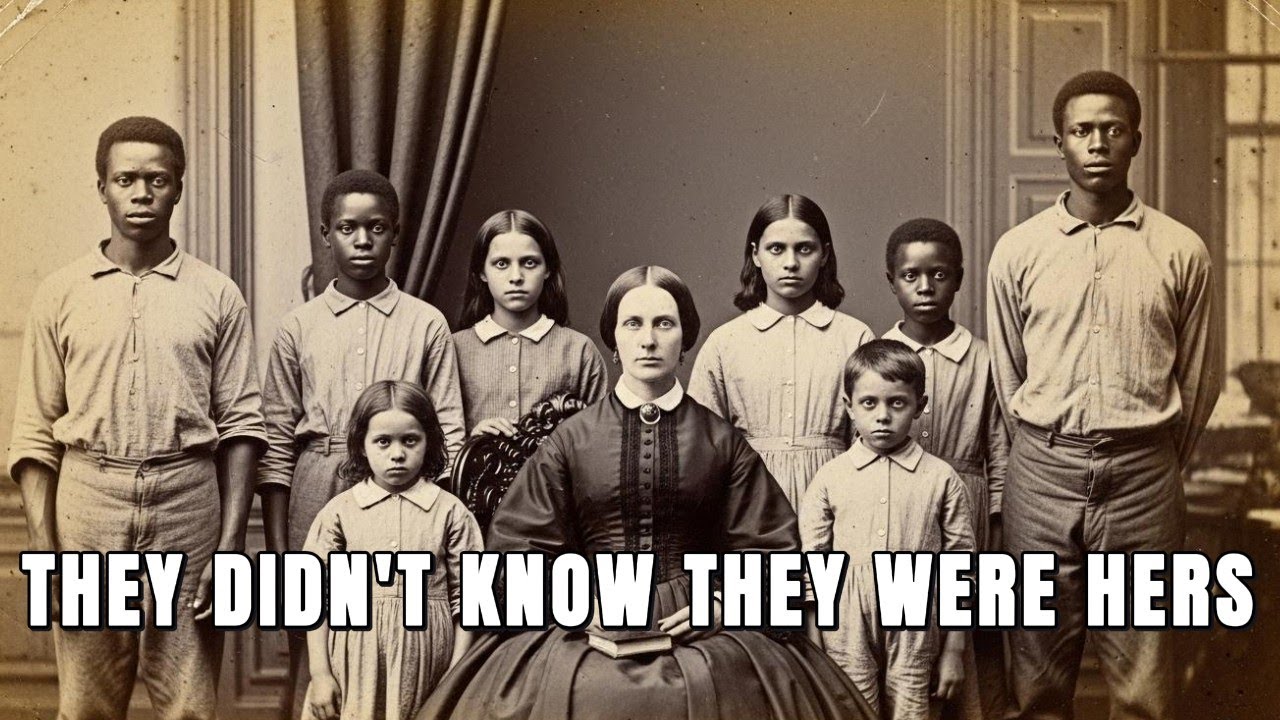

The Forgotten Horror of Thornhill Estate: The Widow, the Children, and the Plantation That History Tried to Bury

In the spring of 1864, Union soldiers breaking through a locked iron door beneath a Georgia plantation made a discovery so disturbing that official records would bury it for more than a century.

Inside the basement of Thornhill Estate, a decaying property outside Waynesboro, Georgia, 23 children were found huddled together in the dark — pale, trembling, and malnourished.

The oldest, a 13-year-old girl, reportedly told one officer, “Mistress says we are her legacy. We cannot leave because we are her blood.”

All 23 shared the same distinctive features — high cheekbones, pale green eyes, and auburn hair streaked with gold.

For the soldiers who liberated them, the horror of that night defied comprehension. For historians who later uncovered the buried records, it redefined the meaning of cruelty on America’s plantations.

Because Thornhill wasn’t just another relic of the Confederacy. It was the site of what scholars now describe as “a systematic program of human breeding” — conceived, designed, and carried out by a woman named Katherine Danforth Thornhill, the widow who built a dynasty out of blood.

The Widow and Her Secret

When her husband Jonathan Thornhill died in 1847, Katherine was just 28 — educated, proud, and dangerously intelligent. Left with crushing debts and a failing cotton plantation, she refused to return to her father’s home in Augusta.

In her journals, written in cipher and discovered years later, she outlined what she called “the cultivation plan.”

Unable to afford new laborers, she decided to create them.

“If I cannot purchase workers,” she wrote, “I shall grow them — strong, loyal, and tied to this estate by blood.”

Katherine’s idea was as chilling as it was calculated: she would select the strongest enslaved men on the plantation to father her children, raise those children as both heirs and laborers, and continue breeding future generations who were, in her words, “bound to Thornhill by nature as well as law.”

It wasn’t a secret for long. Her teenage stepson, Richard, discovered the coded journals. What he read horrified him — diagrams of human pairings, notes about “desirable traits,” even a plan for how her descendants would “sustain the estate for a hundred years.”

Days later, Richard fell mysteriously ill. Within weeks, he was dead. Catherine buried him quietly and recorded in her journal: “Necessary pruning complete.”

“Plantings” and “Harvests”

Between 1847 and 1856, Katherine bore seven children, all fathered by enslaved men she handpicked — Isaac, Thomas, Samuel, and others whose names appear briefly in her journals. She referred to them as “rootstock.”

Her entries were cold, methodical:

“First planting complete — healthy issue expected December.”

“Rootstock two performs adequately; will resume pairing in spring.”

Each birth was attended by a single midwife, Miriam Grayson, who received both payment and silence.

The men chosen for these “pairings” were later sold or punished to ensure secrecy. One, named Thomas, was publicly whipped before being forced into Katherine’s chambers. Another, Isaac, was sold to Alabama weeks after Katherine’s first son was born.

Over the next decade, Katherine’s household expanded — not through purchase, but through what she saw as “breeding success.” By the mid-1850s, Thornhill Estate had regained profitability, and its owner had transformed into something more dangerous than desperate: a visionary of her own delusion.

The “Heritage Room”

By 1859, Katherine had created what she called the Heritage Room — a private chamber in the east wing of the plantation house.

There, she kept three coded journals, glass vials containing locks of hair from each child, and charts mapping out her future “pairings.” On the walls, she drew family trees linking her offspring with other enslaved children — the next generation of “planned laborers.”

“Strong constitution,” one note read.

“Compliant temperament,” read another.

Katherine saw herself as a pioneer — a woman outsmarting a broken economy through “controlled reproduction.” What she was really doing was industrializing human life — and death.

When enslaved women conceived children outside her control, midwife Grayson administered forced abortions. When a 14-year-old girl named Sarah refused to “pair” with an older man Katherine had chosen for her, she was beaten and dead within days.

The plantation ran on terror and silence.

The Children of Thornhill

By 1860, Thornhill’s enslaved population appeared to be thriving. In reality, it was a hierarchy of horror.

Katherine’s “special children” — the ones she had birthed — lived in the main house. They were taught to read and write, dressed better than the others, and told they were “orphans” adopted out of Christian charity.

In secret, she measured their height, weighed them, and logged their growth in her breeding charts.

Her eldest son, Jonathan, shared her green eyes and temper. Her daughter, Eleanor, had inherited her intelligence — and would one day become the first to uncover the truth.

In 1863, Eleanor — then 14 — found one of her mother’s journals. She cracked the code and read the horrifying details of her conception:

“Second planting with rootstock two — Thomas, age 21. Excellent health. Expecting favorable issue.”

Thomas was one of the enslaved field hands. Eleanor realized what it meant: she was both her mother’s daughter and her father’s property.

When she confronted Katherine, the woman didn’t deny it.

“You are my blood,” Katherine said. “This is our family’s future. You will understand when you are older.”

Eleanor didn’t understand. She rebelled — quietly at first, whispering the truth to her siblings and the other enslaved women. But within months, the whispers became something more dangerous: a plan.

The Uprising

By 1864, the Civil War was tearing through Georgia. Sherman’s army was closing in. Hope — and anger — spread through the quarters.

When rumors reached Thornhill that freedom was coming, Katherine panicked. Her “experiment” was collapsing.

On the night of March 17, 1864, she gathered her children inside the Heritage Room. Oil lamps flickered against the walls lined with journals and vials of hair.

“They’ll come for us,” she said. “The Yankees will destroy everything we’ve built. But we can preserve our legacy.”

From a locked drawer, she produced bottles of laudanum.

“In small doses,” she explained, “it brings sleep. In larger doses — eternal peace.”

Her plan was clear: if the Union army freed the enslaved, she would rather kill her own children than see them live outside her control.

But her eldest son Jonathan — now 16 — stepped between her and the bottles.

“You’re not saving us,” he said. “You’re destroying us.”

For the first time in her life, Katherine lost control. She struck him. He didn’t move.

“You’re not my mother,” he said. “You’re our captor.”

Eleanor stood beside him. And together, they refused.

The Night the Mistress Vanished

What happened next has never been fully verified. Witness accounts conflict. But by dawn, Katherine Thornhill was gone.

Her journals were found trampled and muddy outside the quarters. The vials of hair shattered. The Heritage Room burned.

Union soldiers who arrived weeks later recorded only fragments:

“No trace of Mrs. Thornhill. Her Negroes refuse to speak of her.”

An old overseer told investigators that “the mistress must have fled before the Yankees came.”

But in Burke County’s Black community, the truth was whispered for generations: the people Katherine had enslaved rose up that night and erased her the way she had tried to erase them.

The Skeleton in the Well

Seven years later, in 1871, a farmer drilling a well on former Thornhill land hit something solid 30 feet below. When the hole was widened, workers found a skeleton — a woman, roughly 40 years old. Nearby lay a rusted locket with two miniatures: a man and a young boy.

The coroner ruled the cause of death “blunt force trauma to the skull.” The report listed her only as “Unknown Female, Found on Former Thornhill Property.”

But everyone in Burke County knew who she was.

The Legacy She Couldn’t Kill

After the war, Thornhill collapsed into ruin. The freed families left, scattering across Georgia. Eleanor moved to Savannah. Jonathan fled west and died in Texas under an assumed name. The plantation house burned and was eventually swallowed by forest.

But the story didn’t end there.

In 1923, a historian discovered a letter written by Union Captain Samuel Reynolds, the officer who had first entered Thornhill after the war:

“We discovered evidence of systematic breeding experiments conducted by the late mistress upon her own Negroes — and her own offspring. The details are too grotesque to repeat, but I am satisfied that whatever justice befell her was well deserved.”

And then there were the children — the 23 found in the basement. Some were placed with freedmen families. Others vanished into the chaos of Reconstruction.

Historians believe their descendants are still alive today — carrying, unknowingly, the blood of a woman who tried to engineer a human dynasty.

The Land That Refuses to Forget

Today, nothing remains of Thornhill but scattered bricks, collapsed wells, and whispers in the pine woods of Burke County. The county records make no mention of the estate. There is no historical marker, no museum, no plaque.

But locals still talk about the land — how birds refuse to nest near the ruins, how the ground stays colder there even in summer.

Some claim that on quiet nights, when the wind moves through the trees, you can still hear children’s voices beneath the earth — the last echoes of those who were once told they could never leave because “they were her blood.”

Thornhill Estate remains one of the darkest and least-known stories in American history — a place where power, delusion, and ownership combined into something almost unthinkable.

But perhaps what matters most is this: the people she enslaved outlived her. The legacy she tried to control was the one she could never possess — the unbroken line of survivors who carried their freedom, and her downfall, into history.

💀 What really happened the night the mistress vanished? What else lies buried under the red clay of Burke County? Some secrets, it seems, refuse to stay buried forever.

News

Archaeologists Just Opened King Henry VIII’s Sealed Tomb — What They Found Is Unbelievable

Archaeologists Just Opened King Henry VIII’s Sealed Tomb — What They Found Is Unbelievable For centuries, people assumed King Henry…

Ilhan Omar in BIG TROUBLE…. Husband’s Winery Mirrors Minnesota Somali FRAUD

Ilhan Omar in BIG TROUBLE…. Husband’s Winery Mirrors Minnesota Somali FRAUD It’s we’re just we’re just uh trying to like…

FBI & ICE Raid Minneapolis Mayor — Cartel Tunnels and $420,000,000 Network

FBI & ICE Raid Minneapolis Mayor — Cartel Tunnels and $420,000,000 Network Minneapolis, please search for it. I spoke in…

FBI & DEA Uncover 1,400-Foot Tunnel in Texas — $2,000,000,000 Cartel Network Exposed

Tangle of tunnels used to traffic not only drugs but also highlevel drug kingpins themselves. 4:20 a.m. A federal raid…

Before He Dies, Eustace Conway Finally Reveals the Truth He Hid for 20 Years

Before He Dies, Eustace Conway Finally Reveals the Truth He Hid for 20 Years Thousands of people have died in…

Ilhan Omar ‘PLANS TO FLEE’…. as FBI Questions $30 MILLION NET WORTH

So, while Bavino is cracking down in Minnesota, House Republicans turning the heat up on Ilhan Omar. They want to…

End of content

No more pages to load