On a humid August night in 1851, somewhere along the tobacco plantations of Southside, Virginia, a slave trader’s ledger recorded an entry that would never be fully explained.

The notation read, “One specimen, age approximately 19, purchased from Charleston Market, unique physical characteristics.

Price 28470, nearly four times the standard rate.

” The buyer’s name was recorded as Thomas Rutled, owner of Belmont Estate.

What happened over the next 14 months would result in three deaths, the complete abandonment of a prosperous plantation, and the systematic destruction of every document related to the estate’s activities during that period.

Court records from Prince Edward County show that in November 1852, the property was sold at auction for a fraction of its value with the stipulation that certain rooms remain sealed in perpetuity.

Local historians have found 17 separate references to the Rutled incident in private letters and diaries from the era.

Yet, every official record has been expuned.

The few surviving accounts speak of an obsession so consuming it destroyed everything it touched.

An obsession that began with a single enslaved person whose very existence challenged every assumption of the time.

Southside Virginia in 1851 was a world unto itself.

A patchwork of sprawling plantations separated by dense forests of oak and pine, connected by rutted dirt roads that turned to thick red mud whenever the autumn rains came.

This was tobacco country, where fortunes were built on the backs of enslaved laborers, and a man’s worth was measured in acres and human property.

The air itself seemed heavier here, thick with humidity and the acrid smell of tobacco leaves hanging in the curing barns.

Belmont Estate sat on the eastern edge of Prince Edward County, a 30,000 acre property that had been in the Rutled family since 1783.

The main house was a Georgianstyle mansion of red brick with white columns and black shutters, impressive but not ostentatious, befitting a family that prided itself on old money and older traditions.

42 enslaved people worked the property, living in a double row of cabins that stretched behind the main house like a small village of their own.

Thomas Rutled was 37 years old that summer, a tall man with the kind of refined features that came from generations of selective breeding among Virginia’s planter class.

He had inherited Belmont 7 years earlier upon his father’s death, along with considerable debts that he had worked tirelessly to repay.

By all accounts, he was known as a stern but not particularly cruel master.

He managed his property with the cold efficiency expected of successful planters, neither better nor worse than his neighbors in his treatment of those he enslaved.

His wife, Catherine, was 10 years his junior, the daughter of a Richmond merchant who had made his fortune in the shipping trade.

She had married Thomas in 1847, bringing with her a substantial dowy that had helped ease the plantation’s financial troubles.

Catherine was considered a great beauty, slim and pale with dark hair she wore in the elaborate styles fashionable among Virginia society.

But there was something fragile about her, something that suggested she might shatter at the slightest pressure.

She had given birth to a stillborn son in 1849, and the loss had changed her in ways that worried the few people close enough to notice.

She spent long hours in her upstairs sitting room reading novels and staring out the window at the fields beyond.

The Rutigges lived the life expected of their class.

They attended Christ Church in nearby Farmville, hosted dinners for neighboring planters, and maintained the elaborate social rituals that kept Virginia’s planter aristocracy functioning.

Thomas sat on the county board and served as a magistrate.

Catherine organized charitable societies and supervised the household slaves with distant efficiency.

On the surface, everything appeared perfectly normal, a prosperous plantation run by respectable people who understood their place in the social order.

But beneath that surface, both Thomas and Katherine Rutled were deeply unhappy in ways they could never articulate, even to themselves.

Thomas felt a knowing emptiness that no amount of success could fill.

Catherine felt invisible, fading away a little more each day.

They were two people living parallel lives in the same house, barely touching, barely seeing each other.

It was into this atmosphere of quiet desperation that the slave trader Samuel Wickham arrived on the morning of August 14th, 1851.

Wickham was a frequent visitor to the plantations of Southside, Virginia.

a thin man with sharp features and sharper eyes, always dressed in a black suit that had seen better days.

He specialized in what he called specialty acquisitions, slaves with particular skills or unusual characteristics that might command premium prices from wealthy buyers.

He had been traveling the coastal cities for the past 6 months, attending every major slave auction from Baltimore to Savannah, looking for inventory that would interest his most discriminating clients.

Thomas received him in the plantation office, a small building separate from the main house where he conducted business.

Wickham accepted a glass of whiskey and made small talk about tobacco prices and the political situation.

There was always tension in the air those days, debates about territories and slavery that made prudent men nervous about the future.

Then he leaned forward, his voice dropping to a more confidential tone.

I’ve acquired something unusual, Mr.

Rutled.

Something I think might interest a man of your sophistication.

Thomas raised an eyebrow.

I’m not in the market for additional field hands at the moment, Mr.

Wickham.

This isn’t a field hand.

Wickham pulled a folded paper from his coat pocket, a bill of sale with detailed notations.

This is a unique specimen purchased 3 weeks ago at the Charleston Market.

The previous owner was a physician, Dr.

Albert Strad, who acquired this slave from an estate sale in New Orleans.

The slave was raised in a household, educated to some degree, can read and write, which is unusual, but that’s not what makes this one special.

He paused, watching Thomas’s face carefully.

This slave is what medical men call a hermaphrodite, born with the physical characteristics of both male and female.

It’s a genuine medical curiosity, the kind of thing you see perhaps once in a thousand births.

Dr.

Strad documented the condition before his death.

The slave is currently healthy, young, perhaps 19 or 20 years old.

I’m authorized to offer it for sale to the right buyer for the right price.

Thomas felt something shift inside him, a sensation like falling, both male and female, neither one thing nor the other, a perfect ambiguity.

The slave has been trained since childhood to accept medical examination.

Dr.

Strad ensured complete compliance.

It understands its unique nature and has learned not to resist inspection.

Wickham’s smile became knowing.

I’m asking 2,47, which is well above market rate, but consider what you’re purchasing.

This is a genuine phenomenon and beyond any scientific interest.

” He let the sentence hang in the air.

Thomas felt his mouth go dry.

He thought of Catherine upstairs, staring out the window at nothing.

He thought of his own suffocating sense of emptiness.

“I’ll need to see the slave first.

” Of course, I have the wagon just outside.

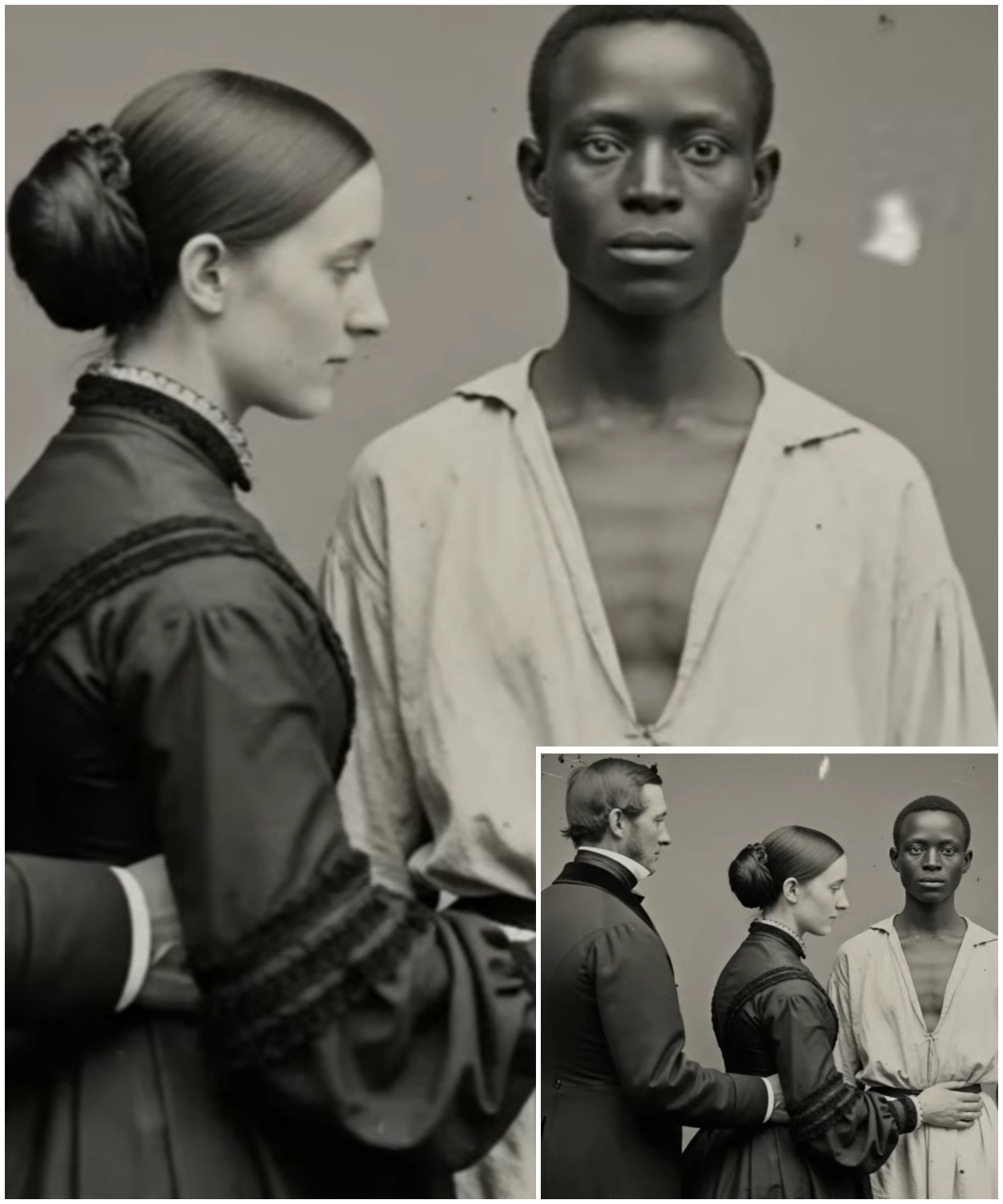

20 minutes later, Thomas Rutled stood in the office looking at Jordan for the first time.

The slave stood in the doorway, hands clasped, eyes downcast in the posture of submission that every enslaved person learned from childhood.

Jordan wore a simple cotton shift that revealed little, but even from across the room, Thomas could see what Wickcham had described.

The strange ambiguity that defied easy categorization.

The face was beautiful in a way that belonged to neither sex entirely, delicate features with high cheekbones, full lips, large dark eyes framed by long lashes.

The hair was black, cropped short.

The body beneath the shift suggested curves that might have been feminine or might have been something else entirely.

The hands were graceful, the bare feet narrow and well-formed.

But it was the voice that truly captured the impossible nature of this person’s existence.

When Wickcham ordered Jordan to speak, what emerged was a sound pitched somewhere between male and female registers belonging fully to neither.

My name is Jordan, master.

I am 19 years old.

I can read, write, and cipher.

I have been trained to submit to medical examination without resistance.

I am obedient and willing to serve.

The words were clearly rehearsed, delivered with the flat affect of someone who had learned to suppress all personality.

But Thomas heard something beneath them, a quiet intelligence, an awareness that this person understood exactly what they were and what was being sold.

Thomas stared, unable to look away from this person who seemed to exist in some impossible space between categories.

He felt a fascination rising in him that he didn’t fully understand.

A need to comprehend this mystery standing before him.

I’ll take it, he heard himself say.

The transaction was completed within the hour.

Wickham accepted a bank draft, handed over the papers, and departed with the satisfied heir of a man who has made an excellent sale.

Thomas stood alone in the office with his new acquisition, feeling excitement and unease in equal measure.

“Come with me,” he said finally.

“I need to determine where you’ll be housed.

” He didn’t take Jordan to the slave quarters behind the main house.

Instead, he led the slave to a small cottage that sat at the edge of the formal gardens, a structure that had once housed his father’s valet, but had stood empty for years.

It was isolated enough to be private, but close enough to the main house to be convenient.

“You’ll stay here,” Thomas said.

“I’ll send for you when I’ve decided on your duties.

” Jordan stood in the center of the cottage’s single room, hands still clasped, face expressionless.

Yes, master.

Thomas returned to the main house, his mind churning.

That evening at dinner, he told Catherine about the acquisition, choosing his words carefully.

He described Jordan as an unusually educated house slave with a unique background that he had purchased as a potential addition to the household staff.

Catherine showed little interest at first, picking at her food.

If you think it’s necessary, Thomas, the slave has uncommon characteristics.

The previous owner was a physician who valued the slave for medical reasons.

It might be useful to have someone with such training in the household.

Something in his tone made Catherine look up, studying his face.

What kind of characteristics? Thomas hesitated.

It’s difficult to explain.

Perhaps you should see for yourself.

The next morning, he brought Catherine to the cottage to meet Jordan.

Catherine stood in the doorway, looking at the slave with initial disinterest that slowly transformed into something else as she took in Jordan’s appearance.

The ambiguous beauty, the impossible to categorize presence, the strange quality of existing between worlds.

“This is Jordan,” Thomas said, watching his wife’s face.

“The slave I mentioned.

” Catherine moved closer, circling Jordan slowly, her expression unreadable.

Jordan stood perfectly still, eyes downcast, breathing slowly and evenly.

What exactly makes this slave so unusual? Catherine asked.

Thomas explained, keeping his voice clinical, describing Jordan’s condition in medical terms.

As he spoke, he watched something shift in Catherine’s expression.

the same fascination he had felt, the same disturbed curiosity.

When he finished, Catherine was silent for a long moment.

Then she reached out, her hand hovering near Jordan’s face before falling back to her side.

May I May I examine for myself to understand? Thomas felt his heart begin to race.

if you wish.

What happened in that cottage over the following hour would mark the beginning of their descent.

Catherine’s examination started with clinical curiosity, studying Jordan’s face, the slave’s hands, asking questions about Dr.

Straoud’s documentation, but gradually, almost imperceptibly, it became something else.

Something neither Thomas nor Catherine could have named, but both recognized.

When they finally left the cottage and returned to the main house, they didn’t speak of what had happened.

But that night, for the first time in months, they came together in their marriage bed, drawn to each other, not by love or affection, but by a shared secret, a shared fascination with the impossible person who now lived in the cottage beyond their garden.

It was the beginning of an obsession that would consume them both.

The autumn of 1851 in Prince Edward County brought cooler temperatures and the hard work of tobacco harvest.

But inside Belmont Estate, something far more troubling was taking root.

Within a week of Jordan’s arrival, a new pattern had established itself.

One that the other enslaved people on the property noticed immediately, even if they didn’t fully understand it.

Jordan was moved from the cottage to a small room on the third floor of the main house, officially designated as Catherine’s personal maid.

The slave was given new clothes, better food than the field hands received, and seemed to exist in a strange privileged isolation from the rest of the enslaved community.

But the other slaves saw things that troubled them.

They saw how the master and mistress would both disappear upstairs at odd hours.

They heard sounds through the walls that were difficult to interpret.

They noticed how Jordan would emerge from that thirdf floor room, moving carefully, face blank, eyes distant.

Harriet, the plantation’s cook, was one of the first to sense that something was deeply wrong.

She had worked at Belmont for 20 years, had seen three generations of rutages, and had developed the keen observational skills necessary for survival in her position.

She noticed how Thomas had stopped managing the plantation properly, how bills piled up on his desk unopened, how he would forget meetings with neighboring planters.

She noticed how Catherine had stopped eating properly, growing thinner and paler by the week, spending hours locked in that thirdf floor room.

One morning in late September, Harriet tried to speak with Jordan in the kitchen.

The younger slave had come down to fetch breakfast for the master and mistress, moving with that strange, careful gate, face showing nothing.

Child, Harriet said quietly, glancing around to make sure they were alone.

Are they hurting you up there? You can tell me.

I’ve been here long enough to know when something ain’t right.

Jordan looked at her with those unreadable eyes.

I have everything I need, Aunt Harriet.

The master and mistress treat me well.

That ain’t what I asked.

A flicker of something crossed Jordan’s face so quick Harriet almost missed it.

Pain perhaps, or resignation.

Then it was gone, replaced by that careful blankness.

I do what I was born to do, Jordan said softly.

What I was trained to do.

It’s easier when you don’t think about it.

Before Harriet could respond, footsteps sounded on the stairs above.

Jordan gathered the breakfast tray and disappeared back upstairs, leaving Harriet alone in the kitchen with a sick feeling in her stomach.

The whispers began in the slave quarters that night.

People spoke in low voices about the strange new slave who never joined them in the evenings, who never attended the secret prayer meetings in the woods, who seemed to exist in some separate world entirely.

Some of the older slaves remembered stories about conjure and hudoo, about people born with unusual powers who could bewitch their masters.

Others dismissed such talk as superstition, but couldn’t explain what was happening in the big house any better.

Meanwhile, upstairs in that third floor room, Thomas and Catherine were discovering depths to their obsession that neither had imagined possible.

Thomas had acquired books on anatomy and medical science, texts that discussed rare conditions and unusual cases.

He would spend hours reading these volumes, then comparing what he learned to his observations of Jordan.

He began keeping a journal, though its contents were far different from the meticulous plantation records he had maintained for years.

This journal was locked in a drawer, hidden even from Catherine, filled with notations and sketches that would later be destroyed.

Catherine’s fascination took a different form.

She would spend entire afternoons in Jordan’s room, having the slave dress and undress repeatedly, styling Jordan’s hair in different ways, trying to understand this person who seemed to shift between categories depending on clothing and presentation.

She commissioned new garments from a seamstress in Farmville.

Some cut in feminine styles, others more masculine, all designed to either emphasize or obscure Jordan’s ambiguous form.

“I want to understand what you are,” Catherine told Jordan one afternoon.

“Whether you’re truly both or neither, or something else entirely,” Jordan, standing motionless while Catherine adjusted a dress collar, replied in that careful, neutral voice, “does it matter, mistress? I am what you see, what you want to see.

But what do you see when you look at yourself? For a moment, Jordan’s mask slipped.

I see what everyone has always seen.

Something to be examined.

Something to be understood.

Something that exists only to satisfy other people’s curiosity.

Catherine’s hand stilled.

That’s not I don’t mean to.

But she couldn’t finish the sentence because they both knew it was exactly what she meant.

What both she and Thomas meant.

every time they summoned Jordan to that room.

Every time they studied and questioned and tried to categorize what could not be categorized.

As September turned to October, the household settled into a routine that looked almost normal from the outside.

Thomas managed the plantation with mechanical efficiency when he bothered to manage it at all.

Catherine maintained her social obligations when absolutely necessary, though she declined more invitations than she accepted.

The other slaves went about their work, whispering among themselves, but knowing better than to question their master’s behavior openly.

But those who paid attention could see the signs of decay.

Thomas had lost weight, his clothes hanging loose on his frame.

His eyes had taken on a feverish quality, and he rarely slept more than a few hours before rising to pace the halls or retreat to his study.

Catherine had stopped wearing her elaborate dresses, preferring simple dark gowns that hung on her increasingly skeletal body.

Her hair, once her pride, was often left in a simple knot, unwashed for days at a time.

and Jordan.

Jordan remained exactly as before, calm, blank, obedient, moving through the house like a ghost, speaking only when spoken to, existing in that strange liinal space between person and property, between master and slave, between the living and something that merely survived.

It was in late October that the first true crisis occurred.

Two of the field hands, brothers named Samuel and Isaac, attempted to run away.

They were caught by patrollers 15 mi from the plantation and brought back in chains.

Thomas, roused from his obsessive studies, was forced to deal with the situation as plantation discipline required.

He had them whipped, 10 lashes each, administered in front of the assembled slaves as a warning to others.

But his heart wasn’t in it.

He watched the punishment with distant eyes, his mind clearly elsewhere.

After it was done, and the other slaves had been dismissed to their quarters, he stood alone in the yard, looking at the whipping post with an expression that might have been guilt or might have been nothing at all.

Harriet, watching from the kitchen window, saw him there and understood something fundamental.

The master wasn’t just obsessed with Jordan.

He was disappearing into that obsession, becoming less substantial with each passing day, less present in the world of normal human concerns.

That night, she heard the master and mistress in the third floor room again.

But this time, through the walls and floors, she heard something new.

Raised voices.

An argument.

The words weren’t clear, but the emotion was unmistakable.

Anger, perhaps, or desperation.

The next morning, Jordan came to the kitchen for breakfast, moving even more carefully than usual.

Harriet had said nothing, but when their eyes met across the kitchen, she saw something in Jordan’s expression that chilled her to the bone.

It was the look of someone who knew exactly how this would end, and had resigned themselves to it.

November arrived with unseasonably cold winds that stripped the last leaves from the trees, and sent the enslaved workers scrambling to prepare for winter.

But inside Belmont Estate, a different kind of cold had settled, the frigid atmosphere of a household coming apart at the seams.

The plantation was failing.

Not obviously, not yet, but those who understood such things could see the signs.

Fields that should have been planted with winter wheat layow.

Fences needed mending, but remained broken.

The tobacco from the previous harvest sat in the barns, much of it unsold because Thomas had failed to negotiate contracts with buyers in Richmond.

Bills accumulated on his desk, many unopened, some months overdue.

Neighboring planters began to notice.

They remarked among themselves about Thomas Rutled’s absence from church, his failure to attend county board meetings, the way he would accept dinner invitations, and then send his regrets at the last moment.

Some attributed it to grief over his wife’s continued poor health.

Others whispered about financial troubles or drink.

None of them guessed the truth because the truth was too strange for their world to accommodate.

Catherine had stopped even pretending to maintain her social obligations.

She rarely left the main house, and when she did venture out to the garden or the nearby paths, she moved like a woman walking in her sleep.

Her friends from the charitable societies stopped calling after their visits were repeatedly turned away by servants with polite excuses.

The minister from Christ Church came once to inquire after her health and was told she was indisposed.

He left looking troubled but didn’t return.

The enslaved people on the property understood in the way that the powerless always understand the powerful that something was deeply wrong.

The carefully maintained distance between master and slave had broken down in ways that made everyone uncomfortable.

Thomas no longer inspected the work or gave clear orders.

Catherine no longer supervised the household with her former efficiency.

The plantation ran on momentum and the initiative of the slaves themselves who understood that their survival depended on maintaining routines even when their masters had abandoned them.

And then there was Jordan.

The other enslaved people had initially viewed Jordan with suspicion tinged with fear.

This stranger who had been brought in from outside, who lived in the big house, who seemed to have some inexplicable hold over the master and mistress.

But as weeks turned to months, suspicion evolved into something closer to pity.

They saw how Jordan existed in a kind of prison, isolated from the community in the quarters, locked into a role none of them could fully comprehend, but all recognized as deeply wrong.

Some of the women tried to reach out.

Dileia, who had been Catherine’s maid before Jordan arrived, approached the younger slave one afternoon when they happened to pass in the hallway.

“If you need anything,” Dileia said quietly.

If you need someone to talk to or I don’t know, just know you’re not alone here.

Jordan looked at her with those careful guarded eyes.

Thank you.

But I am alone.

We all are in the end.

The response was delivered without self-pity, simply as a statement of fact.

Dileia watched Jordan continue down the hall and felt a profound sadness that had nothing to do with her own circumstances and everything to do with recognizing suffering she was powerless to relieve.

By late November, Thomas had begun to withdraw, even from Jordan.

The nightly visits to the third floor room became less frequent.

He would spend long hours in his study instead, drinking whiskey and staring at the locked journal he no longer wrote in, as if the answers to questions he couldn’t articulate might somehow appear in its pages.

Catherine filled the void.

She spent entire days in Jordan’s room now, barely eating, barely sleeping, locked into an obsession that had consumed whatever else had once existed in her life.

She would talk to Jordan for hours, rambling monologues about her childhood in Richmond, her marriage, the baby she had lost.

Her sense that she had somehow failed at the fundamental task of being a woman.

Jordan listened with that same careful attention, responding when required, offering no judgment or comfort.

Sometimes Catherine would fall asleep in the chair by the window, and Jordan would cover her with a blanket and sit perfectly still until she woke hours later, disoriented and confused about where she was.

“Why do you stay?” Catherine asked one afternoon.

“You could run.

” Samuel and Isaac tried.

You’re smart enough to have a better chance than they did.

And go where, mistress.

I was born marked as different.

Everywhere I go, people see that difference and want to understand it, to examine it, to possess it.

At least here, I know what to expect.

That’s terrible, Catherine whispered.

Yes, mistress, it is.

It was during one of these long afternoons that Catherine finally articulated the question that had been growing in her mind for months.

Do you hate us, Thomas and me? Jordan was silent for a long moment.

When the slave finally spoke, it was with careful consideration, as if weighing each word.

Hate requires a kind of freedom I don’t have, mistress, to hate you, I would have to believe I deserved something different, that I had a right to be treated as fully human.

But I was taught from childhood that I don’t have that right.

That my unusual nature makes me something less than human.

Something to be studied and displayed.

So no.

I don’t hate you.

I don’t.

I simply endure you the same way I’ve endured everyone before you and will endure everyone who comes after.

Catherine began to cry.

Then deep, wrenching sobs that seem to come from somewhere fundamental.

Jordan sat motionless, offering no comfort, simply bearing witness to the mistress’s breakdown with that same careful neutrality.

When Catherine finally composed herself, her face was blotchy and her eyes were red.

I think we’re destroying ourselves, she said.

Thomas and I, this obsession with you, it’s like a disease eating us from the inside.

Yes, mistress.

And you’re just watching it happen.

What else can I do? Catherine had no answer.

The crisis that had been building for months finally came to a head on December 15th when Dr.

Edmund Carile arrived at Belmont Estate.

Dr.

Carile was a physician from Richmond, an old friend of Thomas’s father, who had written to Thomas weeks earlier, offering condolences on some business difficulties he’d heard about through mutual acquaintances.

Thomas, in a moment of weakness and desperate need to validate his obsession, had written back mentioning his acquisition of a medical curiosity and inviting Carlile to visit and offer his professional opinion.

He arrived in the afternoon, a rotund man in his 60s, with white mutton chops and the confident bearing of someone who had spent 40 years being deferred to as an authority.

Thomas greeted him with an enthusiasm that seemed forced, almost manic.

Catherine remained upstairs, claiming a headache.

They dined together that evening, and Thomas spoke with barely controlled excitement about Jordan, carefully at first, using medical terminology and discussing the rarity of true hermaphroditism, but gradually becoming more animated, more revealing of his fascination.

Carlile listened with professional interest that slowly shifted to something more troubled as the evening progressed.

I would be very interested to examine this slave, Carile said finally.

If you’re amenable, of course.

That’s why I invited you.

I value your expertise, your professional assessment of the situation.

Something in Thomas’s voice made Carile pause.

The situation? Thomas seemed to catch himself.

The medical condition, I mean, the documentation from the previous owner was extensive, but I would appreciate a second opinion from someone of your standing.

After dinner, Thomas brought Carlile to Jordan’s room.

Catherine was already there, sitting in her chair by the window, looking like a wraith in her dark dress.

Jordan stood by the door, hands clasped, face carefully neutral.

This is Jordan,” Thomas said, his voice taking on that clinical tone he used when trying to maintain distance from his obsession.

The slave I mentioned in my letter.

Carile approached Jordan with professional detachment, asking questions about age, general health, the slave’s history before coming to Belmont.

Jordan answered in that careful rehearsed manner, providing information without inflection or emotion.

May I conduct a brief physical examination? Carile asked.

Nothing invasive, simply an external observation to assess the condition Mr.

Rutled described.

Jordan glanced at Thomas, who nodded.

Of course, doctor.

Jordan is accustomed to medical examination.

What followed was a professional, respectful assessment that stood in stark contrast to what had been happening in that room for the past 4 months.

Carlilele examined Jordan’s face, hands, asked the slave to turn slowly, made a few notations in a small book he carried.

His examination was thorough but dignified, treating Jordan as a patient rather than a specimen.

When he was finished, his expression had shifted from clinical interest to something more complex, a mixture of professional curiosity and deeply personal concern.

Remarkable, he said quietly.

A genuine case of hermaphroditism.

Quite rare indeed.

He looked at Thomas, then at Catherine, sitting motionless in her chair.

Might I speak with you privately, Mr.

Rutled? They retired to Thomas’s study, leaving Catherine and Jordan alone upstairs.

Carile accepted a brandy and stood by the fire, choosing his words with obvious care.

Thomas, I’ve known your family for many years.

I respected your father despite his difficulties, which is why I must speak frankly now as a friend and as a physician.

Thomas felt his stomach tighten with dread.

What is it? That slave upstairs is indeed a genuine hermaphrodite.

The condition is as rare as you suggested.

From a strictly medical standpoint, it would be of considerable interest to researchers.

Carile paused, his eyes grave.

But Thomas, what concerns me is not the slave’s condition.

What concerns me is the atmosphere in that room.

The way you and your wife look at that person, the tension, the obsession I sense beneath your words.

Thomas felt his face flush.

I don’t know what you’re suggesting.

I’m suggesting that you’ve become dangerously fixated on this slave in a way that goes far beyond medical or scientific interest.

Your plantation is failing.

I could see that on my way up the drive.

Your wife looks like she hasn’t slept properly in months.

You yourself appear.

He paused, searching for the right word.

Consumed.

This isn’t healthy, Thomas.

Whatever is happening here needs to stop before it destroys you.

Jordan is my property, Thomas said, his voice sharper than he intended.

How I choose to manage my property is my concern.

There are moral lines, Thomas, even in the treatment of slaves.

and I fear you’ve crossed several of them.

” The conversation deteriorated from there.

Thomas became defensive, then angry.

Carile remained firm but compassionate, trying to make Thomas see what was happening to him and his wife, but Thomas couldn’t or wouldn’t hear it.

The obsession had its hooks too deep.

Carile left the next morning, troubled and convinced that something terrible was unfolding at Belmont Estate.

He considered writing to mutual friends, perhaps even to the county authorities.

But what would he report? That a man was too interested in a slave he owned.

That wasn’t illegal.

Wasn’t even particularly unusual in Virginia in 1851.

So Carile did nothing, and the opportunity to intervene passed.

After his departure, Thomas and Catherine didn’t speak about the visit, but something had shifted.

Carile’s words had forced them to confront, however briefly, what they were doing.

And that confrontation didn’t lead to change.

It led to desperation, to a doubling down on the obsession, as if by consuming themselves entirely in it.

They could somehow escape the guilt that was beginning to poison everything.

January 1852 brought heavy snows that isolated Belmont estate from the outside world for nearly 3 weeks.

The tobacco fields laid dormant under white blankets.

The slaves huddled in their quarters around smoky fires.

And inside the main house, Thomas and Catherine descended further into a darkness that neither could any longer deny or escape.

The isolation seemed to accelerate everything.

With no social obligations to maintain, no appearances to keep up, they abandoned whatever restraint had remained.

Thomas stopped even pretending to manage the plantation.

Catherine stopped leaving the third floor entirely.

And Jordan, Jordan simply endured, as always, existing in that strange liinal space between person and object, between the living and those who merely survived.

But something had changed in Jordan, too.

The slave had begun to speak more often, not with defiance exactly, but with a kind of quiet observation that made Thomas and Catherine increasingly uncomfortable.

Jordan had learned that speaking could create cracks in their certainty, could introduce doubt into their carefully constructed rationalizations.

“You’re hurting each other now, not just me,” Jordan said one evening after Catherine had left the room in tears following an argument with Thomas.

The obsession is eating you both from the inside.

Thomas, exhausted and disheveled, looked at the slave with something close to hatred.

What do you want from me? Some acknowledgement that I’ve wronged you? Your property, Jordan.

You exist to serve whatever purpose I determine? Is that what you tell yourself, master? Because from where I stand, it seems like I’m the only free person in this room.

You and the mistress are enslaved to your desires, to your need to possess something you can never truly have.

I submit to you because the law gives me no choice.

But you submit to your obsessions because you’ve lost the ability to choose anything else.

The words struck deeper than any physical blow could have.

Thomas raised his hand as if to strike, then let it fall.

What punishment could he inflict that would restore the power dynamic that had already collapsed? What threat could he make that would give him back the control he had lost? He left the room without another word.

February brought a thor but no relief from the tension inside Belmont Estate.

The enslaved people in the quarters whispered constantly now, their speculation growing darker and more accurate.

Several had begun trying to arrange escapes, knowing that something was terribly wrong and wanting to be far away when whatever was building finally exploded.

Harriet refused to bring food to the third floor anymore, forcing Catherine to fetch meals herself or go hungry.

Two more field hands attempted to run and were caught, but Thomas barely seemed to notice when they were returned.

The overseer handled the punishment without consulting him, increasingly taking control of day-to-day operations as the master retreated further into his obsession.

Catherine had begun to waste away visibly.

She ate almost nothing, slept only in brief, fitful intervals, spent every waking moment either in Jordan’s room or pacing the halls like a ghost.

Her friends from the charitable societies, concerned by her long absence, sent notes that went unanswered.

The minister came again and was turned away at the door.

“I see myself in you,” Catherine told Jordan one afternoon, her voice barely above a whisper.

“Neither one thing nor another, neither fully alive nor fully dead, trapped in some impossible space between.

” “No, mistress,” Jordan replied quietly.

You see what you want to see.

I’m just a person.

Born different, yes, but still just a person.

It’s you and the master who made me into something else.

You turned me into a symbol of your own confusion, your own sense of being lost.

Catherine’s hands trembled as she wrapped her arms around herself.

But you are lost, too.

We’re all lost here, perhaps.

But I was lost long before I came to Belmont Estate.

You chose this.

That’s the difference.

The household staff noticed the change in the mistress.

Dileia, passing Catherine in the hallway one morning, was shocked by what she saw.

The woman had become skeletal, her eyes sunken and wild, her hair hanging loose and unwashed.

She moved like someone already half dead, stumbling from one moment to the next without any sense of purpose or direction.

Thomas was little better.

He had stopped shaving, stopped changing his clothes regularly.

He would wander the house at odd hours, muttering to himself, sometimes standing outside Jordan’s door for long minutes without ever knocking.

The servants learned to avoid him, to make themselves invisible when he passed, because there was something unpredictable in his manner now, something that suggested he might shatter at the slightest provocation.

The whispers in the slave quarters had evolved from speculation to certainty.

Something terrible was going to happen.

Everyone could feel it.

that sense of impending disaster that hangs in the air before a storm breaks.

People began making preparations, hiding small caches of food, mending shoes in anticipation of running, having quiet conversations about which direction offered the best chance of reaching free territory.

It was Harriet who finally tried to intervene.

Driven by a sense that if someone didn’t do something, blood would be spilled.

She found Thomas in his study late one afternoon, staring at nothing, a glass of whiskey forgotten in his hand.

She stood in the doorway, gathering her courage, knowing that what she was about to do could get her sold away or worse.

“Master Rutled,” she said quietly.

“I need to speak plain with you.

” He looked up slowly as if coming back from somewhere very far away.

What is it, Harriet? This thing you and the mistress got going with that slave, Jordan.

It ain’t right, sir.

And it’s killing all three of you.

I can see it happening day by day.

You got to let that child go.

Sell Jordan away.

Send that slave somewhere else before this whole house comes crashing down.

Thomas stared at her for a long moment.

She braced herself for his anger, for punishment, for the violence that masters could inflict on slaves who spoke out of turn.

But instead, something crumbled in his expression, and for just a moment she saw the truth written plainly on his face.

He knew she was right, knew exactly what was happening, and was powerless to stop it.

“Get out, Harriet,” he said finally, his voice barely audible.

Just get out, she left, her heart pounding, knowing she had tried and failed.

If this story is giving you chills, share this video with a friend who loves dark mysteries.

Hit that like button to support our content, and don’t forget to subscribe to never miss stories like this.

Let’s discover together what happens next because the horror in Belmont Estate is about to reach its terrible conclusion.

The breaking point came on February 14th, 1852.

The day started like any other in that household of slow dissolution.

Thomas rose late, disheveled and holloweyed.

Catherine remained upstairs, having not left the third floor in 3 days.

Jordan moved through the routine of survival, fetching water, managing the small tasks that maintained the illusion of normaly.

But something was different.

Those who knew Catherine well, and the enslaved women who had served her for years knew her better than anyone, could see that she had reached some kind of breaking point.

There was a strange calm about her that morning, a stillness that was more frightening than her usual agitation.

Dileia noticed it when she passed the mistress in the hallway.

Catherine’s eyes, usually restless and fevered, had taken on a glassy quality, as if she were looking at something very far away.

She moved with deliberate slowness, like someone performing a rehearsed ritual.

When Dia offered to bring her tea, Catherine simply shook her head and continued up the stairs without speaking.

Harriet noticed it, too, and the feeling of dread that had been building in her chest for months suddenly intensified.

She found herself praying quietly under her breath as she worked in the kitchen, that whatever was coming would pass quickly and leave the innocent unharmed.

By evening, a cold rain had begun to fall, drumming against the windows and turning the world outside into a blur of gray water.

The temperature dropped sharply and the wind howled around the corners of the house, making the old structure creek and groan.

It felt like the kind of night when terrible things happened, when the normal rules of the world suspended themselves.

Thomas sat in his study, staring at the fire, drinking whiskey with mechanical regularity.

He had stopped trying to understand what had happened to his life, had stopped trying to rationalize or justify.

He simply existed in a fog of alcohol and exhaustion, waiting for something he couldn’t name.

Upstairs, Catherine sat in Jordan’s room, watching the slave with an intensity that had become familiar over the months, but had now taken on a desperate edge.

The lamp flickered, casting shadows that danced across the walls.

Outside, the rain intensified, and somewhere in the distance, thunder rumbled.

“I can’t do this anymore,” she said suddenly, her voice cracking.

“I can’t wake up one more day in this house, in this life, knowing what we’ve become.

” Jordan, sitting on the narrow bed, looked at her with those careful, guarded eyes.

“Then leave, mistress.

Take what money you can and go somewhere far away.

Start over.

Start over.

Catherine laughed.

A broken sound with no humor in it.

How do I start over when I carry this with me? When every time I close my eyes, I see what we’ve done, what we’ve become.

You don’t understand.

There’s no starting over from this.

There’s only ending it.

Something in her tone made Jordan sit up straighter, suddenly alert.

Mistress, what do you mean? Catherine stood abruptly, pacing to the window and back, her movements jerky and uncoordinated.

Rain lashed against the glass and lightning briefly illuminated her face.

Gaunt, haunted, already half dead.

I thought understanding would bring freedom.

I thought if I could just comprehend what you are, if I could solve the mystery of your existence, it would somehow solve the mystery of my own emptiness.

But it’s only made everything worse.

You were right.

You’re just a person and we turned you into a symbol of our own brokenness.

And I can’t live with what that makes us.

Catherine.

Jordan used the mistress’s name for the first time, abandoning the careful formality of slavery.

Whatever you’re thinking, stop.

Talk to someone.

The minister, a doctor, anyone who can help you.

Help me.

Catherine’s voice rose, taking on a hysterical edge.

Help me what? Forget what we’ve done to you.

Pretend we’re decent people.

We’re not.

We’re monsters who used another human being to fill the emptiness inside us, and it didn’t work.

And now I’m hollow all the way through.

She moved to the dresser with sudden purpose, opened a drawer, and pulled out something that gleamed dullly in the lamplight.

A pistol.

One of Thomas’s father’s dueling pistols that she must have taken from the study days ago, hidden here, waiting for this moment.

Jordan stood slowly, hands raised in a gesture of peace.

Mistress, please put that down.

Why? Catherine turned to face Jordan, the gun held loosely in her shaking hand.

So we can keep doing this.

Keep destroying each other day by day.

I’m tired, Jordan.

I’m so tired of being alive.

So tired of feeling everything and nothing at the same time.

Thunder cracked directly overhead, so loud it seemed to shake the house.

The lamp flickered wildly, nearly going out, then steadied again.

In that moment of darkness, Catherine’s face looked like a skull, all sharp angles and hollow eyes.

The door burst open.

Thomas stood in the doorway, alerted by Catherine’s raised voice, water dripping from his coat.

He had been standing outside in the rain, she realized, probably for hours.

His eyes immediately fixed on the pistol in his wife’s hand, and whatever fog of alcohol and despair he’d been living in suddenly cleared.

“Catherine, what are you doing?” She turned to look at him, tears streaming down her wasted face, mixing with the lamplight to make her skin seem to glow.

“I’m ending it, Thomas.

I’m stopping this before it goes any further.

Before we destroy anything else, anyone else? Give me the gun.

Thomas moved into the room, hand outstretched, his voice taking on a careful, gentle quality she hadn’t heard in months.

Please, Catherine, whatever your feeling, we can we can what? She laughed that broken laugh again.

Fix this.

Make it right.

There’s no making this right, Thomas.

We destroyed this person.

She gestured toward Jordan with the gun, the barrel wavering wildly.

We destroyed each other.

We destroyed everything we touched because we were too broken to do anything else.

Don’t you see? We’re poison.

Everything we touch turns sick and dies.

Jordan spoke then, voice calm despite the weapon pointed in their direction.

Catherine, you’re not a monster.

You’re a person who made terrible choices.

Yes, but you can still choose differently.

You can still walk away from this.

Both of you can.

It’s not too late to It is too late.

The gun shook violently in Catherine’s grip.

It’s been too late since the day Thomas brought you here.

Maybe it was too late years before that.

When I married a man I didn’t love for money I didn’t need.

When I tried to be someone I wasn’t.

When I lost the baby and realized I’d never be the person everyone expected me to be.

Don’t you understand? I can’t keep living like this.

Every breath is agony.

Every moment I’m awake, I see what we are, what we’ve done, and I can’t bear it anymore.

Thomas took another step forward, his face pale, his hand still extended.

Catherine, please think about what you’re doing.

Think about I have thought about it, she screamed.

I’ve thought about nothing else for weeks.

This is the only thing that makes sense anymore.

the only choice I have left that’s really mine.

But Catherine had stopped listening to her own words.

Her face had taken on a strange serenity, as if she’d finally made peace with the decision that had been building for months, maybe years.

The shaking in her hands stopped.

The wild look in her eyes calmed to something almost peaceful.

“I’m sorry,” she whispered, looking directly at Jordan.

“For all of it.

For everything we did to you.

for what we turned you into, for using you to avoid looking at ourselves.

Then, with movements that seem to happen in slow motion, she turned the gun away from Jordan and toward herself, pressing the barrel under her chin.

No.

Thomas lunged forward, his fingers grasping for the weapon, but he was too slow, too late, too broken himself to prevent what came next.

The sound of the gunshot was deafening in the small room, seeming to compress the air itself and make the lamplight flare impossibly bright for one frozen instant.

Catherine’s body fell backward, striking the floor with a terrible finality.

Blood began to spread across the floorboards, dark and gleaming in the lamplight, pooling around her head like a grotesque halo.

Thomas dropped to his knees beside her, making sounds that were barely human.

raw grief and horror that transcended language, animal sounds of pain that no words could express.

His hands hovered over her body, wanting to touch her, to hold her, but afraid of causing more damage, as if anything he did now could possibly matter.

Jordan remained standing by the window, perfectly still, face showing an expression that might have been pity or might have been relief, or might have been nothing at all.

Outside, the rain continued to fall and thunder rolled across the dark sky and the world went on as if nothing had happened.

Downstairs, the servants had heard the gunshot.

Harriet stood frozen in the kitchen, her worst fears confirmed, her prayers unanswered.

Dileia sat in her room with her hands over her mouth, fighting the urge to scream.

The other slaves gathered in the hallway, whispering urgently, trying to decide what to do, whether to run or stay, whether this was the beginning of something worse or the end of the nightmare they’d been living through.

Catherine lived for 17 more hours.

The bullet had caused terrible damage, but hadn’t killed her immediately, leaving her suspended between life and death in a state beyond consciousness or pain.

She lay in her bed while Thomas sat beside her, holding her hand, whispering apologies she couldn’t hear, begging forgiveness from someone who was already gone, even though her heart still beat.

Jordan brought water and clean cloths, tending to both master and dying mistress with quiet efficiency, saying nothing, offering no comfort or judgment.

The slave simply performed the tasks that needed performing, existing in that familiar space of service that required no thought, no feeling, no engagement with the horror unfolding.

The household doctor came near midnight, summoned by one of the servants.

He examined Catherine, shook his head gravely, and told Thomas there was nothing to be done but wait.

The damage was too severe, too deep in the brain.

It was a miracle she had survived this long.

When Thomas asked if she was suffering, the doctor assured him that no, she was beyond all suffering now, feeling nothing, aware of nothing, already more absent than present.

Thomas sent the doctor away and returned to Catherine’s bedside, maintaining his vigil through the long dark hours.

He spoke to her, sometimes rambling confessions of guilt and grief and love that he had never expressed when she could hear them.

He told her about his own emptiness, his own brokenness, how he had thought she could fill the void inside him, and had been devastated to discover she was just as hollow as he was.

He told her he was sorry for bringing Jordan into their lives, sorry for starting them down a path that could only end in destruction.

But mostly he sat in silence, watching the rise and fall of her chest become slower and shallower with each passing hour.

As dawn light began to filter through the windows, gray and cold, matching the rain that still fell outside, Catherine’s breathing changed one final time.

It became labored, rattling, the sound of a body giving up its last hold on life.

Thomas leaned close, tears falling onto her pale face, his hand gripping hers with desperate strength.

“I’m sorry,” he whispered one last time.

“For everything! For failing you? for all of it.

Her eyes opened briefly, clouded and unfocused, perhaps seeing him one last time, perhaps seeing nothing at all.

Her lips moved, forming words without sound, words he would never know, messages that died undelivered.

Then she was gone.

The terrible rattling breath stopped.

Her hand went limp in his.

The slight warmth that had remained in her skin began to fade, replaced by the cold that claimed all the dead.

Thomas sat with her body for hours after, unable to move, unable to think, unable to feel anything except a vast emptiness that seemed to swallow everything.

Not just Catherine, not just himself, but the entire world, the entire universe, everything collapsing into a void that had no bottom and no end.

Finally, Jordan spoke from the doorway, voice quiet and neutral.

Master, we need to call for help.

The servants, the doctor, someone needs to be told.

Thomas looked up at the slave, his face ravaged by grief and guilt, his eyes red from crying, his hands still clutching his dead wife’s cooling fingers.

And in that moment, unable to bear the weight of his own culpability, he lashed out at the only target available.

“This is your fault,” he said, his voice flat and dead.

“You did this to us.

You destroyed everything.

Jordan met his gaze steadily, neither flinching nor arguing, simply accepting the accusation with the same careful neutrality that had characterized every interaction.

No, master, you did this to yourselves.

I was just here.

The words hung in the air between them, simple, undeniable, devastating in their truth.

Thomas had no response.

He turned back to Catherine’s body and said nothing more.

The aftermath unfolded with grim inevitability, each step following logically from what had come before, like a mathematical proof leading to an inescapable conclusion.

Thomas claimed Catherine’s death was an accident, a tragic misfortune that occurred while she was handling one of his father’s old pistols, not understanding it was loaded.

The local magistrate, a man who had known Thomas since childhood and who understood the complications that suicide created for a respectable family, accepted this explanation with visible relief.

He conducted a brief investigation that asked no difficult questions and reached the conclusion everyone wanted.

Suicide was shameful, legally complicated, problematic for the church and for inheritance.

Accident was simpler for everyone involved.

The funeral was held 3 days later at Christ Church in Farmville, well attended by neighboring planters and their wives who came to pay their respects to one of their own.

They stood in the cold rain and spoke in hushed sympathetic tones about the tragedy of a young woman taken before her time.

They remarked on how devastated Thomas appeared, how he had aged years in recent months, how grief had hollowed him out until he seemed barely substantial.

They offered their condolences with genuine feeling.

These people who had known the rutages for generations who had no idea what had really happened behind the closed doors of Belmont estate.

None of them knew the truth or if some suspected if they had noticed Thomas’s increasing withdrawal from society.

Catherine’s strange behavior, the whispered rumors that had begun circulating among the enslaved community, they had the good sense not to speak of it.

Some questions were better left unasked in Virginia in 1852.

Some answers were too disturbing to acknowledge, but the enslaved community knew.

They always knew.

In the quarters at Belmont and on neighboring plantations, in whispered conversations after the masters had gone to bed, the truth circulated through the invisible network that connected Virginia’s enslaved population.

The story of what had happened at Belmont Estate spread and grew in the telling, acquiring mythic dimensions as it passed from mouth to mouth, becoming a cautionary tale about the corrupting nature of absolute power.

And what happened when masters treated enslaved people not as human beings but as objects to satisfy their desires? They spoke of Jordan, the strange slave, neither man nor woman, who had somehow driven the rutages to destruction simply by existing.

Some versions of the story suggested Jordan had special powers, some kind of conjure or hudoo that made masters lose their minds.

Others claimed Jordan had been so beautiful, so impossibly alluring that even good Christian people couldn’t resist falling into sin.

Still others whispered that Jordan hadn’t done anything at all except hold up a mirror to the Rutled’s souls, and they had destroyed themselves when they couldn’t bear what they saw reflected there.

The truth, as always, was more complicated and more mundane than legend allowed.

But the legend served its purpose, reminding the enslaved that their masters were not invulnerable, that obsession and guilt could destroy even the most powerful, that sometimes survival itself was a kind of victory.

Within a week of Catherine’s funeral, Thomas made arrangements to sell Belmont Estate.

He met with potential buyers, negotiated terms, accepted the first reasonable offer despite it being well below the property’s actual value.

He wanted only to be rid of the place as quickly as possible to put distance between himself and the sight of his destruction.

Before the sale was finalized, he did three things.

First, he ordered the third floor room where Catherine had died sealed and locked.

He had workers remove all the furniture, scrubbed the blood stains from the floorboards, though the stains never quite disappeared, no matter how hard they scrubbed.

Then he had the door locked and the key thrown into the well with stipulations written into the sales contract that the room remain sealed in perpetuity.

The buyer, a merchant from Petersburg, thought it an eccentric request, but agreed readily enough.

What did he care about one locked room in a house with 20 others? Second, Thomas systematically destroyed every document related to Jordan.

bills of sale, medical records, personal journals, correspondence with Dr.

Carile.

He built a fire in his study fireplace and fed the papers into it one by one, watching years of documentation turned to ash.

He burned Catherine’s diary, too.

Though he never read it first, he couldn’t bear to see his own actions reflected through her eyes, to understand how she had experienced what they had done.

Third, he sold most of the enslaved workers along with the property, dispersing them to different buyers across the county.

Families were separated, communities broken apart, lives disrupted once again to serve the convenience of those who owned them.

Thomas felt a distant guilt about this, understanding on some level that he was inflicting fresh trauma on people who had already endured so much.

But guilt changed nothing.

He needed money to start over.

and slaves were property to be liquidated like any other asset.

But he kept Jordan.

When asked why, he had no good answer.

Perhaps it was because Jordan was the only other person who truly understood what had happened, the only witness to his complete degradation.

Perhaps it was because some part of him still felt that strange fascination, that need to possess what he couldn’t understand.

Or perhaps it was simply because he couldn’t imagine Jordan belonging to anyone else, being subjected to another master’s curiosity or cruelty.

He moved to a small house in Lynchberg with just three slaves, Jordan and two elderly servants too old to fetch good prices at auction.

It was a modest residence on a quiet street, nothing like the grandeur of Belmont.

Thomas lived there like a hermit, rarely venturing out except for necessary errands, declining all social invitations, withdrawing completely from the world of Virginia’s Planter Society that had once defined his entire existence.

His neighbors occasionally saw him walking alone in the early morning hours, moving with the slow shuffling gate of a much older man, his shoulders hunched as if carrying an invisible weight.

He spoke to no one, made no friends, participated in no community activities.

He simply existed, going through the motions of living without any apparent purpose or pleasure.

Jordan lived in a small room on the second floor of the house, still legally Thomas’s property, but no longer subject to the obsessive attention that had characterized their relationship at Belmont.

They barely spoke to each other.

When they did interact, it was with formal politeness.

Thomas giving simple orders about household tasks, Jordan obeying with quiet efficiency.

The terrible intimacy they had shared at Belmont was gone, replaced by a vast distance that neither could bridge even if they had wanted to.

The relationship had transformed into something almost stranger than what had come before.

They were master and slave in the eyes of the law.

But in practice, they were more like two ghosts haunting the same house, moving past each other without truly connecting, bound together by shared history neither could escape, but both desperately wanted to forget.

Sometimes late at night when he couldn’t sleep, Thomas would stand outside Jordan’s door with his hand raised to knock, wanting something, understanding perhaps, absolution, some acknowledgement that what had happened between them had been real, had mattered, had meant something beyond mere exploitation and destruction.

But he never knocked.

He would stand there for long minutes, his hand trembling in the air, then turn away and return to his own room without making a sound.

Jordan, lying awake on the other side of that door, knew he was there, could hear his breathing, sense his presence, feel the weight of his unspoken need.

But Jordan never opened the door, never offered the comfort or confrontation Thomas might have been seeking.

There was nothing to say that hadn’t already been said, nothing to offer that could change what had happened or make it mean something other than what it was.

The month passed slowly in that house of ghosts and silence.

Thomas aged rapidly, his hair going gray, his face gaunt, his eyes taking on the hollow look of someone who had stopped seeing any purpose in continuing to exist.

He drank, though not to excess, just enough to blur the edges of memory to make sleep possible on the nights when guilt and grief threatened to overwhelm him entirely.

Thomas Rutled died in his sleep on the morning of November 3rd, 1852, 9 months after Catherine’s death.

The physician who was called to examine the body found no obvious cause of death, no disease, no injury, no sign of poison or violence.

His heart had simply stopped beating, as if he had decided during the night that living required more effort than he could muster, and his body had obligingly complied with that decision.

Sometimes, the physician noted in his report, with the careful detachment of professional observation, “A man can die of a broken spirit as surely as from a broken bone.

The will to live is a mysterious thing, and when it departs, the body often follows soon after.

I believe that is what happened here.

Jordan was sold at auction along with the other assets of Thomas’s small estate.

The house, the furniture, the two elderly servants.

The slave went for $412, a fraction of what Thomas had originally paid, because by then rumors about Jordan’s unusual nature had spread through the local community, and buyers were suspicious of anything connected to the Rutledge tragedy.

The man who purchased Jordan was a farmer from Appamatics County who needed household help and didn’t put much stock in what he dismissed as superstitious gossip.

What became of Jordan after that is unknown.

The historical record goes silent as it does for so many enslaved people whose lives and deaths were considered too insignificant to document.

There are no further bills of sale, no estate inventories, no court records that mention a slave matching Jordan’s description.

The person simply vanished into the vast darkness of the American slave system, becoming one of millions whose stories were never recorded, whose suffering left no official trace beyond whispered legends and sealed documents.

Perhaps Jordan eventually found freedom somehow through escape to the north, through the chaos of the approaching civil war, through eventual emancipation when it finally came.

Perhaps Jordan lived a long life under a new name in a place where no one knew the story of Belmont Estate, where being different was no longer a curiosity to be examined, but simply one variation among many in the infinite diversity of human existence.

Perhaps Jordan found some measure of peace, some way to heal from the violation suffered at the hands of Thomas and Katherine Rutled.

Or perhaps not.

Perhaps Jordan lived the rest of a short life, being passed from master to master, examined and exploited by each in turn, dying young and forgotten in some unmarked grave.

History is full of people who suffered without redemption, without justice, without healing, without even the consolation of being remembered.

We want to believe that Jordan survived, that somehow this person who endured so much eventually found freedom and peace.

But we simply don’t know.

and the silence of the historical record may be answer enough.

Belmont estate stood empty for three years before being purchased by the merchant from Petersburg who had bought it from Thomas.

The new owner moved in with his family, determined to restore the property to its former prosperity.

But within weeks, strange reports began circulating.

The sealed room on the third floor disturbed everyone who passed it in the hallway.

There was a cold spot by the door that never warmed, even in the heat of summer, and sometimes people reported hearing sounds from inside, though the room had been empty and locked for years.

Against the stipulations of the original sale, the new owner eventually had the room opened, curiosity overcoming his agreement to leave it sealed.

Inside, workers found evidence of what had happened there.

Dark stains on the floorboards that no amount of scrubbing had removed, marks on the walls where furniture had stood, an atmosphere so oppressive that the men who entered refused to stay longer than absolutely necessary.

They stripped the room entirely, replaced the floorboards, repainted the walls.

But the new owner’s family reported they could never quite shake the feeling that something terrible had happened in that space.

some echo of violence and despair that lingered despite all efforts to erase it.

The estate changed hands four more times over the next decade, each owner staying only briefly before selling at a loss and moving on.

Stories began to circulate about the property, about strange sounds in the night, about shadows that moved in ways shadows shouldn’t move, about a presence that filled certain rooms with inexplicable dread.

Each successive owner tried to dismiss these stories as superstitious nonsense, the kind of tales that accumulate around any old house.

But each eventually sold the property for less than they’d paid, and each quietly warned the next buyer that something was wrong with the place, though they could never quite articulate what.

By 1865, during the chaos of the Civil War’s final months when Union and Confederate forces swept back and forth across Virginia, the main house burned under circumstances that were never adequately explained.

Some said it was Union soldiers passing through the area.

Others claimed it was local residents who had grown tired of the house’s sinister reputation and decided to end it once and for all.

Still others whispered that the house had simply destroyed itself, that the weight of what had happened there had become too much for brick and timber to bear, and the fire had started from within.

Only the foundation and a few outbuildings survived the blaze.

These remained standing for another two decades, slowly deteriorating before being finally swallowed by forest and undergrowth as nature reclaimed land that humans had abandoned.

Today, nothing remains of Belmont Estate except a few crumbling brick foundations barely visible beneath decades of leaf litter and encroaching vegetation.

The land is privately owned, posted with no trespassing signs that are carefully maintained, though no one seems to know who maintains them or why.

Local historians acknowledge that a plantation once stood there, that the Rutled family lived and died on that property.

But details about the estate’s history are notably absent from county records, as if someone long ago made a systematic effort to erase the place from official memory.

the sealed court documents related to the Rutled incident.

News

Ilhan Omar ‘PLANS TO FLEE’…. as FBI Questions $30 MILLION NET WORTH

So, while Bavino is cracking down in Minnesota, House Republicans turning the heat up on Ilhan Omar. They want to…

FBI & ICE Raid Walz & Mayor’s Properties In Minnesota LINKED To Somali Fentanyl Network

IC and the FBI move on Minnesota, touching the offices of Governor Tim Walls and the state’s biggest mayors as…

FBI RAIDS Massive LA Taxi Empire – You Won’t Believe What They Found Inside!

On a Tuesday morning, the dispatch radios in hundreds of Los Angeles taxi cabs suddenly stopped playing route assignments. Instead,…

Brandon Frugal Finally Revealed What Forced Production to Halt in Season 7 of Skinwalker Ranch….

The Secret of Skinwalker Ranch became History Channel’s biggest hit. Six successful seasons documenting the unknown with real science and…

1 MINUTE AGO: What FBI Found In Hulk Hogan’s Mansion Will Leave You Shocked….

The FBI didn’t plan to walk into a media firestorm, but the moment agents stepped into Hulk Hogan’s Clearwater mansion,…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage… It started like any other evening…

End of content

No more pages to load