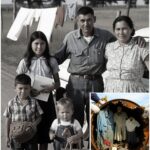

In the summer of 1963, a native family of five climbed into their Chevy sedan on a warm evening in Red Willow, Oklahoma, and they were never seen again.

Daniel and Margaret Redbird, their 12-year-old daughter Anna, their 8-year-old son James, and little Samuel, barely 2 years old, seemed to vanish into the night.

No car was found, no tracks, no trace, just silence.

For weeks, relatives begged the sheriff’s office for answers.

Deputies shrugged it off, calling it a possible runaway, but neighbors whispered that the Redbirds had made enemies, powerful ones.

Daniel had been fighting for fair pay and safer conditions for native workers.

Margaret had been teaching tribal history that others wanted forgotten.

And in 1963, challenging the wrong men could mean more than losing a job.

It could mean losing everything.

Decades passed.

The house where the Redbirds once lived crumbled into weeds.

Their names faded from newspapers, dismissed as another unsolved disappearance.

But for their families, the wound never closed.

They waited year after year for something, anything to surface.

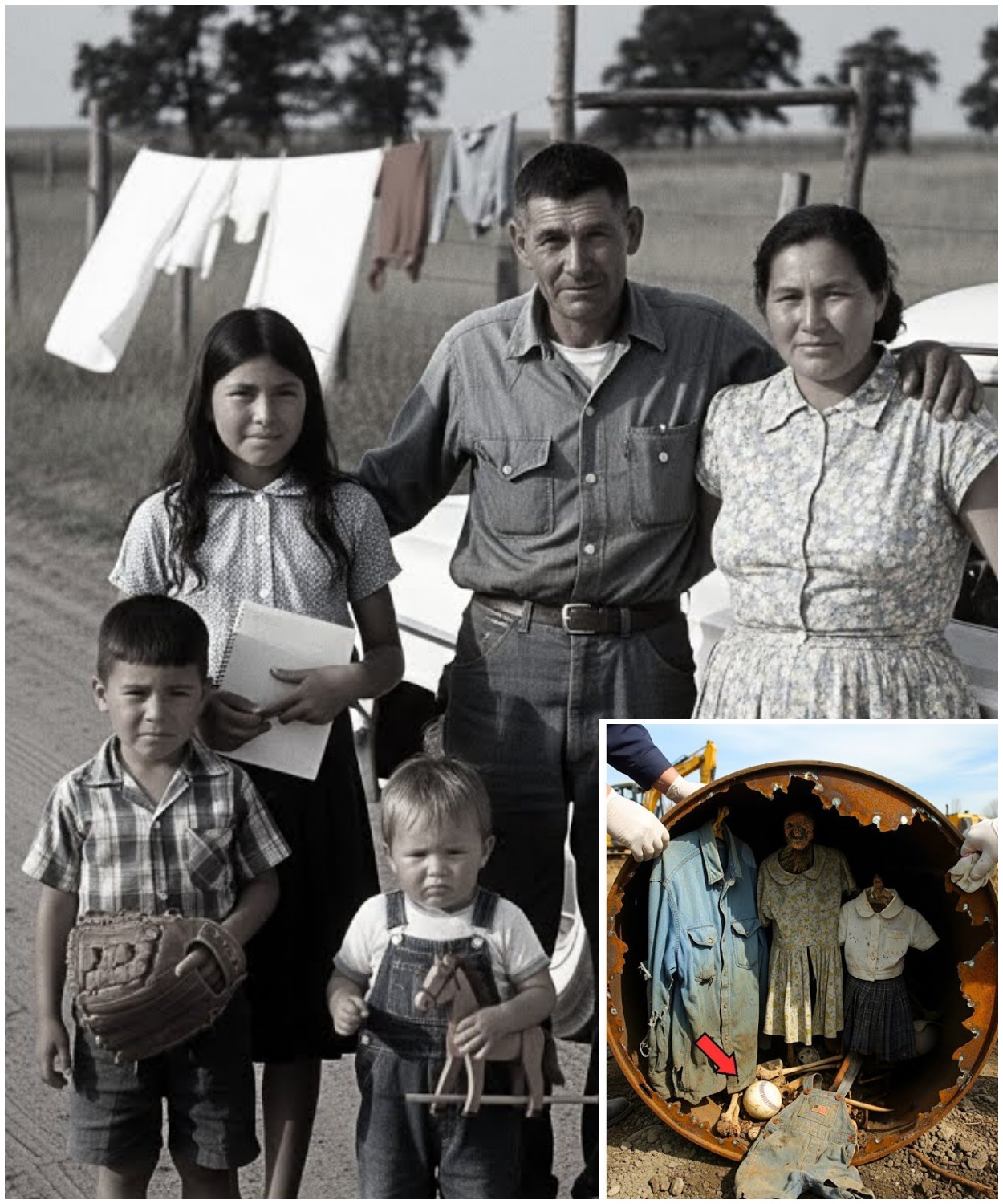

And then 39 years later in 2002, a construction crew digging near Tulsa struck something buried deep in the earth.

A massive rusted oil drum sealed tight, wedged under layers of dirt and concrete.

At first, they thought it was industrial waste left behind from an old job site.

But when authorities pried it open, what they found inside wasn’t trash.

It was something strange, something no one expected, something that would reopen one of the darkest and most haunting mysteries in Oklahoma history.

Long before the Redbirds became a headline, their lives carried the weight of conflict and quiet defiance.

Daniel Redbird at 36 was an iron worker whose name was known across half the job sites in Oklahoma.

He was strong, the kind of man who climbed steel frames without hesitation.

But what made him memorable wasn’t just his work.

It was his voice.

On paydays, when native workers got envelopes lighter than their white counterparts, Daniel was the one who spoke up.

on job sites where scaffolds shook in the wind without guardrails.

He was the one who demanded safety lines.

He wrote down names, dates, accidents, and missing wages in a leather notebook he carried everywhere.

And every time he opened it in a foreman’s office, silence would fall.

But in 1963, men like Daniel weren’t celebrated.

They were marked.

Contractors called him a problem.

Union bosses, some with deep ties to developers, whispered that he was stirring trouble among the men.

A fellow worker once warned him, “You keep this up, Redbird, and they’ll make sure you don’t come home one night.

” Daniel only smirked, replying, “Then let them come.

I won’t vanish as easy as they think.

” At home, Margaret fought her own battle.

She was 34, a teacher at the reservation school, tasked with teaching outof-date history books that described native people as relics.

Margaret refused.

She told her students about treaties broken, about grandparents who still remembered forced removals, about the truth.

Her classroom became a place of quiet resistance, and though children adored her, officials took note.

At one school board meeting, she was told flatly, “Stick to the lessons in the book or you’ll lose your job.

” Margaret walked out without replying.

Their three children were the heart of the family.

Anna, 12, filled notebook pages with dress sketches, dreaming of one day becoming a designer.

James, 8, carried a beat up baseball glove wherever he went.

his heroes, not ball players on the radio, but the local boys who played on the dusty reservation fields.

And Samuel, two years old, barely talking, clutching a toy horse everywhere he toddled, was the joy of their evenings.

For all the tension and threats outside, their home was filled with laughter.

Chalk drawings on the porch and lullabibis hummed before bed.

But shadows had begun to creep closer.

Neighbors noticed black sedans idling on dirt roads near the Redbird house.

Men in suits smoking silently, their faces unfamiliar.

Daniel’s tires were slashed twice in one month.

A dead crow was left on their doorstep.

Margaret confided to her sister that someone had offered her hush money.

A thick envelope to convince Daniel to stop his complaints.

“They don’t just want him quiet,” she whispered.

They want us gone.

Daniel knew the danger.

After one union meeting, he returned home with a deep unease.

They told me I’ve got one last chance, he admitted, pacing the kitchen.

They said if I don’t stop, it won’t be just me they come for.

Margaret tried to calm him, but she too had begun to sense it.

The feeling of being watched followed weighed.

And then came the night, June 1963, a warm evening.

Cicas buzzing in the fields, neighbors waving as the Redbirds loaded into their Chevy sedan.

Margaret buckled Samuel into the back seat.

Anna clutched her sketchbook.

James tossed his glove onto his lap.

Daniel gripped the steering wheel tightly, jaw clenched.

To the neighbor who asked where they were going, he muttered, “They won’t let this go, but I won’t let them take what’s ours.

” The sedan pulled away into the night.

Headlights flickered once around the bend, and then nothing.

For days, relatives scoured the countryside, checking rivers, bridges, quaries.

The sheriff’s office barely lifted a finger.

Deputy shrugged, suggesting the family might have wanted a fresh start.

The newspaper printed a single thin column on page six.

Local family missing.

Authorities suspect voluntary departure.

But in Red Willow, no one believed it.

Families don’t vanish overnight.

Teachers don’t walk away from classrooms.

Iron workers don’t abandon their notebooks of evidence.

And toddlers don’t choose to disappear.

The Redbirds hadn’t run.

They had been taken.

And while the official record grew cold, whispers across the reservation only grew louder.

Someone had silenced them.

Someone powerful.

The morning after the Redbirds vanished, the small community of Red willow fell into a silence that felt unnatural.

Margaret’s students arrived at school to find their teacher absent, her desk neat, her chalkboard clean, as if she had planned to return.

At the union hall, men looked around for Daniel, waiting for him to stride in with his leather notebook tucked under his arm, but the chair he usually claimed sat empty.

Anna’s friends knocked on the family’s door after school, clutching a ball and glove, expecting to see her sketching on the porch.

Even little Samuel’s toys were still scattered on the living room rug, frozen midplay.

When relatives finally contacted the sheriff’s office, the response was dismissive.

Deputies drove by the Redbird home, jotted a few notes, and left.

No search teams, no alerts, no urgent radio calls to neighboring towns.

When the family pressed harder, demanding roadblocks and river drags, the sheriff smirked and said, “Folks, leave families, too.

Maybe they wanted a new start.

” His words cut like a knife.

No one in Red Willow believed it.

But the message was clear.

The authorities weren’t going to help.

For weeks, the family and neighbors organized their own search parties.

They combed the countryside, scanning ditches and riverbanks, asking farmers if they’d seen a Chevy sedan on the back roads.

A trucker swore he saw headlights that night trailing the Redbird car, but no report was filed.

A rancher claimed he heard shouting near the highway, but deputies never investigated.

Every lead faded into silence.

What angered the community most was the way the local press handled it.

The Tulsa Daily Tribune ran a tiny piece on page six.

Family of five missing.

Possible relocation.

No photo, no urgency, just a few lines suggesting the Redbirds might have left on their own.

By the following week, there was no mention at all.

It was as if the family had never existed.

Meanwhile, whispers spread about who might be pulling strings.

Some pointed at the contractors Daniel had been challenging.

Others suspected the union bosses already nervous about exposure.

A few spoke of deputies seen drinking late into the night with men in suits from Tulsa.

Men who had no reason to be on reservation land.

Margaret’s sister Ruth refused to stay silent.

She gathered friends and held vigils outside the courthouse, holding up handpainted signs with the Redbird children’s names.

Anna, James, Samuel, bring them home.

Photos show her standing alone on the steps while county officials walked past as though she weren’t there.

One reporter snapped a picture, but the article was killed before it could be printed.

By then, the message was undeniable.

Someone wanted the Redbird disappearance forgotten.

In Red Willow itself, fear began to spread.

Neighbors who had once spoken openly about seeing black sedans idling near the Redbird home stopped talking.

A man who had joined the search told others to leave him out of it.

His job at the quarry depended on it.

Even the priest who had baptized Anna and James said little, warning Ruth only that some doors once opened cannot be closed.

The years passed and the file marked Redbird family missing gathered dust in the sheriff’s office.

No investigation was reopened.

No evidence pursued.

The Chevy sedan might as well have dissolved into air.

For the outside world, the story was over before it began.

But inside Red Willow, it lingered like a wound that never healed.

Every time a car’s headlights appeared on a dirt road late at night, families shuttered their windows, reminded of how easily lives could be erased.

By the 1970s, the Redbird name had become both a symbol and a warning.

For younger workers, Daniel was remembered as the man who stood up for fairness and disappeared for it.

For teachers, Margaret became the example whispered about in staff meetings, the woman who told the truth and was silenced.

And for the children of Red Willow, Anna, James, and Little Samuel were like shadows, names carved into memory, but no graves to visit.

The official story remained that they had simply left.

But no one in the community believed it.

Families don’t just abandon their homes, their jobs, their classrooms, their toys.

No, something had been done to them.

Something brutal, something deliberate.

And though the world had moved on, the people of Red Willow carried an unshakable conviction.

One day, the truth would surface.

And when it did, it would be far darker than anyone dared imagine.

By the mid 1970s, the Redbird disappearance had settled into the uneasy category of unsolved, the kind of story people whispered about over coffee, but never spoke too loudly.

The official record sat in the county archives no thicker than a few pages.

a missing person’s report, a single newspaper clipping, and a typed note that read simply, “No further leads.

” For the sheriff’s office, the case was closed in everything but name.

For the Redbird family, it was a wound that never healed.

Ruth, Margaret’s sister, refused to let it fade.

Every year, on the anniversary of the disappearance, she stood outside the courthouse with the same cardboard sign.

Where are the red birds? By the late ‘7s, her hair had gone gray, but she was still there, her hands trembling, but her resolve unbroken.

Sometimes, a few supporters joined her.

Other times, she stood alone.

Passing officials rarely looked her way.

People in power wanted her silence, but Ruth never gave it to them.

Meanwhile, the community of Red Willow carried the loss like a shadow.

Children who grew up in the years after the disappearance learned the story as a kind of cautionary tale.

Speak too loudly.

Push too hard and you might vanish like the Redbirds.

Teachers spoke Margaret’s name in hushed tones, reminding new staff why the textbooks in their classrooms were so strictly controlled.

Among workers, Daniel was remembered as the one who carried a notebook full of evidence and paid for it.

The story wasn’t just a mystery.

It had become a symbol of what happened when native families resisted the wrong people.

But beneath the silence, rumors refused to die.

In the early 1980s, an elderly rancher claimed he’d seen headlights near an abandoned quarry on the night of the disappearance, followed by the sound of heavy machinery long after midnight.

A truck driver swore he’d once hauled sealed oil drums under a false manifest paid in cash by a contractor with ties to the union.

Neither testimony made it into official reports.

Both men said deputies warned them to stop asking questions.

Others remembered more sinister details.

A former worker at the Tulsa scrapyard told Ruth decades later that he once saw a sedan matching the Redbird’s car crushed and hauled off without paperwork.

Special order.

When she begged him to testify, he shook his head.

Lady, men have been killed for less.

I’ve got grandkids to think about.

The coldest years were the hardest.

By the mid1 1980s, with no new evidence, no willing witnesses, and no media interest, it seemed the case was destined to die in silence.

Ruth’s vigils grew smaller.

Younger reporters rolled their eyes at old stories.

Even members of her own family urged her to let it go.

“It’s been 20 years,” one cousin told her.

“If they were alive, we’d know by now.

If they’re gone, they’re gone.

” But Ruth refused.

“They’re not gone,” she said.

“They were taken, and one day the ground will give them back.

” Her words proved prophetic because small cracks had begun to appear in the wall of silence.

In 1989, a retired deputy, drunk at a bar, let slip to a patron that the Redbirds didn’t run.

They were put away.

The comment was dismissed as rambling, but it reignited whispers in Red Willow.

What did put away mean, and why had he said it with such certainty? In 1994, the federal government quietly unsealed a handful of union records from the early 60s.

Buried in the files were complaints signed by Daniel Redbird, each documenting unsafe conditions and missing wages.

One letter included a chilling line.

If anything happens to me or my family, know that it was not an accident.

For Ruth, this was proof.

But for the authorities, it was still not enough.

And then, just before the turn of the millennium, construction workers digging east of Tulsa struck something hard beneath the soil.

At first, they assumed it was scrap left behind by earlier projects, a rusted drum sealed shut.

The foreman ordered it hauled aside and left for disposal.

But a few men joked about the strange dents in the metal, the unusual weight, the way the welds looked deliberate.

Nothing came of it then.

The drum sat forgotten in a scrapyard lot until 2002 when new development brought machines back to the same ground.

This time the drum was unearthed and full.

Its rusted surface told of decades underground.

Welds were still visible, sealed tight, as though someone had meant for whatever was inside to never see daylight again.

At first, the crew thought it was nothing more than industrial waste.

But when investigators pried it open, what they saw inside changed everything.

It wasn’t waste.

It wasn’t scrap.

It was a secret buried for 39 years.

A secret no one was meant to find.

The morning the drum was opened in 2002, investigators thought they were dealing with nothing more than industrial refues.

Construction crews had dug it out from nearly 6 ft of packed dirt.

The metal corroded and stred orange with rust.

It was massive, heavy, and sealed in a way that suggested no one ever intended it to be opened again.

Weld seams ran jagged across the lid as though someone had torched it shut in a hurry.

For hours, it sat on the edge of the site, attracting little more than curiosity.

Then the smell began to seep through a sickly metallic odor.

the kind that makes men fall quiet.

Authorities were called in.

Deputies roped off the site, their faces pale as they circled the drum.

Some muttered it might contain chemicals, toxic waste from an old refinery.

Others suggested it was stolen cargo, but when a cutting torch finally hissed through the welded seal and the lid groaned open, everyone present realized it wasn’t waste at all.

Inside, folded in layers, were clothes, faded fabric, dusted with decay, stacked unnaturally neat for something buried so long.

A man’s work shirt frayed at the cuffs.

A woman’s dress, its floral pattern still faint under decades of grime.

Small garments, too.

A school sweater.

A child’s sock no bigger than a hand.

And beneath the fabric, as investigators pushed deeper with gloved hands, something harder scraped against the metal bones.

At first, it was just a fragment, pale and brittle under the flashlight beam.

Then another, a rib, the curve of a jaw, a child’s shoe, cracked leather, still wrapped around the skeletal shape of tiny toes.

Gasps rose from the crew as the grim realization sank in.

This wasn’t just clothing.

These weren’t discarded belongings.

This was a tomb.

The drum contained the remains of multiple individuals, all packed together, still dressed in the clothes they had vanished in.

Time had ravaged the fabric.

Rust had stained the bones, but the picture was unmistakable.

An entire family stuffed inside, sealed and buried.

The site fell silent.

Deputies who had once dismissed the case as a runaway stood rigid, unable to look too long at the tiny shoes and sweaters now laid out on tarps.

Investigators whispered among themselves, “How had this stayed hidden for so long? Who had the power to bury something like this beneath the city’s foundations and erase it from memory? News spread quickly.

The name Redbird returned to headlines after nearly four decades.

Families who had kept their grief quiet for years suddenly had confirmation of what they always knew.

The Redbirds hadn’t run.

They hadn’t disappeared by choice.

They had been murdered, sealed into a drumlike refu.

Buried and forgotten.

And yet, even in the shock of discovery, one question pressed harder than all the rest.

Who did this? And how many people had known all along? The forensic investigation began almost immediately after the drum was hauled from the construction pit.

By then, the site had become a scene of quiet horror.

Workers stood back, shaken, while investigators carefully removed each item and laid it out on plastic tarps beneath a canopy.

One by one, the objects began to tell a story that had been hidden for nearly four decades.

The first thing that struck them was the clothing.

It wasn’t random scraps of fabric tossed in with refues.

These were garments still clinging to the forms of bodies.

A man’s denim work shirt, stiff with age, its sleeves still wrapped around bone.

A floral print dress torn at the hem, but unmistakably a woman’s, stretched across a frame.

Smaller items were more haunting.

A child’s cardigan with school initials faintly stitched on the tag, cracked leather shoes no bigger than an investigator’s palm, and the discolored strap of what had once been a toddler’s overalls.

These weren’t just reminders of lives.

They were proof of an entire family buried exactly as they had lived.

The remains themselves told an even darker truth.

Forensic teams working with patients and care identified at least five distinct skeletal profiles.

The adult male, broad-shouldered, still wearing fragments of heavy work boots.

the adult female, smaller, her pelvis confirming her identity as a woman.

Then three children, one estimated around 12 years old, another eight, and the smallest, no more than two, the red birds.

Time had done its damage.

Bones were brittle, surfaces pitted from decades sealed in rust and damp earth.

Yet there were signs that could not be erased.

The man’s ribs bore fractures consistent with blunt force trauma.

The woman’s skull showed a hairline crack that suggested a violent blow.

One of the children’s armbbones was broken in a way no accident could explain.

This was no crash.

This was no natural disaster.

This was violence, deliberate, brutal, final.

Even the drum itself spoke volumes.

Welds along the lid were sloppy but thorough, sealing it tight in a rush.

Investigators noticed scorch marks on the rim, evidence of an acetylene torch.

Inside, residue tested positive for traces of industrial chemicals, likely poured in to mask odor and slow decomposition.

Someone had not only killed the red birds, but had gone to extraordinary lengths to erase them.

Forensic anthropologists reconstructed what they could.

The layering of the clothing suggested the bodies had been placed deliberately, folded in unnatural positions to fit within the steel cylinder.

The father first, then the mother, then the children, packed around them like discarded belongings.

One investigator admitted later that he couldn’t stop staring at the toddler’s tiny shoes, still tied neatly, as though someone had dressed him carefully before sealing him inside.

As news spread, the story reignited across Oklahoma.

For years, the official line had been that the Redbirds had chosen to vanish.

Now there was proof they had been murdered.

Proof sealed in steel and buried beneath concrete.

Families in Red Willow wept openly when the findings were announced.

Some were relieved simply to have answers.

Others were consumed with anger.

They knew, one elder said bitterly.

The sheriff knew.

The union knew.

They all knew.

Journalists descended on the story, snapping photos of the rusted drum, the tarps lined with bones and clothing.

National outlets began calling it the oil drum family case.

Reporters demanded answers from local officials.

How had a family of five been dismissed as runaways when they were murdered? Why had no one investigated the rumors of threats? And most damning of all, who had the power to bury them in a way that only heavy machinery and sealed welds could manage? Behind the scenes, state investigators began combing old union files, county records, and land permits.

What they found raised even darker suspicions.

In 1963, just weeks after the Redbirds vanished, a contractor with ties to McKinley Development purchased several industrial drums in cash.

Delivery logs placed them near Tulsa, the same region where the drum was found.

Paper trails, once ignored, now pointed straight back to men who had everything to lose if Daniel Redbird’s notebook of evidence had ever gone public.

The discovery of the oil drum didn’t just solve a mystery.

It blew open the possibility of a conspiracy decades old, one that reached far beyond a single family, into the very heart of how native voices had been silenced in Oklahoma’s construction boom.

And yet, for all the answers it gave, the drum left behind a deeper question.

If the Redbirds had been buried like this for nearly 40 years, how many other families? How many other voices had been erased in the same way, never to be found? The oil drum had spoken louder than any witness ever could.

For the first time in nearly four decades, there was no denying it.

The Redbirds hadn’t run away.

They had been murdered.

And now the question that echoed from Red Willow to Oklahoma City was who had buried them and who had covered it up for so long.

Investigators reopened files that had sat untouched since 1963.

What they found was chilling.

The original missing person’s report was barely two pages long, typed in vague language that made it sound as though the family had chosen to leave.

No photographs were attached.

No records of interviews with neighbors or co-workers.

A deputy’s handwritten note scrolled across the margin read simply, “Case closed.

Probable relocation.

” It wasn’t an investigation.

It was a dismissal.

Digging deeper, journalists began comparing county budgets and contractor records from the early 60s.

One lead pointed directly to McKinley development, the same company whose projects had exploded across Tulsa in that era.

McKinley had won major contracts on bridges, quaries, and municipal buildings, often relying on unionized iron workers and labor crews.

And yet, whenever native workers pushed back against unsafe conditions or unequal pay, the company was quick to cut them off or worse, blacklist them entirely.

Daniel Redbird’s name appeared repeatedly in old union logs.

At least three grievances bore his signature, all submitted in the months before his disappearance.

Each complaint accused contractors of falsifying safety reports, misplacing wages, and forcing native workers onto the most dangerous beams while their white counterparts stayed lower to the ground.

But most damning was a final note in his handwriting.

If anything happens to me or my family, this is not by choice.

That note had been filed, then ignored.

The investigators also looked at the sheriff’s office in 1963.

The sheriff at the time, Leonard Briggs, had been in office for nearly 20 years.

Old photographs showed him shaking hands with McKinley executives at ribbon cutting ceremonies.

His campaign fund had been bolstered by donations from the very men Daniel had been challenging.

When journalists pressed surviving deputies about why no proper search was conducted, one admitted off the record.

Orders came down from the top.

We were told to let it go.

Meanwhile, stories long buried began to resurface.

An elderly truck driver came forward, recalling how in the summer of 1963, he was paid cash to haul sealed oil drums to a site outside Tulsa.

He had no paperwork, no manifest, only instructions to deliver and leave.

At the time, he thought it was odd, but not his concern.

When he saw the news in 2002, he said his stomach dropped.

That drum looked just like the ones I hauled.

Even more haunting was a confession from a retired union steward recorded by his son shortly before his death.

In the tape, his voice cracked as he admitted.

The Redbird man, he had proof.

They said he was going to blow it wide open.

One night, they told me not to come to the hall.

Next morning, he and his whole family were gone.

I should have said something.

God forgive me.

I should have said something.

The circle, a group of younger activists and relatives who had never let the memory of the Redbirds die, seized on this moment.

They organized rallies, demanded accountability, and pushed the state attorney general’s office to act.

For the first time, the coverup was no longer whispered in kitchens or bars.

It was shouted in headlines.

The more investigators dug, the clearer the pattern became.

The Redbird’s murder wasn’t the act of a single violent man.

It was systemic.

It was sanctioned by silence at every level, by union bosses who feared exposure, contractors who stood to lose money, and law enforcement who chose loyalty to power over justice.

Still, there were obstacles.

Many of the men suspected of orchestrating the crime were long dead.

Others were frail, their memories cloudy, their testimonies unreliable in court.

And those still alive denied everything.

their lawyers quick to argue that the evidence was circumstantial and too old.

But the evidence wasn’t just legal anymore.

It was moral.

Families across Oklahoma began to see their own stories reflected in the Redbirds.

Other native workers had died in accidents on unsafe sites.

Other families had faced threats when they complained.

The Redbird’s case had cracked something open, exposing not just a murder, but a pattern, one that had been hidden for decades under layers of concrete, corruption, and fear.

By the winter of 2002, the case had grown too large to be buried again.

Television crews filmed vigils in Red Willow, where candles flickered beneath photographs of Daniel, Margaret, Anna, James, and Little Samuel.

A child’s shoe recovered from the drum sat in a glass case at the front of the memorial.

A stark reminder of innocence stolen.

One speaker at the vigil said it plainly.

They were treated like waste, but now the world knows the truth, and the truth cannot be buried again.

By early 2003, the Oil Drum family case had become a storm no one in Oklahoma could ignore.

The discovery of the Redbird’s remains had shaken the state, and the demand for justice grew louder each week.

For the first time in 40 years, prosecutors assembled a grand jury.

Subpoenas went out to surviving union bosses, former contractors, and even retired deputies who had worked under Sheriff Briggs.

Families gathered outside courouses holding posters of the Redbirds, their faces blurred by age and photocopies demanding answers.

Inside the courtroom, the atmosphere was heavy.

Prosecutors laid out the evidence piece by piece.

The sealed drum, the welled seams, the industrial chemicals, the fractures on the bones.

They showed Daniel’s signed complaints, his leather notebook preserved by his sister Ruth, and the testimonies of surviving workers who confirmed the threats he had received.

They played the taped confession of the union steward on a projector, his voice trembling as he admitted he knew the Redbirds had been silenced.

For a moment, it seemed as if justice was within reach.

But then came the resistance.

Defense lawyers for the accused men, some frail, some in their 90s, wheeled into court on oxygen tanks, argued that the case was too old, the evidence too degraded, the memories too unreliable.

They claimed the remains in the drum couldn’t be definitively tied to foul play, that welds proved nothing, that chemicals could have seeped naturally.

They painted the Redbird’s disappearance as tragic but unprovable.

The courtroom battles grew bitter.

Survivors shouted at the defense, accusing them of mocking the dead.

At one hearing, Ruth stood up and held out Samuel’s tiny rusted shoe, her hands shaking as she asked the jury, “Does this look like a family that ran away?” The room fell silent.

But silence didn’t equal conviction.

Behind the scenes, pressure mounted.

Local officials feared the case would tarnish Oklahoma’s booming construction industry.

Developers quietly lobbyed politicians to let the past stay buried.

Even federal investigators admitted that without living perpetrators, their options were limited.

Slowly, the case that had reignited hope for justice began to stall.

And yet, the media would not let it go.

Nightly News ran segments on the Redbirds.

Documentarians filmed interviews with former workers who described the systemic abuse native crews endured.

Journalists uncovered new stories of other native families whose disappearances had been written off as accidents or voluntary relocations.

The Redbird’s tragedy was no longer just one family’s loss.

It had become a mirror held up to the nation’s conscience.

For Ruth and the rest of the surviving family, the half measures of the courts were crushing.

A few indictments were issued, but none stuck.

The men accused of ordering the killings either day before trial or were declared incompetent to stand.

In the end, not a single person served time for the Redbird’s murders.

Still, something had shifted.

The truth was no longer buried.

The state legislature passed a resolution formally acknowledging the Redbird’s murder and the decades of systemic injustice that allowed it to be hidden.

Memorials were planned.

The circle organized a march that drew hundreds, their chance echoing through downtown Tulsa.

We are still here.

The Redbirds are still here.

For the families, it was a bittersweet victory.

Justice in the courtroom had slipped away, as it often does in true crime stories where power protects the guilty.

But justice in memory, in truth, had finally been won.

And yet, beneath the speeches and ceremonies, one question lingered in the air like smoke.

If it had taken nearly 40 years to uncover the Redbird’s fate, how many more native families had been silenced in the same way? their stories still sealed in rusted drums hidden beneath the soil waiting to be found.

In the spring of 2005, nearly 42 years after the night the Redbirds vanished, a crowd gathered on the reservation for a ceremony that many thought would never come.

At the center stood a newly carved stone memorial, simple but resolute, engraved with five names.

Daniel Redbird, Margaret Redbird, Anna Redbird, James Redbird, Samuel Redbird.

Below the names, an inscription read, “They were not forgotten.

They were taken.

We remember.

” It was a gray afternoon, but the field surrounding the stone was alive with color.

Families brought blankets and photographs, placing them at the base of the memorial.

Some laid flowers, others set down the tools of trades, a worn hammer, a pair of welding gloves, a lunch pail in honor of Daniel.

Margaret’s former students, now grown, placed notebooks with pages of handwritten stories, saying she had taught them to speak the truth.

For Anna, children pinned sketches of dresses onto the memorial.

For James, a baseball and a cracked glove.

And for Samuel, a tiny wooden horse carefully carved by a local elder who had never met him, but said he wanted the boy to always have something to hold.

Ruth, her voice thin with age but strong with conviction, addressed the crowd.

She held Samuel’s rusted shoe in one hand and Daniel’s notebook in the other.

They tried to erase them, she said, her voice breaking.

But you cannot erase a family.

You cannot erase truth.

It may take 40 years.

It may take a hundred.

But truth rises from the ground.

And today the Redbirds rise again.

Tears ran freely through the crowd.

For many, this was not only about one family.

It was about every native voice silenced in that era.

Every worker pushed from the beams.

Every child told their history didn’t matter.

The Redbirds had become more than a tragedy.

They were a symbol of survival, of resistance, of the quiet power of memory that refused to fade.

National reporters who covered the event noted how unusual it was.

A family whose story had been buried by silence, now reclaimed by an entire community.

Some compared it to other true crime cases where long-lost victims were finally given names and graves.

But here the grief was sharper because the injustice had been so deliberate.

These were not just lives stolen.

They were voices cut off for daring to demand dignity.

That evening, candles were lit along the roadside where the Redbirds had last been seen.

Dozens of flames flickered in the dark, each one carried by a child from the community.

As the procession walked toward the memorial, elders chanted softly, prayers rising into the night air.

The glow of the candles reflected in tear streaked faces, in the polished stone, in the silence of the crowd.

One by one, people stepped forward to speak the Redbird’s names aloud.

Not just Daniel and Margaret, but Anna, James, and Samuel, too.

The children who should have grown into adulthood.

who should have lived long lives, who should have been more than names carved into stone.

For Ruth, the memorial was a form of justice, though not the kind she had fought for in courts.

She stood quietly as families touched her shoulder, thanking her for never letting the Redbirds vanish from memory.

She whispered only one line in reply, “As long as someone speaks their name, they are not gone.

” And so on that spring evening, with candles burning and names echoing, the Redbirds returned, not in body, but in spirit.

Not erased, but remembered.

The story of the Redbirds did not end with the courtroom battles or even with the unveiling of their memorial stone.

In many ways, it was only the beginning because once the truth was pulled from the ground, it refused to be buried again.

Their names, Daniel, Margaret, Anna, James, and Little Samuel, became a rallying cry for justice far beyond Red Willow.

Journalists traced the case outward, finding echoes in other families who had vanished under suspicious circumstances in the same decades.

Activists pointed to records of missing native laborers whose deaths had been written off as accidents on job sites.

Women who never came home from late night shifts.

Children dismissed as runaways.

The Redbird’s discovery proved what many had feared.

These weren’t isolated tragedies.

They were part of a pattern.

For Ruth, who had spent nearly her whole life demanding answers, the knowledge was bittersweet.

She had lived long enough to see her family pulled from silence, to see their story carried across headlines, classrooms, and community halls.

But she had also seen the limits of the system.

No man had ever been convicted.

No official had ever apologized face to face.

Justice in the courtroom had slipped away, shielded by power and time.

Yet in another way, justice had been achieved through memory, through truth, through refusal to let the Redbirds vanish again.

Years later, documentary crews stood on the spot where the drum had been unearthed.

They filmed the rusted cylinder, preserved in a museum case now, stre with orange and black.

its welled seams still visible.

Inside the glass lay the remnants of clothing, the floral dress Margaret once wore, the scuffed baseball glove that had belonged to James, the tiny overall Samuel had toddled in.

Visitors stared in silence.

For some, it was too much.

For others, it was necessary.

A reminder of what happens when injustice is allowed to grow in the dark.

The Redbird’s story spread further than anyone expected.

University students studied it as a case of systemic silencing.

Lawmakers debated new protections for native families and laborers, invoking their names on the record.

In classrooms across Oklahoma, teachers spoke about Margaret’s courage, teaching history that had once been forbidden.

For many, the Redbirds were no longer just victims.

They were proof that memory could outlast even the deepest cover up.

And yet, beneath every speech and every memorial, the haunting questions lingered.

Who had welded that drum shut on that summer night in 1963? How many deputies, contractors, and union bosses knew the truth and chose silence? And most unsettling of all, how many other drums, pits, or unmarked graves still lie hidden beneath the soil, waiting to be found.

The Redbird story ends not with resolution, but with reflection.

A family of five, silenced for speaking up, erased for daring to demand dignity, discovered decades later in the most brutal of tombs.

Their killers may have escaped earthly punishment, but they did not succeed in erasing them.

Because today, their names are spoken.

Their story is told.

And when the ground gave them back, it gave back more than bones and clothing.

It gave back truth.

And truth, once uncovered, can never be buried again.

News

Native Dad and Girl Vanished — 14 Years Later An Abandoned Well Reveals the Shocking Truth….

Native Dad and Girl Vanished — 14 Years Later An Abandoned Well Reveals the Shocking Truth…. The high desert of…

An Entire Native Wedding Party Bus Vanished in 1974 — 28 Years Later Hikers Found This In a Revine…

An Entire Native Wedding Party Bus Vanished in 1974 — 28 Years Later Hikers Found This In a Revine… For…

5 Native Brothers Vanished in 1962 — 48 Years Later, Their Wagon Was Found in a Frozen River…

5 Native Brothers Vanished in 1962 — 48 Years Later, Their Wagon Was Found in a Frozen River… The winter…

Three Native Elders Vanished During a Winter Hunt in 1956 — 65 Years Later, a Drone Found This…

Three Native Elders Vanished During a Winter Hunt in 1956 — 65 Years Later, a Drone Found This… In the…

A Native Family Vanished in 1972 — 22 Years Later This Was Found Hanging In An Abandoned Mansion…

In the summer of 1972, a native mother and her two young children vanished from their small farmhouse in northern…

Native Father and His Triplet Girls Vanished — 30 Years Later This Was Found in an Abandoned Mine…

They were last seen alive on a dirt road that cut through the red canyons of northern New Mexico. Their…

End of content

No more pages to load