The master sold the enslaved woman’s children to pay $1,000 in debts — but she did the impossible

This is a painful and intense story about loss, desperation, and a choice that no one believed she could make.

In October of 1855 in Adams County, Mississippi, a white plantation owner named Thomas Whitmore made a decision that would eventually destroy everything he had ever built.

He sold three children to pay off a gambling debt of $1,000.

But these were not just any children.

These were his own flesh and blood.

Children he had fathered through the systematic rape of an enslaved woman named Celeste.

He sold his own sons and daughter as if they were cattle.

Never imagining that the woman he had brutalized for over a decade would be the architect of his complete and utter ruin.

This is a story about what happens when a man underestimates the woman he believes he owns.

It is a story about patience, about cunning, and about a mother’s love so powerful that it burned through every obstacle placed before it.

It is also a story about justice, though not the kind that comes from courts or laws.

This is the story of Celeste and how she brought a powerful white man to his knees without ever raising a weapon.

To understand what happened in Adams County, you first need to understand what Mississippi looked like in the 1850s.

By this time, cotton was king in the American South, and Mississippi sat at the very heart of that kingdom.

The state had some of the richest soil in the entire region, particularly along the Mississippi River, where the land was dark and fertile from centuries of flooding.

Plantation owners had carved out massive estates from this land.

Some spanning thousands of acres.

All of it worked by enslaved people who had no rights, no freedom, and no legal protection from any cruelty their masters chose to inflict.

Adams County was one of the oldest and wealthiest counties in the state.

The town of Nachez, which served as the county seat, was home to more millionaires per capita than almost anywhere else in the United States.

These were men who had built their fortunes on the backs of enslaved laborers.

Men who lived in grand columned mansions, while the people who made their wealth possible lived in rough wooden cabins with dirt floors.

The social hierarchy was rigid and absolute.

White planters sat at the top, followed by white overseers and merchants.

Then poor whites who owned no slaves, and at the very bottom, treated as property rather than people, were the enslaved.

Thomas Whitmore was not one of the great planters of Adams County, but he desperately wanted to be.

His family had arrived in Mississippi in the 1820s, purchasing a modest property of about 400 acres that they called Witmore Hall.

It was not a grand estate by local standards, but it was respectable.

Thomas inherited the property in 1841 when his father died of yellow fever, and from the very beginning he was consumed by the desire to expand, to grow, to become one of the wealthy elite, whose approval he so desperately craved.

The problem was that Thomas Whitmore had expensive tastes and very little business sense.

He gambled heavily on horse races and card games.

He invested in ventures that collapsed.

He bought things he could not afford to impress people who looked down on him anyway.

By the early 1850s, Whitmore Hall was mortgaged to the limit, and Thomas was drowning in debt that he hid from everyone, including his wife, Margaret.

Margaret Witmore came from a family with more social standing than money, which made her the perfect match for Thomas in one sense and a disaster in another.

She brought respectability but no fortune.

She was a cold woman, rigid in her beliefs and obsessed with maintaining appearances.

The couple had two children together, both sons, who were sent away to boarding school in Virginia at young ages.

Margaret ran the household with an iron fist and spent most of her time engaged in social activities with other plantation wives, pretending that everything at Whitmore Hall was perfectly fine.

At the time our story begins, Witmore Hall was home to approximately 47 enslaved people.

They worked the cotton fields, tended the livestock, maintained the house, and performed every task necessary to keep the plantation running.

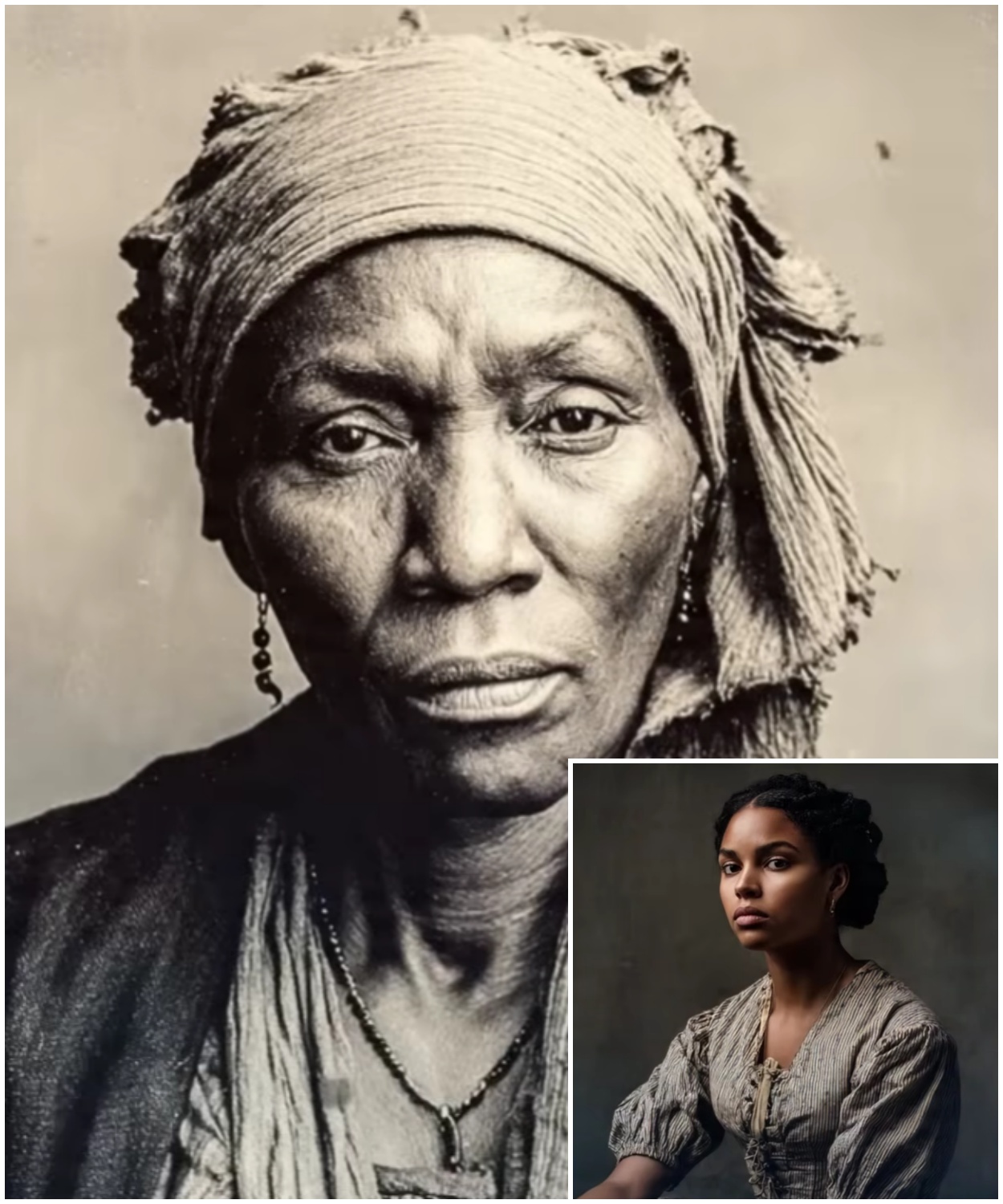

Among them was a woman named Celeste.

Celeste had been born on a plantation in Virginia around 1822.

She never knew her father.

Her mother, a woman named Ruth, worked as a house slave and raised Celeste to be quiet, obedient, and invisible.

These were survival skills in a world where attracting attention could get you beaten or sold.

When Celeste was 12 years old, her mother was sold to a trader heading south to pay off her master’s debts, and Celeste never saw her again.

She was sold separately to a family moving to Mississippi, and after changing hands twice more, she ended up at Whitmore Hall in 1837 when she was about 15 years old.

Thomas Witmore noticed her immediately.

Celeste was what slave traders of the era would have called a fancy girl, a term that should make your skin crawl, but which was used openly and commonly in the antibbellum south.

It referred to enslaved women and girls who were considered attractive by white standards and who were often purchased specifically for sexual exploitation.

Celeste had light brown skin which indicated mixed ancestry somewhere in her family line and features that Thomas Witmore found appealing.

Within months of her arrival at the plantation, he began visiting her cabin at night.

There was no courtship.

There was no seduction.

There was only power and violence.

Thomas Witmore raped Celeste for the first time when she was 15 years old and he continued to assault her regularly for the next 18 years.

This was not unusual in the antibbellum south.

Historians estimate that by the time of the Civil War, the majority of enslaved people in America had some European ancestry, a statistic that speaks to the epidemic of sexual violence that white men perpetrated against black women for generations.

masters had total legal control over enslaved women’s bodies.

Legal control over enslaved women’s bodies.

There was no law that recognized the rape of an enslaved woman as a crime.

In the eyes of the law, Celeste was property, and Thomas Whitmore could do whatever he wanted with his property.

Celeste’s first child, a boy she named Samuel, was born in 1843.

The baby’s skin was noticeably lighter than Celeste’s own, and his features bore an unmistakable resemblance to Thomas Whitmore.

Everyone on the plantation knew whose child Samuel was.

The other enslaved people knew.

The white overseers knew.

Margaret Witmore knew, though she never spoke of it directly.

This was another ugly reality of plantation life that everyone understood and no one discussed openly.

mixed race children fathered by white masters were everywhere.

Living proof of systematic sexual exploitation that polite society pretended did not exist.

3 years later in 1846, Celeste gave birth to a daughter she named Eliza.

And in 1850, she had another son, Isaiah.

All three children were Thomas Witmore’s.

All three were born into slavery, and all three were raised by Celeste alone in a small cabin behind the main house, while their father lived in comfort just a few hundred yards away and pretended they did not exist.

Celeste did everything she could to protect her children and give them what small joys were possible within the confines of their brutal existence.

She sang to them every night.

She told them stories about a world where people could go wherever they wanted and do whatever they chose.

She taught them to be careful, to stay out of sight, to never give any white person a reason to notice them.

She also watched them constantly for any sign that Thomas Whitmore might turn his attention to Eliza the way he had turned it to her.

This was a fear that haunted many enslaved mothers.

The knowledge that their daughters could be victimized just as they had been, and there would be nothing they could do to stop it.

By 1855, Samuel was 12 years old and already working in the fields.

He was tall for his age and strong, a good worker who kept his head down and did what he was told.

Eliza was nine, a quiet girl who helped with domestic work in the main house and who had learned, as her mother had learned, to be invisible.

Isaiah was five, still young enough to play with the other children on the plantation.

Still innocent enough to smile and laugh despite the world he had been born into.

Celeste loved them with a ferocity that frightened her sometimes.

They were the only good things in her life, the only things that were truly hers.

She would have died for them without hesitation.

She would have killed for them if she had to, but she never imagined that she would have to watch them be taken from her, sold like animals to strangers while their own father counted the money.

The trouble began in the summer of 1855.

Thomas Whitmore had gotten himself into a gambling debt that he could not pay.

He owed $1,000 to a man named Crawford, a cotton broker from Nachez, who was not known for his patience.

Crawford had given Whitmore multiple extensions, but his patience had run out.

He wanted his money, and he made it clear that if he did not get it, he would start talking publicly about Witmore’s debts.

In the social world of Adams County, where reputation was everything, this threat was almost as frightening as physical violence.

Witmore was desperate.

He had already borrowed everything he could borrow.

He had sold off parcels of land until there was nothing left to sell without losing the plantation itself.

His crops that year had been mediocre, not enough to cover his operating expenses, let alone pay off his debts.

He needed $1,000 and he needed it quickly.

The solution, when it came to him, was brutally simple.

He would sell some of his slaves.

Slave sales were common in the Antibbellum South, as common and unremarkable as selling livestock.

Every southern city had slave markets where human beings were bought and sold openly.

Nachez had one of the largest markets in the region located on a place called Forks of the Road where hundreds of enslaved people were sold every month.

The prices varied depending on age, health, skills, and other factors.

A healthy adult male fieldand could fetch between $800 and $1,500.

Women typically sold for somewhat less unless they were skilled domestic workers or young and attractive, in which case they might command premium prices for obvious and horrifying reasons.

Children were generally worth less than adults, but a healthy child who could grow into a productive worker was still a valuable commodity.

Thomas Witmore knew exactly which slaves he would sell.

Samuel was strong and healthy, already capable of doing real work in the fields.

He would fetch a good price.

Eliza was young but pretty, domestic trained, the kind of girl who would appeal to certain buyers.

Isaiah was young, but young children often sold in lots or to buyers who were looking for long-term investments.

Together, the three children might bring in more than enough to cover Whitmore’s debt to Crawford.

The fact that these children were his own flesh and blood apparently did not give him any pause.

Perhaps he had never really thought of them as his children.

Perhaps he had spent so many years denying their existence that he had convinced himself they meant nothing to him.

Perhaps he was simply so desperate, so terrified of social ruin that he was willing to do anything to save himself.

Whatever his reasoning, Thomas Witmore made his decision, and on a cool October morning in 1855, he set that decision in motion.

Celeste knew nothing of what was coming.

She woke that morning before dawn, as she always did, and began her work in the kitchen.

She had been assigned to domestic work years earlier, which meant she spent her days cooking, cleaning, and serving in the main house, while her children worked elsewhere on the plantation.

It was hard work, but it kept her close to the house where she could sometimes catch glimpses of her children and know they were all right.

The first sign that something was wrong came around midm morning.

Celeste was in the kitchen when she heard horses approaching, more horses than usual.

She looked out the window and saw three men she did not recognize riding up the drive with Thomas Whitmore.

They were well-dressed, clearly men of some means, and they had the look of people who had come to do business.

Something cold settled in Celeste’s stomach.

She had seen slave traders before.

She had seen the way they looked at human beings, the way they assessed and calculated and reduced people to numbers and dollar signs.

These men had that look.

She tried to tell herself she was wrong.

She tried to convince herself that Witmore was selling field hands or maybe some of the older workers who could not produce as much anymore.

But the cold feeling would not go away, and when she saw one of the men pointing toward the area where the children usually played, she felt her heart stop.

Celeste moved without thinking.

She ran out of the kitchen and toward the slave quarters, ignoring the shouts behind her, ignoring everything except the desperate need to reach her children.

She found Samuel first, grabbed him by the arm, and demanded to know where Eliza and Isaiah were.

Before he could answer, she heard Eliza scream.

The next few minutes were a nightmare that Celeste would relive every night for years to come.

White men, strangers were grabbing her children and dragging them toward the waiting horses.

Samuel fought back and a man hit him across the face so hard that blood sprayed from his nose.

Eliza was crying and calling for her mother, struggling against hands that gripped her thin arms like iron bands.

Isaiah, just 5 years old, stood frozen in terror, tears streaming down his face, too frightened to even make a sound.

Celeste threw herself at the men.

She clawed and scratched and bit, fighting with every ounce of strength she possessed.

It made no difference.

Someone hit her from behind, and she went down hard, her face striking the dirt.

By the time she managed to push herself up, her children were already being loaded into a wagon.

Samuel was still fighting, and they had tied his hands.

Eliza had gone limp, her eyes empty with shock.

Isaiah was crying for his mama, reaching his small arms toward her, calling her name over and over.

And standing beside the wagon, watching all of this with a blank expression on his face, was Thomas Witmore.

Celeste looked at him.

This man who had violated her for nearly two decades, this man who had fathered her children and was now selling them like livestock.

And she felt something change inside her.

The fear and desperation that had been driving her moments before transformed into something else, something cold, something patient, something deadly.

She did not scream.

She did not beg.

She simply looked at Thomas Witmore.

And in that moment, she made a silent vow.

She did not know how, and she did not know when, but she would destroy him.

She would take everything he had.

She would make him suffer in ways he could not imagine.

And then, when he had lost everything, she would find her children and bring them home.

The wagon pulled away, carrying her children down the dusty road toward Natchez, where they would be separated and sold to different buyers.

Samuel was sold to a cotton planter from Alabama named Jeremiah Stone.

Eliza was purchased by a wealthy family in New Orleans for domestic service.

Isaiah, too young to be of much immediate use, was sold cheaply to a sugar plantation in Louisiana, where young children were often worked in the fields almost as soon as they could walk.

Within the span of a single morning, Thomas Witmore had scattered his own children across three states.

He paid off his debt to Crawford and went back to his life as if nothing had happened.

He ate dinner that night in his fine dining room, served by enslaved people who moved silently around him.

He slept in his comfortable bed next to his wife, Margaret, who asked no questions about where the money had come from.

He woke the next morning and went about his business, never giving a second thought to the children he had sold or the woman whose life he had just destroyed.

But Celeste was already planning.

In the days following the sale, Celeste moved through her duties like a ghost.

She cooked and cleaned and served just as she always had.

She responded when spoken to and obeyed every command.

To anyone watching, she appeared to be a woman who had accepted her loss, who had resigned herself to the reality of her situation.

This was exactly what she wanted them to see.

Inside, her mind was working constantly, turning over plans and possibilities, looking for weaknesses she could exploit.

She had no power, no money, no legal rights.

She was property, and everything she did was under the constant surveillance of white people who could punish her for any perceived disobedience.

Any plan she made would have to be executed with perfect patience and absolute secrecy.

One mistake, one suspicious move, and she would be sold away herself, or worse, beaten until she could no longer think clearly enough to plan anything at all.

The first thing Celeste needed was information.

She needed to understand Thomas Whitmore’s weaknesses, his secrets, the things he kept hidden from the world.

She needed to find something she could use against him.

Some leverage that would allow a powerless enslaved woman to bring down a white plantation owner in a society that was designed to make such a thing impossible.

Working in the main house gave her opportunities that field slaves did not have.

She was in and out of rooms all day cleaning and cooking and serving.

She overheard conversations that were not meant for her ears.

She saw documents left out on desks, letters that arrived in the mail, visitors who came and went.

Most enslaved house workers learned to be selectively deaf and blind to protect themselves by pretending not to notice anything.

Celeste did the opposite.

She began paying attention to everything.

At first, she did not know what she was looking for.

She gathered information almost randomly, memorizing names and numbers and snippets of conversation without knowing what any of it meant.

Thomas Witmore talked about money troubles with visitors.

Margaret Witmore wrote letters to her sister complaining about her husband’s gambling.

The overseer reported on crop yields and slave productivity.

Business associates came to discuss cotton prices and shipping arrangements.

Celeste absorbed all of it, filing everything away in her memory, waiting for something useful to emerge.

The problem was that Celeste could not read.

Like the vast majority of enslaved people in the South, she had never been taught.

In most southern states, it was actually illegal to teach enslaved people to read and write.

Slaveholders understood that literacy was power, that a person who could read, could access information, forge passes, communicate secretly with others.

They kept their human property illiterate deliberately as a form of control.

But Celeste knew that if she was going to find what she needed, she would have to learn, and she knew exactly who could teach her.

His name was Solomon.

He was an old man, nearly 70, who had worked at Witmore Hall since before Thomas was born.

In his youth, he had been a house slave on a plantation in Virginia, where the master, unusually, had allowed some slaves to learn basic reading and arithmetic.

Solomon had learned to read as a child and had kept that knowledge hidden for over 50 years.

He was careful, never reading openly, never revealing his skill to anyone he did not trust.

Absolutely.

But Celeste had known him her whole time at Witmore Hall, and she knew his secret.

She had seen him once late at night reading a scrap of newspaper he had found.

He had looked up and seen her watching, and for a long moment they had simply stared at each other.

Then she had turned and walked away without saying a word, and neither of them had ever spoken of it.

Now she went to Solomon and asked him to teach her.

It was an enormous risk for both of them.

If they were caught, the consequences would be severe.

Solomon could be sold, beaten, possibly killed.

Celeste could face the same punishments.

But Solomon looked at her and he saw something in her eyes that made him agree.

Maybe he recognized the rage and determination that burned behind her calm exterior.

Maybe he simply understood that some risks were worth taking.

Whatever his reasons, he said yes.

They began meeting in secret late at night in a corner of the barn where they were unlikely to be discovered.

Solomon taught Celeste the alphabet, then simple words, then gradually more complex texts.

Celeste was a fast learner driven by a motivation that made her absorb information like dry soil absorbs rain.

Within months, she could read basic documents.

Within a year, she could read almost anything, though slowly and with effort.

Now she could access information that had been closed to her before.

She could read the letters that Margaret Witmore received and left lying around.

She could read the business documents in Thomas Whitmore’s study when she was cleaning.

She could read the receipts and records that tracked every financial transaction on the plantation.

And gradually, a picture began to form.

Thomas Whitmore was not just struggling financially.

He was on the verge of complete collapse.

He owed money to almost everyone from banks to merchants to fellow planters.

He had borrowed against the plantation itself, meaning that if he defaulted on his loans, he could lose everything.

His cotton yields had been declining for years, in part because he refused to invest in proper land management, and in part because he worked his enslaved laborers so hard that their productivity was dropping from exhaustion and illness.

His wife Margaret had a small inheritance that was kept separate from his finances, but even that was not enough to save him.

Thomas Witmore was a drowning man and he was pulling everyone around him under.

This was useful information, but it was not enough.

Financial troubles might embarrass Whitmore, but they would not destroy him.

Planters went into debt all the time.

Many of the great fortunes of the South had been built on borrowed money.

Whitmore’s creditors might pressure him, might even force him to sell assets, but they would not bring him the kind of ruin that Celeste wanted.

She needed something more.

She needed something that would turn his own community against him, something that would make him an outcast, something unforgivable.

She found it in the spring of 1857, almost 2 years after her children had been sold.

Celeste was cleaning Thomas Whitmore’s study when she found a letter that had been carelessly left in an unlocked drawer.

It was addressed to a man named Harrison, who Celeste knew to be one of Whitmore’s oldest friends from their school days together.

The letter was several years old, dated from around the time of Isaiah’s birth, and it was written in Witmore’s own hand.

What she read in that letter made her hands shake.

The letter was casual, almost joking, the way men sometimes write to old friends when they think no one else will ever read their words.

Whitmore was complaining about his wife, about how cold and unactionate she was, and boasting about his relationship with Celeste.

But it was not the relationship that ordinary people might imagine.

Whitmore wrote about his children, Samuel and Eliza, and the baby who had just been born, and he wrote about them in a way that made his paternity absolutely clear.

He made crude jokes about his shadow family in the slave quarters.

He expressed satisfaction that his real legacy might be carried on by children who would never bear his name.

He even mentioned physical characteristics that proved the children were his.

Details that no one could know unless they had observed the children closely.

It was a confession written in his own hand, signed with his own name, and Celeste held it in her hands.

She stood there in the study, barely breathing, reading the letter over and over again.

Her heart was pounding so hard she could feel it in her throat.

She knew she had found what she was looking for.

This letter, if it reached the right people, could destroy Thomas Whitmore more completely than any financial scandal.

Here was the thing that white southern society refused to acknowledge openly, but could not ignore when confronted with proof.

Masters fathered children with enslaved women constantly, but they did not admit it.

They did not write about it.

They certainly did not joke about it in letters that could fall into the wrong hands.

The whole system depended on a kind of collective denial, a willingness to pretend that the light-skinned children in the slave quarters had simply appeared out of nowhere.

When a man was publicly exposed as the father of enslaved children, when the evidence was undeniable, the social consequences could be devastating.

Other planters would distance themselves from him.

Business partners would cut ties.

The polite fiction that held the whole rotten system together would be exposed as a lie, and everyone who had participated in that fiction would resent the man who had forced them to confront it.

But the financial implications were even more significant.

Thomas Whitmore had not just fathered children with an enslaved woman.

He had sold those children.

and the people who had bought them believed they were purchasing what the slave trade called full-blooded negroes, not the mixed race children of a white planter.

In the twisted logic of the antibbellum slave market, this was fraud.

The buyers had paid for one type of merchandise and received another.

They could demand refunds.

They could sue.

They could accuse Whitmore of deliberately misrepresenting the goods he had sold.

This was not about morality.

Morality had nothing to do with how the South operated.

This was about money and reputation, the only things that truly mattered to men like Thomas Whitmore.

And Celeste had just found the weapon that would take both of those things away from him.

But she could not act yet.

She needed to plan carefully.

She needed to gather more evidence and she needed to figure out how to expose Witmore without getting herself killed in the process.

So she carefully placed the letter back in the drawer exactly as she had found it and she went back to her work.

She gave no sign that anything had changed.

She cooked dinner that night as she always did.

She cleaned the dishes.

She went to her cabin and lay in the darkness, staring at the ceiling, and she began to plan.

Over the next several months, Celeste gathered more evidence.

She found Margaret Whitmore’s diary, which contained pages and pages of anguished entries about her suspicions regarding her husband and that woman.

Margaret had never confronted Thomas directly, had never spoken about it openly, but she had written everything down in her private journal.

She described the children in the slave quarters who looked so much like her husband.

She wrote about finding Thomas leaving Celeste’s cabin late at night.

She documented her humiliation and her rage, all in her own handwriting, creating a record that corroborated the letter to Harrison.

Celeste also managed to save small items that could serve as physical evidence.

Locks of hair from Samuel and Eliza that she had kept from when they were babies.

a small toy that Thomas had carved for Samuel when the boy was very young before Witmore had completely hardened himself to his children’s existence.

These things alone proved nothing, but combined with the written evidence, they created a picture that would be difficult to deny.

The final piece of her plan involved the buyers who had purchased her children.

Celeste needed to find out who they were and where they had taken Samuel, Eliza, and Isaiah.

This information was not easy to obtain.

Slave sales were often poorly documented, and sellers had no obligation to tell enslaved parents anything about where their children had been taken.

But Celeste listened carefully whenever business was discussed in the house, and she eventually learned enough to piece together the basic facts.

A planter from Alabama named Stone had bought Samuel.

A New Orleans family named Bowmont had purchased Eliza, and Isaiah had been sold to a sugar operation in Louisiana, though she could not discover the exact location.

Now she had the evidence, and she knew who had her children.

The question was how to use what she had learned.

Celeste could not simply mail the letter and diary pages to the buyers herself.

She could not read and write in any way that would allow her to communicate directly with white people.

Even if she could, no one would believe accusations coming from an enslaved woman.

They would assume she was lying or they would simply not care.

She needed someone else to deliver the information, someone whose word would be taken seriously.

She found that person in the fall of 1857.

His name was James Crawford, and he was the same cotton broker to whom Thomas Witmore had owed $1,000 two years earlier.

Crawford was not a moral man by any stretch of the imagination.

He bought and sold cotton that was produced by slave labor, and he had no qualms about the institution that made his business possible.

But he was a businessman, and he had a businessman’s contempt for people who cheated and lied and failed to pay their debts.

He still resented Witmore for the way he had been strung along for months before finally getting his money, and he was always looking for information that could give him an advantage over his competitors and debtors.

Celeste took an enormous risk.

She approached Crawford when he visited the plantation on business, waiting until she found him alone for a moment, and she told him that she had information about Thomas Witmore that would be worth a great deal to the right people.

Crawford was suspicious at first, but Celeste was careful.

She did not reveal everything at once.

She gave him just enough to peique his interest, hinting at scandal and fraud without spelling out the details.

She told him that Whitmore had sold children under false pretenses and that the buyers would be very interested to learn the truth about what they had purchased.

Crawford was intrigued.

He did not trust Celeste, but he recognized that she might be telling the truth.

He agreed to investigate and he told her that if her information proved accurate, he would make sure it reached the people who needed to know.

Over the next few weeks, Crawford did his own research.

He contacted the buyers who had purchased Samuel, Eliza, and Isaiah, asking casual questions about their purchases and whether they were satisfied with what they had received.

He examined records of the sales and noted the descriptions of the children that had been provided.

And then, when he had confirmed enough to believe Celeste’s story, he came back to her and asked for the evidence.

Celeste gave him copies of the letter and the diary pages which she had painstakingly reproduced by hand during late nights in the barn.

Practicing the writing skills that Solomon had taught her, she gave him the locks of hair and the small carved toy, and she told him everything she knew about Thomas Witmore’s relationship with her and with the children he had fathered and sold.

Crawford took the information and disappeared from Whitmore Hall.

For weeks, Celeste heard nothing.

She continued her work, giving no sign that anything was different, waiting and hoping that her plan would work.

She did not know if Crawford would follow through.

She did not know if the evidence would be enough.

She did not even know if she would survive long enough to see the results of what she had set in motion.

Then in early 1858, everything began to fall apart for Thomas Witmore.

The first sign that something had changed came in the form of a letter.

It arrived at Whitmore Hall on a cold January morning in 1858, addressed to Thomas Whitmore and marked urgent.

Celeste was serving breakfast when Witmore opened it, and she watched his face carefully while pretending to arrange dishes on the sideboard.

She saw the color drain from his cheeks.

She saw his hands begin to tremble.

She saw him read the letter twice, then a third time, as if he could not believe what was written there.

The letter was from Jeremiah Stone, the Alabama planter, who had purchased Samuel nearly 3 years earlier.

Stone was not a man who wasted words.

He wrote that he had recently received disturbing information about the boy he had bought from Whitmore.

He had been told that Samuel was not, as Witmore had represented, the child of two enslaved parents, but was in fact the illegitimate son of Whitmore himself.

Stone demanded an explanation.

He also demanded a full refund of the $400 he had paid, plus compensation for the expenses he had incurred in housing and feeding what he called damaged goods.

Thomas Witmore put down the letter and stared at nothing.

His wife Margaret asked him what was wrong and he told her it was nothing, just a business matter.

But Celeste could see the fear in his eyes.

She could see him beginning to understand that something terrible was happening, something he could not control.

Over the next few weeks, more letters arrived.

The Bowmont family in New Orleans, who had purchased Eliza, wrote with similar accusations and similar demands.

They were even angrier than Stone had been.

They had bought Eliza to serve in their household to attend to their daughters and help with domestic work.

Now they had learned that she was the halfsister of their own children’s playmates, the daughter of a white man who had sold his own flesh and blood.

The social implications horrified them.

What if someone found out? What if their friends learned that they had an enslaved girl in their house who shared blood with the white planter class? They wanted their money back immediately and they wanted Whitmore to take the girl back before the scandal could spread.

The sugar plantation in Louisiana that had purchased Isaiah did not bother with letters.

They sent a representative directly to Adams County, a hard-faced man who arrived at Whitmore Hall and demanded to speak with Thomas privately.

Celeste did not hear what was said in that meeting, but she saw Witmore afterward.

He looked like a man who had just been told he was dying.

The news spread through Adams County with the speed of a wildfire.

James Crawford, true to his nature, had not kept the information to himself.

He had shared it with business associates who shared it with their friends, who shared it with their wives, who spread it through every parlor and drawing room in Nachez.

Within weeks, everyone knew Thomas Whitmore had fathered children with an enslaved woman.

Thomas Whitmore had sold those children to unsuspecting buyers.

Thomas Whitmore had committed fraud, had lied, had violated the unwritten codes that governed how such things were supposed to be handled.

The reaction was swift and merciless.

This was not about morality.

Nobody in Adams County cared that Whitmore had raped an enslaved woman for 18 years.

That was common enough to be unremarkable.

Nobody even cared particularly that he had fathered children with her.

That too was common, though it was supposed to remain unacknowledged.

What they cared about was the fraud.

What they cared about was the public exposure.

What they cared about was the fact that Witmore had been caught, that his dirty secrets had been dragged into the light, and that his carelessness now threatened to expose the whole rotten system that they all participated in.

The other planters began to distance themselves from Whitmore almost immediately.

Men who had dined at his table and hunted on his land suddenly found reasons to be unavailable when he called.

Invitations to social events stopped arriving.

When Witmore appeared at church on Sunday, people moved away from him as if he carried a disease.

His wife Margaret sat rigid and pale in their pew, enduring the stares and whispers, her face a mask of humiliation.

The financial consequences followed close behind the social ones.

Whitmore’s creditors, who had been patient with him for years, suddenly demanded immediate payment of all outstanding debts.

Banks that had extended him credit called in their loans.

Business partners who had been willing to overlook his gambling and his financial mismanagement now wanted nothing to do with him.

Within three months, Thomas Whitmore went from being a struggling but respectable planter to being a pariah who could not borrow money from anyone.

The buyers of his children made good on their threats.

Jeremiah Stone filed a lawsuit in Alabama demanding not only a refund, but additional damages for fraud and misrepresentation.

The Bumont family did the same in Louisiana.

The sugar plantation joined the legal action and suddenly Thomas Whitmore was facing litigation in three different states with potential judgments that would far exceed anything he could pay.

But the worst blow came from inside his own house.

Margaret Witmore had spent years pretending not to know about her husband’s relationship with Celeste.

She had buried her suspicions, swallowed her humiliation, and maintained the facade of a respectable marriage because that was what women of her class and time were expected to do.

But now her private shame had become public knowledge.

Everyone knew, her friends knew, her family knew.

Her children away at school in Virginia would eventually hear the gossip.

Everything she had worked so hard to hide had been exposed, and she was forced to confront a truth she had spent years denying.

Margaret did not handle it well.

In the spring of 1858, she began showing signs of what people at the time would have called nervous collapse.

She stopped eating.

She stopped sleeping.

She would sit for hours staring at nothing, or she would fly into sudden rages, screaming at servants and throwing things.

She became obsessed with the idea that everyone was laughing at her, that she had become a joke, that her entire life had been a lie.

Her sister came from Virginia to care for her, but Margaret only grew worse.

By summer, she had stopped speaking coherently.

She would mutter to herself about children and blood and lies, and sometimes she would laugh for no reason at all.

In August of 1858, Margaret Whitmore’s family had her committed to the Mississippi State Lunatic Asylum in Jackson.

She would spend the rest of her life there, never recovering her sanity, never returning home.

The woman who had spent so many years maintaining appearances had finally been destroyed by the truth she had refused to face.

Thomas Witmore was now alone.

His wife was gone.

His legitimate children, informed of the scandal, refused to communicate with him.

His friends had abandoned him.

His creditors were circling like vultures, and the lawsuits from Alabama, Louisiana, and the sugar country were grinding forward, promising to take whatever he had left.

Celeste watched all of this from the shadows.

She continued her work in the house, cooking and cleaning and serving, giving no sign that she had any connection to the catastrophe that was engulfing her master.

If anyone suspected that she was responsible, they did not say so.

The idea that an enslaved woman could have orchestrated such a complex scheme of destruction would have seemed absurd to most white people of the time.

They could not imagine that someone they considered property could be capable of such intelligence, such patience, such ruthless determination.

But Celeste was not finished yet.

In the fall of 1858, Witmore Hall was put up for sale to satisfy Thomas Witmore’s debts.

The plantation, the house, the equipment, and all of the enslaved people were to be auctioned off to the highest bidder.

This was the moment Celeste had been waiting for, but it was also the moment of greatest danger.

If she was sold to a new owner, she might end up anywhere.

She might be taken far from Mississippi, far from any hope of finding her children.

She might be separated from everything she had worked for over the past 3 years.

She had one more card to play.

James Crawford, the cotton broker who had helped spread the information about Witmore, had become something unexpected over the past year.

He had become, if not an ally, than at least a useful contact.

Crawford had profited handsomely from Witmore’s downfall, buying up his debts at a discount and positioning himself to acquire choice pieces of the Witmore estate at the auction.

He was not a good man, but he was a practical one.

and Celeste had proven herself to be a valuable source of information.

She approached Crawford one last time a few weeks before the auction.

She told him that she wanted to be free.

She told him that she had more information.

Information about other planters in the county, secrets she had overheard during her years of service in the Witmore House.

She could be useful to him.

She said she could continue to gather information, continue to provide him with advantages over his competitors.

All she wanted in return was her freedom.

Crawford considered the offer.

He was a businessman, and he recognized a good deal when he saw one.

An enslaved woman who could read, who had proven herself capable of gathering and using sensitive information, who had connections throughout the domestic slave networks of Adams County.

Such a person was worth far more free than enslaved.

If he bought her and set her free, she would owe him.

She would work for him willingly out of gratitude and self-interest rather than under compulsion, and he would have a spy in places he could never go himself.

He agreed.

At the auction of the Witmore estate in October 1858, James Crawford purchased Celeste for $350.

One week later, he signed the papers that legally manumitted her, making her a free woman for the first time in her life.

She was approximately 36 years old.

She had spent more than two decades in slavery.

And now, finally, she could begin the work she had been planning since the day her children were taken from her.

Finding her children would not be easy.

The South in 1858 was a vast and hostile territory for a free black woman traveling alone.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 meant that any black person could be seized and claimed as a runaway with almost no legal protection.

Free papers could be stolen, destroyed, or simply ignored by white people who did not want to acknowledge them.

Traveling between states required navigating a maze of local laws and customs, any of which could result in imprisonment or worse.

And the people who had her children had no legal obligation to sell them, no matter how much money Celeste might offer.

But Celeste had advantages that most people in her position did not have.

She could read and write.

She had connections to James Crawford and through him to a network of merchants and traders who did business throughout the South.

She had spent three years gathering information about the slave trade, learning how it worked, understanding the roots and markets and paperwork that moved human beings from place to place, and she had a determination that nothing could shake.

She also had money, not much, but some.

Crawford had given her a small sum as part of their arrangement, enough to travel and support herself for a few months.

She supplemented this by working as a domestic servant in Nachez, saving every penny she could, building a fund that she would use to buy her children’s freedom.

Her first target was Samuel.

Samuel had been sold to Jeremiah Stone, a cotton planter in Moringo County, Alabama.

Celeste knew from Crawford’s business contacts that Stone was one of the plaintiffs in the lawsuit against Whitmore, which meant he was angry, which meant he might be willing to negotiate.

She traveled to Alabama in the spring of 1859, carrying her free papers and letters of introduction from Crawford, and she presented herself at Stone’s plantation.

The meeting did not go well at first.

Stone was suspicious of a free black woman traveling alone, asking questions about one of his slaves.

He threatened to have her arrested as a troublemaker.

But Celeste was calm and persistent.

She explained that Samuel was her son.

She explained that she had money.

She offered to buy him at a fair price, higher than what Stone had originally paid.

She appealed to his self-interest, pointing out that he was still entangled in expensive litigation with Whitmore, and that selling Samuel to her would be one less complication in his life.

Stone thought it over.

He had never been comfortable with Samuel, not since learning the truth about the boy’s parentage.

The presence of a white man’s son among his slaves was an awkward reminder of things he preferred not to think about, and Celeste was offering cash money, more than the boy was worth on the open market.

He agreed to sell.

The price was $500, more than Celeste had.

She returned to Mississippi and spent 6 months working and saving, borrowing small amounts from Crawford and from free black communities in Nachez who supported her cause.

By the fall of 1859, she had the money.

She returned to Alabama, paid Jeremiah Stone, and walked out of his plantation with her son.

Samuel was 15 years old.

He barely recognized his mother.

He had spent four years as a field hand, working from dawn to dusk, beaten when he slowed down, half starved during lean times.

The boy who had fought against the men who took him was now a young man with scars on his back and a weariness in his eyes that broke Celeste’s heart.

But he was alive.

He was free, and he was with her.

They traveled back to Mississippi together and Celeste immediately began planning for the next rescue.

Eliza was in New Orleans, still owned by the Bowmont family.

This would be more complicated.

New Orleans was a large city with a complex slave market, and the Bowmonts were a wealthy family who might not want to sell.

But Celeste had learned from her first success.

She knew that patience and persistence could overcome obstacles that seemed impossible.

She traveled to New Orleans in early 1860 and spent weeks gathering information about the Bowmont household.

She learned their routines, their financial situation, their social connections.

She learned that Eliza had become a skilled seamstress, which made her more valuable, but also that the family was preparing to move to France to escape the growing tensions over slavery that were dividing the country.

They would not want to take their slaves with them.

They would be looking to sell.

Celeste positioned herself as a buyer.

She used Crawford’s connections to present herself as a representative of a free black community in Ohio that was looking to purchase enslaved people and bring them north to freedom.

It was a story that was plausible enough to be believed, and it gave her a cover that protected her from too many questions.

The Bowmonts agreed to sell Eliza for $600.

It was more money than Celeste had ever seen in one place.

But she had been preparing.

She had saved.

She had borrowed.

She had done everything necessary to have the funds ready when the moment came.

In March of 1860, Celeste bought her daughter’s freedom.

Eliza was 13 years old.

She was thin and quiet with eyes that seemed too old for her face.

She had spent nearly 5 years serving in the Bowmont household, learning to sew and clean and make herself useful, learning to be invisible the same way her mother had learned decades before.

When Celeste found her and told her who she was, Eliza did not cry.

She did not speak.

She simply stared at her mother for a long moment, and then she nodded as if she had always known this day would come.

Now Celeste had two of her children.

But Isaiah was still missing.

Finding Isaiah was the hardest task of all.

He had been sold to a sugar plantation in Louisiana, but Celeste had never been able to determine exactly which one.

Sugar country was a different world from the cotton plantations she knew, more brutal and more deadly.

Enslaved people on sugar plantations had shorter life expectancies than almost anywhere else in the South.

worked to death in the grinding mills and the boiling houses where raw cane was processed into sugar.

A child sold into that world at 5 years old might not have survived to 10.

Celeste spent more than 2 years searching for her youngest son.

She traveled throughout Louisiana following rumors and leads that often turned out to be false.

She bribed overseers and clerks for access to plantation records.

She questioned enslaved people who might have seen a boy matching Isaiah’s description.

She faced danger constantly from suspicious white people who did not like free blacks asking questions.

From slave catchers who saw an opportunity to kidnap her and sell her back into bondage.

From the simple hazards of travel in a region on the brink of civil war.

The war itself complicated everything.

When Confederate forces fired on Fort Sumpter in April 1861, the South erupted into chaos.

Travel became dangerous and unpredictable.

The networks that Celeste had relied on for information were disrupted.

Many of the people who had helped her were now focused on survival rather than the concerns of one woman searching for her child.

But Celeste did not give up.

She could not give up.

She had not come this far.

had not destroyed a powerful white man and freed herself and rescued two of her children only to abandon the third.

Isaiah was out there somewhere and she would find him or die trying.

She found him in the spring of 1863.

Isaiah was on a plantation called Belter about 50 mi west of New Orleans.

He was 12 years old.

He had survived 8 years in the sugar fields which was remarkable in itself.

But survival had come at a cost.

Isaiah was small for his age, malnourished and scarred.

He walked with a limp from an old injury that had never healed properly.

And when Celeste finally found him and told him who she was, he did not know her.

He had been 5 years old when he was taken.

He had no memory of his mother’s face, no memory of her voice, no memory of the songs she used to sing to him at night.

For Isaiah, Celeste was a stranger, a woman who appeared out of nowhere, claiming to be his family.

He was suspicious and frightened and angry all at the same time.

But Celeste was patient.

She had spent years being patient.

She could wait a little longer.

The purchase of Isaiah’s freedom was different from the others because of the war.

Beltier was in Union occupied territory by the spring of 1863 and the Emancipation Proclamation had theoretically freed all enslaved people in Confederate states.

But the reality on the ground was more complicated.

Many enslaved people were still held in bondage by masters who refused to acknowledge the proclamation.

Many others had fled to Union lines and were living in contraband camps, free in name but struggling to survive.

The legal status of people like Isaiah was unclear, and the plantation owners were doing everything they could to maintain control over their workforce.

Celeste did not try to buy Isaiah.

Instead, she went to the union officers who were administering the region, and she told them her story.

She showed them her free papers and the papers for Samuel and Eliza.

She told them about Thomas Witmore and what he had done, about the sale of his own children, about the systematic fraud and cruelty that had defined his life.

And she asked them to help her retrieve her son.

The officers were moved by her story.

Perhaps they recognized the propaganda value of a narrative that illustrated the horrors of slavery so perfectly.

Perhaps they were simply decent men who wanted to do the right thing.

Whatever their reasons, they sent soldiers to Belter and they brought Isaiah out.

Celeste held her youngest son for the first time in 8 years.

He was stiff in her arms, uncertain, still unable to believe that this was real, but she held him anyway, and she whispered to him that everything would be all right now.

She told him that she had been looking for him for so long.

She told him that she would never let him go again.

It took months for Isaiah to trust her.

It took years for him to begin to heal from what had been done to him.

But Celeste was patient.

She had always been patient.

And slowly, carefully, she rebuilt the family that Thomas Whitmore had tried to destroy.

As for Whitmore himself, his story ended exactly as Celeste had planned.

After the sale of his plantation and all his property, Thomas Whitmore was left with nothing.

The lawsuits consumed whatever remained of his assets.

His creditors took everything they could take.

He moved into a boarding house in Nachez, where he lived in a single room and drank himself into oblivion day after day.

The man who had once dreamed of being one of the great planters of Mississippi was now a penniless drunk who could not walk down the street without people pointing and whispering.

The war finished what Celeste had started when Union forces occupied Nachez in 1863.

Whitmore lost even the small income he had been making from investments in Confederate bonds.

He was arrested briefly as a Confederate sympathizer, though he had never actually supported the southern cause with anything more than words.

After his release, he returned to his boarding house and continued drinking.

Thomas Whitmore died in 1864, alone in his rented room from liver failure brought on by years of alcoholism.

He was 52 years old.

Nobody came to his funeral except the minister, who was paid to say a few words over the grave.

His legitimate sons, who had survived the war, did not attend.

His wife, Margaret, was still alive in the asylum in Jackson, unaware that her husband had died.

The newspapers did not mention his passing.

The man who had sold his own children for $1,000 died forgotten and unmorned, exactly as he deserved.

Celeste outlived him by nearly 30 years.

After the war ended, she settled in Ohio with her three children.

Samuel became a carpenter, building houses for the growing black community in Cincinnati.

Eliza became a seamstress, as she had been trained and eventually opened her own dress shop that served both black and white customers.

Isaiah, despite his difficult start in life, learned to read and write and eventually became a teacher, dedicating his life to educating black children who had been denied the knowledge that could set them free.

Celeste never remarried.

She never fully trusted any man after what Thomas Whitmore had done to her, but she was not alone.

She was surrounded by her children and eventually by grandchildren who called her mama Celeste and listened to her stories about the old days, about what slavery had been like, about what she had done to survive and to save the people she loved.

She told them about patience.

She told them about the power of knowledge, about how learning to read had given her weapons that no one could take away.

She told them about the importance of remembering, of never forgetting what had been done to their people so that it could never happen again.

She did not often speak about revenge.

But sometimes late at night when the grandchildren were asleep, and it was just her and her adult children sitting together, she would smile a small private smile and say that there were many kinds of justice in this world.

Some justice came from courts and laws.

Some justice came from God, and some justice came from the people who refused to accept that they were powerless, who watched and waited and planned until the moment was right, and who then brought down their enemies with nothing but truth and patience and an unbreakable will.

Celeste died in 1891 at the age of approximately 69.

She was buried in a cemetery in Cincinnati, surrounded by her children and grandchildren and great grandchildren.

Her grave marker, paid for by her descendants, bore a simple inscription that she had chosen herself.

It read, “She found her children.

” By the time of her death, Celeste had more than 20 living descendants.

Every single one of them was free.

Every single one of them knew the story of how their ancestor had been enslaved, had been violated, had watched her children be sold away from her.

And every single one of them knew how she had responded, not with violence, not with despair, but with intelligence, with patience, and with a love so powerful that it could not be defeated by any cruelty the world could devise.

Thomas Whitmore had believed that he could do anything to Celeste because she was his property.

Because the law said she had no rights, because the entire structure of southern society was built to protect men like him and crush women like her.

He was wrong.

The system that seemed so powerful, so permanent, so impossible to challenge was built on lies and cruelty and the systematic denial of human dignity.

and systems built on such foundations are always more fragile than they appear.

Celeste understood something that Witmore never did.

She understood that power is not always visible.

It does not always come from wealth or weapons or legal authority.

Sometimes power comes from knowing what your enemy wants to hide.

Sometimes it comes from patience, from the willingness to wait years for the right moment.

Sometimes it comes from love, from the desperate determination of a mother who will move heaven and earth to save her children.

The enslaved woman that Thomas Witmore thought he owned turned out to be the architect of his destruction.

The children he sold like livestock grew up to be free citizens of a nation that had abolished the institution that once held them in chains.

The family he tried to scatter across three states came back together and built a legacy that would outlast his name by generations.

Some debts are not paid in money.

Some debts are paid in ruin.

And some chains, the chains of determination and love and righteous anger are strong.

News

Ilhan Omar ‘PLANS TO FLEE’…. as FBI Questions $30 MILLION NET WORTH

So, while Bavino is cracking down in Minnesota, House Republicans turning the heat up on Ilhan Omar. They want to…

FBI & ICE Raid Walz & Mayor’s Properties In Minnesota LINKED To Somali Fentanyl Network

IC and the FBI move on Minnesota, touching the offices of Governor Tim Walls and the state’s biggest mayors as…

FBI RAIDS Massive LA Taxi Empire – You Won’t Believe What They Found Inside!

On a Tuesday morning, the dispatch radios in hundreds of Los Angeles taxi cabs suddenly stopped playing route assignments. Instead,…

Brandon Frugal Finally Revealed What Forced Production to Halt in Season 7 of Skinwalker Ranch….

The Secret of Skinwalker Ranch became History Channel’s biggest hit. Six successful seasons documenting the unknown with real science and…

1 MINUTE AGO: What FBI Found In Hulk Hogan’s Mansion Will Leave You Shocked….

The FBI didn’t plan to walk into a media firestorm, but the moment agents stepped into Hulk Hogan’s Clearwater mansion,…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage… It started like any other evening…

End of content

No more pages to load