The summer of 1844 was marked by an unspeakable dread that descended upon one of Charleston’s most prominent households.

The events I am about to relate have been pieced together from courthouse records, church registries, personal correspondents, newspaper clippings, and oral testimonies that survived long enough to be recorded by university researchers in the 1960s.

What makes this account particularly disturbing is not the brutality or the bloodshed, though there was certainly enough of that, but rather the methodical patience with which vengeance was exacted.

The Rutled family estate stood 3 mi north of Charleston proper, nestled among the sprawling oak trees draped with Spanish moss that seemed to whisper secrets when the coastal winds swept through.

The main house, with its imposing columns and symmetrical wings, overlooked the Kooper River, where merchant ships would pass on their way to the bustling harbor.

It was in this house that Sarah Elizabeth Rutled, wife of prominent attorney William Harrison Rutled, began to experience the first symptoms of what would later be described as a wasting malady of mysterious origin.

But to understand what truly happened during those humid summer months, we must first step back and examine the household as it existed before death began its quiet harvest.

The Rutled plantation, passed down through four generations, had amassed considerable wealth through rice cultivation and the labor of more than 70 enslaved individuals.

William Harrison Rutled had inherited the estate from his father at the age of 25 and had expanded both the property and its operations through shrewd business dealings and his connections within Charleston’s elite society.

Sarah Elizabeth Rutled, born Sarah Elizabeth Baker, came from an equally prominent Charleston family.

Their marriage in 1835 had been celebrated with one of the most lavish weddings the city had seen that decade, uniting two of the oldest families in the area.

The union had produced three children, Thomas, age 8, Catherine, age 6, and infant James, born in January of 1844.

To all outward appearances, the rutages embodied the pinnacle of Antibbellum’s southern prosperity.

The household staff consisted primarily of enslaved domestics who maintained the impeccable appearance of both the home and its inhabitants.

Among them was Mary, a house servant who had been with the family since William’s childhood, Richard, the stable master whose skill with horses was renowned throughout the county.

Hannah, the children’s nurse, and Martha, a young woman who had been purchased from a neighboring plantation two years prior to serve as Sarah’s personal attendant.

But it was Rebecca, who held the most unusual position within the household hierarchy.

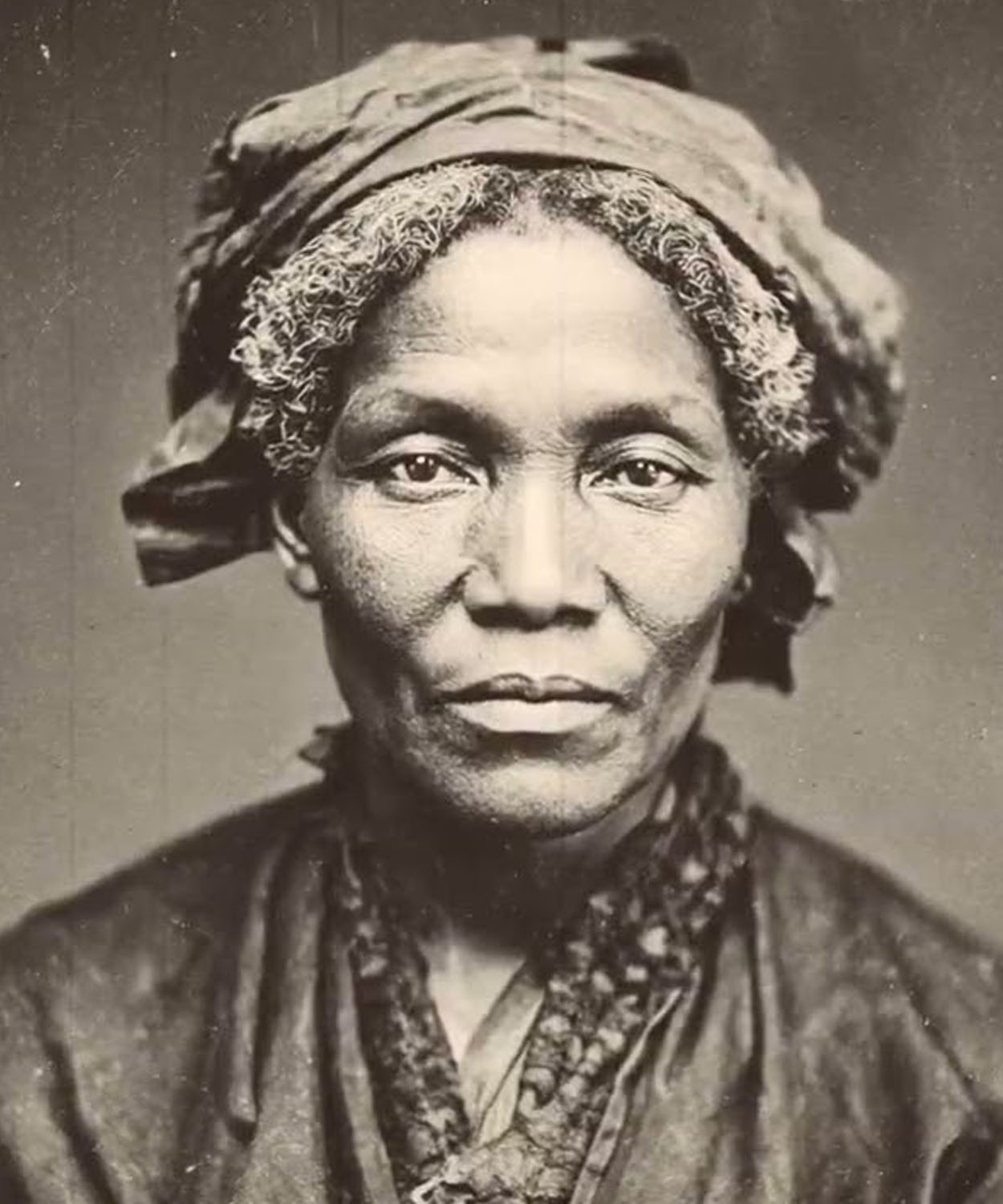

Rebecca, who had been born into slavery on the Rutled plantation approximately 40 years earlier, served as the family’s midwife.

The daughter of an enslaved woman from the Gula region, who had knowledge of herbs and healing, Rebecca had assisted in the births of countless children, both on the plantation and occasionally in the homes of other wealthy families in the area.

Her skills were so valued that William’s father had permitted her to keep a small garden behind the kitchen house where she grew various medicinal plants.

What was not widely known, however, was that Rebecca had also delivered William himself some 35 years earlier, had been present at the birth of each of his siblings, and had brought all three of his own children into the world.

In the society rigidly stratified by race, Rebecca occupied that rare position of being simultaneously essential and invisible.

She moved through the household with quiet efficiency, her presence so familiar that the rutages hardly registered it at all.

The events that would ultimately shatter this household began innocuously enough in March of 1844, approximately 2 months after the birth of James, the Rutled’s youngest child.

Sarah began to complain of fatigue, headaches, and occasional stomach discomfort.

Initially dismissed as the natural consequences of childbirth, her symptoms gradually worsened as spring progressed.

By early May, she had developed a peculiar pala and had lost a noticeable amount of weight.

Doctor Edward Thompson, the family physician who had attended the rutages for years, prescribed a tonic of iron and quinine, suspecting a case of malaria, which was not uncommon in the low-lying areas surrounding Charleston.

The tonic provided no relief.

If anything, Sarah’s condition deteriorated more rapidly after she began taking it.

Her once robust appetite diminished until she could barely manage a few spoonfuls of broth at each meal.

Her strength ebbed so dramatically that by June she could no longer leave her bed chamber without assistance.

The vibrant young woman who had previously managed the household with precision and grace became a ghost of herself.

Confined to a sick bed with the curtains drawn against the harsh summer light.

Dr.Thompson visited with increasing frequency.

As the weeks passed, he applied leeches to draw out what he believed might be bad blood causing her illness.

He administered various preparations of mercury, arsenic, and bismouth, standard treatments of the era.

Nothing alleviated Sarah’s suffering.

In fact, each new treatment seemed to accelerate her decline.

By early July, the entire household revolved around the sick room, with servants constantly rushing in and out with fresh linens, water, and whatever small amount of nourishment Sarah could tolerate.

Throughout this ordeal, Rebecca remained in the background, occasionally preparing herbal teas that were said to settle the stomach or reduce fever.

She moved silently through the house, observing everything while appearing to observe nothing at all.

If anyone had been paying closer attention, they might have noticed that Rebecca always seemed to be present when Dr.

Thompson discussed Sarah’s condition with William, or when the kitchen staff prepared the invalids meals.

But in a household accustomed to treating enslaved individuals as furniture, present but unseen, no one remarked on Rebecca’s quiet vigilance.

On the morning of July 23rd, 1844, Sarah Elizabeth Rutled died in her bed at the age of 29.

The official cause of death was recorded as wasting illness of unknown origin.

A frustratingly vague diagnosis that provided little closure for her grieving husband and motherless children.

The funeral held 2 days later at St.

Michael’s Episcopal Church in Charleston was attended by nearly every prominent family in the city.

Sarah was interred in the Rutled family plot at Magnolia Cemetery.

Her grave marked by an angel in white marble imported from Italy.

Life in the Rutled household attempted to return to some semblance of normaly following the funeral.

William threw himself into his legal practice with renewed vigor, often not returning home until well after the children had been put to bed.

Thomas and Catherine were primarily cared for by Hannah, their nurse, while baby James became the responsibility of Martha, who had previously served as Sarah’s personal attendant.

The house settled into the peculiar quiet that follows in the wake of tragedy.

A silence that seems to have weight and substance.

It was approximately 3 weeks after Sarah’s funeral that William himself began to exhibit symptoms similar to those that had afflicted his wife.

The headaches came first, followed by bouts of nausea and gradually increasing weakness.

Initially, he attributed these symptoms to grief and overwork.

But as August progressed and his condition worsened, Dr.

Thompson was once again summoned to the Rutled estate.

The doctor’s concern was evident from the moment he examined William.

The similarity to Sarah’s illness was too striking to ignore.

Once again, various treatments were prescribed.

Tonics, purgatives, bloodletting, and once again, they provided no relief.

By early September, William was confined to the same bed in which his wife had died just weeks earlier.

His skin had taken on a yellowish tinge, and he suffered from violent stomach cramps that left him drenched in sweat and barely conscious.

Throughout the household, whispers of a possible contagion began to circulate.

Dr.Thompson, however, remained skeptical of this explanation.

Contagious illnesses typically spread more rapidly and widely throughout a household.

Yet none of the children nor any of the house servants had exhibited similar symptoms.

Something else was at work here, something more targeted and insidious.

It was Martha, the young woman who had previously attended Sarah, who first voiced the suspicion that would eventually unravel everything.

One evening in midepptember, as William’s condition continued to deteriorate, she approached Richard, the stablemaster, with a troubling observation.

I’ve seen Rebecca adding something to the master’s tea, she whispered, glancing nervously over her shoulder to ensure they were not overheard.

A powder that she keeps in a small cloth pouch tied at her waist.

She does it when she thinks no one is watching.

Richard initially dismissed Martha’s concerns.

Rebecca had been with the Rutled family for decades.

Her loyalty was beyond question.

Besides, she was a healer, not a poisoner.

It was natural that she would prepare medicinal teas for an ailing member of the household, but Martha was insistent.

It’s the same tea she used to make for Mistress Sarah, she continued.

And I’ve seen her collecting leaves and roots from places beyond her garden, plants I’ve never seen her grow before.

Reluctantly, Richard agreed to watch Rebecca more closely, though he did so mainly to appease Martha rather than out of any genuine suspicion.

3 days of observation, however, confirmed Martha’s account.

Rebecca was indeed adding an unknown substance to William’s tea, a grayish powder that she carefully measured from a pouch kept hidden beneath her apron.

Unsure of how to proceed, Richard finally approached Mary, the eldest of the house servants, and the one person whose judgment he trusted implicitly.

Mary listened to his account without interruption, her expression betraying nothing.

When he had finished, she remained silent for several long moments before responding.

“There are things about Rebecca that you don’t know,” she said finally, her voice barely above a whisper.

“Things that happened before you came to this plantation.

What Mary revealed that night would later be recorded in a deposition given to Charleston authorities, though the document itself would be sealed by court order until 1869.

According to Mary’s account, Rebecca had given birth to a daughter some 20 years earlier.

The child’s father was William Harrison Rutled Senior, the current master’s father.

The infant girl, born with fair skin and green eyes that undeniably marked her parentage, had been sold to a plantation in Georgia when she was just 3 years old, despite Rebecca’s desperate pleas to keep her child.

Rebecca was never the same after that, Mary explained.

She continued her duties as midwife.

She delivered the current master himself and all his brothers and sisters.

She smiled and served and kept her head down.

But something in her eyes changed.

Something died.

The reason for Rebecca’s apparent targeting of Sarah, however, remained unclear until Mary revealed the final piece of the puzzle.

Shortly after William and Sarah’s marriage in 1835, a letter had arrived from Georgia addressed to William Harrison Rutled, Senior.

The letter, which Mary had glimpsed while dusting the Elder Rutled’s study, contained news that Rebecca’s daughter had died under circumstances described as suspicious.

The girl, by then a young woman of 16, had been working as a house servant in the home of a wealthy family related to the Bakers, Sarah’s family.

I believe Rebecca has been waiting all these years, Mary concluded.

waiting until the perfect moment to exact her revenge on both families.

The rutages who took her child and the bakers who she blamed for her daughter’s death.

And what more perfect revenge than to destroy their bloodlines just as they had destroyed hers.

Richard and Mary’s suspicions were confirmed the following day when they secretly observed Rebecca adding the mysterious powder not only to William’s tea, but also to the milk prepared for baby James.

Alarmed, they intercepted the contaminated beverages and replaced them with unaltered versions.

That night, they searched Rebecca’s quarters while she was assisting Dr.

Thompson with William’s treatment.

Hidden beneath the floorboards of Rebecca’s small cabin, they discovered a collection of small cloth pouches containing various powders and dried plant materials.

They also found a journal written in a mixture of English and gull detailing the progressive symptoms of arsenic poisoning and recording with clinical precision the declining health of both Sarah and William.

Most damning of all, they discovered a lock of light brown hair tied with blue ribbon, hair that could only have belonged to Rebecca’s lost daughter.

The evidence was taken directly to Dr.Thompson, who examined the powders and confirmed the presence of arsenic as well as several other toxic substances derived from plants not native to the Charleston area.

Armed with this evidence, authorities were summoned to the Rutled plantation on the morning of September 20th, 1844.

Rebecca was arrested without resistance, her expression betraying neither surprise nor remorse.

The trial that followed became one of the most sensational legal proceedings in Antibbellum, Charleston.

Held in October of 1844, it drew spectators from throughout the region.

Rebecca, denied legal representation, as was typical for enslaved individuals accused of crimes against white citizens, stood silently as witnesses recounted the evidence against her.

Dr.Thompson testified that William Rutled was slowly recovering once the source of his poisoning had been removed.

Martha and Richard described their observations of Rebecca’s suspicious behavior.

Mary revealed the painful history that had presumably motivated Rebecca’s actions.

When asked if she wished to speak in her own defense, Rebecca broke her silence for the first and only time during the proceedings.

Her words recorded by the court cler and preserved in the trial transcript were as follows.

I brought them into this world.

It was fitting that I should usher them out.

What was taken from me cannot be restored.

What I have taken cannot be undone.

There is a balance in all things.

The jury deliberated for less than an hour before delivering a guilty verdict.

On November 2nd, 1844, Rebecca was executed by hanging in the yard of the Charleston workhouse, the first and only time that a female slave convicted of poisoning was publicly executed in the city.

According to newspaper accounts, she maintained her composure until the very end, meeting her death with the same quiet dignity that had characterized her life.

In the aftermath of the trial, William Harrison Rutled made a remarkable recovery, though he was never restored to his former robust health.

He lived another 11 years, dying of pneumonia in 1855 at the age of 46.

His three children survived to adulthood.

Thomas eventually inherited the plantation but sold it in 1871 to move to Baltimore.

Catherine married a northern businessman and relocated to Philadelphia after the Civil War.

James, the infant who had narrowly escaped poisoning, became a physician, perhaps influenced by his family’s tragic history.

The Rutled plantation itself was eventually divided and sold off in parcels following the economic hardships of the reconstruction era.

The main house survived until 1894 when it was destroyed in a fire of unknown origin.

Archaeological excavations conducted at the site in 1965 uncovered the foundations of the house as well as several smaller structures, including what was believed to be Rebecca’s cabin.

Among the artifacts recovered was a small blue glass bottle containing traces of what later analysis identified as arsenic combined with several plant toxins.

What makes this case particularly haunting is not merely the calculated nature of Rebecca’s revenge, but the systems of power and oppression that created the conditions for such a tragedy.

Rebecca, separated from her child and denied any legal recourse for the injustices inflicted upon her, found her power in the only realm available to her.

The knowledge of herbs and medicines passed down through generations of women.

The Rutled poisoning case faded from public memory as the Civil War and its aftermath transformed the social and economic landscape of the South.

It resurfaced briefly in 1962 when historian Margaret Johnston discovered the sealed court records while researching a book on Antabbellum Charleston.

Her notes deposited in the University of South Carolina archives were subsequently lost during a building renovation in 1968.

The documents themselves were reportedly destroyed in a courthouse fire the following year.

All that remains now are fragments, a few newspaper accounts, entries in church death registers, passing references in personal correspondence from the period, and the oral histories collected by Johnston before her notes were lost.

From these fragments, we have attempted to reconstruct this dark chapter in Charleston’s history.

One that speaks to the complex and often terrible relationships between the enslaved and their enslavers, between those who held power and those who found ways to subvert it.

Today, the land where the Rutled plantation once stood has been reclaimed by forest and underbrush.

No marker indicates the sight of the main house or the small cabin where Rebecca mixed her deadly potions.

The graves of Sarah Elizabeth and William Harrison Rutled can still be found in Magnolia Cemetery, their headstones weathered but legible.

Rebecca’s final resting place, like those of most enslaved individuals, remains unmarked and unknown.

But according to local law, on certain nights when the moon is new and the Spanish moss hangs especially still in the humid air, visitors to the area have reported the scent of herbs on the breeze, rosemary, thyme, and something sharper, more metallic.

Some claim to have heard the soft rustling of leaves being ground to powder, the quiet murmuring of a woman’s voice reciting formulas in a language no longer spoken.

And in the oldest families of Charleston, there persists an unspoken fear of certain teas, certain preparations, certain combinations of herbs that might in the wrong hands become instruments of a justice too long denied.

In the years following Rebecca’s execution, several other cases of suspected poisoning by enslaved individuals were reported throughout the Carolas, though none were prosecuted as vigorously or documented as thoroughly as the Rutled case.

Perhaps most telling is an amendment to South Carolina law passed in 1846, specifically prohibiting enslaved people from growing or possessing certain plants known to have medicinal or toxic properties.

The story of Rebecca and the Rutled family serves as a chilling reminder that vengeance when denied all other channels may flow through the most intimate acts of daily life.

The preparation of food and drink, the tending of the sick, the bringing forth of new life.

It reminds us that power, no matter how absolute it may appear, is never complete, and that those deemed powerless, often find and forge their own terrible weapons.

As for Martha, the woman whose observations led to Rebecca’s arrest, records indicate that she was sold to a plantation in Alabama in 1845.

Her fate after that point unknown.

Richard remained at the Rutled plantation until emancipation, after which he established a small livery stable in Charleston.

Mary lived to see freedom as well, dying in 1872 at the estimated age of 85.

In her final years, she reportedly refused to speak of Rebecca or the events of 1844, turning away whenever the subject was raised.

Perhaps the most haunting aspect of this story is the question it leaves us with.

In a system built on fundamental injustice, where can true justice ever be found? Rebecca’s actions, while horrifying, emerged from a lifetime of suffering that few of us today can fully comprehend.

The legal execution that ended her life represented the enforcement of laws designed to protect the very system that had destroyed her family.

There are no heroes in this story, only victims of varying degrees, caught in the grinding machinery of an institution that corrupted everything it touched.

The poisoned bloodline of the rutages and bakers did not end with Williams recovery.

According to correspondents found in the 1880s, descendants of both families continued to suffer from mysterious ailments, often exhibiting symptoms similar to those experienced by Sarah and William.

Medical knowledge of the time was insufficient to determine whether these later cases represented the ongoing effects of earlier poisoning, a genetic susceptibility to certain diseases, or perhaps the power of suggestion at work in families haunted by their own history.

What we do know is that by 1900, both the Rutled and Baker family lines had dwindled significantly with many branches ending in childlessness or early death.

Whether this represents the final fulfillment of Rebecca’s curse or simply the natural entropy of family lineages over time is impossible to determine.

But in the whispered stories passed down through generations of Charleston’s oldest families, the name Rebecca still carries a weight of dread, a cautionary tale of vengeance that reaches beyond death itself to claim its due.

The land where the Rutled plantation once stood remains strangely resistant to development.

Multiple attempts throughout the 20th century to build on the property were abandoned after encountering unexplained difficulties, equipment failures, worker illnesses, financial setbacks.

Local superstition holds that the ground itself has been tainted, poisoned not by arsenic or herbs, but by the weight of history and unresolved injustice.

In 1969, during the last archaeological survey of the site before it was reclaimed by wilderness, researchers discovered something unexpected beneath the remains of Rebecca’s cabin.

a small bundle wrapped in faded blue cloth and containing the skeletal remains of an infant.

Forensic analysis suggested the child had died at or shortly after birth.

No record exists of Rebecca having a second child, and the age of the remains indicated burial sometime around 1824 or 1825, years before the events that would later unfold.

Was this another loss that fueled Rebecca’s decades long quest for vengeance? Another child taken from her, this time by natural causes rather than human cruelty.

The records are silent on this point, and the remains themselves were reinterred without ceremony at the insistence of local community leaders.

And so the story of the enslaved midwife who poisoned her mistress’s bloodline enters the realm of history and folklore, a dark thread in the complex tapestry of America’s past.

It reminds us that beneath the romantic vision of the antibbellum south portrayed in books and films lies a reality far more complex and disturbing.

A reality in which power and resistance, love and hate, life and death, were intimately intertwined in ways that continue to haunt us to this day.

If you find yourself in Charleston, walking the historic streets or visiting the old cemeteries where generations of the city’s elite lie buried in ornate tombs, listen carefully to the stories told by tour guides and local historians.

You may hear sanitized versions of Rebecca’s story, often presented as a cautionary tale about the dangers faced by the plantation aristocracy.

What you are less likely to hear is the fuller truth that Rebecca’s actions, however terrible, represented one woman’s desperate attempt to balance scales that the society of her time had deliberately weighted against her.

In the end, perhaps the most fitting memorial to Rebecca and her victims is not a monument or a marker, but the uneasy silence that still surrounds certain aspects of our shared past.

A silence that when broken reveals stories we are still struggling to fully hear and understand.

Like poison working its way through a bloodline, the effects of our history continue to manifest in ways both visible and invisible, challenging us to confront the complex legacy of those who came before us and the systems they created and resisted.

As the sun sets over the marshes and rivers surrounding Charleston, as the ancient oak trees cast their lengthening shadows across landscapes, both changed and unchanged by time, the story of Rebecca and the Rutligges, whispers to a still, a reminder that beneath the surface of even the most ordered society lie currents of rage and resistance, love and loss that may emerge when we least expect them, altering forever.

ever the course of individual lives and collective histories.

The final records concerning the Rutled case were reportedly sealed in the state archives in Colombia, South Carolina in 1971, deemed too sensitive or potentially inflammatory for public access.

Whether they still exist or have been lost to time like so many other documents from this period remains unknown.

But in the absence of official histories, the story continues to be passed down through generations, changing subtly with each telling yet retaining its essential truth.

That in a world where justice is denied, vengeance may become a terrible substitute, exacting costs that echo across decades and centuries.

And so we leave Rebecca and the Rutligges to their uneasy rest.

Their story neither fully told nor completely forgotten.

A shadow narrative that runs beneath the more comfortable histories we prefer to recall, reminding us of debts unpaid and accounts still being balanced in the ledger books of time.

In 2004, during renovations to an old building in downtown Charleston that had once housed the offices of the law firm where William Harrison Rutled had worked, construction workers discovered a hidden compartment within a wall.

Inside was a small wooden box containing what appeared to be personal effects.

A tarnished silver locket, a folded piece of yellowed paper, and a small vial of dark liquid.

The building’s owner, recognizing the potential historical significance of the find, donated the items to the Charleston Museum.

Analysis of the contents revealed something extraordinary.

The locket contained a lock of hair.

Two strands intertwined, one dark, one light brown.

DNA testing, though limited due to the age of the samples, suggested a close familial relationship.

The folded paper, carefully preserved, was a bill of sale for a molatto female child, aged 3 years, sound in body and mind.

The child’s name was listed as Sarah.

The buyer was a representative of the Baker family of Georgia, relatives of the woman who would later become Sarah Elizabeth Rutled.

The seller was identified as William Harrison Rutled, Senior.

The vial, when analyzed by forensic chemists, was found to contain traces of what appeared to be a complex mixture of arsenic, belladona, and several plant compounds known to cause symptoms similar to those experienced by Sarah Elizabeth and William Rutled in 1844.

Residue analysis suggested the mixture was at least 150 years old.

These discoveries prompted a renewed interest in the rutage poisoning case among historians and archaeologists.

In 2007, a team from the University of South Carolina obtained permission to conduct ground penetrating radar studies of the former Rutled plantation site.

What they discovered beneath the overgrown vegetation were not only the foundations of the main house and outuildings already documented in earlier excavations, but also evidence of a previously unknown structure located approximately 50 yards from Rebecca’s cabin.

Careful excavation revealed the remains of what appeared to be a small dwelling, more rudimentary than the other slave quarters on the property.

Carbon dating of artifacts found at the site suggested it had been occupied sometime between 1820 and 1825, the period when, according to the fragmentaryary historical record, Rebecca would have been pregnant with and given birth to her daughter.

Most significant among the findings was a small clay pot buried beneath the packed earth floor.

Inside the pot were several items.

A child’s tooth wrapped in cloth.

Three glass beads of European manufacturer and a small wooden doll with features carved in a style consistent with West African traditions.

Anthropologists familiar with Gulagichi cultural practices identified these items as consistent with protective charms often created for children.

These discoveries provided a more nuanced understanding of Rebecca’s life before the events that would lead to her execution.

They suggested that she had indeed given birth to a child fathered by William Harrison Rutled Senior, that she had attempted to protect this child through both practical and spiritual means, and that despite these efforts, the child had been sold to relatives of the Baker family at the age of three.

Further research in previously unexplored archives brought to light a series of letters exchanged between members of the Baker family in Georgia and their relatives in Charleston during the years 1840 to 1843.

These letters, part of a private collection donated to the Georgia Historical Society, contained references to a troublesome mulatto servant girl who had been punished repeatedly for insubordination.

One letter dated November 1842 mentioned that the girl had been put in her place after attempting to run away, and that measures had been taken to ensure she would cause no further difficulty.

The final letter in the series, dated January 1843, noted simply that the problem had been permanently resolved and that the writer was seeking a replacement house servant.

No further mention of the girl appeared in subsequent correspondence.

This timing aligns precisely with Mary’s testimony that news of Rebecca’s daughter’s death under suspicious circumstances had reached Charleston shortly before William and Sarah’s wedding in 1835.

These discoveries paint a more complete picture of the events that may have motivated Rebecca’s actions.

Her daughter, taken from her at a young age and sold to relatives of the woman who would later marry into the Rutled family, had apparently died under circumstances that suggested mistreatment or violence.

Rebecca, powerless to protect her child or seek justice through any official channels, had waited patiently for years, cultivating her knowledge of herbs and poisons, positioning herself as the trusted midwife who would deliver the children of the very families responsible for her loss.

The calculated nature of her revenge becomes even more apparent when we consider that she waited until after Sarah had given birth to her third child before beginning the poisoning.

Rebecca ensured that the bloodlines would continue just enough to create the maximum suffering.

Parents would live to see their children grow, form attachments, and then watch them suffer and die.

It was not merely death she sought to inflict, but the same prolonged anguish she herself had endured.

In 2011, an unexpected source provided further insight into the case.

A descendant of Mary, the house servant, whose testimony had been crucial in Rebecca’s conviction, came forward with a family document that had been preserved through generations.

The document written in 1872, shortly before Mary’s death, contained her full account of the events of 1844, including details that had not been part of her official testimony.

According to this account, Mary had been aware of Rebecca’s actions for some time before she revealed them to authorities.

She had observed Rebecca collecting plants from the marshes and forests surrounding the plantation, had noticed the careful way she prepared certain teas and tonics, and had recognized the gradual decline in Sarah’s health as something other than natural illness.

Yet she had remained silent, caught in the impossible position of divided loyalties to the Rutled family who owned her, to Rebecca, who had been her friend and confident for decades, and to her own conscience.

What finally prompted Mary to act, according to her written account, was not concern for William’s life, but fear for the children, particularly the infant James.

I could not stand by and watch a babe suffer for the sins of its father and grandfather.

She wrote, “Rebecca’s vengeance had justice in it, but the children were innocent, and I could not bear their deaths on my conscience.

” Mary’s account also revealed that Rebecca had confided in her about the full extent of her plan, not merely to kill Sarah and William, but to systematically poison every member of both the Rutled and Baker families within her reach.

She had apparently maintained correspondence with other enslaved people in households connected to both families, and had shared her knowledge of poisons with them.

Her plan was to erase both bloodlines from the earth.

Mary wrote as they had tried to erase her daughter.

Whether Rebecca succeeded in this broader aim is difficult to determine.

Historical records do show that in the decades following her execution, both the Rutled and Baker families experienced unusual rates of unexplained illnesses, infertility, and early deaths.

By 1900, as previously noted, both family lines had diminished significantly.

Was this the result of Rebecca’s poisoning reaching across generations, or simply the consequence of the Civil War, economic changes, and the natural dispersal of family lines over time? The historical record cannot provide a definitive answer.

What is clear, however, is that Rebecca’s story represents far more than a simple case of murder or revenge.

It embodies the complex moral universe of American slavery, where conventional notions of justice, loyalty, and morality were distorted beyond recognition.

In a system where human beings were legally property, where families could be separated on a slaveholder’s whim, where sexual exploitation was routine and unquestioned, conventional moral frameworks simply could not contain the depths of human experience and response.

In 2015, the Charleston City Council debated a proposal to include Rebecca’s story in the official historical tours of the city.

After heated discussion, the proposal was rejected on the grounds that it might cast the city’s history in an unnecessarily negative light and focus on divisions rather than reconciliation.

This decision itself becomes part of the ongoing narrative, the ways in which certain histories continue to be marginalized or silenced in service of more comfortable narratives.

Yet, despite official reluctance, Rebecca’s story has continued to circulate through other channels.

Local tour guides who specialize in the darker aspects of Charleston’s history include versions of it in their nighttime tours.

Community theater groups have staged dramatic interpretations.

Writers and artists have found inspiration in this tale of power, resistance, and revenge.

The story refuses to disappear, perhaps because it speaks to something essential about America’s troubled relationship with its own past.

In 2019, during an unusually severe hurricane that struck the South Carolina coast, flooding revealed something long buried on the former Rutled Plantation property.

As waters receded, local residents noticed unusual formations in the soil of an area that had been underwater for generations.

the outlines of what appeared to be a garden perfectly preserved beneath layers of sediment.

Botanical archaeologists from Clemson University excavated the site and identified the remnants of numerous medicinal and poisonous plants, many of which were not native to the region, but would have been known to someone with knowledge of African herbal traditions.

The garden’s location corresponded exactly with historical descriptions of Rebecca’s medicinal garden, the one permitted by William’s father decades earlier.

Analysis of soil samples indicated the continuous cultivation of certain toxic plants for at least 20 years prior to 1844, suggesting that Rebecca’s plan had been in development far longer than anyone had suspected.

Perhaps most chilling was the discovery of a small stone marker buried at the center of the garden.

Carved into its surface was a simple symbol, a circle with a line drawn through it, identified by cultural anthropologists as a symbol associated with certain West African traditions related to justice and the balancing of debts.

The stone was determined to have been placed there sometime around 1825, the year Rebecca’s daughter was sold away from the plantation.

These discoveries suggest that Rebecca’s vengeance was not a sudden decision born of passion or desperation, but rather a carefully orchestrated plan developed and refined over decades.

She had cultivated both her plants and her patience, waiting for the perfect moment to exact a revenge that would mirror the suffering she had endured.

The slow, agonizing loss of family, the helplessness of watching loved ones suffer without the power to intervene.

Medical researchers reviewing the case in light of modern understanding of toxicology have noted that the combination of substances Rebecca apparently used, arsenic, belladona, and certain plant toxins would have created symptoms that mimicked natural illnesses common in the region.

The gradual administration of these poisons would have resulted in accumulation in the victim’s bodies, leading to increasingly severe symptoms that would confound physicians of the era.

The precision with which these poisons were administered suggests not just knowledge of their effects, but careful calculation of dosages.

Knowledge that Rebecca may have refined through observation and experimentation over many years.

The question that haunts this narrative and that continues to resonate with contemporary audiences is not whether Rebecca’s actions were right or wrong by conventional moral standards.

Few would argue that the poisoning of others, including those who had not directly harmed her, could be justified.

Rather, the question is what justice could possibly mean in a context where all conventional avenues for redress were systematically denied.

in a legal system designed to protect the property rights of slaveholders above all else.

In a society that refused to recognize the humanity of enslaved people, in a world where a mother could have her child taken from her and sold like livestock, what form could justice possibly take? Rebecca’s terrible answer to that question continues to disturb us precisely because it forces us to confront the moral bankruptcy of the system that produced it.

In 2022, a descendant of the Rutled family, now living in Massachusetts, came forward with additional family documents that had been preserved through generations.

Among these was a journal kept by Catherine Rutled, the middle child, who had been 6 years old at the time of her mother’s death.

The journal begun when Katherine was a young woman and continued throughout her life contained reflections on her childhood memories and the stories she had later been told about the events of 1844.

Catherine’s account adds yet another layer to this complex narrative.

She recalled Rebecca as a constant reassuring presence in her early childhood.

the woman who had delivered her, who had tended her through childhood illnesses, who had taught her about the plants in the garden.

She described feelings of confusion and betrayal upon learning that this same woman had poisoned her mother and attempted to kill her father and infant brother.

Yet, as Catherine matured and learned more about the full context of these events, her perspective evolved.

Later entries in the journal reveal that she had discovered the truth about Rebecca’s daughter and the role her own maternal relatives had played in the girl’s death.

She wrote of struggling to reconcile her grief for her mother with her growing understanding of Rebecca’s loss and rage.

In one particularly poignant entry dated 1871, Katherine wrote, “I find myself in the impossible position of mourning both my mother and the woman who took her from me.

For I cannot help but wonder had our positions been reversed, what I might have done had my own child been torn from my arms and later destroyed by the very people who claimed the right to own her.

” There is no resolution to this terrible equation, no balancing of these scales.

Catherine’s journal reveals that her decision to move north after the Civil War was motivated in part by her desire to distance herself from the legacy of slavery and the moral complexities it had created.

She never had children of her own, a choice she explicitly connected to her fear that the poison in our bloodlines runs deeper than any substance Rebecca might have administered.

It is the poison of a system that corrupted everything it touched.

Thomas Rutled, the eldest child, took a different path.

After selling the plantation in 1871, he maintained correspondence with several former slaves who had worked on the property, including Richard, the stablemaster.

In letters preserved in the Maryland Historical Society archives, Thomas expressed his belief that his father had known about Rebecca’s daughter all along, and had chosen to remain silent about his own father’s actions.

“There was a reckoning that was perhaps long overdue,” he wrote in one letter.

though I cannot help but wish it had taken some other form.

James Rutled, the infant who had nearly become Rebecca’s third victim, did indeed become a physician, as previously noted.

His medical journals, discovered in 2008 in the archives of John’s Hopkins University, where he later worked, reveal a preoccupation with poisons and their antidotes.

He specialized in toxicology, publishing several papers on the detection and treatment of arsenic poisoning.

Whether this career choice represented an attempt to understand the events that had nearly claimed his life or simply a coincidence is impossible to determine.

The story of Rebecca and the rutages has no neat conclusion, no moral that can be easily extracted and applied.

It remains, like so much of American history, a narrative of complexity and contradiction, of individual choices made within systems that constrained and distorted those choices.

It reminds us that the legacy of slavery cannot be reduced to simple narratives of good and evil, but must be understood as a moral catastrophe that corrupted everything within its reach.

those who perpetuated it, those who benefited from it, and those who resisted it.

In the marshlands surrounding Charleston, where the ruins of plantation slowly sink into the earth, and the ghosts of the past seem to hover just beyond the edge of vision, Rebecca’s story continues to resonate.

Local folklore maintains that on certain nights, particularly when the moon is dark and the air heavy with approaching rain, a woman can be seen moving silently among the trees, gathering plants, and murmuring words in a language few now remember.

Some claim to have smelled the distinctive odor of certain herbs boiling even in areas where no human habitation exists for miles.

These are just stories, of course, the ways in which communities process and transmit difficult histories, the means by which the past maintains its hold on the present.

But they speak to the power of Rebecca’s narrative and its continued relevance to contemporary concerns about justice, power, and the long shadow cast by America’s founding sin.

The most recent chapter in this ongoing story occurred in 2023 when archaeological work at the site of the former Charleston workhouse, the location of Rebecca’s execution, uncovered a mass grave containing the remains of numerous individuals who had died while imprisoned there or who had been executed on the grounds.

Forensic analysis identified the partial remains of a woman approximately 50 to 60 years of age with evidence of arthritis in the hands consistent with years of detailed work such as midwiffery and herbalism.

Though positive identification was impossible given the condition of the remains and the passage of time, the location and characteristics aligned with what is known about Rebecca.

After consultation with community leaders and historians, these remains along with all others recovered from the site were reinterred in a formal ceremony that acknowledged the complex history of the location and the lives that had ended there.

The memorial service attended by descendants of both enslaved people and slaveholders from the region represented a small step toward the kind of reckoning with history that Rebecca’s story demands.

As we conclude this account, we are left with questions rather than answers.

What does justice look like in the wake of historical atrocities? How do we balance the need to understand the full complexity of the past with the desire for narratives that allow for healing and reconciliation? What debts remain unpaid? What accounts remain unbalanced in the ledger books of history? Rebecca’s voice comes down to us only in fragments, filtered through the accounts of those who condemned her and the systems designed to silence her.

Yet the power of her story persists, forcing us to confront uncomfortable truths about American history and identity.

In her final statement before the court, I brought them into this world.

It was fitting that I should usher them out.

What was taken from me cannot be restored.

What I have taken cannot be undone.

There is a balance in all things.

We hear not just the voice of one woman driven to terrible acts by unbearable loss, but an indictment of a society that created the conditions for such tragedy.

The poisoned bloodline that forms the center of this narrative extends beyond the biological descendants of the Rutled and Baker families.

It reaches into our present, into the persistent inequalities and unresolved traumas that continue to shape American society.

Rebecca’s story asks us to consider what poisons might still be working their way through our collective body, what antidotes might yet be discovered, and what true healing might require.

As night falls over Charleston, as the ancient oak trees cast their shadows across landscapes, both changed and unchanged by time, Rebecca’s presence lingers, not as a simple villain or victim, but as a complex human being caught in and responding to inhuman circumstances.

Her story whispers to us still, demanding to be heard in its full complexity, refusing the comfort of easy judgment or convenient forgetting.

In the end, perhaps the most fitting memorial to Rebecca and all those caught in the web of tragedy surrounding her is not a monument or a marker, but the ongoing work of confronting our shared past with courage and honesty.

For only by acknowledging the full weight of history, its complexities, its contradictions, its unresolved debts, can we begin to imagine a future where the poisoned bloodlines of our national origins might finally be healed.

News

Ilhan Omar ‘PLANS TO FLEE’…. as FBI Questions $30 MILLION NET WORTH

So, while Bavino is cracking down in Minnesota, House Republicans turning the heat up on Ilhan Omar. They want to…

FBI & ICE Raid Walz & Mayor’s Properties In Minnesota LINKED To Somali Fentanyl Network

IC and the FBI move on Minnesota, touching the offices of Governor Tim Walls and the state’s biggest mayors as…

FBI RAIDS Massive LA Taxi Empire – You Won’t Believe What They Found Inside!

On a Tuesday morning, the dispatch radios in hundreds of Los Angeles taxi cabs suddenly stopped playing route assignments. Instead,…

Brandon Frugal Finally Revealed What Forced Production to Halt in Season 7 of Skinwalker Ranch….

The Secret of Skinwalker Ranch became History Channel’s biggest hit. Six successful seasons documenting the unknown with real science and…

1 MINUTE AGO: What FBI Found In Hulk Hogan’s Mansion Will Leave You Shocked….

The FBI didn’t plan to walk into a media firestorm, but the moment agents stepped into Hulk Hogan’s Clearwater mansion,…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage… It started like any other evening…

End of content

No more pages to load