I wasn’t looking for giants when I started this investigation.

I was researching architectural anomalies.

Doorways too tall, staircases too grand, furniture scaled beyond human proportion, standard historical curiosities, the kind of thing you file away as decorative excess or ceremonial design and move on.

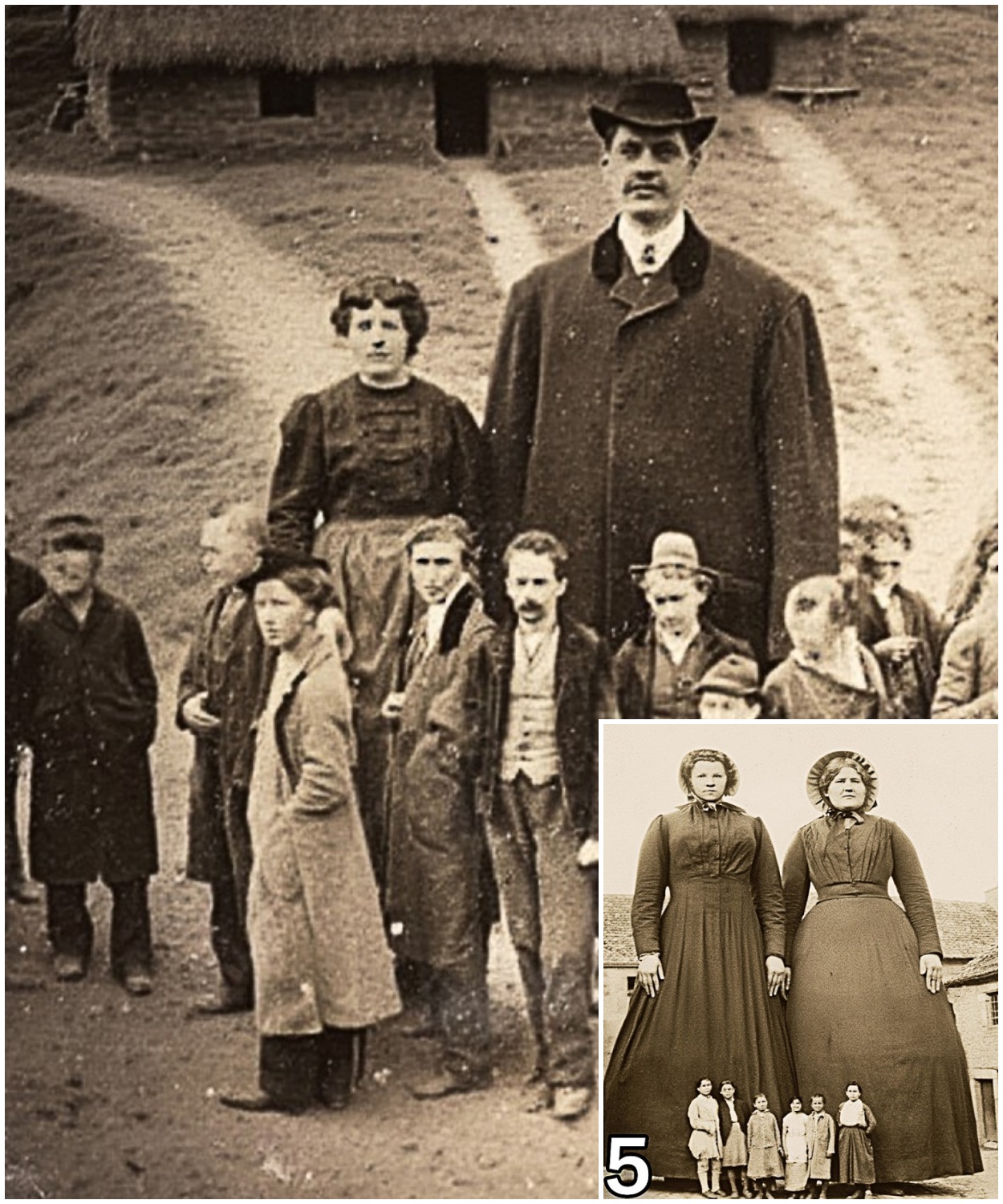

But then I found the photographs, not paintings, not myths, not folklore passed down through generations of embellishment.

photographs.

Actual photographic evidence from the mid to late 1800s showing human beings of impossible scale standing next to regularsized people.

Their proportions so dramatic they seemed like composites except they weren’t composites.

The grain matched, the lighting matched, the shadows fell correctly.

These images predated the technology to fake them convincingly.

And that’s when the official explanations began to collapse.

The deeper I went, the more photographs I uncovered.

Carts devisit from the 1860s.

Cabinet cards from the 1870s.

Tint type images showing men and occasionally women standing 8 n sometimes 10 ft tall.

Not circus performers advertised as such.

Not showmen with documented names and traveling routes.

Just people.

Individuals photographed in formal settings wearing period appropriate clothing, sometimes surrounded by family members of normal height.

The British Museum archives contain several.

The Smithsonian mentions them in passing, then dismisses them as medical anomalies without further investigation.

French collections show similar images cataloged and filed away.

Russian imperial records reference persons of unusual stature serving in ceremonial roles.

always the same pattern.

Acknowledge, categorize, move on.

Never investigate, never ask why.

Why were there so many? Why do the photographs cluster in specific decades, primarily between 1850 and 1900, then suddenly disappear? Why do contemporary accounts describe these individuals not as freaks or oddities but as normal members of society holding positions of authority working as guards, overseers, foremen of construction projects.

And here’s the strangest part.

Many of these photographs show the giants standing in front of buildings.

Massive buildings.

Buildings with doorways that seem absurdly oversized for normal humans, but perfectly proportioned for the individuals pictured.

Buildings, we’ve been told, were designed for grandeur or intimidation.

Buildings that suddenly make sense when you place a 9- ft tall human being in the frame.

Once you see it, you can’t unsee it.

I started measuring doorways in government buildings from the 1700s and 1800s, 12 to 15 ft high.

Not at the entrance, inside in working corridors where grandeur serves no purpose.

Staircases with risers so tall a normal person must stretch to climb them comfortably.

Furniture, desks, chairs, beds found in estate sales and museums, all slightly too large, all dismissed as decorative or custommade for tall individuals.

But it’s not just one building.

It’s thousands.

courouses across America, administrative buildings throughout Europe, government complexes in Russia, India, South America, all built in the same period, all featuring the same oversized proportions.

All supposedly designed this way for aesthetic reasons, despite the obvious impracticality, despite the added cost, despite the fact that it makes no functional sense, unless the people using them weren’t averagesized.

The pattern repeats with unsettling precision.

In St.

Petersburg, administrative buildings from the 1700s have 12t doors in back hallways.

In Buenosarees, municipal structures feature staircases requiring enormous strides.

In Delhi, colonial era government buildings supposedly built by and for British administrators contain furniture at scales that would make a 6-ft man feel like a child.

These weren’t ceremonial spaces.

These were working buildings, offices, administrative centers, the everyday architecture of governance and oversight.

Who were they built for? And that’s where Tartaria becomes impossible to ignore.

If you’re not familiar, Tartaria appears on maps from the 1700s and early 1800s as a vast territory spanning northern Asia.

Not a legend, not a myth, an actual labeled region appearing in encyclopedias, atlases, and historical records with the casual certainty of France or Spain.

Then sometime in the mid 1800s, it vanishes.

Not conquered, not renamed, erased.

The maps are redrawn.

The encyclopedias omitted.

The history books pretend it never existed.

But the architecture remains.

Massive stone structures across Central Asia, Russia, Mongolia, buildings of impossible scale and precision, doorways sized for giants, halls that echo with vastness, all supposedly built by various empires or local craftsmen with no documentation, no verified construction records, no explanation for how they achieved such engineering feats with the technology supposedly available?

What if the giants weren’t anomalies? What if they were the administrators, the overseers, the guardian class of a civilization we’ve been taught to forget?

What if Tartaria, whatever it actually was, employed these individuals not as curiosities, but as functional members of society, and the architecture reflects that reality.

It would explain the photographs why they’re always formal official, showing these individuals in positions of authority, why they disappear after the 1890s, right when the last references to Tartaria vanish from official records, why the buildings remain but the occupants have been written out of history.

This raises a simple but critical question.

If you wanted to erase a civilization from collective memory, wouldn’t you start by erasing the most visible evidence? The individuals whose very existence prove something else was here.

The photographic record isn’t the only evidence.

Throughout the 1800s and early 1900s, newspapers across America regularly reported discoveries of giant human skeletons.

Not scattered anomalies, systematic findings.

The New York Times, 1885.

7-foot skeleton discovered in Michigan Mound.

The San Diego Union, 1895.

Bones of extraordinary size found during railroad excavation.

The Middletown Signal, 1899.

Giant human remains uncovered in Ohio.

These weren’t tabloid sensations.

These were mainstream newspapers reporting what was at the time considered newsworthy but not particularly controversial.

The accounts describe skeletons measuring 7 to 12 ft in length, often found in organized burial sites, frequently accompanied by artifacts suggesting advanced metallergy and construction knowledge.

Then something changed.

After approximately 1920, these reports stop.

Not gradually, abruptly, discoveries that were once front page news simply ceased to appear.

The skeletons already found.

Many were sent to the Smithsonian Institution for further study.

The Smithsonian now claims no such skeletons exist in their collections.

Missing, lost, misplaced during routine transfers.

Hundreds of specimens all vanished without proper documentation.

The pattern is too consistent to ignore.

Discoveries peak in the late 1800s.

The same period the giant photographs appear.

The same period Tartaria disappears from maps.

Then everything stops.

The photographs stop.

The newspaper reports stop.

The maps change.

The encyclopedias rewrite themselves.

As if someone decided certain questions were no longer acceptable to ask.

Why would you bury evidence of human biological diversity? Why would you systematically remove physical proof that challenges the standard narrative of human history? Unless that proof suggested something larger, something organized, something that implied a different structure to recent civilization than we’ve been taught.

Let me propose something that sounds absurd until you examine the evidence.

What if the giants weren’t rulers? What if they were a specialized class? guardians, overseers, administrators of infrastructure and construction.

What if their size was functional, not ceremonial? What if buildings were scaled to them because they were the ones overseeing their construction and maintenance? It would explain the architectural patterns.

Why government buildings, courouses, administrative centers, structures of oversight and control feature oversized proportions while residential areas remain human-scaled? Why the photographs show giants in formal official contexts rather than domestic settings.

Why historical records mention them in roles of supervision and authority, but rarely as merchants, artists, or common laborers? It would explain the construction mystery.

How were massive stone structures built with such precision in the 1700s and 1800s? Maybe they weren’t built by the civilizations we credit them to.

Maybe they were built for those civilizations by a previous society that employed individuals physically capable of moving stones, operating machinery, and overseeing construction at scales we consider impossible.

And it would explain the systematic eraser.

If you’re inheriting structures you didn’t build, inheriting technology you don’t fully understand, inheriting architectural systems designed for a different type of human being, what do you do? You adapt the narrative.

You claim it as your own.

You rewrite the construction dates, backdate the architects, and remove any evidence that suggests someone else was here first.

Ask yourself, how many mysterious construction techniques suddenly make sense if you assume the builders were physically larger and stronger than modern humans? How many impossible engineering feats become merely difficult if the laborers stood 9 ft tall? The evidence suggests something much larger than random genetic anomalies.

What disturbs me most isn’t the evidence itself.

It’s the coordinated silence surrounding it.

Academic institutions don’t debate the giant skeletons.

They pretend they never existed.

Museums don’t display the photographs.

They file them in archives marked miscellaneous or unverified.

Historical societies don’t investigate the architectural proportions.

They dismiss them as artistic choice.

The pattern repeats across disciplines, across countries, across centuries of scholarship.

It’s not active suppression.

It’s passive eraser.

Questions that simply aren’t asked, evidence that isn’t examined, dots that aren’t connected because connecting them leads to conclusions that don’t fit the established narrative.

And when you point it out, when you lay the evidence side by side, the photographs, the architecture, the newspaper reports, the missing records, you’re met with the same response.

Interesting, but not significant.

As if coincidence explains everything.

As if patterns don’t matter.

As if asking why is somehow inappropriate.

But the why is the entire point.

Why did humans of extraordinary size exist in sufficient numbers to be regularly photographed and regularly discovered in burial sites? Why were they documented then forgotten? Why does architecture from a specific period accommodate their proportions? Why do these elements cluster in the same geographical regions and time periods as Tartaria’s disappearance from ctographic record? And why, when you mention any of this in academic circles, does the conversation immediately shut down? I keep returning to the photographs.

These weren’t monsters, weren’t myths.

They were people.

Individuals with faces, clothing, families, people who stood for formal portraits like anyone else in the 1800s.

People whose existence was so unremarkable at the time that photographers saw no need to explain or contextualize their presence.

But we’ve made them remarkable by erasing them.

We’ve made them impossible by denying they were ever possible.

We’ve turned documented reality into forbidden speculation.

And in doing so, we’ve lost something.

Not just knowledge of who they were, but understanding of what we are.

What we’ve forgotten.

What we’ve inherited without comprehension.

The massive doorways remain.

The oversized staircases still stand.

The buildings that make no sense for human proportions continue to serve modern functions.

Their original purpose obscured by centuries of adaptive reuse.

We walk through them daily without asking why.

We accept the official explanations without examining whether they actually explain anything.

Because examining them requires accepting that history isn’t a straight line of progress.

That we might be living in the remnants of something more sophisticated, something we didn’t build, something we don’t fully understand.

that the giants in the photographs weren’t aberrations but evidence of a different arrangement, a different society, a different world.

I stumbled across enormously sized chairs in estate auctions and forgotten museum storage rooms.

Chairs that make no anatomical sense, not thrones, not ceremonial pieces meant to intimidate or impress.

Ordinary chairs, dining chairs, desk chairs, sitting chairs designed for daily use.

Except they’re scaled wrong.

The seat height measures 30 to 36 in from the floor, nearly double the standard 18in height that accommodates normal human leg length.

The back rests tower 7, sometimes 8 ft high.

The armrests sit at a height that would leave an average person’s arms dangling uselessly.

Auction catalogs list them as decorative furniture or display pieces, as if people in the 1800s routinely commission chairs they couldn’t physically use just for aesthetic purposes.

Museum curators label them oversized Victorian design without explaining why such designs appear in government buildings, administrative offices, and courthouse waiting rooms, functional spaces where comfort and usability would presumably matter.

And then there are the instruments themselves, the artifacts no one wants to classify.

I’m talking about the massive wrenches found in demolition sites across Europe and North America.

Tools measuring four, five, sometimes 6 ft in length.

Not decorative, not ceremonial.

Functional tools with wear patterns with the kind of grip erosion that comes from actual use.

Tools designed for hands much larger than ours.

Museums categorize them as industrial equipment without explaining what industrial process would require a wrench weighing 200 pounds that needs to be operated by someone with the grip strength of three normal men.

Auction houses sell them as antique curiosities without asking why they were manufactured in such quantities that they keep appearing in estate sales, barn cleanouts, and building demolitions more than a century later.

And suddenly the oversized tools and furniture aren’t anomalies anymore.

They’re confirmation.

So who were these giant people? Were they the guardians of Tartaria? The administrative class of a civilization we’ve been taught never existed? The overseers of construction projects whose scale and precision we still can’t replicate with modern technology? I don’t have definitive answers, only questions that accumulate, that build upon each other, that create a weight the official narrative can’t support.

Why does the photographic evidence cluster in the exact decades when Tartaria disappears from maps? Why do architectural proportions match the scale of individuals in those photographs? Why do newspaper reports of giant skeleton discoveries stop precisely when references to advanced pre-industrial technology begin to be emitted from historical records? Not coincidence, not random variation, not independent anomalies that happen to align pattern.

And when you see the pattern, when you trace it across continents and centuries, when you watch it appear and disappear with suspicious precision, you have to ask, “What aren’t we being told? What did we inherit that we’ve chosen to forget?

What knowledge was lost or hidden when the maps were redrawn and the giants disappeared from history? The buildings remember, even if we don’t, the photographs preserve what the encyclopedias erased.

The evidence persists, waiting for someone willing to ask the questions everyone else has agreed not to ask.

Who were the giants? Why did they disappear? And what else vanished with them that we’re still pretending was never here at all?

News

Ilhan Omar ‘PLANS TO FLEE’…. as FBI Questions $30 MILLION NET WORTH

So, while Bavino is cracking down in Minnesota, House Republicans turning the heat up on Ilhan Omar. They want to…

FBI & ICE Raid Walz & Mayor’s Properties In Minnesota LINKED To Somali Fentanyl Network

IC and the FBI move on Minnesota, touching the offices of Governor Tim Walls and the state’s biggest mayors as…

FBI RAIDS Massive LA Taxi Empire – You Won’t Believe What They Found Inside!

On a Tuesday morning, the dispatch radios in hundreds of Los Angeles taxi cabs suddenly stopped playing route assignments. Instead,…

Brandon Frugal Finally Revealed What Forced Production to Halt in Season 7 of Skinwalker Ranch….

The Secret of Skinwalker Ranch became History Channel’s biggest hit. Six successful seasons documenting the unknown with real science and…

1 MINUTE AGO: What FBI Found In Hulk Hogan’s Mansion Will Leave You Shocked….

The FBI didn’t plan to walk into a media firestorm, but the moment agents stepped into Hulk Hogan’s Clearwater mansion,…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage… It started like any other evening…

End of content

No more pages to load