They were last seen alive on a dirt road that cut through the red canyons of northern New Mexico.

Their blue station wagon rattling along with the sun dipping behind the meases.

The year was 1974.

And though most people in town had already learned not to look too closely at what happened on the reservation’s edge, some still remembered.

They remembered the father, David Greyhawk, tall and weathered at 38, with shoulders bent by loss, but still strong enough to carry three little girls through a world that often refused them mercy.

They remembered the triplets, 12 years old, inseparable, each carrying pieces of their late mother’s face, but wholly their own.

Marina, the gentle one, always had her nose in a book and carried a small rosary her grandmother had given her.

Selene, the bold one, never bit her tongue, quick to stand between her sisters and anyone who dared mock them for being native or for being fatherless.

And then there was Clara, the quiet one, whose silence was not by choice.

At the age of five, a playground accident, or what the doctors insisted was an accident, had crushed her throat and stolen her voice.

Since then, she spoke through sketches, her spiral notebooks filled with drawings sharper and clearer than words could ever be.

On the afternoon of August 3rd, 1974, they piled into their father’s blue 1966 Chevy station wagon.

David had told his neighbors they were headed for a short drive out toward the canyon road.

Just to let the girls breathe the mountain air, he’d said, smiling faintly.

Though behind his eyes there was weight.

Everyone in town knew he had been a thorn in the county’s side, challenging land seizures, shouting at council meetings about mining leases and poisoned wells.

He’d once stood outside the sheriff’s office with a sign that read, “This is our land.

You cannot carve it away.

” That evening, a local rancher recalled seeing the Greyhawk station wagon slow near the turnoff by the old mine shafts, dust pluming from its tires.

Behind them, idling, was another vehicle, a county truck, its emblem faint under the fading sun.

Some said they saw two trucks that night, both painted white, engines low, their silhouettes lingering as though waiting for the family to vanish into the canyon before following.

By nightfall, the Greyhawks had not returned.

At first, neighbors thought little of it.

Families sometimes camped overnight along the canyon, but when dawn broke and the driveway remained empty, unease set in.

By the second night, worry turned to whispers.

Anna Redbird, a shopkeeper, recalled later, “I drove past their place.

The porch light was still on.

The girl’s bikes leaned against the house.

That station wagon never came back.

” The following morning, David’s cousin reported them missing.

The sheriff’s office responded with indifference.

Deputy Harlon jotted notes lazily, smirking.

Greyhawk that loudmouth probably took off.

Maybe he couldn’t handle raising three girls, but their things are still in the house, the cousin protested.

They didn’t run away.

The sheriff cut him off.

Look, folks wander.

Maybe he snapped.

Nothing to do here.

Within days, the official story settled like dust.

unstable native father overwhelmed by hardship ran off with his daughters, likely lost in the back country, but people talked quietly.

A gas station attendant swore he saw the station wagon drive by around sunset with Clara pressed against the window, her small hand gripping her notebook.

He remembered because she held it up as though trying to show someone outside.

Later, hunters swore they heard echoes of engines revving near the abandoned mine that night, long after families should have been asleep.

The search was prefuncter, almost insulting.

Deputies drove a few miles out, glanced at canyon roads, then shrugged.

No helicopters, no extended teams.

Within a week, the case file was stamped, closed, presumed lost, yet the land remembered.

For months, Anna Redbird organized vigils.

She lit candles at the trail head, whispering the girls names.

Merina, Selene, Clara.

Mothers clutched their children tighter at night.

Fathers warned their sons not to speak too loudly against the county.

And still, the whispers never died.

Two county trucks followed them.

The sheriff knew they were buried with the mine itself.

At the Greyhawk home, the silence was unbearable.

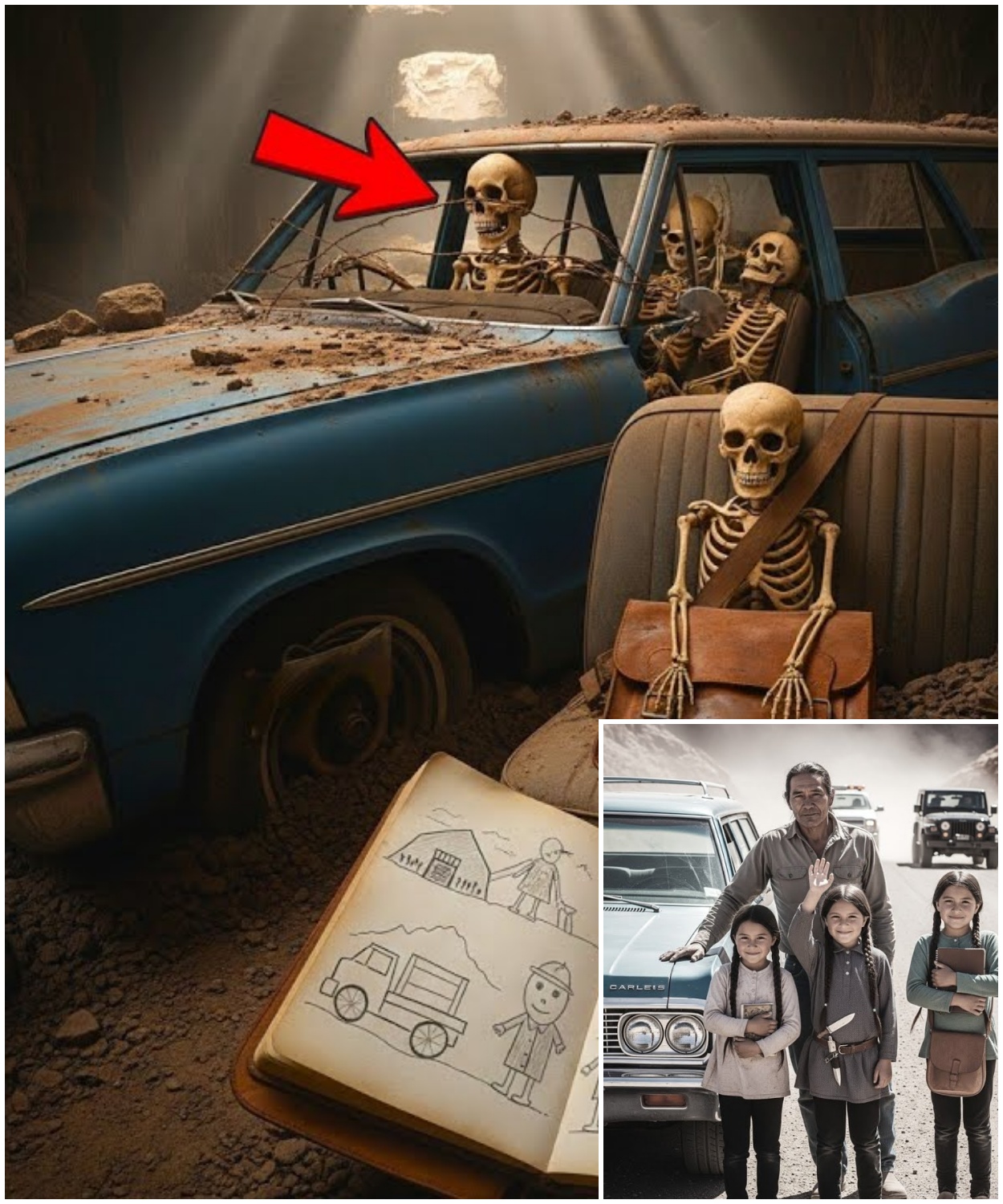

On the kitchen table, Clara’s last notebook lay open.

On its page, in rough pencil, she had drawn three stick figures holding hands beside a long blue car.

Behind them loomed square shapes with circles, trucks.

Over the trucks, faceless men with hollow eyes.

It was her last message, left like a prophecy.

The Greyhawks had vanished.

No trace, no reason.

And for 30 years, silence.

Long before the Greyhawk station wagon rattled down that canyon road, before the whispers of county trucks and mineshafts, there was a story of improbable life.

In 1962, on a cold February night, David Greyhawk paced the dirt floor of his small home, ringing his calloused hands, listening to his wife, Maria, struggle in the back room.

They had prayed for children for nearly 10 years.

Doctors in Gallup had told Maria her chances were slim.

She carried a scar from a childhood illness that they said left her body fragile.

It will be a miracle if you bear even one, the doctor had said, shaking his head.

But miracles don’t always follow rules.

That night, Maria gave birth not to one child, but to three triplet daughters.

The midwife gasped when she realized, “Three creator has blessed you three times over David, tears streaming down his face, could hardly breathe as he held the tiny girls in his rough hands.

” “Merina, Seline, Clara,” he whispered, naming them as though speaking them into existence.

But miracles come with a price.

Maria never recovered from the blood loss.

By dawn, she was gone, her hand slipping from David’s, even as her newborn daughters cried.

For the rest of his life, David carried the double weight of that night.

The gift of three lives and the crushing loss of the woman he loved.

He never remarried.

“I have enough,” he would tell neighbors who suggested it.

Three daughters to raise, three souls to guide.

I promised Maria.

And so the Greyhawk house became a world of its own.

David built cribs side by side, fed three mouths at once, learned to braid three sets of hair with clumsy fingers.

By day he worked odd jobs, repairing fences, hauling supplies, cutting wood, and by night he sang his daughters to sleep in a voice cracked with exhaustion.

The triplets grew inseparable.

At 5 years old, Marina became the caretaker, tucking her sister’s blankets when their father was late home from work.

Seline became the defender, fists baldled whenever someone called them half orphans at school.

And Clara Clara became the quiet observer, sketching on any scrap of paper she could find.

It was also at 5 years old that tragedy struck Clara.

One winter afternoon on the playground at the county school, she had an accident.

That was the word the teachers used, though David never believed it.

A group of older boys shoved her from the monkey bars, laughing as she hit the ground hard.

The fall crushed her throat.

She survived, but her voice did not.

Doctors in Gallup said the damage was permanent.

She will not speak again, they told David flatly.

David sat by her hospital bed that night holding her hand.

“Then I’ll be your voice, Clara,” he whispered.

But Clara shook her head, picked up a pencil, and scribbled in a shaky hand.

“I can draw.

” From then on, she spoke with pictures.

Her notebooks filled with sketches of the world around her.

Her sisters dancing in the kitchen.

Her father’s truck against the desert horizon.

The faces of classmates who bullied them, the looming trucks that prowled their land.

Clara’s silence became its own language.

By the time they turned 12, the triplets had become small legends in their town.

They walked together always, braids swaying in unison, eyes sharp with resilience.

Marina carried books everywhere.

Seline carried fists, and Clara carried her notebook.

People said they seemed like three parts of the same soul, mind, body, and spirit.

David, though still a man scarred by loss, found strength in them.

They are my army, he often said, my three miracles.

But being a father of triplets was not his only burden.

In the 1970s, the Navajo Nation faced relentless pressure from county officials and corporations, eager to seize land for coal and uranium.

David saw friends evicted, grazing lands cut by fences, water poisoned.

He spoke at council meetings, his voice steady.

They took my wife.

They will not take my daughter’s future.

The triplets stood beside him even as children.

Marina holding handlettered signs.

Seline chanting.

Clara sketching the scenes of protest with piercing clarity.

Their presence unnerved the officials.

Three young girls, daughters of a widowerower, standing as witnesses.

And so the Greyhawks were marked.

People whispered that David was being watched.

White trucks lingered near his property.

At night, engines growled on the horizon.

A black Jeep was seen parked by the schoolyard once, its windows tinted.

A figure inside watching Clara as she sketched.

But inside the small adobe home, life still pulsed with warmth.

The girls helped their father cook fry bread read by lantern light, laughed in the dark.

David told them stories of their mother, her laughter like rain, her strength in childbirth.

She gave her life for you three, he would say, tears glistening.

Never forget you are miracles.

On their 12th birthday, David gave each girl a small gift.

To Marina, a secondhand book of Navajo poetry.

To Selene, a pocketk knife worn but sharp.

To Clara, a leather satchel to protect her notebooks.

So your drawings never get lost, he told her.

She smiled silently, pressing the satchel to her chest.

That summer of 1974, neighbors remembered seeing the family more determined than ever.

David spoke louder at meetings, exposing contracts he had gathered.

The girl stood taller, unafraid, though whispers of threats grew louder.

And then came August 3rd, the day the blue station wagon rolled down the canyon road.

The day the three miracles and their father vanished into silence.

By 1973, the Greyhawks were no longer just a family.

They had become a symbol.

One widowed father and his three daughters standing against forces bigger than themselves.

It wasn’t supposed to be this way.

David had only wanted a quiet life, to raise his triplets, to keep the memory of Maria alive.

But silence had never been an option.

It began small.

At first, it was letters shoved under the door.

Stop speaking.

Go back where you came from.

Each one unsigned, the handwriting jagged and angry.

David burned them in the stove, but he kept the ashes, saying softly, “Ashes still prove fire.

” Then came the phone calls.

“Rings at midnight.

” David would answer, his voice thick with sleep, only to hear silence or the low growl of an engine on the other end before the line cut.

Sometimes a distorted voice muttered, “We know where your girls sleep.

” The triplets felt the tension even when their father tried to hide it.

Merina began biting her nails.

Her books clutched tighter.

Selene grew sharper, snapping at classmates, daring anyone to say a word about her family.

Claraara filled page after page with drawings, trucks with faceless men behind the wheel, headlights glowing like eyes, their family home drawn small against the darkness.

Then came the first attack.

It was a school morning.

The girls left the house together, their braids swinging as they walked down the dirt road.

David lingered by the fence, watching them until they disappeared, as he always did.

He had just turned to head inside when he heard it.

Tires screeching, the crunch of gravel, screams.

By the time he reached the end of the road, Clara was on the ground, her satchel flung to the side, pages scattering in the wind.

A truck, white, countyissued, its emblem scraped off but faintly visible, sped away, its engine roaring.

Marina knelt beside her sister, blood staining Clara’s knees where she’d been shoved, her notebook trampled in the dirt.

David’s fury was volcanic.

He gathered Clara in his arms, her silent sobs tearing at him.

“They touched you,” he whispered, his voice trembling.

They put their hands on my miracle.

At the sheriff’s office, he demanded justice.

My daughter was attacked.

She was pushed to the ground.

That truck had your county seal on it.

The sheriff leaned back in his chair, smirking.

Kids rough house.

Maybe she tripped.

And county trucks.

We got dozens.

Hard to tell one from another.

David slammed his fist on the desk.

She cannot even speak.

You think she made this up? But the deputies only laughed.

A mute girl crying wolf.

Come on, Greyhawk.

Don’t waste our time.

David stormed out, his daughters waiting in the truck, watching their father’s hands tremble as he gripped the wheel.

“They won’t protect us,” he said finally.

“So, we protect each other.

” After that, David rarely let the girls out of his sight.

He walked them to school, stood outside during recess, picked them up at the end of the day.

Still, the harassment escalated.

Once they came home to find their porch smeared with red paint, the word silence dripping across the wood.

Another time, their chicken coupe was set ablaze, the smell of charred feathers clinging for days.

At night, headlights sometimes flashed across their windows, lingering before fading into the dark.

Clara’s drawings captured it all.

One sketch showed a truck parked under the cottonwood tree near their home, faceless figures staring out.

Another showed their chicken coupe engulfed in black scribbles of fire.

And one haunting page drawn in heavy pencil showed three small girls holding hands surrounded by tall men with blank faces and no mouths.

Her silence became the family’s evidence.

David kept every page, tucking them into the same folder where he stored contracts and land deeds.

“These drawings will tell the story if I cannot,” he said, his voice low.

Seline, fiery as always, wanted to fight.

She carried her pocketk knife everywhere, daring anyone to try.

Merina tried to mediate, telling her sisters stories to calm them at night.

And Clara, quiet Clara, simply drew, her eyes watching more than anyone realized.

By early 1974, the threats were impossible to ignore.

Neighbors whispered that David had gone too far.

He had uncovered too much about the mining leases, too much about county officials lining their pockets.

Some urged him to leave.

Take your girls, move north.

Forget this fight.

But David shook his head.

If I run, they win.

If I hide, my daughters learn fear.

Number.

We stand.

And so they stood against the letters.

the phone calls, the attacks, against the silence of the sheriff and the smirks of deputies, against the trucks that prowled the dirt roads like wolves circling prey.

On a summer evening, just weeks before their disappearance, the Greyhawks hosted a small dinner.

Friends gathered, sharing fry bread and beans.

Laughter echoed briefly, warm against the looming shadows.

Clara sat at the table sketching the scene.

Her sisters smiling, her father’s face soft.

But in the corner of the page, barely noticeable, she drew the outline of a truck.

Headlights pointed toward the house.

It was as though she already knew.

The Greyhawks were not just a family anymore.

They had become witnesses.

And witnesses in that county did not last long.

The summer of 1974 began with laughter.

For a time, it seemed as if the Greyhawks had carved out a fragile island of peace, even as threats circled like vultures above them.

The triplets had just turned 12.

On their birthday, the little adobe house filled with neighbors who hadn’t yet been scared silent.

Marina read aloud from her new book of Navajo poems.

Seline tried cutting the cake with her father’s pocketk knife, and Clara sketched every detail.

The frosting smudged across Seline’s cheek.

Her father’s tired smile, the candles glowing like tiny suns.

“Your mother would have been proud,” David whispered to them that night, his voice thick with emotion.

“You are her miracles.

Never forget that.

” Yet beneath the joy, tension never left.

The county’s white truck still prowled the dirt road.

Some evenings, headlights flashed across their window, lingering too long.

A black Jeep was spotted more than once, idling near the schoolyard.

Its driver never stepping out, never rolling down the window.

The neighbors whispered, but no one dared act.

David knew the net was tightening.

He had collected more documents, leases signed without consent, records of uranium shipments, health reports of miners poisoned by dust.

At the kitchen table late at night, he spread the papers like puzzle pieces.

Marina helped organize them.

Seline demanded to know the names of the men responsible, and Clara sketched the trucks that stalked their property.

This is the truth, David told them.

If something happens to me, you hold on to this.

It wasn’t only paperwork.

David began carrying a camera, snapping photos of trucks near their land, photographing men unloading barrels into the old mines.

He developed the film in secret, stashing it with Clara’s notebooks inside the leather satchel he had given her.

She guarded it fiercely, sleeping with it beside her pillow.

But even with danger pressing in, life inside the Greyhawk home pulsed with warmth.

On hot afternoons, the girls played in the Aoyo, splashing in shallow water, braids flying as they chased each other.

David watched from the bank, his heart aching with both pride and dread.

At night, they cooked together, frying bread and cast iron, telling stories until lanterns burned low.

Sometimes David would sing old songs, his voice rough but steady, the girl’s harmonies weaving around him.

Neighbors recalled those nights.

You could hear their laughter through the canyon.

One said it was like they were trying to be louder than the silence closing in.

Still, the signs grew harder to ignore.

One evening in July, the family returned home to find their door a jar.

Inside, nothing was stolen, but the papers on the kitchen table had been moved.

Clara’s sketchbook lay open on the floor.

A crude drawing smeared with bootprints.

On the wall above the table, someone had left a message in chalk.

Enough.

David reported it.

The sheriff waved him off.

Maybe your girls left the door open.

When David pressed, the sheriff leaned closer, voice low.

You’re walking a fine line, Greyhawk.

Maybe it’s time to let things go.

David left the office with fists clenched, his daughters silent in the truck beside him.

“They want me quiet,” he muttered.

“But if I go quiet, you’ll inherit a poisoned land.

” Selene spat out the window.

“Then we won’t be quiet either.

” Clara opened her notebook and drew three small figures standing against a wall of faceless men.

She handed it to her father.

He kissed her forehead.

Even your silence speaks louder than their lies.

As July turned to August, David seemed to sense time slipping.

He took the girls on long drives through the desert, pointing out landmarks, teaching them stories of their people.

This mea, he told them once, stood before their minds and will stand after.

Remember that in one of those drives a rancher saw the Greyhawk wagon cresting a hill, dust billowing.

Behind them, two county trucks followed at a distance, engines growling.

The rancher mentioned it later in town.

People only shook their heads.

“Best not to talk about it,” someone whispered.

The final days before the vanishing carried an almost cinematic stillness like the desert itself was holding its breath.

“On the evening of August 2nd, David sat with the girls under the stars.

” “Tomorrow we’ll drive out to the canyon,” he said softly.

“A short trip.

Just us.

Clear our heads.

” Marina smiled, relieved at the thought of escape.

Seline pumped her fist.

Let them follow.

They won’t scare us.

Clara quietly drew a picture of the four of them in their wagon, the moon above, and a black jeep trailing behind.

When the lanterns burned out that night, David lingered at the table, staring at the satchel stuffed with papers and Clara’s notebooks.

He traced his finger over Maria’s rosary, left in a dish by the window.

Then he whispered a promise to the empty room.

I’ll protect them no matter what it takes.

The next afternoon, August 3rd, 1974, the blue Chevy wagon rattled down the canyon road.

Neighbors saw it.

They waved.

The triplets leaned out the windows, hair whipping in the wind.

Behind them, engines hummed.

It was the last time anyone saw them alive.

August 3rd, 1974, dawned with skies so bright and endless they seemed to stretch forever.

A perfect desert day where danger felt impossible.

At the Greyhawk house, the girls buzzed with excitement.

They were heading for a short hike and picnic in the canyons.

Their father promising just us.

No meetings, no arguments, only sky and land.

Marina packed the sandwiches into wax paper.

Seline slung her pocketk knife at her belt, grinning as if daring anyone to ruin their day.

Clara, as always, tucked her leather satchel under her arm, filled with notebooks, pencils, and the small treasures she never left behind.

David checked the station wagon twice, spare tire, canteen, toolkit.

He kissed each daughter’s forehead before loading them in.

Neighbors saw them as they pulled away.

Anna Redbird, the shopkeeper, recalled later.

David smiled and waved.

The girls waved, too.

They looked so alive.

At 4:30 that afternoon, a rancher named Bill Meyers spotted the wagon near the canyon turnoff.

Dust billowed behind it.

He slowed his horse and noticed something unusual.

Two county trucks idling at the far bend of the road.

engines low, their white paint catching the sun.

They waited until David passed,” Meyers said years later.

Then they followed.

Another witness, a teenager fishing near the creek, swore he saw a black jeep lingering a few car lengths behind the wagon.

“The girls were waving out the window,” he said, but the jeep had just crawled behind them slow like a shadow.

By dusk, the Greyhawks had not returned.

Their porch light remained on, the door locked, the girls bikes leaning where they always had.

When David’s cousin reported them missing the next morning, the sheriff’s reaction was chillingly casual.

Greyhawk probably wandered too far.

Might have driven off.

Happens all the time.

But the girls, the cousin began.

The sheriff cut him off.

Look, we’ll put out a notice.

Lost hikers.

End of story.

The search, if it could be called that, was laughable.

Two deputies drove a few miles up the canyon road, stopped at the first ridge, and turned back.

No helicopters, no dogs, no extended patrols.

The official statement released 2 days later read, “Local native family presumed lost during canyon outing.

possible dehydration or misadventure.

Search closed due to lack of evidence, but whispers spread faster than official ink.

Ranchers told of seeing the trucks.

The boy at the creek spoke of the black jeep.

A prospector swore he heard shouting near the abandoned minehafts that night, followed by the echo of engines and then silence.

Back at the Greyhawk home, the absence was unbearable.

On the kitchen table sat Clara’s last open notebook.

The page showed their blue station wagon drawn in sharp lines, dust clouds rising behind it.

Behind the car were two blocky shapes, trucks, and in the corner a darker sketch, a yawning black hole in the earth like the mouth of a mine.

Above it, faceless men loomed, their heads sketched as blank ovals, eyes missing.

It was her last testimony left behind in pencil strokes.

For Anna Redbird, the meaning was clear.

She was telling us, she whispered, clutching the drawing.

They were taken.

They didn’t just vanish, but when Anna carried the sketch to the sheriff’s office, he scoffed.

A child’s doodle, nothing more.

He shoved it back across the desk.

This case is closed.

Don’t stir trouble.

Within a week, the Greyhawks were declared presumed deceased.

The county issued a prefuncter statement of sympathy.

Nothing more.

No funerals, no graves, only silence.

Yet in the community, grief simmerred like a storm.

Mothers clutched their children tighter.

Fathers looked over their shoulders when county trucks passed.

At vigils, elders lit candles at the canyon trail head, whispering the names David, Marina, Selene, Clara, and always Clara’s notebook passed quietly from hand to hand, its sketches studied like holy scripture.

She couldn’t speak, one neighbor said.

So, she drew the truth.

And the truth was they were followed.

The Greyhawks had not just disappeared.

They had been erased, and the earth itself seemed to swallow them whole.

For 30 years, no answers came, only whispers, only shadows.

Until one day, the land gave them back.

The Greyhawk’s disappearance rippled through the reservation like a stone dropped into still water, the shock waves spreading far and wide.

At first, grief was raw.

Neighbors gathered at the canyon trail head with candles.

their flames flickering against the desert wind.

Elders burned sage and prayed aloud for the four lost souls.

Mothers whispered to their children, “Stay close.

Don’t wander.

” Fathers locked their doors earlier, eyes sharp whenever county trucks rolled by, but soon silence began to settle.

The sheriff’s office declared the case closed.

The newspapers ran a short article.

family presumed lost in canyon.

A few paragraphs, a small photo of the blue Chevy wagon, and then nothing more.

No follow-ups, no investigations.

The official story was sealed.

They were simply gone.

For some, silence was safer than questions.

Jobs depended on county contracts.

Families feared retaliation.

To speak too loudly about the Greyhawks was to invite the same fate.

Don’t stir trouble, people whispered.

Don’t bring the trucks to your door.

But not everyone was silent.

At the center stood Anna Redbird, the shopkeeper who had seen David wave goodbye that last afternoon.

She lit a candle at the canyon every week, sometimes standing alone with the flame trembling in her hand.

“I will not let them vanish twice,” she said.

Anna collected testimonies.

She wrote down the rancher’s account of the trucks, the teenager’s memory of the black jeep, the prospector’s story of shouts near the mine.

She carried Clara’s last drawing folded in her purse, its pencil lines fading at the edges, but still clear.

A wagon, trucks, faceless men, a black pit.

At council meetings, Anna rose and demanded answers.

Where is the search? Where are the records? Why do trucks with county plates follow children into canyons? Officials shifted uncomfortably, murmuring excuses.

Some outright mocked her.

A grieving woman chasing ghosts, one said, but others listened quietly.

In whispers at the trading post, people shared fragments.

A man said he saw deputies near the old mine the night of the disappearance.

Another swore he spotted county trucks parked outside the sheriff’s station long after dark.

A minor admitted, voice trembling, “There are shafts down there, deep ones.

You could hide anything.

” Still, fear kept most mouths shut.

A teacher who spoke up about the Greyhawk’s case found her car vandalized.

The word quiet scratched into the hood.

A rancher who mentioned trucks at a bar was beaten in an alley that same night.

One by one, witnesses fell silent.

Through it all, Anna pressed on.

She plastered posters across town.

Where are the Greyhawks? She organized vigils, sometimes drawing dozens, sometimes only herself.

She wrote letters to state officials, to senators, to newspapers beyond the county line.

Few replies ever came.

The ones that did were polite dismissals.

Regrettable tragedy, but no evidence of foul play.

David’s surviving relatives fought, too.

His cousin visited the sheriff’s office monthly, demanding files.

Each time, deputy shrugged.

nothing to give you.

Cases closed.

When he pressed harder, they told him, “Stop looking or you’ll end up the same way.

” Meanwhile, the land around the abandoned mine remained off limits.

Signs warned trespassers to stay away.

County trucks patrolled the road, their engines humming like a threat.

Hunters who wandered too close swore they were followed back out, headlights in their mirrors until they reached the highway.

By the late 1970s, the Greyhawks had become legend.

Children whispered their names at night, daring each other to walk near the canyon.

Some said their ghosts haunted the old mine, their voices echoing through tunnels.

Elders shook their heads at such stories, but their eyes carried sorrow.

“They are not ghosts,” one said.

“They are evidence.

” Clara’s drawings became relics.

Anna guarded them like scripture, showing them at vigils.

This was her voice, she would tell the gathered.

She could not speak, so she drew.

And this is what she told us.

They were taken.

The sketches passed from hand to hand, each person tracing the pencil lines of trucks, faceless men, and the black pit.

But still, the officials dismissed it.

The sheriff repeated the same line.

lost hikers.

Case closed.

Deputies smirked.

The county trucks continued to prowl.

And yet, the memory of the Greyhawks refused to die.

Every August, on the anniversary of their vanishing, candles flickered again at the canyon trail head.

Sometimes dozens gathered.

Sometimes only Anna.

Always the names were spoken aloud.

David, Marina, Selene, Clara.

By the 1980s, the Greyhawk story was more than tragedy.

It was warning.

It was proof of what could happen when you raised your voice against power.

It was the whispered reason parents gave their children when they told them not to talk back to deputies, not to ask about the mines, not to wander alone at night.

The Greyhawks had vanished, yes, but they were not forgotten.

And though the sheriff declared their case closed, the land itself had not closed it.

The abandoned mine shafts remained, silent and waiting.

And one day, decades later, the land would finally give up its secret.

Time, they say, can dull grief.

But for those who loved the Greyhawks, time did not dull.

It calcified.

By the mid 1980s, 10 years after the disappearance, most of the community had stopped speaking of it aloud.

But silence did not mean forgetting.

At the trading post, elders still shook their heads whenever county trucks rumbled by, muttering, like the ones that followed David.

At school, children dared each other to whisper the names of the triplets in the hallways.

Say Marina, Selena, Clara three times, they teased.

The mine will swallow you too.

Their voices carried the legend.

But under the childish games was a current of fear.

For Anna Redbird, silence was never an option.

Every August on the anniversary of the vanishing, she walked to the canyon trail head with a single candle.

Some years 10 or 20 people joined her.

Some years only one or two, but she never missed.

“They are still here,” she would whisper as she lit the flame.

“We wait for them.

” In her shop, tucked behind jars of flour and beans, Anna kept a box labeled Greyhawk.

Inside were scraps of testimony she had collected, notes about trucks seen that night, fragments of overheard conversations, copies of the sheriff’s dismissive reports, and most sacred of all, Clara’s notebooks.

The pencil lines had smudged over the years, but the message remained.

The wagon, the trucks, the faceless men, the black pit of the mine.

Every few years, Anna sent the drawings to journalists outside the county.

Most never replied.

A few wrote back politely, saying the case was tragic, but lacked evidence.

One reporter visited briefly in 1989, promised a story, and then vanished from contact after a closed- dooror meeting with county officials.

By the 1990s, even whispers had thinned.

New generations grew up knowing the Greyhawks only as a story their parents told.

Half warning, half myth.

But the old mine shafts still loomed.

Boards nailed across entrances, warning signs posted, barbed wires strung, county trucks occasionally parked there, engines running.

Hunters who wandered too close swore they heard sounds from underground.

Chains rattling, a car door slamming, the echo of voices.

They fled and never returned.

To Anna, the mine was a wound in the earth, bleeding secrets no one wanted to face.

“That’s where they are,” she told anyone who would listen.

“I feel it.

” They didn’t just vanish into thin air.

The ground swallowed them.

But when she demanded action at council meetings, she was met with weary looks.

It has been too long, officials said.

There is nothing to find.

One even sneered.

Maybe you enjoy the attention.

By 2000, Anna was an old woman, her hair silver, her hands trembling from arthritis.

Still, she carried Clara’s notebook everywhere, folded in a worn satchel.

At vigils, she would hold it up like scripture.

This was her voice, she told younger generations.

She spoke without words.

Don’t let them erase her.

For David’s surviving relatives, the years were no kinder.

His cousin stopped asking for files after his tires were slashed and his windows broken twice.

Another family member who pressed for answers lost his job with the county contractor.

The Greyhawks died once in 1974, one bitterly said.

The county killed them again every time they silenced us.

The abandoned mine remained untouched.

Dust storms covered its entrances, rattling the warning signs.

Birds nested in the rafters of the old shafts.

The air grew heavy there, as if the earth itself knew what lay beneath.

Then in 2003, the land stirred.

That summer, violent storms swept across the desert.

Rain pounding in sheets, winds tearing across the maces.

Flash floods carved new channels through Aoyos, and one night, lightning struck near the old mine.

Locals said the ground shook as if the earth itself groaned.

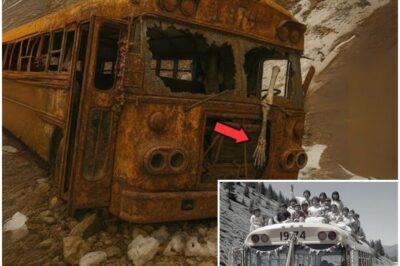

A year later, in early 2004, hikers exploring after the storms noticed something strange.

Part of the hillside near the abandoned shaft had collapsed, revealing rusted metal glinting under the mud.

At first, they thought it was scrap, but as the soil shifted, they realized it was the corner of a car roof.

Word spread fast.

County workers were sent to investigate.

They dug carefully, pulling back layers of dirt, stone, and collapsed timbers.

As more of the vehicle emerged, blue paint flaked under the sun.

A crushed license plate came into view, numbers still faintly legible.

It was a 1966 Chevy station wagon, the same one that had vanished 30 years before.

The same one witnesses had seen followed into the canyon.

The same one Clara had drawn over and over in her notebook.

For three decades, silence had rained.

But now, the earth itself had spoken.

The morning the past came, clawing back began like any other.

County workers had been dispatched after hikers reported strange debris at the edge of the old minehaft where storms had torn away the hillside.

For years, the shaft had been sealed, boarded up with rusted signs that read, “No trespassing, dangerous collapse.

” But the floodwaters had shifted the earth, prying open secrets no one had meant to release.

As the workers cleared mud and splintered timbers, something metallic emerged.

At first, it was only a corner, a curve of blue beneath layers of brown clay.

They thought it might be a barrel, maybe old mining scrap.

But the more they dug, the clearer it became.

A roof, a windshield frame, the unmistakable outline of a car.

By noon, a crane was called in.

Slowly, inch by inch, the vehicle was lifted free from its muddy tomb.

As sunlight hit its surface, flakes of sky blue paint shimmerred, battered, but defiant.

The workers stepped back in silence.

They knew this car.

Everyone in the county knew this car.

It was the Greyhawks 1966 Chevy station wagon.

Word spread like wildfire.

By afternoon, a crowd had gathered behind barricades.

Elders, children, neighbors, even those who had long claimed the Greyhawks were just lost hikers.

Anna Redbird stood at the front, her hands trembling against her cane.

She had waited 30 years for this.

Tears welled as she whispered the land remembered.

Authorities moved quickly to control the scene.

Deputies barked at onlookers, ordering them back.

But whispers rippled through the crowd.

It’s them.

They found them.

When investigators finally opened the vehicle, the truth was revealed in silence.

more deafening than any storm.

Inside, slumped across the wheel, lay the skeleton of David Greyhawk, his wrists still bound to the steering column with rusted wire.

Behind him in the back seat, two smaller skeletons sat pressed together, their bones curled as though they had clung to one another until the end, Marina and Seline.

And in the passenger seat, strapped in by a decayed seat belt, was the smallest form of all.

Clara, her leather satchel still rested against her rib cage.

Inside it, remarkably preserved by the dry air and the sealed interior, was her final notebook.

The sight broke the crowd.

Some wept openly, others turned away, unable to bear it.

Anna Redbird collapsed to her knees, clutching her chest.

whispering the girl’s names like a prayer.

The sheriff’s department tried to move quickly, wrapping the scene in sterile words.

Tragic accident.

Family drove into unstable mine.

But no one who stood there believed it.

Not when David’s wrists were bound.

Not when Clara’s notebook told another story.

Forensic teams began their work.

Bones were carefully removed, tagged, and carried away.

But rumors spread faster than official reports.

A deputy’s voice was overheard.

This wasn’t no accident.

They were put here.

When Clara’s notebook was finally opened, it sent shivers through everyone who saw it.

The last pages drawn in shaky pencil showed the same images she had sketched for years.

The blue wagon, the faceless men, the county trucks, the gaping black pit of the mine.

On the final page, a haunting image.

Four small figures inside the wagon.

Wire binding their arms.

Faceless men standing over them.

She knew.

Anna whispered when shown the drawings.

She told us.

She told us 30 years ago.

We just didn’t listen.

Media from outside the county descended.

Cameras flashing.

Headlines screaming.

vanished native family found in mine after three decades.

For the first time, the Greyhawk’s names spread beyond the reservation.

For the first time, the official story of lost hikers was openly questioned, but the sheriff still clung to denial.

At a press conference, he insisted, “Evidence points to a tragic accident.

Abandoned mines are dangerous.

They must have driven in and collapsed inside reporters pressed about David’s bound wrists.

The sheriff stammered, then claimed, “Rust and debris can cause misleading impressions.

” The crowd didn’t buy it.

Not when Clara’s notebook existed.

Not when witnesses still remembered trucks following the family into the canyon.

Not when Anna had screamed the truth for 30 years.

The discovery cracked open.

Not just the mine, but the entire county’s facade.

Old whispers surged into the open.

People who had been silent for decades began to speak.

A retired minor admitted seeing county trucks dumping barrels into the shaft the same week the family vanished.

A former deputy confessed anonymously that he was told never to ask about the Greyhawks again.

For 30 years, silence had buried them.

Now silence was breaking.

The station wagon had been their tomb.

But Clara’s notebook pressed against her ribs was their voice.

And that voice was louder in death than it had ever been in life.

The Greyhawk station wagon, once a familiar sight rattling down reservation roads, now sat under glaring flood lights at the county impound lot.

Reporters pressed against the barricades, cameras snapping at every angle.

Forensic experts moved carefully, their gloved hands cataloging bones and rusted wire, photographing every inch of the vehicle before dismantling it piece by piece.

The findings came quickly, and they shattered the sheriff’s tragic accident narrative.

David Greyhawk’s skeleton bore clear signs of blunt force trauma to the skull.

a fracture that could not be explained by a car crash.

His wrists, still encircled with rusted wire, showed grooves etched into the bone, proof he had been bound before death.

The two girls in the back seat, Marina and Selena, showed no evidence of seat belts.

Their position suggested they had been forced down as if held captive until the mine swallowed them.

And Clara, the mute sister, had remained seat belted in the passenger seat.

Her satchel clutched so tightly that her tiny finger bones had fused around the strap with decay.

Inside the satchel, her final notebook was treated like sacred scripture.

Forensic archivists carefully separated each page.

The drawings preserved by the sealed aid environment of the mine were hauntingly clear.

One page showed the blue wagon with headlights blazing behind it.

Another depicted trucks with county insignas scratched out.

The final page, the one that made headlines, showed four stick-like figures inside the car with thick black lines binding their arms.

Above them loomed tall faceless men drawn with blank ovals for heads.

In the corner, Clara had scrolled one final detail.

The outline of a mineshaft.

Jagged with dark scribbles swallowing the wagon hole.

She could not speak, Anna Redbird told a TV reporter, tears running down her face as she held the notebook, so she drew the truth.

And 30 years later, the truth is louder than any sheriff’s lie.

The sheriff, red-faced, doubled down.

At a press conference, he repeated, “This was a tragic accident.

Families should stay away from abandoned mines.

We found no conclusive evidence of foul play.

But when reporters pressed about David’s bound wrists, his skull fracture, and Clara’s notebook, he shifted in his seat, muttered about debris and misinterpretations, then stormed off the stage.

National media swarmed in.

For the first time, the Greyhawk story stretched beyond reservation borders.

Headlines blared.

Vanished native family found after 30 years.

Evidence of cover up alleged.

Mute girls notebook speaks from the grave.

Sheriff denies foul play despite shackled skeletons.

Talk shows debated it.

Journalists flew in.

Families of other missing native activists began contacting Anna, sharing stories eerily similar.

Land disputes, sudden disappearances, closed cases.

The pressure mounted.

Community members, once silent, began to speak out.

A retired minor admitted under anonymity that he had seen county trucks hauling barrels and a car-shaped object toward the shaft the week the Greyhawks vanished.

Another former deputy confessed he was told by superiors to forget the Greyhawks or risk losing his job.

A teacher recalled being warned not to let her students talk about Clara’s drawings.

Forensics experts openly contradicted the sheriff.

Dr.

Helen Morris, a forensic anthropologist, told reporters, “This was no accident.

the fractures, the bindings, the positions of the skeletons.

This was deliberate placement.

They were murdered.

The county tried to quiet the outrage, calling it media hysteria, but the evidence was undeniable, and the notebook became the beating heart of the story.

National outlets published its images.

Millions of readers staring at Clara’s crude pencil lines, a mute child’s last testimony against faceless men.

The truth survived in her silence.

One commentator wrote, “They cut her voice, but not her will.

” For the Navajo community, the discovery reignited pain and anger.

Vigils swelled in size.

Hundreds gathered at the canyon holding candles, chanting the Greyhawks names.

Elders prayed aloud.

Children left drawings of their own at the mine’s edge, mimicking Clara’s style.

Trucks, faceless men, dark pits.

But for Eliza Be Gay, David’s surviving sister, the moment was bittersweet.

Standing before reporters, she clutched Clara’s notebook and whispered, “They killed my brother.

They killed my nieces.

And for 30 years, they told us it was our imagination.

This was not an accident.

This was a message.

They wanted us silent.

But here we are, louder than ever.

Investigative journalists began uncovering connections between the sheriff’s office, the mining company, and county commissioners.

Land deeds signed in 1974 matched the period of the Greyhawks disappearance.

Some officials had grown rich off contracts to clear land deemed unsafe.

Land once belonging to families like the Greyhawks.

The narrative shifted from lost hikers to systemic silencing.

The Greyhawks were no longer just victims.

They were proof of a broader pattern.

The buried evidence of a conspiracy spanning decades.

By the end of 2005, the countyy’s sheriff quietly retired.

No charges were ever filed.

Officials spoke vaguely about insufficient evidence for prosecution.

But the community had no doubt.

They knew who had bound David’s wrists.

They knew who had shoved Marina and Seline into the back seat.

They knew who had left Clara’s silence to speak louder than their lies.

And they knew why.

Because the Greyhawks had stood against Power.

and for that power had buried them.

The Greyhawks did not return as they had left.

30 years had passed since the blue Chevy station wagon rattled down the canyon road, the triplets waving out the windows, their fathers smiling faintly at the wheel.

Now what returned were bones, notebooks, and a truth so raw that it silenced even those who had once mocked.

Their remains were carried home in cedar caskets draped with blankets handwoven by elders.

Hundreds gathered for the funeral, more than had ever attended a service in that small town.

Elders led prayers in Navajo, their voices rising and falling like the wind through the meases.

Children clutched candles, watching as the four coffins were lowered into the tribal cemetery side by side.

David’s casket lay at the center.

To his right, Marina and Seline.

To his left, Clara, her satchel buried with her.

Notebook returned to her chest.

She carried our voice.

Anna Redbird whispered, placing a white feather on Clara’s coffin.

“Let her rest with it.

” As the coffins were covered, Eliza Beay, David’s sister, stepped forward.

Her voice cracked as she spoke.

They cut my brother’s life.

They cut my niece’s childhood.

They thought silence would erase them.

But silence did not erase.

Silence became their weapon.

Clara’s silence spoke louder than their lies.

Marina’s gentleness, Seline’s fire, David’s courage, none of it died.

It lives in us.

Tears streamed down faces hardened by decades of injustice.

Men who had once remained silent wept openly.

Women clutch their children, whispering the Greyhawk’s names as blessings.

Elders closed their eyes, whispering prayers to the land itself.

Hold them gently.

You remembered them.

Remember us all.

After the funeral, a vigil was held at the canyon trail head.

Hundreds walked to the same road where the station wagon had last been seen.

They placed stones carved with initials DG, MG, SG, CG at the base of the sign that still warned, “Danger, abandoned mines.

It became a ritual.

Each year after, hikers passing through left tokens, stones, feathers, scraps of cloth.

The canyon road grew into a memorial, silent, but defiant.

Travelers said you could feel something there.

Not ghosts, but presents.

A weight in the air that whispered, “We were here.

” Clara’s drawings became symbols beyond the reservation.

Copies were carried at protests, held high on signs, crude sketches of trucks, faceless men, the blue wagon swallowed by darkness.

For native activists fighting for land and justice, they became rallying cries.

They silenced her voice, one activist said, but they did not silence her truth.

Journalists continued to write about the case, calling it one of the clearest examples of systemic cover up.

Documentaries aired.

Students studied it in classes about injustice and eraser.

The Greyhawks, once dismissed as lost hikers, became known across the country as proof of what silence tried to bury.

But for the community, the legacy was deeper, quieter.

Parents told their children about the Greyhawks, not to frighten them, but to remind them.

They stood, they said, even when it cost them everything.

And because they stood, we remember Anna Redbird lived long enough to see the funeral.

At the vigil, she clutched Clara’s notebook, now preserved in archival plastic, and whispered, “I kept your voice safe, little one.

The world hears you now.

” She died a year later, buried beside her own parents.

The notebook donated to a tribal museum where it rests under glass, open to the final page.

Visitors stand before it, silent, staring at the childlike lines.

The wagon, the trucks, the faceless men, the mine, four small figures inside.

It is crude, almost simple, and yet it screams louder than words ever could.

In the years that followed, the mine was finally sealed.

Its entrances collapsed, warning signs replaced with memorial plaques.

But still, some said the land hummed there at night as though remembering.

The Greyhawks had been buried twice, once in a mine by men who wanted silence, and again by decades of denial.

But in the end, silence did not win.

The truth clawed its way out, carried in Clara’s pencil lines, in Anna’s candles, in the voices of those who refused to forget.

As one elder said at the final vigil, “They cut tongues, they cut lies, but the truth cannot be cut.

The truth survives.

” And so the Greyhawks survived.

Not in flesh, not in breath, but in memory, in stone, in ink, in silence that spoke louder than words.

They became more than victims.

They became a warning, a legacy, a promise.

Every August, as the sun dips behind the maces and candles flicker at the canyon trail head, their names are whispered into the wind.

David, Marina, Selene, Clara.

Four voices, four lives, four truths.

No longer vanished, no longer erased, remembered forever.

News

Native Family Vanished in 1963 — 39 Years Later A Construction Crew Dug Up A Rusted Oil Drum…

In the summer of 1963, a native family of five climbed into their Chevy sedan on a warm evening in…

An Entire Native Wedding Party Bus Vanished in 1974 — 28 Years Later Hikers Found This In a Revine…

An Entire Native Wedding Party Bus Vanished in 1974 — 28 Years Later Hikers Found This In a Revine… For…

5 Native Brothers Vanished in 1962 — 48 Years Later, Their Wagon Was Found in a Frozen River…

5 Native Brothers Vanished in 1962 — 48 Years Later, Their Wagon Was Found in a Frozen River… The winter…

Three Native Elders Vanished During a Winter Hunt in 1956 — 65 Years Later, a Drone Found This…

Three Native Elders Vanished During a Winter Hunt in 1956 — 65 Years Later, a Drone Found This… In the…

A Native Family Vanished in 1972 — 22 Years Later This Was Found Hanging In An Abandoned Mansion…

In the summer of 1972, a native mother and her two young children vanished from their small farmhouse in northern…

Native Activist Vanished in 1987 — 18 Years Later Workers Found This Shackled in a Tunnel….

Native Activist Vanished in 1987 — 18 Years Later Workers Found This Shackled in a Tunnel…. South Dakota, 1987. The…

End of content

No more pages to load