The Plantation Master Bought a Young Slave for 19 Cents… Then Discovered Her Hidden Connection

November 7th, 1849, Chattam County, Georgia.

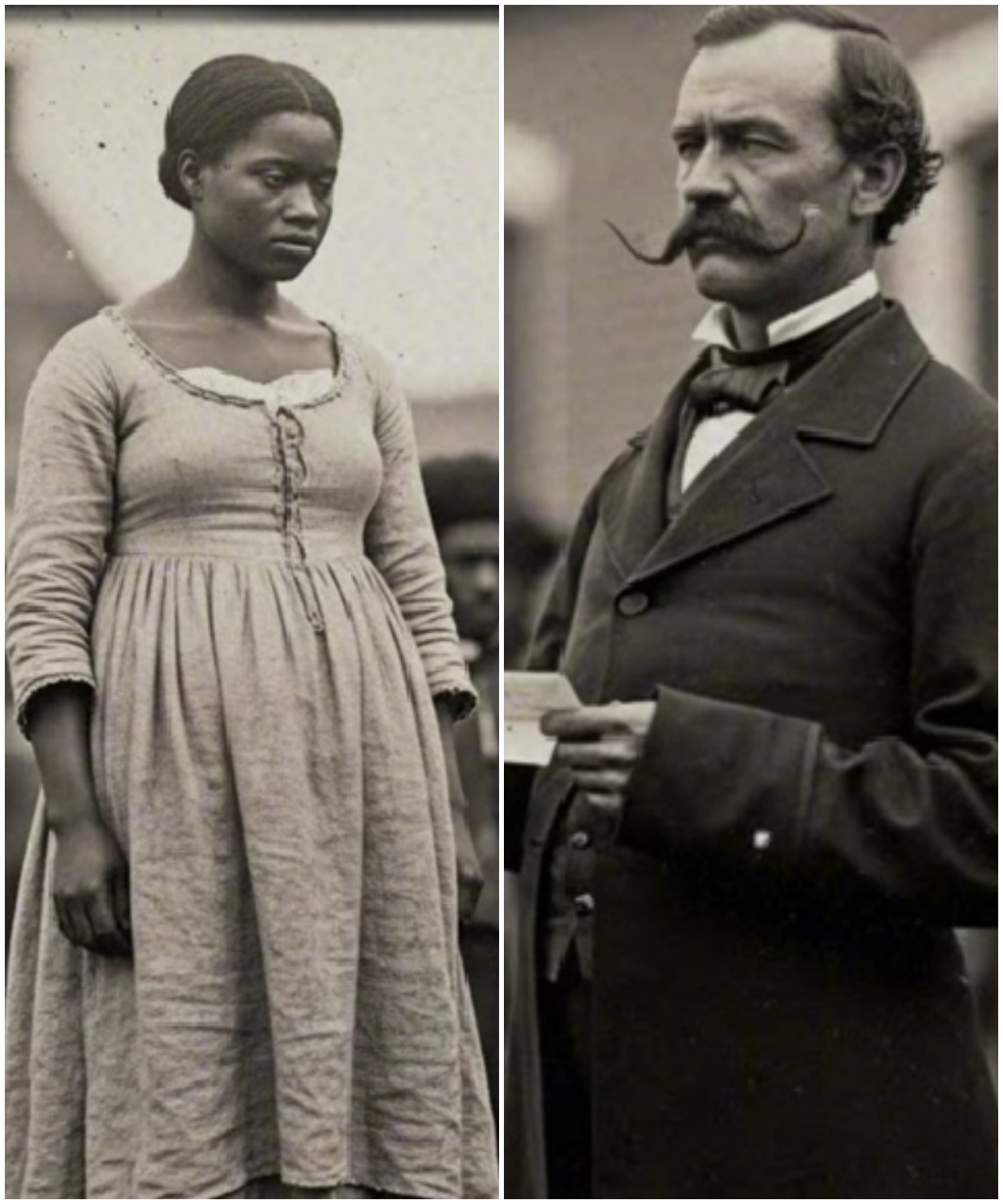

A woman stands on an auction platform in the center of Savannah’s public market.

Her hands bound with rope that has already worn the skin of her wrists roar.

She is 22 years old, 5 months pregnant, and she is about to be sold for 19, not $19.

1 19 less than the cost of a pound of coffee.

The auctioneer, a man named Cyrus Feldman, holds the deed of sale in his hands, and his voice carries across the crowd with practice deficiency.

But something is wrong with this auction, something that makes even the hardened slave traders in the crowd shift uncomfortably, something that will set in motion a chain of events so disturbing that the city of Savannah will spend the next 80 years trying to erase every record of what happened that day.

Tonight we reveal the truth they buried and we will follow this woman’s story to its shocking conclusion.

A conclusion that involves murder, betrayal, and an act of resistance so brutal that when it was finally discovered in 1931, the authorities immediately sealed the evidence and forbade anyone from speaking about it publicly.

This is the story they never wanted you to hear.

Let’s build a community that refuses to let these truths disappear.

Now, let’s continue.

The woman standing on that platform has a name, though it appears in official records only twice, and both times it is spelled differently.

In the bill of sale from her previous owner, she is listed as Diner.

In the coroner’s report filed 6 years later, she is called Diana.

For our purposes, we will call her Dinina because that is the name she used when she finally spoke.

When she finally told her story to the one person who listened.

Dinina was born in 1827 on a rice plantation outside Charleston, South Carolina.

She never knew her father.

Her mother, a woman named Patience, worked in the fields from sunrise until long after dark, her hands permanently stained green from rice stalks, her back bent from years of labor that would eventually kill her when Dinina was just 11 years old.

After patients died, Dinina was sold to a tobacco merchant in Charleston, a man named Elias Cartwright, who needed domestic help for his growing household.

Elias was 43 years old, married to a woman named Constance, and father to four children ranging in age from 6 to 15.

He was also a deacon at the First Presbyterian Church, a member of the Charleston Chamber of Commerce, and by all public accounts, a respectable businessman who treated his property, human and otherwise, with appropriate Christian values.

That was the public account.

The private reality was something else entirely.

Dinina worked in the Cartwrite household for 3 years from age 11 to 14.

She cleaned, she cooked, she cared for the younger children, she did everything that was demanded of her.

And Elias Cartwright watched her.

He watched her in that particular way that enslaved women learned to recognize that predatory attention that signaled danger, that made survival require constant vigilance.

When Dinina turned 14, Elias’s attention became something more than watching.

It became action.

What happened between them, if we can even use that word between, as though there was any equality or choice involved.

What happened was rape.

Systematic, repeated, sustained over years.

Diner had no power to refuse.

Enslaved women had no legal right to deny their owners anything.

The law did not recognize their bodily autonomy.

The law considered them property and property cannot be violated because property has no self to violate.

Constance Cartwright knew.

She knew because enslaved women who worked in close quarters could not hide pregnancy.

She knew because Dinina’s body changed in ways that made the truth unavoidable.

But Constance did not confront her husband.

She confronted Dinina.

She accused Dina of seduction, of tempting a good Christian man, of deliberately destroying the sanctity of a godly household.

The blame in Constance’s worldview lay entirely with the 16-year-old girl who had no power to say no rather than with the 46-year-old man who had absolute power to take whatever he wanted.

In March of 1843, Dinina gave birth to a daughter.

The child was noticeably light-skinned, her features clearly indicating mixed parentage.

Elias Cartwright refused to acknowledge the child as his.

He named her Ruth, had her registered in his property ledger as the offspring of his servant Diner, father unknown, and continued his life exactly as before.

Constance demanded that Diner and the baby be removed from the main house.

They were relocated to the servants’s quarters, a cramped structure behind the main residence where six other enslaved people lived in conditions that barely qualified as shelter.

Dinina raised Ruth while continuing to work in the Cartrite household.

She nursed her daughter at night after 16-hour days of labor.

She sang to her in whispers songs her own mother had sung, songs that carried memories of Africa, [clears throat] of freedom, of a world before chains.

And she watched as Ruth grew, as the child’s features became increasingly undeniable evidence of who her father was, as the resemblance to Elias Cartwright became so obvious that neighbors began to whisper, to speculate.

To understand what everyone had always known, but politely ignored.

In 1847, when Ruth was 4 years old, Elias Cartrite sold her.

He sold her to a slave trader named Marcus Pennington for $400, a standard price for a healthy child of that age.

He sold her on a Tuesday morning without warning Diner, without allowing goodbyes, without permitting the mother even a final moment with her daughter.

Dinina was working in the kitchen when she heard Ruth screaming from the front of the house.

By the time she ran outside, the child was already gone, loaded into a wagon that was disappearing down the street, her small hands reaching back toward the only home she had ever known.

Dinina collapsed in the street.

The other enslaved people in the household had to carry her inside.

For 3 days she did not speak, did not eat, barely moved.

She had entered a state of grief so profound that it resembled death itself, and perhaps she wished it was, but she did not die.

Her body refused her that mercy.

Instead, she survived, and survival meant returning to work, meant continuing to serve the man who had raped her, and then sold the child born of that rape meant functioning in a world designed to destroy her humanity piece by piece.

Two years later, in the summer of 1,849, Dinina became pregnant again.

The father was Elias Cartrite.

There was no question about this, no ambiguity.

Constance Cartwright’s fury was immediate and absolute.

She could tolerate one incident, one child, one public embarrassment.

But a second pregnancy made the situation undeniable, made it impossible to maintain the fiction that Dinina was a seductress and Elias, an innocent victim of temptation.

A second pregnancy revealed the truth that Elias Cartwright was a man who repeatedly raped an enslaved woman he owned, who had been doing so for years, who showed no intention of stopping.

Constance gave Elias an ultimatum.

Get rid of her.

I will not have that woman in my house bearing your children while I live under the same roof.

Sell her, trade her, give her away.

I do not care, but she leaves this household within the month, or I will make this situation public in ways that will destroy your reputation permanently.

” Elias understood the threat.

His position in Charleston society depended on maintaining respectability.

Wealthy men were expected to be discreet about their violations of enslaved women, whispered about perhaps, but never openly acknowledged.

A wife publicly accusing her husband of serial rape of his property that would cross a line that even Charleston’s tolerant attitude towards slavery could not ignore.

So Elias made arrangements.

He contacted a business associate in Savannah, a merchant named William Hadley, who owed him money from a failed cotton investment.

Elias proposed a transaction.

He would forgive Hadley’s debt, approximately $800, in exchange for Hadley purchasing Diner and taking her to Savannah.

Far enough from Charleston that she would never return.

Far enough that Constance would never have to see her again.

Far enough that Elias could pretend she had never existed.

Hadley agreed.

The transaction was arranged for early November during Savannah’s regular public auction, where such sales occurred with administrative efficiency.

But Elias added one specific condition to the sale, a condition so cruel that it reveals the depth of his vindictiveness.

He set Diner’s minimum price at 19.

The amount was deliberate, calculated to humiliate.

In 1849, the average price for an enslaved woman of childbearing age ranged from $700 to $900.

A pregnant woman carrying a child who would eventually become additional property should have been valued even higher.

By setting the price at 19 cents, Elias achieved several goals simultaneously.

He demonstrated that Dinina had no value to him whatsoever.

He ensured that she would be purchased by someone who recognized she was being offered as damaged goods, someone who would treat her accordingly.

And most importantly, he guaranteed that Dinina would understand exactly how worthless he considered her, how utterly disposable she was in his eyes.

William Hadley traveled to Charleston in early November to finalize the arrangement.

He met with Elias in the man’s study, reviewed the paperwork, signed the necessary documents.

The bill of sale was meticulously prepared, listing Diner’s approximate age, her condition, pregnant, approximately 5 months, and the agreed upon price, 19.

Elias Cartwright signed his name with the same pen he used to sign church documents and business contracts.

His signature was neat, legible, totally unremarkable, just another transaction in a life built on transactions.

Dinina was informed of the sale the night before she was to leave Charleston.

She was given no choice, no opportunity to gather belongings because she had no belongings, no chance to say goodbye to the people she had lived alongside for years.

She was simply property being transferred from one owner to another, and property did not require emotional consideration.

The journey from Charleston to Savannah took 2 days by wagon.

Hadley hired a driver, a white man named Silas Burke, who specialized in transporting human cargo.

Diner rode in the back of the wagon, her hands bound.

A precaution against escape, though where would she run? 5 months pregnant in a region where every white person was empowered to stop and question any black person traveling without papers.

They arrived in Savannah on November 6th.

The city was larger than Charleston, busier, filled with the sounds of commerce and construction.

The port hummed with activity, ships loading and unloading goods from across the world, cotton and rice and tobacco flowing out, manufactured items and luxury goods flowing in, and human beings, thousands of human beings being bought and sold and traded like livestock.

William Hadley took dinina directly to the auction house, a large wooden structure near the waterfront where sales occurred three times weekly.

The auctioneer, Cyrus Feldman, examined Diner with the practiced eye of someone who had evaluated thousands of people for sale.

He noted her age, her condition, her general health.

Then he saw the bill of sale, saw the minimum price of 19 cents, and his expression changed.

“Something is wrong with this one,” Feldman said to Hadley.

“What is it? Disease? Injury? Mental deficiency? Nothing like that?” Hadley replied.

She is healthy, able to work.

The child appears viable.

Then why 19 cents? The seller wanted her gone quickly.

It is a personal matter, family dispute, Feldman understood immediately.

This woman had done something or had something done to her that made her previous owner want her removed from his household.

The low price was a signal, a warning to potential buyers.

This property comes with complications.

You will include that in the auction description, Feldman said.

I will not misrepresent her condition and risk my reputation.

Hadley agreed.

He did not care how Feldman presented Dinina to the crowd.

He simply wanted to complete the transaction, collect his compensation for the debt Elias had forgiven, and move on with his business.

The auction was scheduled for the following morning, November 7th, at 10:00 a.

m.

Diner spent the night in a holding cell beneath the auction house, a damp stone room where people awaiting sale were kept like animals in pens.

She did not sleep.

She sat with her back against the cold wall, her hands resting on her stomach, feeling the child move inside her.

this child who would be born into slavery, who would never know freedom, [clears throat] who would belong to William Hadley or whoever purchased them at auction, who would live and die as property unless something changed, unless the entire system collapsed.

And in November of 1849, that seemed as likely as the sky opening up and God himself descending to pass judgment on the men who built their fortunes on human suffering.

When morning came, Dinina was brought up from the holding cell and positioned near the auction platform.

She could see the crowd gathering, perhaps 60 or 70 people, some serious buyers, plantation owners, and merchants.

Others simply spectators who attended auctions as entertainment, who watched human beings sold, and found it no more morally troubling than watching cattle sold at market.

Cyrus Feldman took his position on the platform at exactly 1000 a.

m.

The November sun was already warm, and the air smelled of salt water and tobacco smoke.

Feldman began with furniture, several chairs, and a dining table from an estate sale.

Then livestock, a pair of horses, some chickens, then human beings.

He sold a young man, approximately 20 years old, for $950.

He sold an elderly woman, described as an excellent cook, for $300.

Then he called for diner.

She was brought onto the platform by Silus Burke, who positioned her in the center where everyone could see.

Feldman read from the bill of sale in a voice that carried across the crowd.

Female named diner, approximately 22 years of age, currently with child, estimated five months, experienced in domestic service, able to cook, clean, and perform household tasks.

Minimum bid 19 cents.

The crowd reacted immediately.

19 cents, someone called out.

What is wrong with her? Is she diseased? I am informed she is healthy, Feldman replied.

The price reflects a personal matter between the seller and the property, not a deficiency in the property itself.

That explanation satisfied no one.

In the economy of slavery, price indicated quality.

A woman offered for 19 cents must be fundamentally defective, diseased, or dangerous, or mentally unsound.

No rational buyer would risk investment on someone being sold at such an insultingly low price unless they knew something others did not.

Several men who had been preparing to bid immediately lost interest.

They turned away, focused their attention on the next items up for auction, but three men remained interested.

The first was William Hadley himself.

He had arranged this auction specifically to acquire diner to fulfill his agreement with Elias Cartwright.

He stood near the front of the crowd, waiting for the moment to bid.

The second man was someone Hadley had never seen before.

A tall, thin figure dressed in traveling clothes, standing near the back, his face shadowed by a widebrimmed hat.

The third man was local, a Savannah plantation owner named Thornton Graves.

Graves owned a midsized cotton plantation about 15 miles outside the city, and he was known among enslaved people as one of the crulest masters in Chattam County.

His plantation had the highest mortality rate of any comparable operation, not because of accidents or disease, but because graves worked people to death deliberately, calculating that it was more profitable to extract maximum labor over a short period than to maintain workers over decades.

Graves had been watching Diner since she appeared on the platform, and something about this situation intrigued him.

A healthy pregnant woman being sold for 19 cents.

That kind of opportunity did not present itself often.

Are you ready to hear what I write next? This is where the story gets even darker, where we discover what Thornton Graves planned to do with Diner, and where we meet the mysterious stranger who will change everything.

Cyrus Feldman raised his hand to quiet the murmuring crowd.

19 cents, he called out.

Do I have a bid of 19 cents for this property? William Hadley raised his hand immediately.

19 cents.

The crowd turned to look at him.

Hadley was known in Savannah, a respected merchant with legitimate business interests.

His willingness to bid gave Dinina a thin veneer of credibility.

If Hadley was interested, perhaps she was not as defective as the price suggested.

But before Feldman could acknowledge the bid, another voice cut through the crowd.

25 cents.

Everyone turned.

The speaker was Thornton Graves.

He stood with his arms crossed, his expression unreadable.

Hadley’s jaw tightened.

He had not anticipated competition.

50 cents, Hadley counted.

Graves smiled.

and it was not a pleasant expression.

$1.

The crowd was riveted now.

Two men bidding against each other for a woman being sold at refuge prices.

This was unusual.

This suggested something more than a simple transaction was occurring.

Hadley hesitated.

He had agreed to acquire diner for Elias Cartrite, but he had not agreed to engage in a bidding war.

The debt Elias had forgiven was $800.

If Hadley had to spend significant money to acquire diner, he would be operating at a loss.

$2, Hadley said, his voice tight.

Thornton Graves took a step forward.

He was enjoying this, enjoying the public attention, enjoying the knowledge that he was making Hadley uncomfortable.

“$5,” Graves called out.

And there was a challenge in his tone, a dare for Hadley to continue.

Hadley looked at Cyrus Feldman, then back at Graves.

He was calculating risks, weighing costs.

Finally, he shook his head and stepped back.

Graves had won.

$5 once, Feldman called out.

$5 twice.

Then the stranger in the back of the crowd spoke.

$10.

Every head turned.

The man had removed his hat now, and his face was visible, weathered, scarred along the left cheek, his eyes the color of winter sky.

He looked to be in his mid30s, and there was something about his bearing that suggested military service or perhaps time spent in occupations where violence was routine.

“Who are you?” Feldman asked.

The question was not hostile, simply procedural.

Auctioneers needed to know who was bidding, needed to verify that buyers had actual means to pay.

My name is Jacob Marsh.

I am new to Savannah.

I have business in the city and require domestic help.

Do you have $10, Mr.

Marsh? Jacob Marsh approached the platform.

He reached into his coat and withdrew a leather purse.

From it he counted out 10 silver dollars, placing them one by one on the podium where Feldman stood.

I do.

Thornton Graves was staring at Marsh with open hostility now.

He did not like being outbid.

Did not like strangers disrupting what he had assumed would be an easy acquisition.

$15, Graves said.

20,” Marsh replied without hesitation.

“30 The crowd was enthralled.

The price had escalated from 19 cents to $50 in a matter of minutes.

Whatever was happening here, it was no longer about acquiring a pregnant enslaved woman at bargain prices.

This had become a contest of will, a public demonstration of power.

Thornton Graves looked at Jacob Marsh, trying to understand who this man was, what his interest could possibly be.

Then Graves made a decision.

$100.

The crowd gasped.

$100 was a reasonable price for a healthy enslaved woman, but it was far above what anyone had expected this auction to reach.

Graves was making a statement.

He was showing that he would not be outbid, that he had resources beyond what some traveling stranger could match.

Jacob Marsh met Graves’s stare.

For a long moment, he said nothing.

Then he spoke and his voice carried across the crowd with absolute clarity.

$200.

The silence that followed was complete.

$200 exceeded the rational value of this transaction by any measure.

Even accounting for Diner’s pregnancy, even assuming the child survived and became valuable property in the future, $200 represented an investment that would take years to recoup.

Thornton Graves understood what was happening.

This was no longer about money.

This was about dominance, about refusing to yield.

And Graves had built his entire life on refusing to yield.

“$300,” Graves said.

His voice was hard now, angry.

“3 $350,” Marsh counted.

“400, 500.

The amounts climbed.

600700 800.

” When the bidding reached $1,000, William Hadley quietly left the auction house.

He had no interest in participating further, and he needed to send a message to Elias Cartwright, explaining that the simple transaction they had arranged had become something else entirely, something complicated and expensive and potentially dangerous.

At $1,200, Thornton Graves stopped bidding, not because he lacked funds, but because he suddenly understood that Jacob Marsh would continue bidding until Graves bankrupted himself.

“This stranger was not trying to acquire property.

He was trying to destroy whoever opposed him.

” “1 $1,200 once,” Feldman called out.

His voice was uncertain now.

This auction had spiraled beyond anything in his experience.

$1,200 twice.

He looked at Thornton Graves, giving the man one final opportunity to bid.

Graves shook his head, his face flushed with humiliation and rage.

Sold to Mr.

Jacob Marsh for $1,200.

The crowd erupted in conversation.

$1,200 for a woman who had been offered at 19.

The story would spread through Savannah by nightfall, would become legend, would be repeated and embellished until no one remembered the actual facts, only the mythology.

But Dinina, standing on that platform throughout this entire exchange, her hands still bound, her pregnancy visible beneath the thin dress she wore, Dinina understood something the crowd did not.

She understood that she had just been purchased by a man willing to spend a fortune to prevent her from being purchased by someone else.

And that meant Jacob Marsh either knew something about her that made her extraordinarily valuable or he knew something about Thornton Graves that made preventing Graves from acquiring her worth any price.

Either possibility terrified her.

The paperwork was completed within the hour.

Jacob Marsh paid the $1,200 in cash, counted out in gold coins that he produced from a leather bag he carried.

Cyrus Feldman prepared the deed of sale, listing Diner’s description, her approximate age, her condition.

At the bottom of the document, in the space for the buyer’s signature, Jacob Marsh wrote his name in neat, careful script.

By law, Diner was now his property.

Thornton Graves watched this transaction from across the auction house, his expression dark with fury.

When Marsh turned to leave, leading Diner toward the exit, Graves intercepted him.

Mr.

Marsh, a word.

Jacob Marsh stopped.

He did not release Diner’s arm.

When he turned to face Graves, his expression was carefully neutral.

Mr.

Graves, you have made a poor investment.

That woman is not worth half what you paid.

Perhaps.

Then why did you bid so aggressively? Because I wanted her and I have the means to pay for what I want.

Graves took a step closer.

You are new to Savannah, so perhaps you do not understand how things work here.

Certain people are accustomed to certain courtesies.

When I am bidding on property, others generally defer.

Is that so? Marsh said.

His tone was mild, but there was something beneath it, something cold.

Then perhaps you should have bid higher.

The two men stood facing each other and the tension between them was palpable, dangerous.

Finally, Graves stepped back.

Enjoy your purchase, Mr.

Marsh.

I am sure you will find her everything you hoped for.

He turned and walked away.

But Diner could see the rigidity in his shoulders, the barely contained violence in his movements.

This was not over.

Men like Thornton Graves did not accept public humiliation quietly.

Jacob Marsh led Diner out of the auction house and into the street.

The November sun was high now, and the city was busy with midday activity.

Marsh walked quickly, not roughly, but with purpose, as though he wanted to put distance between himself and the auction house as rapidly as possible.

They reached a wagon parked two blocks away, a simple farm cart with a canvas cover.

Marsh helped Dinina climb into the back, his touch impersonal but not cruel.

Then he climbed onto the driver’s bench, took up the reinss, and urged the horse forward.

They rode in silence through Savannah’s streets, past storefrs and residences, past the city market where vendors sold vegetables and fish, past the cathedral with its Spanish architecture, past the boundary where urban development gave way to forest and farmland.

Only when they were well beyond the city limits, when the road had narrowed to a dirt path surrounded by pine trees and palmetto scrub, did Jacob Marsh finally speak.

My name is Jacob Marsh.

You will call me that, or you will call me sir, whichever you prefer.

I am not going to hurt you.

I am not going to sell you, and I am not going to force myself on you.

Do you understand? Dina said nothing.

She had heard promises before, had learned that men said many things to gain compliance, that words meant nothing without actions to support them.

Marsh continued, “I know you do not trust me.

I would not trust me either if I were in your position, but I need you to listen carefully because your life and the life of your child depends on what happens over the next few days.

” He paused, navigating the wagon around a fallen branch.

Ilas Cartrite sent you here to die.

Not immediately, not obviously, but he arranged circumstances to ensure that you would end up with someone who would work you to death or worse.

The 19 cent minimum price was designed to attract exactly one type of buyer.

Men like Thornton Graves, men who purchase damaged property because they know they can extract value through cruelty before the property is used up completely.

Diner’s blood ran cold.

How do you know about Elias? I know a great deal about Elias Cartrite.

Marsh said, “I know he raped you repeatedly over a period of years.

I know he fathered at least one child with you, a daughter named Ruth.

I know he sold that child to erase evidence of his crimes.

And I know he sent you here to ensure you would never return to Charleston to cause him embarrassment.

Dinina felt tears burning behind her eyes, but she refused to let them fall.

Crying was weakness, and she could not afford weakness.

Who are you? A friend, Marsh said.

Or at least a friend of people who were your friends.

He reached into his coat and withdrew a folded piece of paper.

Without taking his eyes from the road, he handed it back to Dinina.

Read it.

Diner unfolded the paper with trembling hands.

The handwriting was unfamiliar, but the words made her breath catch.

Dinina, if you are reading this, you have been purchased by Jacob Marsh, and that means the first part of our plan succeeded.

Jacob works with people who help enslaved people reach freedom.

He has been preparing for your arrival in Savannah for 3 months.

Trust him.

Do what he says.

He is risking his life to help you.

The letter was unsigned, but at the bottom, carefully drawn, was a small symbol, a bird in flight, wings spread wide.

Diner recognized it immediately.

It was the mark her mother had taught her.

The mark women in their family had used for generations to identify themselves to each other to say, “I am here.

I am with you.

I have not forgotten.

” “Where did you get this?” Dinina whispered.

“From a woman in Charleston named Bethy.

She is elderly.

Works as a cook in Elias Cartwright’s household.

She has been watching you for years, watching what Elias did to you, what Constants allowed to happen.

” When she learned you were being sent to Savannah, she contacted people she knew, people who operate what we call the Underground Railroad.

Those people contacted me.

Diner’s mind reeled.

Bethy.

Bethy had been part of the Cartrite household for decades, so old and seemingly harmless that white people stopped seeing her as a person at all, simply as furniture that occasionally moved and performed tasks.

But Bethy had been watching, had been connected to networks Diner had never suspected existed, had arranged this rescue.

The Underground Railroad, Dinina said slowly.

I have heard stories.

Stories are true.

Marsh confirmed.

There are people, black and white, who help enslaved people escape to free states, to Canada, to places where the law does not recognize property rights in human beings.

It is dangerous, illegal and it requires careful planning.

But it is possible.

You are saying you are going to help me escape.

I am saying I am going to try.

Whether we succeed depends on many factors, most of which are outside my control.

The most immediate danger is Thornton Graves.

What about him? Marsh’s hands tightened on the res.

Graves is not just a cruel plantation owner.

He is also a slave catcher.

He makes additional income hunting fugitives, returning them to their owners for reward money.

He has connections throughout Georgia and South Carolina.

Men who owe him favors.

Men who will help him if he asks.

And I just humiliated him publicly.

Spent $1,200 to prevent him from acquiring you.

He will want to know why.

He will investigate.

And if he discovers that I am involved with the Underground Railroad, he will come after both of us.

Then we need to leave.

Dinina said we need to go now tonight as far and as fast as possible.

We cannot, Marsh said.

Not yet.

Why not? Because Graves will be watching the roads out of Savannah.

He will have men at checkpoints asking questions, looking for anyone matching our descriptions.

If we run immediately, we will be caught within 2 days.

Then what do we do? We hide in plain sight.

Marsh turned the wagon onto a smaller path, barely visible through the underbrush.

We go to a place Graves would never think to look, and we wait until he stops watching so carefully.

Then we move.

Where is this place? You will see.

They traveled deeper into the forest, following paths that seemed to exist more as animal trails than as roads meant for wagons.

The afternoon light filtered through the canopy in dusty shafts, and the air smelled of decaying vegetation and standing water.

Finally, after nearly an hour of slow progress, they emerged into a clearing.

In the center stood a cabin, small and weathered, its walls made of rough huneed logs, its roof covered with wooden shingles that had turned gray with age.

Smoke rose from a stone chimney, indicating someone was inside.

Marsh stopped the wagon and climbed down.

He helped Diner descend, then led her toward the cabin door.

Before he could knock, the door opened.

The woman who stood in the doorway was perhaps 50 years old, her hair wrapped in a blue cloth, her dress simple but clean, her skin was dark, her eyes sharp and assessing when she saw Dinina.

Her expression softened.

You got her.

I did.

Any trouble more than expected, Marsh said.

Thornton Graves was at the auction.

The woman’s face hardened.

Graves, that man is a demon.

Did he see you? He saw me bid against him and win.

So he knows your face, he knows I exist.

Whether he knows anything else remains to be seen.

The woman stepped aside, gesturing for them to enter.

Inside the cabin was larger than it appeared from outside.

A fire burned in the hearth, and the room smelled of cooking, something with beans and salt pork.

There was a table, several chairs, a bed in the corner.

Another woman, younger, perhaps 30, sat at the table, mending a shirt.

She looked up when Dinina entered and her eyes widened.

“Lord have mercy.

She is just a child.

” “Dinina is 22,” Marsh said.

“She is stronger than she looks.

” The older woman moved to Diner, took her hands, examined her face with the intensity of someone looking for signs of illness or injury.

“What is your name, child?” “Diner.

” I am Sarah.

This is my daughter Hannah.

You are safe here.

No one knows about this cabin except people we trust.

You will stay with us until Jacob can arrange the next part of your journey.

How long will that be? Dinina asked.

Days, possibly weeks, Marsh said.

It depends on Thornton Graves.

On how aggressively he pursues this on how quickly I can arrange safe passage north.

Dinina felt exhaustion wash over her, the accumulated weight of fear and uncertainty, and the sheer physical demands of pregnancy pressing down on her.

Sarah seemed to sense this.

She guided Dinina to the bed.

You rest now.

We will talk later.

There is food when you are ready, and you are safe.

That word again, safe.

Diner wanted to believe it.

Wanted to trust that these strangers who claimed to be helping her were genuine.

But safety was a luxury enslaved people could not afford to assume.

She lay down on the bed, and despite her fear, despite everything, sleep pulled her under within minutes.

When she woke, it was dark outside.

The fire had been rebuilt, and the cabin was warm.

Sarah and Hannah sat at the table, talking in low voices.

Jacob Marsh was gone.

“Where is he?” Dinina asked, sitting up.

He left an hour ago.

Sarah said he has arrangements to make in Savannah.

People to contact.

He will return tomorrow or the day after.

In the meantime, you are with us.

Dinina stood.

Move to the table.

Sarah pushed a bowl toward her.

Beans and cornbread and a piece of salt pork.

Eat.

You need strength for what is coming.

What is coming? Dinina asked.

The truth? Hannah said.

Her voice was quiet but firm.

The truth about who you are.

Why Elias Cartwright really sent you here and why Jacob Marsh spent $1,200 to save you.

Because it was not just about saving you, Dinina.

It was about stopping something much worse.

Dinina felt cold despite the fire’s warmth.

What are you talking about? Sarah and Hannah exchanged a glance.

Then Sarah spoke and what she said made Dina’s world tilt.

Elias Cartwright did not send you to Savannah simply to get rid of you.

He sent you here because he knew Thornton Graves would buy you.

And he knew what Graves does to pregnant women he acquires at auction.

He has a pattern, a system, and you were supposed to be his next victim.

The sealed room exists to bring you stories like this.

Stories that expose the mechanisms of historical evil.

Stories that refuse to let the past stay buried.

If you appreciate what we do here, hit that like button.

Share this video with someone who needs to hear this truth and subscribe so you never miss a story.

Now, let’s discover what Sarah and Hannah know about Thornton Graves, and why Diner’s pregnancy made her a target for something even worse than slavery itself.

Sarah stood and moved to a wooden chest in the corner of the cabin.

She opened it and withdrew a leatherbound journal, its pages yellowed with age.

She brought it to the table and placed it in front of diner.

This journal belonged to a woman named Abigail.

She died 2 years ago consumption.

But before she died, she wrote down everything she knew, everything she had witnessed about what happens on Thornton Graves’s plantation.

Sarah opened the journal to a marked page.

Read it.

Diner looked down at the careful handwriting.

The entries were dated, organized chronologically, written in the voice of someone who knew she was documenting evidence for a future that might never come.

The first entry Dina read was dated March 1,000, 845.

Today, I saw them bring in another one.

Her name is Rachel.

She is pregnant, maybe 6 months, and they bought her at auction for almost nothing because the seller said she was difficult.

Mr.

graves keeps her separate from the rest of us in the old tobacco barn at the edge of the north field.

I’m not allowed near there.

None of us are, but at night I can hear her crying.

The next entry, April 1,845.

Rachel is gone.

They say she died in childbirth, that both she and the baby died, and they buried them somewhere past the treeine, but I do not believe it.

I heard the baby crying two nights ago.

I heard it clear as anything, a newborn’s cry.

And then I heard it stop suddenly, like someone made it stop.

And Rachel, I saw her 3 days ago when they moved her from the barn to the main house.

She did not look like someone about to give birth.

She looked like someone who had already given birth, and something had gone very wrong.

Diner’s hands shook as she turned the page.

Another entry.

June 1,846.

There is a new one now.

Her name is Margaret.

Same as before.

Pregnant, bought cheap, kept separate.

Mister Graves visits the barn every night.

I do not know what he does there, but Margaret screams and no one is allowed to help her.

Mrs.

graves acts like it is not happening, like those screams are just wind or animals.

But we all hear it.

We all know.

Another entry.

August 1,846.

Margaret disappeared last week.

They say she ran away, but that makes no sense.

She was 8 months pregnant and could barely walk.

Where would she run? How would she survive? No, she did not run.

Something happened to her.

Same as Rachel.

Same as the one before Rachel whose name I never learned.

This is a pattern.

This is systematic and no one stops it because Mr.

Graves has money and power and the law protects him instead of us.

Dinina looked up at Sarah.

What is this? What was Graves doing to these women? We do not know exactly, Sarah said.

But we know enough.

Over the past 10 years, Graves has purchased at least seven pregnant women at auction, always for suspiciously low prices, always women who were being sold because of personal disputes or complications with their previous owners.

He takes them to his plantation, keeps them isolated, and within months they disappear.

Some are reported as dying in childbirth.

Others are claimed to have run away, but none of them are ever seen again.

and the babies,” Dinina whispered.

“What happens to the babies?” “That is the question we cannot answer,” Hannah said.

“Some of the women who work at Graves’s plantation have reported hearing infants crying, but they never see the children.

It is as though the babies vanish as completely as their mothers.

” Dinina felt nausea rising.

She thought about Rachel and Margaret and the unnamed woman before them.

Thought about seven women over 10 years.

Thought about seven babies who had simply disappeared.

What kind of monster does this? Sarah closed the journal.

A monster protected by law.

Thornton Graves is wealthy, respected in certain circles, a member of the Savannah Planters Association.

He pays his taxes, attends church, contributes to civic projects, and because he is wealthy and white and male, no one questions him when enslaved women on his property disappear.

The law assumes he has the right to dispose of his property however he sees fit.

But Jacob stopped him.

Dinina said, “Jacob prevented Graves from buying me.

” “Yes, and in doing so, he marked both of you as targets.

Graves will want to know who Jacob is, why he interfered, what his interest in you could possibly be.

And when Graves starts investigating, he will eventually discover that Jacob works with the Underground Railroad.

At that point, both your lives will be in immediate danger.

“Then we need to leave tonight,” Dinina said, her voice rising.

“We need to run before Graves finds us.

” Sarah shook her head.

Running is exactly what Graves expects.

He will have men watching the roads, checking passes, questioning anyone who looks suspicious.

A white man traveling with a pregnant black woman that will attract attention immediately.

We cannot stay here indefinitely.

Hannah added, “This cabin is safe for now, but it is not invisible.

People know about this place.

Not many, but enough.

If Grave starts asking questions in the right communities, eventually someone will talk.

“So what do we do?” Dinina asked.

“We wait for Jacob to return.

” Sarah said, “He is working on something.

A plan that will get you north safely, but it requires time and coordination.

Until then, you rest, you eat, you take care of yourself and that baby.

Because once you start moving, there will be no stopping, no safety, just constant travel until you cross into free territory.

And if we are caught, if you are caught, you will be returned to Elias’s cartrite and he will ensure you never have another opportunity to escape.

If Jacob is caught, he will be tried for theft and conspiracy, and he will hang.

Those are the stakes.

That is what we are risking.

Dinina absorbed this information, the full weight of what these people were attempting on her behalf.

They were risking everything, freedom, safety, their lives to help someone they barely knew.

Why? Dina asked.

Why would you do this? Why would Jacob spend $1,200? Why would you hide me here? Why would any of you risk so much for me? Sarah reached across the table and took Diner’s hand.

because it is right.

Because the system that allows men like Elias Cartwright and Thornton Graves to exist is evil.

And because if we do not resist, if we do not fight in whatever small ways we can, then we are complicit in that evil.

You are not the first person we have helped, and you will not be the last.

This cabin has sheltered dozens of fugitives over the years.

People escaping, people heading north, people seeking freedom.

It is dangerous work, but it is necessary work.

Dinina spent three days in Sarah’s cabin.

Three days of relative peace that felt surreal given everything that had preceded them.

She ate meals prepared with care, slept in a real bed, felt the baby move inside her with increasing strength.

Sarah and Hannah treated her with kindness that seemed almost incomprehensible.

Kindness without expectation of service or submission.

kindness offered simply because they believed she deserved it.

On the morning of the fourth day, Jacob Marsh returned.

He arrived just after dawn, his horse lthered with sweat, his face drawn with exhaustion.

He had been riding through the night.

And when he entered the cabin, Sarah immediately knew something had changed.

“What happened?” Sarah asked.

“Graves knows,” Marsh said.

He sat heavily in one of the chairs, accepted the cup of water Hannah offered him.

He knows I am not who I claim to be.

He has been asking questions all over Savannah, showing my description to people, offering money for information.

How much does he know? Hannah asked.

Enough to be dangerous.

He knows I paid cash for diner, which suggests resources beyond what a normal traveler would carry.

He knows I left Savannah immediately after the auction, which suggests I did not actually need domestic help for business in the city, and he has discovered that no one named Jacob Marsh has registered at any hotel or boarding house in Savannah, which suggests the name is false.

Is it? Dinina asked.

Is Jacob Marsh your real name? Marsh looked at her for a long moment, then he shook his head.

No, my real name is Jacob Brennan.

I am originally from Pennsylvania and for the past 6 years I have been working with an organization dedicated to helping enslaved people reach freedom.

We operate across multiple states using false identities, safe houses, and carefully planned routes to move people north.

I came to Savannah specifically because we received information about you, about what Elias Cartwright was planning, about Thornton Graves’ pattern of acquiring and murdering pregnant women.

How did you receive that information? Dinina asked from Bethy, the woman who worked in Cartwright’s household.

She has been connected to our network for over a decade.

when she learned Elias was sending you to Savannah.

When she discovered the auction was arranged specifically to deliver you to graves.

She sent an urgent message through channels we have established.

She asked us to intervene to save you if possible.

And you came.

Dinina said, “You spent $1,200.

You risked everything for someone you had never met.

” Brennan’s expression was difficult to read.

I came because what Graves does, what he has been doing for years, represents evil beyond even the considerable evil of slavery itself.

The system allows him to torture and murder women with complete impunity.

If we do nothing, he will continue.

If we save you, we save not just your life, but potentially the lives of future women he would have targeted.

It is not charity, Diner.

It is resistance.

Sarah moved to the window looking out at the forest.

If Graves knows who you are, if he knows you work with the railroad, then he will be hunting you actively.

You cannot travel with Dinina.

Your presence will make her more visible, more vulnerable.

I know, Brennan said.

That is why the plan has changed.

Changed how? Dinina asked, feeling cold fear settle in her stomach.

You are not taking me north.

I am taking you north, but not directly and not alone.

There are people better suited for this than I am.

People who know the roots more intimately, who have connections I lack.

I am arranging for you to meet a conductor named Thomas Garrett.

He operates out of Wilmington, Delaware, and he has successfully guided over 200 people to freedom.

But Wilmington is hundreds of miles from here, Hannah said.

How will she reach him? By water, Brennan said.

There is a ship leaving Savannah’s port in 5 days.

A merchant vessel traveling to Philadelphia.

The captain is sympathetic to our cause.

He has agreed to hide diner in the cargo hold to transport her as far as Wilmington where Garrett will be waiting.

Once she reaches him, he will take her the rest of the way to Canada.

And you? Sarah asked what happens to you? I disappear.

I have other identities, other places I can go.

Graves will hunt Jacob Marsh, but Jacob Marsh will cease to exist.

The man he is looking for will simply vanish.

Dinina tried to process this information.

She would be traveling alone, hidden in the cargo hold of a ship, trusting her life to strangers whose only connection to her was a shared commitment to destroying the system that enslaved her.

It was terrifying, but it was also her only chance.

When do I leave for the ship? Dina asked.

Tomorrow night we will move after dark.

Travel through roots.

Graves will not be watching.

The captain is expecting you.

And he has prepared a hiding place below deck where you will remain for the duration of the voyage.

It will be uncomfortable, perhaps even dangerous if the weather turns rough.

But it is safer than traveling overland where Graves has influence.

What about my baby? Dinina said, her hand moving instinctively to her stomach.

What if I go into labor during the voyage? The captain has experience with such situations, Brennan said, though his voice carried uncertainty.

He has carried pregnant women before, and he knows how to assist if necessary.

But I will not lie to you, Dinina.

Child birth at sea is dangerous.

If complications arise, medical help will be limited.

I understand, Dina said, though she did not fully understand, could not fully comprehend the risks she was about to accept.

But she knew one thing with absolute certainty.

Staying in Georgia meant death.

If not from graves, then from someone like him, if not immediately, then eventually.

If not for her, then for her child.

At least running north offered possibility, however slim.

Sarah moved to diner and embraced her.

You are braver than you know, child.

You are going to survive this.

You and that baby both.

You are going to reach freedom.

And when you do, you remember us.

You remember that there were people who fought for you.

That night, Dinina could not sleep.

She lay in the darkness, listening to Sarah’s breathing, to the sounds of the forest outside, to the movement of her child within her body.

She thought about Ruth, her daughter sold away two years earlier.

wondered where that child was now, whether she was alive, whether she remembered her mother at all.

She thought about the seven women who had been purchased by Thornton graves.

Seven women whose names had been erased from history as thoroughly as their bodies had been erased from the world.

She thought about Elias’s cartrite, about the man who had raped her repeatedly and then arranged for her to be murdered to protect his reputation.

And she thought about the people helping her.

Bethy and Charleston.

Jacob Brennan risking his life.

Sarah and Hannah opening their home.

A ship captain she had never met agreeing to hide her.

Thomas Garrett waiting in Delaware to guide her to Canada.

All of these people connected by networks of resistance, by shared commitment to undermining the system that made Elias Cartrite and Thornton Graves possible.

It was beautiful and tragic in equal measure.

this underground web of humanity asserting itself against inhuman laws.

The next evening, as darkness settled over the forest, Jacob Brennan prepared the wagon.

He covered Diner with canvas, arranging it to look like he was transporting supplies rather than a human being.

Sarah and Hannah said their goodbyes, their embraces fierce and final, as though they understood this might be the last time they saw Dinina alive.

The journey to Savannah took 4 hours, traveling slowly along back roads, avoiding main thorough affairs where checkpoints might be established.

Brennan said almost nothing during the trip, his attention focused entirely on watching for signs of danger, for riders who might be Graves’s men, for any indication they were being followed.

They reached the waterfront just before midnight.

The docks were quieter at this hour, but not empty.

Dock workers loaded cargo onto ships, preparing for dawn departures.

Sailors moved between vessels.

Night watchmen patrolled with lanterns.

Brennan guided the wagon to a warehouse near the far end of the warf, a large wooden structure that smelled of tar and rope and saltwater.

He stopped the wagon beside a side door, then climbed down and helped Dinina emerge from beneath the canvas.

A man appeared from the shadows, tall and lean, perhaps 50 years old, his face weathered by years at sea.

“You are Brennan,” the man said.

“I am, and this is Diner.

” The captain, his name was Samuel Porter, studied Diner with an expression that might have been sympathy or might have been calculation.

“She is further along than I expected.

” “Five months,” Brennan said.

“Will that be a problem? It increases risk, but it is manageable.

Come, we need to get her aboard before the watch rotation changes.

They moved quickly through the warehouse and out onto the dock.

The ship was a threemasted merchant vessel, perhaps 90 ft long, its hull dark with age and weather.

A gang plank connected the dock to the deck, and Porter led them up without hesitation.

Once aboard, he guided them below deck, down a narrow ladder into the cargo hold.

The space was cramped and dark, filled with crates and barrels and coils of rope.

The air smelled of mildew and something organic that might have been rotting fruit.

Porter moved to the far end of the hold and pulled aside several crates, revealing a small space behind them, perhaps 5t by 3 ft, barely large enough for a person to lie down.

This is where you will stay for the duration of the voyage, Porter said.

I will bring you food and water twice daily.

But you cannot leave this space.

Cannot make noise.

Cannot allow yourself to be discovered.

If the crew finds you, I cannot protect you.

The voyage will take approximately 7 days, depending on weather and wind.

Can you endure that? Dinina looked at the cramped space, at the darkness, at the impossibility of what was being asked.

Then she nodded.

I can endure it.

Good, Porter said.

When we reach Wilmington, I will bring Thomas Garrett to you.

He will take you from there.

Until then, you trust no one except me.

You make no sound, and you pray that the weather holds.

” Brennan stepped forward.

He reached into his coat and withdrew a small cloth bundle.

Inside was money, perhaps $50 in various denominations.

“This is for you,” he said, pressing it into diner’s hands.

for when you reach Canada for starting your new life.

I cannot, Dinina whispered.

It is too much.

You can and you will, Brennan said.

His voice was firm.

You are going to survive this, Diner.

You are going to reach freedom.

And when you do, you are going to build a life for yourself and your child.

A life where no one owns you, where no one can take your children, where you are fully human under the law.

That is what we are fighting for.

That is why we risk everything.

So take the money, take your freedom and live.

Dinina felt tears she could no longer hold back streaming down her face.

She embraced Brennan, this stranger who had saved her life.

This man whose real name she had learned only yesterday.

This person who represented everything good that could exist, even in the midst of systematic evil.

“Thank you,” she whispered.

“Thank you for seeing me as human.

” Brennan held her for a moment, then stepped back.

Now go, hide yourself, and do not emerge until Porter tells you it is safe.

Dinina climbed into the small space behind the crates.

Porter arranged the boxes to conceal her completely, leaving only a small gap for air circulation.

The darkness was absolute.

She heard Brennan and Porter speaking in low voices, heard footsteps on the ladder as they returned to the deck, heard the sounds of the ship settling around her.

Then silence, broken only by the creaking of wood and the distant sound of water against the hull.

She was alone now, truly alone, hiding in darkness, trusting her life to people she barely knew, carrying a child who would either be born free or born into slavery, depending on whether this desperate plan succeeded.

The ship departed at dawn.

Dinina felt the motion change, felt the vessel begin to move, felt the gentle rocking that meant they were leaving the dock, leaving Georgia, leaving behind everything she had ever known.

For the first two days, the voyage was uneventful.

Porter brought food and water as promised, stale bread and dried meat and warm water that tasted of wood.

He spoke little, simply handed her the provisions, asked if she was managing, then departed.

The space was unbearably cramped, and Diner’s body achd from the inability to stretch or move freely.

Her pregnancy made everything worse.

the pressure on her bladder constant, the need to shift position frequent but impossible.

But she endured because endurance was all she had ever known, because enslaved people learned early that survival meant tolerating the intolerable, that freedom was worth any temporary suffering.

On the third day, the weather changed.

Diner heard thunder in the distance, felt the ship begin to pitch more violently.

The storm hit with full force that afternoon, transforming the gentle rocking into violent heaving.

The cargo hold became chaos, crates shifting with each massive wave, barrels rolling, ropes swinging.

Dinina pressed herself into the corner of her hiding space, her arms wrapped protectively around her stomach, praying the crates concealing her would not shift enough to expose her or crush her.

The storm lasted through the night and into the following morning.

During those hours, Dinina experienced fear beyond anything she had known before.

She had survived rape, had survived the sale of her child, had survived being sold herself for 19 cents.

But this was different.

This was nature itself trying to kill her.

Water and wind indifferent to human suffering, to human law, to human evil.

If the ship sank, she would drown in this hold, trapped behind crates, unable even to attempt survival.

Her child would die with her, both of them erased as thoroughly as the seven women Thornton Graves had murdered.

When the storm finally broke, when the motion of the ship returned to something resembling normal, Dinina waited for Porter to appear with food and water, but he did not come.

The morning passed, then afternoon, then evening.

No food, no water, no contact.

Diner’s throat burned with thirst and her stomach cramped with hunger.

She tried to remain calm, tried to tell herself that Porter was simply delayed, that the storm had created problems requiring his attention elsewhere on the ship.

But as the second day without provisions began, panic started to set in.

Had something happened to Porter? Had he been injured during the storm, or worse, had he been discovered helping her? Had the crew found out about her presence.

On the third day, without food or water, Dinina began to accept that she might die here.

She was weak, lightaded, her lips cracked, and bleeding.

The baby moved less frequently now, as though it too sensed the approaching end.

She thought about praying, but to whom? To a god who had allowed her to be enslaved, to be raped, to be sold like livestock? What god would sanction such a world? Then she heard footsteps on the ladder, heard someone moving through the cargo hold.

Please let it be porter, she thought.

Please let it be help and not discovery.

The crates in front of her hiding space shifted and light flooded in painful after days of darkness.

A face appeared, but it was not porters.

It was a younger man, perhaps 25, with red hair and a sailor’s weathered skin.

His eyes widened when he saw her.

Sweet Jesus, he whispered.

“There is actually someone here.

” Porter said, “There might be, but I did not believe him.

” Dinina tried to speak, but her throat was too dry.

The sailor, his name was Michael, lifted a canteen to her lips.

“Small sips,” he said.

“You have gone too long without water.

You need to drink slowly or you will vomit.

” Dinina drank and the water was the most beautiful thing she had ever tasted.

“Where is Porter?” she managed to ask.

“Dead,” Michael said.

His voice was grim.

“He fell during the storm, broke his neck.

We buried him at sea yesterday morning.

Before he died, he told me about you, told me where you were hidden, told me I needed to keep you alive until we reached Wilmington.

So, here I am.

” “You are going to help me?” Dinina asked, disbelieving.

Michael shrugged.

Porter was a good man.

If he thought you were worth saving, that is enough for me.

Besides, I have no love for the system that makes people property.

My father was Irish, came to America to escape famine, worked himself to death in factories.

I know what it means to be disposable to rich men.

So yes, I am going to help you.

We reach Wilmington tomorrow.

Until then, you stay hidden.

You stay quiet and you stay alive.

Understand? Dinina nodded.

Michael produced food from his coat, hard biscuits and cheese.

Eat slowly, he instructed.

Your stomach needs time to adjust.

Then he repositioned the crates, concealing her once more, and departed.

The ship reached Wilmington the following afternoon.

Dinina heard the sounds of docking, of sailors shouting instructions of cargo being unloaded.

She waited in her hiding place, every muscle tense, wondering if Michael would return, wondering if Thomas Garrett would actually be there, wondering if this final stage of the journey would succeed, or if she had come so far only to be captured at the last moment.

Hours passed.

The sounds of activity diminished.

Finally, footsteps approached, and the crates moved aside.

Michael’s face appeared, and beside him was another man, older, perhaps 60, with kind eyes and a calm demeanor.

“You are Diner,” the older man said.

“I am Thomas Garrett.

” Jacob Brennan sent word that you would be arriving.

“I am here to take you the rest of the way north.

” “Can you walk?” Dinina tried to stand, but her legs would not support her weight.

Days of confinement and dehydration had weakened her beyond what she had realized.

Garrett and Michael lifted her carefully, carried her up the ladder and onto the deck.

The sun was setting and the light made Diner’s eyes water.

She could see the Wilmington docks, could see buildings beyond, could see free territory for the first time in her life.

We need to move quickly, Garrett said.

There are people in this city who would gladly return you south for reward money.

My wagon is waiting.

We travel tonight.

They carried Dinina off the ship and into a waiting wagon.

Garrett covered her with blankets and they began to move through Wilmington streets.

“Where are we going?” Dinina asked.

“To a safe house first, where you can rest and recover your strength.

Then north through Pennsylvania and New York to Canada.

The journey will take weeks, possibly months, depending on your condition and the baby, but we will get you there, Dinina.

I have never lost anyone.

I have guided, and I do not intend to start with you.

” Dinina closed her eyes, allowed herself to feel the smallest measure of hope, the first real hope she had experienced in years.

She was not free yet, not legally, not safely, but she was closer than she had ever been.

And if she died tomorrow, at least she would die knowing she had tried, knowing she had resisted, knowing that people had risked everything to help her because they believed her life mattered, because they believed the system that enslaved her was evil and worth fighting.

That night, in a small house on the outskirts of Wilmington, Dinina slept in a real bed for the first time in over a week.

She ate warm food prepared by Garrett’s wife, a woman named Rachel, who treated her with the same kindness Sarah and Hannah had shown.

And for the first time since learning she was pregnant with Elias Cartwright’s child, Dinina allowed herself to imagine a future, a future where her baby would grow up free, where no one could sell them, where they would be fully human under the law.

It was a fragile hope, easily destroyed, but it was hope nonetheless, and hope Dinina was learning, was the most dangerous and necessary thing an enslaved person could possess.

Diner’s journey from Wilmington to the Canadian border took seven weeks.

Seven weeks of traveling at night through forests and farmland.

Seven weeks of hiding in barns and cellars and attics.

Seven weeks of trusting strangers whose only connection to her was a shared belief that slavery was an abomination that required resistance.

Thomas Garrett guided her through Pennsylvania, passing her from one conductor to another.

Each person in the chain knowing only what they needed to know, enough to help, but not enough to endanger the entire network if they were caught.

In a farmhouse outside Philadelphia, Dinina met a Quaker family named Coleman who gave her new clothes, sturdy boots, a warm coat for the journey ahead.

In Rochester, New York, she stayed 3 days with Frederick Douglas himself, the famous abolitionist who had escaped slavery years earlier and now dedicated his life to helping others achieve the same freedom.

Douglas spoke to her about the importance of telling her story once she reached safety, of documenting what had been done to her, of bearing witness so that future generations would understand the reality of slavery beyond the sanitized versions slaveholders preferred to present.

Your survival is an act of resistance, Douglas told her.

Every day you live free is a defeat for Elias Cartwright, for Thornton Graves, for every person who profited from your bondage.

Do not waste that victory by remaining silent.

By the time Dinina reached the Canadian border in late January of 1,850, she was 8 months pregnant, exhausted beyond measure, but alive.

She crossed into Ontario on a night so cold the ground was frozen solid, her breath visible in the frigid air.

The moment she stepped onto Canadian soil, she fell to her knees, not from weakness, though she was weak, but from the overwhelming realization that she had actually done it.

She had escaped.

She was free.

Not just spiritually or morally free, but legally free under the protection of a government that did not recognize property rights in human beings.

Thomas Garrett knelt beside her.

You made it, Dinina.

You are safe now.

No one can take you back.

No one can claim ownership of you or your child.

You are free.

Dinina wept.

great racking sobs that came from somewhere deep inside her, from the place where she had buried years of grief and rage and fear.

She wept for herself, for Ruth, for her mother patience, for the seven women Thornton Graves had murdered, for every person still enslaved in the south, for the sheer cruelty of a world that required such desperate measures simply to be recognized as human.

Garrett helped her to her feet and they walked the final mile to a settlement of formerly enslaved people who had established a community near the border.

The settlement was called Dawn and it consisted of approximately 200 people who had escaped slavery and were now building lives as farmers, craftseople, teachers.

They welcomed Dinina with open arms with food and shelter and the kind of safety she had never known.

3 weeks later on February 19th 1,850 Dina gave birth to a son.

The labor was difficult, lasting nearly 18 hours, but a midwife named Claraara, herself, a former enslaved person from Virginia, guided Dinina through it with patience and skill.

When the baby finally emerged, screaming his fury at the world, Dinina held him and felt something shift inside her.

Something that might have been joy or might have been terror at the responsibility of raising a free child in a world that still wanted to enslave him.

“What will you name him?” Claraara asked.

Dinina looked down at her son’s face, at his tiny fists waving, at the undeniable evidence that Elias Cartwright was his father written in his features.

For a moment she considered naming him after someone she had loved, after her mother, or after William, the person she might have wanted his father to be.

But then she thought about all the people who had helped her reach this moment.

All the people who had risked everything, and she made her decision.

His name is Jacob, she said.

After Jacob Brennan, the man who saved my life.

Claraara smiled.

Jacob is a good name.

A strong name.

That boy is going to grow up free.

Diner.

He is going to have opportunities you never had.

He is going to live in a world where no one owns him.

Make sure he knows how many people fought to give him that chance.

I will, Dinina promised.

I will tell him everything.

Dinina lived in Dawn for three years, working as a seamstress and helping other newly arrived fugitives adjust to freedom.

She learned to read more fluently with help from a teacher in the settlement, and she began writing down her story, documenting what Elias Cartwright had done to her, what Thornton Graves had planned to do, how the Underground Railroad had saved her life.

In 1853, she married a man named Samuel Richards, a blacksmith who had escaped from Maryland 5 years earlier.

Samuel was kind and patient, and he understood that Diner’s past was not something that could be forgotten or erased, but something that needed to be honored and remembered.

They had two more children together, both daughters, and they raised all three children with the understanding that their freedom had been purchased with the courage and sacrifice of people who believed justice mattered more than law.

But Dinina never forgot about Ruth, her first daughter, the child Elias Cartwright, had sold in 1847.

She spent years trying to locate her, writing letters to abolitionists in the South, asking if anyone had information about a girl sold in Charleston, a girl who would be approximately 10 years old by 1850, a girl with light skin and a name that might or might not still be Ruth.

The search consumed her, became an obsession that Samuel gently tried to temper, but ultimately supported because he understood that no mother could be whole while her child remained lost.

In 1856, Dinina received a letter from a Quaker missionary in South Carolina.

The letter contained information about a girl matching Ruth’s description who had been working on a plantation outside Charleston.

The missionary had managed to make contact with the girl, had confirmed her original name was Ruth, had learned that she remembered her mother despite being only 4 years old when they were separated.

The missionary wrote that Ruth was alive, was relatively healthy, but was still enslaved.

Dinina made a decision that terrified Samuel and everyone who knew her.

She decided to go back, not permanently, but to attempt a rescue, to use the same underground railroad network that had saved her to now save her daughter.

It was extraordinarily dangerous, returning to the South as a formerly enslaved person.

Any white person who recognized her could claim ownership, could drag her before a magistrate, and present evidence that she was fugitive property.

But Dinina did not care about the danger.

Ruth was her daughter, and she had already lost too many years.

In the summer of 1,856, Dinina traveled south with two experienced conductors, men who had guided dozens of people to freedom, and who understood the roots, the safe houses, the strategies for moving through hostile territory without detection.

They reached South Carolina in August, made contact with the missionary, and learned that Ruth was now working on a small farm owned by a widow named Margaret Foster.

The rescue was planned for a moonless night in early September.

Diner and the conductors approached the farm after midnight, found Ruth sleeping in a small cabin with three other enslaved women, and woke her gently.

Ruth, now 13 years old, stared at Dinina with wide eyes.

Do I know you? Ruth whispered.

I am your mother, Dina said, her voice breaking.

I came back for you.

I promised myself I would never stop looking and I kept that promise.

Now we are going to leave here.

We are going to go north and we are going to be free together.

Ruth began to cry and so did Dinina and the two conductors had to remind them that time was critical, that they needed to move immediately before anyone discovered they were gone.

They made it back to Canada by late October, traveling the same routes Dinina had used 6 years earlier, relying on the same network of brave people who sheltered fugitives.

When they finally crossed the border and reached dawn, when Dinina was able to introduce Ruth to Jacob and Samuel and her daughters, when she was able to tell Ruth that she was safe now, that no one would ever take her again.

Dinina felt something she had not felt since before Ilas Cartwright first raped her.

She felt complete.

The years that followed were not easy.

Freedom did not erase trauma, did not heal wounds that ran so deep, but they were years of building, of creating a life defined by choice rather than coercion, of raising children who understood their history and their responsibility to fight for those still enslaved.

Dinina continued to work with the Underground Railroad, continued to help other fugitives, continued to document stories that needed to be told.

And she never stopped thinking about Thornton Graves, about the seven women he had murdered, about the evil that men could commit when the law protected them instead of holding them accountable.

She wondered if Graves had continued his pattern after she escaped, if other women had been purchased and disappeared, if anyone would ever stop him.

The answer came in 1863 in the middle of the Civil War when Union forces occupied Savannah.

A regiment of black soldiers, formerly enslaved men now fighting for their freedom, were stationed at various plantations in Chattam County.

One of those plantations belonged to Thornton Graves, though Graves himself had fled south ahead of Union advancement, abandoning his property to avoid capture.

The soldiers who occupied Graves’s plantation began exploring the property, searching for hidden valuables, for weapons, for anything that might be useful to the Union cause.

A sergeant named Isaiah Freeman, a man who had escaped from slavery in Alabama 3 years earlier and joined the Union Army to fight against the system that had enslaved him.

He was searching the old tobacco barn at the edge of the North Field when he noticed something strange.

The floor of the barn was wooden planks, but in one corner the planks seemed newer than the rest, as though they had been replaced recently.

Freeman pried up the planks and discovered a space beneath, a cellar that had been deliberately concealed.

What he found in that cellar would haunt him for the rest of his life.

There were bodies, eight women, buried in shallow graves, their remains wrapped in canvas, their skulls showing evidence of violence, and beside them smaller remains, infants, some appearing to be newborns, others perhaps a few months old.

All dead, all buried in secret, all hidden by a man who had used the law to acquire them and then used isolation to murder them without consequence.

Freeman reported the discovery to his commanding officer, a white captain from Massachusetts named Henry Clark.

Clark documented the findings, took testimony from enslaved people who had worked at Graves’s plantation, people who confirmed that Graves had purchased pregnant women at auction, had kept them isolated in the barn, and that those women and their babies had subsequently disappeared.

The testimony was consistent, detailed, damning.

Thornton Graves had been operating a murder factory for over a decade, using the auction system to acquire victims, using the laws indifference to enslaved people’s lives to avoid detection, using his wealth and status to ensure no one questioned him.

Captain Clark prepared a full report, intending to use it as evidence of the barbarity of slavery, as proof that the system enabled not just exploitation, but systematic murder.