The rope burns told the story before anyone found the body.

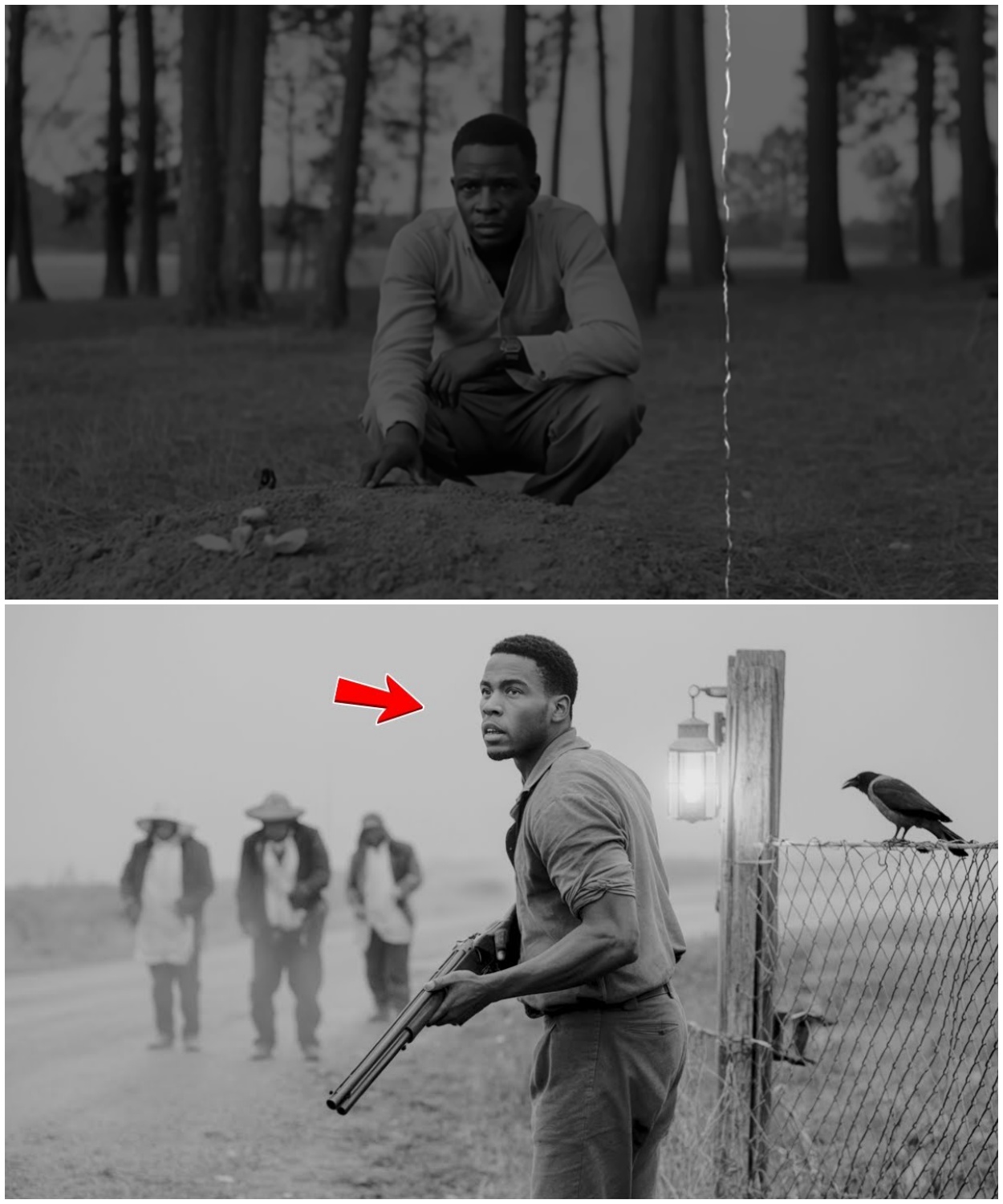

Isaac Woodard stood in the pre-dawn fog of a Georgia pine grove, 1866, staring at marks carved into bark where his younger brother Samuel had clawed for life while the clan hauled him skyward.

The hemp had left grooves in the branch overhead, deep as knife wounds, and beneath it all, scattered white fabric, a torn hood, bootprints heading east toward town.

Samuel had been 23 years old, freed 18 months, learning to read at the missionary school.

His crime, walking past a white woman without stepping off the boardwalk.

Isaac’s hands didn’t shake as he cut his brother down.

They’d shaken plenty in the darkness, carrying Samuel’s cold weight home through woods that whispered with night birds and distant laughter.

But now, kneeling beside the shallow grave he dug alone because no one else would risk being seen helping.

His fingers worked with surgical precision.

He wasn’t burying just a brother.

He was burying the part of himself that believed freedom meant safety.

The clan chapter that killed Samuel operated out of Miller County, Georgia, a stretch of clay roads and cotton fields, where reconstruction hadn’t reconstructed much except fear.

27 members strong.

They met Tuesdays at midnight in the burnedout Baptist church on the edge of town.

Their horses tied outside while they planned which freed slaves needed reminding of their place.

The local sheriff, a man named Clayton Deer, kept meticulous records, not of crimes, but of complaints.

Every black family who stepped out of line, every school that opened, every acre purchased, noted in his ledger with the care of an accountant tracking debts.

Isaac had been a scout for the Union Army, 54th Massachusetts Infantry, trained to move through enemy territory without sound or trace.

He’d mapped Confederate supply lines, identified targets, vanished before dawn.

Those skills hadn’t faded with appamatics.

Now he used them for a different campaign.

The first clansman died three weeks after Samuel’s lynching.

Thomas Pritchard, a milleman who’d boasted about the hanging at the general store, was found at the bottom of his own well with a shattered neck.

The town called it an accident, drunk, slipped on moss.

Tragic.

But someone had nailed a white hood to his front door at midnight, and the message didn’t require translation.

The clan held an emergency meeting that Thursday.

Voices raised about Union agitators, about carpet bagger revenge, about anything except the possibility that one of their victims might fight back because that was unthinkable.

From Sheriff Deer’s journal, October 8th, 1866.

Pritchard incident unsettles the men.

Some talk of federal troops.

None suspect the truth.

The second death came faster.

Martin Hayes, who’d held the torch during Samuel’s lynching, went hunting in the river bottoms and never returned.

They found him four days later, his rifle unfired beside him, throat cut with what the coroner called military precision.

Another hood appeared, this time on the church steps where the clan met.

The fabric was stained, mud maybe, or something darker, and pinned with a note in careful script.

25 remain.

Isaac had learned patience in the war, waiting hours in marsh for the right moment to strike.

He applied that patience now, watching the clan’s patterns from tree lines and rooftops, noting who walked alone, who drank too much, who took shortcuts through unlit alleys.

He mapped their fear the way he’d once mapped enemy positions, identifying weak points, calculating trajectories.

The third killing broke something in the chapter’s confidence.

Robert Finch, a tobacco farmer who’d laughed loudest while Samuel swung, was discovered in his barn with his own pitchfork through his chest.

The weapon had been driven with enough force to pin him to the wooden wall, and his clan robe was draped across a nearby stall, arranged like a scarecrow, watching his corpse.

This time, three families packed their belongings and left Miller County without explanation, and the clan meeting that Tuesday had only 19 men in attendance.

The hunters were learning what it felt like to be hunted.

But here’s what Isaac understood that they didn’t.

Fear is a weapon sharper than any blade, and silence cuts deeper than screams.

Every clansman who died did so quietly without witness.

Their bodies discovered only after Isaac had melted back into the freedman’s quarter, where dozens of people would swear he’d been present all night.

The White Hoods kept appearing.

warnings, tallies, promises, and with each one, the remaining clansmen looked at each other with fresh suspicion.

Was it Yankees? Was it another chapter settling scores? Was it possible that the black man they’d terrorized for sport had become their executioner? They’d find out soon enough because Isaac Woodard wasn’t done counting.

And Sheriff Clayton Deer’s name was circled in ink on a list that Isaac kept folded against his heart.

A list written in his brother’s hand.

Names Samuel had overheard and recorded before they killed him for the crime of literacy.

22 clansmen left and one of them wore a badge.

The smell of leather and tobacco smoke filled Clayton Deer’s office on Main Street, mixing with the metallic tang of gun oil and something older.

The scent of secrets kept in locked drawers.

Sheriff Deer had ruled Miller County for eight years.

First as a Confederate provice marshal, then as the man who made sure reconstruction stayed a word on paper rather than a fact on the ground.

His office sat above the county jail, three cells that rarely held white men.

And from his window, he could watch the entire town square, noting who spoke to whom, who gathered where.

Control, he’d learned during the war came from information.

Fear came from unpredictability.

Together, they kept order.

But order was fracturing.

He spread the reports across his desk that November morning, 1866.

Three dead clansmen in six weeks.

Each death stranger than the last.

Pritchard’s well accident.

Hayes’s throat in the bottoms.

Finch’s barn crucifixion.

And those hoods appearing like accusations counting down numbers that made his hand twitch toward the whiskey drawer.

The chapter had lost eight more men to departure.

Families fleeing in wagons at dawn, citing business elsewhere, eyes haunted.

11 remained.

11 plus himself.

From the Miller County Register, November 12th, 1866.

Recent tragedies attributed to lawless elements.

Sheriff Deer assures citizens that investigations continue.

Federal troops not required.

Deer had built his clan chapter carefully, recruiting men who understood that power required enforcement, and enforcement required fear.

After Lincoln’s bullet and Johnson’s weakness, they’d reclaimed what the war had stolen.

Not land or wealth, but certainty.

The certainty that white men stood above, and freed slaves knew their place below.

Samuel Woodard’s lynching had been textbook.

A visible lesson, a public demonstration witnessed by enough people to spread the message without creating enough fuss to draw federal attention.

But someone was rewriting the lesson.

The fourth killing happened the night after Deer’s newspaper assurance.

James Bullock, who’d supplied the rope for Samuel’s hanging, was found in the church cemetery at dawn, buried to his neck in fresh turned earth, suffocated by soil.

His clan robe was spread across the grave like a blanket and carved into the nearby oak, the same tree where the chapter had burned across the week before Samuel died.

Were four words.

10 more after you.

The math was changing.

10 clansmen left, not counting deer.

That morning, three more families left town.

Seven remained.

Isaac Woodard watched Bulock’s exumation from the blacksmith shop across the cemetery fence, his hands steady on the hammer he was supposedly using to repair a wagon axle.

He’d spent the previous night digging that grave by moonlight, calculating depths, accounting for soil density, timing suffocation to the minute.

The war had taught him engineering, how to collapse tunnels on Confederate supply depots, how to undermine bridge supports, and those principles applied just as well to graves.

Bulock had realized what was happening about 40 seconds before the end.

His muffled screams absorbed by 3 ft of Georgia clay.

No one had come to help.

Isaac had counted on that because the clan’s power had always rested on isolation, on making sure their victims faced terror alone, without witnesses, without recourse.

Now Isaac was teaching them how that felt.

What would you do standing at a grave site knowing the victim had orchestrated your brother’s murder? Would you feel the weight of justice or just the weight of dirt under your fingernails? The remaining clansmen stopped meeting at the church.

Too exposed, too predictable.

They gathered instead at different locations.

Someone’s barn, a hunting cabin, the back room of the general store, changing venues each time, telling no one the location until the last moment.

But Isaac had spent two years infiltrating Confederate camps, and he knew that frightened men developed patterns even when they thought they were being random.

Fear made people predictable.

The fifth death proved it.

William Cobb, the youngest clansman, barely 21, died in his own home while his parents slept in the next room.

They found him at breakfast, seated at the kitchen table with his throat opened, a white hood placed over his head like a burial shroud.

The killer had entered and exited through a window Isaac had watched Cobb leave unlatched for three nights running.

A small habit, a tiny vulnerability.

Enough.

Six clansmen remained.

Sheriff Deer called an emergency meeting that afternoon, gathering the survivors in his locked office.

They came separately, trying not to be seen together, trying not to acknowledge the fear that had them checking shadows and sleeping with loaded rifles.

Deer looked at their faces, pale, exhausted, jumping at footfalls, and realized he was seeing something he’d spent four years of war never witnessing.

Confederate soldiers learning what Union slaves had always known.

That nowhere was safe.

That night offered no protection.

That the powerful could become prey.

Federal troops.

Someone suggested.

Why are the district commander? This is terrorism.

And tell them what deer kept his voice level.

That someone’s killing clan members.

They’d send investigators.

Start asking questions.

Find the membership lists.

He tapped the ledger on his desk.

Find connections between us and every lynching, beating, burning from the past two years.

We’d hang from federal rope just as surely.

The room went quiet except for breathing and the tick of the wall clock.

Then what do we do? Martin Pierce asked.

He’d been the one to light Samuel’s p.

The books the young man had been learning from burned in the town square as warning.

Now Pierce’s hands trembled as he rolled a cigarette he’d never light.

Hunt him was the obvious answer.

Find whoever was doing this and make an example that would restore the old order.

But hunting required knowing who.

And none of them would say aloud what they were all thinking.

that the killer might be one of Samuel Woodard’s people, that a freed slave might possess the skill and rage to execute militaryra revenge because admitting that meant admitting everything they’d built was fragile.

Dear made his decision.

We set a trap, he said.

This isn’t random.

The killer knows us, knows our habits, knows who was there the night we hanged the woodarded boy.

He pulled out a map of the county, marking locations.

Next Tuesday, midnight, we announce a meeting at the old church.

Public, loud, make sure word spreads.

But we don’t gather there.

We gather here.

He circled a spot two miles north in the tobacco barn, armed, waiting.

When our killer arrives at the church, we take him.

It was a solid plan built on bait and patience.

It would have worked if Isaac hadn’t been listening through the office floor vent the entire time, crouched in the darkness of the jail cell below, where he’d picked the lock an hour before the meeting started.

Six clansmen left and one sheriff.

Seven more lessons to teach.

The autumn wind carried the scent of curing tobacco and kerosene through the barn’s plank walls, mixing with the nervous sweat of six armed men crouched in darkness.

Sheriff Deer had chosen the location well.

A weathered structure three miles from town, surrounded by open fields that would reveal anyone approaching with sightelines that covered every angle of approach.

The clansmen had positioned themselves in the loft and behind stacked crates, rifles loaded, watching the single road that led from town toward the decoy meeting site at the old church.

It was 10:45 p.

m.

Tuesday, November 20th, 1866.

In 15 minutes, whoever had been hunting them would arrive at the empty church and find nothing but shadows.

Then they’d spring the trap.

Deer checked his pocket watch by candle light, shielded so it wouldn’t show through the cracks.

Martin Pierce was stationed at the north window, hands finally steady now that he held a weapon instead of fear.

The others, Davis, Monroe, Tucker, and Henderson, were spread throughout the barn, each covering an approach.

Seven men total, seven triggers waiting.

What they didn’t know was that Isaac Woodard wasn’t approaching.

He was already inside.

The crawl space beneath the tobacco barn’s floorboards was tight, barely 2 ft of clearance, packed with decades of dried leaf chaff and rat droppings, but Isaac had squeezed into tighter spaces during the war.

He’d entered through the exterior vent 3 hours earlier before sunset while deer was still gathering his men in town.

Now he lay motionless in the darkness below their boots, listening to their breathing, their whispered conversations, the creek of wood as they shifted positions.

Above him, through gaps in the floorboards, he could see fragments.

a boot heel, the barrel of a rifle, the edge of a lantern’s glow.

He’d brought four things with him into that crawl space.

A knife, a coil of rope, a tin of kerosene, and the patience he’d learned during 18 months of scouting behind enemy lines.

And he had time because while they thought they were hunting him at the church, he was already hunting them here.

from a recovered letter.

Date unknown.

The hardest part of war isn’t the killing.

It’s the waiting before it.

That’s when men show you who they really are.

At 11 p.

m.

exactly, a horse and rider approached the old church 2 miles south.

A freedman named Moses Carter, whom Isaac had paid $5 to wear a dark coat and ride past at the agreed upon time.

The clansmen in the barn tensed, hands tightening on weapons, watching the road for any sign that their trap had been discovered.

But the night remained quiet, and after 30 minutes of nothing, doubt began spreading through the group like rot through timber.

“Maybe he’s not coming,” Tucker whispered from the loft.

He’ll come, dear replied, though his voice carried less certainty than his words.

He’s been too consistent, too methodical.

He won’t pass up a meeting.

But Isaac had never intended to attend their meeting.

He was holding his own.

At 11:45 p.

m.

, Isaac began moving through the crawl space with the silence that had kept him alive through two years of Confederate territory.

He navigated by memory and touch, positioning himself beneath the spot where Martin Pierce stood guard at the north window.

Through the floorboard gaps, Isaac could see Pierce’s boots, the hem of his trousers, the occasional shift of weight from left foot to right.

Pierce was the one who’d lit Samuel’s books on fire.

Isaac had watched from the crowd, required to stand and witness like all the other freed people.

making sure they saw what happened to literacy, to aspiration, to the idea that freedom meant more than breathing.

Now Pierce would learn what it meant to stand on unstable ground.

The knife Isaac carried was a Bowie blade, 13 in of carbon steel he’d taken from a Confederate officer in Virginia.

He pressed it up through a gap in the floorboards, slowly, incrementally testing resistance.

until the tip found the seam between two planks directly beneath Pierce’s left boot.

Then he began applying pressure, working the blade like a lever, creating a gap wide enough for what came next.

The rope was next, threaded up through the widened gap, formed into a noose.

Pierce never looked down.

None of them did.

They were watching for threats from outside.

from the darkness beyond the barn, from the roads and tree lines where danger was supposed to come from.

The concept that death might rise from below them, from the foundation they stood on, never occurred to men who’d spent their lives standing on the backs of others.

At 12:15 a.

m.

, Isaac pulled.

The rope snapped tight around Pierce’s ankle.

He had half a second to register confusion before Isaac yanked him off balance, sending him crashing through the weakened floorboards in an explosion of splinters and dust.

Pierce fell into the crawl space with a choked scream, landing hard on his back, and Isaac was already moving, knife finding ribs with the precision of someone who’d studied anatomy in field hospitals, who knew exactly where to cut to silence without ceremony.

The others froze.

That critical moment of incomprehension when the brain struggles to process impossible information.

Then chaos erupted.

“He’s in the floor,” someone shouted, and rifle shots punched through the floorboards, blind firing into the crawl space, muzzle flashes strobing the darkness.

But Isaac had already rolled away from Pierce’s body, moving along the barn’s foundation toward the next position.

Wood chips and splinters rained down as the clansmen fired frantically, hitting nothing but dirt and their own panic.

Deer tried to restore order.

Stop shooting.

You’ll hit each other.

Get outside and cover the exits.

But Isaac had already reached the support beam at the barn’s southwest corner, the one he’d partially sawed through the previous night while they slept in their beds.

He kicked it once hard and the barn’s roof sagged with a groan of failing timber.

Monroe, positioned in the loft, scrambled backward as the structure shifted, and his weight was enough to complete the collapse.

The entire northwest section of the roof came down in a crash of shingles and beams, and Monroe went with it, crushed beneath tobaccoented wreckage.

Five clansmen left, plus deer.

“Out! Everyone out!” Deer commanded.

But Isaac had anticipated this, too.

The kerosene tin he’d planted near the lantern, hidden behind a crate rigged to tip when the roof collapsed, had already spilled its contents across the dry tobacco leaves.

The open flame met the fuel, and fire spread with the hunger of something that had been waiting for permission.

The barn became an oven.

Henderson made it to the door first, stumbling into the night air, and Isaac rose from the crawl space through the exterior vent, emerging behind him like something born from smoke.

Henderson was still coughing, still trying to orient himself when the rope, already looped, already prepared, settled around his neck.

Isaac hauled him backward into the darkness before Henderson could scream, before the others could see.

And by the time Davis and Tucker burst through the door, Henderson was already gone, dragged into the tall grass where Isaac had cashed supplies for exactly this scenario.

Four clansmen and one sheriff remained inside the burning barn.

The mathematics of revenge were becoming clear.

Dear finally understood, not gradually, but all at once, with the clarity that comes when every assumption collapses.

This wasn’t random violence.

This wasn’t federal troops or rival clansmen or lawless chaos.

This was military strategy executed by someone who’d learned warfare from professionals, who’d planned every contingency, who’d turned their own trap into his killing ground.

This was Isaac Woodard.

And deer had been circled on a list the entire time.

The sheriff made it outside with Davis and Tucker.

The three of them retreating from the flames.

Rifles raised, scanning the darkness that suddenly seemed full of threats.

Behind them, the barn collapsed inward, sending sparks spiraling into the November sky like accusations seeking heaven.

“We need horses!” Davis gasped.

“We need to get back to town.

Get help.

Get the sentence ended when Tucker’s head snapped sideways, rope appearing around his throat from the darkness, yanking him off his feet and into the shadows with the efficiency of a stage hook.

Davis fired blindly in that direction, accomplishing nothing but revealing his position.

And when he turned to run, Isaac stepped from behind a tree and drove the knife between his shoulders, dropping him without ceremony.

Two men left standing in the firelight.

Sheriff Clayton Deer and Isaac Woodard.

The Hunter and the Hunted, finally face to face.

Except Deer was no longer certain which role he played.

The barnfire cast dancing shadows across Clayton Deer’s face, illuminating features that had sentenced men without trial and called it order.

Isaac stepped into the light’s edge 50 ft away.

The Bowie knife still dark with Davis’s blood.

He’d removed his hat, letting deer see him fully, not as some phantom Union soldier or faceless avenger, but as Isaac Woodard, the man whose brother had died for walking on a sidewalk.

The man Deer had watched from his office window the day Samuel’s body was dragged through town as warning.

Recognition hit Deer like cold water.

you.

” The sheriff breathed.

His rifle was raised, aimed center mass, but his hands had developed a tremor that made the barrel waver.

“You’re just one man.

One one man with a brother.

” Isaac interrupted.

His voice was quiet, almost conversational.

The tone of someone discussing weather or crop prices.

Samuel Woodard, 23 years old.

You wrote his name in your ledger under disciplinary actions required.

I found the entry dated August 15th, 1866.

Deer’s finger tightened on the trigger, but something stopped him from firing.

Perhaps the certainty in Isaac’s posture, the way he stood completely still despite the rifle aimed at his chest, as if bullets were merely theoretical concerns.

Or perhaps it was the mathematics.

Seven clansmen dead or missing in the past 90 minutes, executed with the precision of someone for whom killing had become routine.

You can’t prove anything, dear said, falling back on authority like a man clutching driftwood.

I’m a lawful sheriff.

You’re a murderer.

Even if you kill me, there are federal troops, marshals, courts, courts that wouldn’t let my brother testify, Isaac replied.

Marshalss who looked away while you burned his books.

Federal troops who left last month because Johnson recalled them.

He took one step forward.

You built a system where we had no recourse, no protection, no voice.

Now you complain that I’m not using legal channels.

The fire popped behind them, sending embers skyward.

Deer made his decision and fired.

The shot went wide, not from mercy, but from hands that had forgotten steadiness under pressure.

Isaac moved before the echo finished, closing the distance with the speed that had kept him alive through 18 months of Confederate territory.

He slapped the rifle barrel aside as deer tried to work the bolt, and the two men collided in a tangle of violence that had nothing to do with technique and everything to do with desperation.

They went down hard, rolling through ash and grass, trading blows that carried the weight of competing certainties.

Deer fought with the strength of someone defending a world order.

Isaac with the fury of someone who’d already lost everything that world could take.

The knife had fallen during the tackle.

And now it became a race.

Both men scrambling toward the blade while trying to pin the other.

Deer reached it first.

He drove the Bowie upward toward Isaac’s ribs, but Isaac caught the wrist, redirected the thrust past his side, then brought his elbow down on Deer’s forearm with enough force to make bone creek.

The knife tumbled free again, and Isaac’s fist found Deer’s jaw.

Once, twice, three times, until the sheriff’s resistance became reflexive rather than intentional.

Isaac retrieved the knife and pressed it against Deer’s throat, hard enough to draw a thin line of blood, but not deep enough to finish the job.

Both men were breathing hard, faces inches apart, close enough to see the others humanity and choose whether that mattered.

My brother begged,” Isaac said quietly.

“While you watched, while 26 of your brothers in white held torches and cheered.

” He begged for his life and you laughed.

Dear tried to speak, but the blade pressed harder.

Don’t, Isaac continued.

Don’t tell me he should have known his place.

Don’t tell me it was necessary.

Don’t insult me with justifications.

He shifted his weight, pinning deer completely.

You’re going to die tonight.

The only question is how you spend your last minutes.

Begging like Samuel or accepting what’s coming.

The sheriff’s eyes darted toward the distant road, toward town, toward rescue that wasn’t coming.

Then something shifted in his expression.

Not acceptance exactly, but a kind of exhausted resignation.

You won’t stop with me, dear said.

There are others, other chapters, other towns.

You kill me and you become exactly what we said you were.

proof that freed slaves are dangerous, that reconstruction needs to fail.

Isaac’s laugh was sharp and humorless.

You think I care what story you tell after you’re dead? You think I’m worried about your propaganda? He leaned closer.

I’m not making a statement.

I’m settling accounts.

But here’s what Isaac understood.

That deer didn’t.

Every death had been strategic, not emotional.

Every killing had sent a message to the living as much as it punished the dead.

The hoods on doors, the public discoveries, the escalating fear.

It wasn’t random violence.

It was psychological warfare designed to shatter the clan’s sense of invincibility.

And Clayton Deer’s death needed to be public.

Isaac hauled the sheriff to his feet, keeping the knife at his throat.

“Walk,” he commanded, directing deer toward the road that led back to town.

Behind them, the tobacco barn collapsed entirely.

A funeral p for the men who’d built their power on fear, and discovered too late that fear cuts both ways.

They walked for 20 minutes in silence except for the crunch of gravel under boots and deers labored breathing.

The sheriff tried talking several times, offering deals, making threats, attempting reason, but Isaac remained silent, focused on the destination he’d chosen weeks ago when planning this endgame.

The old Baptist church appeared ahead, the one where the clan had held their meetings, where they’d gathered to celebrate Samuel’s lynching.

It sat dark and abandoned, but Isaac had prepared it carefully.

Inside, he’d arranged seven white hoods in a semicircle around the altar, each stained with tobacco barn ash.

In the center, visible through the open door, a noose hung from the ceiling beam.

The same rope they’d used on Samuel, which Isaac had cut down and preserved for this exact purpose.

Dear saw it and understood.

No, he whispered.

Please, I have a family, children.

They don’t.

Samuel had a family, too, Isaac replied.

Me.

He forced deer up the church steps, through the door, into the space where evil had called itself righteous.

The hoods watched like a jury, and the noose waited like a verdict.

Isaac had done the calculations, the drop, the knot placement, the physics of a clean break versus slow strangulation.

He’d become expert in death’s mechanics, learned its grammar through repetition.

But something made him pause.

Not mercy exactly, not forgiveness, just the recognition that killing deer here now like this would make him exactly what the clan claimed he was, a monster, an animal, something less than human.

And Samuel, who died learning to read, who’d believed education would prove their humanity to people who refused to see it, deserved better than revenge that confirmed every lie they’d told about him.

Isaac lowered the knife.

“I should kill you,” he said finally.

“God knows you’ve earned it, but Samuel believed in something better than us, than both of us.

” He stepped back, releasing deer.

So, here’s what happens instead.

He gestured to the hoods arranged around the altar.

You’re going to gather what’s left of your chapter, the ones who ran, the ones hiding, all of them, and you’re going to tell them the clan is finished in Miller County.

No more meetings, no more lynchings, no more terror.

Isaac’s voice hardened.

Because if I hear different, if I hear about one burned school, one beaten freedman, one crossed burned, I’ll come back and next time I won’t stop at 7.

Dear stared at him, trying to process this unexpected pivot.

You’re letting me go.

I’m giving you a choice, Isaac corrected.

Live with the knowledge that a freed slave spared your life after you took my brothers.

Tell your children that story.

See if they think you were right.

The weight of it living as a walking reminder of powerlessness, of mercy he hadn’t shown, of a moral debt he could never repay, settled across deer’s shoulders like stone.

Sometimes survival is the heavier sentence, but Isaac had made one critical miscalculation, and Clayton Deer saw it immediately.

The sheriff was a man who’d built his entire identity on never appearing weak, never backing down, never letting the people he’d oppressed see him humbled.

And humiliation for men like deer was a wound that demanded reopening.

The moment Isaac turned to leave, deer grabbed the fallen rifle from the church corner where it had been leaning and fired.

The gunshot echoed through the church like a congregation’s final amen, and Isaac Woodard dropped.

He hit the floorboards hard, blood spreading from his left shoulder where the bullet had caught him mid turn.

The Bowie knife skittered across the wood, spinning to rest against the altar steps.

For three seconds, neither man moved.

Deer still holding the smoking rifle, Isaac sprawled and bleeding, both processing the sudden reversal that had transformed Mercy into mistake.

Then Isaac’s right hand moved toward his belt, toward the revolver he’ taken from Henderson hours earlier, and Deer fired again.

The second shot missed, punching through the church wall behind Isaac’s head.

And by the time Deer worked the bolt for a third round, Isaac had rolled behind the front pew, using the heavy oak for cover.

Blood left a trail across the floor like accusation, and Isaac’s left arm hung useless.

The shoulder wound deep enough to steal strength and coordination.

He pressed against the wood, breathing through gritted teeth, recalculating odds that had shifted dramatically in the past 10 seconds.

“You should have killed me,” Dear called out, his voice steadier now that he held the advantage.

“That was your mistake, thinking mercy meant anything to men like me.

” Isaac said nothing, conserving energy, assessing options.

The revolver was in his right hand, loaded with four rounds.

Deer had a rifle with superior range and at least three more cartridges.

The church offered limited cover, pews, the altar, perhaps the door if he could reach it.

But movement would expose him, and his left side was compromised.

Blood loss would weaken him within minutes.

The mathematics had turned hostile.

Here’s what happens now.

Deer continued, moving laterally to get a better angle on Isaac’s position.

I finish what should have been done properly.

Then I ride back to town and tell them the truth.

That the murderer who killed my men attacked me in this church.

That I defended myself.

That justice was served.

His boots creaked on the floorboards.

Your body tells the story I need it to tell.

Isaac’s vision blurred briefly, then sharpened.

The shoulder wound was bad, but not immediately fatal if he could stop the bleeding.

He used his right hand to tear a strip from his shirt, awkwardly wedging it against the entry wound while keeping the revolver ready.

The pain was sharp enough to cut through thought, but he’d learned during the war to partition suffering, acknowledge it, then set it aside like a tool not currently needed.

Samuel believed in better, Isaac said, his voice carrying despite the pain.

You proved him wrong in 30 seconds.

Your brother was a fool, dear replied.

And there was genuine contempt in his voice now.

no longer disguised by fear or strategy.

Thinking that reading would make him equal, that freedom meant anything more than breathing, he fired through the pew, the bullet splintering wood inches from Isaac’s head.

We tolerated you people as property, as freed labor, you’re just competition, and competition gets eliminated.

The honesty was almost refreshing.

No pretense of law or order, no claims of Christian duty, just naked acknowledgment that the clan existed to preserve hierarchy through violence.

Isaac had always suspected this truth beneath the rhetoric.

Now it was stated plainly in a church where they’d prayed before lynchings.

He needed to move.

Staying pinned meant bleeding out or taking a bullet that actually hit.

But deer had positioned himself well, covering the door and the aisle, making any dash for escape a gamble Isaac couldn’t afford, with one arm compromised.

So he changed the game.

Your ledger, Isaac called out.

The one in your office.

I made copies, sent them to the District Marshall in Atlanta, the Freriedman’s Bureau in Savannah, and three northern newspapers.

It was partially true.

He’d copied key pages, hidden them with Moses Carter, but hadn’t mailed them yet.

Insurance waiting for the right moment.

You kill me and those documents still exist.

Every name, every disciplinary action, every clansman in Miller County identified for federal prosecution.

Dear’s footsteps stopped.

“You’re lying,” he said, but uncertainty had crept into his voice.

The Henderson family lynching, April 2nd, 1865.

Isaac recited from memory.

The Williams barn burning, June 15th, 1865.

The Cooper shooting, January 9th, 1866.

He paused.

27 incidents documented in your handwriting, Clayton, with dates, locations, and participants.

Think the Union Army won’t be interested.

The bluff was calculated.

Deer knew his ledger existed.

Knew it contained damning evidence.

Couldn’t be certain whether Isaac had actually accessed and copied it.

And that uncertainty, that possibility of exposure, even in victory, was enough to make him hesitate.

Isaac used that hesitation.

He rolled left away from his blood trail, coming up behind a different pew with the revolver raised.

Deer spun toward the movement and fired, but the shot went high, anticipating where Isaac had been rather than where he’d moved.

Isaac returned fire twice, not aiming for center mass, which would be difficult with one arm, but for Deer’s legs, aiming to disable rather than kill.

The first shot missed.

The second caught Deer’s right thigh, and the sheriff went down hard, his rifle clattering across the floor.

Both men were wounded now, both bleeding, the church filling with guns smoke and the copper smell of shared mortality.

Isaac stood, swaying slightly, his left arm dead weight.

Deer clutched his leg, trying to reach the fallen rifle with his fingertips, coming up inches short.

They stared at each other across 12 ft of separation.

Two men who’ tried mercy and violence in equal measure, both learning that neither was simple.

“You were right,” Isaac said finally.

“I should have killed you.

” Samuel’s way, believing in better, got him hanged.

He raised the revolver, sighting down the barrel at Deer’s chest.

So, here’s the lesson I learned tonight.

Mercy is a luxury freed slaves can’t afford.

His finger tightened on the trigger, but before he could fire, the church door burst open and Moses Carter stood silhouetted against the knight.

A shotgun braced against his shoulder.

“Don’t,” Moses said quietly, the weapon aimed at Isaac.

“Not dear.

Not like this.

” Isaac froze, confusion cutting through pain.

Moses was supposed to be gone, paid and sent north, out of danger.

But here he stood, intervening, protecting the very man who’d terrorized them both for years.

Move, Isaac commanded.

This doesn’t concern you.

It concerns all of us, Moses replied.

He was 73, a freed slave who’d survived four decades of bondage and two years of reconstruction’s false promises.

You kill him execution style, wounded in a church.

That’s not justice.

That’s just us becoming them.

He kept the shotgun steady.

Samuel wouldn’t want this.

You know, he wouldn’t.

The weight of it settled like chains.

Isaac stood between two futures.

One where he finished what he’d started, where revenge was complete and satisfying and ultimately empty.

another where he let deer live, knowing the sheriff would spend every remaining day plotting how to restore the hierarchy Isaac had shattered.

Both choices felt like losing.

But Moses was right about one thing.

Samuel had died believing education and dignity would prove their humanity.

And Isaac, covered in blood and holding a gun in a church filled with white hoods, was demonstrating the opposite.

That freedom required becoming monsters.

That survival meant surrendering the very principles Samuel had died defending.

The revolver lowered incrementally.

“Get him out of here,” Isaac said to Moses.

“Get him to a doctor and make sure he remembers.

Next time I won’t hesitate.

Moses nodded and helped Deer toward the door.

The sheriff limping badly, leaving his own blood trail beside Isaac’s.

At the threshold, Deer turned back, his face a mixture of pain and calculation.

“This isn’t over,” he said.

“I know,” Isaac replied.

And that’s when they both heard it.

Horses approaching, multiple riders moving fast, drawn by the gunshots or the burning barn or someone in town who’d finally gotten suspicious.

The sound of authority arriving too late to prevent anything but early enough to assign blame.

Isaac and Deer locked eyes one final time, understanding passing between them.

One of them would tell the story.

One of them would shape what happened here tonight into the narrative that defined Miller County’s future.

And whoever held that power would determine whether the clan’s terror ended or evolved.

The horses were getting closer.

The hoof beatats grew louder, splitting the night into before and after.

And Isaac Woodard made a choice that would define everything that followed.

He dropped the revolver, kicked it toward Deer, and pressed both hands, one functional, one useless, against his bleeding shoulder.

When the riders burst through the church door moments later, they found Sheriff Clayton Deer holding a weapon, Isaac unarmed and wounded, and Moses Carter standing between them with a shotgun pointed at no one in particular.

The tableau told a story.

The question was which one? Deputy Marshall Henry Calhoun dismounted first, followed by six mounted men, a mixture of concerned citizens and opportunistic vigilantes drawn by rumors of violence at the old church.

Calhoun was a federal appointee, 32 years old, who’d served with the Union cavalry and understood the politics of reconstruction better than most.

He took in the scene with the practiced eye of someone accustomed to violence disguised as order.

Two wounded men, gunm smoke lingering, white clan hoods arranged like evidence around the altar.

Someone want to explain this? Calhoun asked, his hand resting on his sidearm.

Dear spoke first, as Isaac knew he would.

This man attacked me.

Isaac Woodard.

He’s responsible for killing seven men in this county over the past two months.

I tracked him here, attempted to arrest him, and he opened fire.

The sheriff’s voice carried authority despite his leg wound.

Carter there can confirm it.

All eyes turned to Moses, who stood with the shotgun now lowered, his weathered face unreadable.

Here was the fulcrum, the moment where truth and survival intersected, where one old man’s words would determine whether Isaac lived to see mourning or died at the end of a rope that had nothing to do with justice.

Moses met Isaac’s gaze briefly, then looked at Calhoun.

“That’s not how it happened,” he said quietly.

The church seemed to hold its breath.

I was passing by when I heard shots.

Came inside and found Sheriff Deer standing over Isaac, who was already wounded and unarmed.

Deer was about to execute him.

Moses gestured toward the hoods.

This church is where the clan meets.

Those are their robes.

Isaac came here looking for evidence about who lynched his brother back in August.

Deer tried to silence him.

It was a gamble, contradicting a white sheriff in front of white witnesses, risking everything on the possibility that a federal marshall might actually enforce law equally.

But Moses had lived 73 years watching careful men die just as surely as bold ones.

And sometimes survival meant choosing which risk to take.

Deer’s face flushed.

That’s a lie.

This negro is covering for a murderer.

Then explain the hoods, Calhoun said, walking toward the altar.

He picked one up, examining the ash stains, the careful arrangement.

Explain why we’ve had seven suspicious deaths in this county.

All of the men who’ve been reported attending clan meetings.

He turned to dear.

Explain your ledger.

The silence that followed was profound.

Isaac had been bluffing earlier about sending copies north, but he’d underestimated Moses.

The old man had taken the ledger pages Isaac had shown him weeks ago, insurance that was supposed to stay hidden, and delivered them to Marshall Calhoun’s office in Atlanta.

Not because he believed in federal justice, but because he understood that power required documentation, that accusations needed evidence, that freed slaves couldn’t afford to fight with honor alone.

I don’t know what you’re talking about, dear said, but his voice had lost its certainty.

Calhoun pulled a folded document from his coat.

27 documented incidents of racial violence.

Participants listed by name, dates, locations, methods.

He read from the page.

August 15, 1866.

Disciplinary action required for Samuel Woodard.

Uppidity behavior learning to read.

Chapter voted unanimously for public correction.

The marshall’s voice was flat.

Prosecutorial.

That’s your handwriting, Sheriff.

We had it verified.

The other writers shifted uncomfortably.

Some because they supported the clan and disliked this federal interference.

Others because they’d suspected but never confirmed what happened in the shadows of Miller County’s so-called law enforcement.

Those men attacked first.

Dear tried.

Everything documented was self-defense maintaining order.

Self-defense against a man learning to read.

Calhoun interrupted.

order maintained by burning schools and lynching freed men.

He gestured to his men.

Disarm him.

He’s under arrest for conspiracy to commit murder.

But this was Georgia in 1866, where federal authority existed on paper more than practice.

Where six armed locals who’d ridden with deer suddenly had to choose between obeying a northern marshal or protecting their sheriff.

The mathematics of loyalty shifted like sand.

Three of the riders moved toward Calhoun.

The other three moved toward deer.

The church was about to become a battlefield.

Isaac, still bleeding against the pew, watched the calculation play out on every face.

This was the moment the war had been building toward.

Not the formal conflict that ended at Appamatics, but the real war over what reconstruction would mean.

Whether federal law would protect freed slaves or merely acknowledge them in theory while abandoning them in practice.

Stand down, Calhoun ordered, but his hand was already moving toward his weapon, recognizing that orders only worked when someone enforced them.

What saved everyone temporarily was the sound of more horses approaching.

Lots of them.

The thunder of hooves that suggested not individuals but a column organized and military.

Union cavalry, two dozen strong, appeared in the church doorway behind Calhoun.

Their lieutenant, a young man named Morrison, saluted.

Marshall Calhoun, we received your wire about potential resistance to federal authority.

Reporting as requested, the tide shifted again.

Dear supporters saw their odds evaporate.

You could fight one marshall and gamble on local sympathy.

But you couldn’t fight the United States Army without declaring open rebellion.

The three men backing the sheriff lowered their weapons incrementally, and the crisis dissolved into the more familiar pattern of reluctant compliance.

They took Deer out in irons, his leg bleeding through hastily applied bandages, his face a mask of fury and calculation.

As they dragged him past Isaac, the sheriff leaned close enough to whisper, “This isn’t over.

Federal troops won’t stay forever, and when they leave, so does their protection.

It was a promise and a prophecy.

And Isaac knew deer was right.

The Union cavalry would withdraw eventually, had to withdraw, couldn’t occupy the south indefinitely.

And when they did, whatever protection Isaac had gained tonight would evaporate like morning fog.

But Moses had bought him time, and time, Isaac had learned, was the most valuable weapon in any war.

Calhoun approached Isaac, signaling for a medic.

You’ll need testimony about your brother, about the clan’s operations, about everything you’ve witnessed.

He kept his voice low.

I can’t promise you’ll be safe, even with deer in custody.

His supporters will retaliate.

You should consider relocating north while we prosecute.

Run away, Isaac said.

Not quite a question.

Survive, Calhoun corrected.

There’s a difference.

Was there? Isaac had spent eight weeks hunting the men who killed Samuel, executing them with precision that would have impressed his Union commanders.

Seven dead, one captured, and the clan’s grip on Miller County shattered.

at least temporarily.

But the mathematics of power hadn’t changed.

For every clansman he’d killed, a dozen more existed in neighboring counties.

For every sheriff arrested, another would rise who understood not to keep written records.

The medic worked on Isaac’s shoulder, extracting the bullet and packing the wound.

The pain was sharp and immediate, cutting through the adrenaline fog that had sustained him.

Around him, federal soldiers secured the church, documenting the hoods, taking statements, performing the bureaucratic rituals that transformed violence into evidence.

Moses stood nearby, silent now that his testimony was recorded, watching Isaac with something that might have been concern or judgment or simply exhaustion.

You should have told me you delivered those pages, Isaac said quietly.

You would have stopped me, Moses replied.

Said it was too dangerous, son.

That I was too old to risk myself.

He shrugged.

Sometimes old men are useful precisely because we’re too old to care about risks.

Thank you.

Don’t thank me yet.

You’re alive, but you’re not free.

Not really.

Moses gestured toward the cavalry.

They’ll use you now.

Parade you around.

Make you testify.

Turn you into a symbol.

The freedman who fought back.

The hero who stood up to the clan.

His voice carried no admiration.

Symbols get everyone around them killed.

It was a warning Isaac didn’t fully understand yet, but would learn soon enough.

Even today, old-timers in Miller County claim you can still see blood stains on the church floorboards.

Isaac’s and deers mixed together, impossible to separate, a permanent reminder of the night justice and revenge became indistinguishable.

The Atlanta courthouse smelled of wood polish and old tobacco, mixing with the January cold that seeped through walls built before anyone imagined freed slaves would testify inside them.

Isaac Woodard sat in the witness chair on the morning of January 14th, 1867, his left shoulder still stiff from the bullet wound, facing a gallery packed with spectators who’d traveled from three states to watch what newspapers were calling the reconstruction test case.

Sheriff Clayton Deer sat at the defense table, leg healed but limping, flanked by two attorneys from Charleston, who specialized in making federal charges disappear.

The prosecutor, a Massachusetts lawyer named Abernathy, had built his case around Deer’s ledger and Isaac’s testimony.

Documentation and eyewitness combined to prove conspiracy to commit racially motivated murder.

It should have been straightforward.

27 documented incidents, 12 witnesses willing to testify, physical evidence, including the clan robes found in the church.

But this was Georgia and straightforward had never applied to justice when it crossed color lines.

Judge Harlon Whitfield presided, a local appointment who’d served the Confederacy as a military prosecutor and now served reconstruction with visible reluctance.

He’d allowed the trial to proceed, but had already ruled that Deer’s ledger, being private property seized without warrant, was inadmissible.

That single decision had gutted Abernathy’s case, transforming documented conspiracy into he said she said testimony that judges and juries could dismiss as unreliable negro claims.

Mr.

Woodard Abernathy began standing before the witness chair.

Please tell the court what happened to your brother Samuel on August 15th, 1866.

Isaac had rehearsed this moment for weeks, practicing the narrative until it became smooth enough to survive interruption.

Samuel was walking home from the missionary school where he’d been learning to read.

He passed Margaret Finch on the boardwalk outside the general store.

Didn’t touch her, didn’t speak to her, just walked past.

That evening, men in white robes came to our cabin, dragged him out, and hanged him from a pine tree north of town.

Did you identify any of these men? Yes.

Sheriff Deer was among them.

I recognized his voice when he gave orders, and later I saw his horse, distinctive white blaze on the forehead, tied outside the church where the clan met.

Dear’s lead attorney, a man named Krenshaw, stood immediately.

Objection.

The witness is speculating about my client’s involvement based on a horse that could belong to anyone.

Sustained.

Whitfield ruled without hesitation.

And so it went for three hours.

Isaac providing testimony.

Crenshaw objecting.

Whitfield sustaining.

Every piece of evidence that connected dear to the clan was ruled circumstantial, speculative, or inadmissible.

The gallery watched this judicial dismantling with expressions that ranged from satisfaction to despair, depending on which side of reconstruction they occupied.

During cross-examination, Krenshaw went for the throat.

Mr.

Woodard, isn’t it true that you served as a Union scout during the war? Yes.

And that you were trained in infiltration, reconnaissance, and Cshaw paused meaningfully.

Assassination of Confederate targets.

Isaac saw the trap, but had no way to avoid it.

I was trained to gather intelligence and when necessary, eliminate threats.

Eliminate threats, Krenshaw repeated, turning to the jury.

A polite way of saying murder.

And after the war, you continued eliminating what you perceived as threats, didn’t you? Seven men died in Miller County between September and November of 1866.

All found dead under suspicious circumstances.

All connected to alleged clan activity.

Objection, Abernathy called.

Mr.

Woodard is not on trial here.

But his credibility is, Krenshaw countered.

If he’s a trained killer with motive to harm these men, his testimony against my client becomes suspect.

Overruled.

Whitfield said, “The witness will answer.

” Isaac met Krenshaw’s eyes.

I didn’t kill anyone.

It was technically true.

He hadn’t killed all seven, only six.

Moses had stopped him before he’d finished deer.

But the lie felt heavier than the truth would have, creating a distance between Isaac and Samuel’s memory that hadn’t existed before.

You expect this court to believe, Krenshaw continued, that seven clan members died by coincidence in the same county where you lived, while you, a trained military assassin, remained innocent.

The question hung in the courtroom like smoke.

What Isaac couldn’t say, what the legal framework wouldn’t allow, was that those men had died because the law had failed.

That Sheriff Deer’s badge had made him untouchable until Isaac touched him anyway.

That the very system now demanding Isaac prove Deer’s guilt had created the conditions where extrajudicial killings became the only available justice.

I expect this court, Isaac said slowly, to focus on whether Sheriff Deer conspired to lynch my brother.

Everything else is distraction.

But distraction was the strategy.

By the time Crenaw finished cross-examination, the trial had transformed from people vers dear into questions about Isaac Woodard’s war service.

The jury, 12 white men who’d never left Georgia, looked at Isaac with suspicion that had nothing to do with truth and everything to do with fear that freed slaves might have learned too much from Union training.

During lunch recess, Moses found Isaac in the corridor outside the courtroom.

“They’re going to acquit him,” the old man said without preamble.

Judge has already decided.

This whole trial is theater.

Then why testify? Isaac asked, exhaustion bleeding through.

Why put myself through this? Because sometimes you create records for future courts, not present ones, Moses replied.

Your testimony is written down now.

Can’t be erased.

When reconstruction finally takes hold, if it takes hold, this transcript will exist as proof.

If that single word contained all of Moses’s doubt, all of Isaac’s growing certainty that federal protection was temporary and revenge was permanent.

The afternoon session brought Moses Carter to the stand where he recounted finding Isaac wounded in the church.

Dear standing over him with a weapon, Krenshaw tore into the testimony with barely concealed contempt, suggesting Moses was too old to remember clearly, too loyal to Isaac to testify honestly, too negro to understand legal proceedings.

Judge Whitfield let it happen.

By day three, when Abernathy rested his case, the outcome was predetermined.

Krenshaw didn’t even bother calling witnesses.

Didn’t need to.

He simply argued that the prosecution had failed to prove conspiracy beyond reasonable doubt.

That all evidence was circumstantial, that Sheriff Deer was the real victim here, attacked by a vengeful freerman.

The jury deliberated for 47 minutes, not guilty on all charges.

The gallery erupted, half in celebration, half in despair.

Dear stood, shook his attorney’s hands, and turned to face Isaac with an expression that mixed triumph with promise.

The message was clear.

Federal courts had tried and failed to hold him accountable.

Now local power would reassert itself and there would be consequences for those who challenged it.

Outside the courthouse, reporters surrounded Isaac, asking how he felt about the verdict, whether he planned further action, whether he believed justice was possible in Georgia.

He gave them nothing.

No quotes, no statements, no reactions that could be twisted into evidence for future charges.

Marshall Calhoun pulled him aside as the crowd dispersed.

I’m sorry.

We knew this was possible, but but you hoped.

Isaac finished.

Hope the system would work this time.

There will be appeals, federal oversight, more troops if necessary.

Will there? Isaac asked.

Or will Washington decide reconstruction is too expensive, too difficult, too unpopular with northern voters who are tired of caring about southern justice.

Calhoun had no answer, which was answer enough.

That night, Isaac stood at his hotel window, watching Atlanta’s gas lamps flicker like captured stars.

Moses sat in the room’s single chair, silent for once, letting Isaac process what they’d both known would happen.

Samuel believed education would save us.

Isaac said finally that if we proved ourselves intelligent, hardworking, worthy, they’d accept us as equals.

He touched his shoulder where the bullet scar remained.

I proved I could kill them as efficiently as any white soldier, and they’re still not afraid enough to treat us fairly.

Fear isn’t the same as respect, Moses replied.

No, but it’s more reliable.

The question neither man asked.

What came next? Isaac had exposed the clan, gotten deer arrested, testified in federal court, done everything the system claimed was proper, and accomplished nothing except making himself a target.

Deer was free.

The clan was temporarily disrupted, but already reforming, and Isaac was alive only because federal troops remained stationed nearby.

When those troops left, the mathematics would shift again.

Some say Isaac Woodard stayed in Atlanta for three more weeks, waiting to see if appeals would materialize before finally accepting that justice had been performed without being delivered.

The appearance of law without its substance, a trial that changed nothing except who could claim moral authority.

The train south rattled through February cold, carrying Isaac Woodard back toward the place where everything had started and nothing had changed.

He’d left Atlanta on February 9th, 1867 after receiving word that Moses Carter was dying, not from violence, but from the ordinary cruelty of a body that had survived 73 years of bondage and exhaustion and was finally surrendering.

The telegram had been brief.

Come soon.

He asks for you.

No signature, but Isaac recognized the handwriting.

Ruth, Moses’s daughter, who’d learned her letters in the secret school Samuel had attended before the clan decided literacy was a threat.

Miller County looked different in winterlight.

The cotton fields dormant, the pine trees stark against gray sky, the town square quieter than Isaac remembered.

But the quiet felt tactical rather than peaceful, like breath held before violence.

The federal cavalry that had occupied the county after Deer’s arrest had withdrawn three weeks earlier, recalled North as Washington decided reconstruction required fewer soldiers and more negotiation.

Their departure had created a vacuum that men like Clayton Deer understood how to fill.

The sheriff was back in office.

Not officially, federal authorities still contested his reinstatement, but functionally.

He wore the badge, occupied the office, enforced the kind of order that protected some people by terrorizing others.

The acquitt had made him untouchable, and everyone knew it.

The clan had resumed meetings, though now they were called civic organizations, and their violence was labeled community defense.

Isaac walked through town toward Moses’s cabin, aware of eyes tracking him from storefronts and porches.

Some looks carried recognition, others curiosity, a few outright hostility.

He was famous now.

The freedman who’d hunted clansmen, who testified in federal court, who’d forced powerful men to acknowledge that black lives might matter enough to investigate their deaths.

That fame made him either a hero or a target, depending on perspective.

Moses’s cabin sat at the edge of the Freedman’s quarter, a structure that leaned slightly east, as if even the building was tired.

Ruth met Isaac at the door, her face carrying the exhausted peace of someone who’d already said their goodbyes and was simply waiting for biology to finish.

“He’s awake,” she said quietly.

“Been asking for you since yesterday.

” Inside, the cabin smelled of wood smoke and the particular staleness that accompanies dying.

Not unpleasant exactly, just conclusive.

Moses lay on a cot near the fireplace.

His body reduced to angles and shadows, breathing in careful increments, but his eyes were clear when they found Isaac, and he smiled with something that looked like relief.

“Thought you might not come,” Moses said, his voice thin as paper.

“Thought Atlanta might have convinced you to stay north.

” Isaac pulled a chair close.

You saved my life twice.

Least I can do is be here while you leave yours.

Always was too practical for sentiment, Moses replied.

But there was affection beneath the words.

He shifted slightly, wincing.

Need to tell you something about what happens next about deer.

You should rest.

I’ll rest soon enough.

Moses’s hand found Isaac’s.

The grip surprisingly strong.

Deer’s planning something.

Heard it from Ruth, who heard it from the housemaid who cleans his office.

He’s organizing what he calls a correction, a coordinated action against prominent freedman across three counties, everyone who testified, everyone who supported federal intervention, everyone who made him look weak during the trial.

The list would include Isaac’s name.

when soon before spring planting while people are still gathered in towns rather than dispersed to fields.

Moses coughed, the sound wet and rattling.

He’s learned from what you did.

Won’t make himself vulnerable by acting alone.

This time it’ll be dozens of them moving simultaneously.

Too many targets for anyone to protect.

It was strategic thinking, recognizing that Isaac had succeeded because he’d isolated individual clansmen, picking them off when they were vulnerable.

Dear was ensuring no such vulnerability existed this time.

You’re telling me to run, Isaac said.

I’m telling you that revenge has diminishing returns.

Moses corrected.

You killed six of them, got one arrested, exposed their operation, made them afraid, which is more than most freed slaves manage.

He squeezed Isaac’s hand harder.

But you can’t kill your way to safety.

There’s always more of them, and they’ve got the system behind them.

You proved your point.

Now survive it.

Through the window, Isaac could see the pine grove where Samuel had died.

the same trees, the same grove, probably the same branch.

Five months had passed since he’d cut his brother down.

And in that time, Isaac had become something Samuel would have recognized, but maybe not understood.

A killer, an avenger, a man who’d chosen violence over the education Samuel had died believing him.

What if running just teaches them they can terrorize us into leaving? Isaac asked.

What if survival requires making the cost too high for them to keep trying? And what if? Moses replied, “Making the cost too high also costs you everything Samuel wanted you to be.

” The question sat between them like a third presence.

Moses died three hours later, his breathing simply stopping between one moment and the next, his hand still holding Isaac’s.

Ruth wept quietly while Isaac sat motionless, feeling the weight of another loss.

Another person gone who’d tried to protect him.

Another reminder that survival in Georgia required constant sacrifice.

They buried Moses the next morning in the Freriedman’s cemetery outside town, a patch of land too rocky for farming, donated by a white land owner who’d been more generous with unusable property than basic dignity.

20 people attended, which would have been more except fear kept others away.

The service was brief, led by a traveling minister who understood that lingering invited attention.

As they lowered the coffin, Isaac noticed Clayton Deer watching from the road, sitting on his horse with the casual certainty of someone who knew the law wouldn’t question his presence anywhere.

Their eyes met across a hundred yards of cold earth.

Deer tipped his hat, a gesture that was somehow more threatening than any explicit warning, then rode away.

That night, Isaac sat in Moses’s cabin with Ruth and three others from the Freedman’s Quarter, discussing options that all felt like variations of losing.

They could stay and fight, which meant dying.

They could report Deer’s plans to federal authorities who demonstrated their inability or unwillingness to act.

They could run, which meant abandoning homes and yielding territory to terror.

Moses was right, Ruth said finally.

You can’t win this by killing them.

There’s too many and they control too much.

She looked at Isaac with something between sympathy and accusation.

What you did hunting them, making them afraid.

It felt like justice.

But justice that disappears the moment federal troops leave isn’t justice.

It’s just intermission.

The truth of it settled like frost.

Isaac left Miller County on February 14th, 1867, carrying a small bag, and the knowledge that sometimes survival meant admitting what couldn’t be changed.

He’d proven that freed slaves could fight back, could hunt their oppressors with the same efficiency they’d been hunted.

But individual courage couldn’t overcome.

Systemic power and revenge, no matter how satisfying, couldn’t build the future Samuel had imagined.

On the train north, Isaac wrote a letter he never sent, addressed to his dead brother.

You were right about education being power.

I was right about fear being necessary.

But neither of us understood that power and fear without protection just makes you a target.

I’m leaving Georgia, but I’m not giving up.

Just learning that some fights take longer than one man’s lifetime.

The clan’s correction happened two weeks after Isaac departed.

Eight freed men were killed across Miller County in coordinated attacks.

Their cabins burned, their families scattered, their names added to a list of people who’d tried standing up and learned the cost.

Federal authorities investigated, filed reports, and accomplished nothing.

Clayton Deer served as sheriff for another 11 years.

But even now, old families in Miller County whisper about the winter of 1866.

When white hoods started appearing on doors as warnings instead of the other way around.

When clansmen learned what it felt like to be hunted.

When one freed slave reminded everyone that the powerful stay powerful only as long as the powerless accept that arrangement.

Chicago smelled of stockyards and coal smoke when Isaac Woodard arrived in March of 1867, carrying Moses’s watch and memories that wouldn’t settle into the past where they belonged.

The city was swollen with freed slaves and immigrants, all chasing the promise that northern industrial wages might translate into something resembling freedom.

Isaac found work at a meat packing plant on the south side.

Brutal labor that paid enough to rent a room in a boarding house where nobody asked about scars or what a man had done to earn them.

He used a different name now, Samuel Carter, combining his brother’s first name with Moses’s last, and tried to build the kind of ordinary life that men like Clayton Deer had made impossible in Georgia.

But ordinary required forgetting, and Isaac couldn’t manage it.

At night, he dreamed of pine groves and white hoods, of deer’s face in firelight, of the moment he’d lowered the gun instead of firing.

That choice haunted him more than the six men he’d killed.

Not because he regretted mercy exactly, but because mercy had accomplished nothing except keeping him alive to witness how little one man’s courage mattered against institutionalized terror.

From the Chicago Defender, March 19th, 1913, Isaac Woodard, age 76, died peacefully in his southside home.

A veteran of the Civil War and early reconstruction, Mr.

Woodard spent 46 years working in Chicago’s industrial sector.

He has survived by no immediate family, but will be remembered by the community he quietly served.

The obituary didn’t mention Miller County.

Didn’t mention Samuel or Moses or the winter when Isaac had hunted the clan with military precision.

Didn’t mention that he’d spent 46 years living under an assumed name.

Because going back to Georgia, even decades later, felt like inviting the past to finish what it started.

But here’s what the obituary also didn’t mention.

Isaac never stopped teaching.

In that Chicago boarding house, then later in the small home he purchased in 1900.

Isaac ran a different kind of school.

Not reading and writing.

Plenty of places taught that in Chicago, but something harder.

He taught young black men who’d fled north how to recognize patterns in violence, how to document evidence, how to protect themselves and their communities when law enforcement wouldn’t.

He taught the lessons Moses had tried teaching him.

That survival required both courage and strategy.

That revenge felt satisfying, but protection mattered more.

that individual acts of violence couldn’t substitute for collective organization.

Some of his students went on to found the first black self-defense organizations in Chicago.

Others became lawyers, using the system Isaac had learned to distrust.

A few returned south during the civil rights movement, applying Isaac’s tactical thinking to lunch counter sitins and freedom rides.

Nonviolent resistance that borrowed from military discipline without adopting military methods.

Isaac never knew if Samuel would have approved.

The brother he’ buried believed education alone could save them.

that proving their humanity through literacy and hard work would eventually convince white America to extend full citizenship.

Isaac had learned that wasn’t enough.

That power respected force more than virtue.

That people only granted rights when granting them became less costly than refusing.

But he’d also learned that Moses was right.

You couldn’t kill your way to justice, couldn’t terrorize your way to equality.

The clan had tried that for decades, and all they’d built was a system that required constant violence to maintain.

Isaac had shown that freed slaves could match that violence, could hunt their hunters, could make oppressors afraid.

But matching violence just created cycles that ground everyone down until nobody remembered why they were fighting, only that they had to keep doing it.

The real victory, small and incomplete as it was, came from the students Isaac taught who learned both lessons.

That power had to be confronted, but that confrontation required strategy beyond revenge.

that standing up to terror was necessary, but that standing up had to build towards something more than just getting even.

In 1893, a young lawyer came to Isaac’s home in Chicago carrying documents from Georgia.

Clayton Deer had died two months earlier, the lawyer explained.

And in his estate papers, they’d found Isaac’s real name listed as outstanding debtor.

Some fabricated claim meant to harass Isaac even in death.

The lawyer wanted to fight it.

Thought it could be challenged in court.

Isaac declined.

“Let him have his final word,” Isaac said.

“I’m not interested in fighting ghosts.

” But that night, alone in his home, Isaac allowed himself one moment of satisfaction.

He’d outlived deer by 26 years and counting.

Had built a life, modest but real, that the sheriff’s terror couldn’t erase.

Had taught dozens of young people that survival didn’t require choosing between dignity and safety.

That sometimes the strongest resistance was simply refusing to disappear.

Samuel had been right that education was power.

Isaac had been right that fear was necessary.

And Moses had been right that neither worked alone.

That real change required generation after generation learning from each other’s mistakes, building on each other’s courage, refusing to let individual defeats become permanent conditions.

The work continued long after Isaac died.

Some of his students students marched with Martin Luther King Jr.

Others defended black neighborhoods during the Chicago riots of 1968.

A few became the lawyers and activists who finally dismantled legally, systematically the structures that men like deer had built to maintain white supremacy through terror.

It took a hundred years.

It’s still not finished.

But on February nights in Chicago, when wind carries cold south from the lake, old folks in the neighborhood Isaac lived in still tell stories about the man who’d hunted the clan in Georgia, who’d learned that revenge was necessary but insufficient.

Who’d taught that sometimes the bravest thing a person could do was survive long enough to teach the next generation how to fight smarter than he had.

They say Isaac kept a white hood in his closet until the day he died.

Not as trophy, but as reminder that power built on fear was fragile.

That the oppressed could become oppressors if they weren’t careful.

that the point wasn’t to reverse hierarchies, but to dismantle them entirely, which required patience that felt like cowardice and strategy that felt like surrender, but was actually the hardest kind of courage.

And late at night, they say, if you stand in the Freriedman Cemetery outside Miller County, where Samuel and Moses are buried, you can still hear wind through the pines that sounds almost like singing.

old hymns about freedom that meant different things to different generations.

All of them true, none of them complete.

The clan eventually faded in Miller County, not because Isaac killed six of them or because Deer was arrested, but because federal law finally caught up to what Isaac had demonstrated.

That terror only works when its targets accept it as inevitable.

The moment someone fights back, even if they lose, even if they have to run, even if the victory is just surviving, the math changes.

Fear flows both directions.

And power built on fear alone eventually collapses under its own weight.

Isaac Woodard’s real legacy wasn’t the men he killed.

It was the students he taught who learned to fight without becoming the thing they were fighting against.

who understood that justice required more than revenge, that freedom required more than fear, that change required more than one man’s courage.

It required all of them, and it still does.

We’re only scratching the surface.

The next case is even darker.

Subscribe before it drops.

News

At 91, Shirley MacLaine Finally Tells the Truth About Rob Reiner

At 91, Shirley MacLaine Finally Tells the Truth About Rob Reiner You expect the black sunglasses, the prepared statements issued…

Tracy Reiner REVEALS what Rob Reiner told her before he passed

You have to understand that when the cameras turn off and the red carpets are rolled away, Hollywood is a…

A Case Too Disturbing for Netflix — 200 KKK Riders Never Returned Home

The Federal Investigators report sat in a locked file cabinet in Washington for 43 years before anyone read it again….

Clara of Natchez: Slave Who Poisoned the Entire Plantation Household at Supper