On a suffocating August morning in 1858, the housekeepers at Blackwood Manor in Savannah, Georgia, discovered something that would shatter the foundations of one of the South’s most respected families.

In the master bedroom, Colonel Harrison Blackwood lay dead in his silk sheets, his face twisted in an expression of what doctors would later describe as extreme agony mixed with impossible ecstasy.

But what made this death truly scandalous wasn’t how he died.

It was who was found sleeping peacefully in his arms.

A 23-year-old slave named Morgan, whose body possessed characteristics that defied every law of nature and society that the antibbellum South held sacred.

The White Society of Savannah was scandalized, but they had no idea what Colonel Harrison had truly been doing behind closed doors for 8 years, or what Morgan’s body had become capable of in those final months.

What the Blackwood family discovered about their patriarch’s obsession would expose secrets so disturbing that three different judges refused to hear the case.

The medical examination of Morgan’s body revealed anatomical impossibilities that physicians couldn’t explain, both male and female organs, fully formed and functional.

And the private journals found hidden in the colonel’s study detailed 8 years of forbidden passion, philosophical meditations on desire, and a pregnancy that shouldn’t have been possible.

By the time authorities finished their investigation, one woman had confessed to attempted murder.

13 men were dead.

Blackwood Manor was nothing but ash.

And Morgan had vanished into the night carrying a child whose very existence challenged everything 1850s America believed about the human body.

Charleston’s slave market in September of 1850 operated with the efficiency of any other commodity exchange, but the air itself seemed thick with sin and suffering.

The auction house on Charma’s Street, a two-story brick building with barred windows that cast prison-like shadows across the cobblestone street, processed hundreds of human beings each month.

The stench of unwashed bodies mixed with the sweet perfume of magnolia blossoms drifting in from nearby gardens, creating a nauseating contrast that perfectly captured the hypocrisy of the antibbellum south.

Inside the September heat was suffocating, trapped between brick walls and low ceilings, making the air feel solid enough to chew.

Wealthy planters from across the South gathered there in their finest clothes, linen suits already dark with sweat stains despite the early hour to inspect merchandise, evaluate physical capabilities, and make purchases that would increase their agricultural output and social standing.

The sound of the auctioneers’s voice echoed off the walls, mixing with the rattle of chains and the whispered prayers of people about to be sold.

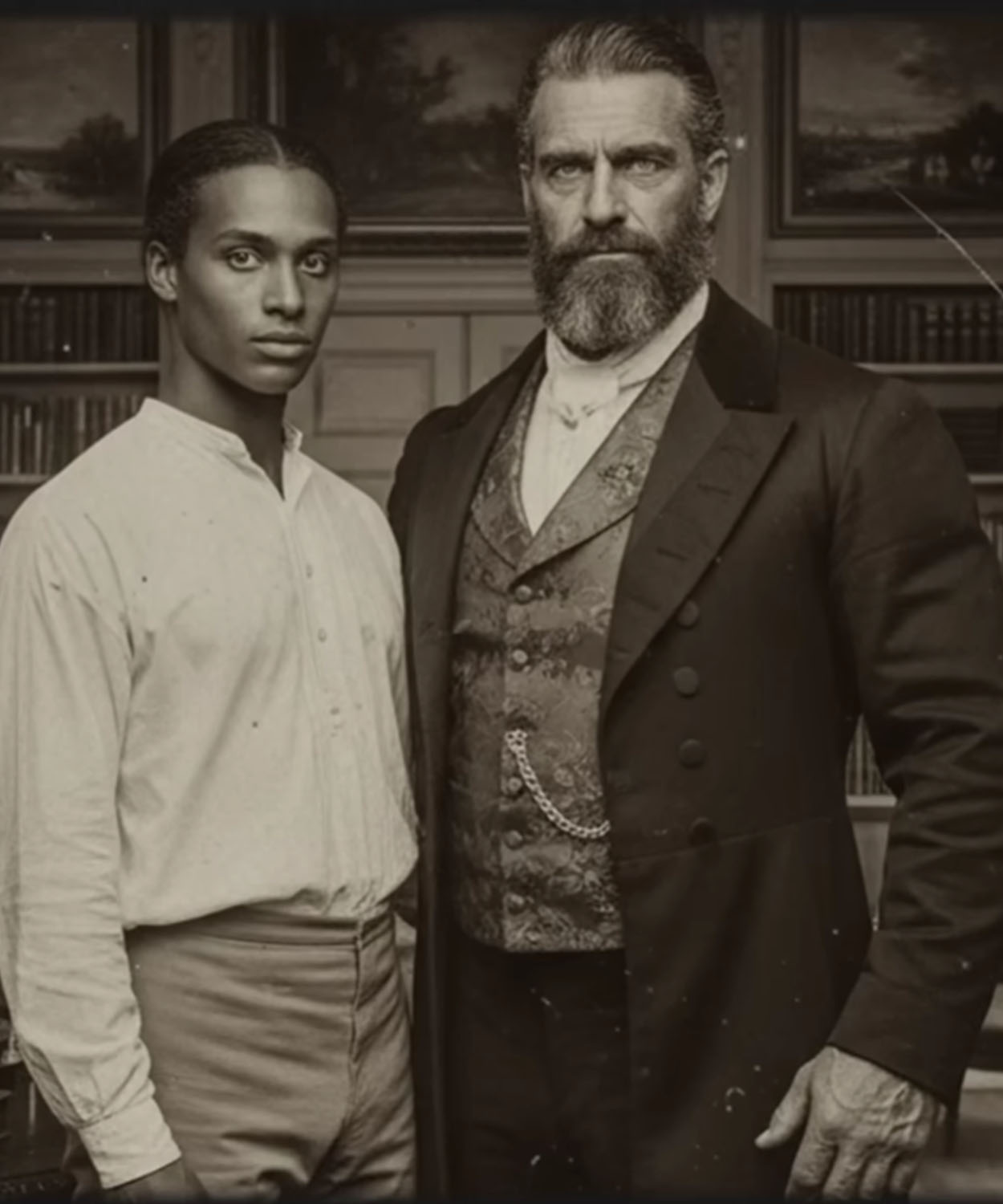

Colonel Harrison Blackwood, at 42 years old, stood near the back of the auction room, fanning himself with his hat and trying to ignore the oppressive heat that made his starched collar feel like a noose.

He represented everything the southern aristocracy aspired to embody.

His 3,000 acre cotton plantation generated over $50,000 annually, equivalent to several million dollars today.

His wife, Constance Fairfax Blackwood, came from one of Virginia’s oldest families, bringing with her both impeccable bloodlines and a dowy that had expanded the Blackwood holdings significantly.

Their marriage, arranged by their families when Constance was just 17, had produced two daughters, but little affection between the couple, and even less physical passion.

Harrison attended the Charleston auction that September afternoon, searching for field hands to replace workers who had been sold to settle a gambling debt.

He had no intention of purchasing anything unusual, no interest in the human drama unfolding on the auction block before him.

But when the auctioneer brought out lot number 47, everything changed in a heartbeat that Harrison would later describe in his journals as the moment my real life began.

The slave was listed simply as Morgan, approximately 15 years, origin unknown, unique physical characteristics noted in private documentation available to serious buyers.

The youth stood on the auction block wearing a simple cotton shift that revealed a slender build, smooth skin, the color of caramel, and features that seemed to shift between masculine and feminine depending on the angle of observation.

Lot 47 comes with full disclosure documentation, the auctioneer announced, his voice carrying across the crowd.

Buyer assumes all associated complications.

Starting bid, $200.

The room fell silent.

Several potential buyers who had been examining Morgan moments before suddenly lost interest and moved toward the exit.

Harrison noticed their reaction and felt his curiosity ignite.

“What complications could make experienced slave traders flee from a purchase?” “$200,” Harrison called out, his voice steady despite the questions racing through his mind.

No other bids came.

The auctioneer, clearly eager to complete this particular sale, brought his gavel down with unnecessary force.

sold to Colonel Blackwood of Savannah.

Please see the clerk for documentation.

In the auction house office, the clerk handed Harrison a sealed envelope along with Morgan’s bill of sale.

Colonel, you’ll want to read this before you leave.

Company policy is to provide full disclosure on, shall we say, anatomically irregular merchandise.

Harrison broke the seal and began reading the medical documentation inside.

What he read made his hands tremble, though whether from shock or something else, he couldn’t immediately say.

The slave Morgan possessed both male and female sexual organs, fully formed, and according to the examining physician, both apparently functional.

The condition was described in clinical terms, but the implications were anything but clinical.

The documentation noted that Morgan had been born on a Louisiana plantation, sold three times in the past 8 years due to what previous owners had described as discomfort with the slaves presence and concerns about moral corruption of other slaves.

Each owner had sold Morgan quickly, usually at a loss, apparently disturbed by questions they couldn’t answer about how to categorize and utilize this particular piece of property.

Harrison looked through the office window at Morgan, who stood waiting in the holding area, eyes downcast in the practiced submission of the enslaved.

In that moment, Harrison Blackwood made a decision that would ultimately destroy his family, his reputation, and his life.

But it would also give him 8 years of something he had never experienced in his carefully constructed aristocratic existence, genuine passion.

What Harrison didn’t know as he signed the bill of sale and prepared to take Morgan back to Savannah was that someone else had been watching the auction that day.

Someone who would later claim that they saw something in Morgan’s eyes that suggested this slave understood exactly what kind of man had just purchased them.

Someone who would spend the next 8 years observing everything that happened at Blackwood Manor, documenting it all, and eventually using that information in ways that would shock even the hardened investigators who thought they’d seen everything.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

First, you need to understand how a respected plantation owner and a hermaphrodite slave became something more than master and property, and how their impossible relationship would eventually lead to pregnancy, murder, and secrets that Savannah Society would pay any price to keep buried.

The journey from Charleston to Blackwood Manor took 3 days by carriage.

Harrison rode inside with Morgan, ostensibly to prevent the slave from attempting escape, but truly because he found himself unable to stop asking questions.

Morgan spoke softly with an educated vocabulary that suggested previous owners had provided some learning despite laws prohibiting slave education.

“How do you think of yourself?” Harrison finally asked on the second evening the question that had been burning in his mind since reading the medical documentation.

as male or female.

Morgan looked directly at him for the first time, violating the unwritten rule that slaves should never meet a white person’s gaze.

I think of myself as Morgan, sir.

The world demands I be one or the other, but God made me both.

I’ve learned that my existence makes people uncomfortable because I don’t fit into the categories they need to make sense of their world.

The insight stunned Harrison.

He had expected simple answers from an enslaved youth, not philosophical observations that cut to the heart of social construction and human identity.

In that moment, his interest in Morgan transformed from curious fascination to something far more dangerous, intellectual attraction.

“Can you read?” Harrison asked.

“Yes, sir.

My first owner’s wife taught me before she understood what I was.

After that, they forbid it, but I practiced in secret.

” and right.

Well enough, sir.

Harrison made another decision that would prove fateful.

When we reach Blackwood Manor, I’m going to place you in the house rather than the fields.

You’ll serve as a personal attendant.

There are books in my study.

When your duties are complete, you may read them, but tell no one.

Morgan’s eyes widened with an expression that mixed surprise, gratitude, and something else Harrison couldn’t quite identify.

Why would you do this for me, sir? Because, Harrison said slowly, testing the words as he spoke them, “I suspect you see the world in ways that most people cannot, and I find that I want to understand how you see things.

” It was the most honest sentence Harrison Blackwood had spoken in 20 years of married life.

But even as those words left his mouth, even as he saw hope spark in Morgan’s eyes for the first time since the auction block, dark forces were already moving into position around them.

forces that would test whether love could truly exist between master and slave, whether passion could overcome the brutal mathematics of property ownership, and whether two people who refuse to fit into society’s categories could create something genuine in a world designed to destroy them.

The answer, as we’ll discover, was far more complicated and tragic than either of them could have imagined.

Blackwood Manor rose from the Georgia landscape like something from a Gothic novel.

its white columns gleaming in the brutal afternoon sun like bones bleached by decades of southern heat.

Three stories of Greek revival architecture surrounded by ancient oak trees whose Spanish moss hung in the still air like the hair of hanged women swaying without wind, without reason, as if animated by the ghosts of all the suffering that had occurred on this land.

The house sat at the center of over 200 enslaved souls who worked cotton fields that stretched to the horizon in every direction.

An empire of white bowls and black backs that generated the wealth that kept the columns painted and the windows gleaming.

The humid air clung to everything, making it hard to breathe, hard to think, hard to imagine that life could exist anywhere beyond this oppressive heat and the smell of magnolia blossoms rotting in the sun.

Cicadas screamed in the trees with an urgency that suggested they knew something terrible was coming, something that would make even insects fall silent in horror.

Constance Blackwood waited on the front portico when Harrison’s carriage arrived.

her posture rigid with the controlled fury of a wife who had not been consulted about her husband’s 3-day absence.

At 32 years old, Constance retained the severe beauty of her Virginia upbringing.

Pale skin protected from the sun with religious devotion, dark hair pulled back in a style so tight it seemed to stretch her face into a permanent expression of displeasure, and eyes the color of winter ice that could freeze water in July, and had frozen her husband’s affection long ago.

You left without notice,” she said as Harrison stepped from the carriage, her voice cold and measured, each word precisely enunciated, as if she were giving testimony in court.

“I had to explain to the Merryweathers why you missed their daughter’s engagement dinner.

” “Business in Charleston required immediate attention,” Harrison replied, using the excuse that had served for countless similar absences over the years of their marriage.

an excuse that had become so routine that neither of them bothered to pretend it was true anymore.

What business? Constance’s gaze moved past him to Morgan, who stood waiting beside the carriage, eyes downcast.

And who is this? New house slave, personal attendant.

I have correspondence and accounts that require better management than Jackson provides.

Constance studied Morgan with the practiced eye of a plantation mistress, accustomed to evaluating slave purchases for their potential utility and problems.

Something in Morgan’s appearance made her pause, her eyes narrowing with a suspicion she couldn’t quite articulate.

The slave’s features seemed to shift in the afternoon light, sometimes appearing almost feminine in their delicacy, sometimes suggesting masculine strength.

It was subtle, barely noticeable, but Constance had spent 32 years learning to notice things that other people missed.

“This one seems delicate for heavy work,” she observed, her voice dripping with disdain.

“Might be better suited for the fields where we wouldn’t have to look at it every day.

” “I’ve assigned duties,” Harrison said with unusual firmness.

“Morgan will attend me in the study and manage my personal affairs.

” The emphasis on personal affairs made Constance’s jaw tighten, but she had learned over 14 years of marriage, when to press her husband, and when to retreat.

She turned and walked into the house without another word, her silk skirts rustling with barely contained anger that sounded like dry leaves before a storm.

But Constance Blackwood was not a woman who forgot perceived slights or abandoned suspicions easily.

As she climbed the stairs to her bedroom, she made a mental note to watch this new slave carefully, to observe what made her husband speak with such unusual protectiveness about a piece of property.

She didn’t know yet what she was looking for, but she would know it when she saw it.

And when she did, God help everyone involved.

Business in Charleston required immediate attention, Harrison replied, using the excuse that had served for countless similar absences over the years of their marriage.

What business? Constance’s gaze moved past him to Morgan, who stood waiting beside the carriage, eyes downcast.

And who is this new house slave, personal attendant? I have correspondence and accounts that require better management than Jackson provides.

Constant studied Morgan with the practiced eye of a plantation mistress, accustomed to evaluating slave purchases for their potential utility and problems.

Something in Morgan’s appearance made her pause, her eyes narrowing with suspicion she couldn’t quite articulate.

“This one seems delicate for heavy work,” she observed.

“Might be better suited for the fields.

” “I’ve assigned duties,” Harrison said with unusual firmness.

Morgan will attend me in the study and manage my personal affairs.

The emphasis on personal affairs made Constance’s jaw tighten, but she had learned over 14 years of marriage when to press her husband and when to retreat.

She turned and walked into the house without another word, her silk skirts rustling with barely contained anger.

Harrison showed Morgan to a small room off the study, barely large enough for a bed and wash stand, but separated from the slave quarters, and more importantly, separated from Constance’s awareness.

Your duties will be straightforward, he explained.

Manage my correspondence, maintain my files, keep the study clean.

In the evenings after Constance retires, you’ll return here to discuss the books you’ve been reading.

Discuss them, sir? Morgan asked carefully.

Yes, I told you I want to understand how you see things.

Consider it an educational experiment.

Harrison paused, recognizing the lie in his own words.

It wasn’t education he wanted.

It was connection with someone who existed outside the suffocating social structures that had governed every moment of his life since birth.

Over the following weeks, a routine developed.

Morgan worked silently during the day, invisible to Constants and the other household slaves.

But each evening, after the rest of the manor settled into sleep, Harrison would return to the study where Morgan waited with a book.

“What did you read tonight?” became Harrison’s greeting.

“Plato’s symposium,” Morgan might answer.

“Or Paradise Lost, or the Federalist Papers.

” And then they would talk, sometimes for hours, about philosophy and politics and ideas that Harrison had never discussed with anyone in his social circle, where conversations remained safely superficial.

Morgan’s perspective, shaped by existing in a body and social position that defied categorization, offered insights that challenged everything Harrison had accepted about the natural order of society.

Plato wrote about love between men, Morgan observed one November evening.

He described it as the highest form of connection, intellectual and spiritual, rather than merely physical.

“Do you think he was right?” Harrison felt his heart racing at the directness of the question.

I think, he said slowly, that we’re taught to see love in very limited ways.

Marriage is a contract, a joining of properties and bloodlines.

Physical desire is something shameful that respectable people hide.

But what if there are forms of connection that exist outside these categories? Forms of connection like what? Morgan asked.

And Harrison heard something in the youth’s voice that suggested this wasn’t an innocent question.

Like what we’re doing now, Harrison admitted, talking honestly without the masks we wear for society, seeing each other as complete persons rather than roles we’re assigned to play.

Morgan set down the book and looked directly at Harrison with an intensity that should have been forbidden between master and slave, but had become habitual in these private evenings.

Is that what you see when you look at me? A complete person? Yes, Harrison breathed.

And in that single word, he crossed a line that neither of them could uncross.

The first time Harrison touched Morgan came on a January night in 1851, 4 months after bringing the slave to Blackwood Manor.

They had been discussing Safo’s poetry, and Harrison had moved to sit beside Morgan on the study sofa to better see the text.

Their shoulders touched and neither moved away.

“Do you know why I really bought you in Charleston?” Harrison asked, his voice rough with suppressed emotion.

“I believe I do, sir.

Tell me,” Morgan turned to face him fully.

And Harrison saw in those eyes an understanding that went far beyond the youth’s years.

Because you saw in me a mirror of something in yourself, something that doesn’t fit the categories society demands, something that makes you feel alone, even when surrounded by people.

” Harrison’s hand moved to Morgan’s face, fingers tracing the line of the jaw that seemed to shift between feminine softness and masculine strength.

“What are you?” he whispered.

“What do you want me to be?” The question opened floodgates that Harrison had kept carefully sealed throughout his adult life.

His marriage to Constance had been physically functional but emotionally empty, producing children through duty rather than desire.

He had never experienced genuine passion, had never even understood what it might feel like until now.

What happened that night in the study violated every law, moral code, and social structure of the Antibbellum South.

Harrison knew that what he was doing constituted rape under any reasonable definition, a master taking what he wanted from enslaved property.

But Morgan responded with equal passion, and in the confusion of their coupling, Harrison found himself unable to categorize their interaction as simply male or female, master or slave, forced or consensual.

Morgan’s body offered everything Harrison had secretly craved without knowing how to name it.

feminine softness and masculine strength, submission and dominance, forbidden pleasures that society insisted couldn’t exist.

In Morgan’s arms, Harrison discovered the truth about himself that he had spent four decades hiding.

He desired both men and women, or perhaps more accurately, he desired connection that transcended gender entirely.

“This cannot happen again,” Harrison told Morgan afterward, already knowing the lie in his words.

I know, sir, Morgan replied, and they both understood that it absolutely would happen again.

What neither of them knew as they lay tangled together on the study sofa was that someone had been listening outside the door, someone who now possessed knowledge that could destroy them both, but who chose to wait, to watch, to document everything before deciding how to use this devastating information.

The game had begun, though neither player understood the rules yet.

And in 8 years, it would end with bodies, ash, and secrets that would haunt Georgia for generations.

For the next seven years, Harrison and Morgan maintained their secret relationship within the walls of Blackwood Manor, building a world that existed only in stolen moments and whispered conversations.

Harrison constructed elaborate justifications for spending hours alone in his study each evening, telling Constance he was managing Plex business correspondents with cotton brokers in New Orleans and banking associates in Charleston.

Constance, for her part, seemed content with the arrangement that kept her husband occupied and out of her bedroom, which she had long ago made clear was open to him, only for the purpose of attempting to produce a male heir that never came.

The routine they established became sacred ritual.

Each evening at precisely 9:30, after the household slaves had completed their duties, and Constance had retired to her room with a book and a glass of cherry, Harrison would light the oil lamps in his study, and wait for the soft knock on the door that announced Morgan’s arrival.

They would sit together on the leather sofa, sometimes talking for hours, sometimes falling into comfortable silence while they read their respective books, occasionally stealing glances at each other that communicated more than words ever could.

But their relationship evolved beyond physical passion into something neither had anticipated, genuine intellectual partnership and deep emotional love.

Harrison began teaching Morgan openly, bringing books on medicine, law, philosophy, and science from his frequent trips to Savannah and Charleston.

Morgan absorbed knowledge with stunning speed that sometimes frightened Harrison with its intensity, developing insights that Harrison found himself incorporating into his business decisions and political views.

You have the mind of a scholar, Harrison told Morgan one evening in 1854, watching the slave work through a complex mathematical problem from one of his engineering textbooks.

In a just world, you would be at Harvard or Yale, teaching others and contributing to human knowledge in ways that would change society.

In a just world, Morgan replied quietly, setting down the pencil with careful precision, I wouldn’t be your property.

We wouldn’t have to hide what we are to each other and our conversations wouldn’t be crimes that could get us both killed.

The statement hung between them like smoke, acknowledging the fundamental impossibility of what they were to each other.

They might love each other with a depth and authenticity that Harrison had never experienced in his legal marriage, but one owned the other.

Harrison could free Morgan with a simple signature on manum mission papers, but doing so would require explanations he could never give without destroying his own life, his daughter’s futures, and everything he had built.

“I could send you north,” Harrison offered, not for the first time, his voice heavy with the guilt that never left him.

to Boston or New York or Philadelphia, give you papers declaring you free, money to start a new life, letters of introduction to people who would help you establish yourself.

You could attend university, become a physician or lawyer, live as whoever you choose to be without hiding.

And never see you again?” Morgan asked, turning to face him fully, eyes reflecting the lamplight like mirrors holding fire.

live free but alone, knowing that the only person who ever truly saw me and loved me anyway is here, trapped in a life that’s killing him slowly.

It would be the right thing to do, Harrison insisted, but his voice lacked conviction even to his own ears.

For whom? Morgan challenged with the directness that had characterized their relationship from the beginning.

For me, to live free but isolated in a world that will never fully accept what I am.

Or for you to solve your conscience while losing the only person you’ve ever truly loved.

We both know the answer, Harrison.

We’re trapped in an impossible situation, bound together by love and separated by everything else.

Harrison had no answer to this because Morgan was correct.

They were imprisoned by circumstances neither could change, held captive by a social system that insisted certain forms of love couldn’t exist and therefore must be destroyed when discovered.

The only choice they had was whether to continue their relationship in secret, knowing it would eventually end in disaster or to end it voluntarily and live the rest of their lives diminished by the loss.

They chose to continue because even impossible love seemed better than no love at all.

And for seven years they maintained their delicate balance, walking the knife’s edge between genuine connection and inevitable destruction.

But their secret couldn’t remain hidden forever.

Someone was watching.

Someone who would ultimately use what she knew to destroy everything.

But before we reveal who was watching and what they planned to do with their terrible knowledge, you need to understand something critical about how plantation households actually functioned.

The white owners believed themselves invisible to their slaves, conducting their affairs and revealing their secrets as if the people who cleaned their rooms and served their meals were furniture rather than human beings with eyes, ears, and memories.

This fundamental misunderstanding of power would prove fatal for the Blackwood family because the person who had been observing Harrison and Morgan’s relationship from the very beginning was someone who understood that information was the only real currency available to the powerless.

And she had been collecting evidence with the patience of someone who knew that the right information deployed at the right moment could change everything.

Constance Blackwood was not a stupid woman, frigid by 19th century definition, perhaps focused on social standing and appearances, absolutely, but not stupid.

She had noticed the changes in her husband over the years since bringing Morgan to Blackwood Manor.

Harrison smiled more frequently, seemed distracted during social gatherings, spent hours alone in his study, when previously he had been restless and irritable.

For the first three years, Constance told herself that her husband had merely found an intellectual hobby to occupy his time.

She approved of Harrison staying home rather than gambling or drinking with other plantation owners.

She didn’t care what he did in his study as long as he maintained appearances in public and provided for their daughters futures.

But gradually, small details began accumulating in her mind, like water droplets that eventually overflow a basin.

The way Harrison’s eyes would search for Morgan during household activities, the quality of clothing he provided for this particular slave, far finer than any other house servant wore.

The locked cabinet in his study that appeared one day, its contents unknown, but carefully guarded.

In March of 1857, Constance’s suspicions crystallized into certainty through an accident of timing.

She had retired to her bedroom with one of her frequent headaches, taken Lord Darnham for the pain, and fallen into the deep sleep the drug provided.

But she woke after midnight, thirsty and disoriented, and walked toward the kitchen for water.

As she passed the study, she heard sounds that stopped her cold, soft gasps, whispered words, and the unmistakable rhythm of physical intimacy.

She moved closer to the door, which Harrison had left slightly a jar in his distraction, and looked through the narrow opening.

What she saw in that moment would haunt her for the rest of her life, and plant seeds of rage that would ultimately bloom into murder.

Harrison and Morgan lay together on the study sofa, bodies intertwined in ways that Constance’s strictly controlled mind could barely process.

But what shocked her more than the physical act was the expression on her husband’s face.

pure joy, complete abandon, an emotional openness she had never seen in 14 years of marriage.

He loved this slave, actually loved Morgan in ways he had never loved her, his legal wife, the mother of his children.

Constants backed away from the door silently, her mind racing through implications and consequences.

She could expose them publicly, but doing so would destroy the Blackwood family’s reputation along with Harrison’s.

She could have Morgan sold or killed, but Harrison would know who was responsible and the marriage would end in open warfare.

No, she needed to be strategic, patient, wait for the right moment to act in a way that would punish Harrison while preserving her own position and her daughter’s futures.

But Constance wasn’t the only person who had discovered the secret relationship.

Someone else had been watching, someone whose motivations were far more complicated than simple jealousy.

Margaret Chen had come to Blackwood Manor in 1852 as Constance’s personal ladies maid, purchased from a Charleston dealer who specialized in what he called exotic acquisitions for wealthy families seeking household slaves that reflected their cosmopolitan sophistication and worldly taste.

Half Chinese and half African-American, Margaret’s unusual heritage made her valuable to wealthy mistresses who wanted household slaves that served as living proof of their refined sensibilities and access to rare commodities.

Her delicate features, almond-shaped eyes, and graceful movements made her the perfect ornament for a plantation mistress who prided herself on possessing things that other women envied.

But Margaret’s true value lay far beneath the surface appearances that white owners obsessed over.

Her intelligence was razor sharp, capable of understanding complex social dynamics and power structures that most people never noticed.

And her ability to become invisible to white people who saw slaves as background furniture rather than human beings who observed everything gave her access to secrets that could destroy families, end careers, or start revolutions.

She had learned to read by watching her first mistress’s children study their lessons, memorizing letters and words until she could decode the newspapers and books that white people left lying around as if literacy was a white only ability that couldn’t be stolen through observation and determination.

She had learned to understand complex social dynamics by observing how power flowed through plantation households like water finding its level, pooling in unexpected places, creating currents and eddies that swept people into positions they never anticipated.

She watched who spoke to whom, who avoided whose gaze, who held secrets that could be weaponized, and who was vulnerable to manipulation through their desires, fears, or ambitions.

And she had learned to recognize love in all its forms by watching how it was denied to people like herself, commodified and controlled, punished when it crossed boundaries that society had drawn arbitrarily, but enforced with violence.

Margaret had noticed Harrison and Morgan’s relationship long before Constance did.

She had seen the way they looked at each other, had heard their whispered conversations late at night when she moved through the house performing duties no one remembered to assign, but everyone expected to be done.

She had even discovered the locked cabinet in Harrison’s study, and through patient observation, had learned its combination.

Inside that cabinet, she found Harrison’s private journals, eight years of entries documenting his relationship with Morgan in explicit detail.

The journals weren’t merely physical accounts.

They were love letters written to someone who couldn’t read them, philosophical meditations on the nature of desire and identity, and confessions of a man who had discovered his true self at age 42 through a relationship that society insisted couldn’t exist.

Margaret read those journals over several months, replacing them carefully after each session to avoid detection.

What she learned from them changed her understanding of Harrison Morgan and the possibilities of human connection.

These weren’t simply master and slave engaging in exploitation.

These were two people who had found in each other something genuine and transformative.

But Margaret also understood that such relationships were doomed in the world they inhabited.

The antibbellum south had no space for love that crossed racial boundaries, challenged gender categories, or threatened the fundamental structure of slave society.

Harrison and Morgan’s relationship was a ticking bomb that would eventually explode, destroying everyone nearby.

Margaret decided that when the explosion came, she would try to save at least one person from the wreckage.

Morgan.

The crisis came in August of 1858, triggered by something that should have been impossible, but somehow was not.

Morgan became pregnant.

The pregnancy revealed itself gradually through symptoms that Morgan initially tried to hide.

But by July, the physical changes became too obvious to conceal.

Morgan’s female organs, dormant for most of the youth’s life, had somehow activated fully.

The child growing inside defied every medical understanding of the error.

Harrison discovered the truth on an August morning when Morgan fainted while organizing correspondence.

He carried the unconscious slave to the small room off the study and called for Dr.

Benjamin Marsh, the physician who attended the Blackwood family and who Harrison trusted to maintain confidentiality about slave health issues.

Dr.

Marsh’s examination left him pale and shaking.

Colonel, this is beyond my medical knowledge.

This slave appears to be approximately 4 months pregnant.

But given the anatomical abnormalities you described when you purchased this slave, I don’t understand how this is possible.

It’s possible, Harrison said quietly, because I made it possible.

Dr.

Marsh understood immediately.

His face cycled through shock, disgust, and finally a kind of horrified pity.

Colonel, this is a catastrophe.

This pregnancy cannot come to term.

The social consequences alone would destroy your family.

But medically, I cannot predict what will happen during childbirth given this slave’s unique physiology.

The child itself might be might be what? Might inherit the parents condition.

Might be even more anatomically irregular.

Colonel, you must let me terminate this pregnancy immediately.

No.

The word came from Morgan, who had regained consciousness and was listening to the conversation with wide eyes.

“Please, sir, don’t let him kill my baby.

” Harrison looked between his longtime physician and the slave he loved, understanding that whatever decision he made in this moment would determine all of their fates.

“Dr.

Marsh, you will speak of this to no one.

Morgan, you will remain in this room until we determine how to proceed.

I need time to think.

” But time had already run out because Constance had been listening outside the study door and she had heard everything.

And what she planned to do with this information would make Harrison’s worst nightmares seem like pleasant dreams.

The confrontation that was about to unfold would involve poison, attempted murder, a slave’s desperate escape, and a plantation owner’s ultimate sacrifice.

But the truth about what really happened that August night in 1858 wouldn’t be revealed until 3 months later when a letter postmarked from Boston would force investigators to reopen the case and confront secrets that nobody in Savannah wanted to acknowledge.

The final game was about to begin, and the cost of playing would be measured in bodies.

That evening, as Harrison sat alone in his study, trying to formulate any plan that might preserve some fragment of the life he had built, Constants entered without knocking.

The door swung open with enough force to make the oil lamps flicker, casting dancing shadows across the walls that made the room feel like it was moving, breathing, waiting for blood to be spilled.

She closed the door behind her with a soft click that sounded louder than a gunshot in the sudden silence.

She stood before his desk with an expression of cold fury that made her beautiful in a terrible way.

Her pale skin almost luminescent in the lamplight, her dark eyes reflecting flames that seemed to burn from somewhere deep inside her soul.

The air in the room felt charged, electric, like the moment before lightning strikes.

Harrison could smell his wife’s perfume mixed with something else, something bitter and chemical that he couldn’t identify.

Later he would realize it was poison, that she had come to this confrontation already prepared to kill.

14 years, she said quietly, her voice so controlled that it was more frightening than screaming would have been.

Each word dropped into the silence like stones into still water, creating ripples that would spread outward forever.

14 years I have been your wife.

I gave you two daughters.

I managed your household, hosted your political allies, represented your family with dignity and grace, and all this time you were in love with a slave.

Harrison said nothing.

There was nothing to say that could justify or explain.

Not just any slave, Constance continued.

A slave whose body is as confused as your desires.

A slave who is now carrying your child.

Do you understand what you’ve done? Do you comprehend the magnitude of your betrayal? I never meant to hurt you, Harrison said, knowing how inadequate the words were.

You didn’t think of me at all, Constance replied.

That’s what hurts most.

Not that you found love elsewhere, but that you found it with someone who represents everything our society says cannot exist.

You’ve made a mockery of our marriage, our family, and the entire social order we depend upon.

What do you want from me? Constance moved closer to the desk, her voice dropping to a whisper that somehow carried more menace than shouting.

I want you to suffer as I have suffered.

I want you to understand what it feels like to love something you can never truly have, and I want Morgan to disappear.

No, you don’t have a choice, Constance said.

Morgan and the child both represent existential threats to this family.

I could expose you publicly, but that would hurt our daughter’s marriage prospects.

So instead, I will handle this privately.

Morgan will be sold tomorrow to a dealer who specializes in difficult slaves.

The dealer will take Morgan south to the sugar plantations in Louisiana, where life expectancy is measured in months.

Your child will die before it’s born, work to death inside Morgan’s body, and you will live with the knowledge that your selfish desires killed the only person you ever loved.

Harrison stood so abruptly that his chair fell backward.

If you do this, I will divorce you.

I will confess everything publicly.

I will destroy myself if necessary to stop you.

Then do it.

Constance challenged.

Destroy your reputation, your business relationships, your daughter’s futures.

Prove that your perversion matters more than your family.

See what happens when you admit to Savannah Society that you’ve been sodomizing a hermaphrodite slave for 8 years.

They stared at each other across the desk, and Harrison understood that Constants held every card.

She could destroy him socially while preserving her own position as the wronged wife.

She could sell Morgan legally as property.

She could even terminate the pregnancy and claim medical necessity.

“Please,” Harrison whispered, a proud man reduced to begging.

Please don’t do this.

Constance’s expression didn’t change.

Tomorrow morning, Morgan will be gone.

You will never speak of this again, and you will spend the rest of your life knowing that you could have prevented this if you had been stronger.

” She turned and left the study, closing the door with a soft click that sounded like a coffin lid falling into place.

Harrison sat in the darkness for hours, his mind racing through impossible scenarios.

He could flee with Morgan, but where could they go? He could kill Constants, but that would lead to his own execution.

He could free Morgan and face the social consequences, but that wouldn’t save the child or allow them to be together.

In the end, he made a decision that he hoped would save Morgan’s life, even if it couldn’t save their relationship.

He walked to the small room where Morgan lay sleeping, woke the slave gently, and explained what was about to happen.

I’m going to give you something, Harrison said, unlocking the safe behind his desk and removing a leather pouch heavy with gold coins.

Enough money to buy your freedom three times over.

And I’m going to give you papers declaring you free, backdated to before you became pregnant.

And I’m going to tell you where to go.

Charleston, to a boarding house on Queen Street run by a Quaker woman named Sarah Grimkey.

She helps escaped slaves reach the north.

You’ll go there tonight before Constance can act.

But what about you? Morgan asked, tears streaming down her face that Harrison still found beautiful in ways that transcended gender.

I’ll tell Constance you escaped.

She’ll be furious, but she’ll also be satisfied that you’re gone.

I’ll face whatever consequences come.

I don’t want to leave you.

I know, but you have to think about the child now.

Our child deserves a chance at life, even if we can’t be together.

They held each other until nearly dawn, knowing it was the last time.

Then Morgan, dressed in men’s clothing, Harrison had stolen from the slave quarters, took the money and papers, and slipped out into the humid Georgia night.

Harrison watched from his study window as Morgan disappeared into the darkness, feeling something inside himself die.

He had chosen to save Morgan’s life at the cost of his own happiness.

It was the only moral choice available, but it felt like death nonetheless.

He walked to his desk, opened the middle drawer, and removed the pistol he kept loaded for protection.

He sat down, placed the pistol on the desk before him, and tried to imagine a future without Morgan.

He couldn’t.

What happened next would be debated by investigators for months afterward, but the evidence suggested that Harrison Blackwood sat in his study until midm morning when Constance came to gloat over Morgan’s impending sale and found her husband’s desk empty and the door to Morgan’s room a jar.

The screaming brought the entire household running.

They found Harrison on the bed in Morgan’s small room, dressed in Morgan’s clothing, surrounded by 8 years worth of private journals that documented every moment of their relationship.

He had apparently swallowed a massive dose of Lordunham mixed with arsenic, creating the combination that produced the expression of extreme agony mixed with impossible ecstasy that doctors would note in their reports.

But Harrison hadn’t died immediately.

Before losing consciousness, he had used his own blood to write a final message on the wall above the bed.

I die loving Morgan.

My only sin was not doing so openly.

The Blackwood family’s first instinct was to hide everything.

They removed the journals, washed the walls, stripped the room, and prepared to bury Harrison with full honors as a respected plantation owner who had died of sudden natural causes.

Doctor Marsh agreed to sign death certificates attributing Harrison’s death to heart failure.

But Constance, in her rage and pain, made a fatal mistake.

She told her closest friend, Eleanor Merryweather the true story over tea 3 days after Harrison’s death.

Eleanor, horrified and fascinated in equal measure, told her sister.

Within 2 weeks, rumors were spreading through Savannah society like cudzu vines.

The police, pressured by gossip and political enemies of the Blackwood family, opened an investigation.

They interviewed household slaves who confirmed that Harrison had been unnaturally close to Morgan.

They found chemical residue in Harrison’s study, proving he had mixed the lordinum and arsenic himself.

They tracked down Dr.

Marsh, who eventually admitted what he knew about Morgan’s pregnancy under threat of losing his medical license.

and they discovered something that changed the entire investigation.

Margaret Chen had stolen Harrison’s journals before the family could destroy them.

She had hidden them in the slave quarters and anonymously told the police where to find them.

The journals became public record during the coroner’s inquest.

Their contents shocked even hardened legal professionals.

Harrison had documented not just his sexual relationship with Morgan, but his philosophical and emotional journey toward understanding himself and his desires.

He had written about the artificial nature of gender categories, the human capacity for love that transcended social boundaries, and his belief that future generations would look back on the 1850s south with the same horror that his generation viewed medieval barbarism.

They will call us monsters, Harrison had written in his final entry, dated the night before his death.

But the true monstrosity is a society that makes it impossible for people to love honestly.

I pray that Morgan and our child survive to see a world where they can exist without shame.

If this journal is ever found, let it stand as testimony that love existed here, forbidden, but real.

The public scandal destroyed the Blackwood family’s reputation.

Constance and her daughters left Savannah within a month, moving to her family’s estate in Virginia and never speaking publicly about Harrison again.

Blackwood Manor was sold to settle debts, its slaves auctioned and scattered across the South.

But then came the letter.

3 months after Harrison’s death, when investigators thought the case was finally buried along with the colonel’s body, a Manila envelope arrived at the police station, postmarked from Boston.

Inside was a document that would force everyone to confront a truth far more disturbing than anything they had imagined.

What Morgan revealed in that letter would prove that Harrison Blackwood hadn’t committed suicide at all, that Constance Blackwood’s rage had driven her to attempted murder, that Margaret Chen had saved Morgan’s life at the cost of nearly taking Constances, and that Harrison’s final act had been not cowardice, but the ultimate expression of love and sacrifice.

The truth, as it turned out, was even more tragic than the lie.

3 months after Harrison’s death, the police received a letter postmarked from Boston.

It contained a sworn statement from Morgan written in elegant handwriting explaining what had truly happened that night.

According to Morgan’s account, Constance hadn’t simply threatened to sell Morgan.

She had entered the small room where Morgan slept, accompanied by Margaret Chen, and had attempted to poison Morgan’s evening meal.

But Margaret, who had been watching and listening for months, had switched the poison plate with a clean one.

Constance, enraged by Margaret’s betrayal, had attacked Morgan physically.

In the struggle, Margaret had struck Constance with a heavy candlestick, likely intending only to stop the attack, but delivering a blow that left Constants unconscious and bleeding.

Morgan and Margaret, both terrified of what would happen if Constants regained consciousness and accused them, had fled together that night.

They had used Harrison’s money to travel north, following the Underground Railroad routes that Margaret had learned about through secret connections with abolition networks.

But here was the stunning revelation.

Harrison hadn’t committed suicide at all.

He had discovered Constance unconscious in Morgan’s room, understood what had happened, and made a decision that revealed the full depth of his love and guilt.

He had dressed in Morgan’s clothing, positioned himself on Morgan’s bed, consumed the poison that Constance had prepared for Morgan, and written his final message.

He had effectively confessed to a crime he hadn’t committed in order to protect Morgan and Margaret from murder charges.

He gave his life for mine, Morgan wrote in the letter.

Not just on that final night, but every day we spent together.

He loved me despite the impossibility of our situation.

He honored me despite my inability to exist in the categories society demands.

And in the end, he sacrificed everything to give me and our child a chance at freedom.

The letter went on to explain that Morgan had safely reached Boston, had been taken in by abolitionists who provided medical care during the pregnancy, and had given birth to a healthy child.

The baby, whose gender Morgan did not specify in the letter, was being raised in a community that asked no questions about unusual circumstances.

“I will never return to Georgia,” Morgan wrote.

“But I want the world to know that what Harrison and I shared was love in its truest form.

We were not monsters engaging in perverse acts.

We were two people who found connection in a world that insisted such connection couldn’t exist.

His journals prove this.

Let them stand as testimony.

The police showed Constance this letter and asked if she wanted to press charges against Morgan and Margaret for assault and attempted murder.

But Constance, faced with the choice between prosecuting the case publicly or letting it die quietly, chose silence.

She acknowledged that yes, she had entered Morgan’s room that night.

Yes, there had been a struggle.

But no, she didn’t wish to pursue charges.

She wanted only to forget that Harrison Blackwood had ever lived.

The case was officially closed in January of 1859.

Harrison’s death was ruled a suicide.

Morgan and Margaret were declared fugitives.

who would be arrested if they ever returned to Georgia.

And the Blackwood family’s story became one of those scandals that Savannah Society referenced in whispers but never discussed openly.

But the journals that Margaret had preserved continued to circulate in abolitionist circles.

Frederick Douglas referenced them in a speech in 1860 using Harrison’s writings as evidence that the slave system corrupted every human relationship it touched.

Harriet Beestowe reportedly read them and incorporated some of Harrison’s insights into her later writings on slavery and sexuality.

And in Boston, a woman who claimed to be Morgan, published a memoir in 1885, 30 years after the scandal, titled Neither nor Nor nor a life beyond categories.

The book detailed growing up as a hermaphrodite in slave society, the years at Blackwood Manor, and the Escape to Freedom.

It was banned in most southern states, but became required reading in certain progressive circles in the north.

The memoir’s final chapter addressed Harrison directly.

You asked me once what I was.

I told you that I was whatever you wanted me to be.

But the truth, which I understood only after reaching freedom, is that I was always exactly what I appeared to be, a human being deserving of love and dignity.

You saw that truth before I did.

You loved me before I learned to love myself, and you died defending my right to exist.

That is a love worth remembering, regardless of how society judged it.

Morgan died in 1902 at the age of 67, having lived openly in Boston as a person of ambiguous gender for over 40 years.

The child, whose identity Morgan never publicly revealed, continued living in Boston as a prominent physician who specialized in treating patients whose bodies didn’t conform to typical anatomical categories.

Constance Blackwood died in Virginia in 1890, having never remarried, and having maintained until her death that her husband had betrayed her unforgivably.

But among her possessions, her daughters found a single item that suggested a more complicated truth.

One of Harrison’s journals, the one from 1851, that documented the early months of his relationship with Morgan.

Constants had kept it hidden for over 30 years, reading it repeatedly based on the wear patterns on its pages.

Whatever she thought about her husband’s choices, she had been unable to completely let go of him.

The legacy of Harrison Blackwood and Morgan’s Impossible Love story continued long after their deaths, rippling through American history in ways that most people never realized.

The journals that Margaret had preserved continued to circulate in abolitionist circles throughout the 1860s.

Frederick Douglas referenced them in a speech in 1860, using Harrison’s writings as evidence that the slave system corrupted every human relationship it touched, turning love into property transactions and passion into crimes against nature.

Harriet Beestowe reportedly read them and incorporated some of Harrison’s philosophical insights into her later writings on slavery, sexuality, and the artificial categories that society used to control human desire.

And in Boston, the woman who claimed to be Morgan published a memoir in 1885, 30 years after the scandal titled Neither Nor, a life beyond categories.

The book detailed growing up as a hermaphrodite in slave society, the years at Blackwood Manor, where forbidden love bloomed in secret chambers, and the dramatic escape to freedom that had cost one man his life but saved two others.

It was banned in most southern states, but became required reading in certain progressive circles in the north, whispered about in universities and discussed in private gatherings, where people dared to question whether society’s rigid categories of gender, race, and sexuality might be more fluid than anyone wanted to admit.

The memoir’s final chapter addressed Harrison directly, speaking to him across the grave.

You asked me once what I was.

I told you that I was whatever you wanted me to be.

But the truth which I understood only after reaching freedom is that I was always exactly what I appeared to be.

A human being deserving of love and dignity.

You saw that truth before I did.

You loved me before I learned to love myself.

And you died defending my right to exist.

That is a love worth remembering regardless of how society judged it.

Morgan died in 1902 at the age of 67, having lived openly in Boston as a person of ambiguous gender for over 40 years, refusing to conform to expectations that insisted on calling them either man or woman.

The child, whose identity Morgan never publicly revealed to protect them from scandal and persecution, continued living in Boston as a prominent physician who specialized in treating patients whose bodies didn’t conform to typical anatomical categories.

In private medical journals that weren’t published until the 1950s, this mysterious doctor wrote about their own experiences being born to a hermaphrodite parent, describing anatomical characteristics that suggested they too existed between traditional gender categories.

Constance Blackwood died in Virginia in 1890, having never remarried, and having maintained until her death that her husband had betrayed her unforgivably.

But among her possessions, her daughters found a single item that suggested a more complicated truth.

One of Harrison’s journals, the one from 1851 that documented the early months of his relationship with Morgan, filled with observations about discovering genuine connection for the first time in his life.

Constants had kept it hidden for over 30 years, and the wear patterns on its pages proved she had read it repeatedly.

The margins contained her own annotations, bitter comments at first, but gradually evolving into something that looked almost like understanding, or perhaps just the recognition that she had lost a battle against forces more powerful than social convention could contain.

Whatever she thought about her husband’s choices, whatever rage and pain she carried to her grave, she had been unable to completely let go of him.

The journal was buried with her according to her final wishes, taking whatever private thoughts she’d had about Harrison and Morgan into the earth forever.

This mystery shows us how rigid social categories and moral systems can trap people in impossible situations, leading to tragedies that might have been avoided in a more flexible society.

Harrison Blackwood and Morgan loved each other in ways that challenged every assumption of their era about race, gender, sexuality, and power.

That love destroyed them, but it also revealed truths that their society desperately needed to confront about the arbitrary nature of the categories we use to define what’s natural, what’s moral, and what’s human.

Harrison discovered that desire doesn’t fit neatly into boxes labeled male or female, that love can exist across boundaries that society insists are uncrossable, and that the most authentic version of ourselves often lives in the spaces between the categories we’re forced to occupy.

Morgan proved that bodies which refuse to conform to expectations don’t need to be corrected or hidden, but honored for showing us that human diversity extends far beyond what we’ve been taught to recognize.

Their story isn’t just about forbidden love or scandal.

It’s about the violence that societies commit when they demand that people conform to categories that don’t fit.

When they criminalize connections that challenge the established order.

And when they destroy rather than celebrate the natural variations in human sexuality, gender, and desire.

What do you think of this story? Do you believe Harrison’s suicide was truly an act of love, or was he running from consequences he couldn’t face? Do you think Constance was a villain? Or was she a victim of a society that gave women no power except through their husbands? Could Morgan and Harrison’s relationship be called love given the power imbalance inherent in slavery? Or was it always tainted by the impossibility of consent between master and slave? Leave your comments below and share your thoughts.

If you enjoyed this tale and want more dark dark historical mysteries that challenge everything we think we know about the past, subscribe to this channel, hit the notification bell, and share this video with someone who isn’t afraid to confront uncomfortable truths about American history.

History isn’t simple.

People aren’t simple.

Love definitely isn’t simple.

And sometimes the most important stories are the ones that make us most uncomfortable.

the ones that force us to question whether the categories we’ve accepted as natural and inevitable might actually be prisons we’ve built ourselves.

See you in the next video where we’ll uncover another buried secret that America tried to forget.

News

Ilhan Omar ‘PLANS TO FLEE’…. as FBI Questions $30 MILLION NET WORTH

So, while Bavino is cracking down in Minnesota, House Republicans turning the heat up on Ilhan Omar. They want to…

FBI & ICE Raid Walz & Mayor’s Properties In Minnesota LINKED To Somali Fentanyl Network

IC and the FBI move on Minnesota, touching the offices of Governor Tim Walls and the state’s biggest mayors as…

FBI RAIDS Massive LA Taxi Empire – You Won’t Believe What They Found Inside!

On a Tuesday morning, the dispatch radios in hundreds of Los Angeles taxi cabs suddenly stopped playing route assignments. Instead,…

Brandon Frugal Finally Revealed What Forced Production to Halt in Season 7 of Skinwalker Ranch….

The Secret of Skinwalker Ranch became History Channel’s biggest hit. Six successful seasons documenting the unknown with real science and…

1 MINUTE AGO: What FBI Found In Hulk Hogan’s Mansion Will Leave You Shocked….

The FBI didn’t plan to walk into a media firestorm, but the moment agents stepped into Hulk Hogan’s Clearwater mansion,…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage… It started like any other evening…

End of content

No more pages to load