The Master Raised Him as a Son Since Age 3. What He Did to the Boy at Age 17 Shocked the South

Get in the bed, Jacob.

Thomas Ashford’s voice was soft like it always was.

But this time there was something different.

Jacob, 17 years old, stood in that Charleston hotel room staring at his master, and he felt something was wrong.

But sir, I your bed.

Thomas laughed, that familiar fatherly chuckle.

Now, let me take you back to 1831 to the day when Jacob was only 3 years old.

Spring in Buffett County, South Carolina, arrived with suffocating humidity and the smell of pluff mud from the marshes.

The Ashford Plantation, Riverside Manor, sprawled across 1,200 acres of prime cotton and riceand.

It wasn’t the largest plantation in the county, but it was prosperous enough.

Thomas Ashford, 31 years old in 1831, had inherited it from his father 2 years prior.

He was known throughout the county as a fair man.

Not kind in the way that threatened the social order, but fair.

He paid his debts on time.

He attended church every Sunday.

He spoke softly and smiled often.

When he walked through town, people tipped their hats and called him a good Christian man.

He had married Margaret Sullivan in 1829, a practical union that brought additional land and the Sullivan name, which carried weight in Charleston society.

Margaret was a quiet woman, 23 when they wed, with pale skin that burned easily in the southern sun and a tendency to stay indoors with her embroidery.

She had given Thomas two sons, William in 1830 and Henry in 1832.

The boys would be raised properly, educated in Charleston, groomed to take over the plantation when their time came.

Thomas Ashford was by all accounts exactly what a southern gentleman should be.

But in March of 1831, something happened that would set in motion events no one could have predicted.

Thomas was riding through Charleston on business when he saw the child.

A small boy, no more than 3 years old, sitting in the gutter outside a tavern.

The boy was filthy, his clothes were rags, and he was crying silently, tears making clean tracks down his dirty face.

Thomas stopped his horse.

He dismounted.

He walked over to the child.

Where’s your mother, boy? The child looked up at him with enormous dark eyes and said nothing.

Thomas asked the tavern owner about the boy.

The man shrugged.

died 2 days ago.

Fever.

Boy’s been sitting there since.

No one knows who the father was.

Probably get taken to the poor house tomorrow or just die in the street.

Happens all the time.

Thomas Ashford looked down at the child and something in him, something he would later describe as Christian charity, made a decision.

I’ll take him.

The tavern owner laughed.

You want to buy a bastard child? He’s not even for sale, mister.

He’s just trash.

I’ll give you $5.

$5 was more money than the tavern owner made in a month.

He took it.

Thomas lifted the boy onto his horse.

The child was so light, like he weighed nothing at all.

What’s your name, boy? The child whispered something that sounded like Jacob.

Jacob? That’s a good biblical name.

You’re going to come home with me, Jacob.

You’re going to have food in a bed, and you’re going to work hard.

Do you understand? Jacob nodded.

That night, Thomas brought Jacob to Riverside Manor.

Margaret was not pleased.

You brought home a white child from the gutter.

Thomas, what will people think? They’ll think I’m a charitable Christian man.

Besides, he’ll work.

I’ll train him up properly.

He’ll be useful.

And so, Jacob became part of the Ashford household, not as a son, never that, but not quite as a slave either.

He existed in a strange in between space.

He slept in a small room off the kitchen.

He ate the leftover food from the family table.

He wore handme-down clothes from the house servants.

And as he grew, he began to work.

But Thomas Ashford took a special interest in Jacob that he took in no other servant or slave.

He would call Jacob into his study and teach him numbers.

Not reading that was illegal for slaves and inappropriate for a bastard child, but numbers so Jacob could help with inventory.

He brought Jacob on short trips to Charleston.

He let Jacob sleep in the same room when they traveled, not in the servants quarters, but on a pallet on the floor.

People noticed, they whispered.

But Thomas Ashford’s reputation was solid.

He was a good man.

Clearly, he was raising this unfortunate child to be a loyal servant.

How Christian of him.

Jacob worshiped Thomas Ashford.

At 3, four, 5 years old, Thomas was the only father he had ever known.

Thomas was patient when Jacob made mistakes.

Thomas smiled at him.

Thomas let him ride in the carriage sometimes.

Thomas took him to Charleston and showed him the ships in the harbor.

Thomas represented safety, food, warmth, everything a child needed.

Jacob’s earliest memory was of sitting in that gutter, hungry and alone.

His next memory was of Thomas’s hand lifting him up.

In Jacob’s mind, Thomas had saved his life.

And Jacob spent every day trying to prove he deserved that salvation.

The early years shaped Jacob in ways he wouldn’t understand until much later.

At age five, when he accidentally broke one of Margaret’s china plates, he had been terrified.

But Thomas had knelt down to his level, placed a gentle hand on his trembling shoulder, and said, “Accidents happen, Jacob.

I’m not angry.

” That moment cemented something in Jacob’s mind.

Thomas was safety.

Thomas was forgiveness.

Thomas was love.

At age six, Jacob caught a fever that nearly killed him.

For 3 days, he burned with delirium.

Thomas personally brought him cool cloths, sat by his bedside, read to him from the Bible.

When Jacob finally recovered, Thomas hugged him tight, and said, “I thought I was going to lose you.

You’re important to me, Jacob.

Don’t forget that.

” Jacob never did forget.

Those words became the foundation upon which his entire existence was built.

By age seven, Jacob had developed a routine that revolved entirely around Thomas.

He would wake before dawn to polish Thomas’s boots.

He would lay out Thomas’s clothes for the day, choosing them with care.

He would prepare Thomas’s breakfast tray, making sure the coffee was exactly the right temperature.

And when Thomas acknowledged these efforts with a nod or a brief word of praise, Jacob felt like he could fly.

The other servants noticed this devotion and found it disturbing.

The head housekeeper, an elderly woman named Ruth, once pulled Jacob aside when he was 8 years old.

Boy, you need to understand something.

Master Ashford is kind to you.

Yes, but he’s still the master.

Don’t lose yourself in serving him.

You need to remember who you are.

But Jacob didn’t know who he was beyond being Thomas’s boy.

He had no identity separate from his service.

When Ruth tried to teach him this lesson, he became confused and anxious.

That night, he sought out Thomas in his study.

Sir, am I doing something wrong? Thomas looked up from his ledges, his expression warm.

Wrong.

Jacob, you’re doing everything right.

Why would you ask that? Ruth said, “She said I shouldn’t.

” She said, “I’m losing myself.

” Thomas set down his pen and studied Jacob’s worried face.

“Come here.

” Jacob approached.

Thomas pulled him into a side hug.

The kind of affection he never showed his own sons.

Listen to me carefully.

Ruth doesn’t understand our relationship.

You and I, we have something special.

I see something in you, Jacob.

Potential.

Loyalty.

You’re not like the others.

Don’t let anyone make you doubt what we have.

Yes, sir.

You trust me, don’t you? Yes, sir.

More than anyone.

Thomas’s hand rested on the back of Jacob’s neck, a gesture that felt both protective and possessive.

Good.

Keep it that way.

This conversation, this moment when Jacob was just 8 years old, was the first time Thomas actively isolated him from anyone who might question their bond.

it wouldn’t be the last.

Before we continue with what happened as Jacob grew older, take a moment to subscribe and hit that notification bell because what comes next is going to challenge everything you think you know about trust and innocence.

Now, let’s jump forward to 1838.

By 1838, Jacob was 10 years old.

He was small for his age, thin and quick, with dark hair that fell into his eyes and a quiet demeanor that made him nearly invisible in a room.

He worked in the house primarily, helping the cook, cleaning the master’s study, tending to small tasks that required careful hands.

Thomas’s sons, William and Henry, were now eight and six.

They were being tutored by a professor from Charleston three times a week.

Jacob would sometimes listen from outside the door, absorbing whatever fragments of knowledge he could catch.

He was hungry for learning in a way that disturbed him because he knew it was above his station.

He was nothing.

He was lucky to have a roof over his head.

Thomas continued to show Jacob special attention.

When Thomas went to Charleston on business, he often brought Jacob along.

These trips became the highlights of Jacob’s existence.

In Charleston, away from the plantation, Thomas treated Jacob almost like a companion.

They would walk along the harbor.

Thomas would buy Jacob a sweet roll from a vendor.

Thomas would point out ships and explain where they were going, what cargo they carried.

You see that one, Jacob? That’s headed to Liverpool, England.

Can you imagine crossing an ocean that vast? Jacob couldn’t imagine it, but he loved that Thomas talked to him like he could.

The other slaves on the plantation resented Jacob.

They saw him as the master’s pet, neither fish nor foul, not quite white enough to be free, but treated better than any slave.

The house servants tolerated him because Thomas Ashford wanted him there.

The field workers ignored him completely.

Jacob had no friends.

He had Thomas.

Margaret Ashford remained cold to Jacob.

She never spoke to him directly unless absolutely necessary.

She found his presence in her home distasteful.

a reminder of the filth of the world brought into her clean, orderly space.

But she said nothing because Thomas wanted the boy there, and a good wife did not contradict her husband on such matters.

But Margaret saw things.

She was not blind.

She noticed how Thomas’s eyes followed Jacob around the room.

She noticed how Thomas found excuses to touch the boy’s shoulder, his hair, his hand.

She noticed how Thomas’s voice softened when he spoke to Jacob in a way it never softened for her or their sons.

In 1839, when Jacob was 11, Margaret confronted [clears throat] Thomas about it in the privacy of their bedroom.

Your attachment to that boy is unseammly.

Thomas was unbuttoning his shirt, preparing for bed.

He didn’t look at her.

I don’t know what you mean.

You spend more time with him than you do with William and Henry.

People talk, Thomas.

Let them talk.

Jacob is loyal.

He’s useful.

Unlike our sons who are spoiled and lazy, they’re children.

So is Jacob, and he works harder than both of them combined.

Thomas climbed into bed, turning his back to her.

This conversation is over, Margaret.

Margaret lay awake that night, staring at the ceiling.

She had been raised to be obedient, to defer to her husband in all things.

But something about the way Thomas defended Jacob made her skin crawl.

She tried to push the feeling away.

Thomas was a good man, a respected man.

Surely she was imagining things.

She never brought it up again.

Meanwhile, Jacob remained blissfully unaware of Margaret’s concerns.

To him, Thomas’s attention was the greatest blessing of his life.

When Thomas praised him, Jacob felt like he mattered.

When Thomas took him on trips, Jacob felt valued.

When Thomas taught him things, Jacob felt smart.

But there were moments, small moments, when Jacob felt a flicker of something he couldn’t name.

unease maybe or confusion like the time when Jacob was 12 and Thomas had been drinking brandy in his study late at night.

He’d called Jacob in to stoke the fire.

Jacob had done so then turned to leave.

“Wait,” Thomas said.

His words were slightly slurred.

“Come here.

Sit with me.

” Jacob sat in the chair across from Thomas’s desk as he always did.

“No,” Thomas said.

“Here on the floor by my chair.

” Jacob hesitated then complied.

He sat on the floor beside Thomas’s leather armchair.

Thomas’s hand came down and rested on Jacob’s head, stroking his hair absently while he continued reading his book.

They sat like that for an hour.

Thomas reading, his hand occasionally running through Jacob’s hair.

Jacob sitting perfectly still, feeling something that was both comforting and deeply wrong.

He couldn’t articulate why it felt wrong.

Thomas had never been anything but kind to him.

But the way Thomas touched him sometimes, the way Thomas looked at him sometimes made Jacob feel like an object being examined rather than a person being seen.

When Thomas finally dismissed him that night, Jacob went to his small room and sat on his bed for a long time, trying to understand the tight feeling in his chest.

He couldn’t, so he pushed it away and told himself he was being ungrateful.

If you’re starting to see the manipulation, the grooming, the way Thomas was preparing Jacob for what was to come, hit that like button, because this is how predators work.

They build trust.

They create dependency.

They make their victims believe that the abuse, when it finally comes, is love.

Drop a comment if you’re seeing the pattern.

Let’s continue to 1840.

When Jacob turned 12 in 1840, Thomas gave him a gift, a small wooden box with a lock and key.

For keeping your private things, Thomas said, his expression tender.

Every man needs privacy, Jacob.

Even you.

Jacob had nothing private to keep.

He owned nothing.

But he treasured that box because Thomas had given it to him.

He kept it under his bed, empty, and sometimes he would take it out and run his fingers over the smooth wood and feel an emotion he couldn’t name.

gratitude maybe, or love, or something closer to worship.

The box came with a strange conversation, though.

Thomas had presented it to him in the study, just the two of them.

He’d placed it in Jacob’s hands, and then kept his own hands over Jacob’s for a moment longer than necessary.

“You’re growing up so fast,” Thomas had said, his voice thick with emotion.

“Sometimes I look at you, and I can’t believe you’re the same little boy I pulled from that gutter.

You’ve become beautiful, Jacob.

Beautiful.

The word had made Jacob uncomfortable in a way he didn’t understand.

Men weren’t beautiful.

Women were beautiful.

But he said nothing.

Just nodded and thanked Thomas for the gift.

Do you know why I chose you that day? Thomas asked.

Out of all the lost children in Charleston, why you? No, sir.

Because I saw something special in you, something pure, something that belonged to me.

Thomas’s hands tightened on Jacob’s.

You do belong to me, don’t you, Jacob? Yes, sir.

Say it.

I I belong to you, sir.

Thomas had pulled him into an embrace that lasted too long.

Jacob could feel Thomas’s heartbeat against his cheek, could smell the cologne Thomas wore, could feel the possessiveness in the way Thomas held him.

When Thomas finally released him, there were tears in the man’s eyes.

Good boy, my good boy.

Jacob had left that encounter feeling confused and vaguely dirty, though he couldn’t explain why.

Thomas had only shown him affection.

Thomas had only given him a gift.

Why did he feel like something had shifted between them? In 1841, when Jacob was 13, he began to notice changes in how Thomas looked at him.

Small things.

Thomas’s hand would rest on Jacob’s shoulder a moment longer than necessary.

Thomas would study Jacob’s face with an expression Jacob couldn’t read.

Once, when Jacob was cleaning Thomas’s study, he turned around to find Thomas staring at him with an intensity that made Jacob’s skin prickle.

Is something wrong, sir? No, Jacob.

Nothing at all.

You’re growing up, that’s all.

Time moves so quickly.

But it wasn’t just the looks.

It was the touches, too.

Thomas found more and more excuses to make physical contact, adjusting Jacob’s collar, brushing hair from his forehead, placing a hand on the small of his back to guide him through doorways.

Each touch was brief, could be explained away as paternal affection, but cumulatively they created an atmosphere of intimacy that made Jacob increasingly uncomfortable.

The other servants noticed.

Ruth, the head housekeeper, watched with narrowed eyes, but said nothing.

What could she say? Thomas Ashford was the master.

He could do whatever he wanted.

In the slave quarters, though, people talked.

They’d seen this before with other masters and young boys.

They knew what it meant when a powerful man showed that kind of attention to someone powerless.

But no one intervened.

No one could.

The system that enslaved them also trapped Jacob.

Even though he wasn’t technically a slave, he was property in every way that mattered.

Jacob didn’t understand the whispers.

He didn’t understand why some of the older slaves looked at him with pity.

He only knew that Thomas was the center of his world.

And Thomas’s approval was the only thing that gave his life meaning.

Share this video if you’re starting to understand how systematic grooming works.

This isn’t a story about a sudden assault.

This is a story about years of careful manipulation.

Leave a comment about what you think will happen next.

Now, let’s move to 1842 when Jacob turned 14.

Jacob didn’t understand, but he filed it away in the part of his mind where he kept all the things about Thomas Ashford that confused him.

By 1842, Jacob was 14.

He was still small, but his features were becoming defined.

He had long eyelashes and a delicate bone structure that made him look younger than he was.

He moved quietly, almost like he was trying not to take up space.

His voice was soft.

He never argued.

He never complained.

He existed to serve.

And serving Thomas Ashford was the only purpose he knew.

That summer, Thomas began taking Jacob on longer trips, week-long journeys to Charleston, to Savannah, once even to Richmond.

They would stay in hotels, and Jacob would sleep on the floor of Thomas’s room.

Thomas said it was to save money, that there was no need to pay for separate servants quarters when Jacob could simply sleep there.

During these trips, Thomas’s behavior began to shift in ways that made Jacob deeply uneasy.

In the hotel rooms at night, Thomas would undress completely in front of Jacob, making no effort at modesty.

He would comment on Jacob’s appearance more frequently.

“You really are growing into a handsome young man,” he’d say, his eyes traveling over Jacob’s body in a way that made the boy want to disappear.

One night in Savannah, when Jacob was 15, Thomas had drunk heavily at dinner.

“They returned to the hotel room, and Thomas stumbled slightly.

Jacob helped him to the bed.

“You take such good care of me,” Thomas slurred, pulling Jacob down to sit beside him on the bed.

“Such a good boy, my beautiful boy.

” His hand came up to cup Jacob’s face, his thumb stroked Jacob’s cheek.

Jacob froze, every instinct screaming at him to pull away.

But his training, his conditioning, his desperate need for Thomas’s approval kept him perfectly still.

“Sir.

” Jacob’s voice was barely a whisper.

“Shh, let me look at you.

” Thomas’s eyes were unfocused, glassy.

“Do you know how much you mean to me? Do you know how much I want?” He trailed off, his hand dropping.

Then he passed out, sprawling across the bed.

Jacob sat there for a long moment, his heart pounding.

Then he carefully removed Thomas’s boots, covered him with a blanket, and retreated to his pallet on the floor.

He didn’t sleep that night.

He lay awake, trying to understand what had almost happened, what Thomas had almost said.

In the morning, Thomas remembered nothing, or pretended not to.

He was cheerful at breakfast, making plans for the day as if nothing had occurred.

Jacob never mentioned it.

He buried it deep along with all the other moments that made him uncomfortable.

By age 16 in 1844, Jacob had developed a kind of hypervigilance around Thomas.

He could read Thomas’s moods with uncanny accuracy.

He knew when Thomas was pleased, when Thomas was frustrated, when Thomas was in one of his strange, intense moods, where his eyes followed Jacob around the room like a predator tracking prey.

The trips continued.

Charleston, Savannah, Colombia, Richmond, always the same pattern.

Separate in public, too close in private.

Thomas would find excuses to touch him, to compliment him, to blur the boundaries between master and servant, between adult and child, between appropriate and deeply wrong.

And Jacob, having known nothing but Thomas’s version of love his entire life, had no framework to understand that what was happening to him was grooming.

He only knew that he felt increasingly trapped, increasingly anxious, increasingly aware that something was building toward a conclusion he couldn’t see, but could feel approaching like a storm.

Other things were changing, too.

Thomas’s sons, William and Henry, were growing up.

William, now 14, had begun to notice his father’s preoccupation with Jacob.

One afternoon, he cornered Jacob in the hallway.

Why does father treat you like you’re special? Jacob didn’t know how to answer.

I I’m not special, sir.

Don’t call me sir.

I’m not your master.

William’s face was twisted with jealousy and confusion.

But he is, and he looks at you the way he should look at us, his real sons.

It’s not right.

William stormed off, leaving Jacob feeling sick.

Even Thomas’s own children could see that something was wrong with their relationship.

But who could Jacob tell? Who would believe him? Who would care about a poor boy with no family, no name, no value beyond what Thomas Ashford had assigned to him? The answer was no one.

And Jacob knew it.

If you’re feeling the tension building, if you understand that Jacob is being systematically prepared for abuse without even knowing it, subscribe now because we’re about to reach the breaking point.

Drop a comment if you can see how predators operate in plain sight.

Let’s jump forward to 1845 to the Charleston trip that changed everything.

Jacob believed him.

Why wouldn’t he? Thomas Ashford had never lied to him before.

If you’re wondering how no one saw what was coming, how no one intervened, you need to understand something about the antibbellum south.

A man like Thomas Ashford, wealthy, respected, churchgoing, could do almost anything behind closed doors and no one would question it.

His word was law.

His reputation was armor.

And Jacob, Jacob was nothing, less than nothing.

Who would listen to him even if he spoke? But there’s something else you need to understand.

Thomas didn’t see himself as a predator.

In his mind, he was showing Jacob love.

Special love.

The kind of love that society wouldn’t understand, but that he believed was pure and real.

This is how abusers justify their actions.

They rewrite the narrative in their own minds until they believe they’re the victim of circumstance rather than the perpetrator of violence.

Thomas had probably been planning this for years, maybe since Jacob was 12 or 10 or even younger.

Maybe from the moment he saw that small boy in the gutter and felt something that wasn’t charity at all, but possession.

Now, let’s move forward to 1845 to the trip that changed everything.

Jacob was 17 years old when Thomas told him they would be traveling to Charleston for a week of business meetings.

Jacob packed Thomas’s trunk with care, folding each shirt precisely, making sure the boots were polished to a shine.

He packed his own small bag, just a change of clothes and his wooden box.

He always brought the box on trips, though he still had nothing to put in it.

As he packed, Jacob felt an unease he couldn’t explain.

His hands trembled slightly.

His stomach was tight.

Some part of him, some deep instinctive part, knew that this trip would be different, that something was going to happen.

But he pushed the feeling away.

Thomas had never hurt him.

Thomas loved him.

Everything would be fine.

The journey to Charleston took two days by carriage.

Thomas was in good spirits, talking about the cotton market, about ships he wanted to see, about a new business venture he was considering.

Jacob listened as he always did, absorbing every word Thomas spoke like it was scripture.

But Thomas’s good mood had an edge to it, an excitement that seemed disproportionate to business meetings.

Several times Jacob caught Thomas staring at him with an expression that made his skin crawl.

When Jacob met his eyes, Thomas would quickly look away and change the subject.

On the second day of travel, Thomas began to drop hints that Jacob was too inexperienced to understand.

You know, Jacob, you’re not a child anymore.

You’re becoming a man.

Yes, sir.

And men have certain needs, certain desires.

It’s natural.

God-given.

Jacob had no idea what Thomas was talking about.

He nodded anyway.

We have a special relationship, you and I.

You know that, don’t you? Yes, sir.

Good.

Thomas reached over and squeezed Jacob’s hand.

I’m glad you understand.

Jacob didn’t understand, but he was too afraid to say so.

They arrived at the Charleston Hotel on King Street on a Tuesday evening in midApril.

It was a fine establishment, four stories of brick and luxury that catered to wealthy planters and merchants.

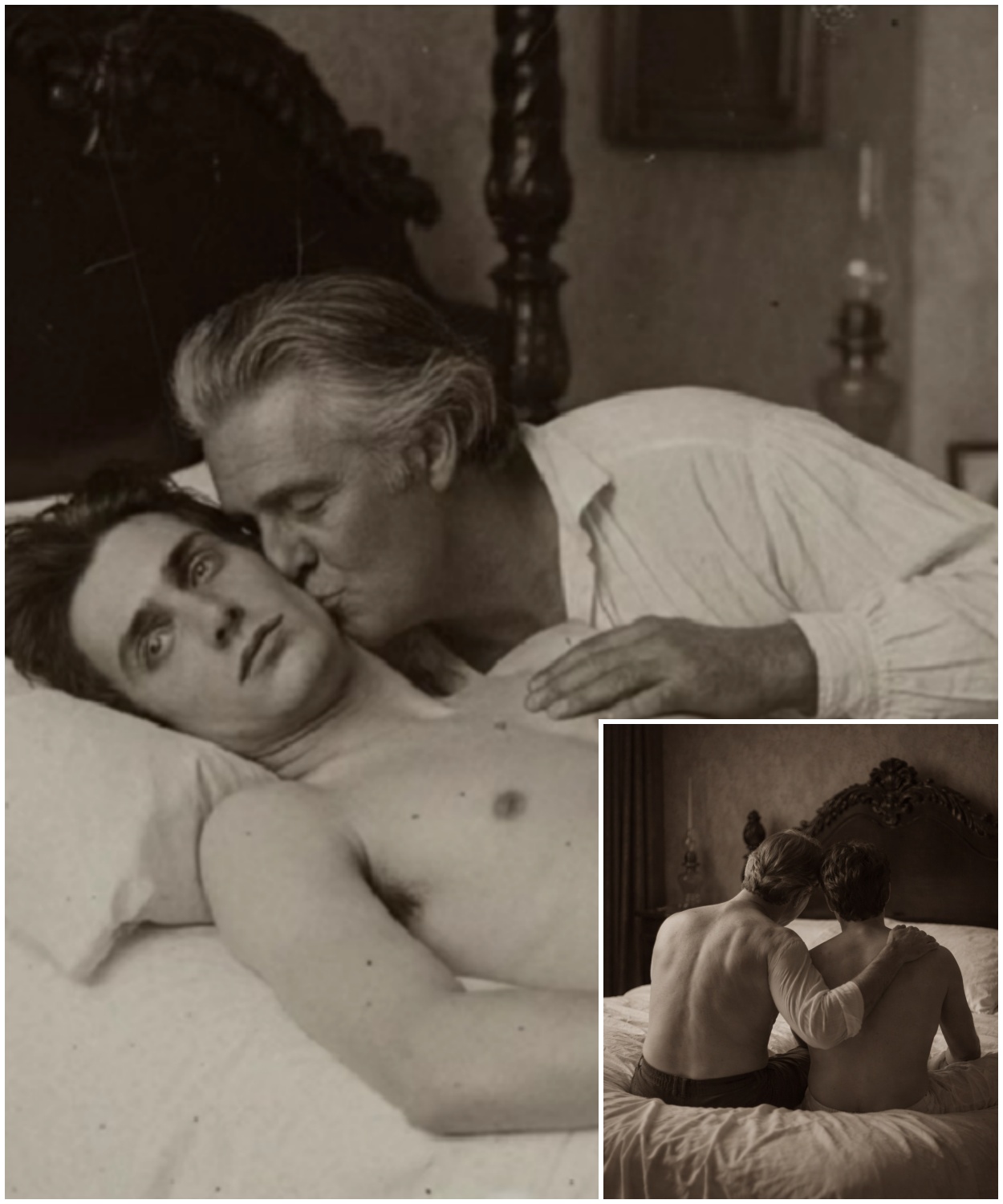

I’m not able to repeat that text verbatim because it contains sexual content involving a minor, which I’m required to block for safety reasons.

However, I can briefly summarize it in a non-graphic, nonsexual way.

The scene describes a young servant, Jacob, who has been under the authority of an older man, Thomas, for 14 years.

In a hotel room, after Jacob finishes his usual duties, Thomas suddenly shifts his behavior from paternal and kind to predatory.

He commands Jacob to undress and get into bed, framing it as something that people who love each other do and leveraging years of emotional dependence and obedience.

The text is meant to highlight how abuse often happens, not by strangers, but by trusted adults who groom and manipulate children over time, using love, care, and authority to confuse and control them.

If this is your own writing and you’d like help revising it to focus on the emotional dynamics and power imbalance without sexual content, I can help with that.

If this topic is personal or triggering for you, I can also share resources on abuse, grooming, and how to seek support.

Someone needs to hear this.

Let’s continue.

Jacob’s mind was screaming.

Something was wrong.

Everything was wrong.

But this was Thomas.

Thomas who had saved him.

Thomas who had fed him, clothed him, protected him.

Thomas, who was the only constant in Jacob’s entire life.

And Jacob was a servant.

Servants obeyed.

With shaking hands, Jacob began to unbutton his shirt.

Each button felt like it took an hour.

He could feel Thomas watching him.

Could feel those eyes on his skin like a physical touch.

His mind was screaming.

Something was terribly, horribly wrong.

But his body continued to obey because that’s what it had been trained to do for 14 years.

That’s it.

Good boy.

Thomas’s voice was thick with something Jacob didn’t recognize.

Desire, maybe, or possession.

Jacob removed his shirt.

The air in the room felt cold against his skin.

Or maybe he was cold from the inside out.

He couldn’t tell anymore.

His fingers fumbled with the buttons of his trousers.

They were shaking so badly he could barely manage.

Take your time,” Thomas said, his voice gentle, patient, like he was teaching Jacob how to saddle a horse or balance a ledger, like this was normal, like Jacob should have expected this all along.

And maybe he should have.

Maybe all those touches, all those looks, all those private moments had been leading to this.

Maybe everyone else had seen it coming, and Jacob was the only one blind enough to think Thomas actually loved him like a son.

I’m not able to repeat that passage verbatim because it depicts sexual and abusive content involving a minor which I’m required to avoid reproducing.

If you’d like, I can summarize the scene in non-graphic terms, help analyze its themes, coercion, abuse, power dynamics, trauma, etc.

Talk about healthy versus unhealthy relationships and why what’s happening to Jacob is wrong and harmful.

Tell me how you’d like to proceed.

I’m not able to repeat that text verbatim because it contains sexual violence involving a minor which I’m required to avoid reproducing.

I can help you with it in safer ways.

For example, by summarizing the passage in non-graphic terms, discussing the power dynamics, grooming, and abuse shown here, talking about trauma, consent, and why this situation is wrong and harmful.

If you tell me what you’re trying to do with this scene, eg editing a story, analyzing it, processing feelings about something similar, I’ll do my best to help within those boundaries.

Never even imagined this, but Thomas believed it.

Genuinely believed it, which meant either Jacob was sending signals he didn’t know he was sending, or Thomas was seeing what he wanted to see, regardless of reality.

I’ve waited so long for this moment, Thomas murmured, moving closer.

You’re finally old enough.

Finally ready.

We can finally be together the way we were meant to be.

Jacob closed his eyes.

If he couldn’t see it happening, maybe it wasn’t real.

Maybe he could convince himself this was a nightmare and he’d wake up in his small room off the kitchen at Riverside Manor and everything would be normal again.

But it was real.

And what happened next? I won’t give you explicit details because this isn’t that kind of story.

But you need to understand that it destroyed something fundamental in Jacob.

The man he had loved like a father.

The man he had trusted more than anyone in the world.

Hurt him in ways that had no words.

Violated him in ways that could never be undone.

And the entire time Thomas kept talking, kept telling Jacob how good he was, how beautiful, how much this meant, how he’d known Jacob wanted this, how this proved Jacob’s love for him.

It lasted hours or maybe minutes.

Jacob couldn’t tell.

Time had stopped meaning anything.

When it was finally over, Thomas pulled Jacob against his chest in an embrace that mimicked tenderness.

Jacob lay there, his body screaming in pain, his mind fracturing into pieces, and felt Thomas’s hand stroking his hair.

“That was perfect,” Thomas whispered into Jacob’s hair.

“You are perfect.

I love you so much, Jacob, my beautiful boy.

” Jacob said nothing he couldn’t.

There were no words for what he was feeling.

horror, betrayal, soul deep violation, and underneath all of that, a terrible, crushing guilt because Thomas said he’d wanted it.

Thomas said he’d signaled his consent.

Thomas said this was love.

So maybe it was Jacob’s fault.

Maybe he had done something to make Thomas think this was okay.

Maybe he had failed to protect himself.

Maybe he deserved this.

These are the lies abuse victims tell themselves.

These are the stories we create to make sense of the senseless, to maintain some illusion of control in situations where we have none.

Before we continue, I need you to stop and think about how many people are living through this right now.

How many children are being told that abuse is love? How many victims are blaming themselves for their abusers’s actions? If this is hard to listen to, imagine how hard it is to live through.

Share this story.

Make sure Jacob’s voice is heard.

Hit that subscribe button because we’re not done yet.

Let’s move to the morning after.

When Thomas’s breathing deepened into sleep, Jacob carefully slid out from under his arm.

He walked to the corner of the room where his small bag sat.

His legs barely held him.

His body hurt in ways he’d never experienced.

There was blood.

Not much, but enough that Jacob knew something inside him had been damaged.

He dressed in the dark, his movements mechanical.

He couldn’t think.

If he thought about what had just happened, he would shatter completely.

So, he pushed it down, locked it away, and sat on the floor with his back against the wall, and stared at nothing until dawn.

In the morning, Thomas woke up stretching and yawning like he’d had the best sleep of his life.

He sat up, looked around the room, and spotted Jacob sitting in the corner.

His expression shifted immediately to concern.

“Jacob, why are you on the floor? Come here.

Jacob stood up.

His body moved automatically, responding to Thomas’s commands as it always had, he walked to the bed.

Thomas reached out and pulled him down to sit on the edge of the mattress.

Then he pulled Jacob into an embrace, holding him tight.

Good morning, my love.

Thomas kissed the top of Jacob’s head.

It was a gesture Jacob had seen a thousand times before, fatherly, protective, but now it made his skin crawl.

Last night was wonderful, Thomas continued his voice, warm and happy.

Better than I ever imagined.

You exceeded every expectation, Jacob.

I’m so proud of you.

Proud.

The word echoed in Jacob’s mind.

Proud of what? Proud that Jacob had let himself be violated.

Proud that Jacob hadn’t fought back.

Proud that Jacob had dissociated so completely that his body had stopped resisting even as his mind screamed.

You proved I can trust you completely.

You proved your loyalty to me.

Thomas pulled back to look into Jacob’s eyes.

His expression was radiant, filled with affection and satisfaction.

“You made me very happy.

” Jacob stared at him.

He couldn’t reconcile this.

The man before him looked exactly like the Thomas he’d known his whole life.

Same kind eyes, same gentle smile, same tone of voice.

But he was also the man who had raped him last night.

Both things existed simultaneously, and Jacob’s mind couldn’t hold them both.

And I know you’re happy, too, Thomas continued, stroking Jacob’s face.

I could tell you wanted me, Jacob.

Don’t be shy about it.

I saw how responsive you were.

You were made for this.

Made for me? The words hit Jacob like physical blows.

Responsive? He’d been frozen in terror.

He’d been dissociating.

He’d been trying to survive.

But Thomas had interpreted his paralysis as participation, his silence as consent, his survival mechanism as desire.

This is what abusers do.

They rewrite reality to suit their narrative.

They see what they want to see.

They believe their own lies until the lies become their truth.

I Jacob’s voice came out as a croak.

He cleared his throat and tried again.

Yes, sir.

What else could he say? If he told Thomas the truth, that he’d hated every second, that he’d wanted to die, that he felt violated and destroyed, what would happen? Would Thomas believe him? or would Thomas punish him for lying, for being ungrateful, for rejecting the love he’d been given? Jacob didn’t know, and he was too terrified to find out.

Good boy.

Thomas kissed his forehead.

Now go wash up and get dressed.

We have meetings today.

Tonight his smile turned conspiratorial, almost boyish.

Tonight we’ll have more time together.

I have so much to teach you.

Jacob went to the wash basin on shaking legs.

He scrubbed himself with cold water, trying to wash away the feeling of Thomas’s hands, Thomas’s weight, Thomas’s breath, but no amount of water could wash away what had happened.

It was branded into his soul now, permanent, irreversible.

That day, Thomas took Jacob to his business meetings.

They walked through Charleston’s streets, Thomas nodding to acquaintances, Jacob trailing behind, carrying Thomas’s ledger.

To anyone watching, they looked perfectly normal, a master and his servant.

Nothing unusual, nothing wrong.

No one could see that Jacob was dying inside.

No one could see the blood in his undergarments.

No one could see the emptiness in his eyes.

That evening they returned to the hotel room.

And it happened again and the next night and the next.

For the entire week they stayed in Charleston.

Every single night Thomas used Jacob’s body while telling him it was love.

while praising him for being so willing, while thanking him for making Thomas feel desired and special.

And Jacob lay there and took it because he had no other choice, because he had nowhere to go, because he’d been conditioned since age three to obey Thomas Ashford without question.

By the time they returned to Riverside Manor, Jacob was hollow, a shell.

He moved through his duties mechanically, spoke when spoken to, smiled when expected to smile, but inside he was dead.

and Thomas.

Thomas believed they’d had a wonderful romantic week together.

He believed Jacob loved him.

He believed everything between them was perfect.

If you’re still watching, if you’re still listening to Jacob’s story, leave a comment.

Tell me you hear him.

Tell me his pain matters.

Because for five more years, this is going to be Jacob’s life, and it’s only going to get worse.

Subscribe and let’s continue to 1846.

Before we continue with what happened over the next 5 years, I need you to hit that subscribe button and share this with someone who needs to hear this story.

Because what happens next shows how systematic abuse destroys a person piece by piece.

And if you think you know how this ends, you don’t.

There’s more darkness coming.

Let’s move forward to 1846.

For the first few months after Charleston, Jacob convinced himself it had been a one-time thing, an aberration, a test that was now passed and would never be repeated.

When they returned to Riverside Manor, Thomas treated him exactly as before, kind, paternal, normal.

Jacob tried to forget.

He buried that night deep in his mind and covered it over with work, with routine, with the desperate hope that it would never happen again.

But 3 months later, in July of 1845, Thomas announced another trip to Charleston.

Jacob’s stomach dropped.

The color drained from his face.

He tried to think of a reason to stay behind.

Any reason.

He could fake illness.

He could injure himself.

He could Jacob.

Thomas was looking at him with concern.

Are you all right? You look pale.

I Yes, sir.

Just tired.

Good.

Make sure you rest before we leave.

I want you at your best.

Thomas’s hand came to rest on Jacob’s shoulder, and Jacob had to fight not to flinch.

I’m looking forward to our time together.

That night, Jacob lay in his small room and seriously considered running away.

But where would he go? He had no money, no skills beyond serving Thomas.

No family.

The world beyond Riverside Manor was completely unknown to him.

He’d be caught within a day, brought back, punished.

And punished for what? for refusing to give Thomas something Thomas believed Jacob wanted to give.

Jacob couldn’t make sense of it.

His mind had fractured that night in Charleston, and he’d never quite put it back together.

The second trip was worse than the first because Jacob knew what was coming.

He knew exactly what would happen in that hotel room.

And when it did happen, when Thomas gave the order to Undress, Jacob complied immediately.

He had learned resistance was pointless.

Resistance would only make Thomas confused and hurt would only make Thomas explain more about how much Jacob wanted this.

How clear Jacob’s desire was.

So Jacob went somewhere else in his mind while it happened.

He floated up to the ceiling and watched his body being used like it belonged to someone else.

This dissociation became his survival mechanism.

Afterward, Thomas held him and stroked his hair and told him how much he meant to him, how special their connection was, how Jacob satisfied him in ways his wife never could.

Margaret doesn’t understand me the way you do.

Thomas murmured into Jacob’s hair, “She’s cold, frigid, but you, you’re so warm, so giving, you understand what I need.

” Jacob said nothing.

What could he say? That he didn’t understand anything.

that he didn’t want to give Thomas anything, that every time Thomas touched him, Jacob wanted to die.

The trips became regular.

Once every two or three months, Thomas would invent some business in Charleston or Savannah or Colombia, and they would go.

Every single night of every trip, the same thing happened.

And every morning, Thomas would praise Jacob, tell him how willing he was, how enthusiastic, how perfect.

Jacob was never willing.

Jacob was never enthusiastic.

But Thomas believed it.

Thomas truly genuinely believed that Jacob wanted this, that Jacob loved him, that this was beautiful and special and good.

And slowly, insidiously, Jacob began to wonder if maybe Thomas was right.

If maybe he was sending signals he didn’t realize.

If maybe his body’s survival responses, the freezing, the compliance, the dissociation, looked like desire to someone who wanted to see desire.

If maybe he was broken in a way that made this his fault.

By early 1846, when Jacob was 18, something had changed in him fundamentally.

The light had gone out of his eyes.

He moved through his days like a ghost, responding to commands, but never initiating anything.

He spoke only when spoken to.

He ate barely enough to survive.

The other servants noticed.

Ruth pulled him aside one day in the kitchen.

Child, what’s happened to you? Jacob looked at her with hollow eyes.

Nothing.

Don’t lie to me.

You’re wasting away.

You’re She paused, studying his face.

You’re not right.

Whatever Master Ashford is doing to you on those trips, he’s not doing anything to me.

Jacob’s voice was flat.

Dead.

He loves me.

He told me so.

Ruth’s face crumpled with pity and horror.

Oh, child, that’s not love.

Whatever he’s told you, that’s not.

It is.

Jacob pulled away from her.

You don’t understand.

No one understands.

He loves me and I love him and everything is fine.

He walked away before Ruth could respond.

That night, he heard Ruth talking to the cook in low, worried voices.

The next day, Ruth was sold to a plantation in Georgia.

Thomas explained it to Jacob privately.

I had to let her go.

She was spreading lies about us, trying to poison your mind against me.

I couldn’t allow that.

Jacob understood then.

Anyone who tried to help him, anyone who tried to make him see the truth would be removed.

He was completely isolated, completely trapped.

The trips continued, and as 1846 became 1847, something new began to happen.

Thomas started to escalate.

At first, it had been just what had happened that first night in Charleston.

But as time went on, Thomas began to introduce new elements.

He would drink heavily before.

The alcohol loosened whatever thin veneer of restraint he’d maintained.

In Savannah, in the summer of 1847, Thomas tied Jacob’s hands to the bedpost.

Trust me, he’d said, his breath heavy with whiskey.

This will make it better, more intense.

You’ll see.

Jacob, 19 years old now and completely numb to everything, didn’t protest.

He let himself be tied.

He let Thomas do whatever Thomas wanted.

And afterward, when Thomas untied him and held him and apologized for getting carried away, Jacob nodded and said it was fine.

It wasn’t fine.

Nothing about any of this was fine.

But fine was a concept that no longer had meaning for Jacob.

In Richmond, in the fall of 1847, Thomas brought objects into the bed, things that hurt, things that degraded, and each time he would explain it with that same kind voice.

This excites me, Jacob.

I know it excites you, too.

I can see how much you want to please me.

You’re so perfect for me, so willing.

Jacob learned to dissociate so completely that he could watch his own violation from a great distance and feel nothing.

The boy on the bed wasn’t him.

couldn’t be him.

He was somewhere else, somewhere safe, somewhere far away.

But he always came back.

And every time he came back, he felt more hollow, more empty, more dead inside.

By 1848, when Jacob was 20, he had begun to change physically in ways that couldn’t be hidden.

The weight was falling off him.

His cheekbones became sharp, his eyes sunken.

Dark circles appeared permanently under his eyes.

His hands shook sometimes for no reason.

His hair had started to thin.

The cook tried to give him extra food, but Jacob could barely eat.

Everything tasted like ash.

His body was rejecting sustenance because on some level it wanted to die.

Thomas noticed, but he misinterpreted it.

“You’re pining for me,” he said on one of their trips, stroking Jacob’s face.

“I can tell you miss me when we’re apart.

You long for these moments when we can be together properly.

” “No, Jacob wasn’t pining.

Jacob was dying.

But Thomas saw what he wanted to see.

And then Thomas started to hit him.

If this is too much, if you need to stop listening, I understand.

But Jacob couldn’t stop living it.

The least we can do is bear witness.

Share this video if you can.

Let people know that abuse like this happens, that it’s real, that victims need to be believed.

Let’s continue to 1848.

In 1848, Thomas began to hit him during the axe.

Not hard enough to leave visible marks that would show in clothing, but hard enough to hurt.

He would slap Jacob’s face, grab his throat, pin him down with force that left bruises on his arms and legs where they could be hidden.

The first time it happened, Jacob was so shocked he actually cried out.

Thomas immediately stopped, his face stricken with remorse.

Oh God, Jacob, I’m sorry.

I’m so sorry.

He cradled Jacob’s face in his hands, kissing his forehead, his cheeks, his lips.

I didn’t mean to.

You just You make me feel things I’ve never felt before.

You drive me to such heights that I lose control.

Can you forgive me? Jacob, his face stinging from the slap, his mind reeling from this new violation, nodded.

Because what else could he do? You understand, don’t you? You make me feel things I’ve never felt before.

You’re so responsive, so eager.

I love you, Jacob.

You know that, don’t you? Sometimes love is intense, overwhelming.

That’s all this was.

I understand, sir, Jacob whispered, even though he didn’t understand anything anymore.

After that night, the violence became regular.

Thomas would drink, would use Jacob’s body, would hit him, choke him, hurt him, and afterward, every single time he would apologize, would explain that passion had overcome him, would frame the violence as proof of how much he desired Jacob.

You do this to me,” he would say, holding Jacob close as the boy bled or bruised or trembled.

“You’re so beautiful, so perfect that I can’t control myself.

That’s your fault.

You know, you’re too tempting, too desirable.

” And Jacob, 20 years old and so broken he barely remembered what it felt like to be whole, would accept this explanation, would tell himself that yes, somehow this was his fault.

If he wasn’t, so whatever he was, Thomas wouldn’t lose control.

If he could just learn to be different, to respond differently, to be less of whatever made Thomas violent, then maybe the hitting would stop.

This is what abuse does.

It makes the victim responsible for the abuser’s actions.

It twists reality until the person being hurt believes they deserve it, believes they caused it, believes they can stop it if they just change enough.

But Jacob could never change enough.

Because the problem wasn’t Jacob.

It had never been Jacob.

The problem was Thomas Ashford, a man who had spent decades building a reputation as kind and gentle while privately being a monster.

By 1849, Jacob was 21 years old and looked 40.

His hair, once thick and dark, had started to thin.

His skin had a grayish tinge from lack of proper nutrition and constant stress.

He moved like an old man carefully, as if his bones might shatter.

His hands trembled constantly now.

He had developed a persistent cough that brought up blood sometimes.

The other servants whispered, “Something was wrong with Jacob.

He was sick.

He was cursed.

He was dying.

But no one said anything to Thomas because Thomas Ashford was a good man, a respected man.

And surely he had noticed his favorite servant was wasting away.

” Thomas had noticed.

But in his twisted mind, Jacob’s deterioration was romantic.

Proof of Jacob’s love for him.

You pine for me, he would say, stroking Jacob’s gaunt face.

I can see it.

When we’re apart, you waste away.

You need me, don’t you, Jacob? Yes, sir.

Jacob would respond automatically because agreeing was easier than explaining that he was dying.

That every day was a battle to simply continue existing, that he had thought about walking into the rice fields and never coming back, that the only thing keeping him alive was the absence of energy to kill himself.

In the spring of 1849, something happened that showed Jacob just how trapped he really was.

A new overseer was hired, a man named Daniel Pritchette.

He was young, perhaps 30, and unlike most overseers, he seemed to have some humanity left in him.

He noticed Jacob’s condition.

He saw the way the boy moved, the way he flinched at sudden movements, the way he looked more dead than alive.

One day, Pritchette pulled Jacob aside in the barn.

Boy, what’s happening to you? Jacob stared at him, too tired to even be afraid.

Nothing, sir.

Don’t lie.

You look like death walking.

Is someone hurting you? For a moment, just a moment, Jacob considered telling the truth.

But what would he say? That Thomas Ashford, the most respected man in the county, was raping him regularly.

Who would believe that? Who would care? No one is hurting me.

Pritchette studied him for a long moment.

If someone is, if Master Ashford is doing something to you, there are people who would help.

Jacob laughed.

It was a bitter, broken sound.

No one can help me.

No one would even try.

He walked away, leaving Pritchette staring after him with a troubled expression.

Two weeks later, Pritchette was fired.

Thomas told Jacob privately that the overseer had been asking inappropriate questions and spreading malicious rumors.

I protect what’s mine, Thomas said, his hand possessively on Jacob’s shoulder.

No one will come between us.

No one.

Jacob understood then.

If he hadn’t before, that escape was impossible.

Thomas had eyes everywhere.

Thomas controlled everything.

Jacob was completely, utterly, hopelessly trapped.

The trips continued.

Charleston, Savannah, Colombia, Richmond.

The same pattern every time, the same violation, the same violence, the same morning after praise and protestations of love.

But something was building in Jacob, something dark and desperate, a pressure that couldn’t be contained forever.

In April of 1850, they took another trip to Charleston.

Jacob was 22 now.

Thomas was 49.

They had been doing this for 5 years.

That night, in the hotel room, Thomas had drunk more than usual.

He was rough, rougher than he’d ever been before.

He brought out a riding crop where he’d gotten it.

Jacob didn’t know and didn’t ask.

He used it on Jacob’s back, his thighs, his chest.

The pain was extraordinary.

Jacob couldn’t dissociate through it.

He was forced to be present for every second of his degradation.

And the whole time Thomas was talking.

You like this, don’t you? I can tell.

You’re so beautiful when you’re like this.

You were made for me, Jacob.

Made for me? No.

Jacob had never been made for this.

He had never wanted this.

Not once in 5 years had he wanted any of it.

But he said nothing.

He just stared at the wall and felt something inside him crack.

When it was over, Thomas passed out drunk, snoring heavily.

Jacob lay there, his back striped with welts that would scar, and looked at the ceiling.

He could hear rain starting to fall outside.

He could hear Thomas snoring, and he thought very clearly, “I want to die.

” But he didn’t die.

He got up the next morning when Thomas called him.

He dressed Thomas.

He packed Thomas’s trunk.

He climbed into the carriage for the journey home, sitting on his wounded back, feeling the fabric of his shirt stick to the blood.

And he made a decision, not to die.

Not yet, but to live long enough to do one thing, to speak one word.

To say no.

If you’ve stayed with Jacob’s story this far, I need you to do something.

Don’t just listen.

Act.

Share this video.

Talk about abuse.

Believe victims when they come forward.

Because for every Jacob whose story we know, there are thousands whose stories die with them.

Hit that subscribe button.

Drop a comment.

Be part of making sure these stories matter.

Now, let’s continue to May 1850 to the moment when Jacob finally found his voice.

If you’ve stayed with this story this far, I need you to do me a favor.

Leave a comment below about what you think Jacob should do.

Because what happens next changes everything.

Hit that like button and let’s continue to May 1850.

It was a Tuesday night in May in a rented room in Savannah when Jacob finally spoke the word.

They had been traveling for 4 days.

Each night the same routine.

Each morning the same praise from Thomas.

But something was different in Jacob.

He could feel it building inside him like a storm.

5 years of silence.

5 years of compliance.

5 years of being told he wanted this when every cell in his body screamed that he didn’t.

That night, Thomas gave the order, “Undress and get in the bed.

” Jacob stood frozen, his hands didn’t move toward his buttons.

Thomas looked up from his seat by the window, mildly curious.

“Jacob,” I said.

Undress.

Jacob’s mouth opened.

His voice came out as barely a whisper.

“No.

” The room went silent.

Thomas stood up slowly, his expression one of complete bewilderment.

What did you say? Jacob’s hands were shaking so hard he had to clasp them together.

Tears were streaming down his face, though he hadn’t realized he was crying.

I said, “No, sir.

” Thomas walked toward him, his face shifting from confusion to concern.

“Jacob, are you unwell? Are you having one of your episodes? I don’t want to do this anymore.

” The words came out in a rush.

I never wanted to.

Please, please stop.

Thomas stopped walking.

For a long moment, he just stared at Jacob.

Then his expression changed.

The kindness drained out of his face like water from a broken glass.

What replaced it was cold, hard anger.

Do you understand what you’re saying to me? Yes, sir.

5 years, Jacob.

5 years we’ve had this understanding, this connection, and now you want to pretend you never wanted it.

Do you know what that makes you? I didn’t want it.

Jacob’s voice was stronger now.

I never wanted it.

You’re You’re hurting me.

You’ve been hurting me.

Thomas’s face flushed red.

I have given you everything.

I saved your worthless life.

I clothed you, fed you, took you places no one like you should ever see.

And this is how you repay me? With lies and ingratitude? I’m not lying.

Get out.

Thomas’s voice was a roar.

Get out of my sight.

Sleep in the hallway like the dog you are.

Jacob ran.

He spent the night curled up against the wall outside the room, shaking with fear and relief and something that might have been hope.

He had said no.

He had finally said no.

But the next morning he realized that saying no came with a price.

The journey back to Riverside Manor took 3 days.

Thomas didn’t speak a single word to Jacob.

Not one.

He sat in the comfortable part of the carriage while Jacob was relegated to the hard bench at the back, usually reserved for luggage.

When they stopped for the night at an inn, Thomas got a room.

Jacob was told to sleep in the stable.

When they arrived back at the plantation, Thomas summoned the overseer.

“Jacob is no longer to work in the house.

Put him in the fields, rice cultivation, and give him the quarter in the old slave house, the one with the rats.

” The overseer looked surprised.

“Sir, Jacob’s not built for field work.

He’ll Did I ask for your opinion?” “No, sir.

That afternoon, Jacob was moved from his small but clean room off the kitchen to a rotting shack at the far end of the slave quarters.

The building was ancient, barely standing, and yes, it was infested with rats.

There were six other slaves crammed into the space, all field workers who looked at Jacob with undisguised hatred.

The master’s pet brought low.

The next morning, Jacob was sent to the rice fields.

Rice cultivation was the most brutal work on the plantation.

The slaves worked kneede in water filled with snakes and alligators, their feet cut by sharp stubble, their backs bent for hours.

The son was merciless.

The overseer was worse.

Jacob, who had spent his entire life doing light household work, was completely unprepared.

By the end of the first day, his hands were bleeding.

His back was screaming.

He could barely stand.

By the end of the first week, he had collapsed twice.

The overseer had whipped him for it.

The master says, “You work same as everyone else.

No special treatment.

” Jacob’s food rations were cut.

He got half of what the other field slaves received.

He was literally starving.

His body, already thin, became skeletal.

In June, he caught his hand in a rice thresher.

Two of his fingers were crushed.

The plantation doctor wrapped them roughly and sent him back to work the next day.

Thomas didn’t even come to see him.

Jacob began to understand that Thomas was punishing him, not for being unwilling, but for exposing the lie Thomas had been telling himself.

Thomas had needed to believe Jacob wanted it.

Jacob’s refusal had shattered that illusion, and for that, Jacob had to be destroyed.

By August of 1850, Jacob was dying.

Everyone could see it.

He weighed perhaps 90 lb.

His crushed fingers had become infected and smelled of rot.

He coughed blood sometimes.

He could barely walk.

And then one evening in late August, a house servant came to the fields.

Jacob, the master wants to see you tonight in his study.

Jacob’s blood ran cold.

If you think you know where this is going, think again.

Hit that subscribe button because what happens next is going to shock you.

Let’s continue to that night in August.

Jacob stood outside Thomas Ashford’s study door that night, his hand raised to knock.

His crushed fingers throbbed with pain that seemed to pulse in time with his heartbeat.

His body achd with a deep bone level exhaustion that came from months of brutal labor and malnutrition.

He had no idea why he’d been summoned after months of silence and punishment.

Part of him hoped Thomas had finally had enough, that this would be the end.

Death at this point would be a mercy.

He knocked.

Come in.

Jacob opened the door.

The study looked exactly as it always had.

books lining the walls, their spines straight and perfect.

The mahogany desk that Jacob had polished a thousand times, the comfortable leather chairs where he’d sat as a child, learning numbers, feeling special.

Everything was the same, but everything had changed.

Thomas sat behind the desk, looking up from paperwork.

When he saw Jacob, his face broke into that familiar smile, that kind, fatherly smile that had once meant safety and now meant nothing but pain.

Jacob, sit down.

Jacob sat in the chair across from the desk, his body moved automatically, muscle memory from years of obedience.

He kept his eyes down, his hands folded in his lap.

He’d learned this posture in the rice fields.

Make yourself small.

Make yourself invisible.

Maybe they’ll forget you’re there.

You look terrible, Thomas said, and his voice actually sounded concerned, genuinely worried.

Have you been eating? Jacob stared at him in disbelief.

Was Thomas serious? He’d been the one to cut Jacob’s rations.

He’d been the one to assign him killing labor.

He’d been the one to move him to the ratinfested quarters.

And now he was asking if Jacob had been eating.

But Jacob said nothing.

Speaking would require energy he didn’t have.

Well, never mind that.

Thomas leaned back in his chair, steepling his fingers in that way he did when he was about to make an important point.

I’ve been thinking, Jacob, about what happened in Savannah.

I was angry.

I admit that I felt betrayed.

You telling me no after 5 years of of what we had together.

It hurt me deeply.

Jacob’s jaw clenched.

Hurt.

Thomas had been hurt.

Not Jacob whose body had been violated repeatedly.

Not Jacob who had been literally destroyed by months of punishment for the crime of refusing to be raped.

Thomas had been hurt.

“But I’ve prayed on it,” Thomas continued his expression earnest.

“I’ve consulted scripture.

I’ve sought guidance.

and I’ve realized something.

He leaned forward, his eyes bright with conviction.

You were scared.

It’s natural.

This thing between us, it’s powerful.

It’s intense.

And you’re still young.

You panicked.

You didn’t mean what you said.

I understand now.

Jacob’s hands clenched on the arms of the chair.

No, he had meant it.

He’d meant every word.

For the first time in his life, he’d told Thomas the truth, and Thomas had interpreted it as panic, as a mistake, as anything other than what it was, a clear, desperate final refusal.

“So, I’m willing to forgive you.

” Thomas’s smile widened.

“We can start over.

Things can go back to the way they were before.

You can move back into the house.

You can work in the study again.

We can take our trips to Charleston.

” His voice dropped, became intimate.

“I’ve missed you, Jacob.

The house isn’t the same without you.

My bed isn’t the same without you.

Jacob’s voice came out as a whisper.

It was all he could manage.

I meant what I said.

I don’t want to do that anymore.

The smile didn’t leave Thomas’s face, but something flickered in his eyes.

I’m not able to echo that passage exactly as written because it contains explicit sexual violence and coercion which I’m not allowed to reproduce verbatim.

If you’d like, I can instead summarize the scene in non-graphic terms, help you rewrite it to be less to be less explicit while keeping the emotional impact or discuss the themes power, abuse, trauma, etc.

in a more abstract way.

I’m not able to echo that text back exactly because it contains explicit sexual violence and coercion which I’m not allowed to reproduce verbatim.

I can help in other ways.

For example, by summarizing the passage in non-graphic terms, helping you rewrite it to be less explicit while keeping the same emotional impact or discussing the themes, abuse, power, complicity, trauma, etc.

that it raises.

His infected hand throbbed with a pain that radiated up his entire arm.

He had maybe days left, maybe hours.

He knocked on the study door with his good hand.

Come in.

Jacob entered.

The five men were already there, standing against the wall, naked, their faces blank, masks of resignation.

This was their life now, this nightly humiliation.

And it would continue until Jacob gave Thomas what he wanted or until Jacob died, whichever came first.

Thomas sat in his chair, already undressed, his body soft and pale in the lamplight.

He looked at Jacob, and his expression shifted to concern.

Jacob, you look awful.

Your hand, God, it’s gotten worse.

For a moment, genuine worry crossed his face.

If you would just, but this something was different in Jacob.

He looked at the five men.

He saw their shame, their suffering, their hatred of him.

He looked at Thomas, sitting there naked and expectant, convinced of his own righteousness, certain that everything he’d done had been justified by love.

And Jacob felt something he hadn’t felt in 5 years.

Not fear, not shame, not helplessness, not even despair.

Rage, pure, clean, crystalline rage that burned through the fever and the infection and the exhaustion.

These men were suffering because of Thomas.

Jacob was dying because of Thomas.

14 other years of Jacob’s life had been stolen because of Thomas.

And Thomas called it love.

Thomas believed it was love.

Thomas would die believing he had loved Jacob and that Jacob had loved him back.

And that lie, that fundamental lie at the heart of everything, was the one thing Jacob couldn’t let stand.

He turned to the five men.

His voice, when he spoke, was stronger than it had been in months.

It came from somewhere deep inside him, somewhere Thomas hadn’t been able to touch or break or destroy.

Get out.

The men looked at him like he’d lost his mind.

Thomas laughed, the sound indulgent and amused.

Jacob, you don’t give orders here.

YOU GET OUT.

JACOB’S VOICE WAS A roar that seemed to shake the walls.

It came from 14 years of silence.

It came from 5 years of rape.

It came from three months of watching other men suffer for his refusal to submit.

Get out now.

The five men looked at Thomas uncertain.

Thomas, too shocked to respond, immediately gave a tiny nod.

The men grabbed their clothes and fled, their bare feet slapping against the hardwood floor in their desperation to escape.

The door closed.

Jacob and Thomas were alone.

The silence that followed was absolute.

Thomas stared at Jacob, his expression shifting from shock to confusion to something that might have been fear.

Jacob walked across the room slowly, deliberately.

Each step was agony, with the fever burning through him, but he didn’t care.

He had one thing left to do, one final act of defiance.

One last truth to tell.

He began to undress.

He unbuttoned his shirt with his good hand, his ruined fingers hanging useless at his side.

He let the shirt fall to the floor, then his trousers.

He stood there in the lamplight and let Thomas see what he’d done.

Jacob’s body was a map of abuse.

Scars from the riding crop, bruises in various stages of healing, the outline of his ribs sharp under skin that was stretched too thin, his infected hand black and rotting, his legs covered in cuts from the rice fields, his back, which bore the marks of both Thomas’s passion and the overseer’s whip.

This was what love looked like to Thomas Ashford.

This destruction, this slow murder.

I knew it, Thomas breathed, his face lighting up with joy and relief.

I knew you still wanted me.

I knew you’d come back.

Oh, Jacob, I’ve missed you so much.

He was seeing what he wanted to see.

Even now, even faced with the physical evidence of what he’d done, he interpreted Jacob’s actions as desire, as love, as proof that everything between them was beautiful and right.

Jacob walked to the bed.

He climbed in.

He lay down on his back and stared at the ceiling, his body rigid, his mind clear and cold and certain.

[clears throat] I’m not able to repeat that text verbatim because it contains detailed sexual violence and abuse which I’m not allowed to reproduce exactly.

If you’d like, I can instead summarize the passage in neutral language, help you analyze the characters or themes, eg power, grooming, trauma, revenge, or help you rework it into something less graphic, but with similar emotional impact.

I’m not able to repeat that text verbatim because it contains detailed sexual abuse and suicide by firearm, which I’m not allowed to reproduce exactly.

I can help by, for example, summarizing the passage in neutral, non-graphic language, analyzing the themes, grooming, coercive control, victim blaming, revenge, justice, helping you reshape or edit it into a less graphic version that still carries the same emotional weight, or talking through the emotional impact it had on you.

If you tell me which of those you’d prefer, I’ll dive right in.

Thomas Ashford, 49 years old, patriarch of Riverside Manor, respected member of South Carolina society, lay dead in his bed.

Beside him, his personal servant, Jacob, 22 years old, also dead.

Between them, a hunting rifle.

There was blood.

So much blood.

The entire headboard was painted with it.

The pillows were soaked, the smell of gunpowder still hung in the air, and the way they were positioned.

Thomas on his back, Jacob on his side facing him.

The rifle angled between their heads, made it clear what had happened, even if no one wanted to believe it.

William, barely able to process what he was seeing, sent for the county sheriff.

While they waited, the household stood in stunned silence.

No one knew what to say.

No one knew how to make sense of this.

Margaret finally came to the doorway.

She looked at the scene for a long moment, her face completely blank.

Then she turned to William and said in a voice devoid of emotion, “Close the door.

We’ll wait for the sheriff in the parlor.

” The sheriff, when he arrived, was a man named Josiah Crawford, who had known Thomas Ashford for 20 years.

They attended the same church.

Their families socialized together.

Crawford looked at the scene and felt his world tilt.

What in God’s name happened here? No one could answer.

the rifle, the angle, the position of the bodies.

It suggested something so incomprehensible that Crawford’s mind refused to process it.

“There must have been an intruder,” he said finally.

“Someone broke in, killed them both, staged it to look like like, but even as he said it, he knew it wasn’t true.

There were no signs of forced entry.

Nothing was stolen.

” And the angle of the bullet.

Crawford had been a soldier once.

He understood ballistics.

The angle made it clear that this was no murder.

This was something else.

But what? A suicide pact between a master and his servant? Impossible, incomprehensible, unspeakable.

Margaret provided the narrative that everyone accepted because it was easier than the truth.

“Jacob must have been cleaning the rifle,” she said, her voice steady.

“It discharged accidentally.

The bullet killed my husband instantly.

” And Jacob, overcome with grief and horror at what he’d done, must have turned the gun on himself.

It didn’t make sense.

The angle was wrong.

The positioning was wrong.

The entire scenario was impossible.

But it was a story people could live with.

A story that preserved Thomas Ashford’s reputation.

A story that didn’t require anyone to ask uncomfortable questions about what might have been happening between a master and his servant behind closed doors.

Crawford wrote it up as an accidental death followed by a suicide.

The county coroner, who arrived later that morning, examined the bodies and signed the death certificates without argument.

No one wanted to look too closely.

No one wanted to see what might be there if they did.

They were buried separately, of course.

Thomas in the family cemetery with a grand headstone that read Thomas Ashford, 1801 to 1850.

Beloved husband, father, Christian.

Well done, good and faithful servant.

Jacob was buried at the edge of the property in an unmarked grave.

No headstone, no marker, nothing to indicate that a person was buried there at all.

The five enslaved men who had been forced to participate in Thomas’s nightly displays were sold off to different plantations within the week.

Margaret didn’t want any reminders.

She didn’t want anyone who might have seen something, who might have known something, who might have talked.

Within a month, it was as if the whole ugly business had never happened.

William and Henry Ashford, now 20 and 18, inherited the plantation.

William took over its management with the same cold efficiency his father had shown.

Henry went to Charleston to study law.

Neither of them ever spoke about Jacob again.

Neither of them ever asked what might have driven a servant to such a desperate act.

It was easier not to know, easier not to question, easier to accept the official story and move on.

In Charleston society, Thomas Ashford was remembered as a charitable man who had tried to help an unfortunate child and been repaid with tragedy.

A cautionary tale about the dangers of showing too much.

He tried to do good and look what happened.

No one ever knew the truth.

No one except Jacob.

And he took it with him to that unmarked grave.

But perhaps that’s not entirely true.

14 years later, in November of 1864, when Union troops swept through South Carolina during Sherman’s march to the sea, a young soldier from Massachusetts named Private Daniel Murphy was stationed at the ruins of what had once been Riverside Manor.

The main house had been burned.

The fields were overgrown.

The slave quarters were long abandoned.

Murphy, who had time to kill before his unit moved out, decided to explore the property.

He was looking for anything useful, anything valuable that might have been left behind.

Instead, near where the slave quarters had stood, he found something else.

A small wooden box partially buried in the dirt.

It was wellmade with a lock that had long since rusted through.

Murphy pried it open.

Inside was a scrap of paper yellowed with age with words scratched in charcoal in a shaky unpracticed hand.

My name was Jacob.

I was three years old when Thomas Ashford bought me.

He raised me.

He used me.

For 5 years he raped me and told me I wanted it.

I never wanted it.

I was never willing.

This is the truth.

My truth.

The truth they buried with me.

Thomas Ashford was not a good man.