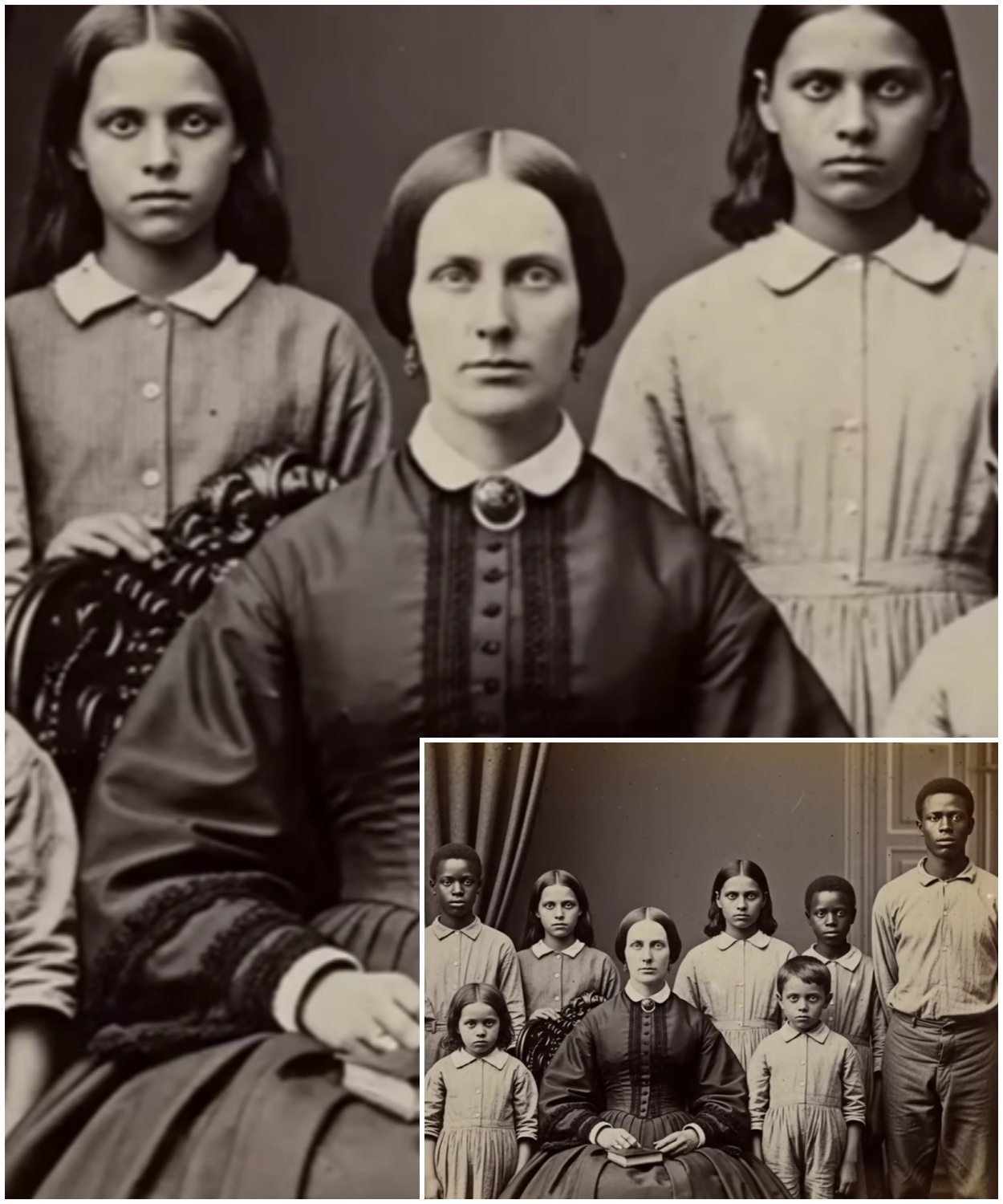

23 children were discovered locked in the basement of a Georgia plantation in 1864.

All bearing the same distinctive features, high cheekbones, pale green eyes, and auburn hair stre with gold.

When Union soldiers forced open the iron doors of Thornhill Estate in Burke County, they found these children huddled together in darkness, some as young as four, others approaching adolescence.

The eldest, a girl of 13, told the officers something that made veteran soldiers physically ill.

Mistress says we are her legacy.

We cannot leave because we are her blood.

Military records from the 34th Massachusetts Infantry mention the incident only once in a letter marked confidential and buried in regimental archives for over a century.

Local histories of Burke County omit Thornhill estate entirely as if the plantation and its mistress never existed.

But they did exist.

And what Katherine Thornnehill created in those 16 years between her husband’s death and the arrival of federal troops represents one of the most disturbing chapters in American history.

A systematic breeding program designed to create generations of enslaved people who could never escape their bondage because they were genetically tied to their owner.

To a cold February morning in 1847, when a young widow inherited a dying plantation and conceived a plan that would haunt Georgia for generations.

The winter Katherine Danforth Thornhill buried her husband was the coldest Burke County had seen in 20 years.

The Thornhill estate sat on 1700 acres of red clay soil 7 mi southwest of Wsboro, the county seat.

In 1847, Burke County was cotton country, though not as prosperous as the black belt regions further west.

The soil here was tired, overworked by decades of single crop farming.

Plantations that had flourished in the 1820s were struggling by the 1840s, squeezed between falling cotton prices and rising costs.

The Mexican War had drawn away laborers, and talk of territorial expansion divided communities along bitter lines.

Thornhill estate had once been among the more successful properties in the region.

Catherine’s late husband, Jonathan Thornnehill, had inherited it from his father in 1838 with 42 enslaved workers, adequate equipment, and manageable debt.

But Jonathan had been a poor manager and an enthusiastic gambler.

By the time a winter fever claimed him in February 1847, the estate was mortgaged to the hilt.

The fields were producing barely enough to feed the workers, and creditors were circling like buzzards.

Catherine was 28 when she became a widow.

She had married Jonathan when she was 19, a strategic match arranged by her father, Theodor Danforth, a prominent merchant in Augusta.

The Danfors were old Georgia money, descended from settlers who had arrived in the 1730s.

Catherine had been educated by private tutors, spoke French passibly well, and had been raised with expectations of managing a substantial household.

What she had not expected was to inherit a failing plantation with crushing debts and a 16-year-old son who looked at her with something approaching hatred.

Richard Thornnehill was Jonathan’s son from his first marriage.

His mother had died giving birth to him in 1831, and Jonathan had remarried 5 years later.

Richard had never warmed to Catherine, viewing her as an interloper who had replaced his real mother.

He was a sullen, bookish boy who spent most of his time in the estate’s small library, avoiding both his stepmother and the practical work of running a plantation.

Catherine found him weak, impractical, and entirely too sentimental about the enslaved workers.

He had once suggested they should be taught to read, an idea so dangerous that Catherine had forbidden him from speaking of it again.

The plantation itself reflected its declining fortunes.

The main house was a two-story structure of whitewashed brick with six columns across the front portico built in 1805 in the federal style.

Paint peeled from the window frames and the roof leaked in three places.

The furniture inside was a mix of inherited pieces from Jonathan’s family and cheaper replacements purchased when the good pieces had been sold to pay gambling debts.

Behind the main house stood the kitchen building, the smokehouse, the dairy, and the overseer’s cottage, all in similar states of disrepair.

Further back, beyond a line of live oaks draped with Spanish moss, were the quarters where the enslaved population lived.

In 1847, 31 people remained on the property.

11 men, 13 women, and seven children.

16 others had been sold off over the previous 3 years to satisfy Jonathan’s creditors.

Those who remained knew that more sails were coming.

Fear hung over the quarters like fog over the Savannah River.

Catherine spent the first month after Jonathan’s death in a kind of controlled fury.

She met with the estates’s lawyer, Ambrose Talbbert, who laid out her options in blunt terms.

sell the property and the remaining workers to settle the debts and perhaps have enough left over to live modestly in Augusta under her father’s roof, or find some way to make the plantation profitable again, which Talbbert considered unlikely given the state of the cotton market and the estate’s depleted resources.

Neither option was acceptable to Catherine.

Returning to Augusta would mean admitting failure, living as a dependent spinster in her father’s house, forever marked as the widow who couldn’t hold onto her inheritance.

But she also recognized that traditional plantation management wouldn’t save Thornhill estate.

The land was worn out.

The equipment was old.

The remaining enslaved workers were insufficient in number to work the cotton fields profitably, and she had no money to purchase more.

It was during one of these sleepless nights pouring over the estates account books by candlelight that Catherine conceived her plan.

The idea came to her with the cold logic of desperation.

If she couldn’t afford to purchase workers, she would breed them, but not in the haphazard way most plantations did it, offering minor incentives for couples to have children and waiting 15 years for those children to become productive laborers.

No, Catherine envisioned something far more systematic, more controlled.

She would create a population of workers who were biologically tied to the estate, who could never be sold because they were her own descendants, who would have an instinctive loyalty to the plantation because it was literally in their blood.

The plan was monstrous.

But to Catherine, it was also elegant.

She was still young enough to bear children.

She would select the strongest, healthiest men among the enslaved population and conceive children with them.

These children would be raised knowing their parentage, would be given slightly better treatment than the others to ensure their loyalty, and when they reached maturity, would be paired with enslaved women to produce the next generation.

Within 20 years, Katherine calculated she could have a workforce of 50 or more, all bound to Thornhill estate by ties that went deeper than legal ownership.

She began keeping a journal to work out the details.

This was no diary of personal feelings.

Catherine was far too practical for that.

Instead, she created what she called her cultivation records filled with calculations, observations, and plans.

she wrote in a simple substitution cipher, replacing key words with innocuous agricultural terms.

Children became seedlings.

The men she selected became roottock.

Pregnancies were plantings.

The journal’s pages were covered with diagrams that looked like breeding charts for livestock because that was essentially what they were.

Catherine’s first selection was a man named Isaac, 24 years old, born on the plantation and known for his physical strength and steady temperament.

She summoned him to the main house on a March evening in 1847 after the other workers had retired to the quarters.

What happened that night was recorded in Catherine’s journal only as first planting completed with rootstock one, weather clear and mild.

3 weeks later, she summoned him again and then twice more before the month ended.

By April, Catherine was confident she was pregnant.

She recorded this in her journal with the same emotional detachment she might note the planting of cotton.

Initial cultivation successful.

Anticipate harvest in December.

Richard Thornnehill first suspected something was wrong with his stepmother in late May of 1847.

He noticed she had stopped taking her morning rides around the property, claiming the heat bothered her, even though the Georgia summer had barely begun.

She took her meals in her room more frequently, and had dismissed the house servant who usually attended her, preferring to manage her own affairs.

For a woman as concerned with appearances as Catherine, this withdrawal was unusual.

But it was a conversation Richard overheard in early June that truly alarmed him.

He had been in the library hidden behind one of the tall bookcases when Catherine met with Miriam Grayson in the adjacent parlor.

Mrs.

Grayson was the local midwife, a sharp-featured woman of 50 who attended births for both white and enslaved families throughout Burke County.

Richard knew her slightly.

She had a reputation as a skilled practitioner, but also as someone who asked few questions and kept confidences.

Absolutely.

You’re certain of your condition, Mrs.

Grayson asked in her clipped professional tone.

Quite certain, Catherine replied.

I should think sometime in early December.

And Mr.

Thornhill passed in February, you said.

There was a pause.

Richard pressed himself against the bookcase, hardly breathing.

My late husband and I were intimate in January, Catherine said evenly.

Shortly before his final illness.

Of course, Mrs.

Grayson’s voice carried a note of something, not quite disbelief, but a careful neutrality.

I’ll need to examine you properly, and we should discuss the arrangements for the delivery.

Will you want me here at the house? I will, and I’ll need your discretion, Miriam.

Absolutely.

You have it, as always.

Richard waited until both women had left the room before emerging from his hiding place.

His hands were shaking.

The mathematics didn’t work.

His father had been bedridden for the entire month of January, barely conscious most days, racked with fever and chills.

Richard had sat with him many nights.

There had been no possibility of intimate relations between his father and Catherine, which meant the child Catherine was carrying had been conceived after Jonathan’s death in March or April with someone else.

The implications made Richard sick to his stomach.

If word got out that Catherine had conceived a child out of wedlock, the scandal would destroy what little remained of the family’s reputation.

Creditors would move immediately to seize the property.

The Danforth family in Augusta would disown her.

But beyond the practical consequences, Richard was appalled by the deception itself.

Catherine intended to claim this child as his father’s legitimate heir, to lie to everyone, to build her future on a foundation of fraud.

He considered his options.

He could confront Catherine directly, but he was only 16, and she held all legal authority over the estate.

He could go to lawyer Talbert in Wesborough.

But without proof, it would be his word against Catherine’s, and as a minor, his testimony would carry little weight.

he could write to his grandfather Danforth in Augusta.

But Catherine read all outgoing mail from the estate.

Instead, Richard began to watch Catherine carefully, looking for evidence, trying to understand what she was planning.

He noticed that she summoned Isaac to the main house regularly, always after dark, always when the overseer was away in town or occupied with duties elsewhere on the property.

He saw how Catherine’s manner toward Isaac was different from her treatment of other enslaved workers, not kind exactly, but less overtly hostile.

She spoke to him in full sentences rather than curt commands.

By July, Richard was certain Isaac was the father of Catherine’s child.

The realization filled him with horror, not just at the violation of social and legal boundaries, but at what it revealed about Catherine’s character.

She had coldly, deliberately chosen to conceive a child with an enslaved man, to claim that child as her late husbands, and to maintain this lie indefinitely.

What kind of woman was capable of such calculated deception? He found part of the answer in early August during one of Catherine’s rare trips to Wesboro.

Richard had been searching for legal documents related to the estate.

He had vague thoughts of finding something that might give him leverage over Catherine when he discovered a leather-bound journal hidden in a locked drawer of Catherine’s writing desk.

The lock was simple enough for a determined 16-year-old to pick.

The journal was written in cipher, but Richard had always been good with puzzles.

It took him 3 days, working in secret whenever Catherine was out of the house to crack the basic substitution pattern.

What he read made his blood run cold.

Catherine wasn’t just having an affair with Isaac.

She was implementing a deliberate breeding program.

The journal laid it out in chilling detail.

her plan to conceive multiple children with selected enslaved men, to raise those children as part of the plantation workforce, and eventually to breed those children with each other and with other enslaved people to create an everexpanding population of workers who would be genetically tied to Thornhill Estate and to Catherine herself.

There were charts, calculations of expected births over 5-year periods, notes on which men displayed desirable physical characteristics, speculation about whether traits like strength, intelligence, and temperament were heritable.

It read like something from a livestock breeders manual, except the livestock were human beings.

Richard copied several pages of the journal, translating the cipher into plain English, his hand shaking so badly he could barely hold the pen.

This was evidence.

This was proof of Catherine’s depravity.

He could take this to the authorities.

He could expose her.

But that night at dinner, Catherine looked at him with those cold green eyes and said casually, “Richard, have you been in my study recently? Some of my papers seem to have been disturbed.

” “No, ma’am.

” Richard lied, his throat tight.

I keep certain documents locked away for good reason, Catherine continued, cutting her meat with precise strokes.

If I ever found that someone had violated my privacy, broken my trust in such a fundamental way, I’m afraid I would have to take serious action.

Do you understand? Yes, ma’am.

Good.

Because family loyalty is everything, Richard.

Everything.

Without it, we’re simply animals tearing at each other.

She smiled, but it didn’t reach her eyes.

I know you loved your father very much.

I would hate for his memory to be tarnished by scandal, especially scandal that might emerge from within his own household.

The threat was clear.

If Richard tried to expose Catherine, she would find a way to turn it back on him, to paint him as a disturbed, resentful stepson inventing lies about a grieving widow.

Who would people believe? a respected plantation mistress from a prominent family or an awkward teenage boy with known resentment toward his stepmother.

Richard returned to his room that night and burned the pages he had copied, but he kept watching Catherine, and he began to feel increasingly unwell.

It started with fatigue.

By September, Richard found himself exhausted by mid-afternoon, unable to focus on his books.

His appetite diminished.

He developed frequent headaches that made it difficult to think clearly.

By October, he was experiencing muscle weakness and occasional stomach pains.

Catherine showed great concern.

She insisted Richard stay in bed.

She prepared his meals herself, bringing him bowls of soup and plates of soft foods.

She summoned Mrs.

Grayson to examine him.

The midwife, who also served as a general medical practitioner in the absence of a proper physician, diagnosed nervous exhaustion complicated by possible consumption.

She prescribed rest, fresh air when Richard felt strong enough, and a special tonic that Catherine obtained from a pharmacy in Augusta.

“Tuberculosis often strikes young men of sensitive disposition,” Catherine told Richard, adjusting his pillows with attentive care.

Your father had a cousin who died of it at just your age.

We must be very vigilant.

Richard knew better.

He had read about arsenic poisoning during his hours in the library.

He recognized the symptoms in himself, the fatigue, the digestive troubles, the muscle weakness.

Catherine was slowly killing him, disguising murder as disease, eliminating the one person who knew her secret and posed a threat to her plans.

But he was too weak to fight back, too isolated to get help.

The house servants followed Catherine’s orders absolutely.

The overseer rarely came to the main house.

Richard’s room was on the second floor, and by November, he barely had the strength to get out of bed, let alone escape the property and reach Wesboro.

He made one final attempt to expose Catherine in late November, writing a letter to his grandfather, Danforth, in Augusta.

It took him 3 days to compose it, working for a few minutes at a time before exhaustion overwhelmed him.

He described Catherine’s breeding program, her journal, the poisoning.

He sealed the letter and gave it to one of the younger house servants, a girl named Pearl, begging her to post it in Wesboro without telling Catherine.

Pearl took the letter, but she also told Catherine, terrified of what would happen if the mistress discovered she’d been keeping secrets.

Catherine read the letter expressionless, then burned it in the fireplace in front of Richard.

“You’re very ill, darling,” she said softly, almost tenderly.

“The fever is affecting your mind.

You’re imagining things that aren’t real.

It’s a mercy really that you won’t have to suffer much longer.

” Richard Thornnehill died on December 3rd, 1847, 3 weeks before his 17th birthday.

Dr.

Samuel Pritchard from Wesboro, summoned to record the death, noted consumption as the cause, and remarked that the young man had wasted away with tragic speed.

Catherine wept decorously at the funeral.

She wore black for a full year.

4 days after Richard’s burial, Catherine gave birth to a healthy son.

She named him Jonathan after her late husband and claimed he had been born slightly premature, which explained any questions about timing.

Few people in Burke County thought to count backwards from the birth to Catherine’s widowhood.

Those who did kept their speculations to themselves.

It was not the kind of thing one discussed openly.

The years between 1848 and 1856 transformed Thornhill Estate in ways that seemed almost miraculous to outside observers.

The plantation that had teetered on the edge of bankruptcy slowly regained its footing.

Cotton production increased.

The enslaved workforce grew.

Katherine Thornnehill earned a reputation as a shrewd, if somewhat reclusive, plantation mistress who managed her property with uncommon efficiency.

But that efficiency came at a terrible cost that no outsider ever saw.

Catherine gave birth four more times between 1848 and 1853.

Daughters named Elellanena, Abigail, and Margaret, and another son she called Samuel.

Each birth was attended only by Miriam Grayson, who by now was deeply complicit in Catherine’s schemes.

The midwife received generous payment for her services and her silence, regular fees that far exceeded her normal rates, plus a small cottage on the edge of the Thornhill property where she could live without paying rent.

Mrs.

Grayson’s role extended far beyond delivering Catherine’s children.

She also performed a darker function, ensuring that enslaved women on the property only gave birth to children who fit Catherine’s careful plans.

When pregnancies occurred outside Catherine’s controlled pairings, and they did, because human beings will form attachments and intimate relationships, even in the most oppressive circumstances, Mrs.

Grayson provided abortifants, plant-based compounds that induced miscarriages.

She performed these procedures in a small room behind the overseer’s cottage, away from the main house, away from witnesses.

The women subjected to these forced abortions rarely spoke of them, even to each other.

The trauma was profound, the grief unvoicable in a system that already denied them autonomy over their own bodies.

But whispers circulated through the quarters anyway.

Stories of women who had been pregnant one week and bleeding the next, who were told they had simply lost the babies naturally, though everyone knew Mrs.

Grayson had been involved.

One woman named Ruth tried to resist.

In the spring of 1851, she was 5 months pregnant when Catherine discovered that the father was not the man Catherine had designated for her, but instead a young field hand named Samuel, with whom Ruth had formed a genuine attachment.

Catherine ordered Mrs.

Grayson to terminate the pregnancy immediately.

Ruth ran.

She made it nearly four miles into the pine forests southwest of the plantation before the overseer’s dogs tracked her down.

She was dragged back to Thornhill Estate, held down by two men while Mrs.

Grayson forcibly administered the abortacient compounds.

Ruth survived the ordeal physically, but something fundamental broke inside her.

She worked mechanically after that, spoke rarely, and died 2 years later during a fever outbreak that swept through the quarters.

She was 24 years old.

But Ruth’s tragedy was just one among many.

By 1856, Catherine’s program had produced seven children of her own, all of whom were being raised in a peculiar liinal space.

They were legally enslaved.

Catherine had registered them as such in the county records, claiming them as children born to enslaved women on the property, which gave her legal ownership of them, but in practice they lived in the main house, wore decent clothes, ate better food than the other enslaved children, and received informal education from Catherine herself.

Young Jonathan, the eldest, was 8 years old in 1856.

He was a serious, quiet child who resembled Catherine strongly.

The same green eyes, the same auburn hair, the same sharp features.

He had no memory of his father, Isaac, who had been sold to a plantation in Alabama in 1849.

Catherine had found Isaac’s presence a complication once his purpose had been served.

The money from his sale helped pay down some of the estate’s remaining debts.

The younger children knew nothing of their true parentage.

Catherine told them they were fortunate orphans whom she had taken into her household out of Christian charity.

She taught them to read and write, a dangerous illegality in Georgia, where teaching enslaved people literacy was prohibited by law.

But Catherine was confident no one from the outside would ever enter her home and discover what she was teaching these children.

She was grooming them, preparing them for the next phase of her plan.

But that phase required patience.

The children needed to reach physical maturity before they could be used for breeding.

Catherine continued her meticulous recordkeeping, tracking their growth, their health, their temperaments.

She noted which children showed physical strength, which seemed more intelligent, which were more compliant.

She was planning pairings decades in advance.

In the meantime, she continued having children of her own.

Three more were born between 1854 and 1856.

Sons named William and Henry and a daughter called Caroline.

Each had a different father carefully selected from among the enslaved men on the property.

Catherine’s criteria were ruthlessly practical.

Physical health, strength, decent teeth, good eyesight, no obvious impairments.

She cared nothing for their personalities or characters.

They were, in her mind, simply genetic material to be utilized.

The men themselves had no choice in the matter.

When Catherine summoned them to the main house, they came, knowing that refusal would mean brutal punishment or sale.

Some of them understood what was happening, that the children Catherine bore would be their own biological offspring, even as those children would be raised to think of Catherine as their benefactors and savior.

The psychological torture of this situation was extreme.

They were forced to become fathers to children they could never acknowledge, never parent, never protect.

One man named Thomas was summoned to the main house in 1855.

He was 26 years old, married to a woman named Hannah, who lived in the quarters.

Hannah was pregnant with their first child.

When Thomas learned that Catherine intended to use him for breeding, he tried to refuse.

The overseer, a brutal man named Virgil Cain, had Thomas whipped in front of the assembled enslaved population.

39 lashes that left his back scarred for life.

Then Catherine had him brought to the main house anyway.

Thomas complied.

He had no other choice.

But he never spoke to Hannah about what happened in the main house, and Hannah never asked.

Some knowledge was too poisonous to voice.

By 1856, Thornhill Estate housed a population that looked normal on the surface, but was actually structured along Catherine’s twisted logic.

There were the field workers, about 20 adults and their children, who worked the cotton and corn under the overseer’s supervision.

There were the house servants, three women and one elderly man, who cooked, cleaned, and maintained the domestic space.

And then there were Catherine’s special children, 10 in total by 1856, ranging in age from 8 years old down to infancy.

These children occupied a strange position in the plantation hierarchy.

The other enslaved people resented them for their privileges, but also pied them for what they represented.

Everyone in the quarters understood on some level what Catherine was doing.

They didn’t have language for eugenics or breeding programs.

Those terms would come later, but they recognized the pattern.

They saw how Catherine kept detailed records of the children, how she measured them periodically, how she noted their development in her locked journal, and they waited with a kind of horrified anticipation for what would happen when these children grew up.

Because everyone knew what Catherine intended.

She had made it clear in subtle ways, in comments and instructions.

These children were being raised to produce the next generation of workers.

They were tools in Katherine’s long-term plan to create a workforce that could never leave, could never be sold because they were genetically bound to her and to Thornhill Estate.

It was an abomination disguised as innovation.

But in the isolated world of a rural Georgia plantation in the 1850s, with no outside oversight and absolute power concentrated in the hands of the property owner, Catherine was able to pursue her vision without interference.

The only person who posed any potential threat was lawyer Talbert in Wsboro, who handled the estate’s legal affairs and thus had access to records that might raise questions.

But Talbbert was a practical man who valued profitable clients.

And by 1856, Thornhill Estate was becoming profitable.

The cotton yields were improving.

The workforce was growing through Catherine’s breeding program at no acquisition cost.

Debts were being paid down.

Tolbert asked no uncomfortable questions because he benefited from Catherine’s success.

The isolation of the plantation helped maintain secrecy.

Thornhill Estate was 7 mi from Wesboro, connected by a rough road that was often impassible in winter.

Neighbors were few.

The nearest plantation was 3 mi away.

Catherine rarely entertained visitors and discouraged social calls.

When she did interact with other plantation families, usually at church on Sundays or at occasional gatherings in Wesboro, she presented herself as a proper widow, managing her late husband’s property with Christian virtue and practical wisdom.

No one suspected the systematic horror occurring behind the whitewashed brick walls of the main house and in the quarters beyond the oak trees.

And even if they had suspected, would they have cared? This was Georgia in the 1850s, a society built on the brutal exploitation of enslaved labor.

Catherine’s program was more systematic, more coldly calculated than most, but it was not fundamentally different in kind from what happened on thousands of other plantations across the South.

That was perhaps the most disturbing aspect of the entire situation.

Catherine’s breeding program was monstrous, but it was also logical within the framework of a society that already treated human beings as property to be bought, sold, and bred at will.

She had simply taken the underlying logic of slavery and followed it to one of its most horrifying conclusions.

But systems built on such profound injustice contain the seeds of their own destruction.

Change was coming to Georgia and the entire South, though in 1856, few people could imagine how soon or how violently it would arrive.

The late 1850s brought increasing tensions to Burke County and all of Georgia.

The question of slavery’s expansion into new territories dominated national politics.

The violence in Kansas territory where pro-slavery and anti-slavery settlers were literally killing each other was discussed in anxious tones at the courthouse in Wesboro.

The presidential election of 1856, which put James Buchanan in office, did little to resolve the fundamental conflicts tearing the country apart.

Catherine paid little attention to politics.

Her focus remained fixed on Thornhill Estate and her long-term program.

By 1859, her eldest children were approaching adolescence.

Jonathan was 11, Elellanena was 10, Abigail was nine.

They were still too young for the breeding phase of Catherine’s plan, but she was already making preparations, already selecting which of the enslaved young women would be appropriate partners when the time came.

It was during this period that Catherine constructed what she called the heritage room in a previously unused section of the mansion’s east wing.

She told the house servants it would be a storage space for family records and memorabilia.

In reality, it was a shrine to her breeding program.

The room was windowless, lit by oil lamps with walls lined with shelves and a large table in the center.

On the shelves, Catherine stored her coded journals.

three leatherbound volumes by 1859, chronicling every birth, every pairing, every observation about the children’s development.

She also kept small glass vials, each labeled with a name and a date containing locks of hair from each child.

These samples were arranged in rows organized by generation and parentage, a physical archive of her genetic experiments.

On the table, Catherine had drawn elaborate family trees in ink, showing not actual family relationships, but her planned pairings for future generations.

Lines connected names with notations about anticipated outcomes.

Strong constitution, good teeth, intelligent, compliant temperament.

It looked like breeding charts for show dogs or raceh horses, except the names were human.

Abigail paired with Thomas’s son, Jacob.

Eleanor with Isaac’s son, Marcus, who would be born in 1862.

Margaret with Samuel’s nephew, Peter.

Catherine spent hours in this room, planning decades into the future, imagining a Thornhill estate populated by a hundred or more workers, all descended from her, all genetically and psychologically bound to the land.

In her mind, she was creating something revolutionary.

A plantation that would never face labor shortages, never require expensive purchases of new workers, never risk mass escapes because the enslaved population would have nowhere else to go.

They were family in the most literal sense.

The practical implementation of this vision required Catherine to exert even tighter control over the plantation’s social structures.

She began separating the children into different groups based on their roles in her program.

The special children, her own biological offspring, continued living in or near the main house.

The other enslaved children were kept at a distance, sleeping in the quarters, working in the fields as soon as they were old enough.

But Catherine needed these other children, too.

They were necessary for the genetic mixing she envisioned.

So, she implemented a system of subtle manipulation.

offering small privileges to families who cooperated with their pairings, threatening separation and sale, to those who resisted.

The psychological pressure was immense and constant.

A woman named Violet, mother of three, found herself in an impossible position.

In 1860, Catherine had decided that Violet’s eldest daughter, a girl of 14 named Sarah, should be paired with one of the older field hands, a man in his 30s named Elijah.

Sarah was terrified she was still a child and Elijah was old enough to be her father.

Violet begged Catherine to wait to give Sarah more time.

Catherine’s response was cold.

You have two younger daughters, Violet.

Would you prefer I sell them to settle this matter? Or will Sarah do her duty to this estate and to you? Sarah was paired with Elijah that autumn.

She gave birth to a daughter 9 months later and died from complications of the delivery.

She was 15 years old.

Violet never recovered from the loss.

She continued working mechanically, speaking to no one, and in 1862, she walked into the Savannah River and drowned herself, but tragedies like Sarah and Violets were invisible to outside observers.

When visitors came to Thornhill Estate, which was rare, they saw a well-managed plantation with neat fields, a substantial house, and a workforce that appeared adequately fed and housed.

The horror was carefully hidden, buried in the quarters, locked in the heritage room, encoded in Catherine’s journals.

Then came 1860, and everything changed.

Abraham Lincoln was elected president.

South Carolina seceded from the Union in December.

Georgia followed in January 1861 with delegates at the secession convention in Milligville voting 208 to89 to leave the United States and join the Confederate States of America.

War came in April with the firing on Fort Sumpter.

Initially, many Georgians believed it would be a short conflict, a few months, perhaps a year, and the Confederacy would establish its independence.

But the war dragged on through 1861 into 1862 through 1863.

Young men from Burke County marched off to fight in Virginia and Tennessee.

Some returned in coffins.

Others didn’t return at all.

The war disrupted Catherine’s plans in ways she hadn’t anticipated.

The overseer, Virgil Ca, enlisted in the Confederate army in 1861 and was killed at Shiloh in April 1862.

Finding a replacement was difficult.

Most able-bodied white men were away at war.

Catherine eventually hired an elderly man named Silas Kendrick, who was too old for military service.

Kendrick was less brutal than Cain had been, but he was also less effective at maintaining discipline and control.

The enslaved population at Thornhill Estate began to sense the shifting power dynamics.

News filtered through the slave networks that connected plantations across Georgia.

whispered reports of Union victories, rumors that Lincoln had issued a proclamation freeing enslaved people in Confederate territory, speculation about what would happen if the Yankees came south.

Catherine tightened her control as best she could.

She confined the enslaved population to the plantation, forbidding anyone from leaving, even to visit relatives on neighboring properties.

She increased rations slightly to reduce the temptation to run away.

And she accelerated her breeding program, pushing some of the children into pairings earlier than she had originally planned.

Jonathan, her eldest son, turned 15 in December 1862.

Catherine decided he was ready.

She had selected a young woman named Rachel, 16 years old, the daughter of one of the field hands.

Rachel had no say in the matter.

In February 1863, Catherine arranged for Jonathan and Rachel to be married in a ceremony she conducted herself in the main house, a mockery of a wedding with no legal standing, designed purely to give a veneer of respectability to the breeding pairing.

Jonathan, who had been raised in isolation from the other enslaved people, and taught to think of Catherine as his benefactors, accepted this arrangement without question.

He had no understanding of what had been done to him, no awareness that Catherine was his biological mother, no sense of the profound wrongness of the entire situation.

Rachel, traumatized into silence, said nothing.

But others in the quarters were watching.

They saw Catherine pairing these special children, the ones she’d raised in the main house, with the other enslaved young people.

They understood this was the next phase of whatever Catherine had been planning all these years.

And a quiet, desperate rage began building in the quarters.

A rage that would have nowhere to go until circumstances finally shifted in their favor.

The spring of 1863 brought terrible news to Burke County.

Confederate losses were mounting.

The Union Army controlled the Mississippi River after the fall of Vixsburg.

In July, Lee’s invasion of Pennsylvania ended in disaster at Gettysburg.

Shortages of food, cloth, and basic supplies made life increasingly difficult, even for white plantation families.

For the enslaved population, conditions became harsher still as Catherine rationed everything more severely.

But something else was happening at Thornhill Estate, something Catherine tried desperately to hide from the outside world.

The children she had been breeding and raising were becoming aware of their true parentage.

It began with Elellanena, Catherine’s secondborn daughter, now 14 years old.

She had always been the most observant of Catherine’s children, the one who asked uncomfortable questions.

In May 1863, while helping Catherine organize papers in the study, Eleanor discovered one of the coded journals that Catherine had carelessly left unlocked.

Elellanena had learned to read from Catherine herself.

She was intelligent, curious, and bored with the limited reading material available in the house.

The journal’s cipher intrigued her.

She spent 3 weeks working on it in secret, the same way Richard had done 16 years earlier, slowly decoding the substitution pattern.

What she found destroyed her understanding of her entire existence.

The journal detailed her conception.

Second planting with rootstock 2.

Thomas age 21.

Excellent physical specimen.

Strong back.

Good teeth.

Weather warm and humid.

Anticipate harvest in late October 1848.

Elellanena read the entry again and again, her hands shaking.

Rootstock 2.

Thomas.

She knew Thomas.

He was one of the field hands.

quiet man in his 30s who never made eye contact with anyone.

He was her father.

Catherine was her mother.

She was not an orphan raised out of charity.

She was the product of Catherine’s deliberate breeding experiment.

The implications cascaded through Elellanena’s mind.

If this was true for her, it was true for Jonathan, for Abigail, for all the children Catherine had brought into the main house.

They were Catherine’s biological children, conceived with enslaved men, and they had been lied to their entire lives.

Worse still, the journal laid out Catherine’s plans for their futures.

Eleanor read the notations about pairings, about anticipated offspring, about the creation of a self-sustaining workforce.

She saw her own name in one of the charts connected by a line to someone called Marcus Isaac’s son to be born 1862.

Pairing with Eleanor anticipated 1865.

Eleanor felt physically sick.

Catherine intended to pair her with a boy who hadn’t even been born yet to force her to have children who would be enslaved on this plantation forever to turn her into another breeding tool in this nightmare system.

She confronted Catherine that night, her voice shaking with rage and horror.

I read your journal.

I know what you are.

I know what I am.

Catherine’s face went still, her eyes cold as winter.

You should not have done that, Elellanor.

You’re my mother.

Thomas is my father, and you’ve been planning to to breed us like animals.

Eleanor could barely force the words out.

Sit down, Catherine commanded.

No, sit down.

The threat in Catherine’s voice was unmistakable.

Elellanena sat, her whole body trembling.

Catherine paced the room, her mind clearly working through the problem Elellanena now represented.

Finally, she spoke.

You are intelligent enough to understand the position we’re in.

So, I’ll speak plainly.

Yes, I am your biological mother.

Yes, I have been implementing a systematic program to create a self- sustaining workforce for this estate.

And yes, you and the others will participate in that program when you come of age.

I won’t, Elellanena said, but her voice lacked conviction.

You will, because the alternative is far worse.

Catherine leaned forward, her face inches from Elellanena’s.

Right now, you live in this house.

You eat good food.

You wear decent clothes.

You can read and write.

What do you think happens if you refuse to cooperate? I sell you.

I sell you to a plantation in Alabama or Mississippi where they work field hands to death in 5 years.

Where women are brutalized as a matter of course.

Where literacy earns you a whipping or worse.

Is that what you want? Eleanor said nothing.

Tears streaming down her face.

I thought not.

Catherine straightened.

You will not speak of this to your brothers or sisters.

You will not speak of it to anyone in the quarters.

You will continue your life exactly as before.

And when the time comes for you to fulfill your role in this family’s future, you will do so.

Do you understand? Yes, Elellanena whispered.

But Catherine had made a critical error.

She had revealed the truth without adequately controlling the information.

Elellanena did speak to others, not immediately, but gradually, carefully.

She told Jonathan first, showing him the journal entries she had memorized.

Jonathan’s reaction was different from Elellanena’s.

He had been so thoroughly conditioned by Catherine, so completely isolated from any alternative framework for understanding the world that he struggled to see what was wrong with Catherine’s plan.

She gave us a better life, Jonathan said, confused by Eleanor’s anger.

We could have been working in the fields.

Instead, we’re here.

We’re property, Jonathan.

We’re slaves.

Our own mother enslaved us.

She’s protecting us.

She’s keeping us together.

If we were sold, we’d be separated, sent to different places.

This way, we stay together.

We stay at Thornhill.

Elellanena realized with horror that Jonathan had been too successfully indoctrinated.

He couldn’t see the cage Catherine had built around all of them.

But Abigail, 13 years old and sharp as glass, understood immediately when Elellanena told her.

And Margaret, at 12, understood, too.

The younger children were still too young to fully grasp it.

But the older ones, they knew now.

They knew what they were and what Catherine intended for them.

The knowledge changed the atmosphere in the main house.

Catherine felt it.

That shift in the air, the way her children looked at her now.

There was fear, yes, but also something else.

Calculation, waiting.

They were biting their time, and Catherine knew it.

She considered her options.

She could sell the older children, eliminate the problem, but that would waste years of investment and planning.

She could punish them severely enough to break their spirits, but physical brutality might damage them in ways that would interfere with the breeding program.

She needed them healthy, capable of bearing children.

So, Catherine chose a different approach.

She would demonstrate the consequences of disobedience through someone else.

In August 1863, a young woman named Grace tried to run away from Thornhill Estate.

She was 17, pregnant, and desperate.

She had been paired with one of the field hands against her will, and she couldn’t bear the thought of bringing a child into this system.

She ran at night, heading east toward the Savannah River, hoping to somehow cross into South Carolina, and from there make her way to Union Lines.

She was caught within 12 hours.

The dogs tracked her to a creek 3 mi from the plantation.

She was brought back, locked in one of the outbuildings.

And the next morning, Catherine assembled everyone, all the enslaved people, including her special children from the main house in the yard between the quarters and the mansion.

Grace was brought out, her hands tied.

Catherine stood on the porch of the main house, her face expressionless.

This woman attempted to abandon her responsibilities to this estate and to all of you.

She attempted to destroy the family we have built here.

The penalty for such betrayal must be severe.

What followed was brutal.

Grace was whipped publicly.

20 lashes administered by the elderly overseer Kendrick, who carried out the punishment with grim reluctance.

Catherine made all the children watch, including her own biological offspring.

The message was clear.

This is what happens to those who try to leave.

But Catherine had miscalculated again.

The public punishment didn’t terrify the enslaved population into submission.

Instead, it clarified something for them.

Catherine was willing to use extreme violence to maintain her control, which meant she was afraid.

And if she was afraid, that meant they had more power than they’d realized.

Whispers began circulating through the quarters in the weeks that followed.

Whispers about waiting for the right moment.

Whispers about what would happen when the war ended because surely it would end and surely the Yankees would come south and surely things would change.

All they had to do was survive until then.

Elellanena heard these whispers.

She began spending time near the quarters when Catherine wasn’t watching, developing relationships with the other enslaved people she had been kept separate from her entire life.

She learned things Catherine had never told her, about her father Thomas, about the other men Catherine had used, about the women who had died or been broken by Catherine’s program.

One evening in October, Elellanena met with a group of the older enslaved women in the woods beyond the quarters.

They sat in a circle in the darkness, speaking in low voices.

A woman named Hope, in her 40s, looked at Elellanena with something between pity and respect.

your mama.

She thinks she made something special here, Hope said quietly.

Think she made family.

But all she did was make people who hate her in ways she can’t even understand.

What happens when the war ends? Eleanor asked.

Depends on who wins.

Hope replied.

Yankees win.

We’re free.

Confederates win.

Things stay the same or get worse.

But either way, your mama can’t keep doing what she’d been doing.

Too many people know.

Too many people angry.

Something got to break.

“What if we made it break?” Elellanar asked.

The women looked at her in surprise.

Hope leaned forward.

“What you saying, child? What if we didn’t wait for the war to end? What if we ended this ourselves?” The idea hung in the air, dangerous and intoxicating.

One of the younger women, Anna, spoke up.

“You talking about running, taking everyone and running, or fighting?” Eleanor said.

There’s only Mrs.

Catherine and old Mr.

Kendrick.

There are 40 of us and 20 of them are children.

Hope said practically.

And where are we going to go? Confederates catch runaways.

They kill us or sell us further south.

And you? You think they’re going to see you as one of us or one of them? The question stung because Elellaner didn’t know the answer.

She was Catherine’s daughter.

She had grown up in the main house.

She could read and write.

Her skin was lighter than most of the people in the quarters.

Would they even accept her if things came to violence? Before Elellanena could respond, they heard footsteps crashing through the underbrush.

Everyone scattered, melting into the darkness.

Elellanena ran back toward the main house, her heart pounding, wondering if someone had heard their conversation, if Catherine would find out if everything was about to collapse.

But no punishment came.

The next day passed normally and the day after that it seemed they had escaped detection.

But the seed had been planted.

The idea that they didn’t have to passively wait for external forces to free them.

They could act themselves.

That idea began spreading through the quarters like a fever.

Catherine sensed the change but couldn’t identify its source.

She increased her surveillance had Kendrick patrol the quarters at night, restricted movement even further.

The tension at Thornhill Estate grew thicker with each passing week.

It was like watching a storm build on the horizon.

Dark clouds massing, electricity charging the air, everyone waiting for the lightning to strike.

The break came in March of 1864, but not in the way anyone expected.

A unit of Confederate cavalry came through Burke County, requisitioning supplies from plantations, food, horses, cloth, anything useful for the war effort.

Catherine had no choice but to comply.

She provided corn, preserved meat, and two of the plantation’s best horses.

The soldiers stayed only one night, camped in the fields beyond the quarters, and departed at dawn.

But their presence had consequences.

The soldiers spoke openly about the war’s progress, and the news was bad for the Confederacy.

Sherman was pushing through Georgia.

Union forces were closing in from multiple directions.

Some soldiers spoke fatalistically about the war being lost, about going home, about the impossibility of maintaining the fight much longer.

The enslaved population at Thornhill Estate heard every word.

Hope surged through the quarters.

Freedom was coming.

It might be months or weeks, but it was coming.

All they had to do was hold on a little longer.

Except Catherine, sensing this hope and terrified by what it meant for her long-term plans, decided to act decisively.

If the Confederacy fell, if the enslaved population was freed, everything she had built would collapse.

Her special children would leave.

Her breeding program would end.

16 years of work would be for nothing.

She couldn’t allow that to happen.

On the night of March 17th, 1864, Catherine gathered her biological children in the main house.

Jonathan, Elellanena, Abigail, Margaret, Samuel, William, Henry, Caroline, and the three youngest who were still infants.

11 children in total, ranging from 16 years old down to 6 months.

Things are going to change very soon, Catherine told them, her voice calm, but her eyes intense.

The war may end badly for us.

The Yankees may come.

There may be attempts to take you away from me, to destroy our family.

I cannot allow that to happen.

Elellanena felt ice slide down her spine.

“What are you planning?” “We’re going to secure our future,” Catherine said.

tonight.

She led them to the heritage room in the east wing, the room none of them except Jonathan had ever been allowed to enter.

Catherine lit the oil lamps illuminating the shelves of journals, the vials of hair samples, the elaborate family trees drawn on paper and pinned to the walls.

“This is our legacy,” Catherine said.

“This is what we’ve built together, and no one is going to take it from us.

” From a locked cabinet, Catherine withdrew a small wooden box.

Inside were several glass bottles containing clear liquid.

“This is a medicine called Lordinum,” she explained.

“In small doses, it provides relief from pain.

In larger doses, it provides eternal peace.

” Abigail gasped.

“You want to poison us? I want to protect you,” Catherine corrected, her voice taking on an edge of desperation.

If the Yankees come, if they free the others, where will you go? You’re not white enough to live in white society.

You’re not fully black in their eyes either.

You’ll be outcasts, owned by no one, belonging nowhere.

Is that better than staying here, staying together, staying with me.

Yes, Eleanor said firmly.

Anything is better than this.

Catherine’s face hardened.

You’re too young to understand.

All of you are too young.

but I am your mother and I know what’s best for this family.

” She moved toward the bottles, but Jonathan stepped between her and the others.

He was 16, nearly as tall as Catherine, and something in his face had changed.

“No,” he said quietly.

“Jonathan, don’t be foolish.

You understand the plan.

You’ve always understood.

I understood what you told me,” Jonathan said.

But Eleanor showed me the journals.

I read what you wrote about us, about Father Isaac, about Father Thomas, about all of them.

I know what you did.

I know what you are.

I am your mother.

You’re a monster, Jonathan said, and his voice broke on the word.

Catherine slapped him, a sharp crack that echoed in the small room.

“How dare you? After everything I’ve given you, after everything I’ve sacrificed, you sacrificed nothing.

Elellanena said, stepping forward to stand beside Jonathan.

You used people.

You destroyed them.

You destroyed us.

Catherine looked at her children, seeing them clearly, perhaps for the first time.

They were united against her.

Even the younger ones who didn’t fully understand what was happening sensed the confrontation and stood with their older siblings.

She had lost them.

In that moment, Catherine made a final desperate decision.

If she couldn’t keep her children, if they were going to reject her and leave her and destroy everything she had built, then she would at least preserve the record of what she had accomplished.

future generations would know what Katherine Thornnehill had created, even if the creation itself had failed.

She grabbed the journals, the charts, the vials of hair samples, clutching them to her chest.

“You think you can escape me? You think you can pretend none of this happened? These records will survive.

They’ll prove what I built here.

They’ll prove I was right.

” She pushed past her children and ran from the room, carrying the physical evidence of her crimes.

Jonathan and Elellanor chased after her, but Catherine was faster, driven by manic energy.

She ran through the main house out the front door across the yard toward the quarters.

What happened next depended on who you asked.

Multiple testimonies would later conflict, each person remembering the events slightly differently, shaped by their own trauma and perspective.

What is certain is that Catherine reached the quarters carrying her journals and specimens.

What is certain is that the enslaved population, roused by the commotion, emerged from their cabins to see the mistress who had tormented them for 16 years running toward them in the darkness, clutching the evidence of her atrocities.

What is certain is that someone, maybe hope, maybe one of the men, maybe several people at once, decided that this was the moment.

This was when it ended.

Katherine Thornnehill disappeared that night.

Her journals were found scattered in the mud outside the quarters.

Pages torn and muddy.

The vials of hair samples were smashed.

The charts were burned.

And Catherine herself was simply gone.

Jonathan and Eleanor reaching the quarters minutes after their mother found chaos.

People shouting, running in different directions, the acrid smell of smoke where someone had lit a fire to burn Catherine’s papers.

But no, Catherine.

Where is she? Jonathan demanded.

Hope looked at him with an expression he couldn’t read.

Gone? That’s all you need to know.

She’s gone and she ain’t coming back.

What did you do to her? What she had coming? Hope said simply.

Now you got a choice, boy.

You can raise hell about your mama, or you can understand that justice got done here tonight and let it rest.

Jonathan looked at Eleanor.

His sister’s face was pale, her eyes wide, but she nodded slowly.

“Let it rest,” she whispered.

The next morning, Catherine Thornnehill was reported missing.

Old Mr.

Kendrick, the overseer, searched the property, but found nothing.

He reported the disappearance to the sheriff in Wsboro, who came out to investigate, but ultimately concluded that Mrs.

Thornnehill had likely fled the area in fear of advancing Union forces.

a reasonable assumption given the deteriorating military situation.

No one from the quarters spoke of what had happened.

Jonathan and Ellaner and the other children said nothing.

The official record simply states that Katherine Thornnehill disappeared on the night of March 17th, 1864 and was never seen again.

But everyone at Thornnehill Estate knew the truth, even if they never spoke it aloud.

Catherine had been killed that night.

Her body had been disposed of somewhere on the plantation’s 1700 acres, and her children, her biological offspring, her breeding experiments, her legacy, had chosen to let her murderers go unpunished because they understood that their mother had earned her fate.

The war ended 14 months later.

General Sherman’s army swept through Georgia in late 1864, though they passed 30 mi north of Burke County and never came directly to Thornhill Estate.

The Confederacy collapsed in April 1865.

Freedom came to the enslaved population of Georgia through a combination of military occupation, the 13th Amendment, and the simple fact that the system of bondage could no longer be maintained.

At Thornhill Estate, the transition was complicated.

Jonathan, as Catherine’s eldest child, had some legal claim to the property, but his status was ambiguous.

Legally enslaved under Georgia law, but also Catherine’s biological heir.

Lawyer Talbot in Wsboro tried to sort out the mess, but eventually gave up.

The property fell into a kind of legal limbo.

Most of the formerly enslaved population left Thornhill Estate within weeks of emancipation.

They scattered across Georgia and beyond, seeking family members who had been sold away years before, looking for opportunities in cities or simply putting as much distance as possible between themselves and the sight of their suffering.

Some stayed, at least initially.

Hope remained, helping to organize those who had nowhere else to go.

Thomas stayed, Eleanor’s biological father, who finally, after 16 years, was able to acknowledge his daughter openly.

They had one conversation about Catherine, about what had been done to him and to Eleanor, and then they never spoke of it again.

The pain was too deep, too tangled with the fundamental wrongness of the entire situation.

Elellanena herself stayed at Thornhill Estate until 1867.

She learned in those years after the war how to exist as a free person, though the psychological damage of her childhood never fully healed.

She eventually moved to Savannah where she worked as a seamstress and married a carpenter named William Foster.

She never had children.

She never spoke publicly about her mother or her childhood.

When she died in 1903, her obituary made no mention of Thornhill Estate or Burke County.

Jonathan stayed at the plantation longer, trying to work the land with a small group of freed men who remained.

But the cotton market was depressed, the soil was exhausted, and the property’s reputation had begun to spread through the black community in Burke County.

By 1869, Jonathan gave up and abandoned the estate.

He drifted west, eventually settling in Texas under an assumed name.

He died in 1891, and his few possessions included a small notebook where he had written over and over in tiny script.

I did not choose this.

I did not choose this.

I did not choose this.

Thornhill estate itself decayed rapidly.

The main house was partially burned in a suspicious fire in 1871.

The remaining structures fell into ruin.

The land was eventually seized for unpaid taxes and sold at auction in 1878 to a timber company that cleared the old growth trees and divided the property into parcels.

But in 1871, something was discovered that brought the entire story back to public attention, at least briefly.

A well driller working on a neighboring property accidentally broke through into an old system on what had been Thornhill land.

Inside the system, 30 ft below ground, was a skeleton.

The remains were mostly intact, preserved by the cool, dry conditions.

They belonged to a woman, probably in her 30s or 40s.

Scraps of cloth suggested a dress from the 1860s.

A corroded metal locket found near the skeleton contained two miniature portraits, a man and a young boy.

The coroner in Wsboro examined the remains and concluded the woman had died from blunt force trauma to the skull.

The skeleton was buried in an unmarked grave in the county cemetery.

The official record identified the remains only as unknown female discovered former Thornhill property, 1871.

But people in Burke County’s black community knew who it was.

The story had been passed down in whispers in kitchens and churches, encoded language that protected those who had been present that night in March 1864.

They knew Catherine Thornnehill had been killed by the people she had enslaved and brutalized.

They knew her body had been hidden in a deep well or system.

They knew justice of a kind, had been done.

Over the years, more information emerged, though always fragmentarily, always incompletely.

In 1889, a man on his deathbed in Alabama confessed to a minister that he had helped murder his former mistress in Georgia during the war.

He provided no name, no details, but the minister noted the confession in his records.

In 1902, a woman in Savannah, Hope’s granddaughter, wrote a short memoir that mentioned the night the devil mistress disappeared and nobody mourned her.

The most damning evidence came to light in 1923 when a historian researching Burke County’s Civil War history discovered a cache of letters in the courthouse basement.

Among them was a letter written in 1865 by Union Captain Samuel Reynolds, who had commanded one of the first federal units to enter Burke County after the war ended.

Reynolds wrote, “We discovered disturbing evidence at a property called Thornhill Estate, indications of systematic breeding experiments conducted by the late owner upon enslaved persons, including her own biological offspring.

The details are too grotesque to relate in full, but multiple witnesses confirmed that the woman, one Katherine Thornnehill, had implemented a program to create a self-perpetuating enslaved population through forced reproduction across generations.

The witnesses also informed us that Mrs.

Thornnehill disappeared in March 1864, and though they would not explicitly state what occurred, their meaning was clear enough.

I have elected not to pursue the matter further, as it seems to me that whatever justice was enacted upon this woman was welld deserved.

I have directed my men to say nothing of what we learned here.

The letter was filed away and forgotten again until a graduate student found it in 1954 while researching her dissertation on reconstruction in Georgia.

She tried to verify the story, interviewing elderly residents of Burke County who might remember family stories from that era.

Most claimed to know nothing.

One woman, 93 years old, the great granddaughter of one of the enslaved people at Thornhill Estate, said only, “Some things happened that needed to happen.

Some people did things that needed doing, and that’s all that needs to be said about it.

” The final mystery of Thornhill Estate concerns the 23 children found locked in the basement when federal troops arrived.

Captain Reynolds official report mentions them, as do several letters written by soldiers in his unit.

The children were freed and placed with freed men families in Burke County and surrounding areas.

But what happened to them after that is lost to history.

Some of them surely survived to adulthood.

Some likely had children of their own, which means there are probably people alive today living in Georgia or elsewhere who carry Katherine Thornnehill’s genetic legacy without knowing it.

They might be descended from Jonathan or Eleanor or one of the other children from the breeding program.

They might carry some of those distinctive features, pale green eyes, orin hair, sharp cheekbones that marked Catherine’s offspring.

They would never know their ancestor built her legacy on one of the most calculated systems of exploitation and cruelty in American history.

They would never know they exist because a woman decided to treat human beings as livestock, to build a dynasty on forced reproduction and genetic control.

They would never know that their great great great grandmother’s body lies in an unmarked grave in Burke County, placed there by the people she had tormented, people whose names we will never know because they protected each other’s secrets even in freedom.

The site of Thornhill estate today is just fields and forest.

The county maintains no historical marker.

No books about Burke County history mention the plantation in any detail.

The house’s foundation is still visible if you know where to look.

Buried under decades of leaf fall and undergrowth.

The old well where Catherine’s body was hidden has long since collapsed and filled with earth.

But the story persists, passed down through oral tradition in Burke County’s black community, whispered in genealogy circles, referenced obliquely in academic papers about slavery and eugenics.

It persists because it represents something true and terrible about American history.

Not just the brutality of slavery itself, but the ways human beings will rationalize and systematize cruelty when they hold absolute power over others.

Katherine Thornnehill convinced herself she was building something revolutionary, creating a new model for plantation management, securing her family’s future.

In reality, she was perpetuating and intensifying one of humanity’s greatest evils.

And the people she exploited, the people she bred and controlled and tormented, ultimately erased her from history as thoroughly as she had tried to erase their humanity.

What do you think of this story? Do you believe everything was revealed, or are there still secrets buried on that land in Burke County? The truth is, we may never know the full extent of what happened at Thornhill Estate.

The people who lived through it, the survivors, chose to carry some secrets to their graves.

And maybe that’s their right.

Maybe some stories belong to the people who endured them, not to historians or storytellers like me.

But we can honor those people by remembering that their resistance mattered, that their survival mattered, that they outlasted the system designed to destroy them.

If this story moved you, if it made you think about the hidden histories in your own community, let me know in the comments below.

Share this video with someone who appreciates deep dives into America’s darkest chapters.

Subscribe to this channel for more stories that challenge what you think you know about history.

And remember, the past is never as far behind us as we’d like to believe.

See you in the next video.

News

Ilhan Omar ‘PLANS TO FLEE’…. as FBI Questions $30 MILLION NET WORTH

So, while Bavino is cracking down in Minnesota, House Republicans turning the heat up on Ilhan Omar. They want to…

FBI & ICE Raid Walz & Mayor’s Properties In Minnesota LINKED To Somali Fentanyl Network

IC and the FBI move on Minnesota, touching the offices of Governor Tim Walls and the state’s biggest mayors as…

FBI RAIDS Massive LA Taxi Empire – You Won’t Believe What They Found Inside!

On a Tuesday morning, the dispatch radios in hundreds of Los Angeles taxi cabs suddenly stopped playing route assignments. Instead,…

Brandon Frugal Finally Revealed What Forced Production to Halt in Season 7 of Skinwalker Ranch….

The Secret of Skinwalker Ranch became History Channel’s biggest hit. Six successful seasons documenting the unknown with real science and…

1 MINUTE AGO: What FBI Found In Hulk Hogan’s Mansion Will Leave You Shocked….

The FBI didn’t plan to walk into a media firestorm, but the moment agents stepped into Hulk Hogan’s Clearwater mansion,…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage… It started like any other evening…

End of content

No more pages to load