than they even knew.

Kums had kept trophies, items taken from people who had likely never made it home.

The discovery was immediately relayed to special agent Vasquez, who was coordinating with federal authorities to issue a warrant for Kung’s arrest.

With the physical evidence now tying him to at least two cases, and with Jacob’s testimony describing a man who matched in appearance and behavior, there was enough to charge him with kidnapping, unlawful imprisonment, and suspicion of murder.

The problem was that was gone.

His truck had not been seen since the morning of the search, and there had been no activity on any known bank accounts or credit cards.

He had either fled or gone into hiding, and given his knowledge of the wilderness, he could be anywhere.

A regional alert was issued and Kung’s photograph was distributed to law enforcement agencies across Washington, Oregon, and Idaho.

His truck’s make, model, and license plate were flagged in every database.

The FBI classified him as a fugitive and added him to their wanted list.

Roadblocks were set up on highways leading out of the Olympic Peninsula, and rangers were instructed to report any sightings of individuals matching his description in backcountry areas.

For the next several days, there was no sign of him.

Then, on the evening of November 2nd, a gas station attendant in the small town of Quinnalt, about 40 mi south of Forks, called the sheriff’s department to report a man who had paid for fuel and cash and whose appearance matched the photo that had been circulated.

The man had been driving an older pickup truck with mud on the plates, making them difficult to read, but the attendant was fairly certain it was the same vehicle described in the alert.

Deputies arrived at the gas station within 20 minutes, but the truck was already gone.

The attendants said the man had filled up, bought a few items inside, and left heading east on Highway 101.

Surveillance footage from the gas station was reviewed, and though the image quality was poor, the figure captured on camera was consistent with Gerald Kums.

He was wearing a dark jacket and a baseball cap pulled low over his face, but the build and the beard were unmistakable.

A pursuit was organized immediately.

State patrol units were dispatched to intercept the truck on Highway 101 and a helicopter was requested to provide aerial support.

The search focused on the area between Quinnalt and the town of Humptulips, a stretch of rural road with few turnoffs and limited places to hide.

Just after midnight, a patrol officer spotted a truck matching the description parked on a gravel access road near the Humptilips River.

The officer approached cautiously, calling for backup before making contact.

When additional units arrived, they surrounded the vehicle and ordered the occupant to step out with his hands visible.

There was no response.

The truck’s engine was off and the driver’s side door was slightly a jar.

Officers moved in with weapons drawn and found the truck empty.

A search of the immediate area began using flashlights and thermal imaging equipment.

The riverbank was steep and thick with brush, making visibility difficult.

After nearly an hour of searching, one of the officers spotted a figure moving through the trees about 100 yards downstream.

He shouted a command to stop and identify, but the figure continued moving.

A foot chase ensued.

The suspect ran along the edge of the river, stumbling over rocks and fallen branches, but maintaining enough distance to stay ahead of the officers.

The terrain was treacherous and the darkness made it nearly impossible to move quickly without risk of injury.

One officer slipped and fell, twisting his ankle, but the others pressed on.

The chase continued for nearly a quarter of a mile before the suspect made a critical mistake.

He tried to cross a shallow section of the river, misjudged the depth, and lost his footing.

He went down hard, hitting his head on a submerged rock.

By the time the officers reached him, he was faced down in the water, unconscious.

They pulled him out immediately and checked for a pulse.

He was alive but unresponsive.

Paramedics were called and the man was transported to Grace Harbor Community Hospital in Aberdine.

His identity was confirmed at the scene through a driver’s license found in his jacket pocket.

It was Gerald Kums.

He remained unconscious for nearly 18 hours.

When he finally woke, he was handcuffed to the hospital bed and under guard by two deputies.

A doctor examined him and determined that he had suffered a concussion and some bruising, but no life-threatening injuries.

He was cleared for questioning later that day.

Detective Hull and Special Agent Vasquez arrived at the hospital that afternoon.

Kums was awake but groggy, his eyes half closed and his speech slurred.

The doctor advised that any interview should be brief, but Hull insisted they needed to proceed.

Kums was read his rights and asked if he understood them.

He nodded.

Vasquez asked him directly if he was responsible for the abduction of Jacob Brennan.

Kums did not answer.

Hull asked if he knew Andre Pitkin.

Again, no response.

Vasquez leaned closer and said they had found Pitkin’s belongings buried on his property.

She said they had maps with marked locations and dates.

She said they had testimony from a survivor.

She told him that running was over and the only thing left was the truth.

Kum stared at the ceiling for a long time.

Then in a voice barely above a whisper, he said, “I did not mean for it to go this far.

” Hull asked him to explain what he meant.

Kums closed his eyes.

He said he had always felt more comfortable alone, away from people, away from noise and expectations.

He said the forest was the only place he felt in control.

He said that over the years he had started to resent the people who came into his space, the hikers, the campers, the ones who treated the wilderness like a playground.

He said he wanted to teach them what it really meant to be alone.

Hull asked how many people he had taken.

Kums did not answer directly, but he did not deny it either.

He said some of them had not survived, that he had not planned for that, but it had happened.

He said he had kept Jacob alive because Jacob had been different, quieter, less resistant.

He said he had intended to let him go eventually, but he had not decided when.

Vasquez asked where the others were.

Kum said he did not remember all of them.

He said some had been left in the forest, that nature had taken care of the rest.

He said he had moved around over the years, never staying in one place long enough to draw attention.

Hull asked if he felt any remorse.

Kums opened his eyes and looked directly at him.

He said he did not expect anyone to understand.

The interview was terminated shortly after.

Kums was formally charged with kidnapping, unlawful imprisonment, and first-degree murder.

Additional charges were expected as investigators continued to match evidence from his property with unsolved cases.

In the days that followed, search teams were deployed to several of the locations marked on Kung’s maps.

In two separate areas, they discovered remains that were later identified through dental records as belonging to missing persons from previous years.

One was Andre Pitkin.

The other was a 35-year-old woman named Clare Hoffner who had disappeared while hiking in the Cascades in 2016.

Her case had been closed as a presumed accidental death, but the discovery of her remains in a concealed grave suggested otherwise.

Jacob Brennan was informed of Kum’s arrest while still recovering in the hospital.

His brother was with him when Detective Hull delivered the news.

Jacob did not say much.

He nodded slowly, his face blank, and then turned toward the window.

His brother later said that Jacob had not shown much emotion about anything since being found, that he seemed distant, like part of him was still locked in that cage.

If you’ve ever felt uneasy in the wilderness or wondered what dangers might lurk beyond the trail, make sure you hit that subscribe button and turn on notifications.

Cases like this don’t just disappear, and neither should your awareness.

We cover the stories that need to be told, the ones that remind us how fragile safety can be.

Subscribe now because the truth is always worth following.

Gerald Kums was transferred to the Jefferson County Jail after being medically cleared from the hospital.

He was held without bail, classified as a flight risk and a danger to the public.

His arraignment took place in early November before a judge who reviewed the charges and the evidence presented by the prosecution.

Kums entered a plea of not guilty despite his partial confession during the hospital interview.

His courtappointed attorney argued that the statements made while Kums was concussed and medicated should be considered inadmissible, but the judge allowed them to remain part of the record pending further legal review.

The case attracted significant media attention.

News outlets across the Pacific Northwest covered the story extensively, focusing on the disturbing details of Jacob’s captivity and the possibility that Kums had been responsible for multiple disappearances over several years.

Families of missing hikers began reaching out to authorities, asking whether their loved ones might be connected to the case.

The FBI coordinated with local agencies to review dozens of cold cases, cross-referencing locations, timelines, and victim profiles against the evidence gathered from Kung’s property and the maps found in his cabin.

As the investigation deepened, more troubling details emerged.

Forensic analysis of the metal rods found in Kum’s storage room confirmed that they were consistent with the materials used to construct the cage where Jacob had been held.

Soil samples taken from Kum’s truck matched soil composition found at the sight of the cage, placing his vehicle at or near the location.

Additionally, fiber evidence collected from Jacob’s clothing was compared to fabric samples taken from Kum’s cabin, including work shirts and canvas tarps.

Several fibers were a match, further linking Kums to the crime.

The most damning evidence, however, came from a digital forensics team that managed to recover data from Andre Pitkin’s damaged cell phone.

Although the phone had been buried for years and was no longer functional, technicians were able to extract fragments of stored information from its internal memory.

Among the recovered data were several photos taken on the day Pitkin disappeared.

The images showed scenic views of the forest, a creek, and in the background of one photo partially obscured by trees, the figure of a man wearing a flannel shirt and a hat.

The image was grainy and distant, but forensic experts enhanced it and compared it to known photographs of Gerald Kums.

The resemblance was strong enough to be presented as corroborative evidence.

It suggested that Pitkin had unknowingly photographed his abductor shortly before he was taken.

In December of 2018, the prosecutor’s office announced that they would be seeking multiple counts of first-degree murder, kidnapping, and aggravated assault.

The case was expected to go to trial in the spring of the following year.

Kums remained in custody, largely silent, and uncooperative with investigators.

His attorney attempted to negotiate a plea deal in exchange for information about other potential victims, but the prosecution refused, insisting on a full trial and maximum sentencing.

Meanwhile, Jacob Brennan faced his own long and difficult road to recovery.

After being released from the hospital, he moved in with his brother in Seattle.

He was enrolled in a trauma therapy program and met regularly with a psychologist who specialized in post-traumatic stress and captivity trauma.

Progress was slow.

Jacob struggled with severe anxiety, insomnia, and flashbacks.

He could not be in enclosed spaces without feeling panic.

Loud noises startled him.

He avoided going outside for weeks at a time.

His brother described him as a shadow of the person he had been before, someone who had lost not just months of his life, but a part of his identity.

In a brief statement given to the press through his attorney, Jacob thanked the investigators, the medical staff, and everyone who had supported him and his family.

He said he was trying to move forward, but that the experience had changed him in ways he was still trying to understand.

He asked for privacy and said he hoped that by telling his story, others might be more cautious and that people like Kums might be stopped before they could hurt anyone else.

The trial of Gerald Kums began in April of 2019.

It was held in the Jefferson County Superior Court and lasted just over 3 weeks.

The prosecution presented a detailed and methodical case built on physical evidence, witness testimony, and Kum’s own words.

Detective Hull and Special Agent Vasquez both testified, walking the jury through the timeline of the investigation, the discovery of the cage, and the subsequent identification and arrest of the defendant.

Jacob Brennan took the stand on the fourth day of the trial.

His testimony was emotional and at times difficult to follow, but it was clear and consistent.

He described being struck from behind while filtering water, waking up in the cage, and enduring more than 2 months of isolation and fear.

He identified Kums as the man who had held him, fed him sporadically, and subjected him to physical violence.

Defense attorneys tried to cast doubt on Jacob’s memory, suggesting that trauma and time had distorted his recollection, but Jacob remained firm.

He said he would never forget the man’s face, his voice, or the way he looked at him as if he were nothing more than an object.

Forensic experts testified about the physical evidence, the metal rods, the soil, the fibers, and the items recovered from Kum’s property.

Maps were entered into evidence and displayed for the jury, showing the marked locations that matched known disappearances.

The photographs recovered from Andre Pitkin’s phone were presented along with expert testimony regarding the figure visible in the background.

The defense offered little in the way of counter evidence.

Kums did not take the stand.

His attorney argued that the case was circumstantial, that the evidence could be interpreted in multiple ways, and that the prosecution had not definitively proved intent or malice.

But the weight of the evidence was overwhelming and the jury saw through the attempts to create reasonable doubt.

After two days of deliberation, the jury returned a verdict.

Guilty on all counts.

Kums was convicted of two counts of first-degree murder, one count of kidnapping, one count of unlawful imprisonment, and multiple counts of assault.

The courtroom was silent as the verdict was read.

Jacob was present sitting in the gallery beside his brother.

He did not react visibly, but his brother later said that Jacob had squeezed his hand so tightly it left marks.

Sentencing took place 3 weeks later.

The families of Andre Pitkin and Clare Hoffner were given the opportunity to address the court.

Pitkin’s sister spoke about the years of not knowing, of hoping he would come home, and of the pain that came with finally learning the truth.

Hoffner’s mother, elderly and frail, read a short statement through tears, saying that her daughter had been kind and adventurous and did not deserve to be taken from the world in such a cruel way.

The judge, after hearing all statements and reviewing the pre-sentencing report, sentenced Gerald Kums to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

In his remarks, the judge described Kums actions as calculated, sadistic, and a profound violation of human dignity.

He said that Kums had prayed on people in moments of peace and vulnerability, turning places of natural beauty into scenes of horror.

He said there was no place in society for someone who had demonstrated such disregard for life.

Kums was led out of the courtroom in shackles.

He did not speak.

He did not look at the families.

He simply stared ahead as he was escorted back into custody.

In the months following the trial, additional searches were conducted in areas marked on Kung’s maps.

Two more sets of remains were recovered, though they were too degraded for immediate identification.

DNA testing was ongoing, and investigators believed that at least one of the individuals was linked to a missing person case from 2014.

The true number of Kum’s victims may never be fully known.

He refused to cooperate with authorities after his conviction and provided no additional information about other potential sites or individuals.

Some cases remain open and some families still wait for answers.

Jacob Brennan slowly began to rebuild his life.

He did not return to his job in software development.

Instead, he took a part-time position working remotely, something that allowed him to stay home and avoid the pressures of an office environment.

He continued therapy and joined a support group for survivors of violent crime.

He started writing in a journal, a practice his therapist encouraged as a way to process what had happened to him.

In early 2020, Jacob gave a more detailed interview to a journalist working on a long- form article about the case.

In that interview, he spoke about what it felt like to be forgotten, to be treated not as a person, but as a possession.

He said the worst part was not the hunger or the cold or even the fear of dying.

It was the isolation, the feeling that the world had moved on without him and that no one was coming.

He said that even after being rescued, that feeling had not entirely gone away.

He also spoke about the moment he was found.

He said he did not remember much of it clearly, only that there were voices, people in uniforms, and someone wrapping a blanket around him.

He said he had not believed it was real at first.

He thought it might be another trick, another test.

It was not until he was in the hospital surrounded by his brother and doctors that he began to accept that he was actually safe.

Jacob’s story became a reference point in discussions about safety in national parks and the vulnerability of solo hikers.

Several organizations used his case to promote awareness about the importance of checking in with others, carrying communication devices, and staying on marked trails.

His experience also prompted some changes in how missing person cases are handled in remote wilderness areas with increased emphasis on rapid response and inter agency coordination.

For Jacob, the attention was both validating and exhausting.

He appreciated that people cared, but he also struggled with being defined by what had happened to him.

He said in one interview that he did not want to be known only as the man who was kept in a cage.

He wanted to be seen as someone who survived, who was still here, still trying.

As of the time this story was documented, Jacob Brennan was living quietly in Washington State.

He had reconnected with a few old friends and had begun taking short walks in parks near his home, though he avoided heavily forested areas.

He said he hoped that one day he would be able to hike again, but he was not ready yet.

Maybe he never would be and that he said was okay.

Gerald Kums remains incarcerated in a maximum security facility.

He has been involved in no incidents and keeps mostly to himself.

He receives no visitors and has declined all interview requests.

Psychologists who evaluated him after his conviction described him as detached, unemotional, and unwilling to discuss his motives in any meaningful way.

He is considered a high-risk individual with no prospect of release.

The cage where Jacob was found was dismantled and taken into evidence.

It remains in a secure storage facility, a grim piece of physical proof in a case that shocked a community and revealed the dark capabilities of a man who chose to use his knowledge of the wilderness not to appreciate it, but to control and harm others within it.

The forest where Jacob was held has returned to silence.

Hikers still walk the trails.

Researchers still study the ecosystem.

But for those who know the story, the woods carry a different weight now.

They are a reminder that beauty and danger can exist in the same place, that isolation can be both peaceful and terrifying, and that sometimes the most dangerous predator is not an animal, but a human being who has lost all connection to empathy.

If this story affected you, if it made you think twice about the world around you or the importance of staying aware, then do not let it end here.

Hit that like button, share this video with someone who needs to hear it, and make sure you are subscribed so you never miss the stories that matter.

The truth does not always come easy, but it is always worth pursuing.

Stay safe out there.

Jacob Brennan’s name is now part of a growing list of people who survive the unimaginable.

His story serves as both a warning and a testament to resilience.

It reminds us that even in the darkest moments when hope seems gone and the world feels indifferent, survival is possible.

It also reminds us that evil does not always announce itself.

Sometimes it hides in plain sight in a quiet man living alone in the woods.

In someone who knows the trails better than anyone else.

In a person who has learned to move through the world without being seen.

And it reminds us above all that we must never stop looking for those who go missing.

Because sometimes against all odds they are still out there, still alive, still waiting to be

News

Ilhan Omar ‘PLANS TO FLEE’…. as FBI Questions $30 MILLION NET WORTH

So, while Bavino is cracking down in Minnesota, House Republicans turning the heat up on Ilhan Omar. They want to…

FBI & ICE Raid Walz & Mayor’s Properties In Minnesota LINKED To Somali Fentanyl Network

IC and the FBI move on Minnesota, touching the offices of Governor Tim Walls and the state’s biggest mayors as…

FBI RAIDS Massive LA Taxi Empire – You Won’t Believe What They Found Inside!

On a Tuesday morning, the dispatch radios in hundreds of Los Angeles taxi cabs suddenly stopped playing route assignments. Instead,…

Brandon Frugal Finally Revealed What Forced Production to Halt in Season 7 of Skinwalker Ranch….

The Secret of Skinwalker Ranch became History Channel’s biggest hit. Six successful seasons documenting the unknown with real science and…

1 MINUTE AGO: What FBI Found In Hulk Hogan’s Mansion Will Leave You Shocked….

The FBI didn’t plan to walk into a media firestorm, but the moment agents stepped into Hulk Hogan’s Clearwater mansion,…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage… It started like any other evening…

End of content

No more pages to load