In the early hours of July 4th, 1833, while Charleston celebrated white men’s freedom, 12 plantation masters fell silently inside the Whitaker Estates’s grand house.

Their killer used no knife, no gunpowder, only fire, patience, and poison.

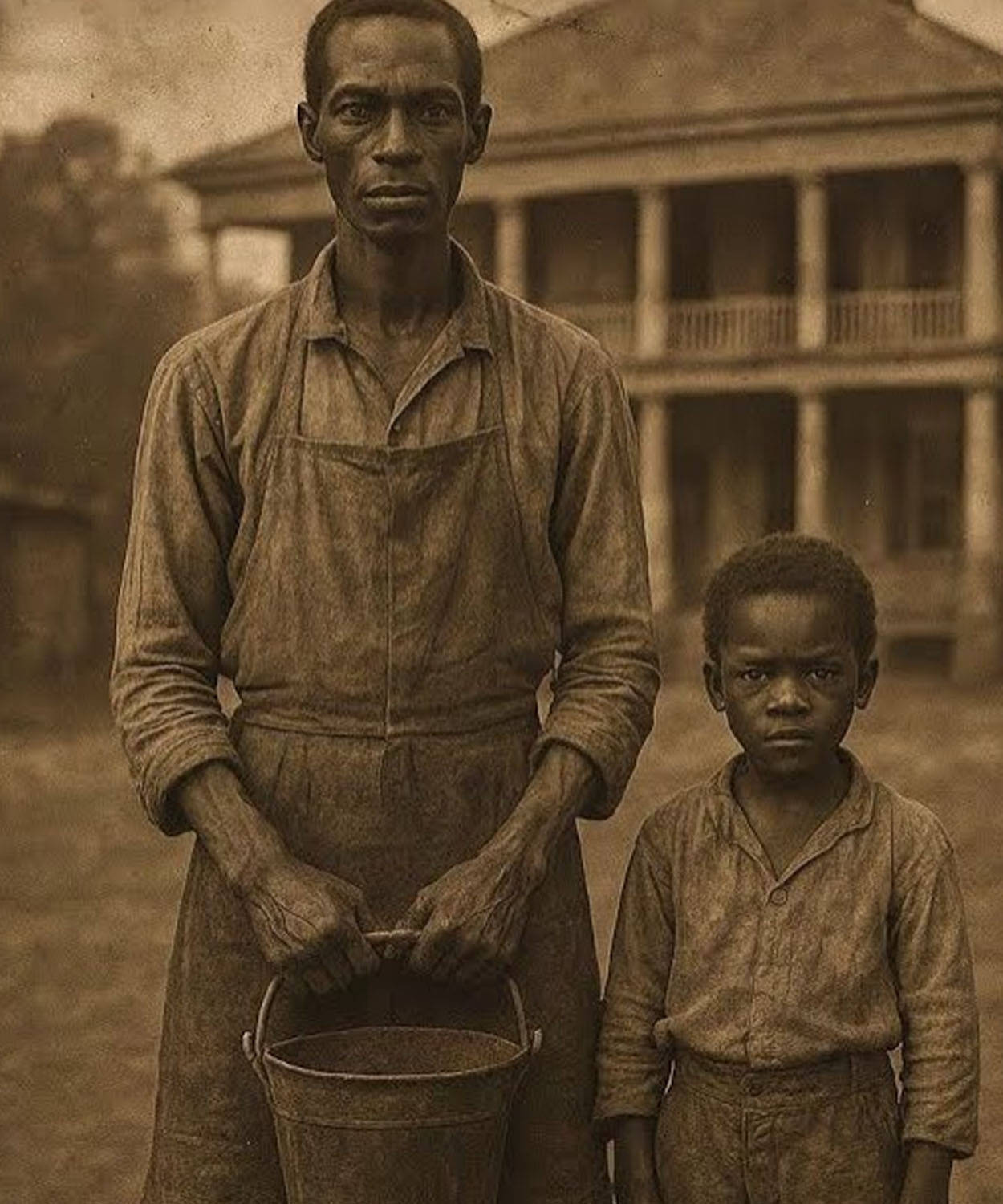

His name was Samuel.

For 20 years, he cooked for the very men who sold his son, tore him from his beloved, and laughed as the whip split his back.

Son of an African healer, Samuel knew that some leaves kill slowly.

Too frail for the fields, he was thrown into the kitchen where he learned more than recipes.

He learned to listen, to wait, to plan.

Each master had a favorite dish, a secret illness, a fatal craving.

And Samuel remembered for 10 years, he seasoned his revenge in silence.

And that night, as they raised their glasses to freedom, he served justice on 12 plates, each bite a sentence.

This is the story of a man who turned the kitchen into a battlefield, who didn’t run, who never begged, and who proved that memory can be the most lethal weapon of an enslaved people.

The bodies were still warm when the sun dared to rise.

12 men lay sprawled across the polished floors of the Whitaker Plantation House, faces twisted, jaws locked, eyes glassy with the shock of a death they never saw coming.

Some collapsed over fine mahogany tables, others slumped in chairs that had once held the weight of their arrogance.

A few had tried to crawl, dragging themselves through their own vomit and bile, clutching at throats that no longer obeyed the air.

Outside the plantation stirred.

The enslaved watched from the shadows.

Silent.

No cries, no prayers, just eyes.

Eyes that had long since learned to speak without mouths.

They had heard the groans in the night.

Seen the flicker of candle light dancing wild through the grand hall windows.

Smelled the iron in the air.

Not from musketss or war, but from within.

From the insides of the men who had claimed ownership of souls.

And in the center of it all stood him.

Samuel.

No chains, no whip, no blood on his hands.

Just the scent of cinnamon, bay leaf, and something else.

Something no one could name, but every slave had felt in their bones.

Reckoning.

He didn’t run.

He didn’t shout.

He stood by the hearth, apron still tied, his back straight, eyes fixed on nothing and everything at once.

A constable’s boots echoed down the marble hallway.

Behind him, three armed deputies, hands shaking more than they’d admit.

The Whiters were not just any family.

They were pillars, foundations, owners of rice fields that stretched for miles, of people whose names had been buried in ledgers and graveyards without markers.

To see them like this, twitching, foaming, stripped of dignity, was to watch the world tilt.

The constable raised his voice.

Samuel, did you do this? He didn’t answer, didn’t blink, but something passed over his face.

A memory, maybe a name, a prayer, or the last words of the woman they sold from his arms.

The constable stepped closer.

Speak.

Still nothing.

But in the silence there was thunder.

Not from the sky it was clear as bone, but from the years of screams buried under this very floor.

One of the deputies gagged at the smell.

Another muttered, “What kind of sickness is this?” Samuel finally turned his head.

Slow, deliberate, and spoke.

They died free, just that, nothing more, and it was enough to send a shiver down the spine of every man in uniform.

Long before Charleston, long before the chains and the sugar and the screams, there was a river and a woman who spoke its language, she was called Neafoula.

In the land where the bow carved names into wood and memory, she was a healer, a woman of roots and ash, of silence and remedy.

Her hands knew how to cradle pain and how to bury it.

She didn’t just treat wounds.

She spoke to them.

She whispered to leaves, boiled truths into tease, and kept a garden where no man dared to tread barefoot.

Samuel was born in the season of thunder under a sky that cracked like whips would later do.

He didn’t cry when he arrived.

Nafoula said that meant he had heard the world already and found it wanting.

He was a small child, fragile in bone, quick in mind.

While the other boys wrestled and chased, Samuel watched.

He memorized.

He listened when the old ones spoke about bark that could stop a heart in four beats.

He helped his mother sort herbs from poison, even when the two wore the same green.

Nafouloola taught him how to read wind, how to tell the difference between hunger and death by the shape of a man’s fingernail, how to slice open a tuber and tell if it would cure or kill.

He who controls what goes into the body, she’d say, controls the soul, he laughed, then thought it just the riddles of old women.

Then the boats came.

The chains were cold, but the silence on that ship was colder.

Neafoula was there until she wasn’t.

One night he woke up to her body gone.

The chain that once bound her wrist swinging empty.

No screams, no goodbye, just absence.

The kind that doesn’t leave bruises, only echoes.

He was 10 when he arrived in Charleston.

Alone, branded, renamed, resold.

They gave him clothes too big and a name too small.

Samuel.

The Whitaker plantation didn’t want another boy for the fields.

They needed a runner, a cleaner, someone to scrub the corners and carry messages.

someone the masters wouldn’t notice.

But they did notice one thing.

The boy didn’t flinch around fire.

He moved through the kitchen like he’d lived there in another life.

When the head cook scolded his hand with hot fat, Samuel didn’t cry.

He bit down hard and stared at her with something that didn’t belong in a child’s eyes.

She never touched him again.

Instead, she taught him to slice onions fast, to season with salt and cruelty.

She taught him that food wasn’t just nourishment.

It was hierarchy.

The masters ate roast pheasant with wild fig glaze.

The slaves ate cornmeal and lard leftovers if they were lucky.

Samuel learned.

But he didn’t just learn cooking.

He learned how they ate, when they drank, what made their bellies ache, and what cured them.

He began to keep a list, not on paper, but in memory, a ledger of power, a catalog of vulnerability.

And deep inside, something his mother planted began to bloom.

He was 12 when they stopped calling him boy and started calling him kitchen hand.

A promotion, they said, like it was a blessing.

But the kitchen in the Whitaker plantation was no sanctuary.

It was a furnace, a sanctum of heat, sweat, grease, and orders barked like lashes.

It stood just behind the main house, built from old brick and smoke darkened wood.

There the air never cooled.

Even in winter, the fire never died, and neither did the hunger of those it fed.

The field slaves envied the ones inside.

They didn’t know.

They didn’t know that the kitchen had its own whips, invisible ones.

Samuel felt them all.

The head cook, Miss Gertie, was a woman made of steam and spite.

A freed woman on paper, but owned in spirit.

She ruled the kitchen like a ship’s captain, and Samuel was the smallest deckhand.

She slapped when the stew boiled over.

She kicked when he peeled potatoes too slow.

But she taught, too, in the cruel way that the world teaches the weak to survive.

“Watch them eat,” she’d whisper through cracked teeth.

“They show you who they are with every bite.

” and Samuel watched.

Watched how Master Edwin Whitaker chewed his beef too long on the left side, the right jaw inflamed from some lingering rot.

Watched how Mr.

Lambert from down river had to drink warm wine before dinner or his stomach would seize.

Watched how Judge Hartley always left the pickled beets untouched.

Allergic, he said, and proud of it.

Samuel remembered them all.

At night, when the coals died and the house quieted, he would sit alone on the kitchen step, apron stained, hands blistered, and recite the list of their afflictions like psalms, toothaches, swollen bellies, itchy eyes, shaky hands.

He began to pair them with plants, a bitter root for Edwin, a white powder for Lambert, crushed seeds for Hartley.

No one noticed the boy whispering to himself in the dark.

They thought it was madness.

It was memory.

He didn’t just study sickness.

He studied power, how it moved, how it dressed, how it laughed over meat cooked by someone it would hang for stealing bread.

And Samuel, small, quiet, forgettable Samuel, became the most informed man in the county, because they never hid anything from the one who fed them.

One evening, after a summer storm, Miss Gertie clutched her chest and dropped beside the oven.

No screams, no final prayer, just steam and silence.

By morning, Samuel was wearing her apron.

Not because they trusted him, because he was there, because no one else wanted the heat.

And from that day on, he served the masters their meals.

Stews that simmerred for hours, cakes so moist the women moaned.

Oysters chilled just enough to remind them of Charleston wealth.

He became the cook, the one who stirred with care, the one who knew what they liked, and more importantly, what they feared.

Her name was Adira.

It meant strong in her mother’s tongue, and strength was all she had left.

She arrived at the Whitaker plantation during the rainy season when the rice fields flooded and the mosquitoes flew like ghosts.

She was maybe 16, maybe older.

No one knew.

Skin the color of cinnamon bark, eyes that refused to lower.

Even when the overseer barked.

Samuel saw her first from the kitchen window.

She was carrying a sack of grain on her back, barefoot in the mud, refusing to stumble.

The other girls laughed behind their hands.

She ain’t gone last, but she did, and she didn’t bend.

Adira was assigned to the drying shed, sorting rice, cracking husks.

Her hands bled daily, but she never complained.

And at night, when the drums whispered low across the quarters, Samuel would see her, not dancing, not praying, just standing by the fig tree, watching the sky.

He spoke to her only after a month, offered her a scrap of yam, still warm.

She didn’t smile, but she took it.

That was enough.

They never had the luxury of romance.

No letters, no cording, just glances by the well.

Touches passed like contraband.

Whispers shared in the dark.

He told her about his mother.

She told him about a brother sold in Georgia.

Both of them carried wounds that couldn’t be seen.

And one night under the kitchen’s eaves during a thunderstorm, she whispered in his ear.

They think we are soil, but we remember the sky.

He didn’t sleep that night.

Not because of the lightning, because for the first time he felt something other than hatred in his chest.

They found her 2 weeks later.

Not dead, not beaten, gone.

Sold to a sugar plantation in Louisiana.

No warning, no goodbye, just a name scratched out in the Whitaker inventory.

Samuel asked the overseer why.

She don’t look down when she talked, he said.

Pride don’t pick rice.

Samuel didn’t speak for two days, and on the third, he began collecting things.

A certain mold from the rice barrels, a bark that dried black, a root that smelled like iron when crushed.

He ground them with a stone, slow and silent.

He marked a small pouch and buried it under the fig tree.

No words, just the act.

The beginning of something that would take 10 years to complete.

He cooked that night like always.

Pork stew with corn cakes.

Mr.

Whitaker licked his fingers and called it divine.

Samuel didn’t flinch, didn’t blink, but inside he boiled.

Revenge doesn’t ripen fast.

It must be cultivated.

Like rice, like rot.

Samuel knew this.

He didn’t grab the first bottle or blade.

He waited.

Waited as years passed.

like crows, black, patient, always watching, waited as other names were scratched off ledgers as new masters came to drink, eat, and speak of freedom while tightening chains.

And while they laughed, he studied.

He started with books, cookbooks, yes, those were expected, but also farmers, smuggled pages from doctor’s shelves.

He cleaned the guest rooms and borrowed papers left behind by Whitaker’s guests, recipes for digestion, remedies for headaches, poisons mistaken for cures.

Then came the garden.

Every plantation had one.

Mint, sage, rosemary, thyme for tea, for chicken.

But hidden behind the kitchen, where the soil ran dark and wet, Samuel planted his own.

Nightshade, caster bean, hemlock, and most sacred of all, oleander, a beautiful killer, leaves like silk, flowers like blood.

A single crushed leaf could stop a heart in less than an hour, but only if brewed just right.

He tested carefully.

A stray rat in the kitchen.

A cruel dog no one would miss.

Each death studied, each effect recorded, not on paper, but in memory.

He adjusted doses like a maestro tuning an instrument.

Not too fast, not too slow.

The goal was always the same.

Death that wore a mask.

And then came the list.

12 names.

All regular guests of the Whitaker estate.

All men who’d raised whips signed sails.

Smiled while children were taken from their mothers.

Each name paired with a weakness, a food preference, a cause of death that would raise no suspicion.

Judge Hartley, soft spot for candied figs, history of fainting spells.

Reverend Cole, allergic to shellfish, constantly ill from God’s will.

Master Edwin Whitaker, ulcers, swollen liver, addicted to fatty meats.

Samuel charted them all, not with ink, with discipline.

At night, he would kneel by the hearth, pretend to stir soup, and murmur the sequence under his breath.

12 guests, 12 plates, 12 goodbyes, one for Adira, one for his mother, one for the boy who hanged himself in the barn after they took his sister, one for the girl who bled out after childbirth, while the mistress complained of the sheets.

Each dish would carry a memory, each swallow, a scream gone unanswered.

And in this slow, careful preparation, Samuel became more than a cook.

He became a weapon sharpened not with steel, but with silence, science, and time.

He didn’t need paper.

The names lived in him like old scars.

Each man, each guest, each villain who crossed the Whitaker estate had been measured not by their wealth, not by their titles, but by their weaknesses.

Samuel had studied them for years.

The way a falcon watches prey before the dive.

Not just what they ate, but how they chewed, what made their guts turn, what kept them awake at night.

He knew that Master Edwin Whitaker, Lord of the plantation, had a failing liver and a gluttonous love for pork fat.

The man sweated during meals and wheezed through his sleep.

So Samuel chose a thick, greasy dish.

Pork belly cooked low and long, laced with crushed oleander leaf.

The bitterness would vanish in the fat.

But the poison would not.

It would slide into Edwin’s blood like a quiet flame.

Judge Hartley, who once ruled that a slave girl brought her own suffering by being disobedient, adored candied figs.

He dipped them in brandy and sucked the sweetness off his fingers.

Samuel used that indulgence.

He boiled fox glove into the fig syrup, letting its fatal kiss soak deep into the fruit.

The old man would die with a smile on his lips and poison in his veins.

Reverend Cole was next.

He spoke of salvation, of divine order, while whipping boys for spilling water.

He avoided shellfish, claimed it gave him visions, but loved anything creamy.

So Samuel folded caster bean extract into the heavy cream of his oyster stew, knowing that by the time the reverend felt the fire in his gut, no prayer would reach him.

One by one, he remembered them.

Mr.

Lambert, with his bloated belly and bourbon breath, who once broke a slave’s ribs for singing too loud, Samuel added a touch of aenite to his drink masked by the smokiness of his favorite rye.

Colonel Wexley, who spat tobacco on the backs of kneeling men, found his final cigar laced with monkshood.

He never saw it coming.

Mr.

Bryce, the banker who bought babies like livestock, insisted on milk with every meal, despite how it made his stomach churn.

Samuel gave him what he wanted with a dose of Belladonna.

He died alone, pants down, on a privy that had once denied slaves its use.

And there were others, like Young Beach, the drunk who branded women for sport, and Dr.

Miles, the physician who swore that black flesh felt less pain.

Samuel chose their poisons carefully.

You for beach, hemlock for the doctor, gentle, undetectable, and deserved.

12 men, 12 ailments, 12 final meals.

None of them saw the cook.

None of them noticed the way he stirred the sauce an extra time or how he touched each plate like a priest offering last rights.

To them, he was still just Samuel, quiet, loyal, invisible.

But to the spirits watching from the fields, from the chains, from the graves that had no names.

He was becoming something else.

A hand of the ancestors, a knife in the shape of a man, a cook preparing not a feast, but a reckoning.

And the table was nearly set.

It was the 4th of July, 1833.

The stars above Charleston flickered behind thick clouds, as if even the heavens had no wish to bear witness.

At the Whitaker estate, the rice fields swayed heavy and full, and the mosquitoes were already biting.

But inside the grand house, the air was warm with laughter, music, and arrogance.

12 men, dressed in their finest linen and dripping with the gold bought by other people’s suffering, gathered around a table that stretched longer than any family ever would.

Samuel stood in the kitchen doorway, still as stone.

He had risen before dawn, hands steady, eyes hollow.

The dishes had been planned like a sermon, each spice a scripture, each plate a prophecy.

The pork belly for Edwin was glazed and caramelized.

The fig preserve for the judge shimmerred like amber.

The oyster stew for Reverend Cole steamed gently in a porcelain bowl.

Every plate was positioned.

Every utensil shined.

The table looked divine.

and Samuel.

He smiled, not because he felt joy, but because the world had finally balanced, if only for a moment.

As the guests took their seats, the sound of silverware striking China echoed like tiny bells of doom.

To freedom, said one.

To the American spirit, said another.

The toast rose, crystal glasses clinkedked, and Samuel served them not with bitterness, with precision, with the grace of a man carrying the weight of his ancestors.

He moved silently from plate to plate, bowing slightly as he’d always done.

No one noticed the flicker in his eye.

No one asked why his hands didn’t shake.

They ate.

Oh, how they ate.

First came the pleasure, the sweetness, the fat, the salt that danced on their tongues.

Then came the silence.

A long, cold silence, the kind that crawls in from the edge of the room and wraps itself around the heart.

It began with Judge Hartley.

He dropped his fork, his fingers curled, his mouth tried to form words.

Perhaps scripture.

Perhaps fear, but only foam answered.

Then the reverend.

He clutched his belly and leaned back, eyes wide, his spoon clattered to the floor.

Edwin Whitaker stood wheezing, face slick with sweat.

He reached for water, for air, for anything, but found nothing.

His lips turned blue.

He fell into his plate.

Chaos erupted.

Chairs scraped.

Men shouted.

One crawled toward the door.

Another vomited blood into a napkin stitched by enslaved hands.

Samuel didn’t move.

He stood near the hearth, watching the fire behind him, casting long shadows.

To them, he was still the cook, still the servant, but to himself he was finally free.

One of the guests, his face pale with terror, pointed.

You, what did you? Samuel raised his eyes, calm, cold.

I remembered, he said.

And in that moment, not one of them knew what he meant, but they felt it.

The weight of every lash, every stolen name, every torn child, every silenced scream.

He didn’t run.

When the constables arrived, he was still there, apron clean, eyes sharp, surrounded by the dead.

He had served them their last supper, and watched them swallow justice.

The first to fall made no sound.

Judge Hartley simply stiffened, spoon frozen midair, and then slowly his eyes rolled back as though something ancient had finally claimed him.

He collapsed into his candied figs, the sweetness mixing with foam at the corners of his mouth.

The room fell quiet just for a second.

Then Reverend Cole began to moan.

His chair scraped backward as he clutched his gut.

Face flushed and slick with sweat.

He knocked over his wine trying to stand, then collapsed into it, shaking like a man possessed.

Colonel Wexley stood, coughing violently, blood misting his linen collar.

Something’s wrong, he gasped, but no one listened.

They were all feeling it now.

A tightening in the throat, a twisting in the belly, a tremor behind the eyes.

One by one, the masters broke.

Mr.

Bryce staggered toward the fireplace, tripping over a foottool, vomiting a dark, oily mess as he went.

He screamed for a doctor, then fell, hitting the floor with a crack that silenced even the musicians outside.

Nathaniel Beach knocked over a candelabroom as he tried to run.

He made it to the hall before collapsing, gasping, convulsing like a dying fish, his white shirt stained with wine and bile.

Dr.

Miles, of all men, should have recognized the signs, but his hands trembled too much to do anything.

He looked around the room, eyes wide with horror and disbelief.

“Poison,” he rasped.

“We’ve been.

” Then he collapsed.

The pianist outside stopped playing.

The laughter faded.

Someone screamed.

The Whitaker estate, once a monument to southern order, had become a ruin in minutes.

And through it all, Samuel stood still.

He didn’t move as they begged, didn’t speak as they clawed at the floorboards.

He watched like a man watching weeds die after years of planting.

They had eaten well.

They had died worse.

Mr.

Lambert tried to make it to the porch.

His body collapsed halfway, half inside, half out, as if even the house wanted him gone.

Wesley Grant, the slave catcher, died slowest.

His hands reached out towards Samuel, pleading.

Please, please, what did I do? Samuel looked at him.

Just once.

You forgot, he said.

Charles Tilling, the quiet one, the whisperer, tried to crawl.

His mouth moved, but no sound came.

He looked at Samuel with wide, watery eyes, as if suddenly seeing him for the first time.

Too late, the house groaned under the weight of the dead.

By the time the constables arrived, the bodies had cooled.

12 men lay scattered across polished floors and velvet chairs.

The air stank of sickness, smoke, and something heavier.

Retribution.

Samuel was still in his apron, still standing.

They grabbed him roughly, shackled his wrists, dragged him through the very halls where he’d once carried roast duck and mold wine.

They asked him why.

He said nothing.

They threatened him.

He smiled.

One constable, young and pale, couldn’t meet his eyes.

Why would you do this? He asked, voice trembling.

Samuel’s answer was quiet.

They taught me how.

They dressed him in a coarse white shirt for the trial.

Said it was for decency, as if any part of this place had ever known the word.

Charleston’s courthouse stood like a cathedral of rot.

white columns, red brick, black history bleeding between the mortar.

They sat him in the center of the room, not in the dock, but on a wooden stool too low for dignity.

The crowd filled every bench.

Landowners, overseers, housewives in mourning veils.

Even those who had never set foot on a plantation came to see the cook who dared poison the gods of the south.

But Samuel didn’t see them.

He saw the shadow of his mother’s hands grinding herbs by fire light.

He saw Adira’s smile before she was sold.

He saw the boy who took his own life after the master’s daughter cried wolf.

He saw memory, not men.

The prosecutor called it devilish.

Premeditated murder.

He spat of 12 honorable men.

They showed the coroner’s notes, vague, trembling documents that danced around the word poison without ever daring to confirm it.

No one could explain how 12 men could fall on the same night at the same table from 12 different symptoms unless the devil himself had walked into the kitchen.

But they knew better.

They knew who had walked in.

Witnesses came.

The maid said Samuel was always quiet.

The stable boy said he was odd, always watching.

A field hand said he heard Samuel whisper names in the dark.

Even the butcher said he was too smart for his skin.

Samuel never spoke.

Not once, not when the judge demanded a confession.

Not when they offered him a priest, not even when they dragged in the bloodstained aprons, laid them on the floor like bodies.

He just sat there straight back, eyes fixed forward as if the room didn’t deserve to be seen.

One juror wept when the verdict was read, “Not for Samuel, for the world that had been cracked open.

Guilty, the sentence, death by hanging, to be carried out publicly so others might learn the price of vengeance, but they had it backwards.

” Samuel hadn’t acted for revenge.

He had acted for remembrance.

The crowd wanted rage from him, or sorrow, or pleading.

He gave them silence and in that silence the air grew heavy as if everyone in that room suddenly remembered their own sins.

When the guards came to take him away the judge asked one final question.

Why? He said just that.

Why? Samuel looked up for the first time and whispered so they’d never feel safe again.

The morning air carried a thin chill as if the world itself hesitated to speak.

At dawn on July 5th, 1833, the square before Charleston’s courthouse pulsed with silent anticipation.

Lanterns still glowed in gallery windows, their amber light trembling on white faces pressed close to iron railings.

Merchants lingered near wagons, children perched on shoulders.

Gossip buzzed like flies in the oppressive heat before the ritual began.

Even the preacher stood near the gallows, one hand clutching his Bible, the other fidgeting with a noose draped across his arm.

At the center of it all stood Samuel, resolute in his coarse white shirt, which the guards had forced him to wear for decency.

Every thread seemed unnatural against his skin.

Yet he embraced it like armor.

His bare wrists were cuffed and chained, but his posture did not bow.

On his face was neither fear nor regret, only a stillness that spoke louder than any speech.

The sheriff climbed the steps slowly, his heavy boots marking every heartbeat.

He cleared his throat.

The rope suspended from the gallows creaked softly, an instrument ready to play its final note.

Samuel Whitaker, the sheriff began, voice wavering beneath the legal gravity of the moment.

For the murder of 12 men by poisoning on the 4th day of July, 1833.

You are hereby condemned to death by public hanging.

Gasps rippled through the crowd.

Some whispered curses.

Others nodded as if finalizing a contract too long overdue.

The wind teased the leaves of the nearby fig tree, the very one under which Samuel had buried his first pouch of vengeance as if applauding silently.

No one expected a plea.

They expected pleading lips, bowed head, tears betraying his silence.

They expected shame.

They got stillness.

Samuel was offered a hood.

He refused.

His eyes remained visible.

They were calm, piercing, entirely unbroken.

Through them passed memories, his mother’s hands sorting venomous herbs by fire light.

Adira’s face as she looked to the sky, not to the ground.

The boy who hanged himself in silence.

The barn empty except for a single rope and two cold footsteps that never returned.

The rows of crops watered with tears.

Fields closing in like coffins.

The 12 bodies that lay scattered in the Whitaker house the night before.

Testament to patience, burdened justice, ancestral precision.

The sheriff paused, his voice softened, nearly drowned by the slow whisper of the crowd.

Make peace, Samuel.

Samuel lifted his chin.

He whispered, barely audible.

Yet the breeze carried it past every ear, to every silent corner of that square.

I have.

The trap door opened with a final groan.

Steel hinges complaining under the weight of silence.

For a moment, Samuel did not fall.

He rose.

He rose like a bird freed, like a spirit unshackled, like a memory refusing erasia.

His body stretched tall for a heartbeat that felt eternal.

The fabric of the world seemed to shiver as if recognition itself paused to honor what had been done.

Then gravity claimed him.

His descent was a whisper through the sheet of cloth.

The noose tightened.

The breath left him.

And then stillness.

The square stayed silent for what felt like hours.

A lone gust rattled the fig leaves.

Even the preacher lowered his head.

No one moved.

Samuel’s body was cut down and carried beneath a gray shroud through black iron gates.

No prayers, only cold earth awaited.

They buried him in a shallow grave just beyond the city limits, beneath a sludge of clay and forgotten names.

No marker, no ceremony, just the ignorant weight of Erasia.

They believed they had snuffed out remembrance.

But they were wrong.

Word spread first in the quarters, then along whispered paths, down river to Louisiana sugar estates, up river to Virginia tobacco fields, and across state lines to Georgia kitchens.

Enslaved cooks spoke of him as if he were still present at the hearth.

He stirred justice into their plates.

He fed his father’s blood language to the mouths that spat on him.

Now he is flavor and fear.

Whispers turned into legends.

Cooked meals tied to tales of revenge.

In Virginia, a cook refused to serve supper and quietly burned the pantry one evening, refusing to feed the masters one last time.

In Louisiana, three men were found foaming in their sleep beneath white sheets.

The kitchen door tied shut from the inside.

In Georgia, a boy was caught sketching a noose and beneath it 12 names.

No words, just carved initials.

They said Samuel’s ghost walked through kitchens at night, robes of smoke trailing him, hands still stained with justice.

And that fig tree in the spring after his death, its blossoms turned deep red.

Though the tree had never been touched, never watered, never mourned, as if the roots absorbed blood instead of water.

They said Samuel did not die.

He became something else.

A flavor as sharp as bay leaf, as bitter as hemlock, as cold as custard root.

A whisper behind the stove, reminding that knowledge is power, and the quiet can be sharper than steel.

A warning to those who think they own bodies, tongues, minds, fields.

In the years that followed, paranoia spread through the slaveolding elite like a fever.

They suspected every cook, every servant, every child who refused a plate.

No one trusted the kitchen.

No one trusted their own appetite.

In Charleston, a commissioner wrote, “The fatal banquet at the Whitaker House opened a wound that never healed.

Cooks became suspects and meals were feared.

” It was true.

Some masters restricted cooks.

Some homes refused black staff altogether.

Others forced overseers to supervise every dish.

They baked bread only in sight of whites.

They refused oysters or figs or any meal that might hide death.

But the fear was too late.

The spirit had flown.

Samuel became legend.

Among the enslaved, he was a saint of resistance.

Mothers whispered his name as they wo corn husks into baskets for the field, teaching their children that vengeance could be served in silence.

Among abolitionists, he became a cautionary tale, not martyr, but reminder, a man who chose justice with his mother’s knowledge and his own memory.

Among the white elite, he was a ghost story, a shameful whisper.

They told his story in parlor rooms, not as history, but as warning.

He may have been cook, but he ended up as judge.

And now when you raise a glass, whether in celebration, in toast, in sorrow, ask yourself, what are you toasting? What violence buried under sugar, hidden in speech, served with a smile, had to occur so you could drink freely? Whose cries became seasoning? Whose weakness became your table? Samuel, small, isolated, labeled invisible, turned intelligence, patience, knowledge into the most lethal weapon.

He proved that cruelty can be undone by discipline, that silence can carry a legacy, that a meal could be a judgment.

He didn’t seek freedom.

He sought justice and served it cold.

If you enjoyed this story, subscribe to the channel, turn on the notification bell, leave a like, and share it with someone who needs to hear this truth.

It really helps the channel keep bringing real stories that never make it into the history books.

News

Nick Reiner Breaks Silence In Court – You Won’t Believe What He Said

Nick Reiner Breaks Silence In Court – You Won’t Believe What He Said I will not go to jail. That’s…

The Overseer Slapped the Quiet Slave Woman — He Didn’t Live to See Morning

The overseer slapped the quiet slave woman, and he didn’t tea live to see mourning in the shadows of a…

A Mississippi Master Planned His Own Wedding to Enslaved Twins—10 Hours Later, the Inexplicable 1857

Today we’re going back to Mississippi 1857 to a wedding that was planned like a display of power. A master…

Why Mel Brooks Refused to Go to Rob Reiner’s Funeral?

When Romy Reiner called Mel Brooks to invite him to the final memorial service for her parents, he refused immediately….

Rob Reiner’s Funeral, Sally Struthers STUNS The Entire World With Powerful Tribute!

Amid the heavy grief soaked atmosphere of Rob Reiner’s funeral, when everything seemed carefully arranged to pass in orderly sorrow,…

7 Guests That Were Not Invited To Rob Reiner’s Funeral

One week after the horrific tragedy in which Rob Reiner and his wife passed away, Romy and Jake held a…

End of content

No more pages to load