It was the last weekend of July 2003, one of those Tennessee summers that clung heavy in the air, thick with cicas and the smell of pine.

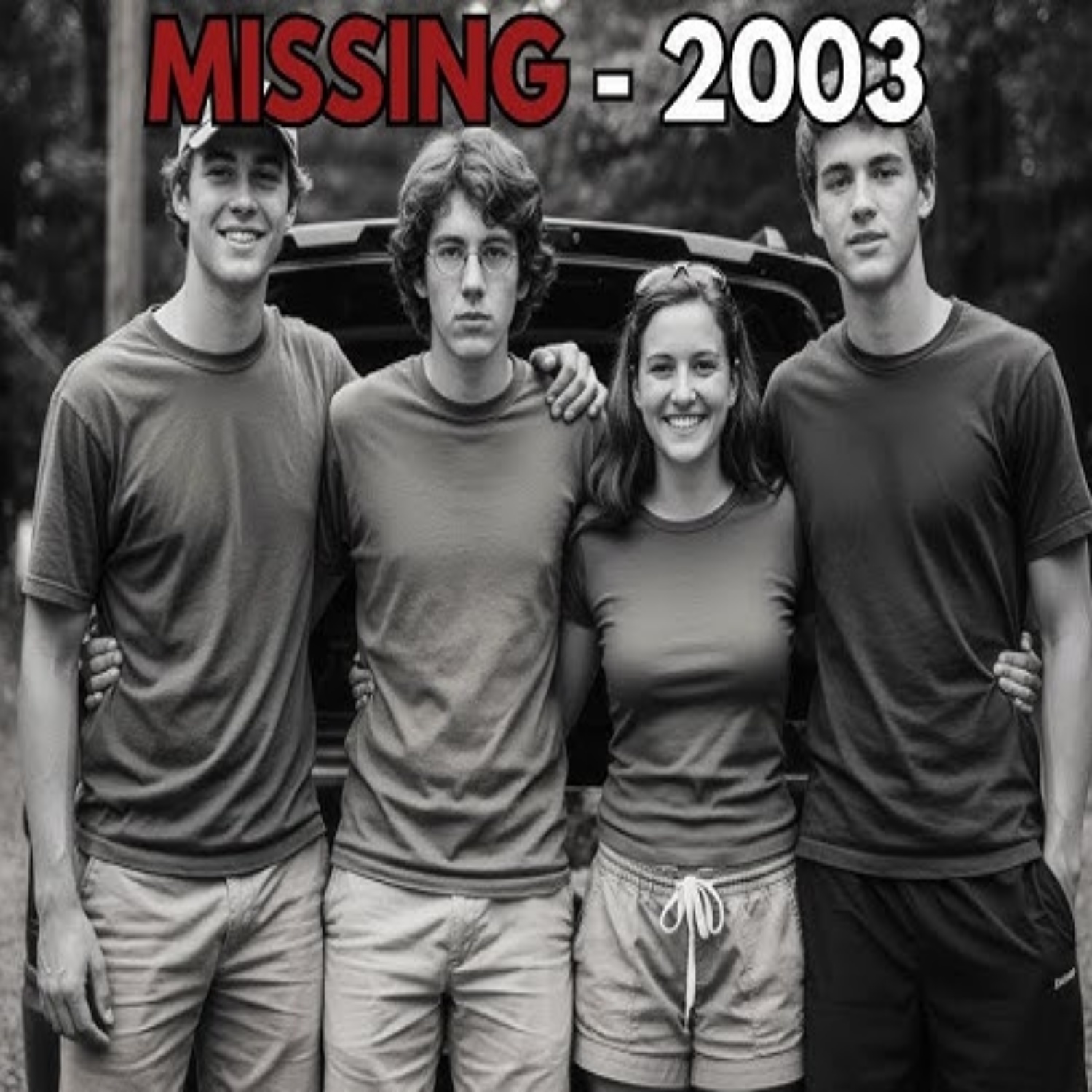

The four cousins had been planning this trip for months.

They’d grown up together, just a few miles apart, spending summers fishing in the same creeks, playing in their grandparents old barn, and sneaking off to Red Hollow to camp when they were younger.

This trip was supposed to be their sendoff a final weekend before life began to pull them in different directions.

Josh, the oldest at 19, had just bought a used SUV and was headed to college in Knoxville that fall.

His younger brother, Ryan, was 17, quiet and bookish.

Their cousins, Amy and Caleb, 15 and 18, rounded out the group.

The plan was simple.

Two nights of camping near the ridge, the same spot their grandfather used to hunt decades earlier.

That Friday afternoon, a clerk at the only gas station on Route 19 remembered them stopping by.

They bought firewood, bottled water, and a disposable camera.

Security footage would later confirm the time.

5:46 p.m.

The cousins looked relaxed, laughing, teasing each other about who forgot the matches.

There was nothing out of place about it.

nothing that would suggest it would be the last time anyone would see them alive.

By Saturday evening, rain rolled unexpectedly over the hills.

The forecast had called for clear skies, but locals remembered the temperature dropping suddenly and fog settling thick along the low roads.

A farmer driving home that night told police later that he’d heard metallic noises echoing from the ridge, something that sounded like a chain dragging or a piece of sheet metal banging in the wind.

He thought it was odd but didn’t think much of it.

When the cousins didn’t return Sunday evening, their families began to worry.

By dawn Monday, the unease had turned to fear.

Phone calls went unanswered.

The only message anyone received came from Ryan’s phone.

A half second of static before the line cut.

By midday, both families drove out to the trail head off County Road 214, where Josh’s SUV was found parked just beyond the gravel turnoff.

The keys were still in the ignition, doors locked.

Deputies from the Monroe County Sheriff’s Office arrived within the hour.

What they found inside the vehicle immediately struck them as strange.

There were no visible signs of struggle.

The back seats were folded down to make room for gear, sleeping bags, a cooler, and a first aid kit neatly tucked against the side, but there were no fingerprints on the door handles or interior surfaces.

None except Josh’s, the driver.

It looked as if the vehicle had been wiped clean.

Even the smudges on the inside glass had been cleared away, leaving a faint streaky shine.

Following tire impressions and footprints, searchers located a small clearing about half a mile from the car.

There, the cousin’s campsite looked half finishedish.

As though they just arrived or were packing to leave, a tent lay unrolled but never staked down.

A few cans of food sat unopened in a plastic bag.

The small fire ring contained only damp wood, not even partially burned.

On a nearby rock, had an old flip phone, its screen still glowing weakly, emitting a low hiss of static through the speaker.

It was an unsettling sight, like someone had set the scene intentionally, but never inhabited it.

Sheriff’s deputies cordoned off the site and began their initial sweep.

The ground was wet from the previous night’s rain, but the search dogs couldn’t pick up a trail beyond 200 yd in any direction.

The scent dissipated abruptly, as if the group had simply vanished into the mist.

The first theory was the most hopeful.

They’d gotten lost.

The terrain around Red Hollow was dense and unforgiving.

Steep drops, hidden ravines, and thick brush that could easily disorient even seasoned hikers.

Search teams fanned out, marking the area with flagging tape, shouting names into the fog.

Helicopters circled overhead, their spotlights cutting through the gray haze.

but no movement was seen below.

By that evening, more than 30 volunteers joined the effort, including several relatives.

Amy’s father walked the creek bed until dark, calling her name until his voice gave out.

At the edge of the ridge, deputies found something small but chilling.

A folded piece of notebook paper soaked through, pressed into the mud.

Only two words were still legible.

Southpath, it was impossible to tell who had written it or when.

Investigators collected the note and sent it for testing, though the rain had washed away any fingerprints.

Meanwhile, weather reports showed an unexpected cold front had swept through the area that Saturday night, dropping temperatures into the low 40s, unseasonably cold for late July.

That might explain the fog, but it didn’t explain why four young people with gear and flashlights could disappear without leaving so much as a shoe print beyond their camp.

The following day, deputies widened their search radius to 2 mi.

They found a section of barbed wire fencing partly collapsed, leading toward an overgrown trail not marked on any of the park maps.

According to county records, the path once led toward an old logging operation that had been abandoned in the 1,980 seconds.

It was roughly in the same direction the note had pointed.

Searchers followed it as far as they could, but the trail ended abruptly at a washedout gully filled with slick red mud and broken branches.

When word of the disappearance spread, volunteers began arriving from nearby towns, the sheriff’s office set up a command post at the trail head.

Over the next 48 hours, they covered more than 10 square miles of forest.

Drones, cadaavver dogs, and even state search and rescue teams joined the effort.

Nothing turned up.

Not a shred of clothing, no scraps of food wrappers, not even a dropped flashlight.

Reporters started calling it the red hollow mystery.

Local news ran footage of the family standing near the SUV, faces drawn and pale, voices trembling as they begged for help.

At one point, a journalist asked the sheriff if foul play was suspected.

He paused before answering.

“We’re keeping all options open,” he said.

But the truth was, investigators had already begun to feel something was wrong.

Late that week, a crime scene technician re-examined the SUV under blacklight and found a faint trace of something along the inside of the rear door streaks consistent with latex gloves.

Whoever had been inside that car after it was parked had taken care not to leave behind a single trace.

That detail changed everything.

The missing person’s report shifted toward a possible abduction or staged disappearance.

But how? No signs of struggle, no tire tracks from another vehicle.

The area was isolated miles from the nearest house or farm.

For someone to intercept the group unnoticed, would have required precision or luck.

As the sun set over Red Hollow that sixth night, fog rolled back in, thicker than before.

Searchers described hearing faint metallic noises again, soft, rhythmic, almost like tapping.

Some brushed it off as wind.

Others refused to go back the next morning.

When the sheriff reviewed their findings later that week, he told a reporter quietly.

It’s as if the woods swallowed them whole.

And for the families standing by that empty trail head, staring into the darkening ridge, that’s exactly how it felt, as though Red Hollow itself had erased four young lives overnight, leaving behind only silence and the faint hiss of static from a phone that shouldn’t have still been playing.

The official search would continue into the next week, but by then, even the most hopeful among them knew something terrible had happened.

Something far beyond getting lost.

By the second day of the search, Red Hollow had turned into something that looked more like a military operation than a missing person’s case.

Police cruisers lined the gravel road.

Volunteers poured in from three neighboring counties and a command tent had been set up at the trail head where the cousin’s SUV still sat under a gray tarp.

The vehicle was now part of an active investigation.

But for the families standing nearby, it had become something else, a symbol of everything they didn’t understand.

Sheriff Carl Donnelly coordinated the search teams.

He was an older man, born and raised in Monroe County, and he’d handled missing hikers before, but never for at once, and never without a single trace.

On the second morning, he called in state resources, helicopters equipped with thermal imaging, cadaavver dogs, and park rangers familiar with the terrain.

The search grid extended 3 mi in every direction, covering the ridge, the creek beds, and the wooded hollows.

They expected to find footprints, maybe an abandoned campsite, something simple, but the forest gave them nothing.

Volunteers described it as if the woods had been reset overnight.

Not a snapped branch, not a torn piece of fabric.

The trail that should have led from the SUV toward the ridge just faded into undergrowth.

Even the dogs were confused, each one losing the scent after roughly 200 yd, exactly where the first team had stopped.

By day four, the mood had changed.

What began with adrenaline and determination had turned into something quieter, more desperate.

The weather wasn’t helping.

Mist clung to the trees through most of the mornings, and by afternoon, the heat returned, heavy and suffocating.

Deputies rotated in shifts, their boots sinking into soft red mud that seemed to pull at every step.

Searchers began referring to that place as the Hollows Pull, a half joke that none of them found funny for long.

It was around this time that detectives began cataloging everything recovered from the SUV.

Inside the glove box, one an officer found a folded map.

A photocopy of an old logging survey from the early 1,980s.

Faded pen marks circled an area southeast of where the cousins had parked.

Someone had drawn a red X over a spot labeled Gully 3B when investigators compared it to topographic maps.

The marked area lined up with a ravine just beyond the main ridge, several miles off the public trails.

Sheriff Donnelly sent two deputies to check it out.

The trek took nearly 2 hours through thick brush and steep elevation.

When they reached the coordinates, all they found were the remains of old machinery, rusted out logging equipment, chains, and a collapsed structure that might have been a tool shed decades earlier.

The ground was uneven, pocked with shallow holes in animal burrows.

Near one of them, they found bones later confirmed to be from a deer, long since scavenged.

But what unsettled the searchers most was how quiet the place was.

No insects, no birds, just the low creek of the trees swaying overhead.

The deputies radioed back that there was nothing there, nothing human at least.

Still, the site was logged and flagged.

For days afterward, search teams kept returning to it, almost as if drawn by instinct.

Each time they came back empty-handed.

The families had set up camp near the command tent by then, refusing to leave until something was found.

Amy’s father spent hours pacing between the vehicles, watching the forest line like he expected to see the kids walking out at any moment.

Josh and Ryan’s mother sat in a folding chair with her hands clutched around her son’s old baseball cap, barely speaking.

By midweek, frustration began to build.

Rumors spread among volunteers that police had mishandled the early evidence that the SUV had been unlocked before forensic texts arrived, that the scene might have been contaminated.

The sheriff denied it, but the damage was done.

Family members began clashing with officers, demanding more manpower, more helicopters, more dogs.

A local pastor tried to mediate, but tempers flared.

At one point, Caleb’s uncle shouted that the department had lost precious time, and the argument nearly turned physical before deputies intervened.

It was grief, pure and raw, spilling out into the only space left to contain it.

When media outlets picked up the story, reporters swarmed the small town.

Satellite trucks parked outside the sheriff’s office and interviews aired on local television, replaying the same images.

The cousins smiling faces in yearbook photos.

The trail head roped off with police tape.

The sheriff standing before a wall of microphones repeating the same promise.

We are doing everything we can.

For a few days, the case became a regional obsession.

Talk radio hosts speculated wildly about what had happened.

Some said the kids had stumbled onto something illegal, a drug operation or poachers.

Others blamed wildlife, pointing to the area’s history of black bears.

One morning show even interviewed a self-described local historian who brought up the legend of the red hollow sinkhole sections of ground that had collapsed years earlier and were fenced off by the county after several livestock went missing.

That rumor took on a life of its own.

Searchers began referring to one particular depression near the ridge as the pit.

It had been sealed with chain link decades earlier, but several locals told deputies that the fencing had rusted away.

Theories spread that the cousins might have wandered too close and fallen in.

County engineers brought in ground penetrating radar to check the site, but the readings came back inconclusive.

The sinkhole was too deep, the soil too unstable.

On the seventh day, one of the cadaver dogs alerted near a dry creek bed about a mile from the campsite.

Hope surged again.

The area was cordoned off and excavated for 2 days.

What they found was a shallow depression filled with rainwater and animal tracks, nothing else.

It was the first of many false alarms.

As the days wore on, even the most determined volunteers began to fade.

People had to return to work, to their families.

The search perimeter expanded past 15 square miles, covering forest, pasture land, and parts of the old county road.

Each new area yielded nothing but more silence.

One night, as deputies reviewed maps by Lantern Light, Josh’s uncle recalled a conversation he’d had with his nephew just days before the trip.

Josh had mentioned camping near where Grandpa used to hunt, somewhere off the ridge, past the old fire road.

That clue sent a fresh wave of searches toward the western slopes, but again, no sign of the cousins emerged.

By the 10th day, the official search was scaled back.

Only a handful of officers remained on rotation.

Families protested outside the courthouse, pleading with the sheriff not to give up, but the truth was they’d run out of leads.

Every logical explanation had been tested, every trail examined.

Every piece of ground walked, and nothing added up.

The press began to lose interest.

The crews packed up, the headlines grew smaller, and the story slipped from the front page.

For the families, that silence was unbearable.

They continued searching on their own, forming small groups on weekends, walking the same trails over and over, convinced they must have missed something.

In the months that followed, Red Hollow returned to being what it had always been, an expanse of forest that swallowed sound and memory alike.

The signs from the search were slowly removed, but those who’d been there said it never felt the same again.

Hunters spoke of unease in that part of the ridge, of animals acting strangely quiet, of sudden drops in temperature near the gully marked on that old map.

For the sheriff, it became the case that haunted his career.

For the families, it was a wound that refused to close.

And by the time the first anniversary came and went, there was nothing left but questions and an unshakable feeling that something in those woods knew exactly what had happened and wasn’t ready to let it be found.

By 2025, Red Hollow had become a story you only heard in fragments, the kind told quietly at campfires or brought up on late night radio when the weather turned cold.

To locals, it was part of the county’s folklore.

Now, the case of the four cousins had faded from headlines long ago, but it never truly disappeared.

It lingered in the same way fog still clung to those hills each morning, hanging low and unwilling to lift.

For most people, life went on.

The road leading into the hollow was now cracked and half swallowed by overgrowth.

The old wooden sign that once marked the trail head leaned crooked, its paint flaked and letters barely visible.

Only a handful of people still visited hunters, hikers, and the occasional curiosity seeker who’d grown up hearing the story as a warning.

Parents still told their kids not to wander past the second ridge.

There were stories of phones losing signal, radios cutting out with static, and animals refusing to enter certain parts of the forest.

None of it was ever proven, but everyone seemed to agree on one thing.

The woods around Red Hollow felt wrong.

Sheriff Carl Donnelly had retired nearly a decade earlier, though the case never really left him.

Each July, on the weekend closest to the anniversary, he returned to the site.

He’d park his truck near the old trail head, stand beside the weathered memorial cross someone had hammered into the ground, and stay until sundown.

The new sheriff once asked him why he still went back.

Donnelly only said, “Because somebody has to.

” His hair had gone gray, his posture slower.

But even in his 70s, he still carried that same quiet guilt, the kind that never lets you forget what wasn’t found.

Two of the parents had passed away by then Amy’s mother in 2016 after a long illness.

And Josh and Ryan’s father, just two years later, from a heart attack.

Both went to their graves without answers.

Their surviving relatives still gathered occasionally at the family’s property, sitting around old photo albums, replaying the same questions.

Where had they gone? What did they miss? Around the 20-year mark, the story resurfaced.

A true crime podcast called Vanished in Plain Air released a three-part episode about the Red Hollow disappearance.

The hosts dissected every known detail.

the static filled phone, the wiped fingerprints, the note that said Southpath.

They interviewed retired deputies, local hunters, even the former sheriff himself.

Within weeks, the episodes went viral, sparking a wave of renewed interest.

YouTube creators began posting deep dive videos with titles like The Red Hollow 4: What Really Happened in Tennessee? Forums lit up with speculation.

Online sleuths started connecting dots that hadn’t been public knowledge at the time.

Some pointed out a pattern of missing person reports stretching back to the 1,980 seconds.

Hikers, hunters, even a utility worker, all within a 10-mi radius of the ridge.

A Reddit user claiming to be an amateur radio operator shared logs from 2003 showing interference patterns near Red Hollow during the weekend the cousins vanished.

According to his notes, the interference followed a strange pulse sequence similar to a distress transmission, but without an origin signal.

That post alone received thousands of comments, though authorities later said no such data was ever verified.

As with most cold cases revived by the internet, speculation spread faster than facts.

One theory claimed the cousins had stumbled onto a hidden mine entrance, possibly sealed off by the county years earlier.

Another suggested an encounter with illegal dumpers or even someone living off-rid in the area.

A few of the more sensational accounts blamed something stranger.

Military testing, magnetic anomalies, the red hollow hum.

Each new explanation only deepened the mystery, adding more noise to a story already drowning in silence.

Still, that surge of attention did something unexpected.

It reached the right ears.

In early 2024, a detective from the Monroe County Cold Case Unit named Laura Hensley quietly reopened the file.

She was young, too young to remember the original disappearance, but she’d grown up hearing the story.

In an interview later, she said she always thought it sounded unfinished.

The evidence boxes were still stored in the basement of the sheriff’s office, weathered folders, VHS tapes from news broadcasts, and the original case photos sealed in plastic.

Many items were degraded with time, moisture, mold, faded ink.

But Hensley believed new technology could do what the old one couldn’t.

She reached out to the remaining family members that spring, asking for updated DNA samples to compare against unidentified remains from across the state database.

It wasn’t a a promise, just a chance, a way to rule out or confirm possibilities.

The families agreed for them.

After 22 years, even the smallest action felt like progress.

Meanwhile, something else was stirring in Red Hollow.

The county had approved a new logging project that would reopen parts of the forest untouched since the early 2000s.

Environmental groups protested, citing erosion risks, but the contract moved forward anyway.

Bulldozers and survey crews began marking trees and cutting access roads near the lower ridge, not far from where the cousin’s camp had once been found.

Locals didn’t like it.

They said the hollow should be left alone.

Some of the older residents claimed they’d seen strange things there.

Lights flickering between the trees at night.

Sounds like metal grinding deep underground.

Hunters said their GPS units malfunctioned near the gully.

Compasses spinning for no reason.

The county dismissed it all as superstition.

But when the logging began, the old story started breathing again.

Workers reported equipment failures, radios losing power mid-transmission.

One foreman told a local paper his men refused to keep working past sunset.

It was easy to dismiss those stories as nerves, but the timing couldn’t have been more coincidental.

The same week the machines moved in, Detective Hensley received her first meaningful tip.

A man who claimed to have been a volunteer during the original 2003 search came forward.

He said he’d remembered something that had never made it into the reports.

A conversation between two deputies on the last night of the search.

They’d been standing near the ridge when their radios cut out, replaced by the same faint static everyone remembered from the phone left at the campsite.

One of the deputies, now long retired, had sworn he heard a voice beneath the noise, a single word repeated over and over.

The witness couldn’t recall what it was, but he said it didn’t sound right.

Detective Hensley logged the statement, but said nothing publicly.

privately.

She wondered if it tied back to the strange radio interference mentioned online.

The only way to know was to go back back to where it all began.

That summer, she drove to Red Hollow herself, standing at the overgrown trail head with the old case file in her hands.

The road was nearly impassible now, but the forest still looked the same, dense, silent, waiting.

In town, people noticed her visit.

Some said it was good to see someone finally caring again.

Others said the case should stay buried, that reopening it would just stir up old pain.

But by then it was already too late.

The combination of the podcast, the online speculation, and the logging project had reignited something in the public consciousness.

For the first time in years, Red Hollow wasn’t just a ghost story anymore.

It was an open question.

Families began visiting the ridge again.

Small memorials appeared near the trail.

a faded photo across a single candle.

On the 22nd anniversary, the surviving relatives gathered quietly near the treeine.

No press, no news crews, just silence broken only by the sound of wind moving through the leaves.

As they stood there, someone mentioned hearing a faint hum like a far-off engine buried deep underground.

Most brushed it off, but for Detective Hensley, watching from a distance.

It lingered, not because of what it was, but because of what it meant.

For two decades, Red Hollow had guarded its secret.

Now, with the land being torn open for the first time in years, it was about to give something back.

No one knew it yet.

But the truth that had slept under those woods for 22 years was closer than anyone imagined.

and what they would uncover next would finally answer the question that had haunted four families since that summer of 2003.

Every case we cover takes weeks of research and long nights digging through real records to bring forgotten stories back to light.

We do this because these lives matter and they deserve to be remembered.

If you want us to keep uncovering the truth behind these mysteries, please like, subscribe, and tell us in the comments which part of this case hit you the hardest.

For more mysterious cold cases, check out the links in the description below.

Now, let’s get back to the case.

It was early September, just after dawn, when Mark Ellison parked his truck at the edge of the old service road leading into Red Hollow.

He’d been hunting these woods for most of his life and knew their temperament.

the way fog settled like a low ceiling, and how every step off trail felt like walking into a different world.

It was bow season, the air cool and still, and he’d planned to set up along the ridge where the deer trails converged.

But as he moved deeper into the trees, something caught his eye an area where the ground didn’t look quite right.

He noticed at first because of the stones.

The forest floor was mostly leaf litter and roots.

But here, a shallow patch of earth was covered in small rocks.

arranged unnaturally flat, as if someone had tried to disguise something.

Mark hesitated.

He’d stumbled onto plenty of old logging debris before, rusted tools, animal carcasses, but this looked different.

The soil was compacted, the stones deliberately placed.

He crouched down, pushing aside a few of them with his glove.

Beneath the surface, something dull caught the light.

It wasn’t metal exactly, more like hardened rubber.

When he brushed away more dirt, he saw the edge of what looked like a boot sole cracked, half buried, still attached to a sliver of decayed fabric.

Just inches away lay something else, small and gray white.

At first, he thought it was a deer bone.

But then he saw the shape, the curvature, the texture, human.

Mark stood frozen.

His first instinct was disbelief.

The second was dread.

He pulled his phone from his jacket and stared at it for a moment before dialing.

The sheriff’s office.

When dispatch answered, his voice shook as he said, “I think I found something up on Red Hollow Ridge.

” Within an hour, deputies arrived.

The area was sealed off with tape, and Mark was asked to stay nearby while investigators assessed what he’d found.

He gave them his GPS coordinates and replayed his route, explaining he’d gone off trail to avoid spooking game.

The sheriff’s department logged his location and called in the state forensic unit.

By late afternoon, the ridge was crawling with investigators in protective suits, moving slowly and deliberately.

Photographs were taken from every angle.

Markers placed beside each object before the first layer of stones was removed.

Beneath the rocks lay a shallow depression roughly 5 ft long and 2 ft wide, too small to be a grave, but deep enough to suggest something had been buried intentionally.

As the dirt came away, they found more fragments.

Small bones scattered in irregular clusters, sections of weathered cloth clinging to them like ash.

A rusted metal flask lay beside the remains.

The initials J R faintly etched on its side.

One of the detectives noted it immediately.

Those initials matched one of the missing cousins, Joshua Rurn.

The atmosphere among the team shifted instantly.

For 22 years, the red hollow case had existed in a strange limbo, half myth, half memory.

But now, under the quiet canopy of trees, there was no mistaking what they’d found.

The excavation stretched into the next day.

Forensics teams brought in portable lighting and tents to shield the site from weather.

The process was slow.

Every inch of soil sifted and cataloged.

Beneath the first cluster of remains, they discovered more fragments of a second skull.

partial ribs and what appeared to be a piece of melted plastic.

It wasn’t until the coroner examined the fragments that the first real detail emerged.

The bones showed clear signs of blunt force trauma, too.

Fractures consistent with a hard impact, possibly from a fall or a strike.

There were no animal chew marks, no drag evidence, no signs of postmortem disturbance from wildlife.

Whatever had happened here, it had been violent and human.

Within 72 hours, dental records confirmed the worst.

The remains belonged to Josh Raburn and his cousin Caleb Thomas, two of the four who vanished back in 2003.

The announcement hit the local community like a shock wave.

For the families, it was both relief and heartbreak.

After two decades of uncertainty, at least part of the mystery had finally surfaced.

Detective Laura Hensley, the same investigator who had reopened the case the year before, arrived on site personally.

She walked the perimeter slowly, taking in the geography.

The location was nearly 2 mi from where the original search teams had focused.

The area had been outside the grid, obscured by dense undergrowth and steep, uneven slopes, easy to miss, even with aerial scans.

It raised an immediate question.

Had the cousins ever made camp here, or had someone brought them afterward? Forensics soon added more clues.

In the surrounding soil layers, technicians found remnants of fabric fibers matching nylon camping gear, a corroded lighter, and pieces of melted plastic, later identified as parts of a portable stove, specifically a 2003 Coleman model, the same type sold in outdoor stores that summer.

The discovery meant one of two things.

Either the cousins had set up camp here willingly or their gear had been relocated long after they vanished.

Each item was bagged and logged meticulously.

The flask went to the evidence lab first.

Despite two decades of exposure, trace material was still present inside residual alcohol mixed with what looked like soil sediment.

The flask had been dented on one side.

The metal folded inward as if struck by something hard.

Detective Hensley noted another detail that unsettled her.

The depression wasn’t a typical grave.

It lacked the depth and uniformity of a burial done with care or time.

The layering of stones suggested a hurried attempt to conceal rather than preserve.

It was as if someone had needed to hide the evidence quickly and leave.

Mark Ellison’s GPS data turned out to be invaluable.

By cross- refferencing his route with old forestry maps, analysts noticed a pattern.

But the site he stumbled on aligned almost perfectly with the coordinates of that old Gully 3B location marked on the 2003 map found in the cousin’s SUV.

When ground penetrating radar was brought in, it revealed anomalies extending several yards beyond the initial discovery zone, shallow voids in the soil, irregular density shifts consistent with buried metal or bone.

Excavation expanded.

Technicians uncovered a half- buried camping stove frame, rusted but intact, along with what appeared to be a section of weathered tarp fused to the earth.

Beneath it, small bones, possibly animal at first glance, were later identified as human felanges.

Another layer down revealed two more personal items.

A metal keychain shaped like a compass and the broken face plate of a wristwatch frozen at 10:47.

The forensic team worked for a week before the ridge was finally cleared.

Each night, as the light faded, the sound of digging was replaced by the drone of generators and the distant hum of the forest.

Even seasoned investigators admitted the atmosphere was oppressive.

Some described a sense of being watched.

Though whether it was nerves or something deeper, no one could say.

When the county coroner’s office released its preliminary findings, the details were stark.

Both victims had suffered blunt force trauma prior to death with fractures suggesting a single directional strike.

The injuries weren’t consistent with a fall or collapse.

The evidence of melted plastic indicated that a fire, possibly accidental, possibly deliberate, had occurred near or over the burial site.

The charred debris in the surrounding soil, showed chemical traces from burned nylon, consistent with tent fabric.

The discovery turned red hollow from a cold case into an active investigation.

Overnight, law enforcement returned to the ridge with new urgency, mapping the area where radar had shown additional anomalies.

Drone footage captured subtle shifts in the ground.

Shallow depressions scattered like scars across the slope.

Analysts flagged two specific zones for deeper analysis, both within 20 yards of where the first remains were found.

Meanwhile, Detective Hensley revisited the original witness statements from 2003.

One detail stood out now, the mention of metallic noises heard by locals the night the cousins disappeared.

She wondered if those sounds could have come from the same rusted machinery found near the gully, or perhaps from the collapse of a structure hidden beneath the soil.

When she spoke with Mark Ellison again, he mentioned something she hadn’t seen in his report.

The day he found the site, before calling police, he’d noticed the faint smell of something chemical, like old fuel or burned plastic.

He’d assumed it came from decomposing materials.

But after learning about the stove fragments, it made sense.

The implications were unsettling.

The cousins hadn’t been miles away, lost in the forest, they’d been right there, buried beneath the same ground search teams had walked over 22 years earlier, hidden by nothing more than a thin layer of soil and time.

As word spread, locals began returning to Red Hollow again, some to leave flowers, others to satisfy their own curiosity.

News vans parked along the county road.

For the families, it reopened old wounds.

But for the sheriff’s office, it reignited hope.

For the first time in decades, the mystery was no longer abstract.

It had a place, a scent, a tangible shape.

And as forensic crews packed up the last of their equipment that night, the radar readings still haunted them.

Because the machine had shown something else deeper, larger voids beneath the ridge that didn’t align with natural formations.

Detective Hensley stood at the edge of the cleared sight, watching as the last lights dimmed against the trees.

The air was heavy, the forest silent except for the rustle of wind through branches.

Somewhere beneath her feet, more answers waited.

maybe even the rest of them.

And as the darkness closed in around Red Hollow, one truth became impossible to ignore.

Whatever had happened to those four cousins hadn’t ended here.

It had started here.

And something about this ground still wasn’t finished, giving up its secrets.

Excavation at Red Hollow resumed quietly in the weeks that followed.

The site had been expanded another 30 yards down slope, where the ground penetrating radar had detected additional voids.

What began as a careful forensic dig had now turned into something closer to an archaeological operation.

Every scoop of soil was sifted, every discovery photographed.

The deeper they went, the stranger the findings became.

By the end of the second week, investigators uncovered the top of what looked like a metal frame.

At first, they assumed it was more logging equipment from the 1,980 seconds and other rusted relic swallowed by time.

But as the shape took form, it became clear it wasn’t just machinery.

It was a vehicle buried nose first into the hillside.

Its rear axle jutting out of the dirt.

The metal was corroded.

The paint long gone, but faint lettering was still visible on one of the doors.

Monroe County Maintenance County records showed that one of those trucks at 1,978 Chevrolet utility model had been reported missing in 1,989 after a storm damaged part of the ridge.

The assumption at the time was that it had slid into a ravine and been washed away.

No one had ever found it.

Investigators brought in a crane to stabilize the slope and began carefully removing the soil around the cab.

The windows were shattered and the interior smelled of rust and burned plastic.

Inside, wedged between collapsed seats and a layer of compacted mud.

They found three objects that stopped everyone cold.

Three cell phones melted together into a single black mass and beside them, the remains of a smashed handheld radio.

The discovery didn’t make sense.

Cell phones from 2003 shouldn’t have been inside a truck that vanished more than a decade earlier.

But when technicians cleaned and scanned the fused pieces, faint serial numbers emerged beneath the residue.

Those numbers matched three of the phones registered to the missing cousins.

Amy’s flip phone, Ryan’s Nokia, and Caleb’s prepaid model.

All three had been listed as untraceable since the weekend they vanished.

The handheld radio, though nearly destroyed, still bore a partial tag property of Monroe County.

That meant it had belonged to the same maintenance department that once operated the truck.

But why it was there, and how those phones had ended up inside became all the central question.

The coroner’s team, meanwhile, continued analyzing the remains recovered earlier.

Both Josh and Caleb had shown signs of blunt force trauma to the skull, consistent with impact from falling debris or heavy metal.

More alarming, bone marrow samples from both victims contained carbon monoxide residue levels high enough to indicate they’d been breathing the gas before death.

That finding shifted the entire investigation.

It suggested that the cousins hadn’t died immediately from violence or exposure, but from suffocation, likely trapped in an enclosed space with limited ventilation.

Detective Laura Hensley began piecing together the timeline.

It was early August 2003 when they vanished a weekend marked by fastmoving storms and lightning strikes across the county.

If the cousins had taken shelter from the rain, maybe they’d found this old truck half buried near the slope.

The vehicle could have provided temporary refuge, its interior shielded from the weather.

But if the exhaust system had been damaged or blocked by soil, running the engine could have filled the cab with carbon monoxide in minutes.

On paper, that seemed plausible an accident.

A tragic chain of events.

But the deeper they dug, the less it felt like one.

When forensics examined the soil surrounding the truck, they found it had been disturbed years after the original burial.

Layer compression tests indicated multiple shifts.

The first from natural erosion and the second from manual disturbance, likely within two to three years of the cousin’s disappearance.

That detail alone contradicted the idea that their remains had simply been sealed away since 2003.

Someone had come back.

The team also recovered a piece of fabric wedged under the driver’s seat, a torn section of what appeared to be a uniform sleeve.

The tag, still legible beneath grime, bore the Monroe County seal.

DNA analysis later confirmed it belonged to a male adult, but not one of the victims.

When records were checked against county employees from the early 2000s, no match was found.

The department had no record of anyone assigned to that sector at the time.

As the days passed, the investigation took on a different tone.

What had started as relief, the long- awaited discovery of answers turned into something claustrophobic and unnerving.

The site itself seemed to close in around them.

Every piece of evidence pointed to an overlapping timeline, a storm, an abandoned maintenance vehicle, an apparent accident, yet the evidence of interference was undeniable.

Investigators found fragments of plastic insulation scattered around the buried chassis, partially melted, but distinct.

Chemical analysis showed traces of ethanol and lubricant residue, suggesting a fire had burned there at some point, though not strong enough to reach the surface.

The scorched soil matched the chemical composition of camping fuel, the same type used in the Coleman stove found earlier.

Forensics reconstructed a possible sequence.

The cousins might have taken shelter near the slope during the storm.

They lit their stove for heat, not realizing how close they were to a buried truck or enclosed air pocket.

The fire depleted oxygen rapidly, releasing carbon monoxide that pulled inside the depression.

The gas would have overcome them in minutes.

But that still didn’t explain the blunt force injuries or the relocated remains.

Detective Hensley suspected a second collapse.

The old truck, already unstable in the hillside, might have shifted after heavy rainfall days later, crushing part of the camp.

In the chaos, the equipment, phones, radio, lighter could have tumbled into the vehicle’s cabin.

Natural erosion and soil movement could have buried everything where it now rested.

It was an elegant theory, but it didn’t hold up under scrutiny because one of the skulls recovered from the site had sediment embedded not just outside, but within the cranial cavity, meaning it had been exposed, then re-eried later.

That kind of post-mortem relocation didn’t happen naturally.

Someone had dug into the site and disturbed the remains years after the deaths.

County records showed that in 2005, a contractor had been hired for limited erosion control in the same area, though no maintenance vehicles were logged at the location.

The name on the work order was illegible.

The document water damaged and incomplete.

Investigators began to wonder whether someone connected to that project had stumbled across the remains back then and instead of reporting it decided to hide what they found.

When the evidence was sent to the state lab, analysts noted another strange detail.

The three phones retrieved from the truck all showed heat damage, but one the Nokia registered to Ryan contained intact memory sectors.

Using data recovery software, they managed to extract partial files, corrupted timestamps, incomplete logs, and one brief audio fragment.

The recording lasted only 6 seconds.

It was mostly static, but just before it ended, a faint sound, heavy breathing followed by what might have been a word emerged beneath the noise.

Some thought it was help, others, stop.

The signal was too degraded to be certain.

When the results were shared with the families, it reopened everything.

The grief that had settled into quiet endurance was torn apart again.

For years, they’d imagined their children lost in the woods, possibly unaware of what was coming.

Now, evidence suggested they’d lived long enough to be trapped, suffocating, maybe calling out in vain.

Detective Hensley visited the ridge herself again that evening, long after the crews had gone.

The excavation site had been covered for safety, but the ground still bore the dark impression of where the truck had been pulled from the earth.

The air was thick with humidity and the smell of damp clay.

She crouched near the edge, running her hand over the soil, thinking about the layout, the tent, the stove, the slope, the vehicle.

Everything about it felt wrong.

If the cousins had truly sought shelter, they would have been near the main trail, not 2 mi down slope in a restricted maintenance zone.

And if they’d stumbled onto that old truck, how had they known it was there under the dirt? It wasn’t visible from any approach, not even from the ridge above.

The next morning, she ordered a complete re-examination of the GPS data collected from Mark Ellison’s hunting device.

When analysts mapped his coordinates alongside the excavation grid, a strange overlap appeared.

The hunter’s route aligned almost perfectly with the faint outline of an old access road that didn’t exist on modern maps.

That road had led directly to the maintenance zone last serviced in 1989, the same year the truck disappeared.

The implication was chilling.

The cousins might have followed the remnants of that road unknowingly, led there by a curiosity or confusion during the storm, or someone who knew the terrain had led them there.

Whatever the truth was, one fact remained.

The four cousins hadn’t just vanished into the woods.

They’d walked straight into a place already buried by time, and for reasons no one could yet explain.

Someone years later had gone back to make sure their story stayed that way.

And as the forensic teams prepared to dig deeper beneath the newly exposed slope, one of the radar operators noticed something that froze him midscan.

A denser shadow forming below the excavation zone, larger than the truck, almost rectangular.

It wasn’t natural, and it wasn’t metal.

The next phase of the investigation would focus there, deeper into the ridge, into the layers of soil that hadn’t been touched in decades.

Whatever was buried beneath that ground, it wasn’t just an accident waiting to be uncovered.

It was the final piece of what Red Hollow had been hiding all along.

It took months before the full picture began to take shape.

By early spring of 2026, the state forensic lab had finished cross-referencing every piece of data recovered from Red Hollow.

DNA sequencing confirmed what investigators had already suspected.

The remaining traces found near the buried truck belong to Amy and Ryan, the two cousins whose remains had never been located until now.

For the first time in 23 years, all four names could finally be placed to rest.

But even with that confirmation, the question that haunted everyone wasn’t just who it was.

How how had four young people familiar with the outdoors, equipped with supplies, vanished less than 5 mi from a main road and gone undiscovered for two decades? The answer, when it came, was equal parts tragic and unsettling.

The forensic reconstruction painted a story that began with curiosity and ended in confusion.

Investigators determined that the slope where the cousins had camped sat directly above an old empty underground structure, not a mine exactly, but part of a long decommissioned storm drainage system built back in the 1,970 seconds for the county’s road department.

The truck uncovered during excavation had been one of several vehicles used during the project.

Over the years, heavy rain and erosion had caused the ground to collapse in sections, leaving hollow voids beneath the ridge.

According to soil analysis and 3D mapping, a small entrance to that underground chamber would have been visible in 2003, a narrow opening between exposed rock and tree roots, just large enough for a person to squeeze through.

It had since been sealed by sediment and time, but in the photos recovered from one of the cousins old disposable cameras, investigators noticed something chilling.

One of the last frames, grainy and blurred, showed what appeared to be a dark tunnel framed by beams of rusted metal, a structure no one had known existed before the excavation.

Forensic engineers theorized that the group had discovered this opening while exploring the ridge and decided to check it out.

Evidence suggested they’d brought their stove inside for light and warmth.

Traces of camping fuel were found throughout the chamber along with scorched rock consistent with a small controlled flame.

But something had gone wrong almost immediately.

The coroner’s report confirmed that all four cousins had significant carbon monoxide levels in their bone marrow, indicating exposure to toxic gas before death.

Further analysis of the surrounding rock revealed a corroded metal pipe, part of the original storm drains ventilation system that had collapsed under decades of pressure.

That pipe had once connected to the buried maintenance trucks exhaust system.

When investigators reconstructed the alignment, they realized that if the truck’s engine had been restarted during a later maintenance attempt, even briefly, it could have vented exhaust directly into the underground chamber.

The timeline was horrific but plausible.

The cousins trapped inside a narrow enclosure may have been overcome in minutes.

The stove, the fuel residue, the heat damage to their phones, all of it matched the conditions of a confined space gas leak.

The partial collapse of the tunnel afterward likely buried them where they fell, sealing the site from view.

For most of the investigative team, that conclusion was enough.

It provided closure, a technical explanation that accounted for every trace of evidence.

But there was one detail that refused to fit a detail that made even seasoned investigators uneasy.

During the final phase of excavation, just beyond the collapse zone, forensic surveyors uncovered a trail of bootprints impressed into the clay.

They were faint but distinct, preserved by the oxygen poor soil.

The tracks led away from the collapse, following a shallow incline before vanishing at the edge of the slope.

Analysis confirmed they did not match any of the victim’s footwear.

The tread pattern was older, possibly from a work boot manufactured in the 1,990s.

Whoever had left those prints had been there after the tunnel collapsed.

That single anomaly changed the story again.

If those prints belonged to a rescuer, no one had ever come forward.

If they belonged to someone who’d found the site accidentally, perhaps during the 2005 erosion repairs, it meant that person had chosen not to report what they saw.

Forensic soil dating gave that theory weight.

The topmost layer of disturbed earth surrounding the burial measured roughly 20 years old, matching a rearial period around 2005, 2 years after the cousin’s disappearance.

Someone had uncovered part of the site and deliberately filled it back in.

Detective Hensley combed through county employment records from that year, looking for anyone who had worked near the ridge.

The maintenance logs were incomplete, but one name surfaced repeatedly.

A seasonal contractor named Roy Dalton.

He’d been a drifter hired for a few months during flood repairs before vanishing later that summer.

His last known address was a trailer park 30 mi south of Red Hollow.

He’d left behind unpaid rent, a truck sold for cash, and no forwarding information.

Locals remembered him vaguely quiet, odd, the kind of man who kept to himself.

One shop owner recalled seeing him come into town once with deep scratches along his arms and dirt caked under his nails, saying something about a bad cave.

A police report filed years later described Dalton as a missing person, though no remains were ever found.

Whether he’d stumbled upon the site by accident or had some prior connection to it, no one could prove.

But for the sheriff’s office, his disappearance and the rearial dating was enough to close the loop.

Someone had found the cousins, realized what they’d uncovered, and instead of reporting it, buried the evidence again.

Maybe out of guilt, maybe out of fear, maybe both.

When the news broke publicly, it drew both relief and disbelief.

For some, it was the closure they’d waited two decades for.

For others, it was another layer of unanswered questions.

The families gathered on the ridge that spring to dedicate a memorial.

Four wooden crosses standing in a line overlooking the forest.

Each bore a name carved by hand.

The letters simple but deliberate.

There were no speeches, just silence, the kind that fills a place when grief finally stops, being an open wound and becomes something quieter, heavier, permanent.

Detective Hensley stood with them, watching as the wind moved through the trees, stirring the dry leaves that had already begun to settle over the ground.

Nearby, the old excavation site had been filled and sealed.

A faint patch of disturbed earth, now overgrown with grass.

For all intents and purposes, Red Hollow was finished.

But even she couldn’t shake what remained.

Those bootprints leading away from the collapse, preserved like a final unanswered question.

Forensics could tell her how deep they went, what size they were, even the brand of boot, but not why they were there, or what that person had seen before deciding to walk away.

In her final report, she quoted something Sheriff Donnelly had said years earlier during one of the anniversary vigils.

He’d been standing by the same ridge, the same fog rolling in behind him when a reporter asked if he believed the case would ever be solved.

He’d paused for a long time before answering.

We’ll find the truth, he’d said, but not the whole of it.

Now, more than two decades later, those words had never felt truer.

The red hollow case was closed.

The science made sense.

The records were complete.

Yet for everyone who’d stood at that ridge and looked into the trees, there would always be that feeling that something else was buried deeper still, waiting under the quiet ground, unseen, but not entirely gone.

News

Ilhan Omar ‘PLANS TO FLEE’…. as FBI Questions $30 MILLION NET WORTH

So, while Bavino is cracking down in Minnesota, House Republicans turning the heat up on Ilhan Omar. They want to…

FBI & ICE Raid Walz & Mayor’s Properties In Minnesota LINKED To Somali Fentanyl Network

IC and the FBI move on Minnesota, touching the offices of Governor Tim Walls and the state’s biggest mayors as…

FBI RAIDS Massive LA Taxi Empire – You Won’t Believe What They Found Inside!

On a Tuesday morning, the dispatch radios in hundreds of Los Angeles taxi cabs suddenly stopped playing route assignments. Instead,…

Brandon Frugal Finally Revealed What Forced Production to Halt in Season 7 of Skinwalker Ranch….

The Secret of Skinwalker Ranch became History Channel’s biggest hit. Six successful seasons documenting the unknown with real science and…

1 MINUTE AGO: What FBI Found In Hulk Hogan’s Mansion Will Leave You Shocked….

The FBI didn’t plan to walk into a media firestorm, but the moment agents stepped into Hulk Hogan’s Clearwater mansion,…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage… It started like any other evening…

End of content

No more pages to load