In October of 2012, 26-year-old Jacob Morgan drove out to a lonely campsite in the Black Rock Desert, Nevada.

He was a former Army scout, used to the heat, silence, and isolation.

His friend said that the desert was not a place of escape for him, but a way to learn to breathe again.

That day, he called his sister from a small gas station called Desert Star in Jeroka, saying he was going to take some night photos and would be back on Sunday.

No one saw him again.

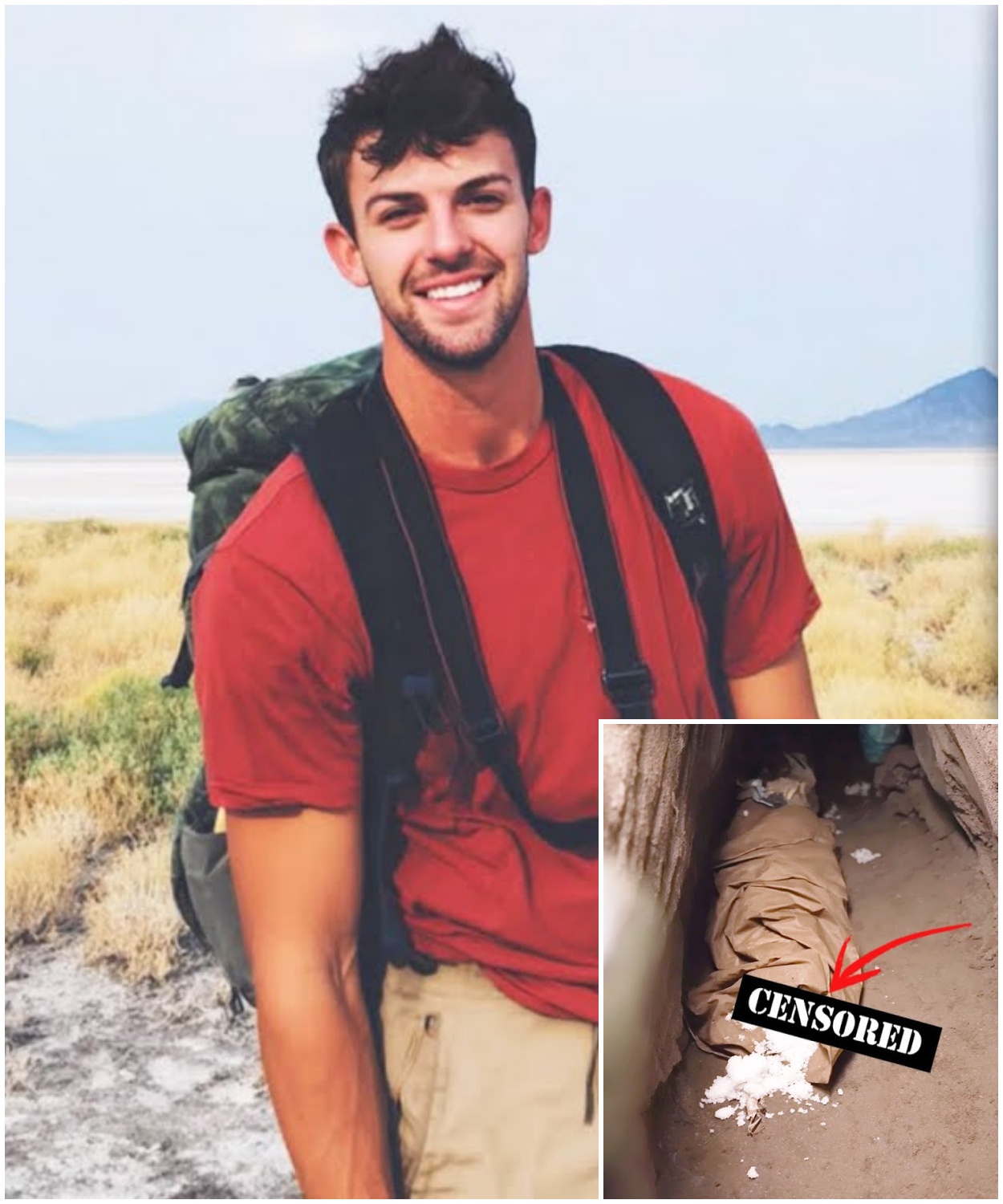

5 years passed and when the owner of an old ranch in Persing County decided to check out an abandoned mine, little did he know that he would come across a bag tied tightly with rope with salt spilling out.

Inside was the body of a man which had been preserved supernaturally well, as if time itself had been afraid to touch it.

On October 12th, 2012, a Friday, Jacob Morgan left his apartment on the southern outskirts of Las Vegas a little after 7 in the morning.

His downstairs neighbor, Mrs.Ramirez, recalled seeing him on the stairs with a backpack, tripod, and camera over his shoulder.

He greeted her, calm, but tired as always.

Then he got into his white Ford Ranger and drove northwest toward the Black Rock Desert.

It was an ordinary start to a day that would be the last time anyone would see him alive.

Jacob was 26.

A former Marine Corps scout, he had been working as a security guard for a private firm since his discharge.

His colleague said he was punctual, calm, almost silent.

One of them, Steven Park, recalled, “When he couldn’t sleep, he would go to the desert.

It was easier for him there.

” For Morgan, these trips were more than just a vacation.

They were part of his therapy, an attempt to tame the memories that haunted him after his service.

At 9:20, he stopped at a Desert Star gas station in the small town of Jericho, 100 miles from Reno.

Surveillance cameras captured him getting out of his pickup truck, filling up the tank, and entering the store.

The video shows him talking to the cashier, a man named Eddie Lambert, who later told police that Morgan was asking about the road conditions and wondering if there was any water nearby.

He bought two bottles, some energy bars, and a map of Persing County.

At 10:00, 45 minutes, Jake called his sister, Jessica Morgan, a nurse in Carson City.

Her words are preserved in the police report.

He said he wanted to take night photos.

He sounded calm, even a little inspired.

I asked if I should take someone with me.

He laughed and said, “No, I need silence.

” That was the last confirmed call from his phone.

After that, the connection was cut off.

That evening, the temperature in the Jeweling Plateau area dropped to 36° F, and the wind from the northwest carried dust and dry grass seeds.

A gray wall of clouds rose on the horizon, covering the sun after 4:00.

It was there, between the dry stream beds and stone ledges, that Jake intended to spend two nights.

When he didn’t show up on Sunday, his sister thought at first that he was just delayed.

But the next morning, the phone was still silent.

Jessica began calling her brother’s friends, checking hospitals, sheriffs in neighboring counties.

She was told the same thing.

No incidents, no reports of accidents.

3 days later, on October 17th, his pickup truck was found by chance.

A coyote hunter came across the vehicle about 15 mi off the main highway on an old dirt road leading to an abandoned quarry.

The doors were closed, the windows were intact.

The inside was in perfect order.

On the passenger seat was his cell phone turned off due to a dead battery, an empty water bottle, and a detailed map of the region.

A small section of the canyon was circled with a pencil unmarked, just a few dry lines lost in an unremarkable stretch of desert.

The sheriff of Persing County personally arrived at the scene.

The report stated that there were no fingers on the door and the sand around the pickup left only vague footprints.

a few steps from the door and a tread that disappeared toward the hills.

Later, experts determined that it could have been his own gate.

There were no signs of a struggle, no foreign footprints, not a single piece of glass.

The car was parked as if it had been parked according to the rules.

A mechanic who was invited to inspect it confirmed that the fuel was not leaking, the engine was in good working order, and there were no keys in the ignition, which had apparently been taken by the owner.

The tire track showed that the car had driven to the spot on its own without being towed.

It was silence, ordered to the point of absurdity.

The distance to the nearest settlement was over 20 m.

The entire area around was a plane with sparse scrub cut by dry streams and black bands of hardened lava.

In daylight, it seemed endless, and at night it was devoid of any landmarks.

Even experienced rangers sometimes lost their way after sunset.

Later, experts would reconstruct Morgan’s route using surveillance footage and the testimony of several drivers who had seen the white Ford on the highway 48 hours earlier.

All of the testimonies were consistent.

He was driving calmly with no signs of pursuit or malfunction.

Not a single item was found at the scene to explain where he might have gone.

Even the dust on the hood was an even layer, as if the car had been there since the beginning of time.

The official sheriff’s report stated, “The driver left the vehicle voluntarily.

He apparently headed south on foot toward the canyon.

No further route has been established.

” Jessica arrived that evening.

She stood by her brother’s car as the sun sank behind the hills and according to one of the officers, kept repeating one thing.

He wouldn’t have left without his camera.

But the camera was never found.

The desert was silent that day.

There was nothing in it to indicate struggle or fear.

Only absence so pure that it was proof in itself.

When Jacob Morgan’s white pickup truck was found among the sand and rocks, the Persing County Sheriff’s Office gave the family only a brief update.

Vehicle located.

The driver is missing.

Jessica Morgan came to the station that evening.

She demanded official action and at her insistence, a search operation was launched the next day, October 19, 2012.

At 5 in the morning, volunteers gathered on the side of an old dirt road.

10 local residents, two rangers, dog handlers with two dogs, and several employees of the sheriff’s department.

The wind kicked up fine dust and the air smelled of metal and dry grass.

The sun was rising in the east, red and dim, just like the morning Jake had set out on his journey.

The dogs picked up the scent immediately.

They pulled their leashes from the car southward toward the undulating edge of the desert, where the soil turned to a hard plateau.

Jessica walked behind them, holding a photograph of her brother as if she could use it to draw him back.

The trail continued for a little over a mile.

Then the ground changed from sand to a cracked surface with dark patches of basaltt.

The wind blew the dust around, erasing every print.

Where the dogs had lost their scent, only a fragment of red stone remained, where his boot might have once stood.

Then there was silence.

The search leader, Sergeant Mark RWS, said in the report, “The dogs lost the trail suddenly with no gradual weakening, probably due to a change in soil structure or wind.

” But the very next day, while surveying the area, one of the groups came across a small rise with the remains of a fire.

A few dozen yards away, a green tent stood among the stones.

Inside was a sleeping bag, a package of dry rations, a torch burner, and an almost full bottle of water.

Not a single sign of haste or panic.

A Nikon camera with a scratched lens was lying on a rock nearby.

When the technicians looked at the memory card, they found 20 pictures, all taken the night before he disappeared.

The last shot was the strangest.

The starry sky over black rock.

Exposure for several minutes.

The horizon was flat.

The camera was stationary.

No sign of anxiety, just absolute concentration.

The tent stood on a flat spot as if chosen according to the rules of military training.

Protected from the wind not far from a low ledge.

There were no footprints or debris underfoot, just a flat surface that was erased by the wind every day.

Ranger Leane Gray, who was among the first to arrive, recalled, “It didn’t look like an abandoned camp.

It looked like an exhibit.

Nothing was broken.

Nothing was disturbed.

It was just empty.

” Jessica arrives at the camp a day later.

She recognizes her brother’s thermos, his knife, and his folded backpack.

She says that Jake always kept things in perfect order, but this time it looked like he wasn’t going to leave.

The food was unopened.

The batteries in his flashlight were charged.

It looked as if he had just stepped out for a few minutes and never returned.

Over the next few days, the search was expanded to an area of 20 square miles.

Volunteers from Reno, members of the Silver Ridge Search and Rescue Club, and a National Guard team using thermal imaging equipment participated.

During the day, the dust was wallto-wall, and at night, the temperature dropped to about 30° F.

People walked, guided by compasses and the glare of beacons.

On the third day, one of the dog handlers reported that the dog reacted briefly near a dry creek bed, but the scent quickly disappeared.

At that spot, they found only an empty can and a piece of plastic.

Ordinary garbage unrelated to Morgan.

At 9:00 that evening, the sheriff ordered a helicopter to be brought in.

The aerial search lasted 4 days.

From the heights, nothing was visible but a gray plane that shimmerred like the sea.

No tracks, no heat signals.

When two weeks passed, resources began to run out.

The volunteers returned home.

The tents of the search team’s headquarters were rolled up, and at the end of the report, there was only a dry phrase.

No signs of life or death were found.

Further investigation is postponed until new data is available.

Rumors began to spread among the locals.

Some said they saw flashes of light at night in the direction of Juling’s plateau.

Others claimed to have seen smoke on the horizon that neither the rangers nor meteorologists could explain, but checks did not confirm either account.

Jessica stayed near the spot where the camp was found for several more days.

She brought water, put a candle near the stone where the camera was lying.

When asked to return to the city, she said only, “He is not lost.

He just didn’t come back.

On October 28th, the sheriff’s department officially classified the case as a missing person.

All the materials, the camera, the map, the dog handlers reports were transferred to the archive as evidence.

The desert became empty again, the way it had always been.

And every time the wind kicked up dust over the dry riverbed, it carried it in the same direction to where the trail had broken off.

A month has passed since the search for Jacob Morgan was officially stopped.

The Black Rock Desert was once again silent.

The same silence that swallows up every sound, even footsteps.

The case seemed to be fading away like hundreds of others.

But in mid- November, the Persing County Sheriff’s Department was approached by a man named William Cole, a trucker who had been driving through a remote stretch of Highway 447 that week.

His testimony seemed insignificant, but it reopened a trail that no one had expected to find.

According to Cole, on the night of October 12th, when Jake disappeared, he was driving from Reno to Love Lock.

Around 11:00 in the evening, in the area between two abandoned farms, he saw a strange light.

At first, he thought it was the headlights of a car on the side of the road.

But when he drove closer, he realized that the light was not coming from the headlights, but from a pocket flashlight.

It was being held by a man whose silhouette was flashing in the darkness next to a dark SUV parked next to an old agricultural machinery shed.

The car was parked with no lights on and according to the driver, looked like it was hidden.

Cole did not stop.

He drove by and only remembered that the car was dark in color, possibly black or navy blue with a shine on the rear fender that could have been a scratch mark or a reflection of moonlight.

Later, when the news reported that a man had gone missing in the area, he decided to report what he had seen.

His testimony was officially recorded and passed on to Detective John Reigns, who was in charge of Morgan’s case.

The next day, two officers went to the site.

The distance from the highway to the hangar was less than half a mile, but the path was difficult, overgrown with wormwood and covered with fragments of old boards.

The hangar stood alone in the middle of the plane with a rusted roof and a door that someone had once tried to close by nailing it shut.

It was dark and quiet inside with only the wind humming through the cracks.

The inspection report reads, “The room is empty.

There is a thick layer of dust on the floor with several surface disturbances similar to traces of dragging.

There are no objects that could be material evidence.

There is a pungent odor of bleach and a chemical solution of unknown origin.

Detective Reigns described the odor as too fresh for an abandoned place.

It was as if someone had recently tried to wash the floor, wipe everything down, and did it thoroughly.

They found clumps of dark liquid on the iron wall where the drag trail ended.

A preliminary test showed that it was not blood, but possibly grease or traces of brine used to clean metal.

The next day, forensic experts arrived at the site.

They took dust samples and searched the area.

They found only a few old canisters, a ruined tire, and an empty bottle of disinfectant.

Not a single document, fingerprint, or object that could link the hanger to Jake Morgan’s disappearance.

Despite this, the place looked too fresh.

The dust in the center of the room was stirred up, as if something had been moved recently.

In one of the corners was a metal barrel without a lid, with a layer of water inside with a white sediment on the bottom.

Later, laboratory analysis showed chlorides and microparticles of salt in the samples.

The experts conclusion sounded cautious.

It is possible that the premises could be used for short-term storage of materials or processing of substances of unknown type.

Reigns tried to identify the owner of the land.

According to the documents, the land belonged to Desertgate Investments, a company registered in the Cayman Islands.

Its address turned out to be fictitious and its phone number was inactive.

State archives contained no real contacts, only a post office box in Virginia, which according to postal workers had not been visited for several years.

Meanwhile, the department continued to check.

They checked vehicle registries that might match the trucker’s description.

A dark SUV with no license plates, possibly an old Chevy Tahoe or Ford Expedition.

The result was zero.

No vehicles matching that description and registered in Persing or Humbult counties were found in the databases.

Detectives interviewed several local residents.

One farmer who lived 5 mi from the highway said he heard an engine noise around midnight that night, but thought it was hunters.

Another witness, the owner of a small gas station 20 m to the south, said he had seen a dark car earlier that evening.

The driver paid in cash without getting out of the car.

The surveillance cameras were faulty and no face or license plate could be recovered.

Over the next weeks, they analyzed everything they could.

Dust samples, liquid residue, even cobwebs from the corners of the hanger.

Everything was inconclusive.

The only thing the labs confirmed was that there were indeed traces of chemicals in the air that could have been used to clean the surfaces.

When officers returned to the site in December, they noticed that someone had opened the hangar door.

Fresh tire tracks led from the road directly to the entrance.

No new objects had appeared inside, but the smell of chlorine had disappeared, leaving only a salty taste in the air.

It seemed that someone was still coming here, not to hide, but to erase the past.

Sheriff RS wrote briefly in his report.

The object may be related to Morgan’s disappearance, but the evidence is insufficient.

Unknown persons may be using the premises for activities not directly related to the crime.

For Jessica, the report was a new blow.

She arrived at the hangar on her own without waiting for police permission.

She stood at the entrance, breathing in the pungent smell of metal and dust, and said only one thing to reporters.

If he was here, he was erased.

so we would never know.

After that, the investigation slowed down again.

Investigators no longer had any eyewitnesses or new evidence.

The SUV was never found, and the company that owned the land was declared fictitious.

Every detail that at first seemed like a breakthrough turned out to be false.

In January of the following year, Morgan’s case was again archived, but now it had a new stamp.

probable involvement of unidentified persons.

The desert was silent as if it had always known the truth, but was not going to give it away.

And only the wind that wandered around the abandoned hanger sometimes brought with it the same smell of chlorine, which reminded us that someone had been there.

Years passed.

By the fall of 2015, the case of Jacob Morgan’s disappearance had finally disappeared from the news.

The police archives kept it under a number that said little even to the detectives themselves.

There were hundreds of cases like it on the shelves, all similar.

Adult male, dessert, unknown circumstances.

Each of them had its own silence.

Jake’s silence was dry, sunburned, and smelled like salt.

In Persing County, life went on.

New roads, new developments, new tourists who came to the Burning Man Festival, not even realizing that a few dozen miles to the south, the desert had once claimed a man without a trace.

Only one woman wouldn’t let go of the past.

Jessica Morgan, his sister, quit her job at the clinic 2 years after her brother disappeared.

Local newspaper reports say she sold her apartment in Carson City, bought an old truck, and moved into a small motel off of Highway 447.

From there, every morning she would go to the surrounding towns, Gerlac, Lovelock, Winnamaka to postcards with her brother’s portrait.

The photo was the same as the first year of the search.

Jake in the desert with a camera around his neck, smiling with a slight squint.

Below the picture was a short inscription.

Disappeared in October 2012.

If you saw something, call us.

There is an entry about her in the police records.

Woman is persistent, emotionally unstable, continues her own investigation without official permission.

For the authorities, she became a problem.

For the locals, she became part of the landscape.

She was seen in coffee shops, near bus stops, on roadsides.

Sometimes she stood there for hours looking at the horizon where the same endless plane where her brother disappeared began.

In 2016, Jessica established a small foundation named after Jacob Morgan.

Its purpose was to finance search operations and help the families of those who disappeared in the desert.

The registration document was signed by her own hand, slanted handwriting, uneven letters.

The money came from private donations and her own savings.

In total, a little over $20,000.

This was enough to rent a drone, pay for a private investigator, and fuel for endless trips.

The private investigator, a former police officer named Douglas Neil, spent several months in the region.

He checked the old coordinates of the camp, the location of the car, even the hanger that once aroused suspicion.

In a report dated April 2017, he wrote, “No signs of a crime were found.

The desert has erased everything.

” Jessica did not accept these findings and fired Neil.

Meanwhile, strange stories began to emerge among the locals.

Stories circulated in hunting camps and among truck drivers about unknown people who were sometimes seen at night near dried up streams and old mines.

They were called shadow fishers.

According to legend, they came out only after sunset, wore masks or hoods, and did not talk to strangers.

The lights of their lanterns could be seen at a great distance as if they were catching light rather than fish.

No one could say whether they were homeless, smugglers, or just the imagination of those who had been staring into the darkness for too long.

But it was with these rumors that many began to associate the story of Jacob Morgan.

In a newspaper column for May 2016, a journalist for the local Nevada Gazette wrote, “They say the desert is home to those who don’t want to be found.

Sometimes they take those who come too close with them.

” For Jessica, these legends were both a hope and a curse.

She didn’t believe in mysticism, but every time she heard about the mysterious lanterns, she went to the place where they were seen.

According to eyewitnesses, she would leave the motel in the middle of the night and drive into the desert alone.

Several times, her car was found stuck in the sand, tens of miles off the road.

The doctor she occasionally visited in Lovelock noted in her medical records signs of exhaustion, insomnia, emotional dependence on the topic of her brother’s disappearance.

Patient denies need for treatment, but no document could describe what her life had become.

By the middle of 2017, her fund was practically empty.

She sold her car and began living in an old trailer parked just off the road leading to Black Rock.

Inside were several boxes with newspaper clippings, copies of police reports, and photos of the places where her brother was last seen.

On the wall was a calendar with red markers marking the dates of other disappearances of tourists in Nevada over the past decade.

Jessica believed that all these stories were connected.

She wrote letters to neighboring county departments requesting that the cases be consolidated, but either no responses were received or a standardized phrase was used.

There are no grounds for merger.

Her letters became shorter but increasingly harsh.

The volunteers who had once helped her gradually withdrew.

One of them, Ronald Gibbs, recalled in an interview, “At a certain point, she stopped looking for a body.

She was looking for meaning.

” and that was more frightening than the desert itself.

In the fall of that year, Jessica was seen for the last time in the town of Gerlock.

She was standing by a bulletin board exchanging an old flyer for a new one.

When asked by a journalist why she continued, she replied, “Because silence is also a witness.

It must be made to speak.

” Since then, her life has been a chronicle of waiting.

She drove the same road every day, stopping at the exact spot where the pickup truck was found.

She would sit on the hood and stare for a long time in the direction of the plateau, as if hoping to see a figure coming towards her.

The desert did not answer.

It never answers.

But sometimes when the wind picked up at night, you could hear something that sounded like footsteps.

Short, rhythmic, like the echo of a person still walking.

In the early summer of 2017, a farmer named Henry Caldwell decided to sell some of his land, a remote stretch of desert that he had never used.

It lay 30 mi from his ranch, closer to old abandoned quaries where bentonite clay had once been mined.

The land was dry, infertile, riddled with cracks, and no one had lived or grazed there since the ranch’s existence.

Caldwell was just paying taxes with no profit or benefit from the land.

The potential buyer was an investor from Reno who was looking for a place to install solar panels.

He asked for permission to inspect the site in person to check the soil condition and road accessibility.

Caldwell agreed and gave him a key to an old gate that led to the northern edge of the site.

According to him, it was just a formality.

There’s nothing there but dust and rocks.

3 days later, the buyer returned unexpectedly excited.

He said that he had found something strange near one of the ravines, a half-failed mine covered with a piece of tarpollen and a pile of empty bags with industrial markings.

All of them had the logo of the Basin Salt and Chemical Company.

One of them, he said, had a date stamp on it, almost erased by the sand, something like October 2012.

He took some photos and showed them to the farmer.

The pictures showed a dry entrance to the attitially covered with dust and several bags near it, crumpled, but not yet completely destroyed.

The tarpollen that covered them was colored and spotted, similar to those used by construction workers for temporary shelters.

One edge of the tarp fluttered in the wind, leaving the impression that someone had left the place in a hurry without taking their belongings.

Caldwell didn’t think much of it at first.

In Nevada, such finds are not uncommon.

Old mines, debris from drilling companies, sometimes barrels with traces of chemicals.

But the thought that there might be an unauthorized dump on his land alarmed him.

He realized that if the environmental inspection found something toxic, he would be the one to answer.

That evening, he called the sheriff’s office in Lovelock and reported possible industrial waste on his property.

His call was recorded as a routine citizens complaint, not marked urgent.

He sent photos taken by a customer and a brief description of the site.

The report stated, “There are no visible traces of hazardous substances, probably the remains of previous drilling operations.

Please conduct an inspection to avoid legal consequences.

” According to Caldwell himself, at the time, he just wanted to close the issue.

It was not the bags that worried him, but the paperwork.

The sale agreement stated that the buyer had the right to withdraw if he found any traces of contamination on the site and even a few bags of chemical salt could be a reason to cancel the deal.

Several weeks passed after the appeal.

He received no response from the sheriff’s office.

Only at the end of July did an assistant, a young officer, come to see him and write a short report.

He noted that a full inspection would require the involvement of the Department of Environmental Protection and advised him not to touch anything on the site for now.

From Caldwell’s recollection, he said that if those bags were just salt, it wasn’t a crime, but if they were chemicals, it was a matter for the environmental department, so it’s better to leave it alone.

After that, the farmer decided to do his own check.

In early August, he went to the mine himself again.

The sun was high.

The temperature was over 100° F.

The air was thick and bitter with dust.

As he approached the place, he immediately smelled a subtle odor of metal and something salty, the kind of smell you get near dried up lakes where salt crystals settle on the rocks.

There were five or six sacks in varying degrees of wear and tear.

One was torn and small white granules scattered on the ground, forming a thin, shiny layer.

When Caldwell ran his finger over it, crystallin dust remained on his skin.

He tried to rub it and made sure that it was indeed ordinary salt, odorless, without impurities.

Next to the sacks, he noticed a metal pin sticking out of the ground, as if someone had once used it as a tent pole.

The tarpollen itself was better preserved than could be expected in these conditions.

The fabric had not completely faded.

The edges were only slightly frayed.

It seemed that it had been lying here for no more than a few years.

The mine that led to this makeshift camp was small, a narrow opening in the rock that sloped down at an angle for about a few dozen feet.

It was chilly inside and damp.

Caldwell didn’t dare go any deeper.

The ground seemed unstable and every step echoed under his feet.

He took a few pictures on his phone, the entrance, the bags, part of the inner passage, and returned to the car.

The same day, he sent new photos to the sheriff’s office again, adding a short comment.

Maybe people who used the mine a few years ago left something here.

No hazard is apparent, but I’d like to request an official inspection to confirm the area is clean.

For Caldwell, it remained a simple bureaucratic procedure.

He needed to have the certificate to close the deal.

He had no idea that a simple report of garbage on a deserted site would be the first step in reopening a case that had been forgotten for 5 years.

When he recalled that day later, he said, “Everything looked strangely organized, as if someone had stacked those bags neatly in a line, and only one was heavy, dense.

I thought it was just wet clay inside.

” At the time, it didn’t even occur to me that it could be something else.

The photographs were filed under a standard number and remained there for almost a month until the department decided to officially check them.

In the meantime, the silence of the desert held its own again.

The calm, boundless, deceptive silence that always precedes discoveries that change everything.

In early September of 2017, the Persing County Sheriff’s Office finally responded to a call from Farmer Henry Caldwell.

His report of suspicious garbage had been in the system for almost a month before it reached Captain Alan Graves, who was in charge of unauthorized waste cases.

At the time, no one imagined that a routine environmental inspection would turn into one of the most eerie finds in the county’s history.

On September 11th, a team of three officers and two inspectors arrived at the site, accompanied by Caldwell himself, who showed them the way to the mine.

According to the official report, the temperature that day reached 102° F.

The sky was cloudless and the wind was minimal.

At first glance, the place did not seem to pose any danger.

A desert covered with sparse shrubbery and a narrow ravine leading to the dilapidated entrance to the old Adite.

Deputy Daniel Frost was the first to descend.

He described what he saw later in his report.

At the entrance, there are several empty bags labeled basin salt and chemical and a piece of tarpollen next to it.

It’s dark inside, but consistently cool.

The smell is faint, similar to metal.

The inspectors decided to conduct a visual inspection and take pictures of the area to draw up a report for the environmental department.

The attit was narrow, about 50 ft long, with a low ceiling supported in several places by old wooden beams.

The light of the lanterns carved salt crystals from the wall, glistening in the dark.

On the first 10 ft were the same sacks Caldwell had previously reported.

They were empty, crumpled, but relatively new.

Frost checked them again and was about to leave when one of the inspectors noticed that something darker, like a shadow, was visible behind the pile of bags.

When they got closer, it turned out to be another sack, but a bigger, denser, and heavier one.

Its edges were stained with brown dust, and the rope that tied it was darkened by time, but held tight.

The report states, “The object is different from the rest.

The appearance is older.

The surface is partially hardened.

When attempting to move it, a considerable weight of approximately 50 to 70 lb was detected.

The bag makes a dull sound, similar to grain being poured.

The officers decided to open it on the spot to make sure there were no toxic substances inside.

To do this, they used a pen knife.

When the blade cut through the coarse fabric, white crumbs slowly fell out of the cut.

It fell like sand, but immediately crystallized in the light.

Someone suggested that it was ordinary table salt.

However, the next movement of the knife exposed something darker.

Under the layer of salt, a piece of fabric similar to a sleeve was visible.

Frost knelt down and widened the hole.

At first, what appeared under the flashlight was mistaken for a mannequin or an old jumpsuit.

But a few seconds later, it became clear it was a human body.

It was terribly preserved, partially mummified, covered with a dense layer of salt that covered the skin and clothes like a crystalline crust.

The inspectors retreated.

One of them later recalled that the smell was not pungent.

On the contrary, the air smelled dry as if it were a room where no one had lived for years.

The body was rolled up face down, hands clasped to his chest.

The rope that tied the bag had cut through the layers of fabric, leaving deep dents in the surface.

Frost immediately contacted the department.

2 hours later, a medical examiner and forensic scientists from Reno arrived at the scene.

They taped off the mine and began to document every inch of it.

The photos taken that day were later included in the case file, showing a torn bag, spilled salt, and a dark figure emerging from it like a rock.

The experts worked all night.

The body was carefully removed so as not to damage the preserved tissue.

The salt that surrounded it acted as a natural preservative.

It dried out the soft tissues, preventing decay.

The report of the medical examiner, Dorothy Lang, states, “The body is partially mummified, the facial shape is stable, and the limbs are intact.

The probable cause is prolonged exposure to an environment with a high concentration of sodium.

During the initial examination, the remains of clothing were found.

Khaki jeans, a fleece jacket, and fragments of rubber sold shoes.

On his left hand was a metal watch that stopped at 337.

In his pocket was a fragment of a plastic card where part of the name could still be recognized.

Morgan.

After the body was recovered, it was taken to the Wo County Laboratory.

There, experts conducted a comparative analysis of dental records and old medical records.

A day later, it was confirmed that the remains belonged to Jacob Morgan, who disappeared 5 years ago in the same desert.

The report sent to the state’s attorney stated, “Death was due to undetermined circumstances.

There were no obvious signs of violence on the body.

The high concentration of salt in the tissues indicates an artificially created preservation environment.

In other words, the body did not just end up in salt by accident.

Someone had deliberately covered it to preserve it.

When the news reached Jessica Morgan, the journalists recorded her only phrase.

I knew the desert doesn’t take for granted.

For the police, however, the discovery meant something else entirely.

The case that had been labeled missing for years had officially become a murder case.

That evening, the sheriff’s office prepared a short press release.

Human remains have been found on the grounds of a former mine tentatively identified as Jacob Morgan who disappeared in October of 2012.

The circumstances of the death are being established.

The investigation is ongoing.

New trips have begun in the Black Rock Desert.

Every crumb of salt, every fragment of the bag was now considered as evidence.

And amidst the endless silence, where even the wind sounded deaf, a new criminal investigation began.

One that finally had a body, but no answer as to who it was.

After Jacob Morgan’s body was officially identified, the case was instantly prioritized.

The Persing County Sheriff’s Office turned the investigation over to the State Department.

Reno forensic scientists, experts from the Federal Bureau, and several experienced detectives who specialized in old unsolved cases joined the search.

5 years of silence were about to be broken with evidence, a crime scene, and most importantly, a material trail.

The first thing that caught the investigator’s attention were the bags with the Basin Salt and Chemical logo.

The photos taken in the mine clearly showed batchmarks and the remnants of the date.

October 2012, the very month Jacob disappeared.

The producer was located in an industrial area 30 mi from Reno and specialized in supplying industrial salt to the chemical and food industries.

In the second half of September, a group of detectives arrived at the company.

The head of the company, Thomas Willard, received them in a small office that smelled of grease and metal.

He confirmed that the products in question were indeed manufactured in the fall of 2012.

The internal reports showed a small shortage of about two dozen bags missing from the warehouse.

The theft was not investigated at the time.

The security guards decided that it was a miscalculation or an incorrect write-off of the goods.

The detectives asked for archival data for that period, camera footage, visitor logs, and personnel records.

Some of the materials had already been lost, but among the old paper reports, they came across a short memo from a security guard dated October 10th, 2012.

It mentioned a technical employee of the collection service who allegedly came to check the alarm system and surveillance cameras.

No surname was given, only a description of the car, a dark van with white stripes.

This episode attracted special attention.

Detectives found that no official collection service had scheduled inspections at the facility that day.

So, someone used the uniform and the legend to get inside.

A former warehouse worker, a veteran named Vernon Taylor, agreed to testify.

His story is preserved in the record.

The man had an ID.

It looked real.

Gray overalls, a vest with reflectors, even a badge with the Nevada cash transport emblem.

He was not asking about the alarm system, but about the layout of the exits and loading docks.

I thought he was a new technician.

Then he went out into the backyard supposedly to check the sensors and was never seen again.

A few days later, Taylor said during a regular inventory, it turned out that the same bags of salt were missing.

At the time, it was attributed to negligence.

One of the loaders did not keep the records correctly.

But now, this small detail has acquired a different meaning.

Someone was preparing for the crime in advance, knowing where and what to take.

Forensic psychology experts have drawn up a preliminary profile of the unknown.

The person who planned everything.

so carefully had to be technically trained, cautious with experience in security or logistics.

He or she understood how warehouses work, what security systems are installed there, and how they can be bypassed.

Investigators assumed that it could have been a person associated with private security companies, possibly a former military officer or an employee of a cash collection company.

With this version, the police turned to the databases of Nevada and California.

They were looking for people who had worked for private security agencies in 2012 and had quit shortly after October.

There were no results, but among the hundreds of entries, several names came up that matched the description given by witness Taylor.

middle-aged man, blonde hair, shortcropped, about 6 feet tall, spoke calmly, almost in an official tone.

One of the detectives, Sam Gardner, later noted in a report, “His demeanor was indicative of cold preparation.

” The man knew what he was doing.

“Sealing salt and using it to preserve a body is not an impulse, it’s a method.

” Basin Salt and Chemical provided the police with a list of all customers who had received products from the same batch at the time.

Among them were farms, food factories, and suppliers of technical reagents.

No connection to Morgan or his family was found anywhere.

So, the investigation returned to the main question.

Who and why could have stolen dozens of bags of salt? In October of 2012, the operatives checked the supply routes.

It turned out that the warehouse was located 30 miles from Highway 447, the same highway Jacob Morgan was traveling on that evening.

For an experienced logistician or security guard, this coincidence could not have been accidental.

The department began to create a new profile of the criminal.

He was described as a person capable of long-term planning, meticulous, and without emotional outbursts.

Such a killer leaves no stone unturned, preparing tools, a place, and even materials in advance.

Investigators had no doubt that the person who left Morgan’s body in the salt was not acting for the first time.

To test this theory, the police turned to the interstate database of unsolved cases.

They were interested in cases where non-standard methods of concealing the body were used, preservation, chemical treatment, or artificial drying.

The analysis showed several episodes in Utah, Colorado, and Arizona, but none had a direct connection.

However, the mere coincidence of methods was alarming.

In an internal report, Captain Graves summarized, “The suspect is systematic.

He has logistics, security, or military training.

Uses professional cover.

Motives unknown.

This does not appear to be a spontaneous killing.

He probably did it before.

That same week, police sent formal inquiries to all security companies that had operated in Nevada 5 years earlier.

Most of the reports were standard, but a few matches to Taylor’s description led detectives to continue their investigation.

One of the names was a former employee of a security firm in Reno who quit at the end of 2012, citing personal reasons on his application.

His whereabouts remained unknown.

Morgan’s case was officially transferred to the section murder with special preparation.

For the sheriff, this was confirmation that they were not dealing with a random crime, but with a wellplanned operation.

The silence that had surrounded the case for 5 years now gave way to the noise of typewriters, calls, and inquiries.

But there was still no answer.

Almost 12 months had passed since Jacob Morgan’s body was recovered from a mine in the Black Rockck Desert.

The investigation, which at first seemed to be a breakthrough, gradually turned into a chronicle of setbacks.

Detectives had bags of salt, photographs of the site, inspection reports, and profiles of suspects.

But they didn’t have the most important thing, the man who did it all.

Police reports for that year were full of dates and requests.

The search for the so-called cash collector spanned three states.

They checked the archives of security firms, lists of contractors, former military personnel, and technicians who could have worked undercover.

All the results repeated the same thing.

There were no matches.

It turned out that the man who had managed to enter the warehouse and steal a shipment of salt 5 years ago had disappeared as completely as Jake had.

Detective Sam Gardner wrote in his report, “The suspect is cautious, leaves minimal trace, and does not use electronic channels, probably lives under a different name, or has changed states.

” But even this conclusion was only an assumption.

With no fingerprints, no photo, no car, the police had nothing to go on.

At the end of the summer of 2018, the investigation team was downsized.

The last active request was to check the former employees of Nevada Cash Transport, the company whose uniform the unknown man wore.

Among more than a hundred names, none matched Vernon Taylor’s description.

Two of the witnesses who saw the cash collector that day had already died by then.

The third, Taylor himself, was living in a veteran’s home in Reno, and according to the staff, had begun to lose his memory.

His new testimony contradicted his previous one, saying that the man might not have been wearing a collection uniform, but rather a security guard’s overalls.

When the investigators contacted Basin Salt and Chemical again, the management said that after the incident in 2012, the accounting had changed and all the old documents had been destroyed.

The warehouses were rebuilt and the video surveillance systems were updated.

Only pages in the police archives remain of that past.

At a departmental meeting in November of that year, Morgan’s case was officially transferred to the category of unsolved murder.

Formally, it was left open so that it could be reopened in the event of new evidence, but the active phase of the investigation was over.

Since then, Jacob Morgan’s file has been kept in a dark drawer in the archives alongside hundreds of other cases that lack a final answer.

For Jessica Morgan, that moment was a watershed.

She received a call from the department in December, and the only thing she was told was the date of release of her brother’s remains.

A few weeks later, she traveled to Reno to pick him up.

The ern handed to her by the medical examiner contained desiccated bones preserved by the very mineral that was once supposed to hide the crime.

The funeral was held without the presence of the press with only a few people in attendance.

Old volunteers who had once helped with the search.

The priest read a short prayer, but Jessica remained silent.

Then, according to eyewitness accounts, she left the ern on the grave mound and said only one thing.

He came home.

After that, she tried to start a new life.

She returned to Carson City, got a job as a nurse in a small clinic, and rented an apartment on the outskirts of town.

But every night, according to her co-workers, she stayed on shift longer than necessary, as if she didn’t want to go home.

Over time, she began to visit the places where it all began, the Desert Star gas station in Grocha, where Jake last called.

The cashier, who still works there today, recalls, “She would come in a few times a year.

She would stand by the window, drink coffee, and look out at the road.

She didn’t ask anything, just watched.

Sometimes Jessica was seen on the side of the highway 447 at the very turn where the road to the desert begins.

She would leave plastic water bottles and solar powered lamps there.

For some people it was a strange ritual, but for her it was a way to talk to her brother.

Officially the police continue to keep the case open.

Every year a short line appears in the reports.

No new evidence has been received.

No suspect has been identified.

But between these dry words, there is a silence that is deeper than any explanation.

The detectives who worked on the case are still convinced that this was not the first time the cash collector acted.

Some believe that he lives somewhere nearby, may have changed his name, or may be working undercover again.

Others believe he left the state long ago, disappearing into the endless roads that crisscrossed Nevada like scars on its surface.

For Jessica, it didn’t matter.

She wasn’t looking for him anymore.

She knew that the desert had closed in again, just as it had 5 years ago when it swallowed her brother.

And every time the wind blew dust over the highway, she thought it was not dust, but a trail.

The same one that leads to nowhere, where everything disappears without a trace and silence becomes the only witness again.

News

Ilhan Omar ‘PLANS TO FLEE’…. as FBI Questions $30 MILLION NET WORTH

So, while Bavino is cracking down in Minnesota, House Republicans turning the heat up on Ilhan Omar. They want to…

FBI & ICE Raid Walz & Mayor’s Properties In Minnesota LINKED To Somali Fentanyl Network

IC and the FBI move on Minnesota, touching the offices of Governor Tim Walls and the state’s biggest mayors as…

FBI RAIDS Massive LA Taxi Empire – You Won’t Believe What They Found Inside!

On a Tuesday morning, the dispatch radios in hundreds of Los Angeles taxi cabs suddenly stopped playing route assignments. Instead,…

Brandon Frugal Finally Revealed What Forced Production to Halt in Season 7 of Skinwalker Ranch….

The Secret of Skinwalker Ranch became History Channel’s biggest hit. Six successful seasons documenting the unknown with real science and…

1 MINUTE AGO: What FBI Found In Hulk Hogan’s Mansion Will Leave You Shocked….

The FBI didn’t plan to walk into a media firestorm, but the moment agents stepped into Hulk Hogan’s Clearwater mansion,…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage… It started like any other evening…

End of content

No more pages to load