The 1906 wedding photo looked perfect—until the groom’s hand exposed a secret that stunned everyone

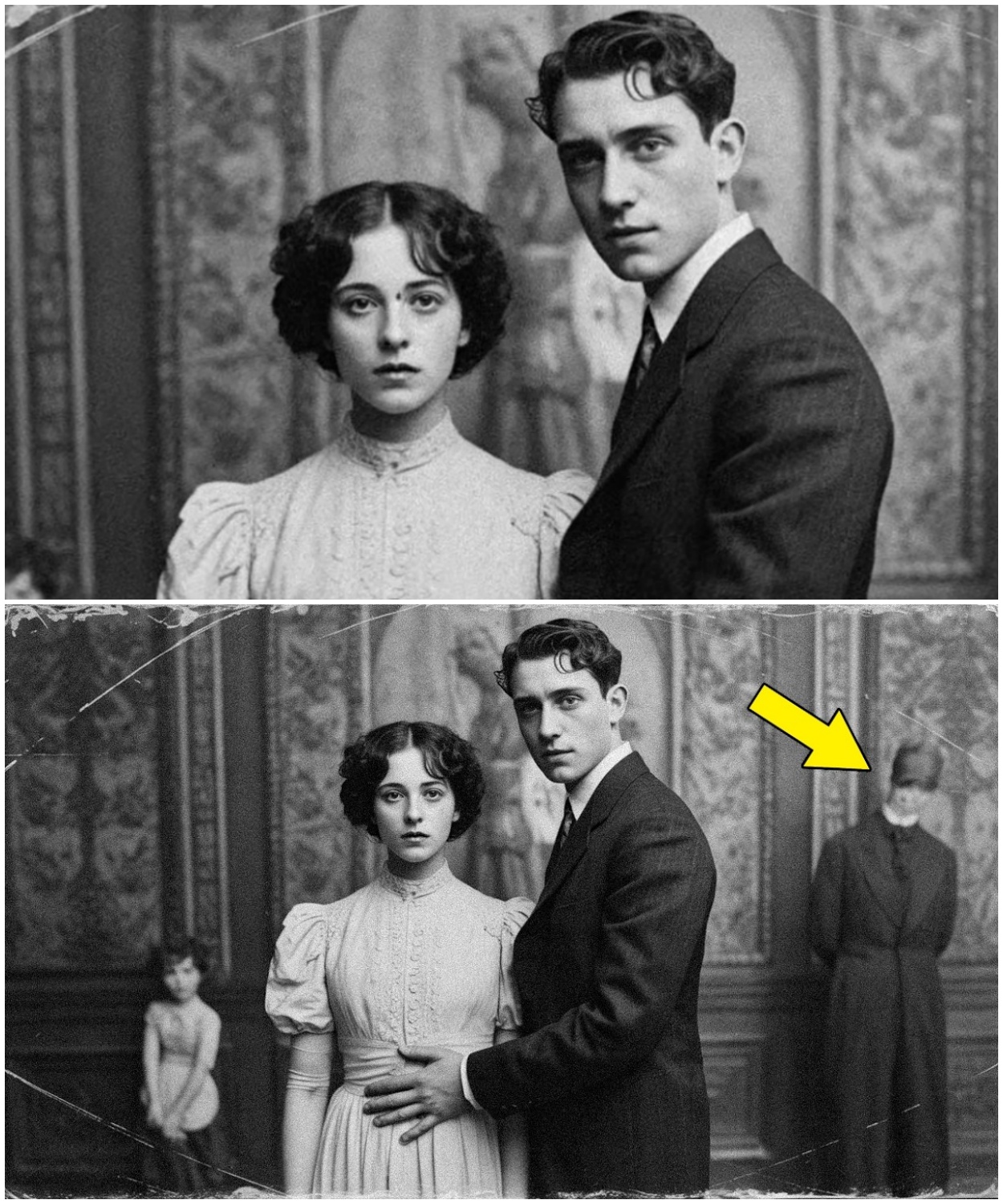

A wedding picture from 1906 that seemed absolutely perfect until someone looked a little closer at the groom’s hand.

What they discovered changed everything we thought we knew about this couple’s story.

The photograph arrived at the restoration archives in Portland, Oregon on a gray October morning in 2019.

Sarah Chen, a specialist in photographic restoration with over 15 years of experience, carefully unwrapped the brown paper package.

Inside, protected by acid-free tissue, lay a sepia toned wedding photograph from 1906.

The image showed a young couple standing before an ornate backdrop typical of early 20th century photography studios.

The bride wore an elaborate white dress with high lace collar and leg of mutton sleeves, her dark hair styled in the Gibson girl fashion of the era.

The groom stood beside her in a dark suit, his hand resting on her waist in what appeared to be a gesture of affection and possession.

Sarah placed the photograph under her magnifying lamp, examining it for damage.

The corners showed some wear and there were a few water stains along the edges, but overall the image had survived remarkably well for being over a century old.

The studio mark on the back read Whitmore Photography, Salem, Massachusetts.

Um, the photograph had been sent by Margaret Witmore, the great granddaughter of the photographer who had taken the original picture.

In her accompanying letter, Margaret explained that she had discovered a box of unclaimed photographs in her great-grandfather’s studio archive.

This particular wedding photo had intrigued her because of a handwritten note on the back that simply read, “Never collected.

Payment received in advance.

Do not pursue.

” Sarah found this detail curious.

In the early 1900s, wedding photographs were precious commodities.

For most couples, they represented a significant investment.

It was unusual for such an important photograph to go unclaimed, especially when the client had already paid.

As Sarah began the digital scanning process, she noticed something that made her pause.

The groom’s hand, resting on the bride’s waist, appeared slightly awkward in its positioning.

His fingers were curved in an unnatural way, as if gripping something beneath the fabric of the bride’s dress.

She increased the resolution and zoomed in on the area.

The fabric around his hand showed subtle distortions, small wrinkles and shadows that didn’t quite match the natural fall of the dress material.

Sarah had restored thousands of photographs, and her trained eye recognized when something wasn’t quite right in an image.

She made a note to examine this area more closely during the restoration process and continued with the initial scan.

The faces of the couple were clear and well preserved.

The bride had a serene expression, though her eyes held a certain intensity that Sarah couldn’t quite define.

The groom smiled broadly, his mustache perfectly groomed, his posture confident.

Later that afternoon, Sarah began the meticulous work of digital restoration.

She removed the water stains, corrected the fading, and enhanced the contrast.

As she worked on the area around the groom’s hand, she applied various filters to understand the underlying structure of the image.

What she saw made her breath catch.

Beneath the layers of aging and degradation, there was definitely something in the groom’s hand, something small and metallic that created a distinct shadow pattern.

The shape was partially obscured by the fabric, but it was clearly there, pressed against the bride’s side.

Sarah saved her work and decided to research the couple.

The studio mark gave her a starting point.

She contacted the Salem Historical Society, explaining that she was restoring a photograph from the Witmore Studio and asking if they had any records of weddings from 1906.

The response came 2 days later.

The historical society had found a newspaper clipping from the Salem Evening News dated October 1906 that mentioned a wedding at St.

Peter’s Episcopal Church.

The article was brief, noting that Thomas Ashford, aged 28, a cler at the local bank, had married Miss Katherine Rothell, aged 22, daughter of a prominent local merchant.

But there was another clipping dated 3 weeks later.

Sarah read it with growing unease.

Local bride missing.

Katherine Ashford, recently married, has not been seen since November 2nd.

Her husband, Thomas Ashford, reports that she left their home on High Street, claiming she needed to visit her mother, but never arrived.

The family is deeply concerned and asks anyone with information to contact the police.

Sarah searched for follow-up articles, but found nothing conclusive.

The trail went cold.

Catherine Ashford had simply vanished.

If you’re enjoying this story so far, leave a like and subscribe to the channel.

It really helps me continue bringing you these fascinating mysteries.

Sarah returned to the photograph with new perspective.

She stared at the groom’s hand, at that strange grip beneath the fabric.

She enhanced the image further, adjusting the contrast and brightness to reveal every possible detail.

The metallic object became clearer.

It was small, cylindrical, with what appeared to be a decorative handle.

Sarah’s pulse quickened as recognition dawned.

The shape and size were consistent with a late Victorian or Eduwardian era item that would have been common in 1906.

It looked like a straight razor.

The groom was holding a straight razor against his bride’s side during their wedding photograph, concealed beneath her dress.

Sarah sat back in her chair, her mind racing.

Why would someone do this? Was it a threat? A symbol of control? Had Catherine known it was there.

She looked at the bride’s face again at that intense expression she had noted earlier.

Now it took on a different quality.

Was that fear in her eyes? Or was Sarah reading too much into a century old photograph influenced by the knowledge of Catherine’s disappearance? The restoration was technically complete, but Sarah couldn’t bring herself to simply return the photograph to Margaret Whitmore without investigating further.

This wasn’t just a family heirloom anymore.

It might be evidence of something far darker.

Sarah spent the next week immersed in research.

She contacted libraries, historical societies, and genealogy databases, trying [music] to piece together the story of Thomas and Catherine Ashford.

The more she learned, the more disturbing the picture became.

Thomas Ashford had been employed at the Salem Merchants Bank as a junior cler.

By all contemporary accounts, he was considered a respectable young man from a modest background.

His marriage to Katherine Rothwell had been seen as an advantageous match.

Her father owned a successful textile import business, and the dowy would have significantly improved Thomas’s financial situation.

Catherine had been the youngest of three daughters.

Her older sisters had married well, and she was described in society columns as accomplished in piano and needle work, with a pleasant disposition and agreeable manner.

Their courtship had been brief, only 4 months from introduction to wedding.

This wasn’t unusual for the era, but Sarah noted that several diary entries from Catherine’s sister, Eleanor, mentioned concern about the haste of the arrangement.

One entry dated August 1906 read, “Father is quite insistent about Catherine’s engagement to Mr.

Ashford.

I wish Catherine seemed more enthusiastic about the match, but she says little on the subject.

” The wedding had taken place on October 15th, 1906.

The photograph had been taken at the Whitmore studio 2 days earlier on October 13th.

Catherine disappeared on November 2nd, only 18 days after the wedding.

Sarah found the police reports archived in the Salem City records.

The initial missing person report had been filed by Thomas himself.

He claimed that Catherine had left their home around 10:00 in the morning, saying she wanted to visit her mother.

When she didn’t return by evening, Thomas had gone to the Rothell House only to discover that Catherine had never arrived.

The police had conducted a search.

They interviewed neighbors, searched the route between the Ashford residence and the Rothell home, and questioned Thomas extensively, but no evidence of foul play was found, and no body was ever discovered.

The case remained open for 2 years before being officially classified as a cold case.

Thomas Ashford had moved to Boston in 1908, where he remarried in 1910.

He died in 1945, never having spoken publicly about his first wife’s disappearance.

Sarah contacted Margaret Whitmore again, asking if she could share the restored photograph along with the historical information she had uncovered.

Margaret was shocked by the revelation about the razor.

My great-grandfather never mentioned this photograph specifically, Margaret wrote back.

But my grandmother once told me a story about how he refused to develop certain photographs because he said he could see darkness in them.

She thought he was being superstitious.

But now I wonder if this was one of those photographs.

The note on the back, never collected, payment received in advance, do not pursue, took on new meaning.

Had the photographer recognized something wrong in the image? Had he tried to warn someone? Sarah decided to consult with a forensic psychologist who specialized in historical cases.

Dr.

Raymond Foster agreed to examine the photograph and the historical context.

Dr.

Foster spent an hour studying the image before offering his analysis.

The positioning of the razor suggests control and threat, he explained.

In Victorian and Eduwardian culture, wedding photographs were highly staged and symbolic.

Every element was carefully considered.

For a groom to be holding a concealed weapon during this most symbolic moment, it speaks to a psychology of dominance and implicit threat.

He pointed to the bride’s posture.

Notice how she’s slightly leaning away from him even though his hand is on her waist.

Her shoulders are tense.

These are subtle indicators of discomfort, possibly fear.

“Uh, but could it have been something else?” Sarah asked.

“Could there be an innocent explanation?” Dr.

Foster shook his head.

Given her subsequent disappearance and the fact that the photographer refused to release the photograph, I think we’re looking at evidence of an abusive and controlling relationship that likely escalated to violence.

The razor in the wedding photo was a warning.

Whether Catherine recognized it as such at the time, we can’t know.

Leave a comment below about what you think happened to Catherine.

I love hearing your theories.

Sarah felt a growing obligation to pursue this further.

She contacted a detective in the Salem Police Department’s cold case unit, explaining what she had discovered.

Detective Lisa Morrison was immediately interested.

We’ve had this case in our files for over a century, Detective Morrison said when they met at the police station.

Every few decades, someone takes another look at it, but there’s never been any physical evidence to work with.

This photograph might be the closest thing we have to understanding what happened.

The detective arranged for a forensic analysis of the restored photograph.

Experts examined the image using modern enhancement technology, confirming Sarah’s findings.

The object was indeed consistent with a straight razor from the period.

Detective Morrison began reviewing the original case files with fresh eyes.

She discovered something that previous investigators had noted but not fully explored.

Thomas Ashford’s financial situation had improved dramatically after Catherine’s disappearance.

Her diary had been paid at the time of marriage, Detective Morrison explained to Sarah.

But there was also a substantial trust fund that would have come to Catherine on her first wedding anniversary.

When she disappeared, Thomas, as her legal husband, eventually gained control of those funds after having her declared legally dead.

The financial motive was clear, but proving that Thomas had murdered his wife over a century after the fact was impossible.

There was no body, no crime scene, and no living witnesses.

Yet, the photograph remained, a silent testimony to something dark and threatening, captured in a moment meant to celebrate love and commitment.

As word of Sarah’s discovery spread through restoration and historical circles, other archavists began examining their own collections with new scrutiny.

Within a month, Sarah received emails from three different sources, each claiming to have found similar anomalies in wedding photographs from the same era.

A museum in Providence, Rhode Island, had a wedding photograph from 1904 showing a groom’s hand positioned unnaturally against his bride’s back.

Enhanced analysis revealed what appeared to be a small knife.

The bride in that photograph had died under suspicious circumstances 6 months after the wedding, officially ruled an accident.

A private collector in Boston discovered that a photograph from 1907 showed a similar detail.

A groom holding something metallic beneath his bride’s dress.

That bride had disappeared in 1908, also never found.

A historical society in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, found wedding photographs from 1905 and 1909, both showing grooms with suspicious hand positions.

Both brides had met tragic ends.

One supposedly committed suicide.

The other died in what was reported as a household accident.

The pattern was undeniable and chilling.

Sarah organized a meeting with Detective Morrison and several other law enforcement officials who specialized in historical crimes.

They gathered at the Salem Historical Society to examine all the photographs together.

We’re looking at what might have been a series of calculated murders, Detective Morrison said, studying the images laid out on the table.

These men were using the wedding photograph itself as a form of psychological control, a reminder to their brides that they held power over them, literally and symbolically.

I, one of the other detectives, Frank Torres, from the Boston Police Department, pointed out another disturbing detail.

Look at the photographers.

Three of these five photographs came from studios in Salem.

Two came from studios in Boston.

But when I cross-referenced the photographers, I found that they were all trained by or associated with the same master photographer, Edmund Crane, who operated a studio in Boston from 1895 to 1910.

This revelation opened a new line of inquiry.

Had the photographer been aware of what was happening? Had he been complicit in some way, or had he tried to stop it? Research into Edmund Crane revealed a complex figure.

He was considered one of the finest portrait photographers in New England during his career.

[music] He had trained over two dozen apprentices, many of whom went on to open their own studios throughout the region.

If you’re finding this investigation as compelling as I am, hit that like button and subscribe so you don’t miss the conclusion of this mystery.

But there were also darker rumors.

A newspaper article from 1909 mentioned that Crane had been questioned by police regarding his knowledge of a bride who had died shortly after her wedding portrait was taken in his studio.

No charges were filed and the matter was dropped.

Sarah found Crane’s personal journal in an archive at the Massachusetts Historical Society.

The entries were sparse and professional, mostly noting appointments and technical details about photographic processes, but there were occasional personal observations.

One entry from September 1906 caught Sarah’s attention.

Photographed the Asheford wedding party today.

Something troubling about the groom’s demeanor.

He insisted on a particular positioning of his hand.

Against my better judgment, I complied.

The bride was silent throughout.

I have a dark feeling about this union.

Two weeks later, another entry.

The Ashford couple came to collect their proofs.

The bride appeared diminished somehow, smaller than I remembered.

The groom collected the proofs himself, paying in cash.

He specified that no copies should be made.

I agreed though I retained the negative against protocol.

I cannot say why.

Then in early November I read in the newspaper that Mrs.

Katherine Ashford has gone missing.

The police visited my studio asking about the wedding photographs.

I showed them the proofs but I did not mention the negative I had retained.

Looking at that photograph again, I see something I wish I had recognized at the time.

There is a wrongness in it that I cannot fully articulate, but it is there captured in silver and light.

Crane had died in 1911, and his studio had been sold.

The new owner had discovered boxes of old negatives and photographs, including the unclaimed images from various weddings.

These had eventually been passed down through the family until Margaret Witmore had found them in her greatgrandfather’s estate.

Sarah and the team of investigators now faced a profound question.

What could be done with this information? The crimes, if crimes they were, had occurred over a century ago.

The perpetrators were long dead.

There were no living victims to seek justice for.

No families actively searching for answers.

But there was something else.

A responsibility to document what had happened.

To give voice to women whose stories had been silenced.

Detective Morrison proposed creating an official case file that would compile all the evidence, the photographs, the historical records, and the pattern analysis.

This file would be entered into the national database of cold cases, ensuring that the information would be preserved and accessible to future researchers.

These women deserve to be remembered, she said, not just as victims, but as real people whose lives were cut short by violence.

This documentation matters.

Sarah agreed to write a comprehensive report detailing the photographic evidence and its implications.

The report would be published in a journal of forensic history, making the findings available to scholars and investigators.

As she worked on the report, Sarah kept returning to Catherine’s face in the wedding photograph.

That intense expression, those eyes that now seemed to hold knowledge of what was to come.

Had Catherine known even then that she was in danger, had she felt the razor against her side and understood its meaning? The photograph had preserved more than an image.

It had captured a moment of silent threat.

A woman’s fear made permanent in silver hallied crystals.

The publication of Sarah’s report created unexpected ripples.

Genealogologists and family historians began examining their own collections, and several more suspicious wedding photographs emerged from the same period.

The pattern extended beyond New England to other regions, suggesting that the practice of using concealed weapons as tools of control during wedding photographs might have been more widespread than initially thought.

One discovery particularly moved Sarah.

A woman named Jennifer Rothwell, a descendant of Catherine’s older sister, Elellanena, contacted her after reading about the investigation.

Jennifer had been researching her family history and had found a sealed letter among Elellanena’s papers marked to be opened only by family after my death.

Elellanena had died in 1954, and the letter had remained unopened in a box of her personal effects for decades.

Jennifer had discovered it while sorting through inherited items.

The letter, dated 1945, was addressed to Elellanena’s granddaughter.

With Jennifer’s permission, Sarah read the letter.

Its contents provided the final heartbreaking piece of the puzzle.

Elellanor wrote, “I am now an old woman, and soon I will face my judgment.

Before I do, I must confess a truth that has haunted me for nearly 40 years.

My sister Catherine did not simply disappear.

I know what became of her, though I never had the courage to speak of it, while those who might have been held accountable still lived.

” In late October of 1906, just days before Catherine vanished, she came to my home in the middle of the night.

She was terrified.

She showed me a bruise on her side and told me that Thomas had threatened her with a razor.

She said he kept it always near and that he had told her she belonged to him completely, that he could do with her as he wished.

I begged her to leave him, to come stay with me and my husband, but she was afraid.

Divorce was unthinkable and she feared no one would believe her story.

Thomas was well regarded and she worried that she would bring shame to our family.

I convinced her to let me speak to father to ask him to intervene but father refused.

He said that Catherine had made her choice and must abide by it.

He believed that Thomas would settle into married life and that Catherine was being overly emotional.

2 days later, Catherine sent me a brief note.

She said she had decided to make the best of her situation, that she would try to be a good wife.

She said she loved me and asked me to pray for her.

That was the last communication I ever received from her.

When Catherine was reported missing, I went to the police and told them about her visit, about the threats, but Thomas’s lawyer suggested that I was a hysterical woman trying to malign a grieving husband.

My own father supported this characterization, fearing scandal.

The investigation went nowhere.

Thomas moved away and the matter was closed.

But I never believed Catherine simply left.

I believe Thomas killed her.

And I believe father’s refusal to help her made him complicit in her death.

I have lived with this knowledge for my entire life and it has been a terrible burden.

I write this so that future generations will know the truth.

Catherine was not a woman who abandoned her family.

She was a victim of violence, failed by those who should have protected her.

I pray that someday justice will be served, even if only in the court of history and memory.

The letter was signed and notorized, witnessed by Elellanena’s lawyer and a family friend.

Jennifer Rothell wept as Sarah finished reading.

All my life, I heard family stories about great great aunt Catherine, the woman who disappeared.

No one ever spoke about the possibility that she was murdered.

They just said she went away.

With Elellanena’s letter as testimony, Detective Morrison was able to officially reclassify Katherine Ashford’s disappearance as a probable homicide.

While no criminal prosecution was possible, the case file now reflected the truth of what likely happened.

Sarah arranged for the restored wedding photograph to be exhibited at the Salem Historical Society along with Elellanena’s letter and a comprehensive explanation of the historical context.

The exhibition was titled Captured in Silver, Hidden Violence in Victorian Wedding Photographs.

The exhibition included photographs of Catherine before her marriage, diary entries from the period, newspaper clippings, and expert analysis of the photographic evidence.

It drew significant attention not just from history enthusiasts, but from domestic violence advocates who saw in Catherine’s story a reflection of struggles that continued into the present day.

One visitor to the exhibition, a woman in her 70s, spent nearly an hour standing in front of Catherine’s wedding photograph.

When Sarah noticed her, she approached gently.

“Did you know her?” Sarah asked, though she knew it was impossible.

The woman shook her head.

“No, but I recognized something in her eyes.

” “My grandmother was married in 1922, and there was violence in that marriage.

No one spoke of it.

She just endured.

Looking at this photograph, I wonder how many women’s stories have been lost because no one was willing to listen or to look closely enough.

Sarah realized that the significance of Catherine’s photograph extended far beyond one historical mystery.

It represented countless untold stories of women trapped in dangerous situations, their suffering minimized or ignored by those around them.

The photograph had become evidence not just of one crime, but of a broader failure, a society’s unwillingness to protect its most vulnerable members.

Months after the exhibition opened, Sarah received an unusual email.

It was from a man named Robert Ashford, a greatgrandson of Thomas Ashford’s second marriage.

He had read about the investigation and wanted to share something he had found in his grandfather’s papers.

Sarah met with Robert at a coffee shop in Boston.

[music] He brought with him a small leather journal that had belonged to Thomas Ashford.

I found this when I was clearing out my father’s attic, Robert explained.

I never knew much about Thomas’s first marriage.

[music] In our family, it was treated as if it never happened.

Reading this journal, I understand why.

The journal covered the period from 1906 to 1908.

The entries were sporadic and often cryptic, but certain passages made Sarah’s blood run cold.

October 1906.

Catherine understands now the nature of our arrangement.

She is willful, but she will learn obedience.

I have made clear to her the consequences of defiance.

November 1906.

The matter is resolved.

I am free to begin a new.

The family asks questions, but they cannot prove anything.

I am regarded with sympathy.

A wronged husband abandoned by an unstable wife.

It is almost amusing.

December 1906.

I dream of that room sometimes.

The look in her eyes when she realized what was happening.

There is power in that moment.

A power that ordinary men never know.

The journal continued with similar disturbing hints, but never explicitly confessed to murder.

Thomas wrote about his move to Boston, his courtship of his second wife, and his growing business success, all built on the foundation of Catherine’s dowy and trust fund.

The final entry from 1908 was the most chilling.

I keep the photograph locked away, though I look at it sometimes.

It reminds me that I’m not bound by the rules that govern ordinary men.

I held her life in my hands once, captured in that moment by the camera.

In a way, I hold it still.

Robert Ashford looked shaken as Sarah finished reading.

I feel sick knowing I’m related to this man.

What he did to Catherine, it’s unforgivable.

I wanted you to have this journal because I think it’s important that people know the truth.

Sarah added the journal to the case file in the exhibition.

It provided the clearest window yet into Thomas Ashford’s psychology, confirming what the photograph and Ellanena’s letter had suggested.

But one question remained unanswered.

What had Thomas done with Catherine’s body? Detective Morrison had expanded her investigation using modern ground penetrating radar and other technologies to search properties that Thomas Ashford had owned or had access to in 1906.

The search focused on the house on High Street, where the couple had lived briefly, as well as several other locations around Salem.

After weeks of searching, the team found something.

Buried beneath what had been a garden behind the high street property, they discovered human remains.

The bones were sent for analysis, and DNA testing was conducted using samples provided by Jennifer Rothell and other Rothell descendants.

The results came back several months later.

The remains were those of a young woman approximately 20 to 25 years old who had died around 1906.

The DNA was consistent with the Rothwell family line.

Catherine had been found.

Further analysis revealed evidence of trauma to the bones consistent with knife wounds.

She had been buried wrapped in what appeared to be household linens, suggesting that the burial had been hasty and improvised.

If you’ve made it this far in Catherine’s story, please leave a comment below sharing your thoughts.

These historical cases matter, and your engagement helps ensure they’re not forgotten.

Catherine’s remains were given a proper burial in the Rothell family plot.

A new headstone was erected, replacing the empty memorial that had been placed there in 1910.

The inscription read, “Catherine Rothell Ashford, 1884 1906.

beloved daughter and sister.

Her story silenced in life but remembered in death.

A memorial service was held attended by descendants of the Rothell family, members of the historical society, and advocates from domestic violence organizations.

Sarah spoke at the service, reflecting on how Catherine’s photograph had led to this moment of recognition and remembrance.

Catherine’s wedding photograph captured something terrible, Sarah said.

But it also preserved evidence that eventually revealed the truth.

We cannot change what happened to her, but we can ensure that she is remembered not just as a victim, but as a person whose life mattered, whose story deserves to be told.

The exhibition at the Salem Historical Society became permanent, expanded to include information about Catherine’s discovery and burial.

It served as both a historical record and an educational tool, helping visitors understand the realities of domestic violence across different eras.

But even with Catherine found and the truth documented, mysteries remained.

The photograph itself continued to provoke questions that had no clear answers.

Why had Thomas chosen to hold the razor during the wedding photograph? Was it purely a gesture of control, or had there been some other significance to him? Had he known the photographer would capture it, or had he believed it would remain hidden? And what about Edmund Crane, the photographer, who had recognized something wrong, but hadn’t acted more decisively? Could he have prevented Catherine’s death if he had gone to the police with his concerns? These questions had no definitive answers.

They existed in the space between what could be proven and what could only be inferred.

A space where historical mysteries often resided.

Sarah continued her restoration work, but she approached each old photograph differently.

Now she looked more carefully at the details, at the body language and positioning of subjects, at the small anomalies that might reveal larger truths.

She wondered how many other photographs existed in archives and attics holding secrets that no one had yet discovered.

How many other stories waited to be uncovered, voices waiting to be heard across the decades? The photograph of Catherine and Thomas Ashford had become something more than evidence of a crime.

It had become a reminder that images could bear witness, that careful observation could reveal what had been deliberately hidden, and that the past was never truly silent.

It only waited for someone willing to listen.

Years later, Sarah would sometimes take out the restored photograph and study it.

Catherine’s face, preserved forever at 22, looked back at her, that intense expression, those knowing eyes.

Sarah liked to imagine that Catherine would be glad her story was finally told, that the truth had emerged from the shadows where Thomas had tried to bury it.

The mystery of what truly happened in those final moments, the exact circumstances of Catherine’s death, what she thought and felt, whether she had fought back or pleaded for mercy, these details were [music] lost to time.

The photograph couldn’t answer everything, but it had answered enough.

It had given Catherine back her voice, her story, her place in history.

And perhaps that was the most important mystery it had solved.

Not just how she died, but that she had lived, that she had mattered, that she would be remembered.

The photograph remained on display at the Salem Historical Society, a silent witness to tragedy and truth.

Visitors came to see it, to look at the groom’s hand and the barely visible shape of the razor beneath the fabric, to see Katherine’s eyes and wonder what she knew and the mystery.

The question of what really happened in that moment when the photograph was taken, what passed between Catherine and Thomas, what she felt and feared.

That mystery remained suspended in silver and light, never fully resolved, never completely explained.

Some mysteries, Sarah had learned, were meant to remain mysteries.

Not because the truth couldn’t be found, but because the truth was complex and human and impossible to fully capture, even in a photograph, even after a century of investigation.

Catherine’s story had been silenced for over a hundred years.

Now, it was told, and perhaps that was enough.

If you enjoyed this deep dive into Catherine’s tragic story, please leave a comment below.

sharing what you think about this case.

I love reading your thoughts and answering your questions.

If you haven’t subscribed yet, make sure to hit that subscribe button and turn on notifications so you don’t miss future videos exploring more hidden mysteries and forgotten stories from the past.

Thanks so much for watching and I’ll see you in the next video.

>> [music]

News

Ilhan Omar ‘PLANS TO FLEE’…. as FBI Questions $30 MILLION NET WORTH

So, while Bavino is cracking down in Minnesota, House Republicans turning the heat up on Ilhan Omar. They want to…

FBI & ICE Raid Walz & Mayor’s Properties In Minnesota LINKED To Somali Fentanyl Network

IC and the FBI move on Minnesota, touching the offices of Governor Tim Walls and the state’s biggest mayors as…

FBI RAIDS Massive LA Taxi Empire – You Won’t Believe What They Found Inside!

On a Tuesday morning, the dispatch radios in hundreds of Los Angeles taxi cabs suddenly stopped playing route assignments. Instead,…

Brandon Frugal Finally Revealed What Forced Production to Halt in Season 7 of Skinwalker Ranch….

The Secret of Skinwalker Ranch became History Channel’s biggest hit. Six successful seasons documenting the unknown with real science and…

1 MINUTE AGO: What FBI Found In Hulk Hogan’s Mansion Will Leave You Shocked….

The FBI didn’t plan to walk into a media firestorm, but the moment agents stepped into Hulk Hogan’s Clearwater mansion,…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage… It started like any other evening…

End of content

No more pages to load