The Plantation Owner’s Wife Who Eloped With a Runaway Slave: Louisiana’s Vanished Bride of 1847

It began with a simple notice in the St.Charles Herald on April 14th, 1847.

A small column nestled between advertisements for cotton gins and medicinal tonics read, “Missing Mrs.Evelyn Duval, wife of plantation owner Gerard Duval, last seen on the evening of April 10th.

Reward offered for information leading to her safe return.

What seemed at first to be a routine disappearance would unravel into one of Louisiana’s most disturbing cases.

one that official records would later scrub clean, but whose echoes still resonate through the cypress swamps of St.

James Parish.

The Duval plantation stood proud along the Mississippi River, a two-story white mansion with 12 imposing columns stretching across its facade.

On the surface, it represented everything the antibbellum South celebrated, wealth, stability, and a rigid social order.

According to parish records, Gerard Duval had acquired the plantation in 1839 following the death of his father.

The ledgers from the First Bank of New Orleans show he had expanded the property considerably, purchasing adjoining land and increasing his workforce to over 100 enslaved persons by 1845.

Eveine had arrived from Charleston in 1844, the daughter of a wealthy shipping merchant who had arranged the marriage to strengthen business connections.

The couple’s wedding announcement in the New Orleans Pick a Yune described her as a woman of extraordinary beauty and refined accomplishment, certain to grace Louisiana society with her presence.

Surviving letters from Evelyn to her cousin in Virginia discovered in a family collection in 1952 paint a different picture.

The air here suffocates, she wrote 3 months after her arrival.

The house feels like a museum where I’m both exhibit and visitor.

Parish records indicate that Henry Carter had been purchased at the New Orleans slave market in January of 1846.

His bill of sale, later recovered from the Duval estate papers during an academic survey in 1964, listed him as male, approximately 26 years of age, literate, skilled in carpentry, of sound body and temperament.

A rare notation at the bottom, presumably in Gerard Duval’s handwriting, specified to serve in house and manage library organization.

What followed was a period of apparent calm.

The plantation’s accounting books from 1846 show increasing profits from sugar cane production.

Gerard Duval’s name appears frequently in parish meeting minutes where he advocated for stricter controls on the movement of enslaved people between plantations.

A journal belonging to Margaret Fontaine, wife of a neighboring plantation owner, mentions Evelyn at various social gatherings, describing her as quiet to the point of invisibility, though her eyes seemed to take in everything.

The journal entry from Christmas of 1846 notes that Mrs.

Duval seemed unusually distracted during the sermon and excused herself before the meal was served.

The winter of 1846 gave way to spring, and with it came the first disruptions to the plantation’s carefully maintained order.

A ledger entry from March 3rd notes disciplinary action required for Henry Cound in Mistress’s private sitting room without permission.

A subsequent entry from March 21st indicates HC reassigned to field duties as punishment.

Yet a curious counter entry dated March 28th returns him to household duties with the notation, “At mistress’s insistence, HC returned to library management.

” On April 10th, 1847, multiple events converged.

According to the overseer’s daily report, Gerard Duval departed for New Orleans on business, expected to return in three days.

The weather journal kept by the plantation manager noted heavy rains beginning at sunset, continuing through night.

The last documented sighting of Eiveline was by the cook, who later told investigators she had requested tea be brought to the library at approximately 8:00 in the evening.

By morning, both Evelyn Duval and Henry Carter were gone.

What followed was a search unprecedented in its scale for St.

James Parish.

Gerard Duval returned from New Orleans and immediately organized search parties that combed the surrounding swamps and checked every road leading away from the plantation.

The New Orleans Daily Crescent reported on April 17th that 50 men with dogs traversed the wilderness in search of Mrs.

Duval, who is feared to have been abducted by a runaway slave.

Notices were posted as far north as Nachez and as far east as Mobile.

The official narrative quickly solidified around abduction.

Respected planters wife taken by slave, read the headline in the Baton Rouge Gazette on April 21st.

The article quoted Gerard Duval claiming that Henry had shown signs of instability and had developed an unhealthy fixation on Mrs.

Duval due to their shared interest in literature.

A reward notice published in multiple southern newspapers offered $1,000 for the return of Mrs.

Evelyn Duval and the capture, dead or alive, of the negro man Henry, who has taken her against her will.

Yet contradictions emerged almost immediately.

A statement given to parish authorities by Rachel, an enslaved woman who served as Evelyn’s lady’s maid, noted that mistress had been packing a small val for several days, adding items gradually so as not to draw attention.

This statement was stricken from official records, but preserved in the private notes of Sheriff Thomas Wilkinson, discovered among his effects after his death in 1861.

More tellingly, an inventory conducted of Evelyn’s belongings, revealed the absence of not only clothes and personal items, but also of several books from the library, including copies of Voltater and Rouso, that parish records show had been ordered from New Orleans the previous autumn.

Gerard Duval insisted these items had been taken by Henry as further evidence of his crime.

As the search extended into its second week, a riverboat captain reported seeing a white woman and a negro man boarding his vessel at a small landing 10 mi down river from the Duval plantation on the morning of April 11th.

According to his statement, they had purchased passage to New Orleans, where they disembarked and disappeared into the city.

When questioned about their behavior, the captain reported that they spoke little, but sat closely together, and the woman wore a dark veil throughout the journey.

When asked directly if the woman appeared to be under duress, the captain’s response was reportedly, “No more than any woman traveling with a man.

The trail went cold in New Orleans.

” Despite extensive searches of the city, particularly in areas known for harboring runaways and free people of color, no further confirmed sightings emerged.

A rumor circulated that they had boarded a vessel bound for Haiti, but shipping records from the period show no passengers matching their descriptions.

As weeks stretched into months, the public narrative began to shift.

The Pika Yune published an article in June suggesting that sources close to the Duval household indicate the marriage had been troubled from its inception and hinting at cruel treatment that may have driven Evelyn to flee.

Gerard Duval responded with threats of legal action and subsequent coverage retreated to the abduction narrative.

By autumn, the case had largely disappeared from public discussion.

Gerard Duval sold the plantation in December of 1847 and returned to France where his family had roots.

Parish records show he cited unhappy memories as his reason for departure.

The plantation house itself burned to the ground in 1849, attributed to a lightning strike.

Local rumors suggested arson, though no investigation was ever conducted.

The case might have remained buried in obscurity had it not been for the discovery of a curious document in 1958.

During renovation of an old townhouse in the French Quarter, workers found a sealed tin box hidden within a wall cavity.

Inside was a journal, water damaged but partially legible, bearing the inscription property of Ed.

The journal was turned over to Tulain University historians who dated it to the mid-9th century based on the paper composition and ink analysis.

Only fragments of the journal remain readable, but they paint a startling picture at odds with the official record.

One entry presumed to date from early 1846 reads, “G treats his books with more tenderness than he has ever shown me.

The new man H understands their value as well and speaks of authors I had not expected anyone here to know.

A later entry continues.

H and I discussed Rouso today when G was occupied with the mill machinery.

He has learned through paths I cannot imagine acquiring knowledge despite every barrier erected against it.

By winter of 1846 the tone shifts.

The way G looks at H when he thinks I do not notice with suspicion with malice I fear what may come.

And later G struck me today when I protested H’s reassignment to the fields.

Said I had become too familiar with the slaves.

If only he knew the thoughts that now occupy my mind.

The final legible entry undated but presumably from early April 1847 is the most revealing.

We have agreed.

When G goes to New Orleans, the riverboat at dawn, H says there are people in the city who can help us reach Philadelphia.

I take only what cannot be replaced.

My heart races with fear and something else.

Perhaps the first true hope I have felt since coming to this dreadful place.

The journal’s discovery sparked renewed interest in the case among historians specializing in antibbellum southern society.

A 1962 article in the Journal of Southern History suggested the Duval case represented a rarely documented instance of voluntary escape across racial boundaries, though this interpretation remained controversial.

In 1964, research conducted in Philadelphia City archives uncovered a marriage certificate dated October 3rd, 1847 between an Ellen Davis and Harold Carter.

The certificate noted both parties were free colored persons, a common designation used by light-skinned black individuals or interracial couples attempting to establish lives in northern cities.

The officiating minister’s private records preserved by his church included a cryptic note.

The woman speaks with a southern accent despite claiming Charleston birth.

Husband protective watches door throughout ceremony.

Fear evident.

Tax records show that Harold Carter established a small carpentry business in Philadelphia’s Seventh Ward, an area known for its free black community.

The business operated until 1853 when city directories indicate the Carters relocated possibly to Canada following the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act.

No further official records of the couple have been found.

In 1857, a brief item appeared in the New Orleans papers reporting the death of Gerard Duval in Paris.

The notice mentioned that he died without heirs, his property in France passing to distant relatives.

A single line at the end noted that he had never remarried following the tragic loss of his wife.

The most disturbing evidence in the case emerged in 1966 when an archaeological survey of the former Duval plantation site uncovered the remains of a root cellar beneath what had been the main house.

Among the charred debris were found three small items.

A woman’s pearl hair comb matching the style of the 1840s.

A carpenters’s measuring tool with the initials HC scratched into the handle.

and most tellingly, fragments of a letter addressed to my dearest E that appears to have been concealed in the cellar wall.

The letter fragments analyzed by paper conservators at Louisiana State University contain several disturbing lines.

Cannot delay any longer, he suspects, and said today he would sooner see you dead than the letter’s date is partially preserved.

April 7th, 184, just days before the disappearance.

What truly happened at the Duval plantation in April of 1847? The historical record offers tantalizing but incomplete answers.

Parish death records show no entry for Evelyn Duval, nor any report of human remains discovered in the aftermath of the disappearance.

If Gerard Duval harbored knowledge of his wife’s fate beyond what he publicly claimed, he carried it with him to his grave in Paris.

Local folklore filled the gaps in the official record into the early 20th century residents of Satint.

James Parish told stories of a well-dressed white woman and a black man in fine clothes who could sometimes be glimpsed at dusk walking along the river path near where the Duval plantation once stood.

The apparitions never spoke, according to these accounts, but always walked hand in hand, looking backward over their shoulders as if pursued by something only they could see.

In 1968, the last living person who claimed direct knowledge of the case, passed away.

Martha Johnson, aged 102, had been born into slavery on a neighboring plantation.

In an oral history recorded by two-lane university researchers in 1963, she claimed her grandmother had been a kitchen worker at the Duval plantation.

According to Johnson, her grandmother had always maintained that Miss Eiveene and Henry had been planning for months.

They had a system of notes hidden in book bindings.

The master found one, and that’s when things turned dangerous.

When asked what she believed had happened, Johnson’s response was recorded as, “My grandmother said there were two stories.

The one people told about them running away together, and the other one, the one the house slaves whispered about that the master caught them before they could leave, and they’re still there under the old house foundation.

” But nobody could ever prove either tale.

The Duval plantation site remained abandoned until 1973 when the land was purchased for industrial development.

Workers clearing the overgrown property reported unusual occurrences.

Tools disappearing, unexplained cold spots, and a persistent smell of smoke in the area where the house had stood, though no fires had burned there in over a century.

The development ultimately failed with the company citing environmental concerns in their public statements, though former employees later spoke of executives refusing to visit the site after experiencing what they described as a profound and inexplicable sense of dread.

Today, the former Duval plantation is part of a wildlife management area, accessible only by boat through the swamps that have reclaimed the once cultivated fields.

Occasional visitors report hearing whispered conversations carried on the wind, though no other people are present.

Park rangers dismiss these stories as the natural sounds of the wetlands combined with the power of suggestion from those familiar with the legend.

In 2008, a history professor from LSU attempting to locate the precise site of the original house foundation reported finding a rusted metal box partially exposed by seasonal flooding.

Inside was a small leatherbound volume, its pages mostly rendered illeible by water damage.

The few decipherable fragments include a passage that reads, “If we are not discovered, this journal will remain hidden, and we shall begin new lives under new names in a place where we might exist together.

If the worst occurs and we are separated by death or capture, perhaps someday someone will find these words and know that what existed between us was not what they said.

Not a crime or an abduction, but the only freedom either of us had ever truly known.

The professor suffered a stroke while still in the field and was unable to document the exact location of his find.

When a research team returned to the site, the box could not be relocated.

The professor’s field notes were deemed unreliable due to his medical condition, and academic interest in the case once again waned.

In the parish courthouse, the official record of the Duval case remains filed under unresolved crimes abduction, a thin folder containing yellowed newspaper clippings and the original missing person report.

The alternative narrative of an unlikely alliance, a desperate escape, or possibly a concealed murder, exists only in fragments scattered through university archives, folklore collections, and the whispered stories still occasionally told by the oldest families in St.

James Parish.

The true fate of Evelyn Duval and Henry Carter remains unknown.

Whether they found freedom together in the north, met a violent end at the hands of a jealous husband, or exist now only as troubled spirits along the Mississippi, their story continues to echo through the heavy Louisiana air.

A reminder of a time when crossing the boundaries of race meant risking everything, when the lines between captor and captive, victim and perpetrator, love and possession blurred in the shadow of the plantation house.

For those who have ventured to the overgrown site where the Duval mansion once stood, there remains a strange quality to the silence that hangs over the clearing.

It is not the peaceful quiet of abandoned places, but something expectant, as if the cypress trees and tall grass are holding their breath, waiting for a story to finally reach its proper conclusion.

But like so many dark chapters in our history, perhaps some conclusions are deliberately hidden, some stories intentionally left unfinished, their final pages scattered to prevent us from ever knowing the whole truth.

And perhaps in this case, that uncertainty is itself a fitting memorial to a woman who vanished from history’s pages as completely as she disappeared from that rain soaked plantation on an April night in 1847, and to a man who history recorded only as property, yet who may have found a way to write his own ending.

After all, in 1979, a graduate student in anthropology conducted interviews with elderly residents of St.

James Parish for a thesis on oral history traditions.

One interviewee, William Tibido, then 87 years old, provided an account passed down through his family.

According to Tibido, his grandfather had been part of the search party organized after Evelyn’s disappearance.

Granddaddy said they weren’t really looking for Mrs.

Duval at all.

His recorded interview states, “Mr.

Duval knew exactly where she was.

They were hunting Henry, plain and simple.

When pressed for details, Tibido shared a disturbing alternative narrative.

The story my granddaddy told, which I ain’t supposed to repeat, was that Mrs.

Duval had been caught trying to leave.

Mr.

Duval locked her in the cellar room for 3 days.

Henry tried to help her escape again, and that’s when things turned bad.

The search parties weren’t looking for two runaways.

They were covering up what Mr.

Duval had done.

This account found partial corroboration in 1848 correspondence between the parish sheriff and the governor’s office uncovered during a 1962 state archive reorganization.

The letter marked confidential references the regrettable Duval situation and suggests that certain influential parties believe the matter is best left closed given Mr.

Duval’s departure from the state and the impossible complications that would arise from further investigation.

A series of surveys conducted in the 1980s using early ground penetrating radar technology detected anomalies beneath the former house site that experts identified as consistent with a root cellar or similar substructure, but no excavation was ever permitted.

The land had changed ownership multiple times and the current owners denied access for archaeological investigation, citing concerns about disturbing historical remains.

In 1983, renovations to an old church in Philadelphia’s Northern Liberty’s neighborhood revealed a hidden compartment beneath the pulpit containing various documents related to the Underground Railroad.

Among them was a list of individuals who had passed through the church’s sanctuary between 1847 and 1851.

An entry dated November 1847 mentions Ed and HC from Louisiana provided with papers and funds for passage to Canada.

Woman ill recovering from injuries both traumatized but determined.

This document reignited interest in the possibility that Evelyn and Henry had indeed escaped north.

However, extensive searches of Canadian census records and community archives in likely destination cities like Toronto and Montreal yielded no conclusive evidence of their settlement there under either their original names or known aliases.

The mystery deepened in 1991 when a descendant of Gerard Duval’s French relatives discovered a locked journal among family heirlooms in Paris.

The journal written in French and dating from 1848 to 1857 contains several entries referencing Eveene.

In one particularly revealing passage from 1851, Gerard writes, “I received word today that they believe she has been seen in Montreal.

I will not pursue.

Let the dead bury their dead.

What was taken from me cannot be restored, and I have sworn to forget that name and face.

” A later entry dated just weeks before his death in 1857 reads more ambiguously.

I dreamt of Louisiana again.

The house in flames, her voice calling from below.

I wake each night at 3:00, the hour when we found the cellar door open.

Some sins cannot be escaped, even an ocean away.

I feel her presence growing stronger as my own strength fails.

These entries have been interpreted variously by historians.

Some seeing evidence that Eveine had survived and escaped to Canada, others reading a confession of murder between the lines, with Gerard’s guilt manifesting as nightmares and paranoia in his final years.

In 2002, a hydraological survey of the Mississippi River basin produced unexpected evidence related to the case.

Soil core samples taken near the former plantation site contained traces of accelerance consistent with deliberate burning contradicting the official record that the house fire in 1849 had been caused by lightning.

More disturbing were traces of human remains detected in deeper layers of the soil, though the fragmentaryary nature of the evidence made it impossible to determine age, gender, or number of individuals.

When this information became public, descendants of families from the surrounding plantations came forward with stories that had been passed down through generations.

Three separate accounts mentioned that in the weeks following Everline’s disappearance, enslaved workers from neighboring properties had been conscripted to dig at night on Duval land.

One account specifically mentioned activity around the house foundation and cellar.

These workers reportedly never spoke of what they had seen or done there, except in the most oblique terms, even decades after emancipation.

A journal entry from 1865, written by a Union officer stationed in the parish during reconstruction notes, “The locals, both white and colored, share a strange reluctance to discuss the ruins of the D plantation.

When pressed, an elderly negro man told me only that some ground won’t grow crops proper when it’s been fed with the wrong kind of seed.

The meaning of this cryptic statement remains unclear, though the land in question has indeed lain since the war began.

In 2005, the Louisiana Historical Society commissioned a comprehensive review of all available evidence in the case, bringing together historians, archaeologists, and forensic experts.

Their 300page report published in 2007 concluded that while no single definitive narrative can be established, the preponderance of evidence suggests that Eveine Duval and Henry Carter likely perished on or near the plantation property in April 1847, possibly at the hands of Gerard Duval or his agents, with their remains concealed to prevent discovery.

The report was not without its critics.

A minority opinion included in the appendix argued that the documentary evidence from Philadelphia and Montreal, while circumstantial, offered a plausible case for their successful escape.

This interpretation has been embraced by several historical novels and a 2010 documentary film titled The Runaways of St.

James Parish, which presents a romanticized version of Ealine and Henry finding freedom and building new lives in Canada.

The most recent development in the case came in 2013 when ground penetrating radar technology, far more advanced than that used in the 1980s, was finally permitted on the site.

The survey revealed a previously undetected structure approximately 30 yards from the main house foundation, possibly a small outbuilding or storage cellar not documented in the original plantation records.

Before excavation could begin, however, unprecedented flooding along the Mississippi inundated the site, and when waters receded months later, the geological features had been so altered that the anomaly could no longer be located.

To this day, visitors to the wildlife management area report unsettling experiences near the former plantation site.

Park rangers have documented dozens of accounts describing a sudden drop in temperature, the sound of a woman weeping, or glimpses of two figures moving quickly through the underbrush at dusk.

Scientific investigators attribute these reports to the power of suggestion combined with the natural sounds and shadows of the swamp environment.

Those familiar with the story, however, often interpret these phenomena as evidence that whatever happened on that rainy April night in 1847, something of Eveine and Henry remains bound to the land, either as victims seeking justice or as spirits unable to complete their escape.

The Parish Historical Society maintains a small exhibition on the case, presenting both the abduction and escape narratives side by side without endorsing either conclusion.

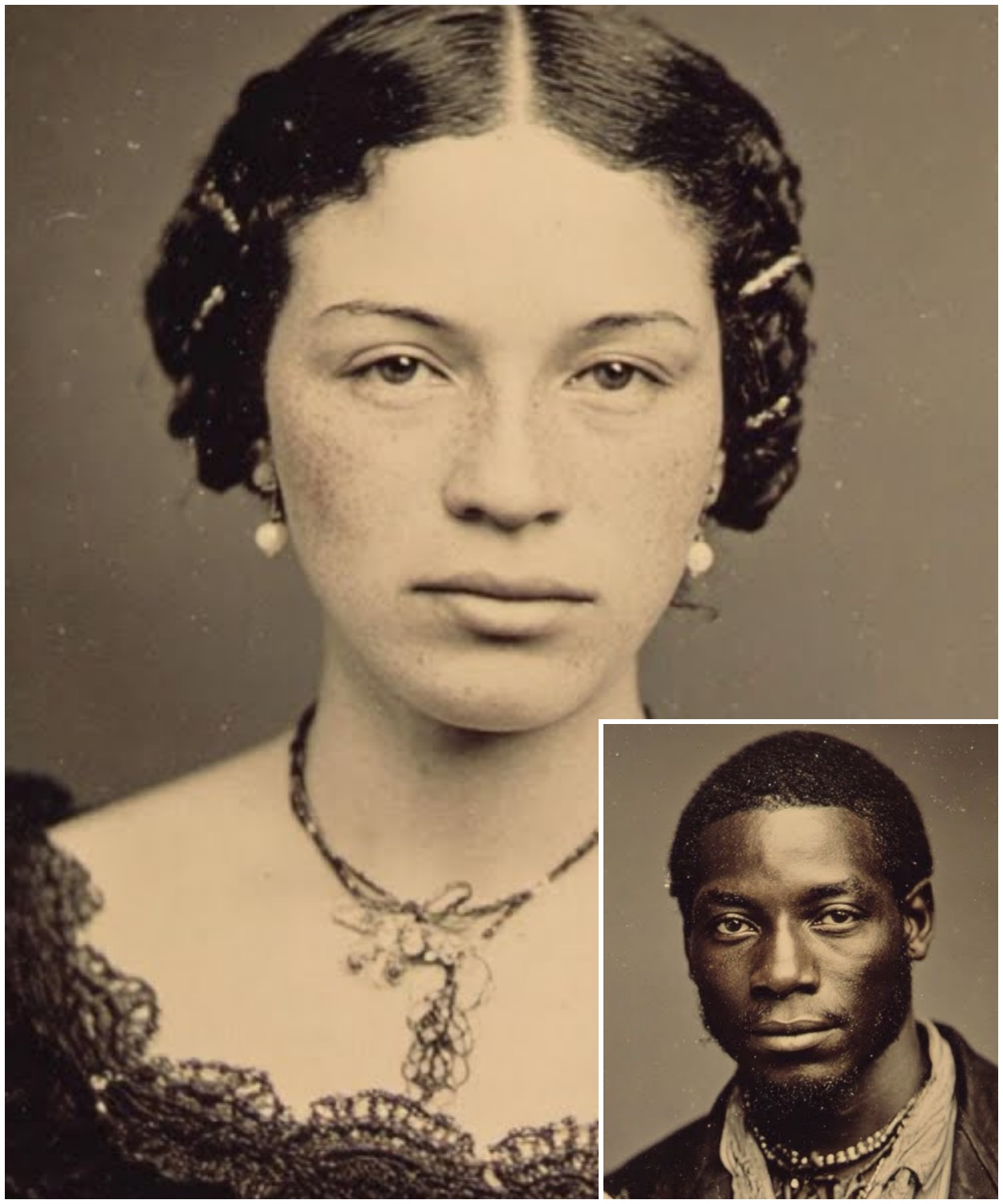

The display includes a reproduction of Evelyn’s portrait from the Duval family collection in France, showing a young woman with dark hair and a solemn expression, her eyes seeming to look beyond the painter towards something in the distance.

Beside it hangs a blank frame where Henry’s image would be had any survived.

A stark reminder of how completely enslaved individuals could be erased from historical record.

Their stories left to be pieced together from fragments and omissions.

In 2018, a historical fiction author researching the case discovered a curious document in the archives of a small museum in Montreal dated 1862.

It appears to be a death certificate for an Ellen Carter Nay Davis listing her age as approximately 40 years and her place of birth as southern United States.

The certificate notes she was survived by her husband Harold and two children.

Attempts to trace these descendants have thus far proven unsuccessful as the family name is common and records from the period incomplete.

What makes this document particularly intriguing is a notation in the margin apparently added by the attending physician.

Patient expressed desire before passing that certain items be preserved for historical record include journal and pearl comb.

Husband adamant these remain private.

Respected his wishes as promised to deceased.

No such items have ever surfaced in Canadian archives.

Did Evelyn and Henry escape to build new lives together, carrying their secrets to their graves? Did they perish at the Duval plantation, victims of the violent social order they had attempted to defy? Or does the truth lie somewhere in between these narratives? Perhaps an initial escape followed by capture and return, or one escaping while the other perished.

The case remains officially unsolved.

The St.

James Parish Sheriff’s Department technically maintains an open file on the disappearance of Evelyn Duval, though no active investigation has been conducted in over a century.

In the Louisiana State Archives, her case number is cross-referenced with that of Henry Carter, one of the few official acknowledgments that their fates, whatever they may have been, were inextricably linked.

Historians of the Antibbellum South note that the Duval case, while unusually well documented, likely represents countless similar stories lost to history of boundaries crossed, attempts at freedom thwarted or achieved, and lives erased from official records.

In the words of Dr.

Elaine Montgomery, author of Silenced Histories, Race and Gender in the Antibbellum South, the story of Eiveene and Henry exists in the liinal space between documented history and folklore, between what could be proven and what was known but never written, between the official narrative that maintained social order and the whispered truths that subverted it.

Perhaps the most poignant interpretation comes from a poem published anonymously in a Montreal literary journal in 1870 titled simply E and H.

While no direct connection to Eveine and Henry can be established.

The final stanza reads, “Two souls who fled across the line where freedom meets with fear, their names erased, their paths concealed, their whispers still we hear.

Not ghost, nor flesh, but memory, too stubborn to depart.

The truth lies buried not in earth, but in the human heart.

On moonless nights, when the Louisiana air hangs heavy with moisture, and the cypress trees stand like sentinels along the swamp’s edge, locals say the old plantation ground still holds its secrets close.

Some claim to hear whispers exchanged between two voices, one with the refined accent of Charleston society, the other with the measured cadence of a man who taught himself to read despite laws forbidding it.

Whether these are the restless spirits of starcrossed lovers murdered for defying the boundaries of their time, the psychic echoes of a desperate escape into history’s shadows, or simply the wind through the Spanish moss, perhaps matters less than the story itself, and what it continues to reveal about a nation still reckoning with the long shadows of its past.

In 2021, on the 174th anniversary of the disappearance, a small marker was placed near the presumed site of the Duval plantation house.

It bears no names, dates, or definitive claims.

Only a simple inscription.

For those who sought freedom by whatever path was offered, their story continues.

The marker has become an unofficial pilgrimage site for historians, romantics, and the merely curious.

Visitors often report leaving with more questions than answers, but also with a deeper understanding of how completely the past can vanish when powerful interests wish it erased, and how persistently it can resurface through the unlikeliest channels.

a fragment of journal, a carpenter’s tool, a pearl comb, a whispered story, a name on a passenger list, a notation in a margin.

As for the final truth of what happened to Evelyn Duval and Henry Carter on that rainy night in April 1847, perhaps it is fitting that the mystery remains.

In its uncertainty lies the perfect reflection of a nation still struggling to reconcile its founding ideals with its historical realities, still unearthing stories deliberately buried, still listening for voices long silenced but never truly gone.

Some say that if you stand at the edge of what was once the Duval property on April 10th, as evening falls and the first drops of spring rain begin to fall, you can hear them still.

not calling out in fear or pain, but speaking in hushed, urgent tones of possibility, of escape, of a future reclaimed from those who would deny it.

Not ghosts, but something far more powerful.

A story that refuses to end where others decided it should.

A truth that continues to emerge fragment by fragment into the light.

News

Ilhan Omar ‘PLANS TO FLEE’…. as FBI Questions $30 MILLION NET WORTH

So, while Bavino is cracking down in Minnesota, House Republicans turning the heat up on Ilhan Omar. They want to…

FBI & ICE Raid Walz & Mayor’s Properties In Minnesota LINKED To Somali Fentanyl Network

IC and the FBI move on Minnesota, touching the offices of Governor Tim Walls and the state’s biggest mayors as…

FBI RAIDS Massive LA Taxi Empire – You Won’t Believe What They Found Inside!

On a Tuesday morning, the dispatch radios in hundreds of Los Angeles taxi cabs suddenly stopped playing route assignments. Instead,…

Brandon Frugal Finally Revealed What Forced Production to Halt in Season 7 of Skinwalker Ranch….

The Secret of Skinwalker Ranch became History Channel’s biggest hit. Six successful seasons documenting the unknown with real science and…

1 MINUTE AGO: What FBI Found In Hulk Hogan’s Mansion Will Leave You Shocked….

The FBI didn’t plan to walk into a media firestorm, but the moment agents stepped into Hulk Hogan’s Clearwater mansion,…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage… It started like any other evening…

End of content

No more pages to load