The Georgia summer of 1851 pressed down on Thornhill Plantation like a fever that wouldn’t break.

The air hung thick and wet, clinging to skin, filling lungs with moisture that felt more like drowning than breathing.

In the fields, cotton plants stood in endless rows, their white bowls ready for picking under a sun that showed no mercy.

Elijah had worked those fields since he was 7 years old, now 26.

His hands were scarred maps of a life spent in bondage.

His back a testament to every perceived disobedience, every moment of exhaustion mistaken for laziness.

He was tall, lean from rationed meals, with eyes that had learned to hide everything he truly felt.

The overseer, Thomas Garrett, was a man who found pleasure in other men’s pain.

He carried his whip coiled at his belt like a snake waiting to strike.

And that morning he’d been drinking since dawn.

The other slaves had learned to move slower, quieter, to become nearly invisible when Garrett was in his cups.

But Elijah had been assigned to the barn to repair a wagon wheel alone, away from the protective anonymity of the field gang.

The barn smelled of hay, leather, and horse sweat.

Elijah worked methodically, his hands steady despite the heat.

He’d almost finished when Garrett’s shadow fell across the barn floor.

“Boy,” Garrett slurred.

“You working slow today.

” “No, sir.

Almost done, sir,” Elijah replied, eyes down, voice carefully neutral.

“Don’t you talk back to me.

” There was no winning this.

Elijah knew it with the certainty that comes from years of experience.

Silence was defiance.

Speech was insolence.

The whip was coming regardless.

The first lash caught him across the shoulders, then another, and another.

Elijah counted them silently.

Five, six, seven, until his vision began to blur.

The pain became something distant, a sensation happening to someone else’s body.

On the 15th lash, Elijah’s legs gave out.

He collapsed forward into the dirt, tasting blood in his mouth.

Garrett circled him, breathing hard from exertion and whiskey.

Get up, boy.

We ain’t done.

But Elijah couldn’t move.

His body had simply stopped obeying.

The world tilted, darkened at the edges.

He heard Garrett curse heard him stumble backward.

Hell, you better not be dying on me.

Master Thornhill don’t take kindly to damaged property.

The last thing Elijah heard before darkness claimed him completely was Garrett’s boots running across the barn floor and then nothing.

No sound, no light, no pain, just nothing.

Before we begin this journey into one of the American South’s darkest and most unspeakable stories, I need to ask you something.

Where are you watching from? Drop your location in the comments.

And if this is your first time on our channel, subscribe now because what you’re about to hear is a story that official history tried to bury, but memory refused to forget.

Dr.

Samuel Weathers arrived at Thornhill Plantation 2 hours after Garrett sent word.

He was a thin man with wire rimmed spectacles and the perpetually distracted air of someone who considered plantation medicine beneath his skills.

He’d been educated in Charleston, had once harbored dreams of practicing in a proper city hospital, but debts and whiskey had deposited him here, tending to livestock and slaves with equal disinterest.

Master Jonathan Thornnehill stood in the barn doorway, arms crossed, face flushed with barely contained anger.

He was a man in his 50s, prosperous from generations of inherited wealth and unpaid labor, who viewed disruption to his property with personal offense.

“Well,” Thornhill demanded, as Weathers knelt beside Elijah’s motionless form.

The doctor placed his fingers against Elijah’s neck, searching for a pulse.

Finding nothing, he lifted one of Elijah’s eyelids.

The eye beneath stared ahead, unseeing.

Weathers pressed his ear to Elijah’s chest, listening for the sound of breath or heartbeat.

Silence.

He’s gone, Weathers announced, standing and brushing dirt from his knees.

Heart likely gave out from the exertion and heat.

Happens sometimes with the weaker ones.

Garrett, standing in the corner, shifted nervously.

I didn’t hit him that hard.

Just correcting some laziness, that’s all.

Thornhill waved a dismissive hand.

Elijah was never particularly strong.

Always seemed sickly.

It was a lie, but a convenient one.

What’s the procedure, doctor? Bury him quickly given the heat.

Bodies deteriorate fast in this weather.

I’ll sign the death certificate.

Cause of death.

Heart failure brought on by natural weakness of constitution.

Weathers pulled a small flask from his coat pocket and took a long drink.

My fee is the usual.

Money changed hands.

Papers were signed.

Within the hour, word had spread through the slave quarters.

Elijah was dead.

Old Ruth, who’d helped birth Elijah and raised him after his mother died, wept quietly in her cabin.

Young Samuel, Elijah’s closest friend, stood motionless in the field, hoe in hand, staring at nothing.

The other slaves moved through their work like ghosts, each one thinking the same thought they’d thought a hundred times before.

It could have been me.

By evening, a simple pine coffin had been constructed.

Three slaves carried Elijah’s body from the barn, laid him inside, and nailed the lid shut.

No ceremony, no prayers said aloud.

Those were forbidden.

The masters feared religion among slaves, feared any gathering, any words that might kindle hope or solidarity.

The coffin was loaded onto a wagon.

Garrett, still nervous, volunteered to handle the burial himself.

I’ll take it to the far edge of the south field, he told Thornnehill, near where we buried the others.

But what Garrett didn’t mention was his plan to dig the grave as quickly and shallowly as possible, then spend the rest of the evening at the tavern in town, trying to drink away the image of Elijah’s unseeing eyes.

The southfield stretched out in darkness, bordered by a line of ancient oaks, whose branches formed twisted silhouettes against the evening sky.

This was where Thornhill Plantation buried its dead slaves, far from the family cemetery, with its marble headstones and carefully tended plots, far from anywhere the living had to think about them.

Garrett brought the wagon to a stop beneath the oaks, the coffin rattling in the back.

He’d brought a lantern and a shovel, and in his pocket, another flask of whiskey.

The moon was a thin crescent providing almost no light.

He chose a spot at random.

They were all the same anyway, and began to dig.

The earth was hard, packed down by the summer heat, and every shovel full took effort.

Sweat soaked through his shirt despite the cooling evening air.

After 20 minutes, Garrett stopped.

The hole was perhaps 3 ft deep, barely adequate, but he was drunk and tired, and wanted this done.

He told himself it was deep enough.

What did it matter? It was just another dead slave.

There’d be more.

He went to the wagon, grabbed one end of the coffin, and dragged it to the hole.

It fell in with a thud that sent dirt cascading down its sides.

Garrett immediately began shoveling earth on top, working faster now, eager to be finished.

He didn’t bother to fill the grave completely.

When the coffin was covered with perhaps 18 in of soil, he stopped, planted the shovel in the ground, and took a long drink from his flask.

“That’ll do,” he muttered to himself.

But as he turned to leave, something made him pause.

A sound so faint he almost missed it.

A scratching like fingernails on wood.

Garrett froze, listening.

Nothing.

Just the wind in the oak leaves.

He shook his head, laughing at himself.

Too much whiskey, he said aloud, his voice sounding small in the darkness.

He grabbed the lantern and the shovel, climbed onto the wagon, and drove away without looking back.

Behind him, the shallow grave lay silent under the stars, covered but not deeply, buried, but not beyond reach.

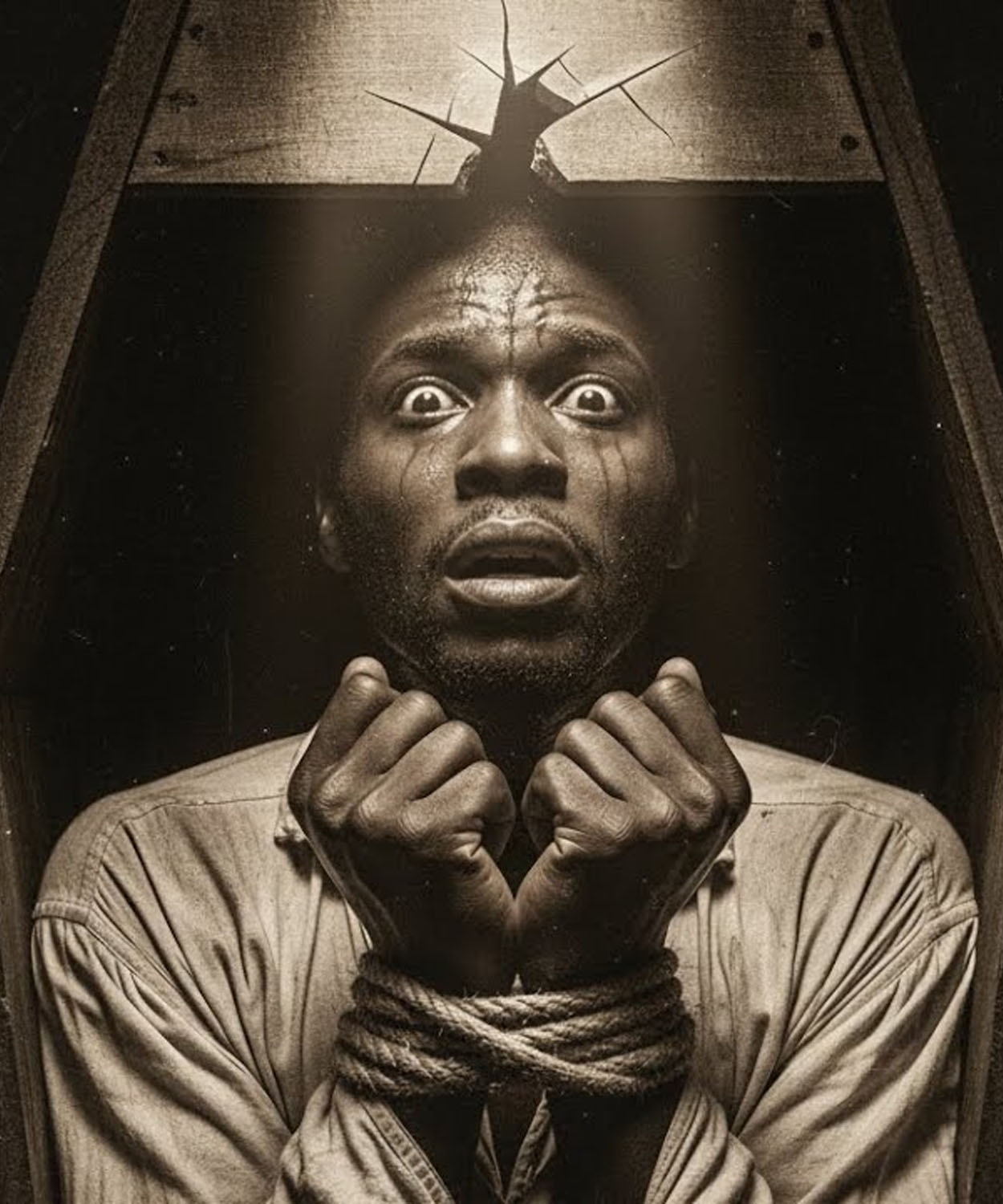

Inside the coffin, in absolute darkness, Elijah’s chest suddenly expanded with a desperate gasping breath.

His eyes flew open to complete blackness.

The first sensation was suffocation.

Not the gentle unconsciousness of sleep, but the violent panic- soaked realization that there was no air, no space, no light.

Elijah’s hands flew up and immediately struck wood inches from his face.

He tried to scream, but his throat was so dry that only a rasping croak emerged.

His entire body began to shake.

Primitive terror overwhelming thought.

He pushed against the coffin lid with all his strength, but it didn’t move.

His fingers scrabbled at the wood, finding no purchase, no weakness.

He was in a box, a closed box, underground, buried alive.

The realization crashed over him like ice water.

And for several moments, Elijah simply thrashed, consumed by animal panic.

His fists pounded against the lid, his legs kicked, his body twisted in the confined space.

Splinters drove into his palms.

His head struck the sides of the coffin.

None of it mattered.

He had to get out.

He had to get out.

He had to.

A sound stopped him.

Not his own sounds.

The gasping, the pounding, the desperate scraping.

Something else.

Movement in the coffin with him.

Elijah went completely still, his breath catching in his throat.

In the absolute darkness, he became aware of his body’s position.

He was lying on his back, arms bent at awkward angles, head tilted slightly to the left.

The space was so confined that he could feel the wooden walls on all sides.

But there was something else pressed against his right side, something warm.

No, not warm.

Body temperature like him.

He listened, trying to hear over the sound of his own thundering heartbeat.

And there it was again, breathing.

Shallow, rapid breathing that wasn’t his own.

Who? Elijah’s voice came out as a broken whisper.

Who’s there? No answer.

But the breathing continued, and now he felt it.

The slight rise and fall of a chest pressed against his ribs.

The warmth of another human body in the darkness.

His left hand, trembling, reached across his own chest toward the presence.

His fingers touched fabric first.

Rough cotton like his own clothes, then skin, an arm, a shoulder, a face.

Elijah’s fingers traced features in the darkness, a forehead slick with sweat, a nose, lips slightly parted.

The person was young.

He could tell from the size of the face, the smoothness of the skin.

“Who are you?” he whispered again.

This time there was a response.

A small terrified voice barely audible.

I don’t I don’t remember.

Elijah’s mind struggled to process what was happening.

His body still screamed for air, for escape.

But now confusion joined the terror.

Someone else was in the coffin with him.

Someone alive.

Someone who didn’t remember who they were.

How long? Elijah began, then had to stop and swallow, his throat painfully dry.

How long have you been here? I don’t know.

The voice was young, male, trembling with fear.

I woke up and it was dark and I couldn’t move and I can’t remember.

I can’t remember anything before the dark.

Elijah’s fingers still touching the other person’s face.

Felt wetness, tears.

It’s okay, he heard himself say, though nothing was okay.

Nothing would ever be okay again.

We’re We have to get out.

We have to.

I tried, the voice interrupted.

I tried pushing.

I tried scratching.

The wood won’t break.

There’s dirt on top.

I can hear it when I push.

We’re underground.

The simple truth of it was devastating.

They were buried.

Both of them in a coffin built for one body.

Elijah forced himself to think past the panic.

If they were both alive, both awake, then maybe, maybe they could work together.

Two sets of hands instead of one.

Two people pushing instead of one.

What’s your name? Elijah asked.

Can you remember your name? A long silence.

Then Joseph.

I think I think it’s Joseph.

Joseph.

I’m Elijah.

Listen to me, Joseph.

We’re going to get out of here.

You understand? We’re going to push together.

On three.

We both push up as hard as we can.

Can you do that? Yes.

The voice was steadier now, clinging to purpose like a drowning man to a rope.

“One,” Elijah said, positioning his hands flat against the coffin lid.

He felt Joseph do the same beside him.

“Three,” they pushed.

Elijah felt Joseph’s body tense with effort beside him, felt the coffin lid resist, felt dirt shifting above them.

For a moment, nothing happened.

Then, a crack, small but real.

A trickle of soil filtered through the gap, falling onto their faces.

Again, Elijah shouted.

1 2 3.

They pushed harder.

The crack widened.

More dirt poured in, getting into their eyes, their mouths.

The coffin lid was bowing upward, breaking once more everything you have.

This time the lid splintered with a sound like breaking bones.

Earth cascaded down, covering them, filling the coffin.

But there was space now, movement, air, stale and filled with dirt, but air.

Elijah clawed upward, hands digging through soil, pulling himself up.

Beside him, Joseph did the same.

They weren’t free yet, but the grave was shallow, and they were moving, rising, fighting their way toward the surface like men drowning in earth.

Elijah’s hand broke through first, fingers emerging into night air.

He pushed harder, his head clearing the surface, gasping and spitting dirt.

A moment later, Joseph’s hand appeared beside his, then his head.

They dragged themselves out of the grave and collapsed on solid ground, coughing, wretching, alive.

For several minutes, neither of them could do anything but breathe.

Elijah lay on his back on the grass, staring up at the night sky, his chest heaving.

The stars above seemed impossibly bright after the absolute darkness of the coffin.

The air, even humid and thick as it was, tasted like life itself.

Beside him, Joseph was curled on his side, still coughing up dirt.

When Elijah could finally speak, he turned his head toward the boy.

“Joseph, look at me.

” In the faint moonlight, Elijah saw him for the first time.

Joseph was young, perhaps 15 or 16, with dark skin and wide, terrified eyes.

He was wearing the same rough slave clothes as Elijah, and his face was stre with dirt and tears.

How? Elijah began, then stopped.

How did you end up in a coffin with me? But that question led to darker ones, questions that made his skin crawl.

Joseph sat up slowly, hugging his knees to his chest.

I don’t remember being put in there, he whispered.

I don’t remember anything before waking up in the dark.

Just nothing.

Like I didn’t exist until the darkness.

Elijah pushed himself to a sitting position, wincing at the pain in his back from Garrett’s whip.

His mind was starting to work again, past the immediate terror and relief of survival.

He looked back at the broken grave, at the shattered coffin barely visible beneath disturbed earth.

Something was very wrong here.

Joseph, do you remember before you woke up in the coffin? Do you remember working the fields, living in the quarters? Anything about your life? Joseph shook his head.

No, nothing.

Just the dark and the fear.

And you? You were there.

I heard you breathing and I knew I wasn’t alone.

A chill ran down Elijah’s spine that had nothing to do with the night air.

He tried to remember being placed in the coffin.

He remembered the barn, Garrett’s whip, the pain, the darkness of unconsciousness.

But then what had he seen them nail the lid shut? Had he felt being carried to the wagon? No.

There was only darkness and then waking up unable to breathe.

And then Joseph.

I need to think, Elijah said more to himself than to the boy.

This doesn’t make sense.

They thought I was dead.

Dr.

Weathers examined me.

He declared me dead.

They wouldn’t bury someone who was still breathing.

Maybe they made a mistake, Joseph offered quietly.

Maybe.

But Elijah didn’t believe it.

He’d seen death before, seen it many times in the quarters, in the fields.

The dead looked different, felt different, and two people, both buried alive by mistake.

What were the odds? He looked at Joseph more carefully.

Do you remember your last name? Where you worked? Who your master was? No, I told you I don’t remember anything.

Not even your mother.

Your father? Joseph’s face crumpled slightly.

No, I’m sorry.

I just There’s nothing.

It’s like I was born in that box.

Elijah felt something cold settle in his stomach.

He looked back at the grave, then at the boy beside him, then at his own dirt covered hands.

We need to get back to the quarters, he said finally.

We need to I don’t know what we need to do, but we can’t stay here.

He stood, his legs shaky, but functional.

Joseph did the same.

Together, they began walking across the dark field toward the distant lights of the plantation buildings.

Two figures rising from a grave that should have been their end.

Behind them, the broken coffin lay open like a mouth that had failed to swallow its meal.

And in the disturbed earth around it, something else stirred.

The slave quarters at Thornhill Plantation consisted of a row of rough cabins, each housing multiple families in cramped, airless rooms.

At this hour, well past midnight, they should have been silent, everyone asleep to gather strength for the next day’s labor.

But as Elijah and Joseph approached, they saw lamplight in several windows.

Voices carried across the still night air.

Something had disturbed the usual order.

Elijah paused at the edge of the quarters, suddenly uncertain.

What would they say when they saw him? A dead man walking back to life.

And Joseph, who was Joseph? Would anyone know him? Before he could decide, a door opened, and old Ruth emerged carrying a lamp.

She was making her way toward another cabin when she saw them.

The lamp slipped from her fingers, shattering on the ground.

The flame died, but Ruth didn’t move, didn’t speak.

She simply stared.

“Miss Ruth,” Elijah said softly.

“It’s me.

It’s Elijah.

” “No,” Ruth’s voice was barely a whisper.

“No, you’re dead.

I saw them carry you out.

I saw the coffin.

I wasn’t dead.

I don’t know how, but I wasn’t dead.

I woke up buried, and I dug myself out.

” He gestured to Joseph.

We both did.

By now, other doors were opening.

Faces appeared in windows.

Young Samuel stepped out of his cabin.

His eyes wide with disbelief.

Elijah.

Samuel’s voice cracked.

Brother, they said you were gone.

Garrett said your heart gave out.

Garrett was wrong.

Or he lied.

I don’t know which.

People were gathering now, emerging from their cabins.

Despite the late hour, despite the risk, they formed a loose circle around Elijah and Joseph.

keeping their distance as if afraid the two men might vanish like smoke if touched.

An older man named Isaiah spoke up.

“Boy, you know what you’re saying.

You’re saying you came back from death? That’s that ain’t natural.

I’m saying I wasn’t dead.

” Elijah insisted.

I was unconscious.

They buried me thinking I was dead, but I wasn’t.

And him? Isaiah pointed at Joseph.

Who’s he? All eyes turned to Joseph, who shrank back under the attention.

His name is Joseph.

Elijah said he was he was in the coffin with me.

Shocked silence.

Then a woman’s voice.

There wasn’t nobody else died yesterday.

Just you.

I know, Elijah said.

I can’t explain it, but he was there.

We woke up together.

We escaped together.

Ruth had recovered enough to approach.

Her old eyes studying Elijah’s face in the darkness.

Let me see you, child.

She reached out and touched his cheek, then his hand, then pressed her palm against his chest, feeling his heartbeat.

“Sweet Jesus, you’re real.

You’re alive.

” “Yes, ma’am.

” Ruth turned to Joseph.

“And you, boy? What plantation you from?” “I I don’t know, Mom.

I can’t remember.

” Ruth’s eyes narrowed.

“Can’t remember your master, your people, where you worked.

” Joseph shook his head miserably.

The crowd stirred uneasily.

Samuel voiced what several were thinking.

Elijah, this doesn’t feel right.

Something about this.

It’s not natural.

What are you saying? Elijah demanded.

I’m saying maybe you didn’t come back alone.

Maybe something came back with you.

Before Elijah could respond, a scream cut through the night.

It came from one of the cabins, Martha’s cabin.

Everyone turned and several people rushed toward the sound.

Inside, they found Martha pressed into a corner, pointing at the wall.

It was there,” she gasped.

“A shadow, but not from any person.

It was there, and then it moved into the wall through it like it wasn’t even solid.

What did it look like?” Isaiah asked.

Like, like a person, but wrong.

The shape was wrong, and it was looking for something.

Slowly, inevitably, eyes turned back to Elijah and Joseph.

News of Elijah’s return reached the main house before dawn.

Thomas Garrett, sleeping off his whiskey in the overseer’s cottage, was shaken awake by another overseer.

John Blake.

Garrett, wake up.

We got a problem.

What problem? Garrett mumbled, his head pounding.

The slave you buried yesterday.

He’s back.

Garrett sat up so fast he nearly fell out of bed.

What? Elijah.

He walked into the quarters last night covered in dirt.

Says he wasn’t dead.

Says he dug his way out of the grave.

The color drained from Garrett’s face.

That’s impossible.

Dr.

Weathers declared him dead.

I buried him myself.

Well, he’s breathing now, and he’s not alone.

There’s another one with him, a boy nobody knows.

The slaves are spooked, saying unnatural things are happening.

Garrett dressed quickly, his hands shaking.

Blake led him to the main house, where Master Thornhill was already awake, pacing his study with a glass of brandy despite the early hour.

Explain this,” Thornhill demanded when Garrett entered.

“Sir, I don’t understand it myself.

The doctor said he was dead.

No pulse, no breath.

I buried him according to procedure.

Apparently not deeply enough if he could dig himself out.

It was dark, sir, and the ground was hard, and I thought, you thought wrong.

” Thornnehill took a long drink.

This is a disaster.

The slaves are already talking about signs and spirits.

If word of this spreads to other plantations, we’ll have unrest, runaways, rebellion even.

Dr.

Weathers arrived within the hour, summoned urgently from his bed.

He examined Elijah in the barn under Thornhill’s watchful eye, feeling for a pulse, listening to his heartbeat, checking his eyes.

“His heart is strong,” Weathers said, confused.

“Breathing is normal.

He shows every sign of robust health.

” You declared this man dead yesterday,” Thornhill said coldly.

“I there must have been some catalyptic state, some deep unconsciousness that mimic death.

It’s rare, but documented in medical literature.

The heart slows to almost imperceptible levels.

Breathing becomes so shallow as to be undetectable.

” And the other one, this Joseph, Weathers examined Joseph, who sat quietly, eyes downcast.

He appears healthy as well, though his inability to recall his past is concerning.

It could be psychological trauma from whatever he experienced.

But even as Weather spoke, he felt uneasy.

Something about Joseph seemed off.

The boy’s eyes, the way he moved, the strange blankness when asked about his past.

It wasn’t normal amnesia.

It was as if the boy had no past to remember.

After Weathers left, Thornhill called Garrett and Blake into his study.

I want them separated, he ordered.

Elijah goes back to work, but watched constantly.

This Joseph, put him in the locked storage shed until we figure out what to do with him.

And I want both of them kept away from the other slaves.

No talking about what happened.

Anyone caught spreading stories about the dead rising gets 20 lashes.

Understood? “Yes, sir,” they answered in unison.

But as Garrett walked back toward the quarters to carry out the orders, he felt a creeping dread.

He’d buried Elijah in a shallow grave.

Yes, but he’d also nailed that coffin shut himself.

The lid had been secured.

Yet somehow it had been broken open from inside.

And Joseph, where had Joseph come from? That night, alone in his cottage, Garrett woke to the sound of scratching like fingernails on wood.

He sat up, heart racing, and listened.

The sound was coming from beneath his bed, scratching, scraping, like something trying to dig up through the floorboards.

Three days passed.

Elijah was returned to the fields under constant watch, forbidden to speak to the other slaves except when necessary for work.

Joseph remained locked in the storage shed, given only water and minimal food.

Master Thornhill had sent word to neighboring plantations, asking if any had lost a young slave matching Joseph’s description.

No one had.

It was as if Joseph had appeared from nowhere.

In the quarters, despite Thornhill’s orders, whispers spread like fever.

Old Ruth spoke of spirits that walked between worlds.

Isaiah mentioned the old stories from Africa, of those who died wrong and came back changed.

The younger slaves tried to dismiss it as superstition.

But at night, when shadows moved in ways they shouldn’t, doubt crept in.

Samuel found a way to speak to Elijah during the lunch break when the overseer’s attention was elsewhere.

“Brother, what really happened in that grave?” Samuel whispered.

Elijah wiped sweat from his face, his eyes troubled.

I woke up in darkness.

I couldn’t breathe.

And Joseph was there beside me.

That’s the truth.

But how did he get there? I don’t know, Elijah.

Samuel hesitated.

Some of the others, they’re saying Joseph ain’t right.

that he’s not a real person, that he’s something else that came back with you.

That’s foolish talk, is it? He don’t remember nothing.

Nobody knows him.

And Martha wasn’t the only one seeing things.

Two nights ago, little Jim saw something outside his window, a shape that looked like a person, but moved wrong, jerked and twisted like it didn’t understand how bodies work.

Elijah wanted to dismiss it, but he couldn’t because he’d been having strange dreams since returning.

Dreams of being in the coffin.

But in the dreams, when he turned to look at Joseph in the darkness, the face he saw wasn’t human.

It was something trying very hard to look human, but failing.

That night, Thornnehill was woken by screaming from the slave quarters.

He rushed outside with Garrett and Blake, rifles in hand, to find chaos.

Slaves were fleeing from one of the cabins, terror on their faces.

What’s happening? Thornnehill demanded.

Isaiah stepped forward.

The storage shed master.

It’s empty.

Joseph is gone.

But we seen him.

Seen him walking through the quarters and he ain’t walking right.

He’s looking for something.

That’s impossible.

Blake said that shed was locked.

I checked it myself at sunset.

They went to the shed.

The door was indeed locked.

The padlock secure.

But when they opened it, the shed was empty.

No sign of forced escape.

It was as if Joseph had simply passed through the locked door.

“Find him,” Thornhill ordered.

“Search everywhere.

He can’t have gotten far.

” But the search found nothing.

Joseph had vanished.

At dawn, they found something else instead.

In the south field, near the grove of oaks where Elijah had been buried, the earth had been disturbed.

Not at Elijah’s grave that remained broken and open, the shattered coffin visible within.

No, this was a different place.

Several yards away, another grave had been opened from below.

An old grave from weeks or months past.

The earth was pushed aside, and in the shallow hole another broken coffin lay empty.

Garrett stared at it, his face pale.

“Oh God, what is it?” Thornhill demanded.

That’s That’s where we buried Samuel’s brother, Marcus.

He died of fever 3 months back.

I buried him myself, and now his grave is empty.

They found a third disturbed grave before noon, and a fourth, all in the slave cemetery.

All shallow graves, all empty.

By evening, Thornhill had sent for the sheriff, for the preacher, for anyone who might have answers, because this was beyond his understanding, beyond natural explanation.

The slaves knew though.

They gathered in whispered groups and spoke the truth that the white men couldn’t accept.

Something had been buried in those shallow graves, something that wasn’t quite dead.

And Elijah, when he broke free, had shown them all the way back.

The plantation descended into controlled panic.

Thornhill ordered armed men to patrol the grounds.

Slaves were locked in their cabins at night.

Dr.

Weathers, summoned again, could offer no medical explanation and drank himself into unconsciousness to avoid thinking about it.

Elijah, still under guard, was brought before Thornhill in the main house.

He stood in the parlor, dirt still under his fingernails, and faced the master who owned him.

“Tell me the truth,” Thornhill said.

And for the first time since Elijah had known him, the man’s voice carried fear instead of authority.

What did you see in that grave? Elijah met his eyes.

For years, he’d kept his eyes down, his voice subservient, his true self hidden.

But something had changed in the darkness of that coffin.

He’d touched death and come back.

He’d been buried like garbage, and clawed his way to life.

What could Thornhill do to him now that was worse than that? I saw the truth, Elijah said quietly.

I saw what you do to us.

You work us until we break.

Then you bury us in shallow graves like we’re nothing, like we’re not human, like our lives don’t matter enough for even six feet of earth.

That’s not what I asked, isn’t it? Elijah’s voice was steady, calm.

Those graves you found opened.

Marcus and the others, how deep did you bury them, Master Thornnehill? 3 ft.

Two.

Did you even check if they were really dead, or did you just assume? A slave stops breathing.

That’s convenient.

One less mouth to feed.

Bury them quick before anyone looks too close.

Thornhill’s hand moved to the pistol at his belt.

I think some of them weren’t dead, Elijah continued.

I think some of them woke up just like I did in those boxes in the dark.

I think they’ve been there under the ground, trapped and suffocating and dying slowly.

And when I broke free, when the earth opened, they felt it.

They knew there was a way out.

So they dug.

They clawed.

They broke free.

That’s madness, is it? Or is it just the consequence of your cruelty coming back to haunt you? The door opened and Blake entered out of breath.

Sir, we found something in the old storage cellar beneath the barn.

You need to see this.

They went together.

Thornhill, Garrett, Blake, and Elijah, still guarded.

The cellar was accessed through a trap door leading to a dark space where tools and old equipment were stored.

Blake led them down with a lantern.

In the corner, they found them.

Four figures, including Joseph, huddled together in the shadows.

They looked human from a distance, but up close, something was terribly wrong.

Their movements were jerky, uncertain.

Their eyes were unfocused.

They seemed to be trying to remember how to be alive.

When the lantern light hit them, they turned as one to look at Elijah.

Joseph spoke, his voice hollow.

We woke up like you.

We felt you break free, and we knew we could, too.

But we’ve been under so long.

We don’t remember how.

How to be, Thornhill raised his pistol, hands shaking.

Don’t, Elijah said sharply.

They’re not dangerous.

They’re confused.

They’re victims.

Victims of what? Of you.

Of this system that treats us like we’re already dead.

One of the other figures stepped forward.

Marcus, Samuel’s brother, his burial clothes hanging loose on his frame.

I wasn’t dead, he said, his voice rough from disuse.

I heard them nail the coffin shut.

I tried to scream, but no sound came.

I tried to move, but my body wouldn’t obey.

I was awake, aware, for days, maybe weeks, until finally, finally I died.

Until there was nothing left but the memory of being trapped.

Then how are you here? Weathers asked, having followed them down.

Marcus looked at his hands, flexing fingers that moved stiffly.

I don’t know.

Something in that ground, maybe.

Something about being buried alive, buried in anger and fear and injustice.

We couldn’t rest.

We couldn’t leave.

We just stayed.

The truth settled over them like a shroud.

These weren’t supernatural hauntings.

They were something worse.

the natural consequence of cruelty, of carelessness, of treating human beings as disposable property.

Thornhill lowered his pistol, his face ashen, because he knew, and everyone in that cellar knew, that this wasn’t an isolated incident.

How many others had been buried too quickly, too shallowly? How many had been declared dead by a drunk doctor who couldn’t be bothered to check carefully? How many were still there in those graves, trapped in a twilight between life and death? The plantation’s dark secret had literally risen from the ground to confront them, and there was no putting it back.

3 weeks later, Thornhill Plantation was sold.

The official record cited financial difficulties, but the truth spread through whispered conversations across Georgia.

The plantation where the dead wouldn’t stay buried.

the place where shallow graves gave up their victims.

Elijah and several others were sold to different plantations, scattered to prevent them from telling their story together.

But the story spread anyway, as stories do.

And across the South, in quiet conversations in slave quarters, people began to ask questions about the graves of their loved ones, about how deep they were buried, about whether anyone had checked, really checked, to make sure they were gone.

Joseph and the others who’d returned vanished one night, walking into the darkness, perhaps to find whatever peace they could, or perhaps to find those still trapped beneath the earth, still waiting for someone to dig them free.

The grave under the oak trees remained open, a dark mouth in the Georgia soil, a reminder that some truths refuse to stay buried, no matter how deep you dig.

News

Ilhan Omar ‘PLANS TO FLEE’…. as FBI Questions $30 MILLION NET WORTH

So, while Bavino is cracking down in Minnesota, House Republicans turning the heat up on Ilhan Omar. They want to…

FBI & ICE Raid Walz & Mayor’s Properties In Minnesota LINKED To Somali Fentanyl Network

IC and the FBI move on Minnesota, touching the offices of Governor Tim Walls and the state’s biggest mayors as…

FBI RAIDS Massive LA Taxi Empire – You Won’t Believe What They Found Inside!

On a Tuesday morning, the dispatch radios in hundreds of Los Angeles taxi cabs suddenly stopped playing route assignments. Instead,…

Brandon Frugal Finally Revealed What Forced Production to Halt in Season 7 of Skinwalker Ranch….

The Secret of Skinwalker Ranch became History Channel’s biggest hit. Six successful seasons documenting the unknown with real science and…

1 MINUTE AGO: What FBI Found In Hulk Hogan’s Mansion Will Leave You Shocked….

The FBI didn’t plan to walk into a media firestorm, but the moment agents stepped into Hulk Hogan’s Clearwater mansion,…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage… It started like any other evening…

End of content

No more pages to load