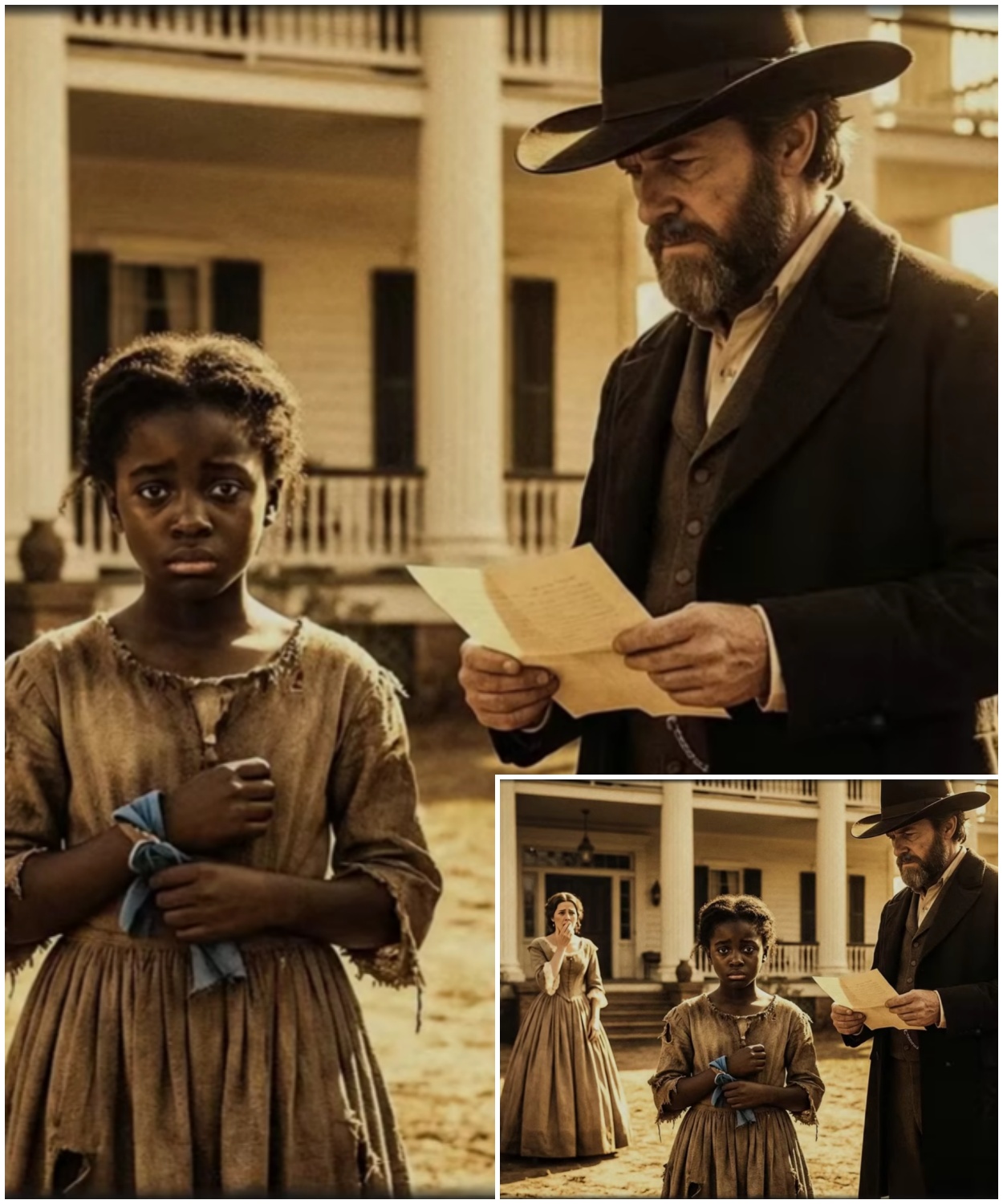

They wrote her price down like you’d note the cost of a rusty nail.

Lot 17, female child, approximate age.

What would you say, Mr.

Dobs? The traitor squinted at the small figure on the block.

She was barefoot, ankles too thin for the iron ring that had hung there last month, when she’d belonged to another man’s inventory.

Her dress was little more than a gray rag, damp with the morning drizzle.

Eight.

Nine.

He said, “Hard to tell when they’re stunted.

She don’t look like much.

” The crowd shifted.

Most men weren’t interested in children that small.

A boy could grow into a plow hand, a girl into a field worker, or worse.

But it took years of feeding before either paid for themselves.

And this one, this one had that hollow look that said somebody had already tried to make her work like a grown woman and nearly rung the life out of her.

Up close, her eyes were the only thing that didn’t look worn out.

Too big for her face, dark and steady, taking in everything without giving much back.

When the traitor’s assistant grabbed her chin and turned her head roughly from side to side, she didn’t cry.

She just watched the line of men staring at her like she was the only person in the yard who understood exactly what the numbers on the slate meant.

“Mother dead,” the traitor called.

Came in as part of a debt settlement.

Previous owner let her run half wild.

Could be trained up for housework.

could be put to light field labor.

Breeding potential in a few years, he said the last part like a man pointing out a tree that might someday bear fruit.

A few men chuckled.

One muttered, “I ain’t paying good money to feed another man’s mistakes.

” At the edge of the circle, Henry Caldwell shifted his weight from one boot to the other and tried not to think about his own mistakes, waiting for him back at the plantation.

The folded letter in his coat pocket pressed against his chest.

Another notice from the bank, polite words wrapped around hard numbers.

Interest aars collateral.

The kind of language that made a man feel like a field left too long without rain, cracked and close to breaking.

He hadn’t come to town meaning to buy anyone.

He’d come to talk to Mr.

Hathaway at the bank about extending his note.

But Hatheraway had been delayed on other business, and the auction yard had a way of pulling a man in while he waited.

Habit more than hunger.

Come now, gentlemen,” Dobs called.

“She may be small, but she’s sound.

No visible deformities, teeth decent.

You can see she’s got all her fingers.

” He lifted the girl’s hand, prying her fingers apart to show the crowd.

Something small and dirty and frayed shifted at her wrist.

A bit of string with a scrap of cloth tied to it.

the remains of some long ago ribbon or tag.

Before Henry could see more, the traitor let her hand drop.

“Who’ll start me at $2?” Dobs asked.

Silence, a cough, a laugh, a spit into the mud.

The rain came down a little harder, pattering on hats and shoulders.

“All right then,” Do said, forcing a smile.

“$1.

You won’t find a cheaper lot today.

Nothing.

The girl shifted her weight.

The plank under her feet creaked.

She looked out over the sea of faces and saw nothing soft there.

If fear lived anywhere in her, it had long ago learned to sit very still.

Henry’s gaze drifted back to the letter crumpled in his pocket.

$1 might as well have been a hundred when a man was short on every bill that mattered.

Still, he felt something like shame creep up the back of his neck as he watched no one raise a hand for a living child.

Dob’s side wiped rain from his eyes.

All right, gentlemen.

Let’s not play stubborn.

Who’ll start at 50 cents? A man near the front snorted.

She ain’t worth the trouble, he said.

I got dogs at home.

Eat more than she’ll ever be worth.

Laughter rippled from somewhere behind Henry.

Another voice drawled.

I’d take her for 20 cents just to keep the flies off your block, do sold you a broom for that yesterday, someone else said.

The jokes piled up, cheap and easy, each one chipping a little more off whatever was left of the girl’s sense that she was human.

Henry shifted again, irritation prickling at him now.

It wasn’t kindness.

It was a different kind of discomfort.

The kind that came when a man saw a spectacle that hid too close to his own anxieties.

He was tired of hearing numbers attached to things he couldn’t quite afford.

Tired of watching the bank judge his worth line by line.

He found his hand lifting before he’d fully decided.

19 cents, he called, voice cutting through the noise.

The yard went quieter than such a small number deserved.

Dobs blinked.

Come again, Mr.

Caldwell.

19.

Henry said, “You want to scrape the bottom? Might as well do it properly.

I’ll take her for 19 cents and save you the trouble of feeding her another week.

” A few men laughed, this time with a hint of mean admiration.

Trust Caldwell to haggle the price of a child lower than a stamp.

Dobs hesitated, pride wrestling with practicality.

Every day a lot stayed unsold.

It ate into his margin.

This one had already been turned down twice in other towns.

She was becoming dead weight.

“Do I hear better than 19?” he called.

“20, 25.

” “Anyone?” The yard answered with silence and rain.

Finally, Dob sighed.

“Sold,” he said, “to Mr.

Henry Caldwell for the princely sum of 19.

” A battered gavel came down on the block with a hollow thud that sounded too much like a closing door.

The girl didn’t move.

No one cheered.

She stepped down when the assistant jerked his head, the chain at her ankle clinking softly as they unclipped it.

She stumbled once on the wet step and writed herself without help.

Up close, Henry saw that the scrap of cloth at her wrist had once been blue, striped with white, now faded to the color of old sky.

“Two tiny letters were stitched there in clumsy thread, nearly worn away by time and dirt.

” “Tag from the last owner,” Dob said, noticing his glance.

“You can cut it off.

Means nothing now.

” Henry made a mental note to do so later.

The last thing he needed was another man’s mark on something he’d paid for, however little.

In the trader’s office, he counted out the coins with a rofful shake of his head.

“You going to put that one to work in the house?” the clerk asked, scratching out a receipt.

“Maybe,” Henry said.

“Maybe I’ll let her carry kindling till she grows into something useful.

Can’t be worse than some of the stock I’ve got now.

You’d be surprised, the clerk muttered.

Trouble comes in all sizes.

When Henry stepped back into the yard, the girl stood where they’d left her, small and damp and stubbornly upright.

He studied her a moment.

“What’s your name?” he asked.

She hesitated.

Names had been taken from her before, traded like everything else.

They called me Nora, she said finally.

They he asked.

She lifted one shoulder.

The last place.

You had another before that.

Her eyes flickered.

He caught the ghost of something there.

Loss maybe or a memory shoved down so deep it only showed itself when surprised.

“Yes, sir,” she said.

He didn’t push.

The story of which man had first bought her mother, of which paper bore the original price was not one he needed to balance his accounts.

He jerked his chin toward the street instead.

“Come on then, Nora, for now,” he said.

“We’ll see what 19 cents buys these days.

” As they walked toward the buggy, rain pattering on the brim of his hat and into her hair, he felt a strange uneasy satisfaction.

There was something almost defiant in slapping such a ridiculous figure onto a purchase.

When the bank looked at his books, they’d see the usual feed tools minor stock additions.

No one would care about a single line that read one female child 019 to learn to Henry it was joke he could afford a story to tell times are so tight I’m buying children for loose change to Nora it was a number that would lodge in her bones 19 cents less than a decent meal in town less than a cheap knife a price that said she wasn’t even worth the smallest round number.

The buggy jolted as they hit the ruts outside town.

Norah gripped the side, keeping her balance by instinct.

Henry watched her out of the corner of his eye, noting how she scanned the roadside, how she flinched at certain sounds and ignored others.

“You from around here?” he asked suddenly.

She shook her head.

“Don’t know,” she said.

been moved too much.

Her fingers brushed the faded cloth at her wrist, almost without her noticing.

For a flash, Henry saw the letters again.

MB, or maybe NB, the thread too frayed to be sure.

Something about them tugged at the back of his mind.

A shape half remembered from some other piece of paper he’d once signed without reading all the way through.

He frowned, shook it off.

He had bigger worries than a scrap tag on a cheap child.

The farm needed a new gin belt.

The bank wanted its money.

His wife’s latest letter from her father mentioned concerns about your management of Margaret’s dowy assets.

Words that made his teeth grind.

If there was any connection between the girl at his side and the lines in his ledgers, he didn’t see it.

Not yet.

The Caldwell Place rose out of the mist an hour later.

Two stories of peeling white paint, flanked by rows of cotton that looked greener from a distance than they did up close.

The slave quarters hunched behind like low, dark echoes.

As they rolled into the yard, a few heads turned.

Curiosity was the only luxury the enslaved people allowed themselves freely.

“Henry climbed down, then jerked his head for Norah to follow.

” “You’ll take orders from the housekeeper for now,” he said.

“Light chores.

We’ll see where to put you.

” “Yes, sir,” she said.

As he handed her over to the older woman at the kitchen door, he caught the way the housekeeper’s eyes narrowed just a fraction at the sight of the girl’s face.

“What?” he asked more sharply than he meant to.

“Nothing, sir,” the woman said quickly.

But when he turned away, she looked at Nora again, harder this time, as if she were staring at a ghost wearing rags.

You come with me, child, she murmured.

We’ll get you washed.

In the dim light of the kitchen, with the rain beating on the roof and the smell of simmering beans in the air, the housekeeper took a damp cloth to Norah’s wrist.

She wiped away years of dirt until the faded blue scrap showed clearer.

The letters on it stood out just enough now to read.

MB.

The housekeeper’s breath caught.

Her mind flew to another piece of cloth packed years ago in a trunk that had rolled up to this same house on a different rainy day.

A trunk that had belonged to Miss Margaret Bowmont before she became Mrs.

Caldwell.

“That can’t be,” the housekeeper whispered to herself.

Norah looked up.

“Ma’am?” Nothing, the woman said too quickly.

She cleared her throat.

You remember where you got this? Norah frowned.

My first mama tied it on me, she said slowly.

Said it was so I wouldn’t be lost.

They tried to cut it off when they sold me, but I bit.

A flicker of fierce pride crossed her face.

I kept it.

The housekeeper’s hands shook.

She had been here long enough to remember the day a different young woman had been sold away from this family in another city under another name.

Long enough to remember the half-heard rumors about a Bowmont girl who’d gone too far with someone she shouldn’t have and the quiet disappearance that followed.

She stared at the letters again.

MB Margaret’s maiden name had been Bowmont.

Her oldest sister’s name had been Maryanne.

Lord help us.

The housekeeper breathed.

19 cents.

The master thought he’d bought a cheap child.

He hadn’t realized yet that he’d brought something else onto his land.

A living piece of his wife’s family history stitched to a scrap of cloth carrying a connection every ledger in town had tried to forget.

Hester didn’t sleep that night.

She lay on her pallet near the kitchen door, eyes open, ears full of the old house sounds.

Mice in the walls, wind fingering the shutters, someone in the quarters coughing.

But her mind was in a different time, a different town.

watching a different girl step into a carriage with a trunk that had a blue striped ribbon tied around the handle.

Maryanne Bowmont, Miss Margaret’s older sister, had laughed that day.

People always laughed around her.

She laughed when her mother scolded, laughed when her father warned her about certain friendships that weren’t fitting for a lady.

She’d laughed even when Hester had whispered, “Miss Maryanne, you be careful now.

White girls don’t get to play with fire and not get burned.

” Then one day, the laughter had stopped.

There had been whispers behind doors.

Visits from a doctor, from a pastor, from men whose voices carried words like shame and situation.

Maryanne’s belly had swelled and then suddenly she was gone.

Packed off to visit relatives for a season that stretched into a year.

When she came back thinner and quieter, there was a new hardness in Mr.

Bowmont’s eyes and a new rule in the house.

No one was to mention that year or anything that had happened in it ever again.

Hester had not seen the baby.

She’d only heard muffled crying one night through a wall and seen the next morning a small bundle carried out the backway.

A scrap of blue striped cloth had hung briefly from the blanket, then vanished into the carriage.

Now years later, she stared at the same pattern tied around a slave child’s wrist.

The thread was cheaper, the cloth more frayed.

But the stripes old still, she told Nora, voice tighter than she meant.

I’m trying to see.

Nora didn’t squirm.

She was used to other people’s hands arranging her like furniture.

My mama, she repeated, the first one.

She worked in a house, not the fields.

Said this meant I wasn’t to be mixed up or forgotten.

that work out for her? Hester asked before she could stop herself.

Norah’s eyes went flat.

They sold her, she said.

Sold me after.

So I guess no.

Hester let the child’s wrist go.

You keep that on, she said.

No matter who tells you, cut it.

You hear? Yes, ma’am.

Norah said, surprised by the urgency.

Now hush, Hester said.

We got work in the morning.

But when morning came, Hester’s first errand wasn’t the stove.

It was the big house.

She waited until she heard Mr.

Caldwell right out.

Off to argue with the bank again.

No doubt.

His departure left the house looser like a belt let out a notch.

The moment his horse’s hoof beats faded down the lane, Hester wiped her hands on her apron and climbed the back stairs.

She found Margaret in the sitting room, a book open in her lap, eyes not moving on the page.

The mistress looked up when Hester stepped in.

Yes, she said.

Is there some issue in the kitchen? Not in the kitchen, ma’am.

Hester said.

In the yard, maybe.

In the past, surely.

Margaret’s brows drew together.

You’re talking in riddles, Hester.

I’m talking in threads, Hester said, moving closer.

Threads from a cloth I seen before.

She held up her own work roughened hand and mimed a band around her wrist.

Blue stripes, she said.

White in between.

Two letters stitched clumsy but loving.

M and B.

Margaret’s face drained of color so fast.

Hester thought.

For a second she might faint.

Where did you see that? She whispered.

On the new girl the master brought home last night.

Hester said the 19 cent child.

He called her Nora.

Margaret shut the book, her fingers pressed hard into the cover.

You must be mistaken, she said automatically.

Maybe, Hester aloud.

But I seen that cloth once before on a trunk.

What came back without the baby that left with it.

The air between them thickened.

“You were talking about my sister,” Margaret said finally.

“About Maryanne,” Hester inclined her head.

“I was here then,” she said.

I remember the doctors, the visit to relatives, the way your mama stopped letting her go out without somebody watching, then being sent away again.

This time quiet.

And that bundle went out the back door with a scrap of sky tied to it.

Margaret’s jaw tightened.

“My father took care of it,” she said stiffly.

“Arangements were made.

” “The child.

” She stopped, swallowing the next words.

The child was placed.

That was the phrase they’d used in hushed tones over brandy.

Placed like china in a cabinet.

How old would that child be now? Hester asked gently.

If she’d lived.

Margaret did the math without wanting to.

Nine, she said.

Or 10.

She’s standing in your kitchen, Hester said, calling herself Nora.

with your family’s letters tied to her wrist so she wouldn’t be lost.

Margaret’s hand flew to her mouth, then dropped just as quickly as if she’d caught herself about to show too much.

“No,” she said half to herself.

“My father would never would never what?” Hester asked quietly.

He’d never sell his own blood.

Never send a baby someplace nobody could ask questions about it.

You sure you want to finish that sentence, ma’am? Memories crashed into Margaret like waves, her father’s hard voice, the pastor’s gentle lies about forgiveness, her mother’s red eyes, Maryanne’s laughter turning brittle.

The way when they spoke of the incident, they used phrases like regrettable and unfortunate and handled.

You said the tag was MB? She asked.

Yes, ma’am.

Hester replied.

Maryanne Bowmont or some other girl with the same letters who cried in the same room and disappeared the same way.

Coincidence like that, I don’t put much stock in.

Margaret turned away, looking out the window toward the fields.

The rows of cotton blurred.

“What are you asking me to believe?” she said.

“That the child in my kitchen is what? My niece? My sister’s bastard?” “Some reminder of a scandal my family paid good money to erase.

” “I ain’t asking you to believe nothing,” Hester said.

I’m telling you what my eyes saw then and now.

What you do with it is your burden.

Silence stretched.

A fly worried the air between them.

Does Mr.

Caldwell know? Margaret asked.

Not yet, Hester said.

Far as he’s concerned.

She’s just another mouth for you to feed and him to work.

19 cents worth of trouble.

Margaret let out a breath that sounded too much like a sob.

“You think I should tell him?” she asked.

Hester hesitated.

“You want my honest mind?” “I didn’t call you up here for lies,” Margaret snapped, then softened.

“Please.

” “Then no, ma’am,” Hester said.

I think a man who sees 19 cents when he looks at a child don’t deserve to know what she really cost your sister.

That afternoon, Margaret went to the kitchen herself, something she rarely did when there wasn’t a party to supervise.

The enslaved women straightened, hands flying faster over pots and knives.

Hester pretended to be fussing with a sack of flour, watching from the corner of her eye.

Norah stood at the table, sorting beans.

She had washed up as best she could.

Under the dirt, the lines of her face were finer than Henry had noticed.

Her nose had a little tilt at the end.

Her mouth compressed when she concentrated in a way that stabbed Margaret with a memory she thought she’d buried.

Maryanne squinting at embroidery, tongue peeking out in the same unconsciously childish way.

“What did you say your name was?” Margaret asked.

“Nora stiffened.

” “Nora, mom,” she said.

“Who gave it to you?” “My first mama,” Norah replied.

She said it sounded like no rain and no running mixed together.

Things she wished she could give me.

Margaret’s throat tightened.

“Hold out your hand,” she said.

Nora obeyed.

The blue strip around her wrist looked smaller now that Margaret knew what she was seeing.

“Who tied this?” Margaret asked, fingered, brushing the cloth.

“Mama?” Nora said.

She said, “If anybody ever cared to look close, they’d see I belong to something.

” “She was right,” Margaret murmured.

Nora blinked.

“Ma’am,” Margaret let the cloth fall.

“Nothing,” she said too quickly.

“We’ll have you in the house from now on.

Hester will show you your duties.

” “Yes, ma’am,” Norah said.

As Margaret turned to go, Norah spoke again, blurting the question that had sat in her chest since the yard.

“Ma’am, do you know who my father is?” Hester closed her eyes.

Margaret’s hand tightened on the doorframe.

“Children like you seldom get tidy answers to that,” Margaret said, not unkindly.

“Sometimes the truth is a knife we can’t afford to handle.

” Norah’s jaw set.

“I just wanted to know if he ever looked for me,” she said.

Margaret swallowed.

“If he did,” she said.

“He looked in the wrong place.

Men like him always do.

She left before the girl could ask more.

That night in their bedroom, Henry tossed the bank letter under the dresser with a curse.

Hatheraway’s tightening the screws again, he said.

Says if we don’t show improvement by harvest, he’ll have to revisit the terms.

Man talks like he’s discussing the weather.

Margaret sat at her vanity, brushing her hair.

In the mirror, she watched her husband’s reflection pace.

“Perhaps if you spent less time at Dob’s auctions and more in the fields,” she said lightly.

“I barely spent anything today,” he snapped.

“Picked up that little girl for less than a cup of coffee.

Cheaper than a fence post.

Might even make herself useful.

” Is that how you measure usefulness? Margaret asked.

By the cost of acquisition.

Yes, he said bluntly.

Isn’t that how your father measures everything he lends us? The mention of her father made her flinch.

The man who’d handled Maryanne’s situation.

The man whose money Henry was now drowning under.

You gave the girl a name? Henry asked.

more to fill the air than out of real interest.

She already had one, Margaret said.

Nora.

Fine.

He said, “Nora Caldwell’s property.

We’ll see if she earns her 19 cents.

” He didn’t see the way Margaret’s fingers tightened around the brush.

A few days later, a letter arrived from her father.

It came folded neat in a hand that had never known a day’s manual work.

Margaret took it to the parlor to read in private.

Outside, the sun hammered the fields.

Inside, the world narrowed to ink and paper.

Concerned to hear of your husband’s continuing difficulties with the hathaway, note, you must impress upon him the importance of maintaining our family’s standing.

You know, I have shouldered more than my share of unfortunate outcomes already.

That phrase again, her eye snagged on a line halfway down the page.

I trust you recall without my needing to be explicit.

The necessary corrections made when your sister’s youthful foolishness threatened to stain our name permanently.

I will not have my grandchildren or their husbands dragging us again into such murky waters.

Her stomach nodded.

Murky waters.

Necessary corrections.

A baby bundled out the back door with blue striped cloth tied at the wrist.

She read the paragraph twice, then a third time, as if the repetition might change the words.

In the days that followed, she began to watch Nora the way a woman studies an old portrait, looking for familiar lines, searching for echoes of people she once knew, the tilt of the girl’s head when she listened, the way she chewed the inside of her cheek when she was nervous, the small, defiant lift of her chin when scolded.

One evening at supper, Henry barked at Nora for spilling a little gravy on the tablecloth.

“For God’s sake, girl,” he snapped.

“It’s not that hard to hold a spoon steady.

” Norah’s shoulders hunched, but her eyes flashed.

“My hand steady enough when I’m working,” she muttered under her breath.

“Maybe [clears throat] the table’s what’s crooked.

” It was exactly the kind of thing Maryanne would have said to their father.

quietly, just loud enough to be heard, daring him to push harder.

Margaret’s breath caught.

For a moment, she wasn’t looking at a slave child.

She was staring at her sister across a dinner table years ago, watching her defy their father with a joke instead of a shout.

Henry slammed his hand on the table.

“What did you say?” Nothing, sir,” Norah said quickly.

Margaret’s voice cut across his.

She said she’d be more careful.

She lied smoothly.

“And she will.

” “Won’t you, Nora?” “Yes, ma’am,” Norah murmured.

Later that night, when Henry had gone out to the porch to smoke and grumble about the weather, Margaret found Norah in the pantry stacking jars with a care that borded on obsession.

“You mustn’t talk back to him,” Margaret said quietly.

“Not even a little.

” “He owns my back,” Norah said, not turning around.

“Not my tongue.

” “For now, he owns both,” Margaret replied.

That’s the curse of this place.

She stepped closer.

Do you know how old you are, Nora? About 10, Norah said.

Maybe 11.

How long ago did your mama tie that ribbon on you? Nora frowned, thinking.

I was real little, she said.

Could still sit on her hip.

She used to tell me, “Don’t you ever forget where you come from, even if they change your name 10 times.

” Then she’d tap it.

Right here.

Norah touched the scrap of cloth.

Said it was my reminder.

Did she ever say where she worked? Margaret asked.

Before in a big house, Norah said.

Said the lady of the house was pretty but sad.

Said the man who owned it liked to decide everything, even who smiled, who cried, but she never said their names.

just that they was important.

Important.

Clean word for people who could make babies vanish when they didn’t fit the picture.

Margaret felt something inside her settle into a cold, terrible certainty, the timeline fit, the letters fit, the mannerisms fit.

Norah wasn’t just any child.

She was the living consequence of Maryanne’s youthful foolishness.

the fragile secret her father had tried to erase with money and distance.

Somehow, through bad luck or divine irony, she had been sold around and back until she landed on the block the same day Henry decided to kill an hour at the auction.

The plantation master had bought a young slave for 19 cents.

He had also unknowingly bought his wife’s blood.

That night, Margaret lay awake beside her husband and watched his profile in the dark.

He snored lightly, oblivious.

The man who fredded about his books, who counted bales and coins, had no idea that the cheapest purchase he’d ever made might be the costliest in ways he would never understand.

In the morning, she went to her writing desk and took out a fresh sheet of paper.

Her hand shook only slightly as she wrote to her father.

She did not mention Nora by name.

She only asked in careful phrases whether all matters pertaining to past family indiscretions remained settled and unreachable.

She knew what answer would come.

Yes.

All handled, all placed, all forgotten.

That was how men like him slept at night.

But as she sealed the letter, she also knew something else.

The child in her kitchen was a crack in that story.

A flaw in the carefully painted portrait of the Bumont line.

A reminder that blood and ink did not always obey the same rules.

Her husband saw 19 cents on a receipt.

She saw her sister’s eyes in a small, stubborn face, and her father’s arrogance in the fact that that face now scrubbed his son-in-law’s floors.

The hidden connection sat at their table, refilled their cups, and listened.

And sooner or later, Margaret knew.

Henry Caldwell would notice that the girl he’d bought like a trinket had more claim on his house than any of the strangers he’d sold off to meet his debts.

The only question was what he would do when he did.

Henry [clears throat] noticed it the way a man notices a leak.

Too late and all at once.

It started small.

He was in the yard one afternoon watching the hands bring in bales from the far field when he saw Norah walking ahead of the others with a basket of mended clothes.

The sun hit her just right, lighting up the side of her face.

The tilt of her chin, the set of her mouth when she squinted into the light.

Something about it snagged his eye.

For a second, he thought he was looking at Margaret as a girl.

Not the woman in his house now, ironed stiff by duty and disappointment, but the younger version he’d married.

Quicker with a smile, sharper with her jokes, less practiced at swallowing anger.

The moment passed.

He shook his head, irritated at himself.

People saw what they wanted to see.

If he’d married a farm girl instead of a merchant’s daughter, he’d probably be finding her face in every milkmaid under the sun.

But the feeling came back.

At supper, when Norah poured his coffee, the way she shifted her weight was pure bowont, hips steady, shoulders straight.

a certain unconscious grace he’d always associated with good breeding, the phrase his father-in-law liked to use.

He wasn’t the only one who noticed.

“You’re letting the servants imitate their betters now,” one neighbor joked over cards one evening, nodding toward Nora as she passed the open door.

“That one walks like she owns the place.

” The men laughed.

Henry forced a chuckle, but something about the comment stuck like a splinter.

That night in bed, he mentioned it to Margaret, half mocking, half curious.

Do sold me one with heirs this time, he said.

Little 10-year-old thinking she belongs at the big table.

Margaret was brushing her hair, long strokes that had become a ritual armor.

“Maybe she comes by it honestly,” she said, eyes on the mirror.

“How’s that?” Henry asked.

“Some children are born into the wrong rooms,” she said.

“Doesn’t mean the blood forgets the right ones,” he snorted.

“You’re starting to sound like your father,” he said.

All that talk of lines and stock and good breeding.

If I sounded like my father, Henry, she replied calmly, that child would be on another man’s ledger by now, far away, where no one could see her face and ask questions.

The remark hit him sideways.

He rolled onto his back, staring at the ceiling.

“What questions?” he asked after a moment.

Margaret’s brush slowed.

About why a little girl from nowhere wears cloth that looks like it came off a Bowmont trunk, she said.

About why her mannerisms match members of my family who have never set foot on this plantation.

He frowned.

“What cloth?” “The band on her wrist,” she said.

“You didn’t notice.

” “I noticed a dirty rag,” he said.

Do said it was nothing.

Do says a lot of things, Margaret murmured.

Usually whatever makes a sale easiest.

Silence stretched between them.

Full of old stories neither quite wanted to name.

You’re suggesting what exactly? Henry asked.

Margaret set the brush down.

I am suggesting, she said slowly.

that if you are going to buy children at auction for the price of pocket change, you ought to at least look close at what you’re buying.

Names, marks, histories other men tried to throw away.

He turned his head toward her.

You think she’s related to you? I think my father once paid good money to make sure my sister’s baby was someone else’s problem, Margaret said.

I think problems have a way of finding their way home.

The thought unsettled him more than he wanted to admit.

A cheap child was a cheap child.

Blood complicated things.

Blood made a man feel like the ground under him wasn’t as solid as he’d believed.

Even if that were true, he said, what difference would it make? She’s still a slave.

Nothing in the law changes because of a scrap of cloth and your memories.

Margaret’s eyes went cold.

The law isn’t the only ledger that matters, she said.

Some accounts are kept elsewhere.

He rolled his eyes, but he didn’t sleep well.

A week later, the banks elsewhere came calling.

Mr.

Haway arrived in a polished buggy with dustless boots and a briefcase that probably cost more than Norah’s entire sail.

He sat in Henry’s study, flipping through ledgers with thin fingers, lips pursed.

“You are stable,” he said at last.

“But only just.

Any shock.

A bad harvest, a sick mule, a ruined gin belt.

And these numbers tumble the wrong way.

I need time.

Henry said, “You’ve had your interest.

You’ve had your principle when I could spare it.

You’ve had my sleep in my stomach lining.

How much more you want?” Haway regarded him as one might regard a mule complaining about its harness.

The bank wants security, he said.

“We are carrying several distressed notes.

The board is concerned.

” It would ease their minds if you were to designate a small portion of your movable property as additional collateral.

Henry’s jaw tightened.

Meaning meaning Hathaway said, “We note certain slaves in the security agreement.

They remain in your possession as long as you pay, of course, but if things sour, the bank has first claim.

” The word collateral had become a kind of curse in the county.

Men spoke it in low tones over whiskey, like they might ward it off by naming it.

Henry had heard enough stories to know what it really meant.

When the numbers went bad, human bodies were the first to be turned into silver.

I’ve already pledged land, he protested.

Land is slow to sell, Hatheraway said.

And the board is nervous.

A handful of younger slaves of good breeding and potential would go a long way toward reassuring them.

Henry’s eyes flicked almost involuntarily toward the window.

Through the glass, he could see the sideyard where Norah was hanging up damp laundry, arms stretching the sheet, face set in concentration.

Haway followed his gaze.

“That girl, for instance,” he said casually.

“Healthy, tractable, raised in the house.

In a few years, her uses will multiply.

” Henry stiffened.

“She’s new,” he said.

“Barely settled.

” All the better,” Hathaway replied.

“Less entangled, no long-standing attachments.

” The phrase stung more than it should have.

Henry thought of nights he’d watched Norah move through the house and felt, he told himself.

“Nothing more than a master’s assessment of stock.

She cost me 19 cents,” he said gruffly.

“All the more reason to list her.

” Haway said, “You lose almost nothing if we ever have to seize.

The bank, on the other hand, gains a valuable asset to auction.

” The words made a kind of brutal sense.

Henry’s debts were more than 19 cents.

The girl had been an impulse purchase, a joke.

Why not make her earn her keep on paper? Put her down then, he said, the words landing heavier than he expected.

Nora, age 10, 11, house trained.

Hathaway smiled thinly.

He opened his briefcase, took out a fresh page, and wrote her name in careful script.

“You have others in that age range,” he asked.

From the doorway, someone cleared a throat.

“Margaret.

” “I think that’ll be all for now,” she said.

Haway stood plastering on his polished smile.

Mrs.

Caldwell, he said, always a pleasure.

She didn’t return it.

Your pleasure costs us dearly, she said.

I hope the bank sleeps well.

The bank does not sleep.

Haway said he meant it as a joke.

It didn’t land.

After he left, the house felt like it had been dipped in something sour.

Henry stalked from room to room, uttering about interference and wives who didn’t understand business.

Margaret waited until he had exhausted himself.

Then she went to find Nora.

She found the girl in the yard staring at the sky as if trying to gauge whether the clouds meant rain or just more of the same heat.

Come inside, Margaret said.

We need to talk.

Norah’s shoulders tensed.

I done something wrong, ma’am.

You were in the wrong man’s gaze at the wrong time.

Margaret said, “That’s enough.

” In the parlor, she sat the girl down and explained as gently as a person can explain something that isn’t gentle at all.

What the word collateral meant.

It’s like being put on a list, Norah asked slowly.

Yes, Margaret said.

A list the sheriff might come for if the numbers don’t behave.

Norah’s hand went to her wrist, fingers rubbing the cloth there.

I already been on too many lists, she whispered.

I know, Margaret said.

And she did.

More than Norah could understand.

Can he do that? Norah asked.

put me on some paper at the bank like I’m a sack of seed.

He can, Margaret said.

He has, Norah’s jaw clenched.

Then what’s the point of this? She demanded, tapping the ribbon.

Mama said this would keep me from getting lost.

It kept you, Margaret said softly.

Until now.

It brought you as close to where you started as this world allows.

Norah’s eyes flashed.

You mean here? she said.

To you.

Margaret hesitated, then nodded.

Yes, she said.

To me, to us.

Then what you going to do about it? Norah asked.

The question would have gotten her whipped in most houses.

Here, it just hung in the air between them.

Wild and honest.

Margaret thought of her father’s letter, of the way he spoke of necessary corrections and family standing.

She thought of Henry’s irritated shrug when he’d agreed to list Nora, as if adding a 10-year-old to the slaughter line were no more serious than selling a goat.

“I’m going to do what my father did,” she said slowly.

“Only in reverse.

” She went to her desk and took out the household ledger again.

On the page where she kept track of shoes and soap, she wrote, “Blue cloth band to be replaced with plain twine.

Initials MB removed.

” “You cut it off?” Norah asked, stumbling back, hand clutching her wrist protectively.

“No,” Margaret said.

You keep it, but you don’t wear it where men like Haway can see.

You sew it inside your dress, inside your pocket.

Somewhere it stays yours.

Norah relaxed a fraction.

That all? She asked.

No, Margaret said.

I’m also going to move you where? To the laundry house? Margaret said you’ll sleep with the women there.

On paper, you’ll be listed as assigned to field support.

If Mr.

Hathaway ever sends a man to count the assets he’s claimed, they’ll be looking for a house girl named Nora.

I’ll make sure they don’t find one.

Norah frowned.

You can do that.

I am the mistress of this house, Margaret said.

A steely pride in the words that had nothing to do with her husband.

I know where everybody sleeps and every book is kept.

Men like Hathaway think that means I’m good at arranging flowers for their desks.

They forget it also means I can misplace things they think they own.

That night under cover of darkness and the usual creeks of old wood, the Caldwell household performed its own quiet rebellion.

Hester sat in the laundry room with a candle, carefully unpicking the stitches on Norah’s ribbon.

“Hold still,” she murmured.

“We don’t want to tear it now.

It’s done its job too long to be thrown aside careless.

” When the cloth was free, she watched as Norah tucked it into the lining of her dress, stitching it in place with small, stubborn bites of thread.

Now, Hester said, “Even if they strip you bare on some block, only you and whoever undresses you will know it’s there.

That’s your history.

” You guard it quiet.

Back in the big house, Margaret opened Henry’s account book.

She found the line where Hathaway had written, “Nora, female child, collateral.

” With a steady hand, she copied it into another book, one she kept for herself, tracking not money, but risk.

Beside Norah’s name, she wrote to be hidden when collection comes.

Two months later, the first real test came.

A drought chewed at the fields.

Yields dipped.

The numbers in Hatheraway’s ledger did what numbers always did when rain failed.

They betrayed the people who depended on them.

A letter arrived, formal and cold.

In light of your continued vulnerability, the bank will be sending an agent to inspect the collateral listed under your note.

Henry cursed for an hour straight.

Margaret felt the blow land lower in the place where worry lived.

The agent came on a bright, pitiles morning.

He wore the same kind of coat as Haway, carried the same kind of notebook.

He walked the rows, counted the hands, made marks only he could interpret.

“And the girl?” he asked eventually, consulting his list.

“House servant, age 10, Nora, listed as collateral A.

” Henry waved vaguely toward the house.

“Inside, I reckon,” he said.

“Ask my wife.

She keeps track of the house stock.

The man approached the back door.

Hester met him with a stiff spine and flower on her hands.

Neither girl called Nora, he said.

House servant.

Haway’s list.

Hester wiped her palms on her apron, stalling for time.

We got more than one girl around that age, she said.

Maybe mistress can sort you.

Margaret appeared before he could insist on barging in.

“Is there a problem?” she asked.

“Just confirming collateral, ma’am?” the man said.

The bank notes a house girl named Nora.

10 11 should be in service here.

Margaret’s face arranged itself into polite confusion.

“You must have old information,” she said.

We have a girl by that name, but she’s only just come up from the quarters.

Too small for housework yet.

Hester.

Hester caught the cue.

That’s right, ma’am.

She said, “Are Nora’s barely worth a broom? Surely Mr.

Hathaway meant one of Mr.

Caldwell’s older girls.

Millisent maybe.

Or Rose.

They’ve been in the house for years.

” The agent frowned, checked his paper.

It says recent purchase juvenile suitable for domestic training.

Are you telling me this Nora is not such? I’m telling you, Margaret said smoothly, that if the bank wants to secure its interests, it would be wiser to look at the young men in the fields.

They are strong, proven, and far more easily liquidated without disrupting my household.

The cruelty in the suggestion tasted like ash, but she knew how men like him thought.

Property meant bales and backs, not girls with blue cloth sewn inside their dresses.

The agent hesitated.

The sun was hot.

The day was long.

The bank didn’t pay extra for arguing with respectable white women about one child when there were rows of hands available to be converted into numbers.

Very well, he said finally.

We’ll amend the list.

His pencil scratched.

Somewhere on a page in his book, Nora collateral disappeared, replaced by other names.

Men whose faces Margaret did not let herself picture too clearly.

She would pay for that choice and other sleepless nights.

When he left, Hathaway’s agent believed he had tightened the bank’s hold.

Henry believed he had escaped worse outcome.

Only three people understood what had really happened.

Hester, who had seen one girl sold away already, and refused to watch another go without a fight.

Margaret, who had spent a lifetime arranging lives to suit men’s ledgers and had finally for once arranged one around hers, and Nora, who still slept in the laundry house, ribbon against her skin, and counted each morning she woke on the same land as a small victory, against all the lists that had promised otherwise.

Years later, when people in the county spoke of the Caldwell place, they remembered the drought, the near foreclosure, the way Henry Caldwell somehow kept the bank from taking everything.

Some said he’d charmed Hathaway.

Others claimed his wife’s family money had quietly stepped in.

No one mentioned a 10-year-old girl bought for 19 cents, almost lost again in the equations.

No one wrote down that the plantation master, who thought he’d scored a cheap piece of property, had actually brought home his wife’s hidden kin.

But in the quarters, in whispers passed from mother to daughter, the story stayed sharp.

He bought her for less than a cup of coffee, they’d say, and never knew he’d paid for the right to sit at table with his own wife’s blood.

And somewhere in an old trunk under dresses that smelled faintly of sea air and regret, there was another scrap of cloth once tied to a different baby’s wrist.

It bore the same letters.

MB.

The first one had been sent away.

The second one had come back.

Not even 19 cents could keep blood from finding its way

News

Ilhan Omar ‘PLANS TO FLEE’…. as FBI Questions $30 MILLION NET WORTH

So, while Bavino is cracking down in Minnesota, House Republicans turning the heat up on Ilhan Omar. They want to…

FBI & ICE Raid Walz & Mayor’s Properties In Minnesota LINKED To Somali Fentanyl Network

IC and the FBI move on Minnesota, touching the offices of Governor Tim Walls and the state’s biggest mayors as…

FBI RAIDS Massive LA Taxi Empire – You Won’t Believe What They Found Inside!

On a Tuesday morning, the dispatch radios in hundreds of Los Angeles taxi cabs suddenly stopped playing route assignments. Instead,…

Brandon Frugal Finally Revealed What Forced Production to Halt in Season 7 of Skinwalker Ranch….

The Secret of Skinwalker Ranch became History Channel’s biggest hit. Six successful seasons documenting the unknown with real science and…

1 MINUTE AGO: What FBI Found In Hulk Hogan’s Mansion Will Leave You Shocked….

The FBI didn’t plan to walk into a media firestorm, but the moment agents stepped into Hulk Hogan’s Clearwater mansion,…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage… It started like any other evening…

End of content

No more pages to load