The ledger was found in 1891 tucked beneath rotting floorboards of a burned plantation house in southern Georgia.

28 years after the transaction, the handwriting was meticulous.

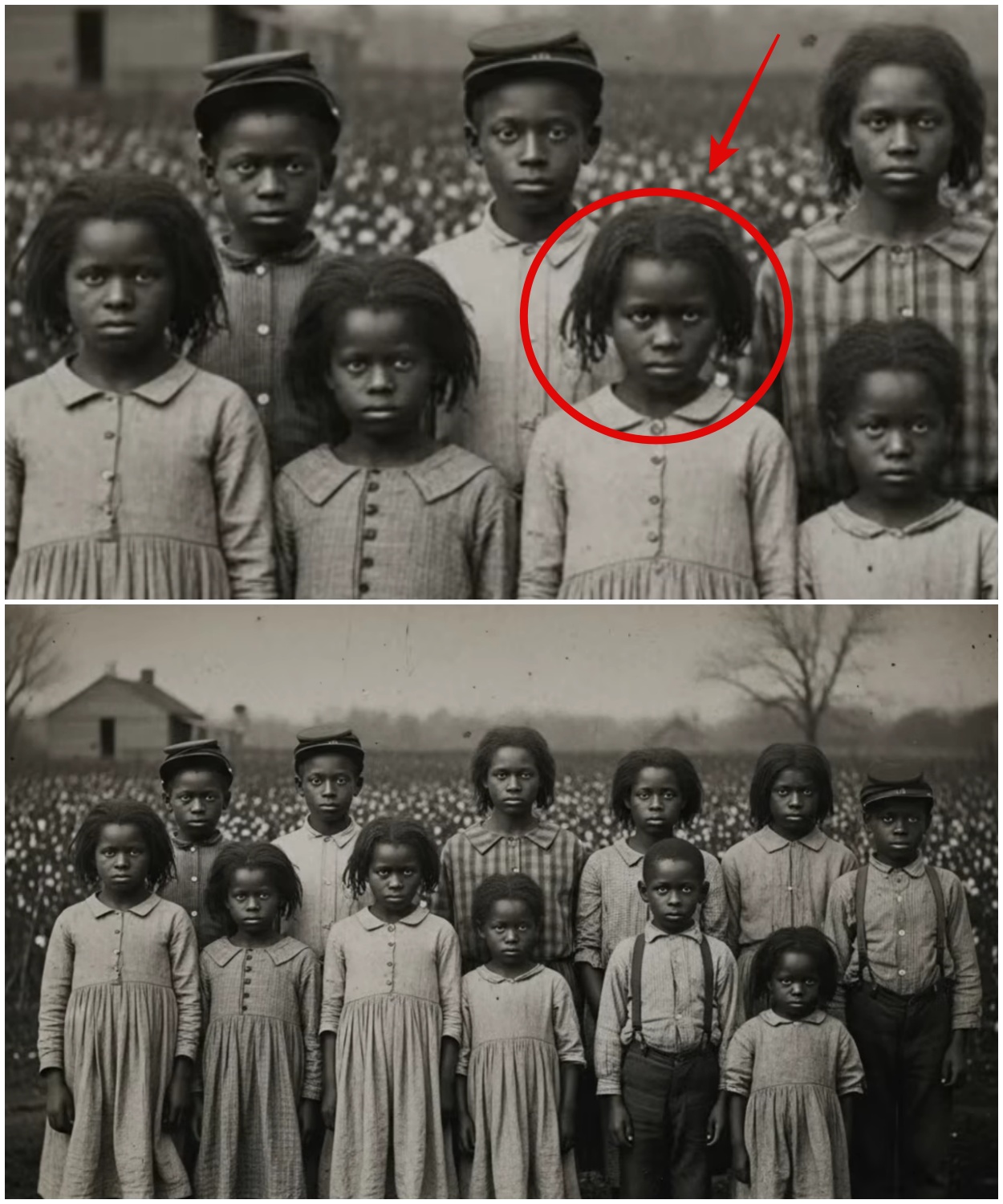

12 names, 12 ages ranging from 4 to 14.

12 prices totaling $8,400.

All sold on December 25th, 1863.

But it was the final entry that made the county clerk’s hands tremble.

A single word written in different ink in a shaking hand that barely resembled the previous entries.

Forgive what the authorities discovered in the days following that Christmas would challenge every assumption about justice, guilt, and the weight of a single night.

The master’s name was Silus Harrove, and by dawn on December 26th, something had changed him so profoundly that those who knew him claimed he was no longer the same man.

Some said it was divine retribution.

Others whispered of something far more terrifying, something that came for him in the darkness of that holy night when the world celebrated peace and he had committed an act so cruel that even hardened men turned away in disgust.

The truth buried in testimonies, letters, and the fragmented memories of those who survived is more disturbing than any legend.

Because what happened to Silus Harrove that night wasn’t supernatural.

It was entirely horrifyingly human.

And what makes this story even more chilling is that every detail can be traced back to documented records, witness accounts, and the physical evidence that remained long after everyone involved had turned to dust.

Now, let’s uncover what really happened on that Christmas night in 1863.

The Harg Grove plantation sat 7 miles south of Vald Dosta, Georgia on land that had been in the family since 1809.

By 1863, it was one of the few states in the region still operating at near full capacity despite the war that had been tearing the nation apart for nearly 3 years.

While other planters had lost their labor force to Union raids or Confederate conscription, Silas Hargrove had managed to keep his operation intact through a combination of brutal discipline and geographic isolation.

The plantation house itself was an imposing two-story structure with white columns that had long since grayed with neglect.

The paint peeled in long strips, revealing wood darkened by decades of humidity and heat.

Six windows faced the front yard, their glass warped with age, reflecting distorted images of anyone who approached.

The roof sagged slightly in the middle, and during heavy rains, water would drip through the ceiling of the second floor hallway, creating a rhythmic sound that echoed through the empty rooms.

Surrounding the main house were the quarters, 23 small cabins arranged in two rows, each housing multiple families.

The cabins were constructed of rough huneed pine logs chinkedked with mud and moss that had to be replaced every spring.

Each cabin measured roughly 12 by 14 ft and housed anywhere from 4 to eight people.

There were no windows, only wooden shutters that could be propped open during the day.

The floors were packed dirt and the roofs were made of cypress shingles that leaked during storms.

Beyond the quarters stood the cotton fields stretching toward a line of pine trees that marked the edge of Harrove land.

300 acres of cotton, though only about 200 were actively cultivated by 1863.

The soil was red clay, difficult to work, and the yields had been declining for years.

But Silas refused to acknowledge the decline, insisting in his ledgers that the land was as productive as it had been in his father’s time.

Between the fields and the quarters stood the work buildings, a cotton gin house, a blacksmith’s forge, a carpentry shop, a smokehouse, and a large barn that stored equipment and served as a punishment site when Silas deemed it necessary.

The gin house was the largest structure on the property aside from the main house, a cavernous building with a dirt floor and massive wooden gears that separated cotton fiber from seed.

The sound of the gin during harvest season was deafening, a constant grinding and clanking that could be heard for miles.

Silus Harrove was 47 years old in December of 1863.

He stood just under 6 ft tall with a thin frame that had grown thinner over the years.

His hair, once dark brown, had turned mostly gray, and he wore it combed straight back from a high forehead.

His face was angular, all sharp lines and prominent bones, with deep set eyes that rarely made direct contact with anyone.

He had a habit of pursing his lips when he was thinking, creating deep lines around his mouth that made him look perpetually disapproving.

Those who dealt with him in business described him as methodical, cold, and obsessed with maintaining control.

He kept detailed records of everything.

Crop yields, weather patterns, expenditures, and the names, ages, and estimated values of every enslaved person on his property.

His ledgers filled an entire bookshelf in his study, each one labeled by year and category.

He would spend hours reviewing them, making notations in the margins, calculating projections for future harvests.

But there was something else in those ledgers, something that wouldn’t be discovered until after his death.

Interspersed among the business entries were personal observations written in a smaller, more cramped handwriting.

Brief notes about the people he enslaved.

Ruth’s boy Marcus shows aptitude for carpentry.

Bess, age four, sickly, may not survive winter.

Thomas learning blacksmith trade, value increasing.

These weren’t compassionate observations.

They were assessments, the same way a farmer might note which livestock were thriving and which were failing.

Silas had been raised to view slavery as a natural order, an economic necessity, and a social structure ordained by God.

His father, Nathaniel Hargrove, had owned the plantation before him and had instilled in Silas a rigid worldview.

There were those who were meant to lead and those who were meant to serve.

Questioning this order was not only foolish but dangerous.

It threatened the entire foundation of their society.

Nathaniel had died in 1856, leaving the plantation to Silas, his only surviving son.

Silas’s older brother, James, had been killed in a hunting accident in 1849, and his younger brother, Robert, had died of yellow fever in 1852.

This left Silas as the sole heir, a responsibility he took with grim seriousness.

Silas had married in 1851 at the age of 35 to a woman named Catherine Brennan, the daughter of a wealthy merchant in Savannah.

It was not a love match, but a practical arrangement.

Catherine brought a substantial dowy, and Silas provided social standing and land.

They had four children in quick succession, two sons, William and Charles, and two daughters, Margaret and Anne.

Catherine was a quiet woman, deeply religious, who spent most of her time in the upstairs rooms of the house, reading scripture and writing letters to her family in Savannah.

She rarely ventured into the fields or the quarters, and she never questioned Silas’s management of the plantation.

But those who knew her said she seemed perpetually sad, as if she carried a weight she couldn’t name.

In 1859, Catherine became pregnant with their fifth child.

The pregnancy was difficult from the start.

She was weak, often bedridden, and by the 8th month, it was clear something was wrong.

On a cold night in November, she went into labor.

The baby, a boy, was born stillborn.

Catherine hemorrhaged and died 3 hours later at the age of 32.

Silas had her buried in the family cemetery, a small plot on a hill overlooking the cotton fields.

He commissioned a marble headstone with her name, dates, and a single line from Proverbs.

She openeth her mouth with wisdom, and in her tongue is the law of kindness.

He never visited the grave after the funeral.

The children were sent to live with Catherine’s sister in Savannah shortly after their mother’s death.

Silas told people it was for their education and safety, but those close to the family suspected the real reason.

He couldn’t bear to look at them.

They reminded him of Catherine, and Catherine reminded him of failure.

He had failed to protect her, failed to give her a life of happiness, failed to be anything more than a cold, distant husband.

With the children gone, Silas retreated further into his work.

He spent 18 hours a day managing the plantation, reviewing ledgers, planting crops, and maintaining the rigid control that defined his existence.

He ate alone, slept alone, and spoke only when necessary.

The enslaved families learned to avoid him when possible, to move quietly when he was near, to never meet his eyes.

His only regular companion was Dutch Keller, the overseer.

Dutch was a large man, over 6t tall and heavily muscled, with a thick red beard and small, cold eyes.

He had worked on the plantation since 1857, hired by Silas’s father shortly before Nathaniel’s death.

Dutch was efficient, brutal when he deemed it necessary, and utterly loyal to Silas.

He lived in a small house near the jin, separate from both the main house and the quarters, a physical representation of his position, above the enslaved, but below the master.

Dutch handled the day-to-day operations of the plantation, assigning work, distributing rations, maintaining discipline.

Silas trusted him completely, perhaps because Dutch never questioned orders and never showed any sign of moral conflict about the nature of their work.

To Dutch, enslaved people were tools, no different than plows or cotton gins.

You maintained them, you used them, and when they broke, you replaced them.

The winter of 1863 had been particularly harsh.

Frost came early in November, killing the last of the cotton bowls before they could be harvested.

By December, the ground was hard and unforgiving, and a thin layer of ice formed on the water barrels each morning.

The enslaved families huddled in their cabins at night, burning what little firewood they were allotted, trying to keep warm in structures that were never designed for comfort.

The cotton harvest had been the worst in a decade.

Silas calculated that he had lost nearly 40% of his expected yield.

The bales that were harvested were of poor quality, fetching lower prices at market, and the market itself was in chaos.

The Confederate dollar was nearly worthless.

Inflation was rampant, and creditors were demanding payment in gold or goods.

Silas was facing debts he couldn’t ignore.

He owed $3,200 to a bank in Savannah, $1800 to a cotton broker in Mon, and another $2,000 to various suppliers who had provided seed, equipment, and other necessities on credit.

In total, he was nearly $7,000 in debt with no clear way to pay.

He spent the first two weeks of December reviewing his options.

He could sell land, but land prices had collapsed due to the war.

He could sell equipment, but he needed the equipment to operate.

He could reduce his labor force, but he was already operating at minimum capacity.

And then on December 15th, he received a letter from Virgil Tate.

Tate was a slave trader based in Mon, one of the few still operating in Georgia in 1863.

Most of the slave trade had collapsed due to the war, but Tate had found a niche market, supplying labor to plantations in the deep south that had been spared the worst of the fighting.

He specialized in what he called future investments, young slaves who could be trained for specific tasks and would provide decades of labor.

The letter was brief and business-like.

Tate had heard that Silas was facing financial difficulties.

He was prepared to make a generous offer for young slaves, ages 4 to 14, paid in gold.

He would take as many as Silas was willing to sell, no questions asked, with payment on delivery.

Silas read the letter three times.

He sat in his study, staring at the words, calculating numbers in his head.

12 children.

If he sold 12 at an average price of $700 each, he would have $8 $400, enough to pay all his debts and have money left over for seed and supplies for the spring planting.

He told himself it was business, just business.

The children were eating food the plantation couldn’t spare.

They wouldn’t be productive for years.

Their parents would have more children.

It was a practical decision, a necessary decision.

It was what his father would have done.

He wrote back to Virgil Tate that same evening.

Agreeing to the sale.

12 children, ages 4 to 14, to be delivered on December 25th, Christmas Day.

Payment in gold on delivery.

He sealed the letter and gave it to Dutch to post the next morning.

Then he poured himself a glass of whiskey and returned to his ledgers, trying to ignore the small, persistent voice in the back of his mind that whispered he was making a mistake.

The selection process began on December 18th, exactly one week before Christmas.

Silas woke before dawn, as he always did, and spent an hour in his study reviewing the plantation records.

He had a list of all the children on the property, 37 in total, ranging in age from infants to 16 year olds.

He needed to choose 12.

The criteria were simple.

They had to be healthy, between 4 and 14 years old, and from families that wouldn’t cause too much trouble.

Silas knew that selling children would provoke grief and anger, but he calculated that some families would be easier to manage than others.

Families with multiple children would be less devastated by the loss of one.

Families with strong male figures might resist, so he would avoid taking their children if possible.

He made his preliminary selections on paper, writing 12 names in his ledger.

Then he called for Dutch.

Dutch arrived at the study just after sunrise, his breath visible in the cold morning air.

Silas showed him the list and explained the plan.

Dutch listened without expression, then nodded.

When do you want to tell them? Dutch asked.

Christmas Eve, Silas said.

No point in giving them time to make trouble.

They’ll make trouble anyway, Dutch said.

You’re taking their children.

Then we’ll deal with it, Silas said.

But the sale is happening.

Tate will be here Christmas morning with the gold.

Dutch nodded again and left.

Silas sat alone in his study, staring at the list of names.

12 children, 12 lives that would be uprooted, separated from their families, sold to strangers.

He felt a flicker of something, not quite guilt, but unease.

He pushed it down and returned to his calculations.

Over the next two days, Silas walked through the quarters and the work areas, observing the children on his list.

He watched them play, work, interact with their families.

He was looking for signs of illness, weakness, or behavioral problems that might reduce their value.

The first child on his list was Bess, a 4-year-old girl who lived with her mother, Sarah, and two older siblings in cabin number seven.

Bess was small for her age, with large, dark eyes and a quiet demeanor.

She rarely spoke, even to other children, and spent most of her time clinging to her mother’s skirts.

Silas noted that she appeared healthy despite her size, and her youth made her valuable.

She could be trained for domestic work and would provide decades of service.

The second was Marcus, a six-year-old boy who lived with his mother, Ruth, and his grandmother in cabin number 12.

Marcus was energetic and curious, always asking questions, always exploring.

Ruth was a strong woman, one of the most capable workers on the plantation, and Silas knew that taking her son would devastate her.

But Marcus was healthy, intelligent, and would fetch a good price.

The third was a girl named Lily, age seven, who lived with her parents and three younger siblings in cabin number three.

Lily helped her mother with the younger children, and was already learning to sew and cook.

She was quiet and obedient, traits that would make her valuable in a domestic setting.

The fourth was a boy named Samuel, age 8, who lived with his father, a blacksmith named Joseph, and his mother in cabin number 15.

Samuel was apprenticing with his father, learning the trade and showed considerable skill for his age.

Silas hesitated on this one.

Joseph was a strong, respected figure in the enslaved community, and taking his son might provoke resistance.

But Samuel’s skills made him valuable, and Silas decided the risk was worth it.

The fifth was a girl named Grace, age nine, who lived with her mother and two sisters in cabin number eight.

Grace was tall for her age, strong, and already working in the fields alongside the adults.

She rarely smiled, and there was a hardness in her eyes that Silas found unsettling.

But she was healthy and capable, and that was all that mattered.

The sixth was a boy named Daniel, aged 10, who lived with his parents and an older brother in cabin number 19.

Daniel was small and wiry with quick hands and a sharp mind.

He had been helping in the carpentry shop and showed aptitude for detailed work.

His parents were quiet, unlikely to cause trouble, which made him a safe choice.

The seventh was a girl named Hannah, aged 10, who lived with her mother and grandmother in cabin number five.

Hannah was cheerful and talkative, always singing while she worked.

Her mother, a woman named Esther, was one of the house servants, which meant Hannah had been exposed to domestic work from a young age.

She would be easy to train and valuable in a household setting.

The eighth was a boy named Isaac, age 11, who lived with his parents and three younger siblings in cabin number 21.

Isaac was serious and responsible, often taking care of his younger siblings while his parents worked.

He was literate.

His mother had secretly taught him to read using a Bible she had hidden.

Though Silas didn’t know this, Isaac’s intelligence and maturity made him valuable.

The ninth was a girl named Abigail, age 12, who lived with her mother and two younger brothers in cabin number nine.

Abigail was beautiful with delicate features and a graceful manner.

Silas knew that her appearance would make her valuable, though he didn’t allow himself to think too deeply about why.

She was quiet and obedient, unlikely to cause trouble.

The 10th was a boy named Elijah, aged 12, who lived with his parents and an older sister in cabin number 14.

Elijah was strong and hardworking, already doing a full day’s labor in the fields.

He rarely spoke, keeping his thoughts to himself, but there was an intensity in his eyes that made Silas uncomfortable.

Still, his strength and work ethic made him valuable.

The 11th was a girl named Rebecca, age 13, who lived with her mother and younger sister in cabin number six.

Rebecca was skilled in sewing and cooking, and she helped care for younger children in the quarters.

She was mature for her age with a quiet dignity that set her apart.

Her mother was a widow, which meant there would be no father to cause trouble.

The 12th was Thomas, age 14, who lived with his parents in cabin number 17.

Thomas was the oldest on the list, nearly a man, and he had been apprenticing with the plantation blacksmith for 3 years.

He was skilled, strong, and intelligent.

He was also the most likely to resist, but his value was too high to pass up.

12 children, four girls, eight boys, ages 4 to 14.

Silas wrote their names in his ledger in neat, precise handwriting along with estimated values based on age, health, and skills.

The total came to $8,400.

Exactly what Virgil Tate had agreed to pay.

Silas closed the ledger and locked it in his desk drawer.

The selection was complete.

Now he just had to wait until Christmas Eve to make the announcement.

The week leading up to Christmas was unusually quiet on the Harrove plantation.

The weather remained bitterly cold with temperatures dropping below freezing each night.

A thin layer of snow fell on December 20th, unusual for southern Georgia, and it lingered on the ground for 2 days before melting into muddy slush.

The enslaved families went about their work with the same efficiency as always, but there was a tension in the air that even Silas noticed.

People spoke in hushed tones.

Children played more quietly than usual.

There were no songs in the fields, no laughter in the quarters.

It was as if everyone sensed that something was coming, though they didn’t know what.

Silas spent most of his time in his study, reviewing his financial records and preparing for the transaction.

He had written to his creditors, informing them that he would be able to make payments in January.

He had calculated how much gold he would need to set aside for spring planting.

He had planned everything down to the smallest detail, but he couldn’t shake a growing sense of unease.

It started as a small, nagging feeling in the back of his mind, easy to ignore.

But as Christmas approached, it grew stronger, more insistent.

He found himself thinking about the children, not as assets or investments, but as individuals.

He remembered watching Bess cling to her mother’s skirts.

He remembered Marcus’s endless questions.

He remembered the way Thomas had looked at him once with an expression Silas couldn’t quite interpret.

He told himself he was being foolish.

This was business.

He had made the right decision.

The plantation would survive because of this sale.

That was all that mattered.

On December 22nd, Dutch came to the study with a concern.

Several of the enslaved families had been asking about Christmas.

Traditionally, Christmas was one of the few days when they were given a break from work and allowed to celebrate with extra rations and small gifts.

They wanted to know if the tradition would continue this year.

Silas considered the question.

Part of him wanted to cancel the celebration entirely.

It seemed hypocritical to give them a day of rest when he was about to sell 12 of their children.

But he also knew that cancelling Christmas would raise suspicions and might provoke resistance before the sale could be completed.

Tell them Christmas will be observed as usual, Silas said.

Extra rations on Christmas Eve.

No work on Christmas Day.

Dutch nodded and left.

Silas returned to his ledgers, but he couldn’t concentrate.

He kept thinking about the announcement he would have to make on Christmas Eve.

He imagined the mother’s faces when they heard their children’s names.

He imagined the father’s rage.

He imagined the children’s confusion and fear.

He poured himself a glass of whiskey, even though it was only midafter afternoon.

Then another.

By evening, he had finished half the bottle and fallen asleep at his desk.

He dreamed of Catherine.

She was standing in the upstairs hallway of the house wearing the white dress she had been buried in.

She was looking at him with an expression of profound sadness and she was holding a baby, the stillborn son who had killed her.

She didn’t speak, but her eyes said everything.

What have you become? Silas woke with a start, his heart pounding.

The study was dark, the fire in the hearth reduced to glowing embers.

He lit a lamp and checked his pocket watch.

It was just after midnight, December 23rd, 2 days until the sale.

He stood and walked to the window, looking out at the quarters.

A few cabins had lights in the windows, candles or small fires.

Most were dark.

He wondered if the families were sleeping or if they were lying awake, sensing the approaching storm.

He turned away from the window and went upstairs to his bedroom.

He didn’t sleep for the rest of the night.

December 23rd passed slowly.

Silas stayed in his study, avoiding the quarters, avoiding Dutch, avoiding everyone.

He reviewed the transaction papers Virgil Tate had sent, making sure everything was in order.

He counted and recounted the estimated value of the children.

He tried to focus on the numbers, the logic, the necessity of what he was doing.

But the unease wouldn’t leave him.

It had grown into something more than discomfort.

It was a physical sensation, a tightness in his chest, a weight pressing down on him.

He found it difficult to breathe.

His hands shook when he tried to write.

He couldn’t eat.

That evening, he walked out to the family cemetery on the hill.

He hadn’t been there since Catherine’s funeral 4 years earlier.

The headstone was weathered, but still legible.

He stood in front of it, staring at the inscription, and tried to remember what it had felt like to care about someone.

He couldn’t.

That part of him seemed to have died with Catherine, or perhaps even before.

He had spent so many years viewing people as assets, as tools, as numbers in a ledger that he had forgotten how to see them as anything else.

He returned to the house as darkness fell.

Tomorrow was Christmas Eve.

Tomorrow he would make the announcement, and the day after the children would be gone, and he would have his gold, and everything would go back to normal.

He almost believed it.

December 24th, 1863 dawned cold and gray.

The sky was overcast, threatening more snow, and a bitter wind blew from the north.

Silas woke early as always, but he didn’t go to his study.

Instead, he stood at his bedroom window, looking out at the quarters, watching as smoke began to rise from the chimneys as families woke and started their fires.

He knew what he had to do today.

He had rehearsed the words in his mind a hundred times.

He would be brief, direct, unemotional.

He would read the names from his ledger.

He would tell them the children would be leaving at dawn.

He would make it clear that resistance would be punished.

It would take 5 minutes, maybe less, and then it would be done.

But as he stood at the window, watching the plantation wake up, he felt something he hadn’t felt in years.

Fear.

Not fear of the enslaved family’s reaction, though that was a concern, but a deeper fear, a primal dread that he couldn’t name or explain.

It felt like standing at the edge of a cliff, knowing that one more step would send him plummeting into darkness.

He pushed the feeling down and got dressed.

He went to his study and retrieved the ledger with the 12 names.

He called for Dutch and told him to gather everyone in the yard at dusk for the rations distribution.

Dutch nodded and left without comment.

The day passed with agonizing slowness.

Silas tried to work, but he couldn’t focus.

He tried to read, but the words blurred on the page.

He tried to eat, but the food tasted like ash.

He spent most of the day sitting in his study, staring at the ledger, waiting for dusk.

In the quarters the families prepared for Christmas.

Despite the cold and the hardships of the past year, there was a sense of anticipation.

Christmas was one of the few days when they were allowed to rest, to be with their families, to pretend for just a moment that they were something more than property.

The mothers cooked what little extra food they had been given.

The fathers told stories to their children.

The older children helped care for the younger ones.

There was singing in some of the cabins, hymns and spirituals that had been passed down through generations.

Ruth, Marcus’s mother, held her son close as she prepared their meager Christmas meal.

Marcus was excited, chattering about what he hoped to receive.

Maybe an extra piece of cornbread or a small toy carved from wood.

Ruth smiled and stroked his hair, trying to memorize the feel of him, the sound of his voice, the warmth of his small body against hers.

She didn’t know why, but she had a terrible feeling that something was wrong.

She had felt it for days, a growing dread that she couldn’t shake.

She had dreamed the night before of Marcus walking away from her into darkness, and no matter how loudly she called, he didn’t turn back.

She held him tighter and whispered a prayer.

As dusk approached, Dutch walked through the quarters, calling for everyone to gather in the yard for rations.

The families emerged from their cabins, bundled against the cold, and assembled in front of the big house.

There were 63 people in total, men, women, and children, representing 23 families.

Silas stood on the porch, the ledger in his hands.

Dutch stood beside him, his face expressionless.

The enslaved families waited in silence, their breath visible in the cold air.

Silas opened the ledger.

His hands were shaking, and he gripped the book tighter to steady them.

He looked out at the assembled faces, faces he had seen every day for years, faces he had never truly looked at.

“I have an announcement,” he said.

His voice sounded strange to his own ears, thin and distant.

The crowd waited.

Silas looked down at the ledger and began to read the names.

Bess, Marcus, Lily, Samuel, Grace, Daniel, Hannah, Isaac, Abigail, Elijah, Rebecca, Thomas.

12 names.

As each name was called, a ripple of confusion passed through the crowd.

Parents looked at each other trying to understand.

Children looked up at their mothers and fathers, sensing something was wrong.

“These children have been sold,” Silas continued, his voice flat.

They will be leaving at dawn tomorrow.

The buyer will arrive with a wagon.

The transaction is final.

Anyone who interferes will be punished.

For a moment, there was absolute silence.

The words hung in the cold air, incomprehensible, and then slowly the meaning sank in.

The first sound was a gasp, a sharp intake of breath from one of the mothers.

Then another, and then the wailing began.

It started with Ruth.

She let out a sound that was barely human.

A howl of grief so profound that it seemed to tear the air itself.

She fell to her knees, clutching Marcus to her chest, and the sound that came from her was the sound of a soul breaking.

Other mothers joined her.

Sarah, Bess’s mother, collapsed, her body shaking with sobs.

Esther, Hannah’s mother, screamed and reached for her daughter, pulling her close.

The fathers stood rigid, their faces carved from stone, their fists clenched at their sides.

The children began to cry, not understanding what was happening, but sensing their parents’ terror.

Bess clung to her mother, her small body trembling.

Marcus buried his face in Ruth’s shoulder.

Thomas stood apart from his parents, his face blank, his eyes fixed on Silus.

Ruth crawled forward on her knees, her hands outstretched, her face wet with tears.

She reached the porch steps and looked up at Silas, her voice breaking.

“Please,” she said.

“Please, Master Hargrove, don’t take my boy.

He’s all I have.

Please, I’ll work harder.

I’ll do anything.

Please don’t take him.

” Silus looked down at her.

He saw the desperation in her eyes, the absolute terror.

He saw Marcus clinging to her, his small face pressed against her neck.

And for a moment, just a moment, he felt something crack inside him.

But then he remembered the debts, the creditors, the plantation, the necessity of survival.

He hardened his expression and said the words that would haunt him for the rest of his life.

He’s worth more than you.

Ruth’s face crumpled.

She let out another whale and collapsed onto the frozen ground, her body racked with sobs.

Other mothers surged forward, begging, pleading, offering anything and everything if he would just spare their children.

Silas turned and walked into the house.

He locked the door behind him and stood in the dark hallway, listening to the sounds of grief outside.

The wailing continued for hours, a sound so terrible that it seemed to seep into the walls of the house, into the very foundation.

He went to his study and poured himself a glass of whiskey, then another.

He tried to block out the sounds, but they followed him, echoing in his mind.

He sat at his desk and stared at the ledger, at the 12 names written in his neat handwriting.

“Just business,” he told himself.

“Just business.

” But the words felt hollow.

Outside in the quarters, the families held their children.

They sang to them, whispered prayers, made promises they knew they couldn’t keep.

They tried to memorize every detail.

the shape of their faces, the sound of their voices, the feel of their small hands.

Ruth held Marcus all night, rocking him, singing softly.

Marcus had stopped crying and was quiet now, his small body warm against hers.

She whispered to him about how much she loved him, about how he needed to be strong, about how she would never forget him.

“Will I see you again, mama?” Marcus asked, his voice small.

Ruth couldn’t answer.

She just held him tighter and continued to sing.

In cabin number 17, Thomas sat with his parents.

His father, a strong man named Jacob, had his hand on Thomas’s shoulder.

His mother, a woman named Miriam, held his hand.

They didn’t speak.

There was nothing to say.

Thomas looked at his parents and felt something harden inside him.

He was 14 years old, nearly a man, and he understood what was happening in a way the younger children didn’t.

He understood that tomorrow he would be taken from his family and sold to a stranger.

He understood that he would likely never see his parents again.

He understood that his life, his future, his very identity was being erased because a white man needed money.

And he understood that there was nothing he could do about it.

But as he sat there holding his mother’s hand, feeling his father’s grip on his shoulder, he made a silent promise.

He would survive.

He would remember.

And someday, somehow, he would make sure that what was being done to him and the other children would not be forgotten.

The night deepened.

The temperature dropped.

The wailing in the quarters gradually subsided into quiet sobbing, and then into silence.

But it was not a peaceful silence.

It was the silence of grief too profound for words, of hearts breaking in the darkness.

In the big house, Silas sat alone in his study.

He had finished the bottle of whiskey and started another.

His mind was foggy, his thoughts disjointed.

He kept seeing Ruth’s face, hearing her voice.

Please don’t take my boy.

He stood and walked to the window.

The quarters were dark now, no lights in the windows.

He wondered if anyone was sleeping or if they were all lying awake, holding their children, counting down the hours until dawn.

He turned away from the window and was about to return to his desk when he heard it.

A knock at the door.

Three soft, deliberate strikes.

Silas froze.

It was just after midnight.

Who would be knocking at this hour? He assumed it was Dutch, perhaps with news about the arrival time or a concern about potential resistance.

He walked through the dark hallway to the front door and opened it.

No one was there.

The porch was empty.

The yard beyond was still, illuminated by a half moon that cast long shadows across the frozen ground.

Silus stepped outside, his breath visible in the cold air.

He looked left, then right.

Nothing.

He was about to go back inside when he saw them.

12 figures standing at the edge of the yard where the grass met the dirt path leading to the quarters.

Small figures, children.

For a moment, Silas thought the enslaved families had sent the children to plead for themselves.

He felt a surge of anger.

This was manipulation, an attempt to make him feel guilt.

He stepped off the porch and started toward them, ready to send them back and punish whoever had orchestrated this.

But as he got closer, he realized something was wrong.

The children weren’t moving.

They stood perfectly still, arranged in a line, their faces tilted upward toward the house.

And they were silent.

Completely unnaturally silent.

No crying, no pleading, no sound at all.

Get back to the quarters, Silus said, his voice sharp.

Now, none of them moved.

He was 10 ft away when he recognized them.

Bess, the four-year-old, her small body rigid.

Marcus, Ruth’s son, his face blank.

Thomas, the blacksmith’s apprentice, his eyes fixed on Silas.

All 12 children from the list, standing in the exact order he had written their names in the ledger.

I said, “Get back,” Silas repeated.

“Louder now.

” His voice echoed in the stillness.

The children didn’t respond.

They didn’t blink.

They simply stared at him with expressions he couldn’t read.

Not fear, not defiance, but something else.

Something that made his skin prickle despite the cold.

And then slowly they began to move.

Not toward him, not away.

They simply turned in perfect unison and started walking toward the cotton fields.

Silas stood frozen, watching them disappear into the darkness beyond the reach of the moonlight.

His heart was pounding, though he couldn’t explain why.

They were just children, enslaved children who would be gone by noon tomorrow.

This changed nothing.

But as he stood there in the cold, watching the darkness where they had vanished, he felt that fear again, the primal dread that had been growing all day.

It was stronger now, almost overwhelming.

He went back inside, locked the door, and returned to his study.

He poured another glass of whiskey and tried to steady his shaking hands.

“Just children,” he told himself.

just a trick to make me feel guilty.

It won’t work.

But he couldn’t shake the image of their faces, the way they had stared at him, the absolute silence, the way they had moved in perfect unison, as if controlled by a single mind.

He tried to return to his ledger, but the numbers blurred.

He tried to sleep, but every time he closed his eyes, he saw them standing in that line, their small bodies rigid, their eyes fixed on him.

At 2:00 in the morning, he heard singing.

If you’re feeling the weight of this story, imagine how those families felt on that Christmas Eve.

Before we continue to the most disturbing part of this night, take a moment to like this video and share it with someone who appreciates true historical mysteries.

Your support helps us bring these forgotten stories to light.

Now, let’s discover what happened when Silas heard that singing in the darkness.

The singing was faint at first, barely audible over the wind that rattled the windows of the big house.

It seemed to come from everywhere and nowhere at once.

A melody that Silas didn’t recognize, sung in voices too young to carry such weight.

The tune was slow, mournful, with a rhythm that felt wrong, discordant, like a hymn sung backward, or a lullaby twisted into something dark.

Silas stood in his study, the whiskey glass frozen halfway to his lips.

He listened, trying to determine where the sound was coming from.

It seemed to drift through the walls like smoke, seeping into every corner of the house.

He went to the window and looked out.

The yard was empty.

The quarters were dark, but the singing continued rising and falling in waves that made his chest tighten.

He grabbed his coat and a lantern and went outside.

The moment he stepped off the porch, the singing stopped.

The silence that followed was worse.

It was total oppressive, as if the world itself had stopped breathing.

No wind, no insects, no distant sounds of animals in the woods, no creaking of trees or rustling of leaves, just silence, so complete that Silus could hear his own heartbeat pounding in his ears.

He held the lantern high and walked toward the quarters.

His boots crunched on the frozen ground, each step unnaturally loud in the stillness.

He expected to find the families awake, perhaps gathered in one of the cabins, perhaps singing to comfort themselves.

But every door was closed, every window dark.

He knocked on the nearest door, cabin number seven, where Bess lived with her mother Sarah.

No answer.

He knocked again, harder.

Still nothing.

He pushed the door open.

Inside, Sarah lay on a pallet with her two older children, all three of them asleep, but it wasn’t a normal sleep.

Their breathing was shallow, almost imperceptible, and they didn’t stir when Silas called out.

He moved closer and shook Sarah’s shoulder.

She didn’t wake.

Her skin was warm, her pulse steady, but she was completely unresponsive, as if trapped in some deep, unnatural slumber.

Silas backed out of the cabin, his heart racing.

He moved to the next cabin, then the next, the same in each one.

Every adult, every child except the 12 he had selected was asleep in this same deep, unnatural way.

He called their names, shook them, even splashed water on their faces.

Nothing worked.

They simply lay there breathing shallowly, trapped in sleep.

Except the 12 children.

The 12 children were gone.

Silus felt the first real thread of panic.

He told himself it was absurd.

They were hiding, playing some kind of game.

Or perhaps their parents had hidden them before falling into this strange sleep.

But the panic remained, cold and insistent, spreading through his chest like ice water.

He searched the quarters, the barn, the storage sheds, the gin house, nothing.

He walked to the edge of the cotton fields, holding his lantern high, and called their names.

His voice was swallowed by the darkness, as if the night itself was absorbing the sound.

And then he saw the light.

Deep in the fields, perhaps a 100 yards away, a small fire burned.

It was low to the ground, flickering weakly, but unmistakable against the darkness.

Silas started toward it, his boots crunching on the frozen earth, his breath coming in short gasps.

As he got closer, he saw them.

The 12 children sat in a perfect circle around the fire.

They weren’t moving, weren’t speaking.

They simply sat.

Their faces illuminated by the flames, staring into the fire as if hypnotized.

The light cast strange shadows on their faces, making them look older, almost ancient.

“What are you doing?” Silus demanded, his voice breaking the silence.

Get up.

Get back to the quarters now.

None of them looked at him.

They continued to stare into the fire, their expressions blank.

He stepped closer, anger overriding fear.

I said, “Get up.

” One of the children, Thomas, the oldest, finally turned his head.

His eyes met Silus’s, and for the first time, the boy spoke.

“We’re waiting.

” His voice was calm, almost conversational, but there was something underneath it that made Silas’s skin crawl.

“Waiting for what?” Silas snapped.

Thomas didn’t answer immediately.

He simply looked at Silas with an expression that was neither hostile nor afraid.

“It was something else, something that looked almost like pity.

” “For you to see us,” Thomas said quietly.

“I see you,” Silas said.

“You’re sitting in my field in the middle of the night.

Now get up before I No, Thomas interrupted.

You don’t see us.

You’ve never seen us.

Not really.

Silus felt his anger spike.

I don’t have time for this nonsense.

Get up now.

He reached down and grabbed Thomas’s arm, intending to drag him to his feet.

But the moment his hand made contact, Thomas looked up again.

And this time, his expression was different.

Not blank, not empty, but filled with something Silas couldn’t name.

A depth of understanding that no 14-year-old should possess.

“You sold us,” Thomas said quietly.

“On Christmas.

” The words hit Silus like a physical blow.

He released the boy’s arm and stepped back.

“It’s business,” Silas said, but his voice sounded weak, even to himself.

“You don’t understand.

It’s just business.

I have debts.

the plantation.

“We understand,” Thomas said, and then in a voice that didn’t sound like a 14-year-old boy, he added, “do you.

” The fire went out, not gradually, not flickering and fading.

It simply vanished as if someone had thrown a blanket over it.

The darkness rushed in, absolute and suffocating.

Silas’s lantern was still burning, but its light seemed to stop just inches from the glass, unable to penetrate the blackness around him.

He heard movement, footsteps, whispers.

The children were standing now.

He could sense it, but he couldn’t see them.

He swung the lantern wildly, trying to find them, but the light revealed nothing but darkness.

And then he felt it.

hands.

Small hands, dozens of them touching him.

Not grabbing, not violent, just touching his arms, his chest, his face.

Cold fingers pressing gently against his skin as if trying to memorize him, to understand him.

Silas screamed.

He swung the lantern and it shattered against the ground, plunging him into complete darkness.

He ran blindly, stumbling over frozen furrows, his breath coming in ragged gasps.

He didn’t know which direction he was going.

He only knew he had to get away.

The hands followed him.

They touched his back, his shoulders, his neck.

Light touches almost gentle but relentless.

And with each touch, he felt something, a flash of emotion, a fragment of memory that wasn’t his own.

He felt terror.

The terror of a 4-year-old child being torn from her mother’s arms.

He felt confusion.

the confusion of a six-year-old boy who didn’t understand why he was being taken away.

He felt grief.

The grief of a mother watching her child disappear into darkness.

He felt rage.

The rage of a father who couldn’t protect his family.

He felt despair.

The despair of children who had been told they were worthless, that they were property, that their lives had no value beyond what someone was willing to pay.

Each emotion hit him like a wave, overwhelming, suffocating.

He tried to push them away to block them out, but they kept coming faster and faster until he couldn’t tell where his own feelings ended and theirs began.

He ran until his legs gave out, and he collapsed onto the frozen ground, gasping, his heart hammering in his chest.

The hands were gone, the darkness was gone.

He was lying in the yard in front of the big house and the sky was beginning to lighten with the first hint of dawn.

He opened his eyes and saw them.

The 12 children standing on the porch watching him.

They didn’t speak.

They didn’t move.

They simply stood there silent and still as the sun began to rise behind them.

Silas staggered to his feet, his body shaking, his mind reeling.

He stumbled into the house, locked the door, dragged a chair against it, and collapsed onto the floor of his study.

His clothes were torn, his hands bleeding from where he had fallen.

His face was wet, whether from tears or sweat or melted snow, he didn’t know.

He sat there for a long time trying to make sense of what had happened.

It was exhaustion, he told himself.

Stress, guilt manifesting as hallucination.

It wasn’t real.

It couldn’t be real.

But when he looked down at his hands, he saw the dirt under his nails, the scratches on his palms, and when he looked at the window, he saw them still standing there watching.

And he knew with a certainty that terrified him that it had been real, all of it.

At precisely 6:00 in the morning, Virgil Tate arrived with his wagon and three armed men.

Silas heard the sound of hooves and wheels on the frozen road and forced himself to stand.

His body achd, his head pounded, and his hands wouldn’t stop shaking.

He looked at himself in the mirror above his desk and barely recognized the man staring back.

His face was pale, his eyes bloodshot and sunken, his hair disheveled.

He looked like he had aged a decade overnight.

He straightened his clothes as best he could and walked to the front door.

He took a deep breath, trying to steady himself, and opened it.

Virgil Tate was a large man, over 6t tall and heavily built, with a thick black beard and cold, calculating eyes.

He wore a long coat and a wide-brimmed hat, and he carried himself with the confidence of a man who had done this transaction a 100 times before.

Behind him, three men sat on the wagon, all armed with rifles, all watching Silas with expressions of bored indifference.

“Harrove,” Tate said, his voice gruff.

“You have them ready?” Silas opened his mouth to respond, but no words came out.

He looked past Tate to the yard where the 12 children still stood in a line, exactly as they had been, waiting.

But something was different now.

In the growing light of dawn, he could see their faces clearly, and what he saw made his breath catch in his throat.

They weren’t blank anymore.

They weren’t empty.

Their eyes were filled with something he finally recognized.

Something he had been too blind to see before.

Humanity.

They were children.

Just children.

Children who were terrified, confused, grieving.

Children who had families, who had dreams, who had futures that were being stolen from them.

Children who were exactly like his own sons and daughters, except for the color of their skin and the accident of their birth.

And he was about to sell them on Christmas morning for gold.

“Well,” Tate said impatiently, “let’s done.

I have another stop in Thomasville.

” Silas looked at the children, at Bess, the four-year-old, her small body trembling.

At Marcus, Ruth’s son, his eyes wide with fear.

At Thomas, the blacksmith’s apprentice, who was looking at him with that same expression of understanding, of pity.

And in that moment, Silas Hargrove understood something that would haunt him for the rest of his life.

They knew.

They knew exactly what he was.

They knew what he had chosen.

And they knew that he would have to live with it.

The weight of that knowledge was crushing.

It pressed down on him, suffocating him.

And he realized that this was what they had shown him in the darkness.

Not revenge, not punishment, but truth.

The simple unbearable truth of what he was doing.

He thought about the gold, about the debts, about the plantation, about everything he had told himself to justify this decision.

And he realized that none of it mattered.

None of it was worth this.

“No,” Silas said quietly.

Tate frowned.

“What?” “No,” Silas repeated louder now.

His voice was shaking, but there was a firmness underneath it that surprised even him.

“The sail is off.

Tate’s expression darkened.

The hell it is.

We have a contract.

I have your signature.

You take this gold or I take those children and you get nothing.

Silas looked at the leather satchel in Tate’s hand.

The satchel containing $8,400 in gold coins.

Enough to save the plantation.

Enough to pay his debts.

Enough to secure his future.

Then he looked at the children again.

at their faces, at their eyes.

“Take your gold and leave,” Silas said.

Tate stared at him for a long moment, his jaw clenched.

“You’re a fool, Hargrove.

You’ll lose everything.

” “I know,” Silas said.

And he did.

He knew that without the gold, he would default on his debts.

The creditors would seize the plantation.

He would lose everything his family had built over three generations.

He would be ruined.

But he also knew that if he went through with this sale, he would lose something far more important.

He would lose whatever remained of his humanity.

He would become something he could never come back from.

Tate spat on the ground.

Your funeral.

He turned to his men.

Let’s go.

We’re wasting time here.

The wagon turned and started back down the road.

The sound of hooves and wheels faded into the morning.

Silas stood on the porch watching them disappear and felt something inside him break and reform at the same time.

He looked at the children.

Slowly, one by one, they turned and walked back toward the quarters.

By the time the sun was fully up, they were gone.

Silas stood on the porch for a long time after the children left, staring at the empty yard.

The sun was rising, casting long shadows across the frozen ground, and the world was beginning to wake up.

He could hear sounds from the quarters now, doors opening, voices calling out the normal sounds of morning.

He realized that whatever had happened during the night, whatever strange sleep had fallen over the plantation was over.

The families were waking up and they would want answers.

Silas went inside and walked to his study.

He sat at his desk and stared at the ledger, at the 12 names written in his neat handwriting.

He picked up his pen, dipped it in ink, and drew a single line through each name.

Then at the bottom of the page, he wrote three words.

Sale canled.

Debt remains.

He closed the ledger and locked it in his desk drawer.

Then he stood and walked back outside.

The families were emerging from the quarters now, confused and disoriented.

They had woken to find themselves in their cabins with no memory of how they got there or what had happened during the night.

The last thing they remembered was the announcement on Christmas Eve.

The grief, the wailing, the terror of knowing their children would be taken at dawn.

But dawn had come and their children were still there.

Ruth was the first to see Marcus.

He was standing outside their cabin, looking tired and confused, but unharmed.

She ran to him and swept him into her arms, sobbing, checking him for injuries, unable to believe he was really there.

Other mothers did the same, finding their children, holding them, weeping with relief and confusion.

The children couldn’t explain what had happened.

They remembered standing in the yard, remembered walking to the fields, remembered sitting around a fire, but after that, everything was blank until they woke up at dawn.

Dutch Keller emerged from his house near the gin, looking as confused as everyone else.

He had fallen asleep at his desk the night before and woken to find it was Christmas morning.

He walked to the big house and found Silas standing on the porch.

“What happened?” Dutch asked.

“Where’s Tate? Did the sale go through?” “No,” Silas said.

“I canceled it.

” Dutch stared at him.

“You what?” “I canceled the sale,” Silas repeated.

The children are staying, but the debts.

I’ll figure it out, Silus said.

His voice was flat, emotionless.

But there was a finality to it that made Dutch realized there was no point in arguing.

Dutch shook his head.

You’ve lost your mind.

Maybe, Silus said.

Or maybe I just found it.

Dutch left, muttering under his breath.

Silas remained on the porch, watching as the families slowly realized what had happened.

The children weren’t being taken.

They were safe.

It was Christmas morning and they were still together.

The relief was palpable, but so was the confusion.

No one understood what had changed.

No one knew why Silas had canled the sale, and no one dared to ask.

Silas spent the rest of Christmas Day alone in his study.

He didn’t eat.

He didn’t sleep.

He simply sat at his desk, staring at the ledger, replaying the events of the night over and over in his mind.

The children in the yard, the fire in the fields, the hands in the darkness, the emotions that had overwhelmed him.

Terror, confusion, grief, rage, despair.

He had felt what they felt.

He had experienced for just a moment what it was like to be them.

to be powerless, to be property, to be seen as less than human, and it had broken something in him that could never be repaired.

The days following Christmas of 1863 were marked by a strange, heavy silence on the Harrove plantation.

The enslaved families returned to their work, but something had shifted.

They moved through their tasks with the same efficiency, but there was a new quality to their presence, a quiet dignity, a sense of having witnessed something that couldn’t be undone.

Silus Hargrove did not leave the big house for 3 days.

Dutch Keller tried to speak with him on December 27th, knocking on the study door and asking about the plantation’s operations.

Silas didn’t respond.

Dutch could hear him inside moving around, but the door remained locked.

On the 28th, Dutch left a tray of food outside the door.

It sat there untouched until the 29th when Silas finally emerged.

Those who saw him said he looked like he had aged a decade.

His face was gaunt, his eyes sunken and red- rimmed with dark circles that spoke of sleepless nights.

His hands trembled when he tried to hold a pen.

His clothes hung loosely on his frame as if he had lost weight in just a few days.

He didn’t speak to anyone.

He simply walked through the plantation, stopping occasionally to stare at the quarters, the fields, the places where the children played.

On December 30th, he did something unprecedented.

He called a meeting of all the enslaved families.

They gathered in the yard, weary and uncertain.

The last time they had been called together, Silas had announced the sale of their children.

They didn’t know what to expect now, but they prepared for the worst.

Silas stood on the porch, the same spot where he had made the announcement 6 days earlier.

But this time, everything about him was different.

His posture was less rigid.

His voice was quieter.

And when he spoke, there was something in his tone that none of them had ever heard before.

uncertainty, humility, perhaps even shame.

I’m giving you a choice, he said.

The families exchanged glances, confused.

Enslaved people didn’t get choices.

Anyone who wants to leave can leave, Silas continued.

His voice was steady, but there was an undercurrent of emotion that threatened to break through.

I won’t stop you.

I’ll give you papers saying you’re free.

You can go north, find the union lines, start over.

Anyone who wants to stay can stay.

I’ll pay wages.

Not much, but something.

Real money, not script.

And the children? He paused, his voice catching.

The children will go to school.

I’ll hire a teacher.

They’ll learn to read and write.

The silence that followed was profound.

No one moved.

No one spoke.

They simply stared at him trying to understand if this was real or another cruel trick.

I know you don’t trust me, Silas said.

And for the first time, his voice broke slightly.

I don’t blame you.

I’ve given you no reason to trust me, but I’m telling you the truth.

You’re free to choose.

And whatever you decide, I won’t punish you for it.

” He turned and went back inside, leaving them standing in the yard, stunned.

Over the next week, the families discussed what to do.

Some were suspicious, believing this was a trap.

Others were cautiously hopeful.

A few were simply too exhausted to care.

They had survived this long, and they would continue to survive whatever Silus’s motivations might be.

In the end, 11 families left.

They packed what little they had.

A few clothes, some cooking implements, blankets, and walked north toward the promise of Union protection.

It was winter.

The roads were dangerous and they had no guarantee of safety.

But they chose to take the risk rather than stay on a plantation where they had been treated as property for so long.

12 families stayed, not because they trusted Silas, but because they had nowhere else to go.

Winter was brutal for those without shelter, and the roads were full of Confederate patrols who would capture and reinsslave any black person without papers.

Staying was the practical choice, even if it meant remaining in a place filled with painful memories.

Silas kept his word.

In early January, he hired a teacher, a widow from Valdosta named Mrs.

Callaway.

She was in her 50s, educated, and had been struggling to make ends meet since her husband’s death.

Silus offered her room and board, plus a small salary, to teach the children three times a week.

Mrs.

Callaway was skeptical at first.

She had heard stories about Silas Harrove, about his coldness and his reputation as a harsh master.

But when she arrived at the plantation and saw the children, saw their eagerness to learn, their bright eyes and quick minds, she agreed to take the position.

She set up a small school room in one of the unused storage buildings.

She taught reading, writing, arithmetic, and history.

The children were hungry for knowledge, absorbing everything she taught them with an intensity that moved her to tears.

Thomas, the 14-year-old blacksmith’s apprentice, was her star pupil.

He could already read a little.

His mother had secretly taught him using a Bible, and he quickly advanced beyond the basics.

Within weeks, he was reading at a level that would have been impressive for any child his age, enslaved or free.

Silas also began paying wages.

They were small, just a few dollars a month per family.

But they were paid in gold, not Confederate script.

For people who had never been paid for their labor, who had never had money of their own, it was a profound change.

He stopped carrying a whip.

He stopped entering the quarters uninvited.

He stopped issuing punishments for minor infractions.

The plantation continued to operate, but the atmosphere had changed.

There was less fear, less tension.

People still worked hard, but they worked with a sense of purpose rather than terror.

But Silas himself was changing in ways that went beyond policy.

Those who observed him closely noticed that he seemed haunted.

He would stop in the middle of a task and stare into the distance as if seeing something no one else could see.

He would wake in the middle of the night and walk through the plantation, stopping at the edge of the cotton fields, staring into the darkness.

He began attending church in Valdasta, sitting in the back pew, never speaking to anyone.

He would arrive just as the service started and leave the moment it ended, avoiding conversation.

But he listened intently to every sermon, especially those about redemption, forgiveness, and the weight of sin.

Dutch Keller left in February of 1864.

He told anyone who would listen that Silas had lost his mind.

He’s not the same man, Dutch wrote in a letter to his brother.

Something broke in him that night.

He walks around like a ghost, talking to himself, staring at nothing.

He’s paying them wages for God’s sake, treating them like they’re free.

I can’t work for a man like that.

He’s going to lose everything, and I won’t be there to watch it happen.

Dutch was right about one thing.

Silas was losing everything.

Without the gold from the sale, he couldn’t pay his debts.

The creditors began sending increasingly threatening letters.

The bank in Savannah filed a lean against the property.

Suppliers refused to extend credit.

But Silas didn’t seem to care.

He continued to pay wages.

He continued to fund the school.

He continued to treat the people on his plantation as human beings rather than property.

In March of 1864, he did something even more unprecedented.

He began writing letters to government officials advocating for the rights of enslaved people.

He wrote to the governor of Georgia, to members of the Confederate Congress, to anyone who might listen.

His letters were passionate, detailed, and deeply personal.

In one letter discovered years later in the state archives, he wrote, “I have spent my life believing that slavery was a natural order, a necessary institution, a system ordained by God.

I was wrong.

I have seen the faces of children torn from their mothers.

I have heard the whales of parents who know they will never see their sons and daughters again.

I have felt for just a moment the terror and despair of those who are treated as property rather than people.

And I can no longer remain silent.

This system is evil.

It destroys not only those who are enslaved but also those who enslave.

It corrupts the soul and blinds us to the humanity of our fellow man.

I do not expect forgiveness for my role in perpetuating this evil.

But I can at least speak the truth, even if no one listens.

The letters were ignored.

Some were mocked.

A few resulted in threats.

But Silas continued to write them, driven by a compulsion he couldn’t explain.

The war dragged on through 1864 and into 1865.

Sherman’s army marched through Georgia in late 1864, burning plantations and freeing enslaved people in their wake.

The Harrove plantation was spared, likely because it was so isolated and appeared already abandoned.

By the time Union soldiers reached the area, there was little left to burn.

In April of 1865, Lee surrendered at Appamatics and the war officially ended.

News traveled slowly to southern Georgia, but by late April, word had reached Vald Dosta.

The Confederacy was dead.

Slavery was abolished.

Silas gathered the remaining families and told them they were legally free now.

He offered to let them stay and work for wages or leave with his blessing and whatever supplies he could spare.

Most stayed, not out of loyalty to Silas, but out of practicality.

The world outside was chaos.

The roads were full of displaced people, both black and white.

The economy had collapsed.

There were no jobs, no infrastructure, no safety net.

The plantation, for all its dark history, offered stability.

But the relationship had changed.

The families were no longer enslaved.

They were workers, employees, people with agency and choice.

And Silas treated them as such.

He began dividing the plantation land, offering plots to families who wanted to farm independently.

He provided seed, tools, and advice.

He helped them establish their own small farms, even though it meant reducing the size of his own operation.

In 1867, he sold most of the remaining plantation land to the families who had stayed, offering them terms so generous that a lawyer in Valdosta accused him of financial suicide.

The lawyer was probably right.

Silas sold the land for a fraction of its value, accepting payment in installments over 10 years with no interest.

“Why are you doing this?” the lawyer asked him.

“You’re giving away everything your family built.

” Silas looked at him with those haunted eyes and said, “Because it was never mine to begin with.

” He kept only the big house and a few acres around it.

The rest, nearly 300 acres, was divided among 12 families.

12 families for 12 children.

It wasn’t a coincidence.

Silas lived alone in the big house, refusing to remarry or reconnect with his own children in Savannah.

He wrote to them occasionally, but they rarely responded.

They had built new lives, and Silas was a reminder of a past they wanted to forget.

He spent his days reading, writing, and walking the fields.

He continued to attend church, continued to write letters advocating for the rights of formerly enslaved people, continued to live with the weight of what he had done.

And every Christmas Eve he would stand in the yard at midnight in the exact spot where he had seen the 12 children, and he would stay there until dawn.

No one knew what he was doing.

Some thought he was praying, others thought he was keeping vigil.

A few believed he was waiting for something or someone to return.

“Mrs.

Callaway, who continued to teach at the school even after the war ended, once asked him about it.

” “Why do you stand out there every Christmas Eve?” she asked.

Silas was silent for a long time.

“Then he said, “Because I need to remember.

” “Remember what? What I almost did, what I was, and what they showed me.

” The children.

Silas nodded.

They didn’t curse me.

They didn’t harm me.

They simply made me see, made me feel what they felt.

And it changed me in a way I can’t explain.

Every Christmas Eve, I stand in that spot and remember because if I forget, even for a moment, I might become that man again.

In 1872, Silus Hargrove fell ill.

It started as a persistent cough in October, then progressed to fever and weakness by November.

By December, he was bedridden, his body frail, but his mind still sharp.

Mrs.

Callaway visited him regularly, bringing him food and medicine, sitting with him when he was too weak to be alone.

She had grown to respect him over the years, though she never fully understood him.

He was a man haunted by his past, driven by guilt and a desperate need for redemption.

“Do you have any regrets?” she asked him one afternoon in mid December, sitting beside his bed.

Silas was silent for a long time, staring at the ceiling.

Then he said, “Only one.

” That it took me so long to see them as human.

The children, “All of them,” Silas said.

“Every single person I owned.

I told myself it was business.

I told myself it was the way things were.

I told myself I was a good master, that I treated them well compared to others.

But that night, he trailed off his eyes distant.

That night they showed me what I really was and I couldn’t unsee it.

What did they show you, Mrs.

? Callaway asked gently.

Silas looked at her, his eyes filled with something between sorrow and terror.

That I was the monster, not them, me.

I was the one who stole lives, who destroyed families, who treated human beings as property.

And the worst part is I did it all while believing I was righteous, that I was doing what was necessary, what was natural.

They showed me the truth and it destroyed me.

But it also saved me.

Saved you from what? From becoming something I could never come back from.

Silas said, “If I had sold those children, if I had gone through with it, I would have crossed a line that couldn’t be uncrossed.

I would have become something less than human myself.

They saved me from that.

And I’ve spent every day since trying to be worthy of that gift.

On December 20th, Silas asked Mrs.

Callaway to bring him his journals.

He had been keeping detailed personal journals since that Christmas night in 1863, filling page after page with his thoughts, his memories, his attempts to understand what had happened.

He spent 3 days reviewing them, making notes in the margins, adding final entries.

On December 23rd, he sealed them in a metal box and gave them to Mrs.

Callaway.

“Keep these safe,” he said.

“Someday someone might want to know what really happened, what I did, and what they did to save me from myself.

” “Who are they?” Mrs.

Callaway asked.

“The 12,” Silas said.

“The children.

They’re grown now, scattered across the country.

But I still see them sometimes in my dreams.

Still standing in that line, watching me, waiting for me to understand.

Do you understand now? Silus smiled, a sad, weary smile.

I’m beginning to.

On December 24th, 1872, exactly 9 years after the night he had tried to sell the 12 children, Silas Hargrove died.

It was just after midnight Christmas morning.

Mrs.

Callaway was with him, holding his hand when he took his last breath.

His final words were barely a whisper.

Forgive.

The families who had stayed on the plantation buried him in the small cemetery on the hill, not far from where Catherine had been buried 13 years earlier.

They marked his grave with a simple stone that bore only his name and dates.

No epitap, no flowery language, just the facts.

But they also did something unexpected.

They planted 12 small trees around his grave, one for each of the children he had almost sold.

Oak trees, strong and enduring, that would grow tall and provide shade for generations to come.

It was a gesture that confused outsiders.

Why would formerly enslaved people honor the man who had once owned them, who had once tried to sell their children, but those who had lived through that Christmas night understood? Silus Harrove had been a monster, yes, but he had also been a man who had changed, who had spent the last 9 years of his life trying to atone for his sins.

He hadn’t succeeded.

Some sins are too great for atonement, but he had tried.

And in a world where most slaveholders never acknowledged their crimes, never changed their ways, never showed even a hint of remorse, that meant something.

In 1891, a fire swept through the old plantation house.

It had been abandoned for years, slowly decaying, the windows broken, the roof collapsing, the walls covered in vines.

No one was surprised when it finally burned.

Lightning strike, most people assumed, or perhaps a vagrant’s campfire that got out of control.

But when county officials came to assess the damage and determine if the property was safe, they found something in the ruins.

Beneath the charred floorboards of the study, they discovered a metal box.

It was scorched but intact, sealed tight against the flames.

Inside were Silus’s journals, not the business ledgers, but personal journals he had kept from 1863 until his death.

The county clerk, a man named William Brennan, no relation to Silus’s late wife, took the journals back to his office and began to read them.

What he found disturbed him so deeply that he sealed the journals and refused to discuss them publicly for years.

The entries from December 1863 were the most disturbing.

Silas had written about the night of the 25th in excruciating detail.

the children in the yard, the fire in the fields, the hands in the darkness, the overwhelming emotions that had flooded through him.

But he had also written something else, something that Brennan found so unsettling that he questioned his own sanity for believing it.

In the final entry from that night, written in the early hours of December 26th, Silas had described what he believed had happened.

They didn’t speak, but I heard them, not with my ears, but with something deeper.

They asked me a question over and over in voices that weren’t voices.

Do you see us not as property, not as numbers in a ledger, but as children, as human beings, as souls with the same capacity for pain, fear, and love as my own children.

And I realized with a horror I cannot describe that I had never truly seen them, not once.

I had looked at them every day of my life and never truly seen them.

And that night they made me see.

They made me feel what they felt.

The terror of being torn from their mothers.

The confusion of being sold like animals.

The absolute helplessness of being a child with no power, no voice, no future.

They didn’t curse me.

They didn’t harm me.

They simply made me see.

And it broke something in me that can never be repaired.

Brennan read this passage multiple times trying to understand it.

Was Silas describing a hallucination, a psychological break, or something else? He continued reading.

In subsequent entries, Silas had written about his transformation, his attempts to atone his ongoing struggle with guilt, but he kept returning to that night, trying to understand what had happened.

In an entry from March 1864, Silas wrote, “I have spent months trying to rationalize what happened that night.

I have told myself it was exhaustion, stress, guilt manifesting as hallucination.