They vanished in the summer of 2009 without warning, without witnesses, and without leaving behind anything but silence.

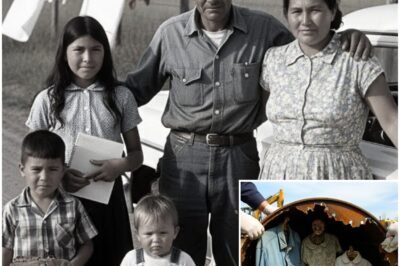

One moment they were there sharing a final photo from the red rock heart of the Navajo back country.

The next they were gone, swallowed whole by the desert.

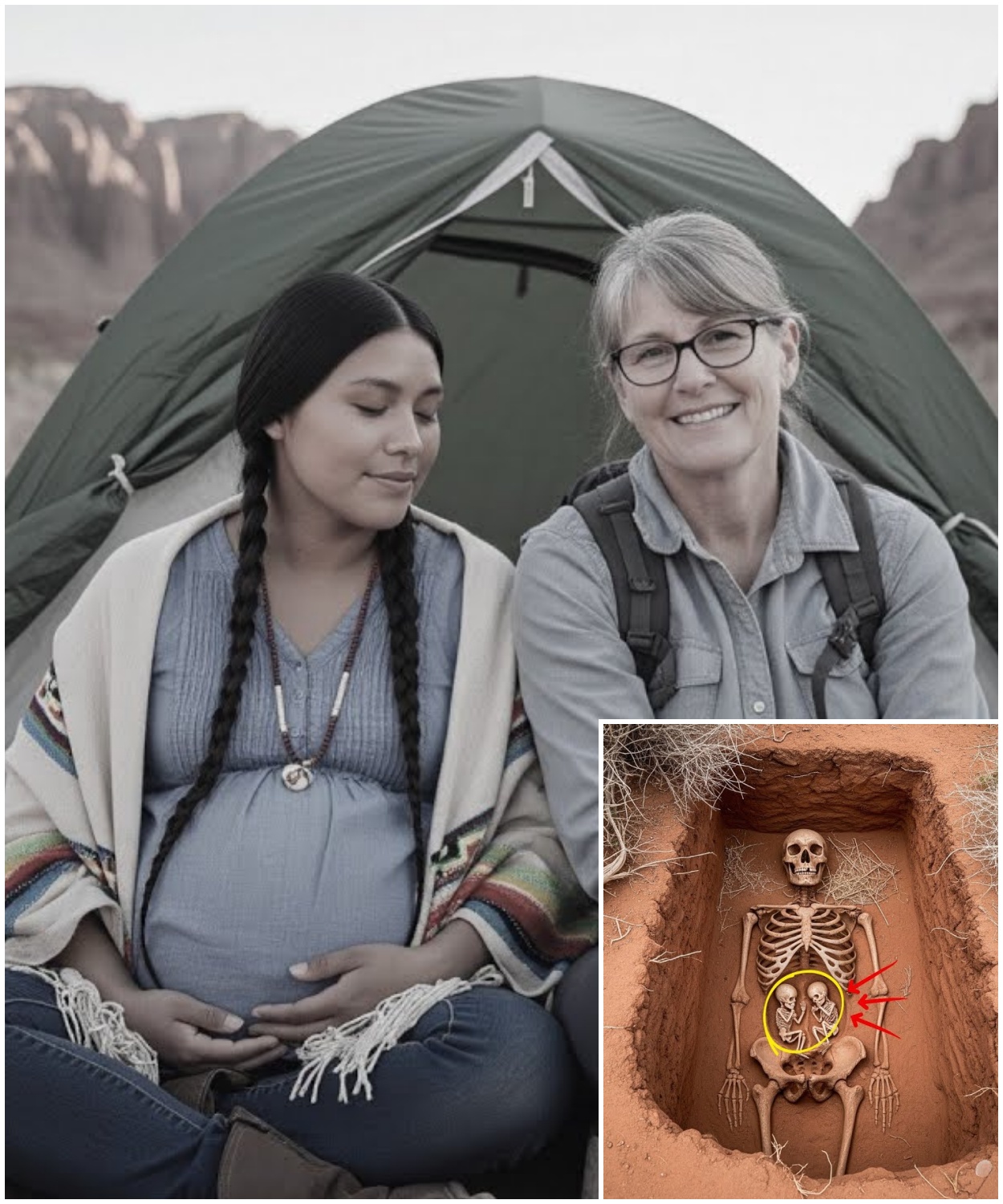

For 12 years, no one knew what happened to 31-year-old native woman Alana Skywater.

Eight months pregnant with twins or to her 60-year-old adoptive mother, Evelyn Reed.

The high desert forgot nothing, but it held its secrets close.

And when they finally came undone, it wasn’t with answers.

It was with bones.

They had driven out on June 21st, 2009, a Sunday, the day of the summer solstice.

Alana had always said she felt strongest when the sun was high.

It marked the midpoint of her pregnancy and her people’s ceremonial calendar.

The van they took, a retrofitted white Ford Econoline, had belonged to Evelyn since her teaching days in Shiprock.

She and Alana had recently modified it into a spiritual camper.

Handp painted panels, medicine shelves, a star map across the ceiling that glowed at night.

They left no specific itinerary, but Alana had messaged her cousin Nita a few days earlier.

Headed back into ceremony, the message read, “Remote camp, ancestral route.

No signal expected.

We’ll uplink when we settle.

” That last uplink came at 6:42 p.m.on June 23rd.

A satellite image, low resolution, but full of light.

Alana sitting cross-legged in front of a sandstone bluff.

her swollen belly framed by a painted sash bearing the twin glyph.

Behind her stood Evelyn, one hand resting on her shoulder, the other shading her eyes from the dying sun.

They looked peaceful, rooted, sacred.

The caption sent later said only, “The land remembers.

We’re exactly where we’re meant to be.

” And then silence.

Nita didn’t worry at first.

Signal blackouts were common across the northern rim, especially near the sacred ridges where Alana insisted on going.

But when two days passed and neither woman reappeared in Shiprock or Gallup, and neither responded to messages, Nidita began calling around.

First local rangers, then tribal police, then county dispatch.

She told them who was missing.

She gave them the last photo.

She begged them to look.

By the time a search team reached the site, four days had passed.

The camp was there, tucked beneath a natural rock overhang in a dry aoyo, just off an unmaintained Bureau of Indian Affairs road.

The van was parked in the shade.

The fire pit was untouched.

Two chairs sat facing the stone bluff.

Inside the tent were two neatly laidout sleeping bags and a handwoven cradle board, half-finish.

Inside the van, everything was intact.

Evelyn’s purse, Alana’s journal, a bottle of prenatal vitamins, a ceramic bowl of burned cedar.

Their emergency Starlink satellite box sat powered down on a shelf.

Nothing was missing.

Nothing was packed.

It was like they had stepped outside and never come back.

The investigation began slowly, then turned cold faster than it should have.

Tribal authorities coordinated with San Juan County, but jurisdictional boundaries blurred.

And once a gas station attendant claimed to have seen Evelyn alone 2 days later buying water and a paper road atlas in Tuba City, the entire tone shifted.

The official theory, Evelyn had snapped, that the stress of caring for her pregnant daughter had pushed her into a fugue state, or worse, that she had harmed Alana and fled.

The case pivoted around that possibility.

Her age, her whiteness, her role as a non-native in sovereign territory.

The narrative was easy to shape.

Tragedy by burden.

But Nita refused to believe it.

She’d grown up with both women.

Knew Evelyn as kind, sharp, unshakably maternal.

Knew Alana as defiant but thoughtful, half wild with spirit, but always grounded in ritual.

They had just finished making the moon cradle.

Alana had picked names for the twins, Tally and Naelli.

She had planned a naming ceremony after their birth.

She was going to raise them near Blue Canyon, where the sandstone metwater.

She was nesting, not running.

Still, the media picked up only the simplest version.

White mother, native daughter, spiritual trip, remote camp, and then nothing.

No bodies, no blood, just a van in the desert and a missing pregnant woman.

Her name joined lists that were far too long.

Missing and murdered indigenous women.

Another ghost in the Red Rock.

12 years passed.

Nita never let go.

She kept the case alive with annual memorials, social media posts, visits to agencies.

Her tone grew harder with time.

She no longer pleaded.

She demanded.

She pointed to federal neglect, to the broken trail of dozens of similar cases.

She said Evelyn had been watching Alana not hurting her, that Evelyn had written land use complaints to tribal council before they left, that she had something to prove or maybe to protect.

By 2021, the case file sat in a dusty drawer in a half-funded basement office in Farmington.

No new tips, no new searches, just a long, slow ache.

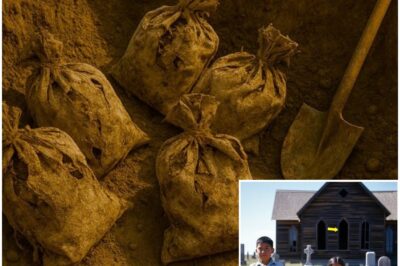

And then by sheer accident, the land cracked open.

August 14th, 2021.

A heat wave had rolled through the high meases.

A conservationist named Cole Mercer was hiking alone, scouting wild sage bloom clusters for a botany project.

He’d veered off the ridge to relieve himself near a crumbling ledge half a mile east of where Alana’s van had been found in 2009.

That’s when he saw it.

Just beneath the edge of a collapsed crevice caught in a slant of sunlight was a patch of soil discolored from the rest.

It had collapsed partially inward, exposing a pale curved fragment beneath.

At first he thought it was animal bone, but the shape was too symmetrical, the ridge too smooth.

He crouched, used a stick to lift the edge, a rib cage, small human.

His breath caught.

He stepped back, trembling.

Then he saw another, another rib arc, another tiny shape, barely fused limb bones pressed together as if sleeping.

Twins, not just children, fetal.

His phone struggled for signal.

He managed a ping to Navajo Ranger Station 7, gave rough coordinates, and waited.

He didn’t move.

He couldn’t.

3 hours later, the site was roped off.

Forensic specialists arrived at dawn.

What they unearthed over the next 24 hours made headlines across the four corners.

A single adult female skeleton seated upright in the earth, knees pulled to chest, curved like a cradle, arms folded inward, protective.

Within her pelvic basin, nestled between the wings of bone were two tiny skeletal forms.

Their limbs overlapped, their skulls, partially preserved, faced each other, identical.

DNA would later confirm the adult was Alana Skywater.

The fetal remains were hers.

Twin daughters, but there was no sign of Evelyn.

No other bones, no blood, no clothes, no prints, no trace.

Just a shallow grave cut into sacred ground and the mother who held her daughters through death.

The discovery sent a shock wave through the law enforcement community.

The case, once considered a confused wandering or a fugitive escape, was immediately reclassified.

Not missing, not delusional.

Homicide.

Nidita sat alone on the floor of her trailer the night she got the call.

She didn’t cry.

She didn’t speak.

She looked at the old printed photo on her fridge, the one Alana had sent her 12 years before, and then she opened Evelyn’s last letter, one she had never dared read until now.

And for the first time, she understood what they had walked into and why they hadn’t walked back out.

The letter had arrived 2 weeks after their disappearance.

A handwritten envelope, faded blue ink, postmarked from shiprock.

Nidita had tucked it into a drawer without opening it, too shaken by their vanishing, too full of prayers and dread.

At the time, she believed they were still out there, maybe hiding, maybe stuck, maybe waiting to come home.

Reading the letter then would have made it feel final, like they weren’t coming back.

But now, 12 years later, with Alana and the twins found buried beneath a red dirt overhang, her bones curled like a question no one could answer.

Nidita sat on the floor, peeled the seal open, and read.

Nidita, if you’re holding this, it means we didn’t make it back.

I don’t want that to be true, but I know what we’re walking toward.

It’s bigger than us.

Bigger than even Alana understands.

You know her heart.

You know how the land calls her.

That’s not spiritual poetry.

It’s real.

She hears things, sees them sometimes.

But this isn’t just ceremony or instinct.

It’s danger.

The kind that buries its teeth underground.

I need you to promise something.

If we vanish, don’t let them say we wandered off.

We didn’t.

Not by accident.

Not by mistake.

Look at the maps.

Look at what Alana found.

You know the ridge.

You know what they were doing out there before the park lines were drawn, before the signs went up.

Some secrets weren’t lost.

They were buried.

And they don’t like being uncovered.

There was no signature, just a single line scratched in the bottom margin, the ink darker there as if pressed with more weight.

Start with the black vein.

Nidita sat for a long time after reading, hand slack in her lap.

She didn’t sleep, didn’t speak.

She waited for the sun to rise, then made a call, the first of many.

The reopened case spun into motion like a wheel finally breaking free from the sand.

Investigators assembled a new task force, tribal police, BIA liaison, one senior cold case detective from San Juan County named Rios, who remembered the original file like a bad tooth that had never been pulled.

First, they exumed the evidence from 2009, the van, the site photos, Evelyn’s journal, then the maps.

They were the same ones Nidita had seen briefly in the original report.

Handdrawn overlays of tribal topography annotated with codes that looked geological.

She’d thought little of them at the time, just notes for the trail.

But now, viewed under a different lens, with Evelyn’s letter echoing in her head, they took on a new weight.

One map in particular had a section boxed in red ink with a tiny X marked SVN8.

Nearby, a note, pegmatite band, shallow vein.

Test results inconclusive.

An old professor from the University of New Mexico’s Earth Sciences Department was brought in to interpret.

His conclusion was swift and alarming.

“These aren’t hiking maps,” he said, tapping a pencil against the notations.

“This is mineral surveying, amateur, but competent.

Whoever did this was prospecting.

” Pegmatite is host rock for rare earths.

And this notation, black vein, likely refers to a thorite deposit, radioactive, illegal to mine without a permit, especially on native land.

That word again, thorite.

It wasn’t the first time investigators had heard it.

The forensic report from the recent excavation, the one detailing the microparticles found embedded in Alana’s neck vertebrae, had identified the dust as thorite residue, highly compressed, dense, and unnatural in its environment.

It wasn’t windblown or washed in.

It had been transferred, likely through direct contact.

Now, the map provided something else.

Location.

The burial site where Alana and her unborn twins were found was just 600 yardds from the vein marked SVN8, which meant whoever killed her had known that land well enough to both hide a body and avoid discovery for 12 years.

It also meant Evelyn hadn’t gone mad.

She’d gone digging.

The task force brought Nita in to verify names from Evelyn’s past, contacts, old friends, business partners.

She gave them the name instantly.

Lyall Croft, she said, used to run a sustainability nonprofit with Evelyn, folded around 2006.

He handled land grants.

She handled research.

After that, he just disappeared.

The name triggered a hit in the old case notes buried in an interview from 2009.

Croft had given a vague, half-hearted statement, claimed to be shocked by the disappearance, told officers he hadn’t spoken to Evelyn in years, that they parted ways professionally, that she had become obsessed with the land.

But what stood out now with hindsight was the choice of words, obsessed, and land.

Rios ordered a financial background run.

The results opened the story like a fresh wound.

Between 2006 and 2009, Lyall Croft had filed multiple shell companies across Utah and Colorado under environmental impact consulting aliases.

All of them operated near native land.

All of them had quiet investors, and all of them dissolved mysteriously just before state or federal reviews.

Buried in the filings were two asset reports that referenced mineral samples collected in unregistered extraction zones.

One was dated May 2009, 3 weeks before Alana and Evelyn vanished.

That was enough.

A warrant was issued to search Croft’s last known property, a solar homestead in rural southern Utah.

What they found was meticulous.

A small geocchemical lab, sealed cabinets, survey maps printed on miler, dozens of soil sample vials, and locked in a drawer, a pair of redback geological boots with thorite dust compacted in the treads.

It was all circumstantial, but it was heavy.

They brought Croft in under the guise of a land dispute inquiry.

He was older now, thinner, wore a vest with hemp buttons, and drank from a branded permaculture or parish water bottle.

He smiled politely, answered questions with long, thoughtful pauses.

When they finally showed him the photos of the burial site of the skeletal twins, his mouth twitched just slightly.

“We’re just trying to understand why Evelyn would have taken her daughter out there,” Rio said softly.

She told someone she thought they were in danger, that someone didn’t want a certain discovery exposed.

Croft exhaled through his nose.

His smile didn’t fade, but his eyes shifted down.

“I always thought she was brave,” he murmured, even when she didn’t understand the risk.

Rios’s hand twitched over the recorder.

“What risk?” Croft said nothing, but it was enough.

The search intensified.

Back at the impound, Evelyn’s van was re-examined.

A junior forensics technician found something missed 12 years earlier, a false panel beneath the cabinet drawers.

Inside was a waterproof field tube, the kind used by geological engineers.

Inside the tube, laminated maps with fine handwriting, eveins, and notes.

One stood out.

July 2nd, test dust 2.

Higher thorate levels than Croft predicted.

He’s lying.

He already found the vein.

Alana suspects.

I think we’re close.

If we vanish, it’s here.

This time, the law didn’t stall.

Croft was arrested, not for murder, not yet, but for unlawful extraction and possession of radioactive material.

He was held without bail.

Rios didn’t say a word during booking, but he looked Croft in the eyes as they fingerprinted him.

She wasn’t obsessed, he said.

She was right.

Croft blinked slowly, and for the first time, he didn’t smile.

Later that night, under flood lights in the evidence bay, Rio stood over the cracked topographic maps and made a silent vow.

If Alana and Evelyn had walked into this storm trying to protect something sacred, then someone would walk back through it to finish what they started.

The search resumed at dawn.

Not a symbolic gesture, but an operational shift.

With Croft in custody, the team no longer had to guess.

They had coordinates, motives, timelines.

The land they were combing wasn’t random anymore.

It was selected, calculated, claimed.

They returned to the Spirits Veil region, this time with aerial imaging, spectral scanners, and ground penetrating radar units mounted on ATVs.

The geology lab confirmed what Evelyn had suspected.

Beneath the ridge lay a shallow horizontal vein of thorite bearing pegmatite unusually close to the surface.

A deposit that if mined could produce a concentrated yield of radioactive rare earth minerals critical to military and energy industries but banned from extraction on protected tribal lands.

The Rangers knew this terrain.

So did the miners who’d been buried by history.

So had Evelyn.

But now so did the law.

3 miles from the burial site, tucked beneath a collapsed mining shelter from the 1940s, they found the first clue.

An old equipment box, rusted but sealed.

Inside were tools, geological sampling vials, two sealed test kits, one labeled May 28th, 2009, the other June 12th, 2009.

A folder was pressed between them, its pages wrinkled but readable.

Typed memos.

Croft’s letter head.

The top sheet bore the heading SVN8 confirmed vein active extraction viable.

Prepare off ledger plan for acquisition.

That document changed everything.

It wasn’t just a case of hidden mining.

It was conspiracy.

Rio sent the evidence to the US attorney’s office.

If Croft wasn’t already the primary suspect in the murder of Alana Skywater, he now carried the weight of federal environmental crimes, conspiracy to violate tribal sovereignty, and willful concealment of radioactive extraction.

Still, none of it was enough to charge him with murder.

Not without Evelyn, not without a confession.

And Croft, for all his smiles and silence, wasn’t talking until they found the second body.

It wasn’t discovered by radar, not by search team strategy.

It was found by the Earth itself.

A late summer storm, brief but brutal, swept across the mesa on August 29th.

Flash flooding carved new gullies into the ridge east of the original burial site.

The next morning, a trail steward hiking a fire break line radioed in a report.

Erosion had exposed part of a wooden support beam near an abandoned minemouth previously marked as sealed.

When a field crew investigated, they found the shaft had collapsed partially inward, but caught in the tangle of beams and debris, was something pale.

The forensic team was summoned immediately.

Inside the shaft, buried under nearly 8 ft of broken timber and loose rock, they found human remains.

adult, female, 60 to 65 years of age.

The bones were twisted unnaturally as if they had been dropped rather than buried.

The skull was fractured.

Multiple vertebrae shattered, but the wrists were intact.

And on the left one, still clasped around brittle bone, was a thin braided bracelet made of horsehair and turquoise beads.

Nita identified it the moment she saw the photo.

It’s Evelyn’s,” she whispered.

She made it herself, said it reminded her she was still a guest here.

The autopsy confirmed the rest.

It was Evelyn Reed.

The coroner ruled the injuries as consistent with a fall, most likely postmortem.

The pattern of breaks and the position of the bones indicated she had been lifted and dropped, most likely into the shaft after death.

Unlike Alana’s burial, there was no reverence here.

No care, just disposal.

A secondary analysis revealed something else.

Traces of copper residue embedded along the broken bones of her left cheekbone and jaw.

An impact mark, possibly from a geologist’s hammer, one of the older models, brass tipped.

When investigators returned to Croft’s homestead to cross-check the tool inventory recovered from his lab, one hammer was missing.

The match was close enough.

Rios didn’t wait.

Croft was moved to an interrogation room at the tribal justice center near Crown Point.

The walls were bare.

The light above him buzzed faintly, casting his face in dull yellow tones.

No press, no lawyers, just Rios and a federal agent seated across the table, a folder in front of them.

Closed.

Croft said nothing.

So Rios opened the folder and began laying out the photographs one by one.

The burial pit, the fetal remains, the thorite analysis, Evelyn’s fractured skull, the bracelet, the mineshaft, the hammer imprint, the test vial with his name on it, and then finally the typed memo.

Croft’s face didn’t change.

Not at first, but when Rios placed down the photo of Evelyn’s face, what was left of it, something shifted in his mouth.

A tick, not guilt, not panic, something quieter.

Resignation.

She wasn’t supposed to bring her, he said finally.

His voice was soft, but his eyes had gone hard.

She was supposed to come alone.

She told me she would, that it would be clean, quiet, but then she brought Alana.

And when I saw her belly, when I realized they weren’t just out here for ceremony, he stopped, his jaw clenched.

You thought they were going to expose you, the federal agent said.

Croft nodded slowly.

She had copies of the surveys, the soil levels, even the investment emails.

Evelyn was smarter than I ever gave her credit for.

And Alana, she never stopped watching me.

It was like she already knew what I’d done, what I would do.

He rubbed his hands slowly together as if scrubbing off years of guilt that had never fully adhered.

I just needed the mine.

That’s all it ever was.

A vein.

One shipment.

No one would have to know.

But they kept coming back.

They wouldn’t let it die.

And so you killed them,” Rio said quietly.

Croft didn’t answer, but he didn’t deny it.

The confession was logged, redacted, sealed.

3 weeks later, Croft was charged with three counts of murder.

Alana Skywater, Evelyn Reed, and the unborn children carried inside her.

The court acknowledged the fetal remains as individual lives under state law.

It was the first time in New Mexico legal history that twins unborn at death had both been named as victims in a triple homicide on sovereign land.

The trial date was set for March.

But Nita didn’t wait for the court.

She went back back to Spirits Veil, back to the burial site.

She brought cedar, tobacco, a basket woven from rivereds, and three small clay figurines, two daughters and their mother.

She placed them gently in the earth where Alana had been found just before the rains returned.

“I’ll carry the rest,” she said aloud to no one.

“And you can finally sleep.

” The wind moved through the juniper.

The sky was empty, and the land, for the first time in 12 years, felt still.

By the time winter settled across the high desert, the headlines had already moved on.

The Croft confession had made a short but intense national ripple framed by clickbait titles and recycled photos.

Pregnant indigenous woman’s remains found after 12 years.

Eco consultant turned killer.

Buried truth beneath sacred ground.

Most outlets focused on the shock of the burial.

Some mentioned the Thorite.

Fewer mentioned Evelyn at all.

None of them mentioned the twins by name.

But Nita did.

She spoke them aloud every morning before her feet touched the floor.

Tally, Nielli, the little moons, she called them.

One for light, one for shade.

She didn’t talk to reporters.

She didn’t give interviews.

She declined every podcast and docuer request.

Instead, she started building something quieter, something stronger, a registry.

It began as a spreadsheet on her old laptop.

names, dates, GPS coordinates, unsolved disappearances of indigenous women from the four corners and beyond.

She tracked every case with even a whisper of environmental conflict.

Every woman who had vanished near disputed land, contested veins, or old mineral maps.

She connected dots no one else was willing to.

By January, there were 41 names.

By April, there were 63.

She called it the Skywater ledger, and she sent it to the Department of the Interior.

No one responded.

But one day, a brown envelope appeared in her mailbox.

No return address.

Inside were printed case files, redacted, scanned.

Each bore the official watermark of the Bureau of Land Management.

One page bore a handwritten note in blocky pencil.

She wasn’t the first.

Keep digging.

Nidita didn’t hesitate.

The ledger became a database.

Then a network, volunteers, coders, legal interns from tribal colleges, former rangers.

They started building cross-referenced maps, connecting industrial filings with tribal complaints, cross-matching survey zones with missing persons.

Alana’s case had broken something open, and Nidita wasn’t going to let it seal again.

Meanwhile, the court case against Croft churned into its pre-trial motions.

His lawyers pushed for exclusion of the Thorite evidence, claiming contamination.

They argued Evelyn had acted with hostility, that Croft had feared for his life, that the confrontation was accidental, self-defense, that burying the bodies was panic.

But none of it held.

The confession had been too clear, the evidence too exact.

The hammer imprint, the particles, the maps, the motive.

Still, the trial date was pushed again and again.

Delays mounted, procedural tangles, defense stalling.

And then one morning in July, Croft was found dead in his cell.

Suicide, they ruled, a bed sheet, a ceiling pipe, no note.

Rios got the call at 6:17 a.

m.

He drove in silence to the coroner’s office, looked at the body, and said nothing.

He hadn’t expected a verdict, but he had expected something like closure.

Instead, all he felt was the shape of another unfinished sentence.

Back on tribal land, Nita gathered with Alana’s remaining family for the final interment.

There were no coffins, no marble stones, just three bundles wrapped in red cloth.

Alana, Tally, and Naelli laid side by side beneath the shadow of Spirit’s Veil.

The burial was done by hand.

No machines, no noise, just prayers in da and Lakota, offerings of cedar, small turquoise beads placed under the tongue.

The land was theirs now, but the silence that followed wasn’t peace.

It was weight.

Rios returned to the site one last time that fall.

He stood near the spot where Alana’s skeleton had been found, now covered again by soil and brush.

The wind carried dust across the ledges.

He thought about the first moment he’d seen the fetal remains curled within her.

How the forensic tech had stopped breathing.

How the entire excavation team had fallen silent like they’d unearthed not bones but a wound.

He thought of Evelyn’s words written years earlier.

If we vanish, it’s here.

And he thought of Croft sitting across the table, so sure no one would ever put the pieces together.

He pulled a small notebook from his coat pocket and wrote a name.

Levi Haskit, Environmental Impact Review, 2008.

Denied permit.

Appealed.

2009.

The same year, Alana vanished.

The same quadrant as the SVN8 vein.

Rios flipped the page and began another entry.

A vein up in Arizona.

Another missing girl.

Another consultant with a shell company.

A rumor about uranium.

He closed the notebook.

looked at the horizon.

Maybe Croft had acted alone, but maybe he hadn’t.

The deeper you dig, the more bones you find.

Two weeks later, Nita received an email from a woman in Montana.

She worked for a nonprofit on the Northern Cheyenne Reservation.

She’d seen the Skywater Ledger.

She had questions, had maps, had stories, names.

Can I speak with you? The woman wrote, “My aunt disappeared in 2010.

She was pregnant, too.

” Nita read the message twice, then she replied, “Yes, tell me everything.

” Outside, the wind pushed against the door of her trailer.

The land was restless.

The work had just begun.

The woman’s name was Marley Two Feathers, and she spoke with the quiet rhythm of someone who had carried pain for a long time without dropping it.

Her voice over the phone was level but clipped every word careful.

My aunt’s name was Willa Willa Fire Moon.

She was 29, about 7 months pregnant when she vanished.

That was June 2010 near Tongue River.

She’d been working with a water rights advocacy group.

They just filed an injunction against a mining survey west of Lame Deere.

Then she went missing.

Nidita’s fingers hovered over the keyboard, recording details in the ledger as Marley spoke.

“Was she alone?” Nidita asked.

“No,” Marley replied.

“That’s the thing.

Her boyfriend was with her.

White guy Mark something.

” “I don’t remember the last name.

” They said they went hiking.

He came back without her, told police she got angry and left.

They cleared him.

Said there was no sign of a struggle.

But my aunt wasn’t like that.

She didn’t just leave.

Not pregnant.

Not in that heat.

She just filed paperwork naming her unborn daughter Kaa.

It was official.

Nita leaned back in her chair, staring at the last name on the list.

Skywater.

How far from the survey zone? She asked.

Five miles, maybe six.

And what kind of mine? Uranium, Marley said.

company said it was exploratory, but people around here know the truth.

They’ve been poking holes in this land since before we were born.

They never ask permission.

They just rebrand and try again.

The next morning, Nita packed her things.

She drove 10 hours north in a borrowed truck through desert, forest, and hills until the ground turned grassy and the wind smelled like water.

She met Marley in person at a church basement in Lame Deer.

They sat at a folding table under humming fluorescent lights while Marley unrolled copies of her aunt’s old advocacy files, maps, letters, permit requests.

One file stood out.

A request for a mineral survey signed by a consultant geocchemist named El Croft.

Nidita stared at it for a long time.

Same signature, she whispered.

Same type face.

He was up here too.

Marley didn’t look surprised.

They all come through eventually.

Croft, others like him.

They change company names, shift funding, but the patterns the same.

They come, they drill, they disappear.

People who interfere.

They went through the files until after dark.

The wind pressed hard against the narrow windows.

The night full of prairie silence.

When Nita finally climbed into bed at a roadside motel, her hands were still shaking.

She dreamed of blood seeping into cracked rock, of voices beneath her feet.

She returned home with copies of everything, added Will of Fire Moon to the ledger, then Kaya.

She opened a new tab and titled it unborn victims unsolved.

Six names, four from New Mexico, two from Montana.

More would come.

By October, Nita had established a partnership with a civil rights law group based in Santa Fe.

They helped her petition the Bureau of Indian Affairs to reclassify several of the cases as interlin violent disappearances tied to environmental conflict.

No one responded at first, but one email leaked.

A chain of internal correspondence about pattern escalation and public optics.

The term MMIW, environmental crossover, appeared for the first time in government documentation.

Then came a whistleblower.

They never gave a name, just an encrypted message routed through two proxy servers.

Attached was a zip file containing environmental study suppressions, including one from 2007 that had been overridden by emergency mineral procurement protocols tied to a post 911 energy directive.

And buried inside one folder, a digital scan of a geological survey marked SVN8, Spirit’s Veil, dated 2005, three full years before Evelyn’s maps, with Lyall Croft’s signature at the bottom.

He hadn’t just discovered the vein in 2009, he’d known all along, and someone else had signed off.

Nidita sent the file to Rios.

He called her 3 hours later.

“Can you forward the entire archive?” he asked.

I’m reopening an inquiry with the Department of Justice quietly.

You really think they’ll listen now? Nita asked.

I don’t know, he said.

But I think Croft was only the start.

Two months passed.

Then a package arrived at Nita’s door, unmarked, no postage.

Inside, an old rusted key wrapped in wax paper tied with red thread.

No note, no explanation.

Nidita stared at it for a long time.

That night, she called Rios again.

“Do you know what this means?” she asked.

He hesitated.

“I think it’s a claim marker,” he said.

“Mining camps used them decades ago.

Hidden compartments, cashes.

If someone left you that, they want you to find something.

But where?” There was silence on the line.

Then Rios said, “There’s one place we never searched.

” The next morning, they met in person for the first time.

She wore a long coat and a scarf embroidered with three moons.

He brought a topo map marked with weathered penstrokes.

We follow the threads, he said.

“Or the ghosts,” she replied.

They drove out in a dusty ranger truck with a bad radio and a broken sun visor.

They drove past Spirit’s Veil, past the old mineshaft where Evelyn’s bones had rested, past the burial site of Alana and her unborn daughters.

The truck bounced over terrain that had once hidden secrets so deep the land had to be wounded to reveal them.

They parked at the edge of an old Aoyo and walked east.

No trail, just instinct and wind.

After an hour, they came to a rock outcrop, not high, not sharp, but flat-faced, with a faint X carved just above the root line.

The key slid into a metal box embedded behind a loose slab.

Inside, another map, new, updated, and beneath it, a single folded letter addressed in perfect handwriting to whomever keeps asking.

This isn’t over.

Keep going.

You’re closer than you think.

It wasn’t signed, but Nita knew the hand.

Evelyn had left more than a warning.

She’d left a trail.

The map was different from the others.

Not handdrawn, not weathered by dust or time.

It had been printed on thick survey paper, the kind used by licensed geologists.

But the annotations, that was Evelyn’s handwriting, unmistakable and steady, marked in red ink with a fountain pen.

Nita ran her fingers over the surface like it was a skin of memory.

The terrain it mapped was just north of the known vein, past the spirit’s veil ridge line and into territory classified on most BLM documents as non-developable, culturally sensitive.

The kind of place contractors avoided.

The kind of place miners dreamed about.

Three red circles marked the page.

One was already known, SVN8.

The second, labeled J9 breach, had no historical reference, and the third was labeled only Ka’s echo.

It was a name Evelyn couldn’t have known.

Not unless she had met Will of Fire Moon or someone connected to her.

Nidita stared at that word for a long time.

“Echo,” she whispered.

Rios read over her shoulder.

“She was trying to show us this all along.

There’s more than one vein, Nidita said.

There’s more than one body, Rios replied.

They camped that night near the base of the outcrop, the box with Evelyn’s map secured inside the truck, wrapped in cloth like an offering.

Neither of them slept much.

The wind made strange sounds through the juniper.

A whistle, then a groan.

They didn’t speak of ghosts, but both of them felt them, watching.

By morning, they set off again, following the trail Evelyn had left deeper into unmarked ground.

By late afternoon, they found the second shaft.

It wasn’t natural.

The square mouth had collapsed inward, half covered by blown sand and lyken.

Old wood supports jutted from the opening like broken teeth.

A coyote skeleton lay near the edge, ribs spled toward the sun.

The map called it J9 breach.

Rios marked GPS coordinates.

Then they called it in.

The excavation began 2 days later quietly.

No media, no sirens, just the steady dig of forensics teams and cultural specialists overseen by a joint task force formed after Croft’s death.

They peeled away layers of stone, root, and sediment until the shaft yawned open like a throat.

They sent drones in first, then people.

30 ft down, they found the first fragment.

Bone, then cloth, then more bone.

Female, adult.

Skeletal remains wrapped in weatherresistant fabric.

A scarf still knotted at the neck.

No ID, but Nita knew.

I’ve seen that scarf before, she told the team.

That’s Willow Fire Moon.

The tests confirmed it.

The body had been buried in almost identical fashion to Evelyn’s.

Hurried, crude, callous.

But deeper in the shaft, beneath a false floor, they found something else.

A second burial, smaller, deliberate.

Inside a rockline cradle, nestled under cedar boughs and wrapped in deerhide was the skeletal form of a fetus.

A girl, Kaa, Willa’s missing daughter, 12 years lost.

And here she was, the excavation team fell still.

One of the techs cried quietly.

Another knelt and whispered a prayer.

Nita didn’t speak.

She couldn’t.

Her chest felt cracked open.

The breath caught between grief and vindication.

She touched the hide wrap gently and whispered her name, Ka.

The discovery changed everything again.

It proved Evelyn’s theory wasn’t an isolated case.

It proved Croft’s reach had extended beyond New Mexico.

It proved Willa hadn’t walked off, hadn’t vanished into the night.

She had been silenced and buried by the same system, the same motive.

protection of extraction, cover up of resistance, murder as maintenance.

The press got hold of it before they could contain it.

Someone leaked drone footage.

The story erupted.

Second indigenous woman found in remote mineshaft connection to Spirits Veil.

Case confirmed.

The Department of the Interior opened an emergency inquiry.

Multiple federal departments announced audits of all mining contracts signed between 2005 and 2015 involving extraction on or near sovereign land.

Three names reappeared again and again.

Croft deceased Geller, a corporate geocchemist tied to both the SVN8 and J9 breach veins.

Haskit a senior consultant who had once tried to suppress environmental reviews in both zones.

Rios tracked them both.

Geller had died in 2019.

Cancer, possibly related to unshielded exposure to thorite and uranium.

But Has he was still alive, living comfortably in a gated home outside Sedona, Arizona.

He refused to answer calls.

So Rios went to him, brought the photos, the maps, Alyn’s annotations, Willa’s scarf, Ka’s bones.

You can let this rot with you, Rio said.

Or you can speak.

Has didn’t blink, but he said one thing.

She wasn’t supposed to find the second shaft.

Then he shut the door.

The task force logged the encounter.

DOJ took over.

But Nita knew what that meant.

He wouldn’t be charged.

He wouldn’t be named.

He would fade into the same dust that had buried Alana and Evelyn and Willa and Ka.

So, Nita made a choice.

She wrote it herself, published it, a full report, names, timelines, maps, photos, documents, all of it, the full truth.

She didn’t send it to CNN.

She didn’t send it to the Times.

She sent it to tribal newspapers and they ran it.

Page one, headline, the women buried so the earth could bleed.

The story spread like fire across nations, across languages.

And the names of Alana, Evelyn, Willa, and Ka were no longer whispers in police files.

They were banners painted on walls, sung in ceremony, carried in marches, etched into the sides of canyons.

A week later, Nidita got another message.

Encrypted, anonymous, one line.

There’s a third shaft in Wyoming.

code name Red Hollow.

She stared at it for a long time, then opened a blank page in the ledger and began again.

The name Red Hollow had never come up before.

Not in the archives, not in Evelyn’s notes, not in Croft’s confession.

But Nita knew by now that the worst places were the ones scrubbed clean, deliberately erased from every official page.

She searched federal geological indexes.

Nothing.

no reference to any red hollow in Wyoming associated with mining, prospecting, or land use.

But tribal memory ran deeper than maps.

She called a friend in Wind River, Joseph Talltry, a language teacher and cultural historian who’d once helped Nita research ancient place names for a school curriculum.

She told him the name, waited in silence.

Red Hollow, he said slowly, like chewing the words.

We don’t say that place’s name much.

Why not? She asked.

Because it’s bad ground.

He paused, then added.

It’s known.

Quietly, not officially.

But people remember women go missing there.

It’s always women.

Nah’s blood cooled.

Do you have coordinates? No, Joseph replied.

But I know someone who does.

He connected her to an elder named May, wounded elk, 82 years old, nearly blind, but sharper than steel.

They spoke for two hours.

May had never heard of Alana Skywater or Will of Fire Moon.

But when Nita described the pattern, “Prospectors, hidden veins, twin deaths.

” May became quiet.

“There’s a rock out there,” she said eventually.

“A red stone that’s not from here.

Stands like a door.

My aunt used to say it was a place where things entered but never came back.

They found a girl there in the 70s.

She was pregnant.

They never said her name after.

Nita felt the weight again, the echo of the ledger swelling before her.

May gave her a location.

Sweetwater County, backount, undeveloped, no structures.

Nidita entered the coordinates.

The satellite view showed nothing.

No road, no trail, just shadowed terrain in the shape of a scar carved into land no one seemed to claim.

She called Rios, told him everything.

He didn’t ask for proof.

He packed his bag.

They met in Rollins 2 days later.

This time they brought back up two forensic techs, one geologist, one tribal ranger from northern Arapjo, and a woman from the missing and murdered indigenous person’s office who had read the ledger and asked to come in person.

The hike to the site took 8 hours, no trail, just ravines and brush and heat.

And then, just as the sun cracked low across the rim of the hill, they found it.

A standing stone, red, unnatural, tall as a person, planted deep in the earth like a warning or a marker.

Behind it, a narrow ridge that dropped into a low basin, a hollow.

No signs, no fencing, no claim tags, but every member of the team felt it in their bones.

“This is it,” Rio said, voice dry.

Nita only nodded.

They camped on the ridge and returned at sunrise.

The drones went first.

30 ft below the surface, buried beneath soft sandstone layers, was a chamber, man-made, rectangular, reinforced with rotting beams, and something inside.

The excavation took days, careful, quiet, like surgery on a wound that bled dust instead of blood.

They cleared the entrance, entered.

Inside, they found what could only be described as a cash.

Six wooden boxes stacked against the wall, each labeled with crude initials.

Inside five of them, soil samples, test files, dated maps, and something else, photos, black and white prints of women, indigenous, some pregnant, some younger, some marked with red X’s.

In the sixth box, they found bones, small, disordered, but clearly human, and not one set.

three.

Three fetal skeletons intermixed as if discarded or stored.

Rios turned away, breathing through his teeth.

One of the forensics techs began crying.

Nidita said nothing.

She was still frozen.

The woman from the MMIW task force whispered, “Triplets?” “No,” Nidita said, her voice shaking.

“Three pregnancies, three lives, but all unborn, all taken.

They collected samples, photographed everything, and in the back of the chamber, carved into the stone wall with the point of a geologist’s pick, were letters, Croft’s initials, and beside them another name, G.

D.

Has it was no longer speculation.

Hasn’t been an investor.

He’d been in the ground digging, burying.

Rios contacted the DOJ with the findings.

The site was immediately sealed.

A second task force was formed with mandates stretching across multiple states.

They called it Operation Hollow Dust.

Over the next 3 months, it uncovered 17 separate mineral surveys conducted without federal authorization.

Nine extraction zones overlapping sovereign land boundaries.

Six whistleblower complaints buried or redirected between 2004 and 2012.

four separate missing person’s cases, all indigenous women, all within 10 miles of those survey sites.

Two recorded deaths ruled accidental that were now being re-examined.

And one journal entry written in Croft’s own hand recovered from a decrypted backup drive.

Has says no one will look here, that if they do, we salt the graves with non-story materials.

that no one will miss the ones who walk between two worlds.

Rios printed the page, brought it to Nita in person.

“This is what they thought of them,” he said.

Nita held the paper, then tore it in half.

They were wrong.

The story broke again.

Bigger this time.

Full investigations, Senate hearings, highranking officials forced to testify.

And one cold morning in February, agents arrested Gerald Dehascuit outside a fishing lodge in Idaho.

He wore a green flannel coat and held a coffee mug that said, “I’d rather be camping.

” He did not resist.

He said nothing.

But in his wallet was a laminated copy of a map marked SVN8.

He’d kept it all these years like a trophy, like a memory, like a reminder of what he thought he’d gotten away with until now.

Nidita received the call from Rios.

“He’s in custody,” she closed her eyes.

“Was he alone?” Rios didn’t answer right away.

“No,” he said finally.

“There were others, but he’s the last one still breathing.

” She nodded.

“I want to see the sight again,” she said.

“All of it.

” Why? To listen.

The wind was shifting.

The land, after all this time, was still whispering.

Nidita stood in the basin of Red Hollow again in early March.

The ground still firm with the memory of frost.

The hollow was quiet now.

The excavation teams were gone.

The press had moved on, but the air still vibrated with a tension that hadn’t left since they opened the chamber.

She walked its edge slowly, boots pressing into soil made sacred by blood.

She didn’t take pictures.

She didn’t speak.

She just stood beneath the red standing stone and listened.

There were no words, of course, no ghosts whispering her name.

But the silence wasn’t empty.

It held weight.

The kind that wrapped itself around the bones of those still buried, still missing, still unnamed.

Back in Shiprock, she updated the ledger.

It had grown beyond a file.

It was a movement now, a mapped and coded history of silence pierced.

A living archive of testimony and trace.

She added three new rows for the fetal remains found at Red Hollow.

They had no names, just tags.

Unknown A, unknown B, unknown C.

She didn’t leave them that way.

She named them LRA, Sanne, and Hope, three daughters whose stories had been severed from time.

The DOJ indictment against Haskit spanned over 200 pages, federal conspiracy, illegal mineral extraction, multiple counts of murder under the Violence Against Women Act, unlawful operation on tribal land.

It was enough to bury him, but it wouldn’t be quick.

He pleaded not guilty.

His lawyers claimed no physical link between him and any of the deaths.

They tried to distance him from Croft, from the maps, from the field journals, from the photos.

They blamed Croft, blamed corruption, blamed environmental overreach, and bad recordkeeping.

But Nita had already prepared for this.

She had built a wall of proof, testimony, chain of evidence.

Whisper to whisper, the voices of women who had been silenced were now speaking through the details.

At the pre-trial hearing, Nidita was allowed to speak.

Not as a witness, not as an expert, but as a descendant of the disappeared.

She stood in the courtroom, her voice calm, but unshakable.

Her words like flint.

I stand here today for Alana Skywwater, for Willa Fire Moon, for Evelyn Reed, for Kaa, for the little moons, for the daughters never named.

The girls taken from their mothers and left in the dark.

They were not minerals, not collateral.

They were lives, and the land remembers.

I do, too.

Has did not look at her, but others did.

The press printed her statement in full.

A journalist from the Navajo Times wrote, “Her words were more exact than the evidence.

They cut deeper than any verdict.

” The trial was set for September.

In the months leading up to it, more files surfaced.

Croft had stored data across five separate encrypted drives.

The DOJ’s tech division, working with tribal cyber units, cracked the final drive in July.

Inside they found recordings, audio files, dozens, and one that mattered most.

It was dated June 21st, 2009, the day Alana and Evelyn left.

The file opened with static, then a strained voice.

Evelyn’s.

She was recording into a field mic.

Testing recording.

This is Evelyn Reed.

June 21st.

We’ve arrived at SVN8.

Alana’s setting up the tent.

I don’t think she knows what I found in the rock face yet.

I can feel it humming.

It’s wrong.

I think Croft’s already been here.

Maybe more than once.

A pause.

Wind.

If we don’t come back, this recording needs to go to Nita Skywater.

She’ll know what to do.

Tell her we didn’t walk away.

We walked into something and it closed behind us.

Nidita listened to the recording in Rios’s office.

She didn’t cry.

She didn’t flinch.

She just closed her eyes and whispered, “I know.

I know now.

” The recording became exhibit 37 in the federal case.

The prosecution team played it in the courtroom during preliminary motions.

It changed the tone of the room.

No one spoke afterward.

Even the judge paused before calling recess.

Meanwhile, the Skywater ledger was gaining traction beyond legal circles.

Universities began referencing it in lectures.

Activist groups used it in organizing.

Artists turned it into murals.

One wall in Albuquerque bore a 30-foot image of Alana.

Her arms extended, two small cradles floating on either side.

Beneath her, the names of the unborn victims painted in ochre.

Tali, Naelli, Kaa, LRA, Sani, Hope.

Nidita stood in front of that wall one summer evening, long after the paint dried.

People walked past her, some stopping, some not.

A young mother with a toddler left a bundle of sage at the base.

A man left a smooth stone etched with lightning.

No one knew who she was.

But she didn’t need to be known.

She needed to bear witness.

The same way Evelyn had, the same way Alana had without knowing.

The same way the land had even when no one else listened.

In September, the trial began.

testimony ran for 19 days.

Experts, rangers, historians, survivors, and finally, Nidita.

She took the stand in a blue dress stitched with constellations and two silver pins in the shape of open palms, one for Evelyn, one for Willa.

She recounted the day the photo came.

The years of silence, the letter, the excavation, the map in the false panel, the standing stone, the ledger, the truth.

When she stepped down, the courtroom was quiet.

Has said nothing throughout.

He stared at his hands like he was still trying to bury something, but the jury didn’t blink.

They deliberated for 6 hours and returned with the word that had taken 12 years to earn.

Guilty on all counts.

Triple homicide, conspiracy, unlawful extraction, violent suppression of environmental opposition, life sentence.

No parole, no deals, no silence.

As the judge read the verdict, Nita closed her eyes.

Rios leaned toward her and whispered, “We did it.

” But she shook her head gently.

No, she said they did.

And somewhere beyond the lights of the courthouse, the desert wind turned over a loose patch of sand and three stars, faint but steady, shimmerred in the evening sky.

After the verdict, the world didn’t slow down.

It never does.

Even when justice is handed down in a courtroom, the weight of what’s been lost doesn’t lift.

It just settles differently.

For Nita, there was no triumph, only air, thin and fragile, as if a long breath had finally been released after more than a decade.

The media swarmed again, hungrier now than ever.

Reporters waited outside the courthouse steps with microphones and drones, each one hoping for the moment.

The quote, the tears, the soundbite.

Nidita gave them none of it.

She walked past them in silence, down the concrete stairs in her turquoise earrings and long black braid, eyes forward, feet steady.

Rios followed a few paces behind her, speaking only when they were clear of the lights and the questions.

They’ll write this the way they want, he said.

But the truth is yours.

Nita nodded.

It always was.

She returned to Shiprock that night.

Her trailer was dark, the desert cool, the wind low.

She lit a small bundle of sage and placed it in the clay bowl on the windowsill.

As it smoldered, she opened the ledger one last time.

Page after page, line after line, name after name.

Each entry was no longer just a number or a date.

They were stories now, whole, connected, carried.

She scrolled to the final tab.

Red hollow shout d confirmed losses three under it.

She wrote status no remaining suspects.

Primary actors identified and convicted or deceased.

Sight sealed by federal mandate.

Reparation claims pending.

Then in smaller font, she typed a line Evelyn had once written.

The land remembers, but it needs help speaking.

She closed the laptop and stared at the sage smoke curling in the moonlight.

It was over, but it wasn’t finished.

In the months that followed the conviction, legislation began to move slowly at first, then with surprising speed.

The Red Hollow case had lit fires that wouldn’t die down.

Pressure mounted from tribal councils, civil rights groups, even international watchdogs.

By January, the Sovereign Protection and Extraction Transparency Act, nicknamed Skywaters Law, was introduced in Congress.

Its primary goals: criminalize unauthorized mineral exploration on tribal land, mandate real-time public access to federal land lease applications, and establish a permanent investigative body to track missing and murdered indigenous persons cases with environmental conflict overlap.

It passed the House, then the Senate.

By summer, it was law, the first of its kind.

Nita was invited to Washington to stand beside the president at the signing ceremony.

She declined.

Instead, she sent a short statement.

This land does not belong to time.

It remembers every footprint, every wound.

We only choose whether we hear it.

I thank those who finally chose to listen.

But know this, the work began before you, and it will continue long after.

Instead, she held her own ceremony at Spirit’s Veil alone.

She walked the same trail Alana had walked, stood at the spot where the last photo had been taken.

She planted three white sage bushes in a triangle.

One for Evelyn, one for Alana, one for the daughters, Tally, Naelli, and the others, Kaa, LRA, Sani, Hope.

Their names were stones she placed gently in the soil, not carved, just painted in ochre with her fingertip.

The wind moved softly through the leaves.

A hawk passed overhead, silent.

The desert shimmerred as if exhaling.

At dusk, she opened Evelyn’s journal one last time.

The last page had no writing, just a pressed flower, wild yrow, dried but intact.

She left it under a rock beside the tallest sage bush, then walked back into the night.

Elsewhere, the story rippled.

A school in Gallup was renamed Alana Skywater Elementary.

A fund was established in Evelyn Reed’s name to support indigenous girls entering environmental sciences.

In lame deer, a mural of Willa Fire Moon holding her daughter Kaa now covered the side of a community center.

Beneath it, in white handprints were the names of every girl from the ledger who had yet to be found.

Nita didn’t stop working.

She updated the ledger every week.

She trained others to use it.

She gave talks at tribal colleges, in gymnasiums, in council chambers, not lectures, gatherings, circles of story.

One day, a girl no older than 12 came up to her after a talk, holding a drawing of a tree with roots shaped like women’s faces.

“Are they still here?” the girl asked quietly.

Nidita smiled.

They never left.

The girl handed her the drawing.

You can keep it.

I will, Nita promised.

She hung it beside her bed.

In August, the MMIW task force invited Nita to help review new data sets, cross-referencing past oil and gas permits with disappearances across North Dakota.

She hesitated, not because she didn’t want to, but because the ledger had started as a story about her cousin.

Now it was becoming everyone’s, but she accepted quietly.

No press, no fanfare.

She packed her bag, closed the trailer door, and drove north across deserts and rivers and mountains.

Through sovereign lands and strip mine scars, through silence and storm, listening, always listening, because the land speaks in more than one voice, and some voices can only be heard after they’ve been buried, but they speak still.

And she was still listening.

The sky over North Dakota was a different kind of wide, colder, bluer.

It stretched in all directions like a silence that hadn’t yet been broken.

When Nita arrived, the wind smelled faintly of diesel and dust.

The oil rigs in the distance hissed quietly like creatures breathing underground.

She met the task force team in a windowless operations trailer parked just outside Fort Berthold.

They greeted her like they already knew her.

Not famous, just familiar.

One of them handed her a folder.

Eight names, he said, all unsolved, all women, all within 15 mi of resource sites flagged for violations.

Nita nodded.

She opened the folder and saw them.

Names, photos, last seen dates, some old, some recent.

The youngest was 17, the oldest, 42.

One of them was pregnant.

She breathed in through her nose, steady, grounded.

The names didn’t scare her anymore.

What scared her was forgetting.

They spent the next 4 days mapping coordinates, cross-checking lease applications, reviewing soil samples, and logistics records that no one had bothered to audit.

Patterns emerged like they always did when you looked closely, when you listened long enough.

Names folded into land.

Disappearances folded into reports.

On the fifth day, a field team found something.

A handheld scanner pinged low radioactivity on a stretch of land supposedly inactive.

They dug 6 ft and found an old casing.

Inside, two soil samples, one empty vial, and a tag.

The tag bore three letters.

RH red hollow.

Not the same place, but the same code.

Reused.

They weren’t done.

Not yet.

Nidita stood at the site, boots pressed into dark soil, hands gloved and still.

The sun dipped low, casting everything gold.

She felt the hum of the land again, faint but pulsing, a sound-like memory being shaken loose.

Later that night, around a fire with the task force team, she told them about Evelyn, about the map in the wall, the key wrapped in red thread, the standing stone, the bones, the courtroom, the mural, the girl with the drawing of the tree.

She spoke like one passing down a teaching, not a tale.

They listened.

No one interrupted.

At the end, one of them, an older man from Standing Rock, spoke softly.

You don’t just keep a record.

He said you’re making ceremony.

Nita smiled gently.

That’s what Evelyn did, too.

I’m just walking the rest.

He nodded.

Well, you walk good.

The fire cracked.

The stars leaned closer.

Somewhere out there, the ledger had grown again.

In the months that followed, Nidita helped build a new digital platform, secure, open- source, controlled by indigenous women across North America.

It became the new face of the Skywater ledger.

Interactive, translatable, traceable.

Names became seeds.

Each one a clickable point rooted to the land it had vanished from.

When you hovered your mouse, a story bloomed, a photo, a map, a sound bite, a testimony.

It was no longer just data.

It was presence.

And it kept growing.

Canada reached out next.

Then tribes from the Amazon.

Then Sammy organizers in Northern Europe.

A coalition formed.

Informal but real.

People who had no choice but to remember what others refused to see.

Nita kept her role small.

She declined TV appearances, ignored the invitations to award ceremonies.

She stayed near the work, near the names, near the places where women still vanished and the soil still remembered.

Years passed, not quickly, not dramatically, just with the slow, patient gravity of time spent listening.

The mural in Albuquerque faded from sun and rain, then was repainted.

Larger this time, more names.

The little girl who had drawn the tree with roots became a college student.

She sent Nita a letter.

I’m going into forensic anthropology.

I want to find the ones who didn’t get found in time like you did.

Nita kept the letter in her ledger case.

By the 10th anniversary of Croft’s confession, the legislation inspired by the case had protected over 300,000 acres of sovereign land from unauthorized exploration.

Environmental consultants now had to complete cultural ethics training.

Federal oversight teams were required to partner with tribal historians.

Not perfect, but better.

The kind of better that holds when people care enough to hold it.

One night, alone beneath a moon too bright to ignore, Nita dreamed of Alana.

Not in pain, not in the shallow grave, but standing tall in the desert.

hair loose, smile wide, hands on her full belly, the little moons laughing in her arms.

Evelyn stood beside her, smudged with dust.

Alive in that way, memory makes possible.

They didn’t speak, but they didn’t have to.

In the dream, Nidita just nodded, and they nodded back, then faded into mourning.

The last update to the Skywater Ledger bore no timestamp, no author line, no watermark, just one entry.

Entry 641.

No name, no photo, just this found, carried home, not forgotten.

And beneath that, a symbol.

Three small circles not touching, but aligned like stars or daughters or bones resting side by side in sacred earth.

And the wind has always kept whispering.

News

El Mencho’s Terror Network EXPLODES In Atlanta Raid | 500+ Pounds of Drugs SEIZED

El Mencho’s Terror Network EXPLODES In Atlanta Raid | 500+ Pounds of Drugs SEIZED In a stunning turn of events,…

Federal Court Just EXPOSED Melania’s $100 Million Crypto Scheme – Lawsuit Moves Forward…

The Melania Trump grift machine, $175 million and counting. Okay, I need you to stay with me here because what…

Trusted School Hid a Nightmare — ICE & FBI Uncover Underground Trafficking Hub

Unmasking the Dark Truth: How Human Trafficking Networks Can Hide in Plain Sight in Schools In the heart of American…

Native Family Vanished in 1963 — 39 Years Later A Construction Crew Dug Up A Rusted Oil Drum…

In the summer of 1963, a native family of five climbed into their Chevy sedan on a warm evening in…

5 Native Kids Vanished in 1963 — 46 Years Later A Chilling Discovery Beneath a Churchyard….

For nearly half a century, five native children were simply gone. No graves, no answers, just silence. In the autumn…

Two Native Brothers Vanished While Climbing Mount Hooker — 13 Years Later, This Was Found….

Two Native Brothers Vanished While Climbing Mount Hooker — 13 Years Later, This Was Found…. They vanished without a sound….

End of content

No more pages to load