Native Activist Vanished in 1987 — 18 Years Later Workers Found This Shackled in a Tunnel….

South Dakota, 1987.

The winds across the plains carried the songs of generations, the heartbeat of a land that never forgot.

And yet in that summer, one voice was silenced.

A voice that had shouted against corruption, against broken treaties, against the eraser of native lives.

His name was Michael Redbird, 34 years old, a Lakota activist with fire in his chest and scars on his body that spoke of a life that was never easy.

Michael had been born in hardship, the second son in a family of six children, raised by parents who worked two jobs just to keep food on the table.

His father, Henry, was a Korean War veteran who came back home with a limp and a quiet anger, while his mother, Eliza, stitched quilts at night to make ends meet.

Michael’s childhood was not one of privilege, but of survival, broken trailers, broken schools, broken promises from governments that had long forgotten the Lakota people.

But from those broken places, Michael carried a spirit of defiance.

He was a boy who asked questions, who challenged teachers when they tried to skip over the chapters about native massacres.

He was the teenager who organized protests outside the courthouse when his cousin was jailed without cause.

And by the time he was in his 20s, Michael had become something more, a symbol of resistance.

Yet symbols often attract enemies.

In the 1980s, corporate hands reached deep into native land.

Mining companies, with the blessing of county commissioners and state sheriffs, dug deeper and deeper into sacred ground.

The uranium mines poisoned rivers.

The logging stripped away forests where families had hunted for centuries.

And it was Michael Redbird who stood in front of the bulldozers, who shouted into megaphones, who gave speeches that rattled courthouse walls.

He was fearless, but he was also vulnerable.

Michael walked with a slight limp, the result of a childhood accident when his leg was crushed beneath farm machinery.

It never healed properly, and even as an adult, the limp was unmistakable.

People who knew him said you could always recognize his walk from a distance.

That limp would later become the only way his family could recognize him in death.

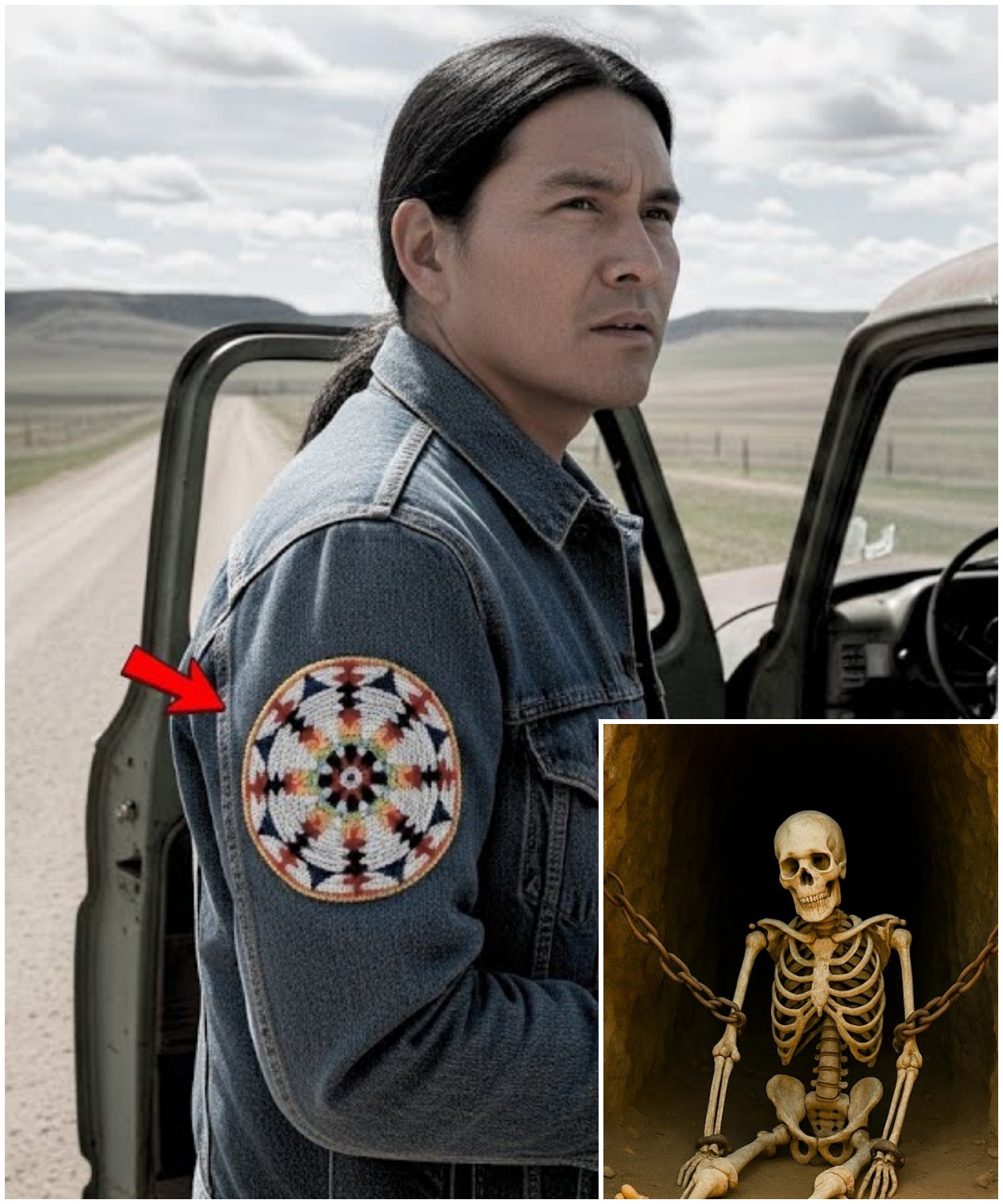

On the evening of July 9th, 1987, Michael left his small house on the Pine Ridge Reservation.

He wore a denim jacket with a Lakota beadwork patch stitched by his younger sister.

He carried his leather notebook filled with names, dates, and evidence.

Notes about payments exchanged between mining executives and the county sheriff’s office.

His plan was to drive into Rapid City for a meeting with fellow activists.

He never arrived.

Witnesses saw him on the highway, his rusted green pickup rattling northward.

Behind him, a black van with tinted windows followed.

Some said they recognized the vehicle, that it belonged to the sheriff’s cousin.

Others whispered that federal agents had been in the area that night.

But when the official police report was filed, none of these details appeared.

By the next morning, Michael was gone.

His bed remained unmade, his boots still by the door, his truck, his jacket, his body vanished into nothing.

The sheriff’s office wrote a single page report.

Subject likely left the area voluntarily.

To them, it was case closed, but for his family, it was the beginning of a nightmare.

His mother wept so loudly the neighbors heard her through the thin walls.

His younger sister Mariah refused to believe the words voluntary disappearance.

His father Henry stood silent, fists clenched, his limp more pronounced than ever.

The family began searching themselves, driving dirt roads, walking ravines, asking questions no one wanted to answer.

And as the weeks turned into months and the months into years, Michael’s absence became more than a wound.

It became a mystery wrapped in whispers.

People said he had been taken.

Some claimed they saw him dragged from his truck.

Others swore they heard chains clanking in an old railway tunnel near the mines.

But whenever the family pushed for answers, doors slammed shut.

18 years would pass before the truth emerged.

But in 1987, all the Redbird family had was silence, suspicion, and the aching knowledge that Michael had been swallowed whole by a system that had wanted him gone.

This was not just a disappearance.

It was an eraser.

And somewhere beneath the soil of South Dakota, his story was shackled, waiting to be unearthed.

The weeks after Michael’s disappearance became a blur of unanswered phone calls, unopened case files, and sleepless nights.

His family tried everything, knocking on doors, speaking to reporters, pleading with the sheriff’s office.

But again and again, the same words came back.

There’s nothing we can do.

Mariah, his younger sister, was only 22 at the time, a school teacher with a soft voice and a quiet strength.

She remembered placing Michael’s photo on the bulletin board at the local grocery store, her hands trembling as she pinned the flyer.

“Missing,” it read in bold letters.

His face, strong and serious, stared back at her from the paper.

But by the next morning, the flyer was gone.

Someone had torn it down.

It wasn’t just indifference.

It was hostility.

The Redbird family began to notice strange cars idling near their trailer late at night.

Men they didn’t recognize lingered outside the community center during prayer gatherings.

Once a rock shattered their window with a note tied to it.

Stop asking questions.

Henry, Michael’s father, had been a soldier once.

He had faced artillery fire in Korea, but nothing compared to the helpless rage he felt now.

He hobbled through town with his cane, demanding answers from the sheriff himself.

Sheriff Lawson was a broad man with a thick mustache and a voice like gravel.

He leaned back in his chair, boots on the desk, and said, “Your boy was trouble, Henry.

” always stirring people up.

Maybe he just ran off before he got himself hurt.

You should let it go.

Henry never forgot those words.

Nor did Mariah.

The truth was, Michael hadn’t just been a protester.

He had been collecting evidence, ledger sheets, photographs, signed affidavit from workers.

He had spoken of a deal between Lawson’s deputies and the Black Hills Mining Company.

Uranium shipments were being moved illegally, waste dumped into streams where children played, and Michael had all of it written down in his notebook.

That notebook vanished with him.

Rumors spread like wildfire across Pine Ridge.

Some said Michael had been taken by men in uniforms, driven into the hills, chained inside one of the abandoned railway tunnels that crisscrossed the mining land.

Others believed he had been buried under concrete when the new access road was poured.

And yet, despite the whispers, no one dared speak openly.

Fear gripped the community tighter than chains.

Eliza, his mother, began keeping vigil at the kitchen table.

Every night, she lit a candle and placed it beside his empty chair.

“He will come back,” she whispered, as if the words themselves could bring him home.

But days bled into months, and the only sound in the house was the wind rattling through broken windows.

By the early 1990s, the Redbirds were fractured by grief.

Henry’s health declined.

The limp that had followed him since the war worsened until he could barely walk.

Mariah took over his duties, driving him to VA appointments while still teaching during the day.

Their younger brother, David, turned to drinking, disappearing for days on end.

It seemed as if Michael’s absence had poisoned them all, one by one.

And yet, through it all, the memory of Michael remained alive in the community.

His speeches were remembered.

His courage was whispered about in kitchens and on porches.

But the official story, written in black ink on county paper, said otherwise.

Case closed.

Subject missing.

Presumed runaway.

The injustice was almost unbearable.

A man who had fought for his people, who had risked everything to expose corruption, was painted as a coward who fled.

His enemies not only silenced his voice, but rewrote his story.

Still, one detail noded at the Redbirds, the black van.

Multiple witnesses had mentioned it.

They described its tinted windows the way it followed too close on the night of July 9th.

Yet when Mariah tried to have their statements recorded, the sheriff’s office refused.

“Unreliable witnesses,” Lawson said.

“Unreliable, perhaps because their words pointed directly at him.

” By 1995, 8 years had passed.

The Redbirds had filed petitions, spoken to reporters, even contacted federal investigators, but every door closed before it opened.

Some officials simply shrugged.

Others told them bluntly, “There are bigger problems than one missing man.

” But for the family, there was no bigger problem.

Each year on Michael’s birthday, they gathered in silence.

They set a plate at the table, placed his beaded necklace across the chair.

Eliza’s hair had gone white by then, but she still stitched quilts late into the night, as though keeping her hands busy would keep the grief from swallowing her whole.

And all the while, beneath the hills and the poisoned rivers, the truth waited, buried, shackled, silenced.

It would take nearly two decades for that truth to claw its way back into the light.

But when it did, it revealed something far darker than the family had ever imagined.

By the summer of 1996, 9 years had passed since Michael’s disappearance.

To the outside world, time had moved on.

New elections, new construction projects, new promises.

But inside the Redbird household, time had frozen.

on July 9th, 1987.

The family still lived in the same worn trailer.

Its siding rusted, its windows patched with plastic sheeting to keep out the cold.

Eliza still kept the candle burning at night, though by now the wax had built into uneven towers of hardened drips, a shrine of sorrow.

Mariah had grown harder in those years.

No longer the gentle school teacher who believed in fairness, she carried herself with a quiet fire.

She had written letters, hundreds of them, to journalists, senators, even the governor.

Most went unanswered.

The few that did were polite rejections.

Unfortunately, we cannot allocate resources to reopen this case at this time.

Still, she persisted.

She remembered her brother’s words spoken only days before he vanished.

If I disappear, promise me you’ll tell them.

Don’t let them bury the truth.

But the truth was heavy and it came with consequences.

One afternoon in 1996, while driving home from school, Mariah noticed a black van in her rearview mirror.

It followed her for several miles, always two cars back.

When she turned off the highway onto the dirt road leading home, the van stopped at the intersection, idling for a long moment before pulling away.

That night, she found another rock thrown through their window.

This time, the note read, “Stop digging or you’ll end up like him.

” She didn’t show it to her mother.

She quietly picked up the glass, swept the floor, and carried the note out to the fire pit.

But she told her younger brother, David.

By then, he was drowning in alcohol.

A hollowedout shell of the boy who had once looked up to Michael.

Yet, even in his haze, the note shook him.

For a brief moment, the bottle left his hand.

“Lawson won’t let this go,” he muttered.

“He never did.

” Sheriff Lawson had been reelected twice since Michael vanished.

He was untouchable, shielded by his connections to mining executives and county commissioners.

New roads were built, new mines opened, jobs were promised, though few of them ever reached native families.

And every time protesters gathered, deputies were there to push them back.

Deputies who reported directly to Lawson.

In those same years, whispers continued to drift across the reservation.

A former mining worker drunk in a bar once told David, “Your brother, they chained him.

” Down in the old tunnel by Red Creek, he screamed for days.

But when David returned sober the next day, the man denied ever saying it.

A week later, he left town for good.

Stories like that haunted the family.

They didn’t know what to believe.

Was Michael buried beneath concrete, shackled underground, or was he still alive somewhere, held against his will? Each possibility was torture in its own way.

Eliza prayed every morning, her frail hands gripping rosary beads so tightly they left impressions in her skin.

She told neighbors she dreamed of Michael calling her from a dark place.

“He says he’s cold,” she whispered.

He says the walls are closing in.

Mariah though grew colder with every year.

She began keeping her own notebook, documenting threats, recording dates, writing down every rumor.

If they killed him, she told herself, “Then I’ll make sure the world knows why.

” By 1999, 12 years had passed.

Henry Redbird died that winter, his limp finally giving way to lungs filled with pneumonia.

At the funeral, Mariah placed Michael’s empty chair beside the coffin.

“One son in the ground,” she whispered, and one still missing.

“After Henry’s death, the family fractured further.

David disappeared into his drinking completely.

Eliza’s mind began to wander, sometimes forgetting what day it was.

Only Mariah remained focused, still writing letters, still knocking on doors, still demanding answers.

And yet, every time she stood in front of an official, she saw the same look.

The look of someone who knew more than they would say.

The vanishing of Michael Redbird had become more than a mystery.

It was an open wound for his family and a shadow over the community, a symbol of how far those in power would go to silence a native voice.

But silence cannot last forever.

By 2005, 18 years after Michael’s disappearance, a construction project would begin near the very mines he had once fought to shut down.

And in the process of carving a new access road, workers would stumble upon something buried deep in the hills.

Something that confirmed every nightmare the Redbirds had ever whispered about.

By the spring of 2005, the Black Hills were once again humming with machines.

The mining company, now rebranded under a new name, announced plans to expand their operations.

Bulldozers carved into the slopes, trucks rumbled along dirt roads, and surveyors mapped out new tunnels for extraction.

It was the same land Michael Redbird had once sworn to protect, the same hills where he had rallied his people, the same rivers he had fought to keep clean.

Mariah, now 40 years old, had grown used to the sound of promises and machines.

She no longer believed the speeches of county commissioners, nor the words printed in glossy brochures about progress.

To her, progress meant erasure of trees, of rivers, of voices like Michaels.

She still lived in the family trailer, her mother growing frailer by the day.

Eliza’s memory slipped in and out like a fading candle.

Some mornings she asked, “When will Michael be home?” as if the last 18 years had been only days.

Mariah didn’t correct her.

She simply held her hand and said, “Soon.

” But soon came in a way none of them expected.

On an April morning, workers began drilling near Red Creek, not far from where the old railway tunnels had once been sealed shut decades earlier.

The men joked and smoked cigarettes as the machines growled against rock.

But by midafter afternoon, one of the drill heads broke through into a hollow space.

The sound changed, an echo, a resonance that didn’t belong to solid earth.

They had hit a void.

The foreman ordered the crew to stop.

A small opening was widened with picks and crowbars until the stale air of a forgotten tunnel hissed out into the sunlight.

Dust billowed, carrying the smell of rust and damp stone.

Some of the younger workers laughed nervously, daring each other to look inside.

When the first flashlight beam cut into the darkness, the laughter stopped.

There, only a few feet inside the tunnel were bones.

Human bones.

At first, it looked like a collapsed mannequin, the limbs bent at odd angles.

But as the dust cleared, the shape became undeniable.

A human skeleton slumped against the wall, wrists still bound in rusted shackles.

The chains were bolted directly into the tunnel stone.

The workers froze.

One dropped his cigarette.

Another vomited against the wall.

Nobody spoke.

For a long moment, the only sound was the chain creaking as if stirred by a phantom wind.

Word spread quickly.

Within an hour, sheriff’s deputies arrived.

New faces, though all of them wore the same uniform Michael had once railed against.

They pushed the workers back, sealed off the area, and muttered into radios.

Some said the deputies looked pale when they saw the bones, as if they already knew what had been hidden there.

Mariah heard about it the next day, not from the sheriff’s office, but from a cousin who worked on the crew.

He came to her door, his voice shaking.

There’s a body in the tunnel, Mariah.

Shackled.

Been there a long time.

Her hands trembled as she gripped the doorframe.

Where? Red Creek.

Near the mine.

They’re not telling anyone.

They don’t want this getting out.

For Mariah, the world seemed to tilt.

For 18 years, she had imagined every possibility.

Her brother buried, drowned, vanished into thin air.

but shackled in a tunnel.

It was a nightmare made real.

That night, she sat beside her mother’s bed.

Eliza was half asleep, murmuring in a dream.

“He says he’s cold,” she whispered again, the same words she had repeated for years.

Mariah pressed her forehead against her mother’s frail hand and felt tears she thought she no longer had.

The next morning, she drove straight to Red Creek.

The road was blocked by deputies.

Their cruisers parked across the dirt path.

She demanded answers, demanded to be let through.

One deputy told her, “It’s just an old vagrant.

Nothing to do with you.

” But she knew the limp, the chains, the whispers of witnesses who had spoken of tunnels.

Mariah’s heart pounded as she stared past the barricade toward the hills that had swallowed her brother.

She had waited 18 years for this moment, and now the truth was clawing its way to the surface.

And yet, the sheriff’s office was already working to bury it again.

The barricades held for 2 days.

Deputies came and went, their vehicles rumbling up and down the dirt road, while men in plain clothes slipped inside the tunnel with boxes of equipment.

Workers who had first uncovered the bones were told to keep silent.

Company business, the foreman warned them, but whispers like smoke could not be contained.

Mariah waited outside the barrier every morning, sitting in her car with a thermos of coffee, staring at the hills.

Deputies threatened her with arrest.

She refused to move.

On the third day, a van arrived bearing the seal of the county coroner’s office.

Two men in white suits carried stretchers into the tunnel.

An hour later, they emerged with a long black bag, stiff with shape.

Mariah’s breath caught in her chest.

Even from a distance, she could see the faint outline of shackled arms pressed against the inside of the bag.

Her instincts screamed the truth, but the deputies gave her nothing.

One leaned close to her window and muttered, “You want answers? Stop looking.

He’s gone.

Let him stay gone.

” But she didn’t stop.

By that evening, Mariah had already contacted a friend in Rapid City, a young journalist named Alan Pierce.

He had covered native issues before and had earned her trust.

“Meet me,” she told him.

“There’s something they don’t want us to see.

” Allan drove down that night, his notepad ready, his camera hidden under the seat.

Together, they sat outside the barricade, watching as trucks hauled debris away.

Allan whispered, “They’re not just removing remains.

They’re cleaning the site.

That’s evidence disappearing inside the tunnel.

” The coroner’s team found more than bones.

Alongside the skeleton lay fragments of cloth, denim threads faded almost to white.

a rusted belt buckle, a pair of broken glasses, their frames bent beyond repair, and tucked near the ribs covered in dust, the remnants of a leather notebook.

Most of its pages were rotted to pulp, but the cover bore faint etchings of beadwork patterns, the same kind Mariah had seen her brother draw countless times in the margins of his notes.

It was Michael.

The shackles told the rest of the story.

His wrists and ankles had been chained directly into the rock.

The iron was corroded, fused to bone in places where time had bitten deep.

The position of the skeleton suggested he had been left sitting against the wall, unable to stand.

His skull bore a fracture above the temple as if struck by a blunt object.

The forensics would later reveal signs of starvation, dehydration, and blunt force trauma.

He hadn’t simply died.

He had been imprisoned, left to wither in the dark.

When Mariah learned these details through Allen’s source inside the coroner’s office, she collapsed into a chair at home, trembling so violently she could barely hold her pen.

She wrote it all down in her notebook, every grizzly detail, every item recovered.

Her mother, Eliza, sat quietly nearby, staring at the candle light.

“I told you,” she murmured.

He said he was cold.

“But grief was not the only feeling that took root that night.

” Rage swelled inside Mariah, hot and consuming.

For 18 years, Sheriff Lawson had called Michael a runaway, a troublemaker, a ghost.

But the truth lay shackled in chains pulled from the earth.

This was no runaway.

This was murder.

When she demanded a public statement, Lawson appeared at a press conference, his mustache thicker, his face weathered, but defiant.

Cameras flashed as he said, “The remains found at Red Creek are under investigation.

There is no evidence at this time linking them to Mister Redbird.

We urge the public not to speculate.

Speculate.

The word burned through Mariah’s chest.

The belt buckle, the glasses, the notebook, the limp her brother carried in life.

All erased again by the very man who had silenced him.

But Mariah was no longer a frightened 22year-old.

She was hardened by 18 years of silence.

18 years of watching her family crumble.

She looked Lawson in the eye and vowed, “If you won’t tell the truth, I will.

” And with Allen by her side, pen in hand, camera ready, she prepared to drag the story into the light.

Because Michael Redbird had not died in vain.

His bones told the story he had once written in his notebook.

A story of corruption, betrayal, and chains hidden beneath the earth.

And for the first time in nearly two decades, the Redbird family had proof.

The photograph of the shackled skeleton never made it into the official record.

Alan Pierce’s source inside the coroner’s office had risked his job to slip him a copy.

grainy, black and white.

The bones slumped against stone, chains coiled like snakes around wrists and ankles.

Allan held it in trembling hands the night he showed it to Mariah.

She didn’t cry.

She didn’t flinch.

She stared at the image until her eyes burned.

“That’s him,” she whispered.

“That’s my brother.

” Alan pressed the photo flat against the table.

If we publish this, they’ll come after us.

But if we don’t, they’ll bury it again.

Mariah leaned forward, her voice low but steady.

For 18 years, they’ve told us he ran away.

Now we have proof.

We publish.

The next week, Allen’s article appeared in the Rapid City Journal.

The headline read, “Remains found in Tunnel May belong to missing Lakota activist.

” The story was cautious, filled with the language of alleged and possible, but the photograph spoke louder than words.

Readers saw the shackles.

They saw the bones.

They saw the truth Lawson wanted erased.

The backlash was immediate.

Native communities across South Dakota erupted with anger.

Old stories resurfaced.

Other activists harassed.

others who had disappeared under suspicious circumstances.

For the first time in nearly two decades, Michael Redbird’s name was on the lips of thousands.

But with exposure came danger.

Two nights after the article was published, Allen’s car was broken into.

His camera was stolen, his notes scattered across the pavement.

Days later, Mariah returned home to find her mailbox pried open, its contents missing.

And then came the phone calls.

Dead air at first, then a voice growling, “Stop digging or you’ll join him in the dark.

” Mariah didn’t stop.

She and Allan dug deeper.

They tracked down former mine workers, men who had been young and desperate in the late 80s, who now carried guilt heavy as stone.

One, his hands trembling over a glass of whiskey, admitted, “They brought him there.

I saw it.

The van pulled up one night, deputies inside.

They dragged him, still fighting, into the tunnel.

We heard him screaming for two days.

Then nothing.

When Allan asked why he hadn’t spoken sooner, the man’s eyes filled with tears.

Because Lawson said, “If we talked, we’d be next.

And some who did talk, they were next.

” Each testimony chipped away at the wall of silence.

Patterns emerged.

Deputies moonlighting as company guards.

Envelopes of cash exchanged in backrooms.

Reports filed and then erased.

The closer Mariah and Allen came to the truth, the more resistance they faced.

The sheriff’s office held another press conference, this time doubling down.

Lawson himself leaned into the microphone.

There is no conclusive evidence linking the remains to Mister Redbird.

We believe the individual was likely a transient who entered the tunnel and died there.

Mariah stood at the back of the room, fury courarssing through her veins.

She clutched her brother’s broken glasses in her pocket, the ones recovered from the tunnel, the ones the sheriff conveniently never mentioned.

When reporters began shouting questions, Lawson ended the briefing abruptly, storming out.

Cameras swung toward Mariah, microphones thrust into her face.

For the first time, she spoke publicly.

My brother was not a transient.

He was shackled.

Shackled for telling the truth, and those who chained him there still walk free.

The clip aired on local stations, then spread nationally.

For the first time, America heard the voice of the Redbird family.

But with national attention came new forces.

Federal agents arrived, announcing an independent review of the remains.

The mining company issued a statement denying any involvement.

Politicians who had once shaken hands with Lawson began to distance themselves.

Yet Mariah felt no relief.

She had seen this play before.

investigations that led nowhere, inquiries that fizzled out.

The system had always protected its own.

Late one night, Allan placed a folder on her table.

Inside were documents yellowed with age, purchase orders, payroll records, signatures.

Look here, he said, pointing to a name.

Deputies were on company payroll in ‘ 87, paid as security consultants.

This is the paper trail.

Lawson wasn’t just turning a blind eye.

He was part of it.

Mariah closed her eyes.

She could almost hear her brother’s voice again, urging her not to give up.

For years, she had carried his absence like a stone around her neck.

Now, she carried something else, his unfinished fight.

And she knew this fight would not end with an article or a press conference.

It would end only when the chains in that tunnel dragged the sheriff himself into the light.

By the summer of 2005, the story of the shackled skeleton had spilled far beyond South Dakota.

National newspapers picked it up.

TV anchors repeated Michael Redbird’s name, and suddenly a man who had once been dismissed as a troublemaker was being remembered as a silenced activist.

Mariah watched the coverage from her living room, her mother asleep in the next room, a quilt pulled up to her chin.

On the television, commentators spoke of possible civil rights violations and historic injustice.

To Mariah, it was surreal.

For 18 years, she had screamed into the void, and now the whole country was listening.

But not everyone wanted the truth unearthed.

Threats escalated.

One morning, Mariah found her front door spray painted in red, liar.

The same day, Allen’s editor at the Rapid City Journal received a letter from a law firm threatening legal action for defamation.

Deputies loitered outside Mariah’s trailer at night, headlights pointed at her windows until dawn.

She refused to move.

Allan, however, felt the pressure in other ways.

His editor demanded he back off, claiming the paper couldn’t risk lawsuits.

When Allan resisted, his office was searched on a routine compliance check.

Files were taken.

The message was clear.

Stop digging.

But Allan had already found enough to keep going.

The payroll records were just the beginning.

He and Mariah uncovered minutes from a 1987 county commissioner meeting where special security services had been approved for the mining company.

The signatures included Lawson.

Buried in an appendix was a budget line labeled containment measures.

Containment.

It was the kind of word bureaucrats used to hide horrors.

And for Mariah, it was confirmation that Michael hadn’t been silenced by accident.

He had been contained just as the documents said.

Meanwhile, the coroner’s office quietly finalized their report.

Though heavily redacted, Allen’s source slipped him a draft.

The findings were unmistakable.

Fractures to the skull, shackles fused to bone, cause of death consistent with prolonged confinement.

The words likely homicide appeared.

though the sheriff’s office refused to release them publicly.

When Mariah confronted Lawson at a town hall meeting, the encounter was captured on shaky camcorder footage that later went viral online.

She stood in the aisle, her voice shaking but unbroken.

You left him there.

You let him die in chains.

18 years you called him a runaway and all along you knew.

Lawson’s face reened.

You don’t know what you’re talking about, he snapped before storming off stage.

The room erupted in murmurss.

For the first time, cracks appeared in his armor of authority.

Some of his longtime supporters shifted uneasily.

Others avoided his gaze.

Still, the fight was far from over.

Behind closed doors, federal investigators debated jurisdiction.

Was this a civil rights case, a homicide, a cold case beyond the statute of limitations? Each argument dragged the process into endless loops of bureaucracy.

Mariah knew exactly what was happening, stalling.

“They’re waiting for us to give up,” she told Alan one night, staring at the candle still burning by her brother’s empty chair.

“But we can’t.

If we stop now, Michael dies again.

Allan nodded.

Then we keep going.

Even if it kills us, they pushed harder.

They tracked down another witness, a former deputy now living in Nebraska, who had resigned in 1988.

At first, he denied everything.

But after hours of questioning, he broke.

I was there the night they took him.

The man whispered, hands trembling.

Lawson ordered it.

said Redbird was making too much noise.

They chained him in that tunnel, told us it was temporary just to scare him.

But then days passed.

He begged for water.

He begged.

The man’s voice cracked.

They never let him out.

Allan recorded every word.

This testimony combined with the physical evidence could have blown the case open.

But when Allan brought it to federal prosecutors, the response was chilling.

This witness is unreliable.

His statement cannot be verified.

Unreliable.

The same word Lawson had used 18 years earlier.

It was then Mariah realized.

They were not just fighting a sheriff.

They were fighting an entire system built to protect him.

Still, she refused to stop.

If the law won’t take him down, she told Alan, then history will.

will carve Michael’s truth into stone so no one can erase it again.

And though she didn’t yet know it, her words would prove true.

Because in the weeks ahead, another discovery would surface, one that even Lawson could not bury.

The weeks after the deputy’s confession felt like standing on the edge of a cliff.

Mariah and Allan had evidence, testimony, even photographs.

But still, the system refused to move.

Every request for justice was met with the same shrug, the same bureaucratic walls.

It was as if Michael’s bones had been unearthed, only to be buried again under paperwork.

But then, by chance came something no one had expected.

In June of 2005, workers clearing brush near an abandoned outuilding close to the Red Creek Mine stumbled upon a rusted metal trunk.

It had been hidden beneath decades of weeds and debris, its hinges swollen shut with rust.

They thought it was old mining equipment, but when one worker pried it open, his face drained of color.

Inside were stacks of folders, their paper yellowed, their corners chewed by mice.

On top of the pile lay a badge, tarnished, but still legible.

The name plate read Deputy R.

McCall.

The trunk was quietly turned over to the sheriff’s office, but Allen’s source inside tipped him off before it disappeared into storage.

“You need to see this,” the source whispered.

That night, in a dimly lit diner booth, Allan and Mariah flipped through the files.

What they found was worse than either of them had imagined.

Inside were internal memos from the mining company, typed letters stamped with company letterhead discussing containment measures for activist interference.

One memo dated July 7th, 1987 listed Michael Redbird’s name explicitly.

Subject Redbird must be neutralized.

Coordination with local law enforcement confirmed attached was a list of expenses, including overtime payments to deputies, fuel costs for transport vehicles, and one line item that froze Mariah’s blood, materials for tunnel confinement, chains, bolts.

The trunk also contained photographs, grainy polaroids taken in the late8s.

One showed Michael’s pickup truck parked outside a mining out building.

Another showed a black van, its license plate partially obscured.

A third, most haunting of all, showed Michael himself, seated in a chair, his arms bound behind him, his face bruised, but his eyes burning with defiance.

Mariah’s hands shook as she held the photo.

She had never seen her brother in chains, but here it was.

The proof that he had been captured, held, tortured.

Proof they could never deny.

Allen’s face was pale.

This This is a smoking gun.

They can’t explain this away, but they tried.

When Mariah and Allan brought the documents to the federal investigators, the reaction was a mix of alarm and dismissal.

“These could be fabrications,” one official said flatly.

“Without verified provenence, they’re inadmissible.

” “Fabrications,” Mariah slammed her fist on the table.

“You think I staged photographs of my brother in chains? You think I typed up letters from a mining company that shut down 20 years ago? He died in your backyard and you call it fabrication.

The officials didn’t answer.

Frustrated but undeterred, Mariah and Allan went public.

They held a press conference on the steps of the courthouse, laying the documents out for cameras.

Allan projected the photographs onto a screen.

The van, the truck, and finally Michael’s bruised face.

Gasps rippled through the crowd.

“This is not rumor,” Mariah said, her voice steady despite the tears in her eyes.

“This is not speculation.

This is evidence.

” My brother was taken.

He was shackled.

He was left to die with the blessing of those sworn to protect us.

The image of Michael, chained and defiant, swept across television screens and newspapers nationwide.

The public outrage that followed was unlike anything the county had ever seen.

Demonstrators marched outside the sheriff’s office holding signs that read, “Justice for Redbird and end the silence.

” For the first time, Lawson himself looked shaken.

His once confident stride faltered as he walked past reporters.

His words grew defensive, clipped.

This is nothing but a smear campaign.

He barked, but his voice no longer carried the weight it once had.

The cracks in his shield were widening.

Yet danger lurked closer than ever.

One evening, as Mariah drove home, headlights flared in her rear view mirror.

A truck tailed her for miles, closing the gap, pressing her bumper.

She swerved onto a side road, her heart hammering, and the truck peeled away into the night.

The message was clear.

Someone was desperate to stop her.

But it was too late.

The truth had already clawed its way into the light.

The trunk had spoken.

The photographs had spoken.

And Michael himself, his bones, his chains, his defiant eyes, was finally telling the story they had tried to erase.

And though the fight was far from over, Mariah knew.

The system could no longer bury her brother.

The trunk had blown the story wide open, but it also lit a fuse that no one could put out.

Overnight, Michael Redbird became a name carried across the nation.

Not as a missing person, not as a rumor, but as a man shackled and silenced by those in power.

Native communities rallied.

Protests swelled outside the courthouse.

Drums echoing through the streets.

Voices chanting Michael’s name.

Banners demanded investigations, demanded justice, demanded that the sheriff be removed.

For the first time in nearly two decades, the Redbird family wasn’t alone.

But the louder the protests grew, the more desperate the push back became.

Local newspapers loyal to the sheriff printed editorials questioning the authenticity of the trunk.

They called it a hoax, a stunt pulled by radical activists.

Anonymous flyers circulated smearing Michael as a criminal, dredging up old arrests for trespassing during protests.

The goal was clear.

To paint him as unworthy of sympathy, even in death.

Mariah recognized the tactic.

They killed him once with chains, she told Alan.

And now they’re trying to kill him again with lies.

But lies were no longer enough.

The pressure mounted until federal investigators could no longer ignore it.

A task force was announced, bringing in forensic experts from outside the state.

They re-examined the shackles, the fracture in Michael’s skull, the remnants of his notebook.

The conclusion was unanimous.

Homicide.

When the report leaked to the press, the county erupted.

Lawson could no longer stand at a podium and call Michael a runaway.

The world now knew what the family had always known.

Michael had been murdered.

Still, the question remained.

Who gave the order? That answer came from within Lawson’s own circle.

A retired deputy, once one of Lawson’s most loyal men, finally stepped forward.

He was gaunt, his voice grally with age, but his testimony shook the foundations of the county.

We were told to make an example of him, the man said.

Lawson gave the order.

The mining company paid us cash.

We took him to the tunnel.

I held the flashlight while they chained him.

I’ll never forget his eyes.

He kept shouting, “My people will remember this.

” And then they left him there.

Days later, we poured concrete over the entrance.

Lawson said it was done.

The statement spread like wildfire.

Lawson denied it, of course, calling the man scenile and bitter, but the details matched everything Mariah and Allen had uncovered.

The payroll records, the photographs, the memos, and then came the final blow.

A forensic accountant brought in by the task force traced financial records back to 1987.

He found deposits, large sums of money transferred from the mining company to accounts connected to Lawson’s deputies.

The description line on one deposit read, “Special security services.

” The same words used in the county commissioner minutes, the same words buried in the trunk.

It was the paper trail they had all been waiting for.

By autumn of 2005, the case was no longer just a local scandal.

It was national news.

Lawson was subpoenaed to testify.

Cameras swarmed the courthouse as the once untouchable sheriff shoveled past reporters.

No longer striding, no longer defiant, but cornered.

Inside the courtroom, Mariah sat in the front row, Michael’s broken glasses clenched in her hand.

When Lawson took the stand, his mustache twitching, sweat on his brow, she stared at him with unflinching eyes.

He denied everything.

He claimed ignorance, claimed the documents were fake, claimed the witnesses were liars.

But the evidence was stacked too high, the chains too loud, the bones too clear.

Every denial rang hollow.

When Mariah left the courthouse that evening, the crowd outside erupted into chants.

Justice for Redbird.

Justice for Redbird.

The sound rolled through the streets, carried by drums, carried by voices that Lawson could no longer silence.

For 18 years, Michael’s story had been buried in darkness.

Now, it was being spoken in the light of day.

But justice, Mariah knew, was not guaranteed.

The system that had buried her brother was the same system now pretending to uncover the truth.

And systems do not easily condemn themselves.

Still, as the sun dipped behind the black hills, she felt something she hadn’t felt in years.

Not closure, not yet, but possibility.

The chains had been unearthed.

The truth had been spoken.

And Michael’s voice, once silenced in a tunnel, was echoing louder than ever.

Winter settled hard over South Dakota in late 2005.

Snow draped the hills in silence.

The same hills that had once hidden Michael’s chains.

But now the silence felt different.

Not the silence of denial, but the silence after a truth too heavy to ignore.

Sheriff Lawson resigned under pressure before his trial even began.

Officially, he claimed health reasons.

Unofficially, he had become a pariah.

His decades of power crumbling in months.

The mining company facing lawsuits and boycots quietly dissolved.

Rebranding under another name like a snake shedding its skin.

But everyone knew what they had done.

For Mariah, none of it felt like justice.

Her brother was still gone.

The courtroom, the subpoenas, the headlines, they couldn’t bring him back.

And yet, for the first time in 18 years, she could stand over the ground where he had been shackled and say, “They can’t erase you anymore.

” Michael’s remains were released to the family in December.

The bones were fragile.

The shackles removed, but the marks still visible.

His broken glasses and rusted belt buckle were returned in a small evidence bag.

Mariah carried them home like relics, sacred and unbearable.

The funeral was held on a frozen morning, the wind biting at exposed skin.

Hundreds came, family, neighbors, activists, strangers who had read his story and felt his fight in their bones.

Drums echoed through the air.

Voices rose in song.

And for once, the Redbird family didn’t stand alone in their grief.

They buried Michael on a hill overlooking the river he had once fought to protect.

As the coffin lowered, Mariah placed his notebook, what little remained of it, on top.

Pages rotted, words blurred, but its weight was symbolic.

“You wrote the truth,” she whispered, and the earth carried it back to us.

Her mother, Eliza, too frail to walk, was wheeled to the graveside.

She reached out with trembling hands, touched the coffin, and whispered the words she had repeated for years.

He says he’s cold.

And then, as if releasing something she had carried too long, she added, “But now he’s home.

” The story of Michael Redbird did not end at his funeral.

His name became a rallying cry.

Colleges held lectures in his honor.

Documentaries replayed the grainy photographs.

Activists cited his case in speeches about missing and murdered indigenous people.

His chains became symbols not just of his death, but of the system that had shackled thousands of native voices before him.

Allen’s article series expanded into a book documenting the cover up, the corruption, the decades of silence.

And though threats continued, the truth was too widely known to be buried again.

For Mariah, the fight never stopped.

She attended every rally, every hearing, every gathering where Michael’s name was spoken.

She wasn’t chasing justice anymore.

Justice, she had learned, was fragile, conditional, often denied.

What she sought now was remembrance to make sure her brother’s story was told again and again until forgetting became impossible.

In the final moments of her testimony before Congress years later, she held up her brother’s broken glasses.

Her voice carried through the chamber, steady as stone.

They wanted to silence him.

They wanted to bury him in chains.

But my brother’s voice is louder now than it has ever been.

And if this country refuses to listen, then the chains will rattle forever.

The room was silent.

Then the cameras clicked and history recorded the moment.

Michael Redbird had vanished in 1987.

For 18 years, his family lived in grief and uncertainty.

But when his skeleton was unearthed, shackled in darkness.

It revealed not just the fate of one man, but the truth of a system built to erase native lives.

And though his bones now rested beneath sacred ground, his story would never rest.

His story had become a torch passed from his hands to his sisters, from his sisters to the world.

In the end, Michael’s voice was not erased.

It was carried in the wind across the hills of South Dakota, a reminder that truth can be buried, but never silenced.

News

2 Woman Soldiers Vanished Without a Trace — 5 Years Later, a SEAL Team Uncovered the Truth…

In October 2019, Specialist Emma Hawkins and Specialist Tara Mitchell departed forward operating base Chapman on what their unit was…

Pilots Vanished During a Secret Operation in WW2 — 50 Years Later, Navy Pulled This From the Ocean…

In March 1944, Captain James Carter took off from an airfield in Eastern England on what his squadron was told…

Entire Orphanage Vanished in 1968 — 40 Years Later, a Hidden Room Shocked Investigators…

In 1968, the entire Willoughbrook orphanage vanished overnight. 43 children, six staff members gone without explanation. No bodies were found….

Farmer Vanished in 1996 — 15 Years Later, His Family Made a Shocking Discovery…

On the morning of September 14th, 1996, Walter Drummond kissed his wife Dorothy goodbye, climbed onto his farmal tractor, and…

Fighter Pilot Vanished in 1944 — 70 Years Later, Her Plane Was Found Abandoned in a Forest…

In November 1944, Evelyn Whitmore took off from a military airfield in Delaware on what her family was told was…

Yosemite Couple Vanished — Found 3 Years Later Buried Upside Down, Only Legs Showing

In May of 2020, volunteers working in the Long Meadow area stumbled upon human remains long thought to be lost…

End of content

No more pages to load